Chapter 5. Transactions

Transactions are at the heart of Bitcoin. Transactions, simply put, are value transfers from one entity to another. We’ll see in Chapter 6 how “entities” in this case are really smart contracts. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s first look at what Transactions in Bitcoin are, what they look like and how they are parsed.

Transaction Components

At a high level, a Transaction really only has 4 components. They are:

-

Version

-

Inputs

-

Outputs

-

Locktime

A general overview of these fields might be helpful. Version indicates what additional features the transaction uses, Inputs define what Bitcoins are being spent, Outputs define where the Bitcoins are going and Locktime defines when this Transaction starts being valid. We’ll go through each component in depth.

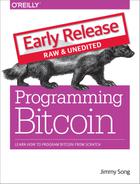

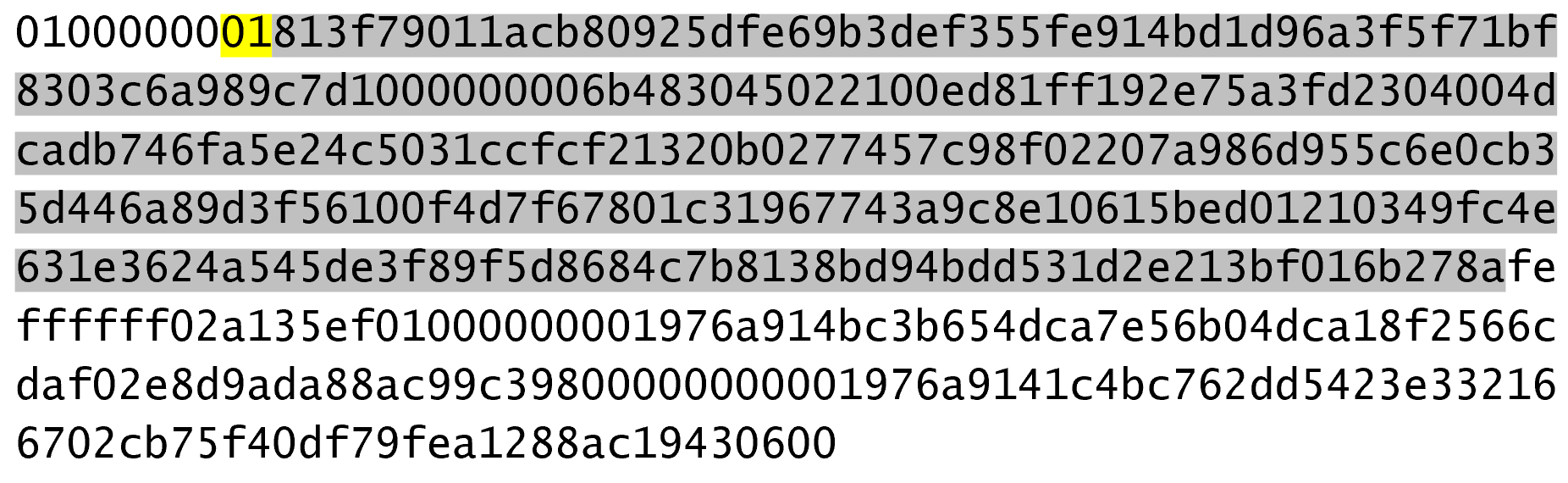

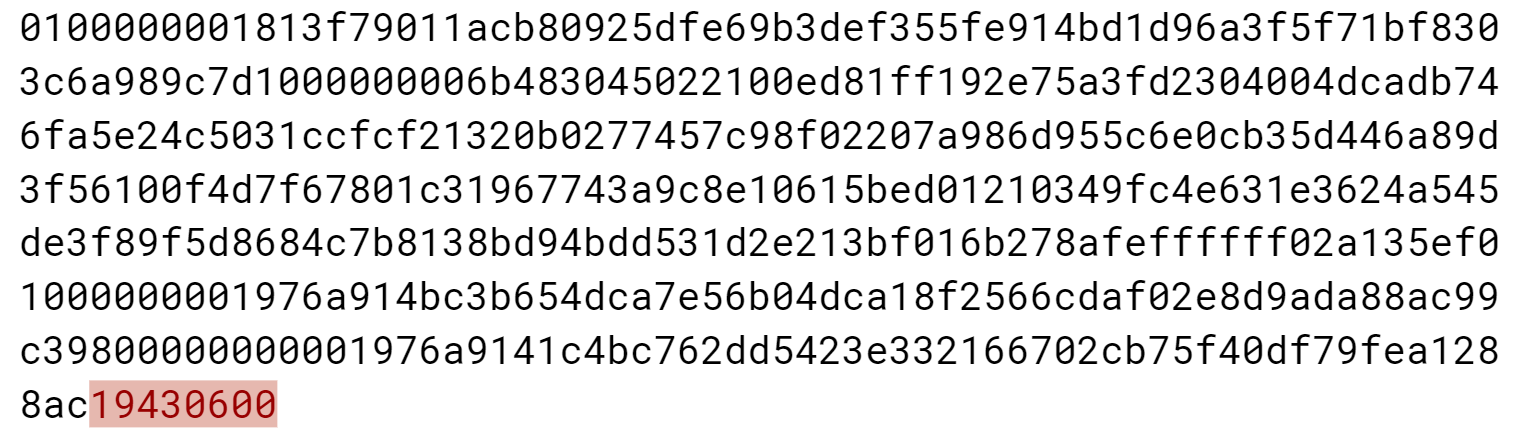

Figure 5-1 shows a hexadecimal dump of a typical transaction that shows which parts are which.

Figure 5-1. Transaction Components, Version, Inputs, Output and Locktime

The differently highlighted parts represent Version, Inputs, Outputs and Locktime respectively.

With this in mind, we can start constructing the Transaction class, which we’ll call Tx:

classTx:def__init__(self,version,tx_ins,tx_outs,locktime,testnet=False):self.version=versionself.tx_ins=tx_insself.tx_outs=tx_outsself.locktime=locktimeself.testnet=testnetdef__repr__(self):tx_ins=''fortx_ininself.tx_ins:tx_ins+=tx_in.__repr__()+'\n'tx_outs=''fortx_outinself.tx_outs:tx_outs+=tx_out.__repr__()+'\n'return'tx: {}\nversion: {}\ntx_ins:\n{}tx_outs:\n{}locktime: {}'.format(self.id(),self.version,tx_ins,tx_outs,self.locktime,)defid(self):'''Human-readable hexadecimal of the transaction hash'''returnself.hash().hex()defhash(self):'''Binary hash of the legacy serialization'''returnhash256(self.serialize())[::-1]

Input and Output are very generic terms so we specify what kind of inputs they are. We’ll define the specific object types they are later.

We need to know which network this transaction is on in order to be able to validate it fully.

The

idis what block explorers use for looking up transactions. It’s the hash256 of the transaction in hexadecimal format.

The hash is the hash256 of the serialization in Little-Endian. Note we don’t have the

serializemethod yet, so until we do, this won’t work.

The rest of this chapter will be concerned with parsing Transactions. We could, at this point, write code like this:

classTx:...@classmethoddefparse(cls,serialization):version=serialization[0:4]...

This method has to be a class method as the serialization will return a new instance of a

Txobject.

We assume here that the variable

serializationis a byte array.

This could definitely work, but the transaction may be very large. Ideally, we want to be able to parse from a stream instead. This will allow us to not need the entire serialized transaction before we start parsing and that allows us to fail early and be more efficient. Thus, the code for parsing a transaction will look more like this:

classTx:...@classmethoddefparse(cls,stream):serialized_version=stream.read(4)...

This is advantageous from an engineering perspective as the stream can be a socket connection on the network or a file handle.

We can start parsing the stream right away instead of waiting for the whole thing to be transmitted or read first.

Our method will be able to handle any sort of stream and return the Tx object that we need.

