Copyright © 2014 Packt Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the author, nor Packt Publishing, and its dealers and distributors will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by this book.

Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information.

First published: November 2014

Production reference: 1141114

Published by Packt Publishing Ltd.

Livery Place

35 Livery Street

Birmingham B3 2PB, UK.

ISBN 978-1-78398-800-6

Author

Y.E Liang

Reviewers

Jan Borgelin

Sergio Viudes Carbonell

Moxley Stratton

Mihai Vilcu

Commissioning Editor

Kunal Parikh

Acquisition Editor

Llewellyn Rozario

Content Development Editors

Shali Sasidharan

Anila Vincent

Technical Editor

Mrunal M. Chavan

Copy Editors

Sarang Chari

Rashmi Sawant

Project Coordinator

Neha Bhatnagar

Proofreaders

Simran Bhogal

Maria Gould

Ameesha Green

Paul Hindle

Indexer

Tejal Soni

Production Coordinator

Aparna Bhagat

Cover Work

Aparna Bhagat

Y.E Liang is a researcher, author, web developer, and business developer. He has experience in both frontend and backend development, particularly in engineering, user experience using JavaScript/CSS/HTML, and performing social network analysis. He has authored multiple books and research papers.

Jan Borgelin is a technical geek with over 15 years of professional software development experience. He currently works as the CTO at BA Group Ltd., a consultancy based in Finland. In his daily work with modern web applications, JavaScript security has become an increasingly important topic as more and more business logic is being implemented within browsers.

Sergio Viudes Carbonell is a 32-year-old mobile developer (apps and games) from Elche, Spain.

He studied Computer Science at the University of Alicante. Then, he worked on developing computer programs and web apps. Now, he works as a mobile developer, creating apps and video games for Android, iOS, and the Web.

He has previously reviewed AndEngine for Android Game Development Cookbook and Mobile Game Design Essentials. Both of these books were published by Packt Publishing. Currently, he is reviewing Mastering AndEngine Game Development, Packt Publishing.

After writing his first program in 1981 in BASIC on a Commodore CBM 8032, Moxley Stratton was hooked to programming. His interests include open source software, object-oriented design, artificial intelligence, Clojure, and computer language theory. In his past jobs, he has written software in JavaScript, CoffeeScript, Java, PHP, Perl, and C. He is currently employed with Househappy as a senior backend engineer. He enjoys playing jazz piano, surfing, snowboarding, hiking, and spending time with his daughter.

"Software testing excellence" is the motto that drives Mihai Vilcu. Having gained exposure to top technologies in both automated and manual testing, functional and nonfunctional, he became involved in numerous large-scale testing projects over several years.

Some of the applications covered by him in his career include CRMs, ERPs, billing platforms, rating, collection, payroll, and business process management applications.

Currently, as software platforms are becoming more popular in many industries, Mihai has worked in fields such as telecom, banking, healthcare, software development, Software as a Service (SaaS), and more.

You can contact him at <wwwvilcu@yahoo.com> for questions regarding testing.

For support files and downloads related to your book, please visit www.PacktPub.com.

Did you know that Packt offers eBook versions of every book published, with PDF and ePub files available? You can upgrade to the eBook version at www.PacktPub.com and as a print book customer, you are entitled to a discount on the eBook copy. Get in touch with us at <service@packtpub.com> for more details.

At www.PacktPub.com, you can also read a collection of free technical articles, sign up for a range of free newsletters and receive exclusive discounts and offers on Packt books and eBooks.

Do you need instant solutions to your IT questions? PacktLib is Packt's online digital book library. Here, you can search, access, and read Packt's entire library of books.

If you have an account with Packt at www.PacktPub.com, you can use this to access PacktLib today and view 9 entirely free books. Simply use your login credentials for immediate access.

Security issues arise from both server and client weaknesses. In this book, you will learn the basics of these security weaknesses, how to recognize them, and how to prevent them.

Chapter 1, JavaScript and the Web, provides a broad overview of the role of JavaScript in the Web. You will learn that JavaScript, besides giving behavior to web pages, can do a lot more today. JavaScript is now not only used on the client side, but also on the server side. JavaScript is almost the de facto standard way to create delightful experiences on the Web.

Chapter 2, Secure Ajax RESTful APIs, touches upon using JavaScript in tandem with RESTful APIs. We will learn how to make basic GET and POST calls to an endpoint. Subsequently, we will learn how to make malicious requests. From this chapter, we will learn more about some specific topics.

Chapter 3, Cross-site Scripting, explains what cross-site scripting is and helps you understand how such issues can occur. Most importantly, you will also learn how to minimize such risks.

Chapter 4, Cross-site Request Forgery, explains what cross-site forgery is and helps you understand how such issues can occur. Most importantly, you will also learn how to minimize such risks.

Chapter 5, Misplaced Trust in the Client, discusses a broad topic that can take place in many forms. In general, misplaced trust in the client takes place when the author's JavaScript code doesn't work as intended due to malicious actions by an adversary.

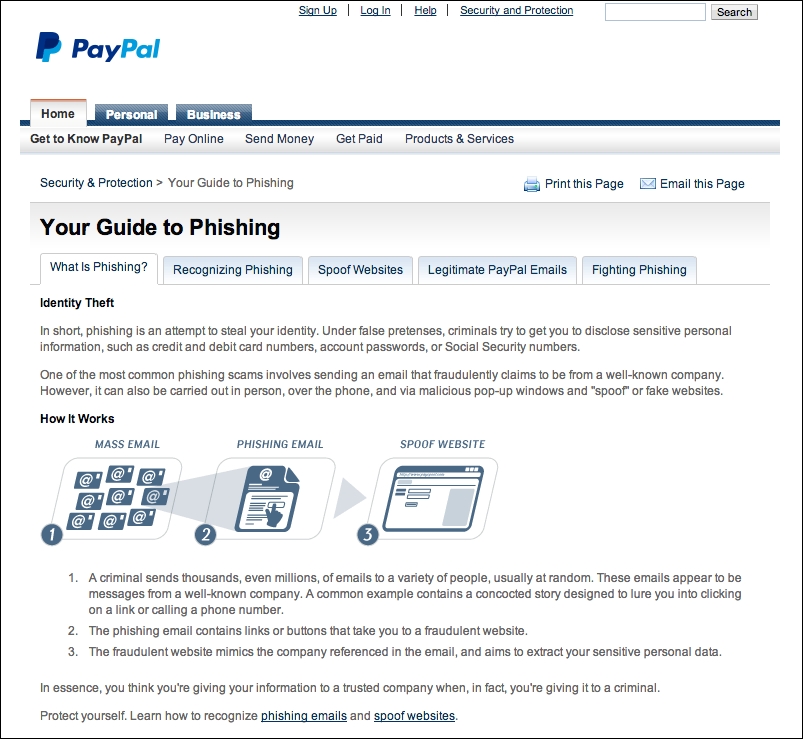

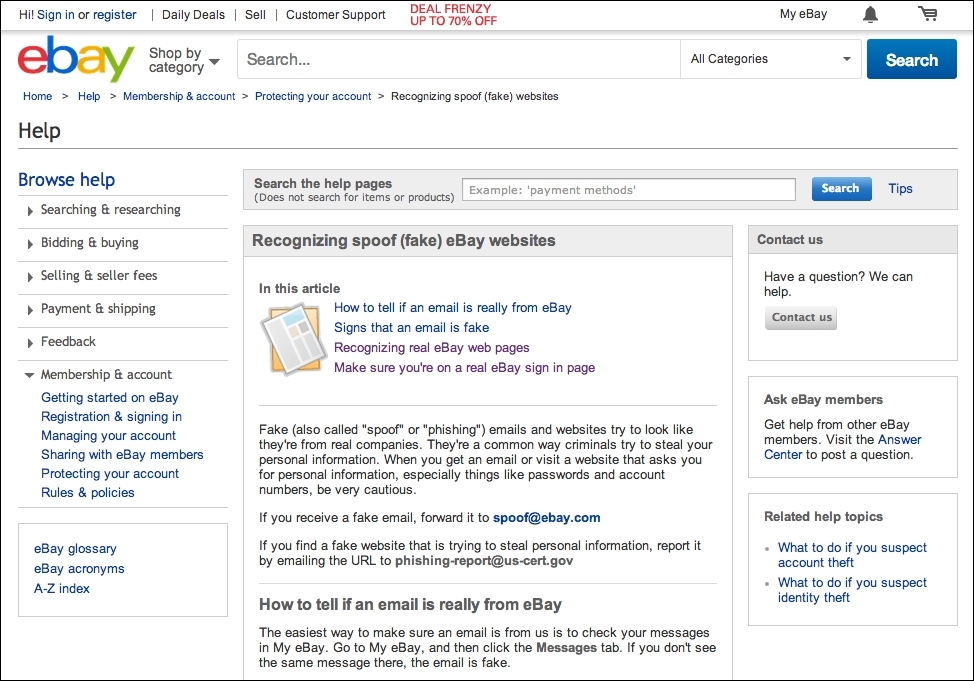

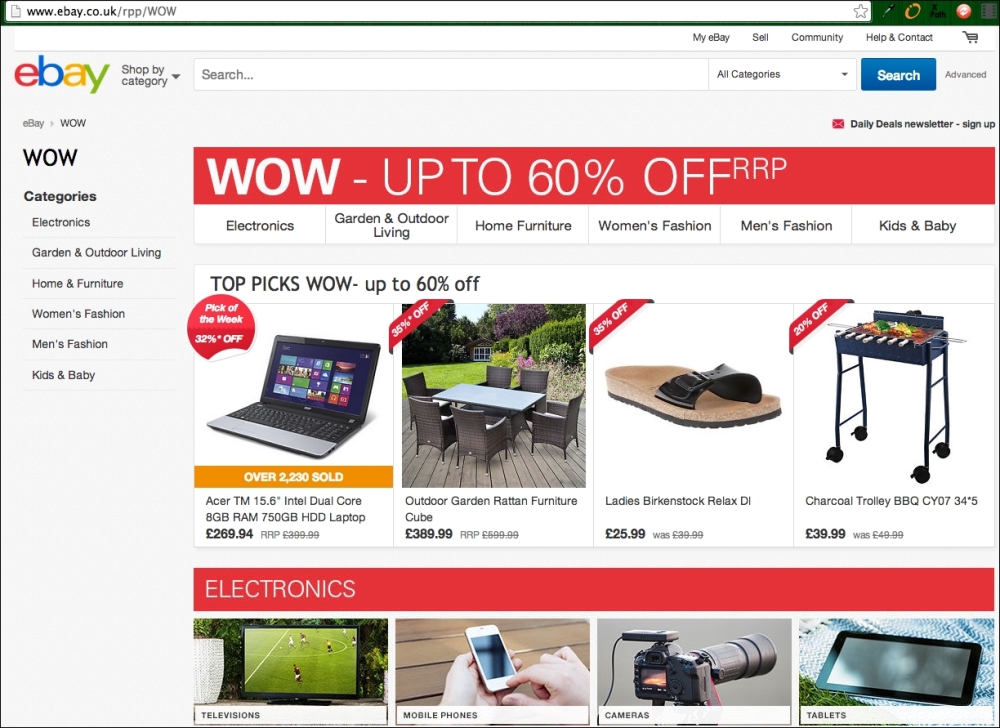

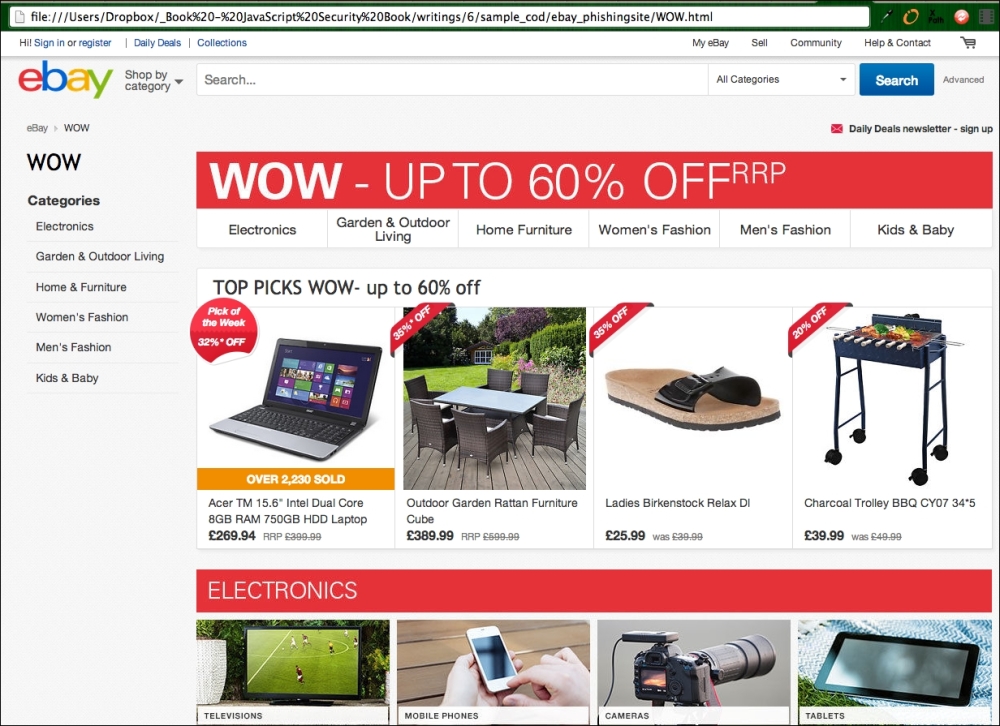

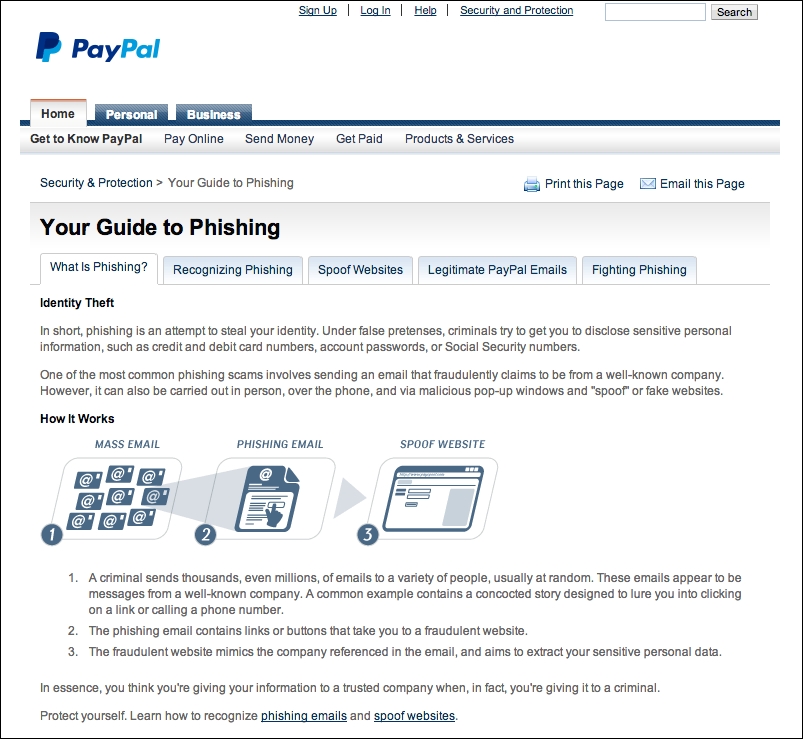

Chapter 6, JavaScript Phishing, explores the different ways in which JavaScript can be used to achieve a malicious end. JavaScript phishing is usually associated with online identity theft and privacy intrusion.

You will need the following in order to go through this book successfully:

This book is for readers who have knowledge of JavaScript scripting and are comfortable with using JavaScript (such as using jQuery) to consume Web APIs. Some Python scripting experience is useful but not required. Most importantly, readers should be curious to know about the basics of JavaScript security.

In this book, you will find a number of text styles that distinguish between different kinds of information. Here are some examples of these styles and an explanation of their meaning.

Code words in text, database table names, folder names, filenames, file extensions, pathnames, dummy URLs, user input, and Twitter handles are shown as follows: "A jQuery .get() request simply performs a GET request from a server."

A block of code is set as follows:

var jqxhr = $.get("http://example.com/data", function() {

alert( "success" );

})

.done(function() {

alert( "second success" );

})

.fail(function() {

alert( "error" );

})

.always(function() {

alert( "finished" );

});When we wish to draw your attention to a particular part of a code block, the relevant lines or items are set in bold:

var express = require('express');

var bodyParser = require('body-parser');

var app = express();

var session = require('cookie-session');

var csrf = require('csrf');

app.use(csrf());

app.use(bodyParser());Any command-line input or output is written as follows:

sudo pip install tornado==3.1 sudo pip install pymongo sudo pip install tornado-cors

New terms and important words are shown in bold. Words that you see on the screen, for example, in menus or dialog boxes, appear in the text like this: "Click on Submit."

Feedback from our readers is always welcome. Let us know what you think about this book—what you liked or disliked. Reader feedback is important for us as it helps us develop titles that you will really get the most out of.

To send us general feedback, simply e-mail <feedback@packtpub.com>, and mention the book's title in the subject of your message.

If there is a topic that you have expertise in and you are interested in either writing or contributing to a book, see our author guide at www.packtpub.com/authors.

Now that you are the proud owner of a Packt book, we have a number of things to help you to get the most from your purchase.

You can download the example code files for all Packt books you have purchased from your account at http://www.packtpub.com. If you purchased this book elsewhere, you can visit http://www.packtpub.com/support and register to have the files e-mailed directly to you.

Although we have taken every care to ensure the accuracy of our content, mistakes do happen. If you find a mistake in one of our books—maybe a mistake in the text or the code—we would be grateful if you could report this to us. By doing so, you can save other readers from frustration and help us improve subsequent versions of this book. If you find any errata, please report them by visiting http://www.packtpub.com/submit-errata, selecting your book, clicking on the Errata Submission Form link, and entering the details of your errata. Once your errata are verified, your submission will be accepted and the errata will be uploaded to our website or added to any list of existing errata under the Errata section of that title.

To view the previously submitted errata, go to https://www.packtpub.com/books/content/support and enter the name of the book in the search field. The required information will appear under the Errata section.

Piracy of copyright material on the Internet is an ongoing problem across all media. At Packt, we take the protection of our copyright and licenses very seriously. If you come across any illegal copies of our works, in any form, on the Internet, please provide us with the location address or website name immediately so that we can pursue a remedy.

Please contact us at <copyright@packtpub.com> with a link to the suspected pirated material.

We appreciate your help in protecting our authors, and our ability to bring you valuable content.

You can contact us at <questions@packtpub.com> if you are having a problem with any aspect of the book, and we will do our best to address it.

First of all, welcome to the book! In this chapter, I will give a very high-level overview of JavaScript, such as some of the basic things it can do on the Web both on the client side and on the server side. After that, I will dive into some of the basic examples of JavaScript security issues.

Here's what we will learn in this chapter:

JavaScript provides behavior to your web pages. From changing your HTML elements' positioning to performing Ajax operations, there are many things that JavaScript can do now compared to just a few years ago. Here's just a basic list of things that JavaScript can do:

Most importantly, with the rise of JavaScript libraries, such as jQuery, AngularJS, ReactJS, and more, achieving all this has never been easier. We'll see multiple examples of JavaScript with the use of jQuery just to give you a taste of some of the code we will see and use throughout this book.

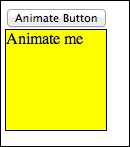

For this section, we'll start with some basic animation effects before moving on to the topics that may be of concern in security-related topics. You will also need a text editor and a browser in order to test the code.

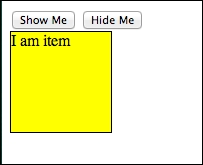

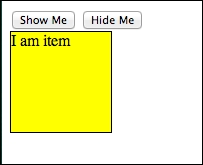

We'll start off with simple hide/show effects.

To perform hide/show actions, we can make use of jQuery's hide() and show() functions. For example, consider the following code:

<html>

<head>

<style>

#item {

display: block;

height:100px;

width:100px;

border:1px solid black;

background-color: yellow

}

</style>

<script src="http://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/1.11.1/jquery.min.js"></script>

<script>

$(document).ready(function() {

$("#hide").click(function(){

$("#item").hide();

});

$("#show").click(function(){

$("#item").show();

});

});

</script>

</head>

<body>

<button id="show">Show Me</button>

<button id="hide">Hide Me</button>

<div id="item">I am item</div>

</body>

</html>Downloading the example code

You can download the example code files from your account at http://www.packtpub.com for all the Packt Publishing books you have purchased. If you purchased this book elsewhere, you can visit http://www.packtpub.com/ support and register to have the files e-mailed directly to you.

