Chapter 8. Threat Assessments and Understanding Attacks

You can’t defend yourself effectively against adversaries that you can’t see and that you don’t understand. You need to understand the threats to your organization, your systems, and your customer’s data, and be prepared to deal with these threats (see “Threat Assessment”).

You need up-to-date, accurate threat information to aid in this understanding:

-

Inform your security monitoring systems so that you know what to look for, and to arm your runtime defenses so that you can protect organization and systems from attacks.

-

Prioritize patching and other remediation work.

-

Drive operational risk assessments so that you can understand how well prepared (or unprepared) your organization is to face attacks.

-

Help write security stories by modeling threat actors as anti-personas.

-

Define test scenarios so that you can attack your own systems using tools like Gauntlt and find security weaknesses before adversaries find them.

-

Guide education and awareness.

-

Assess your design for security risks through threat modeling.

Understanding Threats: Paranoia and Reality

If you read the news or follow security commentators, the world can seem like a fairly terrible place. A steady stream of large-scale systems compromises and breaches are featured in the news each week: high-profile organizations falling to a range of attacks and losing control of sensitive information.

It can be easy when reading these accounts to assume that these organizations and systems were exceptional in some way. That they were unusual in the way that they were attacked or targeted, or perhaps they were especially poorly configured or built. The reality is that all systems and networks connected to the internet are under attack, all the time.

The internet is inhabited by an entire ecosystem of potentially harmful individuals, groups, and automated entities that are continuously working to identify new vulnerable systems and weak points that can be exploited. Attacks emanating from this diverse group can be targeted with a clear objective in mind, or can be indiscriminate and opportunistic, taking advantage of whatever is stumbled across.

With so much hostile activity going on around us, we can easily become overwhelmed. While it’s dangerous to ignore threats, you can’t be afraid of everything: you will only end up paralyzing your organization.

So how do we look at these threats in a way that allows us to take action and make good decisions? Let’s begin by asking some basic questions: Who could attack your system? Why would they want to? How would they go about succeeding? Which threats are most important to you right now? How can you understand and defend against them most effectively?

Understanding Threat Actors

In the security world, the phrase “threat actor” is often used to describe people, organizations, or entities that might pose risk (or threat) to your systems, organization, and people. One way we can begin to understand these threat actors, their capabilities, and intentions is to start to profile and understand how they might behave toward us, and subsequently how to identify and defend against them.

Before we dive into some of the common threat actor archetypes that exist, we should look at what each threat actor has in common. We can break down each of these threat actors into the following five elements. These elements line up with the questions we would want to ask about this person, group, or entity during our analysis:

- Narrative

-

Who is this person, group, or entity, and what is their background?

- Motivation

-

Why would they wish to attack our organization, technology, or people?

- Objective

-

What would they want to achieve by attacking us?

- Resources

-

How skilled, funded, and capable are they? Do they have access to the tools, people, or funds to go through with the attack?

- Characteristics

-

Where in the world are they location? What is their typical attack behavior (if known)? Are they well known?

Using Attack Stories and Threat Modeling as Requirements

Remember that threat modeling and defining attack stories are linked. Revisit Chapter 5, Security and Requirements to refresh how to build this thought pattern into your requirements capture.

Now that we have a structured way to think about these threat actors, let’s use that structure to look at some common profiles and attacker types.

Threat Actor Archetypes

There are many ways to split and sort the common threat actors faced by organizations. For simplicity we will group them based on their relative position to our organization.

Insiders

Insiders have access and are operating from a trusted position. Here are insiders to look out for:

-

Malicious or disenfranchised employees

-

Former employees who might still have privileged access (e.g., to internal systems, cloud applications, or hardware)

-

Activists inside the organization: someone with insider access who has a grudge or a cause against the organization or who wants to damage it for his own purposes

-

Spies: corporate espionage or foreign intelligence moles (yes, this doesn’t just happen in the movies)

-

Puppets: employees who are being coerced or social engineered into using their privileged access on behalf of someone else

-

Staff who make honest but expensive mistakes (especially admins with privileged system access)

Outsiders

Outsiders may choose to attack, but do so from an external, untrusted position. They can be:

-

Users who are sloppy or careless, or simply curious and might cause trouble by accident.

-

Fraudsters.

-

Bots that are automatically scanning everything everywhere all the time for common vulnerabilities.

-

Hackers and script kiddies: random jerks with limited skills out to show off.

-

Security researchers and “security researchers”: skilled professionals who are out to show off.

-

Hacktivists: groups with a moral or political agenda that target your organization or industry for ideological reasons. Such attacks can take a variety of forms ranging from denial of service and website defacement to the leaking of sensitive (and potentially embarrassing) documents and data.

-

Organized criminals looking to steal data or IP, or to conduct ransomware attacks or DDOS attacks and other blackmail.

-

Nation-state attack teams looking to steal data or IP, or conducting reconnaissance or sabotage for cyber warfare (for a vast majority of situations, these will be well outside of your threat model and would not be something you would likely be able to discover or prevent).