Version

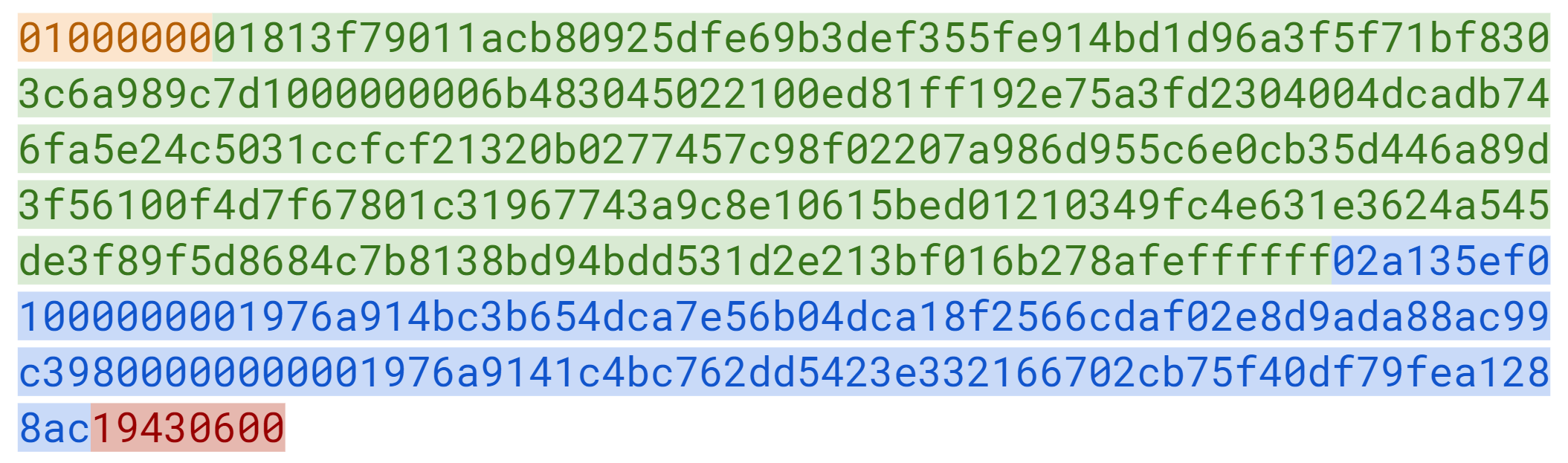

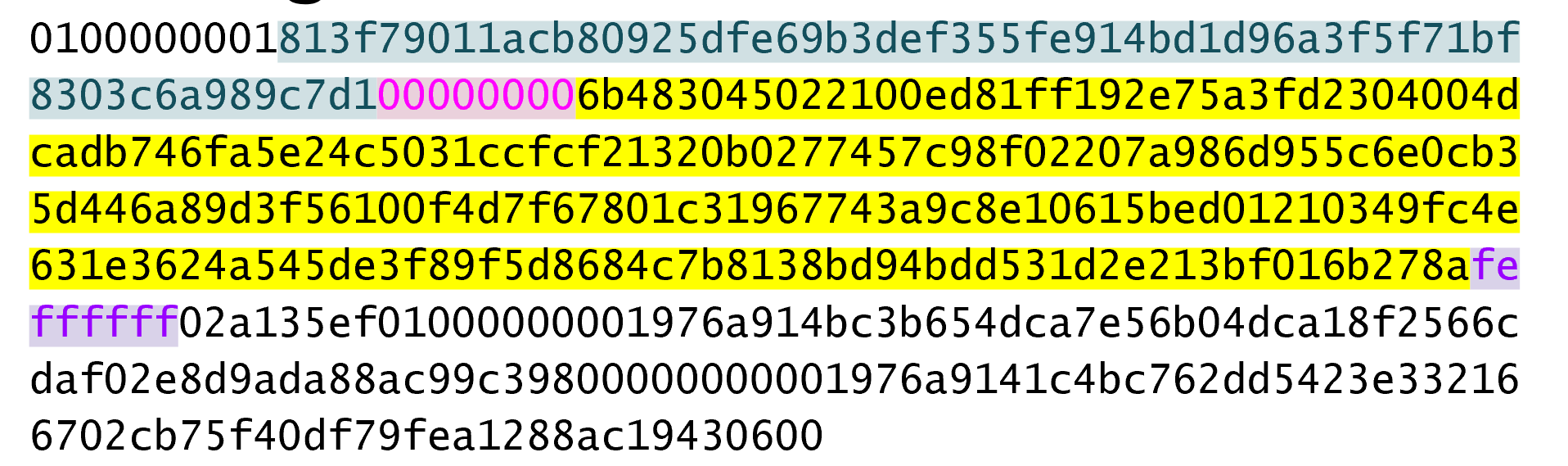

Figure 5-2. Version

When you see a version number in something (Figure 5-2 shows an example), it’s meant to give the receiver information about what the versioned thing is supposed to represent. If, for example, you are running Windows 3.1, that’s a version number that’s very different than Windows 8 or Windows 10. You could specify just “Windows”, but specifying the version number after the operating system helps you know what features it has and what API’s you can program against.

Similarly, Bitcoin transactions have version numbers.

In Bitcoin’s case, the transaction version is generally 1, but there are cases where it can be 2 (transactions using an opcode called OP_CHECKSEQUENCEVERIFY as defined in BIP112 require use of version > 1).

You may notice here that the actual value in hexadecimal is 01000000, which doesn’t look like 1.

Interpreted as a Little-Endian integer, however, this number is actually 1 (recall the discussion from Chapter 4).

Exercise 1

Write the version parsing part of the parse method that we’ve defined. To do this properly, you’ll have to convert 4 bytes into a Little-Endian integer.

