Chapter 15. Security Culture

A lot of this book talks about tools and techniques, but it’s critical to recognize that being Agile is about being people first. It’s just as important to talk about the people side of security, and how to build on the Agile values of empathy, openness, transparency, and collaboration if you truly want to be able to develop an effective and forward-looking security program.

Focusing only on the technical aspects will inevitably mean that you fall short, and can in many ways be considered the main failure of the approaches taken to information security programs through the 1990s and early 2000s.

Every organization already has a security culture. The question really is whether you want to take ownership of yours and influence it, or whether you want it to be something that manifests unchecked and unsupported? This chapter can help you take an objective view of your security culture as it currently stands, as well as providing some practical steps to thinking about how to own your organization’s security culture and continue to evolve it over time.

Building a meaningful security culture requires buy in from everyone, not just the security team, and if people outside of the security team have a better idea of some of the challenges discussed in this chapter then that will drive greater empathy and understanding. While it’s true many of the practical aspects discussed are for the security team to implement (or take elements from), it’s important for both Agile teams and the security team to read and understand the following sections.

The Importance of Security Culture

It can be easy to feel that the term culture has become both overloaded and overused in the engineering context, and as such we run the risk of ignoring the benefits that can arise from a clear and concise discussion of culture. Furthermore, the development of a thoughtful security culture within an organization is something that usually gets insufficient attention—in many cases this is isn’t even something that a security team sees as being its responsibility. If however you understand that security is the intersection of technology and people, investing energy in developing a strong security culture is imperative for the overall success of a greater security program.

Defining “Culture”

In an effort to not over complicate the discussion here, when referring to security culture, the definition of culture given by Karl Wiegers in his book Creating a Software Engineering Culture (Dorset House) will be used as the basis from which to build:

Culture includes a set of shared values, goals, and principles that guide the behaviors, activities, priorities, and decisions of a group of people working toward a common objective.

Building from this definition, when we talk about security culture, all we’re really trying to achieve is for everyone in an organization to understand that security is a collective responsibility, and if it is to be successful, is not something that can be solely addressed by the security team. Building the principles and behaviors that allow members of an organization to buy in is the key to achieving this. Unfortunately, this has been something that has often been done quite poorly, the result often being people actively trying to avoid any involvement at all in the process of security. This can be seen as entirely rational with the burden and drag many of the traditional approaches to security place on the people they are trying to protect.

Push, Don’t Pull

Developing a shared understanding between the security team and developers that everyone’s individual actions directly contribute to the overall security posture of the organization is an important step in building a security culture. This encourages everyone to engage proactively with the security team, which can switch the way in which a security team works with the rest of the organization from a purely push based model to one that is at least partly pull based.

The less a security team has to push its way into a process, the less that team is viewed as being an obstacle by the others that are focused on nonsecurity tasks. The greater the degree of pull that is seen toward a security team, the greater it can be said that security as part of the everyday is being realized. Having an organization that actively reaches out to, and engages with, the security team contributes massively to building a sense that the security function is not there to block progress, but instead is there to support the innovation of others.

Building a Security Culture

Culture is not something that can be purchased off the shelf, or something that can be fast tracked. Every organization has its own culture that reflects its unique values and needs, and as such: any associated security culture must equally be tailored and developed to speak to those needs. Successful security cultures that work in one organization may not translate well to another; however, there may well be numerous elements that can be observed and then tailored to fit into the target organization. The things discussed in this chapter should be seen as inspiration or starting points for how you may want to further develop your own security culture, rather than rules that have to be followed.

It is also worth noting that the development of a security culture is not a task that can ever really be considered complete: it must be continually iterated on and refined as the organization in which it exists changes and evolves. Security cultures must also be outward looking to understand the overall technology and threat landscapes within which an organization operates, and ensure they stay apace of the changing ways in which technology is embraced and used by everyone in the organization.

The overall aim of a security culture is to change, or at least influence, both the engineering culture and overall culture of the organization to consider security requirements alongside other factors when making decisions. An important distinction to recognize is that a security culture is the set of practices undertaken to facilitate such changes, not the changes themselves.

This doesn’t mean the goal is to develop an engineering culture in which security overrules all other considerations, but just that security will be taken into account alongside the other requirements and priorities during the development life cycle. While this may sound like a very obvious statement, in the experience of the authors of this book, security can often be treated very much as a second-class citizen that can be ignored or just has lip service paid to it.

Now that we have a handle on engineering and security culture in the abstract, what does it mean to take these ideals and make them into a reality at your organization? As already stated, there is no one-size-fits-all cultural recipe for security; every organization has its own unique norms, needs, and existing culture, and any security culture effort will need to fit in with those. This is not to say that the security culture may not seek to change existing organizational traits that manifest poor security practices, just that realism and pragmatism beat idealism when trying to establish any form of security culture at all.

Now let’s look at a real-world example of a highly successful security culture, and how you can take ideas and lessons from this to build or strengthen your own security culture.

Thinking about your security culture, your approach to security, as a brand, can be helpful in giving you an external reference point from which to view your own work. A brand is promise to its customers: it articulates what they can expect from it and how it is different from its competitors. Similarly, a clearly defined security culture is a promise to the others in an organization about the kind of security experience you are pledging to them, the kind of support you are committed to provide to help solve problems rather than create them, and how you want the organization to perceive the security team. And as with brands, it can take a long time to build and a far shorter time to undermine.

Companies spend vast amounts of energy refining and protecting their brand as they understand its importance to their longer-term success. Invest in your security culture in a similarly committed way, and it will pay back dividends over time and equally help set up a future that is bright.

Principles of Effective Security

In terms of a small case study, we will look at the security team and program in place at Etsy. Far from being held as an ideal situation to mimic, it is a useful example to look at and learn from the efforts that have been tried and iterated upon over a number of years. Essentially, we may be able to make our own efforts show results in a shorter time frame from learning from the successes and mistakes Etsy has already undertaken.

