Chapter 2. Chapter 7: A 30/60/90-day plan

“We need to hire someone to fix the words!” I have heard this phrase from multiple people on teams I’ve worked on, and UX leaders I’ve talked with. In each case, the person can point to the places in the experience where the words are “broken.” These people have recognized that fixing the words would help their organization or their customers advance in some important way.

In each case I have seen, there is enough “fixing” to be done to keep a person busy for years, but fixing the words will never be enough. Consider this metaphor: An experience with broken words is a house with broken walls. Fix the words as you would repair the walls.

If there’s only one broken wall, and it was built robustly, and the hole doesn’t affect the electrical, plumbing, or architectural support the building needs, then it can be fixed cheaply. The only problem might be choosing materials and wall coverings that match.

But when multiple walls are broken, or the breaks go through electrical, plumbing, or supporting timbers, then words can’t fix the hole by themselves. We’ll need to apply some engineering--in this case, content strategy--to fix the walls and support the building.

As an added benefit: Fixing those walls will make the whole building stronger.

When an experience has already been built with consistent terminology, voice, and information architecture, and ways to find, maintain, internationalize, and update its content, then all we would need to do is fix the words. When those things haven’t been considered, then we will need a strategic approach to fix the underlying experience.

In this chapter, I distill the 30/60/90-day plan I’ve used in three teams, at three companies. Each time, the team brought me in because they realized they (1) had a problem with words and (2) knew that they didn’t know how to fix it.

The actual number of days is an estimate, not a rule. The times have been pretty accurate for me in teams of roughly 350, 150, and 50 people. These three phases should be done thoroughly, but quickly--and definitely not perfectly. Their purpose is to fix the words; your method will create a basis for collaboration and iteration that makes the whole experience better.

The first 30 days, aka Phase 1: What and Who

The first 30 days is all about learning the experience, the people who will use it, and the team of people who build it. To be successful, I’ll need to know what’s important to each of them. At the same time, I need to build the team’s confidence that the time, energy, and money they spend on content will pay off.

My first task is to find a couple of key people to get the widest possible perspective on the organization. Those two or three people have a couple of key characteristics: they have broad knowledge of the organization, and they know why the organization decided to “fix the words.” In the best case scenario, those two or three people have different points of view from each other.

I ask these key people, in one-on-one, face-to-face meetings: Who is on the team? That is, who will affect what a person might encounter about the experience we’re making? I write down names from marketing, design, engineering, product owners, program managers, support agents, forum moderators, trainers, attorneys, and executives. I try to draw the organization, and ask these key contacts to correct my drawing.

Then I request half-hour meetings with each of those 10 to 20 people I’ve just found out about. In my invitation, I write something like, “Hi, I’m the new content person on product X. Your name came up as a person who’s important to the product and team, and I’m hoping to learn more from you.” I choose a time that’s likely to be convenient for them, and make sure I have enough time in my calendar to consolidate learnings between meetings.