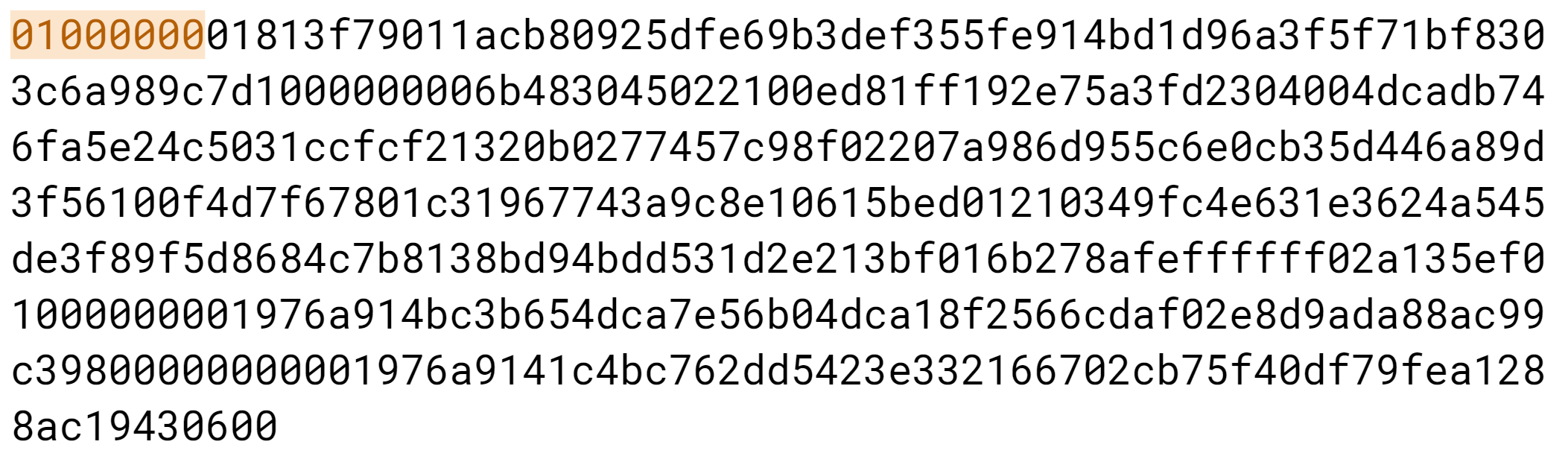

Inputs

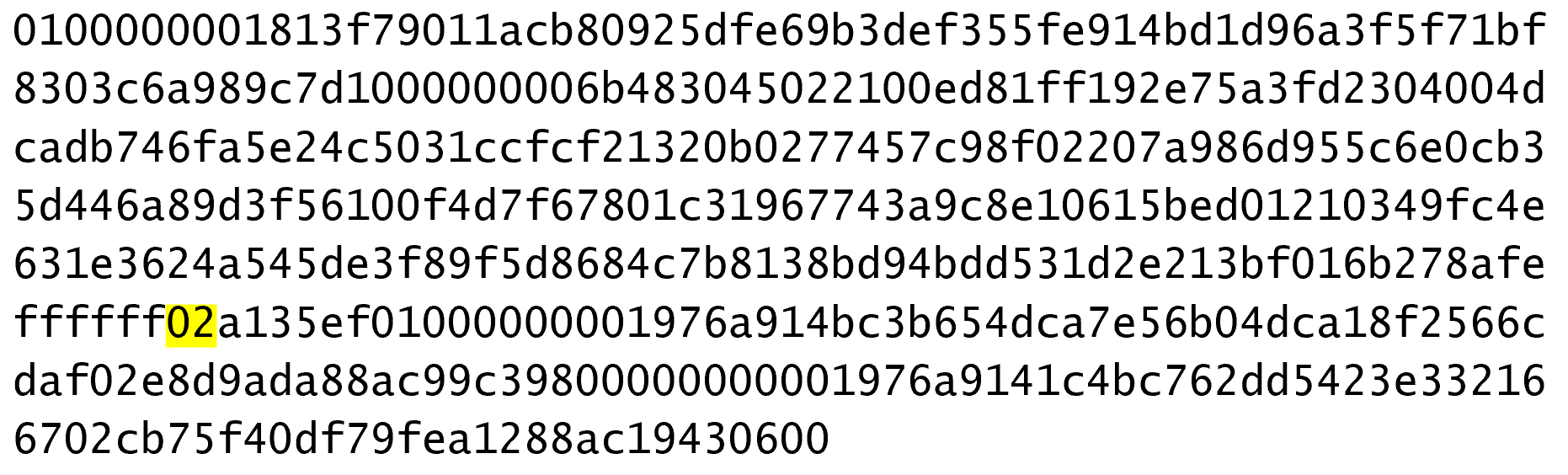

Figure 5-3. Inputs

Each input points to an output of a previous transaction (see Figure 5-3). This fact requires more explanation as it’s not intuitively obvious at first.

Bitcoin’s inputs are spending outputs of a previous transaction. That is, you need to have received Bitcoins first to spend something. This makes intuitive sense. You cannot spend money unless you received money first. The inputs refer to Bitcoins that belong to you. There are two things that each input needs to have:

-

A reference to the previous Bitcoins you received

-

Proof that these are yours to spend

The second part uses ECDSA (Chapter 3). You don’t want people to be able to forge this, so most inputs contain signatures which only the owner(s) of the private key(s) can produce.

The inputs field can contain more than one input. This is analogous to using a single 100 bill to pay for a 70 dollar meal or a 50 and a 20. The former only requires one input (“bill”) the latter requires 2. There are situations where there could be even more. In our analogy, we can pay for a 70 dollar meal with 14 5-dollar bills or even 7000 pennies. This would be analogous to 14 inputs or 7000 inputs.

