Chapter 5. Evolutionary Data

Relational and other types of data stores are ubiquitous in modern software projects, a form of coupling that is often more problematic than architectural coupling. Data is an important dimension to consider when creating an evolvable architecture. It is beyond the scope of this book to cover all the aspects of evolutionary database design. Fortunately, our colleage Pramod Sadalage, along with Scott Ambler, wrote Refactoring Databases, subtitled Evolutionary Database Design. We cover only the parts of database design that impact evolutionary architecture and encourage readers to read this book.

When we refer to the DBA, we mean anyone who designs the data structures, writes code to access the data and use the data in an application, writes code that executes in the database, maintains and performance tunes the databases, and ensures proper backup and recovery procedures in the event of disaster. DBAs and developers are often the core builders of applications, and should coordinate closely.

Evolutionary Database Design

Evolutionary design in databases occurs when developers can build and evolve the structure of the database as requirements change over time. Database schemas are abstractions, similar to class hierarchies. As the underlying real world changes, those changes must be reflected in the abstractions developers and DBAs build. Otherwise, the abstractions gradually fall out of synchronization with the real world.

Evolving Schemas

How can architects build systems that support evolution but still use traditional tools like relational databases? The key to evolving database design lies in evolving schemas alongside code. Continuous Delivery addresses the problem of how to fit the traditional data silo into the continuous feedback loop of modern software projects. Developers must treat changes to database structure the same way they treat source code: tested, versioned, and incremental.

- Tested

-

DBAs and developers should rigorously test changes to database schemas to ensure stability. If developers use a data mapping tool like an object-relational mapper (ORM), they should consider adding fitness functions to ensure the mappings stay in sync with the schemas.

- Versioned

-

Developers and DBAs should version database schemas alongside the code that utilizes it. Source code and database schemas are symbiotic—neither functions without the other. Engineering practices that artificially separate these two necessarily coupled things cause needless inefficiencies.

- Incremental

-

Changes to the database schemas should accrue just as source code changes build up: incrementally as the system evolves. Modern engineering practices eschew manual updates of database schemas, preferring automated migration tools instead.

Database migration tools are utilities that allow developers (or DBAs) to make small, incremental changes to a database that are automatically applied as part of a deployment pipeline. They exist along a wide spectrum of capabilities from simple command-line tools to sophisticated proto-IDEs. When developers need to make a change to a schema, they write small delta scripts, as illustrated in Example 5-1.

Example 5-1. A simple database migration

CREATETABLEcustomer(idBIGINTGENERATEDBYDEFAULTASIDENTITY(STARTWITH1)PRIMARYKEY,firstnameVARCHAR(60),lastnameVARCHAR(60));

The migration tool takes the SQL snippet shown in Example 5-1 and automatically applies it to the developer’s instance of the database. If the developer later realizes they forgot to add date of birth rather than change the original migration, they can create a new one that modifies the original structure, as shown in Example 5-2.

Example 5-2. Adding date of birth to existing table using a migration

ALTERTABLEcustomerADDCOLUMNdateofbirthDATETIME;--//@UNDOALTERTABLEcustomerDROPCOLUMNdateofbirth;

In Example 5-2, the developer modifies the existing schema to add a new column. Some migration tools support undo capabilities as well. Supporting undo allows developers to easily move forward and backward through the schema versions. For example, suppose a project is on version 101 in the source code repository and needs to return to version 95. For the source code, developers merely check out version 95 from version control. But how can they ensure the database schema is correct for version 95 of the code? If they use migrations with undo capabilities, they can “undo” their way backwards to version 95 of the schema, applying each migration in turn to regress back to the desired version.

However, most teams have moved away from building undo capabilities for three reasons. First, if all the migrations exist, developers can build the database just up to the point they need without backing up to a previous version. In our example, developers would build from 1 to 95 to restore version 95. Second, why maintain two versions of correctness, both forward and backward? To confidently support undo, developers must test the code, sometimes doubling the testing burden. Third, building comprehensive undo sometimes presents daunting challenges. For example, imagine that the migration dropped a table—how would the migration script preserve all data in the case of an undo operation?

