Learn How to Program Bitcoin from Scratch

Copyright © 2019 Jimmy Song. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://oreilly.com/safari). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or corporate@oreilly.com.

See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781492031499 for release details.

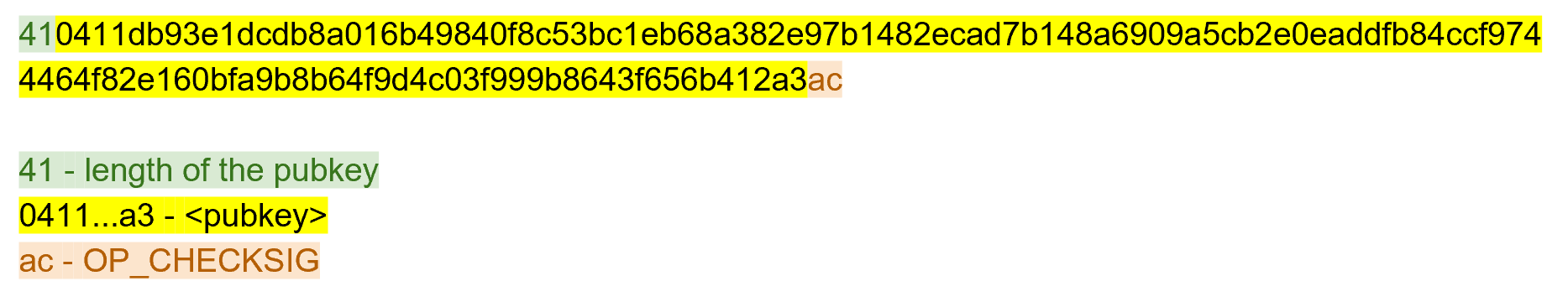

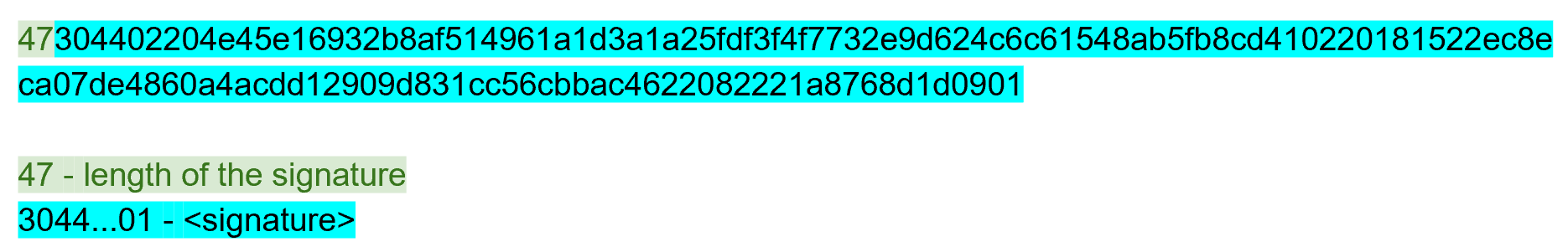

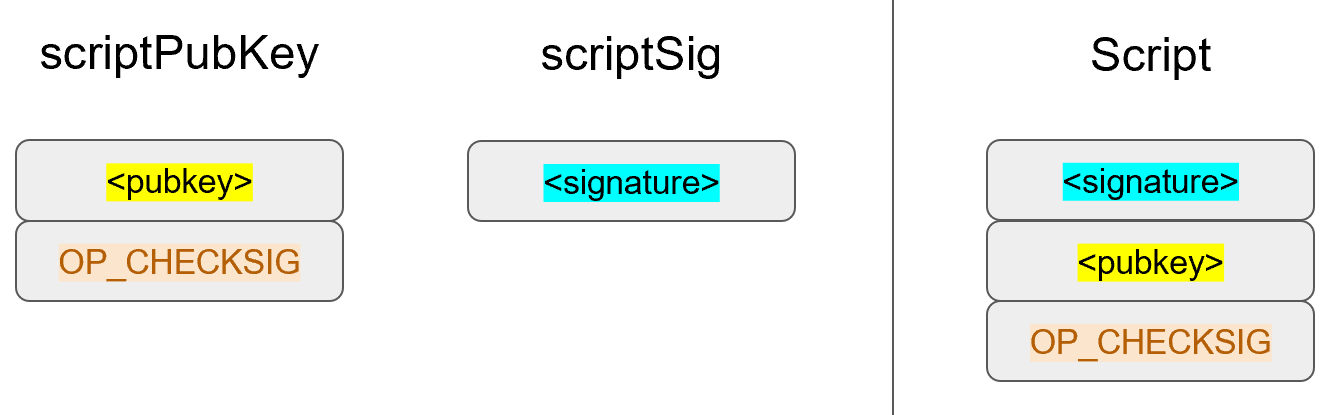

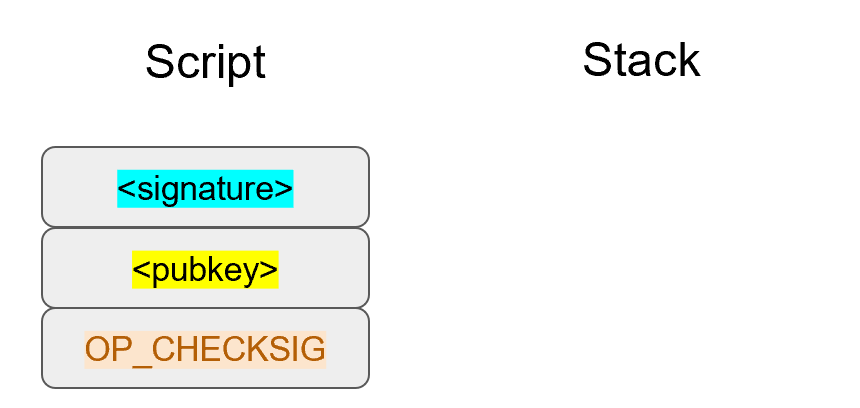

The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Programming Bitcoin, the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc.

The views expressed in this work are those of the author, and do not represent the publisher’s views. While the publisher and the author have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the author disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open source licenses or the intellectual property rights of others, it is your responsibility to ensure that your use thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights.

978-1-492-03149-9

[FILL IN]

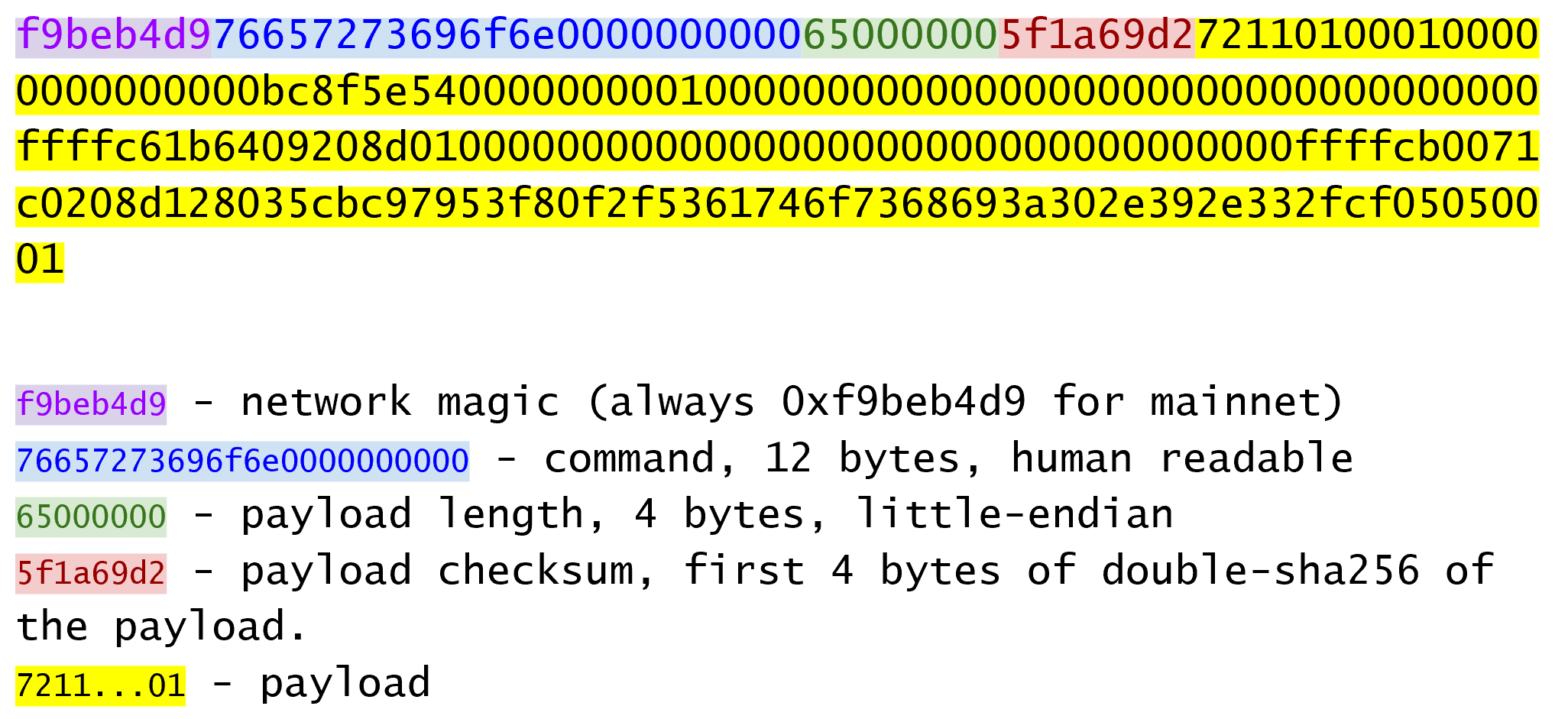

This book will teach you the technology of Bitcoin at a fundamental level. This book doesn’t cover monetary, economic or social dynamics of Bitcoin, but knowing how Bitcoin works under the hood should give you greater insight into what’s possible. There’s a tendency to hype Bitcoin and blockchain without really understanding what’s going on and this book is meant to be an antidote to that tendency.

After all, there are lots of books about Bitcoin, everything from the history of Bitcoin, the economic aspects to a technical description of Bitcoin. The aim of this book is to get you to understand Bitcoin by coding all of the components necessary for a Bitcoin library. The library is not meant to be exhaustive or efficient. The aim of the library is to help you learn.

This book is for programmers who want to learn how Bitcoin works by coding it themselves. You will learn Bitcoin by coding the “bare metal” stuff in a Bitcoin library you will create from scratch. This is not a reference book where you can look up the specification for a particular feature.

The material from this book has been largely taken from my two day seminar where I teach developers all about Bitcoin (see programmingblockchain.com).

The material has been refined many times as I’ve taught this material 20+ times and have taught 400+ people as of this writing.

By the time you’re done with the book, you’ll not only be able to create transactions, but be able to get all the data you need from peers and send the transaction over the network. Everything to accomplish this is covered including the math, the parsing, the network connectivity and block validation.

The prerequisites for this book are that you know programming and that you know Python in particular. The library itself is written in Python 3 and a lot of the exercises can be done in a controlled environment like a Jupyter notebook. An intermediate knowledge of Python is preferred, but even a beginner knowledge of Python is probably sufficient to get a lot of the concepts.

Some knowledge of math is required, especially for Chapters 1 and 2. These chapters introduce mathematical concepts probably not familiar to those that didn’t major in mathematics. Math knowledge around algebra-level should suffice to understand the new concepts and to code the exercises covered in those chapters.

General Computer Science knowledge like hash functions will come in handy, but are not strictly necessary to complete the exercises in this book.

This book is split into 14 chapters and built on top of one another. Each chapter is meant to build on the previous one as the Bitcoin library gets built from scratch all the way to the end.

Roughly speaking, Chapters 1-4 establish the mathematical tools that we need, Chapters 5-8 cover Transactions, which are the fundamental unit of Bitcoin and Chapters 9-12 cover Blocks and Networking. The last two chapters cover some advanced topics but don’t actually require you to write code.

Chapters 1 and 2 cover some math that we need. Finite Fields and Elliptic Curves are needed in order for us to understand Elliptic Curve Cryptography in Chapter 3. After we’ve established the Public Key Cryptography at the end of Chapter 3, we move towards implementing how the cryptographic primitives are stored and transmitted through parsing and serializing all the different classes that we established in Chapter 4.