Threat Actors and Motivations

Taking our groupings a little further, we can also categorize these examples by motivation and objective. If we disregard those threat actors who cause harm accidentally or through negligence, we can broadly group these actors into the following five motivations:

- Financial

-

Attackers aiming to increase their own wealth through theft of information, money, or assets (or the manipulation of data or markets).

- Political

-

Attackers looking to further a political or belief-based agenda.

- Egotistical

-

Attackers who want to prove themselves or acting for self promotion.

- Personal

-

Attackers motivated by personal grievances and emotional response.

- Chaotic

-

Attackers who just want to cause as much damage and turmoil as possible because they can, for the lulz can be all the motivation that such threat actors need.

While it is possible for threat actors to have multiple motivations from this list, normally one from the list will be their primary focus and determine the resource, enthusiasm, and time given to an attack.

A few years ago, most organizations outside financial services could pretend that their systems were generally safe from professional criminals and focus most of their attention on how to protect against insiders, script kiddies, and other opportunistic hackers. But today, criminals, as well as hacktivist groups and other highly motivated adversaries, have much easier access to the tools and information needed to conduct sophisticated and damaging attacks, making it possible to scale their activities across more and more systems.

Given the current attack landscape of the internet, it would be prudent to assume that every system will be seen as a valid target of attack. While it is important to be aware of the presence of indiscriminate opportunistic attempts at compromise, it is also important to accept that more sophisticated and targeted threat actors will also be looking at your systems. Even if you don’t think you’re important enough to hit their radar, the range of motivations driving them will inevitably make you a more worthwhile target than you may think.

For those of us working in the government, critical infrastructure, or financial sectors, as well as those in startups working on advanced technologies, we must also consider the more sophisticated threat actors. While nation-state attackers are not the primary threat for the majority of businesses, in some industries, the threat posed by these groups is very present.

Identifying the threat actors that are relevant to your organization is often not trivial, but is worth taking the time to do if you want to be able to invest your limited resources in defenses that will actually make a difference to your security when those actors come knocking. Considering the motivations of threat actors and what they could gain by attacking your organization can give you a solid foundation to identify how you might be attacked.

Threats and Attack Targets

Different organizations and systems face different threats, depending on their industry, size, type of data, connectivity, and other factors. To begin to understand the threats you face, you need to answer questions like, what could be the target of an attack?

- Your organization

-

Because of your industry, brand, reputation, or your people.

- Your data

-

Because of the value it holds and/or information it pertains to.

- Your service

-

Because of the functionality that it provides.

- Your resources

-

Because of the compute, storage, or bandwidth you have available.

- Your ecosystem

-

Because of its connectivity with other’s systems (can it be used as a launchpad to attack other systems and organizations, like Target’s HVAC supplier?).

Data is the most common target of attack: people trying to steal it, compromise it, or destroy it. Here are some data-related questions to ask:

-

What data does your system store, process, or have access to that is confidential or sensitive?

-

Who might want to steal it?

-

What would happen if they stole it? What could they do with it? Who would be hurt? How badly would they be hurt?

-

How much data do they need to steal before it matters to customers, to competitors, to regulators, or law enforcement?

-

Could you tell if they stole it?

-

What if they destroy it? What is the cost/loss? Ransomware attacks are rapidly changing how organizations think about this threat.

-

What if they tamper with it? What is the cost/loss? Could you tell if it happened?

Threat Intelligence

There are different sources of information about threats to help you understand threat actors and the risks that they pose to your organization. While this is an area of the security industry that is widely considered to be hyped and to have not returned on the promises of value that have been made (see the “Threaty Threats” warning ahead), it can still have a place in your security program. The following are a few categories of threat intelligence that you can take advantage of:

- Information sharing centers

-

Closed, managed communities that allow government agencies and industry participants to share pertinent threat intelligence and risk information, including indicators of compromise, as well as a forum for sharing best practices and for voluntarily reporting incidents. Examples include FS ISAC for the US financial industry, Auto ISAC for automakers, the US Defense Security Information Exchange (DSIE), the UK Cybersecurity Information Sharing Partnership (CISP), and the Canadian Cyber Incident Response Centre (CCIRC).

- Government advisories

-

Threat and risk advisories from government services and law enforcement agencies such as US-CERT and FBI Infragard.

- Vendor-specific threat feeds

-

Updates on vulnerabilities reported by software and network vendors.

- Internet whitelists and blacklists

-

Updated lists of valid or dangerous IP addresses which can be used to build network whitelists and blacklists for firewalls, IDS/IPS, and monitoring systems.

- Consolidated threat feeds

-

Open source and commercial threat feed services that consolidate information from multiple sources and may offer value-add risk analysis.

- Analyst studies and reports

-

In-depth analysis such as Mandiant’s M-Trends or Verizon’s Data Breach Investigation Report.

Tip

For more information, see “A curated list of Awesome Threat Intelligence resources”.

These sources provide information about threats against your industry or industry sector, against customers or suppliers including new malware or malware variants seen in the wild, new vulnerabilities that are actively being exploited, known sources of malicious traffic, fraud techniques, new attack patterns, zero days and compromise indicators, news about breaches, government alerts, and alerts from law enforcement.

