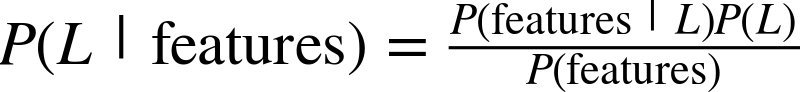

Chapter 5. Machine Learning

In many ways, machine learning is the primary means by which data science manifests itself to the broader world. Machine learning is where these computational and algorithmic skills of data science meet the statistical thinking of data science, and the result is a collection of approaches to inference and data exploration that are not about effective theory so much as effective computation.

The term “machine learning” is sometimes thrown around as if it is some kind of magic pill: apply machine learning to your data, and all your problems will be solved! As you might expect, the reality is rarely this simple. While these methods can be incredibly powerful, to be effective they must be approached with a firm grasp of the strengths and weaknesses of each method, as well as a grasp of general concepts such as bias and variance, overfitting and underfitting, and more.

This chapter will dive into practical aspects of machine learning, primarily using Python’s Scikit-Learn package. This is not meant to be a comprehensive introduction to the field of machine learning; that is a large subject and necessitates a more technical approach than we take here. Nor is it meant to be a comprehensive manual for the use of the Scikit-Learn package (for this, see “Further Machine Learning Resources”). Rather, the goals of this chapter are:

-

To introduce the fundamental vocabulary and concepts of machine learning.

-

To introduce the Scikit-Learn API and show some examples of its use.

-

To take a deeper dive into the details of several of the most important machine learning approaches, and develop an intuition into how they work and when and where they are applicable.

Much of this material is drawn from the Scikit-Learn tutorials and workshops I have given on several occasions at PyCon, SciPy, PyData, and other conferences. Any clarity in the following pages is likely due to the many workshop participants and co-instructors who have given me valuable feedback on this material over the years!

Finally, if you are seeking a more comprehensive or technical treatment of any of these subjects, I’ve listed several resources and references in “Further Machine Learning Resources”.

What Is Machine Learning?

Before we take a look at the details of various machine learning methods, let’s start by looking at what machine learning is, and what it isn’t. Machine learning is often categorized as a subfield of artificial intelligence, but I find that categorization can often be misleading at first brush. The study of machine learning certainly arose from research in this context, but in the data science application of machine learning methods, it’s more helpful to think of machine learning as a means of building models of data.

Fundamentally, machine learning involves building mathematical models to help understand data. “Learning” enters the fray when we give these models tunable parameters that can be adapted to observed data; in this way the program can be considered to be “learning” from the data. Once these models have been fit to previously seen data, they can be used to predict and understand aspects of newly observed data. I’ll leave to the reader the more philosophical digression regarding the extent to which this type of mathematical, model-based “learning” is similar to the “learning” exhibited by the human brain.

Understanding the problem setting in machine learning is essential to using these tools effectively, and so we will start with some broad categorizations of the types of approaches we’ll discuss here.

Categories of Machine Learning

At the most fundamental level, machine learning can be categorized into two main types: supervised learning and unsupervised learning.

Supervised learning involves somehow modeling the relationship between measured features of data and some label associated with the data; once this model is determined, it can be used to apply labels to new, unknown data. This is further subdivided into classification tasks and regression tasks: in classification, the labels are discrete categories, while in regression, the labels are continuous quantities. We will see examples of both types of supervised learning in the following section.

Unsupervised learning involves modeling the features of a dataset without reference to any label, and is often described as “letting the dataset speak for itself.” These models include tasks such as clustering and dimensionality reduction. Clustering algorithms identify distinct groups of data, while dimensionality reduction algorithms search for more succinct representations of the data. We will see examples of both types of unsupervised learning in the following section.

In addition, there are so-called semi-supervised learning methods, which fall somewhere between supervised learning and unsupervised learning. Semi-supervised learning methods are often useful when only incomplete labels are available.

Qualitative Examples of Machine Learning Applications

To make these ideas more concrete, let’s take a look at a few very simple examples of a machine learning task. These examples are meant to give an intuitive, non-quantitative overview of the types of machine learning tasks we will be looking at in this chapter. In later sections, we will go into more depth regarding the particular models and how they are used. For a preview of these more technical aspects, you can find the Python source that generates the figures in the online appendix.

Classification: Predicting discrete labels

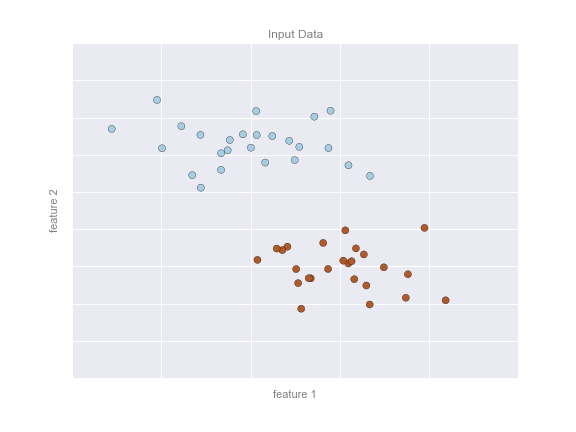

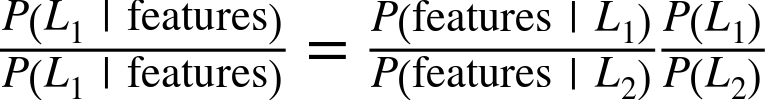

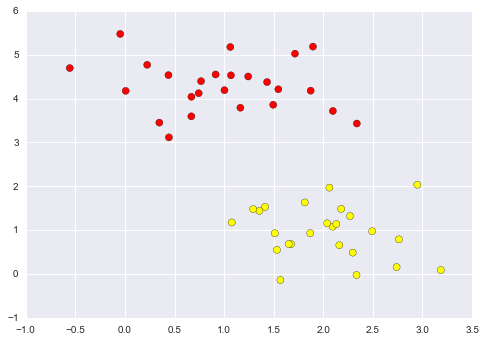

We will first take a look at a simple classification task, in which you are given a set of labeled points and want to use these to classify some unlabeled points.

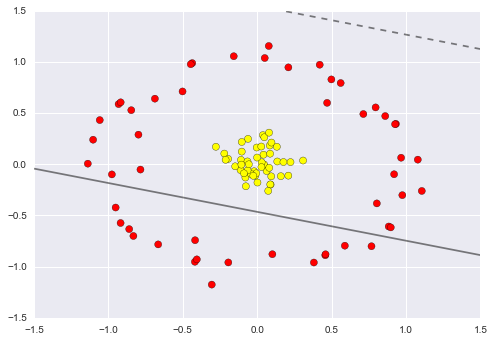

Imagine that we have the data shown in Figure 5-1 (the code used to generate this figure, and all figures in this section, is available in the online appendix).

Figure 5-1. A simple data set for classification

Here we have two-dimensional data; that is, we have two features for each point, represented by the (x,y) positions of the points on the plane. In addition, we have one of two class labels for each point, here represented by the colors of the points. From these features and labels, we would like to create a model that will let us decide whether a new point should be labeled “blue” or “red.”

There are a number of possible models for such a classification task, but here we will use an extremely simple one. We will make the assumption that the two groups can be separated by drawing a straight line through the plane between them, such that points on each side of the line fall in the same group. Here the model is a quantitative version of the statement “a straight line separates the classes,” while the model parameters are the particular numbers describing the location and orientation of that line for our data. The optimal values for these model parameters are learned from the data (this is the “learning” in machine learning), which is often called training the model.

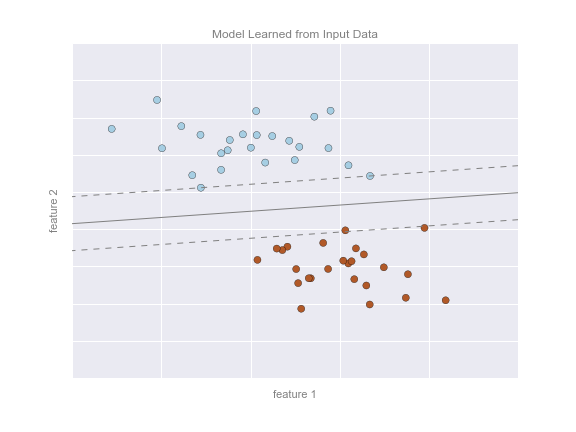

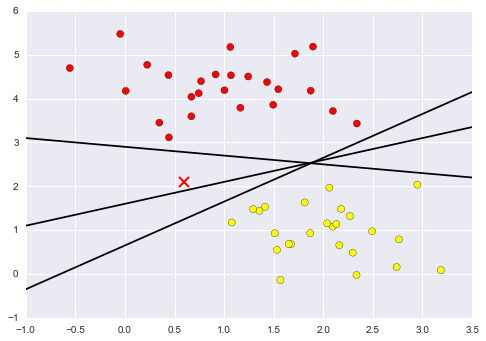

Figure 5-2 is a visual representation of what the trained model looks like for this data.

Figure 5-2. A simple classification model

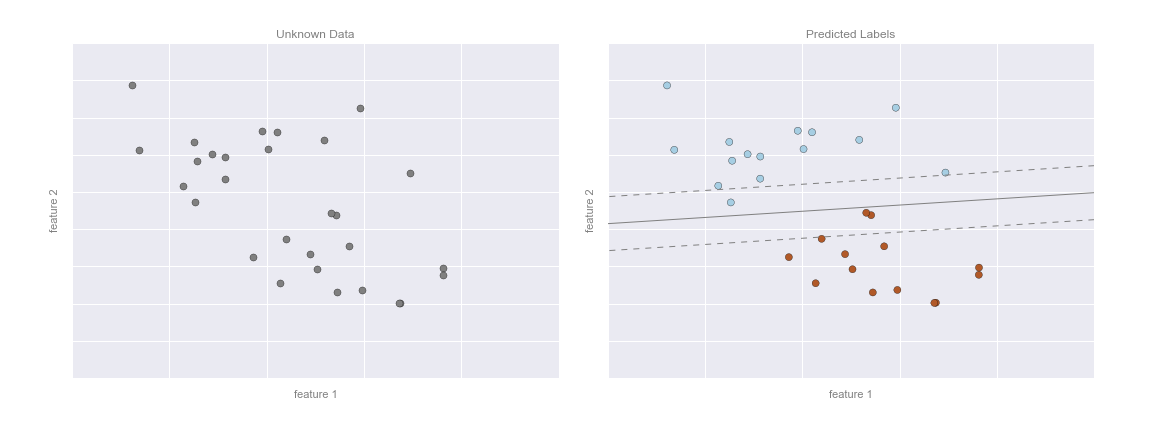

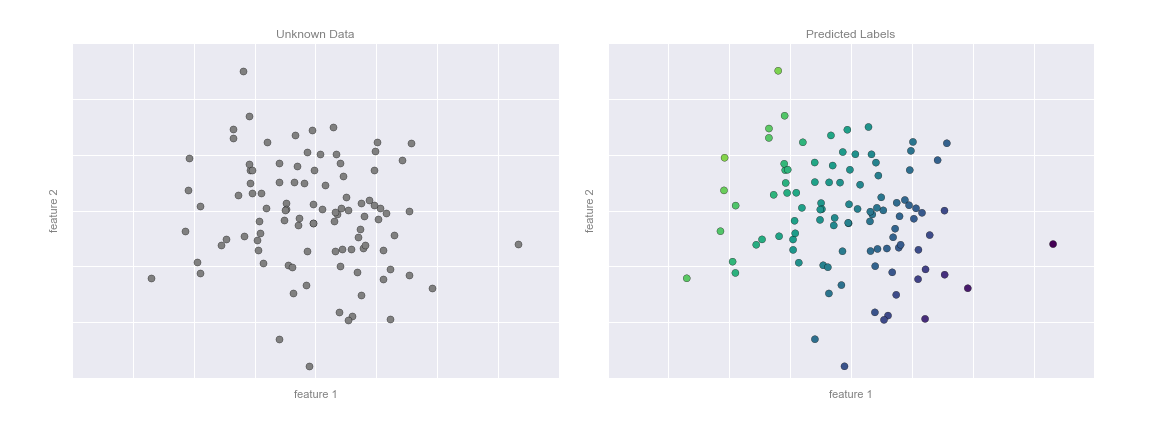

Now that this model has been trained, it can be generalized to new, unlabeled data. In other words, we can take a new set of data, draw this model line through it, and assign labels to the new points based on this model. This stage is usually called prediction. See Figure 5-3.

Figure 5-3. Applying a classification model to new data

This is the basic idea of a classification task in machine learning, where “classification” indicates that the data has discrete class labels. At first glance this may look fairly trivial: it would be relatively easy to simply look at this data and draw such a discriminatory line to accomplish this classification. A benefit of the machine learning approach, however, is that it can generalize to much larger datasets in many more dimensions.

For example, this is similar to the task of automated spam detection for email; in this case, we might use the following features and labels:

-

feature 1, feature 2, etc.

normalized counts of

important words or phrases (“Viagra,” “Nigerian prince,” etc.)

normalized counts of

important words or phrases (“Viagra,” “Nigerian prince,” etc.) -

label

“spam” or “not spam”

“spam” or “not spam”

For the training set, these labels might be determined by individual inspection of a small representative sample of emails; for the remaining emails, the label would be determined using the model. For a suitably trained classification algorithm with enough well-constructed features (typically thousands or millions of words or phrases), this type of approach can be very effective. We will see an example of such text-based classification in “In Depth: Naive Bayes Classification”.

Some important classification algorithms that we will discuss in more detail are Gaussian naive Bayes (see “In Depth: Naive Bayes Classification”), support vector machines (see “In-Depth: Support Vector Machines”), and random forest classification (see “In-Depth: Decision Trees and Random Forests”).

Regression: Predicting continuous labels

In contrast with the discrete labels of a classification algorithm, we will next look at a simple regression task in which the labels are continuous quantities.

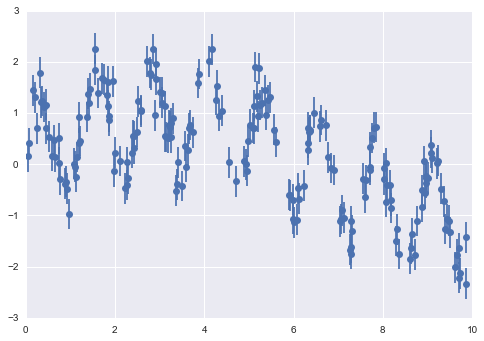

Consider the data shown in Figure 5-4, which consists of a set of points, each with a continuous label.

Figure 5-4. A simple dataset for regression

As with the classification example, we have two-dimensional data; that is, there are two features describing each data point. The color of each point represents the continuous label for that point.

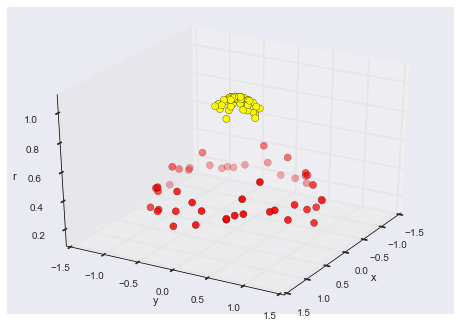

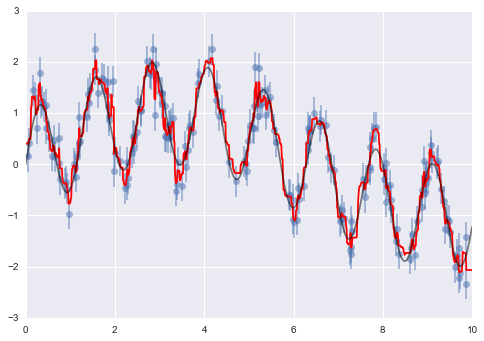

There are a number of possible regression models we might use for this type of data, but here we will use a simple linear regression to predict the points. This simple linear regression model assumes that if we treat the label as a third spatial dimension, we can fit a plane to the data. This is a higher-level generalization of the well-known problem of fitting a line to data with two coordinates.

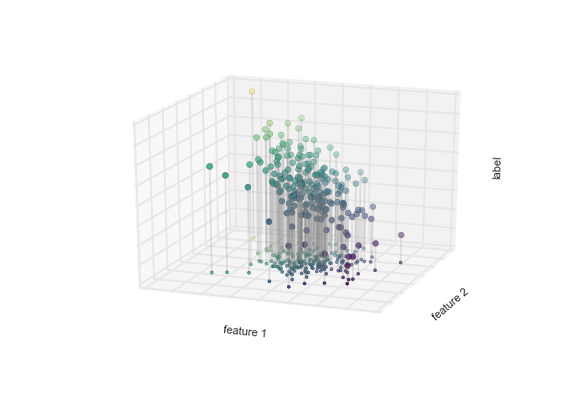

We can visualize this setup as shown in Figure 5-5.

Figure 5-5. A three-dimensional view of the regression data

Notice that the feature 1–feature 2 plane here is the same as in the two-dimensional plot from before; in this case, however, we have represented the labels by both color and three-dimensional axis position. From this view, it seems reasonable that fitting a plane through this three-dimensional data would allow us to predict the expected label for any set of input parameters. Returning to the two-dimensional projection, when we fit such a plane we get the result shown in Figure 5-6.

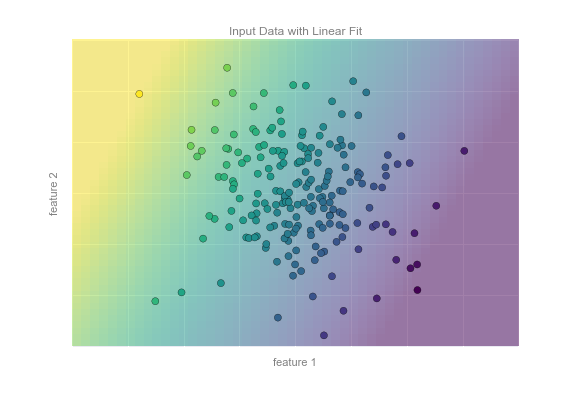

Figure 5-6. A representation of the regression model

This plane of fit gives us what we need to predict labels for new points. Visually, we find the results shown in Figure 5-7.

Figure 5-7. Applying the regression model to new data

As with the classification example, this may seem rather trivial in a low number of dimensions. But the power of these methods is that they can be straightforwardly applied and evaluated in the case of data with many, many features.

For example, this is similar to the task of computing the distance to galaxies observed through a telescope—in this case, we might use the following features and labels:

-

feature 1, feature 2, etc.

brightness of each

galaxy at one of several wavelengths or colors

brightness of each

galaxy at one of several wavelengths or colors -

label

distance or redshift of the galaxy

distance or redshift of the galaxy

The distances for a small number of these galaxies might be determined through an independent set of (typically more expensive) observations. We could then estimate distances to remaining galaxies using a suitable regression model, without the need to employ the more expensive observation across the entire set. In astronomy circles, this is known as the “photometric redshift” problem.

Some important regression algorithms that we will discuss are linear regression (see “In Depth: Linear Regression”), support vector machines (see “In-Depth: Support Vector Machines”), and random forest regression (see “In-Depth: Decision Trees and Random Forests”).