Copy-and-paste this code to the hide_show.html function, and open it in your favorite browser. You should get something like this:

Simple show and hide actions

Clicking on

Show Me and Hide Me will show and hide the yellow box. You can do the same thing using the toggle() function, which we will quickly cover in the next section.

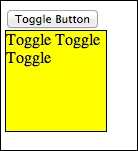

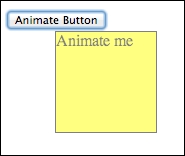

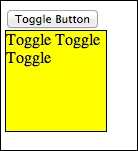

The toggle() function allows you to display and hide elements. Going back to the code we used in the previous section, create a new file and call it toggle.html. Replace the code within $(document).ready() with the following code:

$("#toggle_button").click(function(){

$("#item").toggle();

});Feel free to make some changes to your button IDs and item contents. In my case, this is how my code looks:

<html>

<head>

<style>

#item {

display: block;

height:100px;

width:100px;

border:1px solid black;

background-color: yellow

}

</style>

<script src="http://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/1.11.1/jquery.min.js"></script>

<script>

$(document).ready(function() {

$("#toggle_button").click(function(){

$("#item").toggle();

});

})

</script>

</head>

<body>

<button id="toggle_button">Toggle Button</button>

<div id="item">Toggle Toggle Toggle</div>

</body>

</html>This is what you will see when you open the file in your web browser:

Simple toggle action

Clicking on Toggle Button will allow you to hide and show the yellow box as expected.

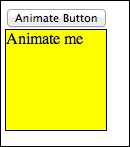

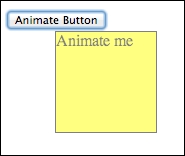

jQuery also provides easy methods to perform animations via the animate() method. Copy the previous example (toggle.html) and name it animation.html. In animation.html, make the following changes as shown in the highlighted lines of code:

<html>

<head>

<style>

#item {

display: block;

position: relative;

left:0px;

height:100px;

width:100px;

border:1px solid black;

background-color: yellow

}

</style>

<script src="http://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/1.11.1/jquery.min.js"></script>

<script>

$(document).ready(function() {

$("#animate_button").click(function(){

$("#item").animate({

opacity: 0.5,

left: "+=50",

}, 1000);

});

})

</script>

</head>

<body>

<button id="animate_button">Animate Button</button>

<div id="item">Animate me</div>

</body>

</html>We've basically changed #item to display as block with position:relative. Now, the button ID is animate_button. Notice that the animate() function works on the item when the button is clicked. The following is what you will get when you click on Animate Button:

Animation

The animation looks like the following:

Animation part 2

One of the more interesting uses of jQuery is the chaining of functions. We'll do a basic example using the chaining of built-in animations. Go back to your text editor, create a new file called chained.html, and paste the following code:

<html>

<head>

<style>

#item {

display: none;

position: relative;

left:0px;

height:100px;

width:100px;

border:1px solid black;

background-color: yellow

}

</style>

<script src="http://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/1.11.1/jquery.min.js"></script>

<script>

$(document).ready(function() {

$('#chain_button').click(function() {

$("#item").fadeIn('slow').fadeOut('slow').fadeIn('slow').

fadeOut('slow').slideDown('slow').slideUp('slow');

})

})

</script>

</head>

<body>

<button id="chain_button">Chained Button</button>

<div id="item">Chain me</div>

</body>

</html>The main thing to notice in this example is the use of the fadeIn(), fadeout(), slideDown(), and slideUp() functions. We chain the built-in animations together such that we see a series of effects when we click on the button.

Now, we focus on the jQuery Ajax operations. The basic concepts discussed here will be used in the next chapter, where we will talk about secure RESTful APIs. For a start, Ajax typically refers to Asynchronous JavaScript and XML, where your web page performs data operations with a server to get new data, create or update data, or delete data. During the past few years, with the rise in popularity of APIs (such as the Facebook Graph API and others), data is increasingly being exchanged using JSON instead of XML. Such actions typically require the cooperation of a backend server. We will not cover the server details here; for the moment, we will just focus on the jQuery operations.

In any Ajax application, single page or not, you will most likely be required to perform the basic HTTP operations, such as GET, POST, and so on. In this section, we will deal with the basic operations that you will most likely use in coding Ajax apps. Most importantly, you will use variants of this code in the later chapters.

A jQuery .get() request simply performs a GET request from a server. To perform a .get() request, you will need the following code:

var jqxhr = $.get("http://example.com/data", function() {

alert( "success" );

})

.done(function() {

alert( "second success" );

})

.fail(function() {

alert( "error" );

})

.always(function() {

alert( "finished" );

});The hypothetical endpoint in this example, http://example.com/data, can return either XML or JSON.

A jQuery .getJSON() request simply performs a GET request from a server. But this time around, we are attempting to retrieve JSON data from our server. To perform a .getJSON() request, here's what we do:

var jqxhr = $.getJSON( "http://example.com/json", function(data) {

console.log( "success" );

})

.done(function(data) {

console.log( "second success" );

})

.fail(function(data) {

console.log( "error" );

})

.always(function(data) {

console.log( "complete" );

});In this example, we perform a getJSON() request from http://example.com/json; the endpoint should return a JSON response.

If you want to change the data source of your data or create a new one, you will need to perform a POST operation on your server. In this example, we perform a .post() operation to http://example.com/endpoint, and depending on whether our Ajax request is successful or not, we create an alert with different messages. This is done with the following code:

var jqxhr = $.post( "http://example.com/endpoint", function(data) {

alert( "success" );

})

.done(function(data) {

alert( "second success" );

})

.fail(function(data) {

alert( "error" );

})

.always(function(data) {

alert( "finished" );

});JavaScript is becoming ubiquitous and more popular now. However, it has some security issues if not used properly. Two of the most commonly known examples are cross-site request forgery (CSRF) and cross-site scripting. I'll touch very briefly upon these two topics as a way to prepare you for the remainder of the book.

I decided to start off with this topic as it is generally easier to explain and understand. To put it simply, cross-site request forgery refers to a type of malicious exploitation of a website where unauthorized commands are transmitted from an unknowing user that the website trusts.

The following straightforward example involves Ajax requests: go back to earlier sections where we talked about POST requests. Imagine that your server endpoint does not defend itself against an Ajax request made outside of your domain name, and somehow, malicious POST requests are made. That particular request can somehow be made to alter your database information and more.

You may argue that we can make use of CSRF tokens (a common technique to prevent cross-domain requests and a way to provide greater security to the site) as a security measure, but it is not entirely safe. For instance, the script that is performing the attack could be residing in the website itself; the site could have been hijacked with malicious script in the first place.

In addition, if some of the following conditions are met, CSRF can be achieved:

Cross-site scripting (XSS) enables attackers to inject a client-side script (usually JavaScript) into web pages that are used by users. The general idea is that attackers use the known vulnerabilities of web-based applications, servers, plugin systems (such as WordPress), or even third-party JavaScript plugins to serve malicious scripts or content from the compromised site. The end result is that the compromised site ends up sending content that contains the malicious content/script.

If the content happens to be a piece of malicious JavaScript, then the results can be disastrous: since we know that JavaScript has global access to the web page, such as the DOM, and given the fact that that piece of JavaScript can have access to the cookies issued by the site (thus allowing the attacker to gain access to potentially useful information), that piece of JavaScript can do the following:

If you are new to all this, all you need to remember at this point in time is that such security flaws come from both server-side and client-side weaknesses. We'll be touching upon them in the next chapter.

To summarize, we went through some basic jQuery and JavaScript. We've also learned some basic ideas on how JavaScript security issues occur and what they are. From this chapter onwards, we'll go into deeper detail on individual topics introduced in this chapter. We'll start with writing secure Ajax RESTful APIs in the next chapter.

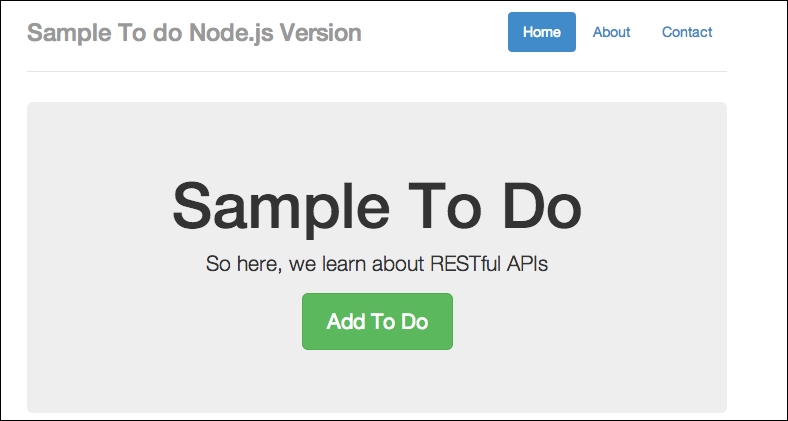

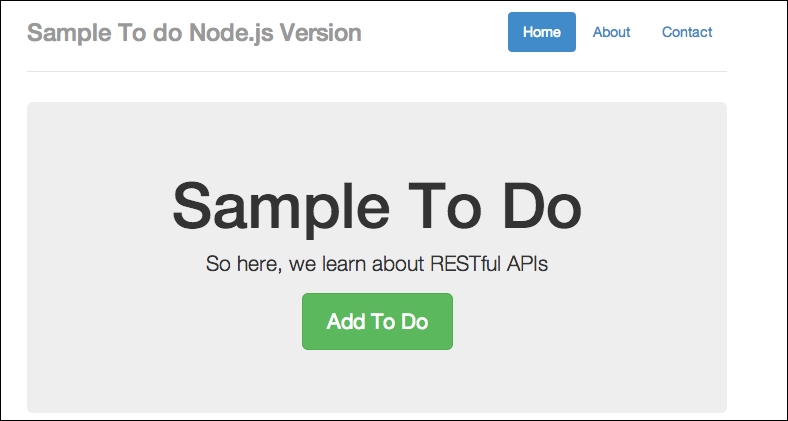

Welcome back to the book! In this chapter, we will walk through some code where we build a RESTful server, and write some frontend code on top of it so that we can create a simple to-do list app. The app is extremely simple: add and delete to-do items, after which we'll demonstrate one or two ways in which RESTful APIs can be laden with security flaws. So here we go!

As mentioned in Chapter 1, JavaScript and the Web, JavaScript is used in the server side as well. In this example, we'll use Node.js and Express.js to build a simple RESTful server before we touch upon how we can secure our RESTful APIs.

For the remainder of this book, you will require Node.js Version 0.10.2x or above, MongoDB Version 2.2 or above, and Express.js 4.x. To install them, feel free to refer to their respective installation instructions. For Node.js, refer to http://nodejs.org/, MongoDB at http://docs.mongodb.org/manual/installation/, and Express.js at http://expressjs.com/. To keep things simple, all modules installed will be installed globally.

We'll build a RESTful server using Node.js and Express.js 4.x. This RESTful server contains a few endpoints:

/api/todos:GET: This endpoint gets a full list of to-do itemsPOST: This creates a new to-do item/api/todos/:id:POST: This deletes a to-do itemThe source code for this section can be found at chapter2/node/server.js and its related content as well. Now open up your text editor and create a new file. We'll name this file server.js.

Before you start to code, make sure that you install the required packages mentioned in the previous information box.

Let's start by initializing the code:

var express = require('express');

var bodyParser = require('body-parser');

var app = express();

app.use(bodyParser());

var port = process.env.PORT || 8080; // set our port

var mongoose = require('mongoose');

mongoose.connect('mongodb://127.0.0.1/todos'); // connect to our database

var Todos = require('./app/models/todo');

var router = express.Router();

// middleware to use for all requests

router.use(function(req, res, next) {

// do logging

console.log('Something is happening.');

next();

});What we did here is that we first imported the required libraries. We then set our port at 8080, following which we connect to MongoDB via Mongoose and its associated database name.

Next, we defined a router using express.Router().

After this piece of code, include the following:

router.get('/', function(req, res) { res.sendfile('todos.html') }); router.route('/todos') .post(function(req, res) { var todo = new Todos(); todo.text = req.body.text; todo.details = req.body.details; todo.done = true; todo.save(function(err) { if (err) res.send(err); res.json(todo); }); }) .get(function(req, res) { Todos.find(function(err, _todos) { if (err) res.send(err); var todos = { 'todos':_todos } res.json(todos); }); }); router.route('/todos/:_id') .post(function(req, res) { Todos.remove({ _id: req.params._id }, function(err, _todo) { if (err) res.send(err); var todo = { _id: req.params._id } console.log("--- todo"); console.log(todo); res.json(todo); }); });

What we have here are the major API endpoints to get a list of to-do items, delete a single item, and create a single to-do item. Take note of the highlighted lines though: they return a HTML file, which basically contains the frontend code for your to-do list app. Let's now work on that file.

Let's return to your text editor and create a new file called todos.html. This is a fairly large file with quite a bit of code compared to the rest of the code samples in this book. So, you can refer to chapter2/node/todos.html to see the full source code. In this section, I'll highlight the most important pieces of code so that you have a good idea of how this piece of code works:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<title>Sample To do</title>

<!-- Bootstrap core CSS -->

<link href="//netdna.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/3.1.1/css/bootstrap.min.css" rel="stylesheet">

<style>

/* css code omitted */

</style>

<!-- HTML5 shim and Respond.js IE8 support of HTML5 elements and media queries -->

<!--[if lt IE 9]>

<script src="https://oss.maxcdn.com/libs/html5shiv/3.7.0/html5shiv.js"></script>

<script src="https://oss.maxcdn.com/libs/respond.js/1.4.2/respond.min.js"></script>

<![endif]-->

</head>

<body>

<div class="container">

<div class="header">

<ul class="nav nav-pills pull-right">

<li class="active"><a href="#">Home</a></li>

<li><a href="#">About</a></li>

<li><a href="#">Contact</a></li>

</ul>

<h3 class="text-muted">Sample To do Node.js Version</h3>

</div>

<div class="jumbotron">

<h1>Sample To Do</h1>

<p class="lead">So here, we learn about RESTful APIs</p>

<p><button id="toggleTodoForm" class="btn btn-lg btn-success" href="#" role="button">Add To Do</button></p>

<div id="todo-form" role="form">

<div class="form-group">

<label>Title</label>

<input type="text" class="form-control" id="todo_title" placeholder="Enter Title">

</div>

<div class="form-group">

<label>Details</label>

<input type="text" class="form-control" id="todo_text" placeholder="Details">

</div>

<p><button id="addTodo" class="btn btn-lg">Submit</button></p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="row marketing">

<div id="todos" class="col-lg-12">

</div>

</div>

<div class="footer">

<p>© Company 2014</p>

</div>

</div> <!-- /container -->

<!-- Bootstrap core JavaScript

================================================== -->

<!-- Placed at the end of the document so the pages load faster -->

<script src="//ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/1.11.1/jquery.min.js"></script>

<script src="//netdna.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/3.1.1/js/bootstrap.min.js"></script>

<script>

// javascript code omitted

</script>

</body>

</html>The preceding code is basically the HTML template that gives a structure and layout to our app. If you have not noticed already, this template is based on Bootstrap 3's basic examples. Some of the CSS code is omitted due to space constraints; feel free to check the source code for it.

Next, you will see that a block of JavaScript code is being omitted; this is the meat of this file:

function todoTemplate(title, body, id) {

var snippet = "<div id=\"todo_"+id+"\"" + "<h2>"+title+"</h2>"+"<p>"+body+"</p>";

var deleteButton = "<a class='delete_item' href='#' id="+id+">delete</a></div><hr>";

snippet += deleteButton;

return snippet;

}

function getTodos() {

// simply get list of to-dos when called

$.get("/api/todos", function(data, status) {

var todos = data['todos'];

var htmlString = "";

for(var i = 0; i<todos.length;i++) {

htmlString += todoTemplate(todos[i].text, todos[i].details, todos[i]._id);

}

$('#todos').html(htmlString);

})

}

function toggleForm() {

$("#toggleTodoForm").click(function() {

$("#todo-form").toggle();

})

}

function addTodo() {

var data = {

text: $('#todo_title').val(),

details:$('#todo_text').val()

}

$.post('/api/todos', data, function(result) {

var item = todoTemplate(result.text, result.details, result._id);

$('#todos').prepend(item);

$("#todo-form").slideUp();

})

}

$(document).ready(function() {

toggleForm();

getTodos();

//deleteTodo();

$('#addTodo').click(addTodo);

$(document).on("click", '.delete_item', function(event) {

var id = event.currentTarget.id;

var data = {

id:id

}

$.post('/api/todos/'+id, data, function(result) {

var item_to_slide = "#todo_"+result._id;

$(item_to_slide).slideUp();

});

});

})These JavaScript functions make use of the basic jQuery functionality that we saw in the previous section. Here's what each of the functions does:

todoTemplate(): This function simply returns the HTML that builds the appearance and content of a to-do item.toggleForm(): This makes use of jQuery's toggle() function to show and hide the form that adds the to-do item.addToDo(): This is the function that adds a new to-do item to our backend. It makes use of jQuery's post() method.$(document).ready() line, where we initialize our code.Save the file. Now, fire up your Express.js server by issuing the following command:

node server.js

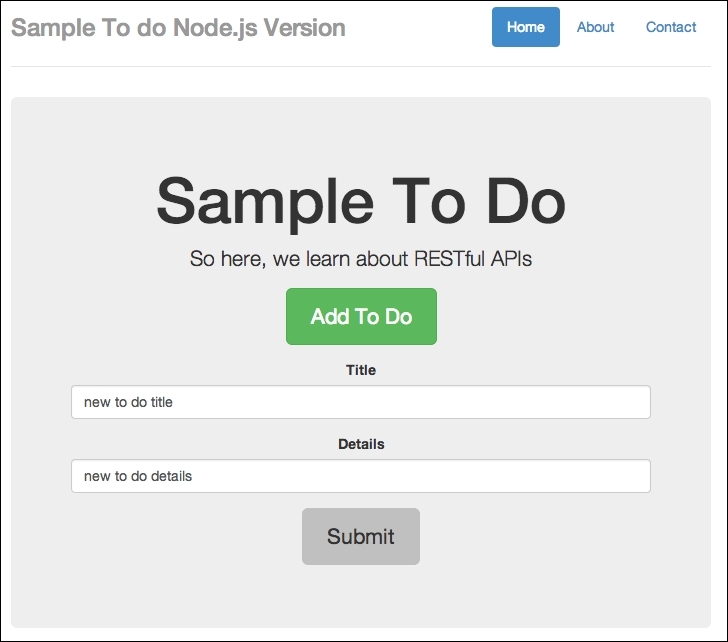

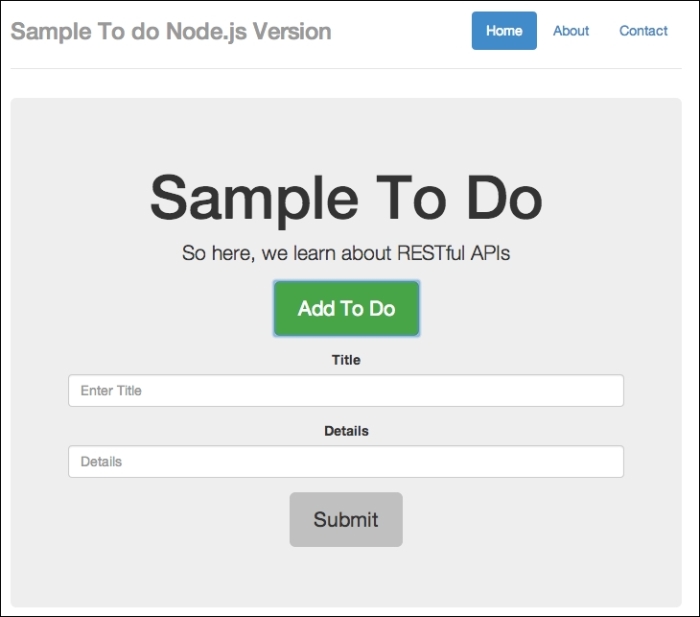

Now, you can check out your app at http://localhost:8080/api, and you should see the following screen:

A sample to-do Node.js version

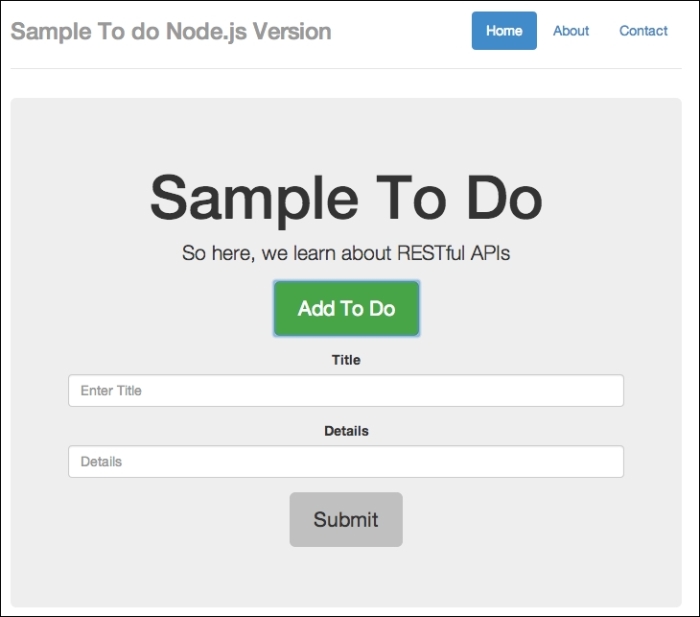

If you are getting this output, great. In my case, I already have some test data, so you can simply add new to-do items. We can do so by simply clicking on the Add To Do button. Have a look at the following screenshot:

A sample to-do form

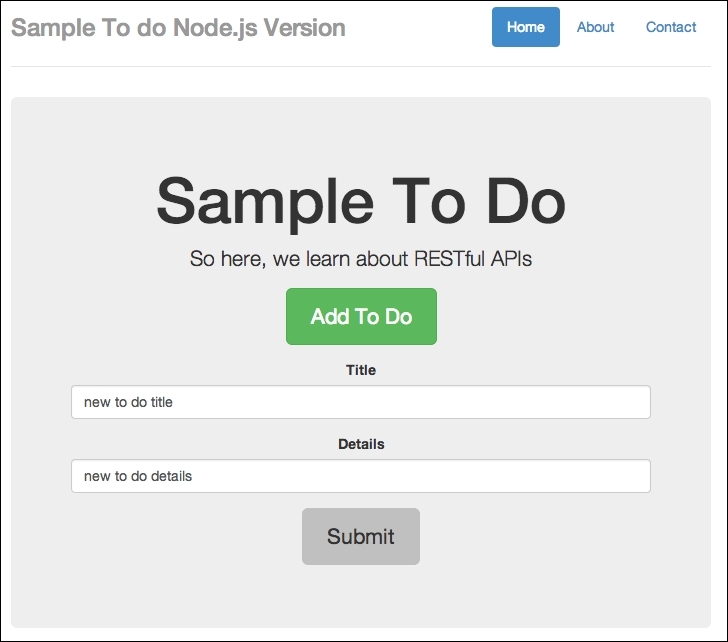

Add in some details, as follows:

Adding in some details

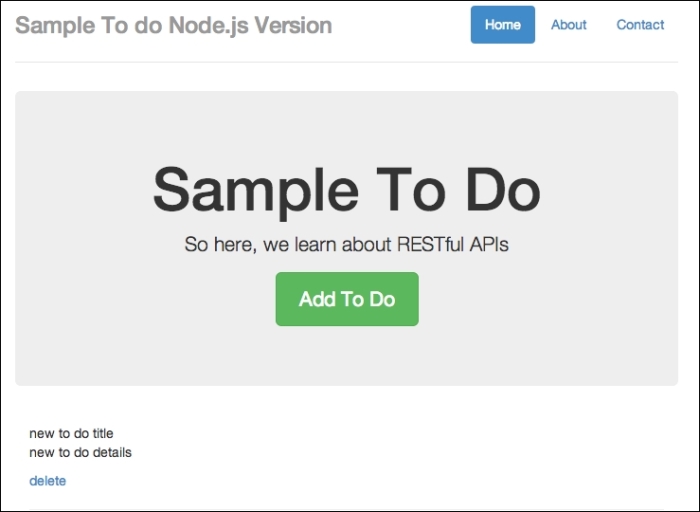

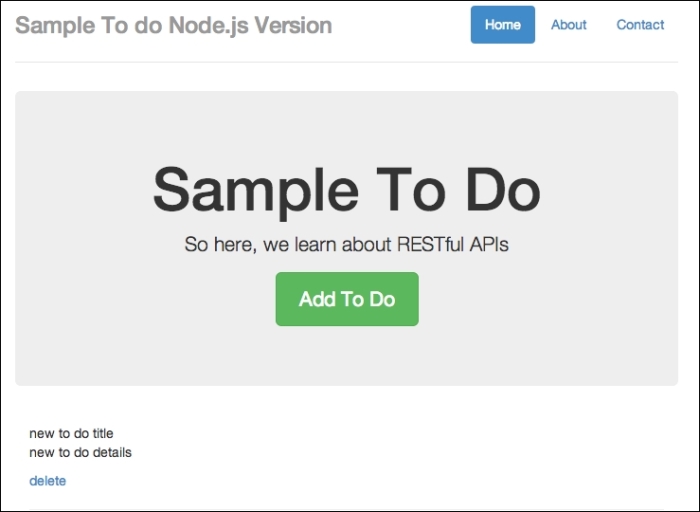

Finally, click on Submit. Have a look at the following screenshot:

New item added

You should see that the added to-do form slides up, and a new to-do item is added.

You can also delete the to-do items just to make sure that things are working all right.

Now to the fun part. I'm not sure if you've noticed, but there's at least one major security flaw in our app: our endpoints are exposed to cross-domain name operations. I want you to go back to your text editor, create a new file called external_node.html, and copy the following code in to it:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<title>Sample To do</title>

<!-- Bootstrap core CSS -->

<link href="//netdna.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/3.1.1/css/bootstrap.min.css" rel="stylesheet">

<!-- Custom styles for this template -->

<link href="/static/css/custom.css" rel="stylesheet">

<style>

#todo-form {

display:none;

}

</style>

<!-- HTML5 shim and Respond.js IE8 support of HTML5 elements and media queries -->

<!--[if lt IE 9]>

<script src="https://oss.maxcdn.com/libs/html5shiv/3.7.0/html5shiv.js"></script>

<script src="https://oss.maxcdn.com/libs/respond.js/1.4.2/respond.min.js"></script>

<![endif]-->

</head>

<body>

<div class="container">

<div class="header">

<ul class="nav nav-pills pull-right">

<li class="active"><a href="#">Home</a></li>

<li><a href="#">About</a></li>

<li><a href="#">Contact</a></li>

</ul>

<h3 class="text-muted">Sample To do</h3>

</div>

<div class="jumbotron">

<h1>External Post FORM</h1>

<p class="lead">So here, we learn about RESTful APIs</p>

<p><button id="toggleTodoForm" class="btn btn-lg btn-success" href="#" role="button">Add To Do</button></p>

<div id="todo-form" role="form">

<!-- <script>alert("you suck");</script> -->

<div class="form-group">

<label>Title</label>

<input type="text" class="form-control" id="todo_title" placeholder="Enter Title">

</div>

<div class="form-group">

<label>Details</label>

<input type="text" class="form-control" id="todo_text" placeholder="Details">

</div>

<p><button id="addTodo" class="btn btn-lg">Submit</button></p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="row marketing">

<div id="todos" class="col-lg-12">

</div>

</div>

<div class="footer">

<p>© Company 2014</p>

</div>

</div> <!-- /container -->

<!-- Bootstrap core JavaScript

================================================== -->

<!-- Placed at the end of the document so the pages load faster -->

<script src="//ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/1.11.1/jquery.min.js"></script>

<script src="//netdna.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/3.1.1/js/bootstrap.min.js"></script>

<script>

function todoTemplate(title, body) {

var snippet = "<h2>"+title+"</h2>"+"<p>"+body+"</p><hr>";

return snippet;

}

function getTodos() {

// simply get list of to-dos when called

$.get("/api/todos", function(data, status) {

var todos = data['todos'];

var htmlString = "";

for(var i = 0; i<todos.length;i++) {

htmlString += todoTemplate(todos[i].text, todos[i].details);

}

$('#todos').html(htmlString);

})

}

function toggleForm() {

$("#toggleTodoForm").click(function() {

$("#todo-form").toggle();

})

}

function addTodo() {

var data = {

text: $('#todo_title').val(),

details:$('#todo_text').val()

}

$.post('http://localhost:8080/api/todos', data, function(result) {

var item = todoTemplate(result.text, result.details);

$('#todos').prepend(item);

$("#todo-form").slideUp();

})

}

$(document).ready(function() {

toggleForm();

getTodos();

$('#addTodo').click(addTodo);

})

</script>

</body>

</html>This file is very similar to our frontend code for our to-do app, but we are going to host it elsewhere. Bear in mind that the $.post() endpoint is now pointing to http://localhost:8080/api/todos.

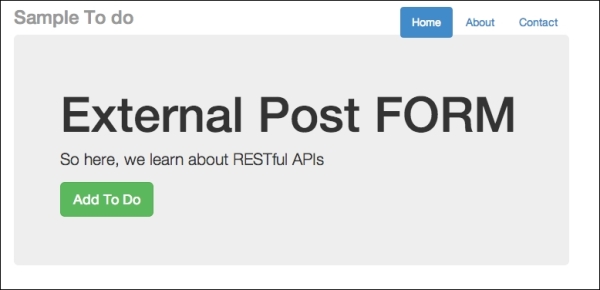

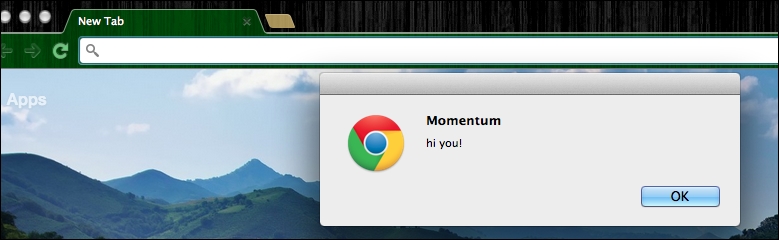

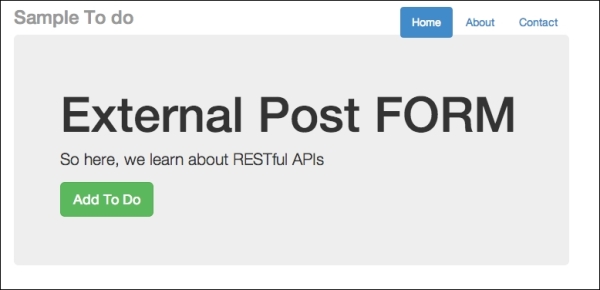

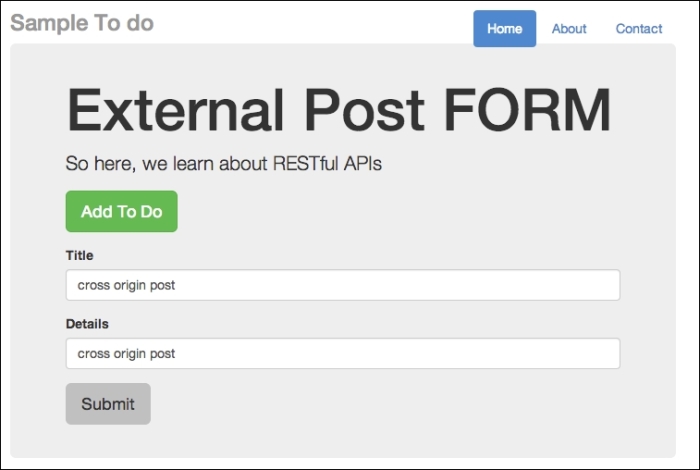

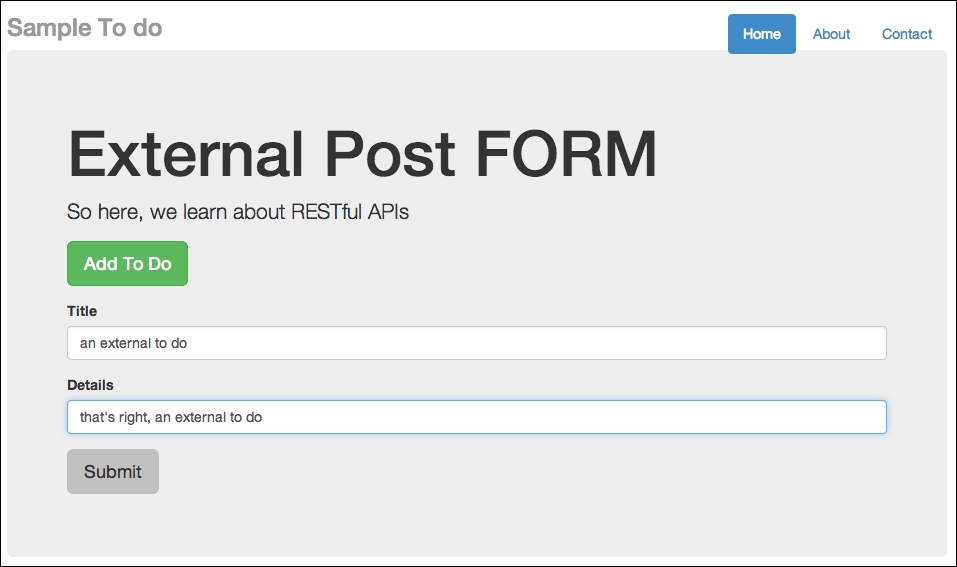

Next, I want you to host the file in another domain in your own localhost. Since we are using http://localhost:8080 for our Node.js server, you can try other ports. In my case, I'll serve external_node.html at http://localhost:8888/external_node.html. Open external_node.html on another port, and you should see the following:

External post form for cross-domain injection

You can open the external_node.html file by starting another instance of Node.js on another port, or you can simply place external_node.html on a local web server, such as Apache. If you are a Windows user, you can use http://www.wampserver.com/en/. If you are a Mac user, you can try using MAMP: http://www.mamp.info/en/.

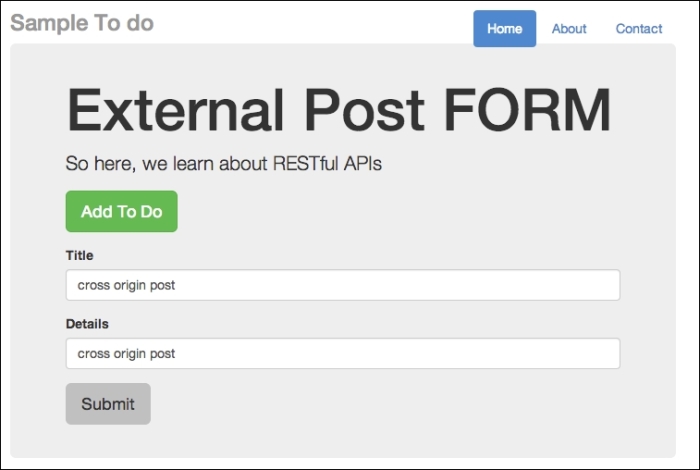

As usual, click on the Add To Do button, and add in some text. Here's what I did:

External post form for cross-domain injection

Now, click on Submit. There are no animations in this form. Go back to http://localhost:8080/api and refresh it. You should see the to-do item displayed at the bottom of your to-do list, as follows:

Item posted from another domain. This is dangerous!

Since I have quite a few to-do items, I need to scroll all the way down. But the key thing is to see that without any security precautions, any external-facing APIs can be easily accessed and new content can be posted without your permission. This can cause huge problems for you, as attackers can choose not to play by your rules and inject something sneaky, such as a malicious JavaScript.

What makes a cross-origin post effective is that the attacker uses the end user's logged-in status to gain access to parts of an API on the target site that are behind a login wall.

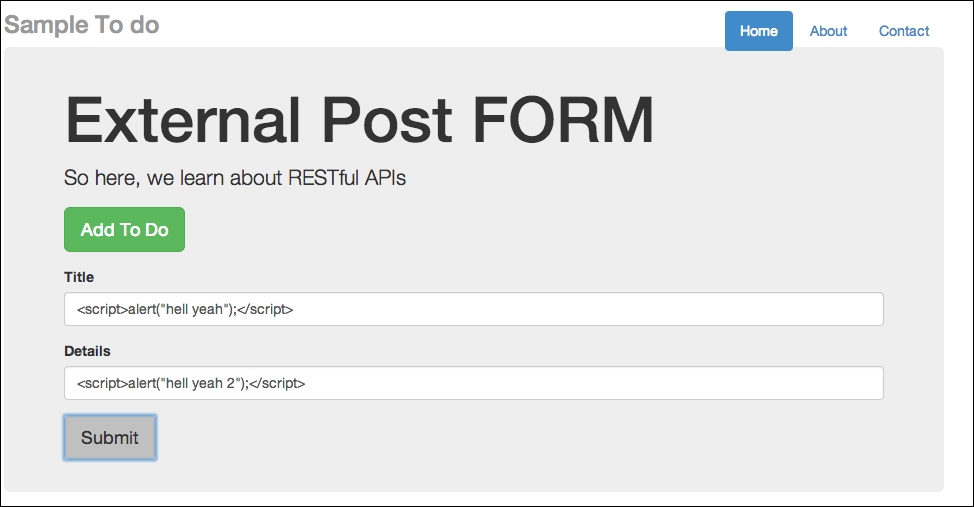

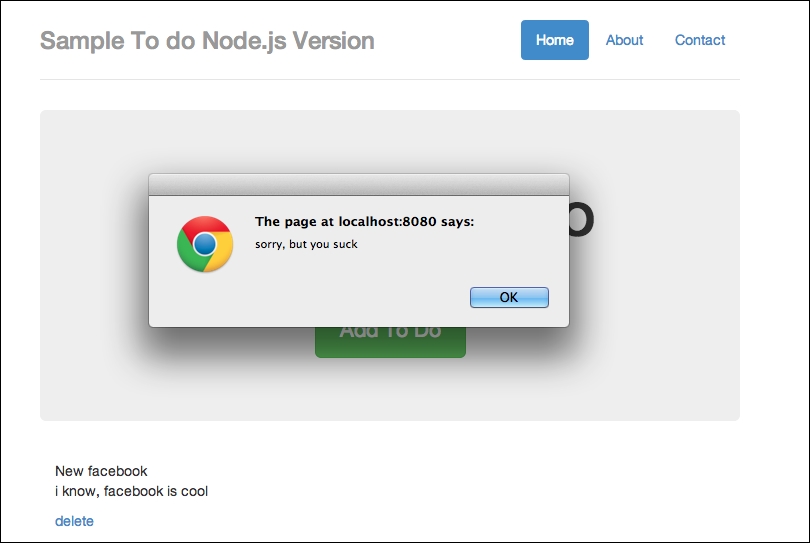

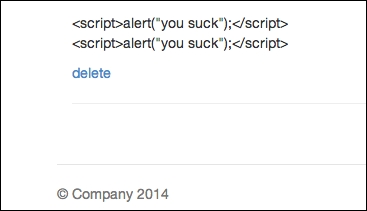

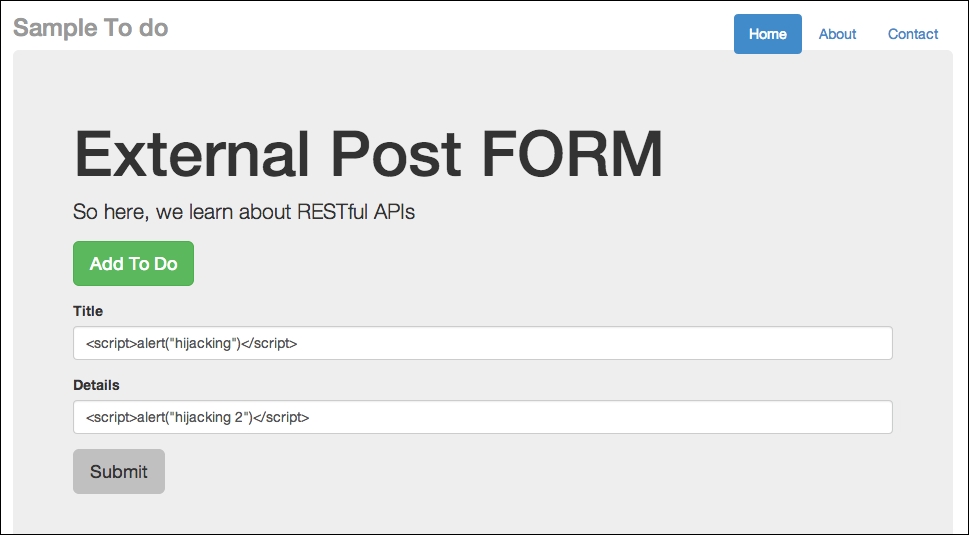

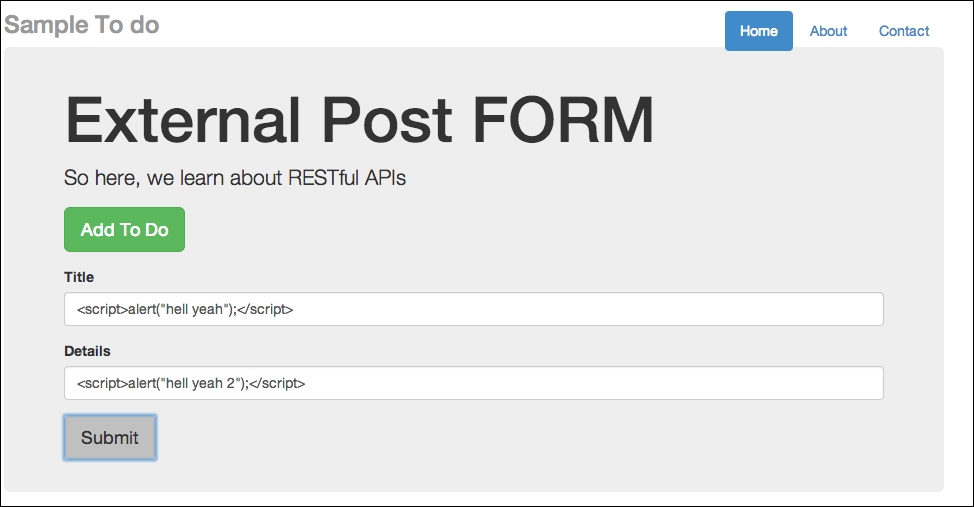

So now, let's try to inject some JavaScript code via our external form. Going back to external_node.html, try typing in some code. Have a look at the following screenshot:

External post form for cross-domain injection using JavaScript

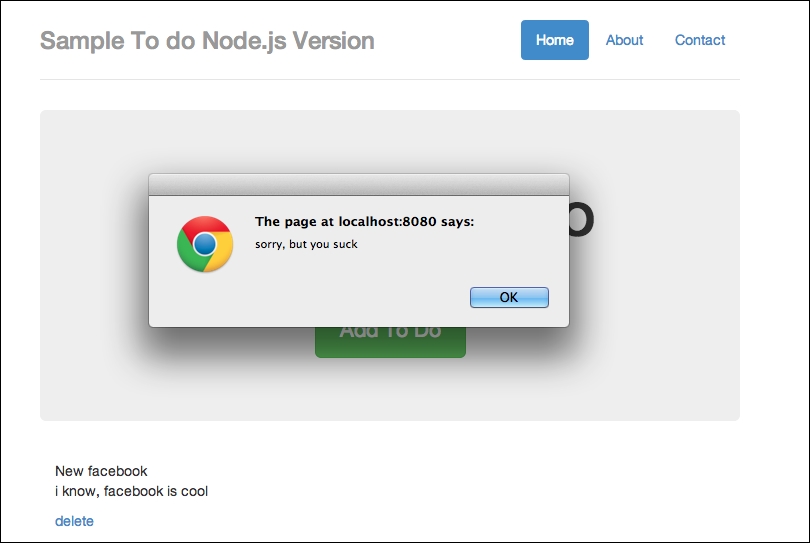

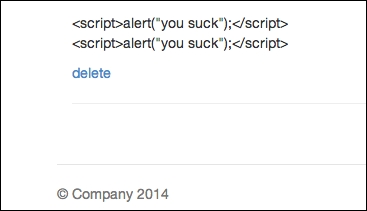

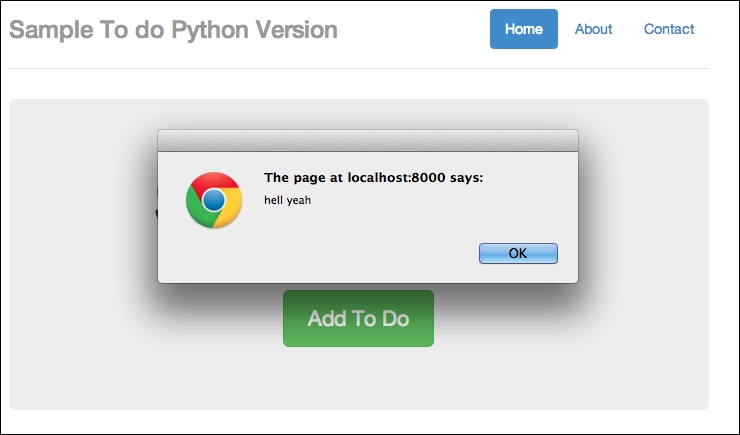

So, I intend to inject alert("sorry, but you suck"). Once submitted, go back to your to-do list app and refresh it. You should see the message shown in the following screenshot:

Injection successful, but this is bad for security

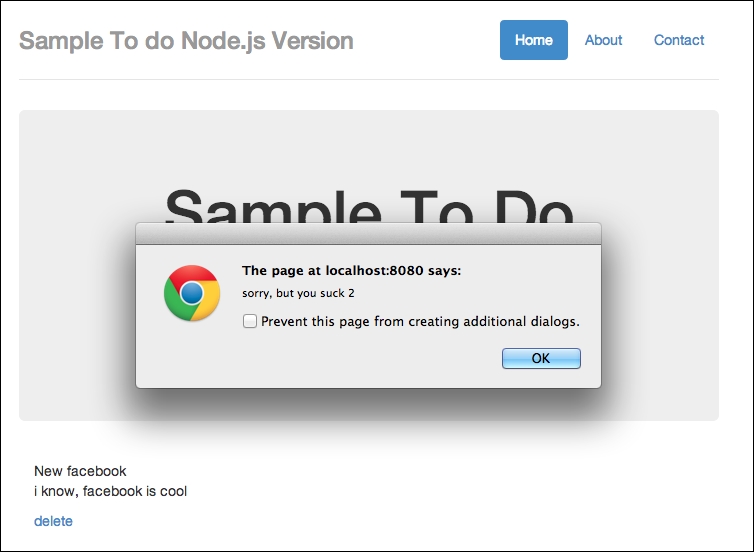

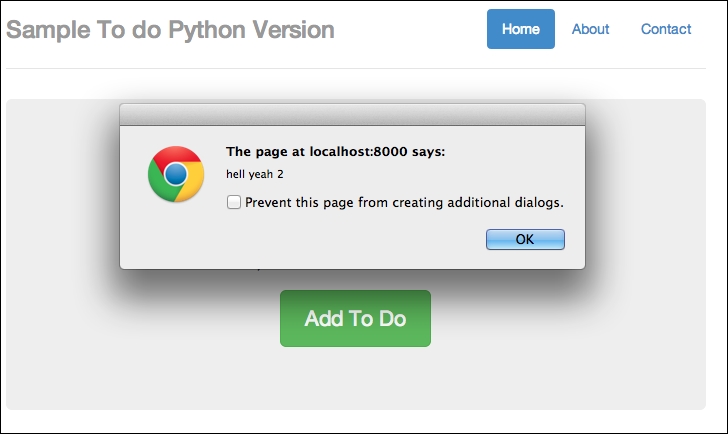

Next, you'll see the following screen:

Injection success part 2. Bad security.

Effectively, we've just injected malicious code. We could have injected other stuff, such as links to weird sites and so on, but you get the idea.

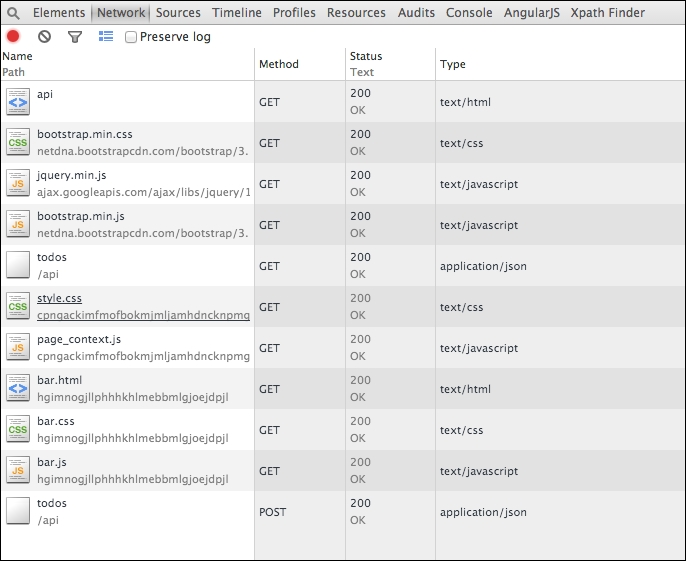

You might think that the preceding result cannot be achieved easily; how can an attacker know which endpoints to POST to? This can be done fairly easily. For instance, you can make use of Google Chrome Developer Tools and observe endpoints being used.

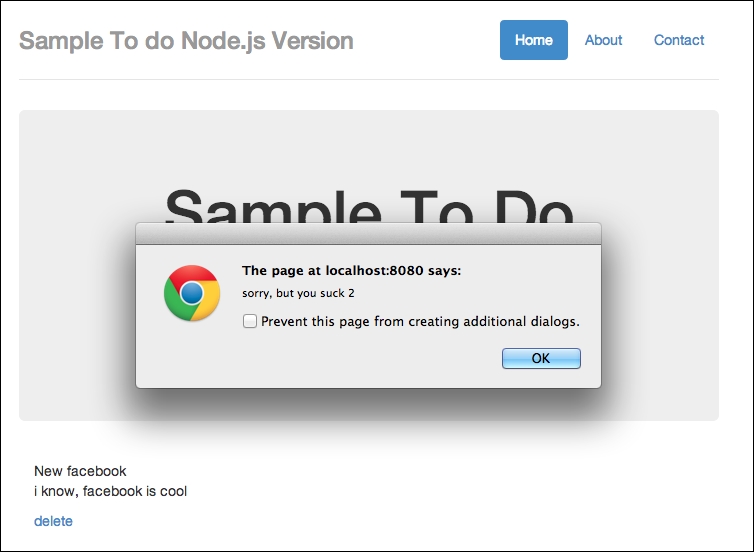

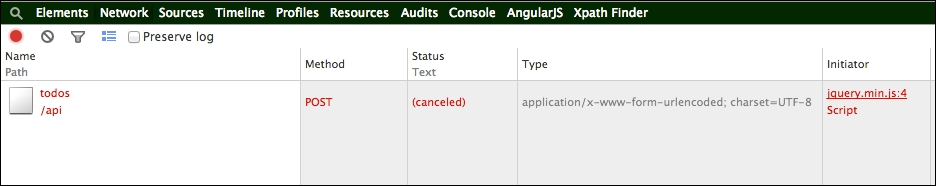

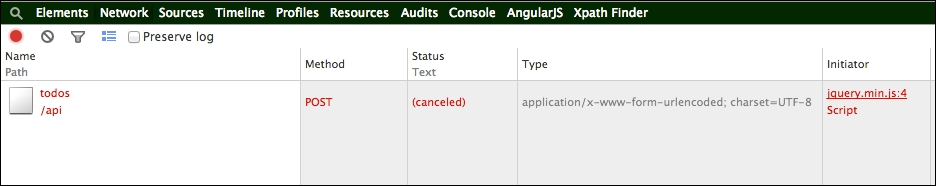

Let's try this out: go back to http://localhost:8080/api and open your Chrome Developer Tools (assuming you are using Google Chrome). Once you open the Developer Tools, click on Network. Refresh your to-do app. And finally, make a post. This is what you should see:

Observing URL endpoints made by code

You should notice that we have made a few GET api calls and the final POST call to our endpoint. The final POST call, todos, followed by /api means that we are posting to /api/todos.

If we are the attacker, the final step would be to derive the required parameters for the posting to go through; this should be easy as well since we can simply observe our source code to check for the parameter's name.

First and foremost, we need to prevent cross-origin posting of form values unless we are absolutely sure that we have a way to control (or at least know who can do it) the POST. For a start, we can prevent cross-origin posting without permissions.

For instance, here's what we can do to prevent cross-origin posting: we first need to install cookie-session (https://github.com/expressjs/cookie-session) and CSRF (https://github.com/expressjs/csurf) and then apply them in our server.js file.

To install CSRF, simply run the command npm install –g csrf.

The settings of our server.js file now look like this:

var express = require('express');

var bodyParser = require('body-parser');

var app = express();

var session = require('cookie-session');

var csrf = require('csrf');

app.use(csrf());

app.use(bodyParser());

var port = process.env.PORT || 8080; // set our port

var mongoose = require('mongoose');

mongoose.connect('mongodb://127.0.0.1/todos'); // connect to our database

var Todos = require('./app/models/todo');

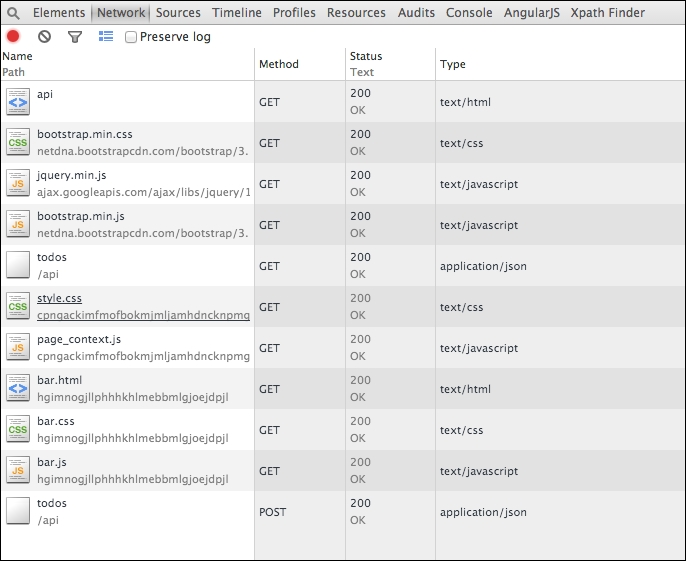

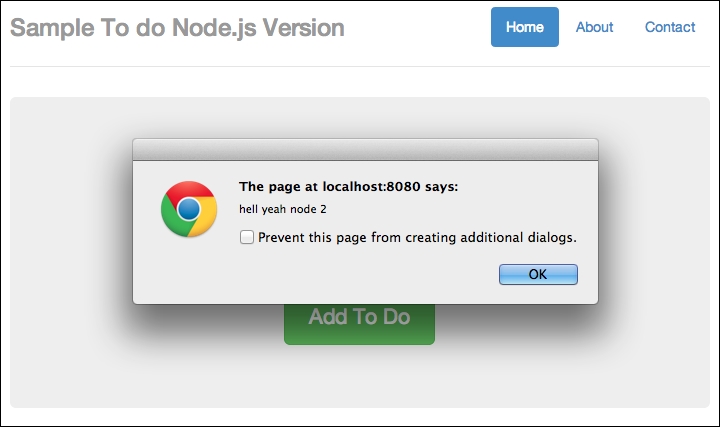

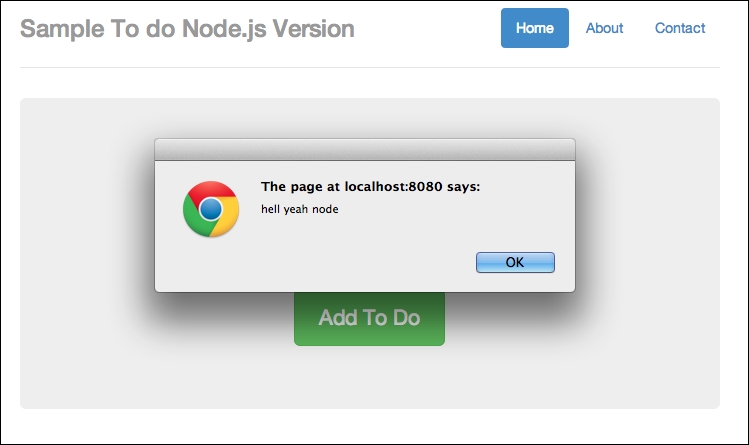

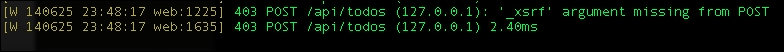

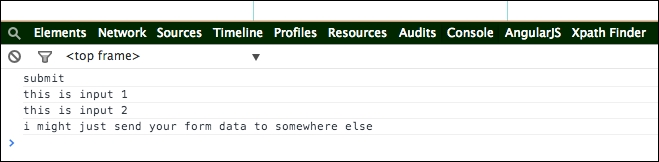

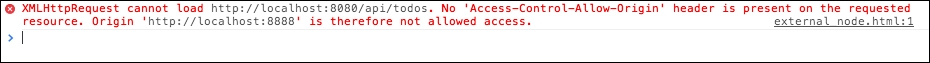

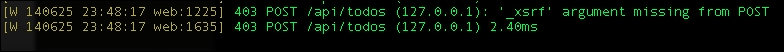

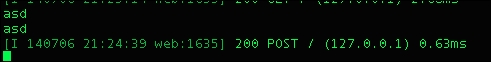

var router = express.Router();Now, restart your server and try to POST from external_node.html. You should most likely receive an error message to the effect that you cannot POST from a different domain. For instance, this is the error you will see from your console if you are using Google Chrome:

External post form now fails after we set up our server.js with basic security measures

The next technique is to escape user input first so that malicious input, such as the alert() function, cannot be executed. Here's what we can do: we first write this new JavaScript function:

function htmlEntities(str) {

return String(str).replace(/&/g, '&').replace(/</g, '<').replace(/>/g, '>').replace(/"/g, '"');

}Now, prepend it at the start of our JavaScript code block. Then, at our todoTemplate(), we need to make the following changes:

function todoTemplate(title, body, id) {

var title = htmlEntities(title);

var body = htmlEntities(body);

var snippet = "<div id=\"todo_"+id+"\"" + "<h2>"+title+"</h2>"+"<p>"+body+"</p>";

var delete_button = "<a class='delete_item' href='#' id="+id+">delete</a></div><hr>";

snippet += delete_button;

return snippet;

}Take note of the highlighted lines of code, what we did here is to perform a conversion of HTML entities such as the JavaScript code snippet. This function is inspired by PHP's htmlentities() (http://php.net/manual/en/function.htmlentities.php).

There's a useful Node.js module called secure-filters that does exactly the same thing, if not better. Visit them at https://www.npmjs.org/package/secure-filters.

Now save your file and refresh your browser again. You will notice that you no longer receive the alert() boxes and that the JavaScript code is printed out as if it's a string:

JavaScript now being printed as a string

To summarize, we learned how to create a simple RESTful server using Express.js and Node.js. At the same time, we have seen how to effectively inject malicious JavaScript using very simple observation techniques. This chapter also demonstrates cross-origin requests that expose a CSRF vulnerability. Most importantly, you might have noticed that security loopholes are typically a combination of both frontend and server-side loopholes: both hands need to clap in order for security issues to occur.

Welcome back! In this chapter, we will take a closer look at one of the most common JavaScript security attacks: cross-site scripting.

Cross-site scripting is a type of attack where the attacker injects code (basically, things such as client-side scripting, which in our case is JavaScript) into the remote server.

If you remember, we did something similar in the previous chapter: we posted something that says alert(), which unfortunately gets saved into our database. When our screen refreshes, the alert gets fired off. This alert() function gets fired off whenever we hit that page.

There are basically two types of cross-site scripting: persistent and nonpersistent.