The number of inputs is the next part of the transaction shown in Figure 5-4:

Figure 5-4. Number of Inputs

We can see that the byte is actually 01, which means that this transaction has 1 input.

It may be tempting here to assume that it’s always a single byte, but it’s not.

A single byte has 8 bits, so this means that anything over 255 inputs would not be expressible in a single byte.

This is where varint comes in.

Varint is shorthand for variable integer which is a way to encode an integer into bytes that range from 0 to 264-1.

We could, of course, always reserve 8 bytes for the number of inputs, but that would be a lot of wasted space if we expect the number of inputs to be a relatively small number (say under 200).

This is the case with the number of inputs in a normal transaction, so using varint helps to save space.

You can see how they work in the VarInt sidebar.

Each input contains 4 fields. The first two fields point to the previous transaction output and the last two fields define how the previous transaction output can be spent. The fields are as follows:

-

Previous Transaction ID

-

Previous Transaction Index

-

ScriptSig

-

Sequence

As explained above, each input is has a reference to a previous transaction’s output. The previous transaction ID is the hash256 of the previous transaction’s contents. The previous transaction ID uniquely defines the previous transaction as the probability of a hash collision is impossibly low. As we’ll see below, each transaction has to have at least 1 output, but may have many. Thus, we need to define exactly which output within a transaction that we’re spending which is captured in the previous transaction index.

Note that the previous transaction ID is 32 bytes and that the previous transaction index is 4 bytes. Both are in Little-Endian.

ScriptSig has to do with Bitcoin’s smart contract language Script, and we will be discussing it more thoroughly in Chapter 6. For now, think of ScriptSig as opening a locked box. Opening a locked box is something that can only be done by the owner of the transaction output. The ScriptSig field is a variable-length field, not a fixed-length field like most of what we’ve seen so far. A variable-length field requires us to define exactly how long the field will be which is why the field is preceded by a varint telling us how long the field is.

Sequence was originally intended as a way to do what Satoshi called “high frequency trades” with the Locktime field (see Sequence and Locktime), but is currently used with Replace-By-Fee and OP_CHECKSEQUENCEVERIFY.

Sequence is also in Little-Endian and takes up 4 bytes.

The fields of the input look like Figure 5-5:

Figure 5-5. The Fields of an Input, Previous Tx, Previous Index, ScriptSig and Sequence

Now that we know what the fields are, we can start creating a TxIn class in Python:

classTxIn:def__init__(self,prev_tx,prev_index,script_sig=None,sequence=0xffffffff):self.prev_tx=prev_txself.prev_index=prev_indexifscript_sigisNone:self.script_sig=Script()else:self.script_sig=script_sigself.sequence=sequencedef__repr__(self):return'{}:{}'.format(self.prev_tx.hex(),self.prev_index,)

A couple things to note here. The amount of each input is not specified. We have no idea how much is being spent unless we look up in the blockchain for the transaction(s) that we’re spending. Furthermore, we don’t even know if the transaction is unlocking the right box, so to speak, without knowing about the previous transaction. Every node must verify that this transaction unlocks the right box and that it doesn’t spend non-existent Bitcoins. How we do that is discussed more in Chapter 7.

Parsing Script

We’ll delve more deeply into how Script is parsed in Chapter 6, but for now, here’s how you get a Script object from hexadecimal in Python:

>>>fromioimportBytesIO>>>fromscriptimportScript>>>script_hex=('6b483045022100ed81ff192e75a3fd2304004dcadb746fa5e24c5031ccf\cf21320b0277457c98f02207a986d955c6e0cb35d446a89d3f56100f4d7f67801c31967743a9c8\e10615bed01210349fc4e631e3624a545de3f89f5d8684c7b8138bd94bdd531d2e213bf016b278\a')>>>stream=BytesIO(bytes.fromhex(script_hex))>>>script_sig=Script.parse(stream)>>>(script_sig)3045022100ed81ff192e75a3fd2304004dcadb746fa5e24c5031ccfcf21320b0277457c98f0220\7a986d955c6e0cb35d446a89d3f56100f4d7f67801c31967743a9c8e10615bed010349fc4e631\e3624a545de3f89f5d8684c7b8138bd94bdd531d2e213bf016b278a

Note that the

Scriptclass will be more thoroughly explored in Chapter 6. For now, please trust that theScript.parsemethod will create the object that we need.

Exercise 2

Write the inputs parsing part of the parse method in Tx and the parse method for TxIn.

Outputs

As hinted in the previous section, outputs define where the Bitcoins are going. Each transaction must have one or more outputs. Why would anyone have more than one output? An exchange may batch transactions, for example, and pay out a lot of people at once instead of generating a single transaction for every single person that requests Bitcoins.