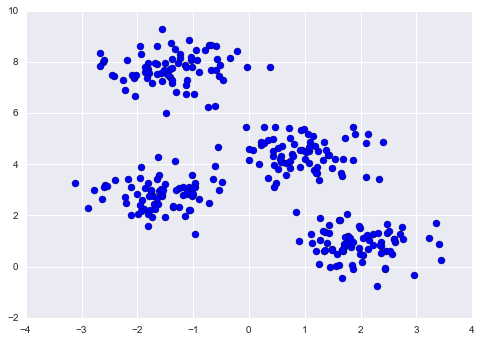

Clustering: Inferring labels on unlabeled data

The classification and regression illustrations we just looked at are examples of supervised learning algorithms, in which we are trying to build a model that will predict labels for new data. Unsupervised learning involves models that describe data without reference to any known labels.

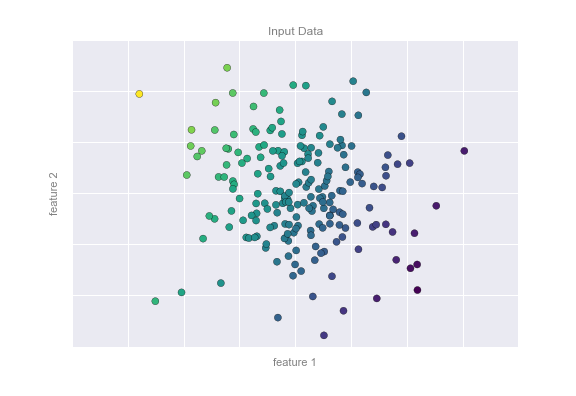

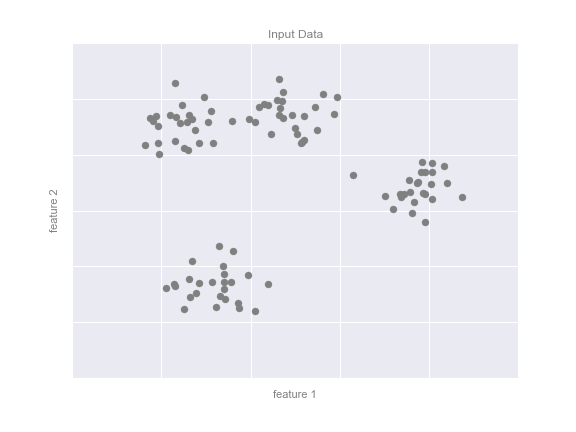

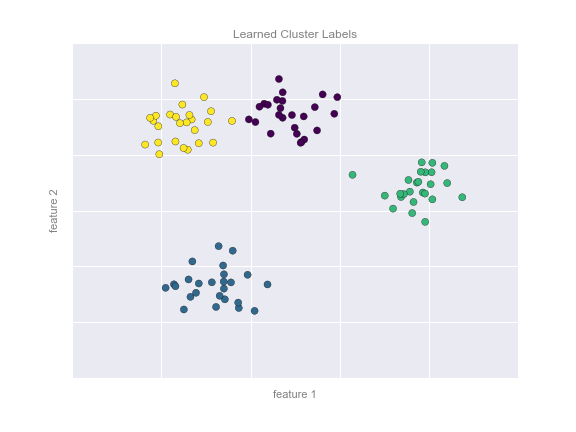

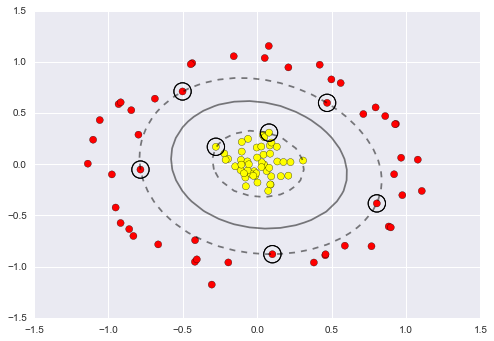

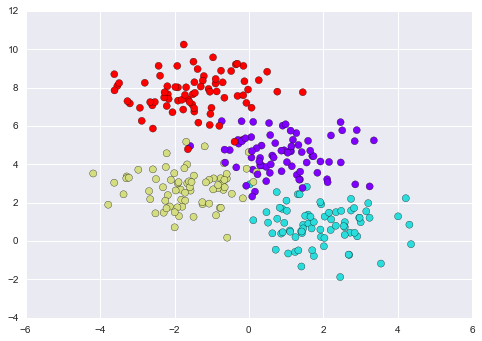

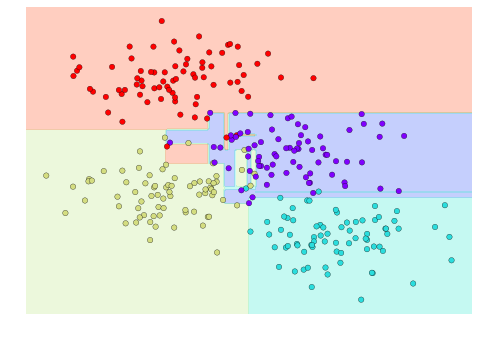

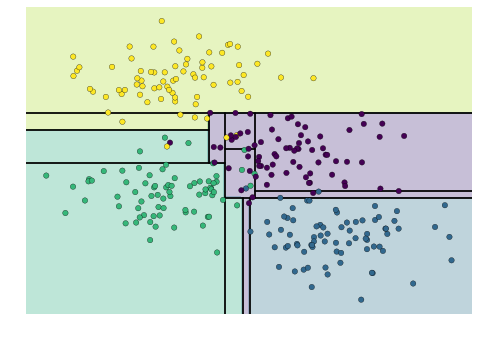

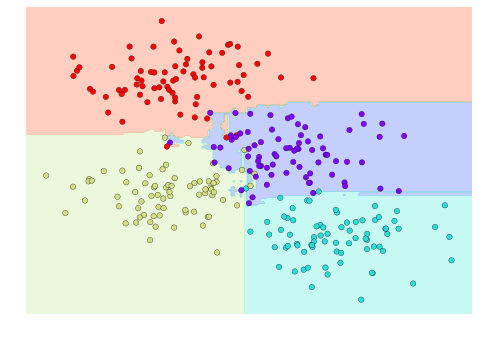

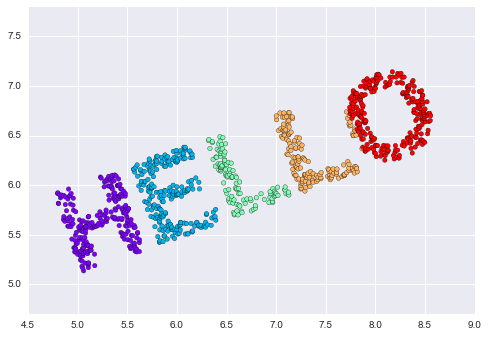

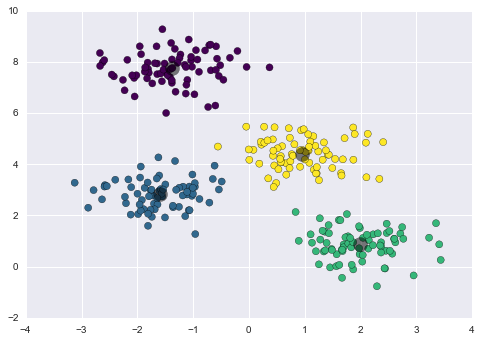

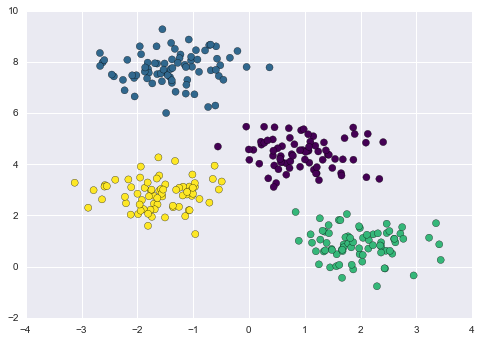

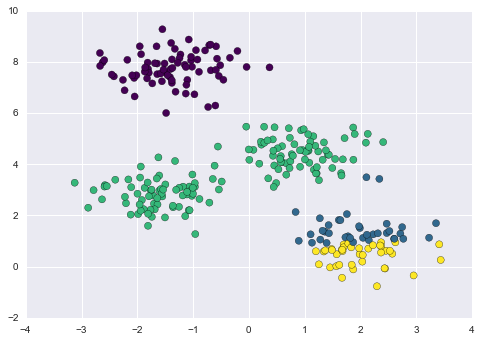

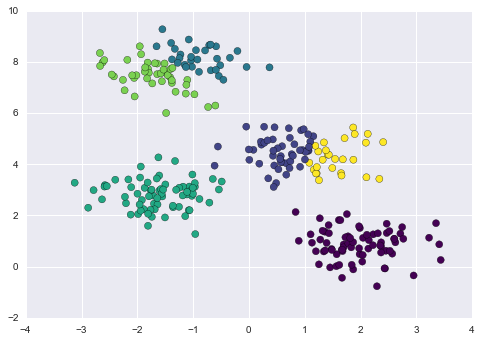

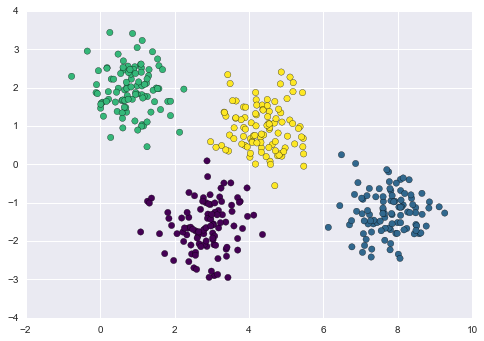

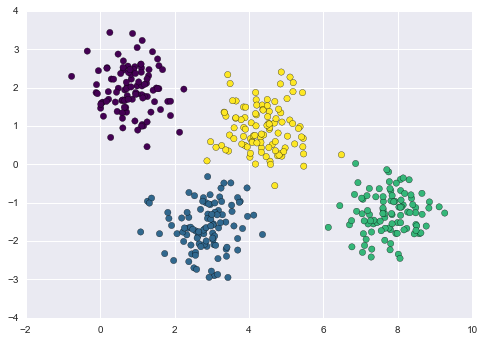

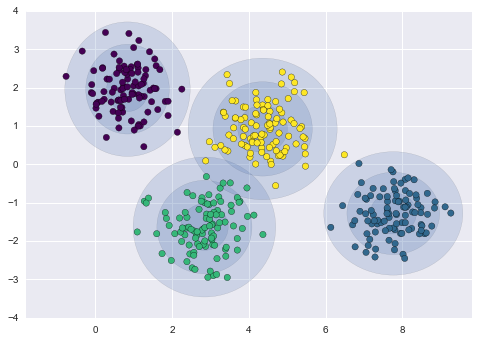

One common case of unsupervised learning is “clustering,” in which data is automatically assigned to some number of discrete groups. For example, we might have some two-dimensional data like that shown in Figure 5-8.

Figure 5-8. Example data for clustering

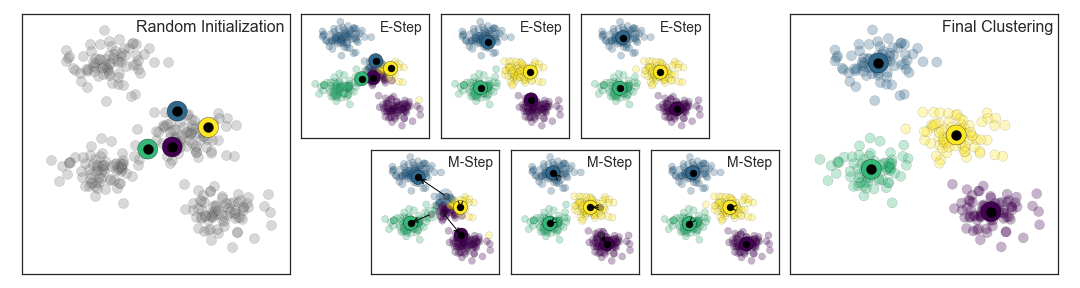

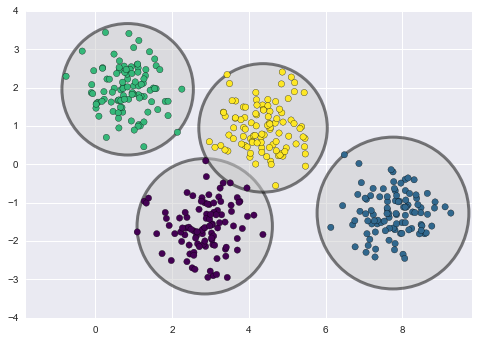

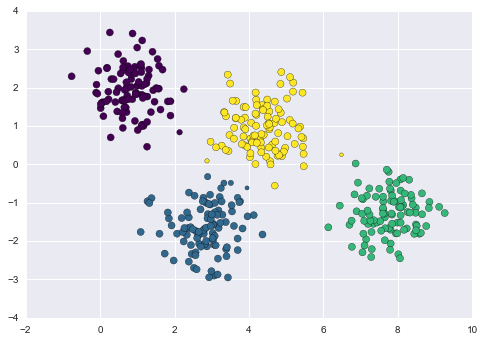

By eye, it is clear that each of these points is part of a distinct group. Given this input, a clustering model will use the intrinsic structure of the data to determine which points are related. Using the very fast and intuitive k-means algorithm (see “In Depth: k-Means Clustering”), we find the clusters shown in Figure 5-9.

k-means fits a model consisting of k cluster centers; the optimal centers are assumed to be those that minimize the distance of each point from its assigned center. Again, this might seem like a trivial exercise in two dimensions, but as our data becomes larger and more complex, such clustering algorithms can be employed to extract useful information from the dataset.

We will discuss the k-means algorithm in more depth in “In Depth: k-Means Clustering”. Other important clustering algorithms include Gaussian mixture models (see “In Depth: Gaussian Mixture Models”) and spectral clustering (see Scikit-Learn’s clustering documentation).

Figure 5-9. Data labeled with a k-means clustering model

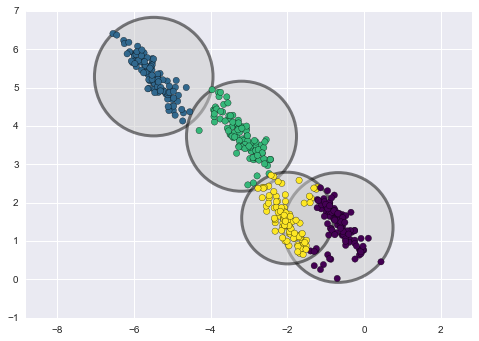

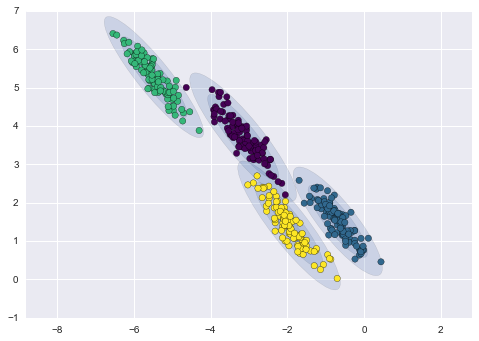

Dimensionality reduction: Inferring structure of unlabeled data

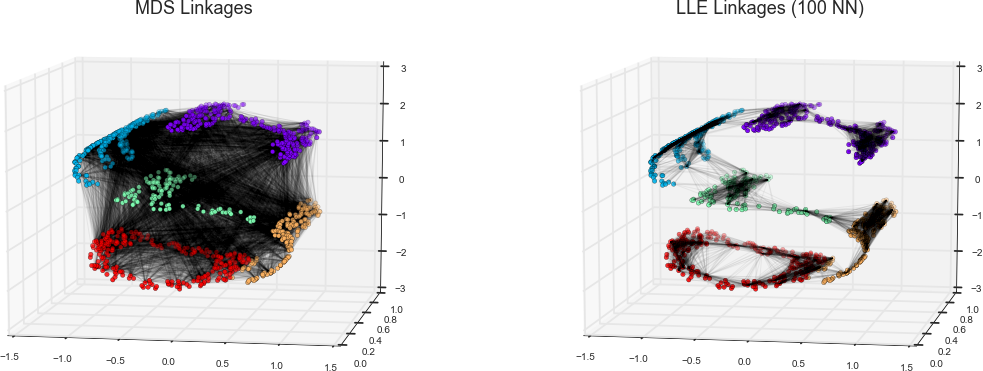

Dimensionality reduction is another example of an unsupervised algorithm, in which labels or other information are inferred from the structure of the dataset itself. Dimensionality reduction is a bit more abstract than the examples we looked at before, but generally it seeks to pull out some low-dimensional representation of data that in some way preserves relevant qualities of the full dataset. Different dimensionality reduction routines measure these relevant qualities in different ways, as we will see in “In-Depth: Manifold Learning”.

