We started the book with a simple definition of functions, then we saw how to use functions to do great things using the functional programming technique. We have seen how to handle arrays, objects, and error handling, in pure functional terms. It has been quite a long journey for us, but we still have not talked about yet another important technique that every JavaScript developer should be aware of: asynchronous code.

You have dealt with a great deal of asynchronous codes in your project. You might be wondering whether functional programming can help developers in asynchronous code. The answer is yes and no. The technique that we’re going to showcase initially is using ES6 Generators and then using Async/Await, which is a new addition to the ECMAScript 2017/ES8 specification. Both the patterns try to solve the same callback problem in their own way, so pay close attention to the subtle differences. Generators were new specs for functions in ES6. Generators are not really a functional programming technique; however, they are part of a function (functional programming is about function, right?); for that reason we have dedicated a chapter to it in this functional programming book.

Even if you are a big fan of Promises (which is a technique for solving the callback problem), we still advise you to have a look at this chapter. You are likely to love generators and the way they solve the async code problems.

Note

The chapter examples and library source code are in branch chap10. The repo’s URL is https://github.com/antsmartian/functional-es8.git .

Once you check out the code, please check out branch chap10:

git checkout -b chap10 origin/chap10

For running the codes, as before run:

...npm run playground...

Async Code and Its Problem

Before we really see what generators are, let’s discuss the problem of handling async code in JavaScript in this section. We are going to talk about a callback hell problem. Most of the async code patterns like Generators or Async/Await try to solve the callback hell problem in their own ways. If you already know what it is, feel free to move to the next section. For others, please read on.

Callback Hell

Synchronous Functions

Asynchronous Functions

Synchronous vs. Asynchronous

Synchronous is when the function blocks the caller when it is executing and returns the result once it’s available.

Asynchronous is when the function doesn't block the caller when it’s executing the function but returns the result once available.

We deal with Asynchronous heavily when we deal with an AJAX request in our project.

Async Functions Calling Example

Oops! You can see in Listing 10-3 that we are passing many callback functions to our async functions. This little piece of code showcases what callback hell is. Callback hell makes the program harder to understand. Handling errors and bubbling the errors out of callback are tricky and always error prone.

Before ES6 arrived, JavaScript developers used Promises to solve this problem. Promises are great, but given the fact that ES6 introduced generators at a language level, we don’t need Promises anymore!

Generators 101

As mentioned, generators were part of the ES6 specifications and they are bundled up at language level. We talked about using generators to help with handling async code. Before we get there, though, we are going to talk about the fundamentals of generators. This section focuses on explaining the core concepts behind generators. Once we learn the basics, we can create a generic function using generators to handle async code in our library. Let’s begin.

Creating Generators

First Simple Generator

Caveats of Generators

The preceding examples show how to create a generator, how to create an instance for it, and how it gets values. There are a few important things we need to take care of, though, while we are working with generators.

As you can see in this code, calling next for the second time will return an undefined rather than first generator. The reason is that generators are like sequences: Once the values of the sequence are consumed, you cannot consume it again. In our case generatorResult is a sequence that has value as first generator. With our first call to next, we (as the caller of the generator) have consumed the value from the sequence. Because the sequence is empty now, calling it a second time will return you undefined.

This code also shows that different instances of generators can be in different states. The key takeaway here is that each generator’s state depends on how we are calling the next function on it.

