First Edition

Fundamentals, Implementation, and Operation of Streaming Applications

Copyright © 2019 Fabian Hueske, Vasiliki Kalavri. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://oreilly.com/safari). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or corporate@oreilly.com.

See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=XXXXXXXXXXXXX for release details.

The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Stream Processing with Apache Flink, the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc.

While the publisher and the authors have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the authors disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open source licenses or the intellectual property rights of others, it is your responsibility to ensure that your use thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights.

9781491974223

[???]

Apache Flink is a distributed stream processor with intuitive and expressive APIs to implement stateful stream processing applications. It efficiently runs such applications at large scale in a fault-tolerant manner. Flink joined the Apache Software Foundation as an incubating project in April 2014 and became a top-level project in January 2015. Since its beginning, Flink has a very active and continuously growing community of users and contributors. Until today, more than 350 individuals have contributed to Flink and it has evolved into one of the most sophisticated open source stream processing engines as proven by its widespread adoption. Flink powers large-scale business-critical applications in many companies and enterprises across different industries and around the globe.

Stream processing technology is being rapidly adopted by companies and enterprises of any size because it provides superior solutions for many established use cases but also facilitates novel applications, software architectures, and business opportunities. In this chapter we discuss why stateful stream processing is becoming so popular and assess its potential. We start reviewing conventional data processing application architectures and point out their limitations. Next, we introduce application designs based on stateful stream processing that exhibit many interesting characteristics and benefits over traditional approaches. We briefly discuss the evolution of open source stream processors and help you to run a first streaming application on a local Flink instance. Finally, we tell you what you will learn when reading this book.

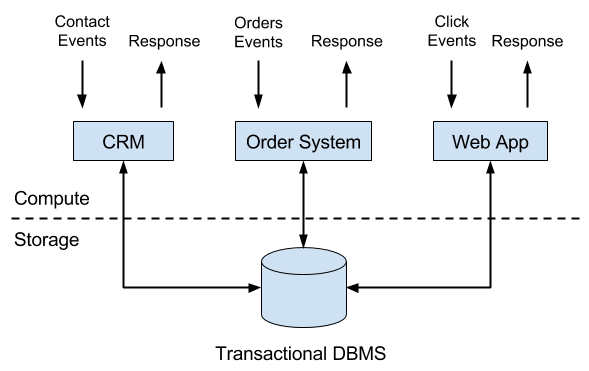

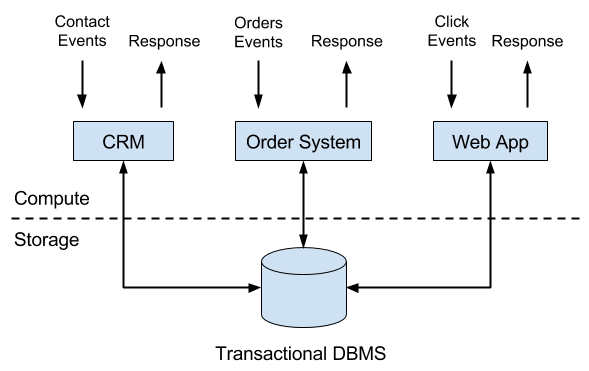

Companies employ many different applications to run their business, such as enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems, customer relationship management (CRM) software, or web-based applications. All of these systems are typically designed with separate tiers for data processing (the application itself) and data storage (a transactional database system) as shown in Figure 1-1.

The applications are usually connected to external services or face human users and continuously process incoming events such as orders, or mails, or clicks on a website. When an event is processed, an application reads its state or updates its state by running transactions against the remote database system. Typically, a database system serves multiple applications which often even access the same databases or tables.

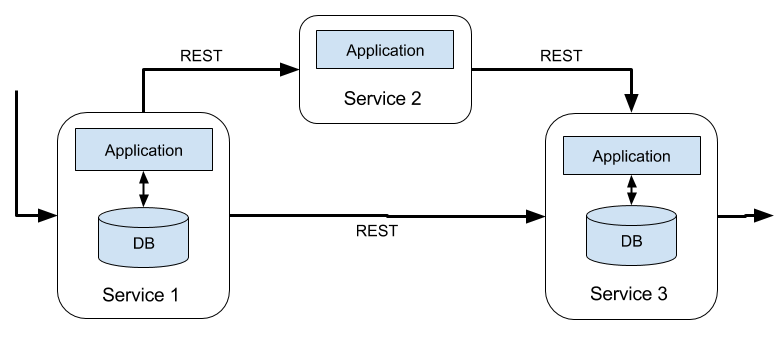

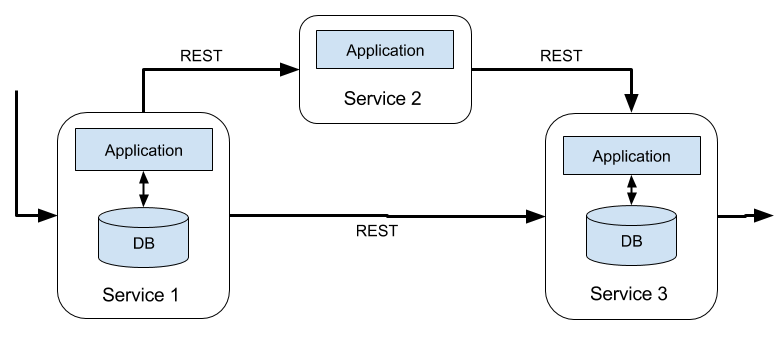

This design can cause problems when applications need to evolve or scale. Since, multiple applications might work on the same data representation or share the same infrastructure, changing the schema of a table or scaling a database system requires careful planning and a lot of effort. A recent approach to overcome the tight bundling of applications is the microservice design pattern. Microservices are designed as small, self-contained, and independent applications. They follow the UNIX philosophy of doing a single thing and doing it well. More complex applications are built by connecting several microservices with each other that only communicate over standardized interfaces such as RESTful HTTP connections. Because microservices are strictly decoupled from each other and only communicate over well defined interfaces, each microservice can be implemented with a custom technology stack including programming language, libraries, and data stores. Microservices and all required software and services are typically bundled and deployed in independent containers. Figure 1-2 depicts a microservice architecture.

The data that is stored in the various transactional database systems of a company can provide valuable insights about various aspects of the company’s business. For example, the data of an order processing system can be analyzed to obtain sales growth over time, to identify reasons for delayed shipments, or to predict future sales in order to adjust the inventory. However, transactional data is often distributed across several disconnected database systems and becomes more valuable when it can be jointly analyzed. Moreover, it is often required to transform the data into a common format.

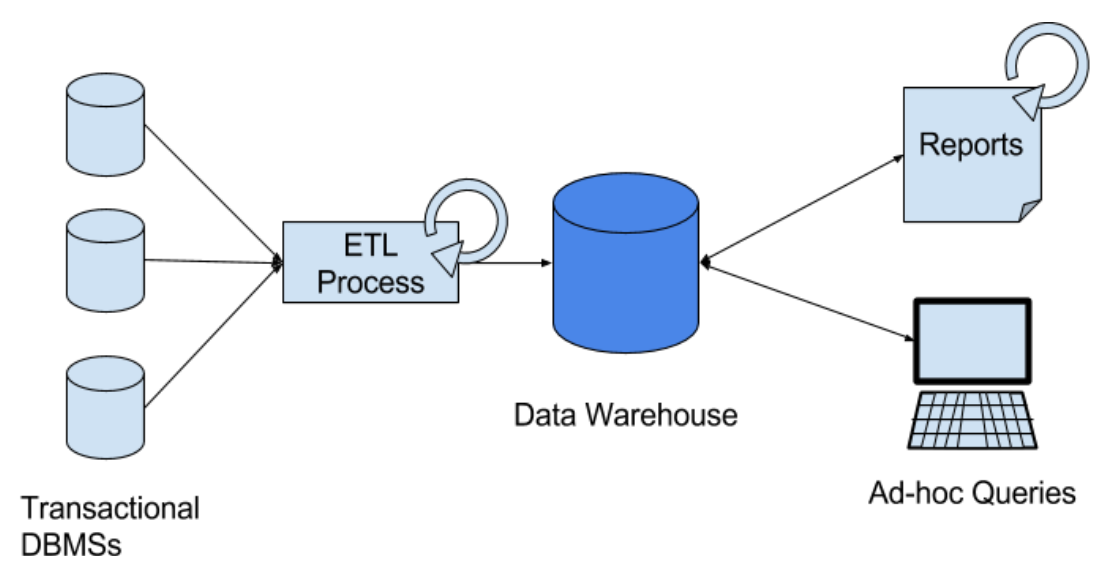

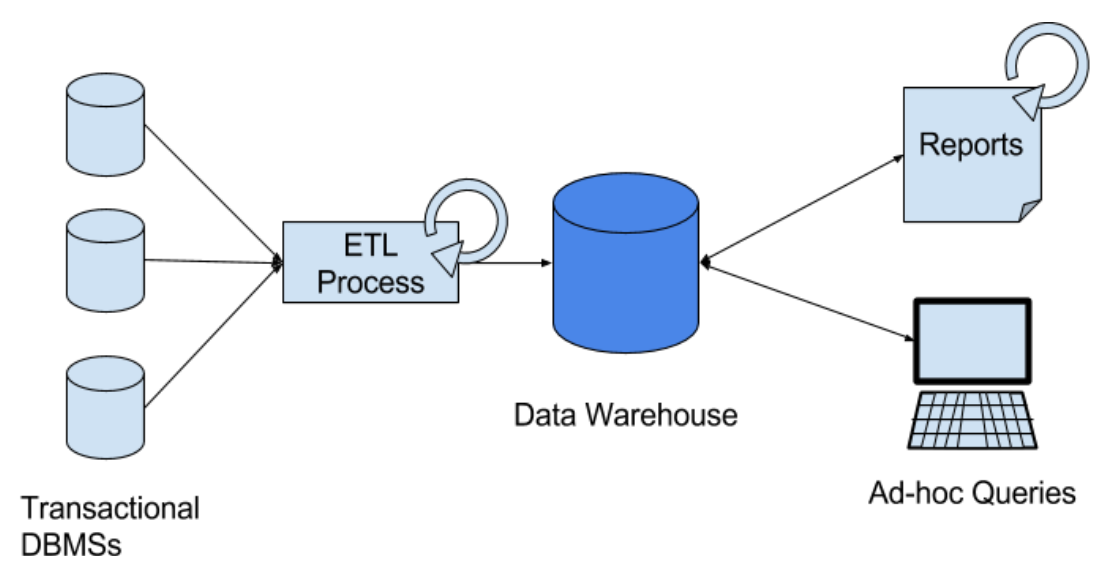

Instead of running analytical queries directly on the transactional databases, a common component in IT systems is a data warehouse. A data warehouse is a specialized database system for analytical query workloads. In order to populate a data warehouse, the data managed by the transactional database systems needs to be copied to it. The process of copying data to the data warehouse is called extract-transform-load (ETL). An ETL process extracts data from a transactional database, transforms it into a common representation which might include validation, value normalization, encoding, de-duplication, and schema transformation, and finally loads it into the analytical database. ETL processes can be quite complex and often require technically sophisticated solutions to meet performance requirements. In order to keep the data of the data warehouse up-to-date, ETL processes need to run periodically.

Once the data has been imported into the data warehouse it can be queried and analyzed. Typically, there are two classes of queries executed on a data warehouse. The first type are periodic report queries that compute business relevant statistics such as revenue, user growth, or production output. These metrics are assembled into reports that help to assess the situation of the business. The second type are ad-hoc queries that aim to provide answers to specific questions and support business-critical decisions. Both kinds of queries are executed by a data warehouse in a batch processing fashion, i.e., the data input of a query is fully available and the query terminates after it returned the computed result. The architecture is depicted in Figure 1-3.

Until the rise of Apache Hadoop, specialized analytical database systems and data warehouses were the predominant solutions for data analytics workloads. However, with the growing popularity of Hadoop, companies realized that a lot of valuable data was excluded from their data analytics process. Often, this data was either unstructured, i.e., not strictly following a relational schema, or too voluminous to be cost-effectively stored in a relational database system. Today, components of the Apache Hadoop ecosystem are integral parts in the IT infrastructures of many enterprises and companies. Instead of inserting all data into a relational database system, significant amounts of data, such as, log files, social media, or web click logs, are written into Hadoop’s distributed file system (HDFS) or other bulk data stores, like Apache HBase, which provide massive storage capacity at small cost. Data that resides in such storage systems is accessible to several SQL-on-Hadoop engines, as for example Apache Hive, Apache Drill, or Apache Impala. However, also with storage systems and execution engines of the Hadoop ecosystem the overall mode of operation of the infrastructure remains basically the same as the traditional data warehouse architecture, i.e., data is periodically extracted and loaded into to a data store and processed by periodic or ad-hoc queries in a batch fashion.

An important observation is that virtually all data is created as continuous streams of events. Think of user interactions on websites or in mobile apps, placements of orders, server logs, or sensor measurements; all of these data are streams of events. In fact, it is difficult to find examples of finite, complete data sets that are generated all at once. Stateful stream processing is an application design pattern for processing unbounded streams of events and is applicable to many different use cases in the IT infrastructure of a company. Before we discuss its use cases, we briefly explain what stateful stream processing is and how it works.

Any application that processes a stream of events and does not just perform trivial record-at-a-time transformations needs to be stateful, i.e., have the ability to store and access intermediate data. When an application receives an event, it can perform arbitrary computations that involve reading data from or writing data to the state. In principle, state can be stored and accessed in many different places including program variables, local files, or embedded or external databases.

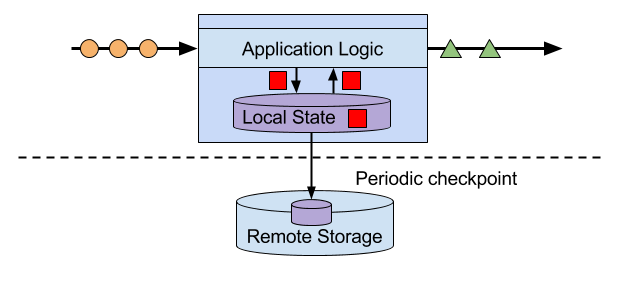

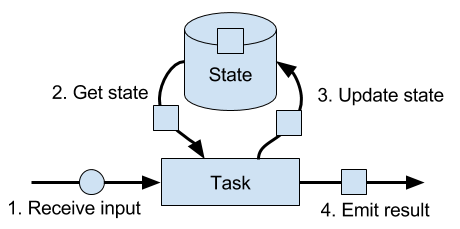

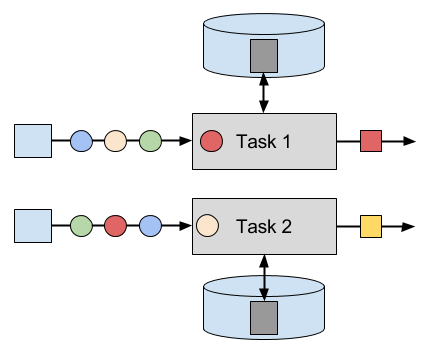

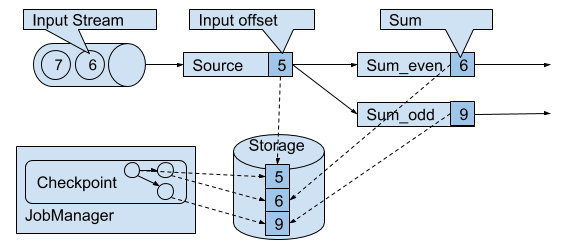

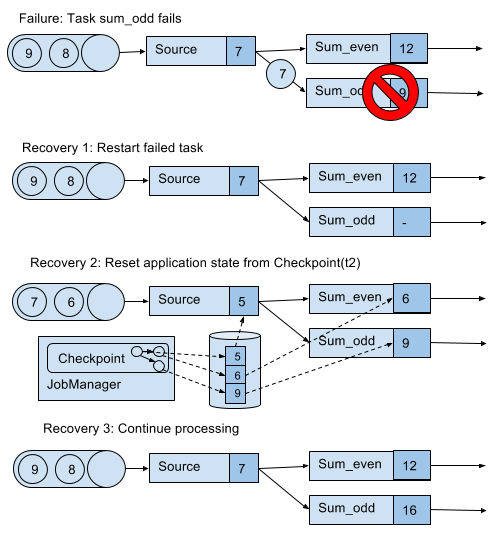

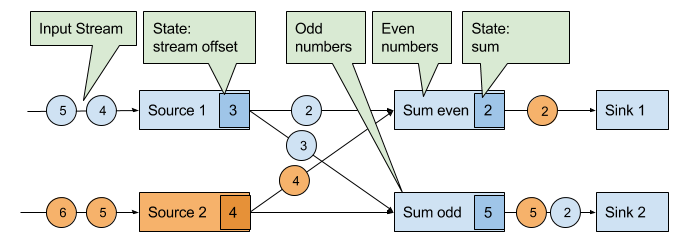

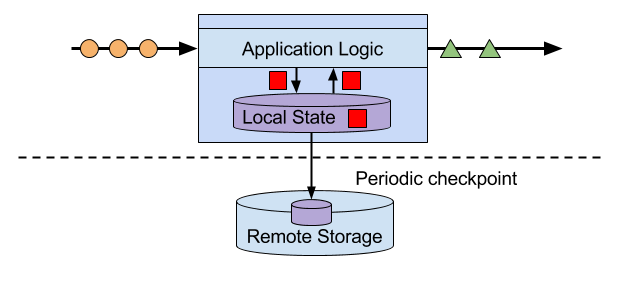

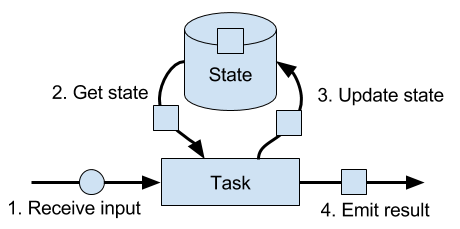

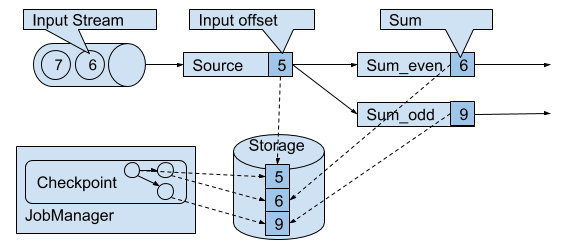

Apache Flink stores application state locally in memory or in an embedded database and not in a remote database. Since Flink is a distributed system, the local state needs to be protected against failures to avoid data loss in case of application or machine failures. Flink guarantees this by periodically writing a consistent checkpoint of the application state to a remote and durable storage. State, state consistency, and Flink’s checkpointing mechanism will be discussed in more detail in the following chapters. Figure 1-4 shows a stateful Flink application.