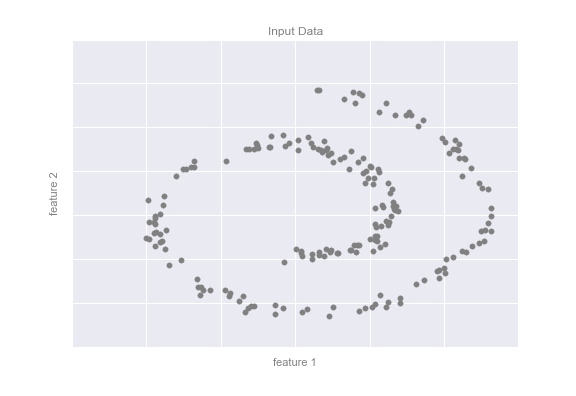

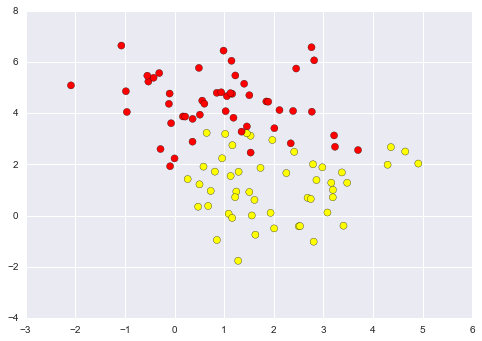

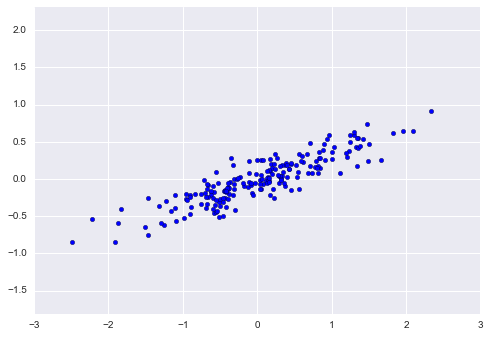

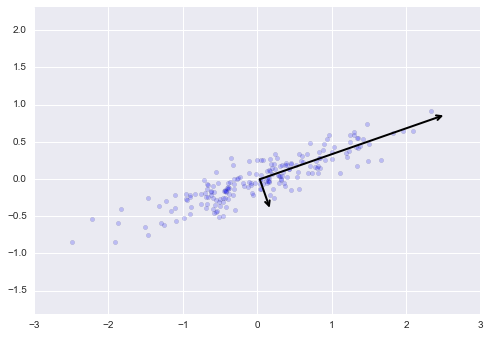

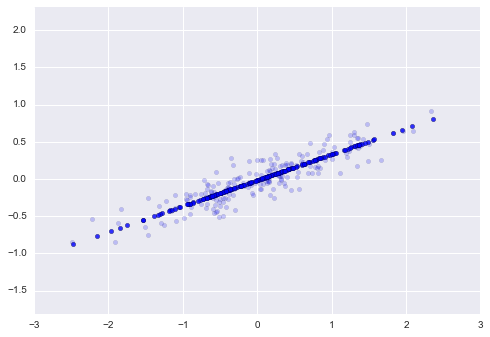

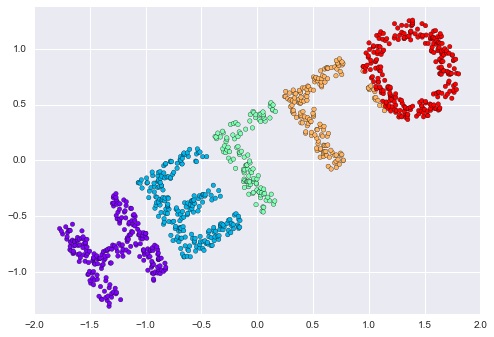

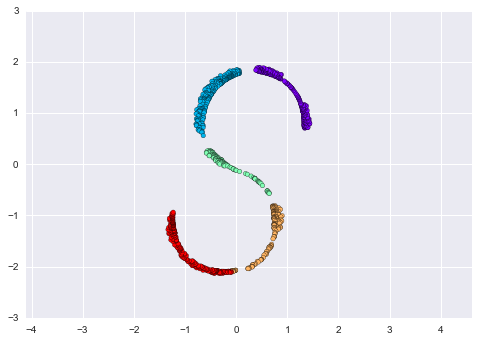

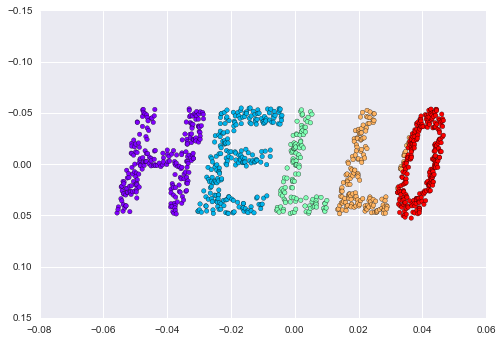

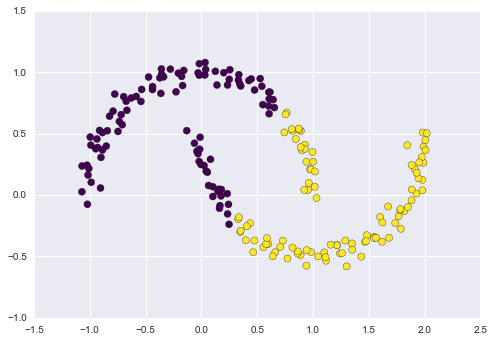

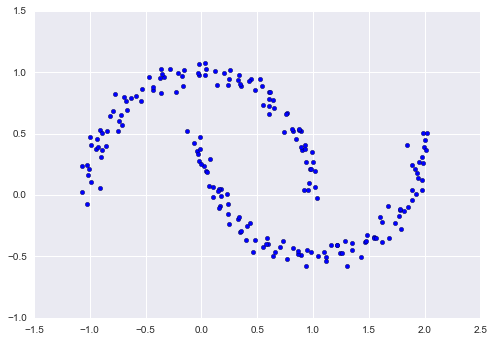

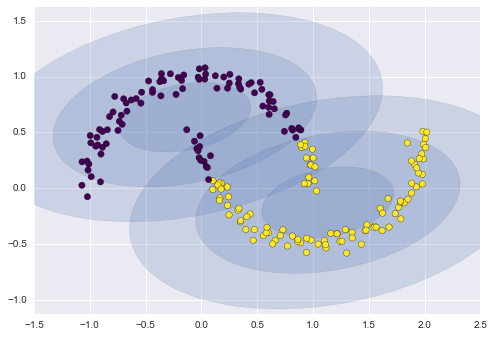

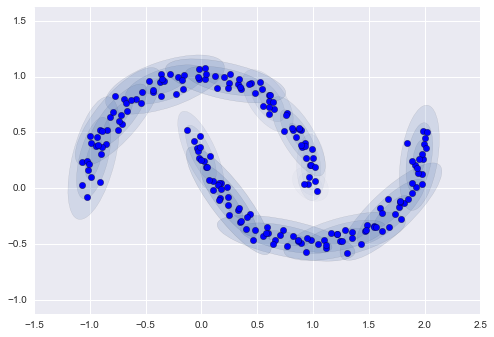

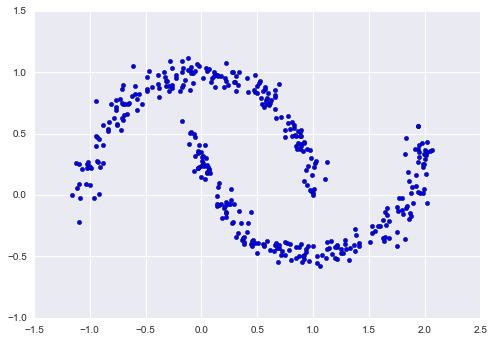

As an example of this, consider the data shown in Figure 5-10.

Visually, it is clear that there is some structure in this data: it is drawn from a one-dimensional line that is arranged in a spiral within this two-dimensional space. In a sense, you could say that this data is “intrinsically” only one dimensional, though this one-dimensional data is embedded in higher-dimensional space. A suitable dimensionality reduction model in this case would be sensitive to this nonlinear embedded structure, and be able to pull out this lower-dimensionality representation.

Figure 5-10. Example data for dimensionality reduction

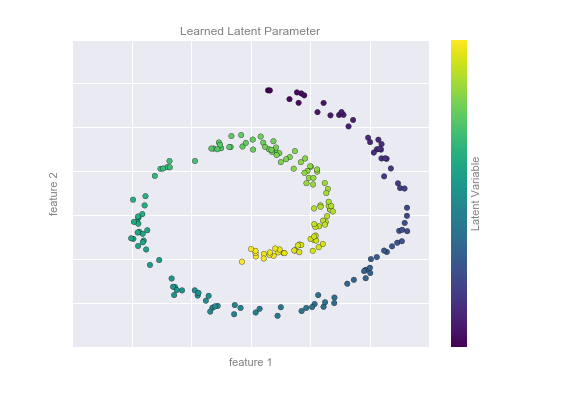

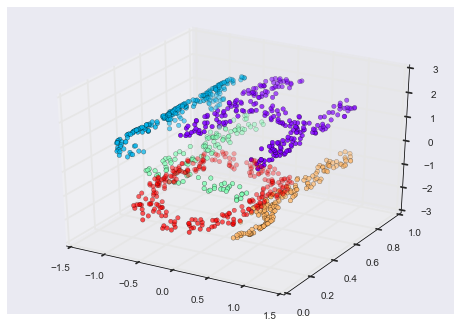

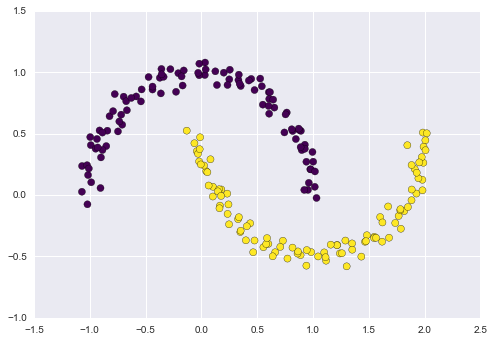

Figure 5-11 presents a visualization of the results of the Isomap algorithm, a manifold learning algorithm that does exactly this.

Figure 5-11. Data with a label learned via dimensionality reduction

Notice that the colors (which represent the extracted one-dimensional latent variable) change uniformly along the spiral, which indicates that the algorithm did in fact detect the structure we saw by eye. As with the previous examples, the power of dimensionality reduction algorithms becomes clearer in higher-dimensional cases. For example, we might wish to visualize important relationships within a dataset that has 100 or 1,000 features. Visualizing 1,000-dimensional data is a challenge, and one way we can make this more manageable is to use a dimensionality reduction technique to reduce the data to two or three dimensions.

Some important dimensionality reduction algorithms that we will discuss are principal component analysis (see “In Depth: Principal Component Analysis”) and various manifold learning algorithms, including Isomap and locally linear embedding (see “In-Depth: Manifold Learning”).

Summary

Here we have seen a few simple examples of some of the basic types of machine learning approaches. Needless to say, there are a number of important practical details that we have glossed over, but I hope this section was enough to give you a basic idea of what types of problems machine learning approaches can solve.

In short, we saw the following:

- Supervised learning

-

Models that can predict labels based on labeled training data

- Classification

-

Models that predict labels as two or more discrete categories

- Regression

-

Models that predict continuous labels

- Unsupervised learning

-

Models that identify structure in unlabeled data

- Clustering

-

Models that detect and identify distinct groups in the data

- Dimensionality reduction

-

Models that detect and identify lower-dimensional structure in higher-dimensional data

In the following sections we will go into much greater depth within these categories, and see some more interesting examples of where these concepts can be useful.

All of the figures in the preceding discussion are generated based on actual machine learning computations; the code behind them can be found in the online appendix.

Introducing Scikit-Learn

There are several Python libraries that provide solid implementations of a range of machine learning algorithms. One of the best known is Scikit-Learn, a package that provides efficient versions of a large number of common algorithms. Scikit-Learn is characterized by a clean, uniform, and streamlined API, as well as by very useful and complete online documentation. A benefit of this uniformity is that once you understand the basic use and syntax of Scikit-Learn for one type of model, switching to a new model or algorithm is very straightforward.

This section provides an overview of the Scikit-Learn API; a solid understanding of these API elements will form the foundation for understanding the deeper practical discussion of machine learning algorithms and approaches in the following chapters.

We will start by covering data representation in Scikit-Learn, followed by covering the Estimator API, and finally go through a more interesting example of using these tools for exploring a set of images of handwritten digits.

Data Representation in Scikit-Learn

Machine learning is about creating models from data: for that reason, we’ll start by discussing how data can be represented in order to be understood by the computer. The best way to think about data within Scikit-Learn is in terms of tables of data.

Data as table

A basic table is a two-dimensional grid of data, in which the rows

represent individual elements of the dataset, and the columns represent

quantities related to each of these elements. For example, consider the

Iris dataset,

famously analyzed by Ronald Fisher in 1936. We can download this dataset in the form of a Pandas DataFrame using the Seaborn library:

In[1]:importseabornassnsiris=sns.load_dataset('iris')iris.head()

Out[1]: sepal_length sepal_width petal_length petal_width species

0 5.1 3.5 1.4 0.2 setosa

1 4.9 3.0 1.4 0.2 setosa

2 4.7 3.2 1.3 0.2 setosa

3 4.6 3.1 1.5 0.2 setosa

4 5.0 3.6 1.4 0.2 setosa

Here each row of the data refers to a single observed flower, and the

number of rows is the total number of flowers in the dataset. In

general, we will refer to the rows of the matrix as samples, and the

number of rows as n_samples.

Likewise, each column of the data refers to a particular quantitative

piece of information that describes each sample. In general, we will

refer to the columns of the matrix as features, and the number of

columns as n_features.

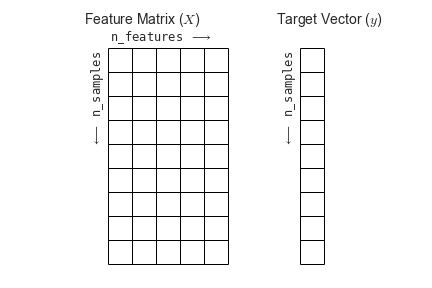

Features matrix

This table layout makes clear that the information can be thought of as

a two-dimensional numerical array or matrix, which we will call the

features matrix. By convention, this features matrix is often stored

in a variable named X. The features matrix is assumed to be

two-dimensional, with shape [n_samples, n_features], and is most often

contained in a NumPy array or a Pandas DataFrame, though some Scikit-Learn

models also accept SciPy sparse matrices.

The samples (i.e., rows) always refer to the individual objects described by the dataset. For example, the sample might be a flower, a person, a document, an image, a sound file, a video, an astronomical object, or anything else you can describe with a set of quantitative measurements.

The features (i.e., columns) always refer to the distinct observations that describe each sample in a quantitative manner. Features are generally real-valued, but may be Boolean or discrete-valued in some cases.

Target array

In addition to the feature matrix X, we also generally work with a

label or target array, which by convention we will usually call y.

The target array is usually one dimensional, with length n_samples,

and is generally contained in a NumPy array or Pandas Series. The target

array may have continuous numerical values, or discrete classes/labels.

While some Scikit-Learn estimators do handle multiple target values in

the form of a two-dimensional [n_samples, n_targets] target array, we

will primarily be working with the common case of a one-dimensional

target array.

Often one point of confusion is how the target array differs from the

other features columns. The distinguishing feature of the target array

is that it is usually the quantity we want to predict from the data:

in statistical terms, it is the dependent variable. For example, in the

preceding data we may wish to construct a model that can predict the species

of flower based on the other measurements; in this case, the species

column would be considered the feature.

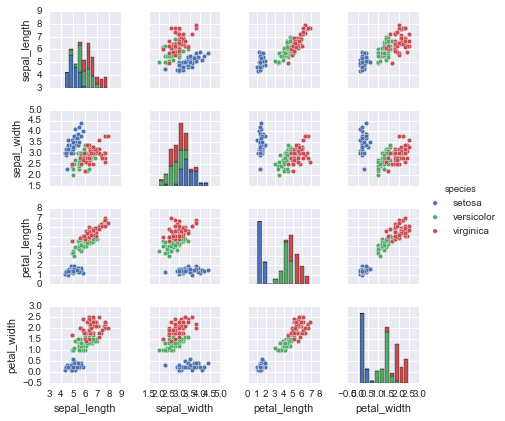

With this target array in mind, we can use Seaborn (discussed earlier in “Visualization with Seaborn”) to conveniently visualize the data (see Figure 5-12):

In[2]:%matplotlibinlineimportseabornassns;sns.set()sns.pairplot(iris,hue='species',size=1.5);

Figure 5-12. A visualization of the Iris dataset

For use in Scikit-Learn, we will extract the features matrix and target

array from the DataFrame, which we can do using some of the Pandas

DataFrame operations discussed in Chapter 3:

In[3]:X_iris=iris.drop('species',axis=1)X_iris.shape

Out[3]: (150, 4)

In[4]:y_iris=iris['species']y_iris.shape

Out[4]: (150,)

To summarize, the expected layout of features and target values is visualized in Figure 5-13.

Figure 5-13. Scikit-Learn’s data layout

With this data properly formatted, we can move on to consider the estimator API of Scikit-Learn.

Scikit-Learn’s Estimator API

The Scikit-Learn API is designed with the following guiding principles in mind, as outlined in the Scikit-Learn API paper:

- Consistency

-

All objects share a common interface drawn from a limited set of methods, with consistent documentation.

- Inspection

-

All specified parameter values are exposed as public attributes.

- Limited object hierarchy

-

Only algorithms are represented by Python classes; datasets are represented in standard formats (NumPy arrays, Pandas

DataFrames, SciPy sparse matrices) and parameter names use standard Python strings. - Composition

-

Many machine learning tasks can be expressed as sequences of more fundamental algorithms, and Scikit-Learn makes use of this wherever possible.

- Sensible defaults

-

When models require user-specified parameters, the library defines an appropriate default value.

In practice, these principles make Scikit-Learn very easy to use, once the basic principles are understood. Every machine learning algorithm in Scikit-Learn is implemented via the Estimator API, which provides a consistent interface for a wide range of machine learning applications.

Basics of the API

Most commonly, the steps in using the Scikit-Learn estimator API are as follows (we will step through a handful of detailed examples in the sections that follow):

-

Choose a class of model by importing the appropriate estimator class from Scikit-Learn.

-

Choose model hyperparameters by instantiating this class with desired values.

-

Arrange data into a features matrix and target vector following the discussion from before.

-

Fit the model to your data by calling the

fit()method of the model instance. -

Apply the model to new data:

-

For supervised learning, often we predict labels for unknown data using the

predict()method. -

For unsupervised learning, we often transform or infer properties of the data using the

transform()orpredict()method.

-

We will now step through several simple examples of applying supervised and unsupervised learning methods.

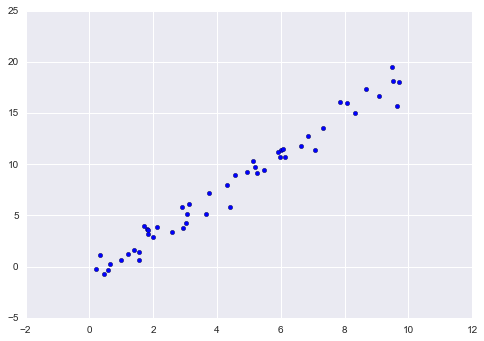

Supervised learning example: Simple linear regression

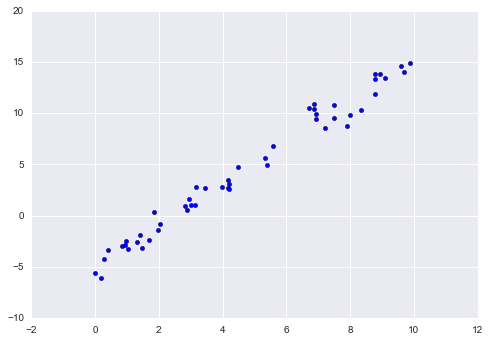

As an example of this process, let’s consider a simple linear regression—that is, the common case of fitting a line to  data. We will use the following simple data for our regression example (Figure 5-14):

data. We will use the following simple data for our regression example (Figure 5-14):

In[5]:importmatplotlib.pyplotaspltimportnumpyasnprng=np.random.RandomState(42)x=10*rng.rand(50)y=2*x-1+rng.randn(50)plt.scatter(x,y);

Figure 5-14. Data for linear regression

With this data in place, we can use the recipe outlined earlier. Let’s walk through the process:

-

Choose a class of model.

In Scikit-Learn, every class of model is represented by a Python class. So, for example, if we would like to compute a simple linear regression model, we can import the linear regression class:

In[6]:fromsklearn.linear_modelimportLinearRegressionNote that other, more general linear regression models exist as well; you can read more about them in the

sklearn.linear_modelmodule documentation. -

Choose model hyperparameters.

An important point is that a class of model is not the same as an instance of a model.

Once we have decided on our model class, there are still some options open to us. Depending on the model class we are working with, we might need to answer one or more questions like the following:

-

Would we like to fit for the offset (i.e., intercept)?

-

Would we like the model to be normalized?

-

Would we like to preprocess our features to add model flexibility?

-

What degree of regularization would we like to use in our model?

-

How many model components would we like to use?

These are examples of the important choices that must be made once the model class is selected. These choices are often represented as hyperparameters, or parameters that must be set before the model is fit to data. In Scikit-Learn, we choose hyperparameters by passing values at model instantiation. We will explore how you can quantitatively motivate the choice of hyperparameters in “Hyperparameters and Model Validation”.

For our linear regression example, we can instantiate the

LinearRegressionclass and specify that we would like to fit the intercept using thefit_intercepthyperparameter:In[7]:model=LinearRegression(fit_intercept=True)modelOut[7]: LinearRegression(copy_X=True, fit_intercept=True, n_jobs=1, normalize=False)Keep in mind that when the model is instantiated, the only action is the storing of these hyperparameter values. In particular, we have not yet applied the model to any data: the Scikit-Learn API makes very clear the distinction between choice of model and application of model to data.

-

-

Arrange data into a features matrix and target vector.

Previously we detailed the Scikit-Learn data representation, which requires a two-dimensional features matrix and a one-dimensional target array. Here our target variable

yis already in the correct form (a length-n_samplesarray), but we need to massage the dataxto make it a matrix of size[n_samples, n_features]. In this case, this amounts to a simple reshaping of the one-dimensional array:In[8]:X=x[:,np.newaxis]X.shapeOut[8]: (50, 1)

-

Fit the model to your data.