The following are platforms for reporting, detecting, collecting, and aggregating threat intelligence:

Threat information comes in many different forms, including reports, email notifications, and live structured data feeds. Two open community projects help make it easier to share threat information between different organizations and between tools by defining standards for describing and reporting threats.

STIX is a community project to standardize threat information using a common format that can be easily understood and aggregated by automated tooling, in the same way that SCAP or CWE is used. It defines a structured language to describe threats, including information about threat indicators (what other organizations are seeing in the wild).

TAXII is another standards initiative to define common ways of sharing threat data and how to identify and respond to threat information. HailaTaxii.com provides a repository of open source threat feeds available in STIX format.

Threaty Threats

For many in the security industry, threat intelligence has unfortunately evolved into something of a running joke, with outlandish claims of value not being realized, and competition between suppliers seeming to focus on information quantity, not quality or relevance. Visually fascinating but operationally questionable pew pew maps, where threats are animated in ways taken straight from Hollywood, have done little to help the situation in terms of demonstrable value. Such is the derision that this part of the industry attracts parody services like Threatbutt have been created just to mock.

As with many parts of information security, you need to clearly understand and investigate the actual value the various parts of threat intelligence can bring to your organization rather than jumping on the bandwagon just because it looks cool.

Threat Assessment

Your next step is to determine which threats matter most to your organization and to your system: what threats you need to immediately understand and prepare for.

Threat Intel for Developers

Most threat intelligence consists of updates on file signatures (to identify malware), alerts on phishing and DDOS and ransomware attacks and fraud attempts, and network reputation information identifying potential sources of attacks. This is information that is of interest to the security team, operations, and IT, but not necessarily to developers.

Developers need to understand what types of threats they need to protect against in design, development, and implementation. What kind of attacks are being seen in the wild, and where are they coming from? What third-party software vulnerabilities are being exploited? What kind of events should they be looking for and alerting on as exceptions, or trying to block?

The best source of this information is often right in front of developers: their systems running in production. Depending on the solutions being developed, it may also be worth understanding whether there is any value that can be realized from integrating threat intelligence data into the solution itself.

Threats that other organizations in your industry sector are actively dealing with should be a high priority. Of course, the most urgent issues are the threats that have already triggered: attacks that are underway against your organization and your systems.

Coming up, we talk about attack-driven defense, using information that you see about attacks that are underway in production to drive security priorities. Information from production monitoring provides real, actionable information about active threats that you need to understand and do something about: they aren’t theoretical; they are in progress. This isn’t to say that you can or should ignore other, less imminent threats. But if bad guys are pounding on the door, you should make sure that it is locked shut.

Attack-driven defense creates self-reinforcing feedback loops to and from development and production:

-

Use live attack information to update your threat understanding and build up a better understanding of what threats are your highest priority.

-

Use threat intelligence to help define what you need to look for, by adding checks in production monitoring to determine if/when these attacks are active.

-

Use all of this information to prioritize your testing, scanning, and reviews so that you can identify weaknesses in the system and find and remediate, or monitor for, vulnerabilities before attackers find them and exploit them.

In order to make use of this, you will need the following:

-

Effective monitoring capabilities that will catch indicators of attack and feed this information back to operations and developers to act on.

-

Investigative and forensics skills to understand the impact of the attack: is it an isolated occurrence that you caught in time, or something that happened before that you just noticed.

-

A proven ability to push patches or other fixes out quickly and safely in response to attacks, relying on your automated build and deployment pipeline.

Your System’s Attack Surface

To assess the security of your system and its exposure to threats, you first need to understand the attack surface, the parts of the system that attackers care about.

There are actually three different attack surfaces that you need to be concerned about for any system:

- Network

-

All the network endpoints that are exposed, including all the devices and services listening on the network, the OSes, VMs, and containers. You can use a scanning tool like nmap to understand the network attack surface.

- Application

-

Every way that an attacker can enter data or commands, and every way that an attacker could get data out of the system, especially anonymous endpoints; and the code behind all of this, specifically any vulnerabilities in this code that could be exploited by an attacker.

- Human

-

The people involved in designing, building, operating, and supporting the system, as well as the people using the system, who can all be targets of social engineering attacks. They could be manipulated or compromised to gain unauthorized access to the system or important information about the system, or turned into malicious actors.

Mapping Your Application Attack Surface

The application attack surface includes, among other things:

-

Web forms, fields, HTTP headers and parameters, and cookies

-

APIs, especially public network-facing APIs, which are easy to attack; and admin APIs, which are worth the extra effort to attack

-

Clients: client code such as mobile clients present a separate attack surface

-

Configuration parameters

-

Operations tooling for the system

-

File uploads

-

Data stores: because data can be stolen or damaged once it is stored, and because you will read data back from data stores, so data can be used against the system in Persistent XSS and other attacks

-

Audit logs: because they contain valuable information or because they can be used to track attacker activity

-

Calls out to services like email and other systems, services, and third parties

-

User and system credentials that could be stolen, or compromised to gain unauthorized access to the system (this also includes API tokens)

-

Sensitive data in the system that could be damaged or stolen: PII, PHI, financial data, confidential or classified information

-

Security controls: your shields to protect the system and data: identity management and authentication and session management logic, access control lists, audit logging, encryption, input data validation and output data encoding; more specifically, any weaknesses or vulnerabilities in these controls that attackers can find and exploit

-

And, as we look at in Chapter 11, your automated build and delivery pipeline for the system.