yield Keyword

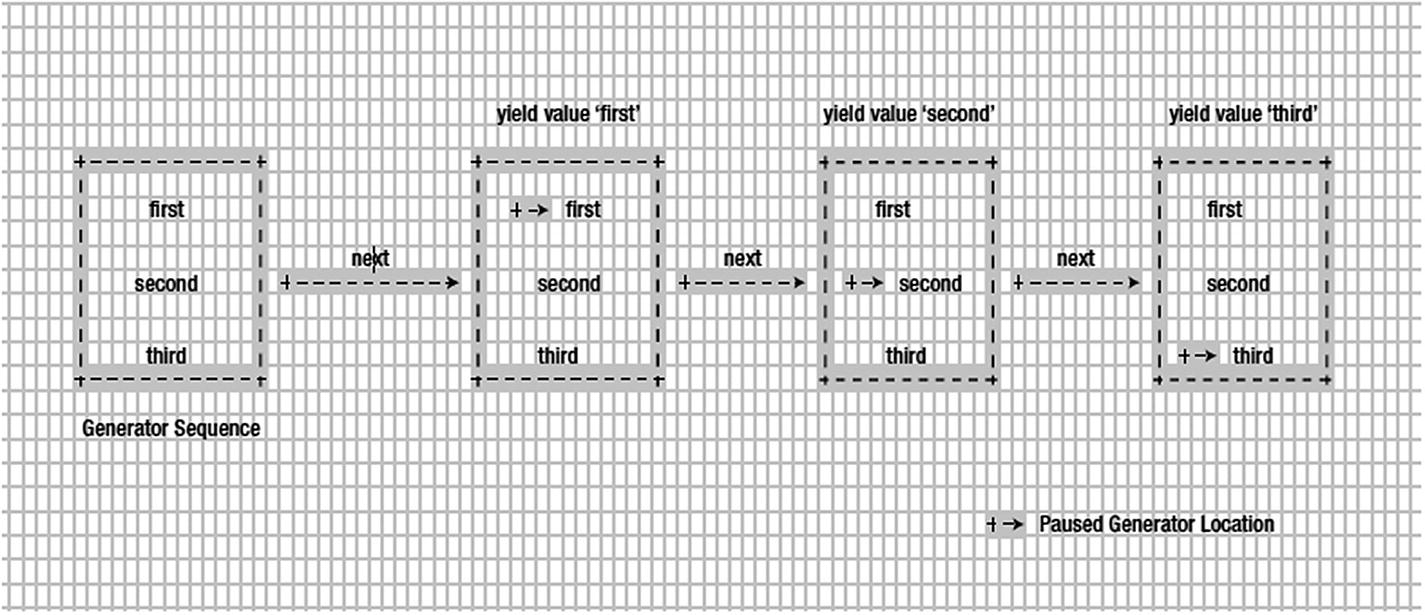

Simple Generator Sequence

for the first time, when we call it for a second time (using the same instance variable), we get back the value second. What happens when we call it for the third time? Yes, we will get back the value third.

Calling Our Generator Sequence

Visual view of generator listed in Listing 10-4

With that understanding in place, you can see why we call a generator a sequence of values. One more important point to keep in mind is that all generators with yield will execute in lazy evaluation order.

Lazy Evaluation

What is lazy evaluation? To put it in simple terms, lazy evaluation means the code won’t run until we ask it to run. As you can guess, the example of the generatorSequence function shows that generators are lazy evaluated. The values are being executed and returned only when we ask for them. That’s so lazy about generators, isn’t it?