Persistent cross-site scripting happens when the code injected by the attacker gets stored in a secondary storage, such as a database. As you have already seen in Chapter 2, Secure Ajax RESTful APIs, the testing of security flaws that we performed is a form of persistent cross-site scripting, where our injected alert() function gets stored in MongoDB.

Nonpersistent cross-site scripting requires an unsuspecting user to visit a crafted link made by the attacker; as you may have guessed, if the unsuspecting user visits the specially crafted link, the code will be executed by the user's browser.

For the purposes of this chapter, the exact terminologies of persistent versus nonpersistent cross-site scripting does not matter that much, because both work in a somewhat similar manner in real-world situations. What we will do is provide a series of examples for you to get the hang of the various JavaScript security issues.

In the previous chapter, we built a Node.js/Express.js-based backend and attempted successfully to inject a simple JavaScript function, alert(), into the app. So, you may be thinking, does such a security flaw occur in a backend based on JavaScript?

The answer is no. The error can occur in systems based on different programming/scripting languages. In this section, we'll start with a RESTful backend based on Python and demonstrate how we can perform different types of cross-site scripting.

The app here is similar to what we built in Chapter 2, Secure Ajax RESTful APIs; we are going to build a simple RESTful to-do app, but now the difference is that the backend is based on Python/Tornado.

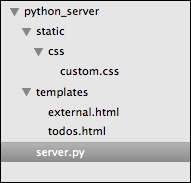

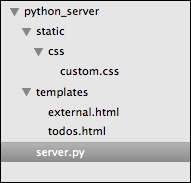

Your code will look like the following by the end of this section:

Code organization by the end of this chapter

Therefore, you might want to start by creating the required folders and files before moving to the next subsection. The folders that you need to create include python_server, and within python_server, you need to create static/ and templates/. Within static/, you need to create css/.

Assuming you have created the required files and folders, we will start with server.py.

In this section, we will write some code that duplicates what our Express.js/Node.js backend did in the previous chapter. In this chapter, we are going to use Python (https://www.python.org/) and the Tornado web framework (http://www.tornadoweb.org/en/stable/). You will need to make sure that you have Python and the Tornado web framework installed.

To install Python (we are using Version 2.7.5 for the code examples, by the way), you can visit https://www.python.org/ and check out the installation instructions. Once that is done, you will need to install the common Python development tools, such as Python setuptools (https://pypi.python.org/pypi/setuptools).

Next, you will need to install the Tornado web framework, PyMongo, and Tornado CORS. Issue the following commands:

sudo pip install tornado==3.1 sudo pip install pymongo sudo pip install tornado-cors

Now, we can start to code. As a reminder, the code in this chapter is found in this chapter's code sample folder under the python_server folder.

We will first kick off proceedings by importing and defining the important stuff, as follows:

import tornado.httpserver

import tornado.ioloop

import tornado.options

import tornado.web

import pymongo

from bson.objectid import ObjectId

from tornado_cors import CorsMixin

from tornado.options import define, options

import json

import os

define("port", default=8080, help="run on the given port", type=int)You will need to install Python for this section. While Python is now at Version 3.4.x, I'll use Python 2.7.x for this section. You can download Python from https://www.python.org/download. You will also need to install PyMongo (http://api.mongodb.org/python/current/) and

tornado_cors (https://github.com/globocom/tornado-cors).

In the preceding code, we imported the libraries we will need and defined 8080 for the port at which this server will run.

Next, we need to define the URLs and other common settings. This is done via the Application class, which is discussed as follows:

class Application(tornado.web.Application):

def __init__(self):

handlers = [

(r"/api/todos", Todos),

(r"/todo", TodoApp)

]

conn = pymongo.Connection("localhost")

self.db = conn["todos"]

settings = dict(

xsrf_cookies=False,

debug=True,

template_path=os.path.join(os.path.dirname(__file__), "templates"),

static_path=os.path.join(os.path.dirname(__file__), "static")

)

tornado.web.Application.__init__(self, handlers, **settings)What we did here is we defined two URLs, /api/todos and /todo, which do exactly the same thing as per what we did in Chapter 2, Secure Ajax RESTful APIs. Next, we need to code the required classes that provide the meat of the functionalities.

We will code the TodoApp class and the Todos class as follows:

class TodoApp(tornado.web.RequestHandler):

def get(self):

self.render("todos.html")

class Todos(tornado.web.RequestHandler):

def get(self):

Todos = self.application.db.todos

todo_id = self.get_argument("id", None)

if todo_id:

todo = Todos.find_one({"_id": ObjectId(todo_id)})

todo["_id"] = str(todo['_id'])

self.write(todo)

else:

todos = Todos.find()

result = []

data = {}

for todo in todos:

todo["_id"] = str(todo['_id'])

result.append(todo)

data['todos'] = result

self.write(data)

def post(self):

Todos = self.application.db.todos

todo_id = self.get_argument("id", None)

if todo_id:

# perform a delete for example purposes

todo = {}

print "deleting"

Todos.remove({"_id": ObjectId(todo_id)})

# cos _id is not JSON serializable.

todo["_id"] = todo_id

self.write(todo)

else:

todo = {

'text': self.get_argument('text'),

'details': self.get_argument('details')

}

a = Todos.insert(todo)

todo['_id'] = str(a)

self.write(todo)

Todoapp simply renders the todos.html file, which contains the frontend of the to-do list app. Next, the Todos class contains two HTTP methods: GET and POST. The GET method simply allows our app to retrieve one to-do item or the entire list of to-do items, while POST allows the app to either add a new to-do item or delete a to-do item.

Finally, we will initialize the app with the following piece of code:

def main():

tornado.options.parse_command_line()

http_server = tornado.httpserver.HTTPServer(Application())

http_server.listen(options.port)

tornado.ioloop.IOLoop.instance().start()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()Now, we need to code the todos.html file; the good news is that we already coded this in the previous chapter. You can copy-and-paste the code or refer to the source code for this chapter. Similarly, the custom.css and external.html files are the same as Chapter 2, Secure Ajax RESTful APIs.

You can now start the app by issuing the following command on your terminal:

python server.py

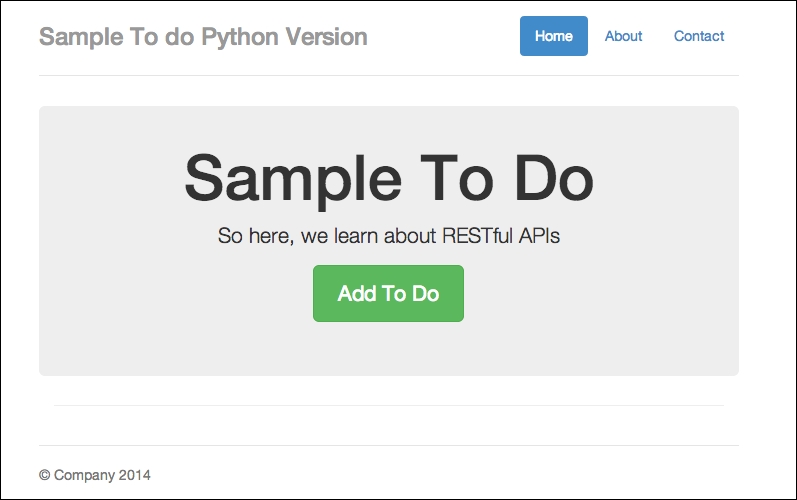

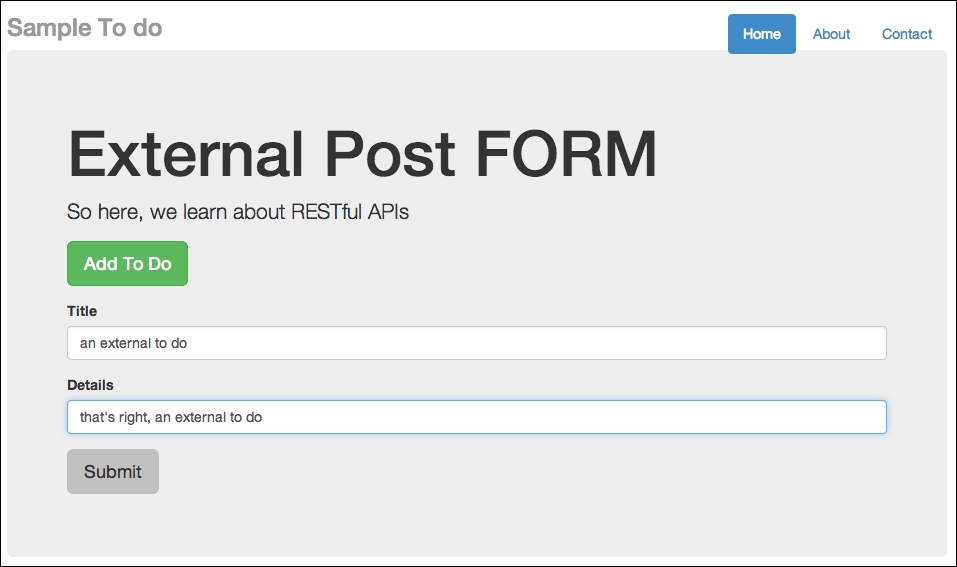

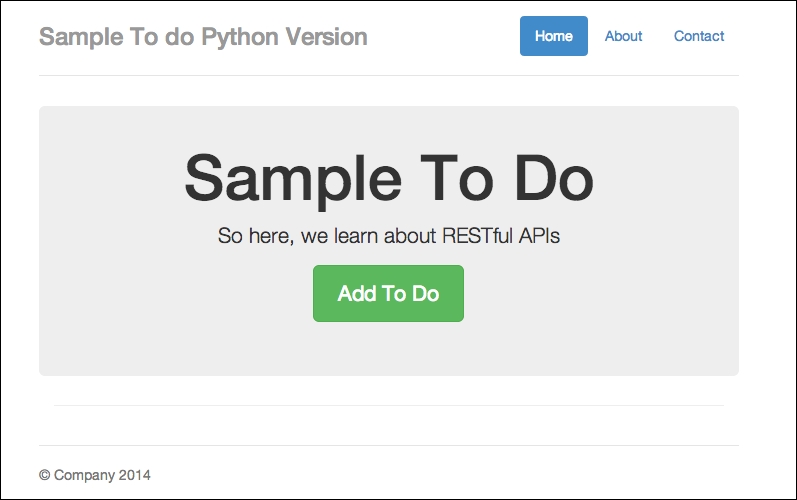

Once the app has started, navigate to your browser on http://localhost:8080/todo, and you should see the following:

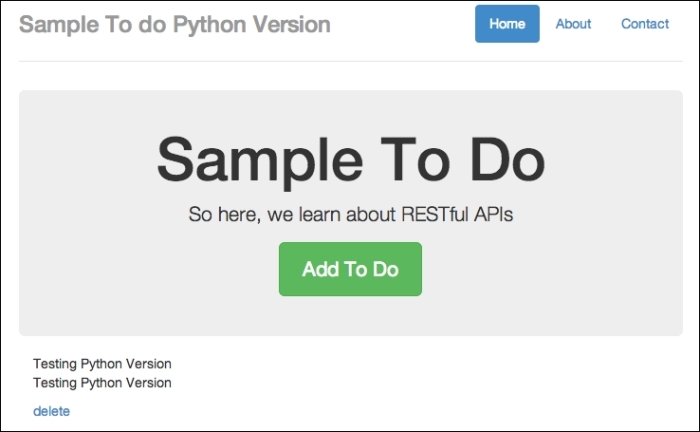

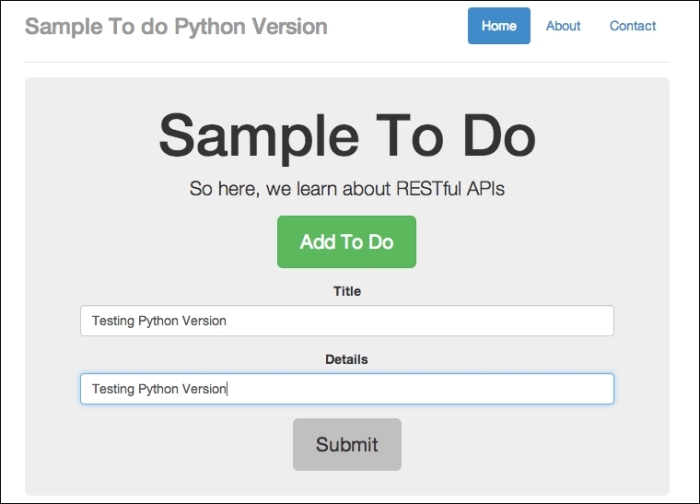

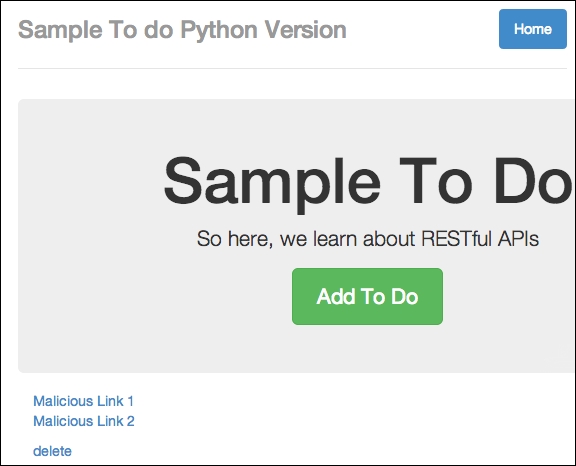

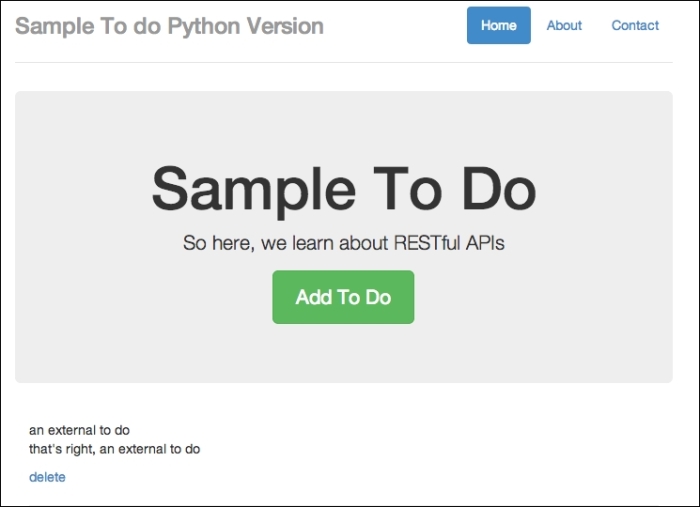

Our to-do app in Python/Tornado

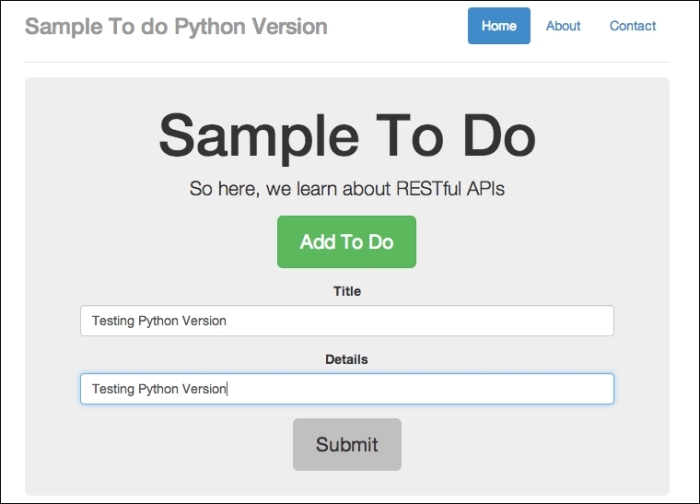

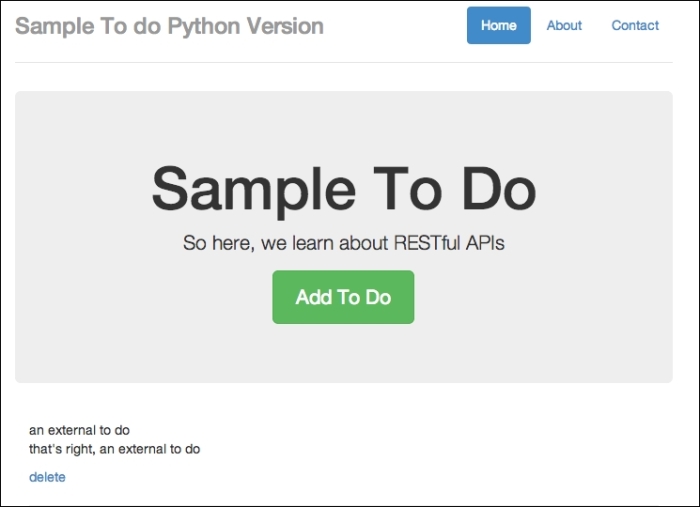

The app looks approximately the same as what we had in Chapter 2, Secure Ajax RESTful APIs. Now you can try out the app by clicking on the Add To Do button and type in some details, as shown in the following screenshot:

Adding in a new to-do item

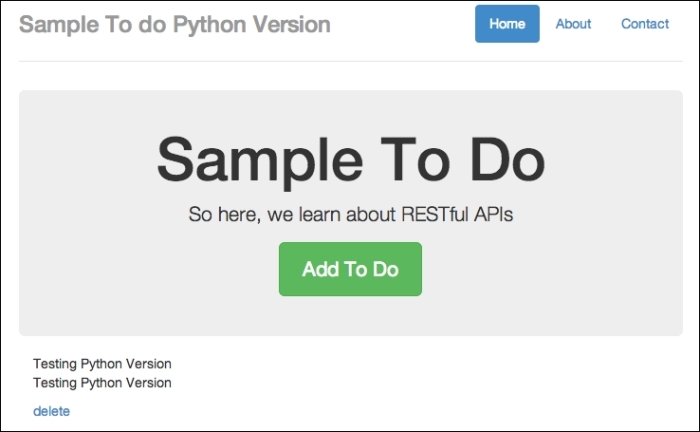

When you click on the Submit button, you will see something similar to the following screenshot:

A to-do item successfully added

You should see the new to-do item showing on the screen after clicking on Submit. Now that we have confirmed that the app is working, let's attempt to perform cross-site scripting.