Remember that this includes not only the code that you write, but all of the third-party and open source code libraries and frameworks that you use in the application. Even a reasonably small application built on a rich application framework like Angular or Ruby on Rails can have a large attack surface.

Managing Your Application Attack Surface

The bigger or more complex the system, the larger the attack surface will be. Your goal should be to keep the attack surface as small as possible. This has always been hard to do and keeps getting harder in modern architectures.

Using Microservices Explodes the Attack Surface

Microservices are one of the hot new ideas in application architecture, because they provide development teams with so much more flexibility and independence. It’s hard to argue with the success of microservices at organizations like Amazon and Netflix, but it’s also worth recognizing that microservices introduce serious operational challenges and security risks.

The attack surface of an individual microservice should be small and easy to review. But the total attack surface of a system essentially explodes once you start using microservices at any scale. The number of endpoints and the potential connections between different microservices can become unmanageable.

It is not always easy to understand call-chain dependencies: you can’t necessarily control who calls you and what callers expect from your service, and you can’t control what downstream services do, or when or how they will be changed.

In engineering-led shops that follow the lead of Amazon and Netflix, developers are free to choose to the best tools for the job at hand, which means that different microservices could be written in different languages and using different frameworks. This introduces new technology-specific risks and makes the job of reviewing, scanning, and securing the environment much more difficult.

Containers like Docker, which are often part of a microservices story, also impact the attack surface of the system in fundamental ways. Although containers can be configured to reduce the system attack surface and improve isolation between services, they expose an attack surface of their own that needs to be carefully managed.

This seems like too much to track and take care of. But you can break down the problem—and the risk.

Each time that you make a change to the system, consider how the change impacts the attack surface. The more changes that you make, the more risk you may be taking on. The bigger the change, the more risk that you may be taking on.

Most changes made by Agile and DevOps teams are small and incremental. Adding a new field to a web form technically increases the size of the attack surface, but the incremental risk that you are taking on should be easy to understand and deal with.

However, other changes can be much more serious.

Are you adding a new admin role or rolling out a new network-facing API? Are you changing a security control or introducing some new type of sensitive data that needs to be protected? Are you making a fundamental change to the architecture, or moving a trust boundary? These types of changes should trigger a risk review (in design or code or both) and possibly some kind of compliance checks. Fortunately, changes like this are much less common.

Agile Threat Modeling

Threat modeling is about exploring security risks in design by looking at the design from an attacker’s perspective and making sure that you have the necessary protection in place. In the same way that attacker stories or misuse cases ask the team to re-examine requirements from an attacker’s point of view, threat modeling changes the team’s perspective in design to think about what can go wrong and what you can do about it at the design level.

This doesn’t have to be done in a heavyweight, expensive Waterfall-style review. All that you need to do is to build a simple model of the system, and look at trust, and at threats and how to defend against them.

Understanding Trust and Trust Boundaries

Trust boundaries are points in the system where you (as a developer) change expectations about what data is safe to use and which users can be trusted. Boundaries are where controls need to be applied and assumptions about data and identity and authorization need to be checked. Anything inside a boundary should be safe. Anything outside of the boundary is out of your control and should be considered unsafe. Anything that crosses a boundary is suspect: guilty until proven innocent.

Trust Is Simple. Or Is It?

Trust is a simple concept. But this is also where serious mistakes are often made in design. It’s easy to make incorrect or naive assumptions about the trustworthiness of user identity or data between systems, between clients (any kind of client, including browsers, workstation clients, mobile clients, and IoT devices) and servers, between other layers inside a system, and between services.

Trust can be hard to model and enforce in enterprise systems connected to many other systems and services. And, as we’ll see in Chapter 9, Building Secure and Usable Systems, trust is pervasive and entangled in modern architectures based on microservices, containers, and cloud platforms.

Trust boundaries become especially fuzzy in a microservices world, where a single call can chain across many different services. Each service owner needs to understand and enforce trust assumptions around data and identity. Unless everyone follows common patterns, it is easy to break trust relationships and other contracts between microservices.

In the cloud, you need to clearly understand the cloud provider’s shared responsibility model: what services they provide for you, and how you need to use these services safely. If you are trusting your cloud provider to do identity management and access management, or auditing services, or encryption, check these services out carefully and make sure that you configure and use them correctly. Then write tests to make sure that you always configure and use them correctly. Make sure that you understand what risks or threats you could face from co-tenants, and how to safely isolate your systems and data. And if you are implementing a hybrid public/private cloud architecture, carefully review all data and identity passed between public and private cloud domains.

Making mistakes around trust is #1 on the IEEE’s Top 10 Software Security Design Flaws.1 Their advice is: “Earn or Give, But Never Assume Trust.”