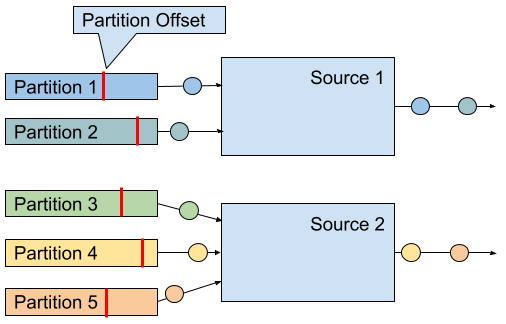

Stateful stream processing applications often ingest their incoming events from an event log. An event log stores and distributes event streams. Events are written to a durable, append-only log which means that the order of written events cannot be changed. A stream that is written to an event log can be read many times by the same or different consumers. Due to the append-only property of the log, events are always published to all consumers in exactly the same order. There are several event log systems available as open source software, Apache Kafka being the most popular, or as integrated services offered by cloud computing providers.

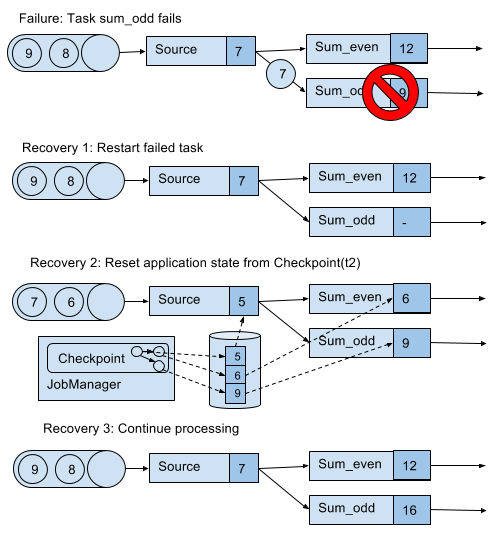

Connecting a stateful streaming application running on Flink and an event log is interesting for multiple reasons. In this architecture the event log acts as a source of truth because it persists the input events and can replay them in an deterministic order. In case of a failure, Flink restores a stateful streaming application by recovering its state from a previously taken checkpoint and resets the read position on the event log.The application will replay (and fast forward) the input events from the event log until it reaches the tail of the stream. This technique is used to recover from failures but can also be leveraged to update an application, fix bugs and repair previously emitted results, migrate an application to a different cluster, or perform A/B tests with different application versions.

As previously stated, stateful streaming processing is a versatile and flexible design pattern and can be used to address many different use cases. In the following we present three classes of applications that are commonly implemented using stateful stream processing, 1) event-driven applications, 2) data pipeline applications, and 3) data analytics applications and give examples of real-world applications. We describe these classes as distinct patterns to emphasize the versatility of stateful stream processing. However, most real-world applications combine characteristics of more than one class which again shows the flexibility of this application design pattern.

Event-driven applications are stateful streaming applications that ingest event streams and apply business logic on the received events. Depending on the business logic, an event-driven application can trigger actions such as sending an alert or an email or write events to an outgoing event stream that is possibly consumed by another event-driven application.

Typical use cases for event-driven applications include

Real-time recommendations, e.g., for recommending products while customers browse on a retailer’s website,

Pattern detection or complex event processing (CEP), e.g., for fraud detection in credit card transactions, and

Anomaly detection, e.g., to detect attempts to intrude a computer network.

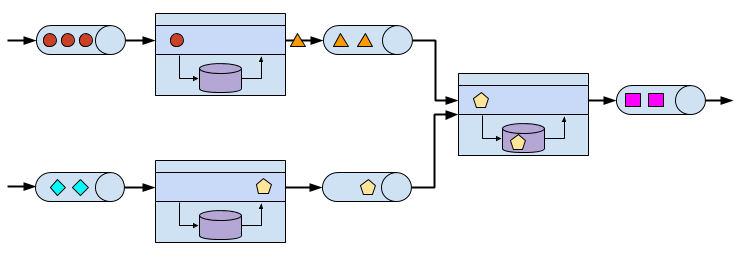

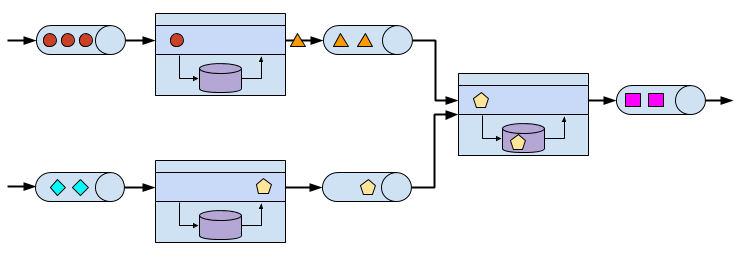

Event-driven applications are an evolution of the previously discussed microservices. They communicate via event logs instead of REST calls and hold application data as local state instead of writing it to and reading it from an external data store, such as a transactional database or key-value store. Figure 1-5 sketches a service architecture composed of event-driven streaming applications.

Event-driven applications are an interesting design pattern because they offer several benefits compared to the traditional architecture of separate storage and compute tiers or the popular microservice architectures. Local state accesses, i.e., reading from or writing to memory or local disk, provide very good performance compared to read and write queries against remote data stores. Scaling and fault-tolerance do not need special consideration because these aspects are handled by the stream processor. Finally, by leveraging an event log as input source the complete input of an application is reliably stored and can be deterministically replayed. This is very attractive especially in combination with Flink’s savepoint feature which can reset the state of an application to a previous consistent savepoint. By resetting the state of a (possibly modified) application and replaying the input, it is possible to fix a bug of the application and repair its effects, deploy new versions of an application without losing its state, or run what-if or A/B tests. We know of a company that decided to built the backend of a social network based on an event log and event-driven applications because of these features.

Event-driven applications have quite high requirements on the stream processor that runs them. The business logic is constrained by how much it can control state and time. This aspect depends on the APIs of the stream processor, what kinds of state primitives it provides, and on the quality of its support for event-time processing. Moreover, exactly-once state consistency and the ability to scale an application are fundamental requirements. Apache Flink checks all these boxes and is a very good choice to run event-driven applications.

Today’s IT architectures include many different data stores, such as relational and special-purpose database systems, event logs, distributed file systems, in-memory caches, and search indexes. All of these systems store data in different representations and data structures that provide the best performance for their specific purpose. Subsets of an organization’s data are stored in multiple of these systems. For example, information for a product that is offered in a webshop can be stored in a transactional database, a web cache, and a search index. Due to this replication of data, the data stores must be kept in sync.

The traditional approach of a periodic ETL job to move data between storage systems is typically not able to propagate updates fast enough. Instead a common approach is to write all changes into an event log that serves as source of truth. The event log publishes the changes to consumers that incorporate the updates into the affected data stores. Depending on the use case and data store, the updates need to be processed before they can be incorporated. For example they need to be normalized, joined or enriched with additional data, or pre-aggregated, i.e., transformations that are also commonly performed by ETL processes.

Ingesting, transforming, and inserting data with low latency is another common use case for stateful stream processing applications. We call this type of applications data pipelines. Additional requirements for data pipelines are the ability to process large amounts of data in short time, i.e., support for high throughput, and the capability to scale an application. A stream processor that operates data pipelines should also feature many source and sink connectors to read data from and write data to various storage systems and formats. Again, Flink provides all required features to successfully operate data pipelines and includes many connectors.

Previously in this chapter, we described the common architecture for data analytics pipelines. ETL jobs periodically import data into a data store and the data is processed by ad-hoc or scheduled queries. The fundamental mode of operation - batch processing - is the same regardless whether the architecture is based on a data warehouse or components of the Hadoop ecosystem. While the approach of periodically loading data into data analysis systems has been the state-of-the-art for many years, it suffers from a notable drawback.

Obviously, the periodic nature of the ETL jobs and reporting queries induce a considerable latency. Depending on the scheduling intervals it may take hours or days until a data point is included in a report. To some extent, the latency can be reduced by importing data into the data store with data pipeline applications. However, even with continuous ETL there will always be a certain delay until an event is processed by a query. In the past, analyzing data with a few hours or even days delay was often acceptable because a prompt reaction to new results or insights did not yield a significant advantage. However, this has dramatically changed in the last decade. The rapid digitalization and emergence of connected systems made it possible to collect much more data in real-time and immediately act on this data for example by adjusting to changing conditions or by personalizing user experiences. An online retailer is able to recommend products to users while they are browsing on the retailer’s website; mobile games can give virtual gifts to users to keep them in a game or offer in-game purchases at the right moment; manufacturers can monitor the behavior of machines and trigger maintenance actions to reduce production outages. All these use cases require collecting real-time data, analyzing it with low latency, and immediately reacting to the result. Traditional batch oriented architectures are not able to address such use cases.

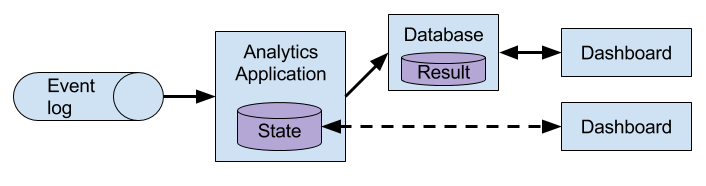

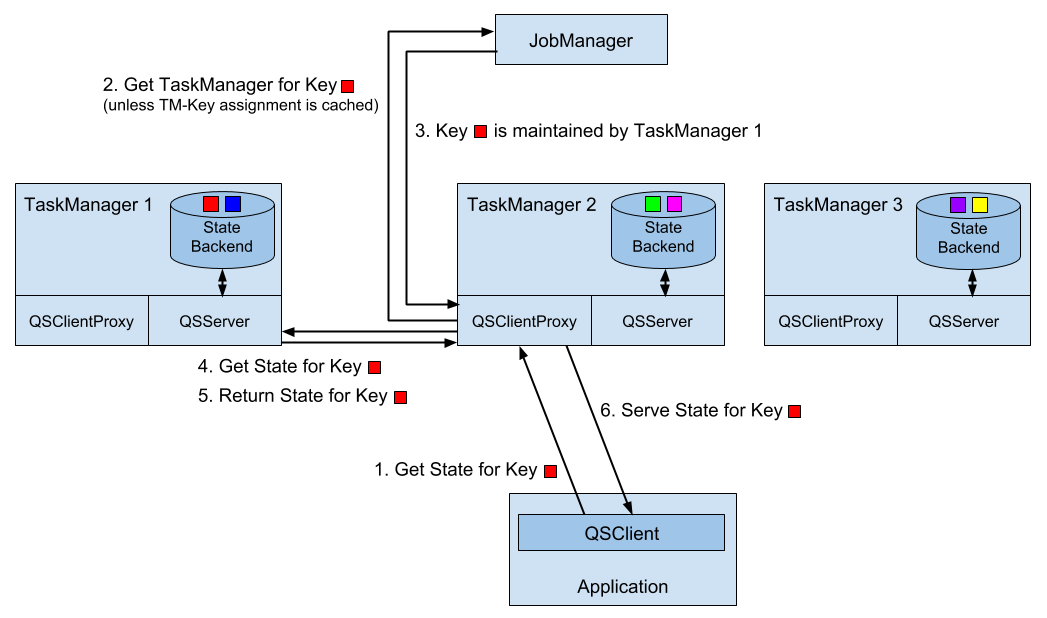

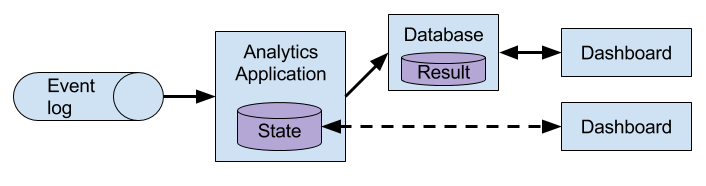

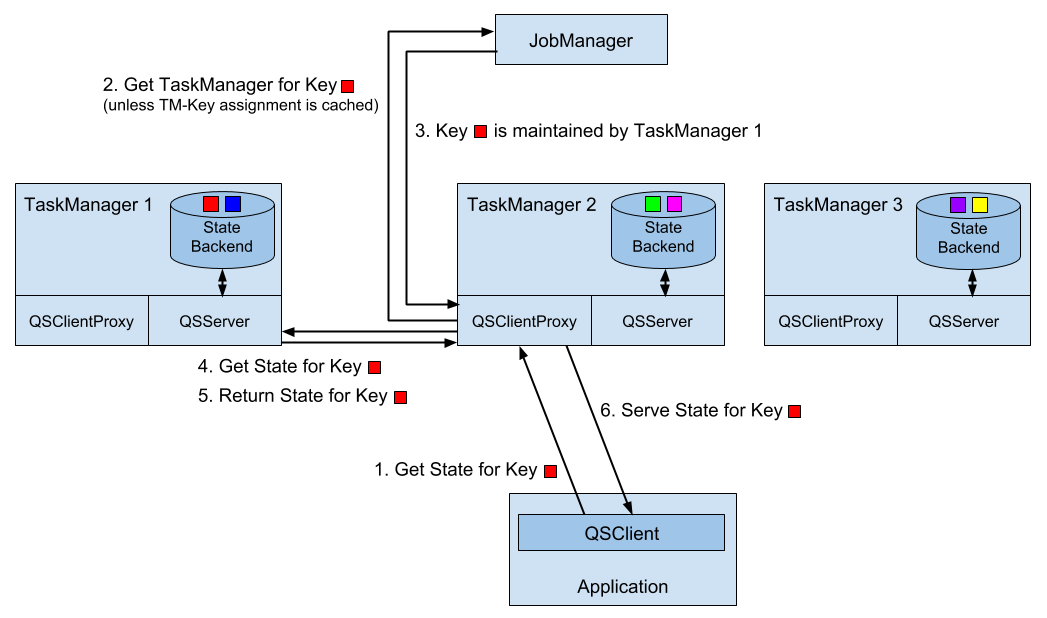

You are probably not surprised that stateful stream processing is the right technology to build low-latency analytics pipelines. Instead of waiting to be periodically triggered, a streaming analytics application continuously ingests streams of events and maintains an updating result by incorporating the latest events with low latency. This is similar to view maintenance techniques that database systems use to update materialized views. Typically, streaming applications store their result in an external data store that supports efficient updates, such as a database or key-value store. Alternatively, Flink provides a feature called queryable state which allows users to expose the state of an application as a key-lookup table and make it accessible for external applications. The live updated results of a streaming analytics applications can be used to power dashboard applications as shown in Figure 1-6.

Besides the much smaller time for an event to be incorporated into an analytics result, there is another, less obvious, advantage of streaming analytics applications. Traditional analytics pipelines consist of several individual components such as an ETL process, a storage system, and in case of a Hadoop-based environment also a data processor and scheduler to trigger jobs or queries. These components need to be carefully orchestrated and especially error handling and failure recovery can become challenging.

In contrast, a stream processor that runs a stateful streaming application takes care of all processing steps, including event ingestion, continuous computation including state maintenance, and updating the result. Moreover, the stream processor is responsible to recover from failures with exactly-once state consistency guarantees and should be capable of adjusting the parallelism of an application. Additional requirements to successfully support streaming analytics applications are support for event-time processing in order to produce correct and deterministic results and the ability to process large amounts of data in little time, i.e., high throughput. Flink offers good answers to all of these requirements.