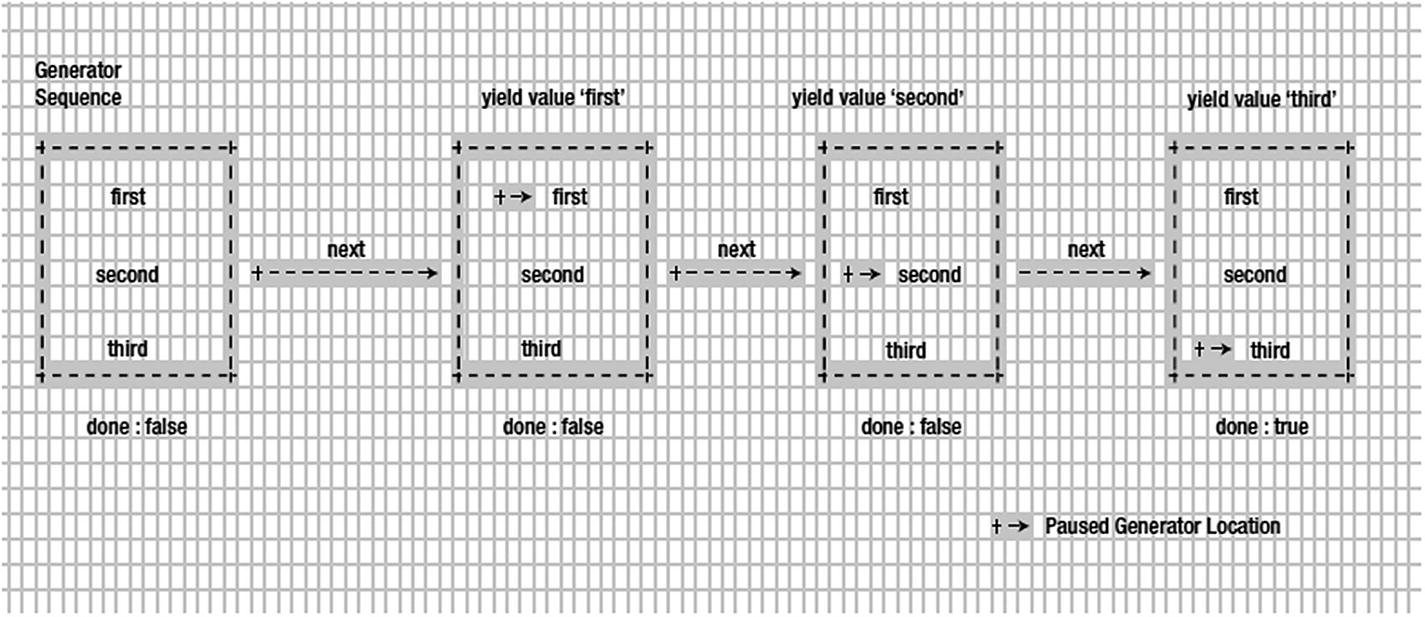

done Property of Generator

Now we have seen how a generator can produce a sequence of values lazily with the yield keyword. A generator can also produce n numbers of sequence; as a user of the generator function, how will you know when to stop calling next? Because calling next on your already consumed generator sequence will return the undefined value. How can you handle this situation? This is where the done property enters the picture.

We are aware that the value is the value from our generator, but what about done? done is a property that is going to tell whether the generator sequence has been fully consumed or not.

Code for Understanding done Property

View of generators done property for generatorSequence

notably for using the generator’s done property to iterate through it.

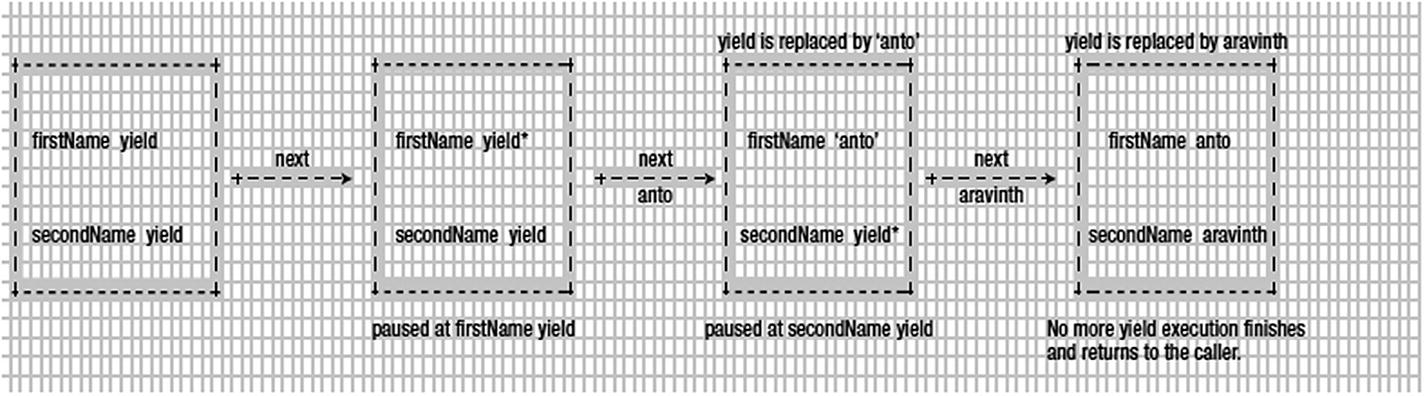

Passing Data to Generators

In this section, let’s discuss how we pass data to generators. Passing data to generators might feel confusing at first, but as you will see in this chapter, it makes async programming easy.