How do you know that you can trust a user’s identity? Where is authentication done? How and where are authorization and access control rules applied? And how do you know you can trust the data? Where is data validated or encoded? Could the data have been tampered with along the way?

These are questions that apply to every environment. You need to have high confidence in the answers to these questions, especially when you are doing something that is security sensitive.

You need to ask questions about trust at the application level, as well as questions about the operational and runtime environment. What protection are you relying on in the network: firewalls and proxies, filtering, and segmentation? What levels of isolation and other protection is the OS or VM or container providing you? How can you be sure?

Trusted Versus Trustworthy

The terms trusted and trustworthy are often used interchangeably, but when it comes to security their difference is actually very important, and the widespread incorrect usage of them illustrates some deeper misunderstandings that manifest across the space. It could well be that the seeds of confusion were planted by the famous Orange Book (Trusted Computer System Evaluation Criteria) developed by the US Department of Defense in the early 1980s.

If something is trusted, then what is being said is that someone has taken the action of placing trust in it and nothing more. However, if something is trustworthy, then a claim is being made that the subject is worthy of the trust being placed in it. These are distinctly different and carry with them different properties in terms of security.

You will often see advice stating not to open untrusted attachments or click on untrusted links, when what is really meant is not to open or click untrustworthy links or attachments.

When discussing users and systems in terms of threat models, it’s important to understand the difference between entities that are trusted (they have had trust placed in them regardless of worthiness) and entities that are trustworthy (they have had their worthiness of trust evaluated, or better yet proven).

While this may all seem grammatical pedantry, the actual impact of understanding the differences that manifest from trusted versus trustworthy actors can make a very real-world difference in your security approaches.

A great short video by Brian Sletten discussing this as it relates to browser security can be found at https://www.oreilly.com/learning/trusted-vs-trustworthy and is well worth the 10-minute investment to watch.

Threats are difficult for developers to understand and hard to for anyone to quantify. Trust is a more straightforward concept, which makes thinking about trust a good place to start in reviewing your design for security weaknesses. Unlike threats, trust can also be verified: you can walk through the design or read the code and write tests to check your assumptions.

Building Your Threat Model

To build a threat model, you start by drawing a picture of the system or the part of the system that you are working on, and the connections in and out to show data flows, highlighting any places where sensitive data including credentials or PII are created or updated, transmitted, or stored. The most common and natural way to show this is a data flow diagram with some extra annotations.

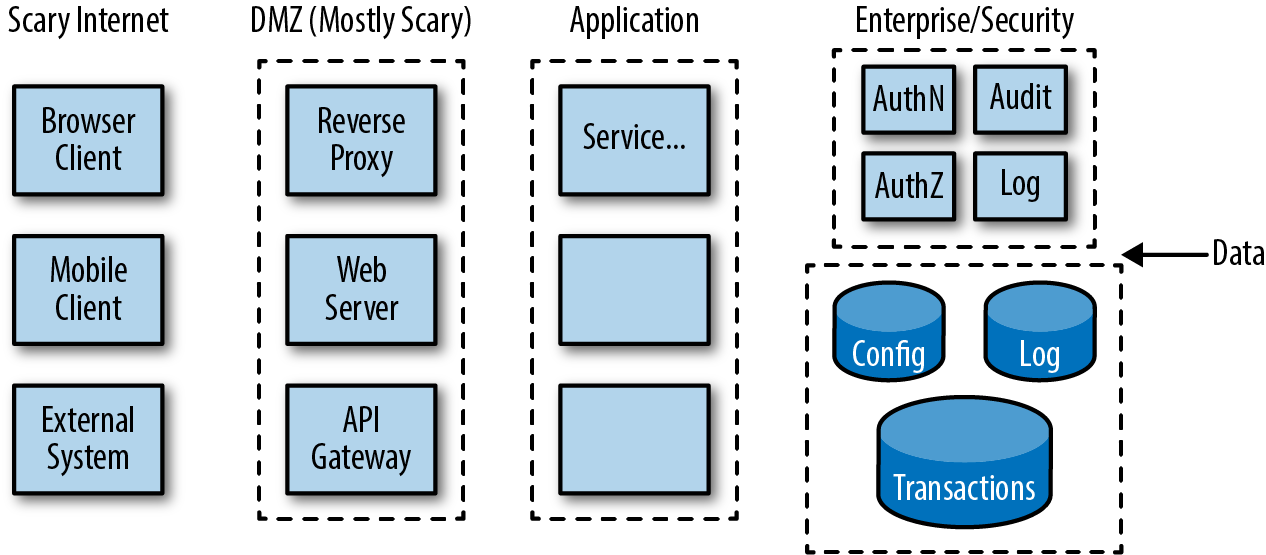

Once you have the main pieces and the flows described, you’ll want to identify trust boundaries. A common convention is to draw these as dotted lines demarcating the different trust zones, as we show in Figure 8-1.

Figure 8-1. Simple trust/threat boundary model

Trust zones can be established between organizations, between data centers or networks, between systems, between layers of an application, or between services or components inside a service, depending on the level that you are working at.

Then mark out the controls and checks at these boundaries:

-

Where is authentication done?