Typical use cases for streaming analytics applications are

Monitoring the quality of cellphone networks.

Analyzing user behavior in mobile applications.

Ad-hoc analysis of live data in consumer technology.

Although not being covered in this book but certainly worth mentioning is that Flink also provides support for analytical SQL queries over streams. Multiple companies have built streaming analytics services based on Flink’s SQL support both for internal use or to publicly offer them to paying customers.

Data stream processing is not a novel technology. First research prototypes and commercial products date back to the late 1990s. However, the growing adoption of stream processing technology in the recent past is driven to a large extent by the availability of mature open source stream processors. Today, distributed open source stream processors power business-critical applications in many enterprises across different industries such as (online) retail, social media, telecommunication, gaming, and banking. Open source software is a major driver of this trend, mainly due to two reasons.

The Apache Software Foundation alone is the home of more than a dozen projects that are related to stream processing. New distributed stream processing projects are continuously entering the open source stage and are challenging the state-of-the-art with new features and capabilities. Often are features of these newcomers being adopted by more stream processors of earlier generations. Moreover, users of open source software request or contribute new features that are missing to support their use cases. This way, open source communities are constantly improving the capabilities of their projects and are pushing the technical boundaries of stream processing further. We will take a brief look into the past to see where open source stream processing came from and where it is today.

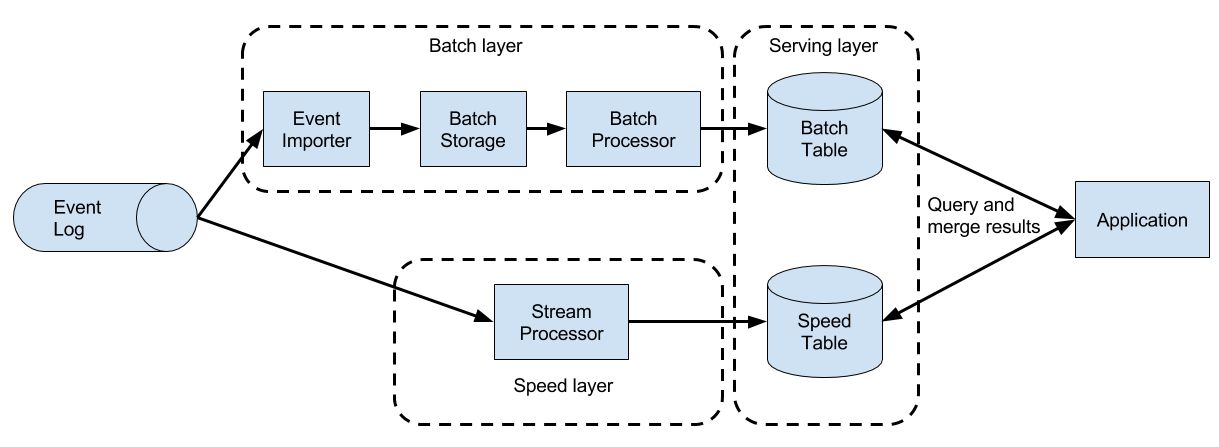

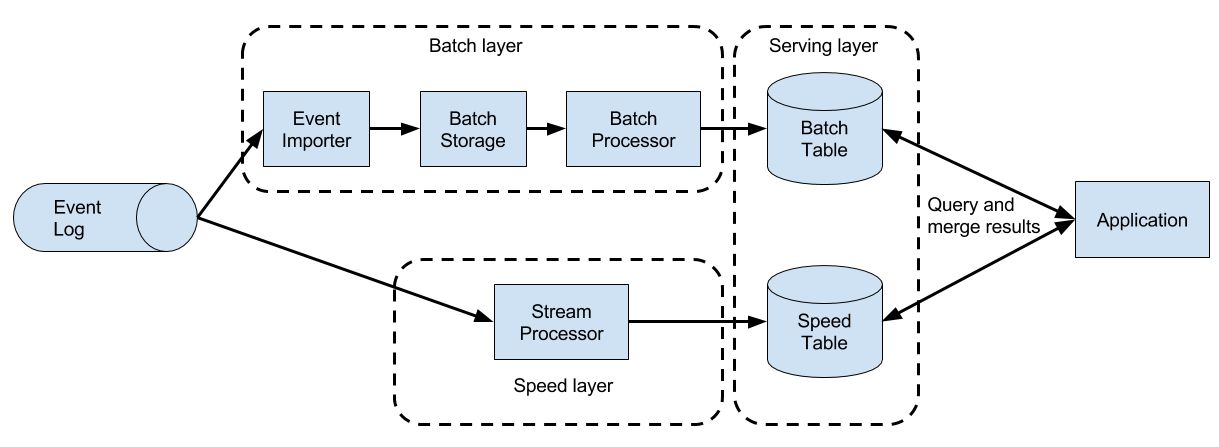

The first generation of distributed open source stream processors that got substantial adoption focused on event processing with millisecond latencies and provided guarantees that events would never be lost in case of a failure. These systems had rather low-level APIs and did not provide built-in support for accurate and consistent results of streaming applications because the results depended on the timing and order of arriving events. Moreover, even though events would not be lost in case of a failure, they could be processed more than once. In contrast to batch processors that guarantee accurate results, the first open source stream processors traded result accuracy for much better latency. The observation that data processing systems (at this point in time) could either provide fast or accurate results led to the design of the so-called Lambda architecture which is depicted in Figure 1-7.

The Lambda architecture augments the traditional periodic batch processing architecture with a Speed Layer that is powered by a low-latency stream processor. Data arriving to the Lambda architecture is ingested by the stream processor as well as written to a batch storage such as HDFS. The stream processor computes possibly inaccurate results in near real-time and writes the results into a speed table. The data written to the batch storage is periodically processed by a batch processor. The exact results are written into a batch table and the corresponding inaccurate results from the speed table are dropped. Applications consume the results from the Serving Layer by merging the most recent but only approximated results from the speed table and the older but accurate result from the batch table. The Lambda architecture aimed to improve the high result latency of the original batch analytics architecture. However, the approach had a few notable drawbacks. First of all, it requires two semantically equivalent implementations of the application logic for two separate processing systems with different APIs. Second, the latest results computed by the stream processor are not accurate but only approximated. Third, the Lambda architecture is hard to setup and maintain. A textbook setup consists of a stream processor, a batch processor, a speed store, a batch store, and tools to ingest data for the batch processor and scheduling batch jobs.

Improving on the first generation, the next generation of distributed open source stream processors provided better failure guarantees and ensured that in case of a failure each record contributes exactly once to the result. In addition, programming APIs evolved from rather low-level operator interfaces to high-level APIs with more built-in primitives. However, some improvements such as higher throughput and better failure guarantees came at the cost of increasing processing latencies from milliseconds to seconds. Moreover, results were still dependent on timing and order of arriving events, i.e., the results did not depend solely on the data but also on external conditions such as the hardware utilization.

The third generation of distributed open source stream processors fixed the dependency of results on the timing and order of arriving events. In combination with exactly-once failure semantics, systems of this generation are the first open source stream processors that are capable of computing consistent and accurate results. By computing results only based on the actual data, these systems are also able to process historical data in the same way as “live” data, i.e., data which is ingested as soon as it is produced. Another improvement was the dissolution of the latency-throughput trade-off. While previous stream processors only provided either high throughput or low latency, systems of the third generation are able to serve both ends of the spectrum. Stream processors of this generation made the lambda architecture obsolete.

In addition to the system properties discussed so far, such as failure tolerance, performance, and result accuracy, stream processors also continuously added new operational features. Since streaming applications are often required to run 24/7 with minimum downtime, many stream processors added features such as highly-available setups, tight integration with resource managers, such as YARN or Mesos, and the ability to dynamically scale streaming applications. Other features include support to upgrade application code or migrating a job to a different cluster or a new version of the stream processor without losing the current state of an application.

Apache Flink is a distributed stream processor of the third generation with a competitive feature set. It provides accurate stream processing with high throughput and low latency at scale. In particular the following features let it stand out:

Flink supports event-time and processing-time semantics. Event-time provides consistent and accurate results despite out-of-order events. Processing-time can be applicable for applications with very low latency requirements.

Flink supports exactly-once state consistency guarantees.

Flink achieves millisecond latencies and is able to process millions of events per second. Flink applications can be scaled to run on thousands of cores.

Flink features layered APIs with varying tradeoffs for expressiveness and ease-of-use. This book covers the DataStream API and the ProcessFunction which provide primitives for common stream processing operations, such as windowing and asynchronous operations, and interfaces to precisely control state and time. Flink’s relational APIs, SQL and the LINQ-style Table API, are not discussed in this book.

Flink provides connectors to the most commonly used storage systems such as Apache Kafka, Apache Cassandra, Elasticsearch, JDBC, Kinesis, and (distributed) file systems such as HDFS and S3.

Flink is able to run streaming applications 24/7 with very little downtime due to its highly-available setup (no single point of failure), a tight integration with YARN and Apache Mesos, fast recovery from failures, and the ability to dynamically scale jobs.

Flink allows for updating the application code of jobs and migrating jobs to different Flink clusters without losing the state of the application.

Detailed and customizable collection of system and application metrics help to identify and react to problems ahead of time.

Last but not least, Flink is also a full-fledged batch processor.

In addition to these features, Flink is a very developer-friendly framework due to its easy-to-use APIs. An embedded execution mode starts Flink applications as a single JVM process which can be used to run and debug Flink jobs within an IDE. This feature comes in handy when developing and testing Flink applications.

Next, we will guide you through the process of starting a local cluster and executing a first streaming application in order to give you a first impression of Flink. The application we are going to run converts and aggregates randomly generated temperature sensor readings by time. For this your system needs to have Java 8 (or a later version) installed. We describe the steps for a UNIX environment. If you are running Windows, we recommend to set up a virtual machine with Linux, Cygwin (a Linux environment for Windows), or the Windows Subsystem for Linux, which was introduced with Windows 10.

Go to the Apache Flink webpage flink.apache.org and download the Hadoop-free binary distribution of Apache Flink 1.4.0.