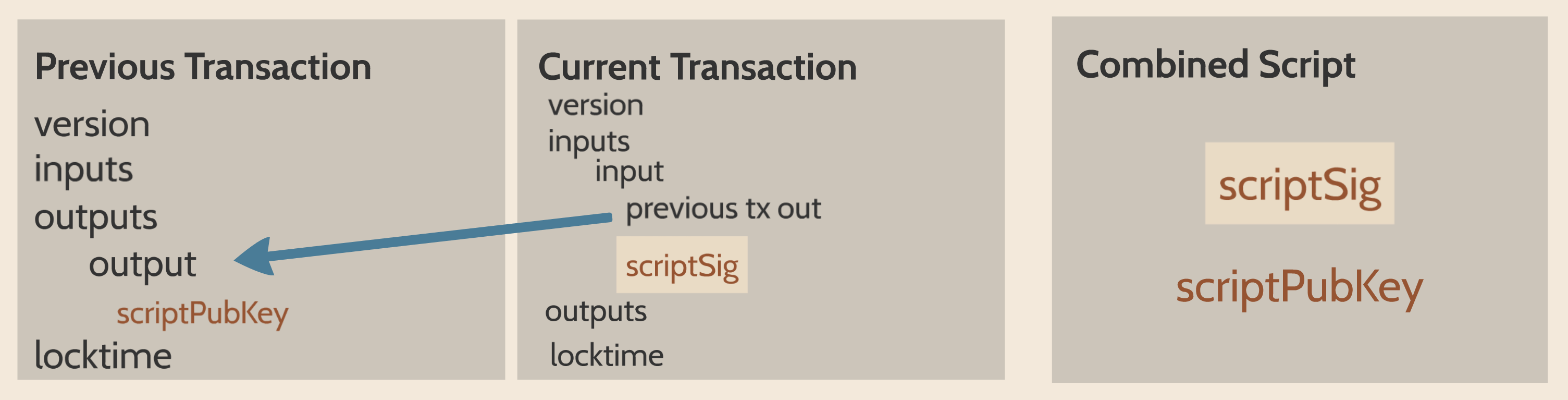

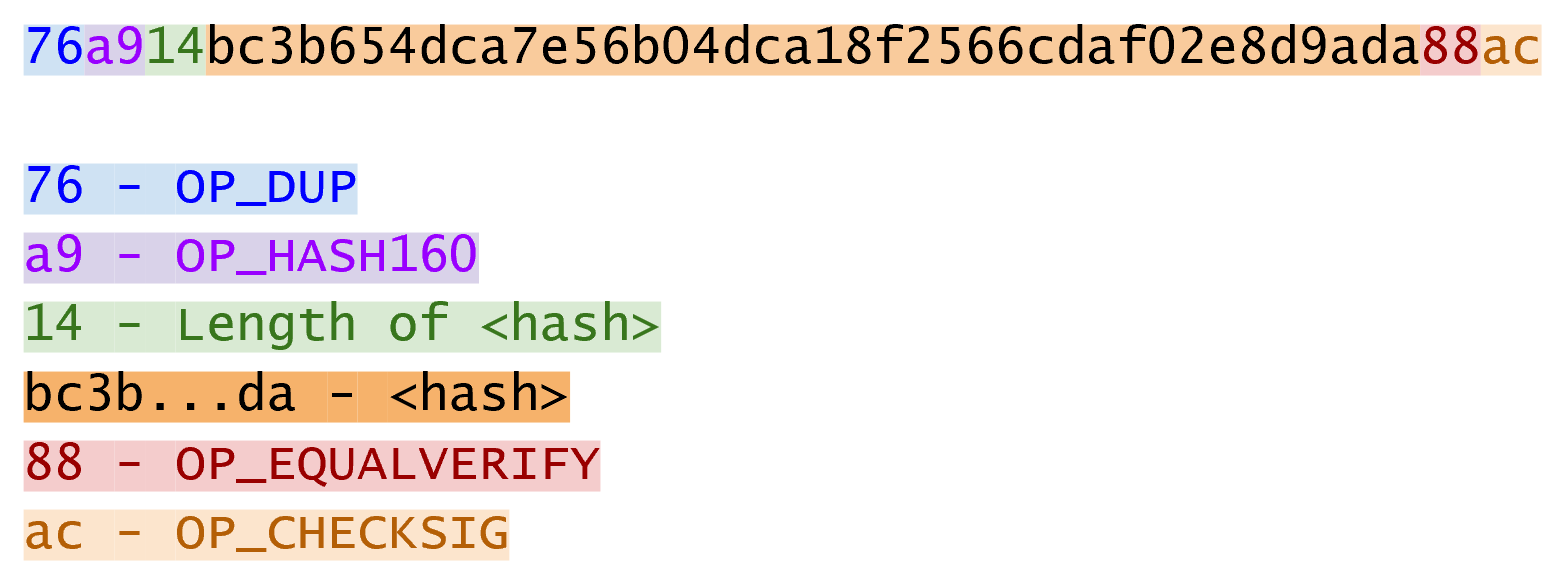

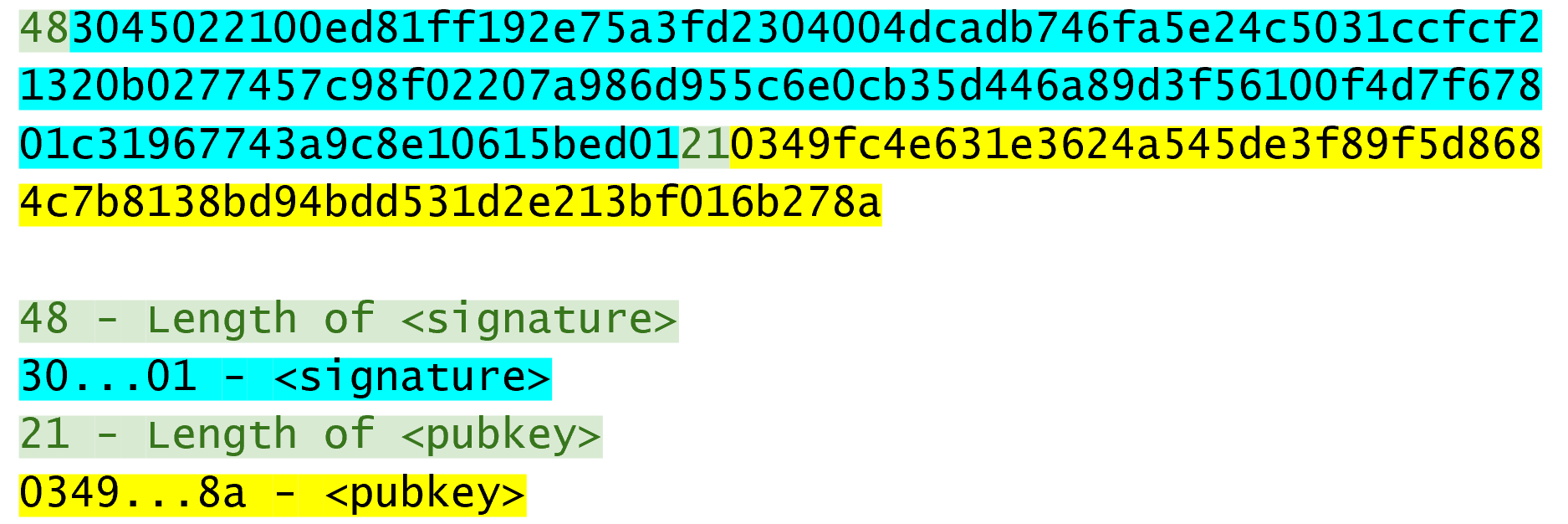

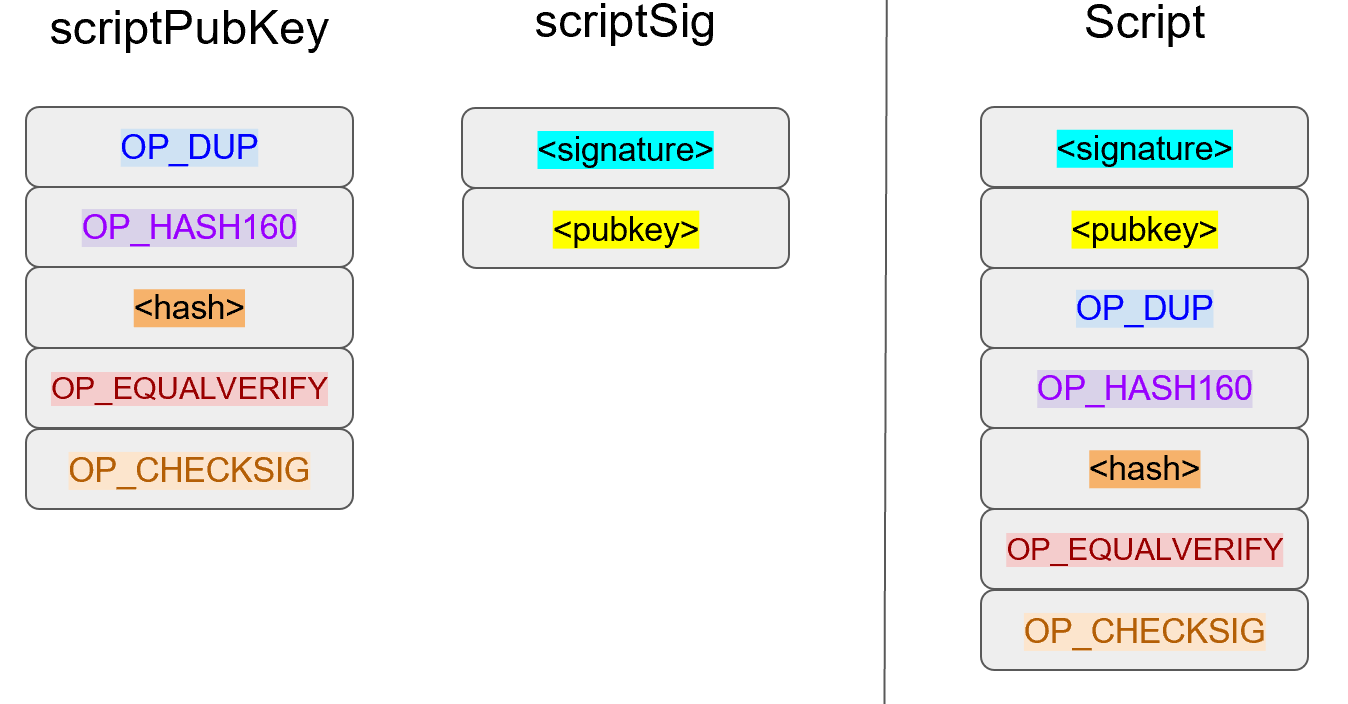

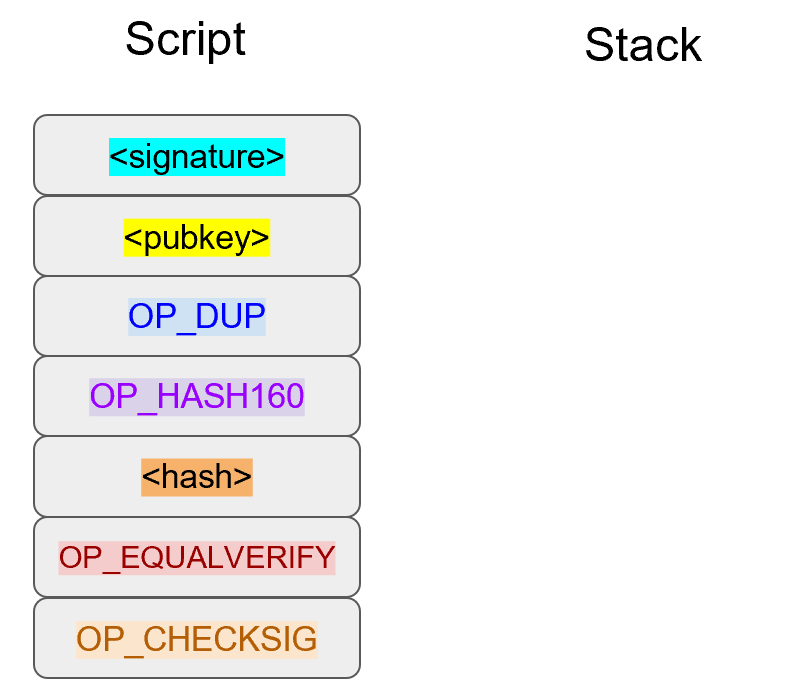

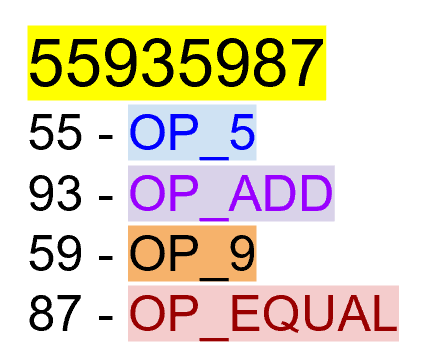

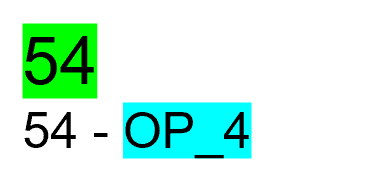

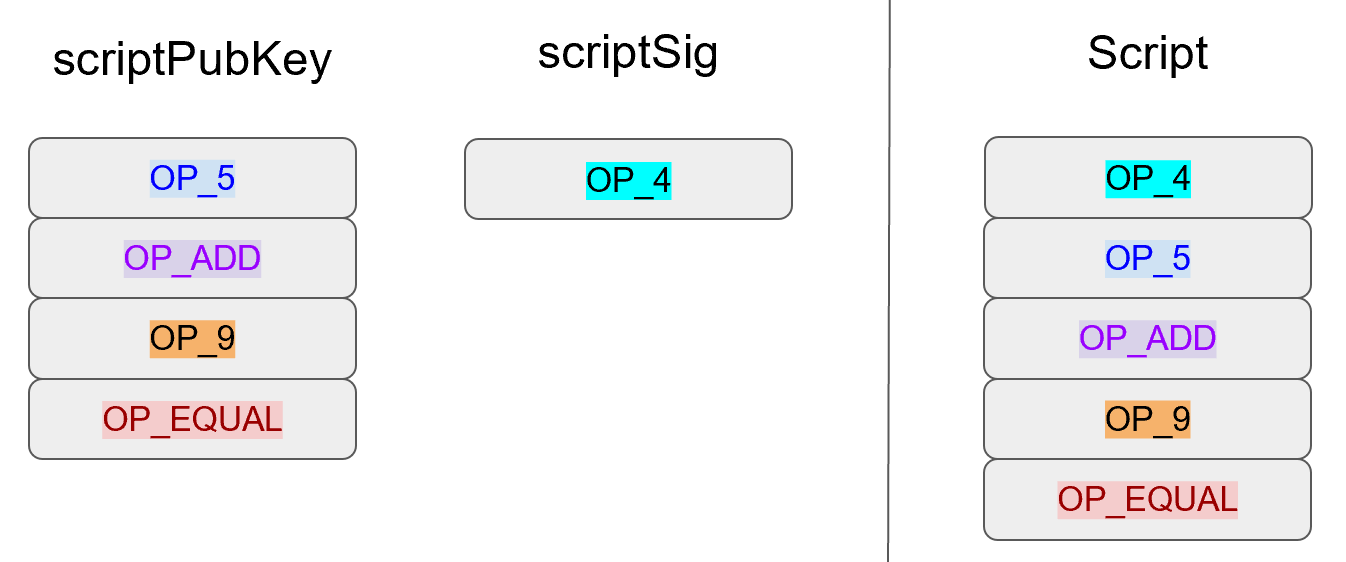

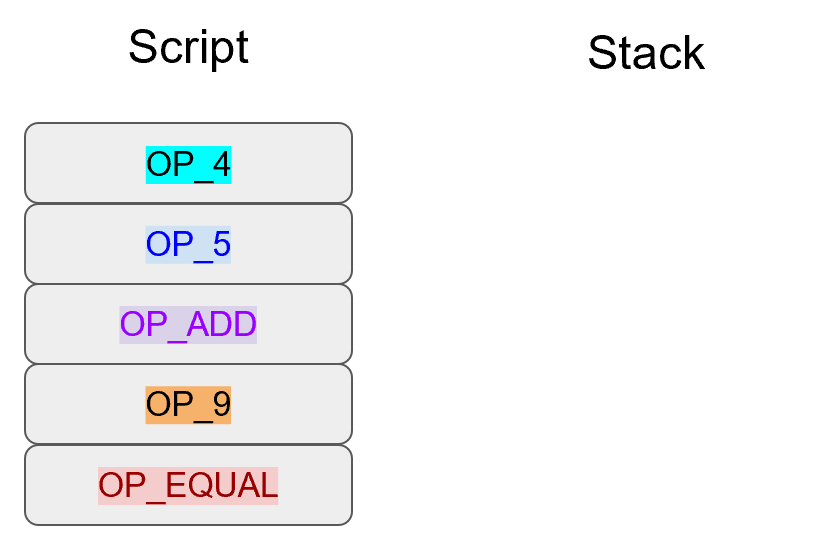

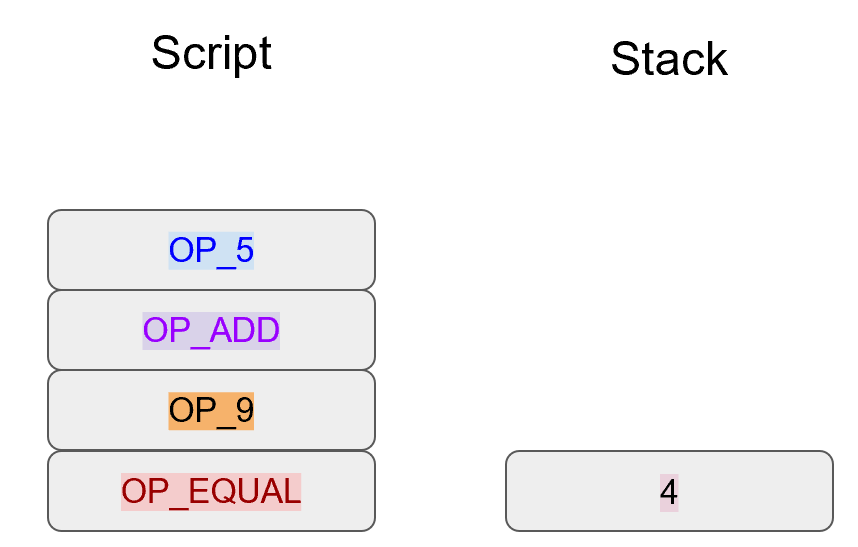

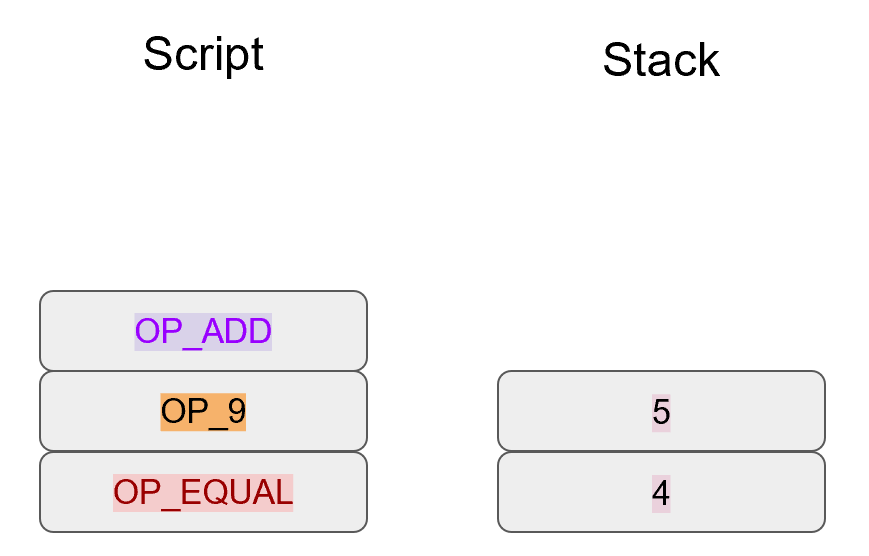

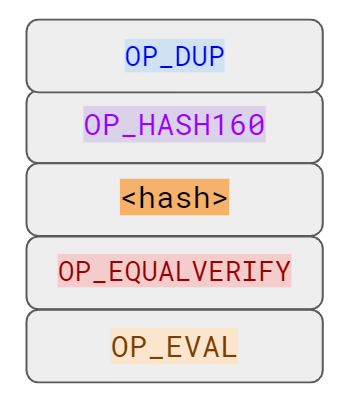

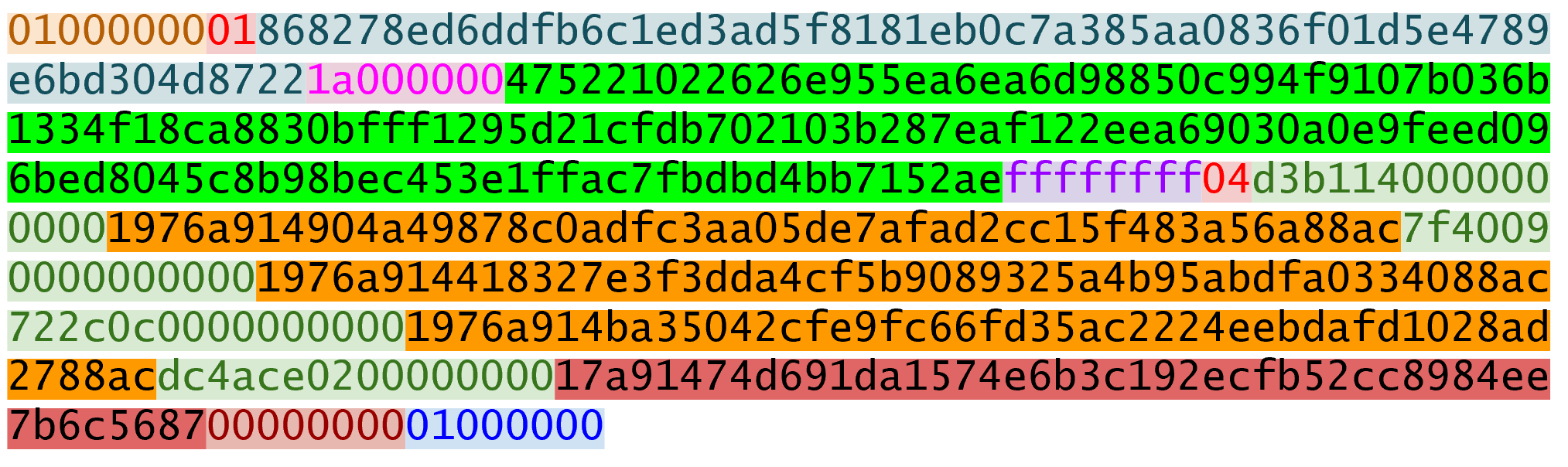

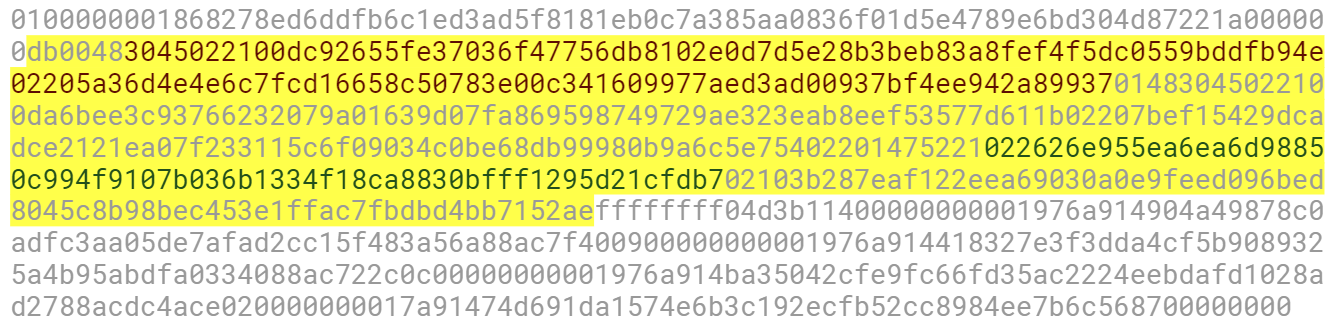

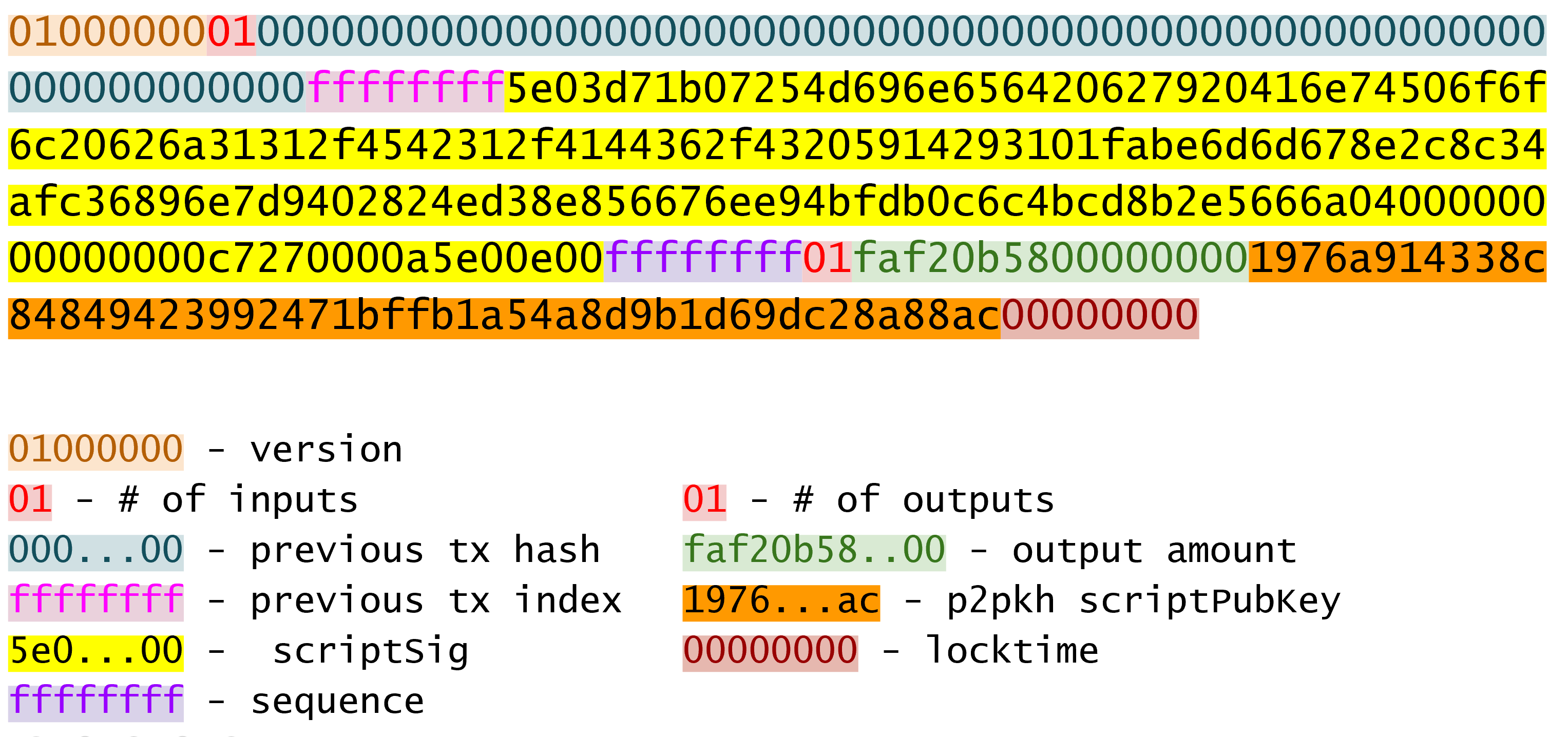

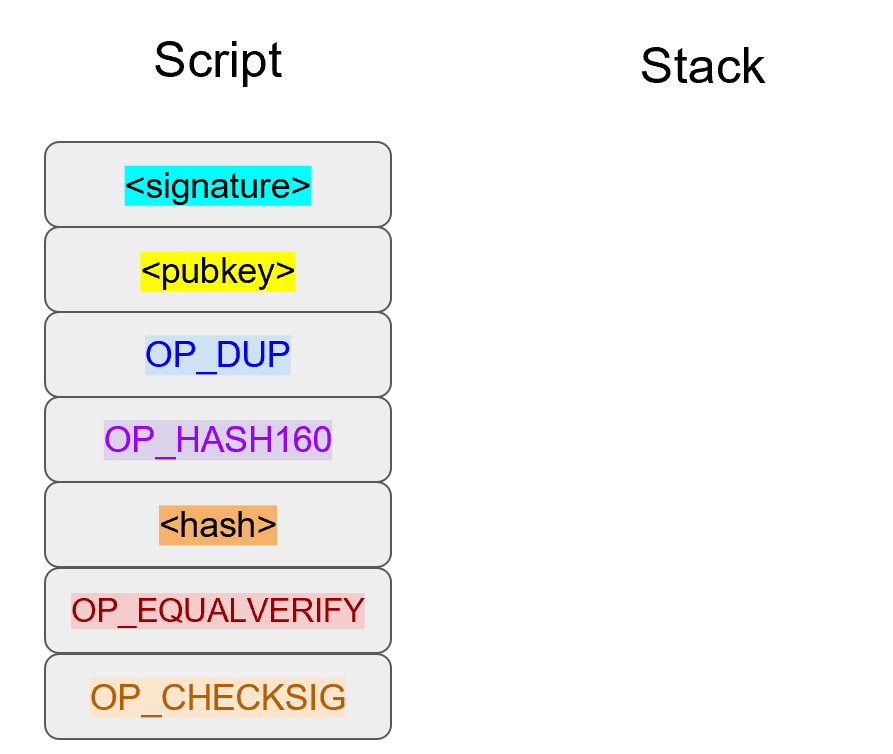

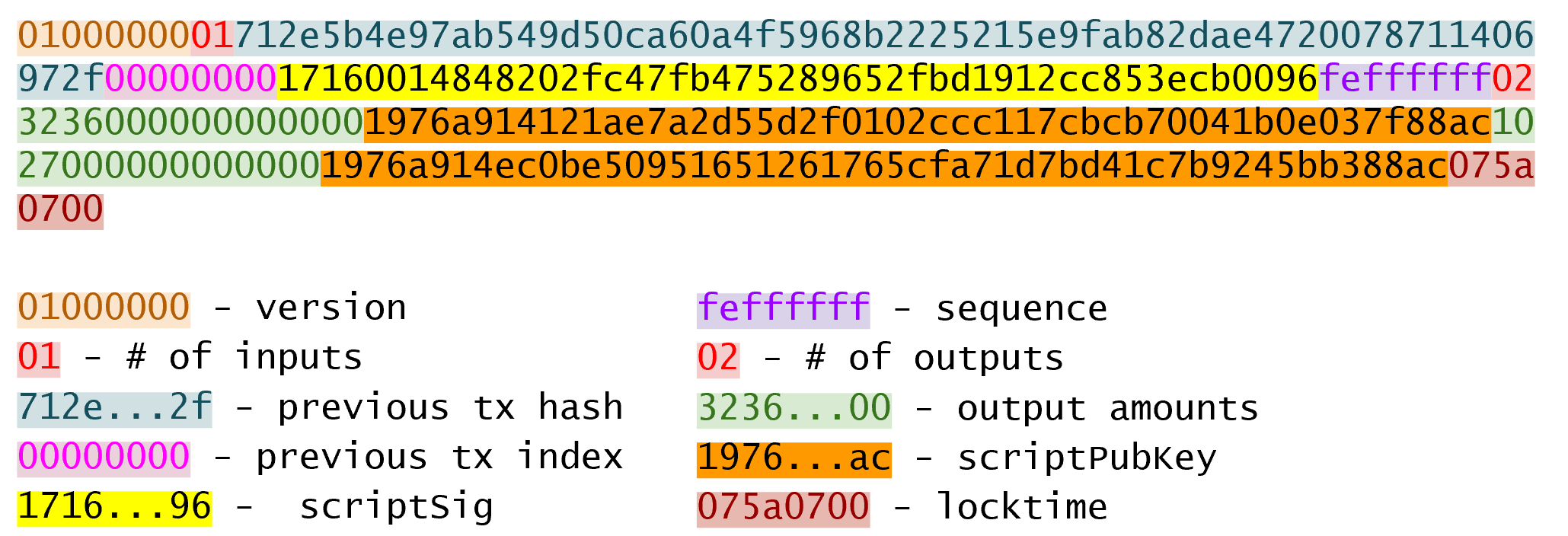

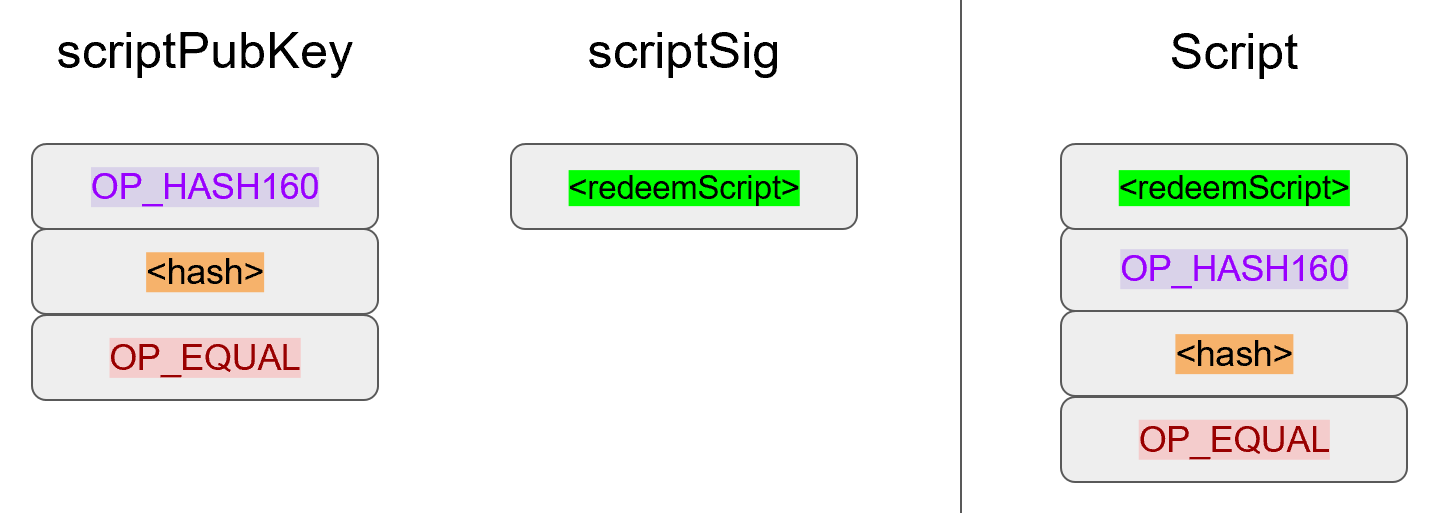

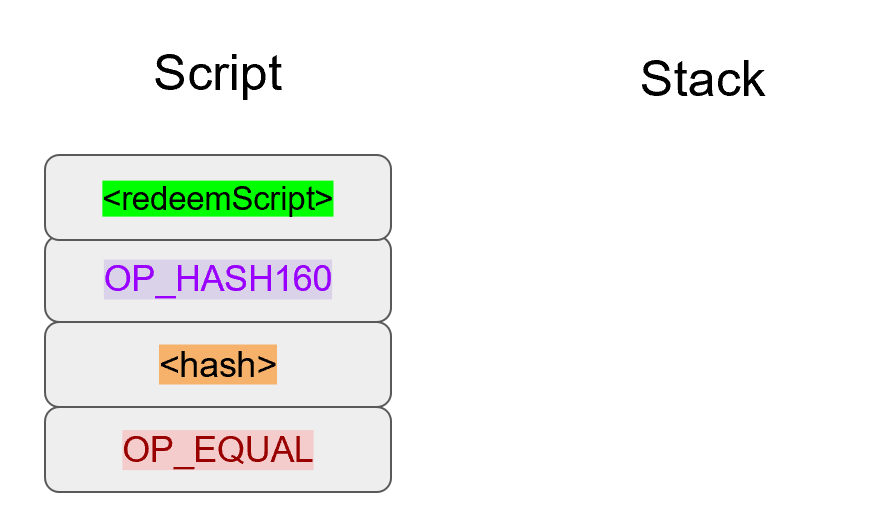

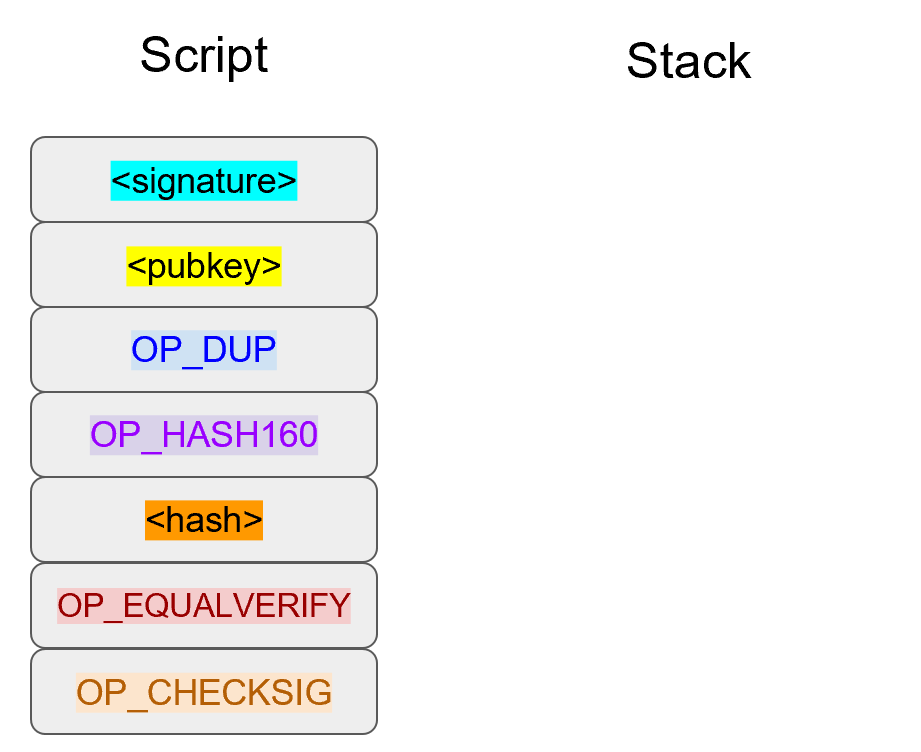

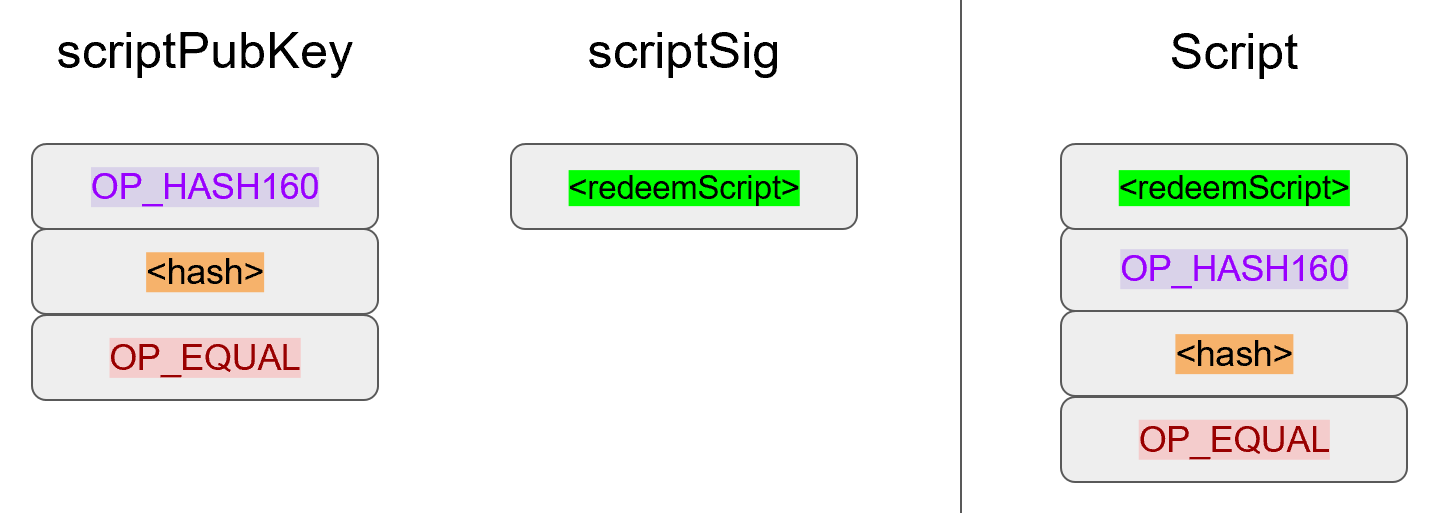

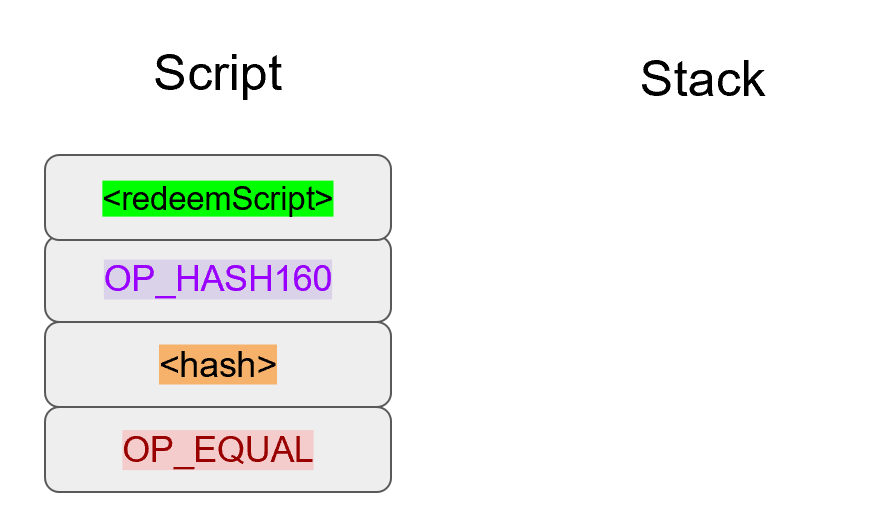

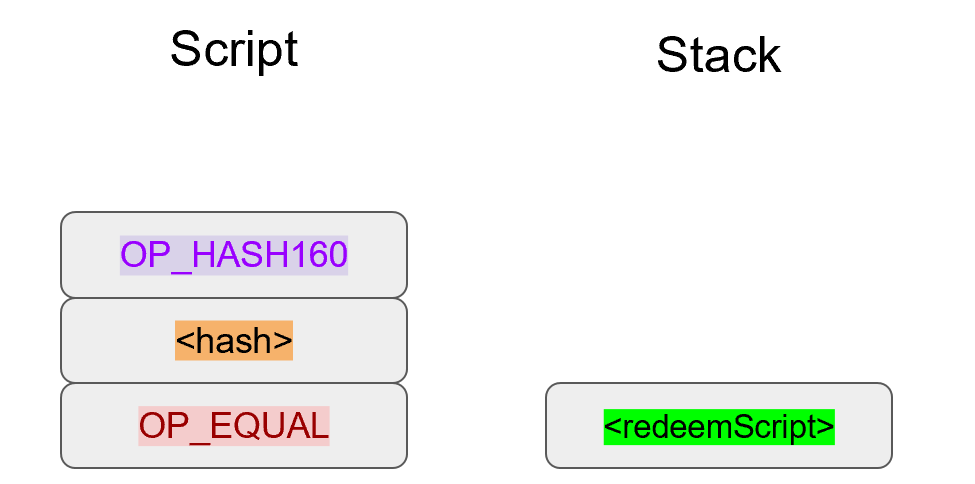

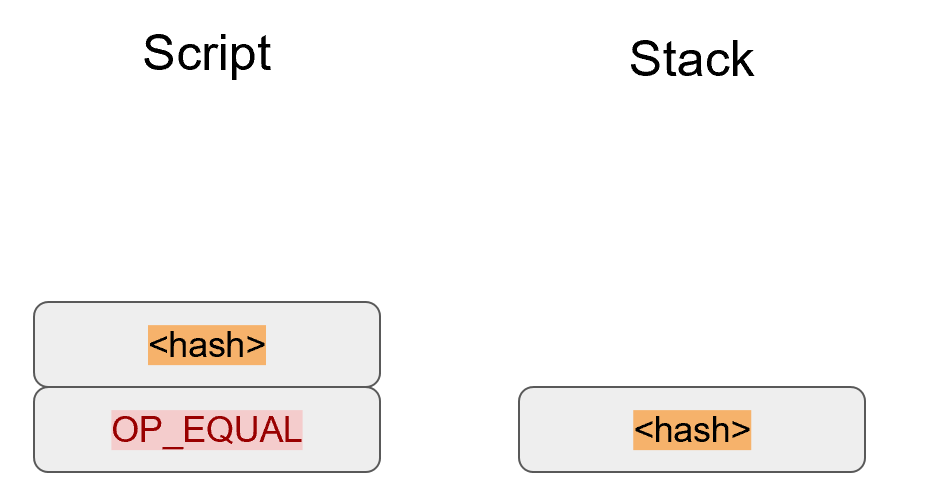

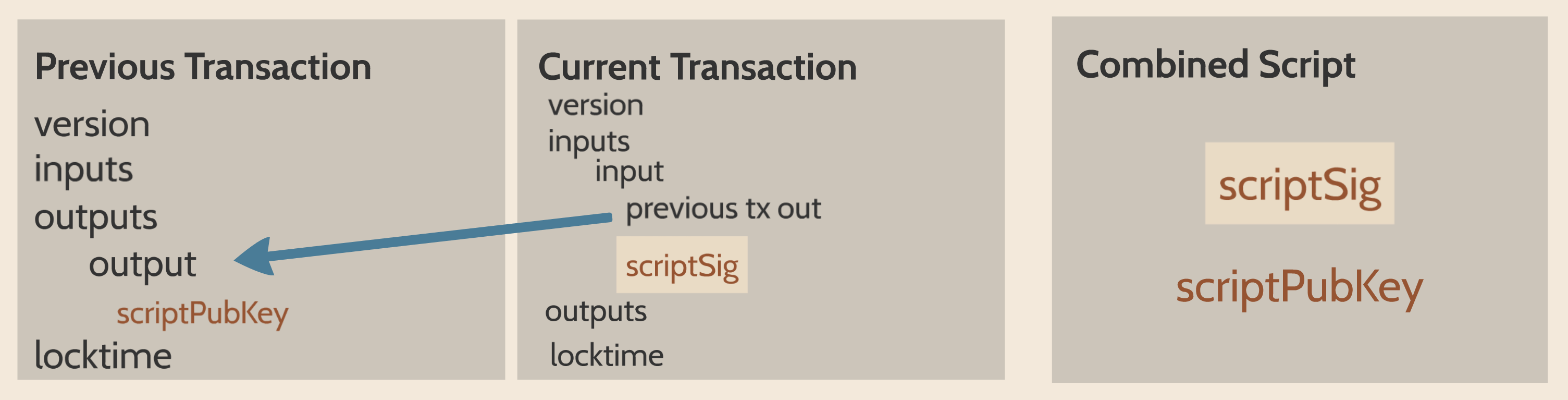

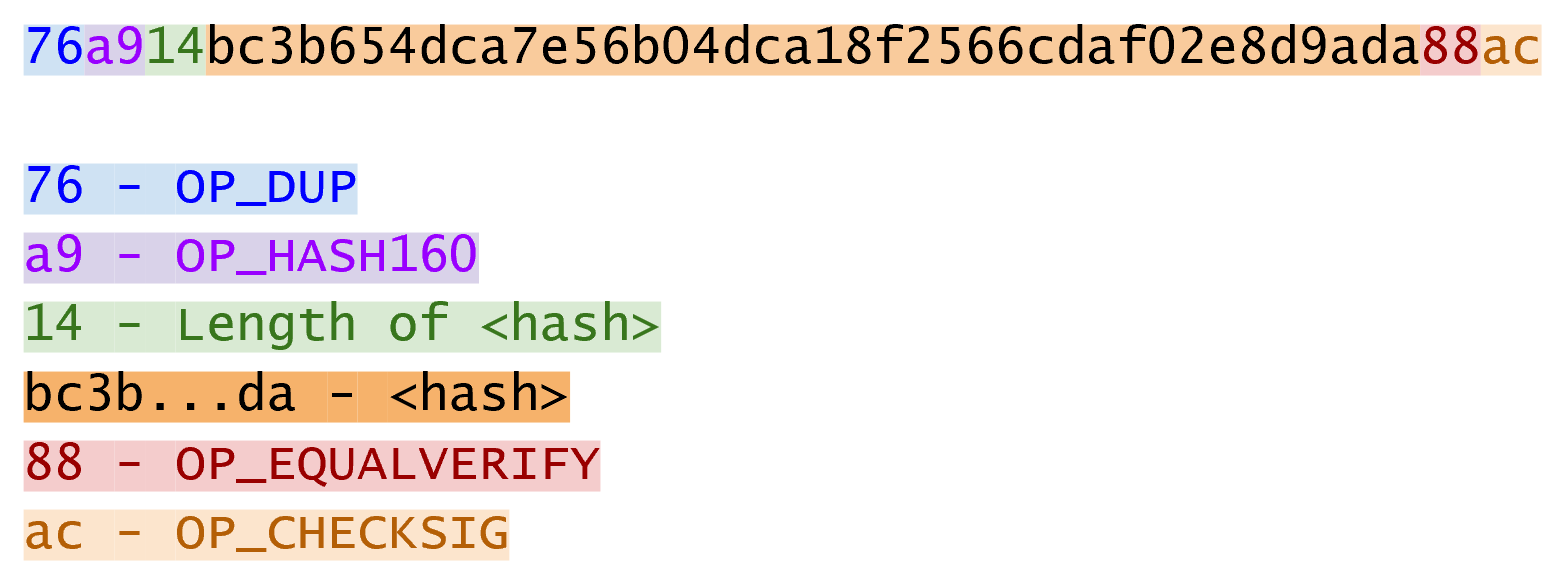

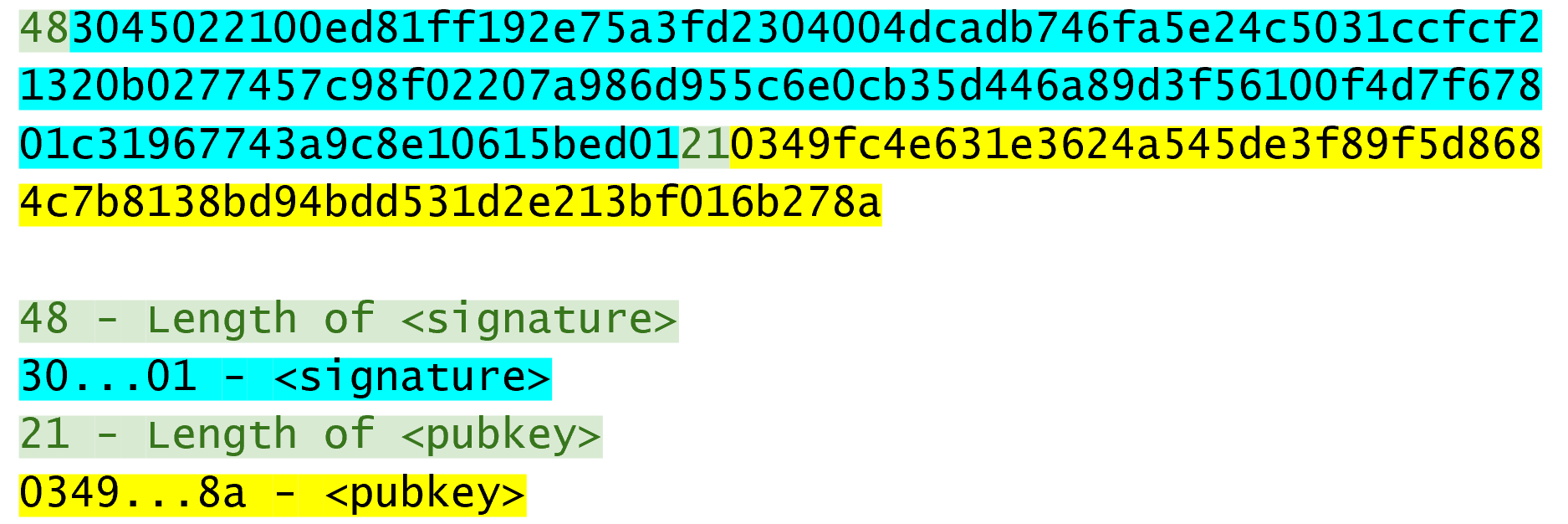

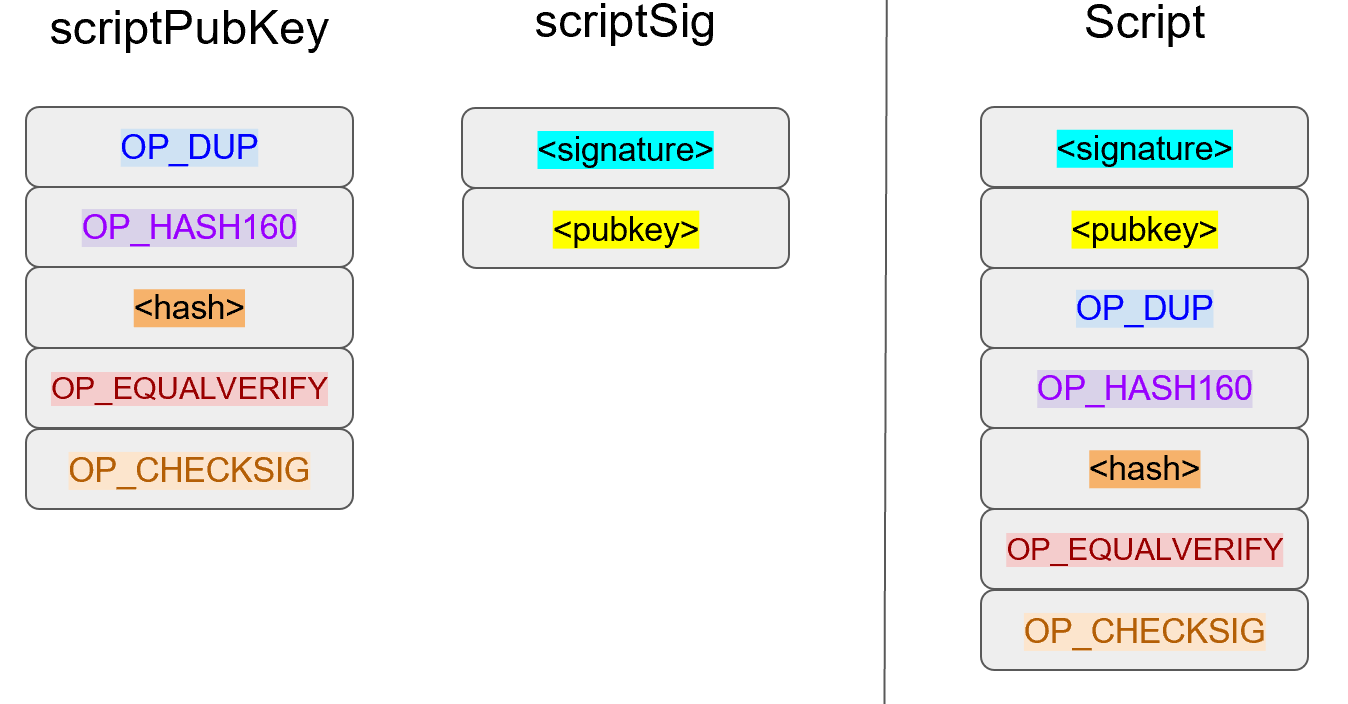

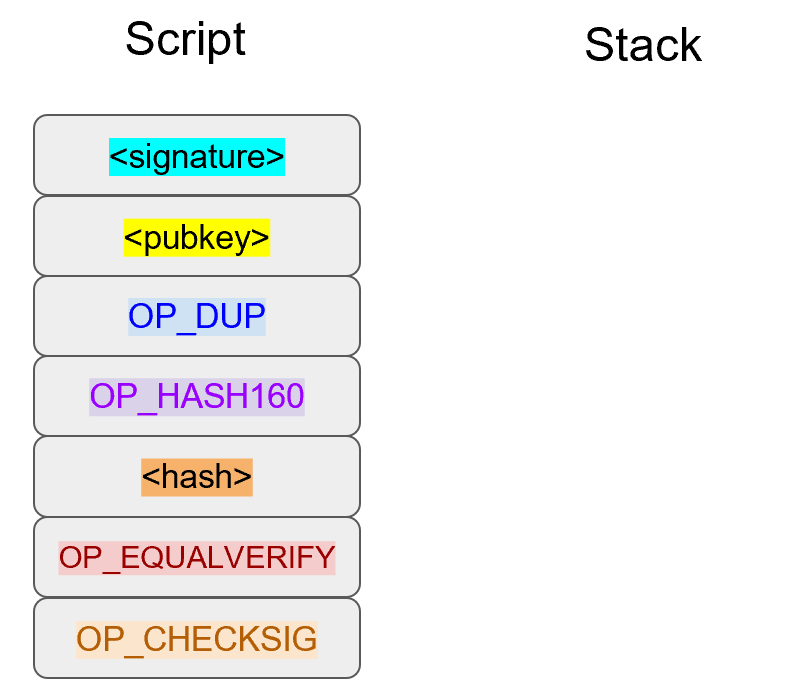

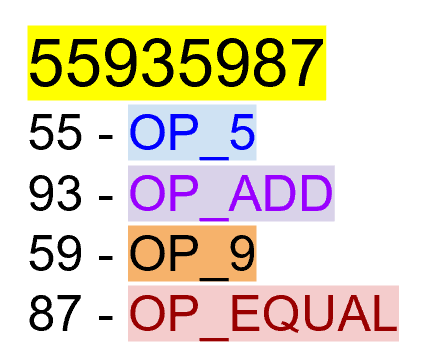

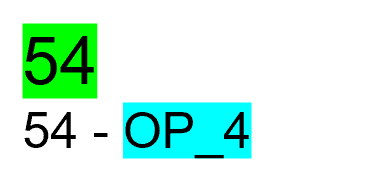

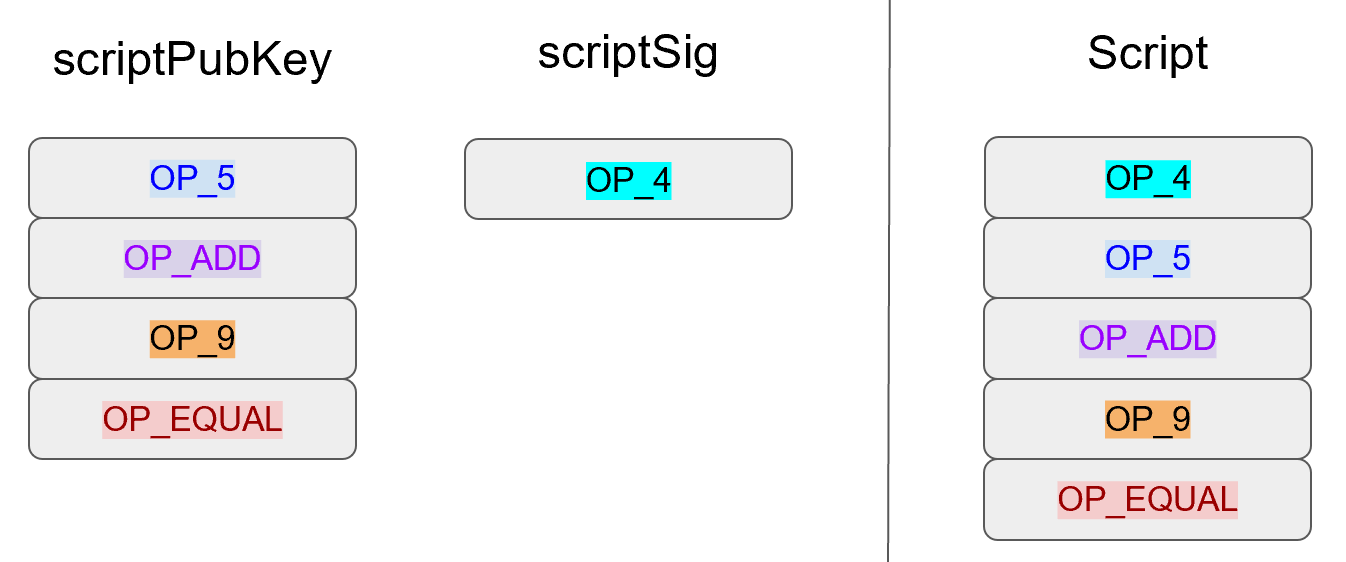

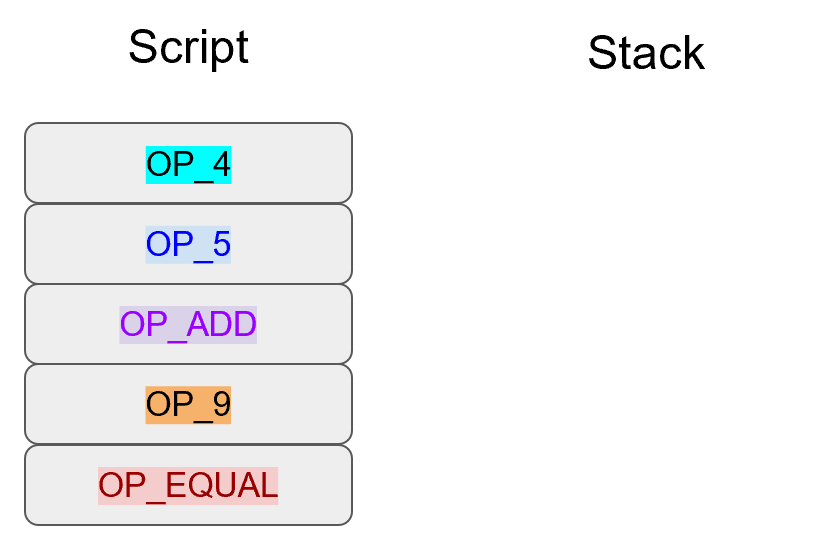

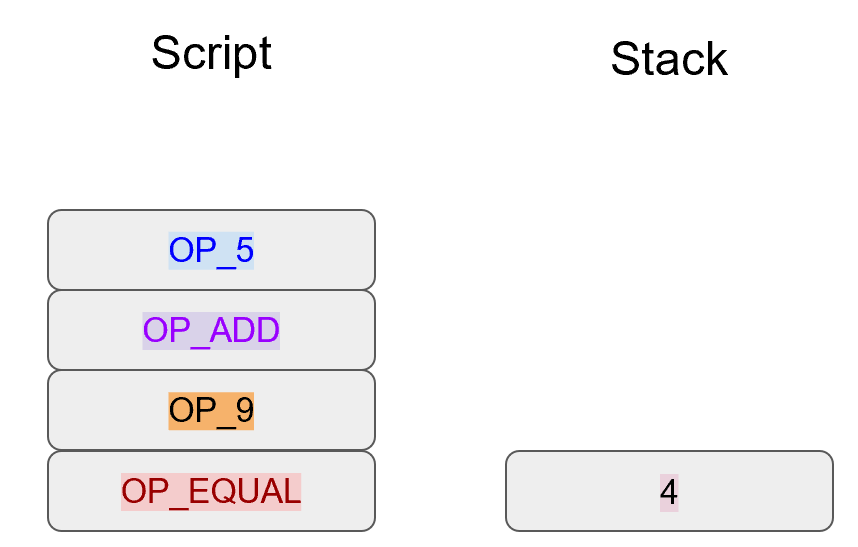

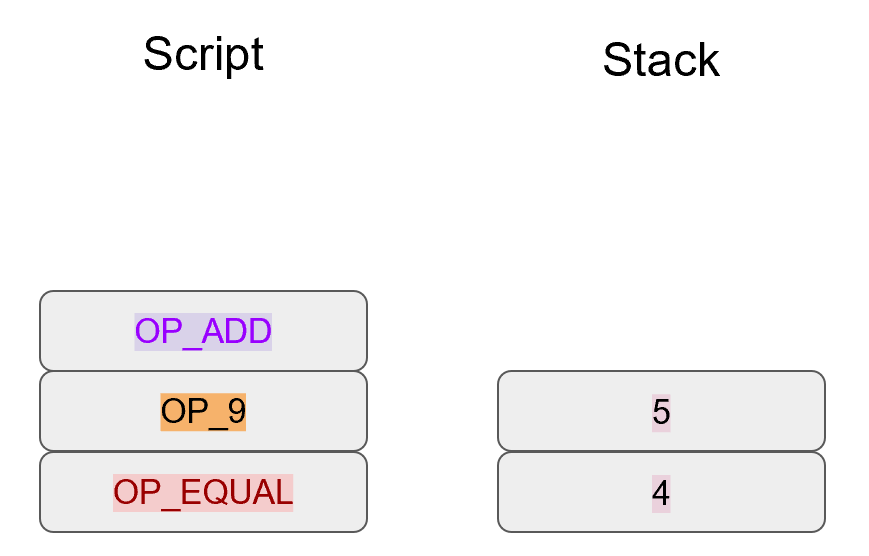

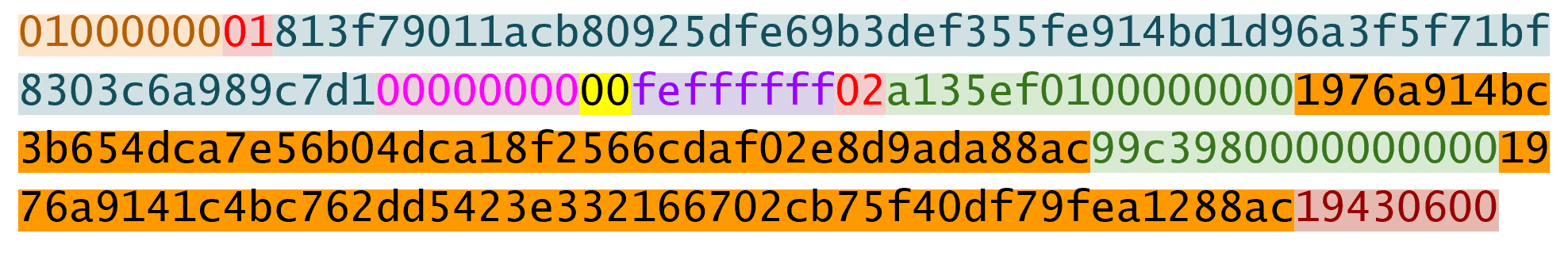

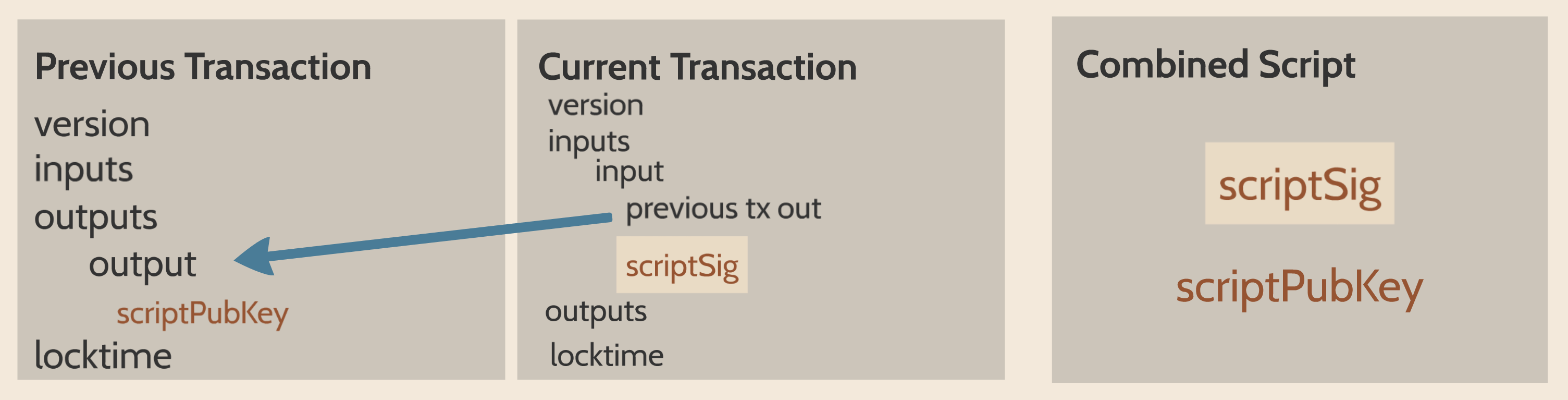

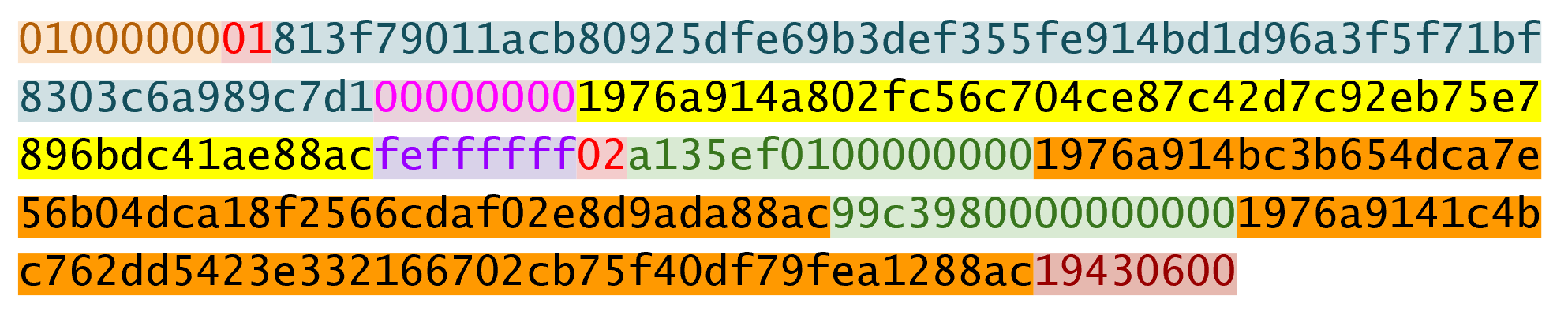

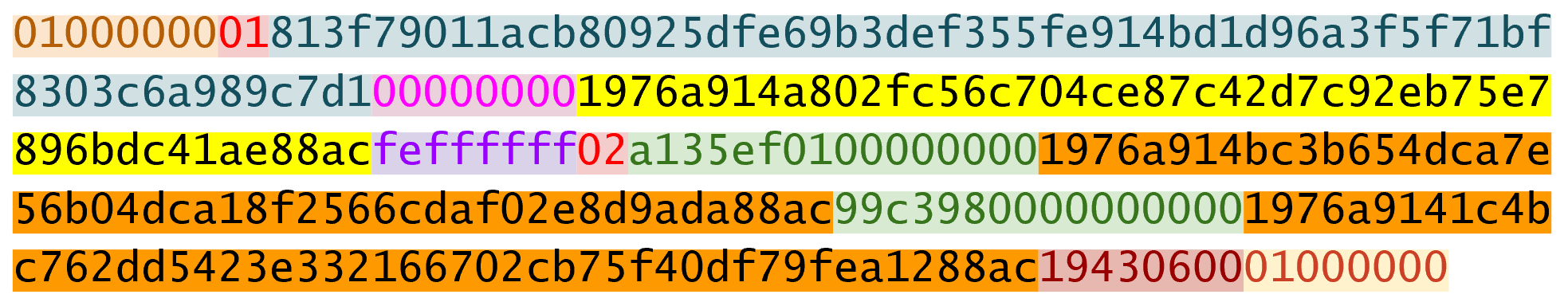

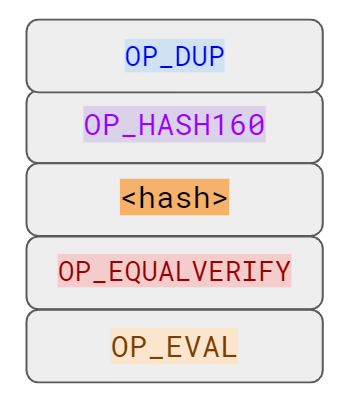

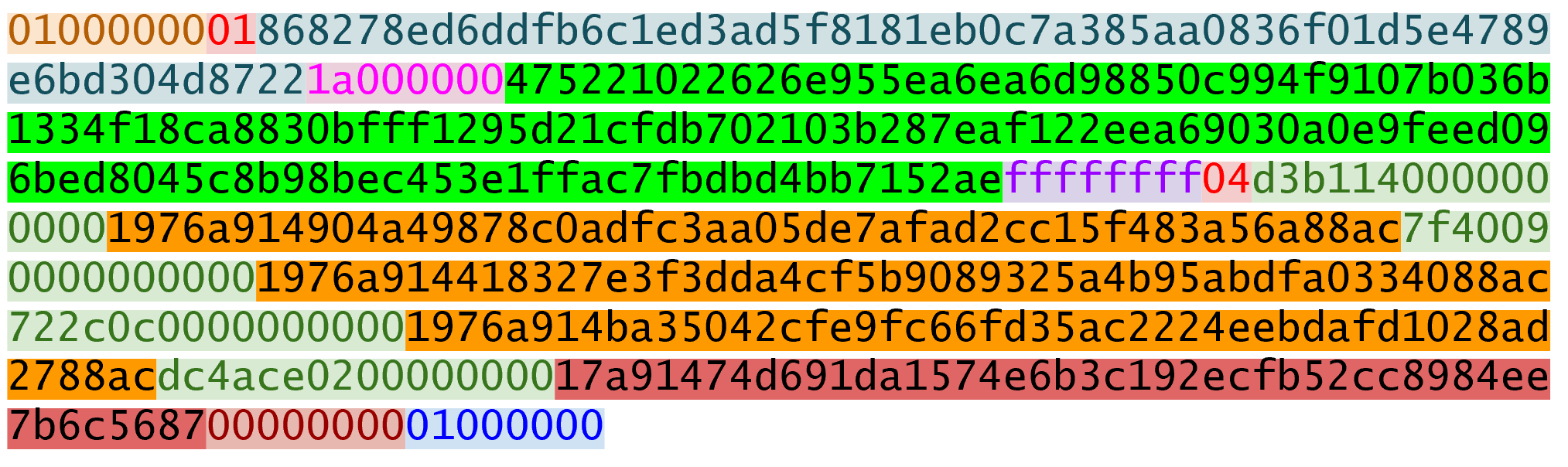

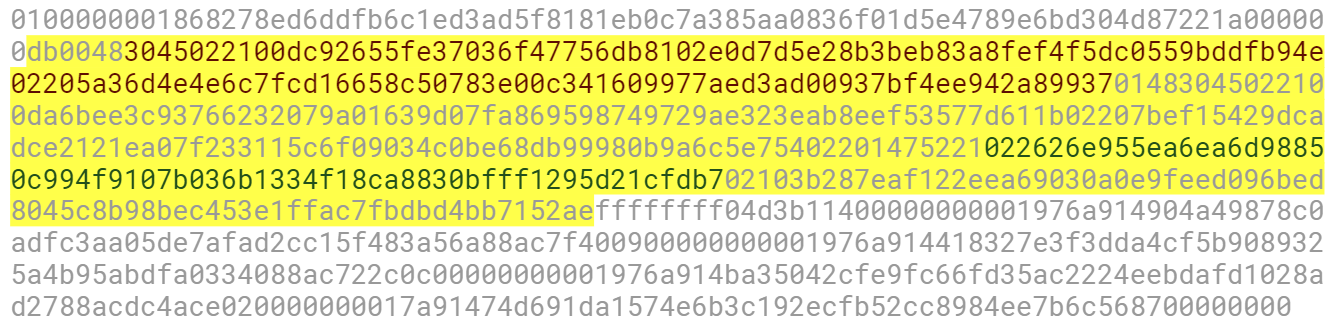

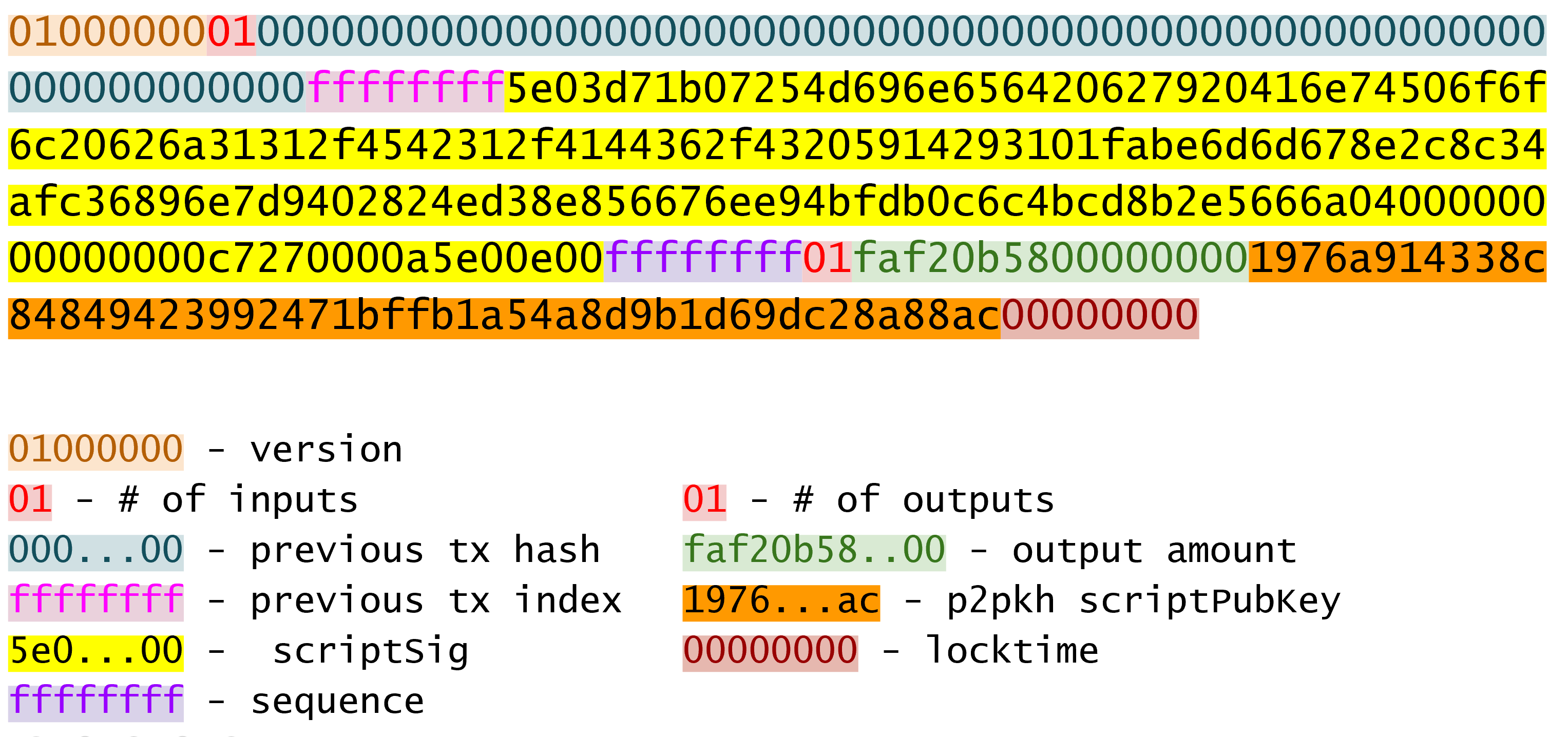

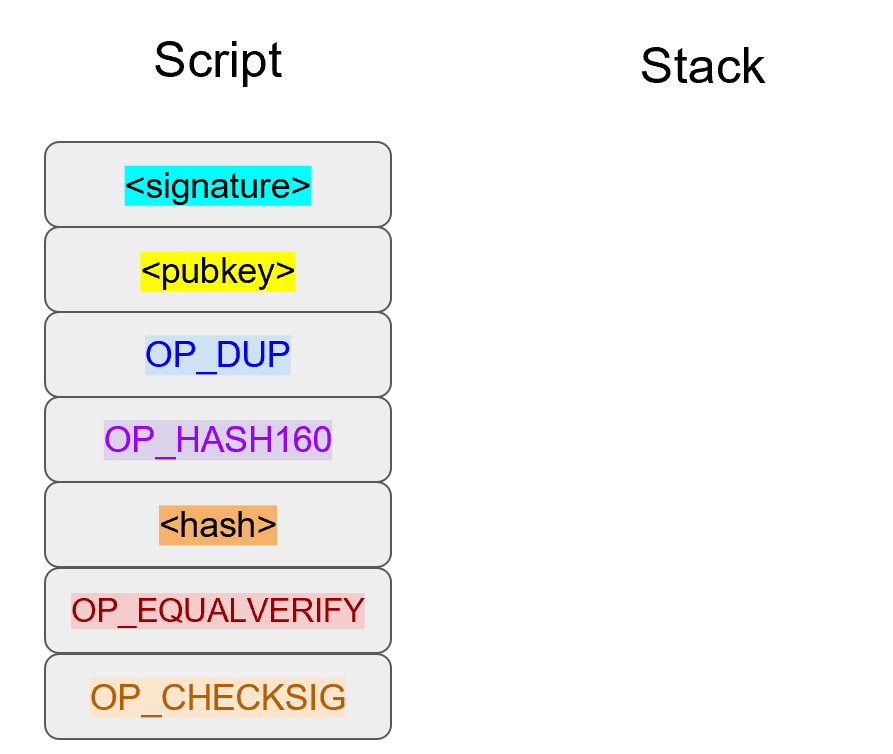

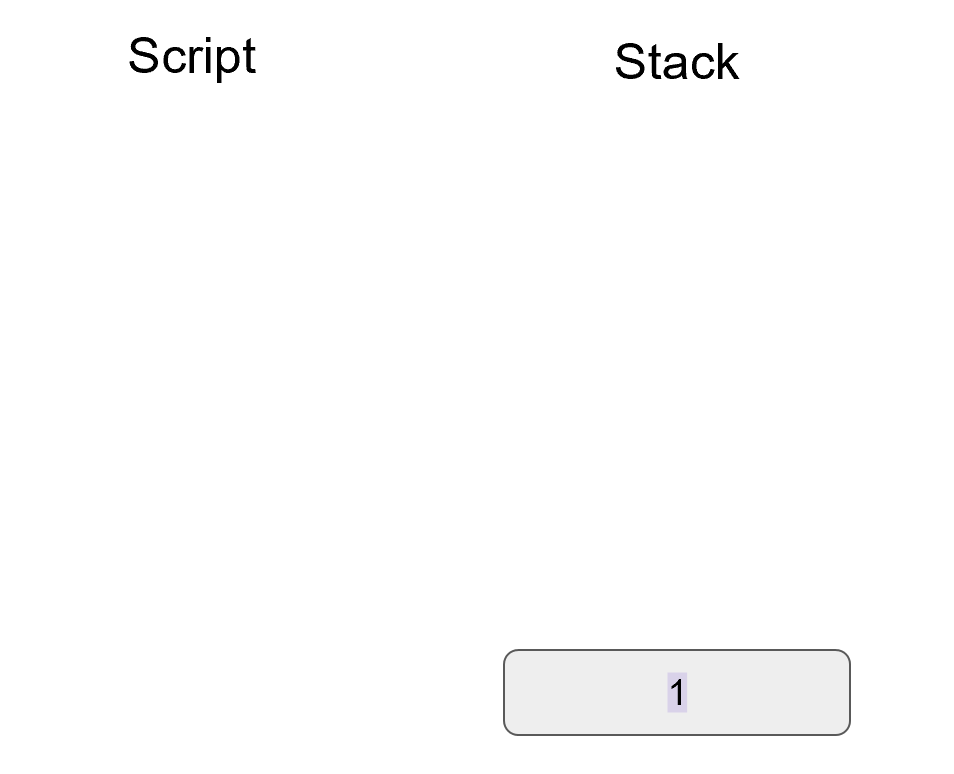

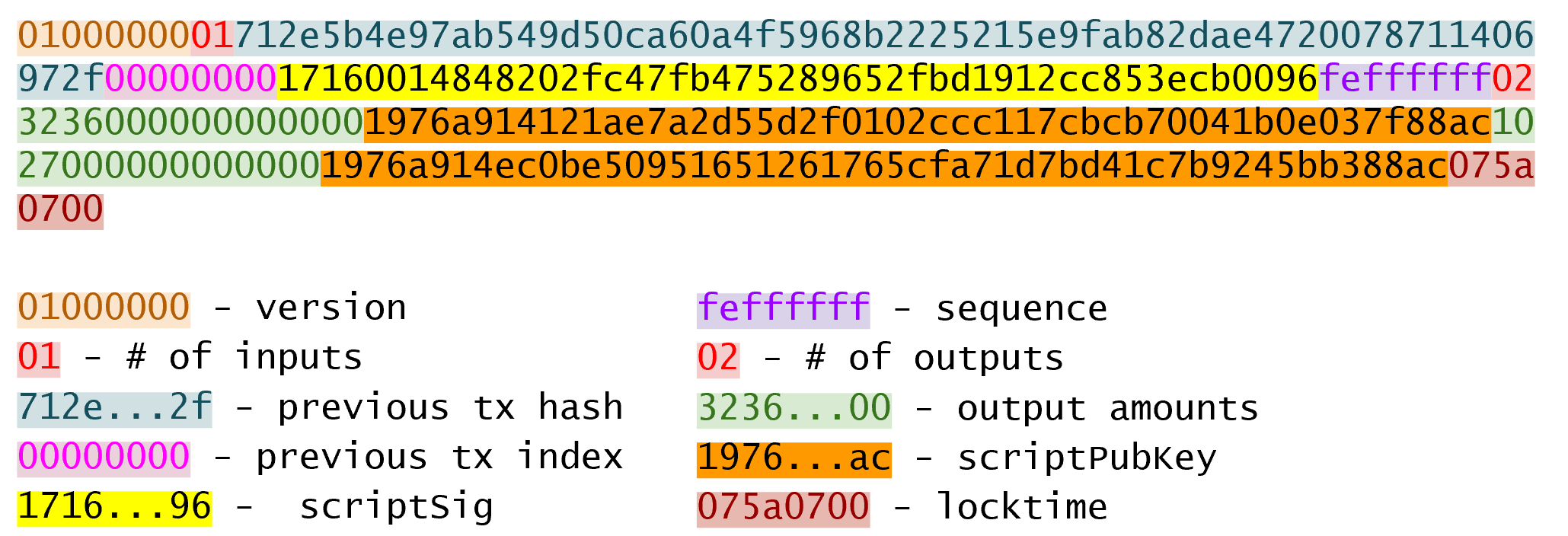

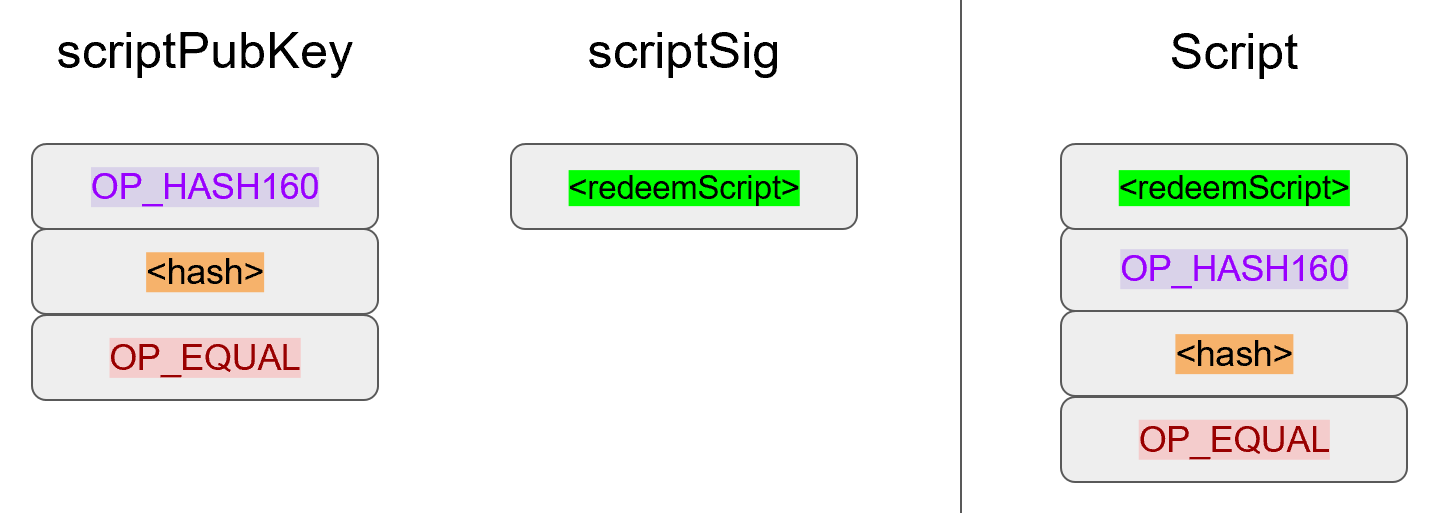

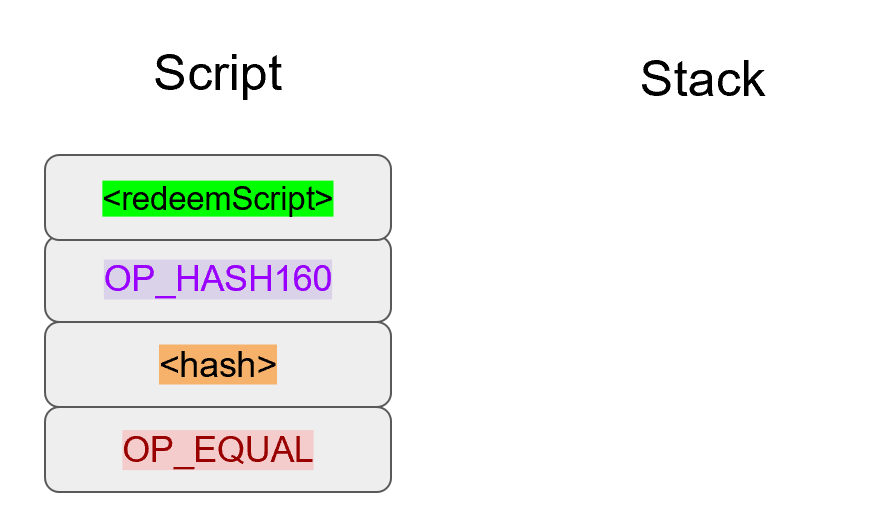

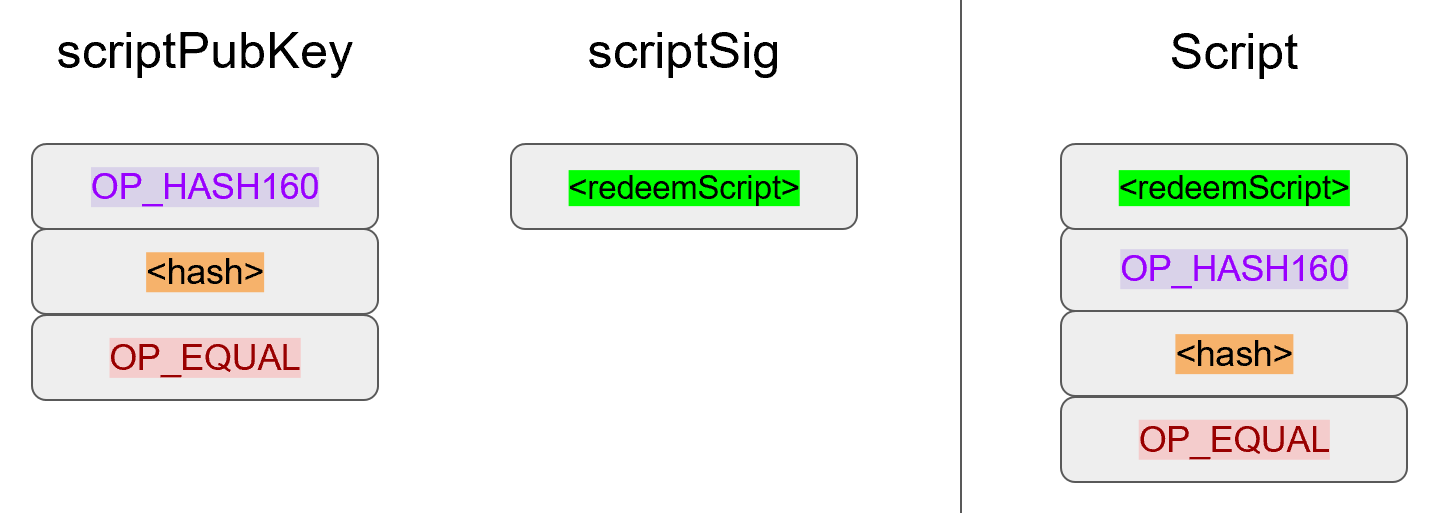

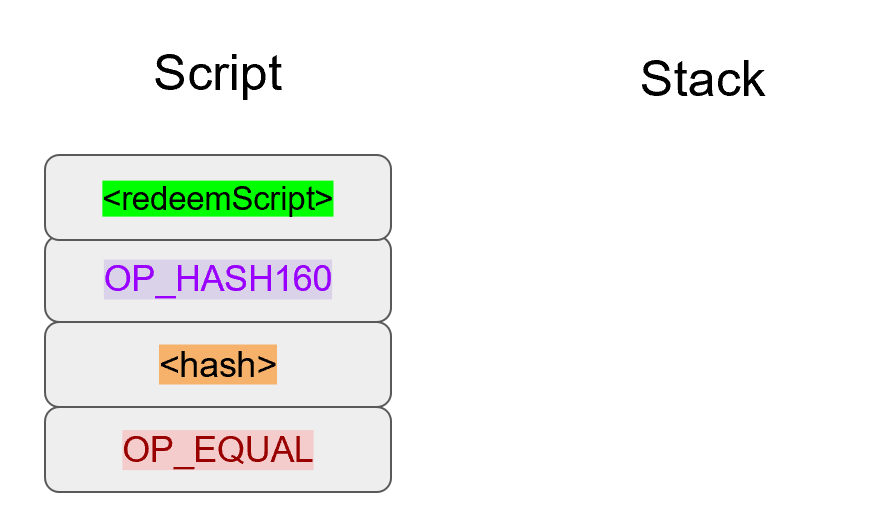

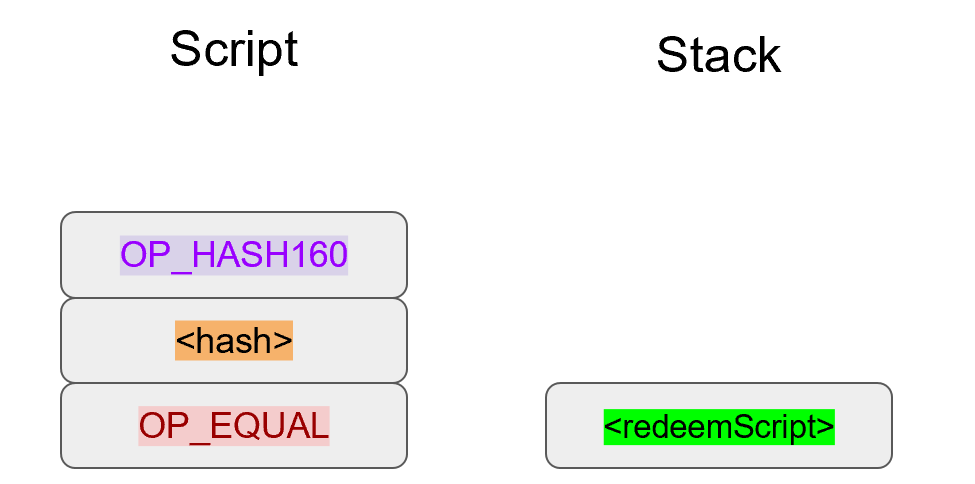

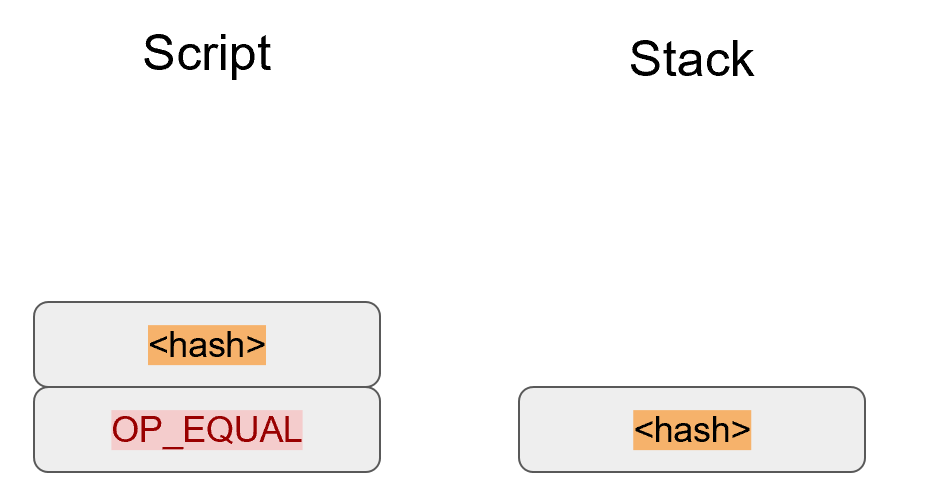

Chapter 5 covers the Transaction structure. Chapter 6 goes into the smart contract language behind Bitcoin called Script. Chapter 7 combines all the previous chapters in validating and creating transactions based on the Elliptic Curve Cryptography from the first 4 chapters. Chapter 8 establishes how p2sh works, which is a way to make more powerful smart contracts.

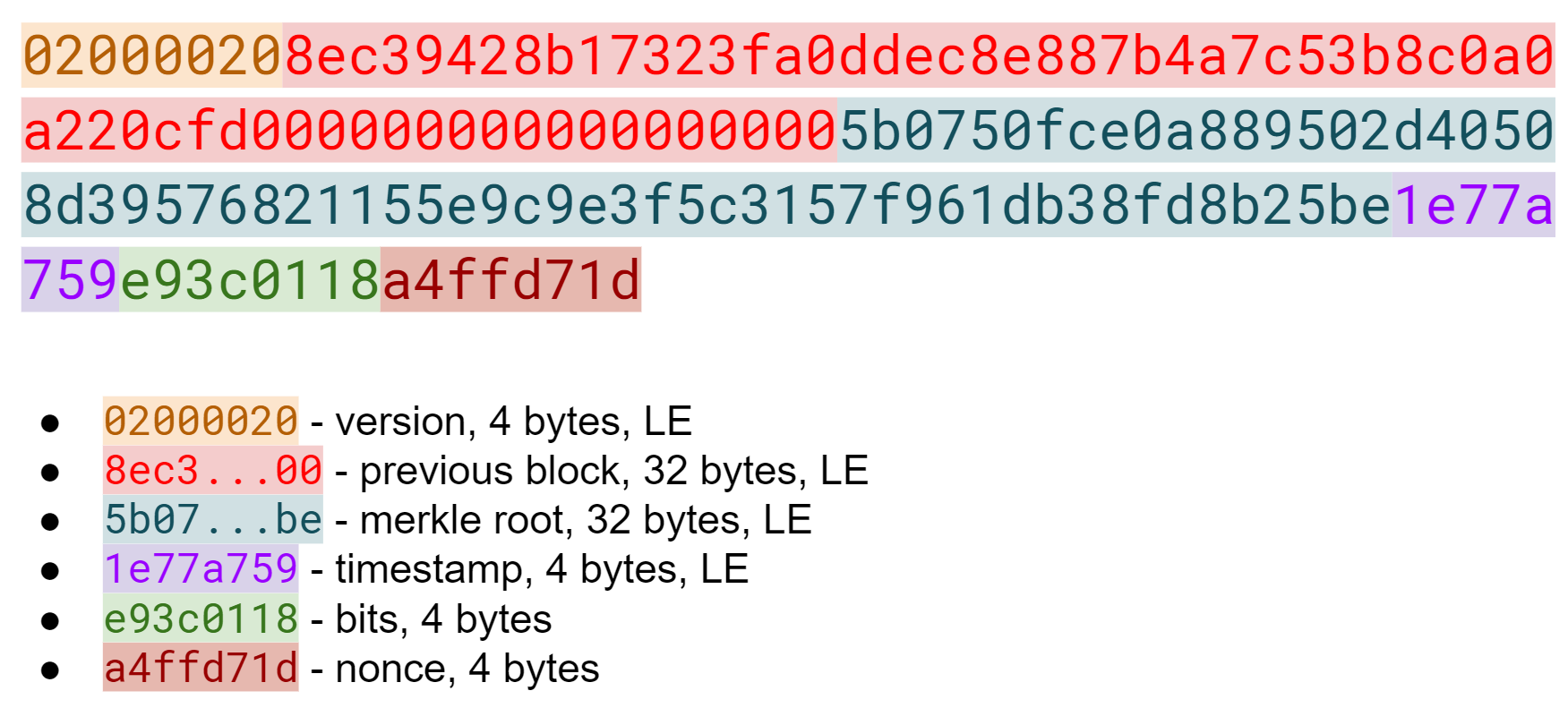

Chapter 9 covers Blocks, which are groups of ordered Transactions. Chapter 10 covers network communication in Bitcoin. Chapter 11 and Chapter 12 go into how a light client, or software without access to the entire blockchain, might request and broadcast data from and to nodes that do have the entire blockchain.

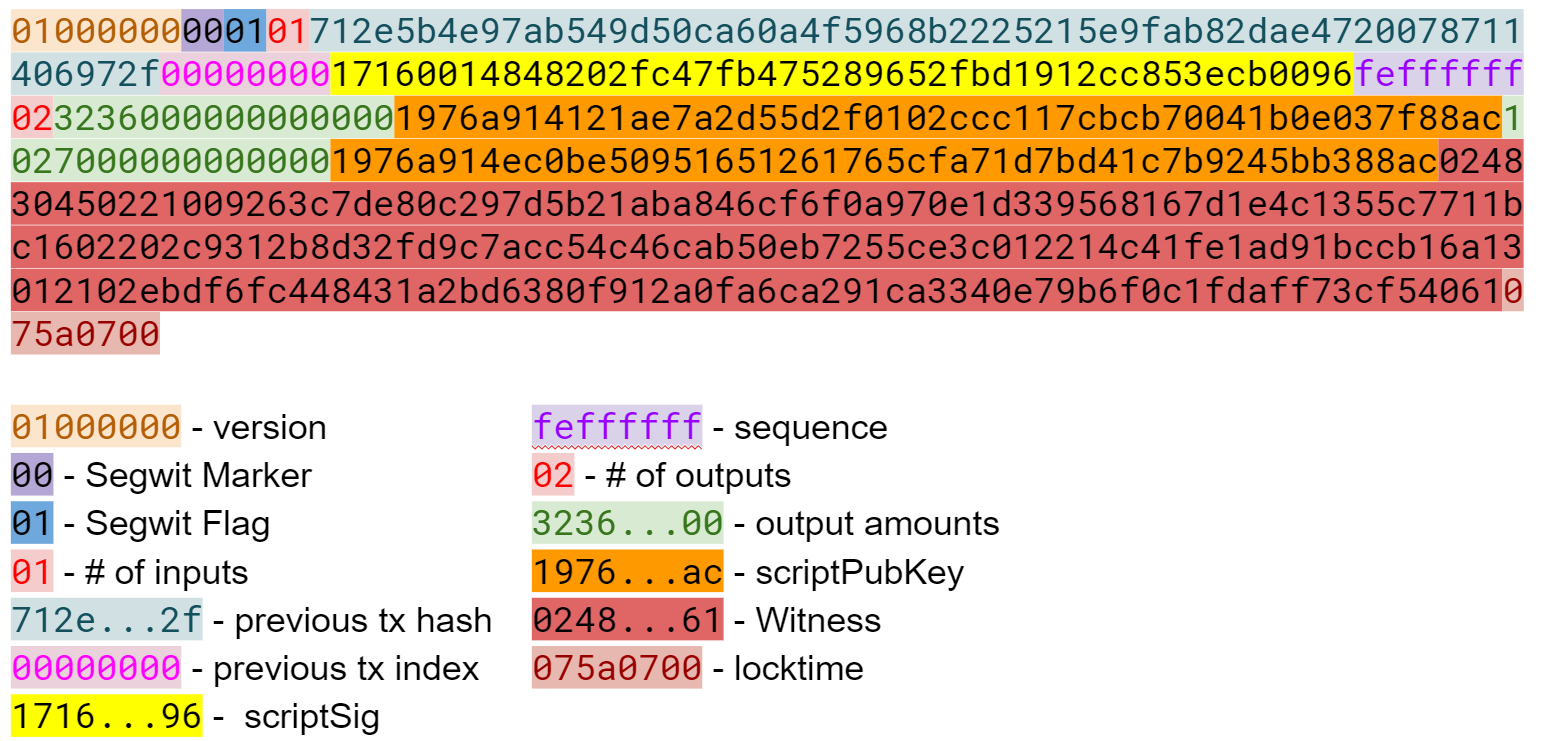

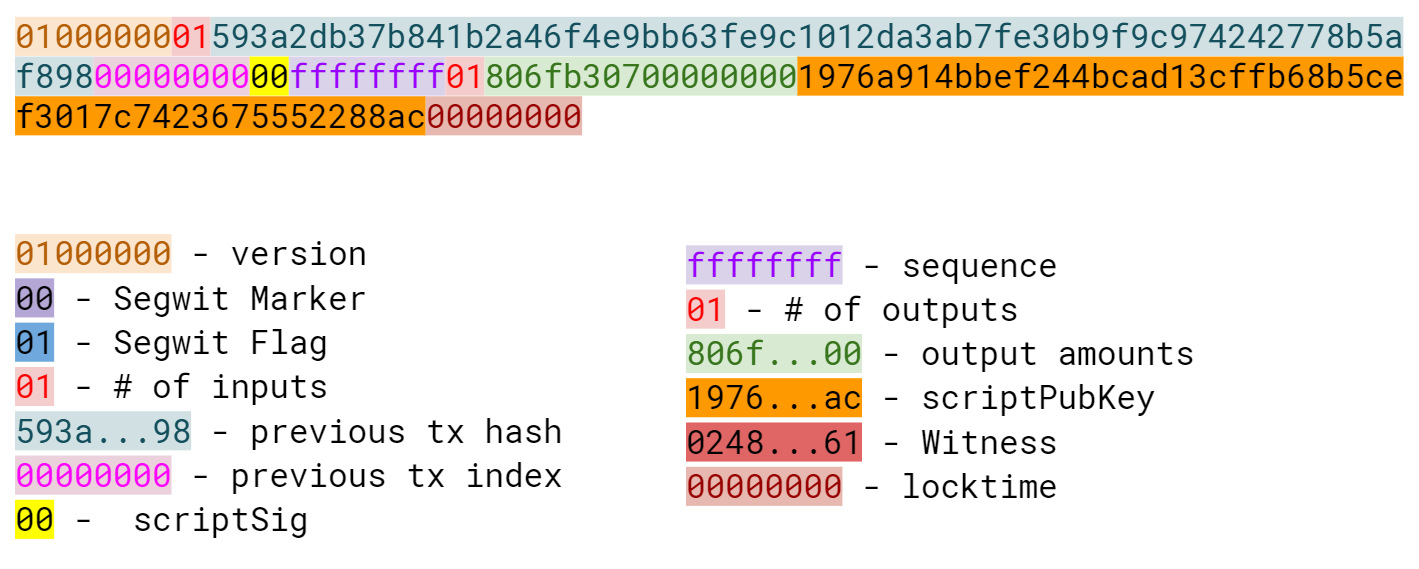

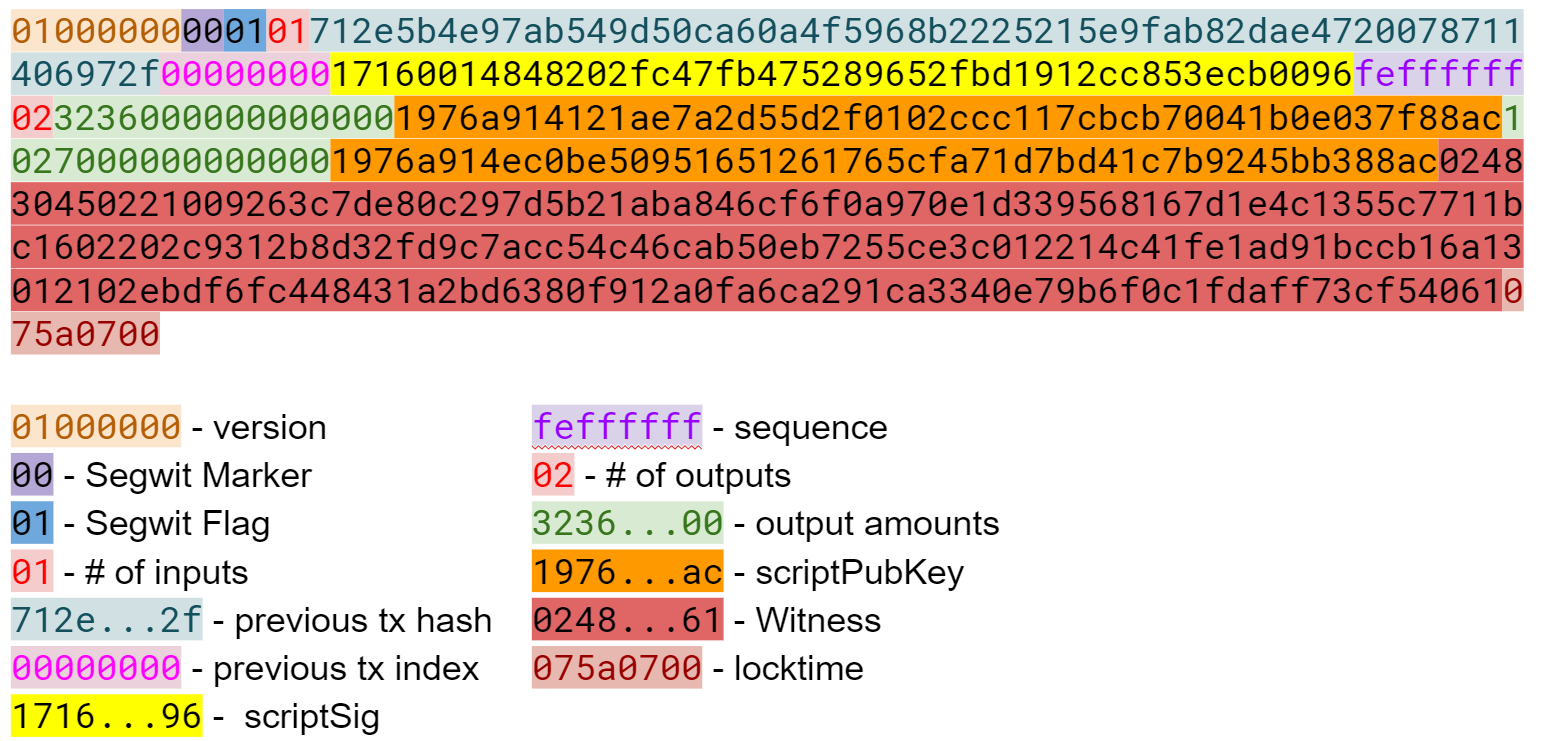

Chapter 13 covers Segwit and Chapter 14 covers suggestions for further study. Again, these chapters are not strictly necessary, but are included as a way to give you a taste of what more there is to learn.

Chapters 1-12 have exercises that require you to build up the library from scratch. The answers are in the Appendix and in the corresponding chapter directory in the GitHub repository (https://github.com/jimmysong/programmingbitcoin). You will be writing many Python classes and will be building towards being able to not just validate transactions/blocks, but also creating your own transactions and broadcasting them on the network.

The last exercise in Chapter 12 is specifically asking you to connect to another node on the testnet network, calculate what you can spend, construct and sign a transaction of your devising and broadcast that on the network. Essentially, the first 11 chapters are setting up toward being able to do this exercise.

There will be a lot of unit tests that you will have to get to pass. The book has been designed this way so you can do the “fun” part of coding. We will be looking at a lot of code and diagrams throughout.

In order to get the most out of this book, you’ll want to create an environment where you can run the example code and do the exercises. Here are the instructions for setting everything up.

Install Python 3.5 or above on your machine:

Windows:

https://www.python.org/ftp/python/3.6.2/python-3.6.2-amd64.exe

Mac OS X:

https://www.python.org/ftp/python/3.6.2/python-3.6.2-macosx10.6.pkg

Linux: see your distro docs (many Linux distributions like Ubuntu come with Python 3.5+ pre-installed)

Install pip:

Download this script:

https://bootstrap.pypa.io/get-pip.py

Run this script using Python 3:

$ python3 get-pip.pyInstall git:

The instructions for downloading and installing are at https://git-scm.com/downloads.