-

Where are access control checks applied?

-

Data validation

-

Crypto—what information is being encrypted and when/where

-

Rate limiting

-

Sensors and detectors

“Good Enough” Is Good Enough

Don’t spend a lot of time making pretty pictures. Your model can be rough, especially to start. Like any Agile modeling, the point is to have just enough that everyone can understand the pieces and how they fit together; anything more is waste. Version 0.1 could be nothing more than a whiteboard diagram that is captured via a photo on a mobile phone.

Free Threat Modeling Tool from Microsoft

Microsoft provides a free tool called Microsoft Threat Modeling Tool 2016 which will help you create threat models and save them so that you can review and update the model as you make changes to the system.

As with all free tools, there are advantages and disadvantages to using this to help with your threat models. Using a modeling tool like this will allow you to easily drag and drop components onto your diagram without having to remember what the specific symbol should be at any stage. They also have a wide range of symbols and example components available to choose from.

There are challenges to using this tool though. The very Microsoft-specific language and suggested components can make it difficult to decide which items to use on your diagram. Often there are dozens of components which share a symbol but have a different name in the menu.

Furthermore, this tool has a built-in report generation feature that will export a threat assessment based on your model (and the attributes you completed for each component). While this can seem very impressive, it can turn into hundreds of generic threats in HTML format that need to be triaged and assessed before they can be used. These reports often take a lot longer to triage than a manual threat assessment would have taken; and without this triage process, the assessment can be an impressive-looking distraction.

We recommend using tools for the modeling of systems, and conducting the threat assessment itself manually or outside of the tool, preferably in a way that tightly integrates with your issue tracking and pipeline.

Once you have a good enough diagram drawn up, get the team together to walk through the diagram and do some brainstorming about threats and attacks. Look carefully at information that crosses trust boundaries, especially sensitive information. Be realistic when it comes to threats and attack scenarios. Use the threat intelligence that you’ve captured and attack patterns that you’ve observed in production to focus your attention. At this stage it would also be recommended to call out the things that are not in your threat model and you are consciously placing out of scope, a clear articulation of what you won’t be focusing on helps you center on what you will be.

Threat modeling is more effective if you can get people with different viewpoints involved. Developers who know the system or part of the system that you are reviewing, architects and developers who know other parts of the system, testers who know how the system actually works, operations engineers and network engineers who understand the runtime environment, and security specialists will all look for different problems and risks.

Try not to get bogged down in arguing about low-level details, unless you are already reviewing at a low level and need to verify all of these assumptions.

Spend time identifying risks and design weaknesses before switching into solution mode. Then look at what you could change to protect your system from these threats. Can you move responsibilities from outside of a trust boundary to inside? Can you reduce the number of connections between modules, or simplify the design or workflow to reduce the size of the attack surface? Do you need to pass information across a trust boundary, or can you pass a secure key or token instead?

What changes can you, or must you, make now, and what changes can be added to the backlog and scheduled?

Learning More About Threat Modeling

SAFECode has a 45-minute free online course on Threat modeling that provides a good overview.

Microsoft popularized the practice of application threat modeling. For a quick introduction to how they do (or at least used to do) threat modeling at Microsoft, read Peter Torr’s Blog, “Guerrilla Threat Modelling (or ‘Threat Modeling’ if you’re American)”.

If you really want to dig deep into everything about threat modeling, you should read Adam Shostack’s book Threat Modeling: Designing for Security (Wiley).

Shostack was one of the leaders of Microsoft’s software security practice and helped to pioneer the threat modeling approach followed in Microsoft’s SDL. His book covers threat modeling in detail, including different techniques and games and tools for building threat models, as well as an analysis of the different types of threats that you need to consider.

Thinking Like an Attacker

In Chapter 5, we asked developers to put on a black hat and think like an attacker when writing attacker stories or negative scenarios. But how do you do that? How do you think like an attacker? What is it like to see a system through an attacker’s eyes?

Adam Shostack, a leading expert on threat modeling, says that you can’t ask someone to “think like an attacker” and expect them to be really effective at it if they haven’t actually worked as a pen tester or done some serious hacking. It’s like being told to “think like a professional chef.” You might know how to cook at home for family and friends, and you might even be good at it. But this doesn’t mean that you know what it’s like to work in a Michelin star restaurant or work as a short-order cook in a diner during the morning rush.2

You need real experience and context to understand how attackers think and work. You can learn something over time from working with good pen testers (and from Red Teaming exercises and bug bounties) and through training. Using pen testing tools like OWASP ZAP in your testing programs will open a small window into the world of an attacker. Capture the Flag exercises and hands-on exploitation training systems can help people become more familiar with the ways in which attackers think about the world. But at least in the short term you’ll need to rely on a security expert (if you have one available) to play the role of the attacker.

STRIDE: A Structured Model to Understand Attackers

Even if you know how attackers work, it’s a good idea to follow a structured model to help make sure that you remember to review the design for different security threats and risks. One of the best known approaches for this is Microsoft’s STRIDE.