Passing Data Generator Example

Explaining how data are passed to sayFullName generator

You might be wondering why we need such an approach. It turns out that using generators by passing data to them makes it very powerful. We use the same technique in the next section to handle async calls.

Using Generators to Handle Async Calls

In this section, we are going to use generators for real-world stuff. We are going to see how passing data to generators makes them very powerful to handle async calls. We are going to have quite a lot of fun in this section.

Generators for Async: A Simple Case

In this section, we are going to see how to use generators for handling async code. Because we are getting started with a different mindset of using generators to solve the async problem, we want to keep things simple, so we will mimic the async calls with setTimeout calls !

Simple Asynchronous Functions

Now as you notice, we are passing the callbacks to get back the response. We have talked about how bad the callback hell can be in async code. Let’s use our generator knowledge to solve the current problem. We now change both the functions getDataOne and getDataTwo to use generator instances rather than callbacks for passing the data.

Changing getDataOne to Use Generator

Changing getDataTwo to Use Generator

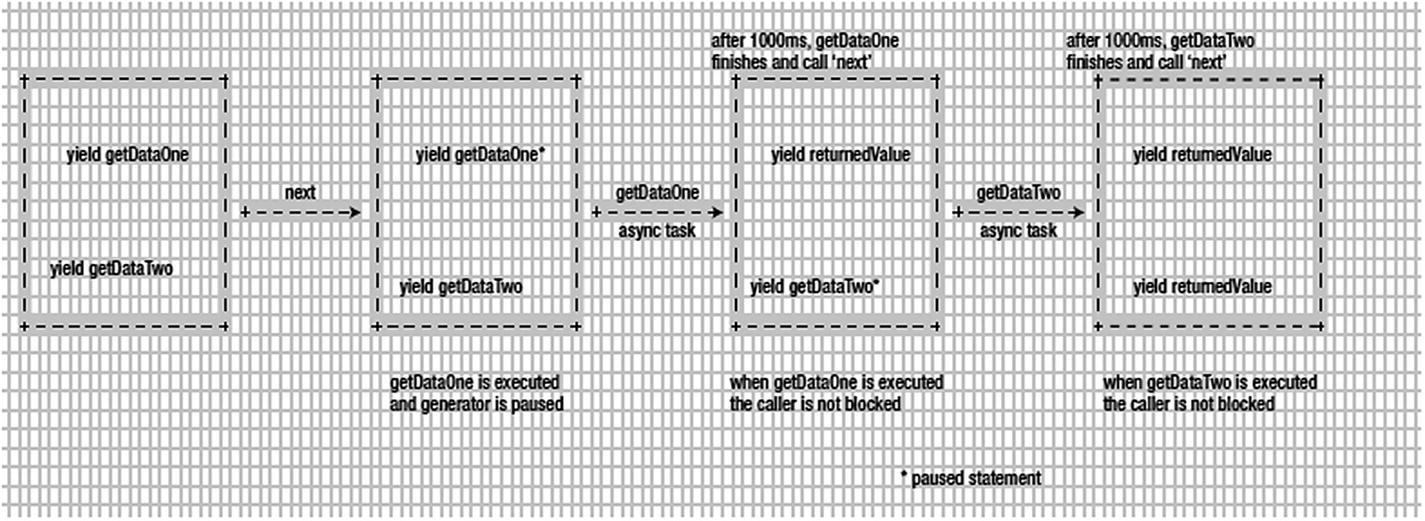

main Generator Function

That is what exactly we wanted. Look at our main code; the code looks like synchronous calls to the functions getDataOne and getDataTwo. However both these calls are asynchronous. Remember that these calls never block and they work in async fashion. Let’s distill how this whole process works.