Extract the archive file

tar xvfz flink-1.4.0-bin-scala_2.11.tgz

Start a local Flink cluster

cd flink-1.4.0

./bin/start-cluster.sh

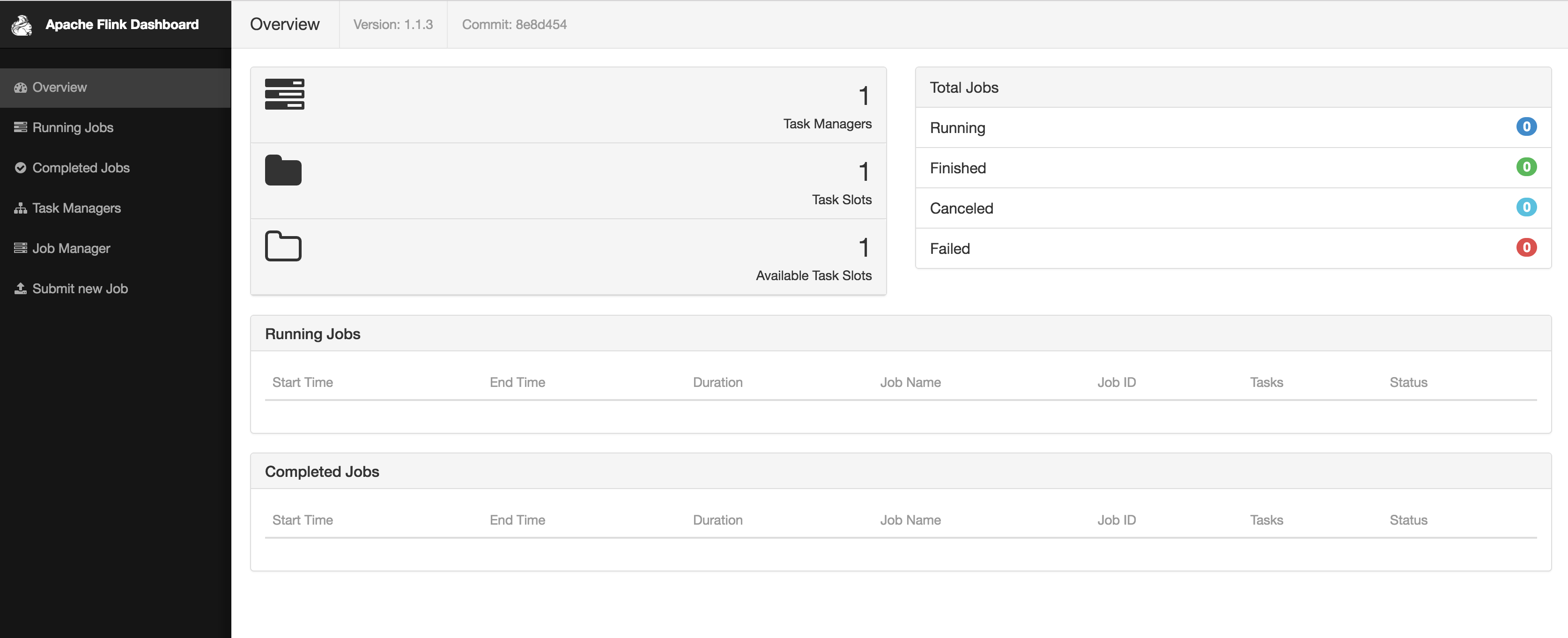

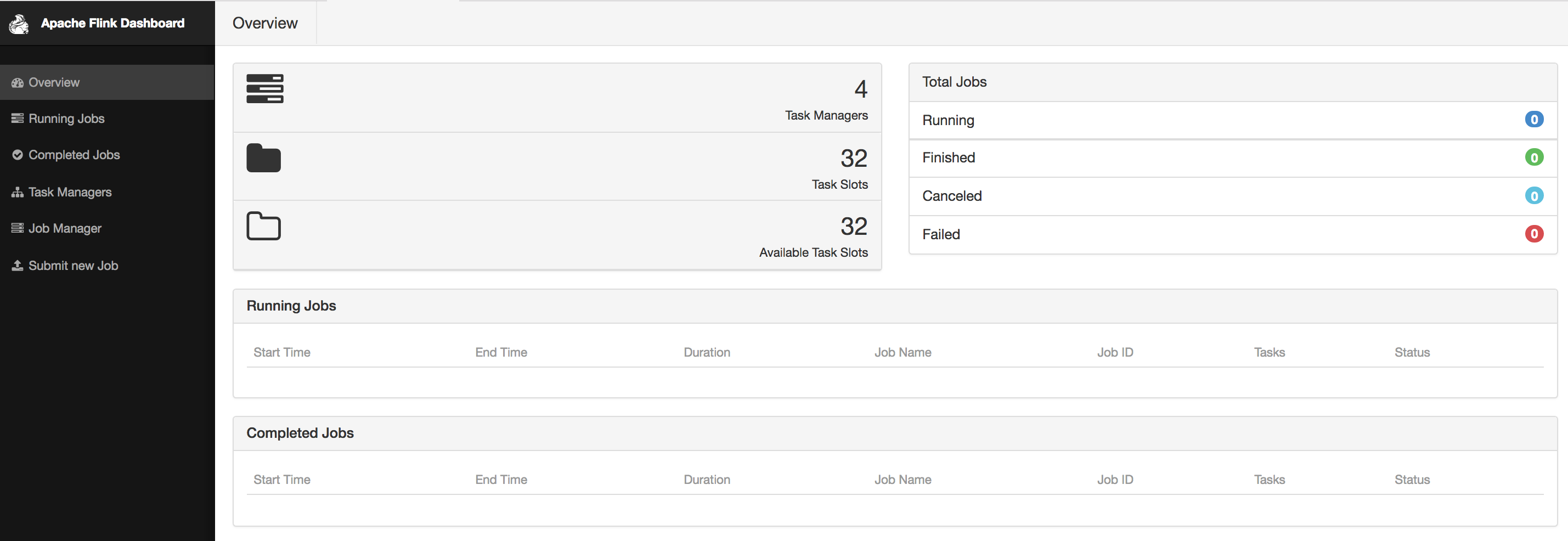

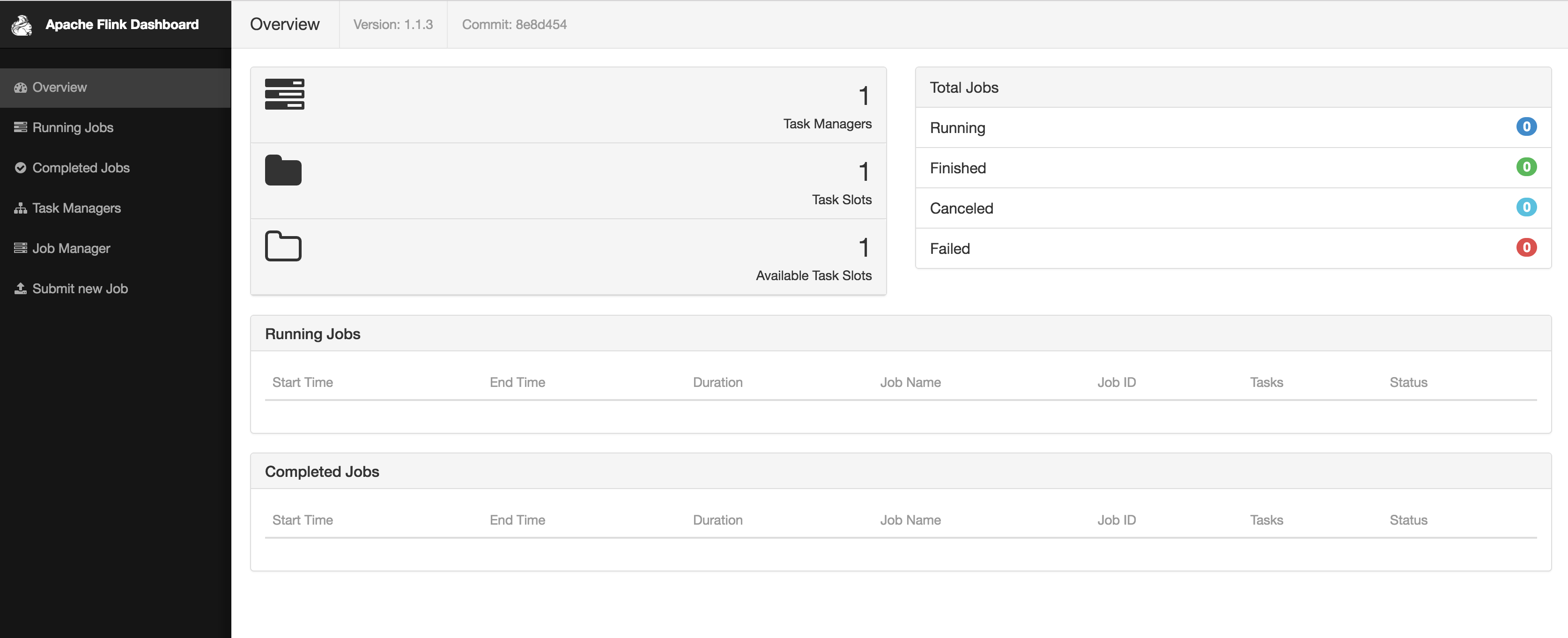

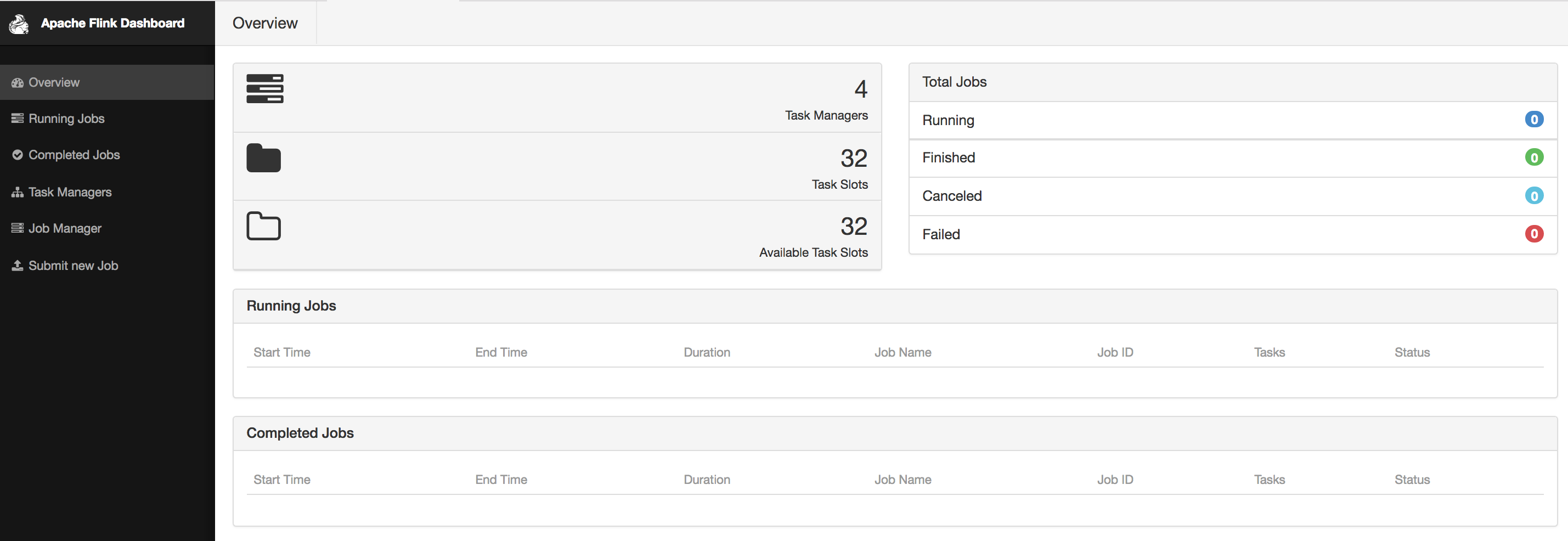

Open the web dashboard on by entering the URL http://localhost:8081 in your browser. As shown in Figure 1-8, you will see some statistics about the local Flink cluster you just started. It will show that a single Task Manager (Flink’s worker processes) is connected and that a single Task Slot (resource units provided by a Task Manager) is available.

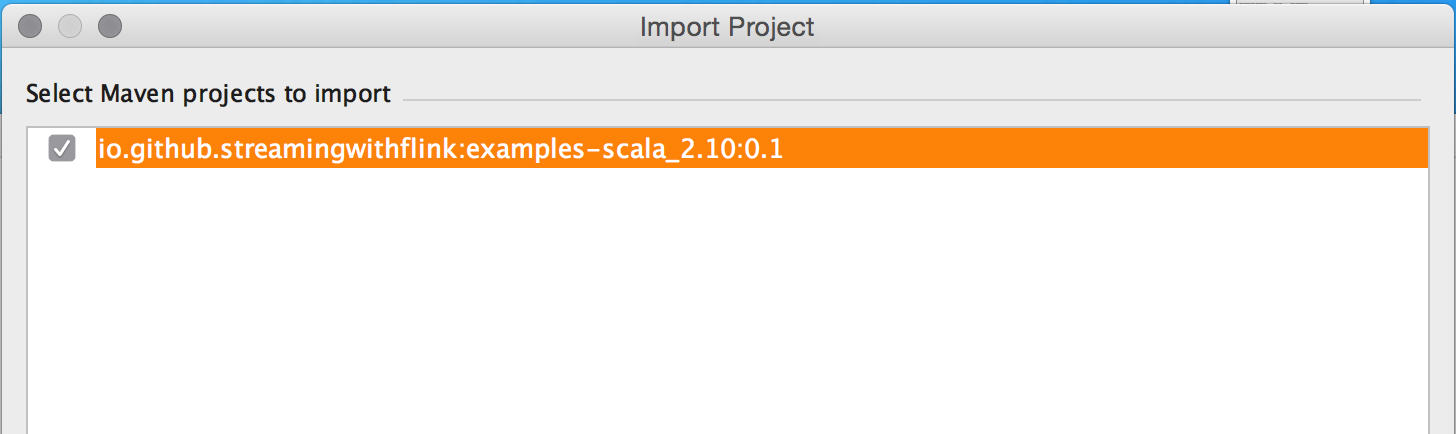

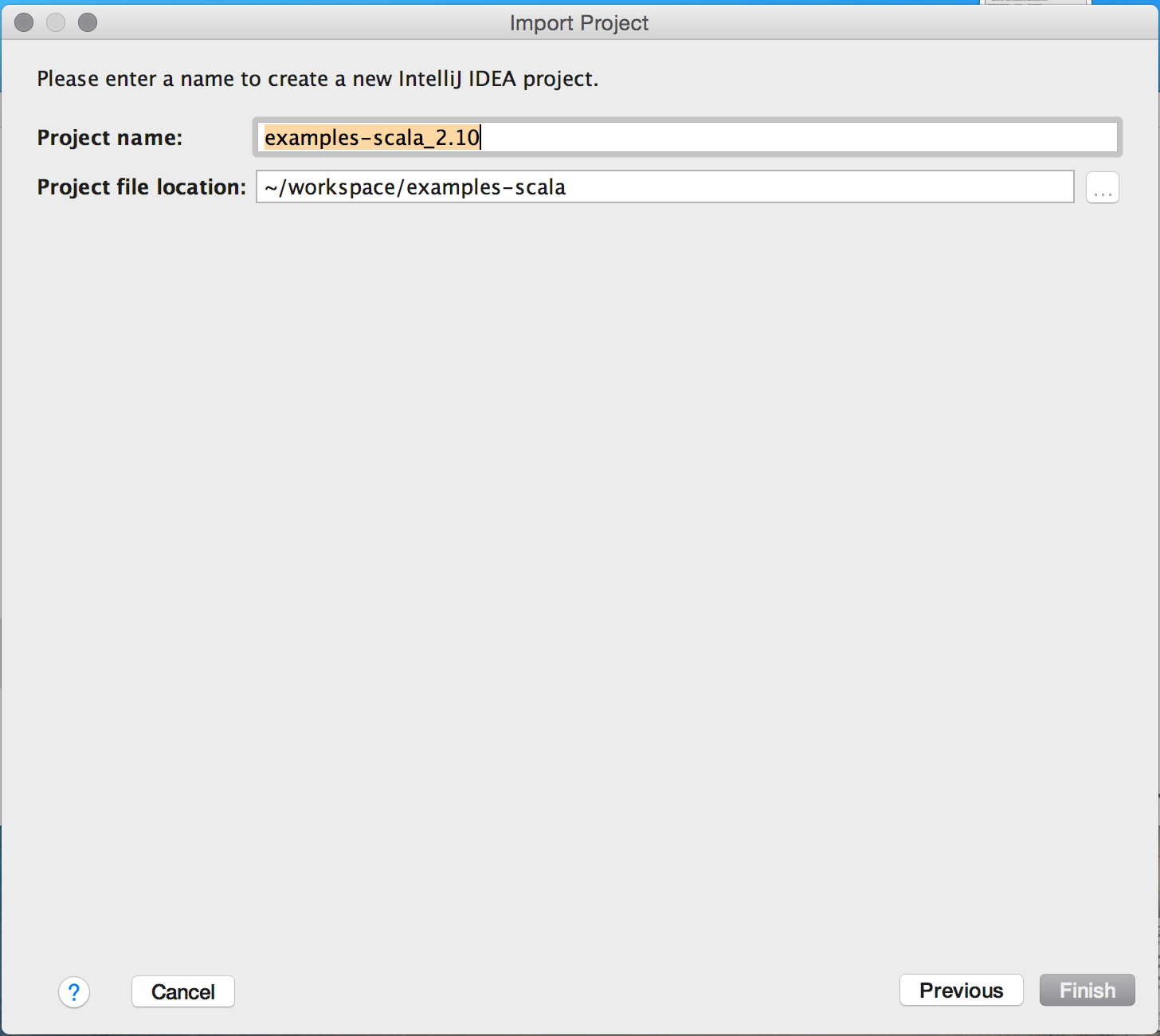

Download the JAR file that includes all example programs of this book.

wget https://streaming-with-flink.github.io/examples/download/examples-scala.jar

Note: you can also build the JAR file yourself by following the steps on the repository’s README file.

Run the example on your local cluster by specifying the applications entry class and the JAR file

./bin/flink run -c io.github.streamingwithflink.AverageSensorReadings examples-scala.jar