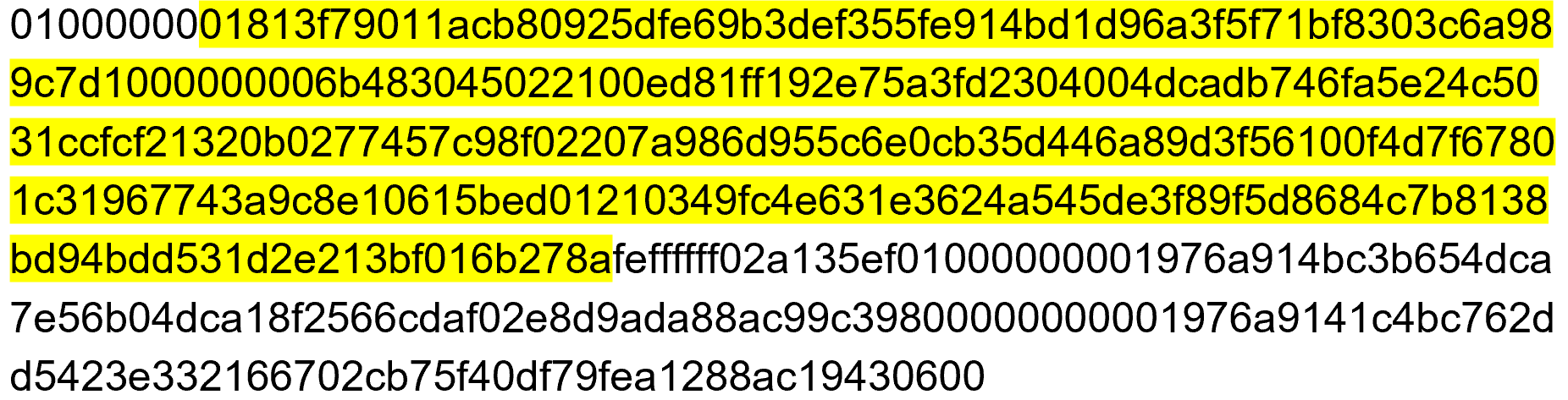

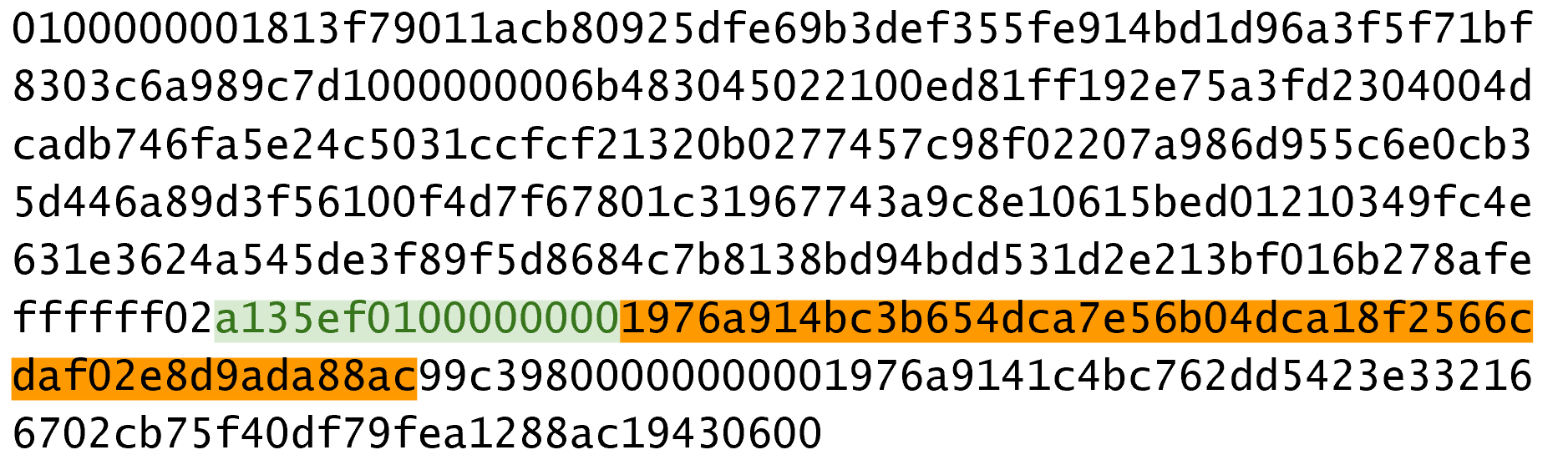

Like inputs, the outputs serialization starts with how many outputs there are as a varint as shown in Figure 5-6.