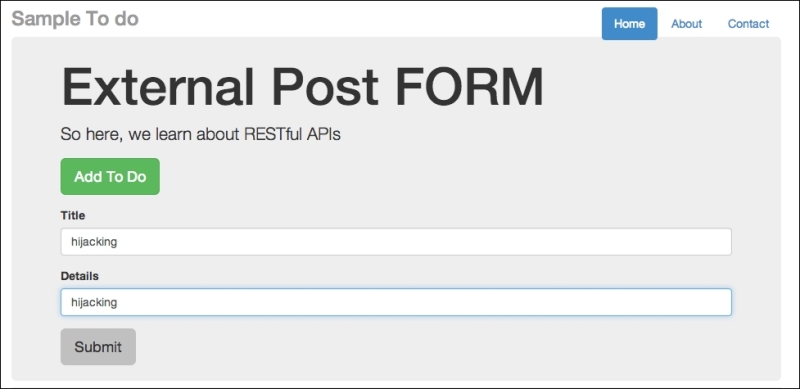

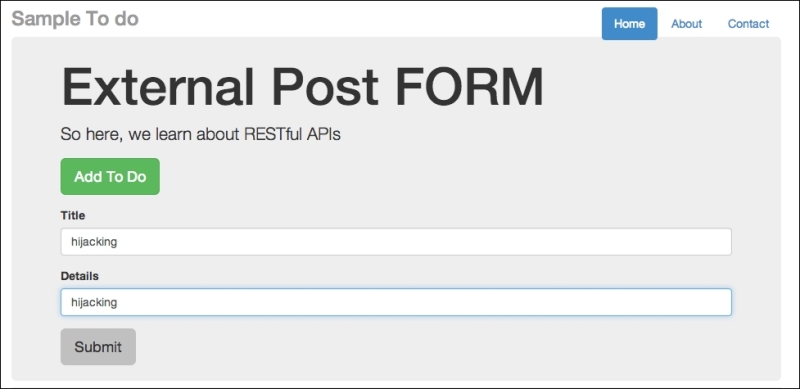

Now, let's try to perform a basic cross-site scripting example:

external_node.html from the previous chapter (Chapter 2, Secure Ajax RESTful APIs) in a new web server under a different port (such as port 8888), and type in some basic text, as shown in the following screenshot:

An external post form to post externally

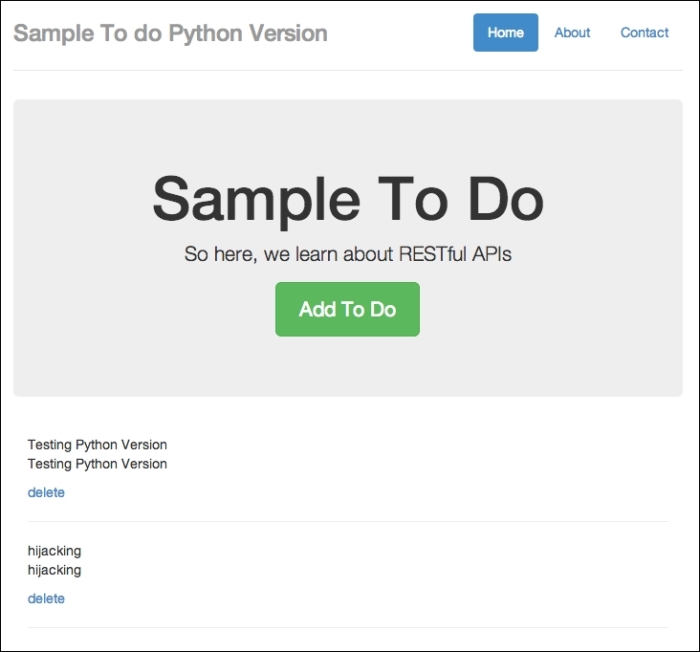

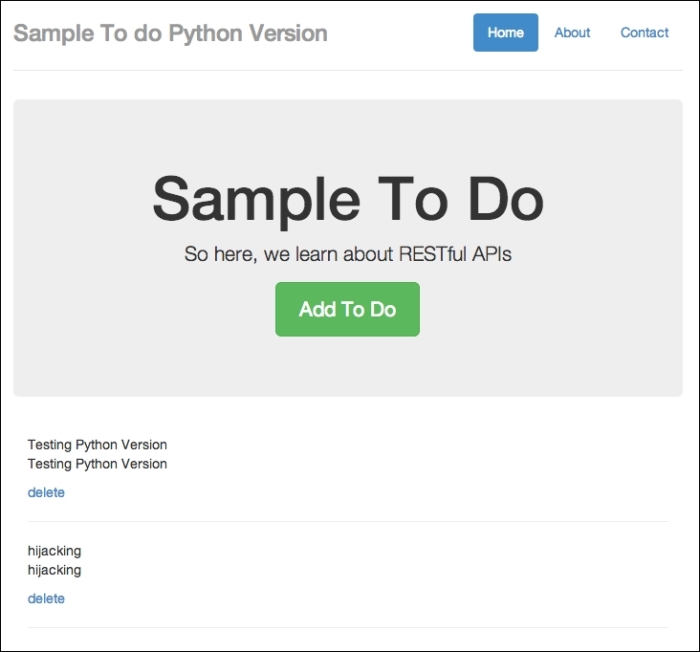

http://localhost:8080/todo and refresh the browser. You should see the text being injected in to the web page, as follows:

A to-do item added from somewhere else

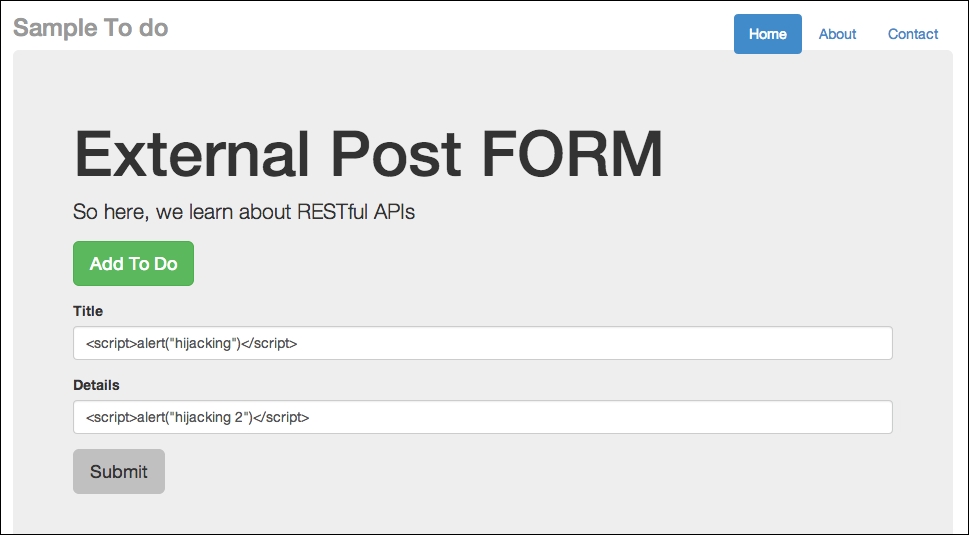

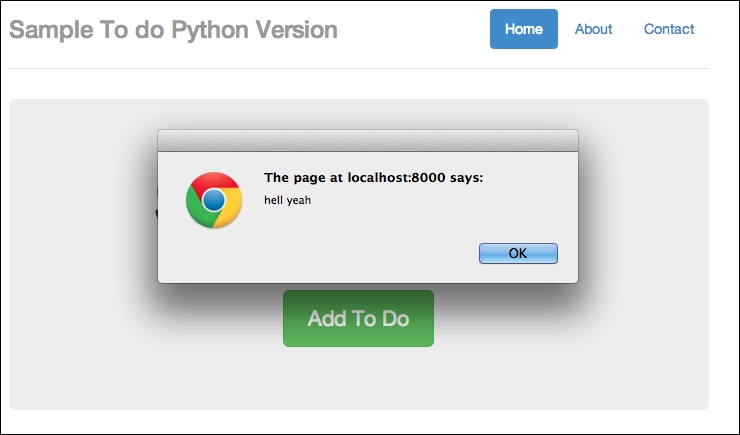

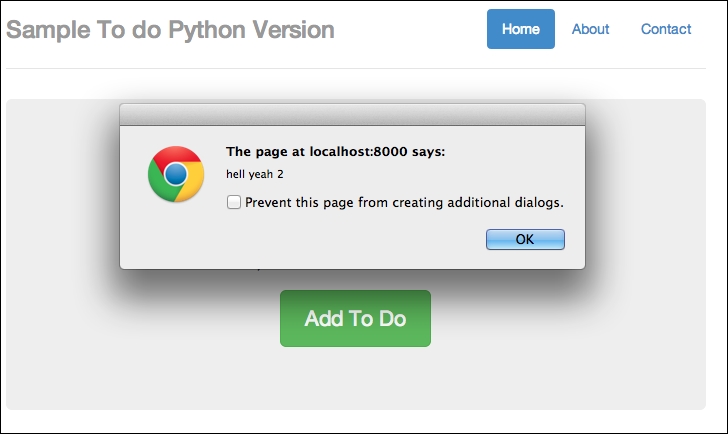

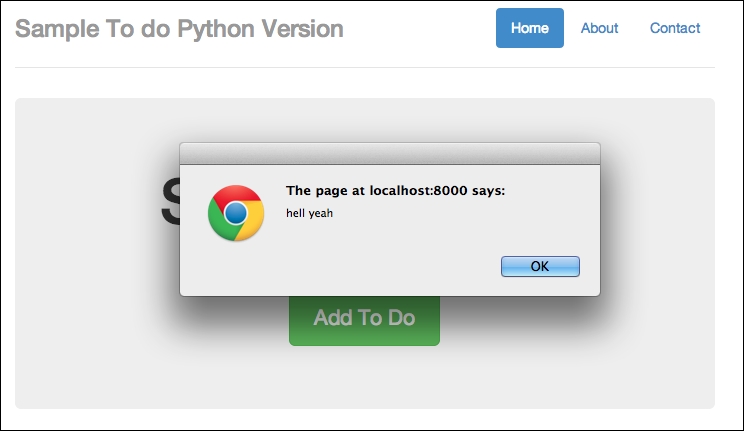

Posting JavaScript functions

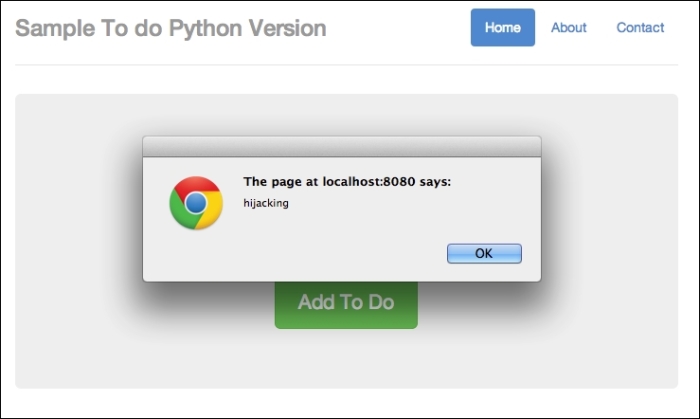

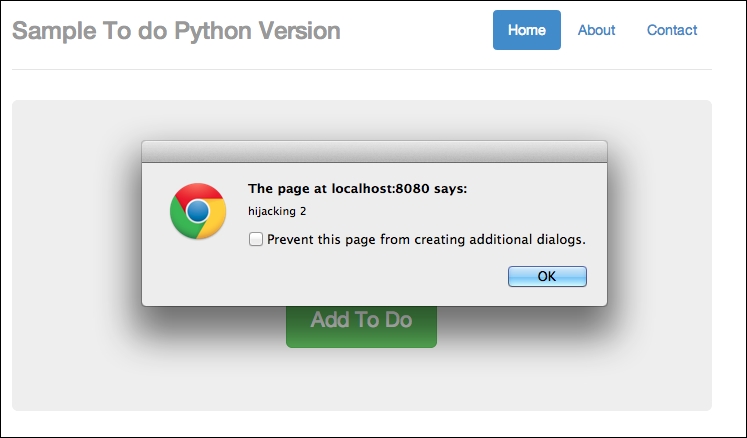

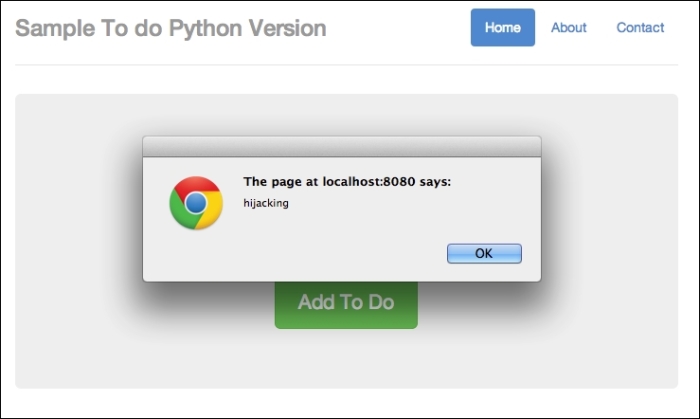

As usual, click on Submit and refresh the app at http://localhost:8080/todo. You will see two alert boxes. Here's how the first box looks:

Hijacked part 1

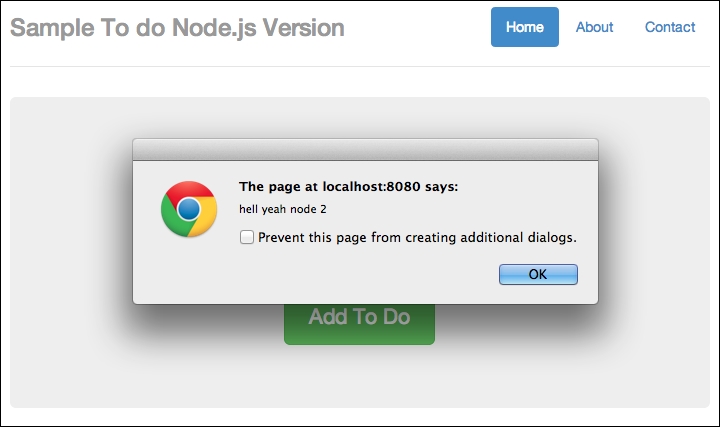

The second hijacked part looks like this:

Hijacked part 2

So once again, we are hijacked!

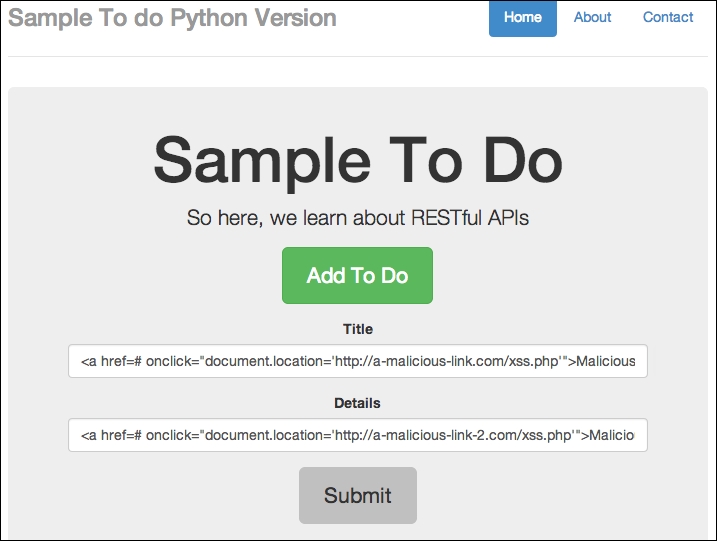

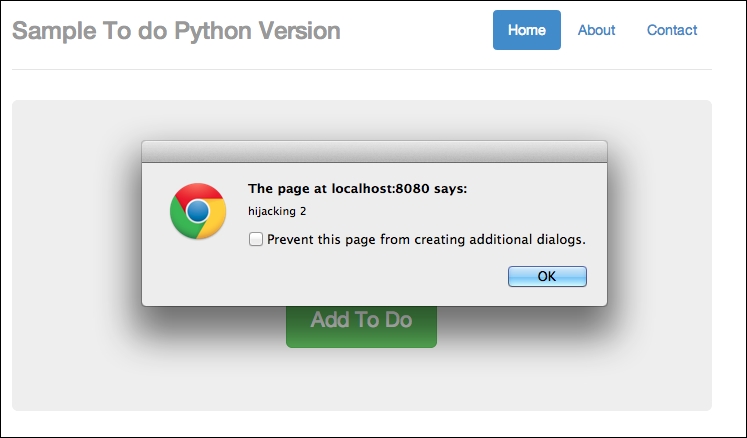

Now we can try to trick end users into clicking through a malicious link. Take an instance where we enter the following line on http://localhost:8080/todo:

<a href=# onclick="document.location='http://a-malicious-link.com/xss.php'">Malicious Link 1</a>

You can also enter <a href=# onclick="document.location='http://a-malicious-link-2.com/xss.php'">Malicious Link 2</a> for the details:

Adding malicious code in the app itself

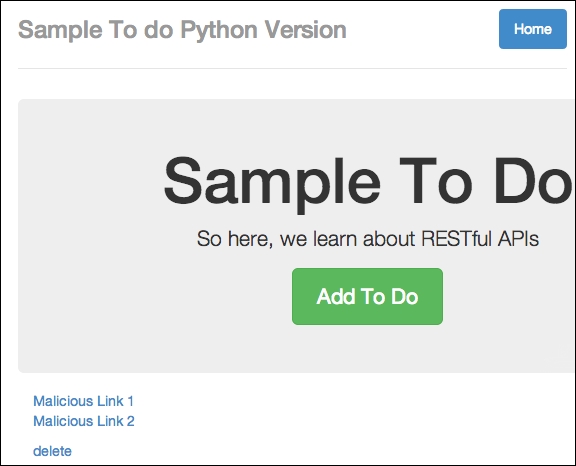

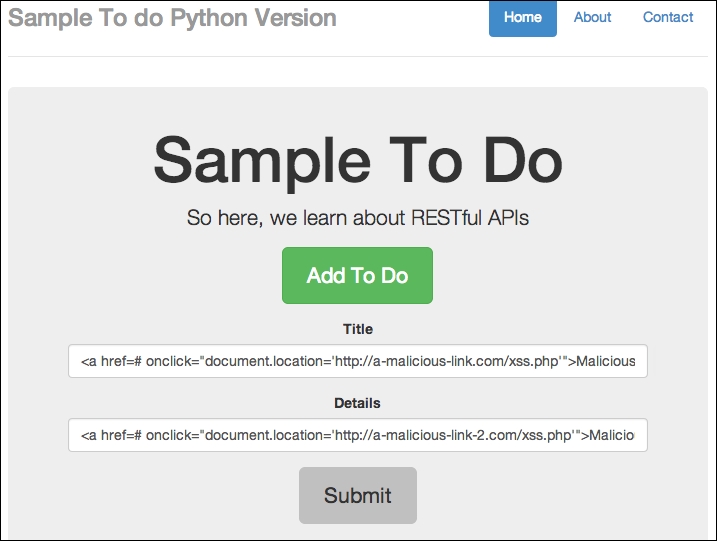

Now click on Submit, and you should see the new item as follows:

Malicious code added successfully

Now, imagine that these links are malicious and are public to other users. Now, you can try to click on the link; you will find that you are being directed to the malicious link. This is because the to-do item that we entered contains malicious JavaScript that redirects a user to a website. You can perform Inspect Element, as follows:

You can perform this action by right-clicking on your browser window

The resulting HTML page that our input produces is as follows:

The code generates a malicious link

You will notice that onclick will lead to a new URL other than our app; imagine this link is really malicious and leads to phishing sites, and so on.

At this point in time, you should notice that our app contains various security issues that allow for persistent cross-site scripting attacks. So, how do we prevent this from happening? We'll cover this and more after we talk briefly about our nonpersistent cross-site scripting example.

We will cover a basic nonpersistent scripting example in this section. Earlier on in this book, we discussed that nonpersistent cross-site scripting occurs where an unsuspecting user clicks on maliciously crafted URLs.

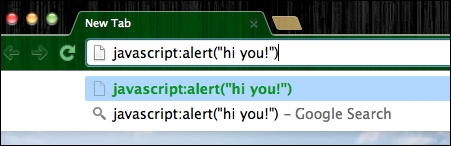

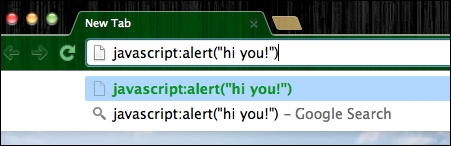

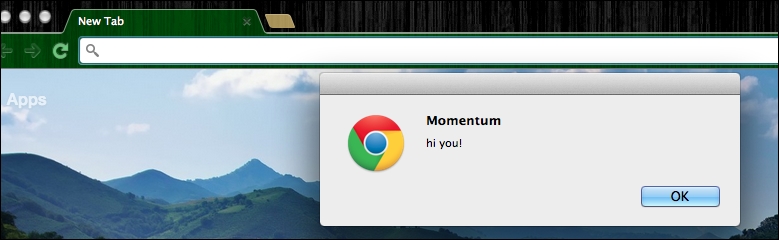

To briefly understand what this means, open your favorite browser and try to type the following into the URL address bar: javascript:alert("hi you!").

In my case, I'm using the Google Chrome browser, and I typed in the aforementioned code in the following screenshot:

Executing JavaScript in the URL address bar

Now hit Enter, and you should get something like the following screenshot :

JavaScript executed successfully

That's right; the browser URL address bar is capable of executing JavaScript functions.

So now, we can imagine that the original URLs in our apps may be appended with malicious JavaScript functions; consider the following code for instance:

<a href="http://localhost:8080/todo?javascript:window.onload=function(){var link=document.getElementsByTagName('a');link[0].href='http://malicious-website.com/';}">This is an alert</a>This code snippet assumes that our to-do app is hosted on http://localhost:8080/todo. Most importantly, notice that we are changing the URL of the links found on the to-do app, pointing to malicious-website.com.

If an unsuspecting user were to visit our to-do list app via the preceding link, the user will notice that he or she is redirected to malicious-website.com instead of just deleting the to-do items or visiting other parts of the website.

We will go through the basic techniques of defending against cross-site scripting. This is by no means a comprehensive list of defenses against cross-site scripting, but it should be enough to get you started.