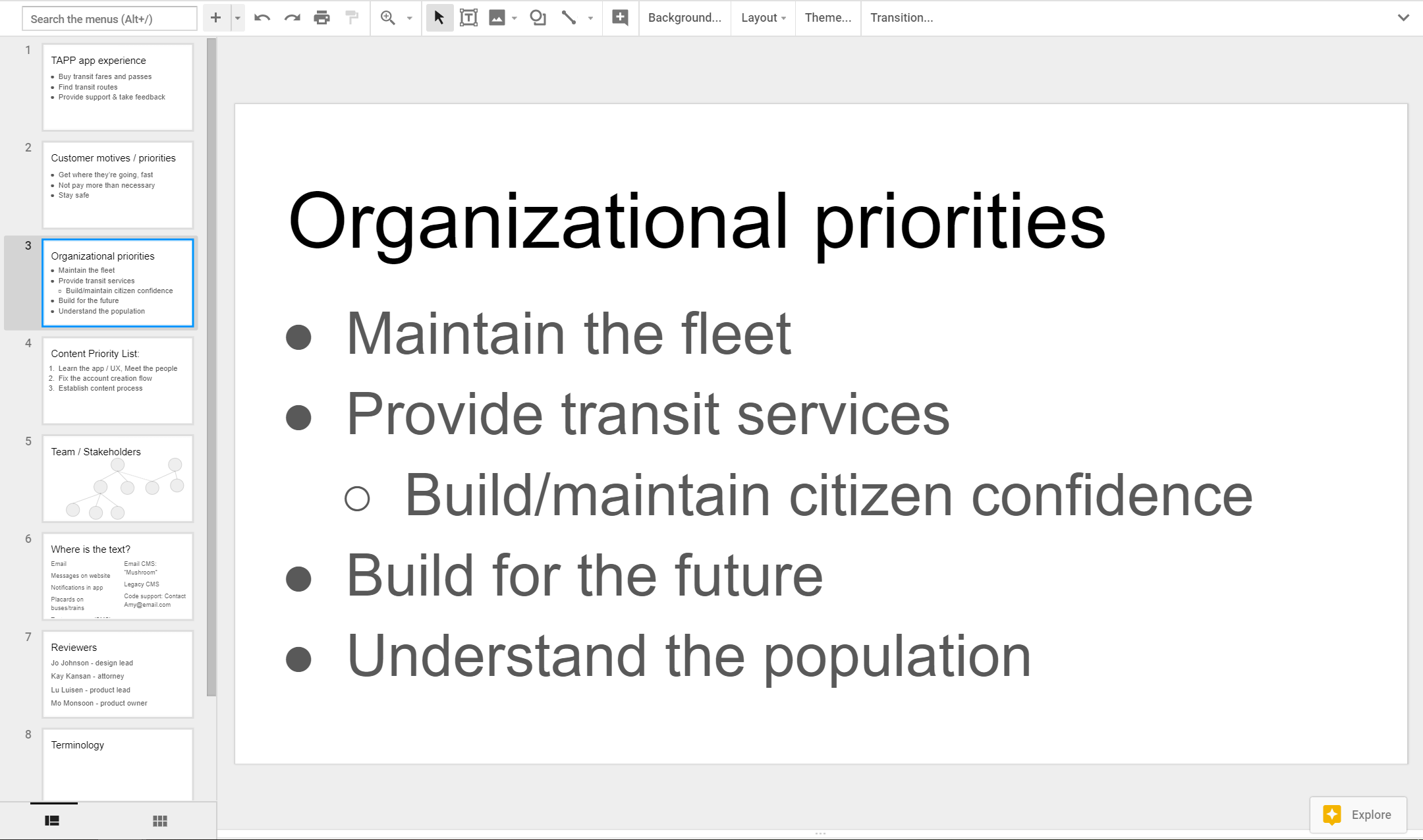

To prepare for the meetings, I make a mostly-empty document, whether that’s a slide deck or text document. As shown for TAPP in Figure 7.1, I use headings to create structure, and fill in the information I know so far. The document is intentionally rough and unpretty, to make it clear that I’m spending time learning the information, not “polishing” the presentation. It’s also shareable, and I make the link or document available to the people I meet with.

Figure 2-1. Figure 7.1 The first document I make has separate sections or slides to show the experience, the customer and business priorities, the initial content priorities or tasks, a diagram of the team and stakeholders, and placeholders to add info about the channels, platforms, terminology, and reviewers.

This first document, named “Content Strategy Notes” contains the following sections:

Definition of the experience

Customer motives

Organizational priorities

Priorities for content strategy

Team/Stakeholders

List of existing content

Reviewers

Terminology

Before the meetings, I add the information I think I know, in the briefest, most scannable form. Where I don’t know anything yet, I leave the slide or section empty. By doing so, I communicate (1) what I want to know, (2) that I know that I don’t know it yet, and (3) that sharing these things will be valuable to me. Then, I’m prepared to not only take notes in the meetings, but to organize and give context to the information I’m getting.

During the meeting, the important thing is to start to build the working relationship with the person I’m meeting with. To do that, and also to gain more information, we discuss the experience, customer, business, and priorities. If the other topics come up, I listen, take notes, and move on.