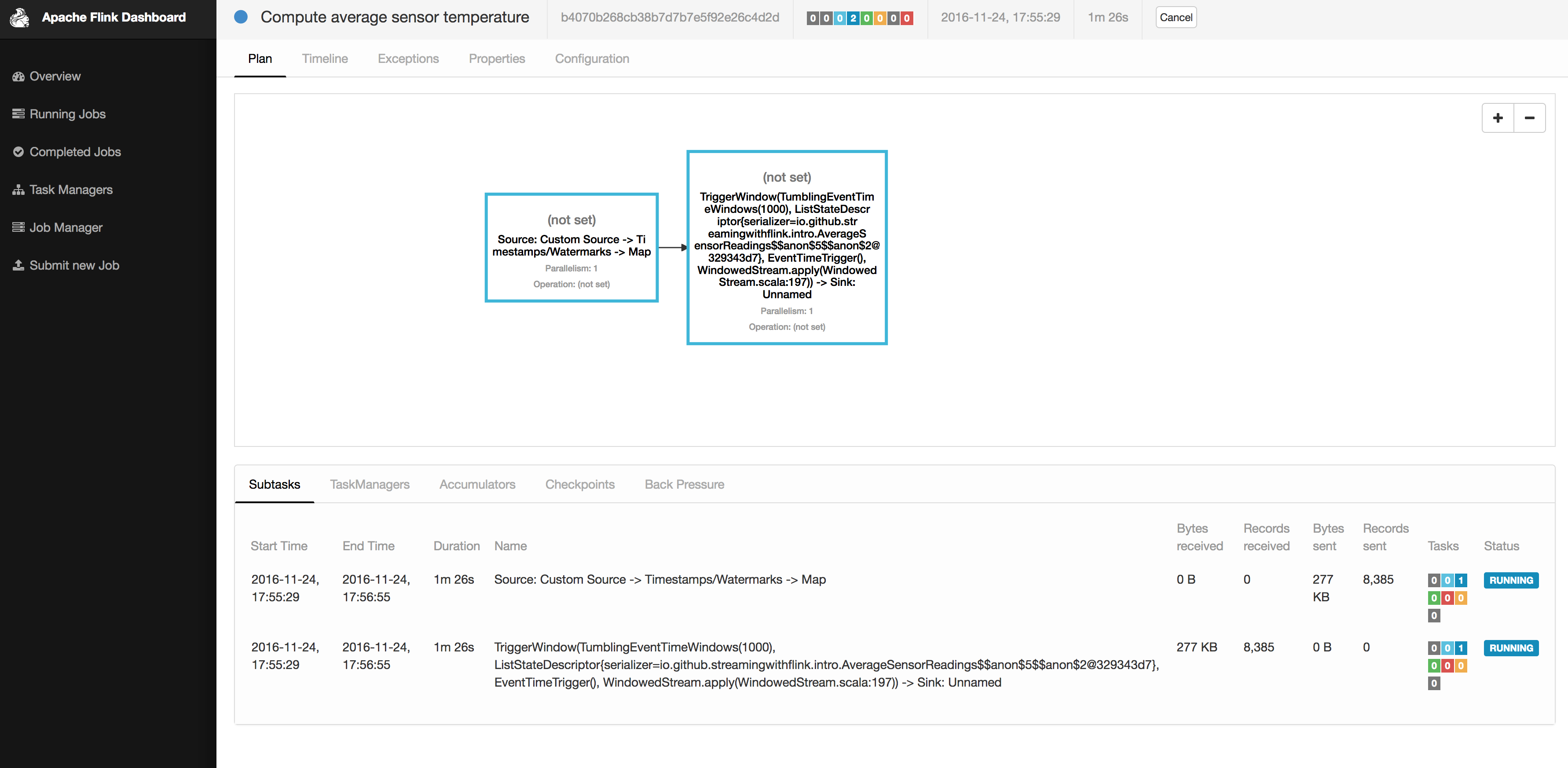

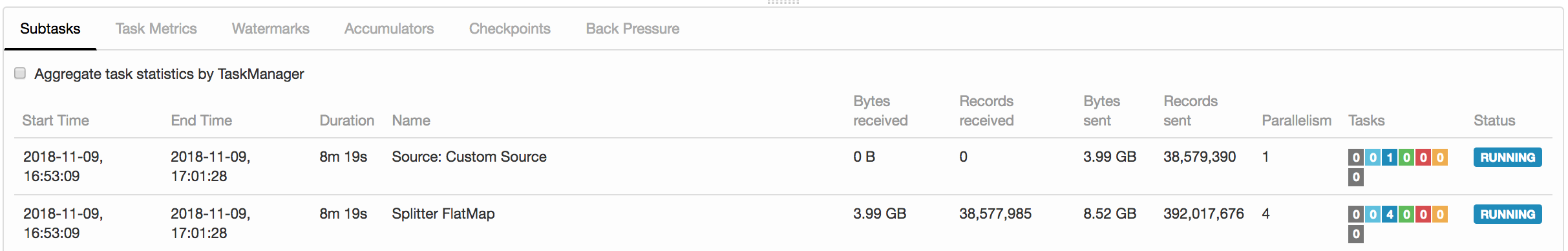

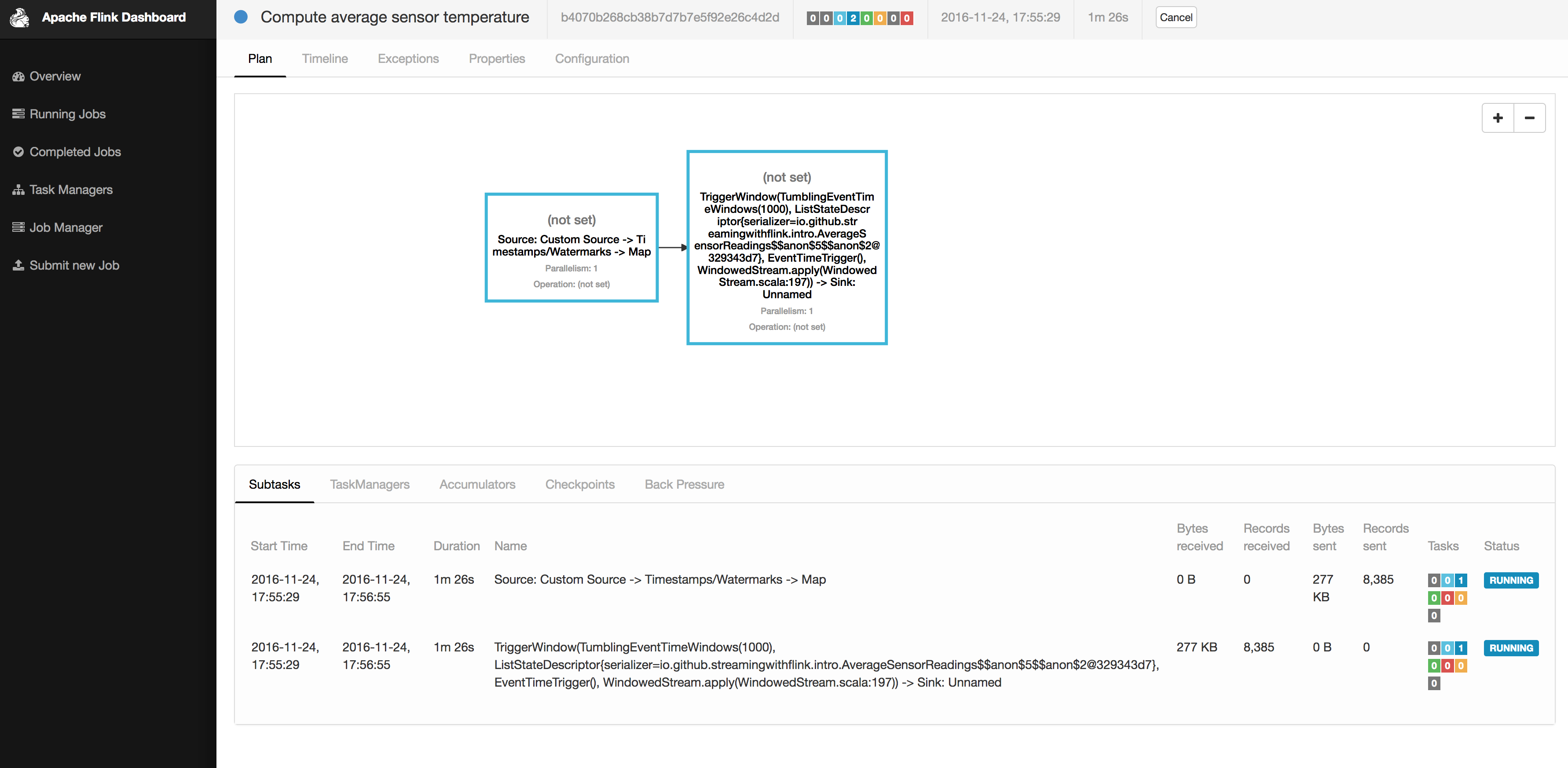

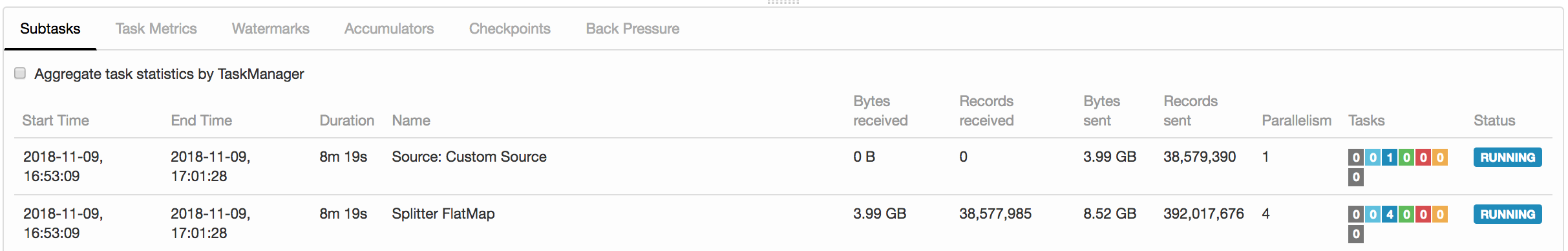

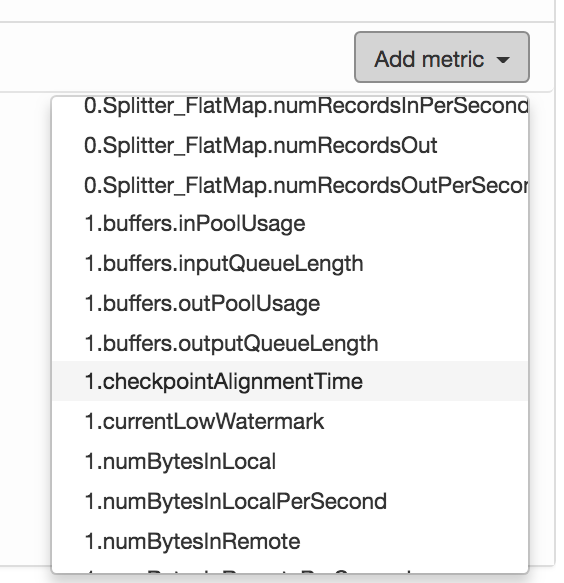

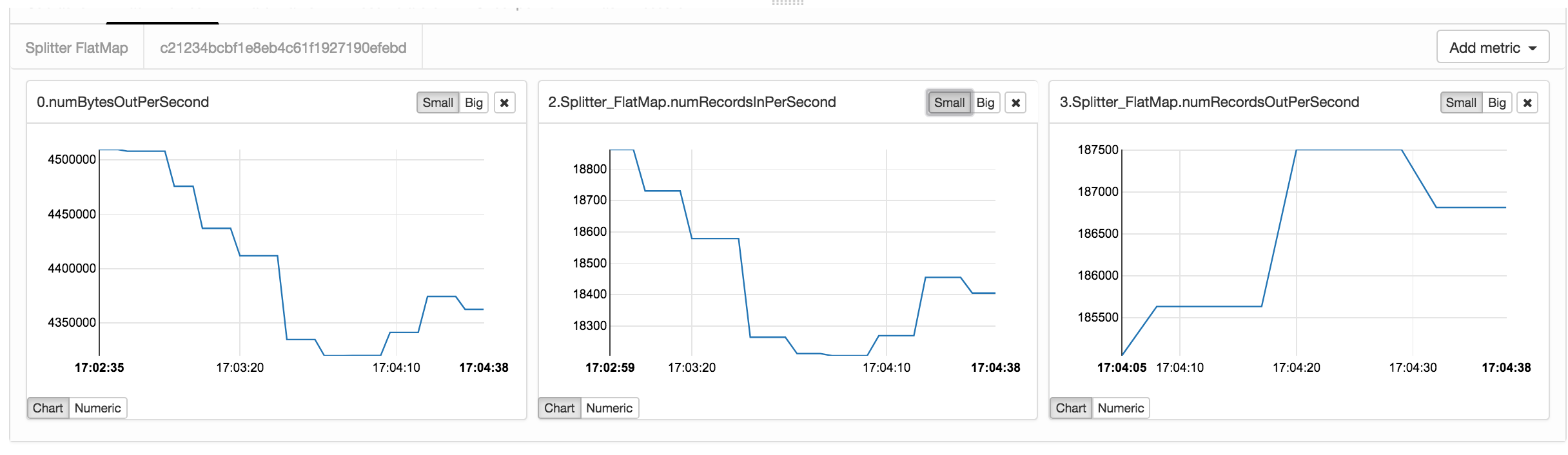

Inspect the web dashboard. You should see a job listed under “Running Jobs”. If you click on that job you will see the data flow and live metrics about the operators of the running job similar to the screenshot in Figure 1-9.

The output of the job is written to the standard out of Flink’s worker process which is by default redirected into a file in the ./log folder. You can monitor the constantly produced output using the tail command for example as follows

tail -f ./log/flink-<user>-jobmanager-<hostname>.out

You should see lines as the following ones being written to the file

SensorReading(sensor_2,1480005737000,18.832819812267438)

SensorReading(sensor_5,1480005737000,52.416477673987856)

SensorReading(sensor_3,1480005737000,50.83979980099426)

SensorReading(sensor_4,1480005737000,-17.783076985394775)

The output can be read as follows: the first field of the SensorReading is a sensorId, the second field is the timestamp as milliseconds since 1970-01-01-00:00, and the third field is an average temperature computed over five seconds.

Since you are running a streaming application, it will continue to run until you cancel it. You can do this by selecting the job in the web dashboard and clicking on the CANCEL button on the top of the page.

Finally, you should stop the local Flink cluster

./bin/stop-cluster.sh

That’s it. You just installed and started your first local Flink cluster and ran your first Flink DataStream program! Of course there is much more to learn about stream processing with Apache Flink and that’s what this book is about.

This book will teach you everything to know about stream processing with Apache Flink. Chapter 2 discusses fundamental concepts and challenges of stream processing and Chapter 3 the system architecture of Flink to address these requirements. Chapters 4 to 8 guide you through setting up a development environment, cover the basics of the DataStream API, and go into the details of Flink’s time semantics and window operators, its connectors to external systems, and the details of Flink’s fault-tolerant operator state. Chapter 9 discusses how to setup and configure Flink clusters in various environments and finally Chapter 10 how to operate, monitor, and maintain streaming applications that run 24/7.

So far, you have seen how stream processing addresses limitations of traditional batch processing and how it enables new applications and architectures. You have become familiar with the evolution of the open-source stream processing space and you have got a brief taste of what a Flink streaming application looks like. In this chapter, you will enter the streaming world for good and you will get the necessary background for the rest of this book.

This chapter is still rather independent of Flink. Its goal is to introduce the fundamental concepts of stream processing and discuss the requirements of stream processing frameworks. We hope that after reading this chapter, you will have gained a better understanding of stream applications requirements and you will be able to evaluate the features of modern stream processing systems.

Before we delve into the fundamentals of stream processing, we must first introduce the necessary background on dataflow programming and establish the terminology that we will use throughout this book.

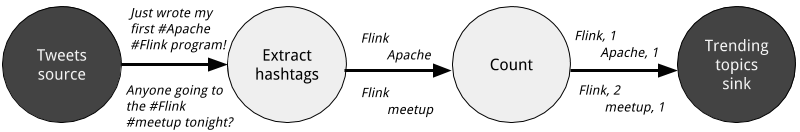

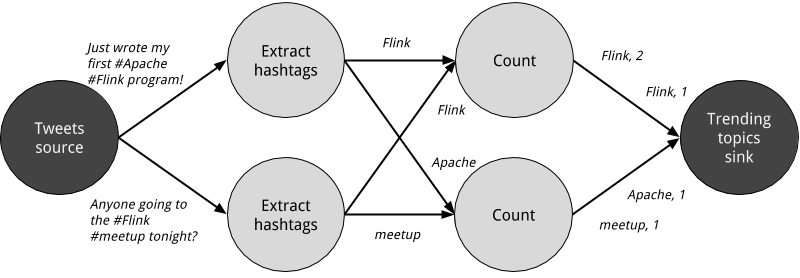

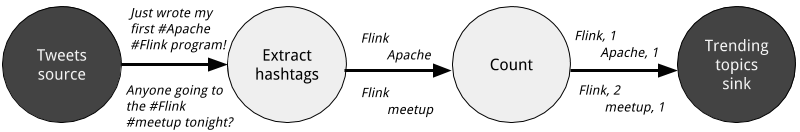

As the name suggests, a dataflow program describes how data flows between operations. Dataflow programs are commonly represented as directed graphs, where nodes are called operators and represent computations and edges represent data dependencies. Operators are the basic functional units of a dataflow application. They consume data from inputs, perform a computation on them, and produce data to outputs for further processing. Operators without input ports are called data sources and operators without output ports are called data sinks. A dataflow graph must have at least one data source and one data sink. Figure 2.1 shows a dataflow program that extracts and counts hashtags from an input stream of tweets.

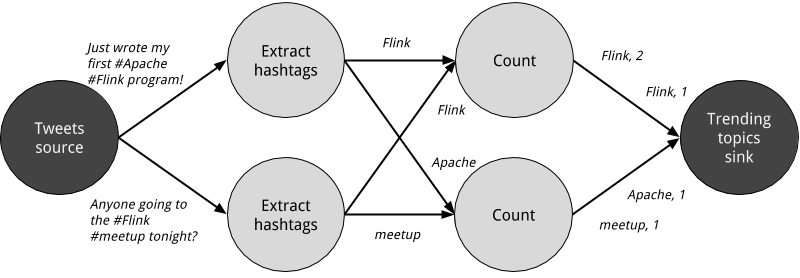

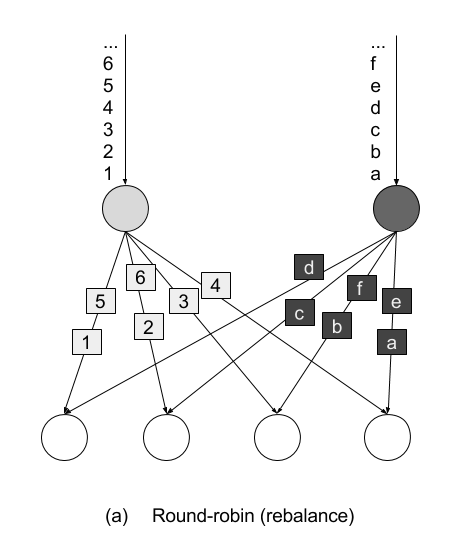

Dataflow graphs like the one of Figure 2.1 are called logical because they convey a high-level view of the computation logic. In order to execute a dataflow program, its logical graph is converted into a physical dataflow graph, which includes details about how the computation is going to be executed. For instance, if we are using a distributed processing engine, each operator might have several parallel tasks running on different physical machines. Figure 2.2 shows a physical dataflow graph for the logical graph of Figure 2.1. While in the logical dataflow graph the nodes represent operators, in the physical dataflow, the nodes are tasks. The “Extract hashtags” and “Count” operators have two parallel operator tasks, each performing a computation on a subset of the input data.

You can exploit parallelism in dataflow graphs in different ways. First, you can partition your input data and have tasks of the same operation execute on the data subsets in parallel. This type of parallelism is called data parallelism. Data parallelism is useful because it allows for processing large volumes of data and spreading the computation load across several computing nodes. Second, you can have tasks from different operators performing computations on the same or different data in parallel. This type of parallelism is called task parallelism. Using task parallelism you can better utilize the computing resources of a cluster.