Once developers have run migrations, they are considered immutable—changes are modeled after double-entry bookkeeping. For example, suppose that Danielle the developer ran the migration in Example 5-2 as the 24th migration on the project. Later, she realizes dateofbirth isn’t needed after all. She could just remove the 24th migration, and the end result on the table is no column. However, any code written between the time Danielle ran the migration and now assumes the presence of the dateofbirth column, and will no longer work if for some reason the project needs to back up to an intermediate point (e.g., to fix a bug). Instead, to remove the no-longer needed column, she runs a new migration that removes the column.

Database migrations allow both database admins and developers to manage changes to schema and code incrementally, by treating each as parts of a whole. By incorporating database changes into the deployment pipeline feedback loop, developers have more opportunities to incorporate automation and earlier verification into the project’s build cadence.

Shared Database Integration

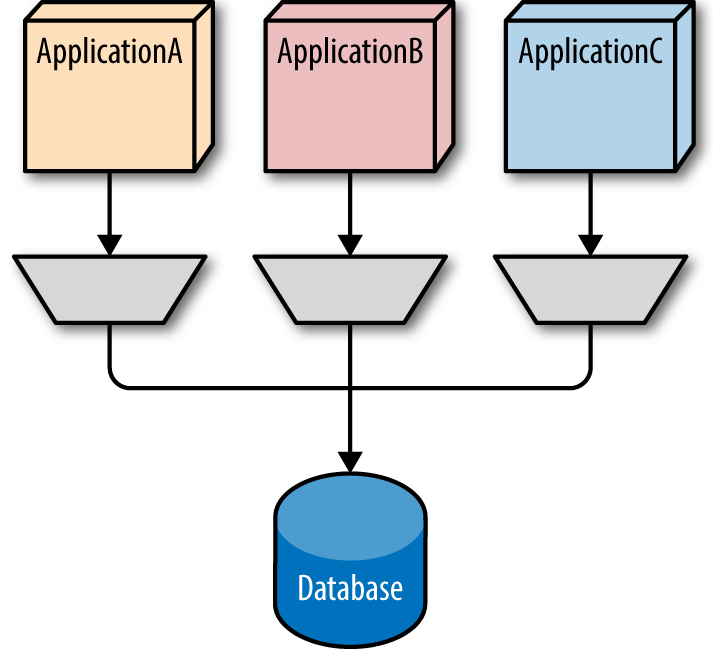

A common integration pattern highlighted here is Shared Database Integration, which uses a relational database as a sharing mechanism for data, as illustrated in Figure 5-1.

Figure 5-1. Using the database as an integration point

In Figure 5-1, each of the three applications share the same relational database. Projects frequently default to this integration style—every project is using the same relational database because of governance, so why not share data across projects? Architects quickly discover, however, that using the database as an integration point fossilizes the database schema across all sharing projects.

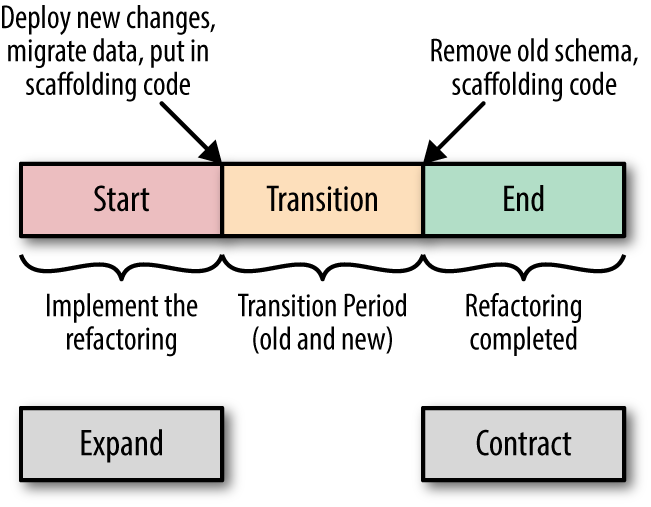

What happens when one of the coupled applications needs to evolve capabilities via a schema change? If ApplicationA makes changes to the schema, this could potentially break the other two applications. Fortunately, as discussed in the aforementioned Refactoring Databases book, a commonly utilized refactoring pattern is used to untangle this kind of coupling called the expand/contract pattern. Many database refactoring techniques avoid timing problems by building a transition phase into the refactoring, as illustrated in Figure 5-2.