We can parse the user's input using various techniques. Since we are talking about JavaScript in this book, we can apply the following JavaScript function to prevent the execution of malicious code:

function htmlEntities(str) {

return String(str).replace(/&/g, '&').replace(/</g, '<').replace(/>/g, '>').replace(/"/g, '"');

}This function effectively strips the malicious code from the user's input and output as normal strings. To see this function in action, simply refer to the source code for this chapter. You can find this function in use at python_server/templates/todos_secure.html. For ease of reference, the code snippet is being applied here as follows:

function htmlEntities(str) {

return String(str).replace(/&/g, '&').replace(/</g, '<').replace(/>/g, '>').replace(/"/g, '"');

}

function todoTemplate(title, body, id) {

var title = htmlEntities(title);

var body = htmlEntities(body);

var snippet = "<div id=\"todo_"+id+"\"" + "<"<h2>"+title+"</h2>"+"<p>"+body+"</p>";

var delete_button = "<a class='delete_item' href='#' id="+id+">+">delete</a></div><hr>";

snippet += delete_button;

return snippet;

}Notice that the to-do item is first being escaped and returned as an HTML template for our app to insert into the browser screen.

There are times when some HTML tags are allowed to be used for users. Some libraries help us do this, such as Google Caja (http://developers.google.com/caja).

Another approach is to make use of auto-escape or similar utilities to escape the input first. For instance, instead of using Ajax to get the output, you can simply generate the output from the server side. In Tornado's case, you can make use of the autoescape function. You can learn more about it at http://tornado.readthedocs.org/en/latest/template.html.

There are other ways and forms of protection as well:

HTTP only flags in your cookies so that JavaScript won't be allowed to access them.To summarize, we learned that security issues can occur in any programming language; Python, JavaScript, and others can be laced with JavaScript security issues if we are not careful. We also showed that we need to be careful with the user input; escaping them is an important technique to prevent malicious JavaScript being executed.

In the next chapter, we will learn about the (almost exact) opposite of cross-site scripting: cross-site forgery.

In this chapter, we will cover cross-site forgery. This topic is not exactly new, and believe it or not, we have already encountered this in the previous chapters. In this chapter, we will go deeper into cross-site forgery and learn the various techniques of defending against it.

Cross-site request forgery (CSRF) exploits the trust that a site has in a user's browser. It is also defined as an attack that forces an end user to execute unwanted actions on a web application in which the user is currently authenticated. We have seen at least two instances where CSRF has happened. Let's review these security issues now.

We will now take a look at a basic CSRF example:

chp4/python_tornado. Run the following command:

python xss_version.py

external.html found in templates, in another host, say http://localhost:8888. You can do this by starting the server, which can be done by running python xss_version.py –port=8888, and then visiting http://loaclhost:8888/todo_external. You will see the following screenshot:

Adding a new to-do item

Adding a new to-do item and posting it

http://localhost:8000/todo and refreshing it, you will see the new to-do item added to the database, as shown in the following screenshot:

To-do item is added from an external app; this is dangerous!

Adding a new to do for the Python version

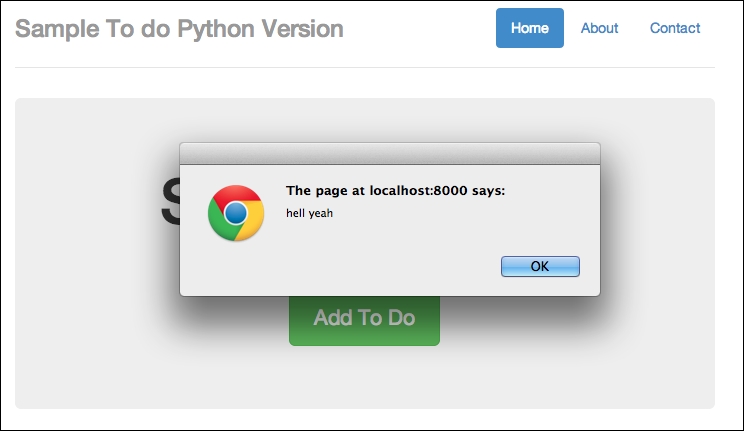

http://localhost:8000/todo, and you will see two subsequent alerts, as shown in the following screenshot:

Successfully injected JavaScript part 1

Successfully injected JavaScript part 2

Take note that this can happen to the other backend written in other languages as well. Now go to your terminal, turn off the Python server backend, and change the directory to node/. Start the node server by issuing this command:

node server.js

This time around, the server is running at http://localhost:8080, so remember to change the $.post() endpoint to http://localhost:8080 instead of http://localhost:8000 in external.html, as shown in the following code:

function addTodo() {

var data = {

text: $('#todo_title').val(),

details:$('#todo_text').val()

}

// $.post('http://localhost:8000/api/todos', data, function(result) {

$.post('http://localhost:8080/api/todos', data, function(result) {

var item = todoTemplate(result.text, result.details);

$('#todos').prepend(item);

$("#todo-form").slideUp();

})

}The line changed is found at addTodo(); the highlighted code is the correct endpoint for this section.

external.html, add a new to-do item containing JavaScript, as shown in the following screenshot:

Trying to inject JavaScript into a to-do app based on Node.js

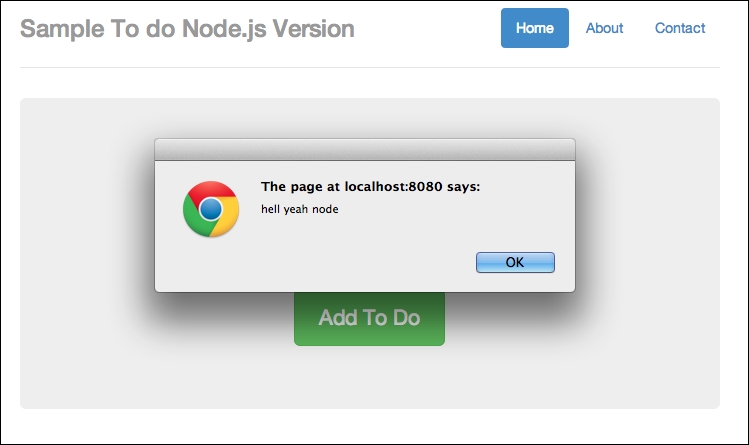

http://localhost:8080/api/ and refresh; you should see two alerts (or four alerts if you didn't delete the previous ones). The first alert is as follows:

Successfully injected JavaScript part 1

The second alert is as follows:

Successfully injected JavaScript part 1

Now that we have seen what can happen to our app if we suffered a CSRF attack, let's think about how such attacks can happen.

Basically, such attacks can happen when our API endpoints (or URLs accepting the requests) are not protected at all. Attackers can exploit such vulnerabilities by simply observing which endpoints are used and attempt to exploit them by performing a basic HTTP POST operation to it.

If you are using modern frameworks or packages, the good news is that you can easily protect against such attacks by turning on or making use of CSRF protection. For example, for server.py, you can turn on xsrf_cookie by setting it to True, as shown in the following code:

class Application(tornado.web.Application):

def __init__(self):

handlers = [

(r"/api/todos", Todos),

(r"/todo", TodoApp)

]

conn = pymongo.Connection("localhost")

self.db = conn["todos"]

settings = dict(

xsrf_cookies=True,

debug=True,

template_path=os.path.join(os.path.dirname(__file__), "templates"),

static_path=os.path.join(os.path.dirname(__file__), "static")

)

tornado.web.Application.__init__(self, handlers, **settings)Note the highlighted line, where we set xsrf_cookies=True.

For the version of the node server, you can refer to chp4/node/server_secure.js, where we require csrf. Have a look at the following code snippet:

var express = require('express');

var bodyParser = require('body-parser');

var app = express();

var session = require('cookie-session');

var csrf = require('csrf');

app.use(csrf());

app.use(bodyParser());The highlighted lines are the new lines (compared to server.js) to add in CSRF protection.

Now that both backends are equipped with CSRF protection, you can try to make the same post from external.html. You will not be able to make any post from external.html. For example, you can open Chrome's developer tool and go to Network. You will see the following:

POST forbidden

On the terminal, you will see a 403 error from our Python server, which is shown in the following screenshot:

POST forbidden from the server side

CSRF can also happen in many other ways. In this section, we'll cover the other basic examples on how CSRF can happen.

This is a classic example. Consider the following instance:

<img src=http://yousite.com/delete?id=2 />

Should you load a site that contains this img tag, chances are that a piece of data may get deleted unknowingly.

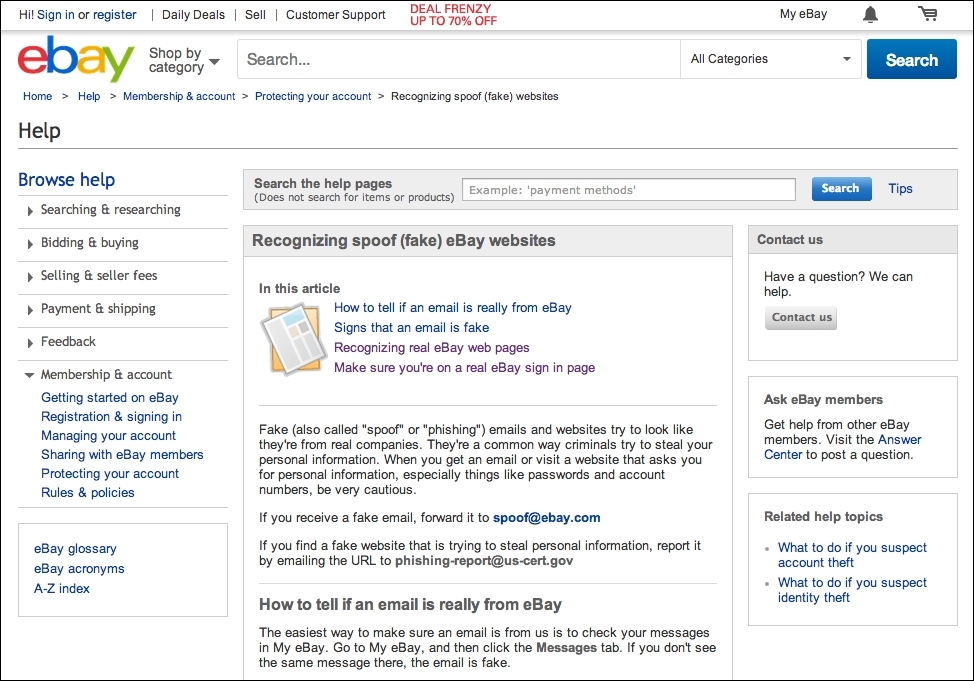

Now that we have covered the basics of preventing CSRF attacks through the use of CSRF tokens, the next question you may have is: what if there are times when you need to expose an API to an external app? For example, Facebook's Graph API, Twitter's API, and so on, allow external apps not only to read, but also write data to their system.

How do we prevent malicious attacks in this situation? We'll cover this and more in the next section.

Using CSRF tokens may be a convenient way to protect your app from CSRF attacks, but it can be a hassle at times. As mentioned in the previous section, what about the times when you need to expose an API to allow mobile access? Or, your app is growing so quickly that you want to accelerate that growth by creating a Graph API of your own.

How do you manage it then?

In this section, we will go quickly over the techniques for protection.

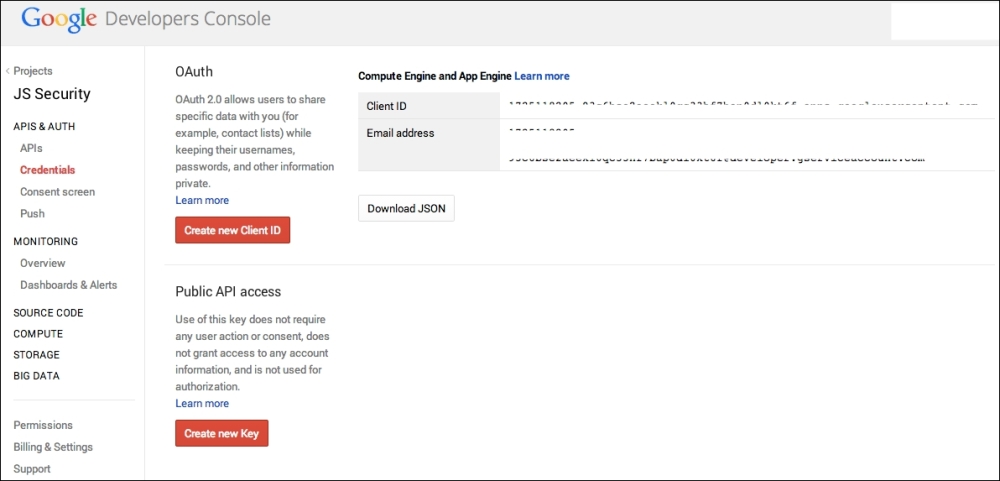

Creating your own app ID and app secret is similar to what the major Internet companies are doing right now: we require developers to sign up for developing accounts and to attach an application ID and secret key for each of the apps.

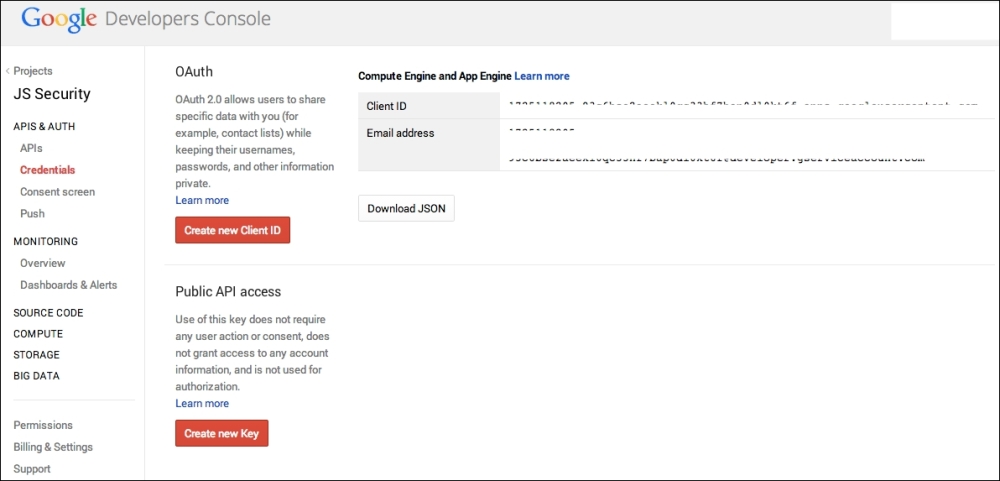

Using this information, the developers will need to exchange OAuth credentials in order to make any API calls, as shown in the following screenshot:

Google requires developers to sign up, and it assigns the client ID

On the server end, all you need to do is look for the application ID and secret key; if it is not present, simply reject the request. Have a look at the following screenshot:

The same thing with Facebook; Facebook requires you to sign up, and it assigns app ID and app secret

Simply put, you want to check where the request is coming from. This is a technique where you can check the Origin header.

The Origin header, in layman's terms, refers to where the request is coming from. There are at least two use cases for the usage of the Origin header, which are as follows:

Assuming that you are generating your own tokens, you may also want to limit the lifetime of the token, for instance, making the token valid for only a certain time period if the user is logged in to your site. Similarly, your site can make this a requirement in order for the requests to be made; if the token does not exist, HTTP requests cannot be made.

In this chapter, we covered the basic forms of CSRF attacks and how to defend against it. Note that these security loopholes can come from both the frontend and server side. In the next chapter, we will focus on misplaced trust in the client, which is a situation where developers are overly trusting and expect the code to work as they want in the browser, but for some reasons, it does not.

Misplaced trust in the client by itself is a very general and broad topic. However, believe it or not, we already covered some aspects of this topic in the previous chapters.

Misplaced trust in the client generally means that if we, as developers, are overly trusting, especially in terms of how our JavaScript will run in the client or if there is any input from the users, we might just set ourselves up for security flaws.

In short, we cannot simply assume that the JavaScript code will run as intended.

In general, while we try our best to write secure JavaScript code, we must recognize that the JavaScript code that we write will eventually be sent to a browser. With the existence of XSS/CSRF, code on the browser can be manipulated fairly easily, as you saw in the previous chapter.

We will start off with a simple application, where we attempt to create a user, similar to many of the apps we are familiar with, albeit a more simplified one.

We will walk through the creation of the app, use it, and then utilize it again under modified circumstances where the trust actually gets misplaced.

This example is based on Tornado/Python. You can easily recreate this example using Express.js/Node.js. The important things to note here are the issues happening on the client side.

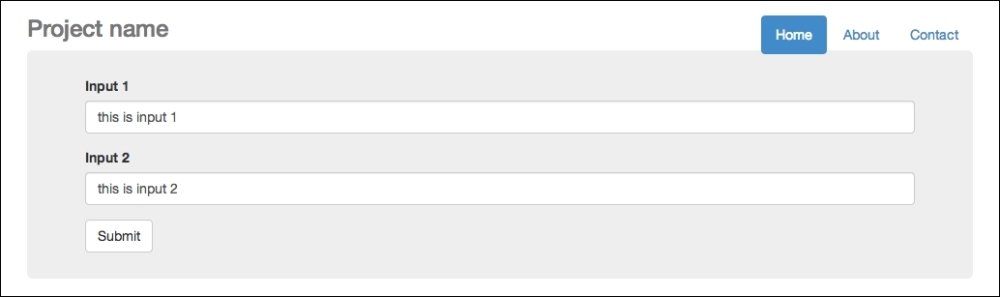

What we are going to code in this section is a simple user creation form, which sends the values to the backend/server side. On the client side, we are going to use JavaScript to prevent users from creating usernames with the a character and passwords containing the s character.

This is typical of many forms we see: we may want to prevent the user from creating input using certain characters.

As usual, if the user's input satisfies our requirements, our JavaScript code will enable the Submit button, enabling the user to create a new user.

With that in mind, let's start coding. To start off, create the following directory structure:

mistrust/

templates/

mistrust.html

mistrust.pySince this example is based on Tornado/Python and it has only one functionality (that of creating a user), this is a fairly straightforward piece of code. Open your editor and name a new file mistrust.py. The code is as follows:

import os.path

import re

import torndb

import tornado.auth

import tornado.httpserver

import tornado.ioloop

import tornado.options

import tornado.web

import unicodedata

import json

from tornado.options import define, options

define("port", default=8000, help="run on the given port", type=int)

class Application(tornado.web.Application):

def __init__(self):

handlers = [

(r"/", FormHandler)

]

settings = dict(

blog_title=u"Mistrust",

template_path=os.path.join(os.path.dirname(__file__), "templates"),

xsrf_cookies=False,

debug=True

)

tornado.web.Application.__init__(self, handlers, **settings)

class FormHandler(tornado.web.RequestHandler):

def get(self):

self.render("mistrust.html")

def post(self):

print self.get_argument('username')

print self.get_argument('password')

data = {

'success':True

}

self.write(data)

def main():

tornado.options.parse_command_line()

http_server = tornado.httpserver.HTTPServer(Application())

http_server.listen(options.port)

tornado.ioloop.IOLoop.instance().start()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()Basically, we have only one handler, FormHandler, which shows the form when we hit the / URL. The POST function simply receives the username and password. Presumably, we can save this information for our new user.

Next, let's work on the client-side code. Create a new file in the templates/ folder and name it mistrust.html. As usual, we start with a basic Bootstrap 3 template, which is as follows:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<title>Mistrust Example</title>

<!-- Bootstrap core CSS -->

<link href="//maxcdn.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/3.2.0/css/bootstrap.min.css" rel="stylesheet">

<style>

#username-error, #password-error {

color:red;

}

#success-msg, #fail-msg {

display:none;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<div class="container">

<div class="header">

<ul class="nav nav-pills pull-right">

<li class="active"><a href="#">Home</a></li>

<li><a href="#">About</a></li>

<li><a href="#">Contact</a></li>

</ul>

<h3 class="text-muted">Mistrust Example</h3>

</div>

<div class="jumbotron">

<h1>Create User</h1>

<div id="success-msg" class="alert alert-success" role="alert">Success</div>

<div id="fail-msg" class="alert alert-danger" role="alert">Oops, something went wrong</div>

<div role="form">

<div class="form-group">

<label for="username">User Name </label><span id="username-error"></span>

<input type="text" class="form-control" id="username">

</div>

<div class="form-group">

<label for="password">Password </label><span id="password-error"></span>

<input type="password" class="form-control" id="password">

</div>

<button id="send" type="submit" class="btn btn-success" disabled>Submit</button>

</div>

</div>

<div class="footer">

<p>© Company 2014</p>

</div>

</div> <!-- /container -->

<!-- Bootstrap core JavaScript

<script src="//ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/1.11.1/jquery.min.js"></script>

<script src="//maxcdn.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/3.2.0/js/bootstrap.min.js"></script>

</body>

</html>There is nothing special about this piece of code. It is simply a HTML template showing a form.