At Etsy, the security culture is based on three core principles. The activities of the security program are then viewed and evaluated from the perspective of how well they uphold or further these principles. None are set in stone, and all are up for re-evaluation and refinement as Etsy continues to evolve as an organization and learn from outside influences.

Who Is Etsy and Why Should We Care?

Etsy is the world’s largest online marketplace for handcrafted goods, founded in 2005. After some early stumbles with its technology, Etsy made radical changes to how it built and delivered software, bringing in new leadership and a new way of working. Former CTO and now CEO, Chad Dickerson, and Etsy’s current CTO, John Allspaw, both came from Flickr where they pioneered a highly collaborative approach in which developers and operations engineers worked closely together to deploy small changes to production every day. Allspaw’s presentation at Velocity in 2009, “10+ Deploys per Day: Dev and Ops Cooperation at Flickr”, is regarded as one of the seminal moments in launching the DevOps movement.

Today, Etsy continues to be a DevOps leader, and like many other internet companies, is an engineering-led organization where technologists are intimately responsible for driving business results, including being responsible for supporting any changes that they make.

At the time of writing, Etsy has over 300 engineers pushing new code into production 50+ times a day, which means that the way that security is approached needs to be fundamentally different in order for it to be successful. In a similar way to the work done in the DevOps space, Etsy has become recognized as a pioneer in progressive approaches to security and security culture.

While Etsy evolved its security philosophy and practices to meet its own specific needs, many of the approaches can be just as helpful for companies that do not follow a continuous deployment development pattern. In this chapter we will look closer at the approaches developed by Etsy and its security teams and see how they contribute to building a positive security (and DevOps) culture.

Enable, Don’t Block

If any of the security principles at Etsy can be considered the most important, it would be the principle of enablement.

Effective security teams should measure themselves by what they enable, not by what they block.

Rich Smith

Many security programs, teams, and professionals measure their success in terms of what they have blocked: those vulnerabilities or activities that could have resulted in a negative impact to the organization that the security team managed to stop from happening. While on the surface this measure seems a reasonable one—that security is here to stop the bad things—an interesting effect of this mindset is the way that over a relatively short period it creates a negative spiral of involvement with a security team.

If other people across the organization become conditioned to think of a security team as being blockers, as being the ones who get in the way of getting real work done, then they will quickly learn to avoid them at all costs. The clear result of this is the creation and perpetuation of a diverging view between the real and perceived security posture of the organization. The security team has only a minimal view of the things occurring that could really benefit from its input as the rest of the organization spends energy actively avoiding the security team, being aware of what they are doing through fear of being derailed.

If the organization sees the security team as a blocker then they will try to route around the team regardless of whatever process and policies may be in place: the more you block, the less effective you become because more and more activities are hidden from you.

If, however, we turn the goal of the security team from a mindset of trying to prevent stupid teams of clueless engineers and product managers from making mistakes with their silly projects, to one of enabling innovation and findings ways to do even the craziest ideas securely, this begins to make a security team into an attractive resource to interact with and seek guidance from.

This switch in mindset from one which is measured on what it prevents into one that measures itself on what it facilitates is so fundamental to all that follows, that without fully embracing it, it may be difficult to truly consider that an organization gets what progressive security is all about.

This isn’t to say that a security team is forbidden from ever saying no to something. What it is saying is that in many cases when “No” would be the de facto response, a “Yes, and” or a “Yes, but” may actually be the more long-term beneficial answer.

“Yes, and” leaves the door open to a security team to provide consultation, support to get the idea or project to a place where it can still achieve its goals, but without some (or all) of the aspects that created the security concerns.

“No” is a security team’s ace and as such should be played sparingly: used too often or as the go-to response for any project that requires out-of-the-box thinking to come up with a meaningful compromise between the business and security goals means that the security teams blocks more than it enables. An unfortunate side effect of saying no is that it can often remove a security team from the decision-making and feedback loops. The development team stops working with the security team to solve problems and instead just puts up with it, or ignores and works around it. Such a breakdown in collaboration and consultation with a security team results in a huge loss to the organization in terms of creative problem-solving, and critically, value creation.

If members of the security team don’t relish the prospect of solving new, difficult, and complex problems that have no black-or-white correct answer, then it’s time to consider whether you have the wrong people dealing with your security. Lazy security teams default to “no” because it is a get out of jail free card for any future negative impact that may come from the project they opposed. Ineffective security teams want the risk profile of a company to stay the same so that they do not have to make hard choices between security and innovation. Nothing will get a security team bypassed quicker than the expectation by others in the organization that the brakes will get applied to their project because the security folks don’t want any change to the risk profile.

It goes without saying that organizations with such teams create silos between the engineers in a company who are striving to drive the business forward, and the security experts who should be striving to help understand and balance the risks associated with either innovation or day-to-day tasks.

Unfortunately, security is rarely black and white in terms of solutions. There are many times that residual risks persist, and they should be balanced against the upsides of the project being supported to succeed. Mindful risk acceptance can be the correct approach as long as the risks and potential impacts are understood, acknowledged, and weighed against the upsides of the project continuing on still having them. Mindful risk acceptance always beats blind risk ignorance.

Understanding and assessing the risks associated with a project presents a perfect opportunity for creative dialog between the security team and the development team. This conversation is not only crucial in order to determine the acceptable level of risk, it also helps engender understanding on both sides, and can go a long way to reducing the level of stress that can often be felt by a development team when considering the security of its creation. Conversations around what level of risk is acceptable, and the benefits that can arise from allowing that risk to remain, demonstrate that everyone is on the same side and they are working together to get the best possible product released, with security being one element that helps define best.

Perfect security is often an illusion dependent on the associated threat model and should rarely be used as a reason to nix a project overall. Pragmatic security is a watchword that should be far more widely observed for most commercial security problems and solutions. Too often a security team can fall into the pattern of making everything a critical issue; this is akin to crying wolf and will be the fastest way to get a group of developers to devalue (or outright ignore) the input from a security team.