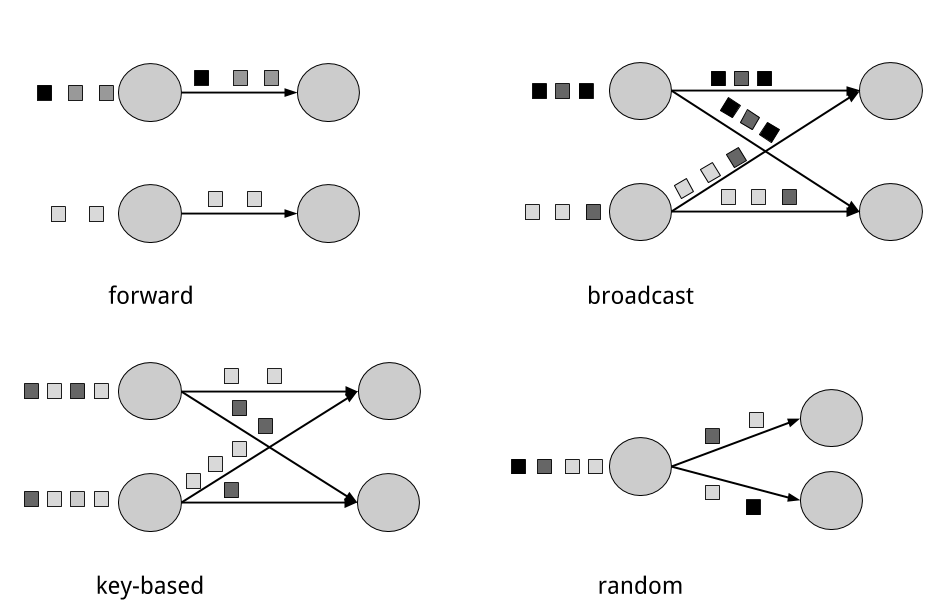

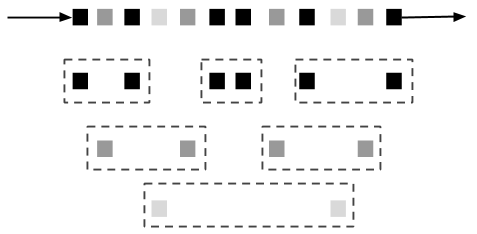

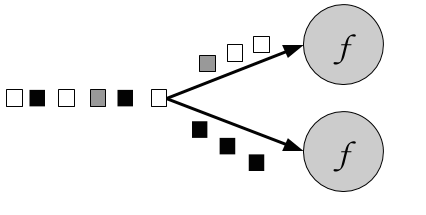

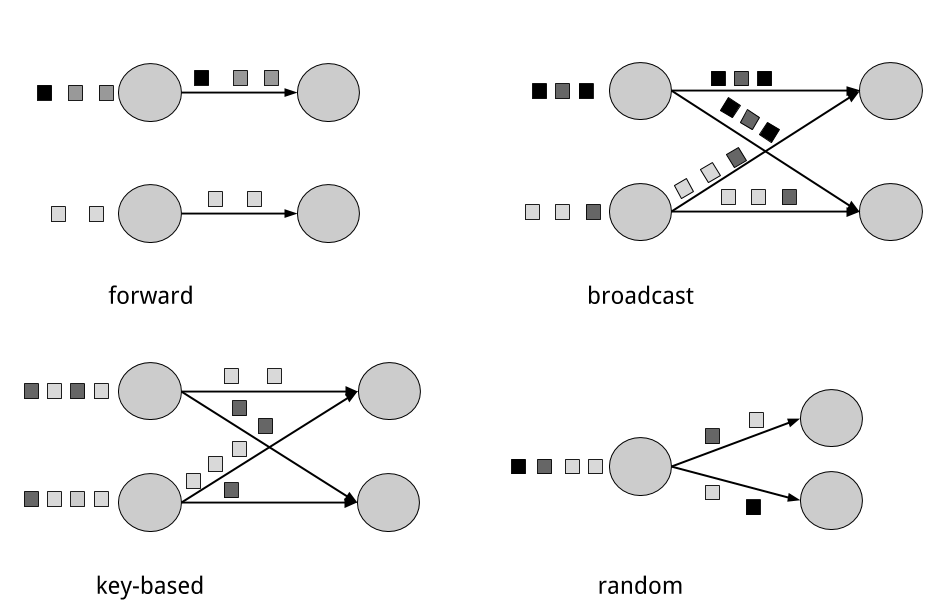

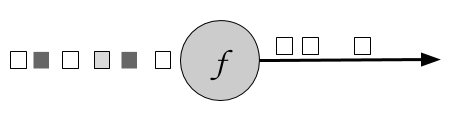

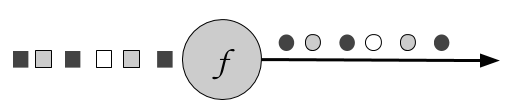

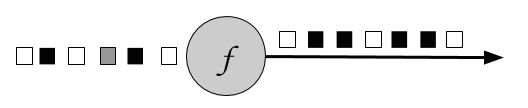

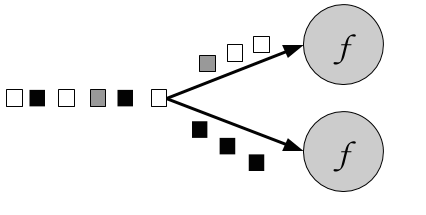

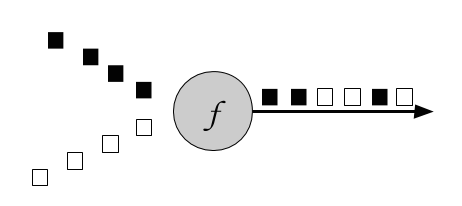

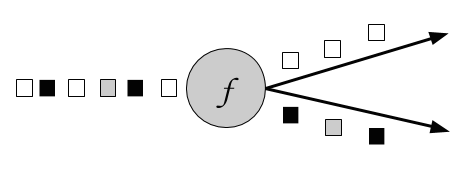

Data exchange strategies define how data items are assigned to tasks in a physical dataflow graph. Data exchange strategies can be automatically chosen by the execution engine depending on the semantics of the operators or explicitly imposed by the dataflow programmer. Here, we briefly review some common data exchange strategies, as shown in Figure 2.3.

The forward strategy and the random strategy can also be viewed as variations of the key-based strategy, where the first preserves the key of the upstream tuple while the latter performs a random re-assignment of keys.

Now that you have become familiar with the basics of dataflow programming, it’s time to see how these concepts apply to processing data streams in parallel. But first, we define the term data stream:

A data stream is a potentially unbounded sequence of events

Events in a data stream can represent monitoring data, sensor measurements, credit card transactions, weather station observations, online user interactions, web searches, etc. In this section, you are going to learn the concepts of processing infinite streams in parallel, using the dataflow programming paradigm.

In the previous chapter, you saw how streaming applications have different operational requirements from traditional batch programs. Requirements also differ when it comes to evaluating performance. For batch applications, we usually care about the total execution time of a job, or how long it takes for our processing engine to read the input, perform the computation, and write back the result. Since streaming applications run continuously and the input is potentially unbounded, there is no notion of total execution time in data stream processing. Instead, streaming applications must provide results for incoming data as fast as possible while being able to handle high ingest rates of events. We express these performance requirements in terms of latency and throughput.

Latency indicates how long it takes for an event to be processed. Essentially, it is the time interval between receiving an event and seeing the effect of processing this event in the output. To understand latency intuitively, consider your daily visit to your favorite coffee shop. When you enter the coffee shop, there might be other customers inside already. Thus, you wait in line and when it is your turn you make an order. The cashier receives your payment and passes your order to the barista who prepares your beverage. Once your coffee is ready, the barista calls your name and you can pick up your coffee from the bench. Your service latency is the time you spend in the coffee shop, from the moment you enter until you have the first sip of coffee.

In data streaming, latency is measured in units of time, such as milliseconds. Depending on the application, you might care about average latency, maximum latency, or percentile latency. For example, an average latency value of 10ms means that events are processed within 10ms on average. Instead, a 95th-percentile latency value of 10ms means that 95% of events are processed within 10ms. Average values hide the true distribution of processing delays and might make it hard to detect problems. If the barista runs out of milk right before preparing your cappuccino, you will have to wait until they bring some from the supply room. While you might get annoyed by this delay, most other customers will still be happy.

Ensuring low latency is critical for many streaming applications, such as fraud detection, raising alarms, network monitoring, and offering services with strict service level agreements (SLAs). Low latency is a key characteristic of stream processing and it enables what we call real-time applications. Modern stream processors, like Apache Flink, can offer latencies as low as a few milliseconds. In contrast, traditional batch processing latencies typically range from a few minutes to several hours. In batch processing you first need to gather the events in batches and only then you are able to process them. Thus, the latency is bounded by the arrival time of the last event in each batch and naturally depends on the batch size. True stream processing does not introduce such artificial delays and therefore can achieve really low latencies. In a true streaming model, events can be processed as soon as they arrive in the system and latency more closely reflects the actual work that has to performed on each event.

Throughput is a measure of the system’s processing capacity, i.e. its rate of processing. That is, throughput tells us how many events the system can process per time unit. Revisiting the coffee shop example, if the shop is open from 7am to 7pm and it serves 600 customers in one day, then its average throughput would be 50 customers per hour. While you want latency to be as low as possible, you generally want throughput to be as high as possible.

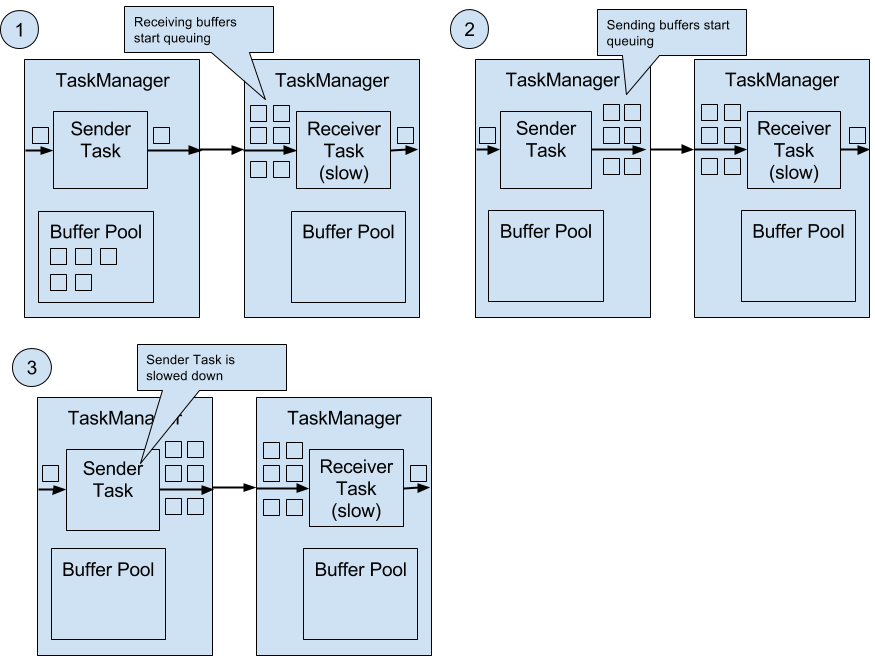

Throughput is measured in events or operations per time unit. It is important to note that the rate of processing depends on the rate of arrival; low throughput does not necessarily indicate bad performance. In streaming systems you usually want to ensure that your system can handle the maximum expected rate of events. That is, you are primarily concerned with determining the peak throughput, i.e. the performance limit when your system is at its maximum load. To better understand the concept of peak throughput, let us consider that system resources are completely unused. As the first event comes in, it will be immediately processed with the minimum latency possible. If you are the first customer showing up at the coffee shop right after it opened its doors in the morning, you will be served immediately. Ideally, you would like this latency to remain constant and independent of the rate of the incoming events. However, once we reach a rate of incoming events such that the system resources are fully used, we will have to start buffering events. In the coffee shop example, you will probably see this happening right after lunch. Many people show up at the same time and you have to wait in line to place your order. At this point the system has reached the peak throughput and further increasing the event rate will only result in worse latency. If the system continues to receive data at a higher rate than it can handle, buffers might become unavailable and data might get lost. This situation is commonly known as backpressure and there exist different strategies to deal with it. In Chapter 3, we look at Flink’s backpressure mechanism in detail.

At this point, it should be quite clear that latency and throughput are not independent metrics. If events take long to travel in the data processing pipeline, we cannot easily ensure high throughput. Similarly, if a system’s capacity is small, events will be buffered and have to wait before they get processed.

Let us revisit the coffee shop example to clarify how latency and throughput affect each other. First, it should be clear that there is an optimal latency in the case of no load. That is, you will get the fastest service if you are the only customer in the coffee shop. However, during busy times, customers will have to wait in line and latency will increase. Another factor that affects latency and consequently throughput is the time it takes to process an event, or the time it takes for each customer to be served in the coffee shop. Imagine that during Christmas holiday season, baristas have to draw a Santa Claus on the cup of each coffee they serve. This way, the time to prepare a single beverage will increase, causing each person to spend more time in the coffee shop, thus lowering the overall throughput.

Then, can you somehow get both low latency and high throughput or is this a hopeless endeavour? One way you can lower latency is by hiring a more skilled barista, i.e. one that prepares coffees faster. At high load, this change will also increase throughput, because more customers will be served in the same amount of time. Another way to achieve the same result is to hire a second barista, that is, to exploit parallelism. The main take-away here is that lowering latency actually increases throughput. Naturally, if a system can perform operations faster, it can perform more operations at the same amount of time. In fact, that is what you achieve by exploiting parallelism in a stream processing pipeline. By processing several streams in parallel, you can lower the latency while processing more events at the same time.

Stream processing engines usually provide a set of built-in operations to ingest, transform, and output streams. These operators can be combined into dataflow processing graphs to implement the logic of streaming applications. In this section, we describe the most common streaming operations.

Operations can be either stateless or stateful. Stateless operations do not maintain any internal state. That is, the processing of an event does not depend on any events seen in the past and no history is kept. Stateless operations are easy to parallelize, since events can be processed independently of each other and of their arriving order. Moreover, in the case of a failure, a stateless operator can be simply restarted and continue processing from where it left off. On the contrary, stateful operators may maintain information about the events they have received before. This state can be updated by incoming events and can be used in the processing logic of future events. Stateful stream processing applications are more challenging to parallelize and operate in a fault tolerant manner because state needs to be efficiently partitioned and reliably recovered in the case of failures. You will learn more about stateful stream processing, failure scenarios, and consistency in the end of this chapter.

Data ingestion and data egress operations allow the stream processor to communicate with external systems. Data ingestion is the operation of fetching raw data from external sources and converting it into a format that is suitable for processing. Operators that implement data ingestion logic are called data sources. A data source can ingest data from a TCP socket, a file, a Kafka topic, or a sensor data interface. Data egress is the operation of producing output in a form that is suitable for consumption by external systems. Operators that perform data egress are called data sinks and examples include files, databases, message queues, and monitoring interfaces.

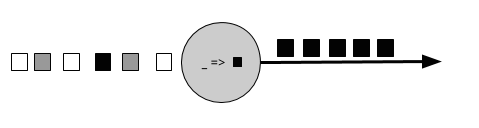

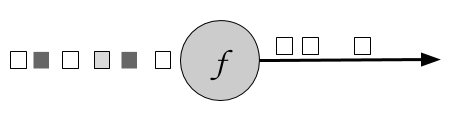

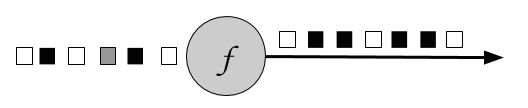

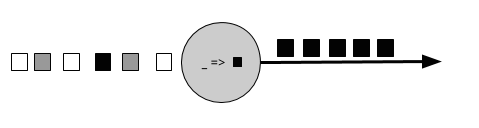

Transformation operations are single-pass operations that process each event independently. These operations consume one event after the other and apply some transformation to the event data, producing a new output stream. The transformation logic can be either integrated in the operator or provided by a user-defined function (UDF), as shown in Figure 2.4. UDFs are written by the application programmer and implement custom computation logic.

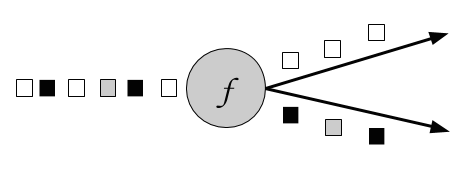

Operators can accept multiple inputs and produce multiple output streams. They can also modify the structure of the dataflow graph by either splitting a stream into multiple streams or merging streams into a single flow. We discuss the semantics of all operators available in Flink in Chapter 5.

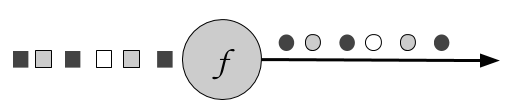

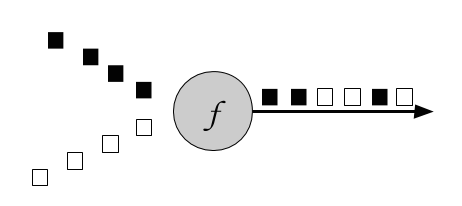

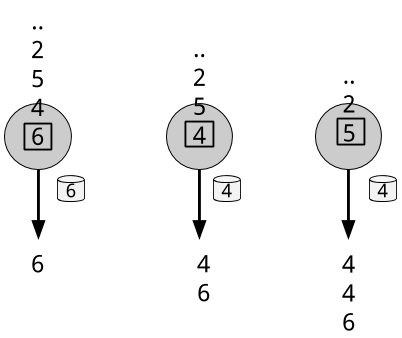

A rolling aggregation is an aggregation, such as sum, minimum, and maximum, that is continuously updated for each input event. Aggregation operations are stateful and combine the current state with the incoming event to produce an updated aggregate value. Note that to be able to efficiently combine the current state with an event and produce a single value, the aggregation function must be associative and commutative. Otherwise, the operator would have to store the complete stream history. Figure 2.5 shows a rolling minimum aggregation. The operator keeps the current minimum value and accordingly updates it for each incoming event.