Next, insert the following JavaScript code beneath <script src="//maxcdn.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/3.2.0/js/bootstrap.min.js"></script>:

<script>

var okUsername = null;

var okPassword = null;

function checkUserNameValues() {

var values = $('#username').val();

if (values.indexOf("s") < 0) {

okUsername = true;

$('#username-error').html("");

}

else {

okUsername = false;

$('#username-error').html("Not allowed to use character 's' in your password");

}

if (okUsername === true && okPassword === true) {

$('#send').prop('disabled', false);

}

}

function checkPasswordValues() {

var values = $('#password').val();

if (values.indexOf("a") < 0) {

okPassword = true;

$('#password-error').html("");

}

else {

okPassword = false;

$('#password-error').html("Not allowed to use character 'a' in your password");

}

if (okUsername === true && okPassword === true) {

$('#send').prop('disabled', false);

}

}

function formEnter() {

var a = $('#username').keyup(checkUserNameValues);

var b = $('#password').keyup(checkPasswordValues);

}

// here will do the form post and simple validation

function submitForm() {

// here I will check for "wrong" stuff

if (ok_username === true && ok_password === true) {

// go ahead and post to ajax backend

var username = $("#username").val();

var password = $("#password").val()

var request = $.ajax({

url: "/",

type: "POST",

data: { username : username, password:password },

dataType: "json"

});

request.done(function( response ) {

if(response.success == true) {

$( "#success-msg" ).show();

}

else {

$("#fail-msg").show();

}

});

request.fail(function( jqXHR, textStatus ) {

$("#fail-msg").show();

});

}

else {

alert("Please check your error messages");

}

// enables or disables the button

return;

}

$('document').ready(function() {

// so here I will do the form posting.

formEnter();

$("#send").click(submitForm);

})

</script>We have four major functions in this piece of JavaScript code, which are discussed as follows:

checkUserNameValues(): This function checks whether the username is valid or not. For our purposes, it must not contain the s character. If it does, we will show an error message at the #username-error element.checkPasswordValues(): This function checks whether the password is valid or not. In this case, it is checking whether the password contains the s character or not. If it does, it will show an error message in #password-error.formEnter(): This function simply calls checkUserNameValues() and checkPasswordValues() whenever there is a keyup event when the user is in the process of entering their username or password.submitForm(): This function submits the form if the user input adheres to our rules, or it returns a fail message at the #fail-msg element.Now that we have coded the app, save everything and change directory to the root of the application. Issue the following command:

python mistrust.py

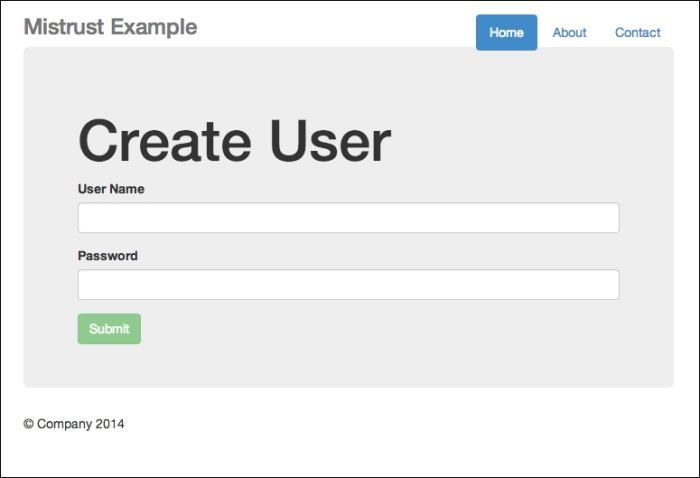

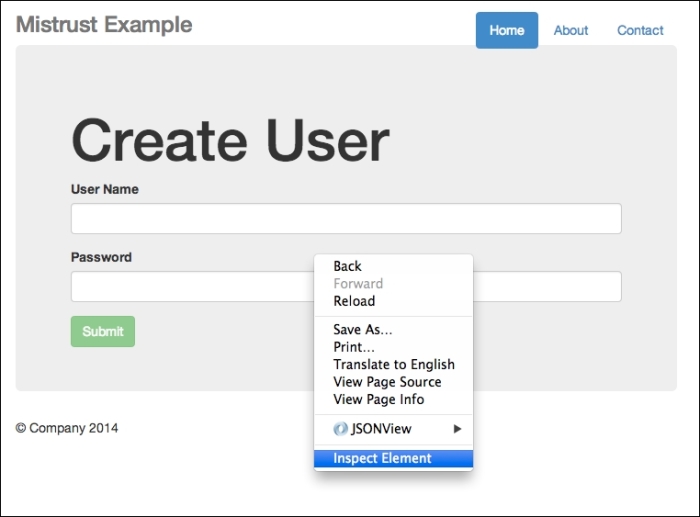

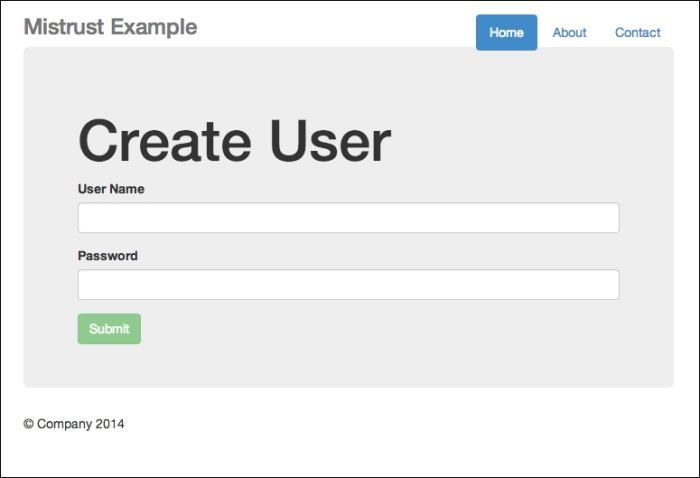

There is no need to use any database for this app. After you have issued this command, go to http://localhost:8000; you should see the following output:

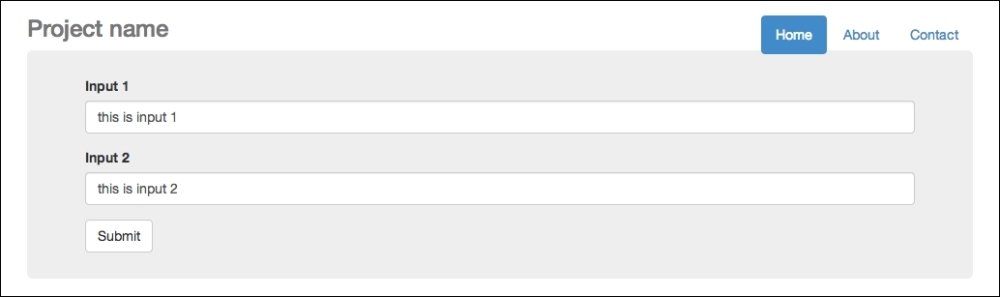

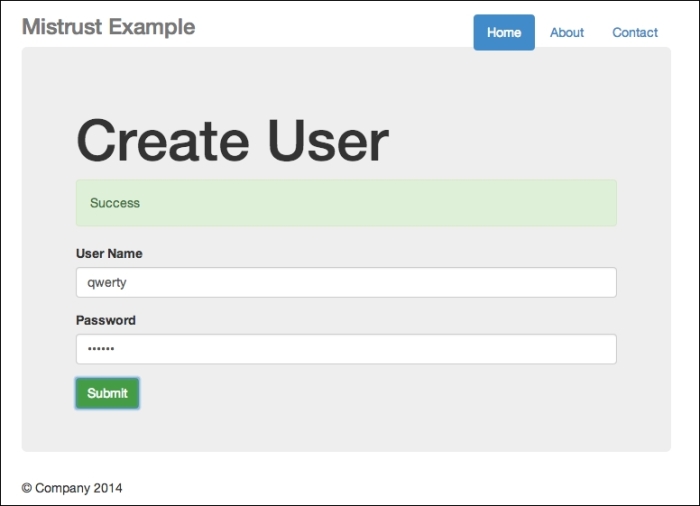

The Create User interface

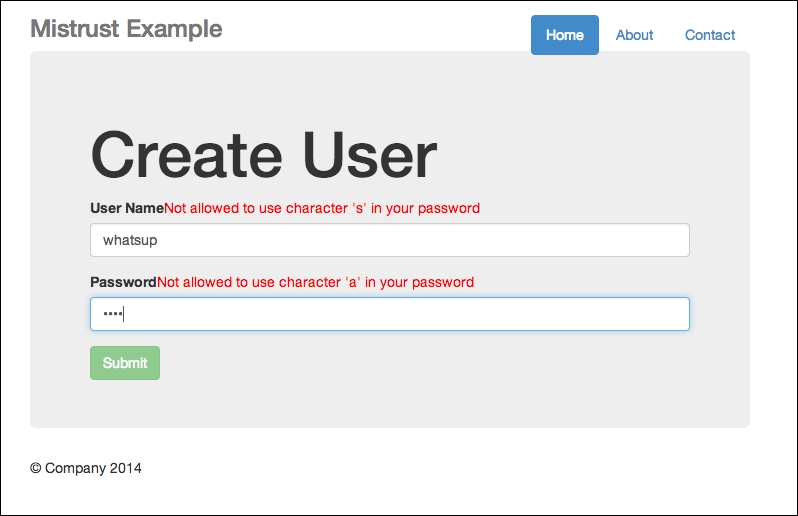

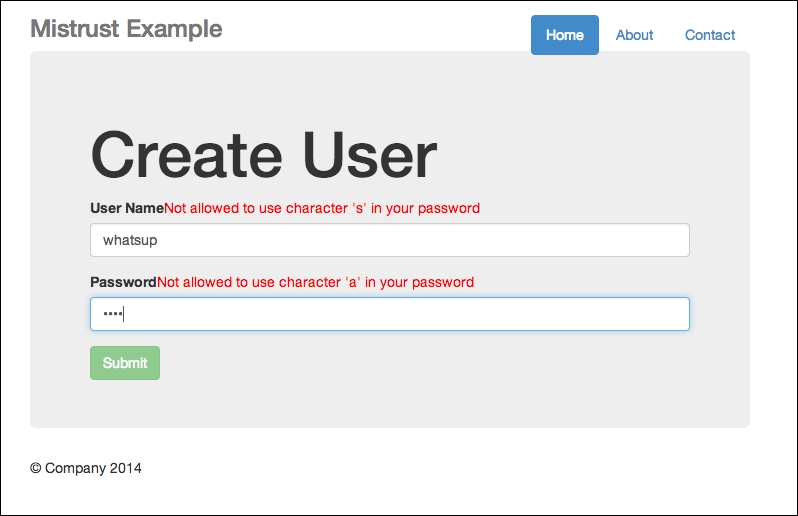

Now you can test the app. Enter your username and password. If you have entered something illegal, this is what you will see:

Error messages shown if input contains illegal characters

Note the error messages beside the User Name and Password fields.

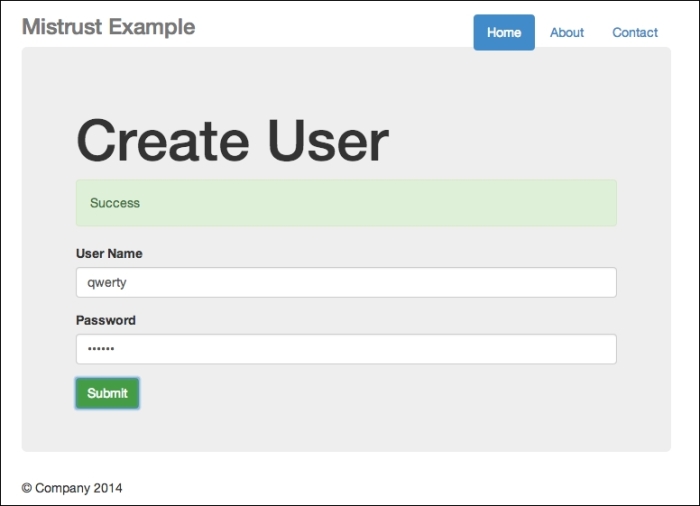

On the other hand, should you enter the credentials correctly, you will receive a successful message, as shown in the following screenshot:

Successful creation

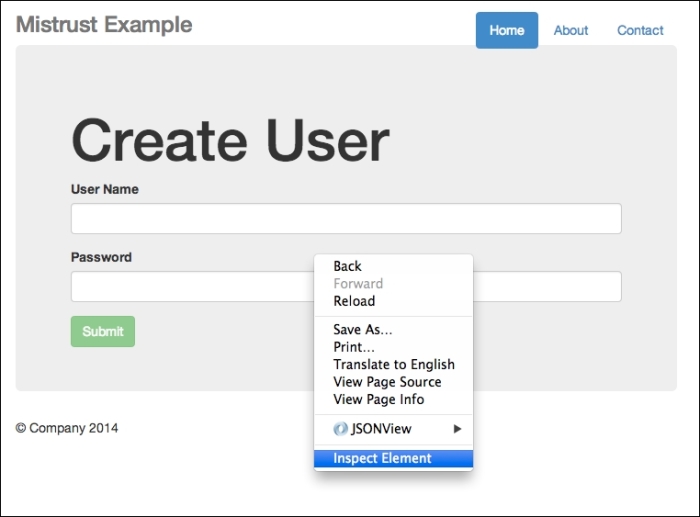

Now that we have made sure our code is working correctly, it's time to manipulate the code to show that we, as developers, should never trust the client.

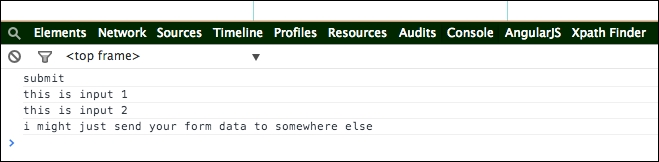

You need to perform the following steps to manipulate the JavaScript code:

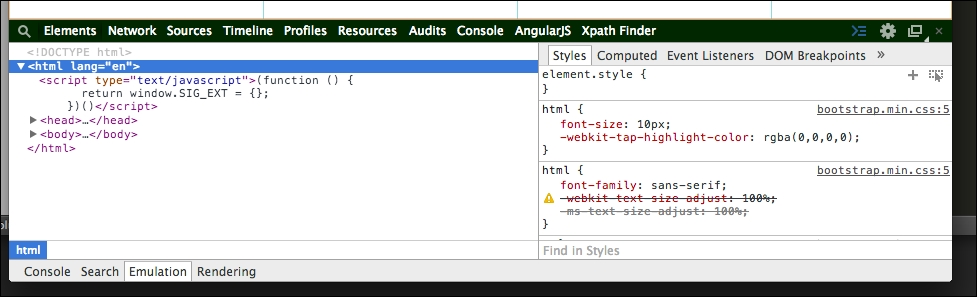

Right-click and select Inspect Element

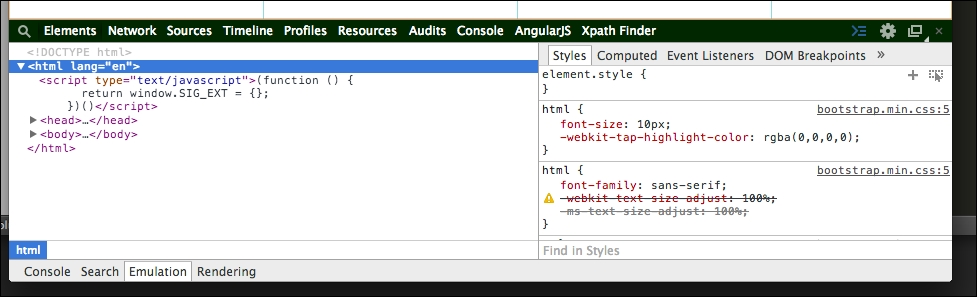

The developer tool interface

asd and asd for both your username and password, both of which are illegal under our rules. Going back to your developer tool, head straight to console, and type the following:ok_password = true ok_username = true

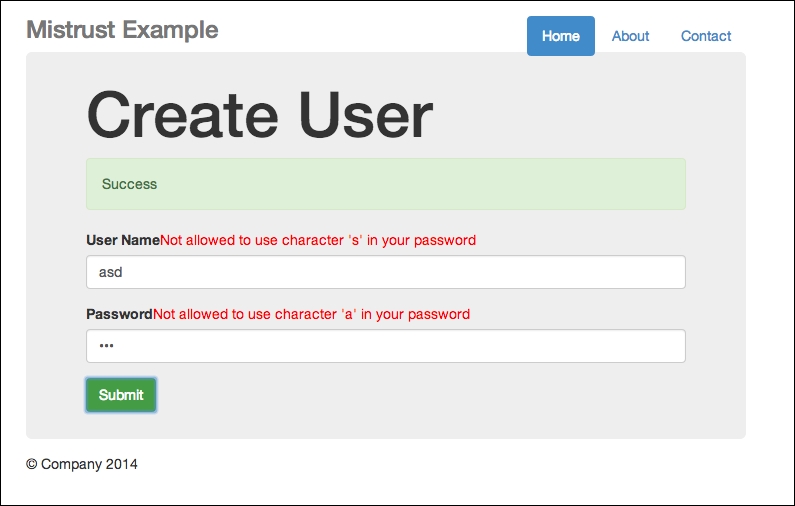

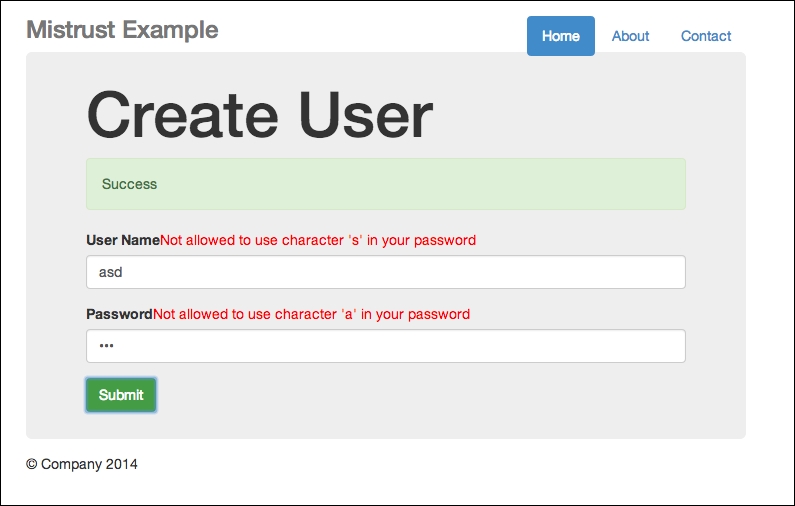

Presto! It succeeds!

An oxymoron—we have error messages, yet the submission is successful

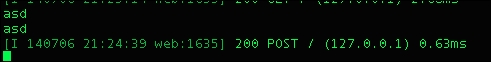

In my server, I receive both values: asd and asd, as shown in the following screenshot:

Even our backend receives a successful POST request

Weird isn't it?

Actually, it is not. Remember that the JavaScript code we write is sent to the client side, which means that it is free for all (malicious developers?) to manipulate. Look how much harm my simple technique can possibly cause: simply using Google's developer tools, I side-stepped the basic requirements of not using the s character and the a character for my username and password respectively.

For our particular example, we could have done something to prevent this from happening. And that is to include server-side checking as well. Now, feel free to check the code in mistrust2.py, and look for FormHandler. The post() function has now been changed, as follows:

class FormHandler(tornado.web.RequestHandler):

def get(self):

self.render("mistrust.html")

def post(self):

username = self.get_argument('username')

password = self.get_argument('password')

# this time round we simply assume false

data = {

'success':False

}

if 's' in username:

self.write(data)

elif 'a' in password:

self.write(data)

else:

data = {

'success':True

}

self.write(data)We simply look for illegal characters when accepting the username and password. Should they contain any illegal characters, we simply return a failed message.