Chapter 2. Fitness Functions

An evolutionary architecture supports guided, incremental change across multiple dimensions.

our definition

As noted, the word guided indicates that some objective exists that architecture should move toward or exhibit. The authors borrow a concept from evolutionary computing called “fitness functions,” used in genetic algorithm design to define success. Evolutionary computing includes a number of mechanisms that allow a solution to gradually emerge via small changes in each generation of the software. At each generation of the solution, the engineer assesses the current state: Is it closer to or further away from the ultimate goal? For example, when using a genetic algorithm to optimize wing design, the fitness function assess wind resistance, weight, air flow, and other characteristics desirable to good wing design. Architects define a fitness function to explain what better is and to help measure when the goal is met. In software, fitness functions check that developers preserve important architectural characteristics.

We use this concept to define architectural fitness functions:

An architectural fitness function provides an objective integrity assessment of some architectural characteristic(s).

our definition

The fitness function protects the various architectural characteristics required for the system. The specific architectural requirements differ greatly across systems and organizations, based on business drivers, technical capabilities, and a host of other factors. Some systems require intense security; others require significant throughput or low latency. Whereas some might need to be more resilient to failure. These considerations form the “-ilities” that architects care about. Conceptually, an architectural fitness function embodies a protection mechanism for the “-ilities” of a given system.