Download the source code for this book:

$git clone https://github.com/jimmysong/programmingbitcoin$cdprogrammingbitcoin

Install virtualenv:

$ pip install virtualenvInstall the requirements:

Linux/OSX:

$virtualenv -p python3 .venv$. .venv/bin/activate(.venv)$pip install -r requirements.txt

Windows:

C:\programmingbitcoin> virtualenv -p C:\PathToYourPythonInstallation\Python.exe .venv C:\programmingbitcoin> .venv\Scripts\activate.bat C:\programmingbitcoin> pip install -r requirements.txt

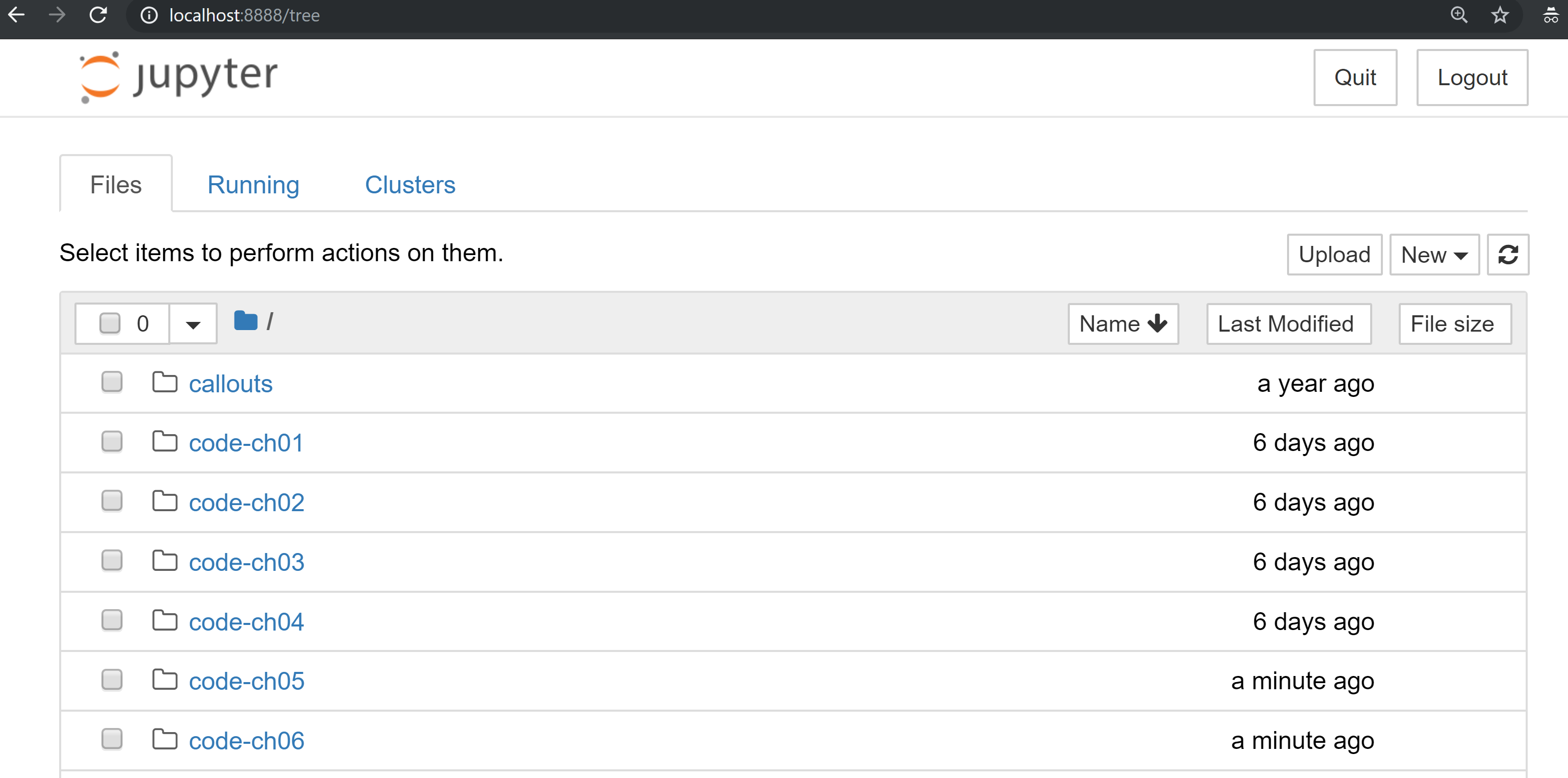

Run Jupyter notebook:

(.venv)$jupyter notebook[I 11:13:23.061 NotebookApp]Serving notebooks fromlocaldirectory: /home/jimmy/programmingbitcoin[I 11:13:23.061 NotebookApp]The Jupyter Notebook is running at:[I 11:13:23.061 NotebookApp]http://localhost:8888/?token=f849627e4d9d07d2158e3fcde93590eff4a9a7a01f65a8e7[I 11:13:23.061 NotebookApp]Use Control-C to stop this server and shut down all kernels(twice to skip confirmation).[C 11:13:23.065 NotebookApp]Copy/paste this URL into your browser when you connectforthe firsttime, to login with a token: http://localhost:8888/?token=f849627e4d9d07d2158e3fcde93590eff4a9a7a01f65a8e7

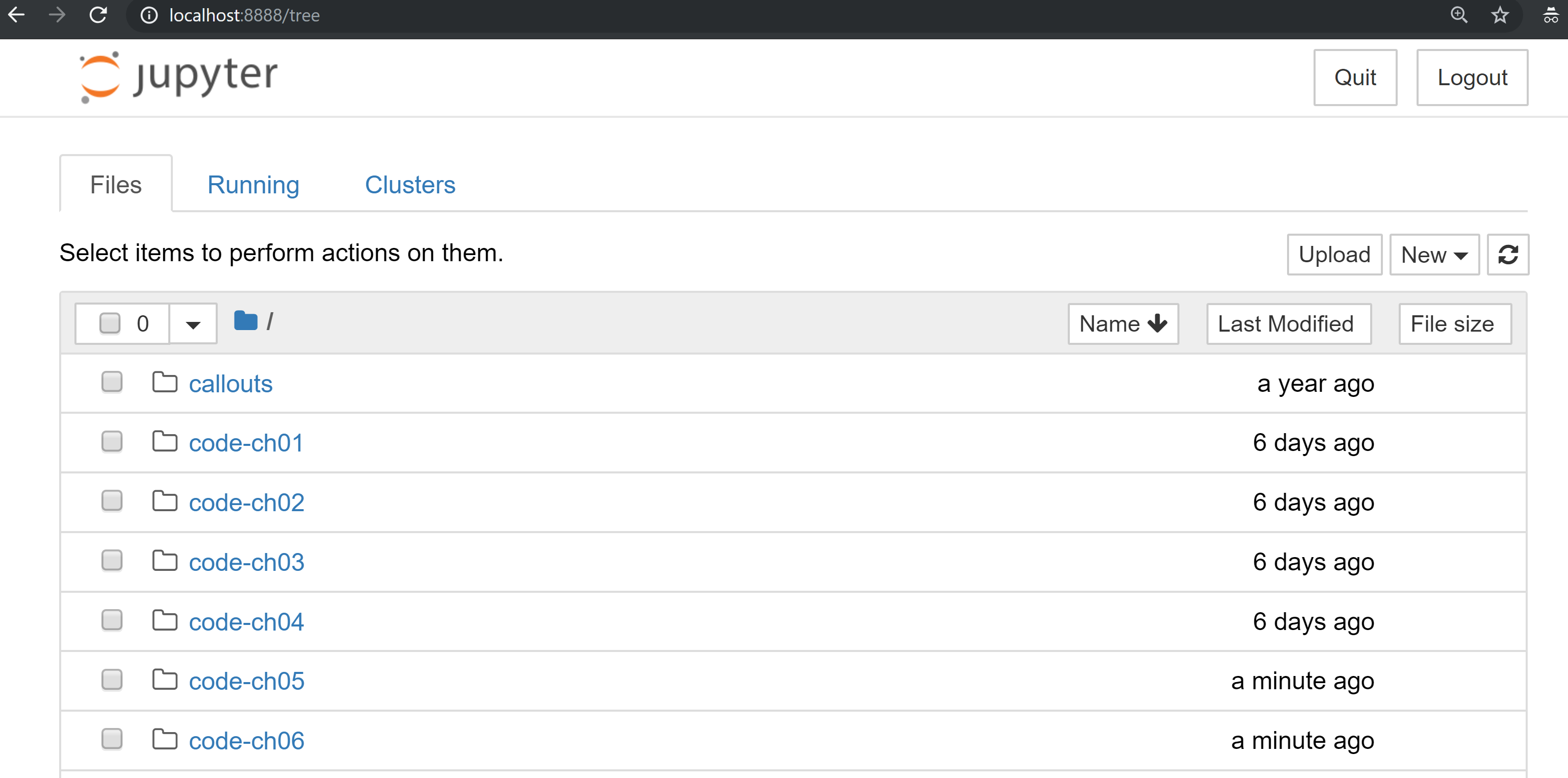

You should have a browser open up automatically:

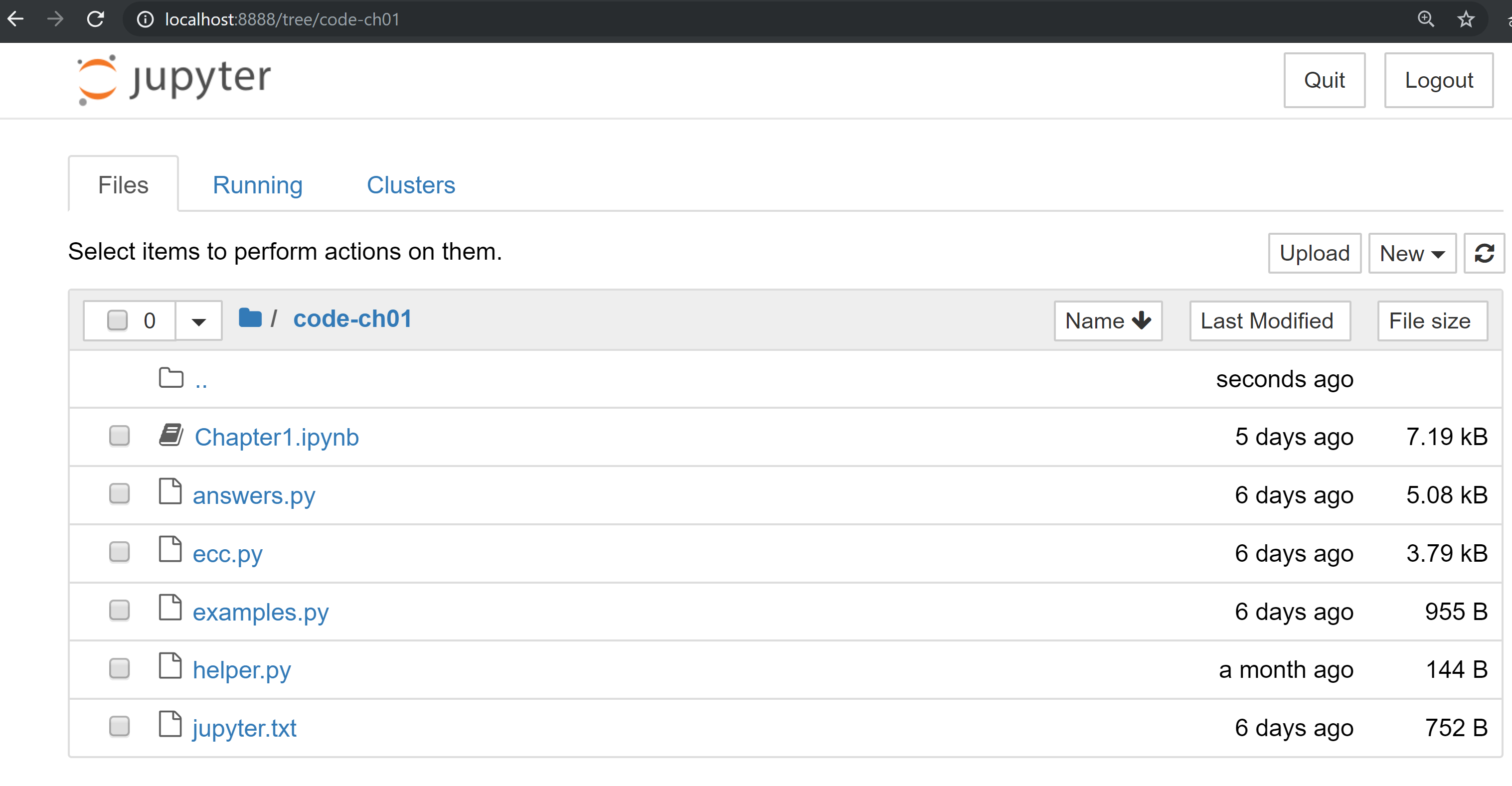

You can navigate to chapter directories. To do the exercises from Chapter 1, you would navigate to code-ch01:

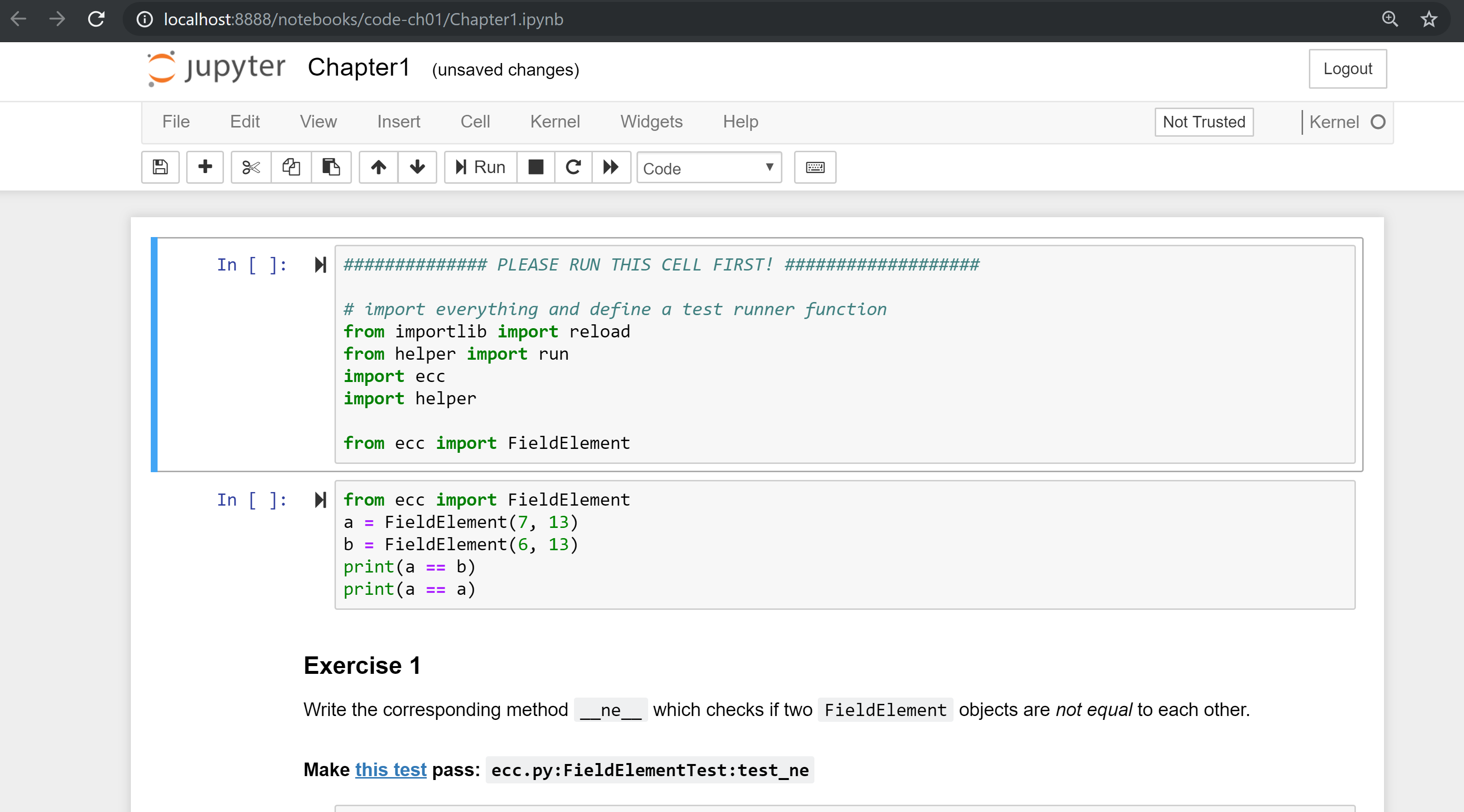

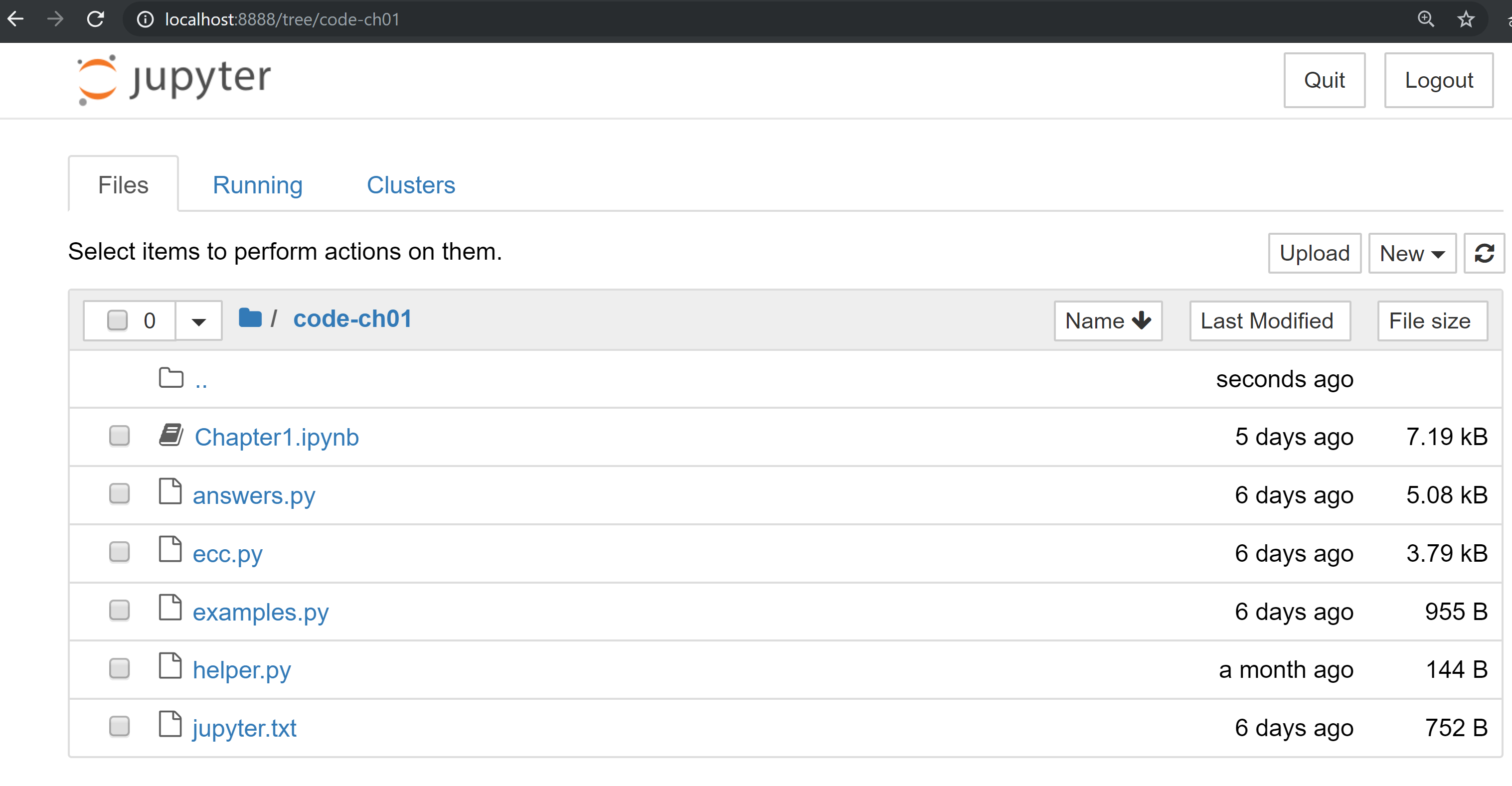

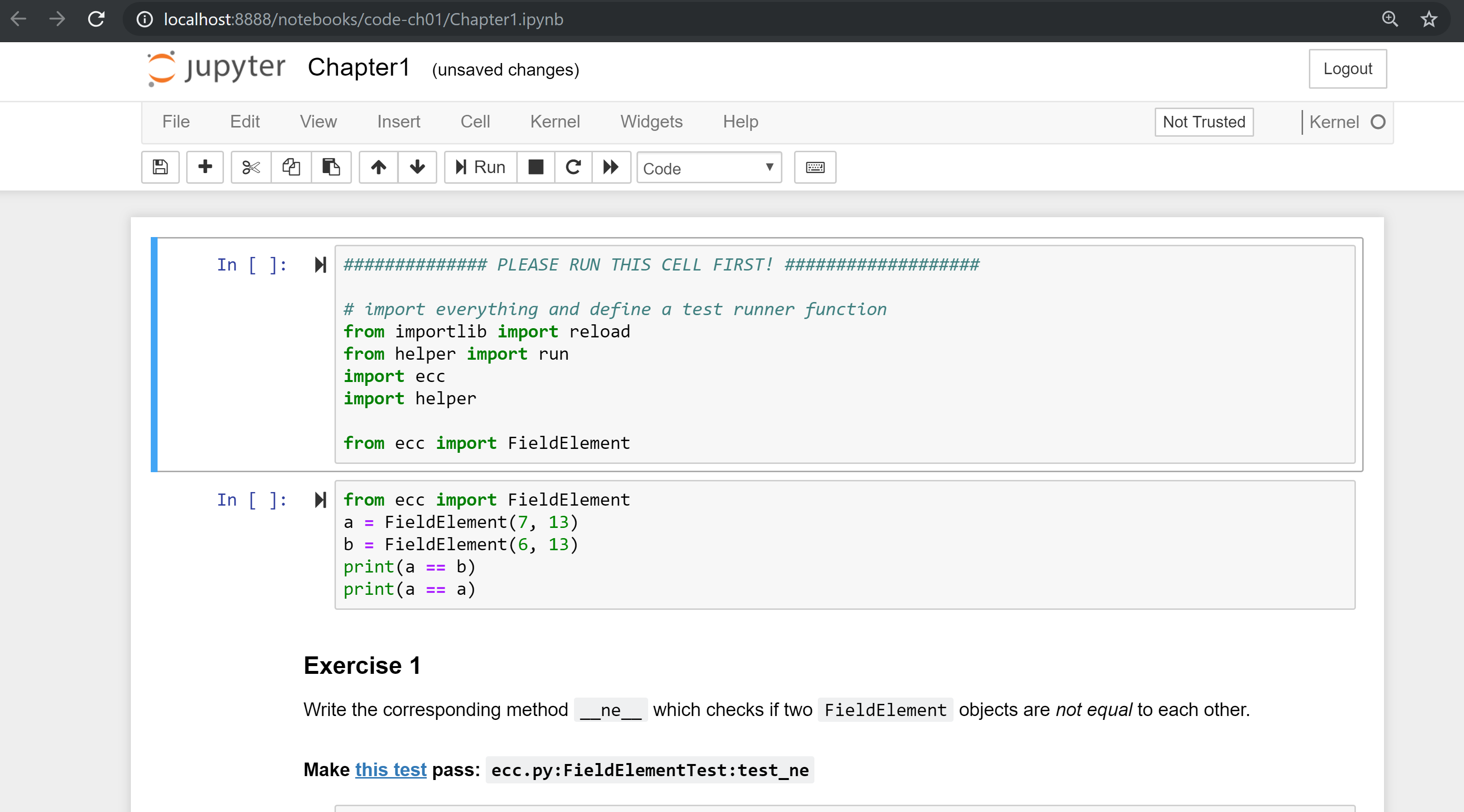

From here you can open Chapter1.ipynb:

You may want to familiarize yourself with this interface if you haven’t seen it before, but the gist of Jupyter is that it can run Python code from the browser in a way to make experimenting easy. You can run each “cell” and see the results as if this were an interactive Python shell.

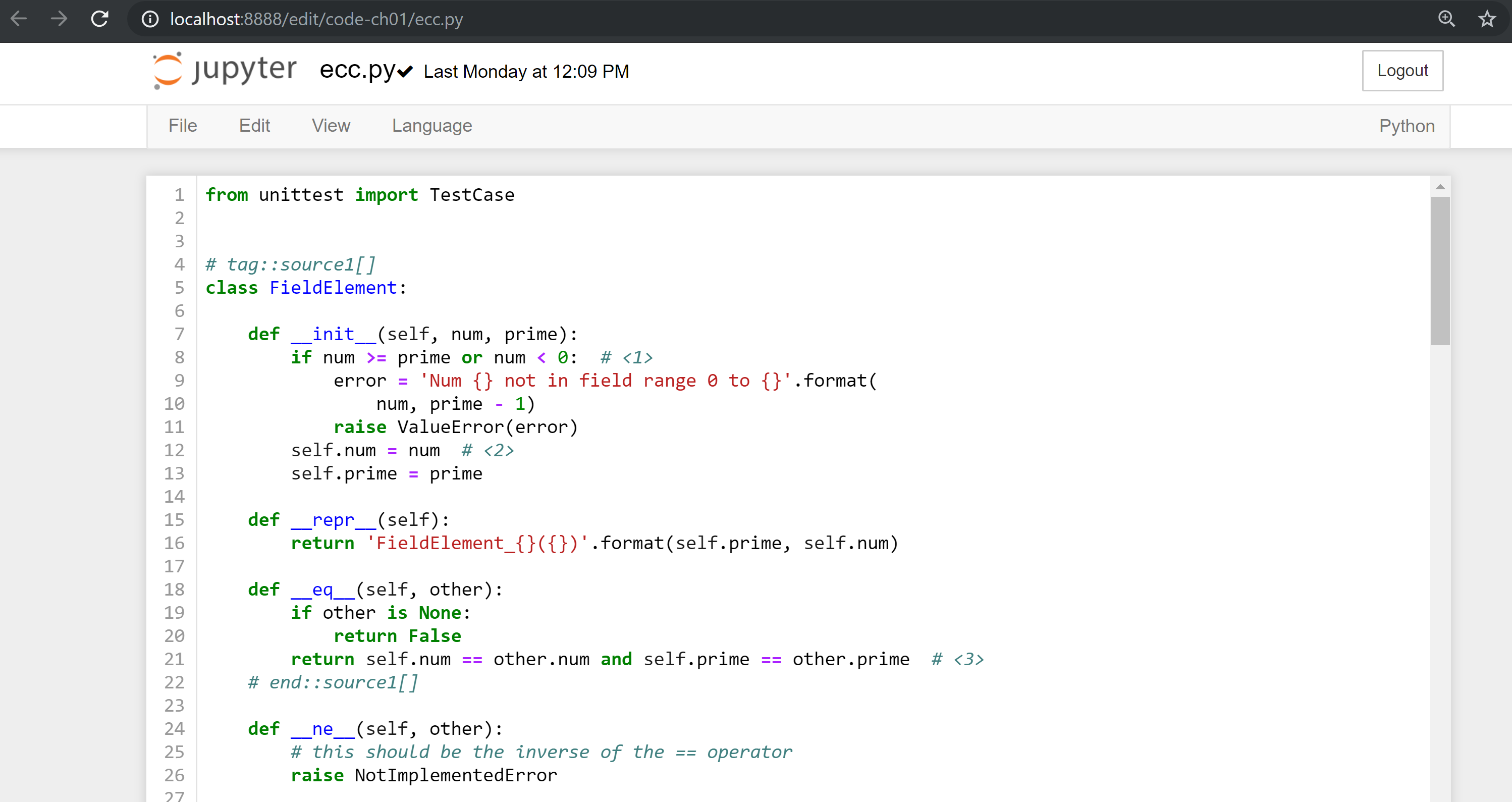

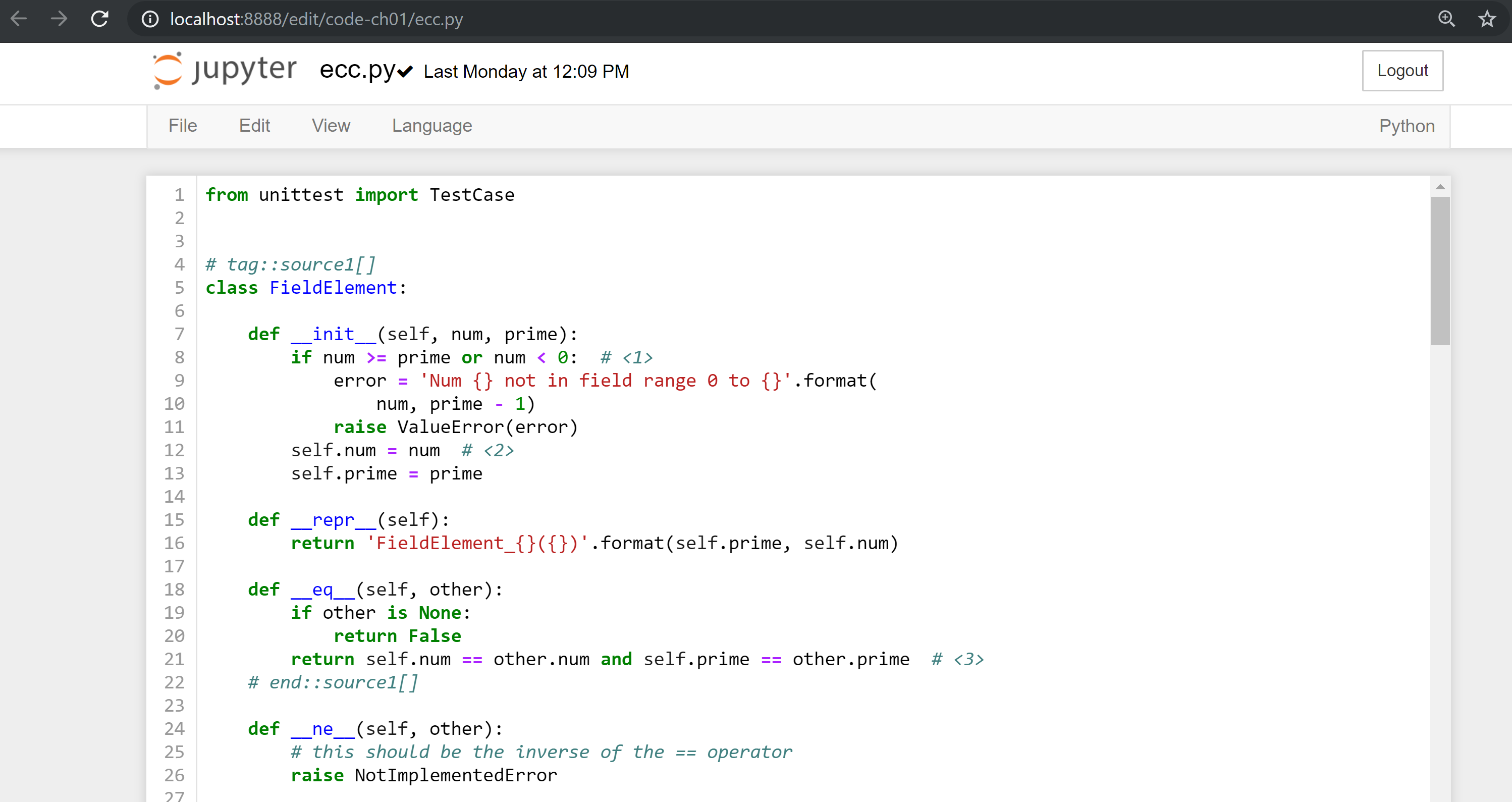

A large portion of the exercises will be coding concepts introduced in the book. The unit tests are written for you and you will need to write the Python code to make the tests pass. You can check whether your code is correct directly in Jupyter. You will need to edit the corresponding file by clicking through a link like the “this test” link in Figure P-3 . This will take you to a browser tab like this:

You can edit the file here and save in order to make the test pass.

All the answers to the various exercises in this book are in the Appendix.

They are also available in the code-chxx/answers.py file where xx is the chapter that you’re on.

The following typographical conventions are used in this book:

Indicates new terms, URLs, email addresses, filenames, and file extensions.

Constant widthUsed for program listings, as well as within paragraphs to refer to program elements such as variable or function names, databases, data types, environment variables, statements, and keywords.

Constant width boldShows commands or other text that should be typed literally by the user.

Constant width italicShows text that should be replaced with user-supplied values or by values determined by context.

This element signifies a tip or suggestion.

This element signifies a general note.

This element indicates a waning or caution.

Supplemental material (code examples, exercises, etc.) is available for download at https://github.com/jimmysong/programmingbitcoin.

This book is here to help you get your job done. In general, if example code is offered with this book, you may use it in your programs and documentation. You do not need to contact us for permission unless you’re reproducing a significant portion of the code. For example, writing a program that uses several chunks of code from this book does not require permission. Selling or distributing a CD-ROM of examples from O’Reilly books does require permission. Answering a question by citing this book and quoting example code does not require permission. Incorporating a significant amount of example code from this book into your product’s documentation does require permission.

We appreciate, but do not require, attribution. An attribution usually includes the title, author, publisher, and ISBN. For example: “Programming Bitcoin by Jimmy Song (O’Reilly). Copyright 2019, 978-0-596-xxxx-x.”

If you feel your use of code examples falls outside fair use or the permission given above, feel free to contact us at permissions@oreilly.com.

Safari (formerly Safari Books Online) is a membership-based training and reference platform for enterprise, government, educators, and individuals.

Members have access to thousands of books, training videos, Leaning Paths, interactive tutorials, and curated playlists from over 250 publishers, including O’Reilly Media, Harvard Business Review, Prentice Hall Professional, Addison-Wesley Professional, Microsoft Press, Sams, Que, Peachpit Press, Adobe, Focal Press, Cisco Press, John Wiley & Sons, Syngress, Morgan Kaufmann, IBM Redbooks, Packt, Adobe Press, FT Press, Apress, Manning, New Riders, McGraw-Hill, Jones & Bartlett, and Course Technology, among others.

For more information, please visit http://oreilly.com/safari.

Please address comments and questions concerning this book to the publisher:

We have a web page for this book, where we list errata, examples, and any additional information. You can access this page at http://www.oreilly.com/catalog/<catalog page>.

To comment or ask technical questions about this book, send email to bookquestions@oreilly.com.

For more information about our books, courses, conferences, and news, see our website at http://www.oreilly.com.

Find us on Facebook: http://facebook.com/oreilly

Follow us on Twitter: http://twitter.com/oreillymedia

Watch us on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/oreillymedia

One of the most difficult things about learning how to program Bitcoin is knowing where to start. There are so many components that depend on each other that learning one thing may lead you to have to learn another which in turn may lead you to learn something else before you can understand the original thing.

This chapter is going to get you off to a start which is more manageable. It may seem strange, but we’ll start with the basic math that you need to understand Elliptic Curve Cryptography. Elliptic Curve Cryptography, in turn, gives us the signing and verification algorithms. These are at the heart of how Transactions work, and Transactions are the atomic unit of value transfer in Bitcoin. By learning Finite Fields and Elliptic Curves first, you’ll get a firm grasp of concepts that you’ll need in order to progress logically.

Be aware that this chapter and the next two chapters may feel a bit like you’re eating vegetables, especially if you haven’t done formal math in a long time. I would encourage you to get through this as the concepts and code here will be used throughout the book.

Learning about new mathematical structures can be a bit intimidating and in this chapter, I hope to dispel the myth that high level math is difficult. Finite Fields, in particular, don’t require all that much in terms of prior mathematical knowledge than, say, Algebra.

Think of Finite Fields as something that you could have learned instead of Trigonometry, just that the education system you’re a part of decided that Trigonometry was more important for you to learn. This is my way of telling you that Finite Fields are not that hard to learn and require no more background than Algebra.

This chapter is required if you want to understand Elliptic Curve Cryptography. Elliptic Curve Cryptography is required for understanding signing and verification, which is at the heart of Bitcoin itself. As I’ve said, this chapter and the next two may feel a bit unrelated, but I encourage you to endure. The fundamentals here will not only make understanding Bitcoin a lot easier, but also make understanding Schnorr Signatures, Confidential Transactions and other leading edge Bitcoin technologies easier.

Mathematically, a Finite Field is defined as follows:

A finite set of numbers and two operations + (addition) and ⋅ (multiplication) that satisfy the following:

If a and b are in the set, a+b and a⋅b are in the set. We call this property closed.

The additive identity, 0 exists and has the property a + 0 = a.

The multiplicative identity, 1 exists and has the property a ⋅ 1 = a.

If a is in the set, -a is in the set, which is defined as the value that makes a + (-a) = 0. This is what we call the additive inverse.

If a is in the set and is not 0, a-1 is in the set, which is defined as the value that makes a ⋅ a-1 = 1. This is what we call the multiplicative inverse.

Let’s unpack each of the following.

We have a set of numbers that’s finite. Because the set is finite, we can designate a number p which is how big the set is. This is what we call the order of the set.

(1) says we are closed under addition and multiplication. This means that we have to define addition and multiplication in a way as to make sure that the results stay in the set. For example, a set containing {0,1,2} is not closed under addition since 1+2=3 and 3 is not in the set, neither is 2+2=4. Of course we can define addition a little differently to make this work, but using “normal” addition, this set is not closed. On the other hand, the set {-1,0,1} is closed under normal multiplication. Any two numbers can be multiplied (there are 9 such combinations) and the result is always in the set.

The other option we have in mathematics is to define multiplication in a particular way to make these sets closed. We’ll get to how exactly we define addition and multiplication later in this chapter, but the key concept here is that we can define addition and subtraction differently than the addition and subtraction you are familiar with.

(2) and (3) mean that we have the additive and multiplicative identities. That means 0 and 1 are in the set.

(4) means that we have the additive inverse. That is, if a is in the set, -a is in the set. Using the additive inverse, we can define subtraction.

(5) means that multiplication has the same property. If a is in the set, a-1 is in the set. That is a⋅a-1=1. Using the multiplicative inverse, we can define division. This will be the trickiest to define in a finite field.

If the order (or size) of the set is p, we can call the elements of the set, 0, 1, 2, …p-1. These numbers are what we call the elements of the set, not necessarily the traditional numbers 0, 1, 2, 3, etc. They behave in many ways like traditional numbers, but have some differences in how we add, subtract, multiply, etc.

In math notation the Finite Field set looks like this:

Fp = {0, 1, 2, … p-1}

What’s in the Finite Field set are called elements. Fp is a specific finite field called “field of p” or “field of 29” or whatever the size of it is (again, the size is what mathematicians call order). The numbers between the {}`s represent what elements are in the field. We name the elements 0, 1, 2, etc because they’re convenient for our purposes.

A Finite Field of order 11 looks like this:

F11 = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10}

A Finite Field of order 17 looks like this:

F17= {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16}

A Finite Field of order 981 looks like this:

F981= {0, 1, 2, … 980}

Notice the order of the field is always 1 more than the largest element. You might have noticed that the field has a prime order every time. For a variety of reasons which will become clear later, it turns out that fields must an order that is a power of a prime, but that the Finite Fields whose order is of prime order are the ones we’re interested in.

We want to represent each Finite Field element and in Python, we’ll be creating a class that represents a single Finite Field element.

Naturally, we’ll name the class FieldElement.

The class represents an element in a field Fprime. The bare bones of the class look like this:

classFieldElement:def__init__(self,num,prime):ifnum>=primeornum<0:error='Num {} not in field range 0 to {}'.format(num,prime-1)raiseValueError(error)self.num=numself.prime=primedef__repr__(self):return'FieldElement_{}({})'.format(self.prime,self.num)def__eq__(self,other):ifotherisNone:returnFalsereturnself.num==other.numandself.prime==other.prime

We first check that num is between 0 and prime-1 inclusive.

If not, we have an invalid Field Element and we raise a ValueError which is what we should raise when we get an inappropriate value.

The rest of the __init__ method assigns the initialization values to the object.

The __eq__ method checks if two objects of class FieldElement are equal.

This is only true when the num and prime properties are equal.

What we’ve defined already allows us to do this:

>>>fromeccimportFieldElement>>>a=FieldElement(7,13)>>>b=FieldElement(6,13)>>>(a==b)False>>>(a==a)True

Python allows us to override the == operator on FieldElement with the __eq__ method, which is something we’ll be taking advantage of going forward.

You can see this in action in the code that accompanies this book.

Once you’ve set up Jupyter Notebook (see Preface), you can navigate to code-ch01/Chapter1.ipynb and run the code to see the results.

For the next exercise, you’ll want to open up ecc.py by clicking the link in the Exercise 1 box.

If you get stuck, please remember that the answers to every exercise are in the Appendix.

Write the corresponding method __ne__ which checks if two FieldElement objects are not equal to each other.

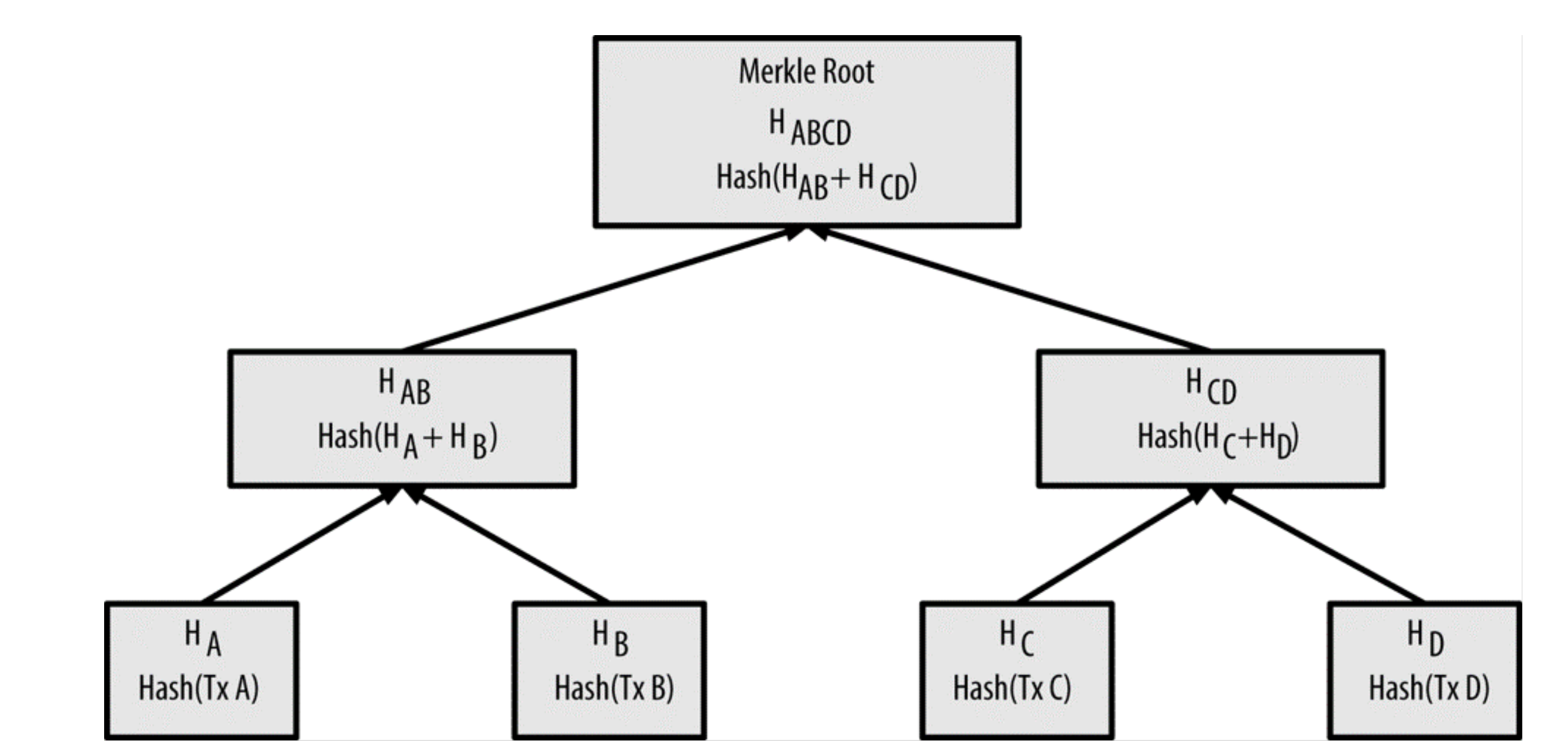

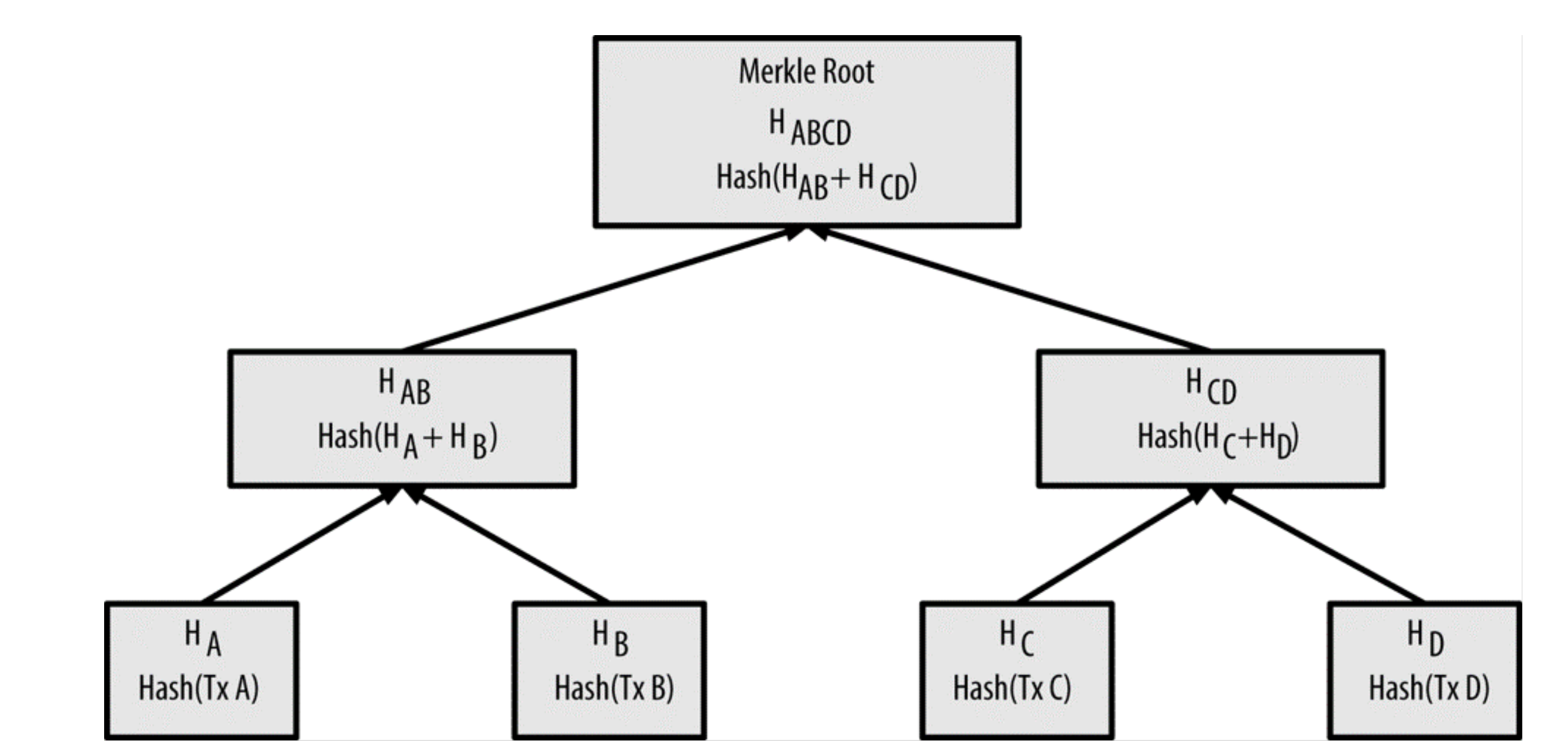

One of the tools we can use in order to make a Finite Field closed under addition, subtraction, multiplication and division is something called modulo arithmetic.

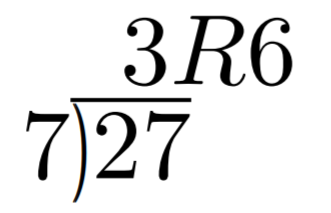

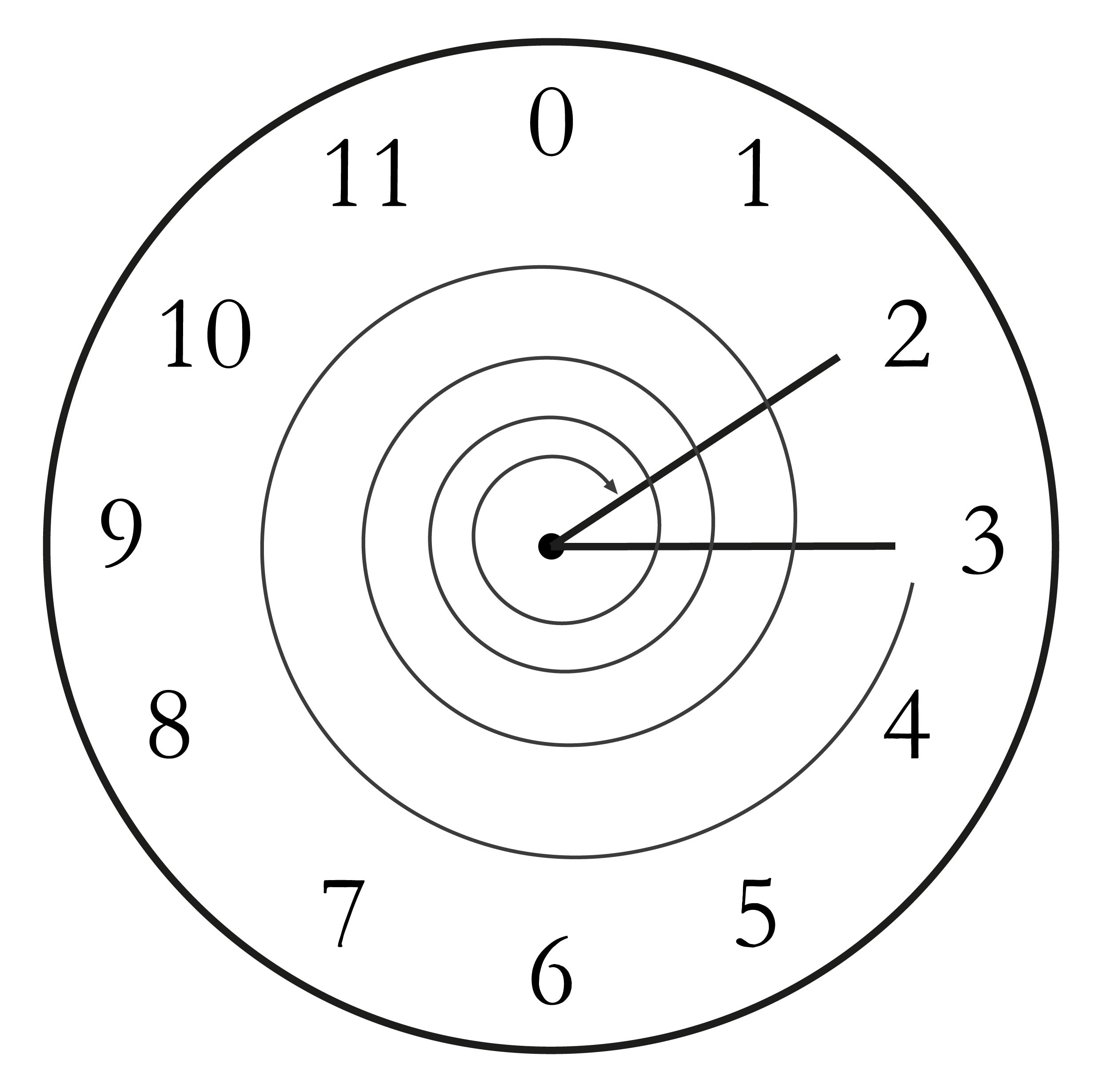

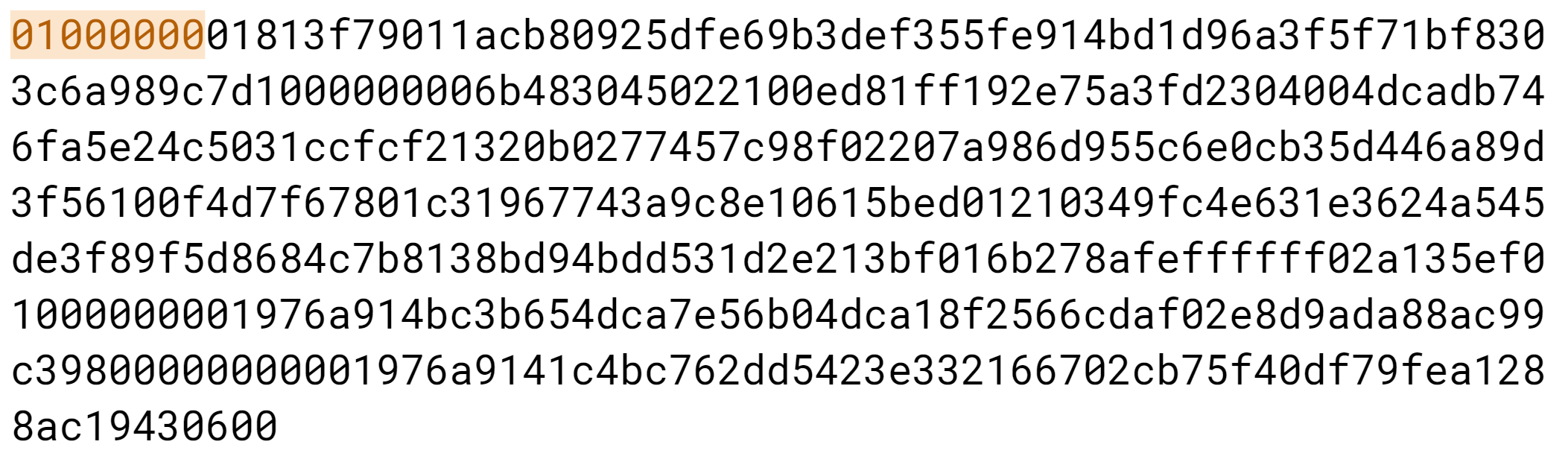

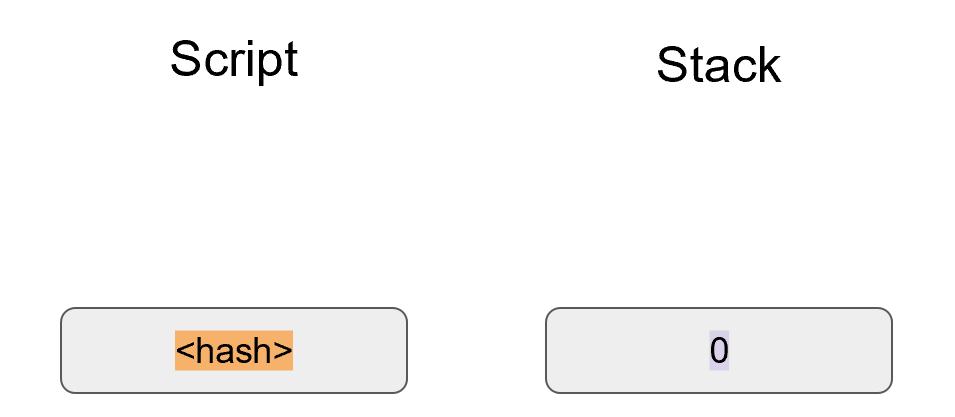

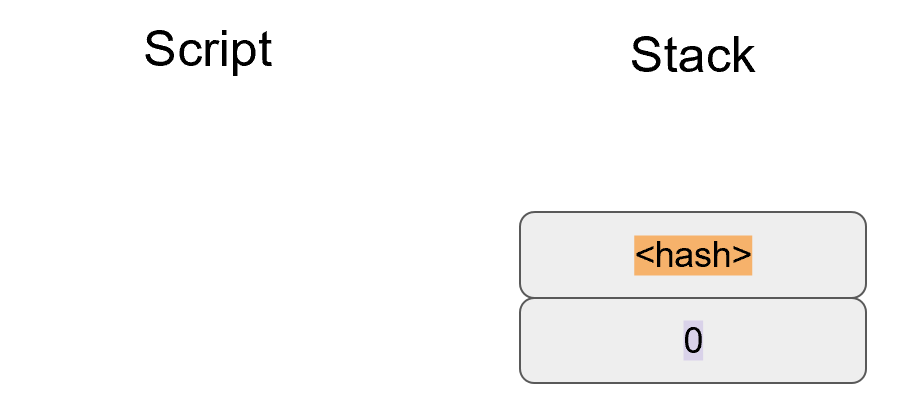

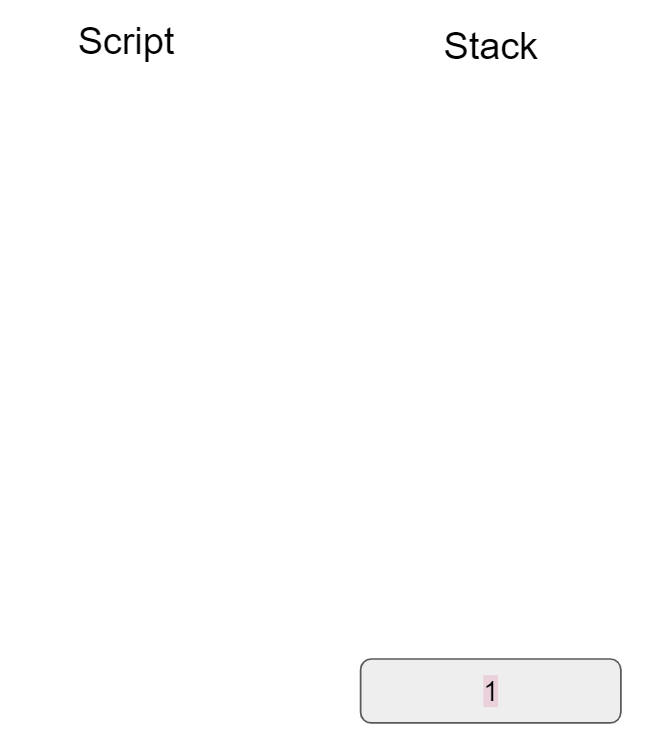

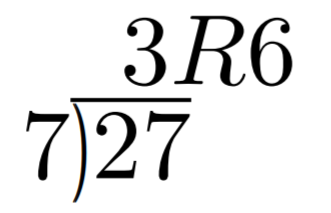

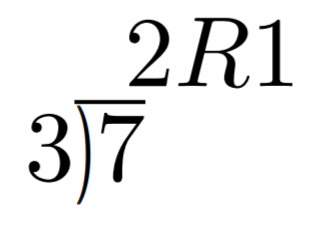

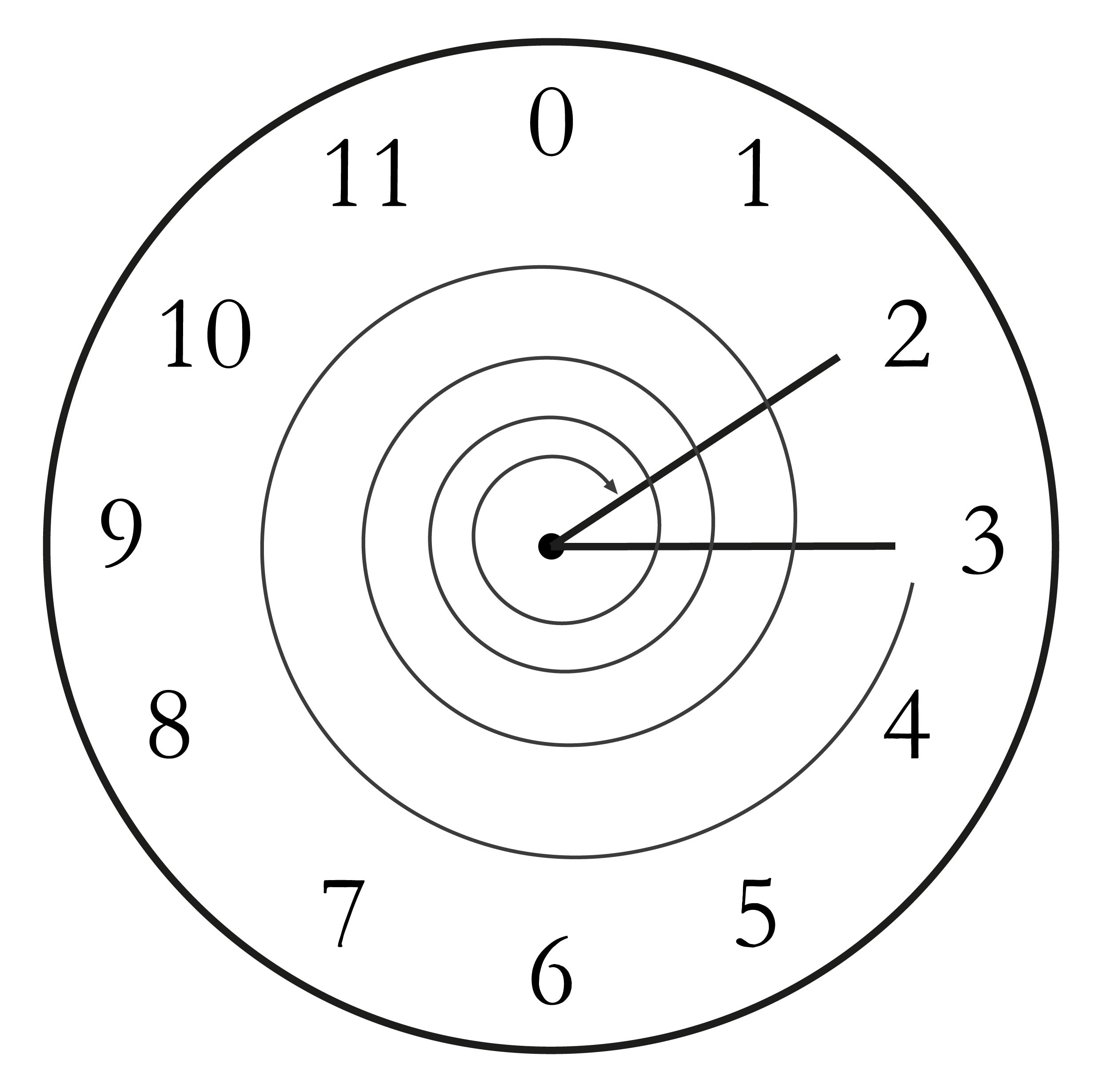

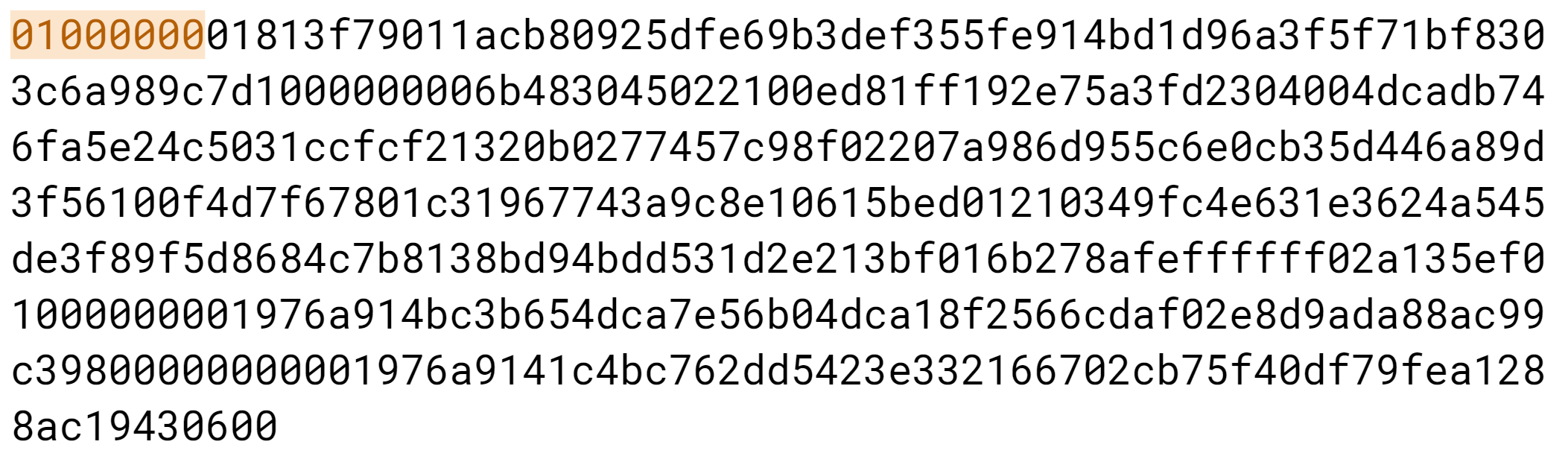

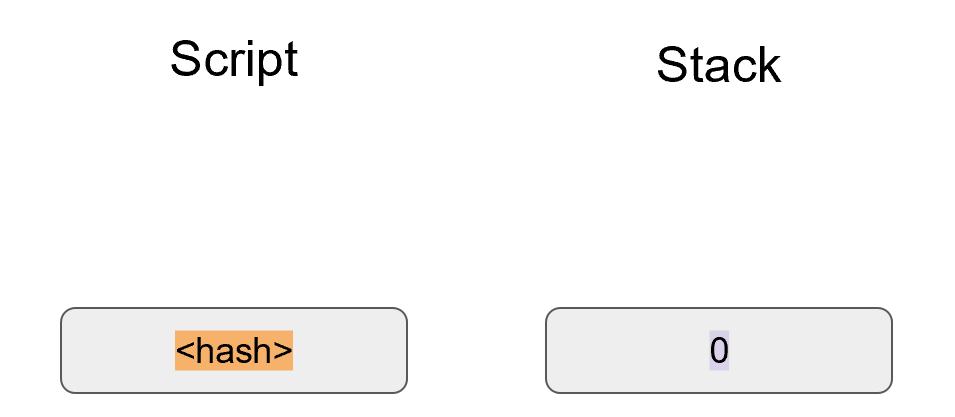

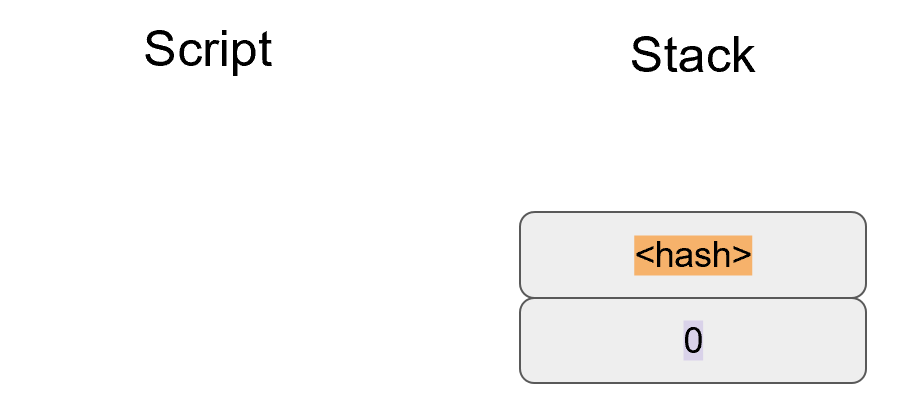

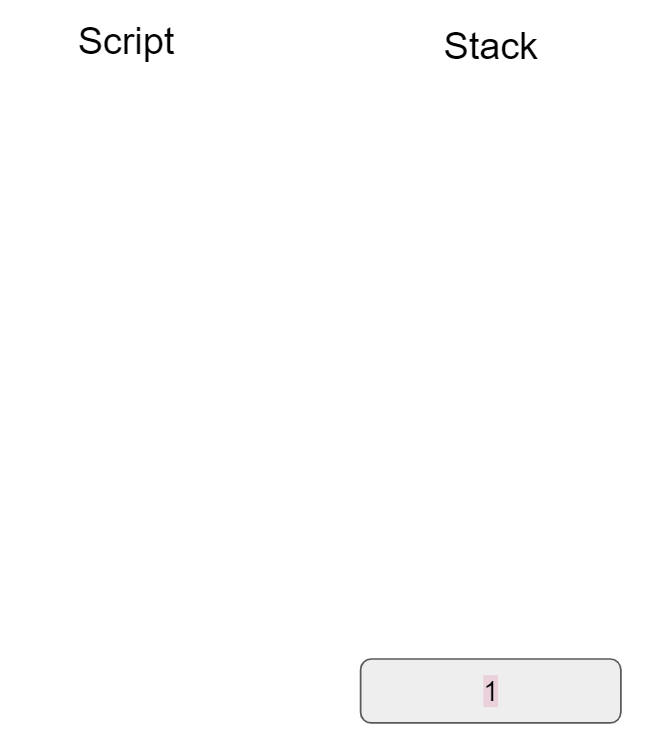

We can define addition on the finite set using something called modulo arithmetic. Modulo arithmetic is something you probably learned when you first learned division. Remember problems like Figure 1-1?

Whenever the division wasn’t even, there was something called the “remainder” which is the leftover from the actual division. We define modulo in the same way. We use the operator % for “modulo”.

7 % 3 = 1

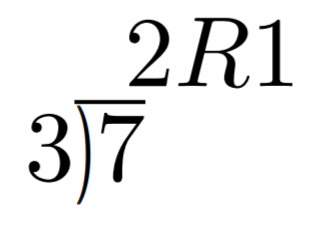

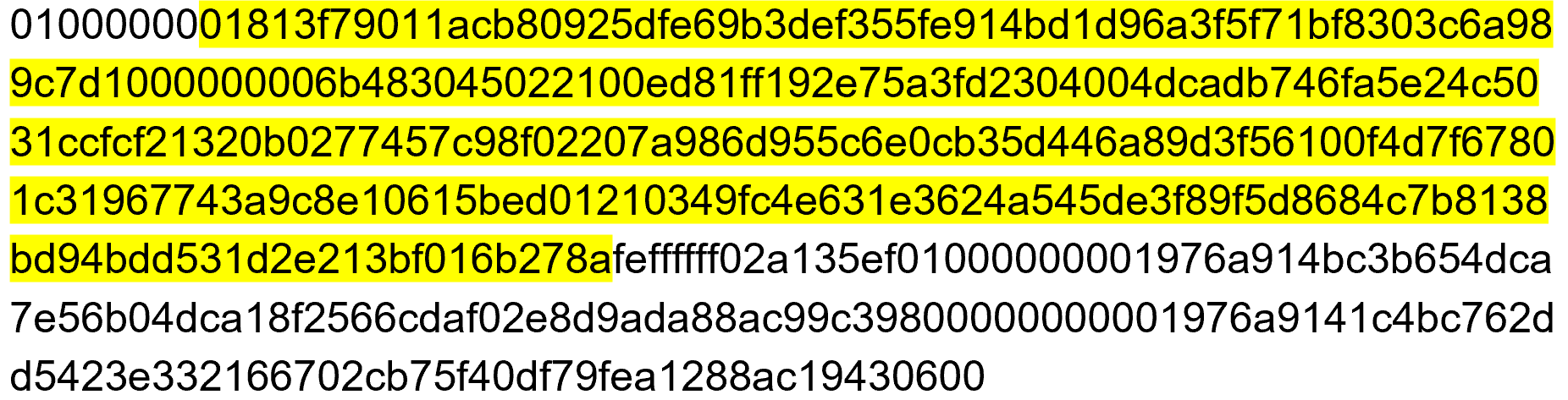

Figure 1-2 shows another example.

Formally speaking, the modulo operation is the remainder after division of one number by another. Let’s look at another example with larger numbers:

1747 % 241 = 60

If it helps, you can think of modulo arithmetic as “wrap-around” or “clock” math. Imagine a problem like this:

It is currently 3 o’clock. What hour will it be 47 hours from now?

The answer is 2 o’clock because (3 + 47) % 12 = 2 (see Figure 1-3)

We can also see this as “wrapping around” in the sense that you go past zero every time we move ahead 12 hours.

We can perform modulo on negative numbers. For example, you can ask:

It is currently 3 o’clock. What hour was it 16 hours ago?

The answer is 11 o’clock. Hence we can say:

(3 - 16) % 12 = 11

The minute hand is also a modulo operation. For example, you can ask:

It is currently 12 minutes past the hour. What minute will it be 843 minutes from now?

(12 + 843) % 60 = 15

It will be 15 minutes past the hour. Likewise, we can ask:

It is currently 23 minutes past the hour. What minute will it be 97 minutes from now?

(23 + 97) % 60 = 0

0 is another way of saying there is no remainder.

The result of the modulo (%) operation for minutes is always between 0 and 59, inclusive, in this case. This happens to be a very useful property as even very large numbers can be brought down to a relatively small range with modulo:

14738495684013 % 60 = 33

We’ll be using modulo as we define field arithmetic. Most operations in Finite Fields use the modulo operator in some capacity.

Python uses the % operator for modulo arithmetic.

Here is how the modulo operator is used:

>>>(7%3)1

We can also use the modulo operator on negative numbers like this:

>>>(-27%13)12

Remember that we need to define Finite Field addition in a way as to make sure that the result is still in the set. That is, we want to make sure that addition in a Finite Field is closed.

We can use what we just learned, modulo arithmetic, to make addition closed. Let’s say we have a Finite Field of 19:

F19={0,1,2,…18}, where a, b ∈ F19

Note that the symbol ∈ means “is an element of”.

In our case, a and b are elements of F19.

Addition being closed means:

a+fb ∈ F19

We denote Finite Field addition with +f to avoid confusion with normal integer addition +.

If we utilize modulo arithmetic, we can guarantee this to be the case. We can define a+fb this way:

a+fb = (a+b)%19

For example:

7+f8 = (7+8)%19 = 15

11+f17 = (11+17)%19 = 9

and so on.

We take any two numbers in the set, add and “wrap around” the end to get the sum. We are creating our own addition operator here and the result is a bit unintuitive. After all 11+f17=9 just doesn’t look right for because we’re not used to Finite Field addition.

More generally, we define field addition this way:

a+fb=(a+b)%p where a, b ∈ Fp

We also define the additive inverse this way.

a ∈ Fp implies that -fa ∈ Fp

-fa = (-a) % p

Again, for clarity, we use -f to distinguish field subtraction and negation from integer subtraction and negation.

In F19:

-f9 = (-9) % 19 = 10

Which means that:

9 +f 10 = 0

And that turns out to be true.

Similarly, we can do field subtraction.

a-fb = (a-b)%p where a, b ∈ Fp

In F19:

11-f9=(11-9)%19=2

6-f13=(6-13)%19=12

and so on.

Solve these problems in F57 (assume all +’s here are +f and -`s here -f)

44+33

9-29

17+42+49

52-30-38

In the class FieldElement we can now define __add__ and __sub__ methods.

The idea of these methods is that we want something like this to work:

>>>fromeccimportFieldElement>>>a=FieldElement(7,13)>>>b=FieldElement(12,13)>>>c=FieldElement(6,13)>>>(a+b==c)True

In Python we can define what addition (or + operator) means for our class with the __add__ method.

So how do we do this?

We combine what we learned above with modulo arithmetic and create a new method of the class FieldElement like so:

def__add__(self,other):ifself.prime!=other.prime:raiseTypeError('Cannot add two numbers in different Fields')num=(self.num+other.num)%self.primereturnself.__class__(num,self.prime)

We have to ensure that the elements are from the same Finite Field, otherwise this calculation doesn’t have any meaning.

Addition in a Finite Field is defined with the modulo operator, as explained above.

We have to return an instance of the class, which we can conveniently access with self.__class__.

We pass the two initializing arguments, num and self.prime for the __init__ method above.

Note that we can use FieldElement instead of self.__class__, but this would not make the method easily inheritable.

We will be subclassing FieldElement later, so making the method inheritable is important here.

Write the corresponding __sub__ method which defines the subtraction of two FieldElement objects.

Just as we defined a new addition (+f) for Finite Fields that was closed, we can also define a new multiplication for Finite Fields that’s also closed. By multiplying the same number many times, we can also define exponentiation. In this section, we’ll go through exactly how to define this using modulo arithmetic.