There are too many cases where bad judgment calls are made in this regard. Let’s look at one example: an ill-fated attempt to halt the release of a marketing campaign site due to its lack of HTTPS. The site was hosted on both separate servers and a separate domain to the organization’s main site and only contained static public data. While there was a violation of the organization’s stated policy that all web properties must be only SSL, the actual risk presented was minimal aside from the potential reputational damage of having a non-HTTPS protected domain. The marketing team, who were the project owners, was best placed to determine the criticality of the risk. As with many marketing efforts, time was not running on the side of the project, and significant amounts of both social and security capital were cast to the wind by the security team in an effort to arbitrarily stand behind policy in the absence of risk, with the bid to stop the project ultimately failing and the site going live on schedule.

Be on the lookout for third parties such as penetration testers also making mountains out of molehills in terms of a finding’s criticality and impact in an effort to demonstrate value from an engagement. All too often, findings will be presented from the perspective of ultimate security rather than pragmatic security, and it is the responsibility of the security team receiving an external assessment to temper and prioritize findings as appropriate, given the team’s far greater contextual understanding of the organization’s operations and risk tolerance.

You’re only a blocker if you’re the last to know. The security team needs to be included early on in the development life cycle and have its feedback incorporated into the development stories as they build. This isn’t just a responsibility for developers, however—a security team also needs to encourage early and frequent engagement with developers. One important way in which this can be done is by ensuring that the appropriate urgency is assigned to any issues found, and only blocking progress when there are no reasonable alternatives to do so, rather than blocking being the default response to any and every security issue. Sometimes allowing a security issue to ship and getting a commitment from developers that it will be fixed at an agreed upon future date may be the best approach, at least for noncritical issues.

An ineffective security organization creates a haven for those who find excuses to avoid change at all cost in the hope that they can avoid blame for future new insecurities. An effective security organization, however, finds and removes that mindset and replaces it with a mindset that accepts that security issues may arise as a result of change, and relishes the prospect of tackling such problems head-on, recognizing and rewarding the enabling role played by a security team that helps support disruptive innovation take place as securely as possible.

Understanding whether the rest of the organization views you as enablers or as blockers is a good first exercise when you are getting serious about developing a progressive security culture.

Transparently Secure

A security team who embraces openness about what it does and why, spreads understanding.

Rich Smith

People on security teams can often fall into the trap of playing secret agent. What is meant by this is that secrecy, segregation, and all sorts of other activities are undertaken in the name of security that oftentimes actually harm the goal of making an organization more secure because the security team wants to feel special or cool.

The principle of transparency in a security culture may at first seem counterintuitive; however, transparency is a principle that can take many forms, and it is really quite intuitive when you think about it in terms of spreading understanding and awareness about security to a larger group that is not security experts.

Examples of effective transparency can be as simple as explaining why a particular issue is of great concern to the security team, along with a clear and realistic explanation of the impact that could arise. Showing developers how unsanitized input may be misused in their application and the impact that this could have to the business is a far more transparent and valuable discussion of the concerns than pointing them to a coding best practices guide for the language in question and discussing the issue in the abstract. One drives empathy, understanding, and will help incrementally spread security knowledge. The other will more likely come across as an unhelpful edict.

Whenever there is an external security assessment (whether it is a penetration test or a continuous bug bounty) be sure to include the relevant development teams from scoping to completion, ultimately sharing the findings of any issues uncovered, and having the developers fully in the loop as mitigations and fixes are discussed and decided upon.

There is nothing more adversarial than a security team seeming to be working with an external party to pick holes in a system, and then have a series of changes and requirements appear from the process in a black-box fashion. The team whose project is being assessed rarely wants to have urgent requirements or shortcomings tossed over the wall to it, it wants to be engaged with to understand what the problems are that have been found, how they were found, and what the possible real-world impacts could be. Chapter 12 goes into this area in more detail and won’t be repeated here; however, the cultural aspects of how to have supportive conversations when security issues are found during assessment is important to consider before the pen testers have even looked at the first line of code or have thrown the first packet.

A great deal of the value of an assessment comes from being as transparent as possible with the teams whose work is subject to review. It is not only a chance to find serious security bugs and flaws, but is also a highly engaging and impactful opportunity for developers to learn from a team of highly focused security specialists. Simple, but unfortunately rare, approaches such as sharing a repository of security findings from internal or external assessments with the developers directly helps engage and share everything in the full gory detail. This can often also result in the creation of a positive feedback loop where developers end up contributing to a repository of issues themselves when they are able to see the kind of things the security folks care about. It may be surprising the number of security relevant bugs that are often lying around within the collective knowledge of a development team.

Another way in which the transparency principle can be embraced is by becoming more inclusive and inviting developers to be part of the security team and jump into the trenches. This may be part of the onboarding or bootcamp process that new developers go through when joining an organization, or it may be part of some continuing training or periodic cross-team exchange: the important thing is that people from outside of the security team get a chance to see what the day-to-day looks like. Having developers see the grisly details of a security team’s work will do more than anything else to drive empathy and understanding. Oftentimes it will result in the seeding of people across an organization who are not formally on the security team, but who remain closely in touch with them and continue to facilitate visibility to the development process while continuing to learn more about security. At Etsy these are called “security champions” and are a key component to the security team being able to stay available to as many other teams as possible.

A security team that can default to openness and only restrict as the exception will do a far better job at spreading knowledge about what it does, and most importantly, why it is doing it.

Don’t Play the Blame Game

Security failures will happen, only without blame will you be able to understand the true causes, learn from them, and improve.

Rich Smith

As much as it may be uncomfortable to admit, in a sufficiently complex system nothing that any security team does will ever be able to eliminate all possible causes of insecurity. Worse still, the same mistakes may happen again at some point in future.

Being blameless as one of the core tenets of your approach to security may seem like a slightly strange thing to have as one of a list of the three most important principles—surely part of keeping an organization secure means finding the problems that cause insecurity, and in turn making things more secure by finding what (or who) caused those problems, right?

Wrong!