Figure 5-2. The expand/contract pattern for database refactoring

Using this pattern, developers have a starting state and an end state, maintaining both the old and new states during the transition. This transition state allows for backwards compatibility and also gives other systems in the enterprise enough time to catch up with the change. For some organizations, the transition state can last from a few days to months.

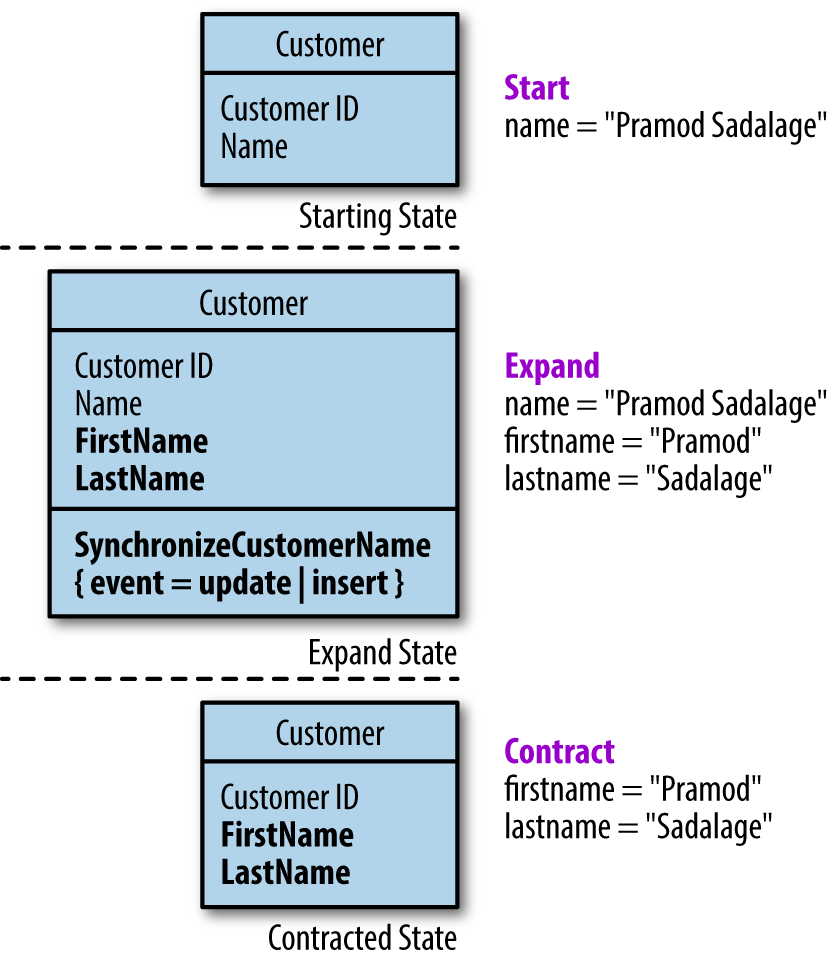

Here is an example of expand/contract in action. Consider the common evolutionary change of splitting a name column into firstname and lastname, which PenultimateWidgets needs to do for marketing purposes. For this change, developers have the start state, the expand state, and the final state, as shown in Figure 5-3.

Figure 5-3. The three states of the expand/contract refactoring

In Figure 5-3, the full name appears as a single column. During the transition, PenultimateWidgets DBAs must maintain both versions to prevent breaking possible integration points in the database. They have several options on how we proceed to split the name column into firstname and lastname.

Option 1: No integration points, no legacy data

In this case, the developers have no other systems to think about and no existing data to manage, so they can add the new columns and drop the old column, as shown in Example 5-3.

Example 5-3. The simple case with no integration points and no legacy data

ALTERTABLEcustomerADDfirstnameVARCHAR2(60);ALTERTABLEcustomerADDlastnameVARCHAR2(60);ALTERTABLEcustomerDROPCOLUMNname;

For Option 1, the refactoring is straightforward—DBAs make the relevant change and get on with life.