Multiplication is adding multiple times.

5⋅3 = 5+5+5 = 15

8⋅17 = 8+8+8+…(17 total 8’s)…+8 = 136

We can define multiplication on a Finite Field the same way. Operating in F19 once again,

5⋅f3 = 5+f5+f5

8⋅f17 = 8+f8+f8+f…(17 total 8’s)…+f8

We already know how to do the right side, and that yields a number within the F19 set:

5⋅f3 = 5+f5+f5 = 15 % 19 = 15

8⋅f17 = 8+f8+f8+f…(17 total 8’s)…+f8 = (8⋅17) % 19 = 136 % 19 = 3

Note that the second result is pretty unintuitive. We don’t normally think of 8⋅f17=3, but that’s part of what’s necessary in order to define multiplication to be closed. That is, the result of field multiplication is always in the set {0,1,…p-1}.

Exponentiation is simply multiplying a number many times.

73=7⋅f7⋅f7=343

In a Finite Field, we can do exponentiation using modulo arithmetic.

In F19:

73=343 % 19=1

912=7

Exponentiation again gives us counter-intuitive results. We don’t normally think 73=1 or 912=7. Again, Finite Fields have to be defined so that the operations always result in a number within the field.

Solve the following equations in F97 (again, assume ⋅ and exponentiation are field versions):

95⋅45⋅31

17⋅13⋅19⋅44

127⋅7749

For k = 1, 3, 7, 13, 18, what is this set in F19?

{k⋅0, k⋅1, k⋅2, k⋅3, … k⋅18}

Do you notice anything about these sets?

The answer to Exercise 5 is why fields have to have a prime power number of elements. No matter what k you choose, as long as it’s greater than 0, multiplying the entire set by k will result in the same set as you started with.

Intuitively the fact that we have a prime order results in every element of a Finite Field being equivalent. If the order of the set was composite number, multiplying the set by one of the divisors would result in a smaller set.

Now that we understand what multiplication should be in FieldElement, we want to define the __mul__ method which overrides the * operator.

We want this to work:

>>>fromeccimportFieldElement>>>a=FieldElement(3,13)>>>b=FieldElement(12,13)>>>c=FieldElement(10,13)>>>(a*b==c)True

As we did with addition and subtraction above, the next exercise is to make multiplication work for our class by defining the __mul__ method.

Write the corresponding __mul__ method which defines the multiplication of two Finite Field elements.

We need to define the exponentiation for FieldElement, which in Python can be defined with the __pow__ method, overriding the ** operator.

The difference here is that the exponent is not a FieldElement, so has to be treated a bit differently.

We want something like this to work:

>>>fromeccimportFieldElement>>>a=FieldElement(3,13)>>>b=FieldElement(1,13)>>>(a**3==b)True

Note that because the exponent is an integer, instead of another instance of FieldElement, the method receives the variable exponent as an integer.

We can code it this way.

classFieldElement:...def__pow__(self,exponent):num=(self.num**exponent)%self.primereturnself.__class__(num,self.prime)

This is a perfectly fine way to do it, but pow(self.num, exponent, self.prime) is more efficient.

We have to return an instance of the class as before.

Why don’t we force the exponent to be a FieldElement object?

It turns out that the exponent doesn’t have to be a member of the Finite Field in order for the math to work out.

In fact, if it were, the exponents wouldn’t display the intuitive behavior we would expect from exponents, like being able to add the exponents when you multiply with the same base.

Some of what we’re doing now may seem slow for large numbers, but we’ll use some clever tricks to improve the performance of these algorithms.

For p = 7, 11, 17, 31, what is this set in Fp?

{1(p-1), 2(p-1), 3(p-1), 4(p-1), … (p-1)(p-1)}

The intuition that helps us with addition, subtraction, multiplication and perhaps even exponentiation unfortunately doesn’t help us quite as much in division. Because division is the hardest one to make sense of, we’ll start with something that should make sense.

In normal math, division is the inverse of multiplication:

7⋅8 = 56 implies that 56/8 = 7

12⋅2 = 24 implies that 24/12 = 2

And so on. We can use this as the definition of division to help us. Note that like normal math, you cannot divide by 0.

In F19, we know that:

3⋅f7=21%19=2 implies that 2/f7=3

9⋅f5=45%19=7 implies that 7/f5=9

This is very unintuitive as we generally think of 2/f7 or 7/f5 as fractions, not nice Finite Field elements. Yet that is one of the remarkable things about Finite Fields: Finite Fields are closed under division. That is, dividing any two numbers where the denominator is not 0 will result in another Finite Field element.

The question you might be asking yourself is, how do I calculate 2/f7 if I don’t know beforehand that 3⋅f7=2? This is indeed a very good question and in order to answer it, we’ll have to use the result from the Exercise 7.

In case you didn’t get it, the answer is that n(p-1) is always 1 for every p that is prime and every n > 0. This is a beautiful result from number theory called Fermat’s Little Theorem. Essentially, the theorem says:

n(p-1)%p=1 where p is prime

Since we are operating in prime fields, this will always be true.

Because division is the inverse of multiplication, we know:

a/b=a⋅f(1/b)=a⋅fb-1

We can reduce the division problem to a multiplication problem as long as we can figure out what b-1 is. This is where Fermat’s Little Theorem comes into play. We know:

b(p-1)=1

Because p is prime. Thus:

b-1=b-1⋅f1=b-1⋅fb(p-1)=b(p-2)

or

b-1=b(p-2)

In F19, this means practically that:

b18=1 which means that b-1=b17 for all b > 0.

So in other words, we can calculate the inverse using the exponentiation operator. In F19:

2/7=2⋅7(19-2)=2⋅717=465261027974414%19=3

7/5=7⋅5(19-2)=7⋅517=5340576171875%19=9

This is a relatively expensive calculation as exponentiating grows very fast.

Division is the most expensive operation for that reason.

To lessen the expensiveness, we can utilize the pow function in Python.

pow is a function that does exponentiation.

Thus something like pow(7,17) does the same thing as 7**17.

The pow function, however, has an optional third argument which makes our calculation more efficient.

Specifically, pow will modulo by the third argument.

Thus, pow(7,17,19) will give the same result as 7**17%19 but do so faster because the modulo function is done after each round of multiplication.

Solve the following equations in F31:

3 / 24

17-3

4-4⋅11

Write the corresponding __truediv__ method which defines the division of two field elements.

Note that in Python3, division is separated into __truediv__ and __floordiv__. The first does normal division, the second does integer division.

One last thing that we need to take care of before we leave this chapter is the __pow__ method, which will need to take care of negative exponents.

For example a-3 needs to be a Finite Field element, but the current code does not take care of this case.

We want, for example something like this to work:

>>>fromeccimportFieldElement>>>a=FieldElement(7,13)>>>b=FieldElement(8,13)>>>(a**-3==b)True

Unfortunately, the way we’ve defined __pow__ simply doesn’t handle negative exponents as the second parameter of the built-in Python function pow is required to be positive.

Thankfully, we can use some math we already know to solve this. We know from Fermat’s Little Theorem that:

ap-1 = 1

This fact means that we can multiply by ap-1 as many times as we want. So for a-3, for example, we can do:

a-3=a-3⋅ap-1=ap-4

This is a way we can do negative exponents. A naive implementation would do something like this:

classFieldElement:...def__pow__(self,exponent):n=exponentwhilen<0:n+=self.prime-1num=pow(self.num,n,self.prime)returnself.__class__(num,self.prime)

Thankfully, we can do even better.

We already know how to force a number out of being negative, using our familiar friend %!

As a bonus, we can also reduce very large exponents at the same time given that ap-1=1.

This will make the pow function not work as hard.

classFieldElement:...def__pow__(self,exponent):n=exponent%(self.prime-1)num=pow(self.num,n,self.prime)returnself.__class__(num,self.prime)

In this chapter we learned about Finite Fields and how to implement it in Python. We’ll be using Finite Fields in Chapter 3 for Elliptic Curve Cryptography. We turn next to the other mathematical component that we need for Elliptic Curve Cryptography and that’s Elliptic Curves.

In this chapter we’re going to learn about Elliptic Curves. In the Chapter 3, we will combine Elliptic Curves with Finite Fields to make Elliptic Curve Cryptography.

As in the Chapter 1, Elliptic Curves can look intimidating if you haven’t seen them before. Also as in Chapter 1, the actual math isn’t very difficult. Most of Elliptic Curves could have been taught to you after Algebra. In this chapter, we’ll get to what these curves are and what we can do with them.

Elliptic Curves are like many equations you’ve been seeing since pre-Algebra.

They have y on one side and x on the other in some form.

Elliptic Curves have a form like this:

y2=x3+ax+b

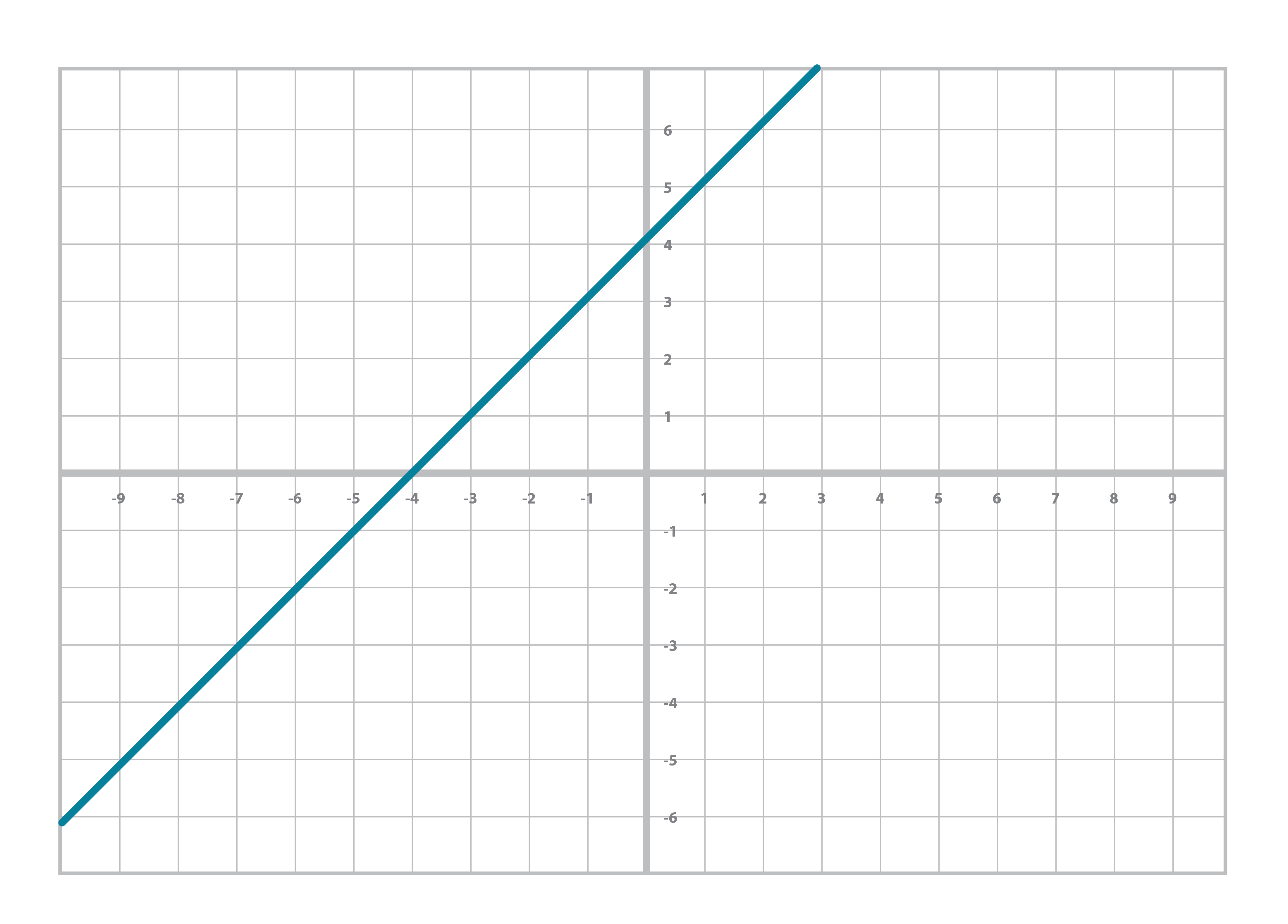

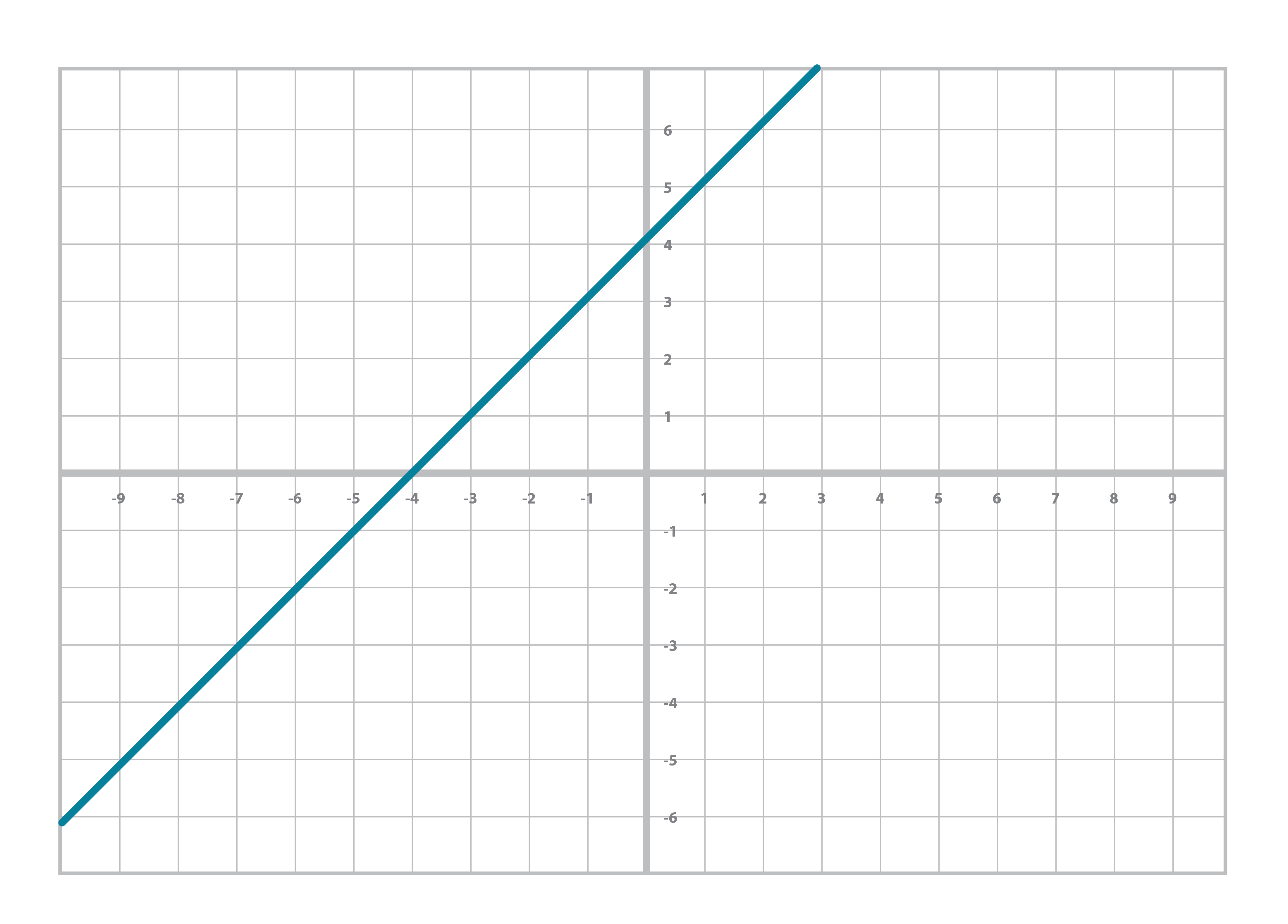

You’ve worked with other equations that look similar. For example, you probably learned the linear equation back in pre-Algebra:

y = mx + b

You may even remember that m here has the name slope and b, y-intercept. You can also graph linear equations like Figure 2-1:

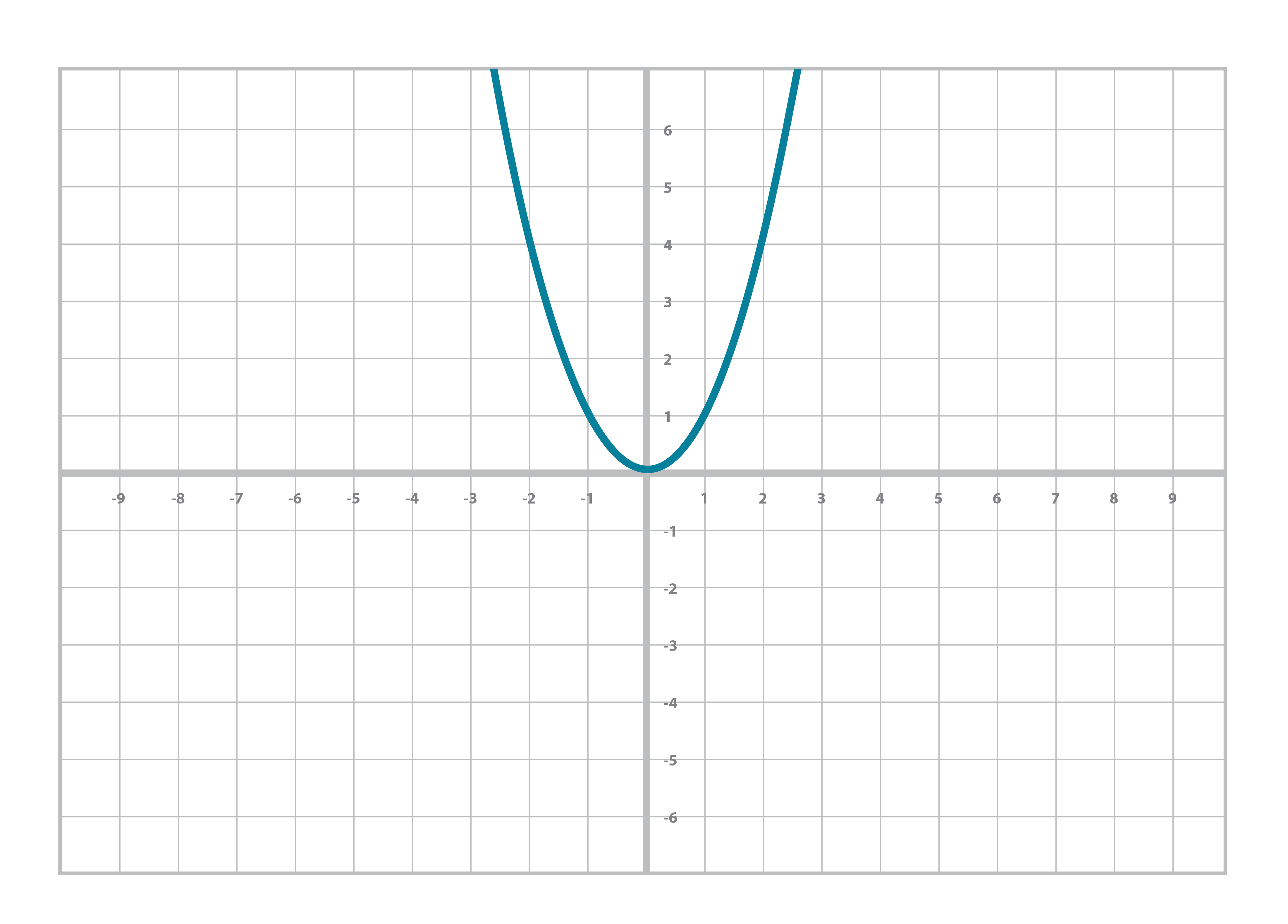

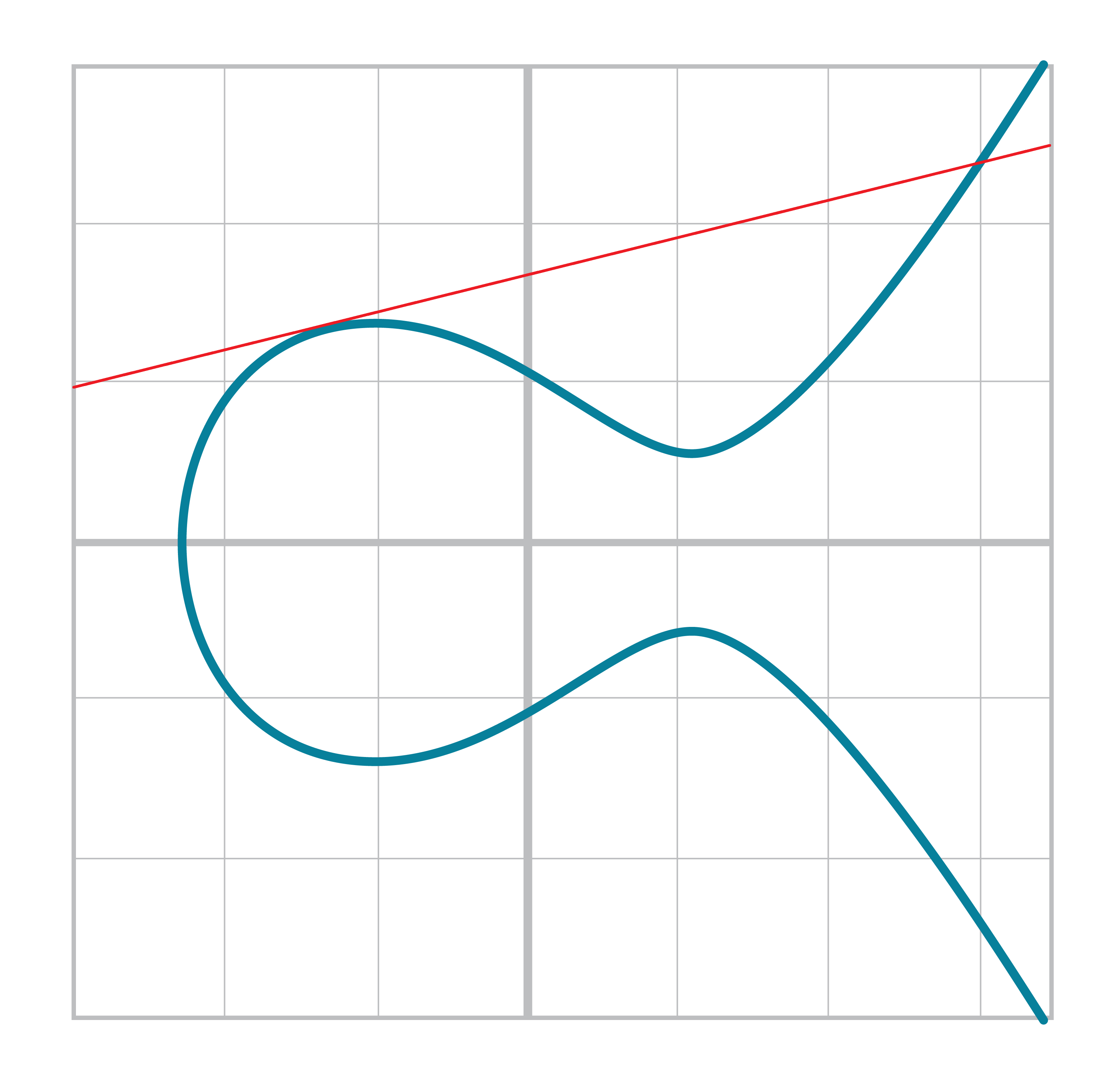

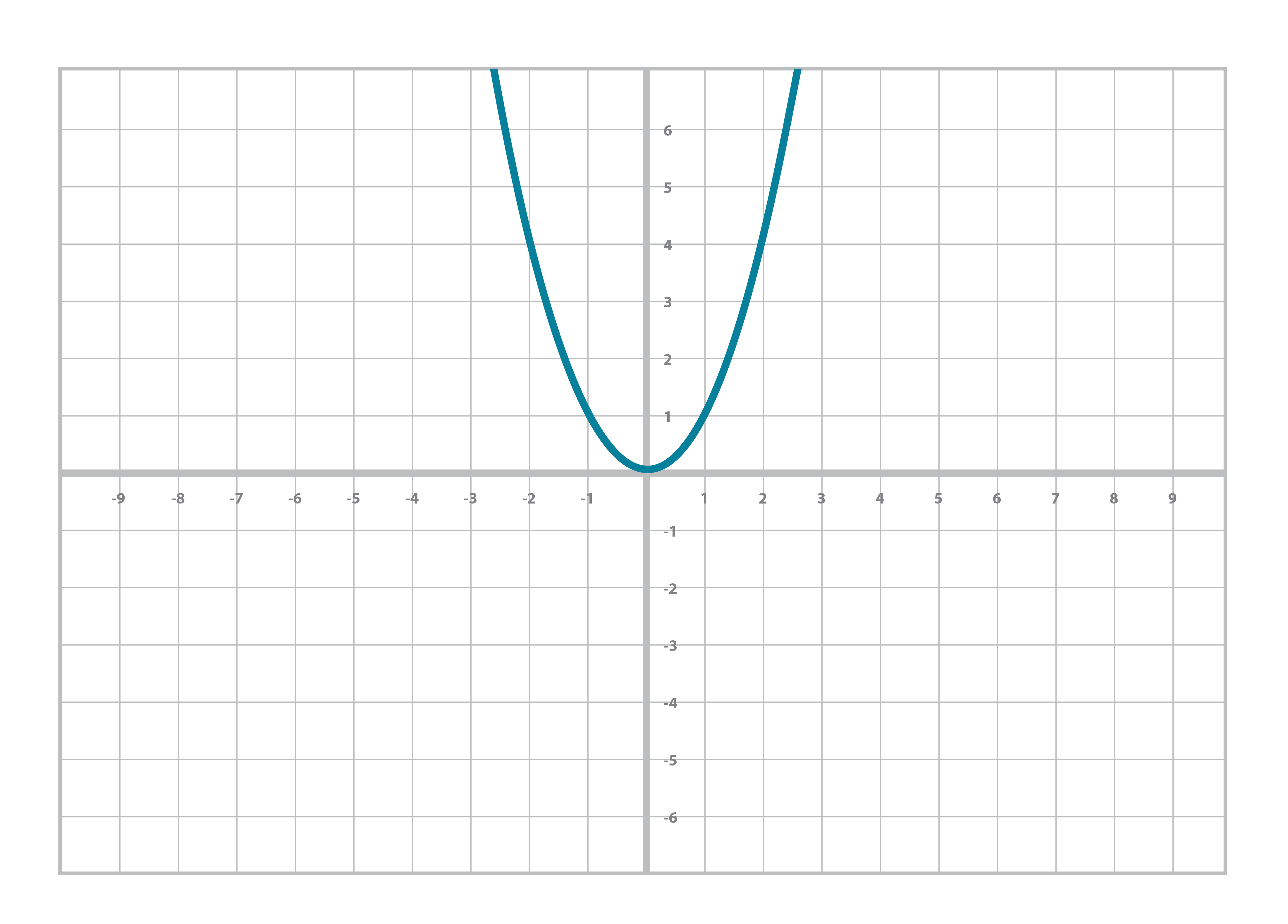

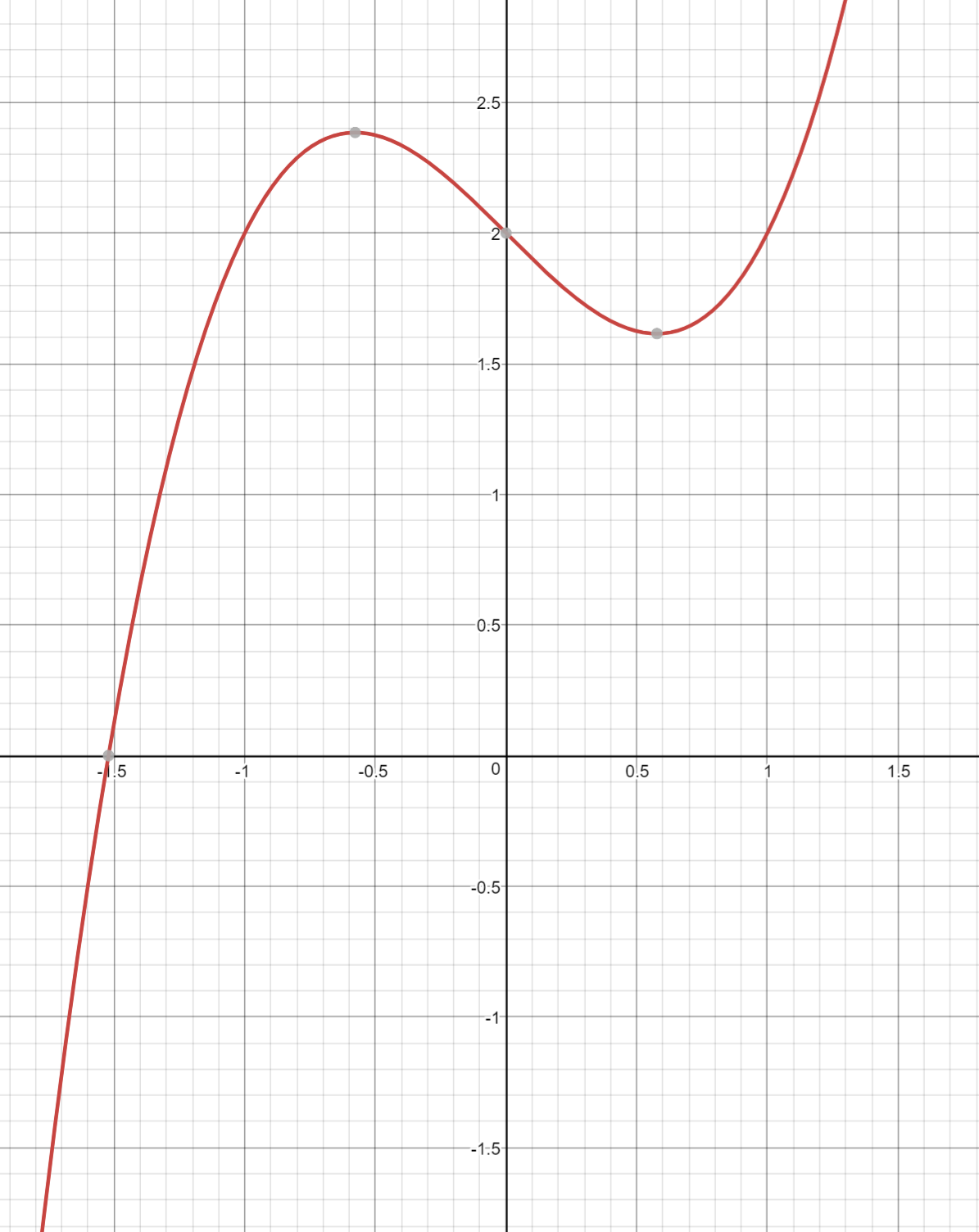

Similarly, you’re probably familiar with the quadratic equation and its graph (Figure 2-2):

y = ax2+bx+c

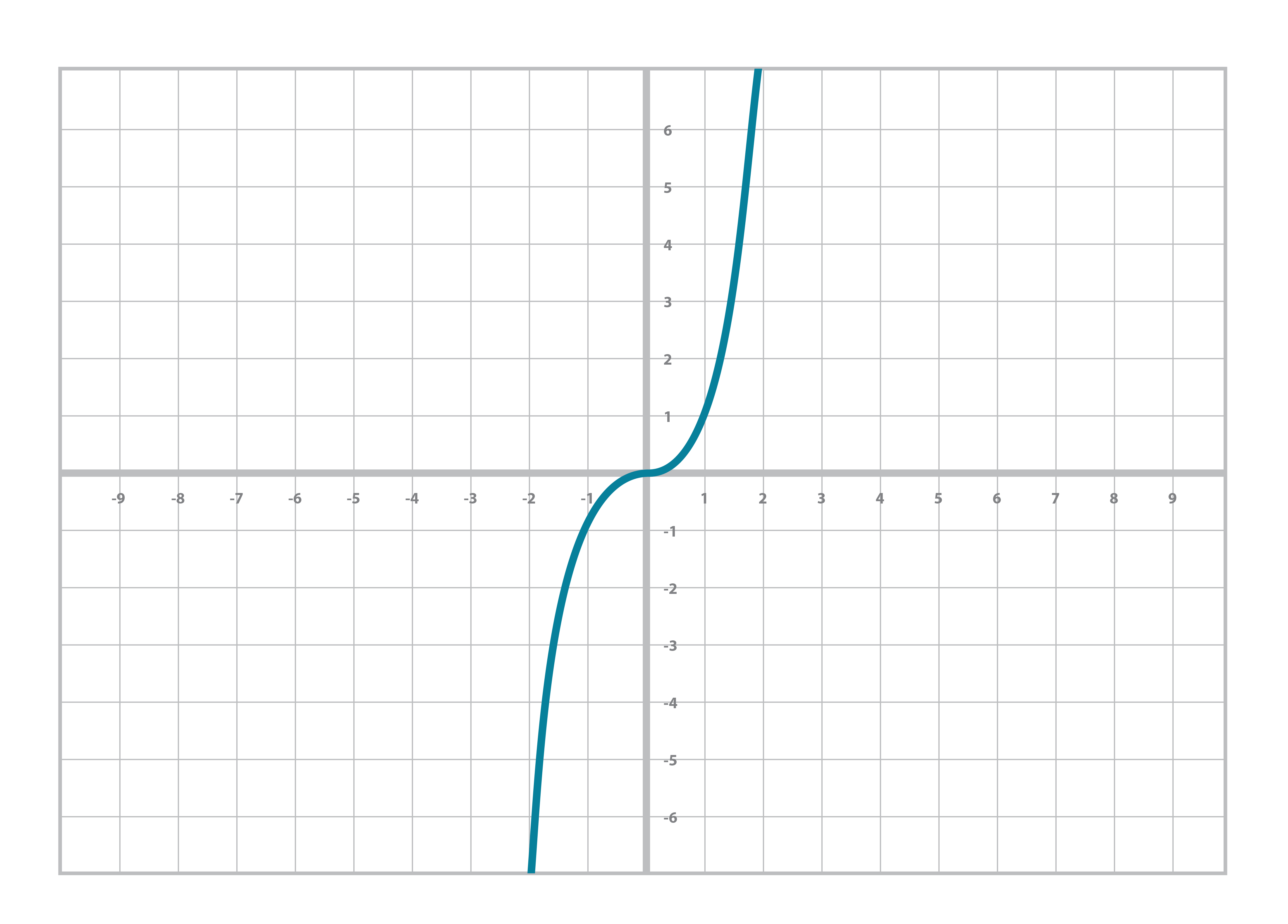

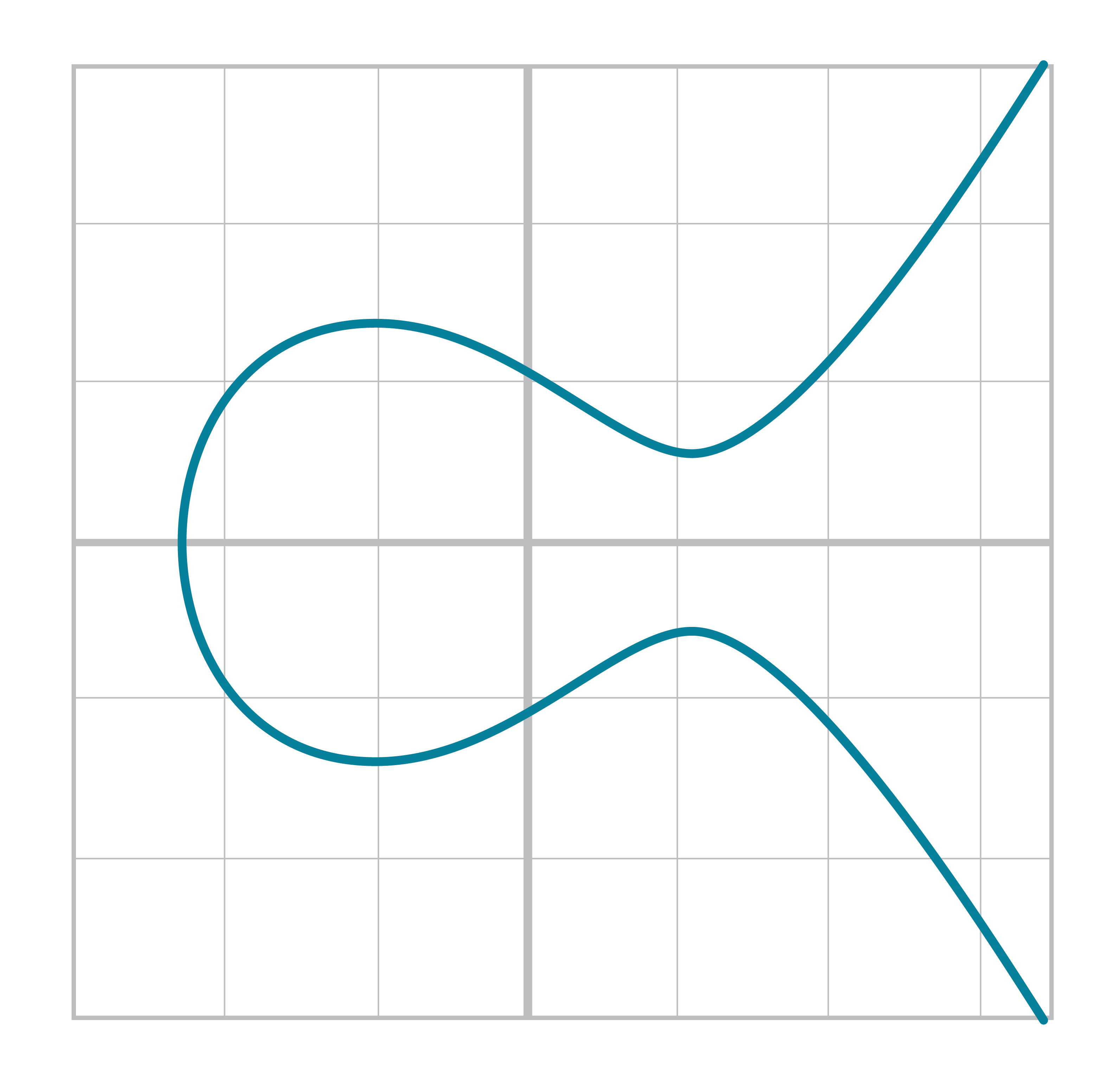

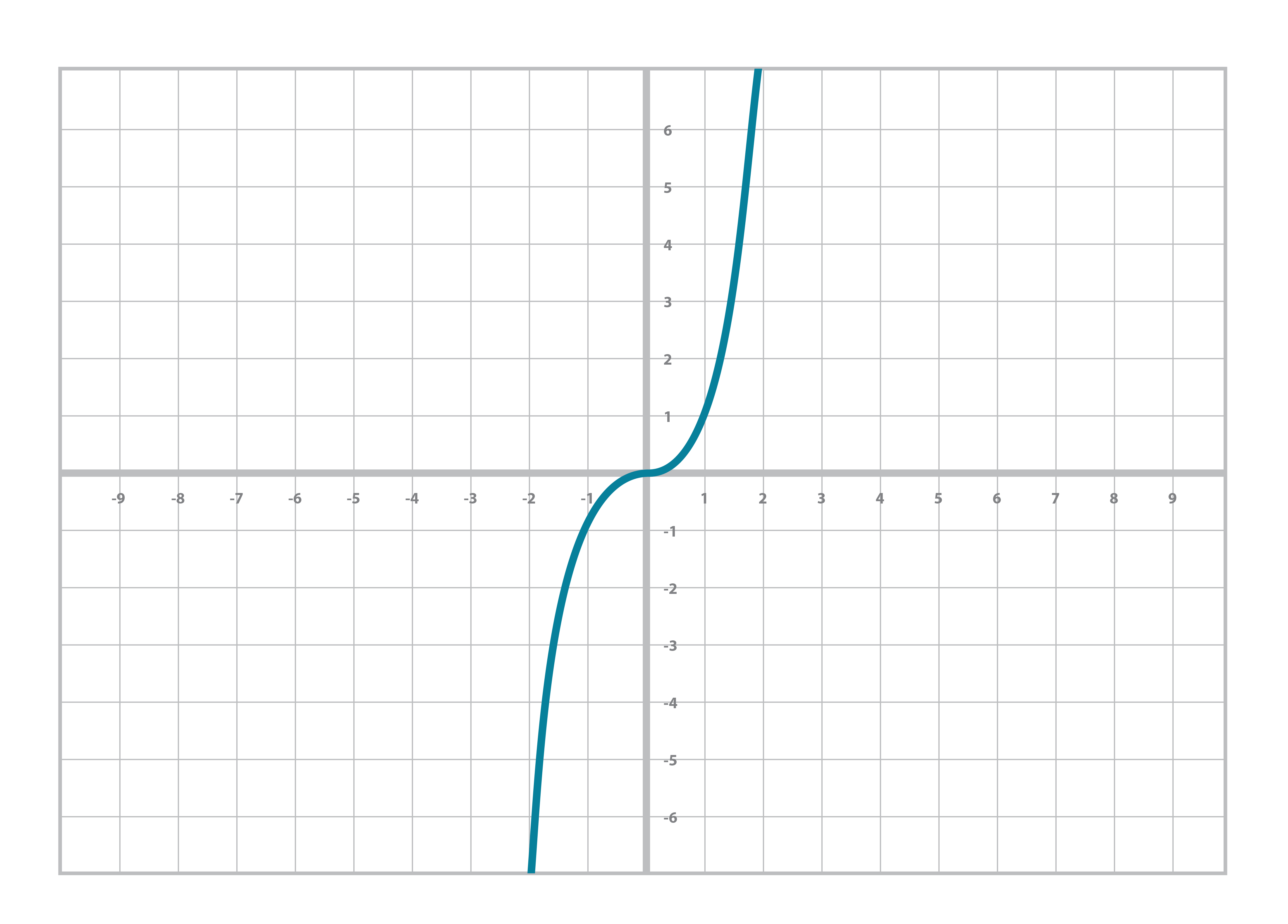

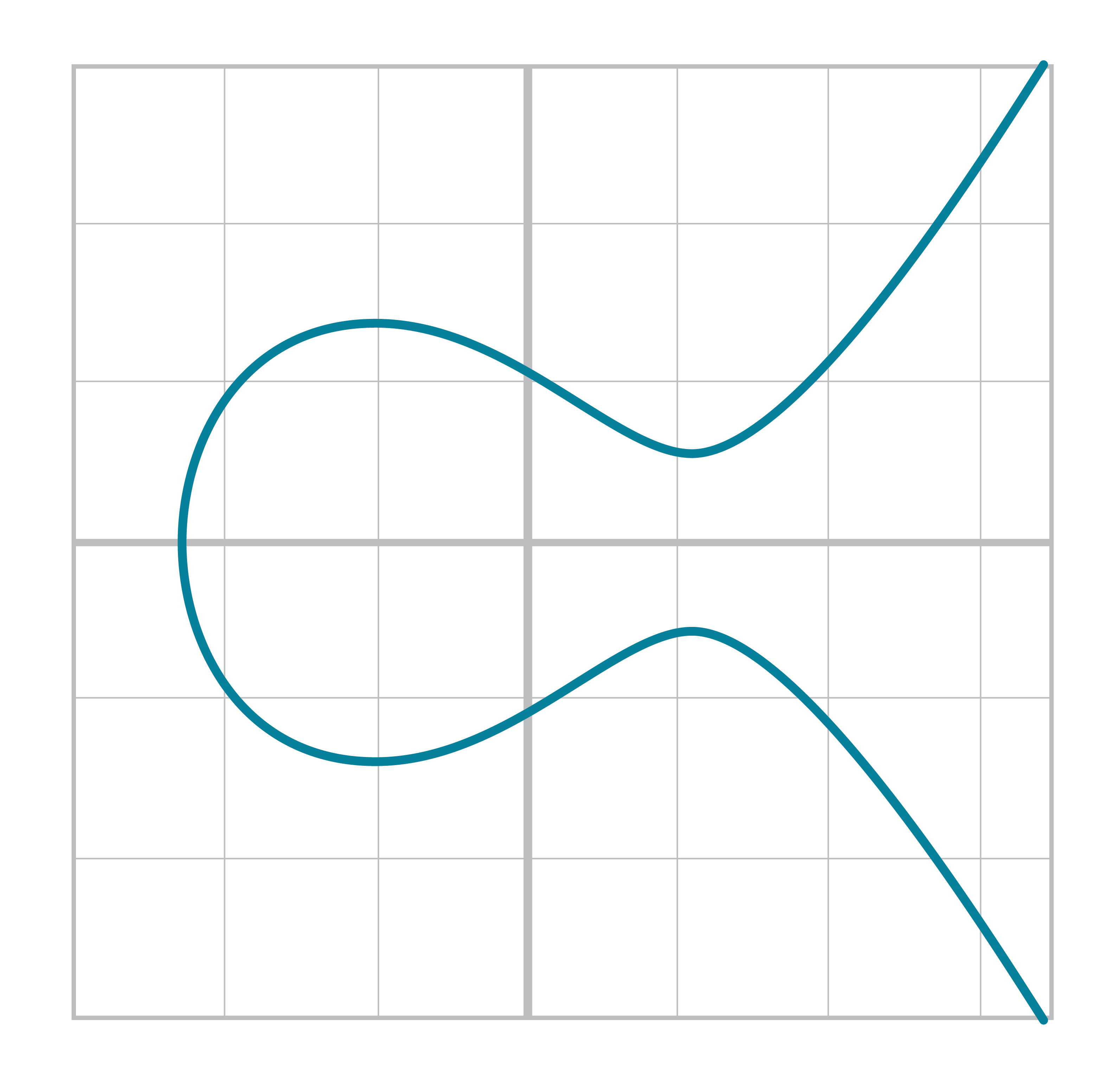

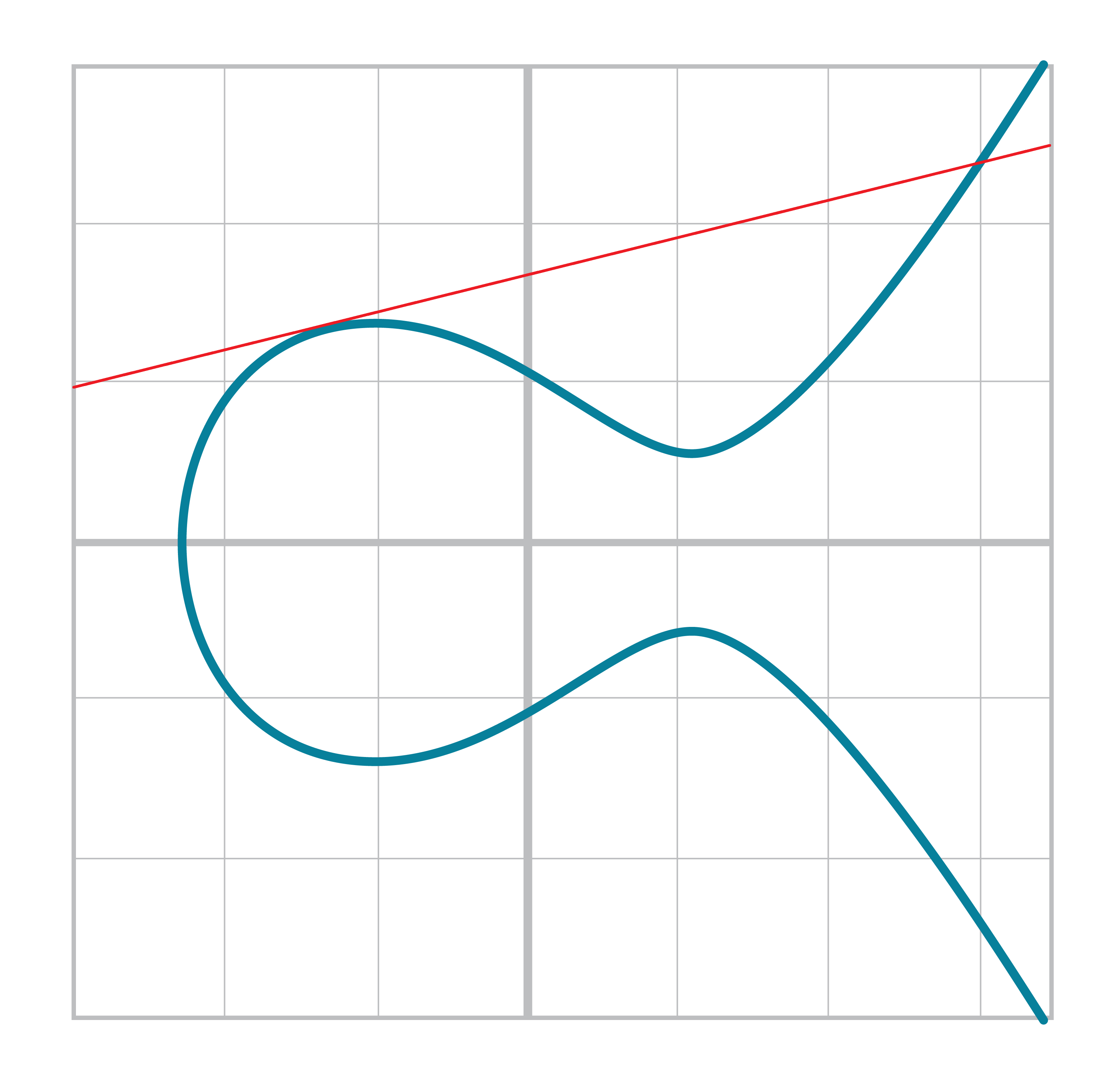

And sometime around Algebra, you did even higher orders of x, something called the cubic equation and its graph (Figure 2-3):