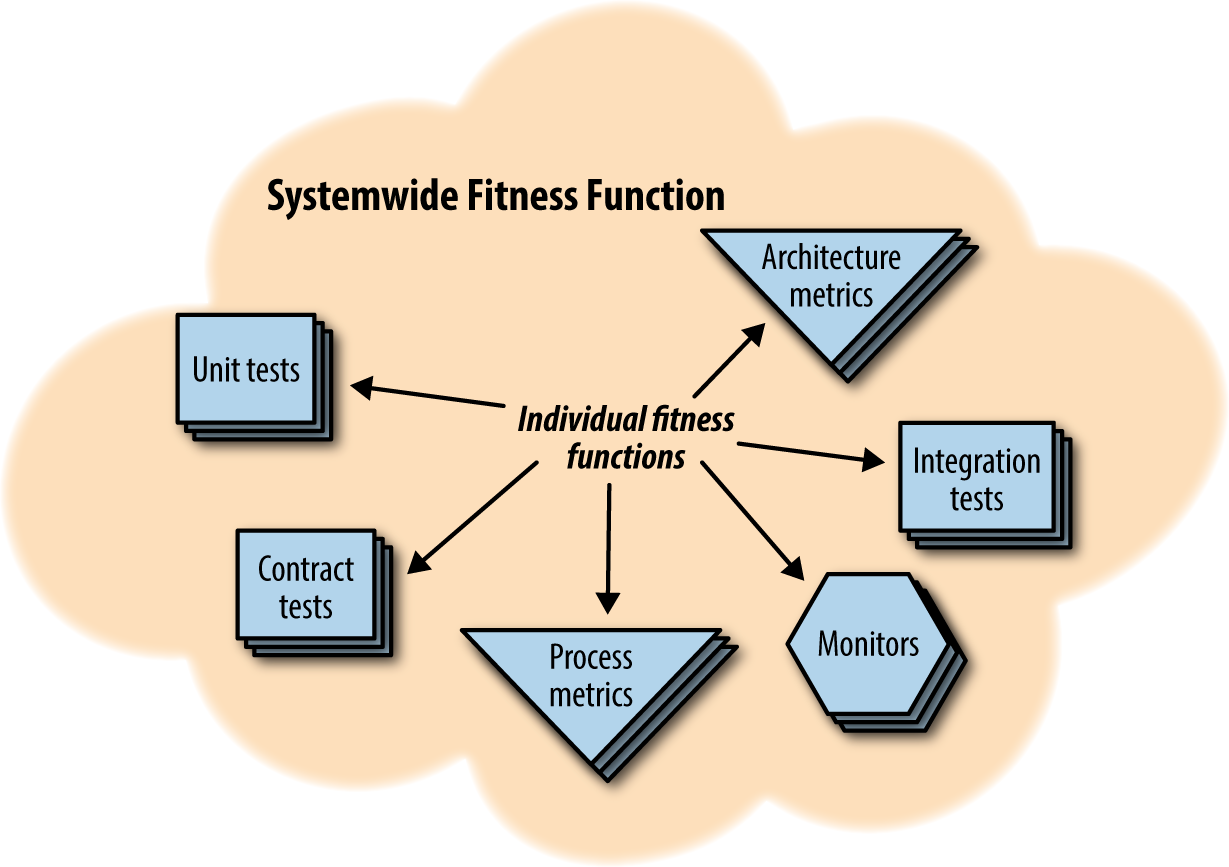

We can also think about the systemwide fitness function as a collection of fitness functions with each function corresponding to one or more dimensions of the architecture. Using a systemwide fitness function aids our understanding of necessary tradeoffs when individual elements of the fitness function conflict with each other. As is common with multifunction optimization problems, we might find it impossible to optimize all values simultaneously, forcing us to make choices. For example, in the case of architectural fitness functions, issues like performance might conflict with security due to the cost of encryption. This is a classic example of the bane of architects everywhere—the tradeoff. Tradeoffs dominate much of an architect’s headaches during the struggle to reconcile opposing forces, such as scalability and performance. However, architects have a perpetual problem of comparing these different characteristics because they fundamentally differ (an apples to oranges comparison) and all stakeholders believe their concern is paramount. Systemwide fitness functions allow architects to think about divergent concerns using the same unifying mechanism of fitness functions, capturing and preserving the important architectural characteristics. The relationship between the systemwide fitness function and its constituent smaller fitness functions is illustrated in Figure 2-1.

Figure 2-1. Systemwide versus individual fitness functions

The systemwide fitness function is crucial for an architecture to be evolutionary, as we need some basis to allow architects to compare and evaluate architectural characteristics against one another. Unlike the more directed fitness functions, architects will likely never try to “evaluate” this systemwide fitness function. Rather, it provides guidelines for prioritizing decisions about the architecture in the future.

A system is never the sum of its parts. It is the product of the interactions of its parts.

Dr. Russel Ackoff

Without guidance, evolutionary architecture becomes simply a reactionary architecture. Thus, a crucial early architectural decision for any system is to define important dimensions such as scalability, performance, security, data schemas, and so on. Conceptually, this allows architects to weigh the importance of a fitness function based on its importance to the system’s overall behavior.

We first define fitness functions more rigorously, and then examine conceptually how they guide the evolution of the architecture.

What is a Fitness Function?

Mathematically speaking, a function takes input from some allowed set of input values and produces an output in some allowed set of output values. In software, we also generally use the term function to refer to something that is actually implementable. However, as with acceptance criteria in agile software development, the fitness functions for evolutionary architecture may not be implementable in software (e.g., a required manual process for regulatory reasons), but architects must still define manual fitness functions to help guide the evolution of the system. While automated checks are preferable, some projects cannot automate all fitness functions. Thus, it is still useful for architects to elucidate architectural verifications explicitly as fitness functions for many reasons that will become evident.

As discussed in Chapter 1, real-world architecture consists of many different dimensions, including requirements around performance, reliability, security, operability, coding standards, and integration, to name a few. We want a fitness function to represent each requirement for the architecture. Developers commonly express fitness functions using different kinds of mechanisms, such as tests or metrics. We’ll look at a few examples and then consider the different kinds of functions more broadly.

Performance requirements make good use of fitness functions. Consider a requirement that all service calls must respond within 100ms. We can implement a test (i.e., fitness function) that measures the response to a service request and fails if the result is greater than 100ms. To this end, every new service should have a corresponding performance test added to the suite. Developers writing the tests must decide what level of comprehensiveness of the range and types of inputs establish confidence in the passing test. They must also decide when to run these tests and how to handle test failures. Performance testing should be conducted early and frequently, in particular to pick up inflection points when performance changes radically (usually in the wrong direction) because of an update to code.