Option 2: Legacy data, but no integration points

In this scenario, developers assume existing data to migrate to new columns but they have no external systems to worry about. They must create a function to extract the pertinent information from the existing column to handle migrating the data, as shown in Example 5-4.

Example 5-4. Legacy data but no integrators

ALTERTABLECustomerADDfirstnameVARCHAR2(60);ALTERTABLECustomerADDlastnameVARCHAR2(60);UPDATECustomersetfirstname=extractfirstname(name);UPDATECustomersetlastname=extractlastname(name);ALTERTABLEcustomerDROPCOLUMNname;

This scenario requires DBAs to extract and migrate the existing data but is otherwise straightforward.

Option 3: Existing data and integration points

This is the most complex and, unfortunately, most common scenario. Companies need to migrate existing data to new columns while external systems depend on the name column, which their developers cannot migrate to use the new columns in the desired timeframe. The required SQL appears in Example 5-5.

Example 5-5. Complex case with legacy data and integrators

ALTERTABLECustomerADDfirstnameVARCHAR2(60);ALTERTABLECustomerADDlastnameVARCHAR2(60);UPDATECustomersetfirstname=extractfirstname(name);UPDATECustomersetlastname=extractlastname(name);CREATEORREPLACETRIGGERSynchronizeNameBEFOREINSERTORUPDATEONCustomerREFERENCINGOLDASOLDNEWASNEWFOREACHROWBEGINIF:NEW.NameISNULLTHEN:NEW.Name:=:NEW.firstname||' '||:NEW.lastname;ENDIF;IF:NEW.nameISNOTNULLTHEN:NEW.firstname:=extractfirstname(:NEW.name);:NEW.lastname:=extractlastname(:NEW.name);ENDIF;END;

To build the transition phase in Example 5-5, DBAs add a trigger in the database that moves data from the old name column to the new firstname and lastname columns when the other systems are inserting data into the database, allowing the new system to access the same data. Similarly, developers or DBAs concatenate the firstname and lastname into a name column when the new system inserts data so that the other systems have access to their properly formatted data.

Once the other systems modify their access to use the new structure (with separate first and last names), the contraction phase can be executed and the old column dropped:

ALTERTABLECustomerDROPCOLUMNname;

If a lot of data exists and dropping the column will be time consuming, DBAs can sometimes set the column to “not used” (if the database supports this feature):

ALTERTABLECustomerSETUNUSEDname;

After dropping the legacy column, if a read-only version of the previous schema is needed, DBAs can add a functional column so that read access to the database is preserved.

ALTERTABLECUSTOMERADD(nameAS(generatename(firstname,lastname)));

As illustrated in each scenario, DBAs and developers can utilize the native facilities of databases to build evolvable systems.

Expand/contract is a subset of a pattern called parallel change, a broad pattern used to safely implement backward-incompatible changes to an interface.

Inappropriate Data Coupling

Data and databases form an integral part of most modern software architectures—developers who ignore this key aspect when trying to evolve their architecture suffer.

Databases and DBAs form a particular challenge in many organizations because, for whatever reason, their tools and engineer practices are antiquated compared to the traditional development world. For example, the tools DBAs use on a daily basis are extremely primitive compared to any developer’s IDE. Features that are common for developers don’t exist for DBAs: refactoring support, out-of-container testing, unit testing, mocking and stubbing, and so on.

Two-Phase Commit Transactions

When architects discuss coupling, the conversation usually revolves around classes, libraries, and other aspects of the technical architecture. However, other avenues of coupling exist in most projects, including transactions.

Transactions are a special form of coupling because transactional behavior doesn’t appear in traditional technical architecture-centric tools. Architects can easily determine the afferent and efferent coupling between classes with a variety of tools. They have a much harder time determining the extent of transactional contexts. Just as coupling between schemas harms evolution, transactional coupling binds the constituent parts together in concrete ways, making evolution more difficult.

Transactions appear in business systems for a variety of reasons. First, business analysts love the idea of transactions—an operation that stops the world for some context briefly—regardless of the technical challenges. Global coordination in complex systems is difficult, and transactions represent a form of it. Second, transactional boundaries often tell how business concepts are really coupled together in their implementation. Third, DBAs may own the transactional contexts, making it hard to coordinate breaking the data apart to resemble the coupling found in the technical architecture.