Now it is time to apply our model to data. This can be done with the

fit()method of the model:In[9]:model.fit(X,y)Out[9]: LinearRegression(copy_X=True, fit_intercept=True, n_jobs=1, normalize=False)This

fit()command causes a number of model-dependent internal computations to take place, and the results of these computations are stored in model-specific attributes that the user can explore. In Scikit-Learn, by convention all model parameters that were learned during thefit()process have trailing underscores; for example, in this linear model, we have the following:In[10]:model.coef_Out[10]: array([ 1.9776566])

In[11]:model.intercept_Out[11]: -0.90331072553111635

These two parameters represent the slope and intercept of the simple linear fit to the data. Comparing to the data definition, we see that they are very close to the input slope of 2 and intercept of –1.

One question that frequently comes up regards the uncertainty in such internal model parameters. In general, Scikit-Learn does not provide tools to draw conclusions from internal model parameters themselves: interpreting model parameters is much more a statistical modeling question than a machine learning question. Machine learning rather focuses on what the model predicts. If you would like to dive into the meaning of fit parameters within the model, other tools are available, including the StatsModels Python package.

-

Predict labels for unknown data.

Once the model is trained, the main task of supervised machine learning is to evaluate it based on what it says about new data that was not part of the training set. In Scikit-Learn, we can do this using the

predict()method. For the sake of this example, our “new data” will be a grid of x values, and we will ask what y values the model predicts:In[12]:xfit=np.linspace(-1,11)As before, we need to coerce these x values into a

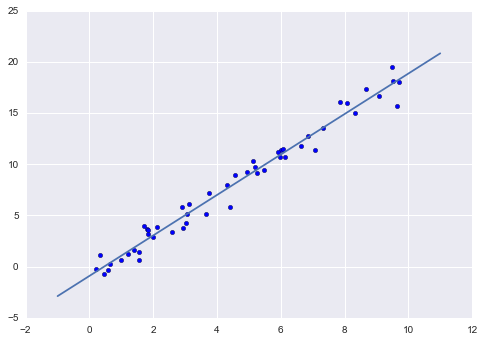

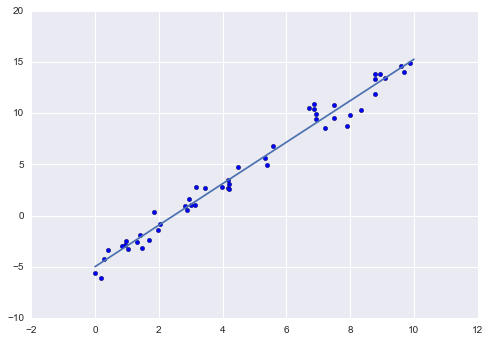

[n_samples, n_features]features matrix, after which we can feed it to the model:In[13]:Xfit=xfit[:,np.newaxis]yfit=model.predict(Xfit)Finally, let’s visualize the results by plotting first the raw data, and then this model fit (Figure 5-15):

In[14]:plt.scatter(x,y)plt.plot(xfit,yfit);Typically one evaluates the efficacy of the model by comparing its results to some known baseline, as we will see in the next example.

Figure 5-15. A simple linear regression fit to the data

Supervised learning example: Iris classification

Let’s take a look at another example of this process, using the Iris dataset we discussed earlier. Our question will be this: given a model trained on a portion of the Iris data, how well can we predict the remaining labels?

For this task, we will use an extremely simple generative model known as Gaussian naive Bayes, which proceeds by assuming each class is drawn from an axis-aligned Gaussian distribution (see “In Depth: Naive Bayes Classification” for more details). Because it is so fast and has no hyperparameters to choose, Gaussian naive Bayes is often a good model to use as a baseline classification, before you explore whether improvements can be found through more sophisticated models.

We would like to evaluate the model on data it has not seen before, and

so we will split the data into a training set and a testing set.

This could be done by hand, but it is more convenient to use the

train_test_split utility function:

In[15]:fromsklearn.cross_validationimporttrain_test_splitXtrain,Xtest,ytrain,ytest=train_test_split(X_iris,y_iris,random_state=1)

With the data arranged, we can follow our recipe to predict the labels:

In[16]:fromsklearn.naive_bayesimportGaussianNB# 1. choose model classmodel=GaussianNB()# 2. instantiate modelmodel.fit(Xtrain,ytrain)# 3. fit model to datay_model=model.predict(Xtest)# 4. predict on new data

Finally, we can use the accuracy_score utility to see the fraction of

predicted labels that match their true value:

In[17]:fromsklearn.metricsimportaccuracy_scoreaccuracy_score(ytest,y_model)

Out[17]: 0.97368421052631582

With an accuracy topping 97%, we see that even this very naive classification algorithm is effective for this particular dataset!

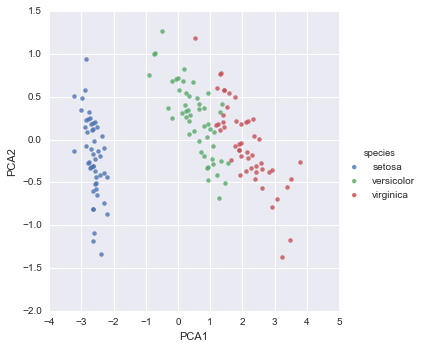

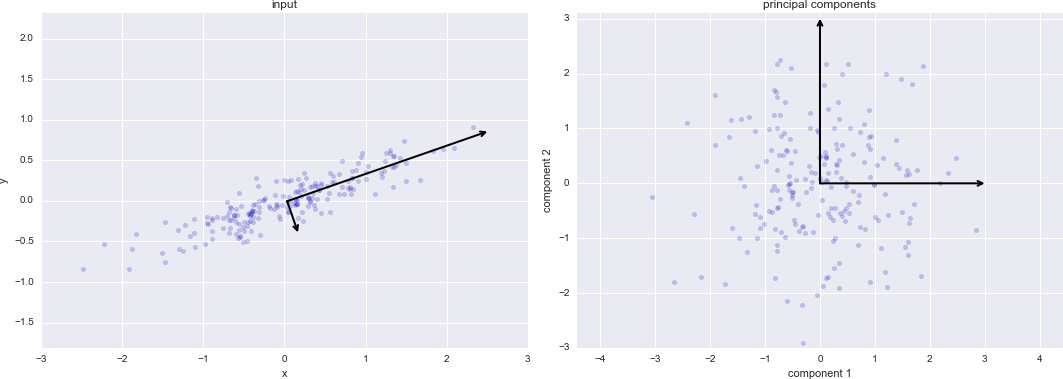

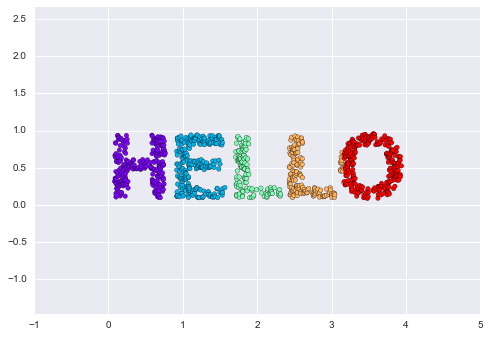

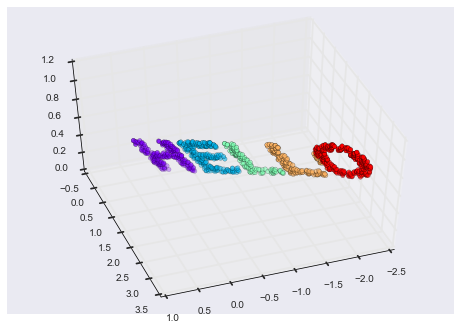

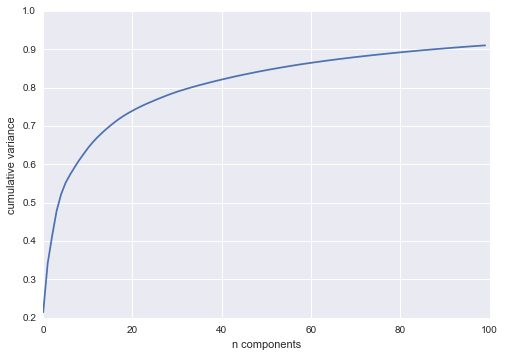

Unsupervised learning example: Iris dimensionality

As an example of an unsupervised learning problem, let’s take a look at reducing the dimensionality of the Iris data so as to more easily visualize it. Recall that the Iris data is four dimensional: there are four features recorded for each sample.

The task of dimensionality reduction is to ask whether there is a suitable lower-dimensional representation that retains the essential features of the data. Often dimensionality reduction is used as an aid to visualizing data; after all, it is much easier to plot data in two dimensions than in four dimensions or higher!

Here we will use principal component analysis (PCA; see “In Depth: Principal Component Analysis”), which is a fast linear dimensionality reduction technique. We will ask the model to return two components—that is, a two-dimensional representation of the data.

Following the sequence of steps outlined earlier, we have:

In[18]:fromsklearn.decompositionimportPCA# 1. Choose the model classmodel=PCA(n_components=2)# 2. Instantiate the model with hyperparametersmodel.fit(X_iris)# 3. Fit to data. Notice y is not specified!X_2D=model.transform(X_iris)# 4. Transform the data to two dimensions

Now let’s plot the results. A quick way to do this is to insert the

results into the original Iris DataFrame, and use Seaborn’s lmplot to

show the results (Figure 5-16):

In[19]:iris['PCA1']=X_2D[:,0]iris['PCA2']=X_2D[:,1]sns.lmplot("PCA1","PCA2",hue='species',data=iris,fit_reg=False);

We see that in the two-dimensional representation, the species are fairly well separated, even though the PCA algorithm had no knowledge of the species labels! This indicates to us that a relatively straightforward classification will probably be effective on the dataset, as we saw before.

Figure 5-16. The Iris data projected to two dimensions

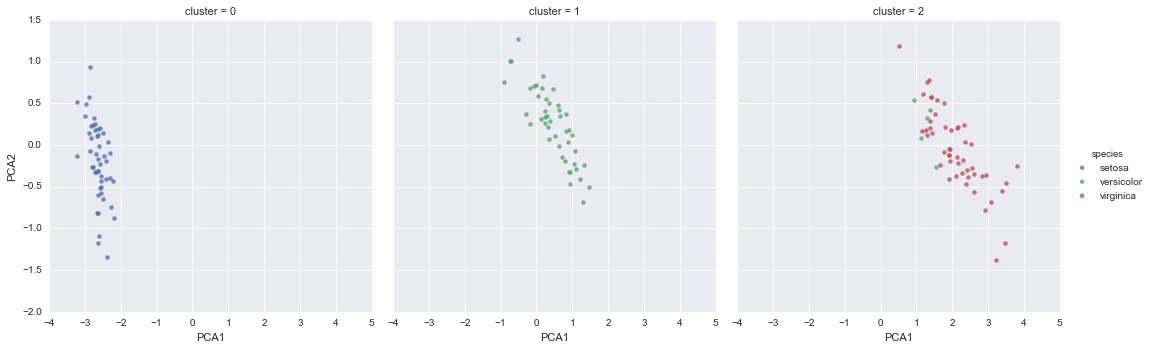

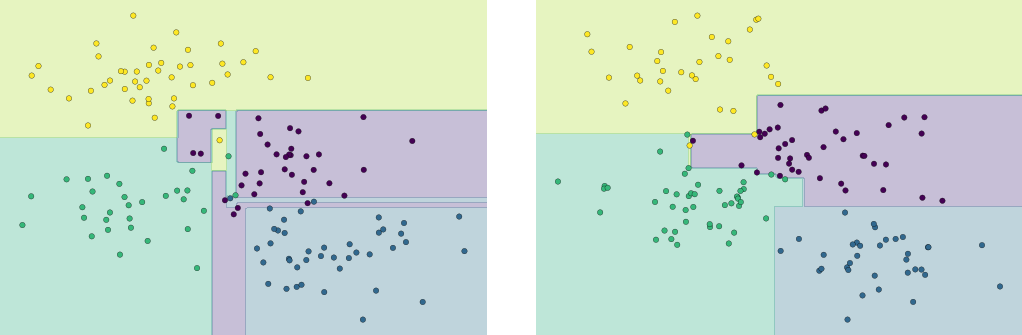

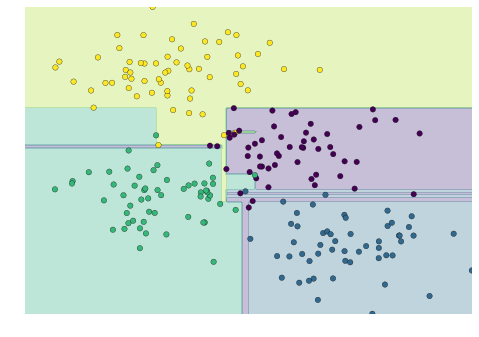

Unsupervised learning: Iris clustering

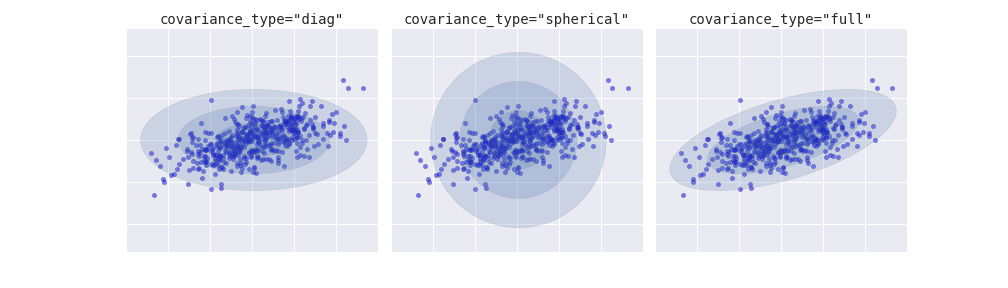

Let’s next look at applying clustering to the Iris data. A clustering algorithm attempts to find distinct groups of data without reference to any labels. Here we will use a powerful clustering method called a Gaussian mixture model (GMM), discussed in more detail in “In Depth: Gaussian Mixture Models”. A GMM attempts to model the data as a collection of Gaussian blobs.

We can fit the Gaussian mixture model as follows:

In[20]:fromsklearn.mixtureimportGMM# 1. Choose the model classmodel=GMM(n_components=3,covariance_type='full')# 2. Instantiate the model w/ hyperparametersmodel.fit(X_iris)# 3. Fit to data. Notice y is not specified!y_gmm=model.predict(X_iris)# 4. Determine cluster labels

As before, we will add the cluster label to the Iris DataFrame and use

Seaborn to plot the results (Figure 5-17):

In[21]:iris['cluster']=y_gmmsns.lmplot("PCA1","PCA2",data=iris,hue='species',col='cluster',fit_reg=False);

By splitting the data by cluster number, we see exactly how well the GMM algorithm has recovered the underlying label: the setosa species is separated perfectly within cluster 0, while there remains a small amount of mixing between versicolor and virginica. This means that even without an expert to tell us the species labels of the individual flowers, the measurements of these flowers are distinct enough that we could automatically identify the presence of these different groups of species with a simple clustering algorithm! This sort of algorithm might further give experts in the field clues as to the relationship between the samples they are observing.

Figure 5-17. k-means clusters within the Iris data

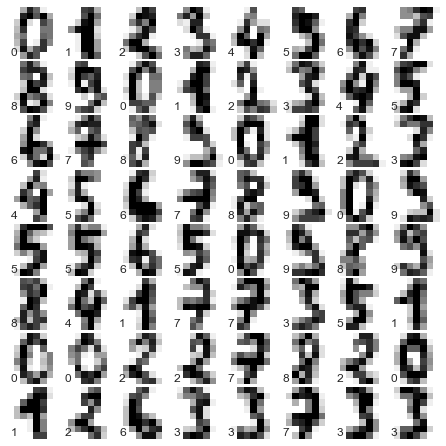

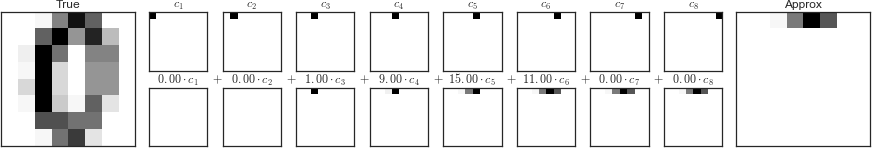

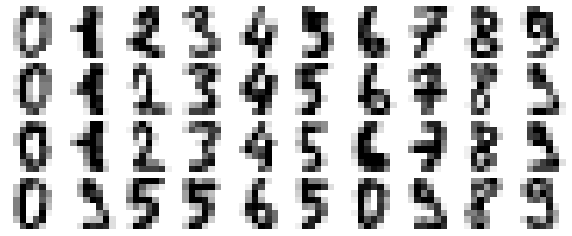

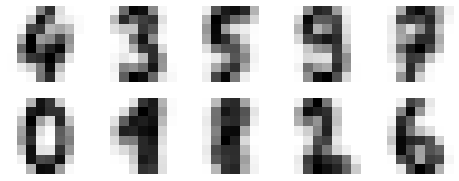

Application: Exploring Handwritten Digits

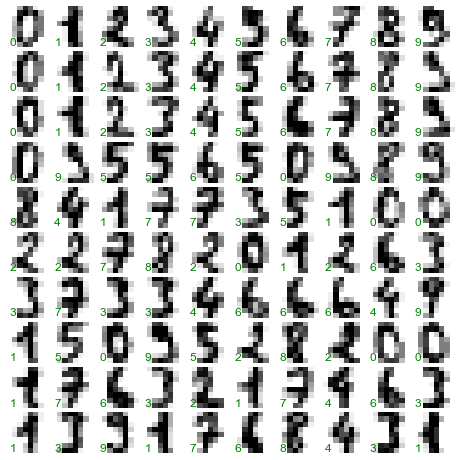

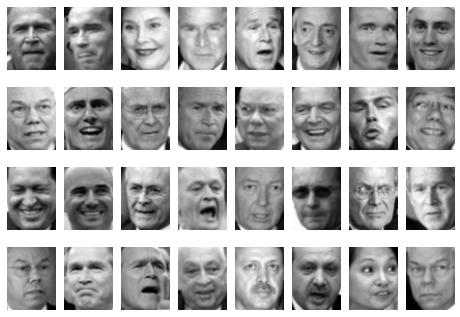

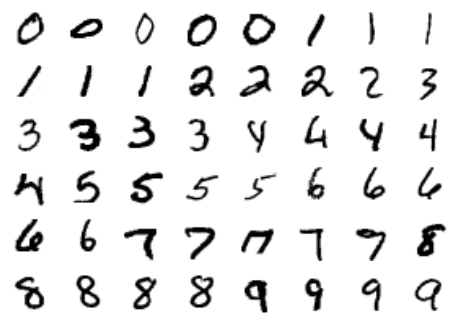

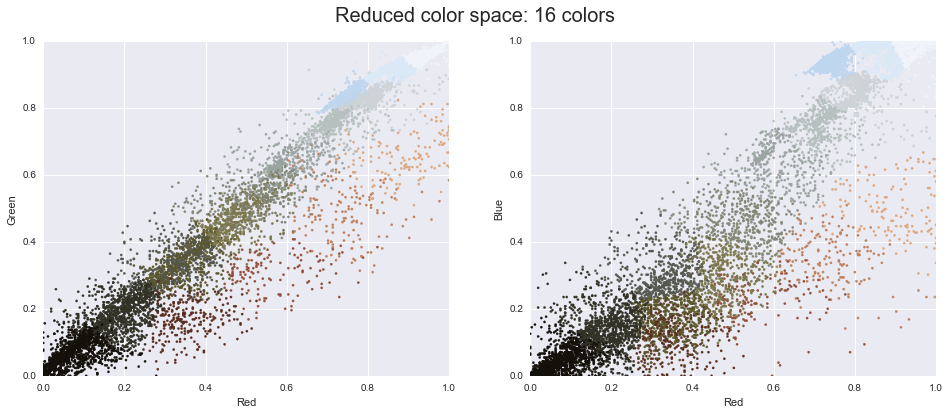

To demonstrate these principles on a more interesting problem, let’s consider one piece of the optical character recognition problem: the identification of handwritten digits. In the wild, this problem involves both locating and identifying characters in an image. Here we’ll take a shortcut and use Scikit-Learn’s set of preformatted digits, which is built into the library.