Fitness functions can also be used to maintain coding standards. A common code metric is cyclomatic complexity, a measure of function or method complexity. An architect may set a threshold for an upper value, guarded by a unit test running in continuous integration, using one of the many tools to evaluate that metric. In the previous example, architects decide when to run the fitness functions to assess performance. For coding standards, developers want violations to fail the build immediately and to address the problem aggressively.

Despite need, developers cannot always implement some fitness functions completely because of complexity or other constraints. Consider something like a failover for a database from a hard failure. While the recovery itself might be fully automated (and should be), triggering the test itself is likely best done manually. Additionally, it might be far more efficient to determine the success of the test manually, although scripts and automation are still encouraged.

These examples highlight the different myriad forms fitness functions can take, the immediate response to failure of a fitness function, and even when and how developers might run them. While we can’t necessarily run a single script and say “our architecture currently has a composite fitness score of 42,” we can have precise and unambiguous conversations about the state of the architecture relative to the systemwide fitness function. We can also entertain discussions about the changes that might incur on the architecture’s fitness.

Finally, when we say an evolutionary architecture is guided by the fitness function, we mean we evaluate individual architectural choices against the individual and the systemwide fitness function to determine the impact of the change. The fitness functions collectively denote what matters to us in our architecture, allowing us to make the kinds of trade-off decisions that are both crucial and vexing during the development of software systems.

Fitness functions unify many existing concepts into a single mechanism, allowing architects to think in a uniform way about many existing (often ad hoc) “non-functional requirements” tests. Collecting important architecture thresholds and requirements as fitness functions allows for a more concrete representation for previously fuzzy, subjective evaluation criteria. We leverage a large number of existing mechanisms to build fitness functions, including traditional testing, monitoring, and other tools. Not all tests are fitness functions, but some tests are—if the test helps verify the integrity of architectural concerns, we consider it a fitness function.

Categories

Fitness functions exist across a variety of categories related to their scope, frequency, dynamics, and other factors, including combinations of categories where useful.

Atomic Versus Holistic

Atomic fitness functions run against a singular context and exercise one particular aspect of the architecture. An excellent example of an atomic fitness function is a unit test that verifies some architectural characteristic, such as modular coupling (we show an example of this type of fitness function in Chapter 4). Thus, some application-level testing falls under the heading of fitness functions, but not all unit tests serve as fitness functions—only the ones that verify architecture characteristic(s).

For some architectural characteristics, developers must test more than each architectural dimension in isolation. Holistic fitness functions run against a shared context and exercise a combination of architectural aspects such as security and scalability. Developers design holistic fitness functions to ensure that combined features that work atomically don’t break in real-world combinations. For example, imagine an architecture has fitness functions around both security and scalability. One of the key items the security fitness function checks is staleness of data, and a key item for the scalability tests is number of concurrent users within a certainly latency range. To achieve scalability, developers implement caching, which allows the atomic scalability fitness function to pass. When caching isn’t turned on, the security fitness function passes. However, when run holistically, enabling caching makes data too stale to pass the security fitness function, and the holistic test fails.

We obviously cannot test every possible combination of architecture elements, so architects use holistic fitness functions selectively to test important interactions. This selectivity and prioritization also allows architects and developers to assess the difficultly implementing a particular testing scenario (via fitness functions), thus allowing an assessment of how valuable that characteristic is. Frequently, the interactions between architectural concerns determines the quality of the architecture, which holistic fitness functions address.

Triggered Versus Continual

Execution cadence is another distinguishing factor between fitness functions. Triggered fitness functions run based on a particular event, such as a developer executing a unit test, a deployment pipeline running unit tests, or a QA person performing exploratory testing. This encompasses traditional testing such as unit, functional, behavior-driven development (BDD), and other tests developers.