Developers encounter transactions as coupling points when attempting to translate heavily transactional systems to inappropriate architectural patterns like microservices, which impose heavy decoupling burdens. Service-based architectures, with much less strict service boundary and data partitioning requirements, fit transactional systems better. We discuss pertinent differences between these architectural styles in “Service-Oriented Architectures”.

In Chapters 1 and 4, we discussed the architectural quantum boundary concept definition: the smallest architectural deployable unit, which differs from traditional thinking about cohesion by encompassing dependent components like databases. The binding created by databases is more imposing than traditional coupling because of transactional boundaries, which often define how business processes work. Architects sometimes err in trying to build an architecture with a smaller level of granularity than is natural for the business. For example, microservices architectures aren’t particularly well suited for heavily transactional systems because the goal service quantum is so small. Service-based architectures tend to work better because of less strict quantum size requirements.

Architects must consider all the coupling characteristics of their application: classes, package/namespace, library and framework, data schemas, and transactional contexts. Ignoring any of these dimensions (or their interactions) creates problems when trying to evolve an architecture. In physics, the strong nuclear force that binds atoms together is one of the strongest forces yet identified. Transactional contexts act like a strong nuclear force for architecture quanta.

Tip

Database transactions act as a strong nuclear force, binding quanta together.

While systems often cannot avoid transactions, architects should try to limit transactional contexts as much as possible because they form a tight coupling knot, hampering the ability to change components or services without affecting others. More importantly, architects should take aspects like transactional boundaries into account when thinking about architectural changes.

As discussed in Chapter 8, when migrating a monolithic architectural style to a more granular one, start with a small number of larger services first. When building a greenfield microservices architecture, developers should be diligent about restricting the size of service and data contexts. However, don’t take the name microservices too literally—each service doesn’t have to be small, but rather capture a useful bounded context.

When restructuring an existing database schema, it is often difficult to achieve appropriate granularity. Many enterprise DBAs spend decades stitching a database schema together and have no interest in performing the reverse operation. Often, the necessary transactional contexts to support the business define the smallest granularity developers can make into services. While architects may aspire to create a smaller level of granularity, their efforts slip into inappropriate coupling if it creates a mismatch with data concerns. Building an architecture that structurally conflicts with the problem developers are trying to solve represents a damaging version of meta-work, described in “Migrating Architectures”.

Age and Quality of Data

Another dysfunction that manifests in large companies is the fetishization of data and databases. We have heard more than one CTO say, “I don’t really care that much about applications because they have a short lifespan, but my data schemas are precious because they live forever!” While it’s true that schemas change less frequently than code, database schemas still represent an abstraction of the real world. While inconvenient, the real world has a habit of changing over time. DBAs who believe that schemas never change ignore reality.

But if DBAs never refactor the database to make schema changes, how do they make changes to accommodate new abstractions? Unfortunately, adding another join table is a common process DBAs use to expand schema definitions. Rather than make a schema change and risk breaking existing systems, they instead just add a new table, joining it to the original using relational database primitives. While this works in the short term, it obfuscates the real underlying abstraction—in the real world, one entity is represented by multiple things. Over time, DBAs who rarely genuinely restructure schemas build an increasingly fossilized world, with byzantine grouping and bunching strategies. When DBAs don’t restructure the database, they’re not preserving a precious enterprise resource, they’re instead creating the concretized remains of every version of the schema, all overlaid upon one another via join tables.

Legacy data quality presents another huge problem. Often, the data has survived many generations of software, each with their own persistence quirks, resulting in data that is inconsistent at best, and garbage at worst. In many ways, trying to keep every scrap of data couples the architecture to the past, forcing elaborate workarounds to make things operate successfully.

Before trying to build an evolutionary architecture, make sure developers can evolve the data as well, both in terms of schema and quality. Poor structure requires refactoring, and DBAs should perform whatever actions are necessary to baseline the quality of data. We prefer fixing these problems early rather than building elaborate, ongoing mechanisms to handle these problems in perpetuity.