STRIDE is an acronym that stands for the following:

| Threat | Solution | |

|---|---|---|

Spoofing |

Can you trust the user’s identity? |

Authentication and session management, digital certificates. |

Tampering |

Can you trust the integrity of the data? Can someone change it on purpose, or accidentally? |

Digital signatures, checksums, sequence accounting, access control, auditing. |

Repudiation |

Can you prove who did something and when they did it? |

End-to-end auditing and logging, sequence accounting, digital certificates and digital signatures, fraud prevention. |

Information disclosure |

What is the risk of data theft or leaks? |

Access control, encryption, data tokenization, error handling. |

Denial of service |

Can someone stop authorized users from getting valid access to the system—on purpose, or accidentally? |

Rate limiting, boundary protection, elastic resourcing, availability services. |

Elevation of privilege |

Can an unprivileged user gain privileged system access? |

Authorization, least privilege, type safety and parameterization to prevent injection attacks. |

STRIDE is a simple way of thinking about the most common paths that attackers can take to get at systems and data. There are other approaches that are just as effective, such as attack trees, which we looked at in Chapter 5. What’s important is to agree on a simple but effective way to think about threats and how to defend against them in design.

Don’t Overlook Accidents

When you are thinking about what can go wrong, don’t overlook accidents. Honest mistakes can cause very bad things to happen to a system, especially mistakes by operations or a privileged application admin user. (See the discussion of blameless postmortems in Chapter 13.)

Incremental Threat Modeling and Risk Assessments

Where does threat modeling fit into Agile sprints or Lean one-piece continuous flow? When should you stop and do threat modeling where you are filling in the design as you go in response to feedback, where there are no clear handoffs or sign offs because the design is “never finished,” and where there may be no design document to hand off because “the code is the design”?

Assess Risks Up Front

You can begin up front by understanding that even if the architecture is only roughed out and subject to change, the team still needs to commit to a set of tools and a run-time stack to get started. Even with a loose or incomplete idea of what you are going to build, you can start to understand risks and weaknesses in design and what you will need to do about them.

At PayPal, for example, every team must go through an initial risk assessment, by filling out an automated risk questionnaire, whenever it begins work on a new app or microservice. One of the key decision points is whether the team is using languages and frameworks that have already been vetted by the security team in another project. Or, is it introducing something new to the organization, technologies that the security team hasn’t seen or checked before? There is a big difference in risk between “just another web or mobile app” built on an approved platform, and a technical experiment using new languages and tools.

Here are some of the issues to understand and assess in an up-front risk review:

-

Do you understand how to use the language(s) and frameworks safely? What security protections are offered in the framework? What needs to be added to make it simple for developers to “do the right thing” by default?

-

Is there good continuous integration and continuous delivery toolchain support for the language(s) and framework, including static code analysis tooling, and dependency management analysis capabilities to catch vulnerabilities in third-party and open source libraries?

-

Is sensitive and confidential data being used or managed in the system? What data is needed, how is it to be handled, and what needs to be audited? Does it need to be stored, and, if so, how? Do you need to make considerations for encryption, tokenization and masking, access control, and auditing?

-

Understanding trust boundaries between this app/service and others: where do controls need to be enforced around authentication, access control, and data quality? What assumptions are being made at a high level in the design?

Review Threats as the Design Changes

After this, threat modeling should be done whenever you make a material change to the system’s attack surface, which we explained earlier. Threat modeling could be added to the acceptance criteria for a story when the story is originally written or when it is elaborated in sprint planning, or as team members work on the story or test the code and recognize the risks.

In Agile and DevOps environments, this means that you will need to do threat modeling much more often than in Waterfall development. But it should also be easier.

In the beginning of a project, when you are first putting in the architectural skeleton of the system and fleshing out the design and interfaces, you will obviously be making lots of changes to the attack surface. It will probably be difficult to understand which risks to focus on, because there is so much to consider, and because the design is continuously changing as you learn more about the problem space and your technology.

You could decide to defer threat modeling until the design details become clearer and more set, recognizing that you are taking on technical debt and security debt that will need to be paid off later. Or keep iterating through the model so that you can keep control over the risks, recognizing that you will be throwing away at least some of this work when you change the design.

Later, as you make smaller, targeted, incremental changes, threat modeling will be easier and faster because you can focus in on the context and the impact of each change. It will be easier to identify risks and problems. And it should also get easier and faster the more often the team goes through the process and steps through the model. At some point, threat modeling will become routine, just another part of how the team thinks and works.

The key to threat modeling in Agile and DevOps is recognizing that because design and coding and deployment are done in a tight, iterative loop, you will be caught up in the same loops when you are assessing technical risks. This means that you can make—and you need to make—threat modeling efficient, simple, pragmatic, and fast.

Getting Value Out of Threat Modeling

The team will need to decide how much threat modeling is needed, and how long to spend on it, trading off risk and time. Like other Agile reviews, the team may decide to time box threat modeling sessions, holding them to a fixed time duration, making the work more predictable and focused, even if this means that the review will not be comprehensive or complete.

Quick-and-dirty threat modeling done often is much better than no threat modeling at all.