Continual tests don’t run on a schedule, but instead execute constant verification of architectural aspect(s) such as transaction speed. For example, consider a microservices architecture where the architects want to build a fitness function around transaction time—how long does it take for a transaction to complete on average? Building any kind of triggered test provides sparse information about real-world behavior. Thus, instead of using a triggered test, developers build a fitness function that simulates a transaction in production while all the other real transactions run. This allows developers to verify behavior and gather real data about the system “in the wild.”

Monitoring-driven development (MDD) is another testing technique gaining popularity. Rather than relying solely on tests to verify system results, MDD uses monitors in production to assess both technical and business health. These continual fitness functions are more dynamic than standard triggered tests.

Static Versus Dynamic

Static fitness functions have a fixed result, such as the binary pass/fail of a unit test. This type encompasses any fitness function that has a predefined desirable value: binary, a number range, set inclusion, and so on. Metrics are often used for fitness functions. For example, an architect may define acceptable ranges for average cyclomatic complexity of methods in the code base, graded upon checkin using a metrics tool wired into the deployment pipeline.

Dynamic fitness functions rely on a shifting definition based on extra context. Some values may be contingent on circumstances, and most architects will accept lower performance metrics when operating at high scale. For example, a company might build a sliding value for performance based on scalability—more scale means slower performance is permitted, but only within a range.

Automated Versus Manual

Clearly, architects like automated things—part of incremental change includes automation, which we delve into deeply in Chapter 3. Thus, it’s not surprising that developers will execute most fitness functions within an automated context: continuous integration, deployment pipelines, and so on. Indeed, developers and DevOps have performed a tremendous amount of work under the auspices of Continuous Delivery to automate many parts of the software development ecosystem previous thought impossible. This beneficial trend should continue.

However, as much as we’d like to automate every single aspect of software development, some aspects of software resist automation. Sometimes, a critical dimension within a system, such as legal requirements, defies automation. For example, developers building applications in some problem domains must have manual certification for changes for legal reasons, which cannot be automated away. Similarly, a project may have aspirations to become more evolutionary evolutionary but not yet have appropriate engineering practices in place. For example, perhaps most QA is still manual on a particular project and must remain so for the near future. In both these cases (and others), we need manual fitness functions that are verified by a person-based process.

Clearly, the path to better efficiency eliminates as many manual steps as possible, but many projects still require necessary manual procedures. We still define fitness functions for those characteristics and verify them using manuals stages in deployment pipelines (covered in more detail in Chapter 3).

Temporal

While most fitness functions trigger on change, architects may want to build a time component into assessing fitness. For example, if a project uses an encryption library, the architect may want to create a temporal fitness function as a reminder to check to see if important updates have been performed. Another common use of this type of fitness function is a break upon upgrade test. In platforms like Ruby on Rails, some developers can’t wait for the tantalizing new features coming in the next release, so they add a feature to the current version via a back port, a custom implementation of a future feature. Problems arise when the project finally upgrades to the new version because the back port is often incompatible with the “real” version. Developers use break upon upgrade tests to wrap back ported features to force re-evaluation when the upgrade occurs.

Intentional Over Emergent

While architects will define most fitness functions at project inception as they elucidate the characteristics of the architecture, some fitness functions will emerge during development of the system. Architects never know all important parts of the architecture at the beginning (the classic unknown unknowns problem we address in Chapter 6) and thus must identify fitness functions as the system evolves.

Domain-specific

Some architectures have specific concerns, such as special security or regulatory requirements. For example, a company that handles international fund transfers might design a specific, continuous, holistic fitness function that stress tests security, modeled after the way that the Simian Army (covered in Chapter 3) stresses infrastructure. Many problem domains contain drivers that lead architects toward one or more set of important characteristics. Architects and developers should capture those drivers as fitness functions to ensure that those important characteristics don’t degrade over time.