Anyone working in a modern organization knows how complex things get, and how the complexity of the environment seems to continue to increase more than it simplifies. When technology and software are added to this mix, a point can be reached quite quickly where no single person is able to describe the intricacies of the system top to tail. Now, when that grand system is declared as something that needs to be secured, the difficulty of the task at hand can become so immense that shortcuts and corner-cutting exercises inevitably need to be found, as without them no forward progress could be made within the time frames required.

One such shortcut that has been used so pervasively that it regularly goes unquestioned is blame. Finding who is to blame is often the main focus of the activity that follows the discovery of an issue—but that misses the point. It is imperative to understand that building a security culture based around the belief that finding who to blame for a security issue will result in a more secure future is fundamentally flawed.

Many security issues may seemingly arise as a result of a decision or action an individual did, or didn’t, take. When such situations arise—and they will—a common next thought is how the person who seems at fault, the human who made the error, should be held accountable for his lapse in judgment. He caused a security event to occur, which may have caused the security team or possibly the wider organization to have a day from hell, and he should have the blame for doing so placed squarely at his feet.

Public shaming, restriction from touching that system again, demotion, or even being fired could be the order of the day. This, the blameful mindset will tell us, also has the added benefit of making everyone else pay attention and be sure they don’t make the same mistake lest they also suffer the same fate.

If we continue on this path of blaming, then we end up succumbing to a culture in which fear and deterrence is the way in which security improves, as people are just too scared of the consequences to make mistakes.

It would be fair to say that software engineering has much to learn from other engineering disciplines when thinking about blame, and in a wider sense, safety. A notable thinker in the space of safety engineering is Erik Hollnagel, who has applied his approaches across a variety of disciplines, including aviation, healthcare, and nuclear safety—and luckily for us, also in the space of software engineering safety. Hollnagel’s perspective is that the approach of identifying a root cause and then removing that error in an effort to fix things, and therefore make the system safer, works well for machines, but that the approach does not work well for people.

In fact, Hollnagel argues that the focus on finding the cause and then eliminating it has influenced the approach taken to risk assessment so completely that root causes are oftentimes retrospectively created by those investigating rather than being truly found. When human factors are considered in accidents, Hollnagel asserts that the inevitable variability of the performance of the human part of the system needs to be accounted for in the design of the system itself if it is to have a reduction in risk. A quote attributed to Hollnagel that summarizes his views of accidents involving humans well is:

We must strive to understand that accidents don’t happen because people gamble and lose.

Accidents happen because the person believes that:

…what is about to happen is not possible,

…or what is about to happen has no connection to what they are doing,

…or that the possibility of getting the intended outcome is well worth whatever risk there is.

Unless there is compelling evidence that someone in the organization is deliberately trying to cause a security event, the cause of the incident should not just be neatly explained away as human error and then quickly step into applying the appropriate blame. It is key to a progressive security culture to have a shared understanding that the people working in your organization are not trying to create a security event, but instead are trying to get their work done in a way that they believe would have a desirable outcome; however, something either unexpected or out of their control occurred, resulting in the incident. Rather than spending energy searching for the root cause as being who to blame, efforts should be taken to understand the reasons that underly why the person made the decisions she did, and what about the system within which she was working could be improved in order for her to detect things were about to go badly wrong.

If the focus is on assigning blame and delivering a level of retribution to the people perceived as the cause, then it follows that the people with the most knowledge about the event will not be forthcoming with a truthful perspective on everything they know, as they fear the consequences that may follow. If, however, the people closest to the security event are safe in the belief that they can be 100% honest in what they did, and why, and that that information will be used to improve the system itself, then you are far more likely to get insights to critical shortcomings of the system and potentially develop modifications to it to make the future use of it safer.

A mechanism that has been developed to help with this approach of finding the reasoning behind a decision, and then improving the system to ensure more informed decisions are made in future, is the blameless postmortem.

When considering blameless postmortems, it is important to go into the process understanding that the issues you are about to investigate may very well happen again. Preventing the future is not the goal—learning is, and to that end, learning needs to be the focus of the postmortem itself. Participants must consciously counter the basic human urge to find a single explanation and single fix for the incident. This is often helped by having a postmortem facilitator who gives a brief introduction reminding participants what they are all there for: a semi-structured group interview. Nothing more.

While this perspective sounds great on paper, how does it work in reality? From one of the author’s experiences at Etsy, security postmortems were some of the best attended meetings at the company and provided a regular opportunity to investigate root causes that resulted in significant improvements to the security of the systems. Postmortems empower engineers to do what they do best, to solve problems in innovative ways, as well as establish trust between engineers and a security team. The well attended meetings also provided a powerful opportunity to deliver security education and awareness to a large and diverse group of people from across the organization. Who doesn’t want to attend a meeting that’s digging into the details of high-impact security events and listen to experts from across the organization collaborate and problem-solve in realtime in front of them?

Finally, it is worth explicitly noting that postmortems can be a valuable way to create and share a knowledge base of issues across teams. By tackling root causes and reoccurring patterns holistically rather than on a case by case basis, solutions are devised scalably and systemically.

As we touched on in Chapter 13, the important takeaway is that while much of what has been discussed regarding blameless postmortems in the software engineering space has been written from an ops perspective, the lessons learned apply just as much to security, and there are many lessons that can be learned from the last near decade of DevOps development. For further reading on blameless postmortems, see the following:

A Beautifully Succinct Example: The Secure Engineer’s Manifesto

While the three principles of effective security are a wordy way of covering many things that an organization may want to consider in terms of its security culture, a beautifully succinct example of embodying many of them in an easy to understand and culturally resonating way came to one of the author’s attention during a presentation by Chris Hymes discussing the security approach built up at Riot Games. It went:

The Secure Engineer’s Manifesto

I will panic correctly.

I understand laptops can ruin everything.

I will resist the urge to create terrible passwords.

YOLO is not a motto for engineers.

While deliberately lighthearted, it is a great example of supporting and empowering a larger engineering populace to be responsible for their security, while at the same time getting some important and meaningful security advice across in a way that is not dictatorial.