Loading and visualizing the digits data

We’ll use Scikit-Learn’s data access interface and take a look at this data:

In[22]:fromsklearn.datasetsimportload_digitsdigits=load_digits()digits.images.shape

Out[22]: (1797, 8, 8)

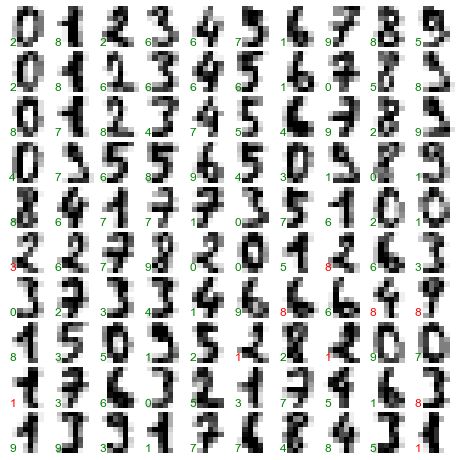

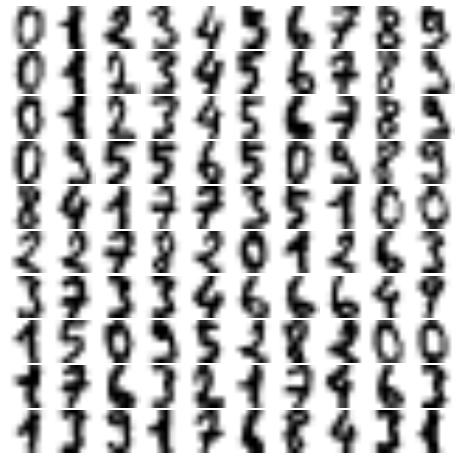

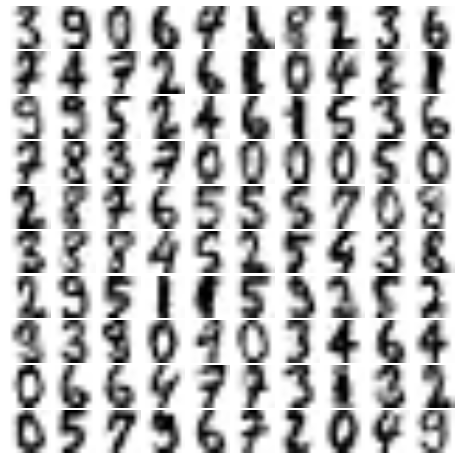

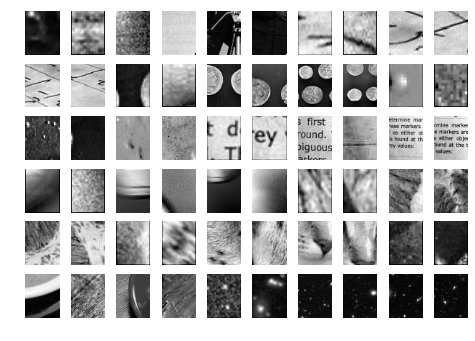

The images data is a three-dimensional array: 1,797 samples, each consisting of an 8×8 grid of pixels. Let’s visualize the first hundred of these (Figure 5-18):

In[23]:importmatplotlib.pyplotaspltfig,axes=plt.subplots(10,10,figsize=(8,8),subplot_kw={'xticks':[],'yticks':[]},gridspec_kw=dict(hspace=0.1,wspace=0.1))fori,axinenumerate(axes.flat):ax.imshow(digits.images[i],cmap='binary',interpolation='nearest')ax.text(0.05,0.05,str(digits.target[i]),transform=ax.transAxes,color='green')

Figure 5-18. The handwritten digits data; each sample is represented by one 8×8 grid of pixels

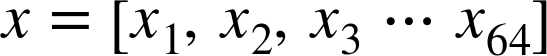

In order to work with this data within Scikit-Learn, we need a

two-dimensional, [n_samples, n_features] representation. We can

accomplish this by treating each pixel in the image as a feature—that

is, by flattening out the pixel arrays so that we have a length-64 array

of pixel values representing each digit. Additionally, we need the

target array, which gives the previously determined label for each

digit. These two quantities are built into the digits dataset under the

data and target attributes, respectively:

In[24]:X=digits.dataX.shape

Out[24]: (1797, 64)

In[25]:y=digits.targety.shape

Out[25]: (1797,)

We see here that there are 1,797 samples and 64 features.

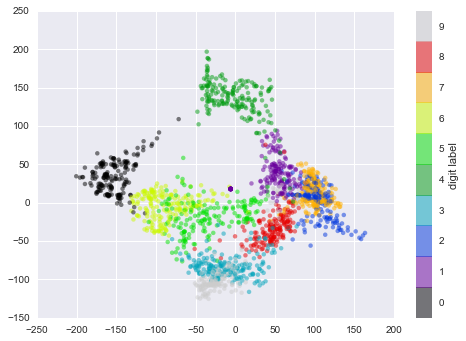

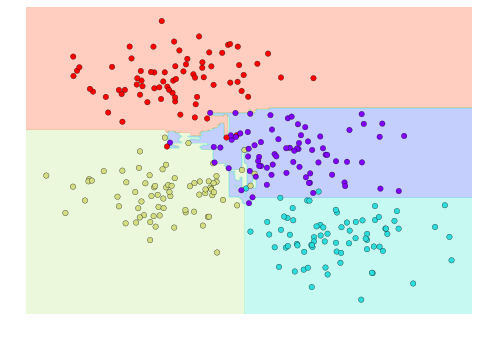

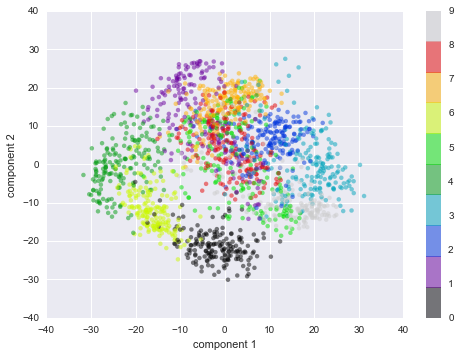

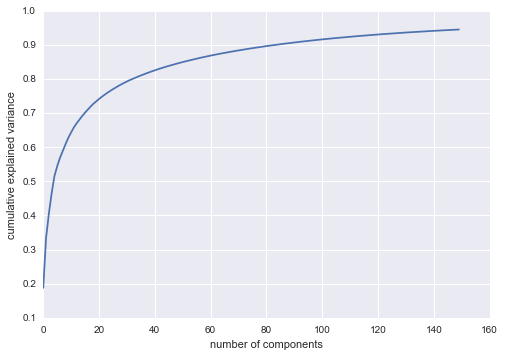

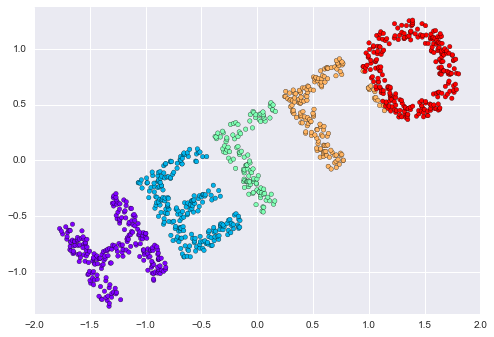

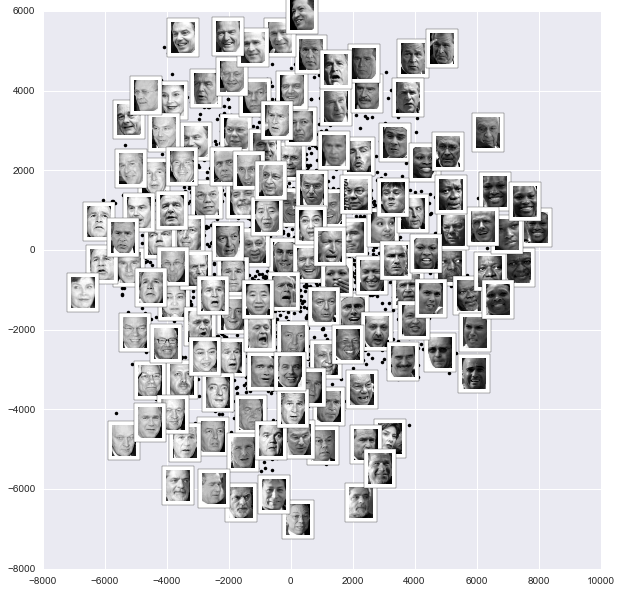

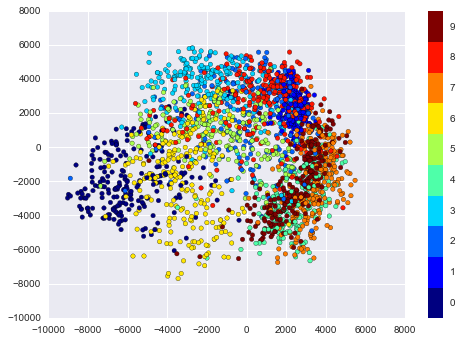

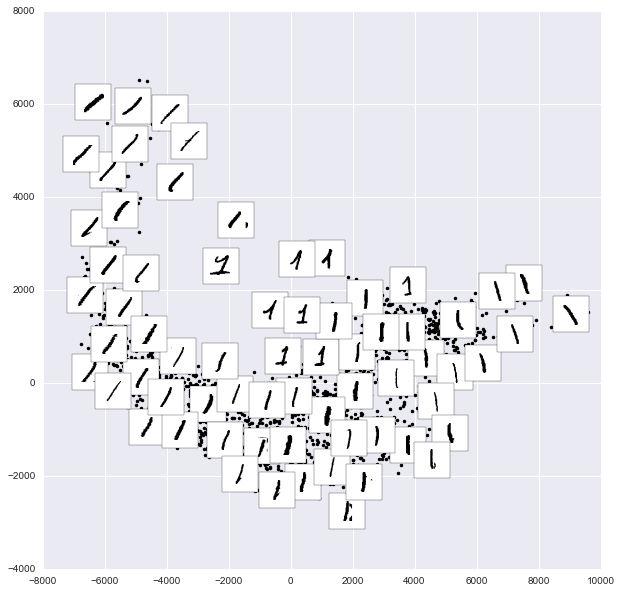

Unsupervised learning: Dimensionality reduction

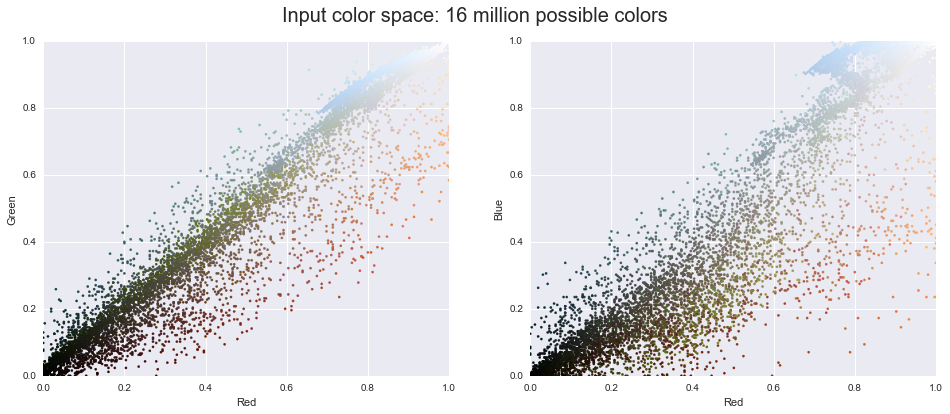

We’d like to visualize our points within the 64-dimensional parameter space, but it’s difficult to effectively visualize points in such a high-dimensional space. Instead we’ll reduce the dimensions to 2, using an unsupervised method. Here, we’ll make use of a manifold learning algorithm called Isomap (see “In-Depth: Manifold Learning”), and transform the data to two dimensions:

In[26]:fromsklearn.manifoldimportIsomapiso=Isomap(n_components=2)iso.fit(digits.data)data_projected=iso.transform(digits.data)data_projected.shape

Out[26]: (1797, 2)

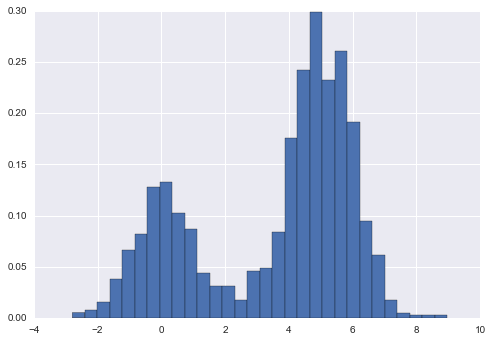

We see that the projected data is now two-dimensional. Let’s plot this data to see if we can learn anything from its structure (Figure 5-19):

In[27]:plt.scatter(data_projected[:,0],data_projected[:,1],c=digits.target,edgecolor='none',alpha=0.5,cmap=plt.cm.get_cmap('spectral',10))plt.colorbar(label='digit label',ticks=range(10))plt.clim(-0.5,9.5);

Figure 5-19. An Isomap embedding of the digits data

This plot gives us some good intuition into how well various numbers are separated in the larger 64-dimensional space. For example, zeros (in black) and ones (in purple) have very little overlap in parameter space. Intuitively, this makes sense: a zero is empty in the middle of the image, while a one will generally have ink in the middle. On the other hand, there seems to be a more or less continuous spectrum between ones and fours: we can understand this by realizing that some people draw ones with “hats” on them, which cause them to look similar to fours.

Overall, however, the different groups appear to be fairly well separated in the parameter space: this tells us that even a very straightforward supervised classification algorithm should perform suitably on this data. Let’s give it a try.

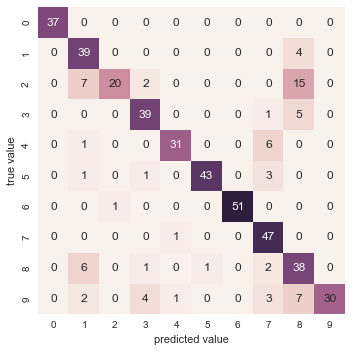

Classification on digits

Let’s apply a classification algorithm to the digits. As with the Iris data previously, we will split the data into a training and test set, and fit a Gaussian naive Bayes model:

In[28]:Xtrain,Xtest,ytrain,ytest=train_test_split(X,y,random_state=0)

In[29]:fromsklearn.naive_bayesimportGaussianNBmodel=GaussianNB()model.fit(Xtrain,ytrain)y_model=model.predict(Xtest)

Now that we have predicted our model, we can gauge its accuracy by comparing the true values of the test set to the predictions:

In[30]:fromsklearn.metricsimportaccuracy_scoreaccuracy_score(ytest,y_model)

Out[30]: 0.83333333333333337

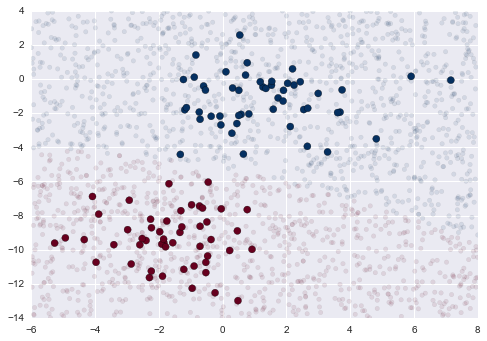

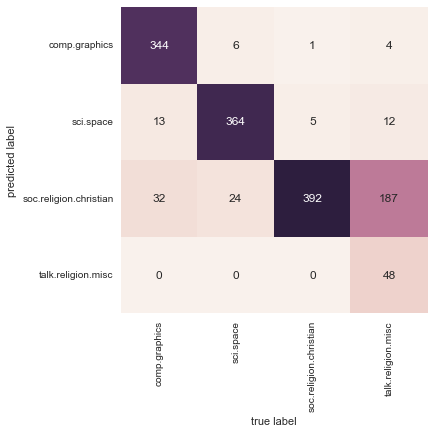

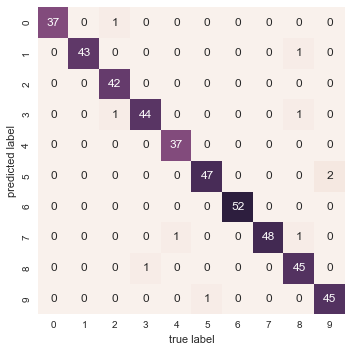

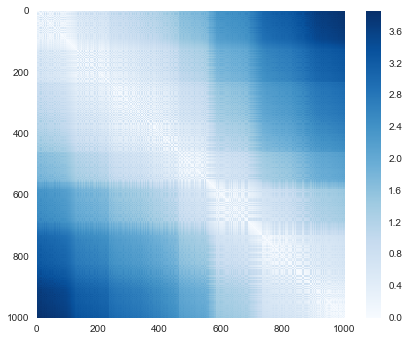

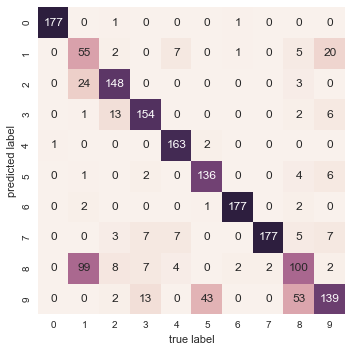

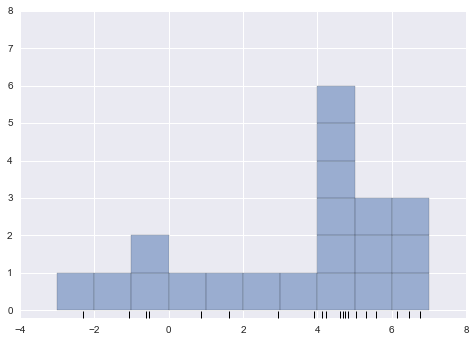

With even this extremely simple model, we find about 80% accuracy for classification of the digits! However, this single number doesn’t tell us where we’ve gone wrong—one nice way to do this is to use the confusion matrix, which we can compute with Scikit-Learn and plot with Seaborn (Figure 5-20):

In[31]:fromsklearn.metricsimportconfusion_matrixmat=confusion_matrix(ytest,y_model)sns.heatmap(mat,square=True,annot=True,cbar=False)plt.xlabel('predicted value')plt.ylabel('true value');

Figure 5-20. A confusion matrix showing the frequency of misclassifications by our classifier

This shows us where the mislabeled points tend to be: for example, a large number of twos here are misclassified as either ones or eights. Another way to gain intuition into the characteristics of the model is to plot the inputs again, with their predicted labels. We’ll use green for correct labels, and red for incorrect labels (Figure 5-21):

In[32]:fig,axes=plt.subplots(10,10,figsize=(8,8),subplot_kw={'xticks':[],'yticks':[]},gridspec_kw=dict(hspace=0.1,wspace=0.1))fori,axinenumerate(axes.flat):ax.imshow(digits.images[i],cmap='binary',interpolation='nearest')ax.text(0.05,0.05,str(y_model[i]),transform=ax.transAxes,color='green'if(ytest[i]==y_model[i])else'red')

Figure 5-21. Data showing correct (green) and incorrect (red) labels; for a color version of this plot, see the online appendix

Examining this subset of the data, we can gain insight regarding where the algorithm might not be performing optimally. To go beyond our 80% classification rate, we might move to a more sophisticated algorithm, such as support vector machines (see “In-Depth: Support Vector Machines”) or random forests (see “In-Depth: Decision Trees and Random Forests”), or another classification approach.