Figure 5-6. Number of Outputs

Each output has two fields: Amount and ScriptPubKey. Amount is the amount of Bitcoin being assigned and is specified in satoshis, or 1/100,000,000th of a Bitcoin. This allows us to divide Bitcoin very finely, down to 1/300th of a penny in USD terms as of this writing. The absolute maximum for the amount is the asymptotic limit of Bitcoin (21 million Bitcoins) in satoshis, which is 2,100,000,000,000,000 (2100 trillion) satoshis. This number is greater than 232 (4.3 billion or so) and is thus stored in 64 bits, or 8 bytes. Amount is serialized in Little-Endian.

ScriptPubKey, like ScriptSig, has to do with Bitcoin’s smart contract language Script. Think of ScriptPubKey as the locked box that can only be opened by the holder of the key. ScriptPubKey can be thought of as a one-way safe that can receive deposits from anyone, but can only be opened by the owner of the safe. We’ll explore what this is in more detail in Chapter 6. Like ScriptSig, ScriptPubKey is a variable-length field and is preceded by the length of the field in a varint.

An output field look like Figure 5-7:

Figure 5-7. Output Fields, Amount and ScriptPubKey. This one is at index 0.

We can now start coding the TxOut class:

classTxOut:def__init__(self,amount,script_pubkey):self.amount=amountself.script_pubkey=script_pubkeydef__repr__(self):return'{}:{}'.format(self.amount,self.script_pubkey)

Exercise 3

Write the outputs parsing part of the parse method in Tx and the parse method for TxOut.

Locktime

Locktime is a way to time-delay a transaction. A transaction with a Locktime of 600,000 cannot go into the blockchain until block 600,000. This was originally construed as a way to do “high frequency trades” (see Sequence and Locktime), which turned out to be insecure. If the Locktime is greater or equal to 500,000,000, Locktime is a UNIX timestamp. If Locktime is less than 500,000,000, it is a block number. This way, transactions can be signed, but unspendable until a certain point in UNIX time or block height.

The serialization is in Little-Endian and 4-bytes (Figure 5-8).

Figure 5-8. Locktime

The main problem with using Locktime is that the recipient of the transaction has no certainty that the transaction will be good when the Locktime comes. This is similar to a post-dated bank check, which has the possibility of bouncing. The sender can spend the inputs prior to the Locktime transaction getting into the blockchain invalidating the transaction at Locktime.

The uses before BIP0065 were limited.

BIP0065 introduced OP_CHECKLOCKTIMEVERIFY which makes Locktime more useful by making an output unspendable until a certain Locktime.

Exercise 4

Write the Locktime parsing part of the parse method in Tx.

Exercise 5

What is the ScriptSig from the second input, ScriptPubKey from the first output and the amount of the second output for this transaction?

010000000456919960ac691763688d3d3bcea9ad6ecaf875df5339e148a1fc61c6ed7a069e0100 00006a47304402204585bcdef85e6b1c6af5c2669d4830ff86e42dd205c0e089bc2a821657e951 c002201024a10366077f87d6bce1f7100ad8cfa8a064b39d4e8fe4ea13a7b71aa8180f012102f0 da57e85eec2934a82a585ea337ce2f4998b50ae699dd79f5880e253dafafb7feffffffeb8f51f4 038dc17e6313cf831d4f02281c2a468bde0fafd37f1bf882729e7fd3000000006a473044022078 99531a52d59a6de200179928ca900254a36b8dff8bb75f5f5d71b1cdc26125022008b422690b84 61cb52c3cc30330b23d574351872b7c361e9aae3649071c1a7160121035d5c93d9ac96881f19ba 1f686f15f009ded7c62efe85a872e6a19b43c15a2937feffffff567bf40595119d1bb8a3037c35 6efd56170b64cbcc160fb028fa10704b45d775000000006a47304402204c7c7818424c7f7911da 6cddc59655a70af1cb5eaf17c69dadbfc74ffa0b662f02207599e08bc8023693ad4e9527dc42c3 4210f7a7d1d1ddfc8492b654a11e7620a0012102158b46fbdff65d0172b7989aec8850aa0dae49 abfb84c81ae6e5b251a58ace5cfeffffffd63a5e6c16e620f86f375925b21cabaf736c779f88fd 04dcad51d26690f7f345010000006a47304402200633ea0d3314bea0d95b3cd8dadb2ef79ea833 1ffe1e61f762c0f6daea0fabde022029f23b3e9c30f080446150b23852028751635dcee2be669c 2a1686a4b5edf304012103ffd6f4a67e94aba353a00882e563ff2722eb4cff0ad6006e86ee20df e7520d55feffffff0251430f00000000001976a914ab0c0b2e98b1ab6dbf67d4750b0a56244948 a87988ac005a6202000000001976a9143c82d7df364eb6c75be8c80df2b3eda8db57397088ac46 430600

Coding Transactions

We’ve parsed the transaction, now we want to do the opposite, which is serializing the transaction.