Chris freely admits his manifesto list builds off of and riffs upon other practitioners’ advice and perspective, most notably a fantastic blog post by Ryan McGeehan, titled “An Information Security Policy for the Startup”.

As you consider the security culture you are establishing at your organization, pulling together, and tweaking to fit your needs, a manifesto that your teams can rally around can be a powerful way of getting buy in to your security vision.

Scale Security, Empower the Edges

A practical approach to progressive security that embodies many of the principles described is actively including those outside of the security team in the security decision-making process itself, rather than excluding them and having security as something that happens to them. In many scenarios, the users themselves will have far more context about what may be going on that the security team will; including them in the security decision and resolution process helps ensure that responses to security events are proportional and prioritized.

Including everyone in security decision and resolution loops can be realized in a variety of ways and is something that should be fine-tuned for a particular organization’s needs. Examples of including everyone in the security decision-making process would be the following:

-

Alert users over the internal chat system in the event of noncritical security events such as failed logins, logins from unfamiliar IPs, or traffic to an internal server they don’t normally access, and asking them to provide quick context on what’s going on. In many cases the explanation will be an innocuous one, and no further action will be required. In the event that the user does not know what has happened or does not respond within a time frame, the security team can step in and investigate further. A great discussion of this is “Distributed Security Alerting” by Slack’s Ryan Huber.

-

Notify users at login time if their OS/browser/plug-ins are out of date, giving them the option to update immediately (ideally with one click, if possible), but also, and most importantly, allowing them to defer the update to a future point in time. The number of deferrals allowed before the only option is to update, as well as the versions of the software that can have updates deferred on, is down to the security team, but the important thing is to provide the user some shades of gray rather than just black and white. For example, if a user’s browser is only slightly out of date, it may be an acceptable trade-off to let him log in to get the action he needs to do complete and update later on, rather than blocking his access completely and forcing a browser restart at a incredibly inconvenient moment for him.

-

Ask a user over email or chat if she has just installed some new software or has been manually editing her configuration as a change has been seen on her system such as a new kernel module being loaded, her shell history file got deleted, or a ramdisk was mounted, for example. While suspicious and possibly indicative of malicious activity, in an engineering environment there are many reasons a developer would be making lower-level changes to her setup.

-

In internal phishing exercises, have the main metric being focused on as not the click-through rate on the phishing emails, but the report rate of users who let the security team know they received something strange. A commonly misplaced intention of phishing awareness programs is the aspiration to get the click-through rate down to zero. As the authors of this book can attest to only too well from across a multitude of organizations, while the goal of everyone in an organization doing the right thing and not clicking on the phish every time is laudible, it is wholly unrealistic. If the win condition is that all people have to do the right thing every time, then you’re probably playing the wrong game as you will rarely win. If your focus is on trying to ensure that one person needs to do the right thing, that being notifying the security team he received a phish, then that is a game you are far more likely to win.

These are just a few examples among many possibilities, but they all succeed at pulling the user and her specific context into the decision loop, which contributes to a security team that can better prioritize its work, and a user base that does not feel that security is a stick that is always being used to hit them. Additionally these kinds of interactions provide excellent points at which tiny snippets of security education can be delivered, and starts to build up a workforce that feels connected and responsible for the security decisions being made. Eventually this will result in the creation of positive feedback loops where users are actively engaging with a security team in the truest sense of see something, say something, or proactively giving security a heads-up that they are about to do something that may set off some alerts.

The Who Is Just as Important as the How

If this all makes sense in terms of what the mission of an effective security team should be, then the next step is actually executing on this mission. A great culture needs great people, and too often members of a security team are hired based on their technical skills alone, with little consideration for their soft skills. If it is believed that people are just as important as technology to having an effective security program, then we need to hire security practitioners with that in mind.

One reason why many security teams are actively avoided in their organization is that the personalities and attitudes of the members of the security team are actively working against the wider goal of making security approachable and understandable by the wider organization. Too often security practitioners can be patronizing or condescending in their interactions with the people they are there to support, some seemingly even taking delight in the security issues encountered by their coworkers.

While this is not a book about people management, it’s worth noting that the manager responsible for a security program has a special responsibility to be on the lookout for behavior and attitudes from the security team that are not conducive to the wider security goals, and to put a stop to it if and when it is found. The cardinal rule of thumb that should be front of mind when thinking about security team hiring is one that seems obvious, but historically seems to have been too often not followed:

Don’t hire assholes.

Closely followed by:

If you inadvertently do, or you inherit one, get rid of them ASAP.

A single abrasive member of a security team can do more to undermine the efforts made in the implementation of a progressive security program than almost anything else, as they are the face of that program that others in an organization have to interact with on a daily basis.

A great book that discuses this in much greater detail is The No Asshole Rule: Building a Civilized Workplace and Surviving One That Isn’t (Business Plus) by Robert I. Sutton. In the opinion of the authors, this should be required reading for every security manager, and should be kept close at hand and visible in case its valuable lessons start to be forgotten.

Security Outreach

Cory Doctorow has a fantastic passage in his 2014 book, Information Doesn’t Want to Be Free (McSweeney’s), that sums up the aims of security outreach very succinctly:

Sociable conversation is the inevitable product of socializing. Sociable conversation is the way in which human beings established trusted relationships among themselves.

Security outreach is not buying pizza as a bribe for people to sit through a PowerPoint presentation about how to validate input. It is a genuine investment in social situations that will drive conversations between people on a security team and those outside of a security team. These conversations inevitably form the basis of trusted relationships, which in turn drive greater empathy around security for all involved.

And let’s be clear, this empathy goes both ways, this isn’t purely a drive for others in a company to understand how hard the job of the security team can be; it is equally to drive understanding for those on the security team as to some of the daily struggles and annoyances faced by their nonsecurity coworkers who just want to get their job done. Creating circumstances in which the real people behind the usernames or email addresses can get to know one another is key to avoiding situations where assumptions are made of the others.