We show examples of combining these dimensions when it comes time to evaluate fitness functions in Chapter 3.

Identify Fitness Functions Early

Teams should identify fitness functions as part of their initial understanding of the overall architecture concerns that their design must support. They should also identify their system fitness function early to help determine the sort of change that they want to support. Discussions comparing the value and difficulty of implementing different architecture characteristics (along with their fitness functions) help prioritize riskier work earlier to understand how to design for change.

Teams that do not identify their fitness functions face the following risks:

-

Making the wrong design choices that ultimately lead to building software that fails in its environment

-

Making design choices that cost time and/or money but are unnecessary

-

Not being able to evolve the system easily in the future when the environment changes

For each software system, teams should focus on identifying and prioritizing the most important fitness functions as early as possible. Early identification of fitness functions help architects plan for breaking a large system into smaller systems, each dealing with a smaller set of fitness functions.

For example, some companies deal with security-sensitive data such as a credit card or payment details. Depending on the industry and/or job, storing these sorts of information imply stronger regulatory requirements, which may shift because of changes in legislation or standards that impact regulations or because of expansion into new states, territories, or countries with different legislative requirements.

If architects determine that security and payment play a significant role in the systemwide fitness function, it may lead the team to design an architecture that keeps these concerns together. Without identifying fitness functions this early, a team may end up with these responsibilities scattered throughout the entire codebase, requiring a broader impact analysis to understand change and driving up the overall cost of modification.

Fitness functions can be classified into three simple categories:

- Key

-

These dimensions are critical in making technology or design choices. More effort should be invested to explore design choices that make change around these elements significantly easier. For example, for a banking application, performance and resiliency are key dimensions.

- Relevant

-

These dimensions need to be considered at a feature level, but are unlikely to guide architecture choices. For example, code metrics around the quality of code base are important but not key.

- Not Relevant

-

Design and technology choices are not impacted by these types of dimensions. For example, process metrics such as cycle time (the amount of time to move from design to implementation, may be important in some ways but is irrelevant to architecture. As a result, fitness functions for it are not necessary.

Tip

Keep knowledge of key and relevant fitness functions alive by posting the results of executing fitness functions somewhere visible or in a shared space so that developers remember to consider them in day-to-day coding.

Classifying fitness functions into categories helps prioritize design decisions. If a decision design has specific implications for a key fitness function, it will be worth spending more time and effort conducting spikes (timed-boxed, experimental coding projects) to validate the archtectural aspects of the design. Some teams adopt set-based development, a practice in lean and agile processes for designing several solutions in parallel, leaving options open for future decisions in exchange for the cost of building multiple solutions.

Review Fitness Functions

A fitness function review is a meeting with key business and technical stakeholders with the goal of updating fitness functions to meet design goals. Events, such as significant market or customer growth, a new area of functionality or business capability, or an overhaul of an existing part of the system can warrant a fitness function review.

A fitness function review generally includes the following:

-

Reviewing existing fitness functions

-

Checking the relevancy of the current fitness functions

-

Determining change in the scale or magnitude of each fitness function

-

Deciding if there are better approaches for measuring or testing the system’s fitness functions

-

Discovering new fitness functions that the system might need to support

Tip

Review your fitness functions at least once a year.

While software architects are interested in exploring evolutionary architectures, we aren’t attempting to model biological evolution. Theoretically, we could build an architecture that randomly changed one of its bits (mutation) and redeployed itself. After a few million years, we would likely have a very interesting architecture. However, we don’t have millions of years to wait.

We want our architecture to evolve in a guided way, so we place constraints on different aspects of the architecture to reign in undesirable evolutionary directions. A good example is dog breeding: By selecting the characteristics we want, we can create a vast number of different shaped canines in a relatively short amount of time.

We cover more aspects of operationalizing fitness functions in the next chapter. In Chapter 6, we combine fitness functions with all the other architecture dimensions.