Let’s start with TxOut:

classTxOut:...defserialize(self):'''Returns the byte serialization of the transaction output'''result=int_to_little_endian(self.amount,8)result+=self.script_pubkey.serialize()returnresult

We can proceed to TxIn:

classTxIn:...defserialize(self):'''Returns the byte serialization of the transaction input'''result=self.prev_tx[::-1]result+=int_to_little_endian(self.prev_index,4)result+=self.script_sig.serialize()result+=int_to_little_endian(self.sequence,4)returnresult

Lastly, we can serialize Tx:

classTx:...defserialize(self):'''Returns the byte serialization of the transaction'''result=int_to_little_endian(self.version,4)result+=encode_varint(len(self.tx_ins))fortx_ininself.tx_ins:result+=tx_in.serialize()result+=encode_varint(len(self.tx_outs))fortx_outinself.tx_outs:result+=tx_out.serialize()result+=int_to_little_endian(self.locktime,4)returnresult

We’ve used the serialize methods of both TxIn and TxOut to serialize Tx.

Note that the transaction fee is not specified anywhere! This is because the fee is an implied amount. Fee is the total of the inputs amounts minus the total of the output amounts.

Transaction Fee

One of the consensus rules of Bitcoin is that for any non-Coinbase transactions (more on Coinbase transactions in Chapter 8), the sum of the inputs have to be greater than or equal to the sum of the outputs. You may be wondering why the inputs and outputs can’t just be forced to be equal. This is because if every transaction had zero cost, there wouldn’t be any incentive for miners to include transactions in blocks (see Chapter 9). Fees are a way to incentivize miners to include transactions. Transactions not in blocks (so called mempool transactions) are not part of the blockchain and are not final.

The transaction fee is simply the sum of the inputs minus the sum of the outputs. This difference is what the miner gets to keep. As inputs don’t have an amount field, we have to look up the amount. This requires access to the blockchain, specifically the UTXO set. If you are not running a full node, this can be tricky, as you now need to trust some other entity to provide you with this information.

We are creating a new class to handle this, called TxFetcher:

classTxFetcher:cache={}@classmethoddefget_url(cls,testnet=False):iftestnet:return'http://testnet.programmingbitcoin.com'else:return'http://mainnet.programmingbitcoin.com'@classmethoddeffetch(cls,tx_id,testnet=False,fresh=False):iffreshor(tx_idnotincls.cache):url='{}/tx/{}.hex'.format(cls.get_url(testnet),tx_id)response=requests.get(url)try:raw=bytes.fromhex(response.text.strip())exceptValueError:raiseValueError('unexpected response: {}'.format(response.text))ifraw[4]==0:raw=raw[:4]+raw[6:]tx=Tx.parse(BytesIO(raw),testnet=testnet)tx.locktime=little_endian_to_int(raw[-4:])else:tx=Tx.parse(BytesIO(raw),testnet=testnet)iftx.id()!=tx_id:raiseValueError('not the same id: {} vs {}'.format(tx.id(),tx_id))cls.cache[tx_id]=txcls.cache[tx_id].testnet=testnetreturncls.cache[tx_id]

You may be wondering why we don’t get just the specific output for the transaction and instead get the entire transaction. This is because we don’t want to be trusting a third party! By getting the entire transaction, we can verify the transaction ID (hash256 of its contents) and be sure that we are indeed getting the transaction we asked for. This is impossible unless we receive the entire transaction.

Why We Minimize Trusting Third Parties

As Nick Szabo eloquently wrote in his seminal essay “Trusted Third Parties are Security Holes” (https://nakamotoinstitute.org/trusted-third-parties/), trusting third parties to provide correct data is not a good security practice. The third party may be behaving well now, but you never know when they may get hacked, may have an employee go rogue or start implementing policies that are against your interests. Part of what makes Bitcoin secure is in not trusting, but verifying data that we’re given.

We can now create the appropriate method in TxIn to fetch the previous transaction and methods to get the previous transaction output’s amount and ScriptPubkey (the latter to be used in Chapter 6):

classTxIn:...deffetch_tx(self,testnet=False):returnTxFetcher.fetch(self.prev_tx.hex(),testnet=testnet)defvalue(self,testnet=False):'''Get the outpoint value by looking up the tx hashReturns the amount in satoshi'''tx=self.fetch_tx(testnet=testnet)returntx.tx_outs[self.prev_index].amountdefscript_pubkey(self,testnet=False):'''Get the ScriptPubKey by looking up the tx hashReturns a Script object'''tx=self.fetch_tx(testnet=testnet)returntx.tx_outs[self.prev_index].script_pubkey

Calculating the fee

Now that we have the amount method in TxIn which lets us access how many Bitcoins are in each transaction input, we can calculate the fee for a transaction.

Exercise 6

Write the fee method for the Tx class.

Conclusion

We’ve covered exactly how to parse and serialize transactions along with the fields mean. There are two fields that require more explanation and they are both related to Bitcoin’s smart contract language, Script. To that topic we go in <chapter_script>>.