Example questions I ask:

To you, what’s the most important part of the experience?

To you, who are the customers? For an enterprise product, are they the people who buy it, or the people who use it? If it came down to one over the other, who do we prioritize?

How do these people solve the problem right now? How is that experience different?

What’s important to them? What motivates them? What are their priorities, their desires? Do we know what they like or dislike?

Among the people making and supporting the product, who will be an ally in making a great experience? What are their motivations, hopes, desires for it?

In the organization or industry, is there anything working against us? Is there anything working in our favor?

To you, what’s the most important thing I can work on?

Where are the words broken, or where can the words help the most?

As I listen and learn, I present the document and take notes at the same time, as much as possible. That way, I can show in real-time that I’m adding that person’s priorities to my priority list, and adding their information to my understanding. If what they say is already represented, I ask them to check and correct me.

Between meetings, I consolidate what I’ve learned. Note taking can get very messy! Sometimes I add notes as text in line, sometimes in comments. Sometimes, we use a whiteboard or paper, so I take pictures of those to add its content to the Content Strategy Notes.

One of the most important pieces of knowledge to develop is the list of existing content. In many cases, if a team has been working without a content professional, nobody actually knows what all of the content is. So when a new source or repository of text is mentioned, whether it is text in the UX, emails, notifications, websites, repositories of help documents, or canned responses, I add it to my Content Strategy Notes. Any content that affects the customer doing what they’re trying to do is something I should be aware of--even if I never work on those pieces of content.

Similarly, my ears perk up whenever I hear words used with special or unusual meanings. I add those to my document, as a new, baby terminology list inside the Content Strategy Notes. Having a list of terms, and my attempts at definitions of those terms, helps me ask the team to check and correct my understanding.