Summary

In this section we have covered the essential features of the Scikit-Learn data representation, and the estimator API. Regardless of the type of estimator, the same import/instantiate/fit/predict pattern holds. Armed with this information about the estimator API, you can explore the Scikit-Learn documentation and begin trying out various models on your data.

In the next section, we will explore perhaps the most important topic in machine learning: how to select and validate your model.

Hyperparameters and Model Validation

In the previous section, we saw the basic recipe for applying a supervised machine learning model:

-

Choose a class of model

-

Choose model hyperparameters

-

Fit the model to the training data

-

Use the model to predict labels for new data

The first two pieces of this—the choice of model and choice of hyperparameters—are perhaps the most important part of using these tools and techniques effectively. In order to make an informed choice, we need a way to validate that our model and our hyperparameters are a good fit to the data. While this may sound simple, there are some pitfalls that you must avoid to do this effectively.

Thinking About Model Validation

In principle, model validation is very simple: after choosing a model and its hyperparameters, we can estimate how effective it is by applying it to some of the training data and comparing the prediction to the known value.

The following sections first show a naive approach to model validation and why it fails, before exploring the use of holdout sets and cross-validation for more robust model evaluation.

Model validation the wrong way

Let’s demonstrate the naive approach to validation using the Iris data, which we saw in the previous section. We will start by loading the data:

In[1]:fromsklearn.datasetsimportload_irisiris=load_iris()X=iris.datay=iris.target

Next we choose a model and hyperparameters. Here we’ll use a k-neighbors

classifier with n_neighbors=1. This is a very simple and intuitive

model that says “the label of an unknown point is the same as the label

of its closest training point”:

In[2]:fromsklearn.neighborsimportKNeighborsClassifiermodel=KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=1)

Then we train the model, and use it to predict labels for data we already know:

In[3]:model.fit(X,y)y_model=model.predict(X)

Finally, we compute the fraction of correctly labeled points:

In[4]:fromsklearn.metricsimportaccuracy_scoreaccuracy_score(y,y_model)

Out[4]: 1.0

We see an accuracy score of 1.0, which indicates that 100% of points were correctly labeled by our model! But is this truly measuring the expected accuracy? Have we really come upon a model that we expect to be correct 100% of the time?

As you may have gathered, the answer is no. In fact, this approach contains a fundamental flaw: it trains and evaluates the model on the same data. Furthermore, the nearest neighbor model is an instance-based estimator that simply stores the training data, and predicts labels by comparing new data to these stored points; except in contrived cases, it will get 100% accuracy every time!

Model validation the right way: Holdout sets

So what can be done? We can get a better sense of a model’s performance using what’s known as a holdout set; that is, we hold back some

subset of the data from the training of the model, and then use this

holdout set to check the model performance. We can do this splitting using the train_test_split utility in Scikit-Learn:

In[5]:fromsklearn.cross_validationimporttrain_test_split# split the data with 50% in each setX1,X2,y1,y2=train_test_split(X,y,random_state=0,train_size=0.5)# fit the model on one set of datamodel.fit(X1,y1)# evaluate the model on the second set of datay2_model=model.predict(X2)accuracy_score(y2,y2_model)

Out[5]: 0.90666666666666662

We see here a more reasonable result: the nearest-neighbor classifier is about 90% accurate on this holdout set. The holdout set is similar to unknown data, because the model has not “seen” it before.

Model validation via cross-validation

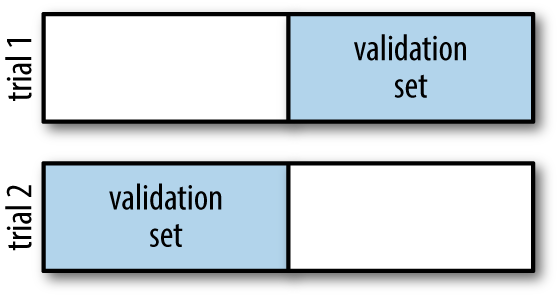

One disadvantage of using a holdout set for model validation is that we have lost a portion of our data to the model training. In the previous case, half the dataset does not contribute to the training of the model! This is not optimal, and can cause problems—especially if the initial set of training data is small.

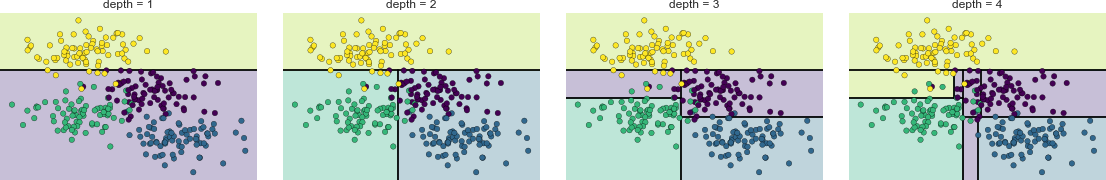

One way to address this is to use cross-validation—that is, to do a sequence of fits where each subset of the data is used both as a training set and as a validation set. Visually, it might look something like Figure 5-22.

Figure 5-22. Visualization of two-fold cross-validation

Here we do two validation trials, alternately using each half of the data as a holdout set. Using the split data from before, we could implement it like this:

In[6]:y2_model=model.fit(X1,y1).predict(X2)y1_model=model.fit(X2,y2).predict(X1)accuracy_score(y1,y1_model),accuracy_score(y2,y2_model)

Out[6]: (0.95999999999999996, 0.90666666666666662)

What comes out are two accuracy scores, which we could combine (by, say, taking the mean) to get a better measure of the global model performance. This particular form of cross-validation is a two-fold cross-validation—one in which we have split the data into two sets and used each in turn as a validation set.

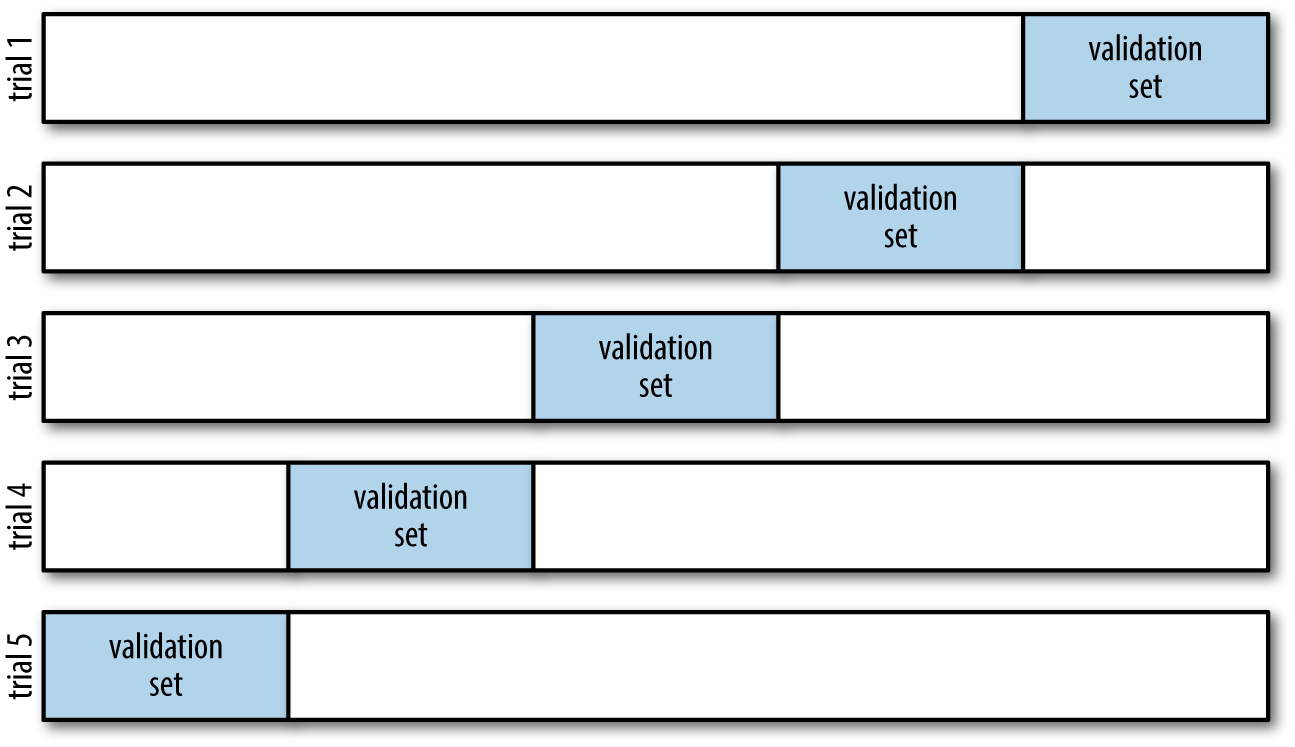

We could expand on this idea to use even more trials, and more folds in the data—for example, Figure 5-23 is a visual depiction of five-fold cross-validation.

Figure 5-23. Visualization of five-fold cross-validation

Here we split the data into five groups, and use each of them in turn to

evaluate the model fit on the other 4/5 of the data. This would be

rather tedious to do by hand, and so we can use Scikit-Learn’s

cross_val_score convenience routine to do it succinctly:

In[7]:fromsklearn.cross_validationimportcross_val_scorecross_val_score(model,X,y,cv=5)

Out[7]: array([ 0.96666667, 0.96666667, 0.93333333, 0.93333333, 1. ])

Repeating the validation across different subsets of the data gives us an even better idea of the performance of the algorithm.

Scikit-Learn implements a number of cross-validation schemes that

are useful in particular situations; these are implemented via iterators

in the cross_validation module. For example, we might wish to go to

the extreme case in which our number of folds is equal to the number of

data points; that is, we train on all points but one in each trial. This

type of cross-validation is known as leave-one-out cross-validation,

and can be used as follows:

In[8]:fromsklearn.cross_validationimportLeaveOneOutscores=cross_val_score(model,X,y,cv=LeaveOneOut(len(X)))scores

Out[8]: array([ 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1.,

1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1.,

1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1.,

1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1.,

1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1.,

1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 0., 1., 0., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1.,

1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 0., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1.,

1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1.,

1., 1., 0., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1.,

1., 1., 0., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1.,

1., 1., 1., 0., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1.,

1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1., 1.])

Because we have 150 samples, the leave-one-out cross-validation yields scores for 150 trials, and the score indicates either successful (1.0) or unsuccessful (0.0) prediction. Taking the mean of these gives an estimate of the error rate:

In[9]:scores.mean()

Out[9]: 0.95999999999999996

Other cross-validation schemes can be used similarly. For a description

of what is available in Scikit-Learn, use IPython to explore the

sklearn.cross_validation submodule, or take a look at Scikit-Learn’s

online

cross-validation documentation.

Selecting the Best Model

Now that we’ve seen the basics of validation and cross-validation, we will go into a little more depth regarding model selection and selection of hyperparameters. These issues are some of the most important aspects of the practice of machine learning, and I find that this information is often glossed over in introductory machine learning tutorials.

Of core importance is the following question: if our estimator is underperforming, how should we move forward? There are several possible answers:

-

Use a more complicated/more flexible model

-

Use a less complicated/less flexible model

-

Gather more training samples

-

Gather more data to add features to each sample

The answer to this question is often counterintuitive. In particular, sometimes using a more complicated model will give worse results, and adding more training samples may not improve your results! The ability to determine what steps will improve your model is what separates the successful machine learning practitioners from the unsuccessful.

The bias–variance trade-off

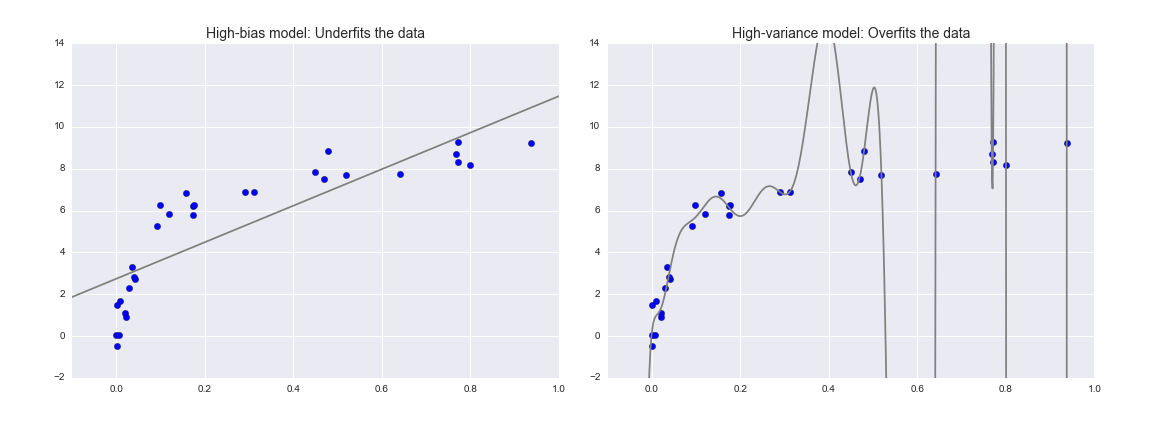

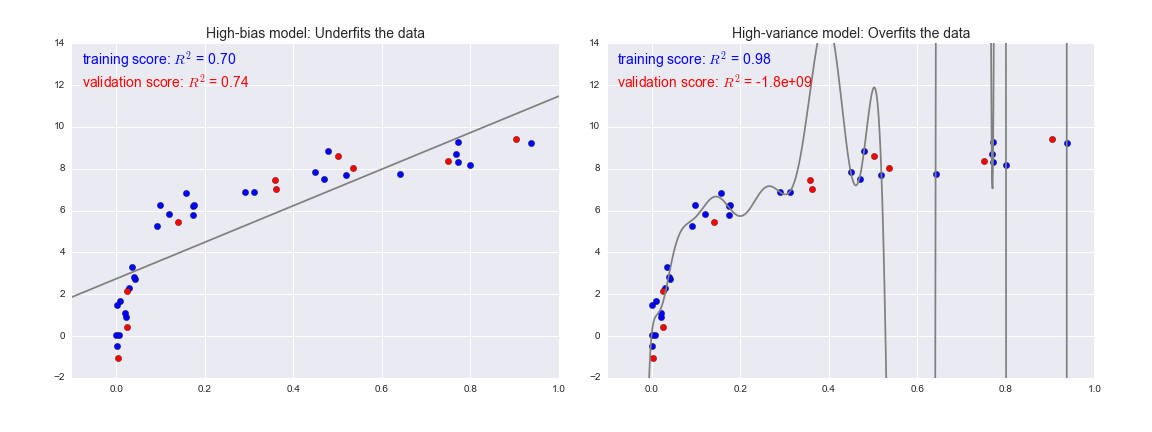

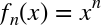

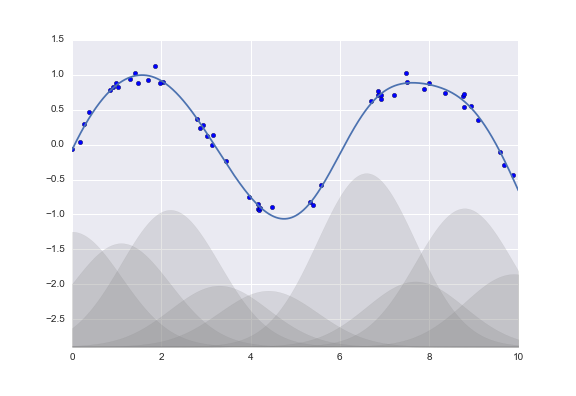

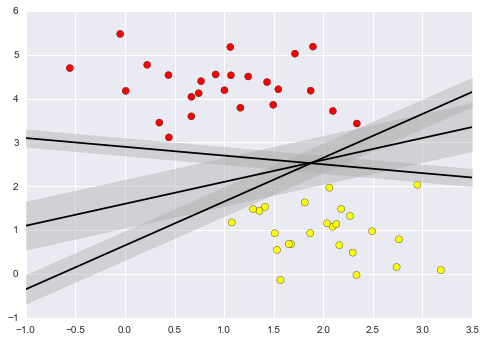

Fundamentally, the question of “the best model” is about finding a sweet spot in the trade-off between bias and variance. Consider Figure 5-24, which presents two regression fits to the same dataset.

Figure 5-24. A high-bias and high-variance regression model

It is clear that neither of these models is a particularly good fit to the data, but they fail in different ways.

The model on the left attempts to find a straight-line fit through the data. Because the data are intrinsically more complicated than a straight line, the straight-line model will never be able to describe this dataset well. Such a model is said to underfit the data; that is, it does not have enough model flexibility to suitably account for all the features in the data. Another way of saying this is that the model has high bias.

The model on the right attempts to fit a high-order polynomial through the data. Here the model fit has enough flexibility to nearly perfectly account for the fine features in the data, but even though it very accurately describes the training data, its precise form seems to be more reflective of the particular noise properties of the data rather than the intrinsic properties of whatever process generated that data. Such a model is said to overfit the data; that is, it has so much model flexibility that the model ends up accounting for random errors as well as the underlying data distribution. Another way of saying this is that the model has high variance.

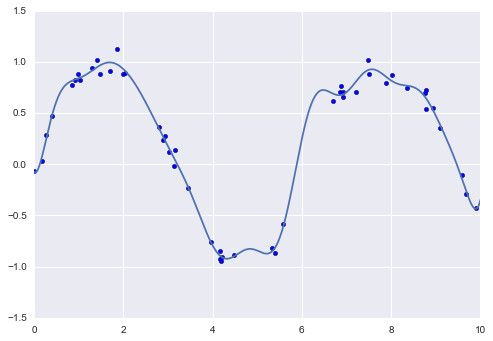

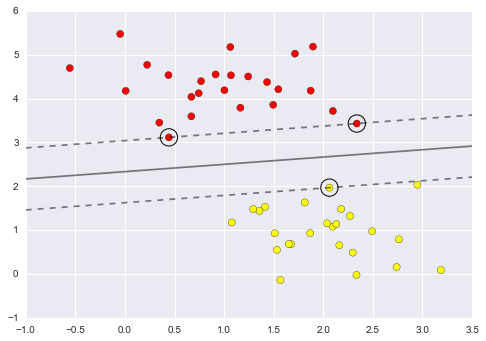

To look at this in another light, consider what happens if we use these two models to predict the y-value for some new data. In diagrams in Figure 5-25, the red/lighter points indicate data that is omitted from the training set.