Like code reviews, threat modeling doesn’t have to be an intimidating, expensive, and heavyweight process; and it can’t be, if you expect teams to fit it into high-velocity Agile delivery. It doesn’t matter whether you use STRIDE, CAPEC, DESIST (a variant of STRIDE; dispute, elevation of privilege, spoofing, information disclosure, service denial, tampering), attack trees (which we looked at in Chapter 5), Lockheed Martin’s Kill Chain, or simply a careful validation of trust assumptions in your design. The important thing is to find an approach that the team understands and agrees to follow, and that helps it to find real security problems—and solutions to those problems—during design.

In iterative design and development, you will have opportunities to come back and revisit and fill in your design and your threat model, probably many times, so you don’t have to try to exhaustively review the design each time. Do threat modeling the same way that you design and write code. Design a little, then take a bite out of the attack surface in a threat modeling session, write some code and some tests. Fill in or open up the design a bit more, and take another bite. You’re never done threat modeling.

Each time that you come back again to look at the design and how it has been changed, you’ll have a new focus, new information, and more experience, which means that you may ask new questions and find problems that you didn’t see before.

Focus on high-risk threats, especially active threats. And make sure that you cover common attacks.

Minimum Viable Process (and Paperwork)

A common mistake we see when working with teams that are threat modeling for the first time is the focus on documentation, paperwork, and process over outcomes.

It can be very tempting to enforce that every change be documented in a template and that every new feature have the same “lightweight” threat assessment form completed. In fact, sometimes even our lightweight processes distract us from the real value of the activity. If you find your team is more focused on how to complete the diagram or document than the findings of the assessment, revisit your approach.

Even in heavy compliance environments, the process and documentation requirements for threat assessment should be the minimum needed for audit and not the primary focus of the activity.

Remember, for the most part, we are engineers and builders. Use your skills to automate the process and documentation so that you can spend your time on the assessment, where the real value lies.

Common Attack Vectors

Walking through common attack vectors, the basic kinds of attacks that you need to defend against and the technical details of how they actually work, helps to make abstract threats and risks concrete and understandable to developers and operations engineers. It also helps them to be more realistic in thinking about threats so that you focus on defending against the scenarios and types of vulnerabilities that adversaries will try first.

There are a few different ways to learn about common attacks and how they work:

- Scanning

-

Tools like OWASP ZAP, or scanning services like Qualys or WhiteHat Sentinel, which automatically execute common attacks against your application.

- Penetration testing results

-

Take the time to understand what pen testers tried, why, what they found, and why.

- Bug bounties

-

As we’ll see in “Bug Bounties”, bug bounty programs can be an effective, if not always efficient, way to get broad security testing coverage.

- Red Team/Blue Team games

-

Covered in Chapter 13, force defensive Blue Teams to actively watch for, and learn how to respond to, real attacks.

- Attack simulation platforms

-

AttackIQ, SafeBreach, and Verodin automatically execute common network and application attacks, and allow you to script your own attack/response scenarios. These are black boxes that test the effectiveness of your defenses, and allow you to visualize if and how your network is compromised under different conditions.

- Industry analyst reports

-

Reports like Verizon’s annual “Data Breach Investigations Report” provide an overview of the most common and serious attacks seen in the wild.

- OWASP’s Top 10

-

Lists the most serious risks and the most common attacks against web applications and mobile applications. For each of the Top 10 risks, OWASP looks at threat agents (what kind of users to look out for) and common attack vectors and examples of attack scenarios. We’ll look at the OWASP Top 10 again in Chapter 14 because this list of risks has become a reference requirement for many regulations.

- Event logs from your own systems

-

This will show indicators of real-world attacks and whether they are successful.

Common attacks need to be taken into account in design, in testing, in reviews, and in monitoring. You can use your understanding of common attacks to write security stories, to script automated security tests, to guide threat modeling sessions, and to define attack signatures for your security monitoring and defense systems.

Key Takeaways

To effectively defend against adversaries and their threats against your organization and system, you need to take the following measures:

-

Threat intelligence needs to be incorporated into Agile and DevOps feedback loops.

-

One of the best sources of threat intelligence is what is happening to your production systems right now. Use this information in attack-driven defense to find and plug holes before attackers find and exploit them.

-

Although Agile teams often don’t spend a lot of time in up-front design, before the team commits to a technology platform and runtime stack, work with them to understand security risks in their approach and how to minimize them.

-

In Agile and especially DevOps environments, the system’s attack surface is continuously changing. By understanding the attack surface and the impact of changes that you are making, you can identify risks and potential weaknesses that need to be addressed.

-

Because the attack surface is continuously changing, you need to do threat modeling on a continuous basis. Threat modeling has to be done a lightweight, incremental, and iterative way.

-

Make sure that team understands common attacks like the OWASP Top 10, and how to deal with them in design, testing, and monitoring.

1 IEEE Center for Secure Design, “Avoiding the Top 10 Software Security Design Flaws”, 2014.

2 Read Bill Buford’s Heat: An Amateur’s Adventures as Kitchen Slave, Line Cook, Pasta-Maker, and Apprentice to a Dante-Quoting Butcher in Tuscany (Vintage) to get an appreciation of just how hard this is.