Now the generator will be put into pause mode as it has seen a yield statement. Before it’s been put into pause mode, though, it calls the function getDataOne.

Note

An important point here is that even though the yield makes the statement pause, it won’t make the caller wait (i.e., caller is not blocked). To make the point more concrete, see the following code.

generator.next() //even though the generator pause for Async codes

console.log("will be printed")

=> will be printed

=> Generator data result is printed

This code shows that even though our generator.next causes the generator function to wait on the next call, the caller (the one who is calling the generator) won’t be blocked! As you can see, console.log will be printed (showcasing generator.next isn’t blocked), and then we get the data from the generator once the async operation is done.

Image explaining how main generator works internally

Now you have made an asynchronous call look like a synchronous call, but it works in an asynchronous way.

Generators for Async: A Real-World Case

In the previous section, we saw how to handle asynchronous code using generators effectively. To mimic the async workflow we used setTimeout. In this section, we are going to use a function to fire a real AJAX call to Reddit APIs to showcase the power of generators in the real world.

httpGetAsync Function Definition

This is a simple function that uses an https module from a node to fire an AJAX call to get the response back.

Note

Here we are not going to see in detail how httpGetAsync function works. The problem we are trying to solve is how to convert functions like httpGetAsync, which works the async way but expects a callback to get the response from AJAX calls.

Imagine we want to get the URL of the first children of the array; we need to navigate to data.children[0].data.url . This will give us a URL like https://www.reddit.com/r/pics/comments/5bqai9/introducing_new_rpics_title_guidelines/ . Because we need to get the JSON format of the given URL, we need to append .json to the URL, so that it becomes https://www.reddit.com/r/pics/comments/5bqai9/introducing_new_rpics_title_guidelines/.json .

This code will print the data as required. We are least worried about the data being printed, but we are worried about our code structure. As we saw at the beginning of this chapter, code that looks like this suffers from callback hell. Here there are two levels of callbacks, which might not be a real problem, but what if it goes to four or five nested levels? Can you read such codes easily? Definitely not. Now let’s find out how to solve the problem via generator.

request Function

main Generator Function

This main function looks very similar to the main function we defined in Listing 10-11 (the only change is the method call details). In the code we are yielding on two calls to request. As we saw in the setTimeout example, calling yield on request will make it pause until request calls the generator next by sending the AJAX response back. The first yield will get the JSON of pictures, and the second yield gets the first picture data by calling request, respectively. Now we have made the code look like synchronous code, but in reality, it works in an asynchronous fashion.

We have also escaped from callback hell using generators. Now the code looks clean and clearly tells what it’s doing. That’s so much more powerful for us!

It’s going to print the data as required. We have clearly seen how to use generators to convert any function that expects a callback mechanism into a generator-based one. In turn, we get back clean code for handling an asynchronous operation.

Async Functions in ECMAScript 2017

So far, we have seen multiple ways to run functions asynchronously. Primitively the only way to perform background jobs was by using a callback, but we just learned how they result in callback hell. Generators or sequences provide one way of solving the callback hell problem using the yield operator and generator functions. As part of the ECMA8 script, two new operators are introduced, called async and await . These two new operators solve the callback hell problem by introducing a modern design pattern for authoring asynchronous code using Promise.

Promise

Now if you have successfully relearned the philosophy of Promise , we can understand what async and await do.

Await

An await is a keyword that can be prepended to a function if the function returns a Promise object, thus making it run in the background. Usually a function or another Promise is used to consume a Promise, and await simplifies the code by allowing the Promise to resolve in the background. In other words, the await keyword waits for the Promise to resolve or fail. Once the Promise is resolved, the data returned by the Promise—either resolved or rejected—can be consumed, but meanwhile the main flow of the application is unblocked to perform any other important tasks. The rest of the execution unfolds when the Promise completes.

Async

A function that uses await should be marked as async.