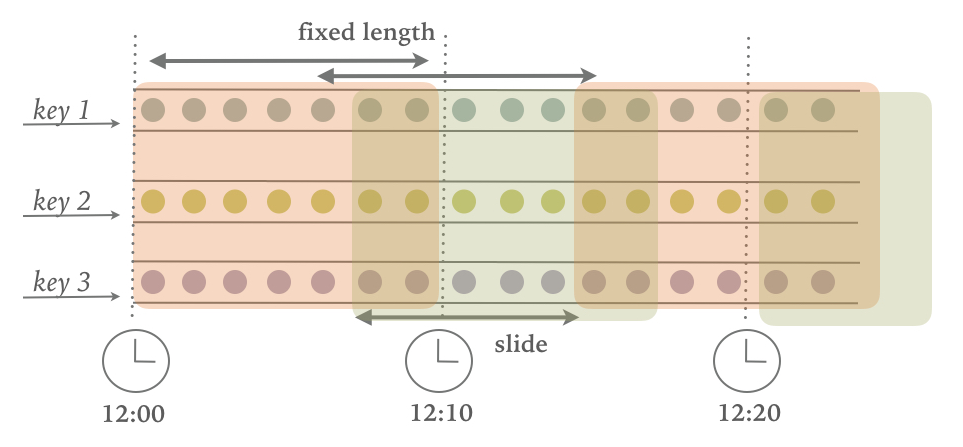

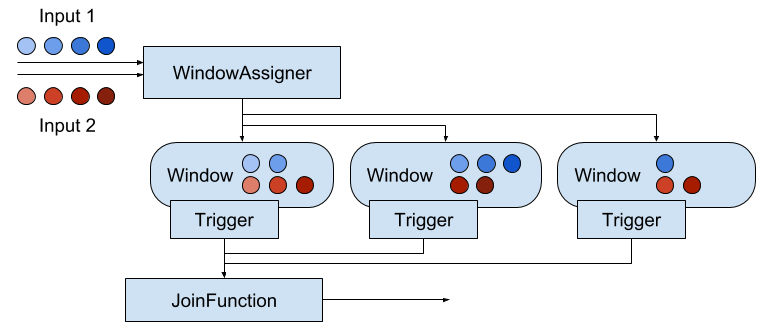

Transformations and rolling aggregations process one event at a time to produce output events and potentially update state. However, some operations must collect and buffer records to compute their result. Consider for example a streaming join operation or a holistic aggregate, such as median. In order to evaluate such operations efficiently on unbounded streams, you need to limit the amount of data these operations maintain. In this section, we discuss window operations, which provide such a mechanism.

Apart from having a practical value, windows also enable semantically interesting queries on streams. You have seen how rolling aggregations encode the history of the whole stream in an aggregate value and provide us with a low-latency result for every event. This is fine for some applications, but what if you are only interested in the most recent data? Consider an application that provides real-time traffic information to drivers so that they can avoid congested routes. In this scenario, you want to know if there has been an accident in a certain location within the last few minutes. On the other hand, knowing about all accidents that have ever happened might not be so interesting in this case. What’s more, by reducing the stream history to a single aggregate, you lose the information about how your data varies over time. For instance, you might want to know how many vehicles cross an intersection every 5 minutes.

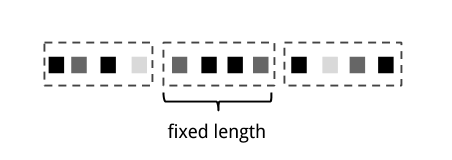

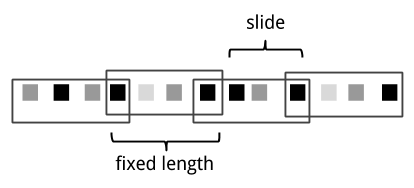

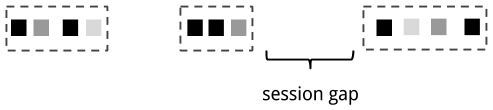

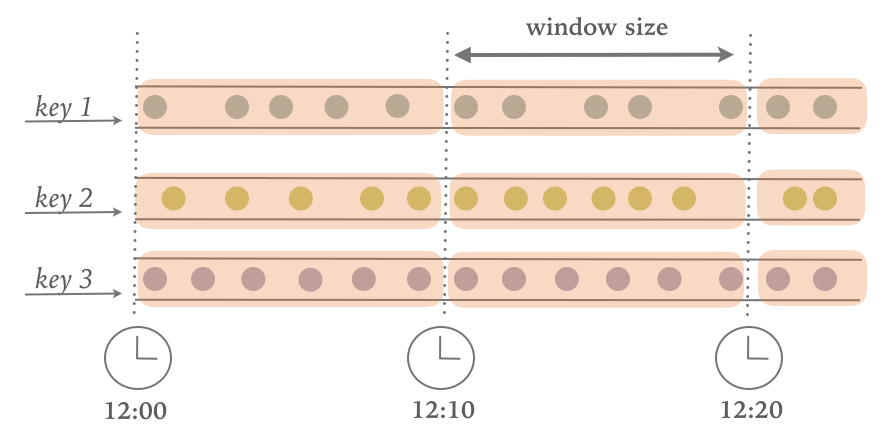

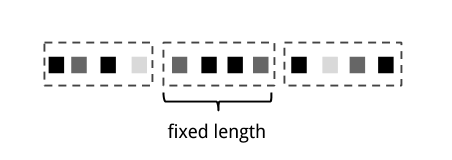

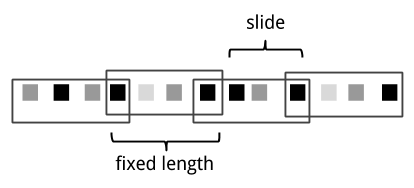

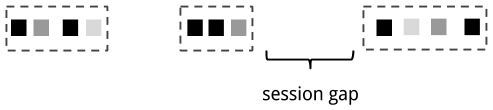

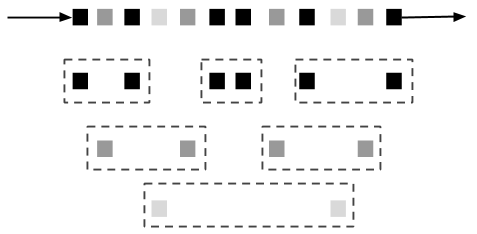

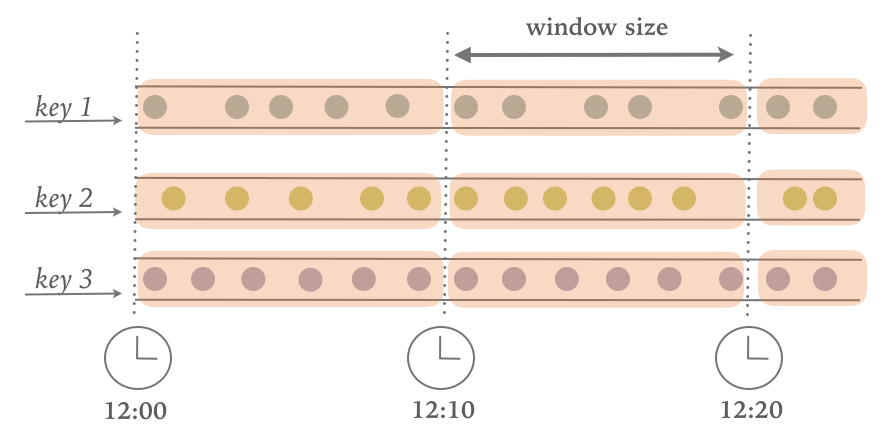

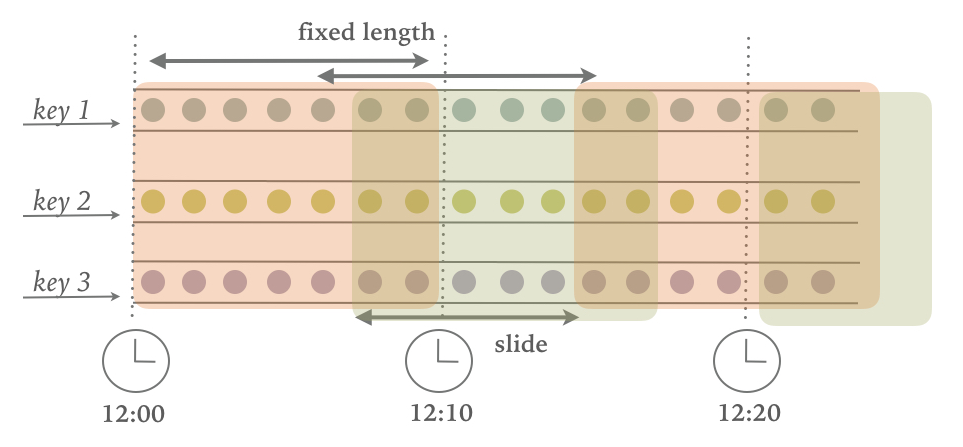

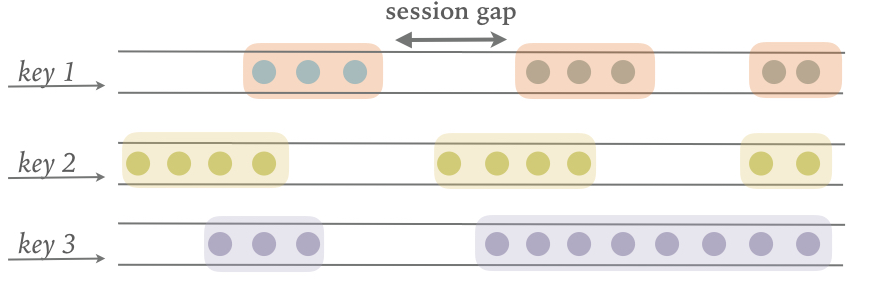

Window operations continuously create finite sets of events called buckets from an unbounded event stream and let us perform computations on these finite sets. Events are usually assigned to buckets based on data properties or based on time. To properly define window operator semantics, we need to answer two main questions: “how are events assigned to buckets?” and “how often does the window produce a result?”. The behavior of windows is defined by a set of policies. Window policies decide when new buckets are created, which events are assigned to which buckets, and when the contents of a bucket get evaluated. The latter decision is based on a trigger condition. When the trigger condition is met, the bucket contents are sent to an evaluation function that applies the computation logic on the bucket elements. Evaluation functions can be aggregations like sum or minimum or custom operations applied on the bucket’s collected elements. Policies can be based on time (e.g. events received in the last 5 seconds), on count (e.g. the last 100 events), or on a data property. In this section, we describe the semantics of common window types.

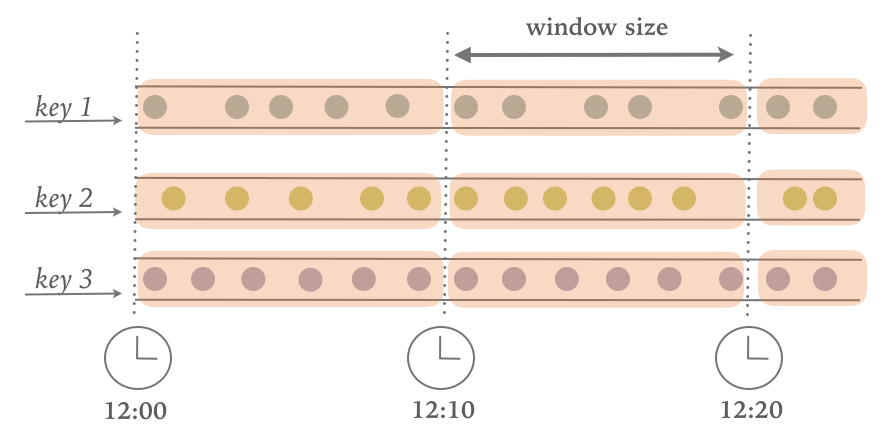

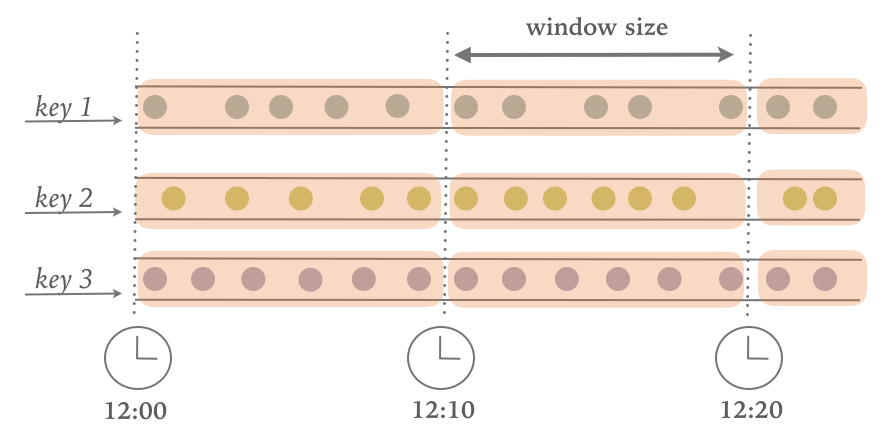

All the window types that you have seen so far are global windows and operate on the full stream. In practice though you might want to partition a stream into multiple logical streams and define parallel windows. For instance, if you are receiving measurements from different sensors, you probably want to group the stream by sensor id before applying a window computation. In parallel windows, each partition applies the window policies independently of other partitions. Figure 2.10 shows a parallel count-based tumbling window of length 2 which is partitioned by event color.

Window operations are closely related to two dominant concepts in stream processing: time semantics and state management. Time is perhaps the most important aspect of stream processing. Even though low latency is an attractive feature of stream processing, its true value is way beyond just offering fast analytics. Real-world systems, networks, and communication channels are far from perfect, thus streaming data can often be delayed or arrive out-of-order. It is crucial to understand how you can deliver accurate and deterministic results under such conditions. What’s more, streaming applications that process events as they are produced should also be able to process historical events in the same way, thus enabling offline analytics or even time travel analyses. Of course, none of this matters if your system cannot guard state against failures. All the window types that you have seen so far need to buffer data before performing an operation. In fact, if you want to compute anything interesting in a streaming application, even a simple count, you need to maintain state. Considering that streaming applications might run for several days, months, or even years, you need to make sure that state can be reliably recovered under failures and that your system can guarantee accurate results even if things break. In the rest of this chapter, we are going to look deeper into the concepts of time and state guarantees under failures in data stream processing.

In this section, we introduce time semantics and describe the different notions of time in streaming. We discuss how a stream processor can provide accurate results with out-of-order events and how you can perform historical event processing and time travel with streaming.

When dealing with a potentially unbounded stream of continuously arriving events, time becomes a central aspect of applications. Let’s assume you want to compute results continuously, for example every one minute. What would one minute really mean in the context of our streaming application?

Consider a program that analyzes events generated by users playing online mobile games. Users are organized in teams and the application collects a team’s activity and provides rewards in the game, such as extra lives and level-ups, based on how fast the team’s members meet the game’s goals. For example, if all users in a team pop 500 bubbles within one minute, they get a level-up. Alice is a devoted player who plays the game every morning during her commute to work. The problem is that Alice lives in Berlin and she takes the subway to work. And everyone knows that the mobile internet connection in the Berlin subway is lousy. Consider the case where Alice starts popping bubbles while her phone is connected to the network and sends events to the analysis application. Then suddenly, the train enters a tunnel and her phone gets disconnected. Alice keeps on playing and the game events are buffered in her phone. When the train exits the tunnel, she comes back online, and pending events are sent to the application. What should the application do? What’s the meaning of one minute in this case? Does it include the time Alice was offline or not?

Online gaming is a simple scenario showing how operator semantics should depend on the time when events actually happen and not the time when the application receives the events. In the case of a mobile game, consequences can be as bad as Alice and her team getting disappointed and never playing again. But there are much more time-critical applications whose semantics we need to guarantee. If we only consider how much data we receive within one minute, our results will vary and depend on the speed of the network connection or the speed of the processing. Instead, what really defines the amount of events in one minute is the time of the data itself.

In Alice’s game example, the streaming application could operate with two different notions of time, Processing time or Event time. We describe both notions in the following sections.