Security outreach gives the security team the chance to not fall victim to the temptation that developers are lazy or just don’t care about security, and it gives developers to opportunity to sidestep the assumption that the security team takes a special delight in causing them extra work that slows them down. Security outreach helps everyone assume best intent from their colleagues, which is something that will not only benefit security at an organization, but many other aspects of it as well.

Examples of security outreach events that are distinct from security education are things like the following:

-

A movie night showing a a sci-fi or hacker movie. Bonus points if those attending wear rollerblades and dress up!

-

A trophy or award that the security team gives out with much fanfare on a periodic basis for some worthy achievement. Examples could be the most phishing emails reported or the most security bugs squashed.

-

A bug hunt afternoon where the security team sits in a shared space and hacks on a new product or feature that has reached a milestone, looking for bugs, demonstrating their findings on a big screen, and being available to talk to people about what they are doing and what it’s all about.

-

Just as simple as inviting others from the company to the bar near the office for a few drinks on the security team’s dime.

Again, every situation is different so you should tailor appropriate activities to your organization and the people that make it up.

Ensure there is management buy in to the concept of security outreach, and assign budget to it. It really will be some of the best ROI that your security program will see.

Securgonomics

Much of the discussion so far has been about the theoretical aspects of how a security culture can be established and nurtured; however, as culture is central to how people work with one another and act as a collective, the real-life aspects shouldn’t be ignored. Securgonomics is a completely made-up term created by one of this book’s authors (okay, it was Rich) as part of some presentation slideware: a portmanteau of security and ergonomics.

If the definition of ergonomics is:

er·go·nom·ics \ˌər-gə-ˈnä-miks\

noun

the study of people’s efficiency in their working environment

then the definition of securgonomics (if it were, in fact, a real word!) would be:

se.cure·go·nom·ics \si-ˈkyu̇r-gə-ˈnä-miks\

noun

the study of people’s efficiency of security interactions in their working environment

While a made-up term, it captures the very real observation that security teams can often fall into the trap of separating themselves from the people they are there to support. An Agile approach aims to break down silos because they inhibit easy communication and collaboration, and this needs to extend into the real-world space inhabited by security teams and others in an organization. The goal of all of this is to lower the barriers to interacting with the security team.

The use and design of the physical office space needs to help make the security team visible, easy to approach, and therefore easy to interact with. Too often a security team will lock itself behind doors and walls, which creates a very real us and them segregation. While it is true that security teams may be dealing with sensitive data as part of its daily role, it is also true that for much of the time its activities are not any more sensitive than the work being done by its coworkers.

Security teams can too often fall into the stereotypical trope of being secret squirrels working on things that couldn’t possibly be shared outside of the group. While occasionally this may be true, much of the time this perspective is falsely (and unnecessarily) created by the members of the security team themselves. A team that locks itself away from the rest of the organization will be at a significant disadvantage if it is trying to be a team of transparent enablers that help security become a responsibility that is genuinely shared by people across the organization.

Look at where your security team(s) are physically located, and ask yourself questions like these:

-

Does this help or hinder others to be able to easily come over and interact with team members?

-

Do people see the team as part of their daily routine, or do they have to go out of their way to speak to team members in person?

-

Do new hires see the security team’s location on their first-day office tour?

-

Is the security team near the teams that it works with most closely and frequently?

-

Can others see when the security team is in the office? Can they see when team members are busy?

Where possible, having the security team in a location that has a lot of footfall enables easy interaction with them in a low-lift way. If others wander by the security team on the way to the coffee station or on their way in and out of the office, then micro-interactions will inevitably occur. Not requiring people to make a special journey to the security team will mean that more ad hoc conversations will happen more regularly. This has benefits to everyone, not the least of which is building up trusted relationships between the security team and everyone else.

Where the security folk sit is important; but even if they are in a prime spot where they are easily accessible to all, it doesn’t mean they should rest on their laurels: they need to also work to incentivize other people in the organization to interact with them. This doesn’t need to be overthought and can be as simple as having a sticker exchange, a lending library for security books, or some jars of candy. At Etsy, security candy became a phenomenon all of its own, whereby others across the organization took part in choosing which sweets would be in the next batch of candy to be ordered ,and where the current inventory could be queried through the company-wide chatbot, irccat.

There was even a hack-week project that set up an IP camera over the candy jars to allow remote viewing of what was currently up for grabs. While a fun and silly endeavor, the ROI seen from such a simple act of sharing candy with others in the office incentivized engagement and interaction with the security team in a way that vastly outweighed the monetary cost involved.

Having said all that about the physical location of the security team(s), the final piece of advice would be to not tether the team members to their desks. Having a security team whose method of work enables team members to be mobile around the office and to go and sit with the people they are working with where possible is equally important.

Set the expectation across the organization that a security engineer will go and sit alongside the developer with whom they are diagnosing an issue or explaining how to address a vulnerability. This simple act is a very visible embodiment of the principle of being a supportive and enabling team that wants to understand the other people in an organization, and that they are there to help others succeed on their missions in a secure way.

Dashboards

Lots of teams have dashboards displayed on big screens in their working environment to keep a high-level overview of trends and events that are occurring, and obviously security is no different. However, it is worth pointing out the cultural relevance that dashboards can hold and the dual purposes of the dashboards that may be on display. Having a better understanding of the different objectives that dashboards can help achieve will hopefully empower better decisions about which dashboards make the most sense for your environment.

We can roughly group workplace dashboards into four types:

-

Situational-awareness dashboards

-

Summary dashboards

-

Vanity dashboards

-

Intervention dashboards

Situational awareness dashboards are dashboards that display data that is of most use by a security team itself. The data displayed shows the current state of an environment or system, along with as much historic or contextual data as possible so as to allow team members to make a determination as to whether something may be wrong or not. The primary objective of a situational dashboard is for a security team to at a glance have a sense of whether everything is as expected for a given system. It is worth noting that situational dashboards only indicate that something is amiss and needs investigating, rather than telling you exactly what is taking place attack-wise. They provide easy ways of seeing symptoms. It is for the team then to jump in and determine the cause.