Figure 5-25. Training and validation scores in high-bias and high-variance models

The score here is the  score, or

coefficient

of determination, which measures how well a model performs relative to

a simple mean of the target values.

score, or

coefficient

of determination, which measures how well a model performs relative to

a simple mean of the target values.  indicates a

perfect match,

indicates a

perfect match,  indicates the model does no better

than simply taking the mean of the data, and negative values mean even

worse models. From the scores associated with these two models, we can

make an observation that holds more generally:

indicates the model does no better

than simply taking the mean of the data, and negative values mean even

worse models. From the scores associated with these two models, we can

make an observation that holds more generally:

-

For high-bias models, the performance of the model on the validation set is similar to the performance on the training set.

-

For high-variance models, the performance of the model on the validation set is far worse than the performance on the training set.

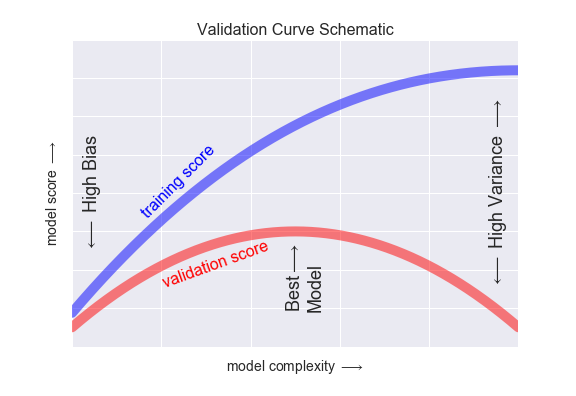

If we imagine that we have some ability to tune the model complexity, we would expect the training score and validation score to behave as illustrated in Figure 5-26.

The diagram shown in Figure 5-26 is often called a validation curve, and we see the following essential features:

-

The training score is everywhere higher than the validation score. This is generally the case: the model will be a better fit to data it has seen than to data it has not seen.

-

For very low model complexity (a high-bias model), the training data is underfit, which means that the model is a poor predictor both for the training data and for any previously unseen data.

-

For very high model complexity (a high-variance model), the training data is overfit, which means that the model predicts the training data very well, but fails for any previously unseen data.

-

For some intermediate value, the validation curve has a maximum. This level of complexity indicates a suitable trade-off between bias and variance.

Figure 5-26. A schematic of the relationship between model complexity, training score, and validation score

The means of tuning the model complexity varies from model to model; when we discuss individual models in depth in later sections, we will see how each model allows for such tuning.

Validation curves in Scikit-Learn

Let’s look at an example of using cross-validation to compute the

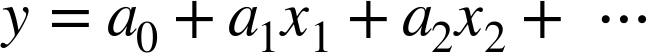

validation curve for a class of models. Here we will use a polynomial regression model: this is a generalized linear model in which the

degree of the polynomial is a tunable parameter. For example, a degree-1

polynomial fits a straight line to the data; for model parameters

and

and  :

:

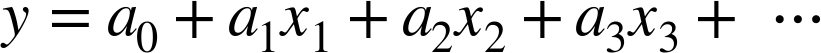

A degree-3 polynomial fits a cubic curve to the data; for model

parameters  :

:

We can generalize this to any number of polynomial features. In Scikit-Learn, we can implement this with a simple linear regression combined with the polynomial preprocessor. We will use a pipeline to string these operations together (we will discuss polynomial features and pipelines more fully in “Feature Engineering”):

In[10]:fromsklearn.preprocessingimportPolynomialFeaturesfromsklearn.linear_modelimportLinearRegressionfromsklearn.pipelineimportmake_pipelinedefPolynomialRegression(degree=2,**kwargs):returnmake_pipeline(PolynomialFeatures(degree),LinearRegression(**kwargs))

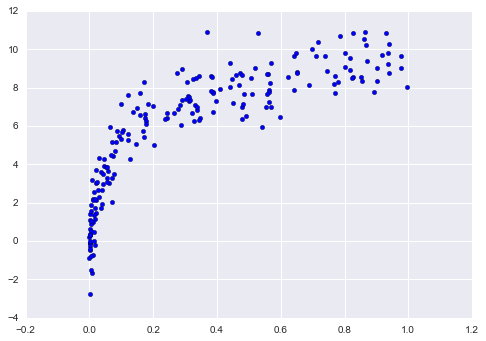

Now let’s create some data to which we will fit our model:

In[11]:importnumpyasnpdefmake_data(N,err=1.0,rseed=1):# randomly sample the datarng=np.random.RandomState(rseed)X=rng.rand(N,1)**2y=10-1./(X.ravel()+0.1)iferr>0:y+=err*rng.randn(N)returnX,yX,y=make_data(40)

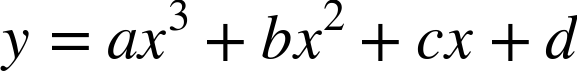

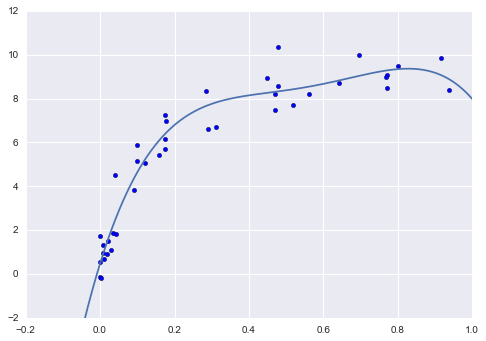

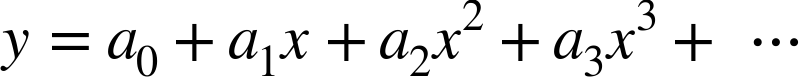

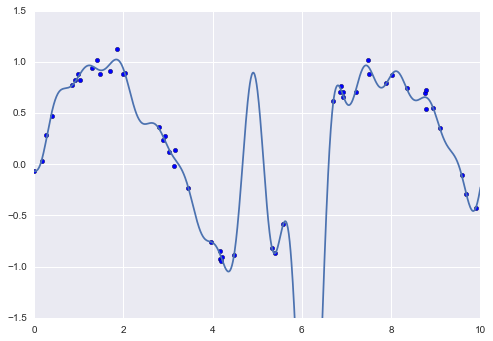

We can now visualize our data, along with polynomial fits of several degrees (Figure 5-27):

In[12]:%matplotlibinlineimportmatplotlib.pyplotaspltimportseaborn;seaborn.set()# plot formattingX_test=np.linspace(-0.1,1.1,500)[:,None]plt.scatter(X.ravel(),y,color='black')axis=plt.axis()fordegreein[1,3,5]:y_test=PolynomialRegression(degree).fit(X,y).predict(X_test)plt.plot(X_test.ravel(),y_test,label='degree={0}'.format(degree))plt.xlim(-0.1,1.0)plt.ylim(-2,12)plt.legend(loc='best');

The knob controlling model complexity in this case is the degree of the polynomial, which can be any non-negative integer. A useful question to answer is this: what degree of polynomial provides a suitable trade-off between bias (underfitting) and variance (overfitting)?

Figure 5-27. Three different polynomial models fit to a dataset

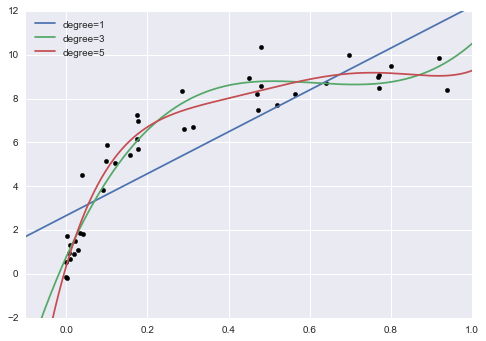

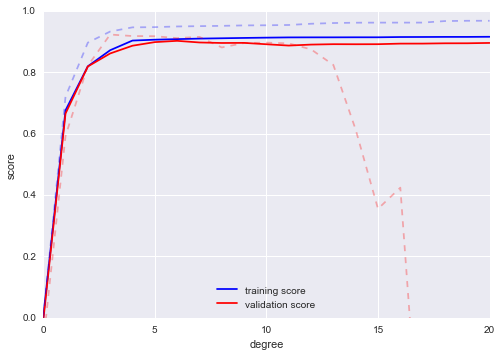

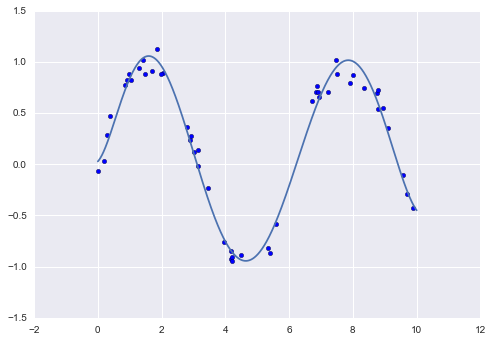

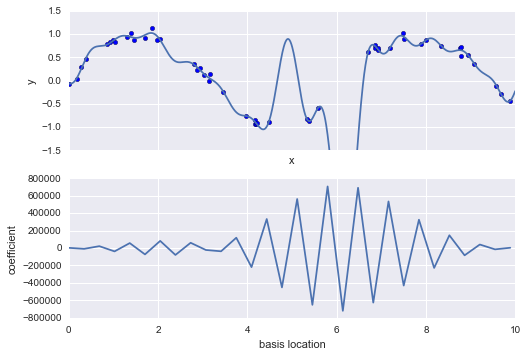

We can make progress in this by visualizing the validation curve for

this particular data and model; we can do this straightforwardly using

the validation_curve convenience routine provided by Scikit-Learn.

Given a model, data, parameter name, and a range to explore, this

function will automatically compute both the training score and

validation score across the range (Figure 5-28):

In[13]:fromsklearn.learning_curveimportvalidation_curvedegree=np.arange(0,21)train_score,val_score=validation_curve(PolynomialRegression(),X,y,'polynomialfeatures__degree',degree,cv=7)plt.plot(degree,np.median(train_score,1),color='blue',label='training score')plt.plot(degree,np.median(val_score,1),color='red',label='validation score')plt.legend(loc='best')plt.ylim(0,1)plt.xlabel('degree')plt.ylabel('score');

This shows precisely the qualitative behavior we expect: the training score is everywhere higher than the validation score; the training score is monotonically improving with increased model complexity; and the validation score reaches a maximum before dropping off as the model becomes overfit.

Figure 5-28. The validation curves for the data in Figure 5-27 (cf. Figure 5-26)

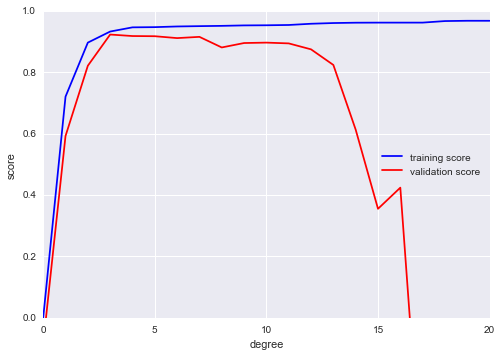

From the validation curve, we can read off that the optimal trade-off between bias and variance is found for a third-order polynomial; we can compute and display this fit over the original data as follows (Figure 5-29):

In[14]:plt.scatter(X.ravel(),y)lim=plt.axis()y_test=PolynomialRegression(3).fit(X,y).predict(X_test)plt.plot(X_test.ravel(),y_test);plt.axis(lim);

Figure 5-29. The cross-validated optimal model for the data in Figure 5-27

Notice that finding this optimal model did not actually require us to compute the training score, but examining the relationship between the training score and validation score can give us useful insight into the performance of the model.

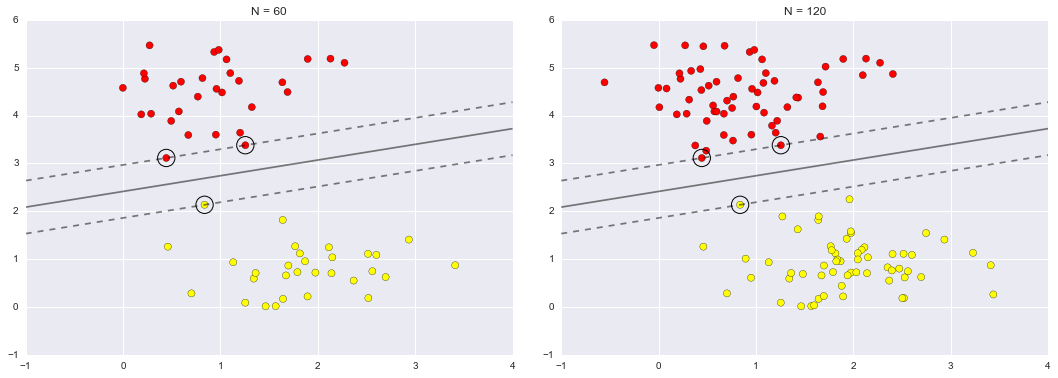

Learning Curves

One important aspect of model complexity is that the optimal model will generally depend on the size of your training data. For example, let’s generate a new dataset with a factor of five more points (Figure 5-30):

In[15]:X2,y2=make_data(200)plt.scatter(X2.ravel(),y2);

Figure 5-30. Data to demonstrate learning curves

We will duplicate the preceding code to plot the validation curve for this larger dataset; for reference let’s over-plot the previous results as well (Figure 5-31):

In[16]:degree=np.arange(21)train_score2,val_score2=validation_curve(PolynomialRegression(),X2,y2,'polynomialfeatures__degree',degree,cv=7)plt.plot(degree,np.median(train_score2,1),color='blue',label='training score')plt.plot(degree,np.median(val_score2,1),color='red',label='validation score')plt.plot(degree,np.median(train_score,1),color='blue',alpha=0.3,linestyle='dashed')plt.plot(degree,np.median(val_score,1),color='red',alpha=0.3,linestyle='dashed')plt.legend(loc='lower center')plt.ylim(0,1)plt.xlabel('degree')plt.ylabel('score');

Figure 5-31. Learning curves for the polynomial model fit to data in Figure 5-30

The solid lines show the new results, while the fainter dashed lines show the results of the previous smaller dataset. It is clear from the validation curve that the larger dataset can support a much more complicated model: the peak here is probably around a degree of 6, but even a degree-20 model is not seriously overfitting the data—the validation and training scores remain very close.

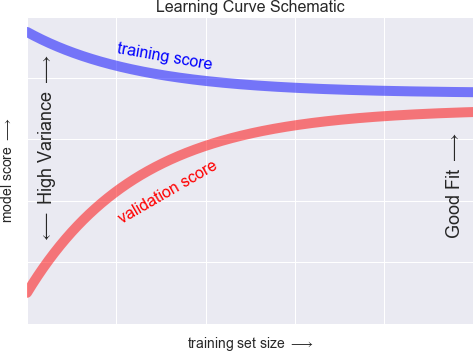

Thus we see that the behavior of the validation curve has not one, but two, important inputs: the model complexity and the number of training points. It is often useful to explore the behavior of the model as a function of the number of training points, which we can do by using increasingly larger subsets of the data to fit our model. A plot of the training/validation score with respect to the size of the training set is known as a learning curve.

The general behavior we would expect from a learning curve is this:

-

A model of a given complexity will overfit a small dataset: this means the training score will be relatively high, while the validation score will be relatively low.

-

A model of a given complexity will underfit a large dataset: this means that the training score will decrease, but the validation score will increase.

-

A model will never, except by chance, give a better score to the validation set than the training set: this means the curves should keep getting closer together but never cross.

With these features in mind, we would expect a learning curve to look qualitatively like that shown in Figure 5-32.

Figure 5-32. Schematic showing the typical interpretation of learning curves

The notable feature of the learning curve is the convergence to a particular score as the number of training samples grows. In particular, once you have enough points that a particular model has converged, adding more training data will not help you! The only way to increase model performance in this case is to use another (often more complex) model.

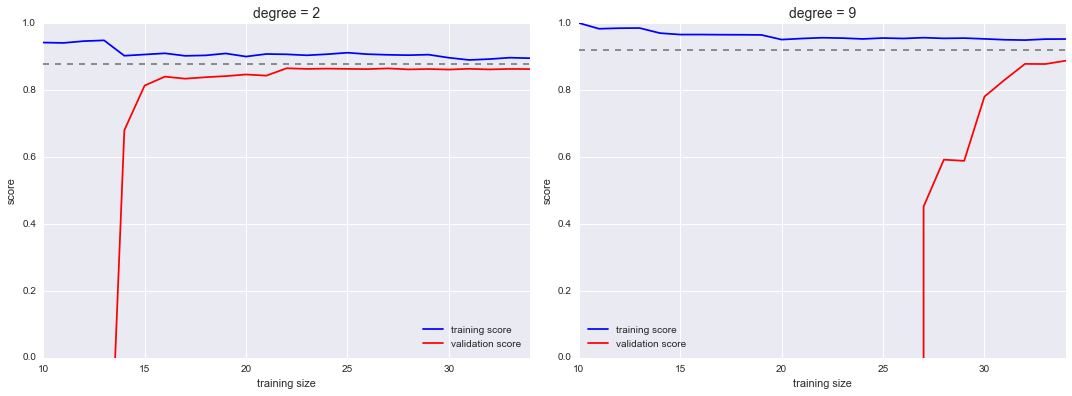

Learning curves in Scikit-Learn

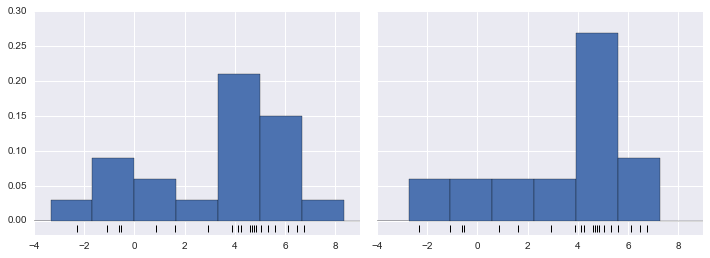

Scikit-Learn offers a convenient utility for computing such learning curves from your models; here we will compute a learning curve for our original dataset with a second-order polynomial model and a ninth-order polynomial (Figure 5-33):

In[17]:fromsklearn.learning_curveimportlearning_curvefig,ax=plt.subplots(1,2,figsize=(16,6))fig.subplots_adjust(left=0.0625,right=0.95,wspace=0.1)fori,degreeinenumerate([2,9]):N,train_lc,val_lc=learning_curve(PolynomialRegression(degree),X,y,cv=7,train_sizes=np.linspace(0.3,1,25))ax[i].plot(N,np.mean(train_lc,1),color='blue',label='training score')ax[i].plot(N,np.mean(val_lc,1),color='red',label='validation score')ax[i].hlines(np.mean([train_lc[-1],val_lc[-1]]),N[0],N[-1],color='gray',linestyle='dashed')ax[i].set_ylim(0,1)ax[i].set_xlim(N[0],N[-1])ax[i].set_xlabel('training size')ax[i].set_ylabel('score')ax[i].set_title('degree = {0}'.format(degree),size=14)ax[i].legend(loc='best')

Figure 5-33. Learning curves for a low-complexity model (left) and a high-complexity model (right)

This is a valuable diagnostic, because it gives us a visual depiction of how our model responds to increasing training data. In particular, when your learning curve has already converged (i.e., when the training and validation curves are already close to each other), adding more training data will not significantly improve the fit! This situation is seen in the left panel, with the learning curve for the degree-2 model.

The only way to increase the converged score is to use a different (usually more complicated) model. We see this in the right panel: by moving to a much more complicated model, we increase the score of convergence (indicated by the dashed line), but at the expense of higher model variance (indicated by the difference between the training and validation scores). If we were to add even more data points, the learning curve for the more complicated model would eventually converge.