y = ax3+bx2+cx+d

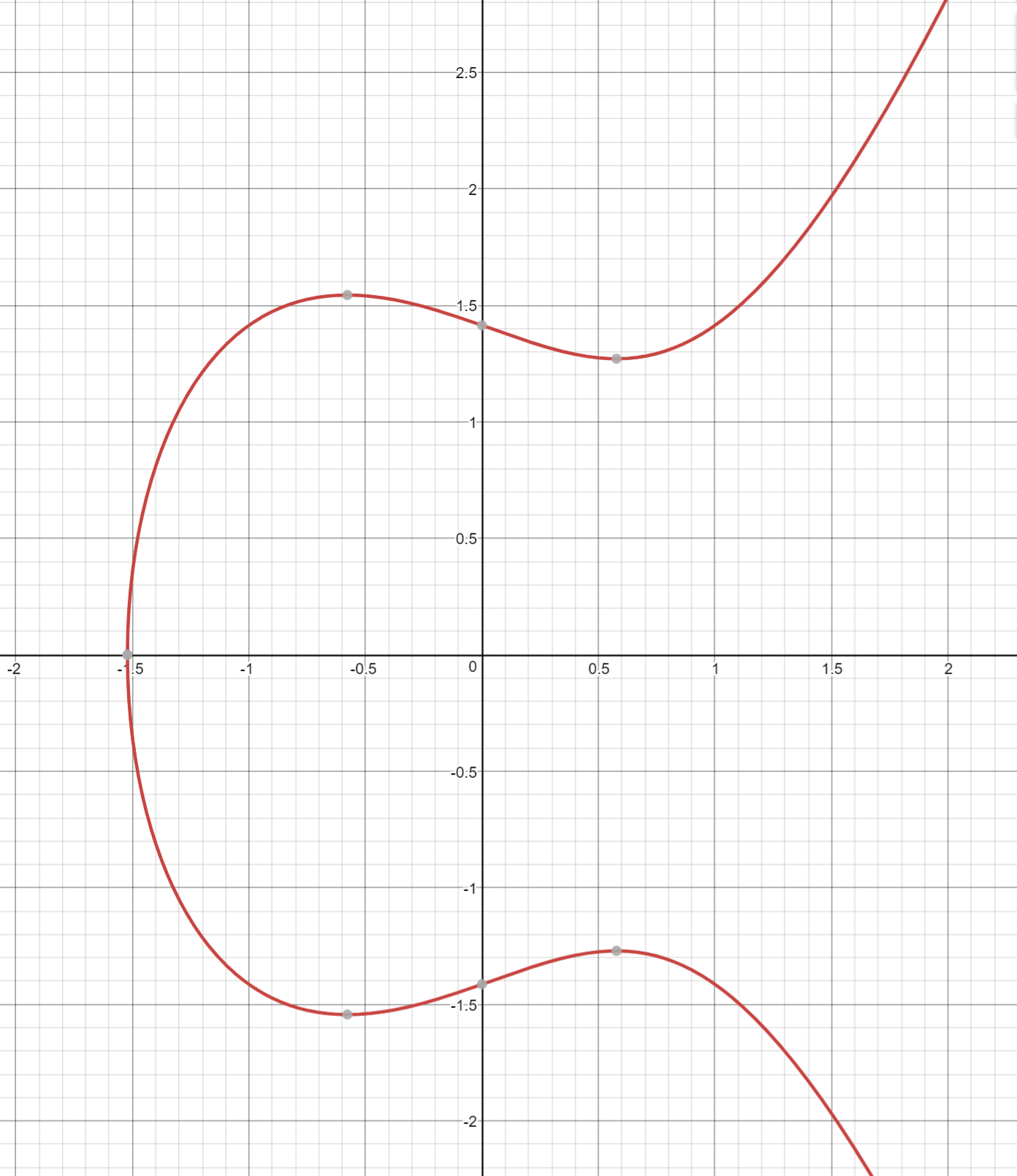

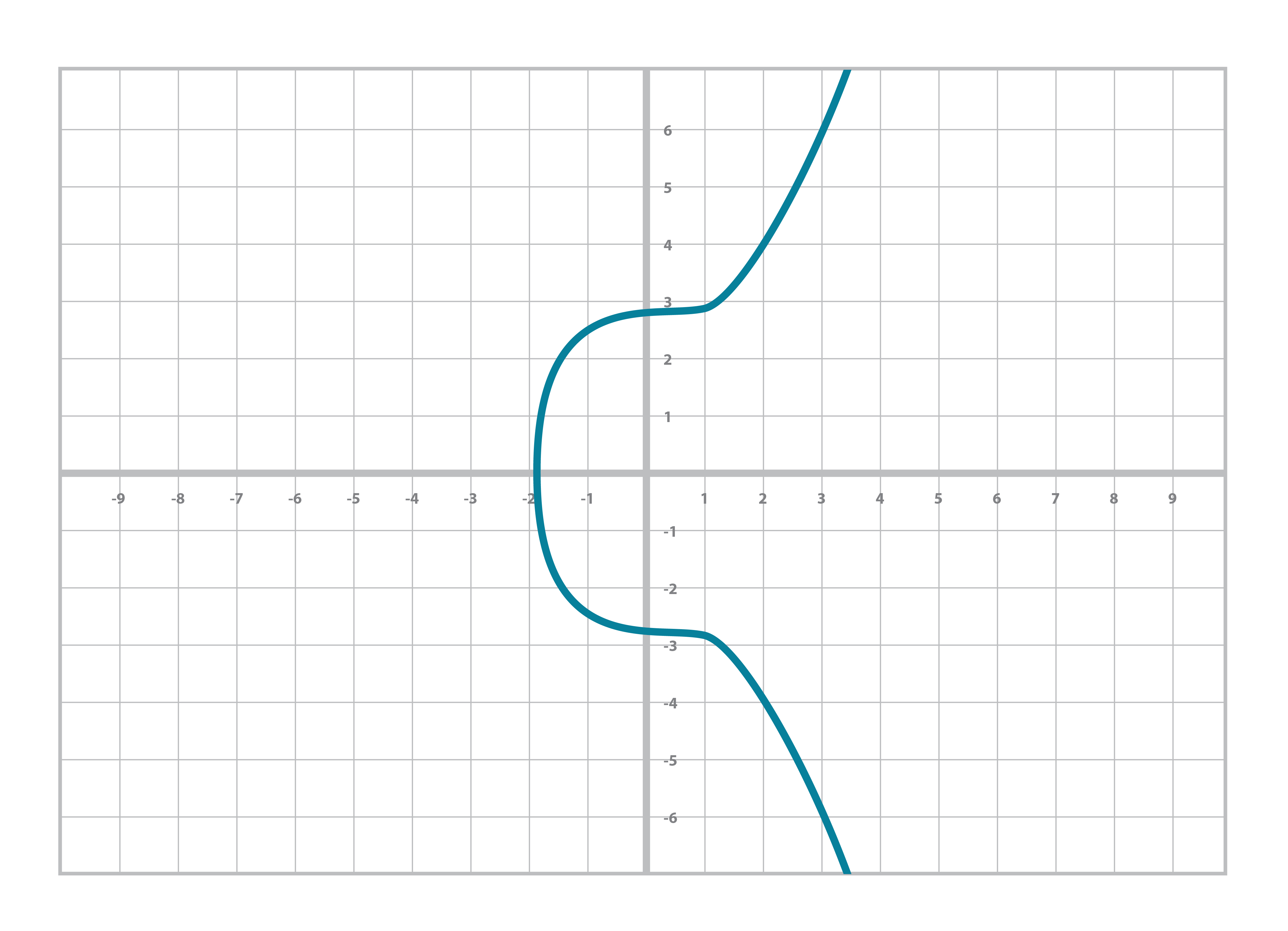

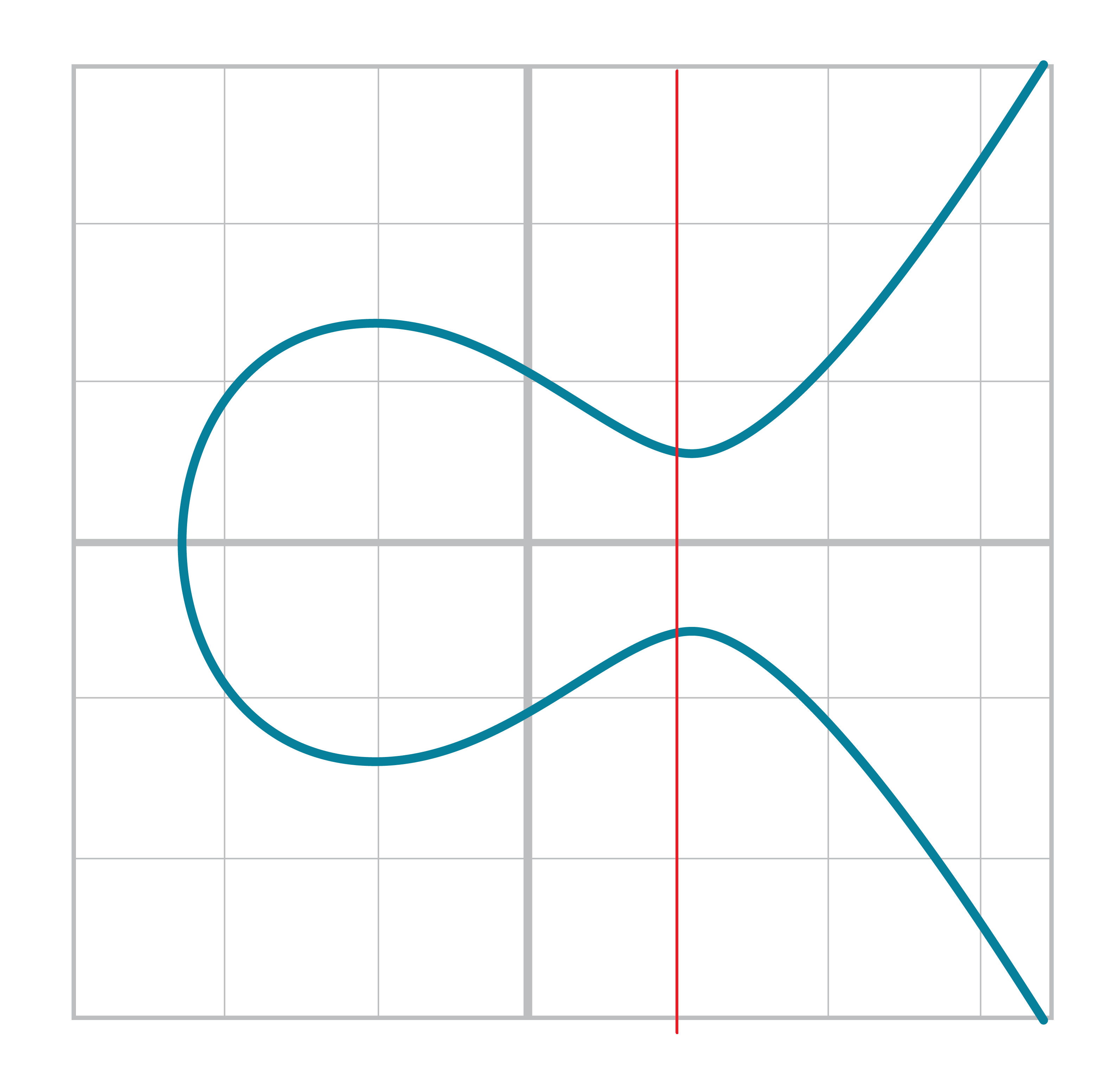

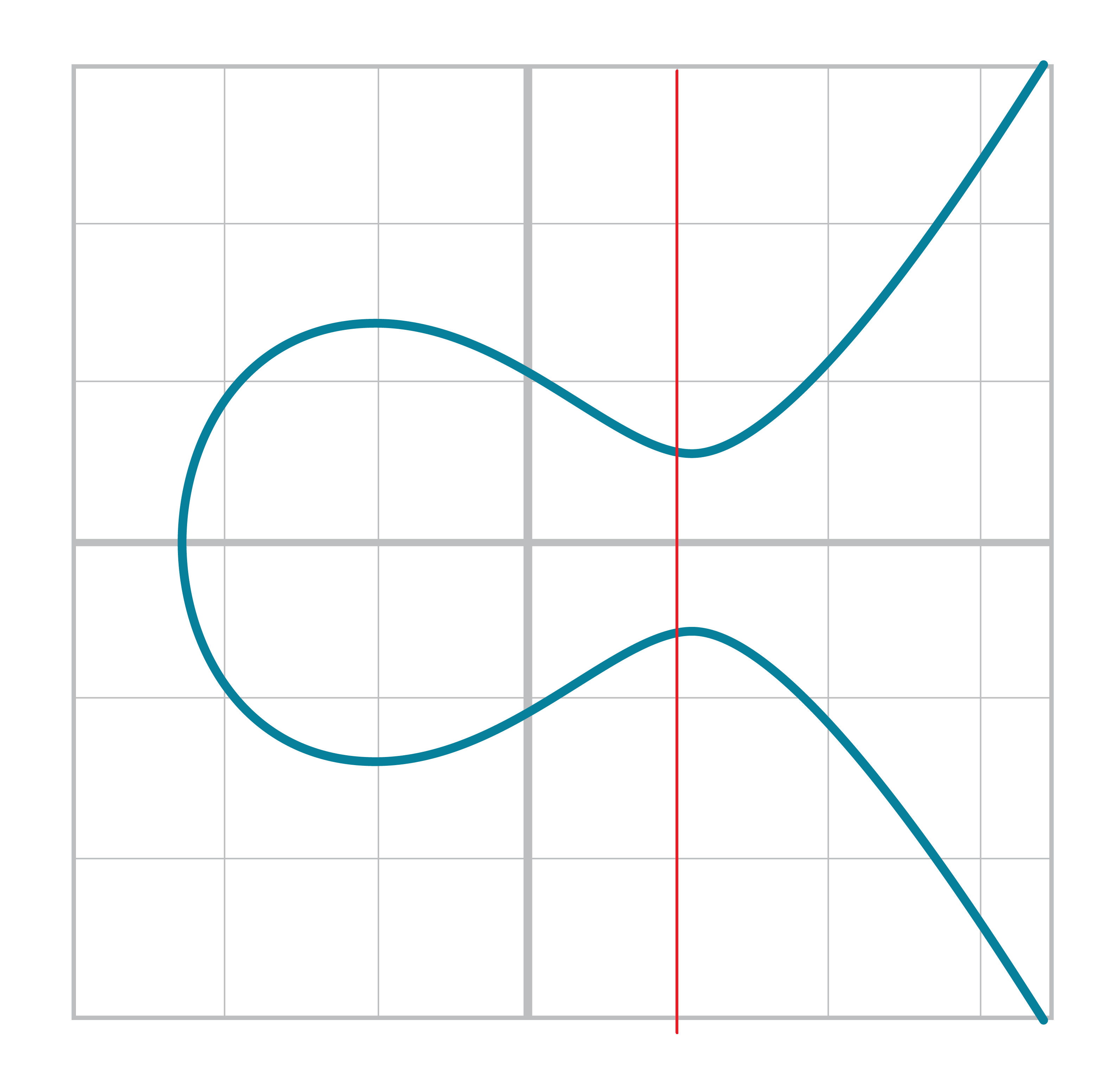

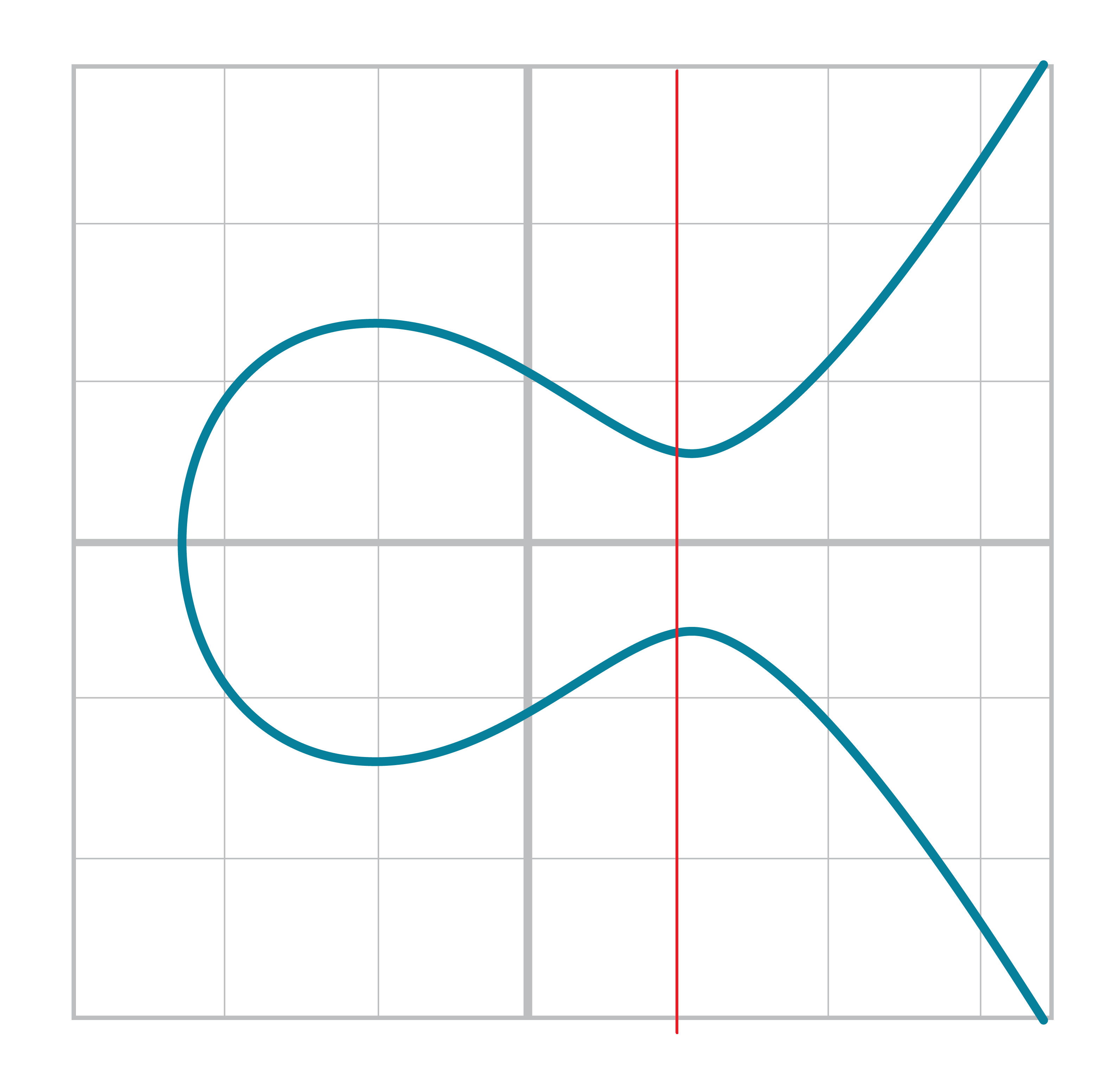

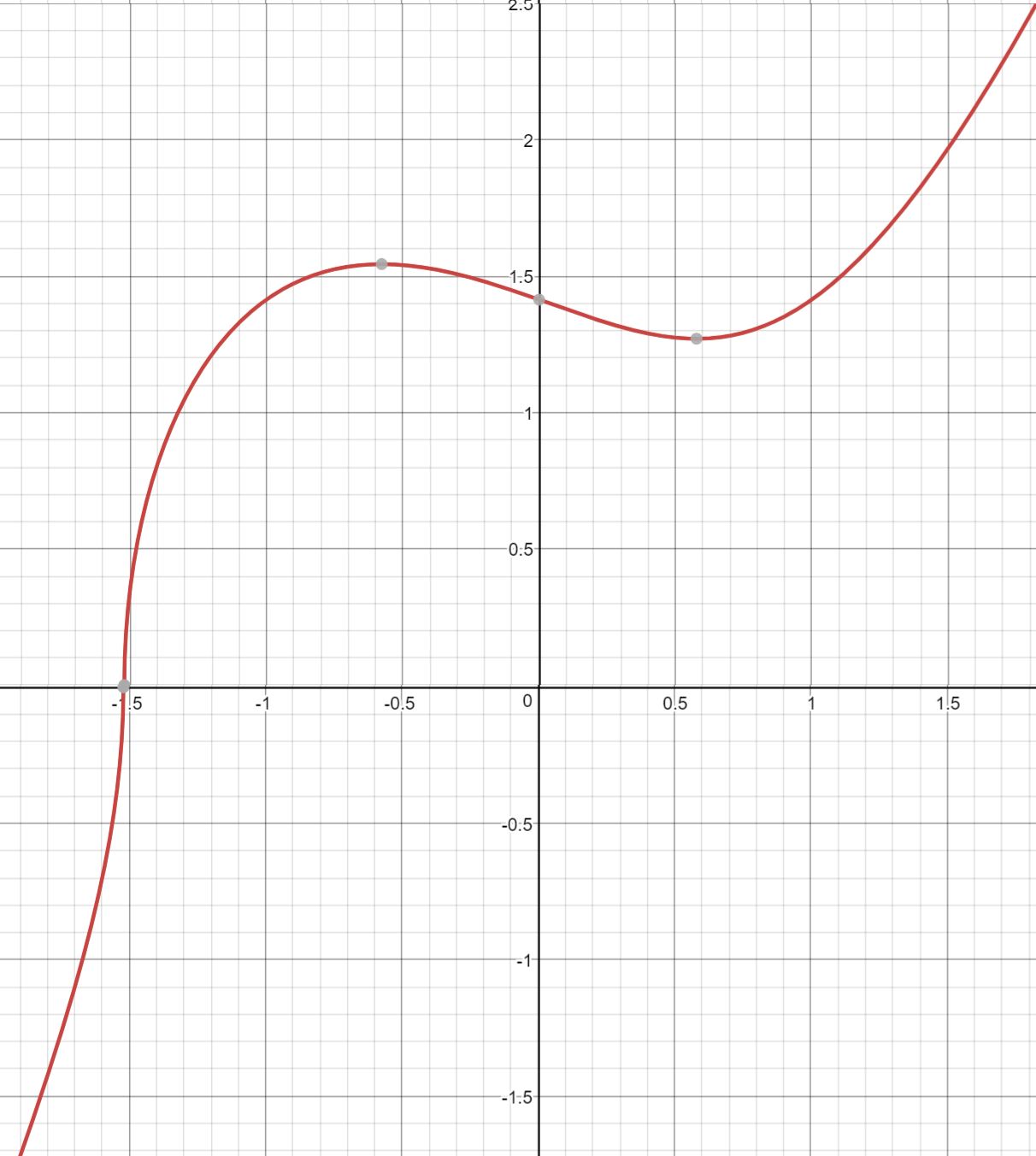

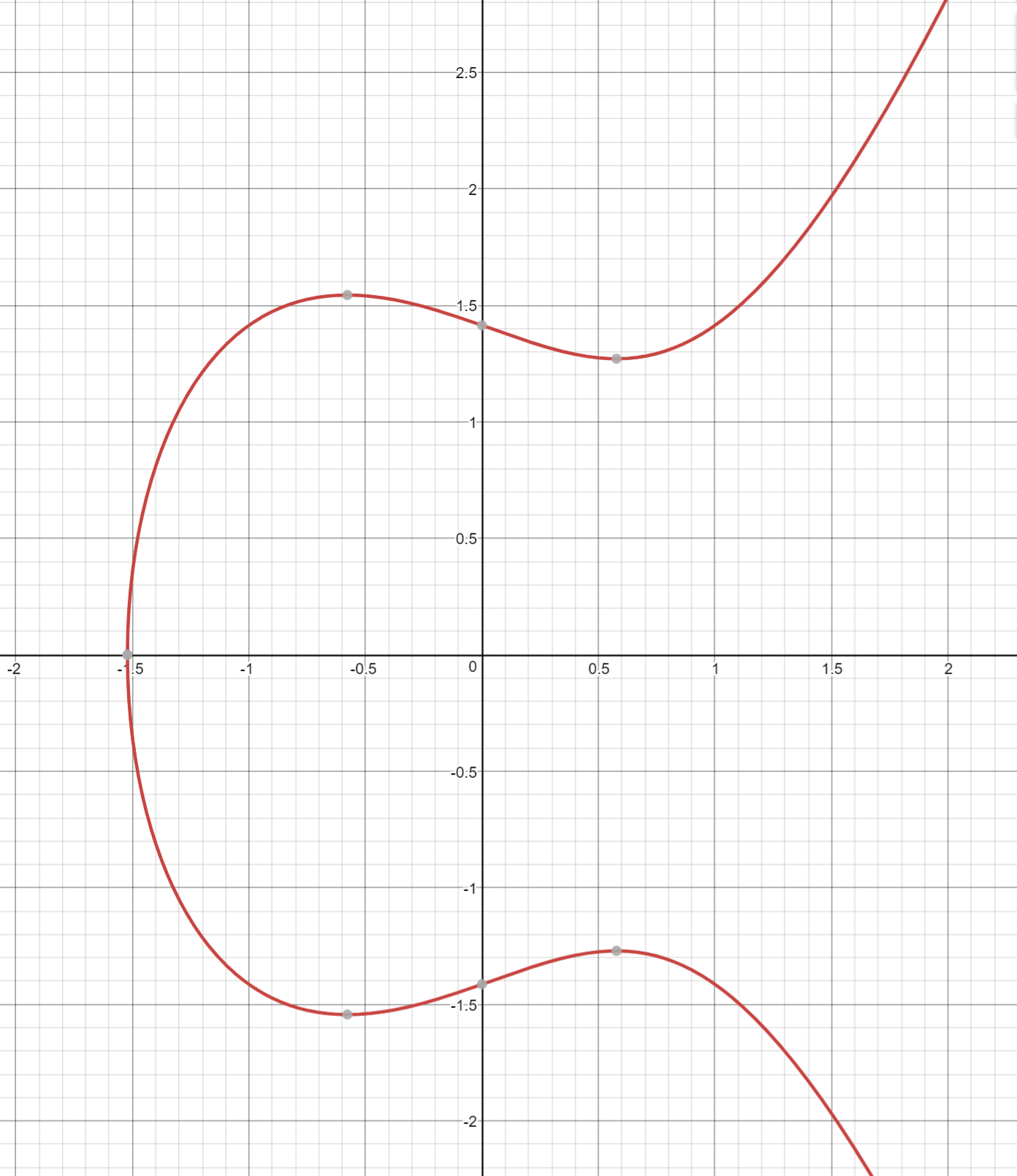

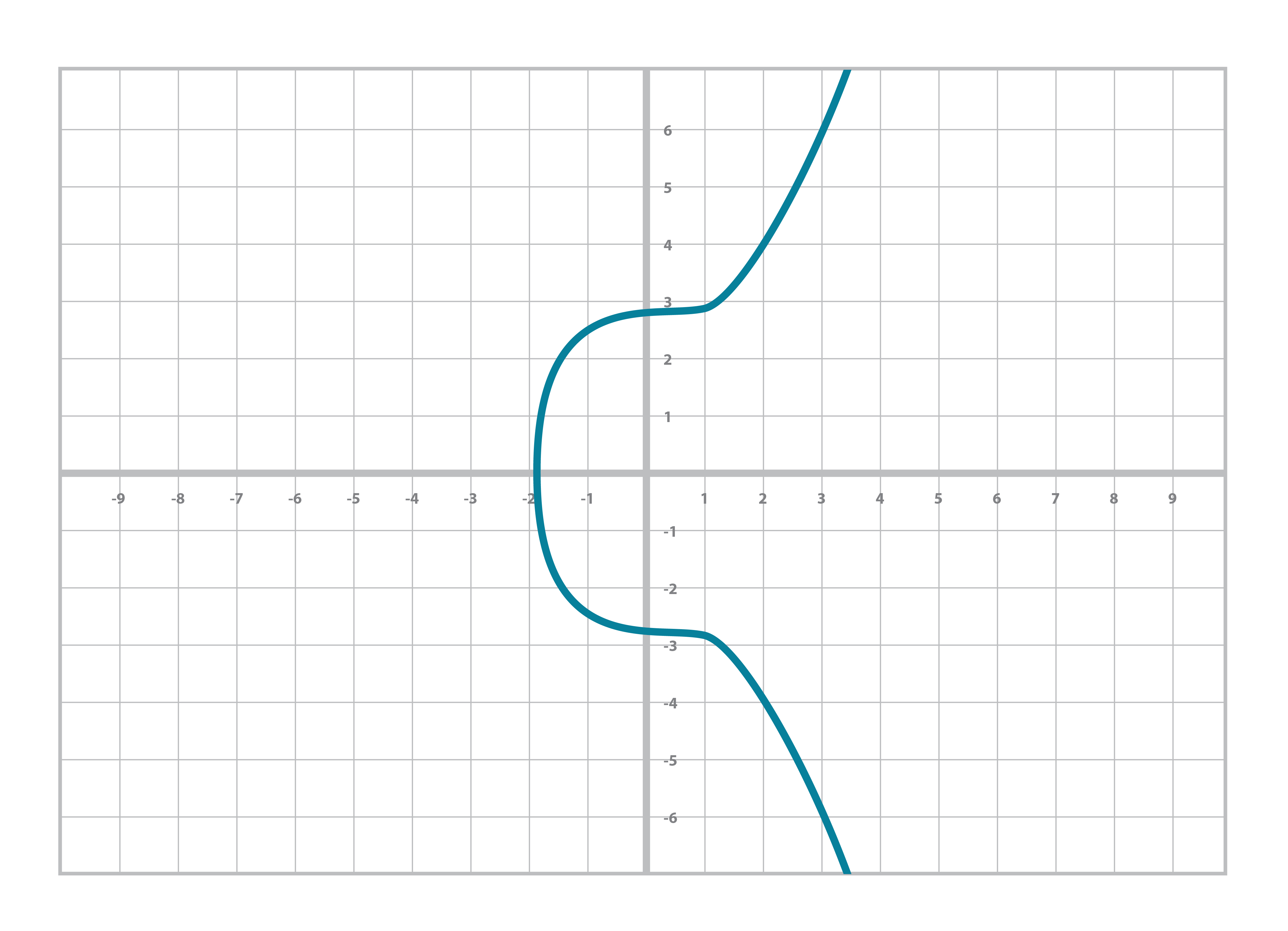

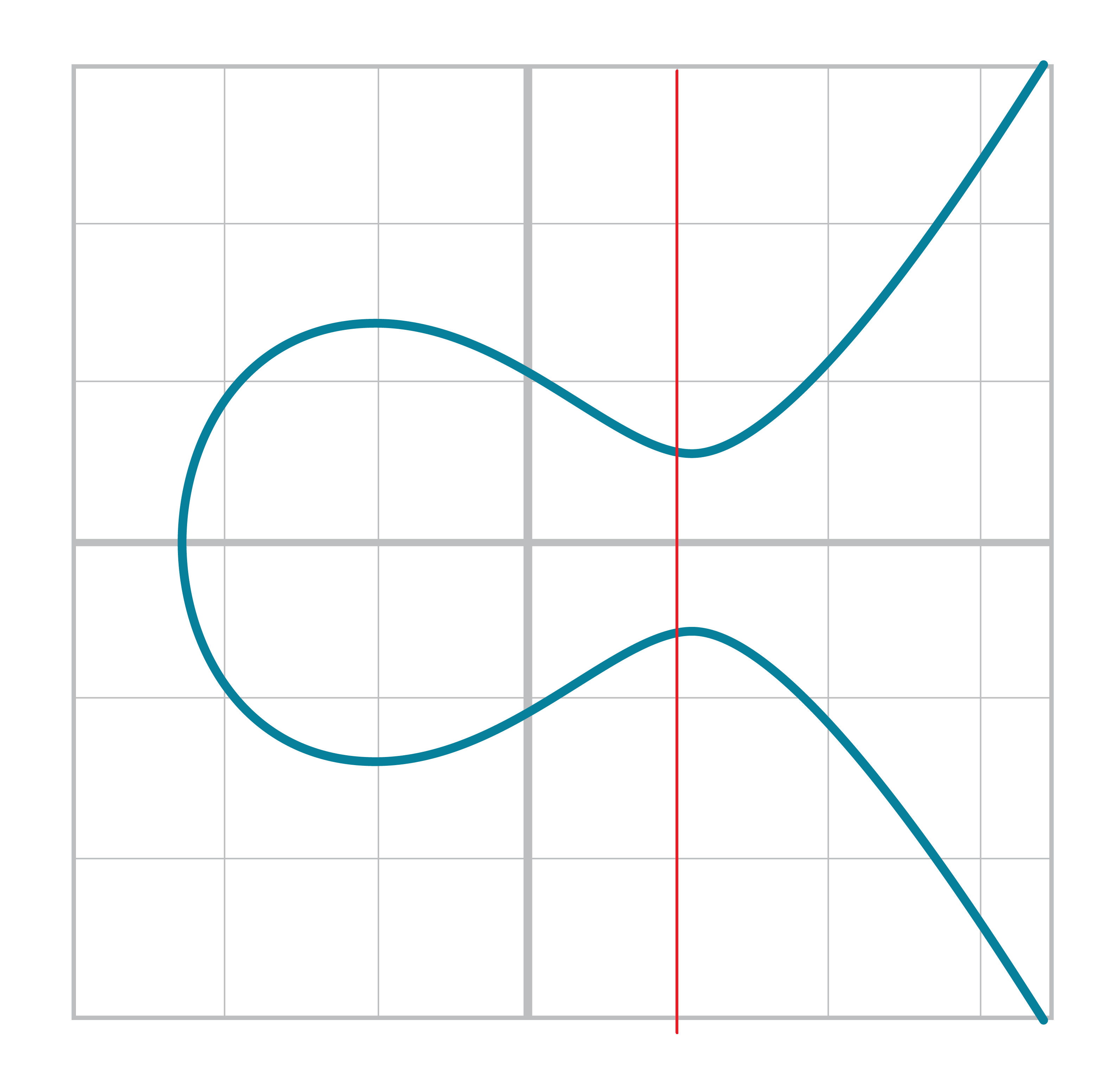

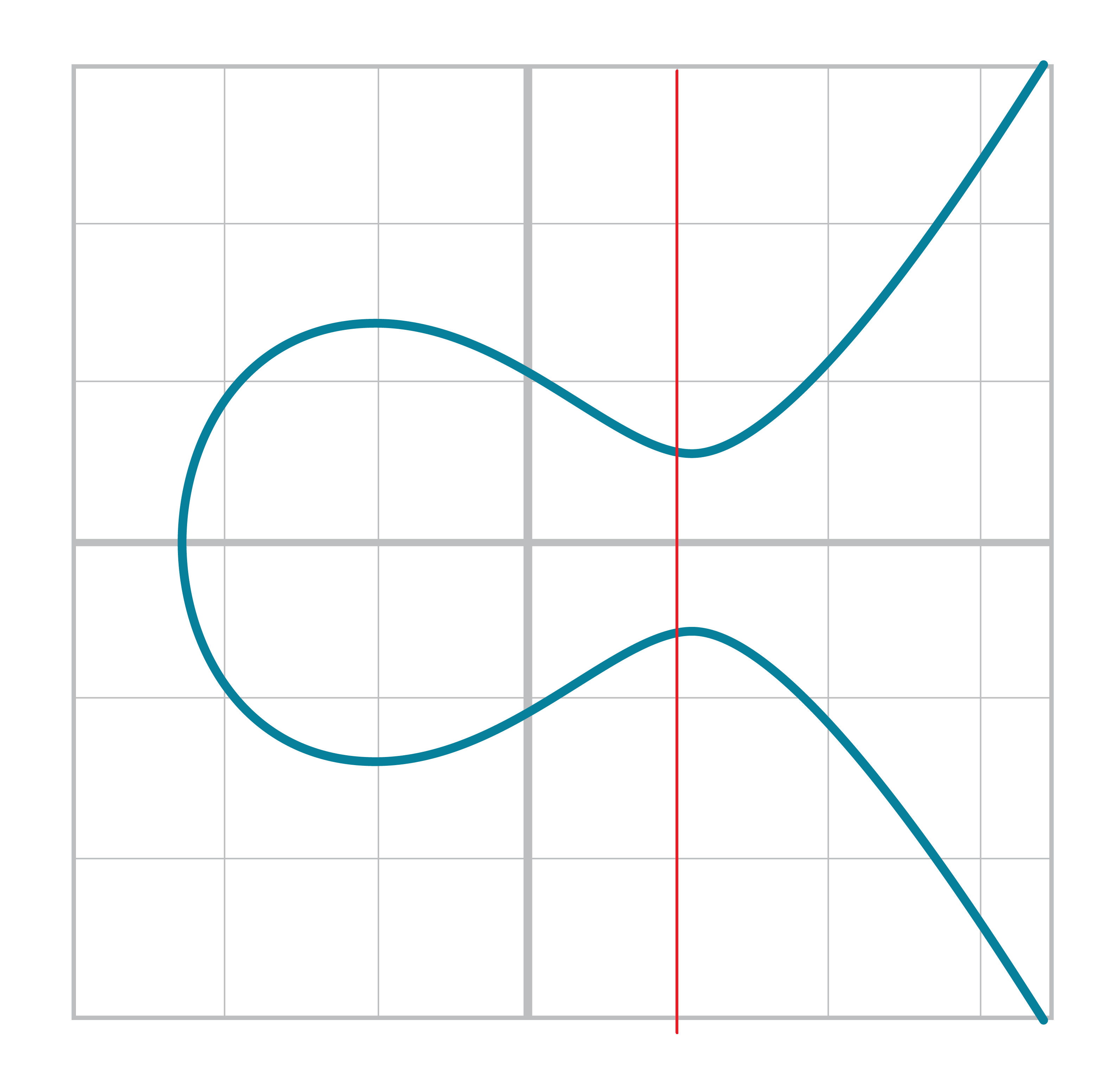

An Elliptic Curve isn’t all that different. The only real difference between the Elliptic Curve and the cubic curve above is the y2 term on the left side. This has the effect of making the graph symmetric over the x-axis, shown in Figure 2-4:

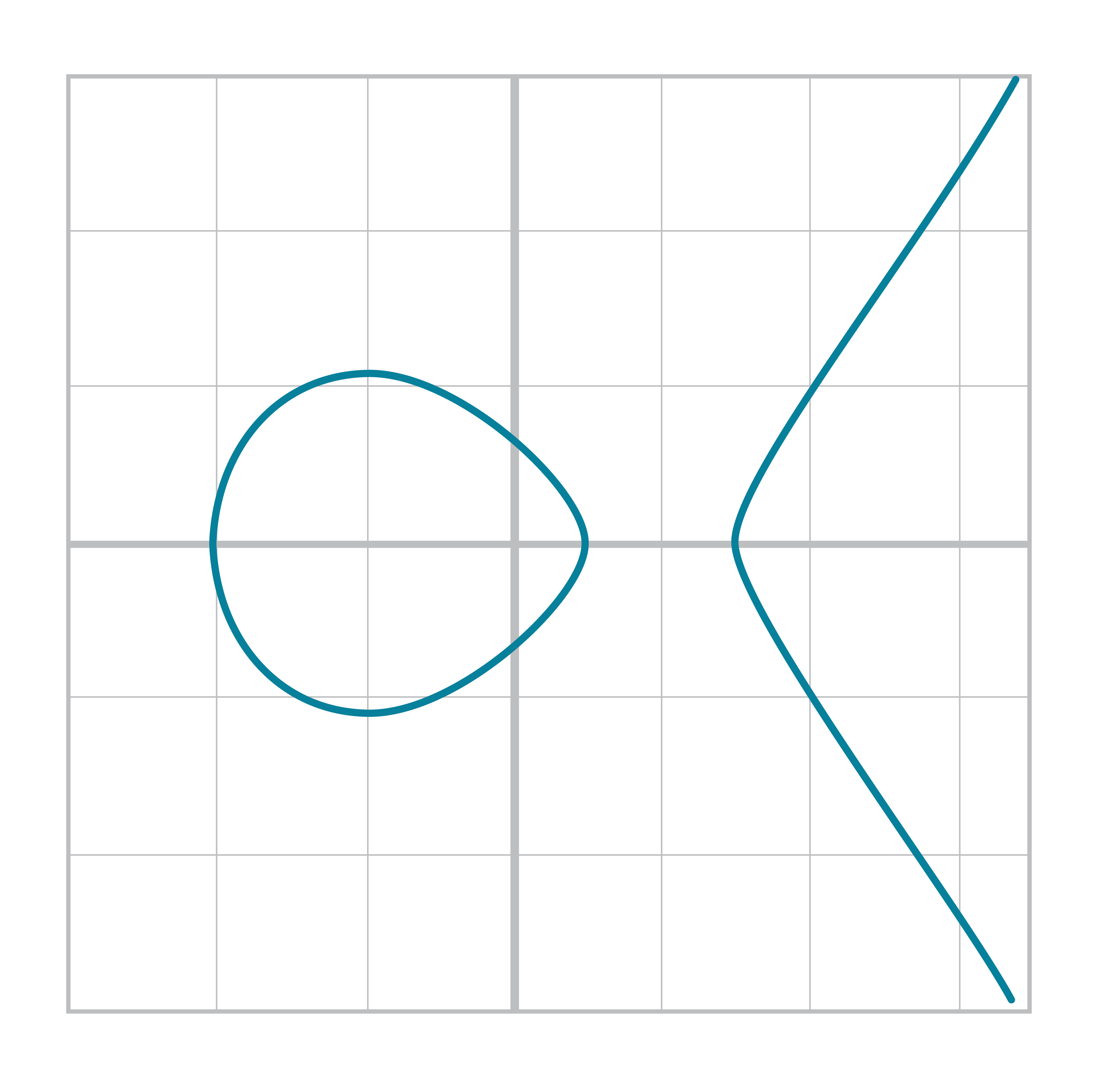

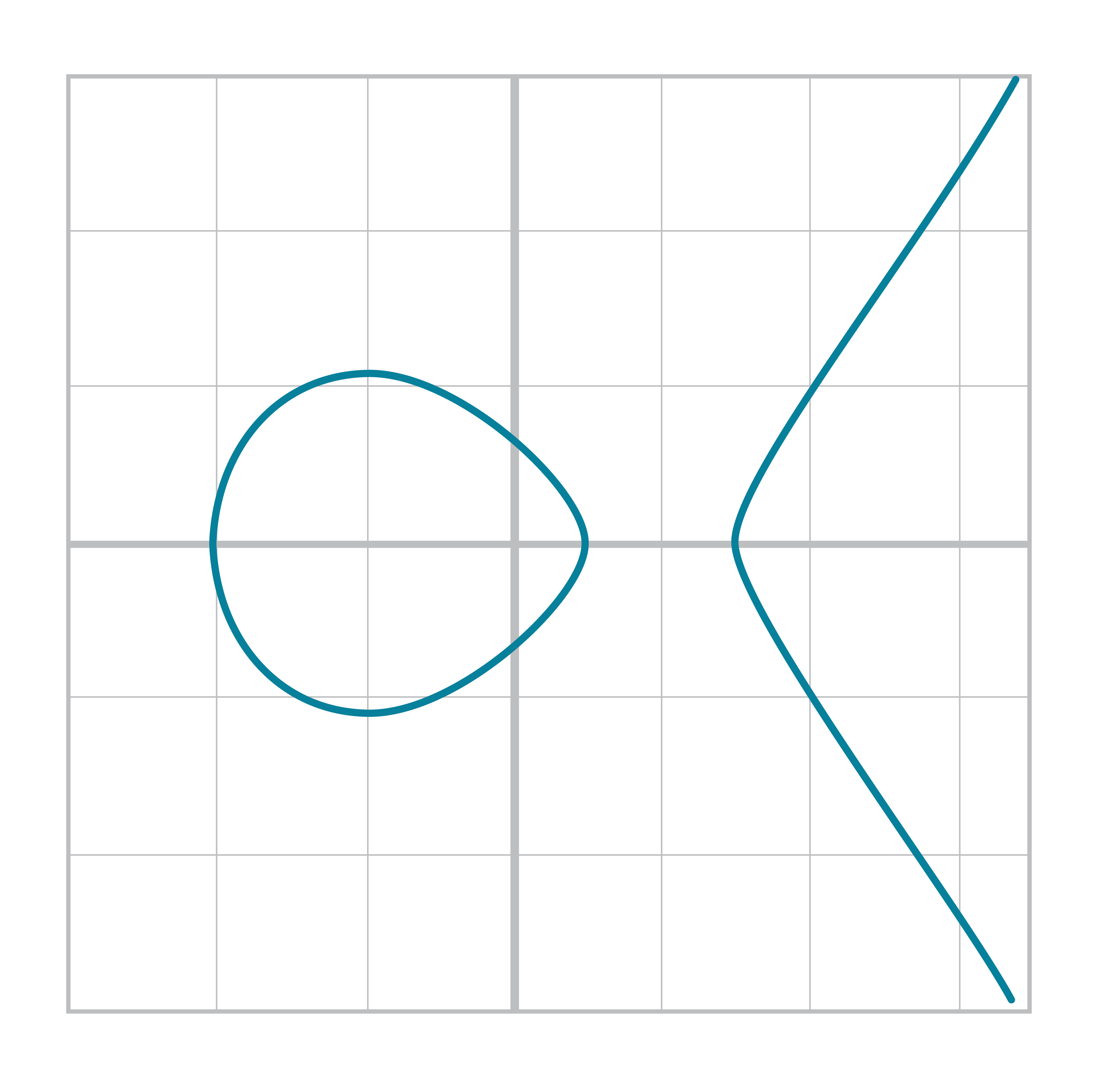

The Elliptic Curve is also less steep than the cubic curve. Again, this is because of the y2 term on the left side. At times, the curve may even be disjoint like Figure 2-5:

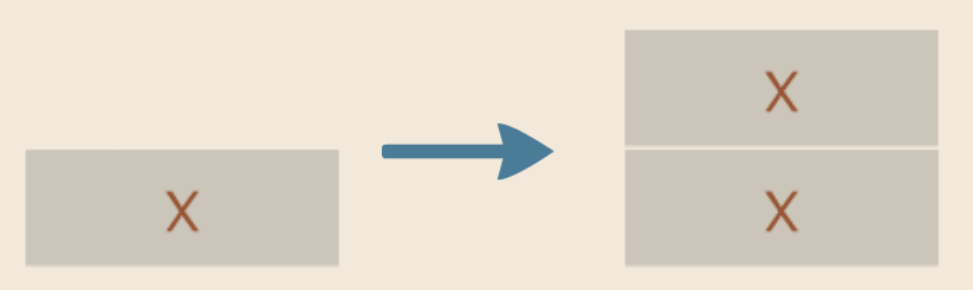

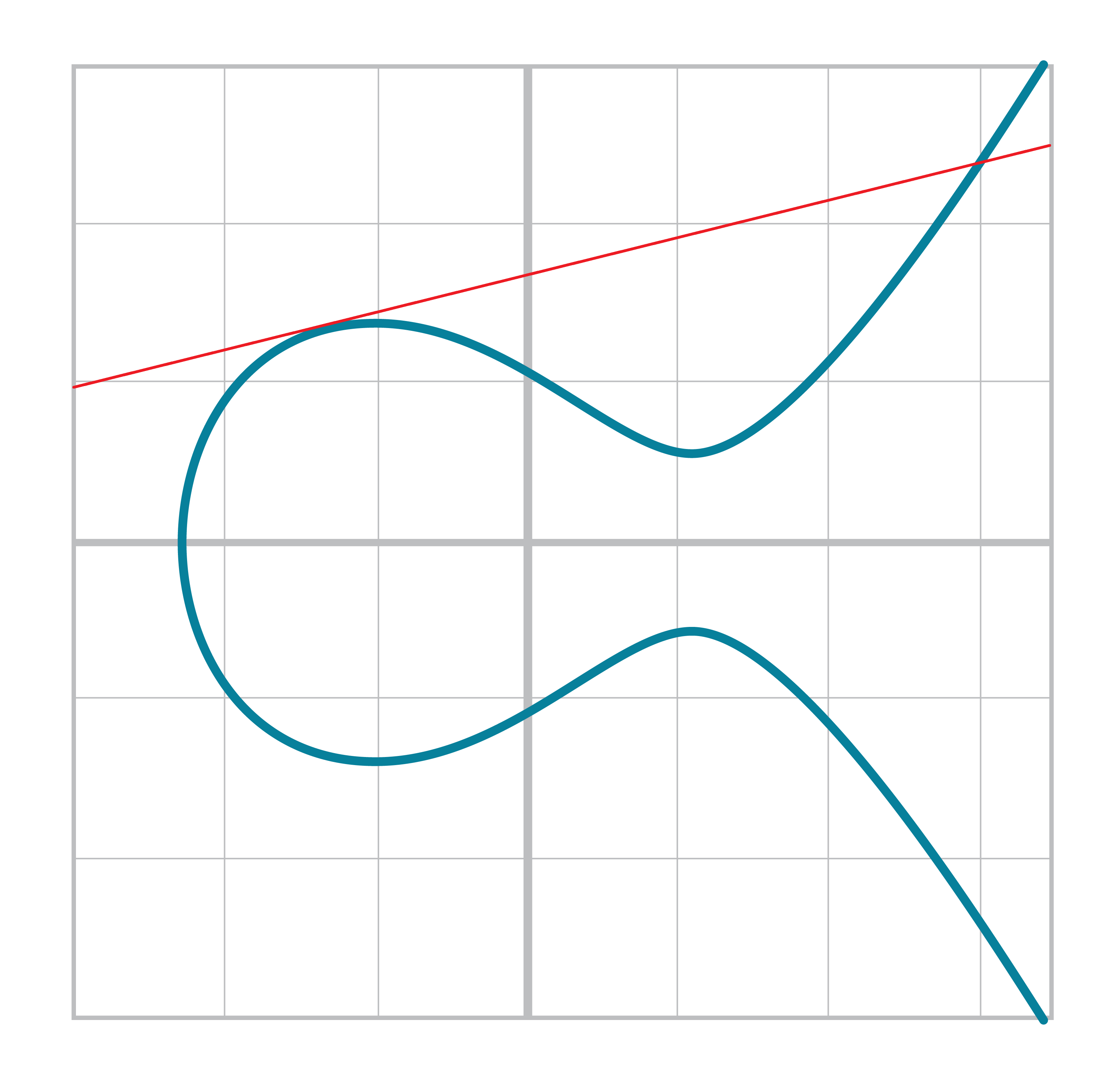

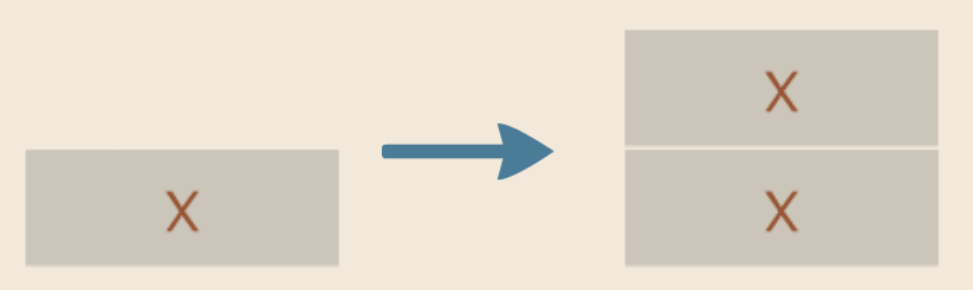

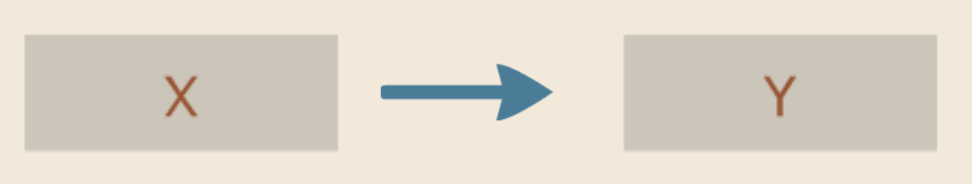

If it helps, an Elliptic Curve can be though of as taking a cubic equation graph (Figure 2-6), taking only the part above the x-axis, flattening it out (Figure 2-7) and then mirroring the top half on the bottom half of the x-axis (Figure 2-8).

Specifically, the Elliptic Curve used in Bitcoin is called secp256k1 and it uses this particular equation:

y2=x3+7

The canonical form is y2=x3+ax+b so the curve is defined by the constants a=0, b=7.

The curve looks like Figure 2-9:

For a variety of reasons which will be made clear later, we are not interested in the curve itself, but specific points on the curve.

For example, in the curve y2=x3+5x+7, we are interested in the coordinate (-1,1).

We are thus going to define the class Point to be a point on a specific curve.

The curve has the form y2=x3+ax+b, so we can define the curve with just the two numbers a and b.

classPoint:def__init__(self,x,y,a,b):self.a=aself.b=bself.x=xself.y=yifself.y**2!=self.x**3+a*x+b:raiseValueError('({}, {}) is not on the curve'.format(x,y))def__eq__(self,other):returnself.x==other.xandself.y==other.y\andself.a==other.aandself.b==other.b

We check here that the point is actually on the curve.

Points are equal if and only if they are on the same curve and have the same coordinates

We can now create Point objects, and we will get an error if the point is not on the curve:

>>>fromeccimportPoint>>>p1=Point(-1,-1,5,7)>>>p2=Point(-1,-2,5,7)Traceback(mostrecentcalllast):File"<stdin>",line1,in<module>File"ecc.py",line143,in__init__raiseValueError('({}, {}) is not on the curve'.format(self.x,self.y))ValueError:(-1,-2)isnotonthecurve

In other words, __init__ will raise an exception when the point is not on the curve.

Determine which of these points are on the curve y2=x3+5x+7:

(2,4), (-1,-1), (18,77), (5,7)

Write the __ne__ method for Point.

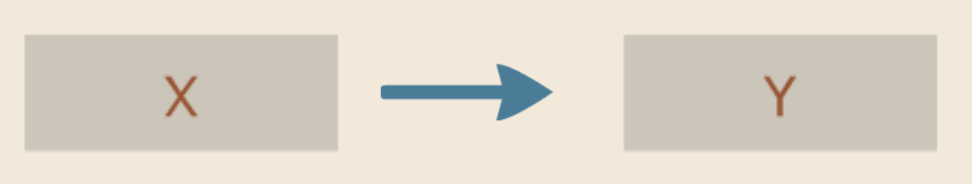

Elliptic Curves are useful because of something called Point Addition. Point Addition is where we can do an operation on two of the points on the curve and get a third point, also on the curve. This is called “addition” because the operation has a lot of the intuitions we associate with what we call “addition”. For example, Point Addition is commutative. That is, adding point A to point B is the same as adding point B to point A.

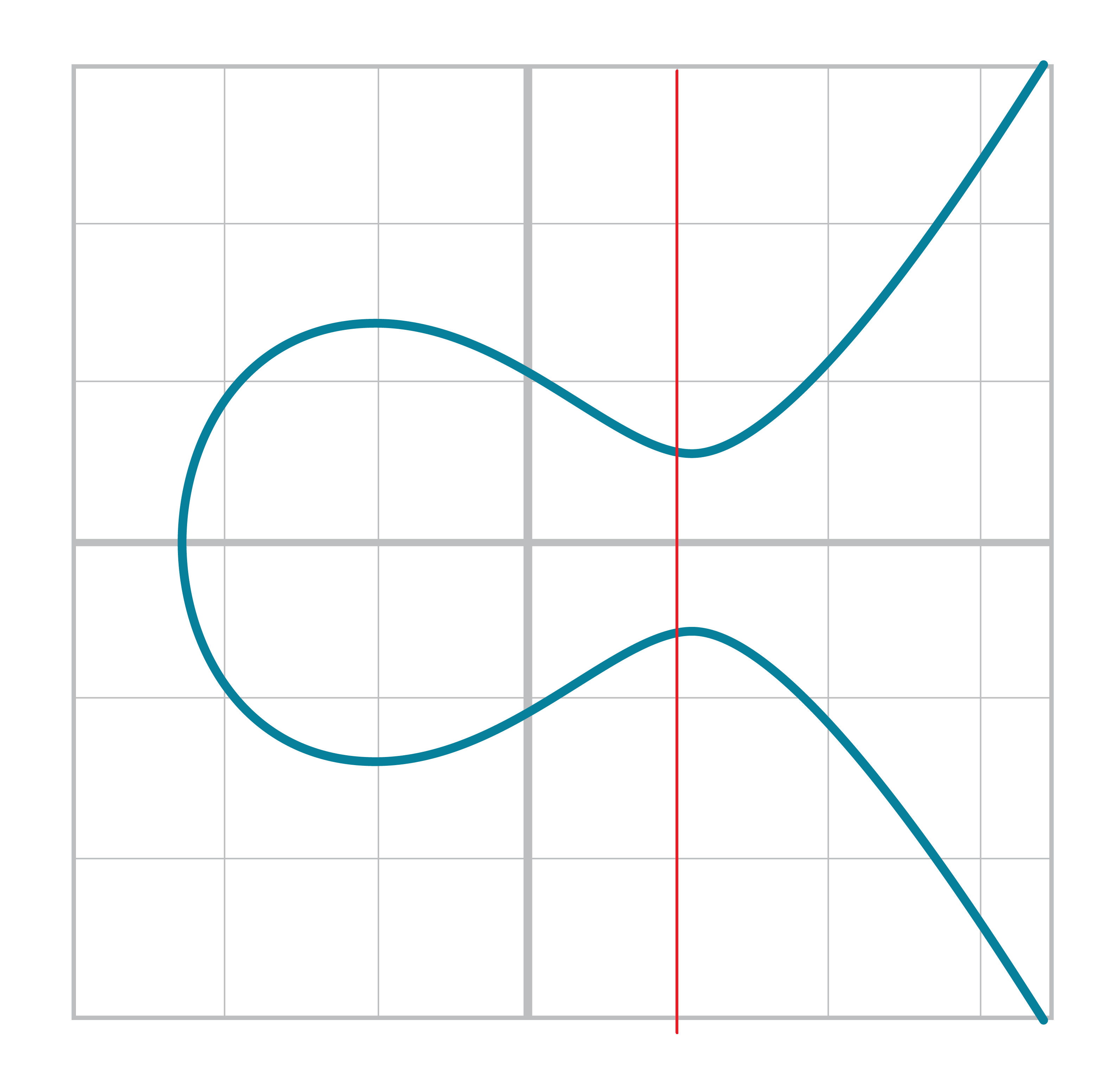

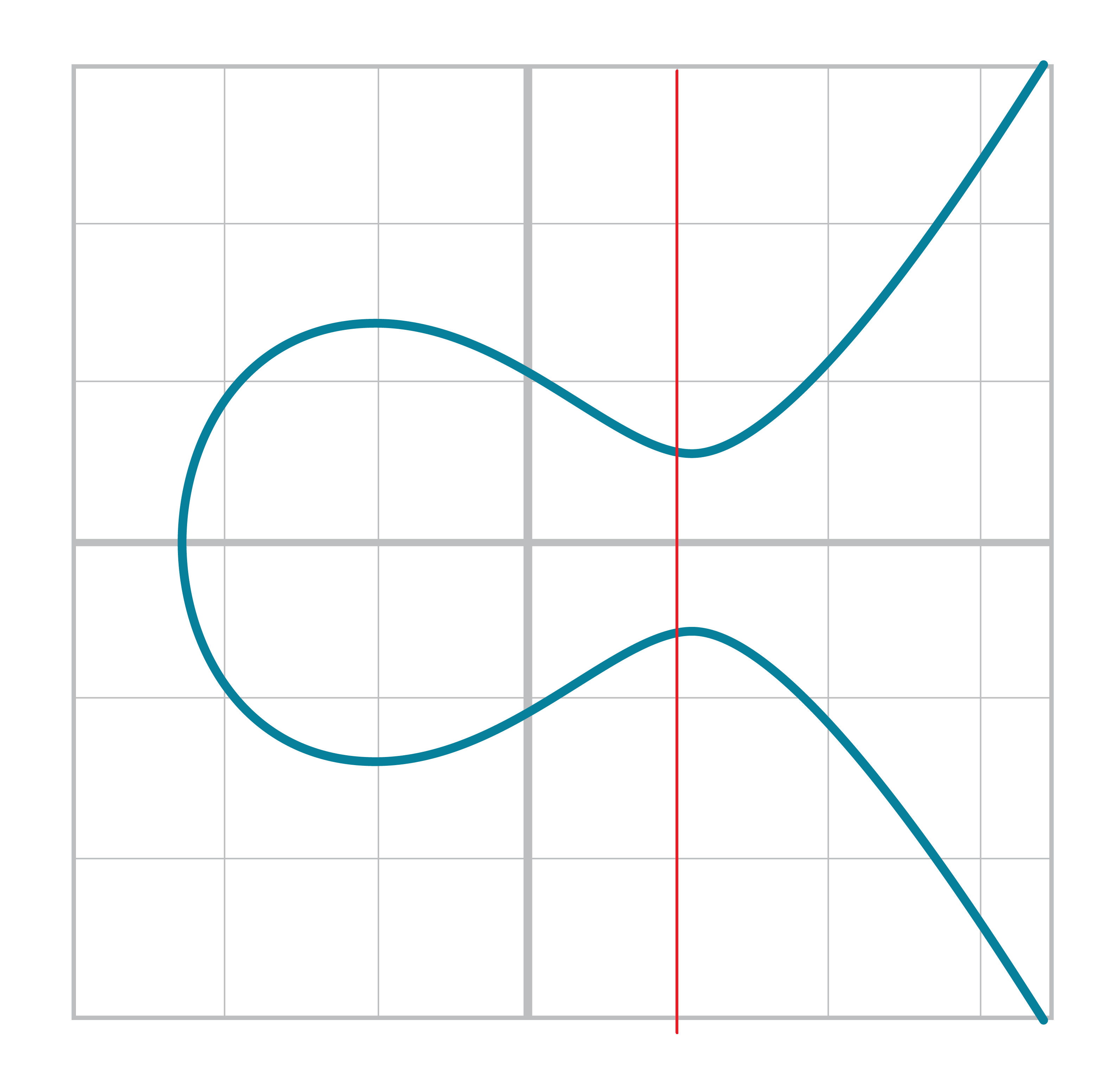

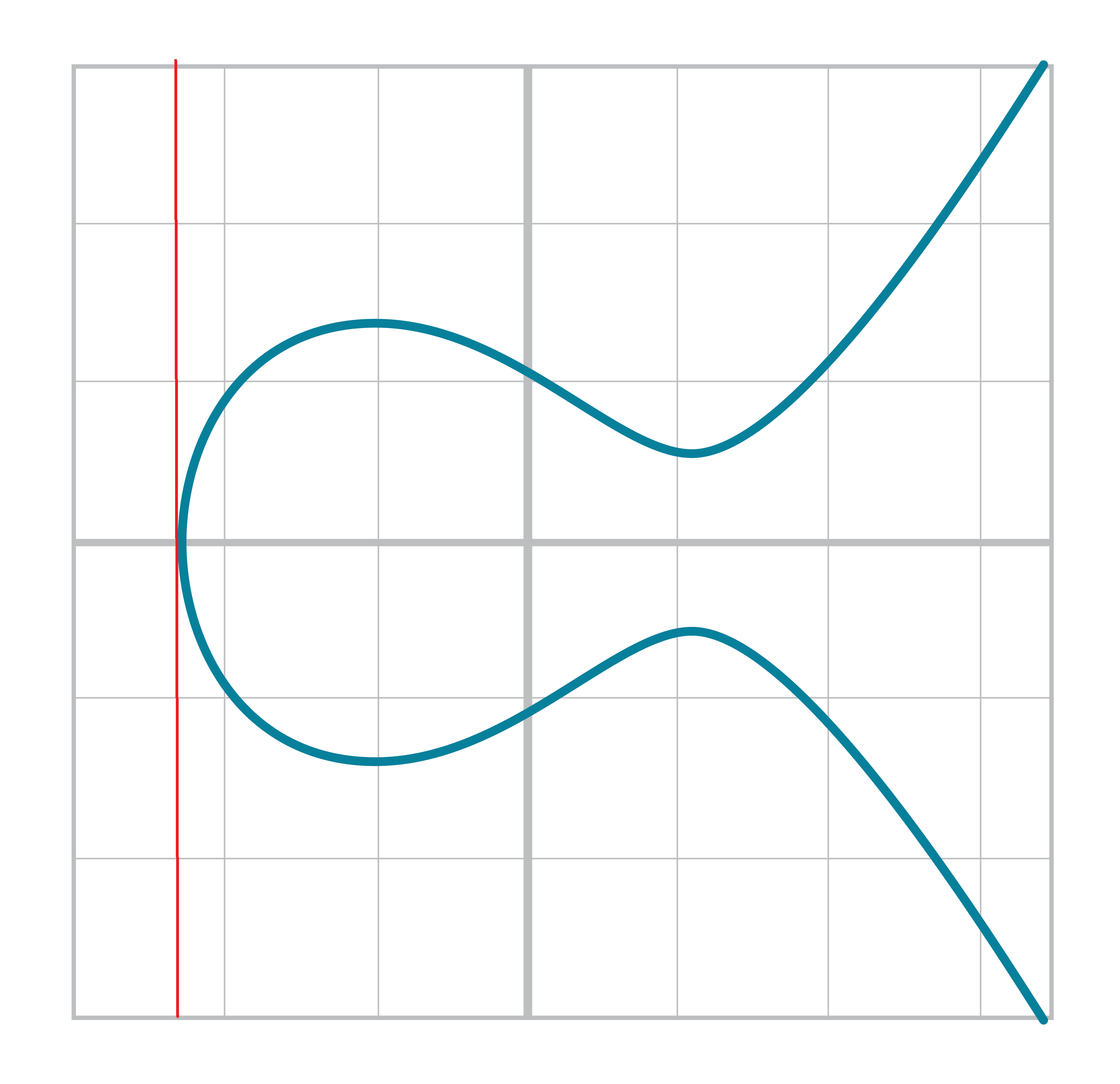

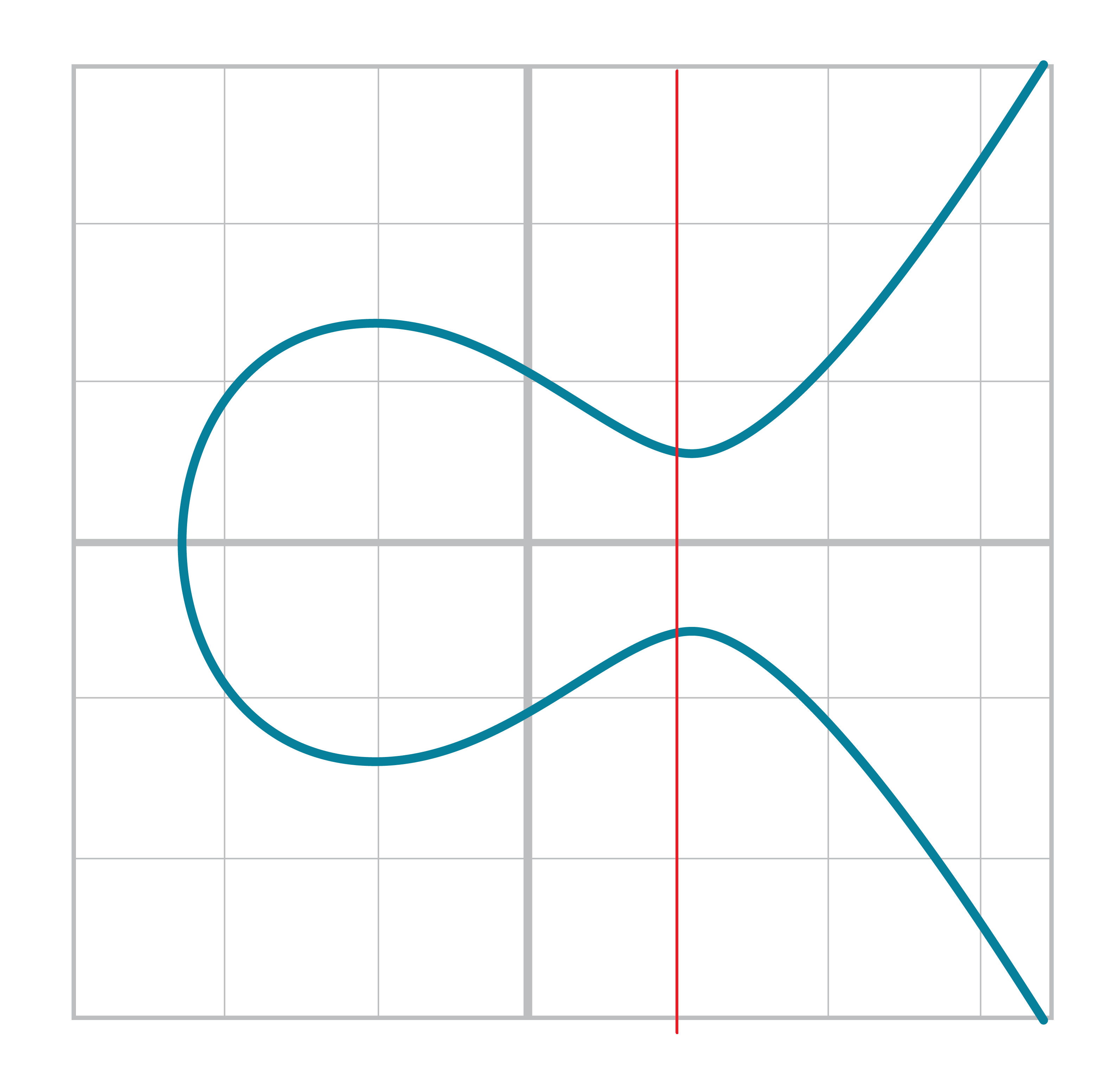

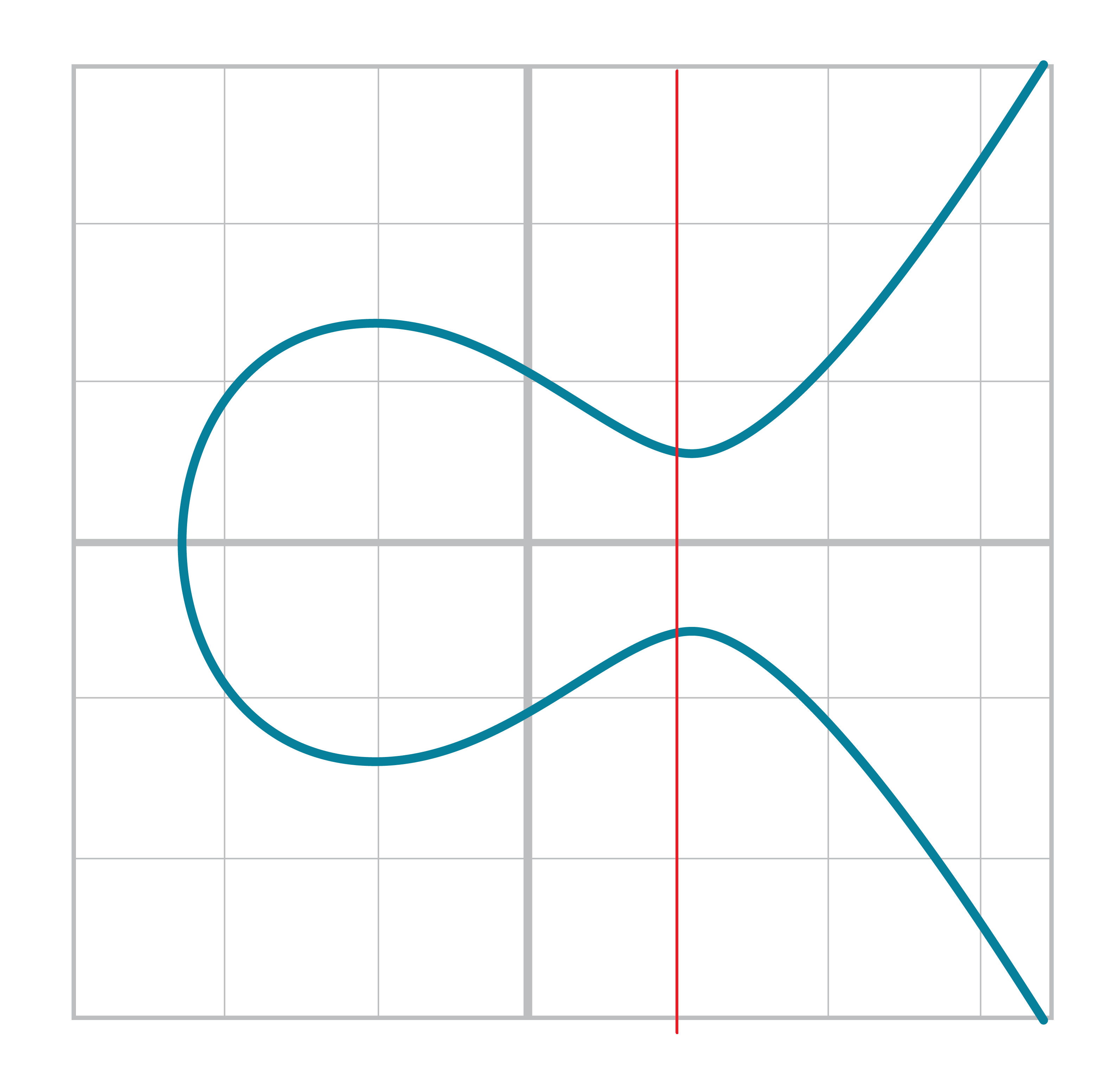

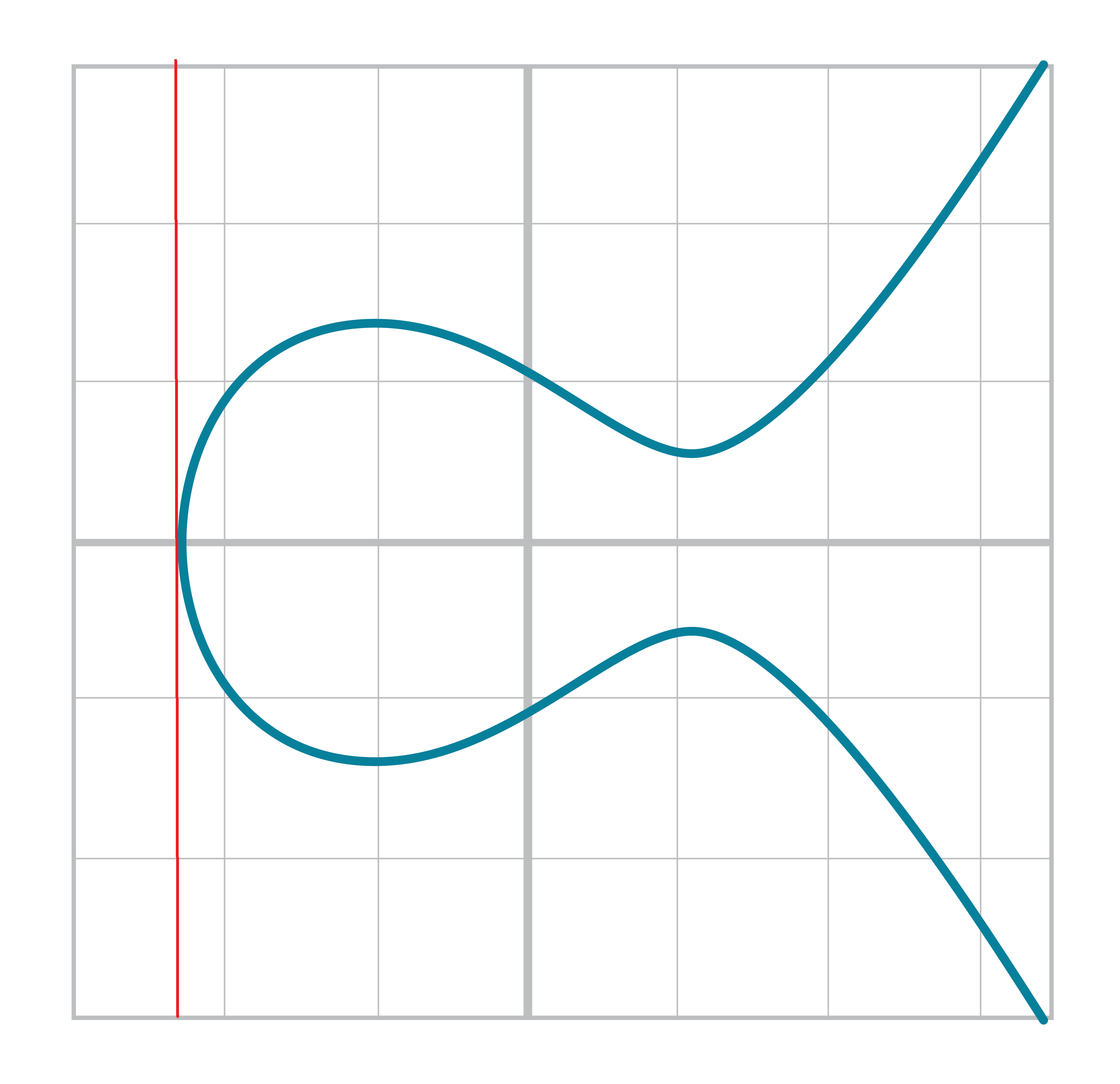

The way we define Point Addition is as follows. It turns out that for every Elliptic Curve, a line will intersect it at either 1 point (Figure 2-10) or 3 points (Figure 2-11), except for a couple of special cases.

The two exceptions are when a line is tangent to the curve (Figure 2-13) and when a line is exactly vertical (Figure 2-12).

We will come back to these two cases later.