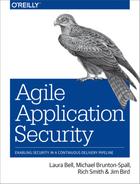

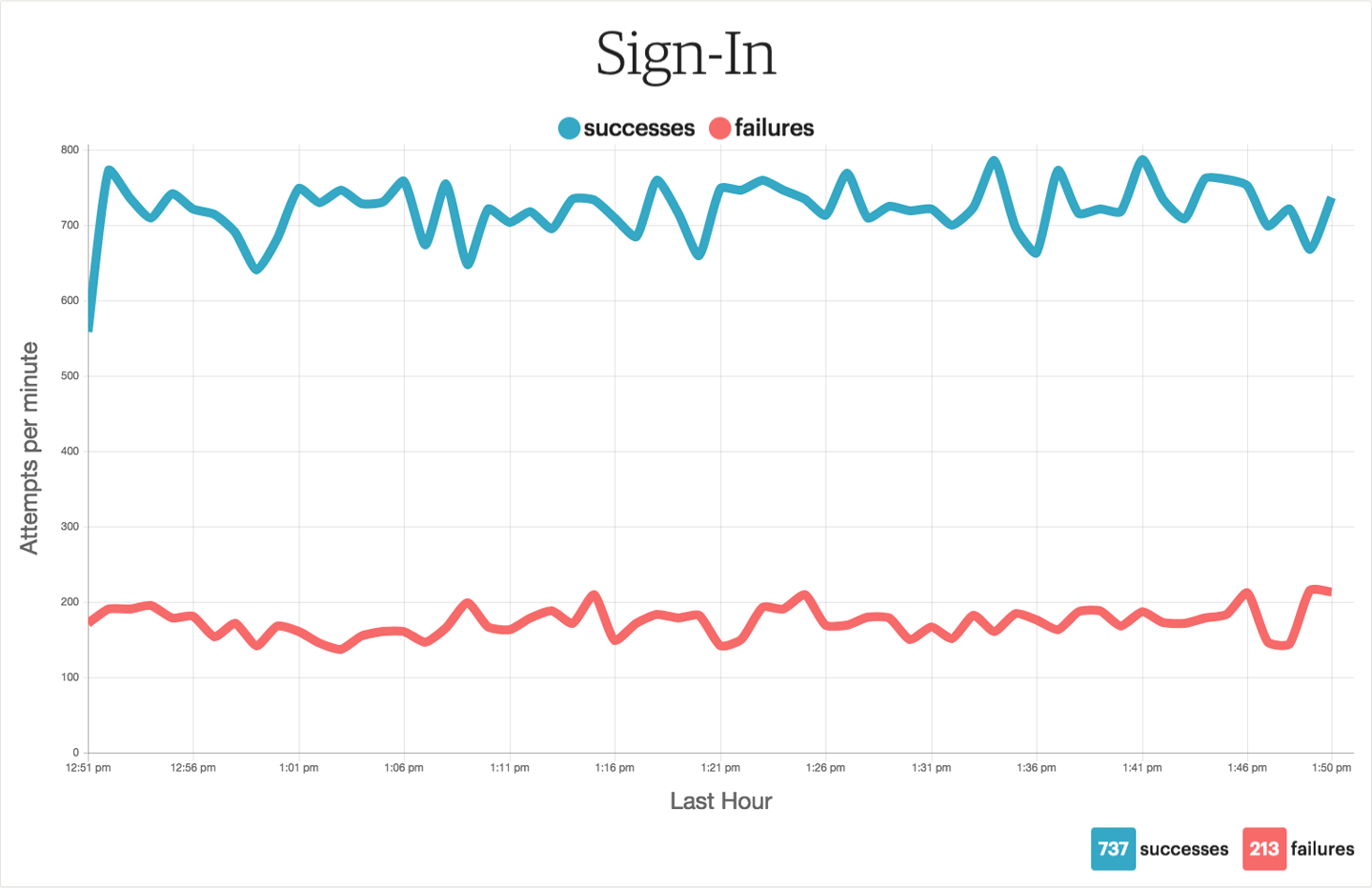

Examples of situational awareness dashboards are displays of data such as “successful versus unsuccessful login attempts over time” (Figure 15-1), “number of 2FA SMS, call and push codes sent over time,” and “number of detected XSS attempts over time” (Figure 15-2). The cultural benefits of situational awareness dashboards really center around them acting as a source of reassurance for people to see that the security of systems is being monitored and acted upon when needed. They can also be a source of engagement with the security team, especially if time-series graphs are being displayed and big changes are relevant. If people see graphs going crazy, they are often curious as to what caused the change and what is being done in response.

Figure 15-1. An example of a situational-awareness dashboard showing the number of successful logins to a web application versus the number of failed login attempts. Patterns between these two metrics can indicate different situations that warrant follow-up by the security team; for example, a rise in failed logins versus successful logins would be indicative of a password-guessing attack taking place. A drop in successful logins could indicate a problem with the authentication system, with legitimate users being denied access.

Figure 15-2. Another example of a situational awareness dashboard, this time showing a number of different types of attack/scanner detections. Spikes and extended shifts in behavior should prompt the security team to follow up to investigate the cause.

If a situational dashboard is dealing with user identifying information, such as a username, then care should be taken to pseudonymize that information to avoid creating a display that feels implicitly blameful or that becomes a source of embarrassment. An example where such obfuscation of data could well be prudent would be dashboards showing the recent VPN logins of users and the location from which the login originated. A pseudonymized identifier for the user is still useful for a security team to see events that team members may want to follow up on without displaying the real names associated with any such events. Then as part of the team’s follow-up, the pseudonymized identifier can be reversed back to a real user ID, which will be used to track down what may be happening.

Summary dashboards are really just a dashboard representation of periodic data rollups or executive summaries. Examples of summary dashboards would be displays of data like “total number of reported phishing emails in the last four weeks,” “dollars paid out in bug bounty this year,” or “external ports shown as open in the last portscan.” They present historic data summaries, often with minimal or no trend data, such as the week-over-week change.