Plotting a learning curve for your particular choice of model and dataset can help you to make this type of decision about how to move forward in improving your analysis.

Validation in Practice: Grid Search

The preceding discussion is meant to give you some intuition into the trade-off between bias and variance, and its dependence on model complexity and training set size. In practice, models generally have more than one knob to turn, and thus plots of validation and learning curves change from lines to multidimensional surfaces. In these cases, such visualizations are difficult and we would rather simply find the particular model that maximizes the validation score.

Scikit-Learn provides automated tools to do this in the grid_search

module. Here is an example of using grid search to find the optimal

polynomial model. We will explore a three-dimensional grid of model

features—namely, the polynomial degree, the flag telling us whether to

fit the intercept, and the flag telling us whether to normalize the

problem. We can set this up using Scikit-Learn’s GridSearchCV

meta-estimator:

In[18]:fromsklearn.grid_searchimportGridSearchCVparam_grid={'polynomialfeatures__degree':np.arange(21),'linearregression__fit_intercept':[True,False],'linearregression__normalize':[True,False]}grid=GridSearchCV(PolynomialRegression(),param_grid,cv=7)

Notice that like a normal estimator, this has not yet been applied to

any data. Calling the fit() method will fit the model at each grid

point, keeping track of the scores along the way:

In[19]:grid.fit(X,y);

Now that this is fit, we can ask for the best parameters as follows:

In[20]:grid.best_params_

Out[20]: {'linearregression__fit_intercept': False,

'linearregression__normalize': True,

'polynomialfeatures__degree': 4}

Finally, if we wish, we can use the best model and show the fit to our data using code from before (Figure 5-34):

In[21]:model=grid.best_estimator_plt.scatter(X.ravel(),y)lim=plt.axis()y_test=model.fit(X,y).predict(X_test)plt.plot(X_test.ravel(),y_test,hold=True);plt.axis(lim);

The grid search provides many more options, including the ability to specify a custom scoring function, to parallelize the computations, to do randomized searches, and more. For information, see the examples in “In-Depth: Kernel Density Estimation” and “Application: A Face Detection Pipeline”, or refer to Scikit-Learn’s grid search documentation.

Figure 5-34. The best-fit model determined via an automatic grid-search

Summary

In this section, we have begun to explore the concept of model validation and hyperparameter optimization, focusing on intuitive aspects of the bias–variance trade-off and how it comes into play when fitting models to data. In particular, we found that the use of a validation set or cross-validation approach is vital when tuning parameters in order to avoid overfitting for more complex/flexible models.

In later sections, we will discuss the details of particularly useful models, and throughout will talk about what tuning is available for these models and how these free parameters affect model complexity. Keep the lessons of this section in mind as you read on and learn about these machine learning approaches!

Feature Engineering

The previous sections outline the fundamental ideas of machine learning,

but all of the examples assume that you have numerical data in a tidy,

[n_samples, n_features] format. In the real world, data rarely comes

in such a form. With this in mind, one of the more important steps in

using machine learning in practice is feature engineering—that is,

taking whatever information you have about your problem and turning it

into numbers that you can use to build your feature matrix.

In this section, we will cover a few common examples of feature engineering tasks: features for representing categorical data, features for representing text, and features for representing images. Additionally, we will discuss derived features for increasing model complexity and imputation of missing data. Often this process is known as vectorization, as it involves converting arbitrary data into well-behaved vectors.

Categorical Features

One common type of non-numerical data is categorical data. For example, imagine you are exploring some data on housing prices, and along with numerical features like “price” and “rooms,” you also have “neighborhood” information. For example, your data might look something like this:

In[1]:data=[{'price':850000,'rooms':4,'neighborhood':'Queen Anne'},{'price':700000,'rooms':3,'neighborhood':'Fremont'},{'price':650000,'rooms':3,'neighborhood':'Wallingford'},{'price':600000,'rooms':2,'neighborhood':'Fremont'}]

You might be tempted to encode this data with a straightforward numerical mapping:

In[2]:{'Queen Anne':1,'Fremont':2,'Wallingford':3};

It turns out that this is not generally a useful approach in Scikit-Learn: the package’s models make the fundamental assumption that numerical features reflect algebraic quantities. Thus such a mapping would imply, for example, that Queen Anne < Fremont < Wallingford, or even that Wallingford - Queen Anne = Fremont, which (niche demographic jokes aside) does not make much sense.

In this case, one proven technique is to use one-hot encoding, which

effectively creates extra columns indicating the presence or absence of

a category with a value of 1 or 0, respectively. When your data comes as a

list of dictionaries, Scikit-Learn’s DictVectorizer will do this for

you:

In[3]:fromsklearn.feature_extractionimportDictVectorizervec=DictVectorizer(sparse=False,dtype=int)vec.fit_transform(data)

Out[3]: array([[ 0, 1, 0, 850000, 4],

[ 1, 0, 0, 700000, 3],

[ 0, 0, 1, 650000, 3],

[ 1, 0, 0, 600000, 2]], dtype=int64)

Notice that the neighborhood column has been expanded into three separate columns, representing the three neighborhood labels, and that each row has a 1 in the column associated with its neighborhood. With these categorical features thus encoded, you can proceed as normal with fitting a Scikit-Learn model.

To see the meaning of each column, you can inspect the feature names:

In[4]:vec.get_feature_names()

Out[4]: ['neighborhood=Fremont',

'neighborhood=Queen Anne',

'neighborhood=Wallingford',

'price',

'rooms']

There is one clear disadvantage of this approach: if your category has many possible values, this can greatly increase the size of your dataset. However, because the encoded data contains mostly zeros, a sparse output can be a very efficient solution:

In[5]:vec=DictVectorizer(sparse=True,dtype=int)vec.fit_transform(data)

Out[5]: <4x5 sparse matrix of type '<class 'numpy.int64'>'

with 12 stored elements in Compressed Sparse Row format>

Many (though not yet all) of the Scikit-Learn estimators accept such

sparse inputs when fitting and evaluating models. sklearn.preprocessing.OneHotEncoder and

sklearn.feature_extraction.FeatureHasher are two additional tools that Scikit-Learn includes to support this type of encoding.

Text Features

Another common need in feature engineering is to convert text to a set of representative numerical values. For example, most automatic mining of social media data relies on some form of encoding the text as numbers. One of the simplest methods of encoding data is by word counts: you take each snippet of text, count the occurrences of each word within it, and put the results in a table.

For example, consider the following set of three phrases:

In[6]:sample=['problem of evil','evil queen','horizon problem']

For a vectorization of this data based on word count, we could construct

a column representing the word “problem,” the word “evil,” the word

“horizon,” and so on. While doing this by hand would be possible, we can avoid the tedium by using Scikit-Learn’s CountVectorizer:

In[7]:fromsklearn.feature_extraction.textimportCountVectorizervec=CountVectorizer()X=vec.fit_transform(sample)X

Out[7]: <3x5 sparse matrix of type '<class 'numpy.int64'>'

with 7 stored elements in Compressed Sparse Row format>

The result is a sparse matrix recording the number of times each word

appears; it is easier to inspect if we convert this to a DataFrame with

labeled columns:

In[8]:importpandasaspdpd.DataFrame(X.toarray(),columns=vec.get_feature_names())

Out[8]: evil horizon of problem queen

0 1 0 1 1 0

1 1 0 0 0 1

2 0 1 0 1 0

There are some issues with this approach, however: the raw word counts lead to features that put too much weight on words that appear very frequently, and this can be suboptimal in some classification algorithms. One approach to fix this is known as term frequency–inverse document frequency (TF–IDF), which weights the word counts by a measure of how often they appear in the documents. The syntax for computing these features is similar to the previous example:

In[9]:fromsklearn.feature_extraction.textimportTfidfVectorizervec=TfidfVectorizer()X=vec.fit_transform(sample)pd.DataFrame(X.toarray(),columns=vec.get_feature_names())

Out[9]: evil horizon of problem queen

0 0.517856 0.000000 0.680919 0.517856 0.000000

1 0.605349 0.000000 0.000000 0.000000 0.795961

2 0.000000 0.795961 0.000000 0.605349 0.000000

For an example of using TF–IDF in a classification problem, see “In Depth: Naive Bayes Classification”.

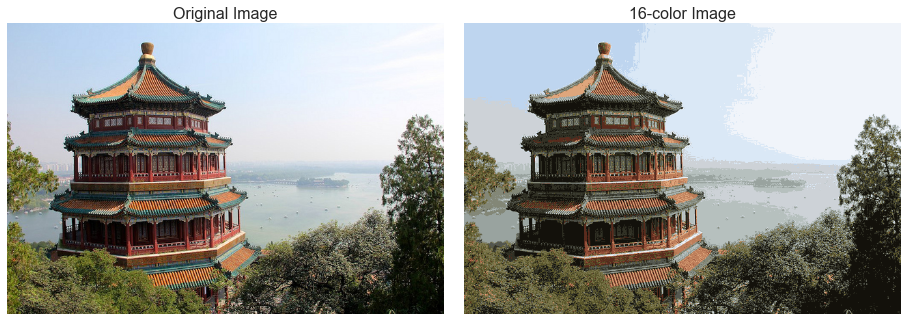

Image Features

Another common need is to suitably encode images for machine learning analysis. The simplest approach is what we used for the digits data in “Introducing Scikit-Learn”: simply using the pixel values themselves. But depending on the application, such approaches may not be optimal.

A comprehensive summary of feature extraction techniques for images is well beyond the scope of this section, but you can find excellent implementations of many of the standard approaches in the Scikit-Image project. For one example of using Scikit-Learn and Scikit-Image together, see “Application: A Face Detection Pipeline”.

Derived Features

Another useful type of feature is one that is mathematically derived from some input features. We saw an example of this in “Hyperparameters and Model Validation” when we constructed polynomial features from our input data. We saw that we could convert a linear regression into a polynomial regression not by changing the model, but by transforming the input! This is sometimes known as basis function regression, and is explored further in “In Depth: Linear Regression”.

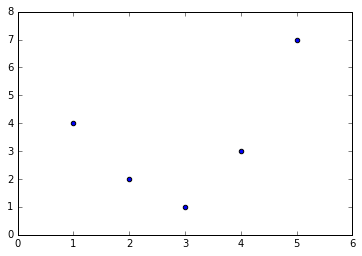

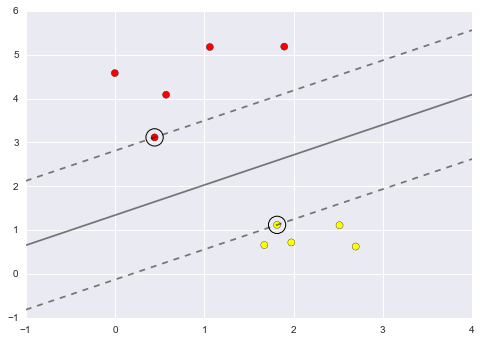

For example, this data clearly cannot be well described by a straight line (Figure 5-35):

In[10]:%matplotlibinlineimportnumpyasnpimportmatplotlib.pyplotaspltx=np.array([1,2,3,4,5])y=np.array([4,2,1,3,7])plt.scatter(x,y);

Figure 5-35. Data that is not well described by a straight line

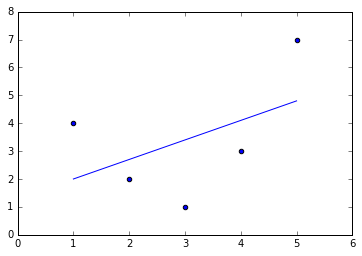

Still, we can fit a line to the data using LinearRegression and get

the optimal result (Figure 5-36):

In[11]:fromsklearn.linear_modelimportLinearRegressionX=x[:,np.newaxis]model=LinearRegression().fit(X,y)yfit=model.predict(X)plt.scatter(x,y)plt.plot(x,yfit);

Figure 5-36. A poor straight-line fit

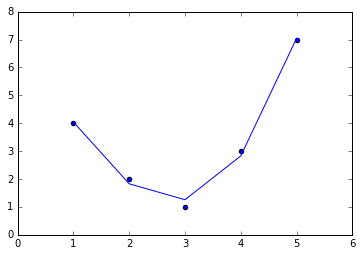

It’s clear that we need a more sophisticated model to describe the

relationship between  and

and  . We can do this by transforming the data, adding extra columns of features to drive

more flexibility in the model. For example, we can add polynomial

features to the data this way:

. We can do this by transforming the data, adding extra columns of features to drive

more flexibility in the model. For example, we can add polynomial

features to the data this way:

In[12]:fromsklearn.preprocessingimportPolynomialFeaturespoly=PolynomialFeatures(degree=3,include_bias=False)X2=poly.fit_transform(X)(X2)

[[ 1. 1. 1.] [ 2. 4. 8.] [ 3. 9. 27.] [ 4. 16. 64.] [ 5. 25. 125.]]

The derived feature matrix has one column representing  ,

and a second column representing

,

and a second column representing  , and a third column

representing

, and a third column

representing  . Computing a linear regression on this

expanded input gives a much closer fit to our data (Figure 5-37):

. Computing a linear regression on this

expanded input gives a much closer fit to our data (Figure 5-37):

In[13]:model=LinearRegression().fit(X2,y)yfit=model.predict(X2)plt.scatter(x,y)plt.plot(x,yfit);

Figure 5-37. A linear fit to polynomial features derived from the data

This idea of improving a model not by changing the model, but by transforming the inputs, is fundamental to many of the more powerful machine learning methods. We explore this idea further in “In Depth: Linear Regression” in the context of basis function regression. More generally, this is one motivational path to the powerful set of techniques known as kernel methods, which we will explore in “In-Depth: Support Vector Machines”.

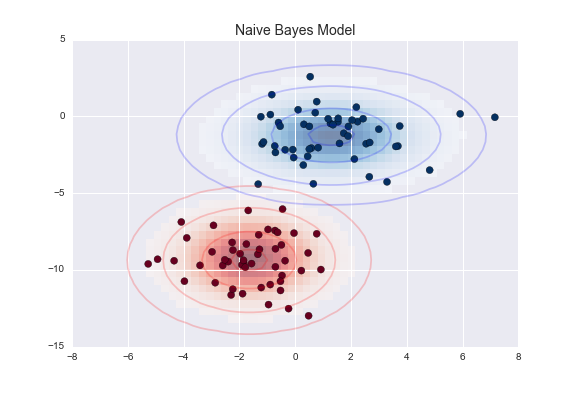

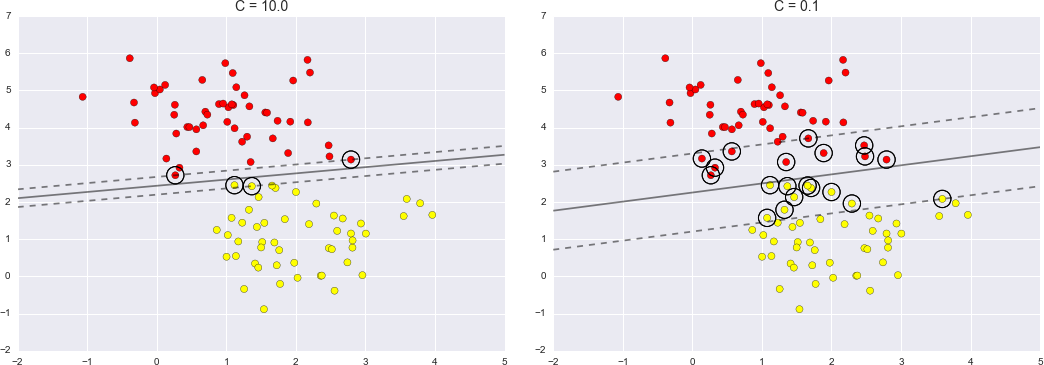

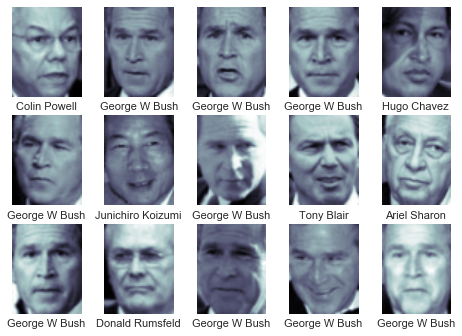

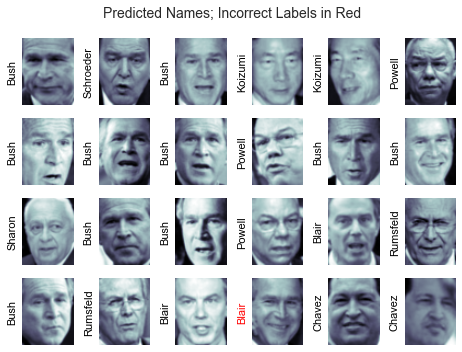

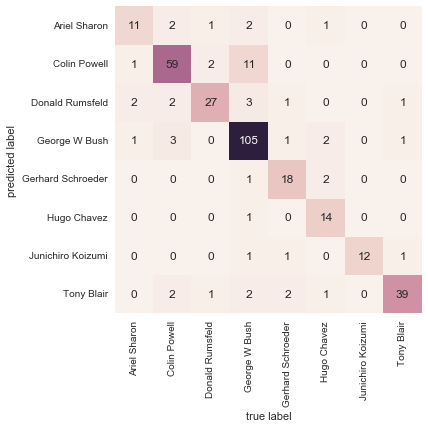

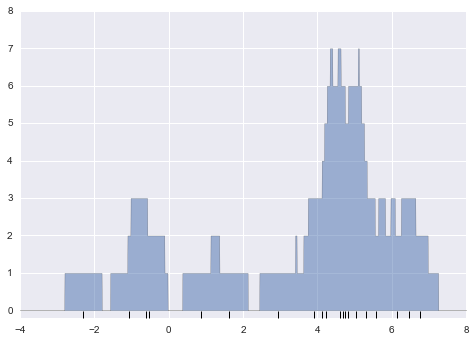

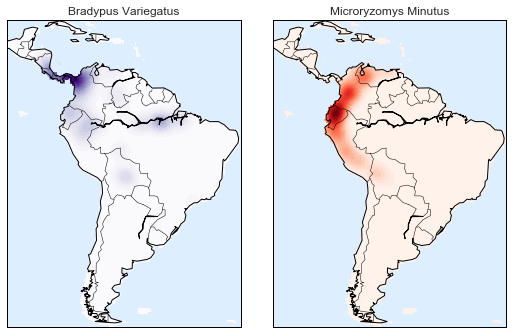

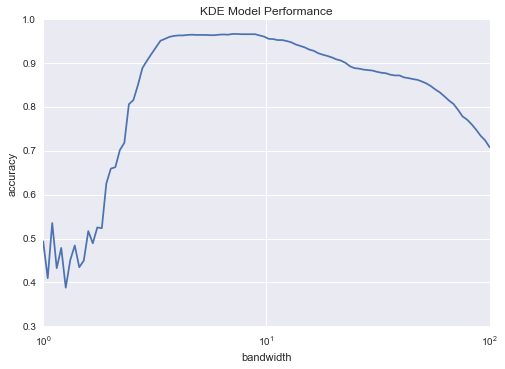

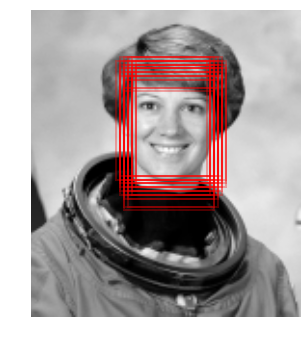

Imputation of Missing Data