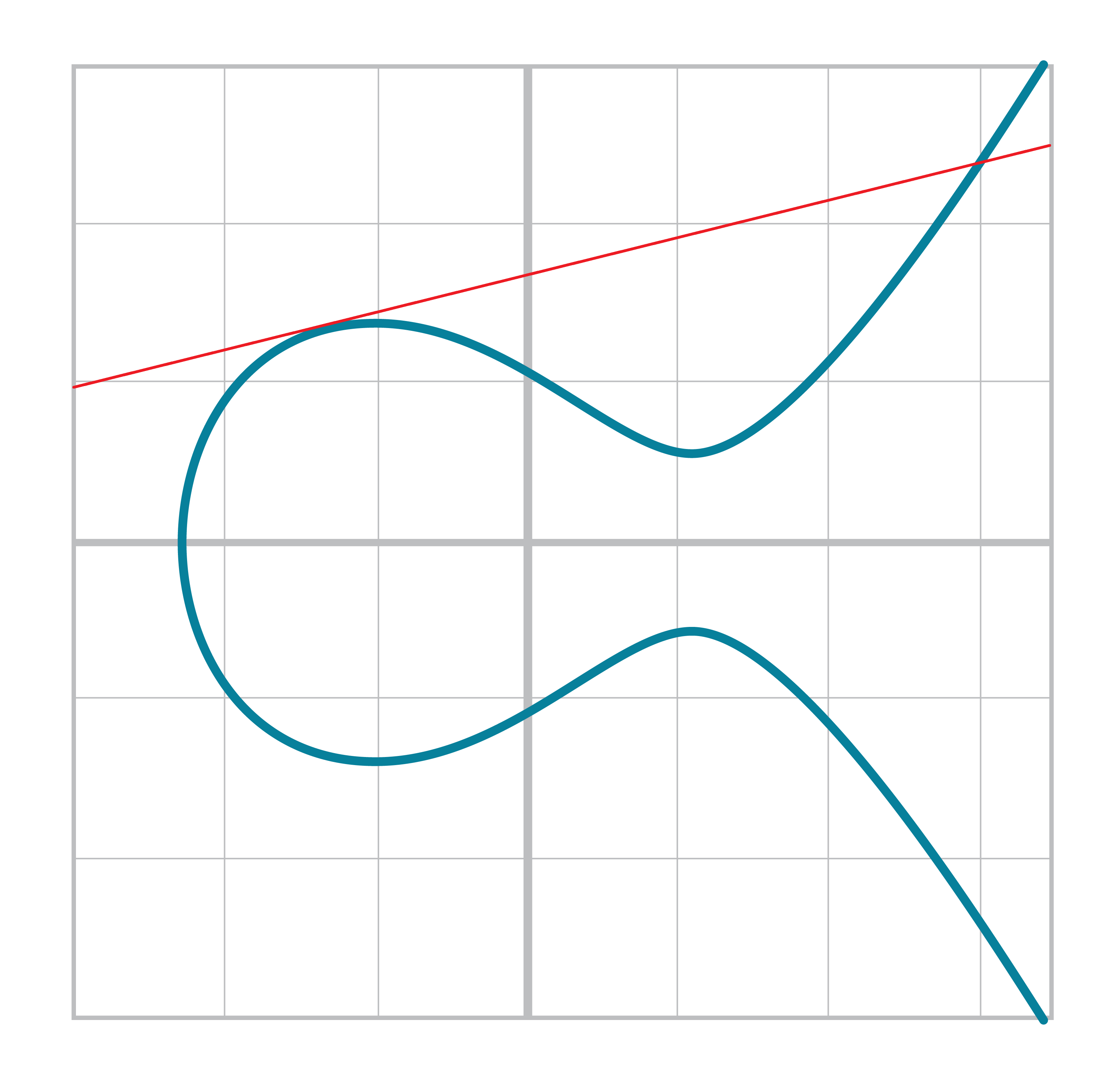

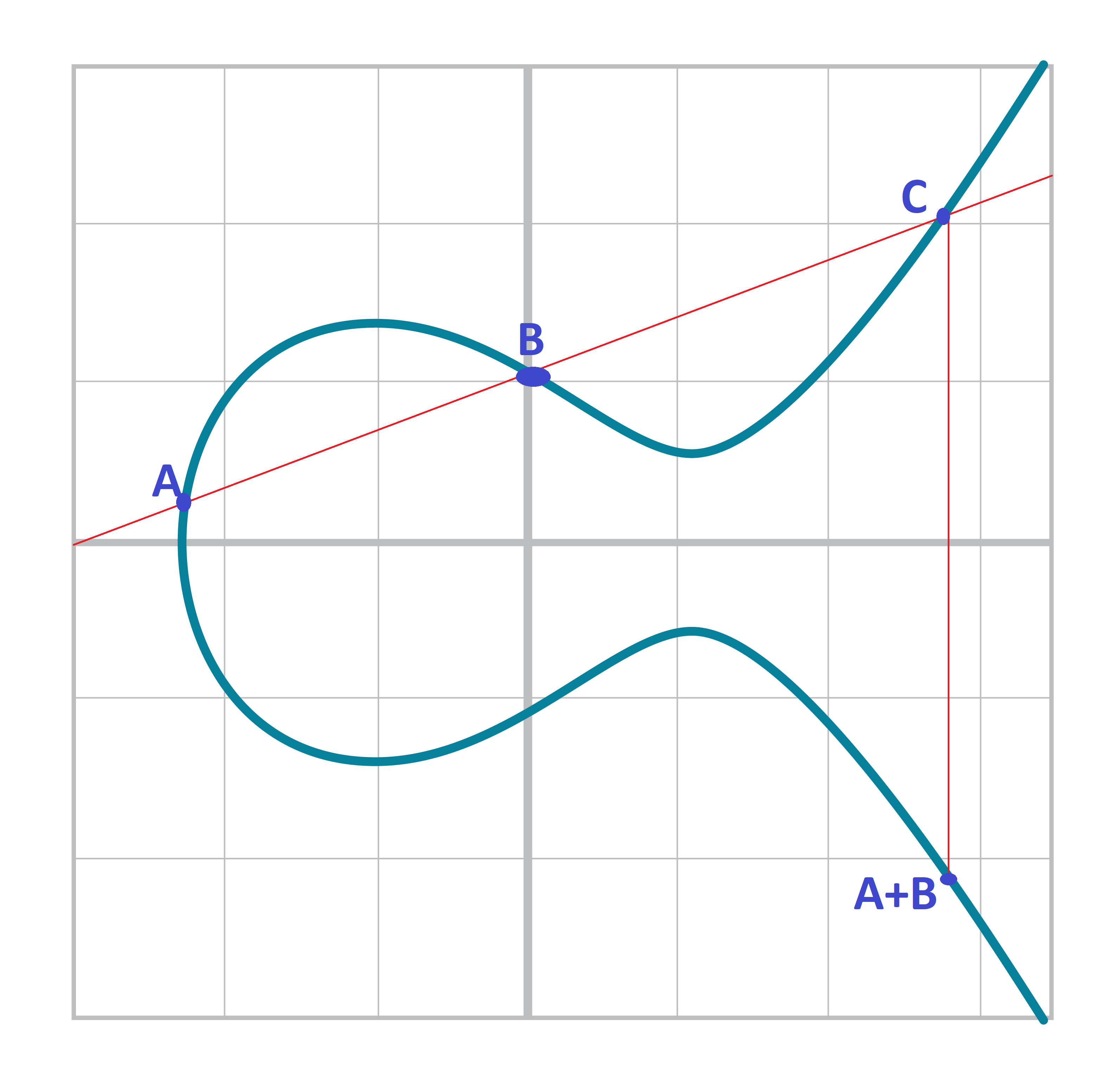

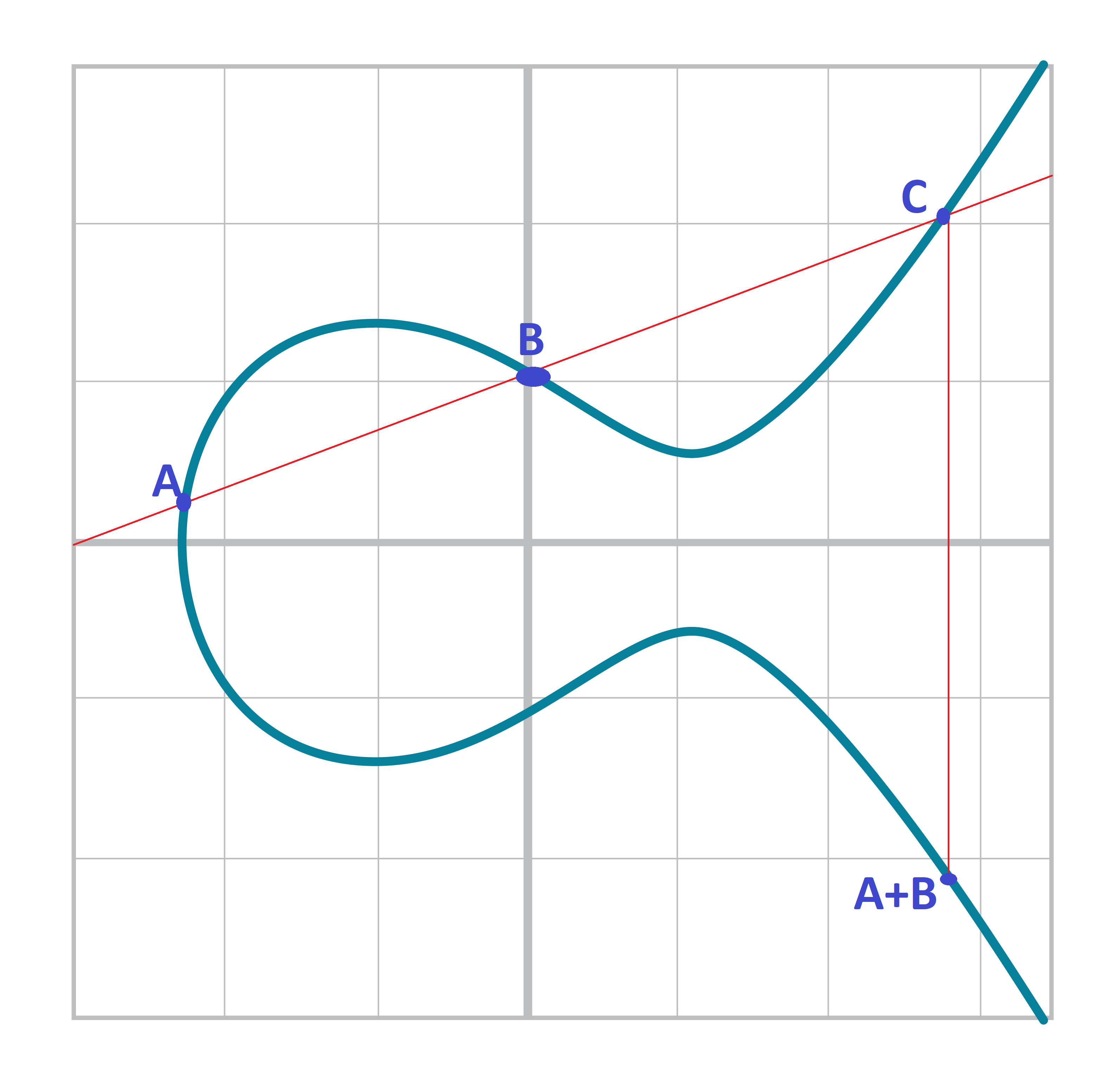

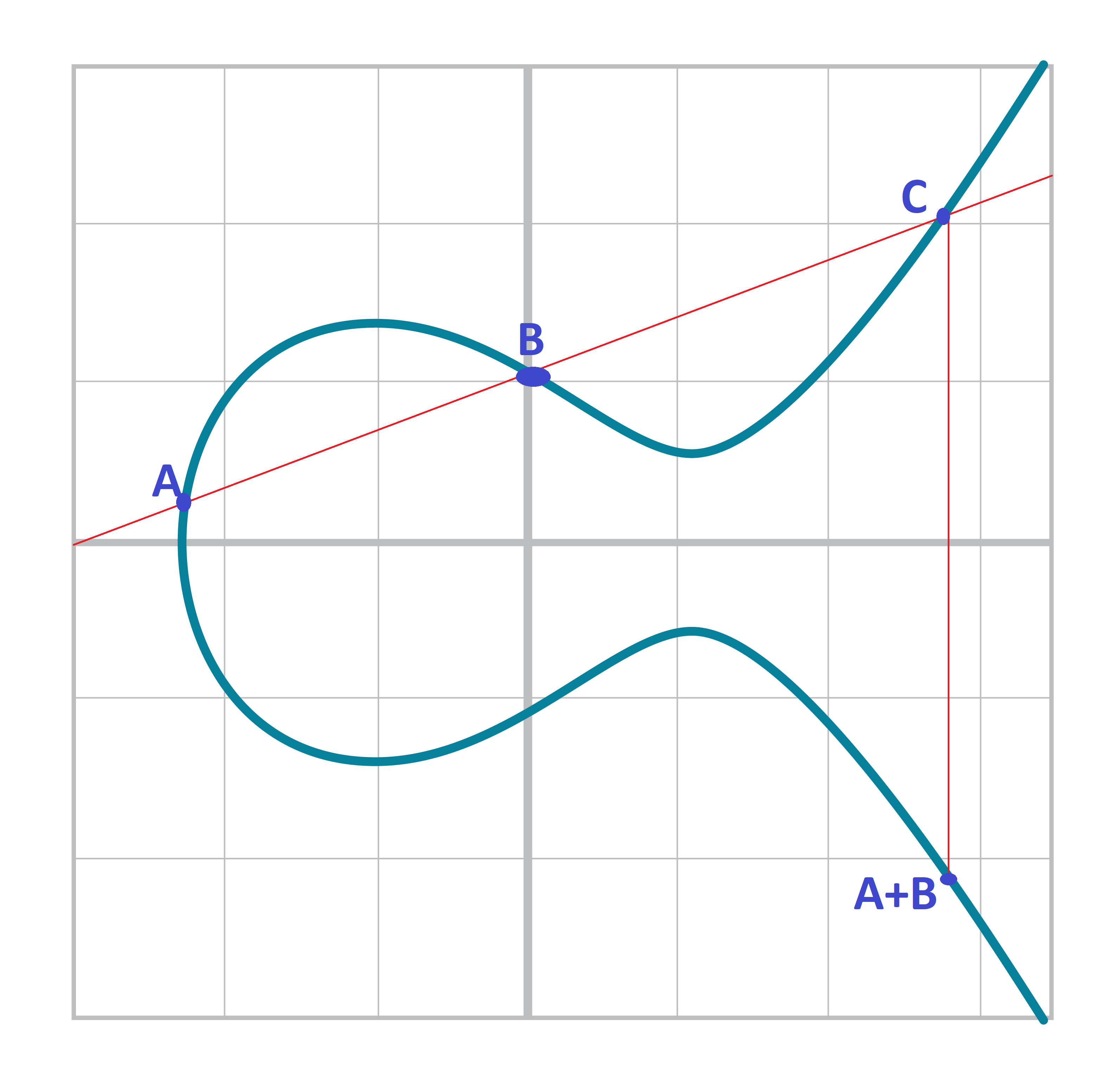

We can define point addition using the fact that lines intersect one or three times with the Elliptic Curve. Two points define a line, so since that line must intersect the curve at some point one more time. That third point reflected over the x-axis is the result of the point addition.

Like Finite Field Addition, we are going to define point addition. In our case, point addition is defined this way:

For any two points P1=(x1,y1) and P2=(x2,y2), we get P1+P2 by:

Find the point intersecting the Elliptic Curve a third time by drawing a line through P1 and P2

Reflect the resulting point over the x-axis

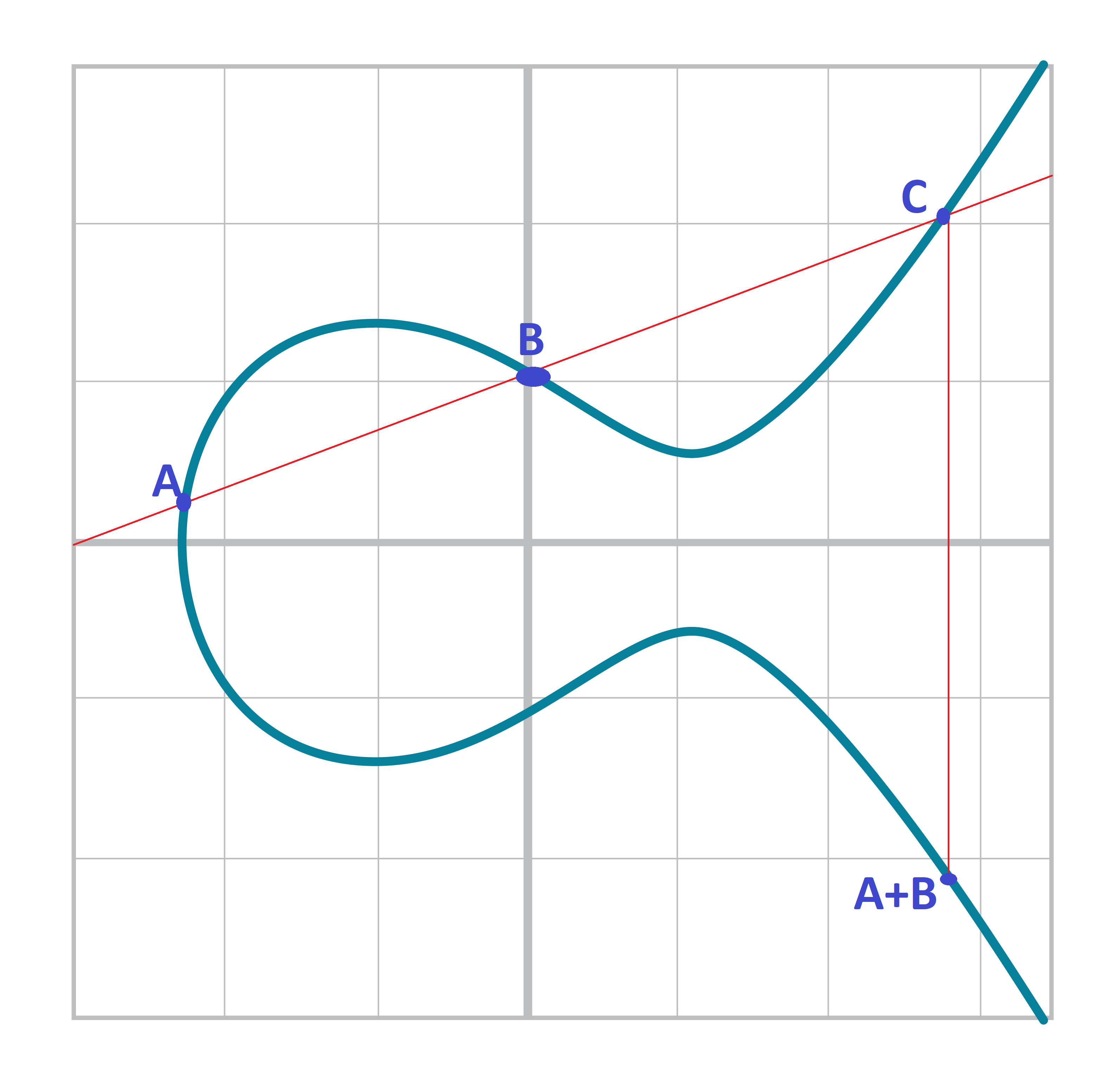

Visually, it looks like Figure 2-14:

We first draw a line through the two points we’re adding (A and B). The third intersection point is C. We then reflect that point over the x-axis, which puts us at the A+B point in Figure 2-14.

One of the properties that we are going to use is that point addition is not easily predictable. We can calculate point addition easily enough with a formula, but intuitively, the result of point addition can be almost anywhere given two points on the curve. Going back to Figure 2-14, A+B is to the right of both points, A+C would be somewhere between A and C on the x-axis, and B+C would be to the left of both points. In mathematics parlance, point addition is non-linear.

“Addition” in the name Point Addition satisfies certain properties that we think of as addition, such as:

Identity

Commutativity

Associativity

Invertibiltiy

Identity here means that there’s a zero. That is, there exists some point (I) which when added to a point (A) results in A. We’ll call this point the point at infinity (reasons for this will become clear in a bit). That is:

I + A = A

This is also related to invertibility. For some point A, there’s some other point -A which results in the Identity point. That is:

A + (-A) = I

Visually, these are points opposite the x-axis on the curve (see Figure 2-15).

This is why we call this point the point at infinity. We have one extra point in the Elliptic Curve which makes the vertical line intersect the curve a third time.

Commutativity means that A+B=B+A. This is obvious since the line going through A and B will intersect the curve a third time in the same place no matter the order.

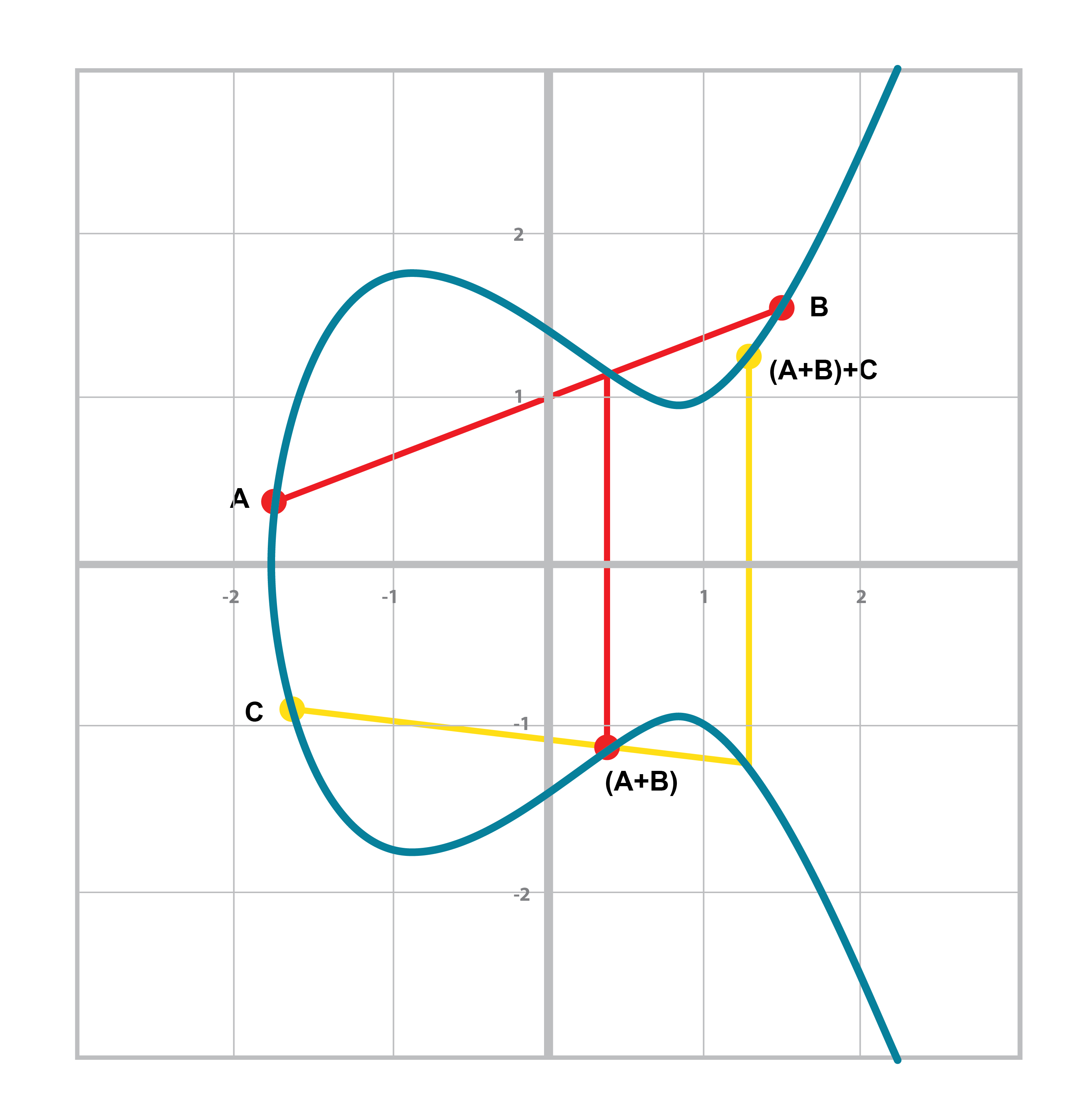

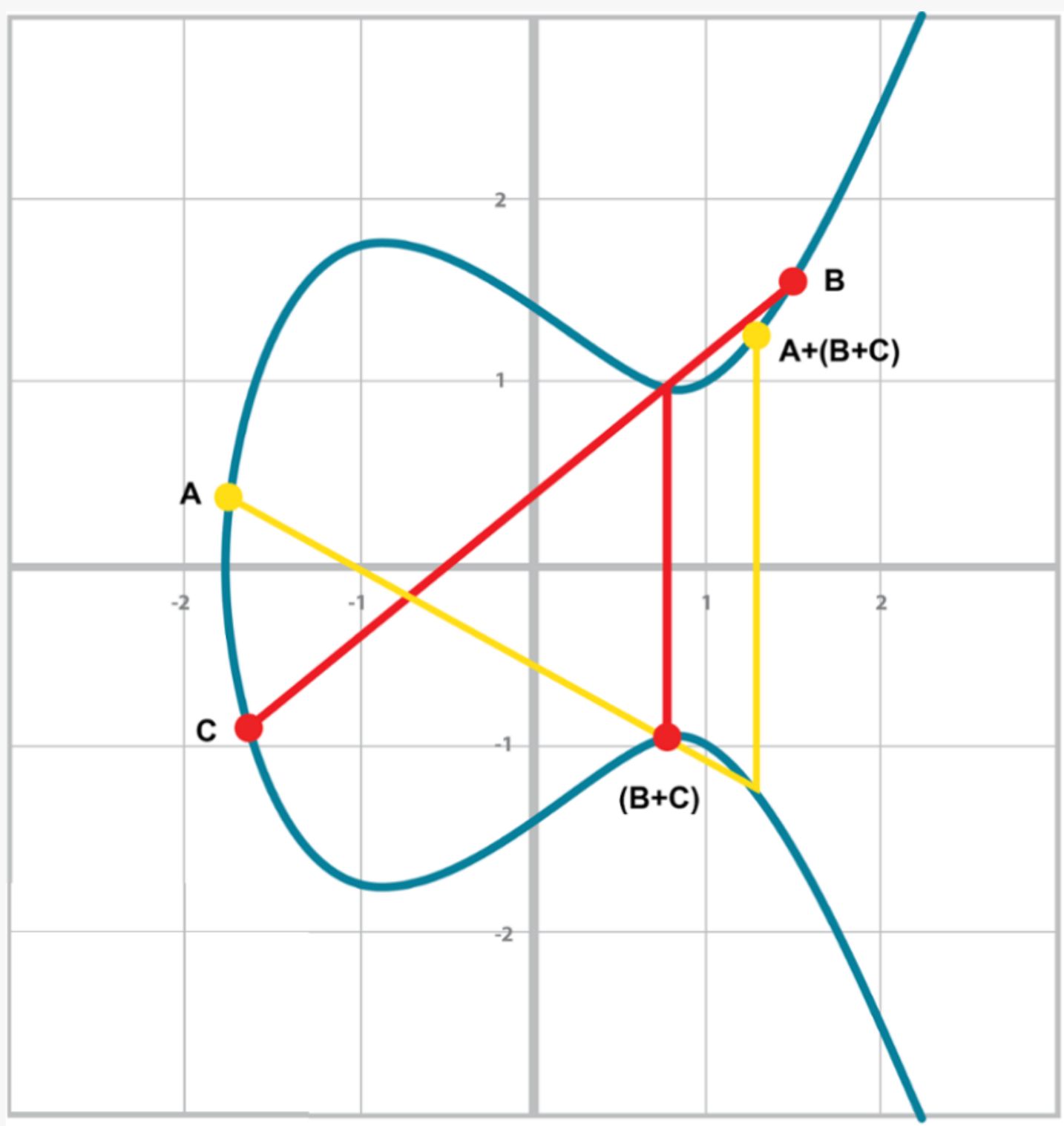

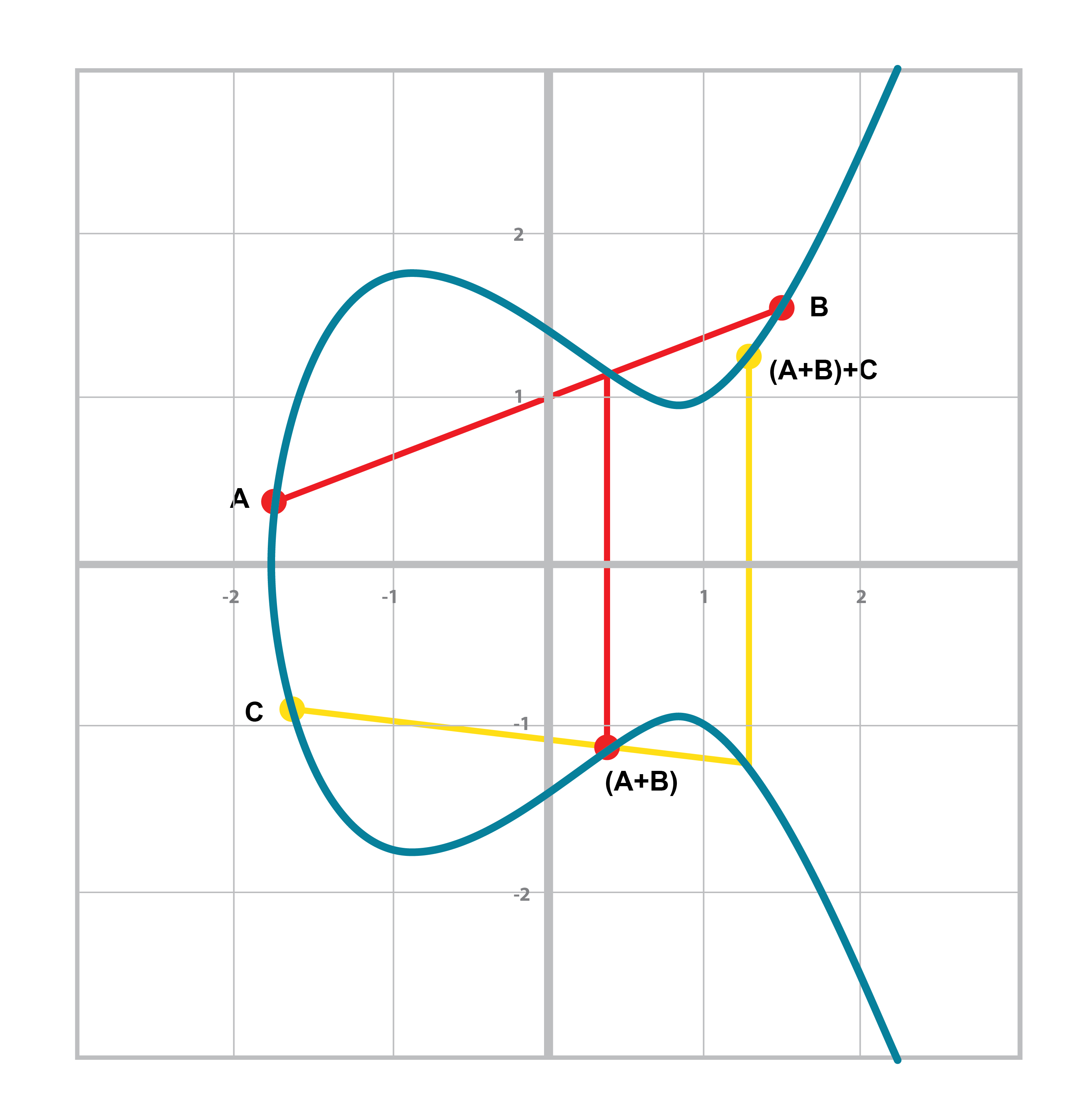

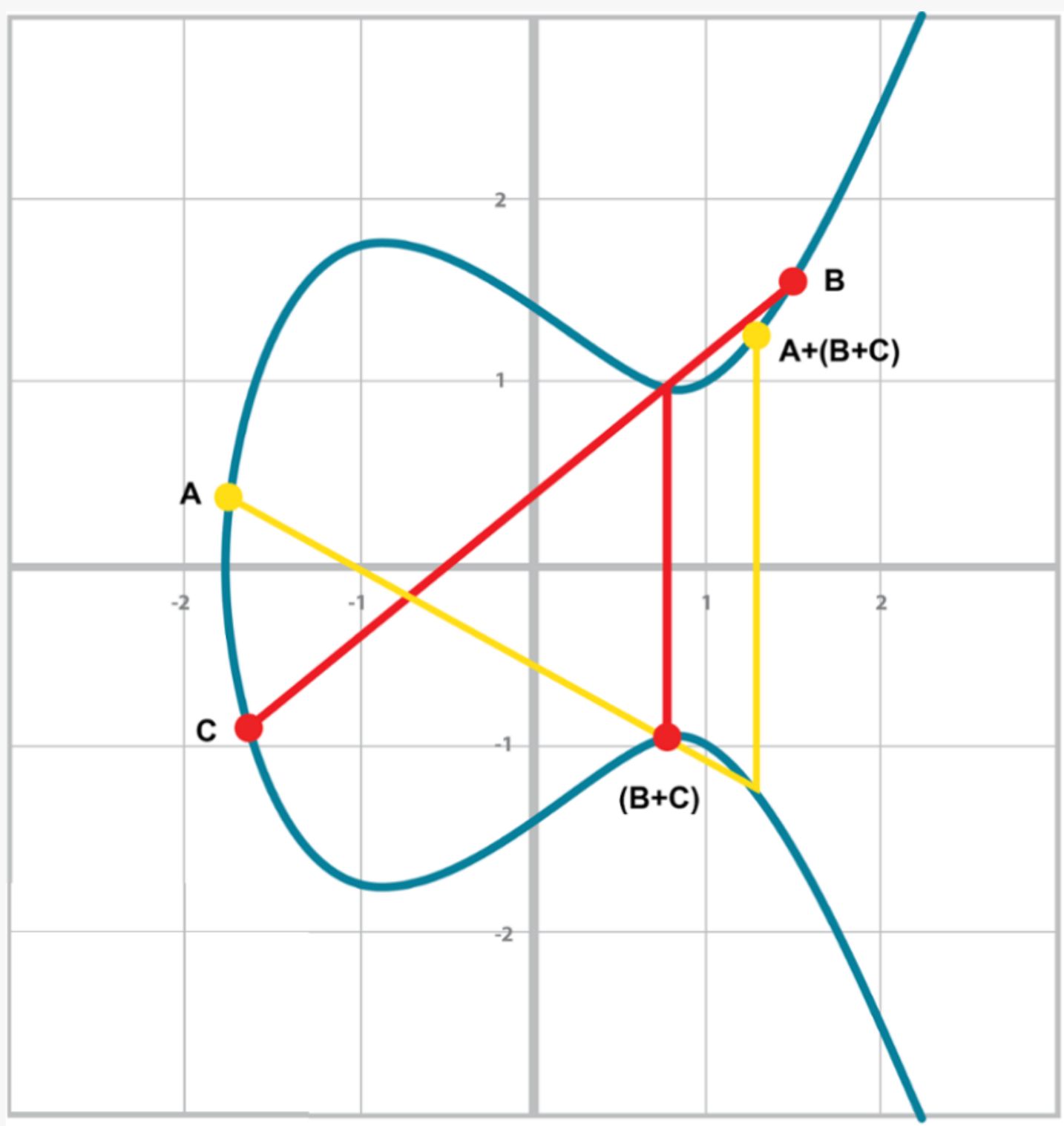

Associativity means that (A+B) + C = A + (B+C). This isn’t obvious and is the reason for flipping over the x-axis.

You can see that in both Figure 2-16 and Figure 2-17, the final point is the same. While this doesn’t prove the associativity of point addition, the visual should at least give you the intuition that this is true.

To code point addition, we’re going to split it up into 3 steps:

Where the points are in a vertical line or using the Identity.

Where the points are not in a vertical line, but are different.

Where the two points are the same.

We first handle the identity, or the point at infinity.

Since we can’t easily use infinity in Python, we’ll use the None value instead.

What we want is this to work:

>>>fromeccimportPoint>>>p1=Point(-1,-1,5,7)>>>p2=Point(-1,1,5,7)>>>inf=Point(None,None,5,7)>>>(p1+inf)Point(-1,-1)_5_7>>>(inf+p2)Point(-1,1)_5_7>>>(p1+p2)Point(infinity)

In order to make this work, we have to do two things:

First, we have to adjust the __init__ method slightly so it doesn’t check that the curve equation is satisfied when we have the point at infinity.

Second, we have to overload the addition operator or __add__ as we did with the FieldElement class.

classPoint:def__init__(self,x,y,a,b):self.a=aself.b=bself.x=xself.y=yifself.xisNoneandself.yisNone:returnifself.y**2!=self.x**3+a*x+b:raiseValueError('({}, {}) is not on the curve'.format(x,y))def__add__(self,other):ifself.a!=other.aorself.b!=other.b:raiseTypeError('Points {}, {} are not on the same curve'.format(self,other))ifself.xisNone:returnotherifother.xisNone:returnself

x-coordinate and y-coordinate being None is how we signify the point at infinity.

Note that the next if statement will fail if we don’t return here.

We overload the + operator here

self.x being None means that self is the point at infinity, or the additive identity.

Thus, we return other

self.x being None means that other is the point at infinity, or the additive identity.

Thus, we return self

Handle the case where the two points are additive inverses. That is, they have the same x, but a different y, causing a vertical line. This should return the point at infinity.

Now that we’ve covered the vertical line, we’re now proceeding to when the points are different.

When we have points where the x’s differ, we can add using a fairly simple formula.

To help with intuition, we’ll first find the slope created by the two points.

You can figure this out using a formula from pre-Algebra:

P1=(x1,y1), P2=(x2,y2), P3=(x3,y3)

P1+P2=P3

s=(y2-y1)/(x2-x1)

This is the slope and we can use the slope to calculate x3. Once we know x3, we can calculate y3. P3 can be derived using this formula:

x3=s2-x1-x2

y3=s(x1-x3)-y1

Remember that y3 is the reflection over the x-axis.

For the curve y2=x3+5x+7, what is (2,5) + (-1,-1)?

We now code this into our library.

That means we have to adjust the __add__ method to handle the case where x1≠x2.

We have the formulas:

s=(y2-y1)/(x2-x1)

x3=s2-x1-x2

y3=s(x1-x3)-y1

At the end of the method, we return an instance of the class Point using self.__class__ to make subclassing easier..

Write the __add__ method where x1≠x2

When the x coordinates are the same and the y coordinate is different, we have the situation where the points are opposite each other over the x-axis.

We know that this means:

P1=-P2 or P1+P2=I

We’ve already handled this in Exercise 3.

What happens when P1=P2? Visually, we have to calculate the line that’s tangent to the curve at P1 and find the point at which the line intersects the curve. The situation looks like this as we saw before (see Figure 2-18):

Once again, we’ll find the slope of the tangent point.

P1=(x1,y1), P3=(x3,y3)

P1+P1=P3

s=(3x12+a)/(2y1)

The rest of the formula goes through as before, except x1=x2, so we can combine them:

x3=s2-2x1

y3=s(x1-x3)-y1

We can derive the slope of the tangent line using some slightly more advanced math: calculus. We know that the slope at a given point is

dy/dx

To get this, we need to take the derivative of both sides of the Elliptic Curve equation:

y2=x3+ax+b

Taking the derivative of both sides, we get:

2y dy=(3x2+a) dx

Solving for dy/dx, we get:

dy/dx=(3x2+a)/(2y)

That’s how we arrive at the slope formula. The rest of the results from the point addition formula derivation hold.

For the curve y2=x3+5x+7, what is (2,5) + (-1,-1)?

We adjust the __add__ method to account for this particular case.

We have the formulas, we now implement them.

s=(3x12+a)/(2y1)

x3=s2-2x1

y3=s(x1-x3)-y1

Write the __add__ method when P1=P2.

There is one more exception and this involves the case where the tangent line is vertical (Figure 2-19):

This can only happen if P1=P2 and the y-coordinate is 0, in which case the slope calculation will end up with a 0 in the denominator.

We handle this with a special case:

classPoint:...def__add__(self,other):...ifself==otherandself.y==0*self.x:returnself.__class__(None,None,self.a,self.b)

The previous two chapters covered some fundamental math. We learned how Finite Fields work and we also learned what an Elliptic Curve is. In this chapter, we’re going to combine the two concepts to learn Elliptic Curve Cryptography. Specifically, we’re going to build the primitives needed to sign and verify messages, which is at the heart of what Bitcoin does.

We discussed in Chapter 2 what an Elliptic Curve looks like visually because we were plotting the curve over real numbers. Specifically, it’s not just integers or even rational numbers, but all real numbers. Pi, sqrt(2), e+7th root of 19, etc are all part of real numbers.

This worked because real numbers are also a field. Note unlike a finite field, there are an infinite number of real numbers, but otherwise the same properties hold:

If a and b are in the set, a+b and a⋅b are in the set.

The additive identity, 0 exists and has the property a + 0 = a.

The multiplicative identity, 1 exists and has the property a ⋅ 1 = a.

If a is in the set, -a is in the set, which is defined as the value that makes a + (-a) = 0.

If a is in the set and is not 0, a-1 is in the set, which is defined as the value that makes a ⋅ a-1 = 1.

Clearly, all of these are true as normal addition and multiplication apply for the first part, additive and multiplicative identities 0 and 1 exist, -x is the additive inverse and 1/x is the multiplicative inverse.

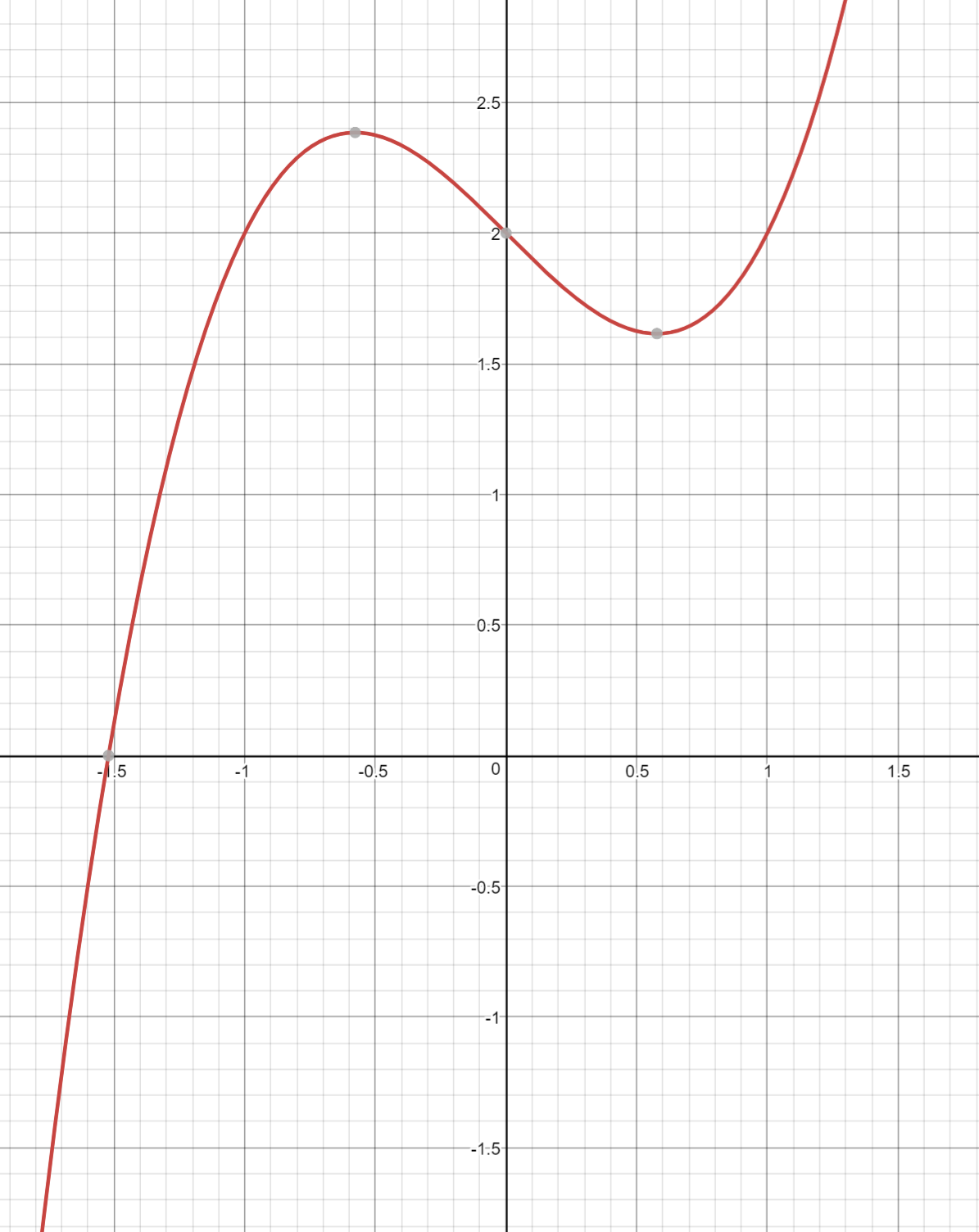

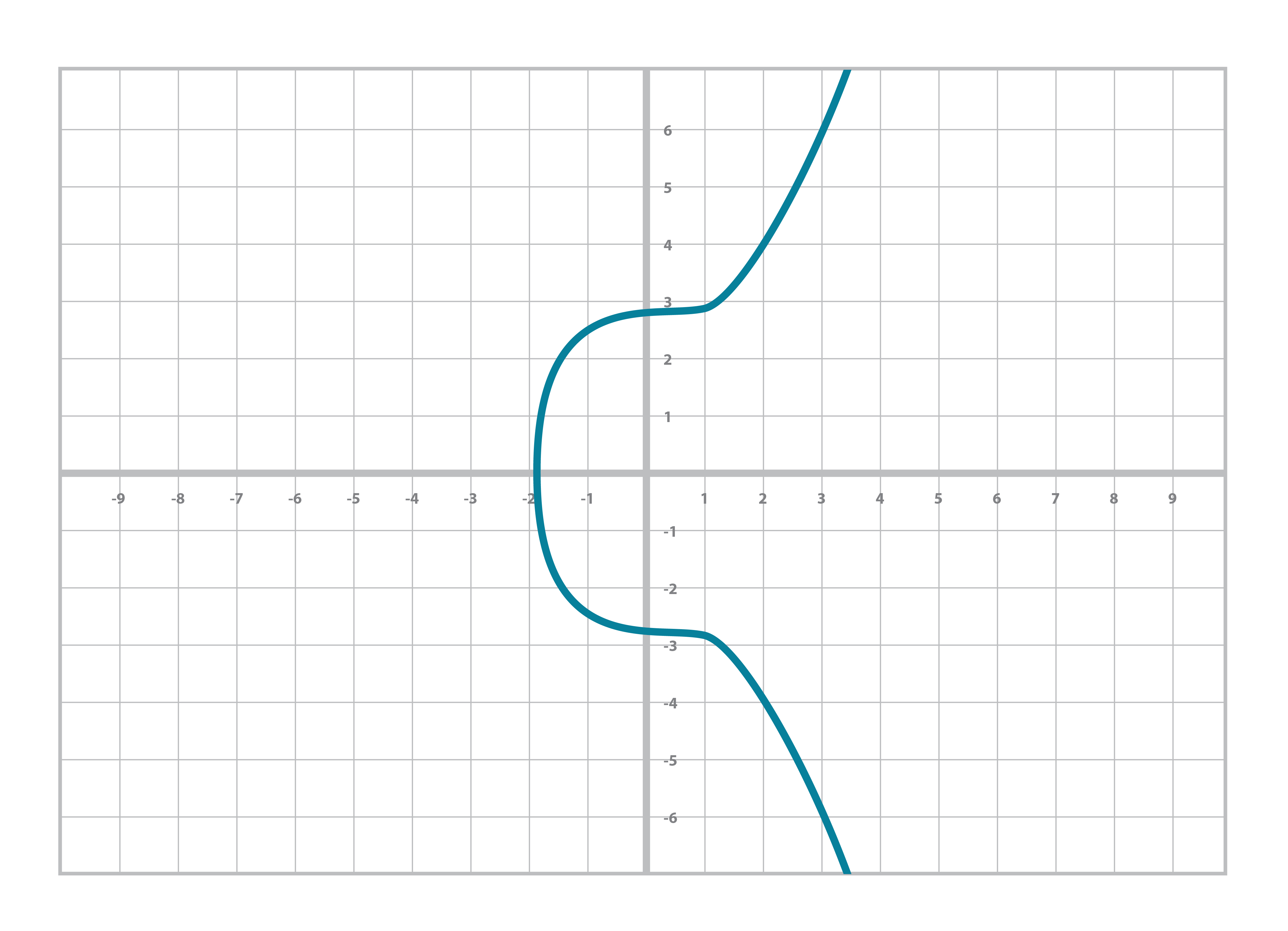

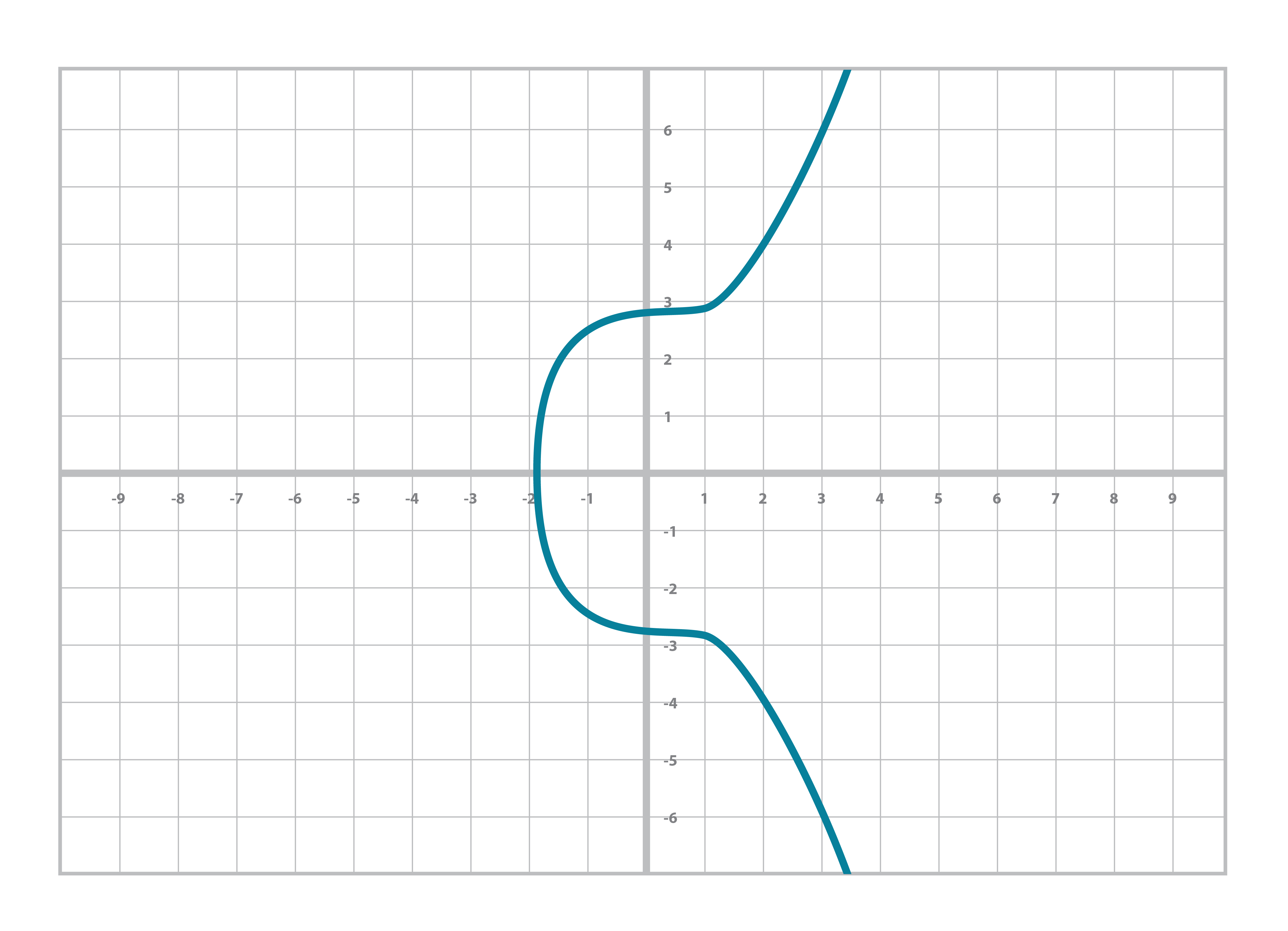

Real numbers are easy to plot and we can see the a graph over reals visually. For example, y2=x3+7 can be plotted like Figure 3-1:

It turns out we can use the point addition equations over any field, including the Finite Fields we learned in Chapter 1. The only difference is that we have to use the addition/subtraction/multiplication/division as defined in Chapter 1, not the “normal” versions that the real numbers use.

So what does an Elliptic Curve over a Finite Field look like? Let’s look at the equation y2=x3+7 over F103. We can verify that the point (17,64) is on the curve by calculating both sides of the equation:

y2=642%103=79

x3+7=(173+7)%103=79

We’ve verified that the point is on the curve using Finite Field math.

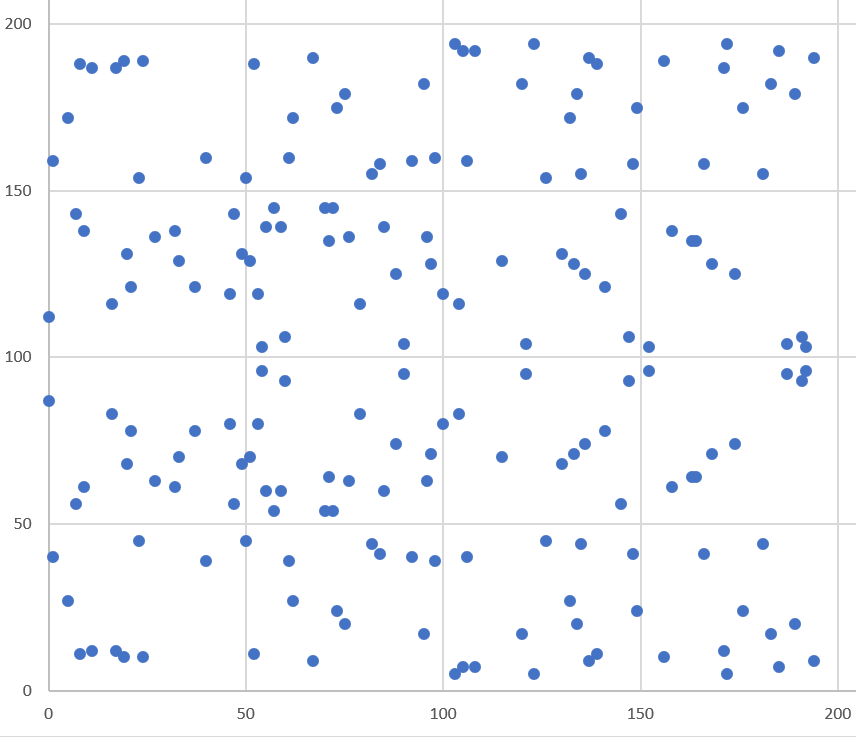

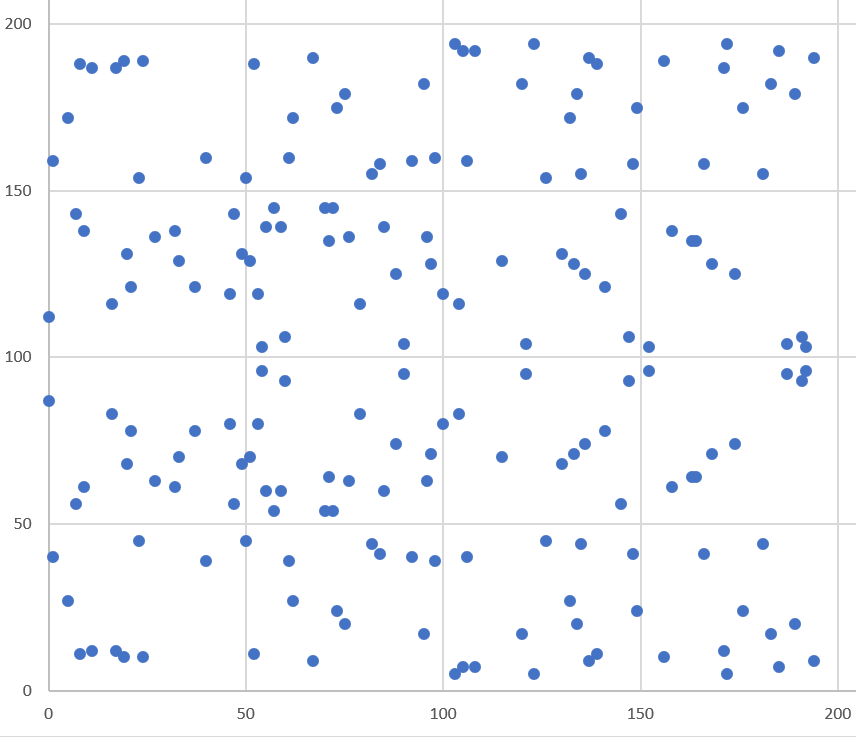

Because we’re evaluating the equation over a Finite Field, the plot of the equation looks vastly different (Figure 3-2):

As you can see, it’s very much a scattershot of points and there’s no smooth curve here. This is not surprising since the points are discrete. About the only pattern is that the curve is symmetric right around the middle, which is due to the y2 term. The graph is not symmetric over the x-axis as in the curve over reals, but about half-way up the y-axis due to there not being negative numbers in a Finite Field.

What’s amazing is that we can use the same point addition equations with the addition, subtraction, multiplication, division and exponentiation as we defined them for Finite Fields and everything still works. This may seem surprising, but abstract math has regularities like this despite being different than the traditional modes of calculation you may be familiar with.

Evaluate whether these points are on the curve y2=x3+7 over F223

(192,105), (17,56), (200,119), (1,193), (42,99)

Because we defined an Elliptic Curve point and we defined the +, - ,* and / operators for Finite Fields, we can combine the two classes to create Elliptic Curve points over a Finite Field.

>>>fromeccimportFieldElement,Point>>>a=FieldElement(num=0,prime=223)>>>b=FieldElement(num=7,prime=223)>>>x=FieldElement(num=192,prime=223)>>>y=FieldElement(num=105,prime=223)>>>p1=Point(x,y,a,b)>>>(p1)Point(FieldElement_223(192),FieldElement_223(105))_FieldElement_223(0)_FieldElement_223(7)

When initializing Point, we will run through this part of the code:

classPoint:def__init__(self,x,y,a,b):self.a=aself.b=bself.x=xself.y=yifself.xisNoneandself.yisNone:returnifself.y**2!=self.x**3+a*x+b:raiseValueError('({}, {}) is not on the curve'.format(x,y))

The addition (+), multiplication (*), exponentiation (**) and equality (!=) here use the __add__, __mul__, __pow__ and __ne__ methods from FiniteField respectively and not the integer equivalents.

Being able to do the same equation but with different definitions for the basic arithmetic operators is how we construct an Elliptic Curve Cryptography library.

We’ve already coded the two classes that we need to implement Elliptic Curve points over a Finite Field. However, to check our work, it will be useful to create a test suite. We will do this using the results of Exercise 2.

classECCTest(TestCase):deftest_on_curve(self):prime=223a=FieldElement(0,prime)b=FieldElement(7,prime)valid_points=((192,105),(17,56),(1,193))invalid_points=((200,119),(42,99))forx_raw,y_rawinvalid_points:x=FieldElement(x_raw,prime)y=FieldElement(y_raw,prime)Point(x,y,a,b)forx_raw,y_rawininvalid_points:x=FieldElement(x_raw,prime)y=FieldElement(y_raw,prime)withself.assertRaises(ValueError):Point(x,y,a,b)

We pass in FieldElement objects into the Point class for initialization.

This will, in turn, use all the overloaded math operations in FieldElement

We can now run this test like so:

>>>importecc>>>fromhelperimportrun>>>run(ecc.ECCTest('test_on_curve')).----------------------------------------------------------------------Ran1testin0.001sOK

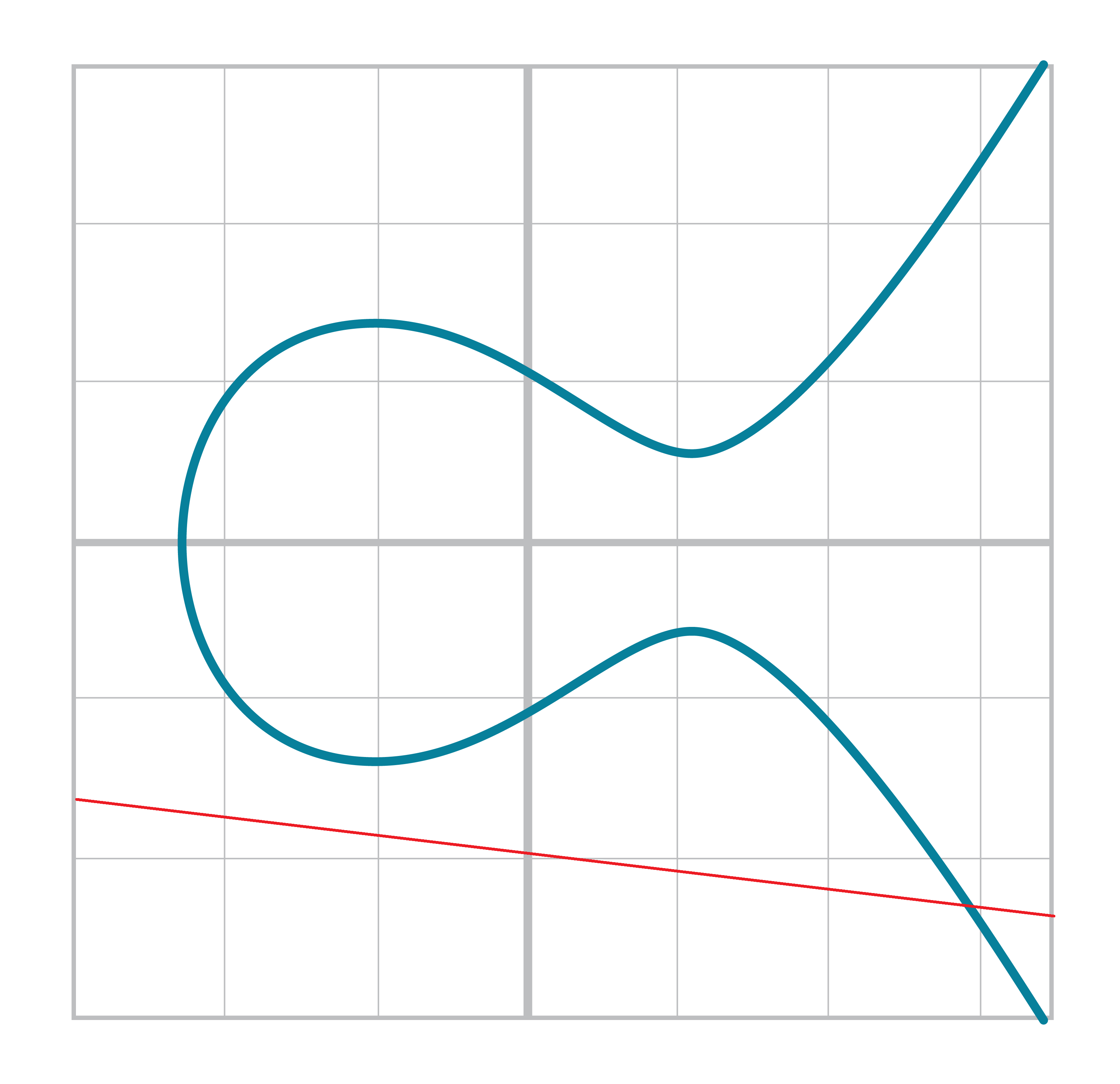

We can use all the same equations over Finite Fields, including the linear equation:

y=mx+b

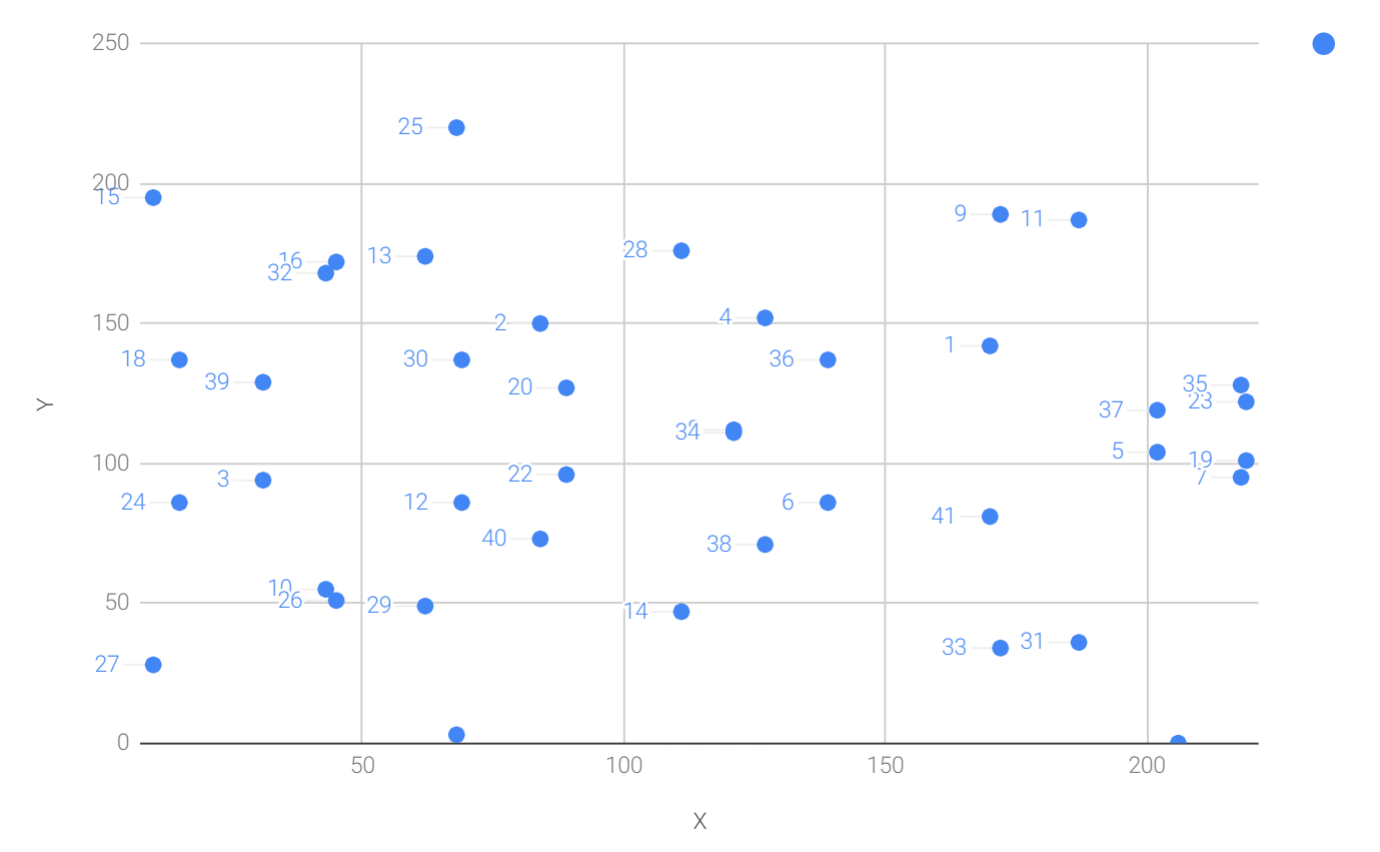

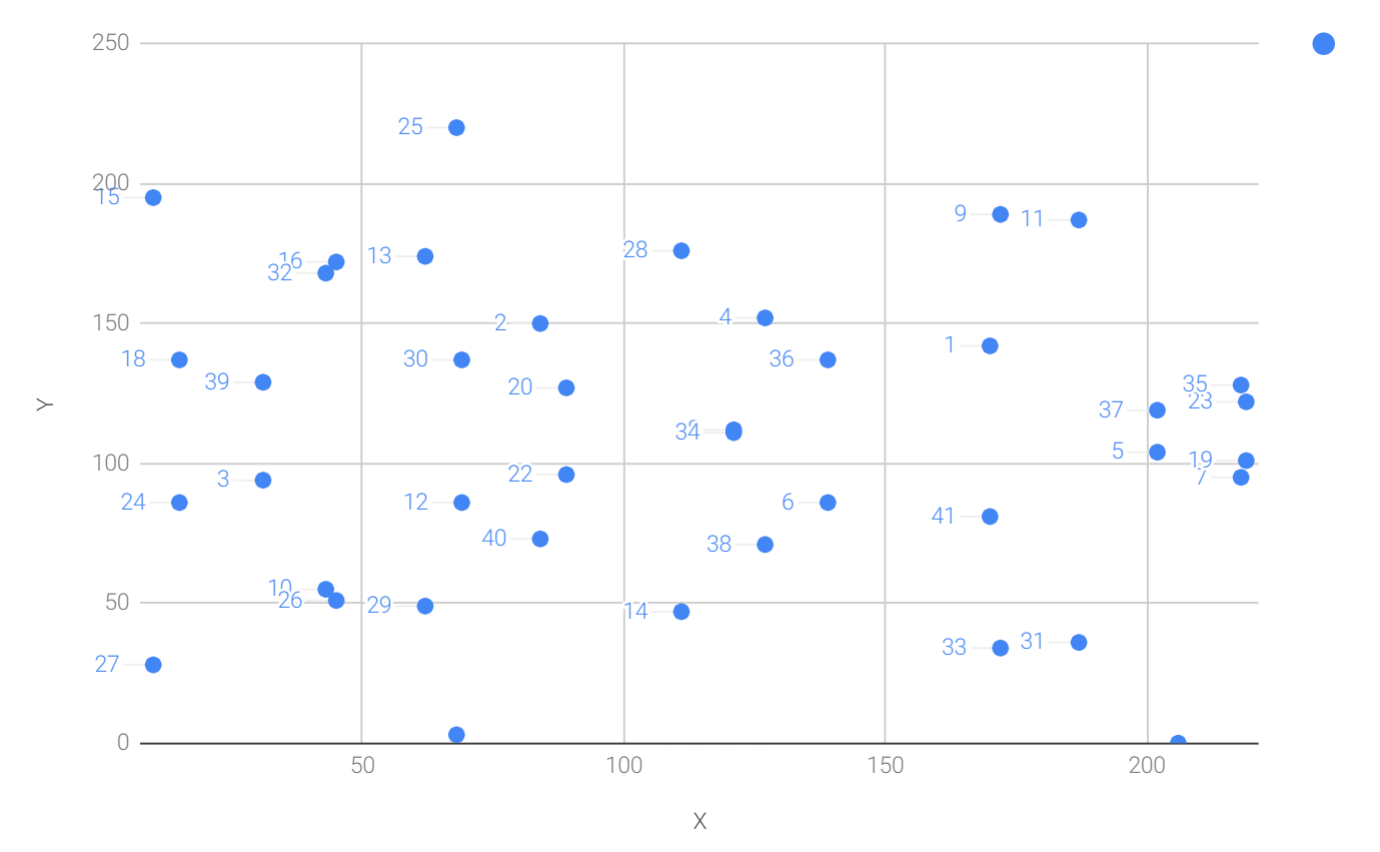

It turns out that a “line” in a Finite Field is not quite what you’d expect (Figure 3-3):

The equation nevertheless works and we can calculate what y should be for a given x.

Remarkably, point addition works over Finite Fields as well. This is because the Elliptic Curve point addition works over all fields! The same exact formulas we used to calculate point addition over reals work over Finite Fields. Specifically:

when x1≠x2:

P1=(x1,y1), P2=(x2,y2), P3=(x3,y3)

P1+P2=P3

s=(y2-y1)/(x2-x1)

x3=s2-x1-x2

y3=s(x1-x3)-y1

when P1=P2:

P1=(x1,y1), P3=(x3,y3)

P1+P1=P3

s=(3x12+a)/(2y1)

x3=s2-2x1

y3=s(x1-x3)-y1

All of the equations for Elliptic Curves work over Finite Fields and that sets us up to create some cryptographic primitives.

Because we coded FieldElement in such a way as to define __add__, __sub__, __mul__, __truediv__, __pow__, __eq__ and __ne__, we can simply initialize Point with FieldElement objects and point addition will work:

>>>fromeccimportFieldElement,Point>>>prime=223>>>a=FieldElement(num=0,prime=prime)>>>b=FieldElement(num=7,prime=prime)>>>x1=FieldElement(num=192,prime=prime)>>>y1=FieldElement(num=105,prime=prime)>>>x2=FieldElement(num=17,prime=prime)>>>y2=FieldElement(num=56,prime=prime)>>>p1=Point(x1,y1,a,b)>>>p2=Point(x2,y2,a,b)>>>(p1+p2)Point(FieldElement_223(170),FieldElement_223(142))_FieldElement_223(0)_FieldElement_223(7)

For the curve y2=x3+7 over F223, find:

(170,142) + (60,139)

(47,71) + (17,56)

(143,98) + (76,66)

Extend ECCTest to test for the additions from the previous exercise. Call this test_add.

Because we can add a point to itself, we can introduce some new notation:

(170,142) + (170,142) = 2⋅(170,142)

Similarly, because we have associativity, we can actually add the point again:

2⋅(170,142) + (170,142) = 3⋅(170, 142)

We can do this as many times as we want. This is what we call Scalar Multiplication. That is, we have a scalar number in front of the point. We can do this because we have defined point addition and point addition is associative.