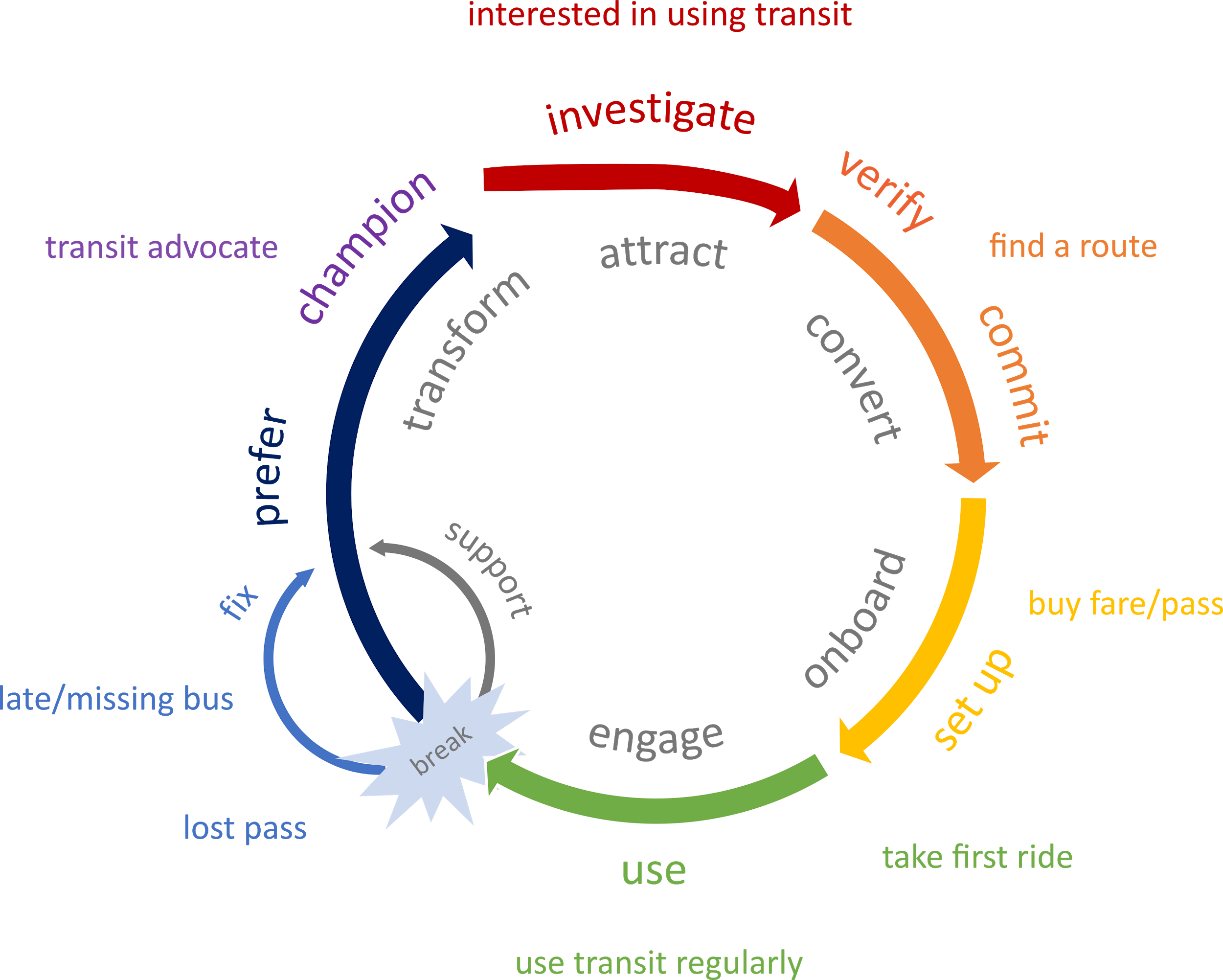

As my understanding of the experience starts to mature, I try to draw the lifecycle of the experience, like in Figure 7.2. This should show the journey of the customer through a cycle of using and staying with the experience. I adjust the length of sections to reflect the reality of this product, this organization, and the people who will buy and/or use this experience, at this moment in time.

When I have the experience drawn, I add it to my Content Strategy Notes. I use the diagram to ask members of the team where they think the experience isn’t working. I also use it to explain what I’m there to do: I will be making the content that will help spin the wheel, for the business and for the customer.

Figure 2-2. Figure 7.2 A diagram of the customer journey through the TAPP experience. TAPP attracts people when they are interested in using transit, converts them by showing routes and fares that will work for them, onboards them by selling them fares and passes. They start to use TAPP with their first ride, and may engage to the level of using transit regularly--the goal of the TAPP organization. As the customer continues to use transit, parts of the experience may break. A person could become so enthusiastic about their experience with TAPP that they become an advocate for using transit, and bring other people into using TAPP.

By the end of the second week, if not earlier, I start to get tactical requests: Can you rewrite this email? What should go in this error message? I start these first writing tasks in parallel to my learning about the end-to-end business and experience, because the strategy will only work if the writing can get into the experience.

These first writing tasks are a great testing ground for the ideas percolating in my brain about who the customer is, what our purpose is, and how the customer and organization priorities could be expressed in the UX. This is also my opportunity to show how I work.

I draft text in the design. This might be my first time working in a designer’s file, or with a copy of that file. More likely, I have a screenshot of bad text on a screen, which I will hack to show different text. The person requesting the text may expect nothing more than an email or chat message with the text to use, but I will demonstrate that UX content should always be reviewed as part of the design, the way the customer will see it.

I look for existing resources about voice or tone, and list them in my notes. These could be brand guidelines, voice charts, principles, or they may not exist at all. I use what already exists to inform the options I write for the new, requested content.

I use what I know so far to write at least three good options for the content. I make the options as different from each other as possible to show the power of what we can do with words. I make them as effective as I can to meet the purpose the customer has for that moment, and the purpose the business has for that moment.

To the person who requested the text, I explain the reasons that any one of the three options might be the right choice. In general, I learn more about the problem at this time, and need to draft more options! This revising is a normal part of the process, and it lets me understand the experience and the business at a practical, hands-on level.

When we agree on one or more of the text options, I ask: Who else should be reviewing this? I suggest some names I learned from my interviews, and use the names they recommend. I send my first requests for review, listing my recommendation first, and one or two alternates, including the reasoning.