Chaining Callbacks

The beauty of async and await is harder to understand until we see some sample uses of remote API calls. What follows is an example where we call a remote API that returns a JSON array. We silently wait for the array to arrive and process the first object and make another remote API call. The important thing to learn here is that while all this is happening, the main thread can work on something else because the remote API calls might take some time; hence the network call and corresponding processing is happening in the background.

You can observe that we have made dependent remote API calls asynchronously, yet the code appears flat and readable, so the call hierarchy can grow to any extent without involving any callback hierarchies.

Error Handling in Async Calls

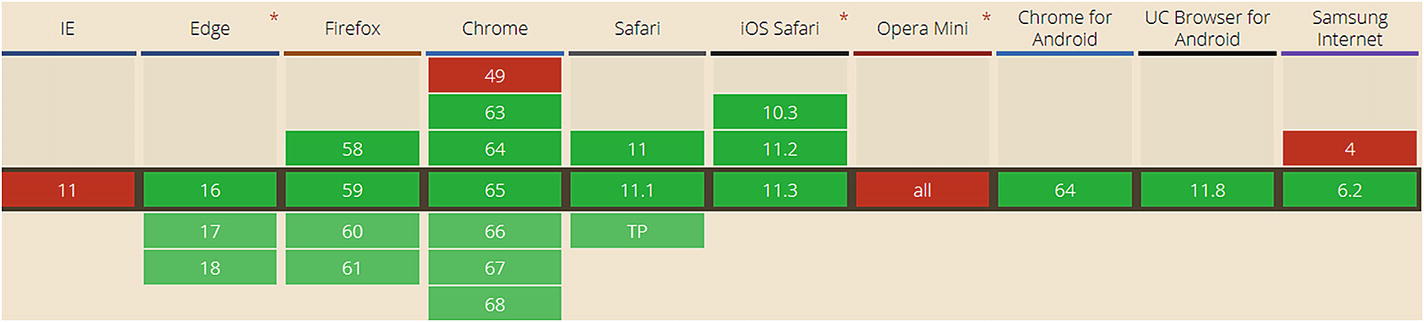

Asynchronous browser support. Source: https://caniuse.com/#feat=async-functions

Async Functions Transpiled to Generators

For example, the preceding async function will be transpiled to the following code, and you can use any online Babel transpiler like https://babeljs.io to watch the transformation. Detailed explanation of the transpiled code is beyond the scope of this book but you might notice that the keyword async is converted into a wrapper function called _asyncToGenerator (line 3). _asyncToGenerator is a routine that Babel adds. This function will be pulled into the transpiled code for any piece of code that uses the async keyword. The crux of our preceding code is converted into a switch case statement (lines 41–59) where each line of code is transpiled into a case as shown here.

Nevertheless async/await and generators are the two most prominent ways of authoring linear-looking asynchronous functions in JavaScript. The decision on which one to use is purely a matter of choice. The async/await pattern makes async code look like sync and therefore increases readability, whereas generators provide finer control over the state changes within the generator and two-way communication between the caller and the callee.

Summary

The world is full of AJAX calls. There was a time when handling AJAX calls we needed to pass a callback to process the result. Callbacks have their own limitations. Too many callbacks create callback hell problems, for example. We have seen in this chapter a type in JavaScript called generator. Generators are functions that can be paused and resumed using the next method. The next method is available on all generator instances. We have seen how to pass data to generator instances using the next method. The technique of sending data to generators helps us to solve the asynchronous code problem. We have seen how to use generators to make asynchronous code look synchronous, which is an immensely powerful technique for any JavaScript developer. Generators are one way of solving the callback hell problem, but ES8 offers another intuitive way to solve the same problem using async and await. The new asynchronous pattern is transpiled into generators in the background by compilers like Babel and uses the Promise object. Async/await can be used to write linear asynchronous functions in a simple, elegant manner. Await (an equivalent of yield in generators) can be used with any function that returns a Promise object and a function should be tagged async if it uses await anywhere within the body. The new patterns also make error handling easy, as the exceptions raised by both synchronous and asynchronous code can be handled in an equivalent manner.