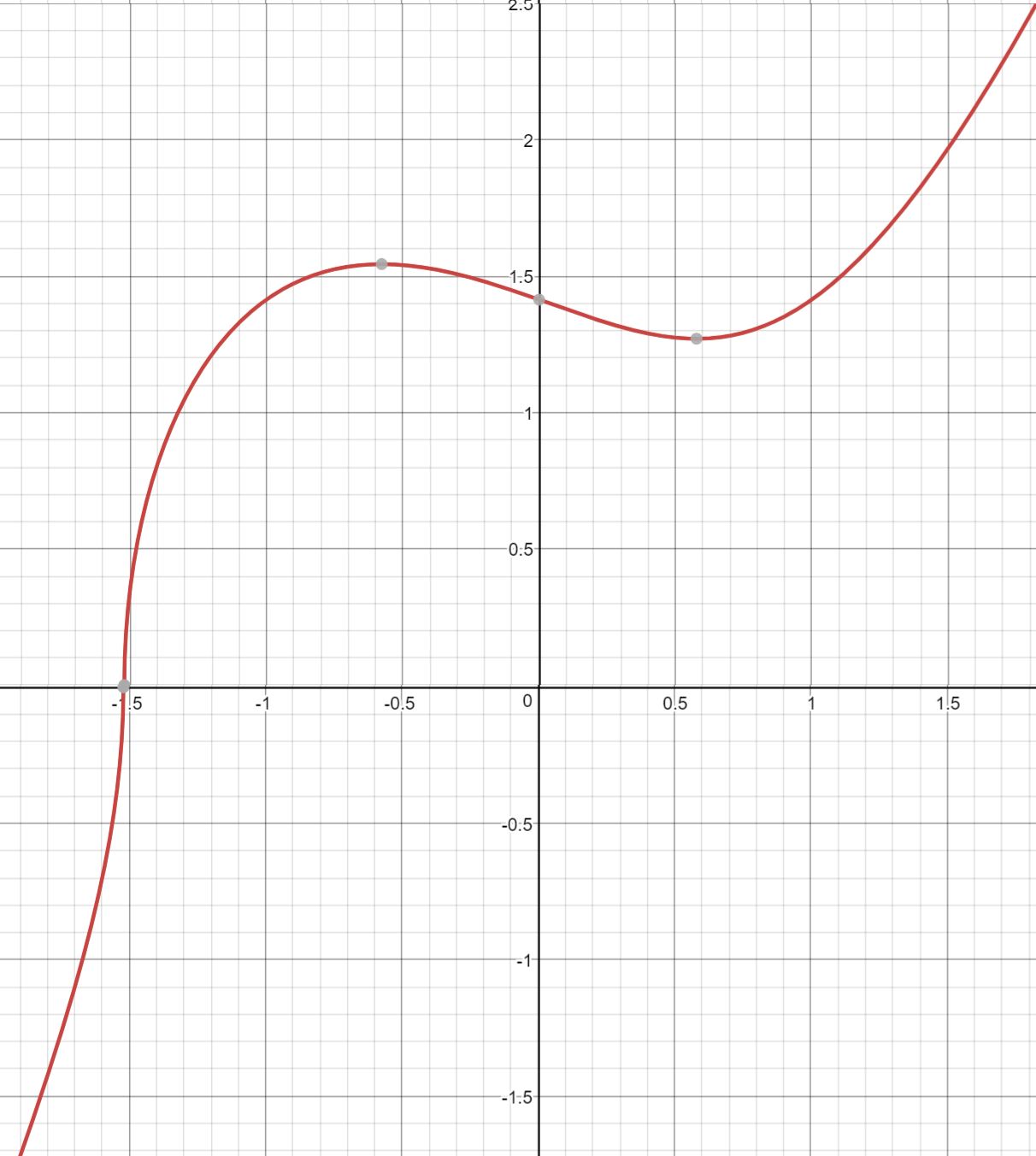

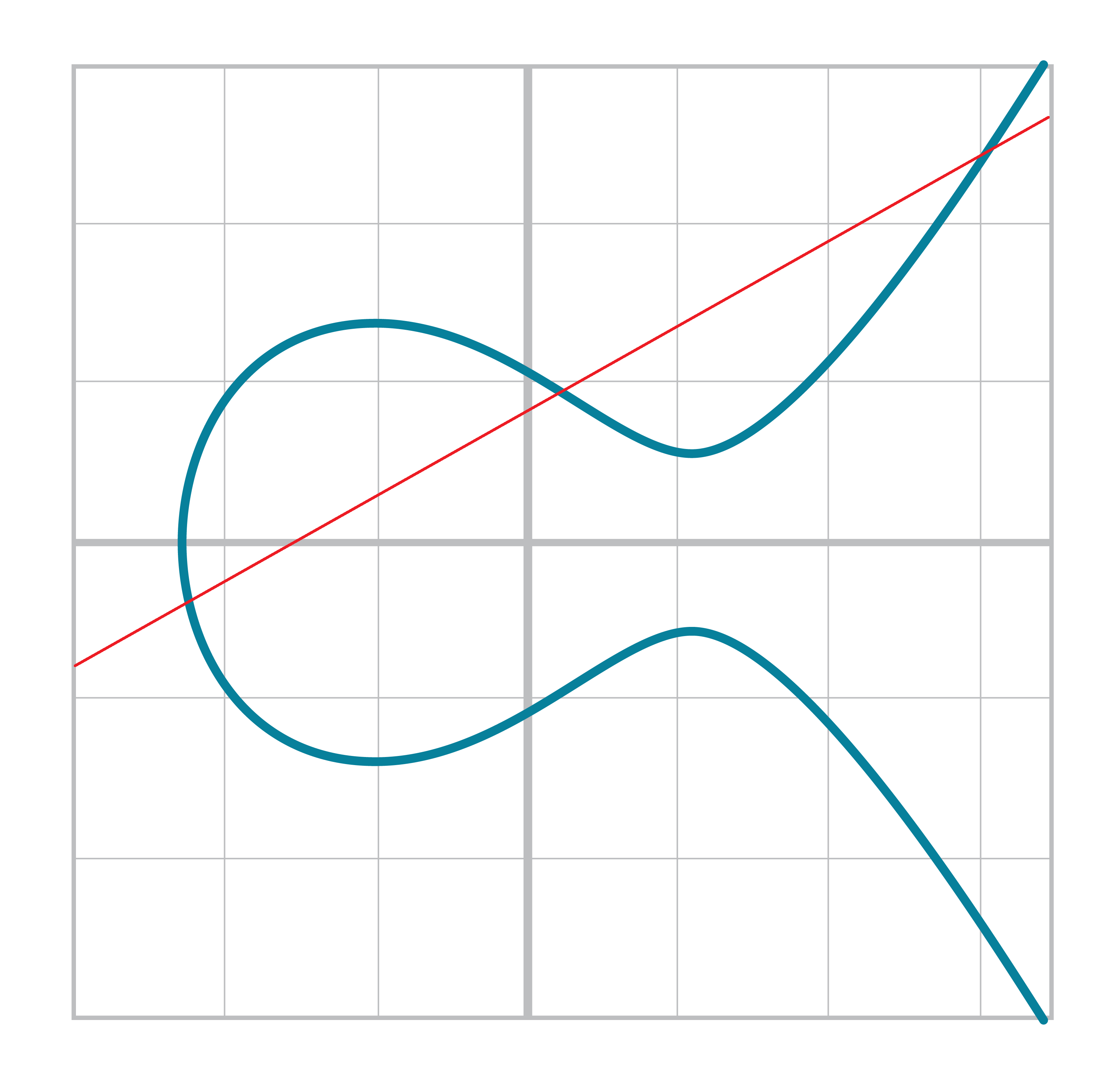

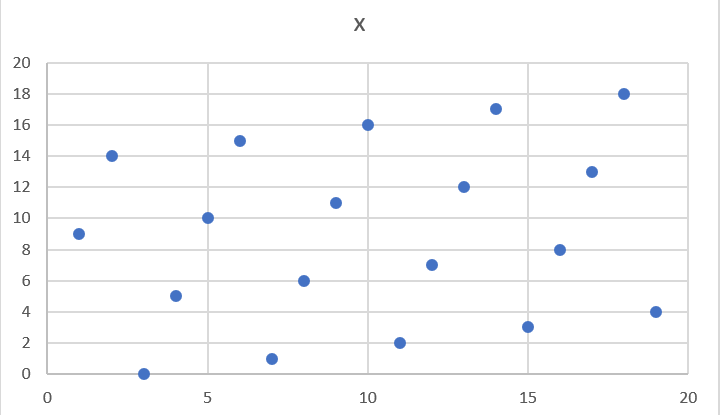

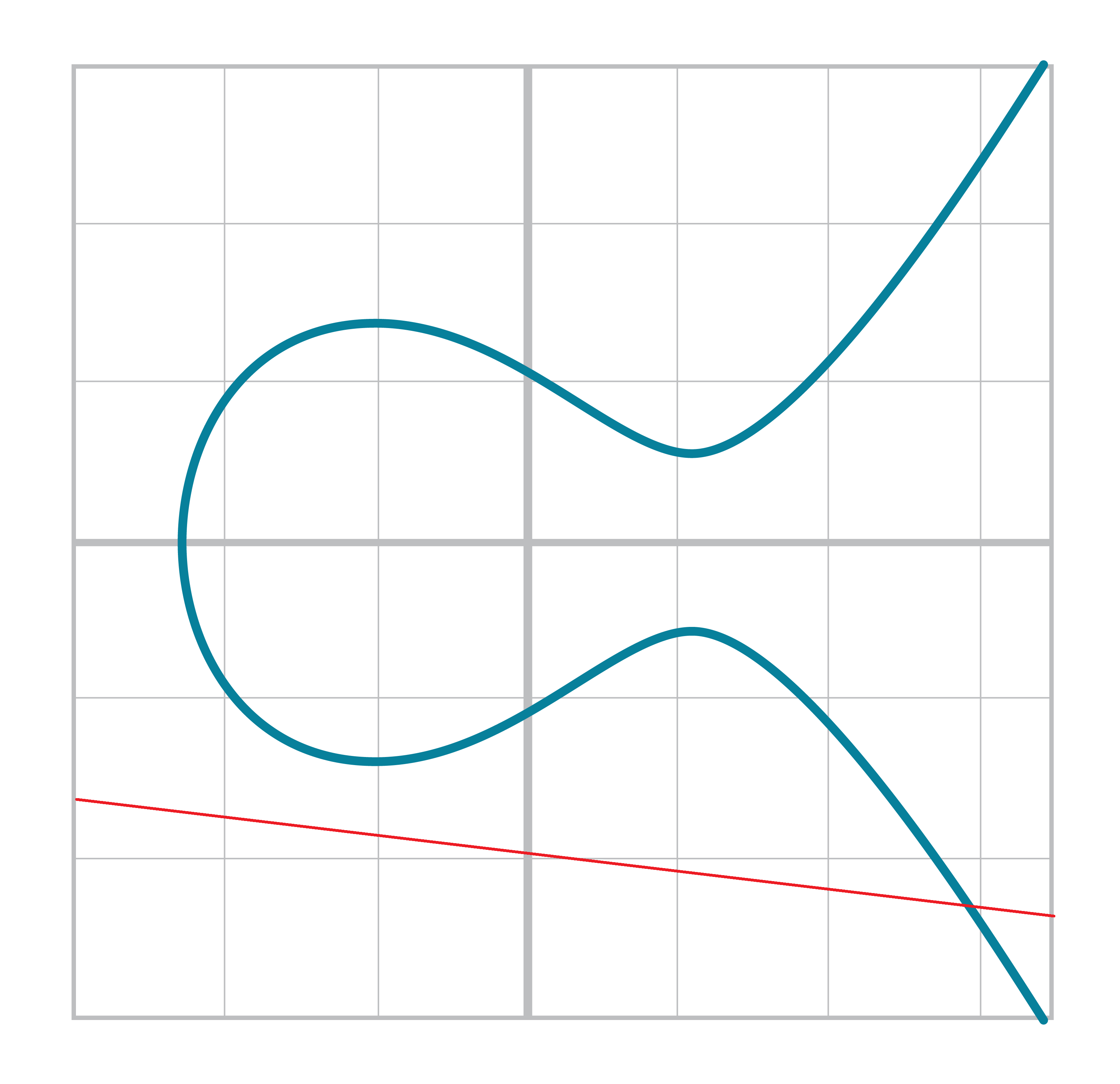

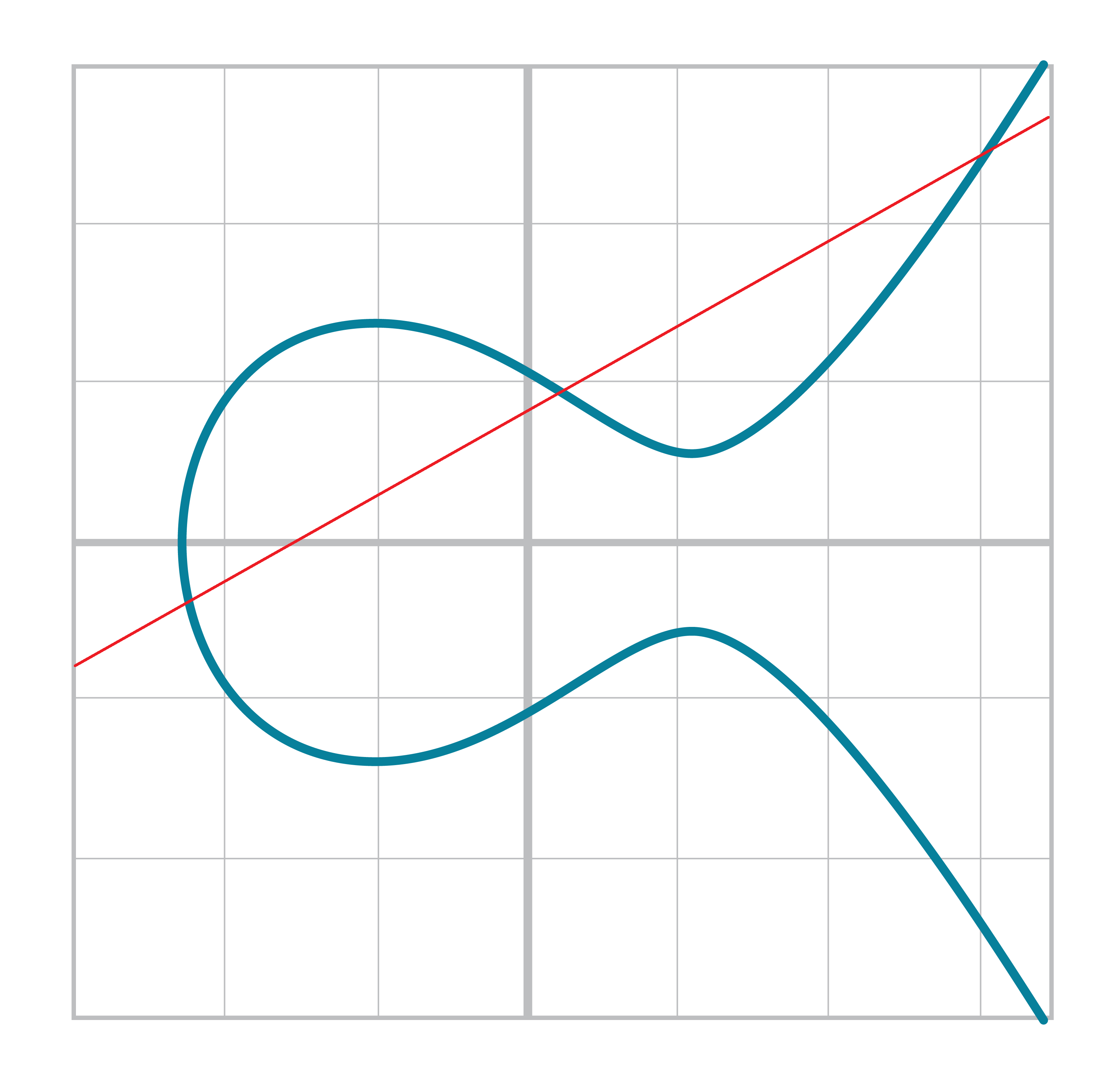

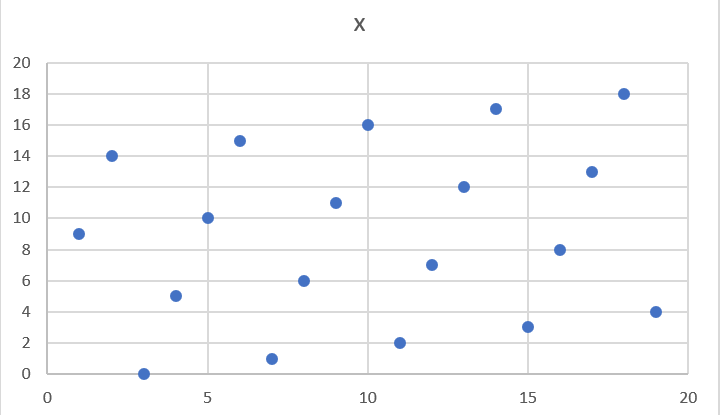

One property of scalar multiplication is that it’s really hard to predict without calculating (see Figure 3-4):

Each point is labeled by how many times we’ve added the point. You can see that this is a complete scattershot. This is because point addition is non-linear and not easy to calculate. Performing scalar multiplication is straightforward, but doing the opposite, Point division, is not.

This is called the Discrete Log problem and is the basis of Elliptic Curve Cryptography.

Another property of scalar multiplication is that at a certain multiple, we get to the point at infinity (remember, point at infinity is the additive identity or 0). If we imagine a point G and scalar multiply until we get the point at infinity, we end up with a set:

{ G, 2G, 3G, 4G, … nG } where nG=0

It turns out that this set is called a Group and because n is finite, we have a Finite Group (or more specifically a Finite Cyclic Group).

Groups are interesting mathematically because they behave a lot like addition:

G+4G=5G or aG+bG=(a+b)G

When we combine the fact that scalar multiplication is easy to go in one direction but hard in the other and the mathematical properties of a Group, we have exactly what we need for Elliptic Curve Cryptography.

For the curve y2=x3+7 over F223, find:

2⋅(192,105)

2⋅(143,98)

2⋅(47,71)

4⋅(47,71)

8⋅(47,71)

21⋅(47,71)

Scalar Multiplication is adding the same point to itself some number of times.

The key making scalar multiplication into Public Key Cryptography is the fact that scalar multiplication on Elliptic Curves is very hard to reverse.

Note the previous exercise.

Most likely, you calculated the point s⋅(47,71) in F223 for s from 1 until 21.

Here are the results:

>>>fromeccimportFieldElement,Point>>>prime=223>>>a=FieldElement(0,prime)>>>b=FieldElement(7,prime)>>>x=FieldElement(47,prime)>>>y=FieldElement(71,prime)>>>p=Point(x,y,a,b)>>>forsinrange(1,21):...result=s*p...('{}*(47,71)=({},{})'.format(s,result.x.num,result.y.num))1*(47,71)=(47,71)2*(47,71)=(36,111)3*(47,71)=(15,137)4*(47,71)=(194,51)5*(47,71)=(126,96)6*(47,71)=(139,137)7*(47,71)=(92,47)8*(47,71)=(116,55)9*(47,71)=(69,86)10*(47,71)=(154,150)11*(47,71)=(154,73)12*(47,71)=(69,137)13*(47,71)=(116,168)14*(47,71)=(92,176)15*(47,71)=(139,86)16*(47,71)=(126,127)17*(47,71)=(194,172)18*(47,71)=(15,86)19*(47,71)=(36,112)20*(47,71)=(47,152)

If we look closely at the numbers, there’s no real discernible pattern to the scalar multiplication. The x-coordinates don’t always increase or decrease and neither do the y-coordinates. About the only pattern is that between 10 and 11, the x-coordinates are equal (10 and 11 have the same x, as do 9 and 12, 8 and 13 and so on). This is due to the fact that 21⋅(47,71)=0.

Scalar multiplication looks really random and that’s what gives this equation asymmetry. An asymmetric problem is one that’s easy to calculate in one direction, but hard to reverse. For example, it’s easy enough to calculate 12⋅(47,71). But if we were presented this:

s⋅(47,71)=(194,172)

Would you be able to solve for s?

We can look up the table above, but that’s because we have a small group.

We’ll see later that when we have numbers that are a lot larger, Discrete Log becomes an intractable problem.

The preceding math (Finite Fields, Elliptic Curves, combining the two), was really to bring us to this point. What we really want to generate for the purposes of Public Key Cryptography are Finite Cyclic Groups and it turns out that if we take a Generator Point from an Elliptic Curve over a Finite Field, we can generate a Finite Cyclic Group.

Unlike fields, groups have only a single operation. In our case, Point Addition is our operation. We also have a few other properties like closure, invertibility, commutativity and associativity. Lastly, we need the identity.

Let’s look at each property.

If you haven’t guessed by now, the identity is defined as the point at infinity, which is guaranteed to be in the group since we generate the group when we get to the point at infinity. So:

0 + A = A

We call 0 the point at infinity because visually, it’s the point that exists to help the math work out (Figure 3-5):

This is perhaps the easiest to prove since we generated the group in the first place by adding G over and over. Thus, two different elements look like this:

aG + bG

We know that the result is going to be:

(a+b)G

How do we know if this element is in the group?

If a+b < n (where n is the order of the group), then we know it’s in the group by definition.

If a+b >= n, then we know a < n and b < n, so a+b<2n so a+b-n<n.

(a+b-n)G=aG+bG-nG=aG+bG-0=aG+bG

More generally (a+b)G=((a+b)%n)G where n is the order of the group.

So we know that this element is in the group, proving closure.

Visually, invertibility is easy to see (Figure 3-6):

Mathematically, we know that if aG is in the group, (n-a)G is also in the group. You can add them together to get aG+(n-a)G=(a+n-a)G=nG=0.

We know from Point Addition that A+B=B+A (Figure 3-7):

This means that aG+bG=bG+aG, which proves commutativity.

For the curve y2=x3+7 over F223, find the order of the group generated by (15,86)

What we’re trying to do with the last exercise is this:

>>>fromeccimportFieldElement,Point>>>prime=223>>>a=FieldElement(0,prime)>>>b=FieldElement(7,prime)>>>x=FieldElement(15,prime)>>>y=FieldElement(86,prime)>>>p=Point(x,y,a,b)>>>(7*p)Point(infinity)

We want to be able to scalar multiply the point with some number.

Thankfully, there’s a method in Python called __rmul__ that can be used to override the front multiplication.

A naive implementation looks something like this:

classPoint:...def__rmul__(self,coefficient):product=self.__class__(None,None,self.a,self.b)for_inrange(coefficient):product+=selfreturnproduct

We start the product at 0, which in the case of Point Addition is the point at infinity.

We loop coefficient times and add the point each time

This is fine for small coefficients, but what if we have a very large coefficient? That is, a number that’s so large that we won’t be able to get out of this loop in a reasonable amount of time? For example, a coefficient of 1 trillion is going to take a really long time.

There’s a really cool technique called binary expansion that allows us to perform multiplication in log2(n) loops, which dramatically reduces the calculation time for large numbers.

For example, 1 trillion is 40 bits in binary, so we only have to loop 40 times for a number that’s generally considered very large.

classPoint:...def__rmul__(self,coefficient):coef=coefficientcurrent=selfresult=self.__class__(None,None,self.a,self.b)whilecoef:ifcoef&1:result+=currentcurrent+=currentcoef>>=1returnresult

current represents the point that’s at the current bit.

First time through the loop it represents 1*self, the second time, it will be 2*self, third time, 4*self, then 8*self and so on.

We double the point each time.

In binary the coefficients are 1, 10, 100, 1000, 10000, etc.

We start the result at 0, or the point at infinity.

We are looking at whether the right-most bit is a 1. If it is, then we add the value of the current bit.

We need to double the point until we’re past how big the coefficient can be.

We bit shift the coefficient to the right.

This is an advanced technique and if you don’t understand bitwise operators, think of representing the coefficient in binary and only adding the point where there are 1’s.

With __add__ and __rmul__, we can start defining some more complicated Elliptic Curves.

While we’ve been using relatively small primes for the sake of examples, we are not restricted to such small numbers. Small primes mean that we can use a computer to search through the entire Group. If the group has a size of 301, the computer can easily do 301 computations to reverse scalar multiplication or break Discrete Log.

But what if we made the prime larger? It turns out that we can choose much larger primes than we’ve been using. The security of Elliptic Curve Cryptography depends on computers not being able to go through the an appreciable fraction of the group.

An Elliptic Curve for Public Key Cryptography is defined with the following parameters:

We specify the a and b of the curve y2=x3+ax+b.

We specify the prime of the Finite Field, p.

We specify the x and y coordinates of the generator point G

We specify the order of the group generated by G, n.

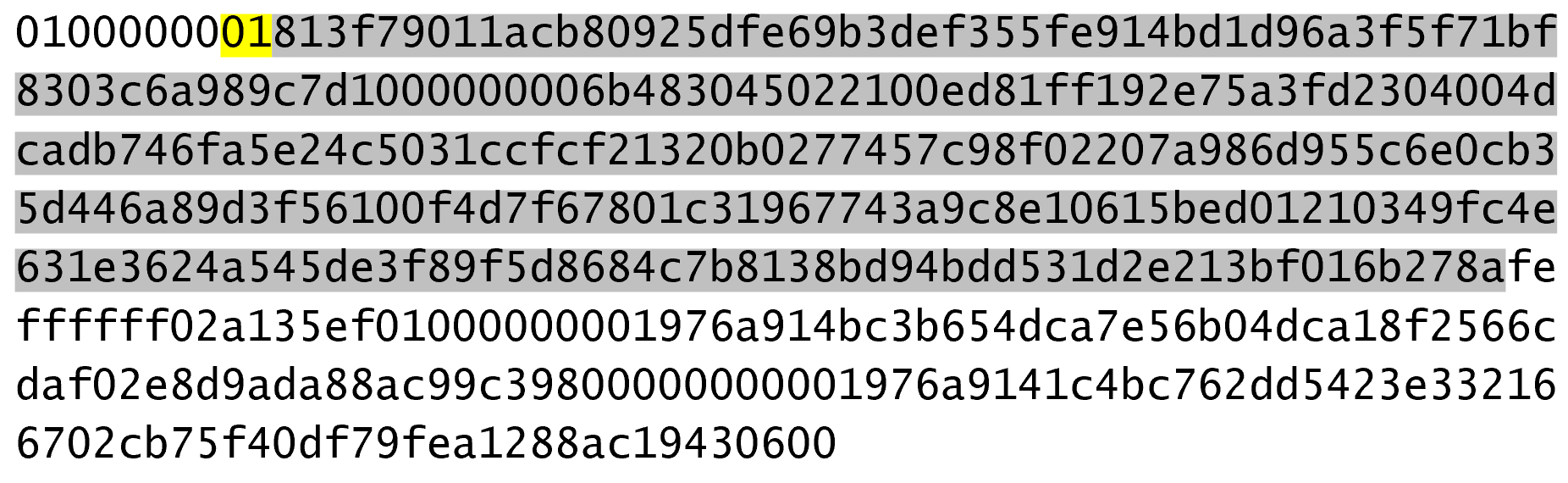

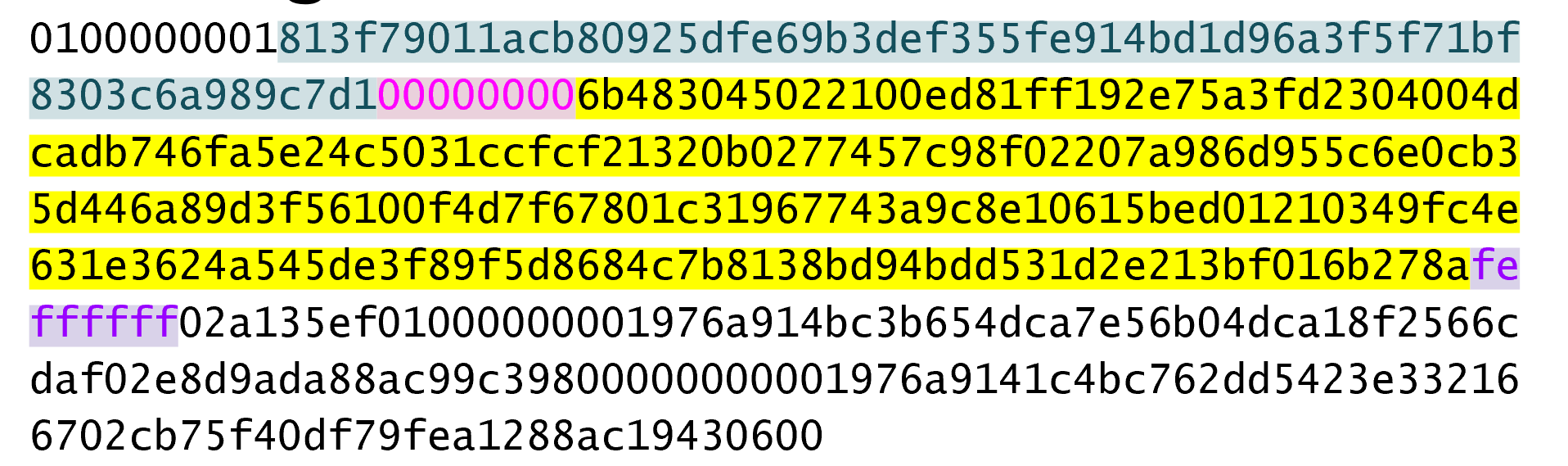

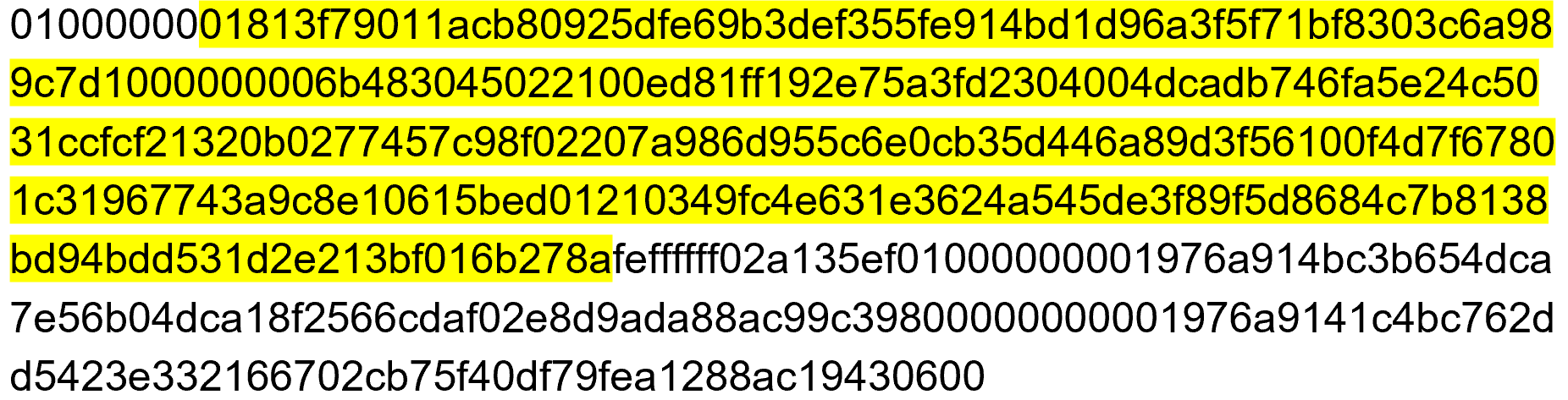

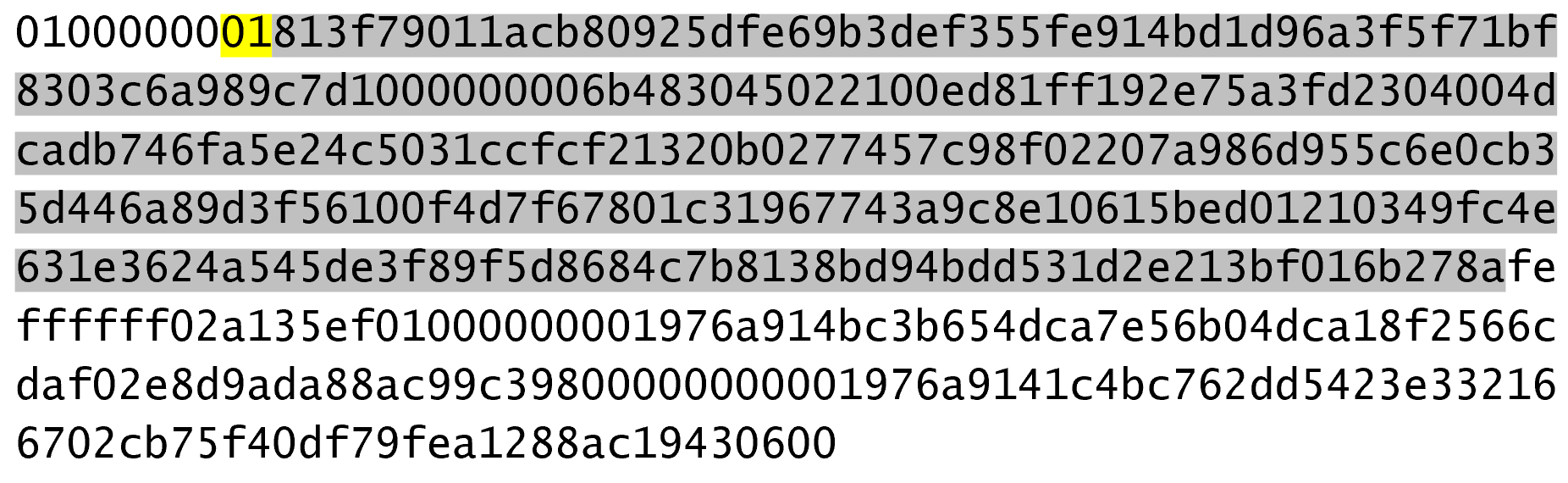

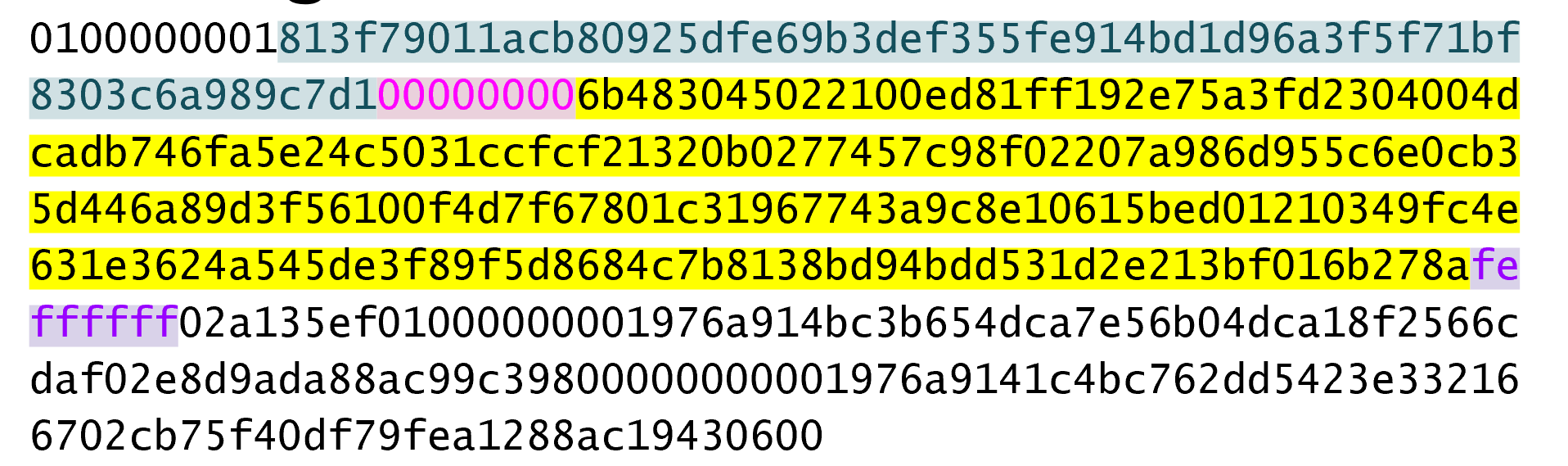

These numbers are known publicly and together form the cryptographic curve. There are many cryptographic curves and they have different security/convenience trade-offs, but the one we’re most interested in is the one Bitcoin uses: secp256k1. The parameters for secp256k1 are these:

a = 0, b = 7, making the equation y2=x3+7

p = 2256-232-977

Gx =

0x79be667ef9dcbbac55a06295ce870b07029bfcdb2dce28d959f2815b16f81798

Gy =

0x483ada7726a3c4655da4fbfc0e1108a8fd17b448a68554199c47d08ffb10d4b8

n =

0xfffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffebaaedce6af48a03bbfd25e8cd0364141

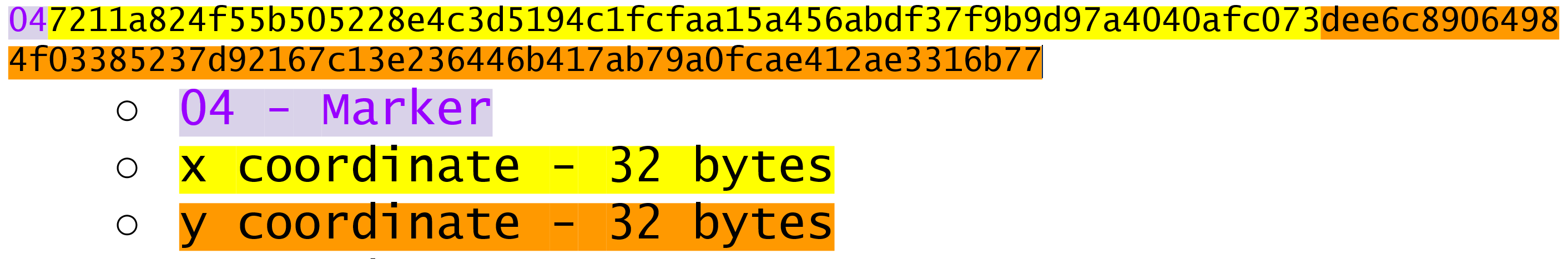

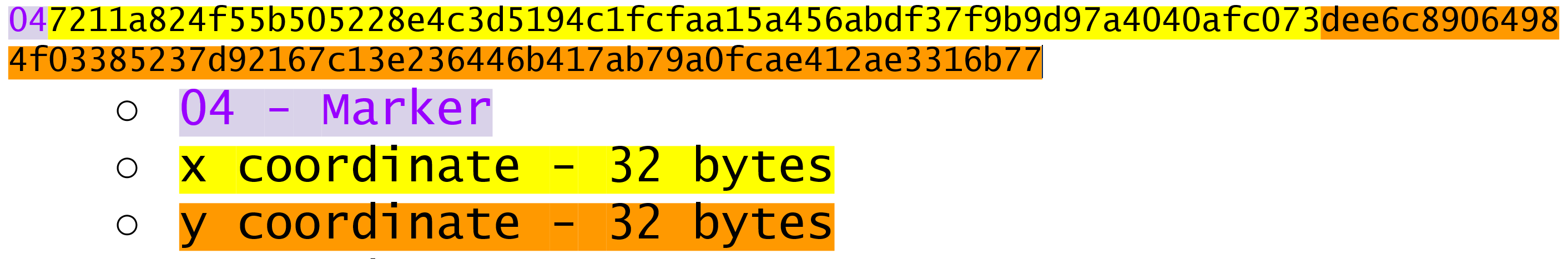

Gx refers to the x-coordinate of the point G and Gy the y-coordinate.

The numbers starting with 0x indicate a hexadecimal number.

There are a few things to notice about this curve.

First, the equation is relatively simple.

Many curves have a and b that are much bigger.

secp256k1 has a really simple equation.

Second, p is really, really close to 2256.

This means that most numbers under 2256 are in the prime field and thus, any point on the curve has x and y-coordinates that are expressible in 256-bits each.

n is also very close to 2256.

This means any scalar multiple can also be expressed in 256 bits.

Third, 2256 is a really big number (See the How Big is 2256). Amazingly, any number below 2256 can be stored in 32 bytes. This means that we can store the private key relatively easily.

Since we know all of the parameters for secp256k1, we can verify in Python whether the generator point, G, is on the curve y2=x3+7:

>>>gx=0x79be667ef9dcbbac55a06295ce870b07029bfcdb2dce28d959f2815b16f81798>>>gy=0x483ada7726a3c4655da4fbfc0e1108a8fd17b448a68554199c47d08ffb10d4b8>>>p=2**256-2**32-977>>>(gy**2%p==(gx**3+7)%p)True

Furthermore, we can verify in Python whether the generator point, G, has the order n.

>>>fromeccimportFieldElement,Point>>>gx=0x79be667ef9dcbbac55a06295ce870b07029bfcdb2dce28d959f2815b16f81798>>>gy=0x483ada7726a3c4655da4fbfc0e1108a8fd17b448a68554199c47d08ffb10d4b8>>>p=2**256-2**32-977>>>n=0xfffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffebaaedce6af48a03bbfd25e8cd0364141>>>x=FieldElement(gx,p)>>>y=FieldElement(gy,p)>>>seven=FieldElement(7,p)>>>zero=FieldElement(0,p)>>>G=Point(x,y,zero,seven)>>>(n*G)Point(infinity)

Since we know the curve we will work in, this is a good time to create a subclass in Python to work exclusively with the parameters for secp256k1.

We’ll define the equivalent FieldElement and Point objects, but specific to the secp256k1 curve.

Let’s start by defining the field we’ll be working in.

P=2**256-2**32-977...classS256Field(FieldElement):def__init__(self,num,prime=None):super().__init__(num=num,prime=P)def__repr__(self):return'{:x}'.format(self.num).zfill(64)

We’re subclassing the FieldElement class so we don’t have to pass in P all the time.

We also want to display a 256-bit number consistently by filling 64 characters so we can see any leading zeroes.

Similarly, we can define a point on the secp256k1 curve and call it S256Point.

A=0B=7...classS256Point(Point):def__init__(self,x,y,a=None,b=None):a,b=S256Field(A),S256Field(B)iftype(x)==int:super().__init__(x=S256Field(x),y=S256Field(y),a=a,b=b)else:super().__init__(x=x,y=y,a=a,b=b)

In case we initialize with the point at infinity, we need to let x and y through directly instead of using the S256Field class.

We now have an easier way to initialize a point on the secp256k1 curve, without having to define the a and b every time like we have to with the Point class.

We can also define __rmul__ a bit more efficiently since we know the order of the group, n.

Since we’re coding Python, we’ll name this with a capital N to make it clear that N is a constant.

N=0xfffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffebaaedce6af48a03bbfd25e8cd0364141...classS256Point(Point):...def__rmul__(self,coefficient):coef=coefficient%Nreturnsuper().__rmul__(coef)

We can mod by n because nG=0.

That is, every n times we cycle back to zero or the point at infinity.

We can now define G directly and keep it around since we’ll be using it a lot going forward.

G=S256Point(0x79be667ef9dcbbac55a06295ce870b07029bfcdb2dce28d959f2815b16f81798,0x483ada7726a3c4655da4fbfc0e1108a8fd17b448a68554199c47d08ffb10d4b8)

Now checking that the order of G is n is trivial:

>>>fromeccimportG,N>>>(N*G)S256Point(infinity)

Finally, we have the tools that we need to do Public Key Cryptography operations.

The key operation that we need is P=eG which is an asymmetric equation.

We can easily compute P when we know e and G, but we cannot easily compute e when we know P and G.

This is the Discrete Log Problem described earlier.

The difficulty of Discrete Log will be essential to understanding signing and verification algorithms.

Generally, we call e the Private Key and P the Public Key.

We’ll note here that the private key is a single 256-bit number and the public key is a coordinate (x,y) where x and y are each 256-bit numbers.

To set up the motivation for why signing and verification exists, imagine this scenario. You want to prove that you are a really good archer, like at the level where you can hit any target you want within 500 yards as opposed to being able to hit any single target.

Now if someone could observe you and interact with you, proving this would be easy. Perhaps they would position your son 400 yards away with an apple on his head and challenge you to hit that apple with an arrow. You, being a very good archer, do this and prove your expertise. The target, if specified by the challenger, makes your archery skill easy to verify.

Unfortunately, this doesn’t scale very well. If, for example you wanted to prove this to 10 people, you would have to shoot 10 different arrows at 10 different targets from 10 different challenges. You could try to do something like have 10 people watch you shoot a single arrow, but since they can’t all choose the target, they can never be sure that you’re not just good at hitting one particular target instead of an arbitrary target. What we want is something that you can do once, requires no interaction but still proves that you are indeed, a good archer that can hit any target.

If, for example, you shot an arrow into a target of your choosing, then the people observing afterwards won’t necessarily be convinced. After all, you may be a sneaky person that paints the target around wherever your arrow happened to land. So what can you do?

Here’s a very clever thing you can do. Inscribe the tip of the arrow with the position of the target that you’re hitting (“apple on top of my son’s head”) and then hit that target with your arrow. Now anyone seeing the target can take an x-ray machine and look at the tip of the embedded arrow and see that the tip indeed says exactly where it was going to hit. The tip clearly had to be inscribed before the arrow was shot, so this can prove you are indeed a good archer (provided the actual target isn’t just one that you’ve practiced over and over).

This is the same technique we’re using with signing and verification, except what we’re proving isn’t that we’re good archers, but that we know a secret number. We want to prove possession of the secret without revealing the secret itself. We do this by putting the target into our calculation and hitting that target.

Ultimately this is going to be used in Transactions which will prove that the rightful owners of the secrets are spending the Bitcoins.

The inscribing of the target depends on the signature algorithm, and in our case, our signature algorithm is called Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm, or ECDSA for short.

The secret in our case is e satisfying:

eG = P

Where P is the public key and e is the private key.

The target that we’re going to aim at is a random 256-bit number, k.

We then do this:

kG = R

R is our target that we’re aiming for.

In fact, we’re only going to care about the x-coordinate of R, which we’ll call r.

You may have guessed already that r here stands for random.

We claim at this point that the following equation is equivalent to the Discrete Log Problem:

uG+vP=kG where k was chosen randomly and u,v≠0 can be chosen by the signer and G and P are known

This is due to the fact that:

uG+vP=kG implies vP=(k-u)G

Since v≠0, we can divide by the scalar multiple v.

P=((k-u)/v)G

If we know e, we have:

eG=((k-u)/v)G or e = (k-u)/v

This means than any (u,v) combination that satisfies the above equation will suffice.

If we don’t know e, we would have to play with (u,v) until` e = (k-u)/v`.

If we could solve this with any (u,v) combination, that would mean we’ll have solved P=eG while knowing only P and G.

In other words, we’d have broken the Discrete Log problem.

This means to provide a correct u and v, we either have to break the Discrete Log problem or we know the secret e.

Since we assume Discrete Log is hard, we can say e is assumed to be known by the one who came up with u and v.

One subtle thing that we haven’t talked about is that we have to incorporate the purpose of our shooting. This is a contract that gets fulfilled as a result of the shooting at the target. William Tell, for example, was shooting so that he could save his son (shoot the target and you get to save your son). You can imagine there would be other reasons to hit the target and the “reward” that the person hitting the target would receive. This has to be incorporated into our equations.

In signature/verification parlance, this is called the signature hash.

A hash is a deterministic function that takes arbitrary data into a data of fixed size.

This is a fingerprint of the message containing the intent of the shooter that anyone verifying the message already knows.

We denote this with the letter z.

This is incorporated into our uG+vP calculation this way:

u = z/s, v = r/s

Since r is used in the calculation of v, we now have the tip of the arrow inscribed.

We also have the intent of the shooter incorporated into u, so both the reason for shooting and the target that is being aimed at are now a part of the equation.

To make the equation work, we can calculate s:

uG+vP=R=kG

uG+veG=kG

u+ve=k

z/s+re/s=k

(z+re)/s=k

s=(z+re)/k

This is the basis of the signature algorithm and the two numbers in a signature are r and s.

Verification is straightforward:

kAt this point, you might be wondering why we don’t reveal k and instead reveal the x-coordinate of R or r.

If we were to reveal k, then:

uG+vP=R

uG+veG=kG

kG-uG=veG

(k-u)G = veG

(k-u) = ve

(k-u)*1/v = e

Means that our secret would be revealed, which would defeat the whole purpose of the signature. We can, however, reveal R.

It’s worth mentioning again, make sure you’re using truly random numbers for k, as even accidentally revealing k for a known signature is the equivalent of revealing your secret and losing your funds!

Signatures sign some fixed-length value (our “contract”), in our case something that’s 32 bytes.

The fact that 32 bytes is 256 bits is not a coincidence as the thing we’re signing will be a scalar for G.

In order to guarantee that the thing we’re signing is 32 bytes, we hash the document first.

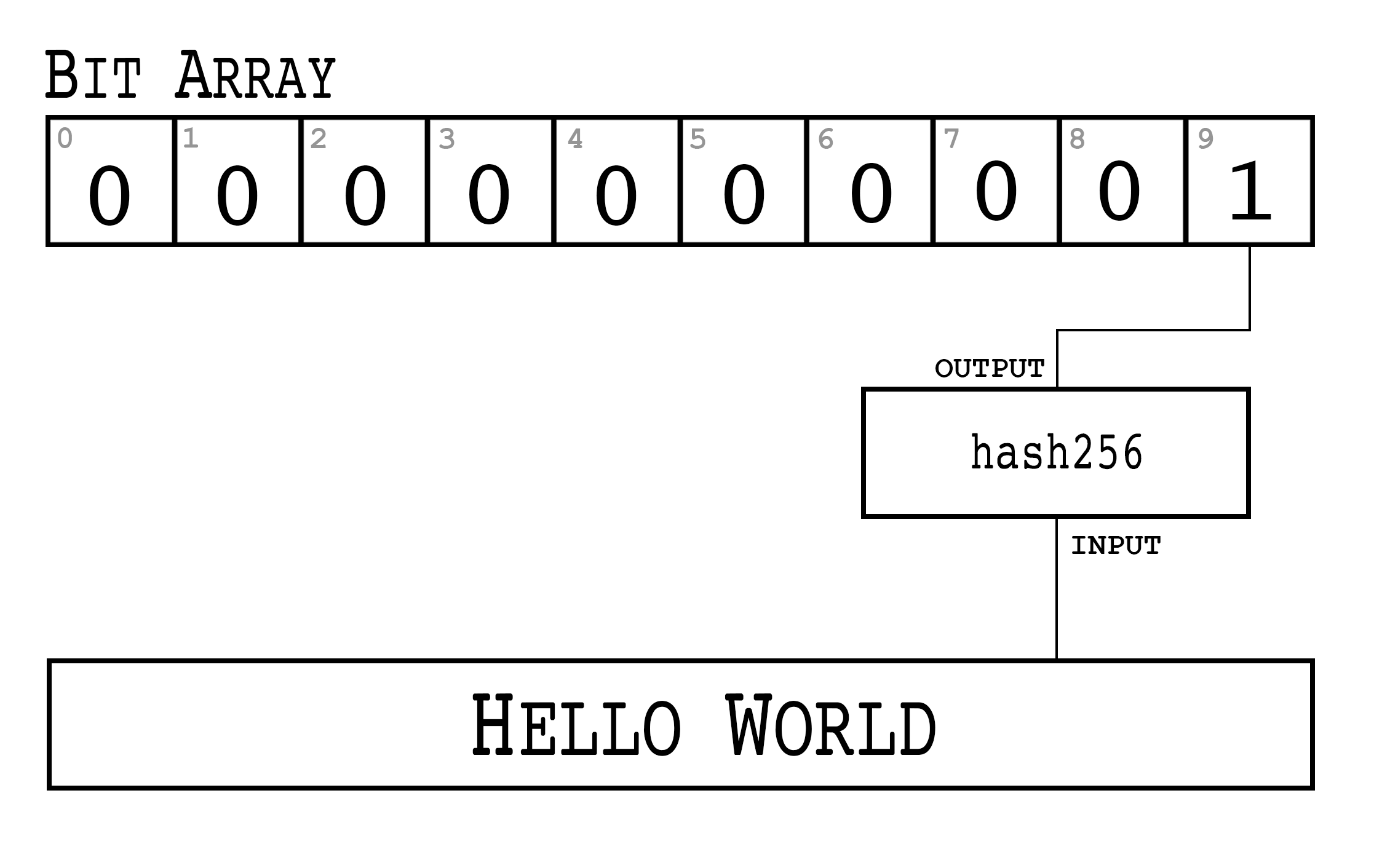

In Bitcoin, the hashing function is hash256, or two rounds of sha256.

This guarantees the thing that we’re signing is exactly 32 bytes.

We will call the result of the hash, the signature hash, or z.

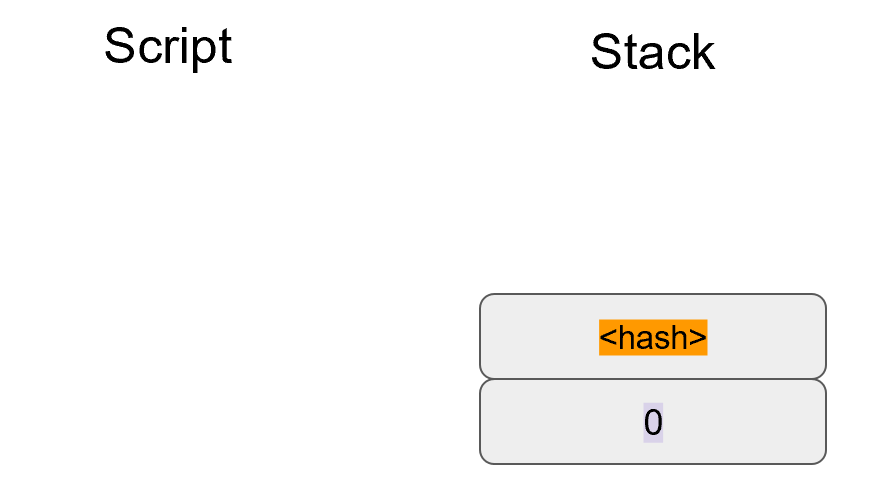

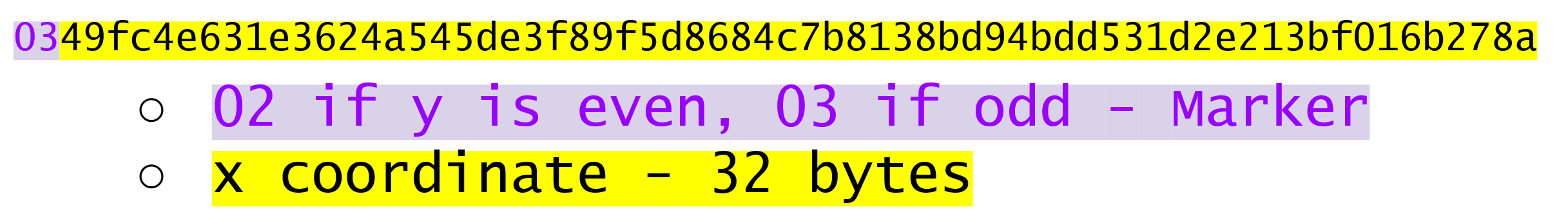

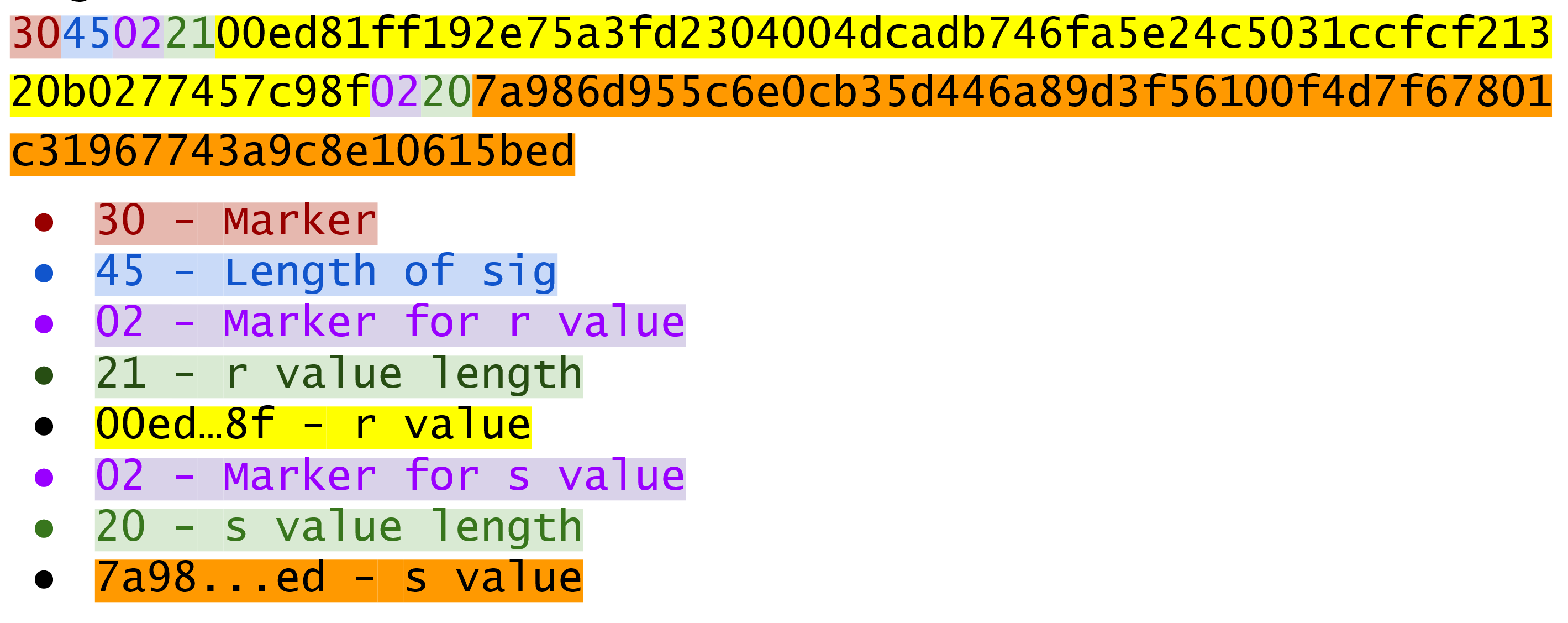

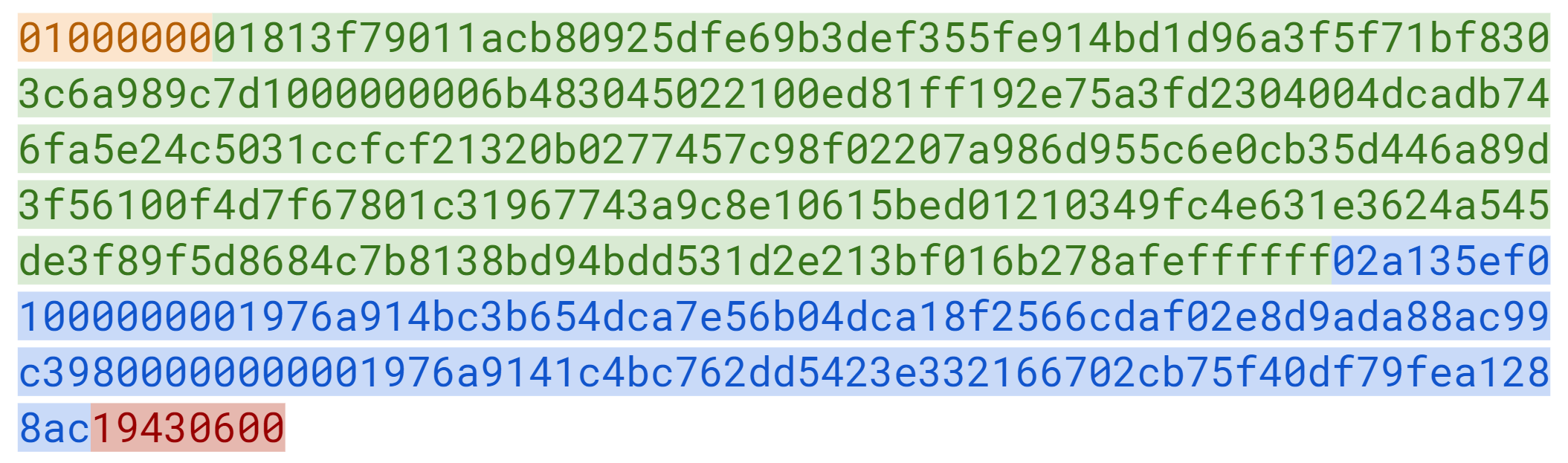

The signature that we are verifying has two components, (r, s).

The r is as above, it’s the x-coordinate of some point R that we’ll come back to.

The formula for s is as above:

s = (z+re)/k

Keep in mind that we know e (P = eG, or what we’re proving we know in the first place), we know k (kG = R, remember?) and we know z.

We will now construct R=uG+vP by defining u and v this way:

u = z/s

v = r/s

Thus:

uG + vP = (z/s)G + (r/s)P = (z/s)G + (re/s)G = ((z+re)/s)G

We know s = (z+re)/k so:

uG + vP = ( (z+re) / ((z+re)/k) )G = kG = R

We’ve successfully chosen u and v in a way as to generate R as we intended.

Furthermore, we used r in the calculation of v proving we knew what R should be.

The only way we could know the details of R beforehand is if we know e.