Legacy schemas and data have value, but they also represent a tax on the ability to evolve. Architects, DBAs, and business representatives need to have frank conversations about what represents value to the organization—keeping legacy data forever or the ability to make evolutionary change. Look at the data that has true value and preserve it, and make the older data available for reference but out of the mainstream of evolutionary development.

Case Study: Evolving PenultimateWidgets’ Routing

PenultimateWidgets has decided to implement a new routing scheme between pages, providing a navigational breadcrumb trail to users. Doing so means changing the way routing between pages has been done (using an in-house framework). Pages that implement the new routing mechanism require more context (origin page, workflow state, and so on), and thus require more data.

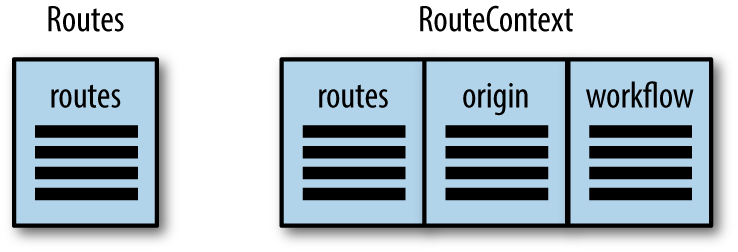

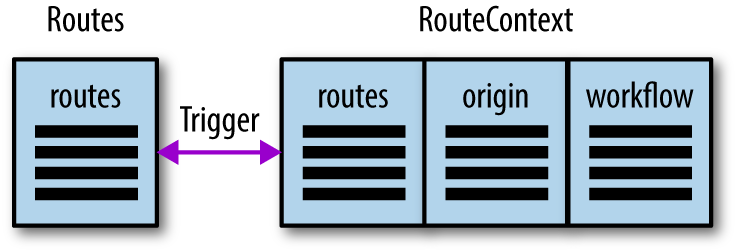

Within the routing service quantum, PenultimateWidgets currently has a single table to handle routes. For the new version, developers need more information, so the table structure will be more complex. Consider the starting point illustrated in Figure 5-4.

Figure 5-4. Starting point for new routing implementation

Not all pages at PenultimateWidgets will implement the new routing at the same time because different business units work at different speeds. Thus, the routing service must support both old and new versions. We will see how that is handled via routing in Chapter 6. In this case, we must handle the same scenario at the data level.

Using the expand/contract pattern, a developer can create the new routing structure and make it available via the service call. Internally, both routing tables have a trigger associated with the route column, so that changes to one are automatically replicated to the other, as shown in Figure 5-5.

Figure 5-5. The transitional state, where the service supports both versions of routing

As seen in Figure 5-5, the service can support both APIs as long as developers need the old routing service. In essence, the application now supports two versions of routing information.

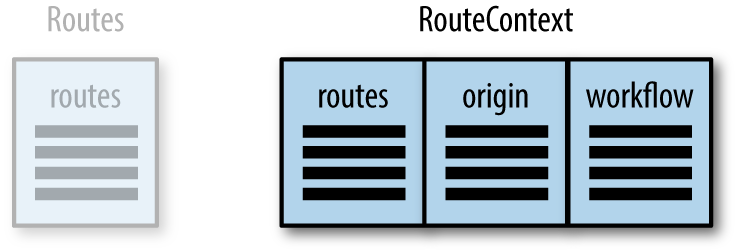

When the old service is no longer needed, the routing service developers can remove the old table and the trigger, as shown in Figure 5-6.

Figure 5-6. The ending state of the routing tables

In Figure 5-6, all services have migrated to the new routing capability, allowing the old service to be removed. This matches the workflow shown in Figure 5-2.

The database can evolve right alongside the architecture as long as developers apply proper engineering practices such as continuous integration, source control, and so on. This ability to easily change the database schema is critical: a database represents an abstraction based on the real world, which can change unexpectedly. While data abstractions resist change better than behavior, they must still evolve. Architects must treat data as a primary concern when building an evolutionary architecture.

Refactoring databases is an important skill and craft for DBAs and developers to hone. Data is fundamental to many applications. To build evolvable systems, developers and DBAs must embrace effective data practices alongside other modern engineering practices.