At the end of these first 30 days, I’ve talked to most of the right people, I’m in most of the right meetings and internal communication channels, like group emails and chat groups, and I’ve drafted my first text.

My Content Strategy Notes, the document I started at the beginning, contains at least the following:

A prioritized list of tactical content production or improvement tasks

Description(s) of customer and/or user motivations and priorities that my partners agree with

Description of the organization’s priorities and constraints

Beginnings of lists: channels, terminology, content reviewers

Links or images of first, tactical content work

I know I’m ready for Phase 2 when I have built new relationships with my team, and have equipped myself with the information contained in the Content Strategy Notes.

30-60 days, aka Phase 2: Fires and Foundations

In this second phase of work, half of my time is spent chipping away at urgent, “on fire” work. Doing the “on fire” work helps provide a content development platform to test, practice, and create the foundational pieces that will help the work go better and faster in the future. It helps me build my understanding of the team, the experience, and the people who will use the experience. Just as important, it helps me build trust with the team: They say it’s broken, so I’ll fix it.

As much as possible during this second phase, I delay effort on larger, systemic changes. The text I write in this second month is unlikely to be the best writing I’ll do for the experience. It won’t be consistent, because there’s no consistency defined. It won’t be in the ideal voice, because voice isn’t defined. To do good work on systemic changes, that work must be categorized and prioritized against the strategy and against the development schedule to avoid randomizing the team and fracturing my own attention.

Right now, before those systemic changes begin, is the time to measure the baseline of how the UX content is meeting customer and business needs. If the team can’t tell where in the experience people drop out, or where they fail to engage, or where they make the decision to buy or commit, now is the moment to specify and advocate for the measurements, research, or instrumentation necessary to notice a change.

Even without automatic instrumentation, this is the time to examine the “broken walls” in the experience. I try to use the experience myself, recording the experience or taking screenshots as I go. I consume the usability research already conducted, if it exists. Then I apply heuristic measures to the existing content.

I make initial reports on those experiences--the baselines I’ll seek to improve and report on again, in the future. The report includes what we know about customer behavior, sentiment, and a scorecard of content usability based on the heuristics, for that particular part of the experience. These initial reports indicate what’s working, what isn’t working well yet, and which work I recommend prioritizing.

At first, I share the report informally with members of the team most directly involved with creating the experience. It’s a report that outlines problems in what they already built, so I don’t share too widely, nor with too much fanfare. Later, after the experience is improved, I’ll use the report as a baseline to measure improvement from.

As I handle these “fires,” the other half of my time is spent setting up the foundational pieces so that I can work and collaborate faster and more effectively. I need to set up tools for content creation, sharing, and organization, code environments, partnerships and processes that integrate with the team, and to track, manage, and prioritize the work to be done.

Track the pieces and the whole

I ended the first 30 days with a basic sketch of content work to be done, and work requests will start to flood in. Some requests are for single pieces of text, and other requests encompass hundreds or thousands of individual items: text through an entire experience, error messages, articles and videos, notifications, and more.

On any given day, UX writers create and review content with designers, researchers, executives, support agents, attorneys, and in code, on multiple projects. At a minimum, the tracking system, whether it is a ticket or bug tracking system like Team Foundation Studio or Jira, or a simple spreadsheet, should serve as a central place to gather and prioritize tasks, and include basic information. That information should include the task’s deadline, who asked for it, who’s responsible for it, and the locations of any related files. By using a tracking system, I will keep myself and my team (when there is a team) afloat on the flood of work to be done.

Work tracking also shows the scope and shape of the whole content picture. I can see where most of the work is concentrated. By comparing the work to the broader pictures of the organization and the experiences, I can see which parts of the organization I haven’t engaged enough with, and which parts of the experience I haven’t examined.

As this work continues, I uncover more repositories of content. I request access to the content and meet the people responsible for it. I build on the list I began in the first 30 days, adding the file systems, code repositories, web pages, and content management systems. As I continue to build the content strategy, it will be helpful to be able to illustrate the complexity of the content ecosystem.