Of the four dashboard categories, it can be argued that summary dashboards are the least useful for security teams, as they do not give information on the current state of security for a system or environment and so do not prompt responses or actions from a security team. They also have minimal value in terms of eliciting engagement from others. Summary dashboards don’t really provide much more information besides, Look! We’ve been doing things. Most of the information they show is better provided in rollup emails or executive summaries sent to those who need to know on a periodic basis. If space is at a premium, then look to your summary dashboards as the first to drop.

The mixture of the types of dashboards that make most sense for your organization is something that only you can determine; but collecting analytics on the interactions they prompt, anecdotal or otherwise, of the different mixtures of dashboards would be encouraged. If the dashboards displayed on big screens are also made available on the intranet for people to view in their browsers’ tracking hits can also be a useful proxy metric for the level of interest different dashboards create.

Vanity dashboards cover those dashboards that display data or visualizations that actually have minimal direct value to the security team’s day-to-day work. Instead, their purpose is to look cool and cause passersby to pause and watch, and hopefully, ask a question about what the cool stuff is.

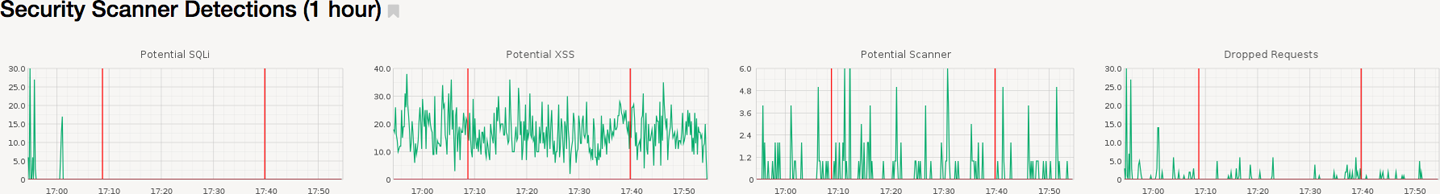

Vanity dashboards often are the least data-dense of any of the dashboard categories, and value looking cool over actually showing data that can be acted upon. Common examples are animated spinning 3D globes showing the geographic sources of incoming attacks, or current top malware being detected/blocked in email. Many security vendors make such animated dashboards freely available on their websites, in the hope that animations that look like they are in Swordfish will convince you to buy their wares. Still, they can be a great source of vanity dashboards for minimal effort. If you would like to build your very own PewPew map (with sound!), there is an open source project called pewpew that will get you started and has lots of options for you to tweak and enhance (see Figure 15-3). Creating fun and ever-changing maps can be a lighthearted way to build a positive security culture for both the security team and the people that will get to view the results.

Figure 15-3. An example of a PewPew map, courtesy of the pewpew opensource project.

Despite the flashy appearance and low informational value of vanity dashboards, they can carry with them some of the highest cultural impact, as they play on the interest many people across an organization have about security (or hacking). They also create great opportunities for people to engage with the security team to talk about what all the laser shots coming from Eastern Europe to the data center actually mean. They are also the ones that people will often pause for a few seconds to watch, which presents an opportunity for security team members to chat with someone about that low-priority alert associated with their IP that came through earlier on.

Of the four types of dashboards, vanity dashboards are those that you should look to switch up periodically to keep them fresh and to continue to illicit engagement from the organization.

Intervention dashboards are possibly the simplest of all the dashboards, as well as being the ones that are (hopefully) seen least often. The sole purpose of intervention dashboards is to alert a security team to a critical situation requiring immediate attention; they are triggered by some pre-configured event and should interrupt the display any of the other types of dashboards. Examples of intervention dashboards would be events such as a critical credential has been detected as being leaked to GitHub, or that an internal honeypot is being interacted with.

Intervention dashboards have a couple of specific benefits beyond other types of alerts and notifications that a security team will likely already be using. Firstly they are a public collective alert. When an intervention dashboard is triggered, the entire security team is made aware at the same time and can prioritize the response to the situation over any other activity taking place. Secondly, and arguably most importantly, intervention dashboards allow others within an organization to see that a serious event is in flight and that the security team is working on understanding and/or responding to the situation. While this second point may self-obvious or self-evident, the value of people outside of a security team being aware that something security related is underway not only facilitates greater empathy for the work of a security team, but also results in future opportunities to engage and educate when people enquire about what is happening.

Some rules of thumb for intervention dashboards are that they should be reserved for the most critical security events that are being monitored, and the frequency of them being displayed should be low and result in an all-hands-on-deck response from the security team. The subject of any intervention dashboard should also be readily actionable, ideally having a dedicated runbook associated with them that drives the initial response and information gathering activity. The data density of intervention dashboards should be low, with a clear description of the triggering event, a timestamp, and possibly a reference to the runbook or initial actions that should come first in a response. The look and feel of the dashboard screen that is triggered is pretty much a free-for-all as long as it is immediately noticeable and stands out from the other dashboards in the rotation; for example, a plain red screen with flashing white Arial text, or a gif of an angry honey badger could both serve this purpose equally well (angry honey badgers are way cooler though).

For any of the dashboards to be available and useful, the correct monitoring and data collection needs to be in place. Approaches to security relevant monitoring are covered in Chapter 8, Threat Assessments and Understanding Attacks.

Key Takeaways

So we made it through our cultural journey! Here are some key things to be thinking about in terms of developing a progressive security culture:

-

You have a security culture whether you know it or not; the question is whether you want to take ownership of it.

-

People are just as important as technology when thinking about security, but have been underserved in many of the traditional approaches to security. An effective security culture puts people at the center when thinking about solutions.

-

Your security culture will be unique to you. There isn’t a cookie-cutter approach.

-

Enabling, transparent, and blameless are the core principles of Etsy’s security culture that provide the foundations upon which everything else is built.

-

Treat your security culture as a brand, take it seriously, and recognize that it is hard-fought and easily lost.