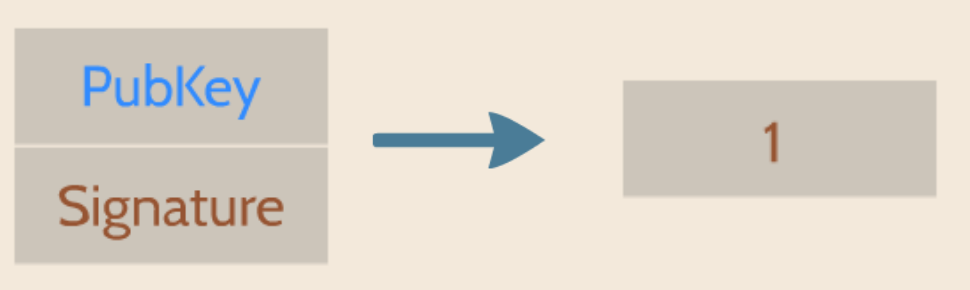

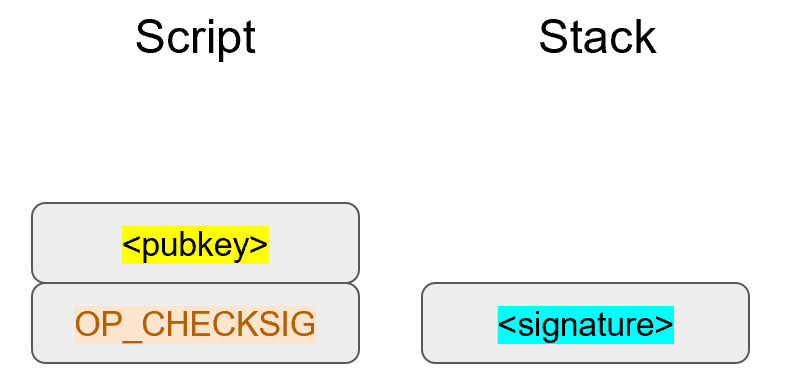

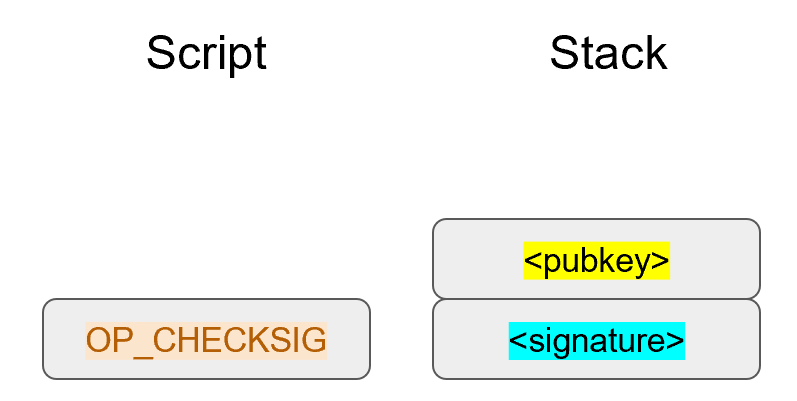

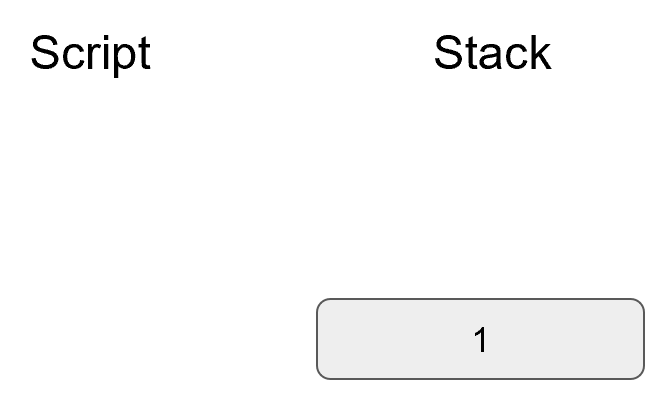

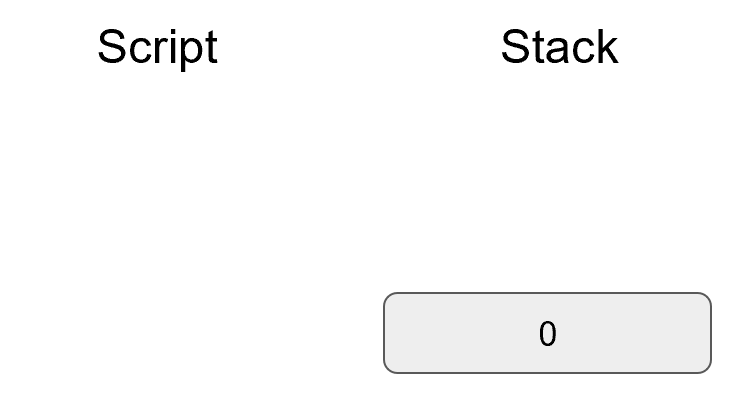

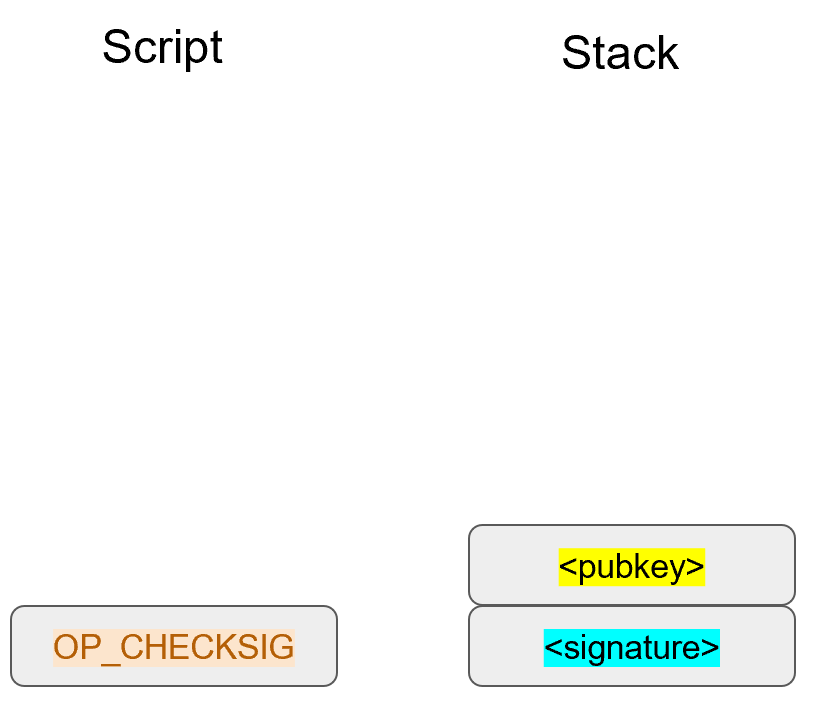

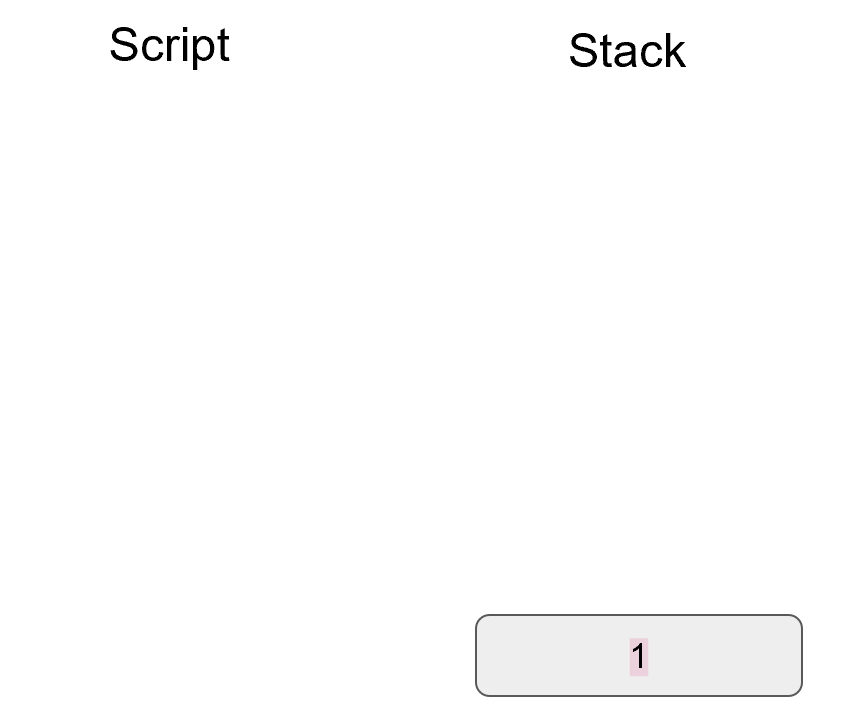

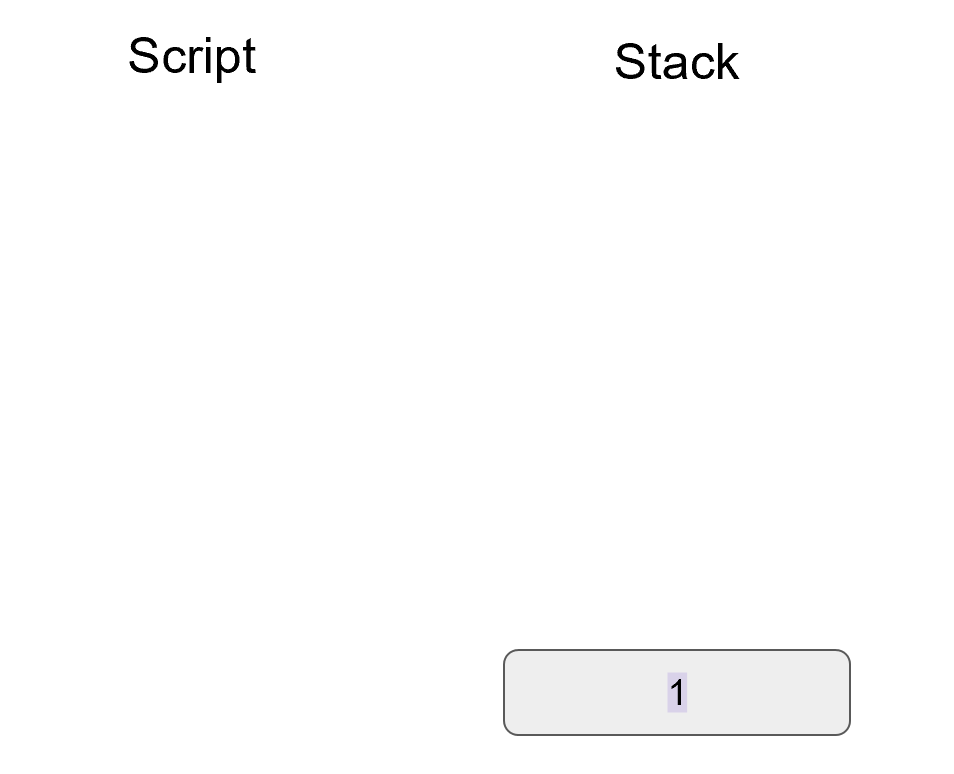

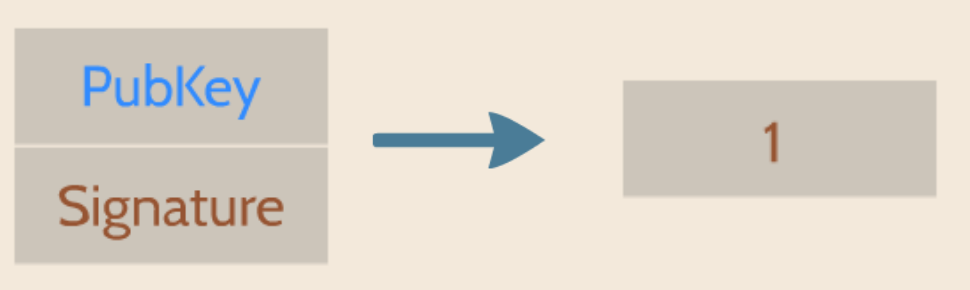

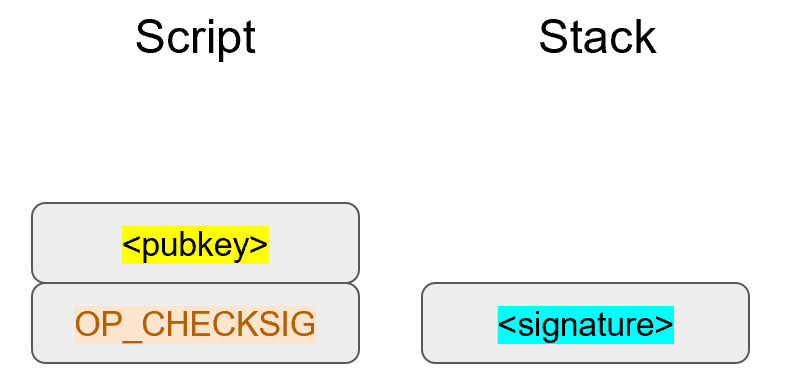

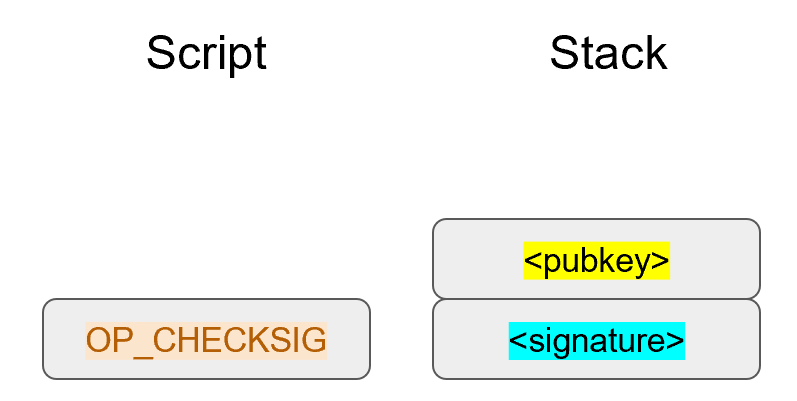

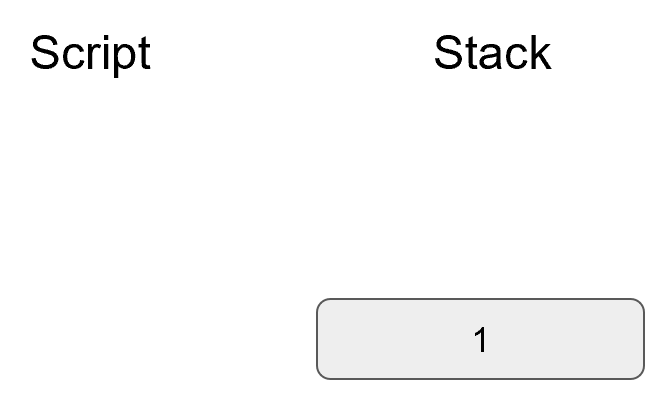

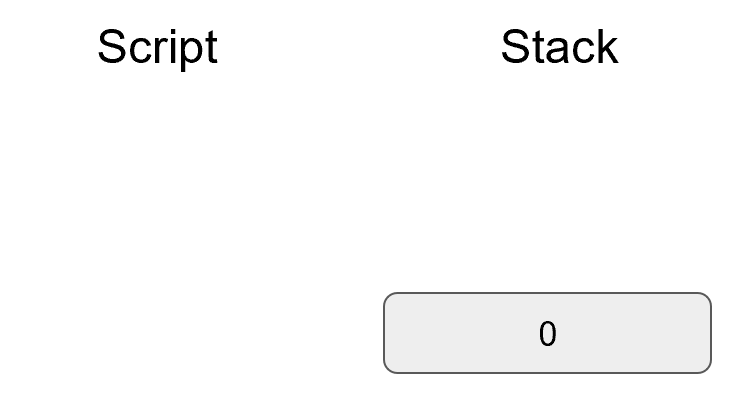

To whit, here are the steps:

We are given (r, s) as the signature, z as the hash of the thing being signed and P, the public key (or public point) of the signer.

We calculate u = z/s, v = r/s

We calculate uG + vP = R

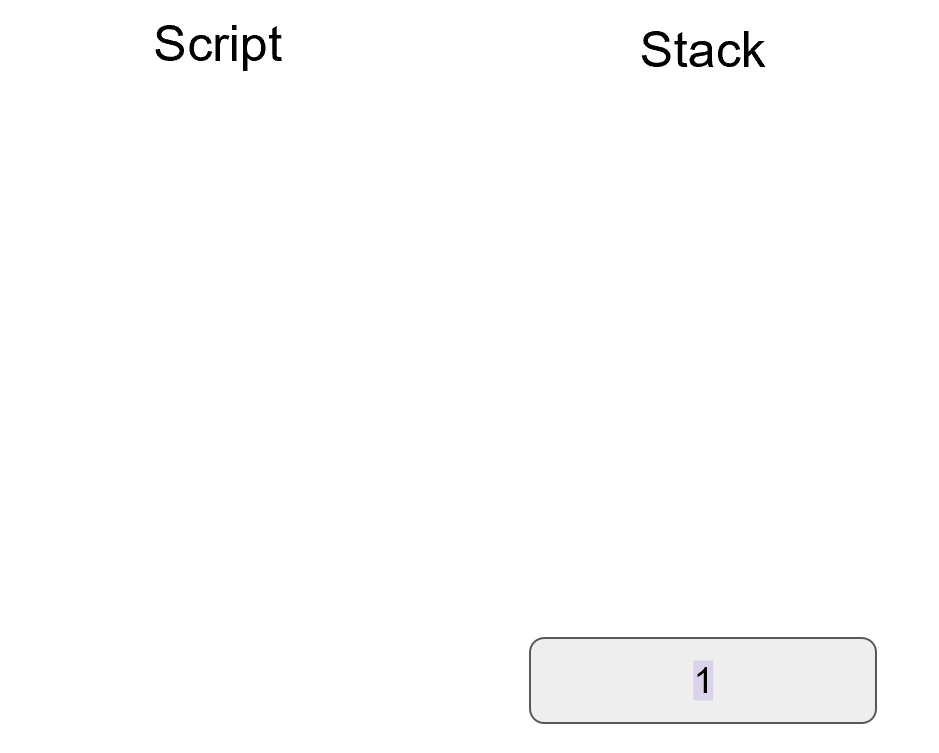

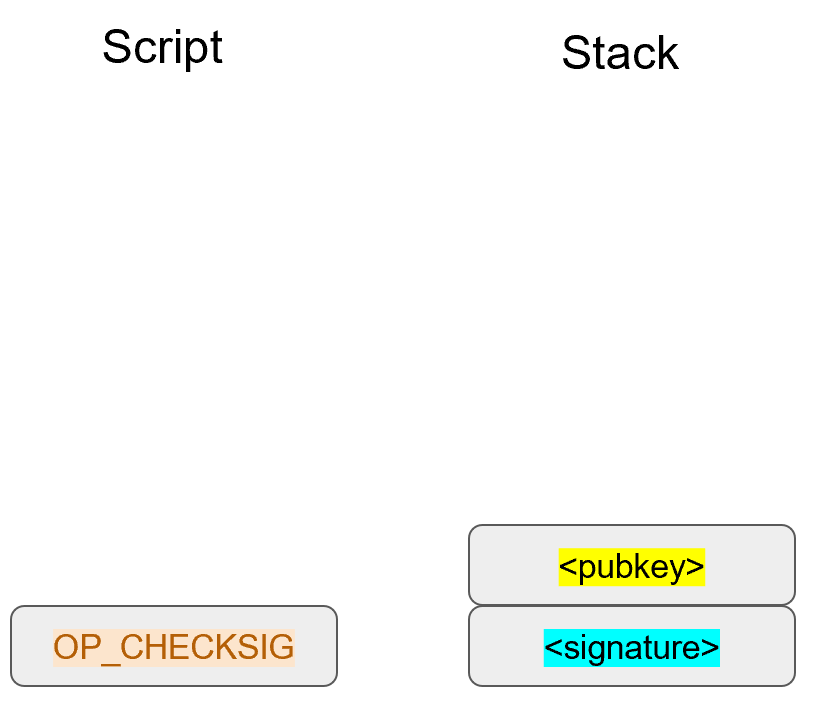

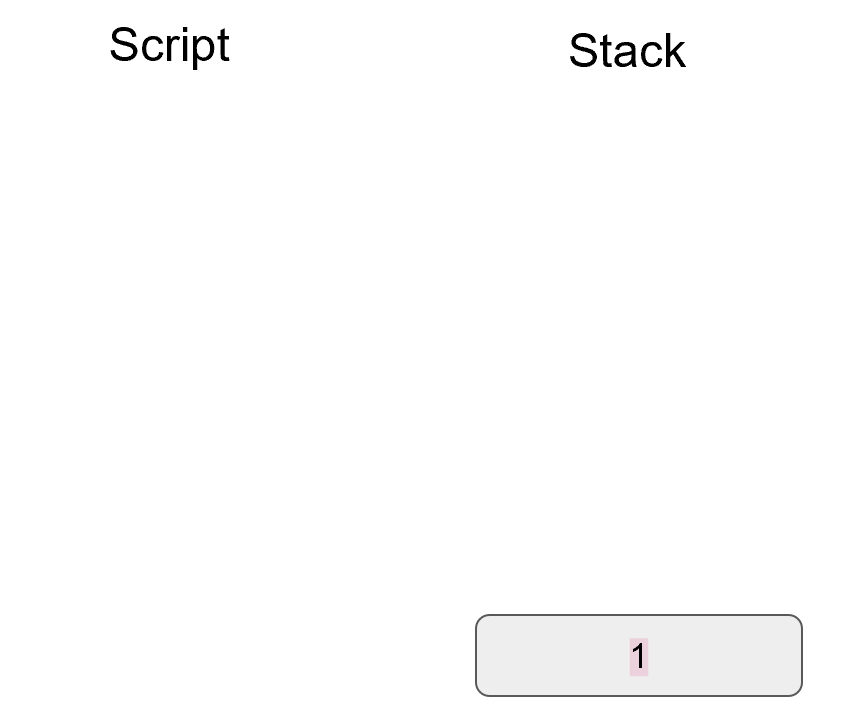

If R’s x coordinate equals r, the signature is valid.

The calculation of z requires two rounds of sha256, or hash256.

You may be wondering why there are two rounds when only 1 is necessary to get a 256-bit number.

The reason is for security.

There is a well-known hash collision attack on sha1 called a birthday attack which makes finding collisions much easier. Google found a sha1 collision using some modifications of a birthday attack and a lot of other things in 2017 (https://security.googleblog.com/2017/02/announcing-first-sha1-collision.html). Using sha1 twice, or double-sha1 is the way to defeat slow down some forms of this attack.

Two rounds of sha256 don’t necessarily prevent all possible attacks, but doing two rounds is a defense against some potential weaknesses.

We can now verify a signature using some of the primitives that we have.

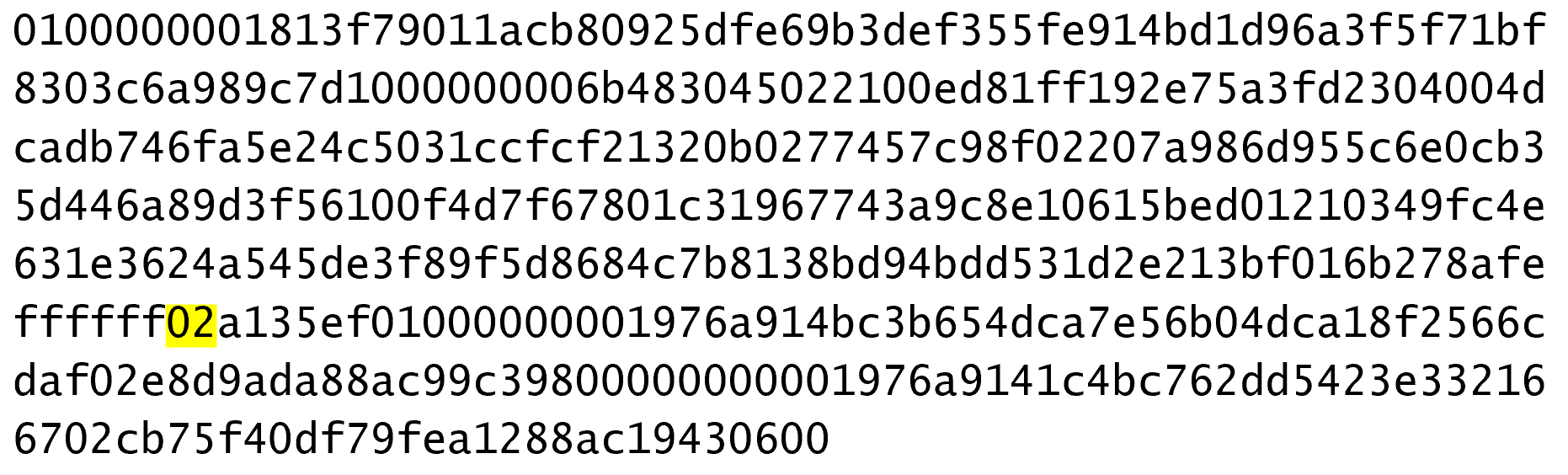

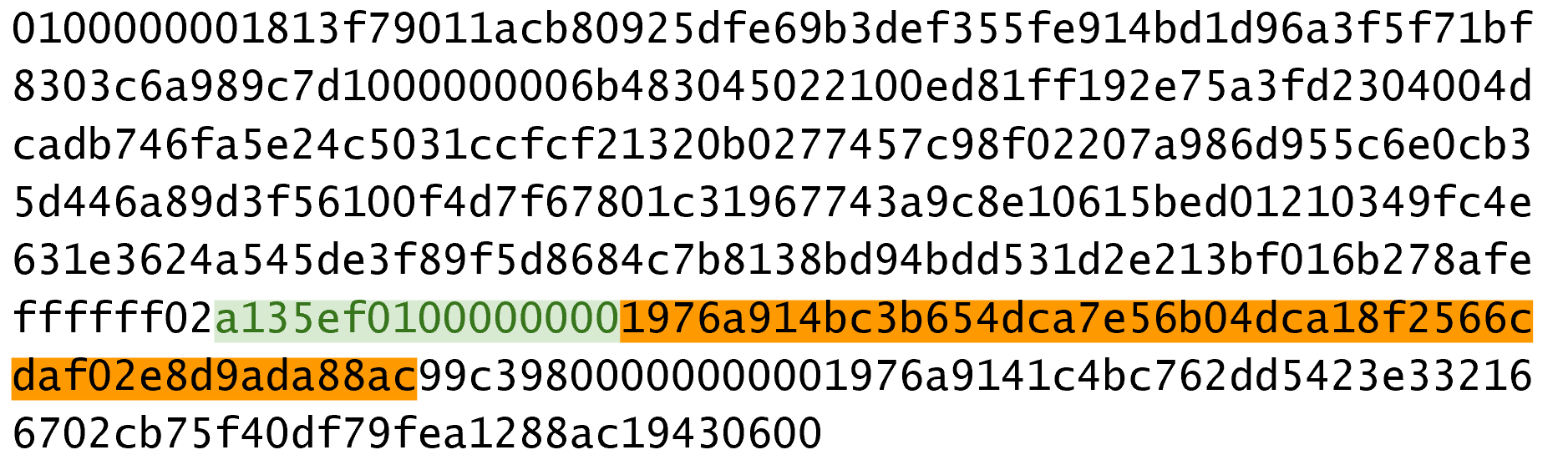

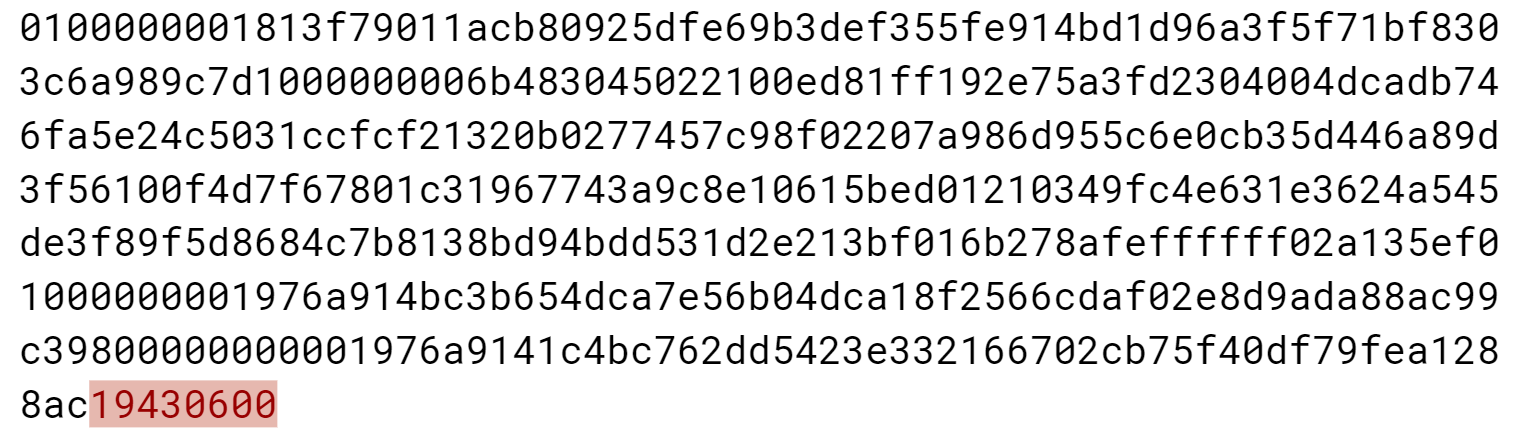

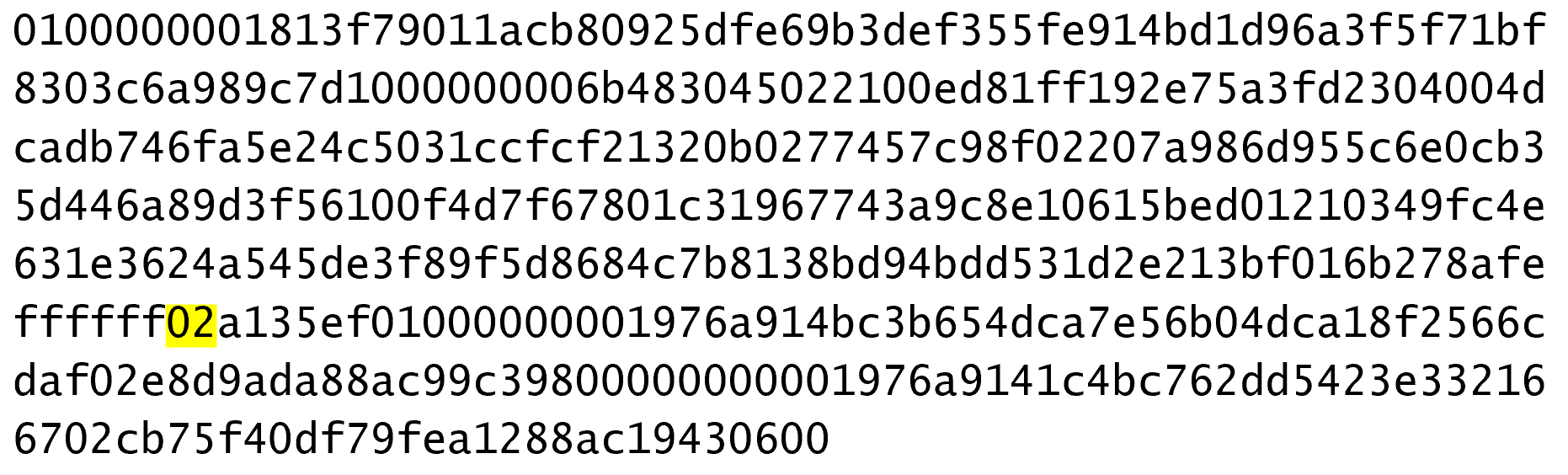

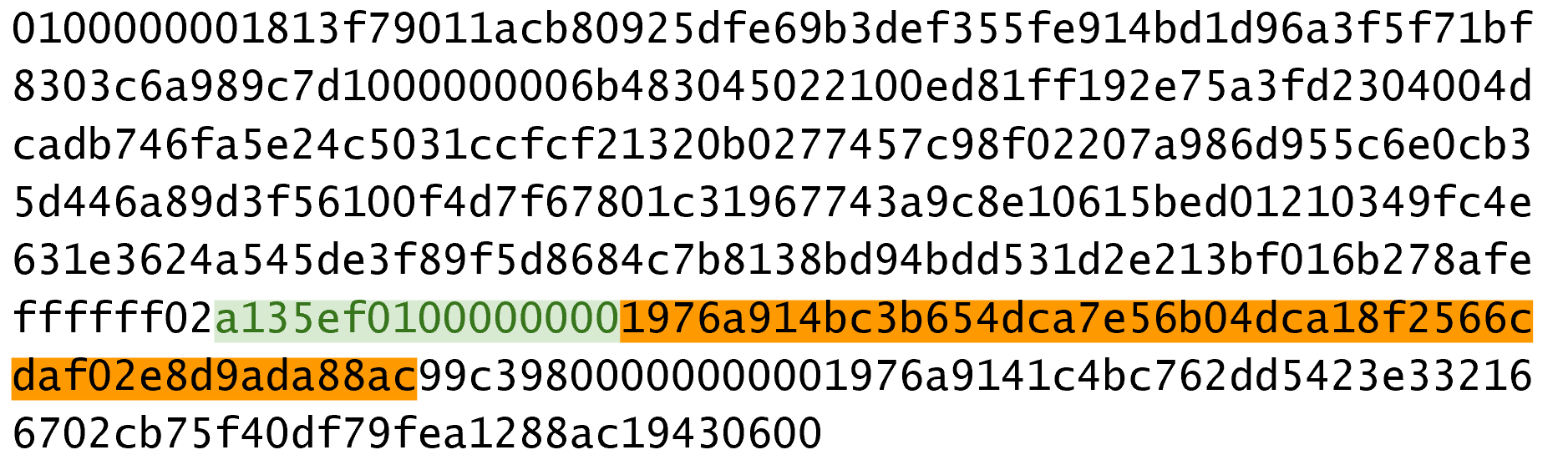

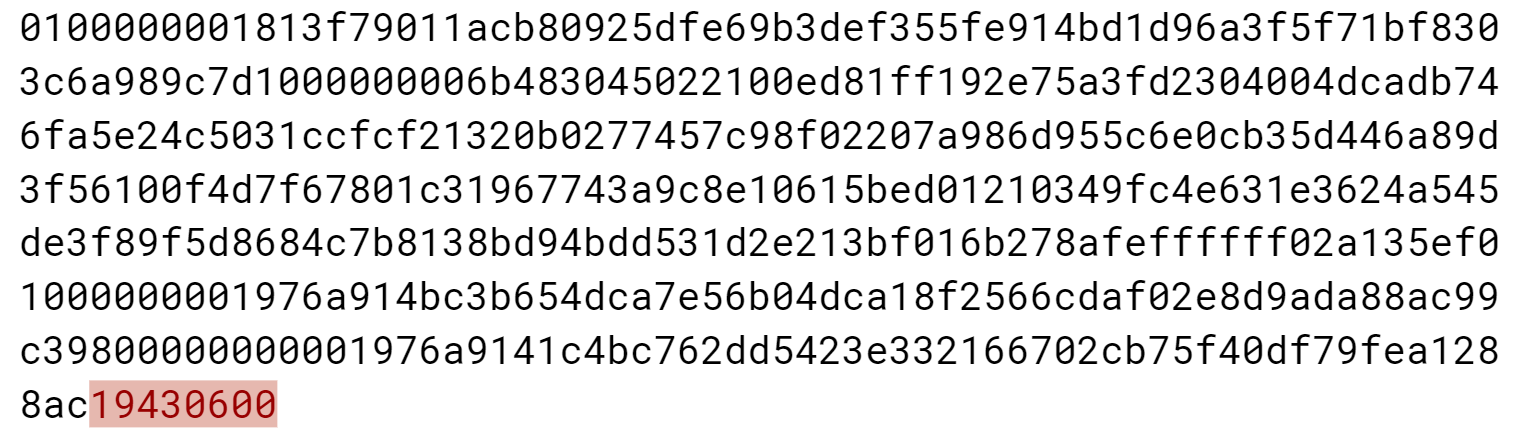

>>>fromeccimportS256Point,G,N>>>z=0xbc62d4b80d9e36da29c16c5d4d9f11731f36052c72401a76c23c0fb5a9b74423>>>r=0x37206a0610995c58074999cb9767b87af4c4978db68c06e8e6e81d282047a7c6>>>s=0x8ca63759c1157ebeaec0d03cecca119fc9a75bf8e6d0fa65c841c8e2738cdaec>>>px=0x04519fac3d910ca7e7138f7013706f619fa8f033e6ec6e09370ea38cee6a7574>>>py=0x82b51eab8c27c66e26c858a079bcdf4f1ada34cec420cafc7eac1a42216fb6c4>>>point=S256Point(px,py)>>>s_inv=pow(s,N-2,N)>>>u=z*s_inv%N>>>v=r*s_inv%N>>>((u*G+v*point).x.num==r)True

Verify whether these signatures are valid:

P = (0x887387e452b8eacc4acfde10d9aaf7f6d9a0f975aabb10d006e4da568744d06c,

0x61de6d95231cd89026e286df3b6ae4a894a3378e393e93a0f45b666329a0ae34)

# signature 1

z = 0xec208baa0fc1c19f708a9ca96fdeff3ac3f230bb4a7ba4aede4942ad003c0f60

r = 0xac8d1c87e51d0d441be8b3dd5b05c8795b48875dffe00b7ffcfac23010d3a395

s = 0x68342ceff8935ededd102dd876ffd6ba72d6a427a3edb13d26eb0781cb423c4

# signature 2

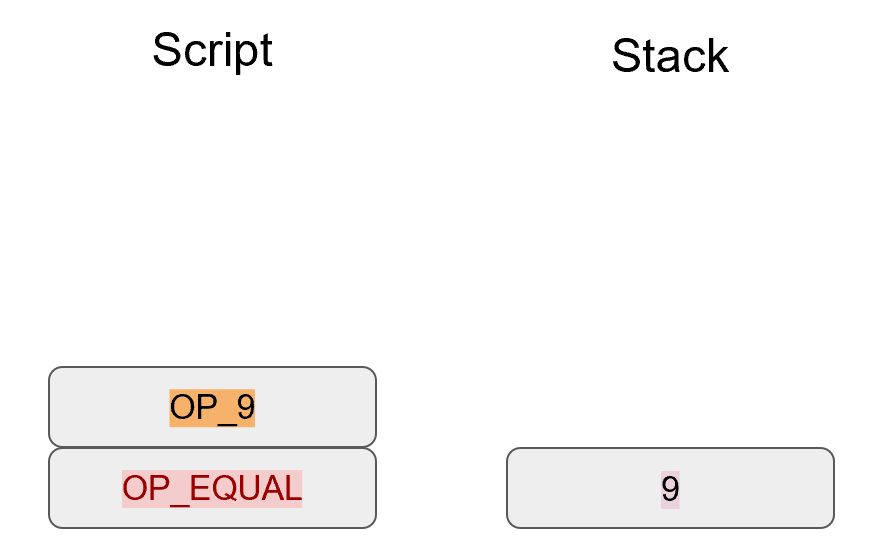

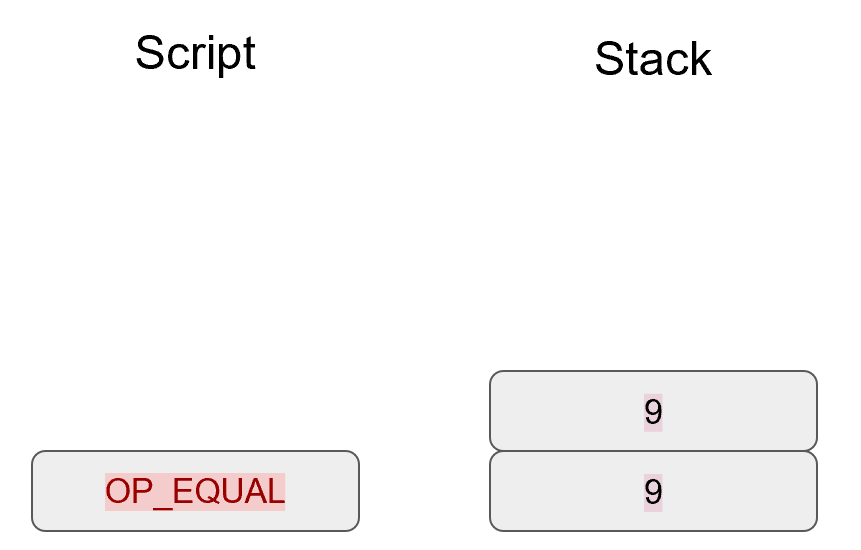

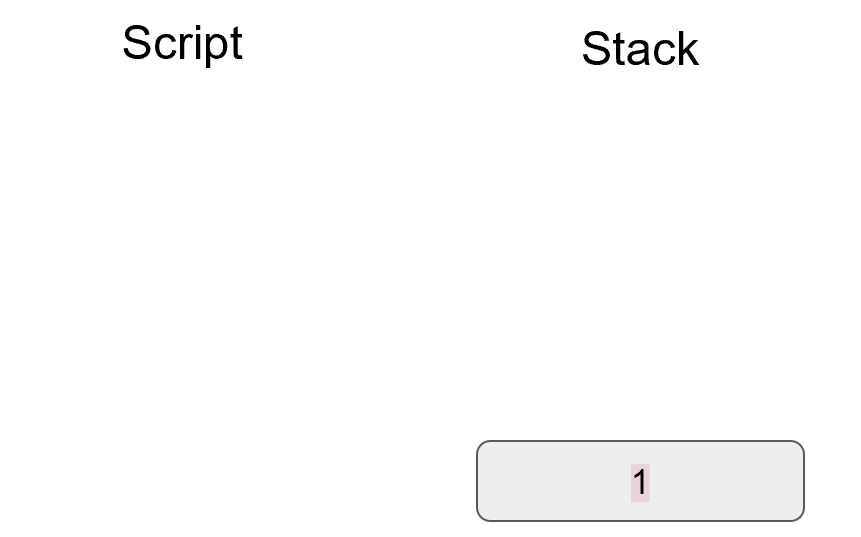

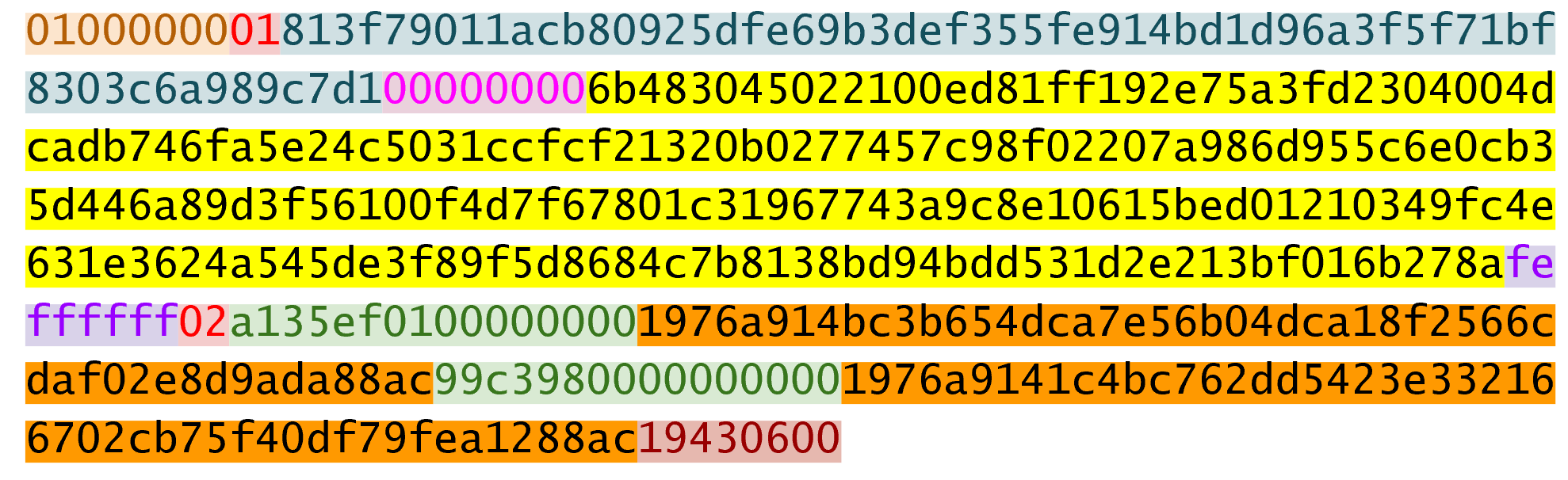

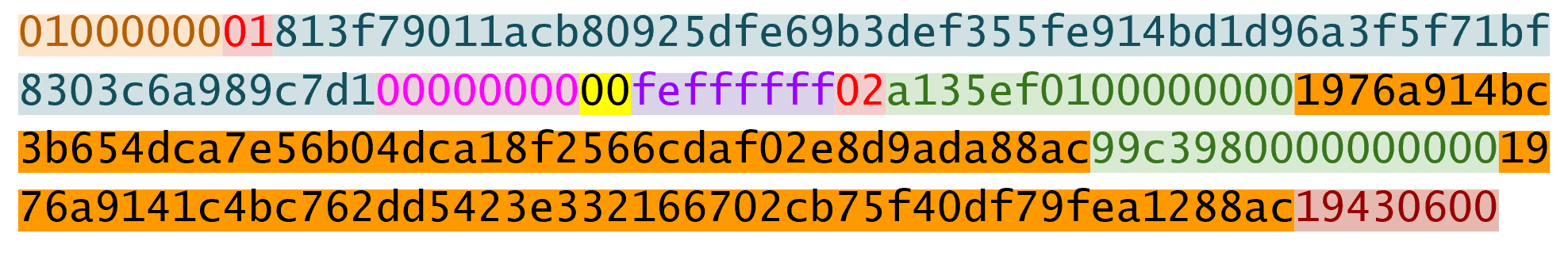

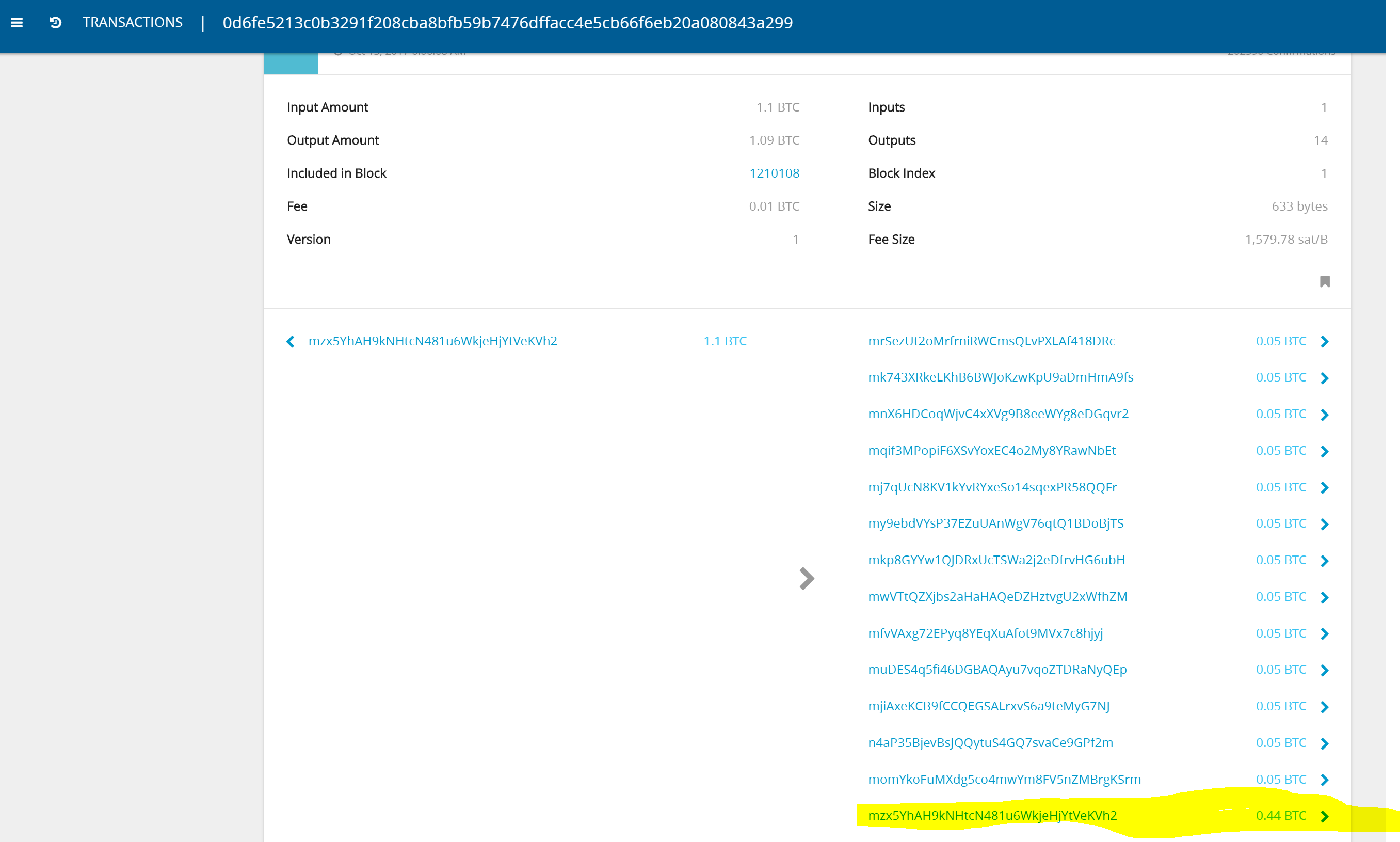

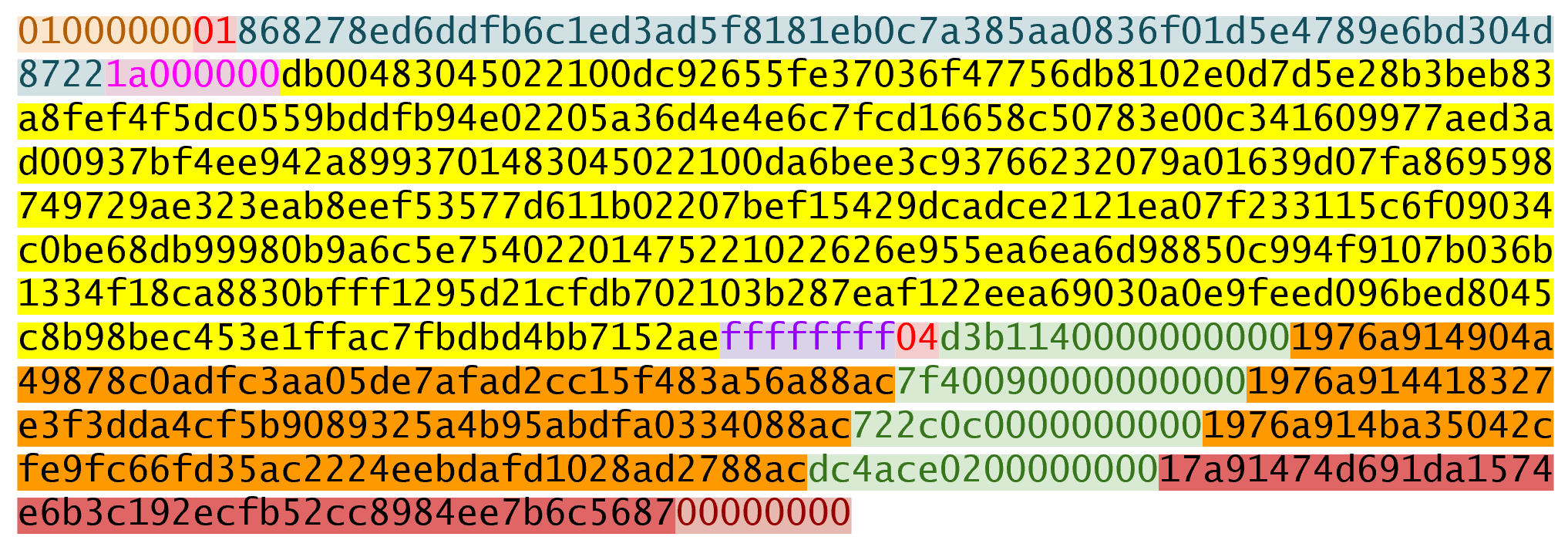

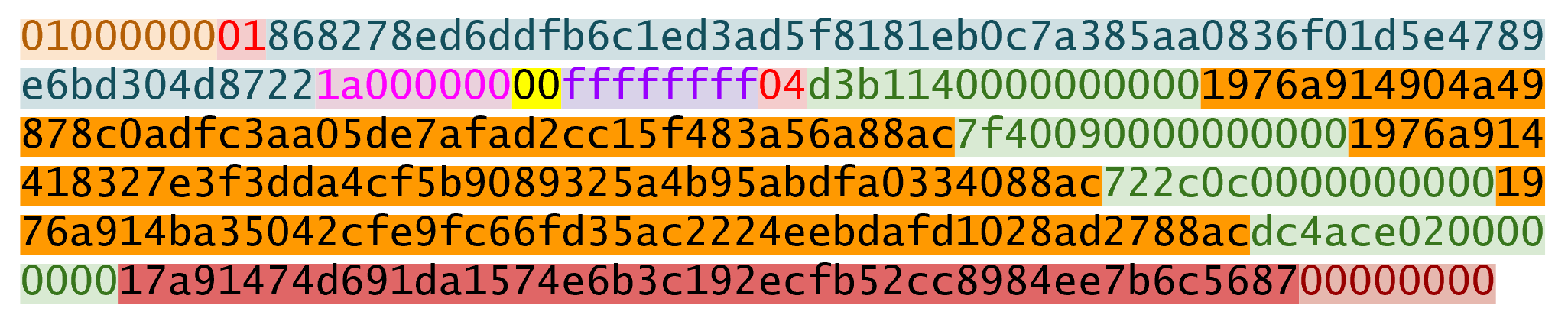

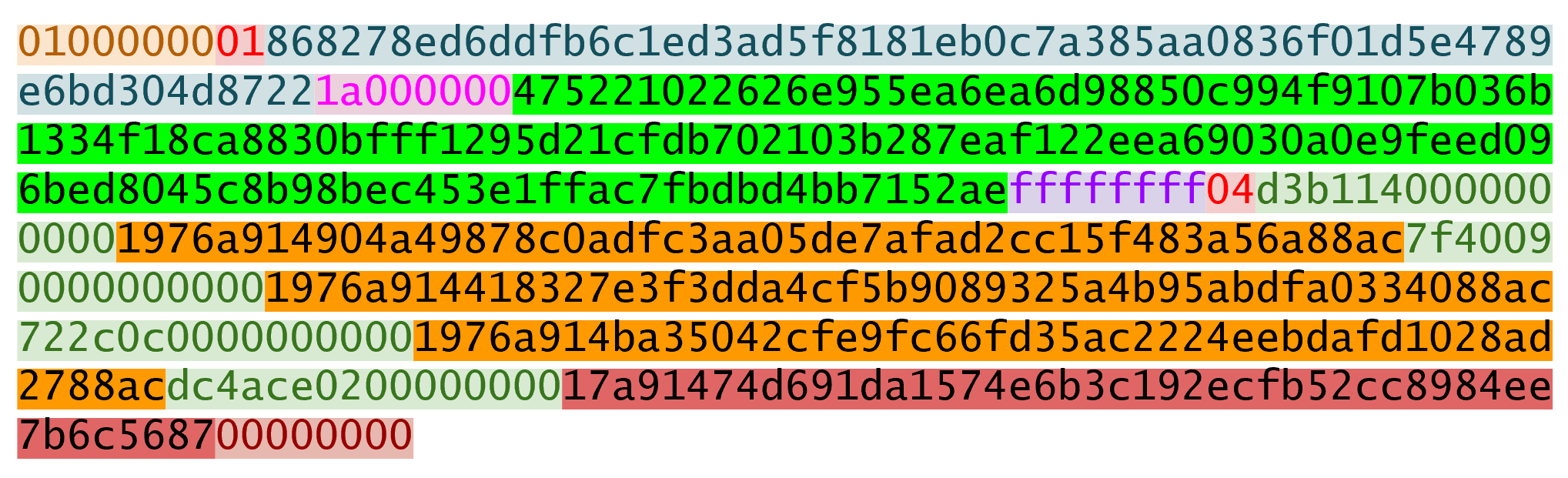

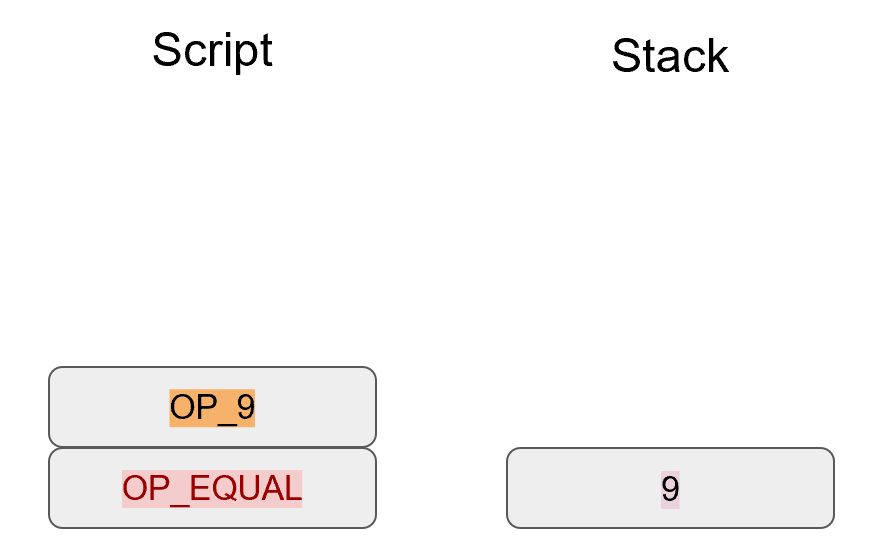

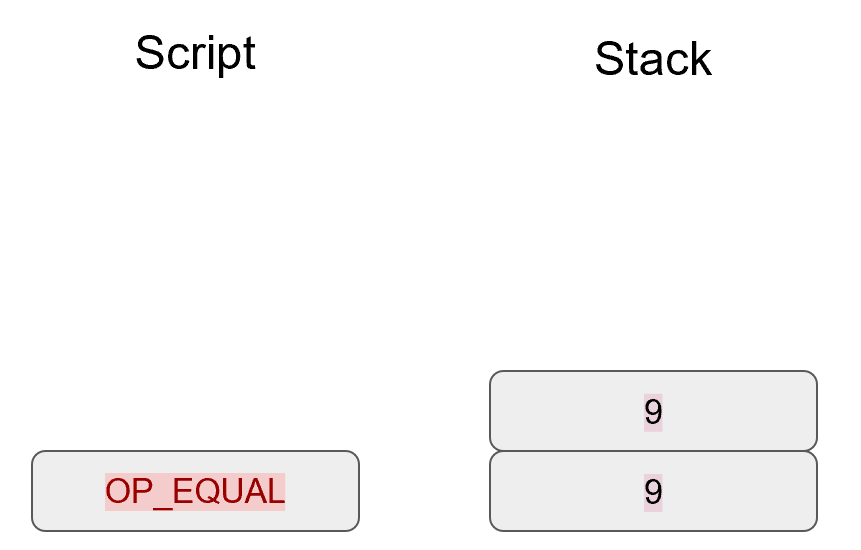

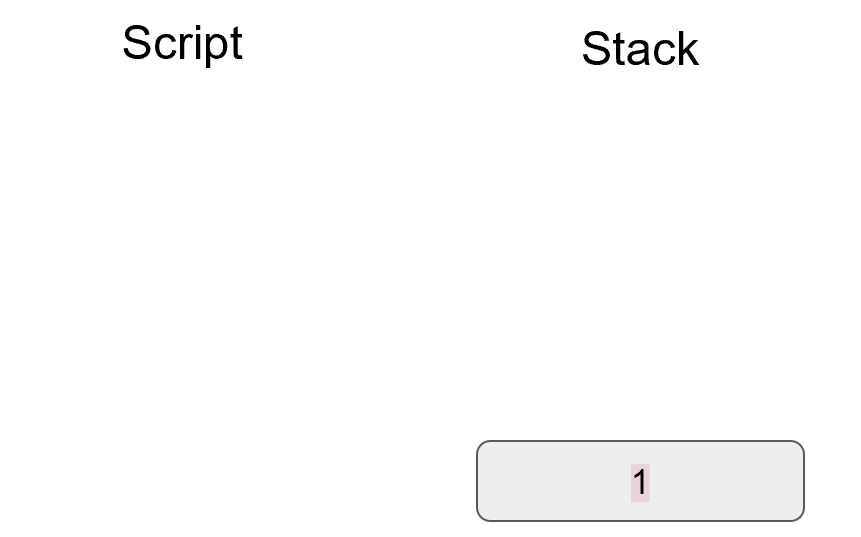

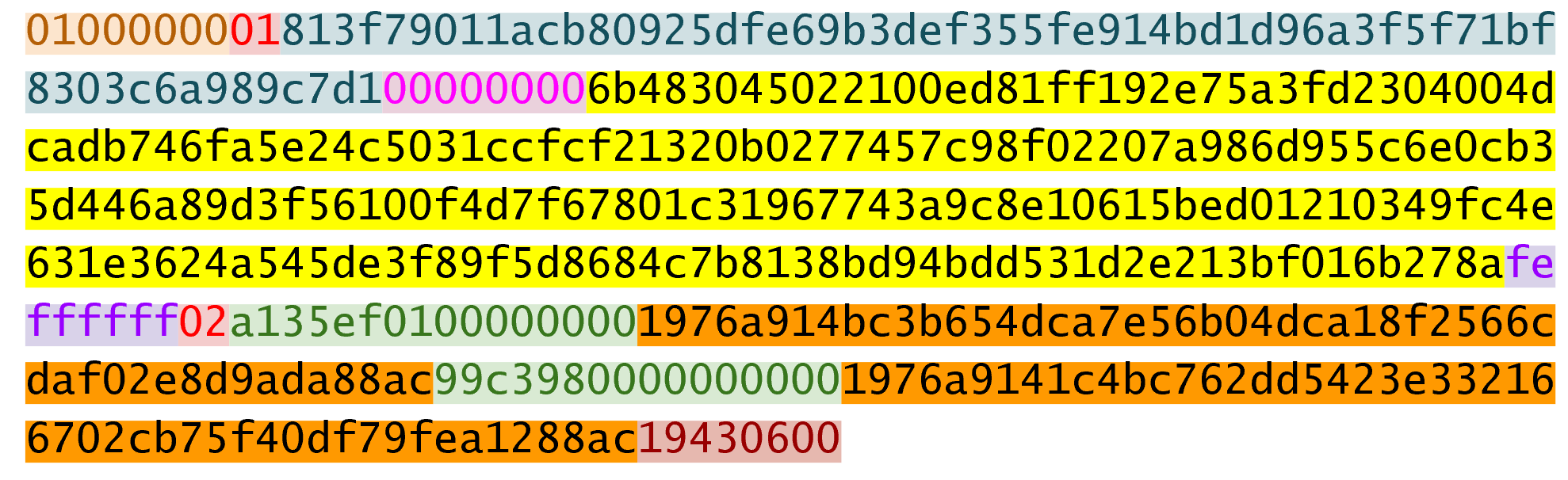

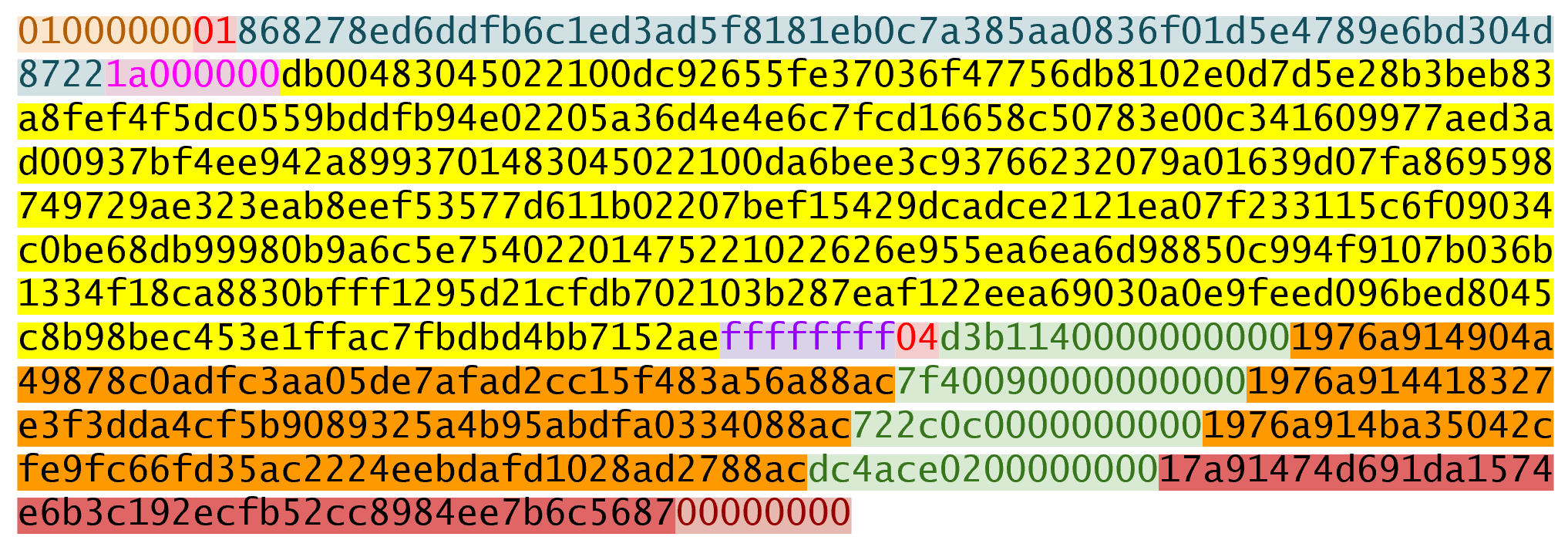

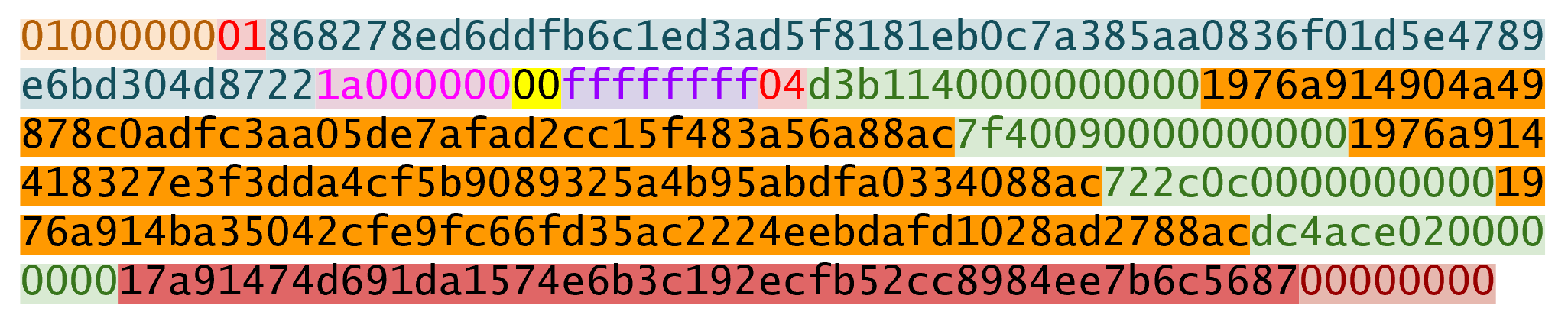

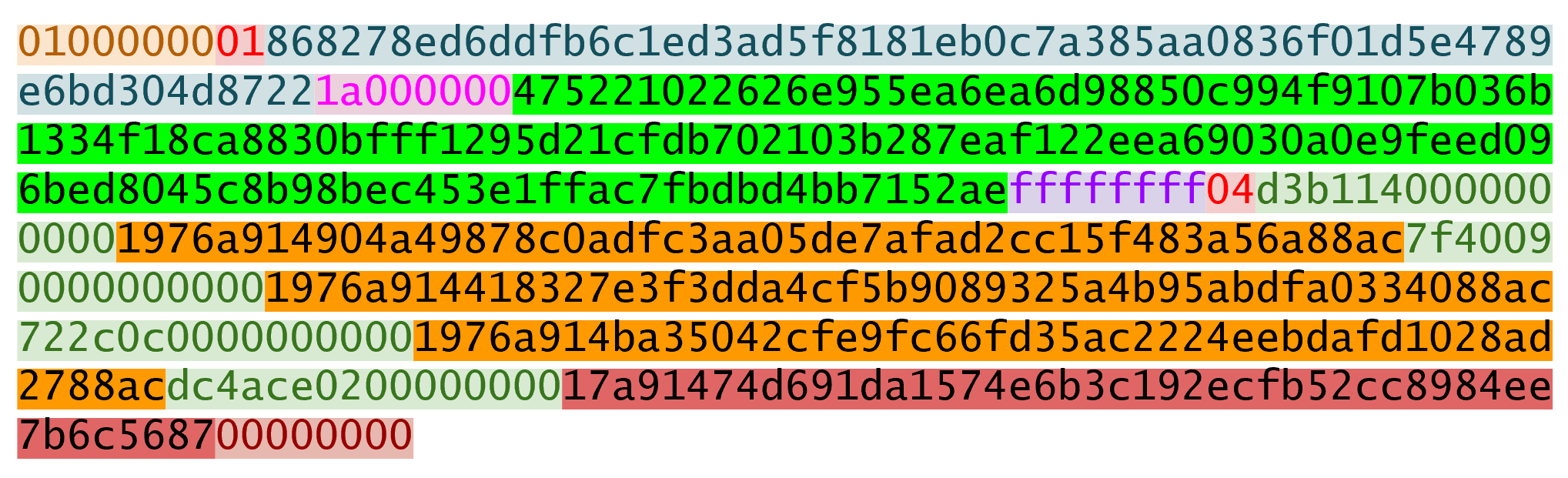

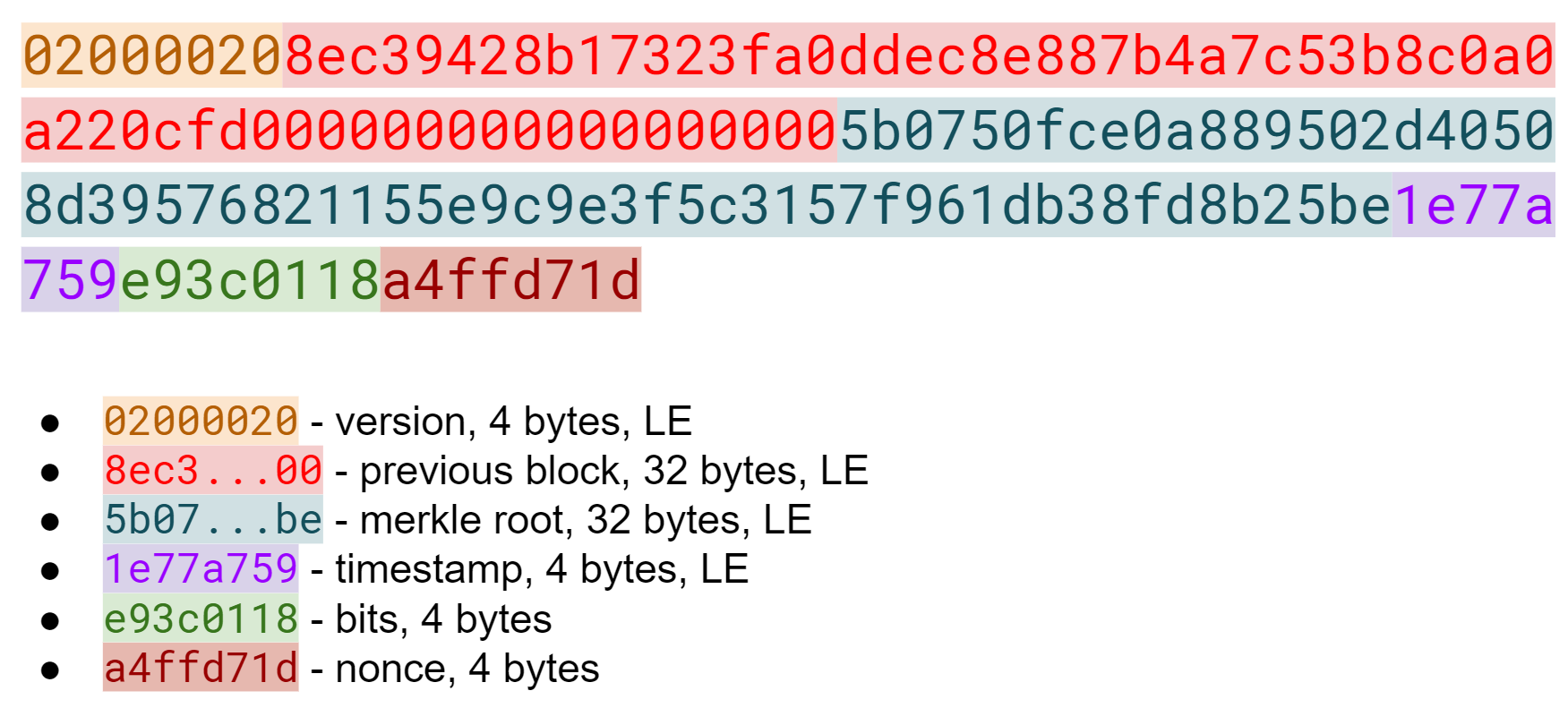

z = 0x7c076ff316692a3d7eb3c3bb0f8b1488cf72e1afcd929e29307032997a838a3d