Minimum viable process

Knowing the work to be done gives me the scope of the battle, but doesn’t help me fight it. In these second 30 days, I need to have tool-chain conversations with engineering, design, and product teams to hammer out the process. The first (few) projects from the first 30 days can help set the context: Did that delivery method work for them? Do they have any feedback? What’s the best way to get that person’s input?

I want to listen to what people expect and need from me, and what tools they expect us to use together. I want to steer the work toward a repeatable process, so that not only is my work easier, but all of my stakeholders know what they can expect from me. I also want to make the simplest possible process, because optimizing too early will make the processes hard to change.

Continuing my Content Strategy Notes document from the first 30 days, I draw a practical, basic process for a content workflow (Figure 7.3):

Content requested

Content draft

Give to engineer for coding

Content support as needed

Design review

Code review

Release process

Content released!

Figure 7.3 A basic process for UX content, from request, through drafting, review, coding, code review, and release.

The process starts with a content request: this could be a change I request, or a change someone else has asked for. The content is drafted, and goes through a drafting and design review process. When it passes the design review, it is given to an engineer--usually with a bug or other kind of work item opened in a ticketing system used to track engineering work.

The engineer gets additional content support as needed, for example, when the engineer discovers more error messages or updates to related content are needed. When the code is complete, it gets reviewed with the engineering team’s process and also for a last check on the content before the experience is released.

I get feedback from product owners, marketing and business leaders about the process. I ask where it should change to best fit with their system. I show them when and how to involve me (making requests), and when and how I’ll involve them (design and code review.) I ask who I should put on the review lists, and suggest people I can contact both regularly and as needed, to keep engineering unblocked. I add those people to the list of reviewers I started in the first 30 days. I find out the basics of how I should open work items for developers, and how to connect to their code review system.

Sometimes, a key person in the organization will say “I want to review every piece of text.” In my experience, they have thoroughly meant it--and they also don’t want to sit down and walk through the code, every time there is a change. What people want is confidence that the text won’t increase the organization’s liability. They want to be sure that the strings accurately reflect the company’s brand. They want to have the gut feeling that the strings “feel right” in the product. By drawing the content process, I have something to point to and say “Right here, let’s look at the strings together. You give me feedback, and I’ll make it right.”

The process helps make clear who has responsibility for the content. The best working relationships I have experienced are the ones in which the product owner has responsibility for what the experience is supposed to do, the designer has responsibility for the interaction and appearance of the experience, and the UX writer has responsibility for the content. We have to partner closely together, and we all need collaboration with researchers, engineers, and other stakeholders.

Document the content strategy

To do great work, I need to think systematically about the deep connective tissue of the content: the core terminology, the voice that permeates the conversations the product or service has with the customer, and the tone that the product has at specific moments in the experience, responding to the expected emotional state of the customer.

But not only do I need these fundamentals of content design, I need my teams to understand the systemic importance of content. Documenting the content strategy helps me demonstrate how it is useful to the organization, but that documentation can be its own uphill battle. Not only is it difficult, technical work, it takes time and energy.

I make a point of repeating: The purpose of documenting internal strategy is to make future tactical decisions easier, faster, and more consistently. If the strategy is not being used, it’s useless. So here’s what I use it for:

Terminology creates consistency and reduces time spent rehashing choices about how a particular concept is represented in the experience.

Voice attributes guide the direction of content creation and iterations, and tie-break between good text options.

The list of reviewers includes and excludes the right people in the content process strategically, instead of creating tactical political complications.

Documented organizational priorities and customer motivations focus the content by defining the core UX problem that it helps to solve.

These are living documents. Pieces were begun in the first 30 days, and need to be further developed. Throughout their existence, when they are wrong, they need to be updated. They should be reviewed on a regular cadence (at least annually), and updated when there are organizational changes.

Here’s how I know I’m at the end of the second phase:

I’ve passed at least these milestones:

New content created

Tracking system and process established

Poorly-performing content updated

Legal sign-off on a piece of liability-sensitive text

Marketing sign-off on a piece of brand-sensitive text

At least these indicators of trust have appeared:

Leaders including me as the responsible party for in-product text

Casual requests from non-managers to work on individual strings

Active inclusion from product and design in early design thinking

About 75% of this strategic work is complete:

A tracking system for content tasks

Alignment about customer motivations and business priorities

Knowledge of the existing content, and how to access it

Terminology list

Voice and tone map

Another indicator of the end of Phase 2 is a sense that I could be doing slightly more. There is nothing routine, static, or conventional about the content work done in phases 1 or 2, but now, the urgent, distracting, tactical work is complete. Just as importantly, the important foundations are laid. The UX content is ready to have an enormous impact on the quality and effectiveness of the experience to meet both business and customer goals. It is time for Phase 3.

60-90 days, aka Phase 3: Rapid growth

“A good plan, violently executed now, is better than a perfect plan next week.” – General George S. Patton.

The strategy is nearly done, which is as good as a strategy ever gets. It is time to present the strategy as a whole for the first time. The outcome of the presentation is to cement the solid foundation built with my team and my leadership: They should see that the content strategy is created considerately, together, and that the work has a purpose. By signing off on the strategy, they validate and support the work to be done.

Communication about the work is a critical part of the work, and might be the hardest part to get right. The presentation includes a summary of all the parts created to date: the tracking process and list of current tasks, the content landscape, alignment on customer and business priorities, terminology list, and voice chart. The summary is solid enough that the important (or controversial) ideas are covered, but unpolished enough to show that I haven’t been wasting time polishing internal documents.

Ideally, everybody at the presentation has participated in the process of creating the strategy. They get to see the fruition of their own work and advice, and as a result, the fruition of their decision to hire me. There will be feedback either during or after the presentation, and that’s good too: it means people care and are invested in the content strategy working.

I seek feedback during and after the presentation, because it provides the corrections necessary now to be successful later. If the feedback is that the strategy is wrong, I thank them for their perspective. If they’re wrong, it may be simply that the presentation of the work didn’t scratch their itch. If they’re right, it’s fantastic that I’ve gotten correction so early. It’s only the second (or third) month on the job, so it’s the best time to make adjustments.

During and after the presentation, I’m deeply engaged in tracked, prioritized work. I am following the process defined in phase 2 to respond to requests and to make requests for content changes. The excitement of the ramp-up phase is winding down, but there will continue to be plenty of strategic and tactical work to be done. I’ll apply, and sometimes revisit and tweak the strategy. I’ll have more time and energy to apply best practices to new and newly-updated work, and I’ll be a consistent advocate for the team to consider their customers every time they consider the words.

Phase 3, at roughly 90 days, is over when the process of creating content for the experience is healthy enough that I can start to imagine broadening the scope of what content strategy can do for the organization. Keeping up with the wider world of how content is used is an essential benefit I bring to the experience and to my team. I check in on trends in the field, and on the rest of the content being served to customers about my product. I look to strengthen connections to be made with marketing, operations, and knowledge management. I look for opportunities in the industry, like content-bots using machine learning to pre-write content. I seek out new research, like best practices about titles, labels, accessibility, and inclusion.

Summary: To Fix the Words, Build Strong Foundations

To create content that aligns to the business and customer purpose, we start by understanding not only those purposes, but who our teammates are in this adventure, what work they have done, and which work they didn’t know to do yet. In phase 2, we fix urgent problems while building the scaffolding and framing that will help us organize and show the effect of future work. Phase 3 is the beginning of work that uses the power of content tools from the beginning, to be more effective than ever before.

There are a lot of content accomplishments in this 30/60/90 day plan, but the work that pays the most dividends comes from doing the work visibly, in partnerships with the team. In the process of doing the work, the text in the experience goes from being invisible, and “a tax” to being visible and valued. By making the content strategy visible in presentations of voice and terminology, the team and executives see that you have unlocked a new power tool to meet business and customer intents. By making the content tasks visible as tickets or bugs in the tracking system, the team sees how content can support and advance the goals of engineering, design, and business, while it supports the customer.

This plan has helped me create the basis for collaborative, iterative content creation. With these tools, I have had the privilege of helping people do what they came to the experience to do, and meet the goals of the business. And isn’t that the whole point?