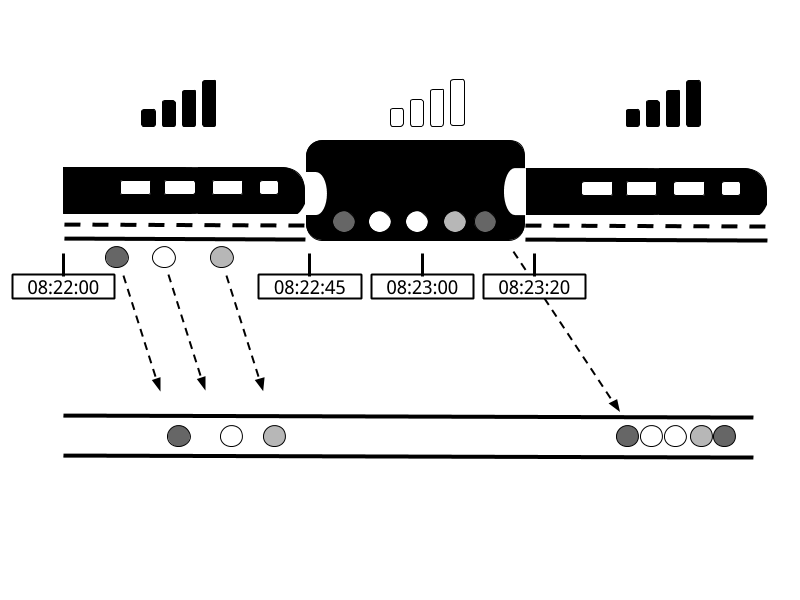

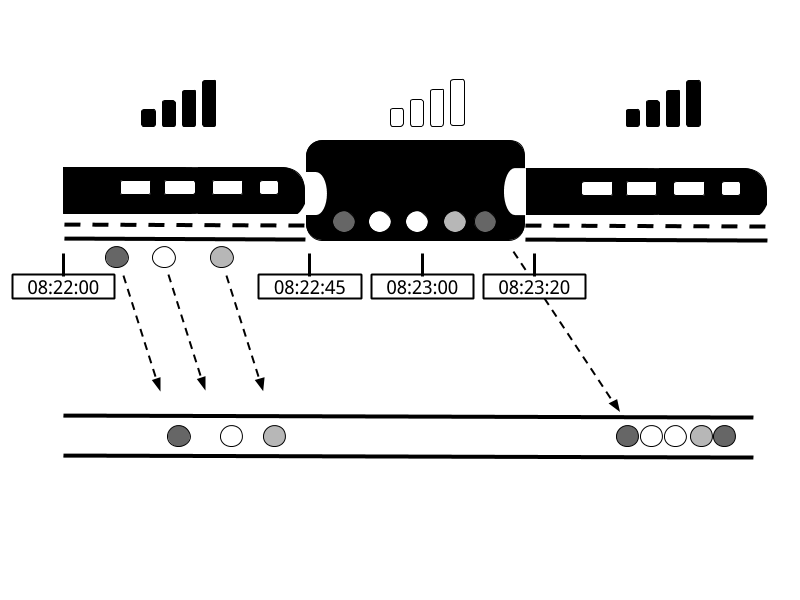

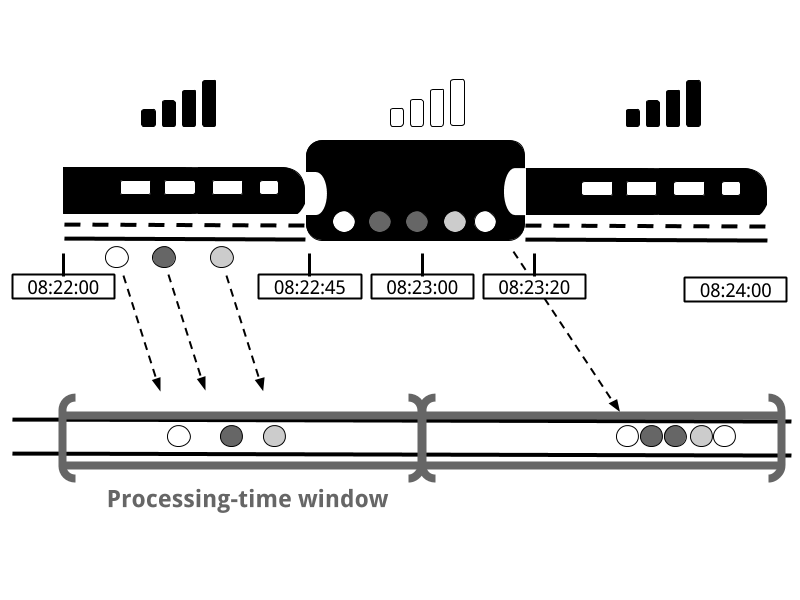

Processing time is the time of the local clock on the machine where the operator processing the stream is being executed. A processing-time window includes all events that happen to have arrived at the window operator within a time period, as measured by the wall-clock of its machine. As shown in Figure 2-12, in Alice’s case, a processing-time window would continue counting time when her phone gets disconnected, thus not accounting for her game activity during that time.

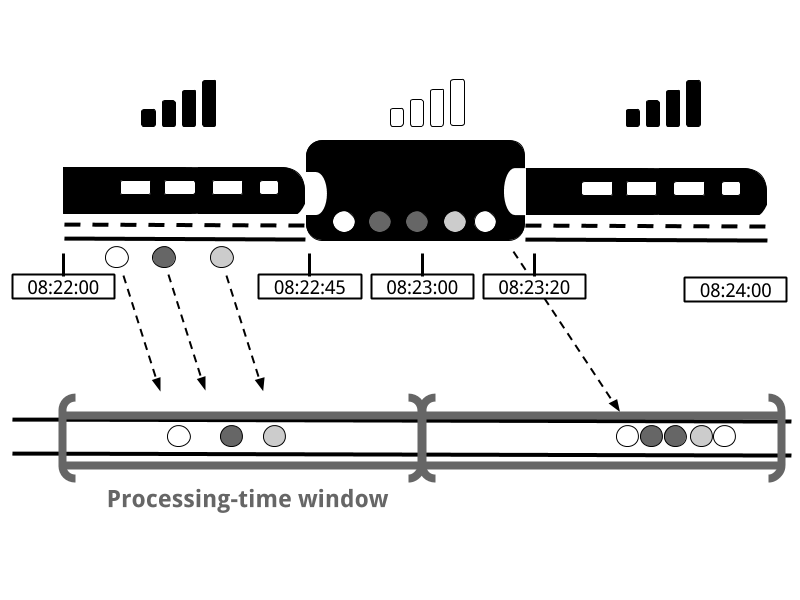

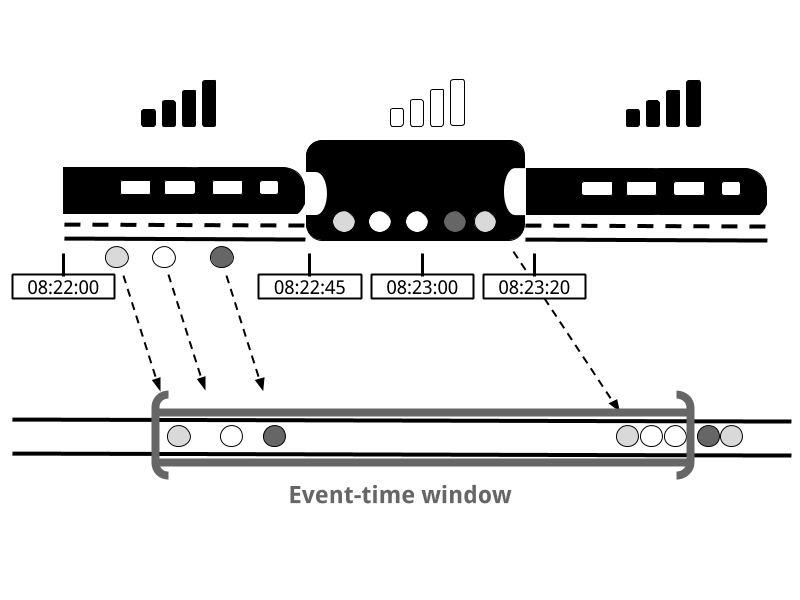

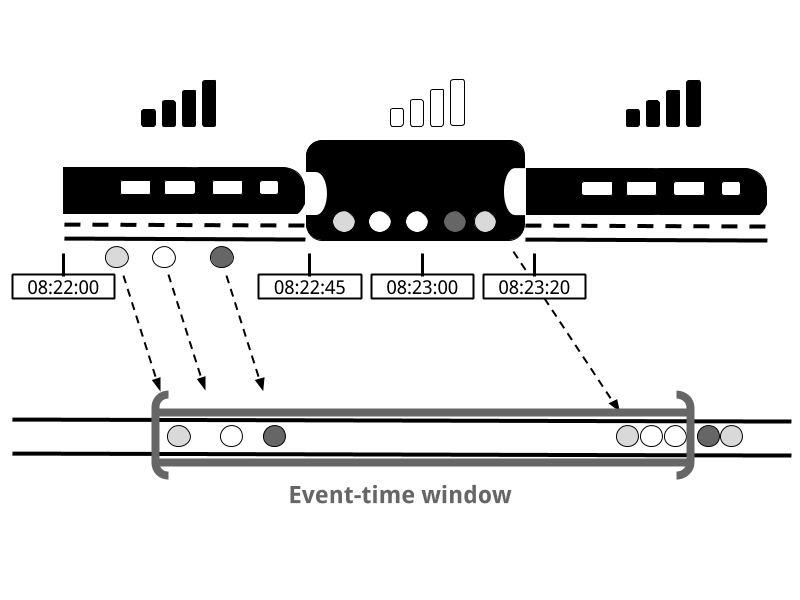

Event-time is the time when an event in the stream actually happened. Event time is based on a timestamp that is attached on the events of the stream. Timestamps usually exist inside the event data before they enter the processing pipeline (e.g. event creation time). Figure 2-13 shows that an event-time window would correctly place events in a window, reflecting the reality of how things happened, even though some events were delayed.

Event-time completely decouples the processing speed from the results. Operations based on event-time are predictable and their results deterministic. An event-time window computation will yield the same result no matter how fast the stream is processed or when the events arrive at the operator.

Handling delayed events is only one of the challenges that you can overcome with event time. Except from experiencing network delays, streams might be affected by many other factors resulting in events arriving out-of-order. Consider Bob, another player of the online mobile game, who happens to be on the same train as Alice. Bob and Alice play the same game but they have different mobile providers. While Alice’s phone loses connection when inside the tunnel, Bob’s phone remains connected and delivers events to the gaming application.

By relying on event time, we can guarantee result correctness even in such cases. What’s more, when combined with replayable streams, the determinism of timestamps gives you the ability to fast-forward the past. That is, you can re-play a stream and analyze historic data as if events are happening in real-time. Additionally, you can fast-forward the computation to the present so that once your program catches up with the events happening now, it can continue as a real-time application using exactly the same program logic.

In our discussion about event-time windows so far, we have overlooked one very important aspect: how do we decide when to trigger an event-time window? That is, how long do we have to wait before we can be certain that we have received all events that happened before a certain point of time? And how do we even know that data will be delayed? Given the unpredictable reality of distributed systems and arbitrary delays that might be caused by external components, there is no categorically correct answer to these questions. In this section, we will see how we can use the concept of watermarks to configure event-time window behavior.

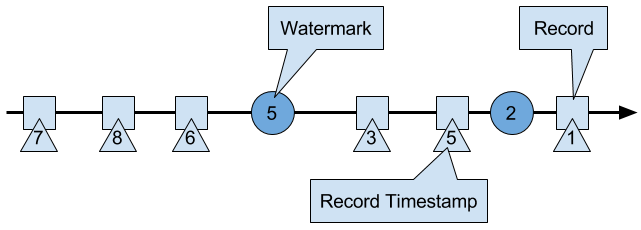

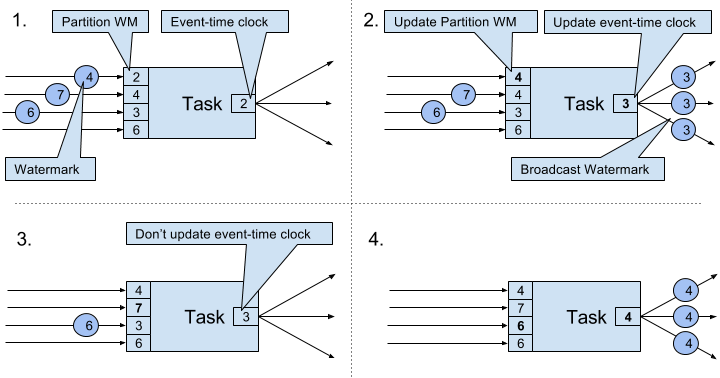

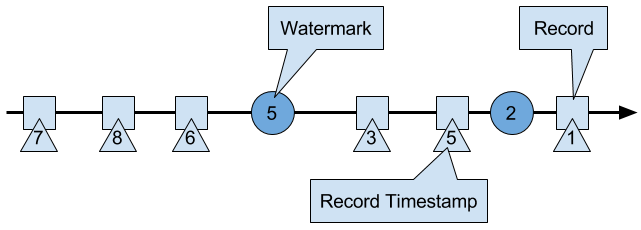

A watermark is a global progress metric that indicates a certain point in time when we are confident that no more delayed events will arrive. In essence, watermarks provide a logical clock which informs the system about the current event time. When an operator receives a watermark with time T, it can assume that no further events with timestamp less than T will be received. Watermarks are essential to both event-time windows and operators handling out-of-order events. Once a watermark has been received, operators are signaled that all timestamps for a certain time interval have been observed and either trigger computation or order received events.

Watermarks provide a configurable trade-off between results confidence and latency. Eager watermarks ensure low latency but provide lower confidence. In this case, late events might arrive after the watermark and we should provide some code to handle them. On the other hand, if watermarks are too slow to arrive, you have high confidence but you might unnecessarily increase processing latency.

In many real-world applications, the system does not have enough knowledge to perfectly determine watermarks. In the mobile gaming case for example, it is practically impossible to know for how long a user might remain disconnected; they could be going through a tunnel, boarding a plane, or never playing again. No matter if watermarks are user-defined or automatically generated, tracking global progress in a distributed system might be problematic in the presence of straggler tasks. Hence, simply relying on watermarks might not always be a good idea. Instead, it is crucial that the stream processing system provides some mechanism to deal with events that might arrive after the watermark. Depending on the application requirements, you might want to ignore such events, log them, or use them to correct previous results.

At this point, you might be wondering: Since event time solves all of our problems, why even bother considering processing time? The truth is that processing time can indeed be useful in some cases. Processing-time windows introduce the lowest latency possible. Since you do not take into consideration late events and out-of-order events, a window simply needs to buffer up events and immediately trigger computation once the specified time length is reached. Thus, for applications where speed is more important than accuracy, processing time comes handy. Another case is when you need to periodically report results in real-time, independently of their accuracy. An example application would be a real-time monitoring dashboard that displays event aggregates as they are received. Finally, processing time windows offer a faithful representation of the streams themselves, might also be a desirable property for some use-cases. To recap, processing time offers low latency but results depend on the speed of processing and are not deterministic. On the other hand, event time guarantees deterministic results and allows you to deal with events that are late or even out-of-order.

We now turn to examine another extremely important aspect of stream processing, state. State is ubiquitous in data processing. It is required by any non-trivial computation. To produce a result, a UDF accumulates state over a period or number of events, e.g. to compute an aggregation or detect a pattern. Stateful operators use both incoming events and internal state to compute their output. Take for example a rolling aggregation operator that outputs the current sum of all the events it has seen so far. The operator keeps the current value of the sum as its internal state and updates it every time it receives a new event. Similarly, consider an operator that raises an alert when it detects a “high temperature” event followed by a “smoke” event within 10 minutes. The operator needs to store the “high temperature” event in its internal state, until it sees the “smoke” event or the until 10-minute time period expires.

The importance of state becomes even more evident if we consider the case of using a batch processing system to analyze an unbounded data set. In fact, this has been a common implementation choice before the rise of modern stream processors. In such a case, a job is executed repeatedly over batches of incoming events. When the job finishes, the result is written to persistent storage, and all operator state is lost. Once the job is scheduled for execution on the next batch, it cannot access the state of the previous job. This problem is commonly solved by delegating state management to an external system, such as a database. On the contrary, with continuously running streaming jobs, manipulating state in the application code is substantially simplified. In streaming we have durable state across events and we can expose it as a first-class citizen in the programming model. Arguably, one could use an external system to also manage streaming state, even though this design choice might introduce additional latency.

Since streaming operators process potentially unbounded data, caution should be taken to not allow internal state to grow indefinitely. To limit the state size, operators usually maintain some kind of summary or synopsis of the events seen so far. Such a summary can be a count, a sum, a sample of the events seen so far, a window buffer, or a custom data structure that preserves some property interesting to the running application.

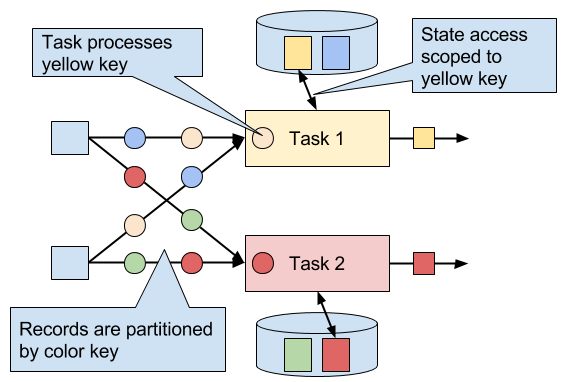

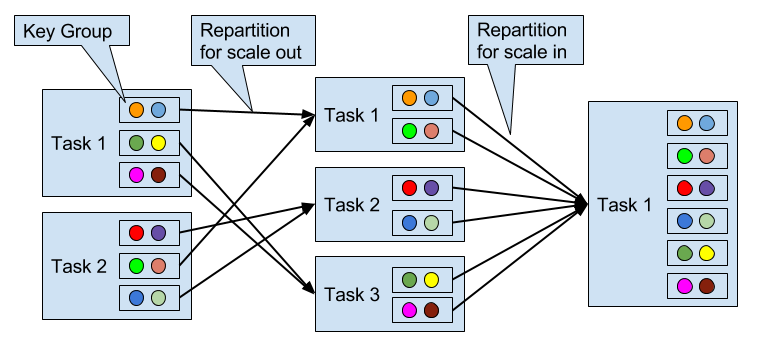

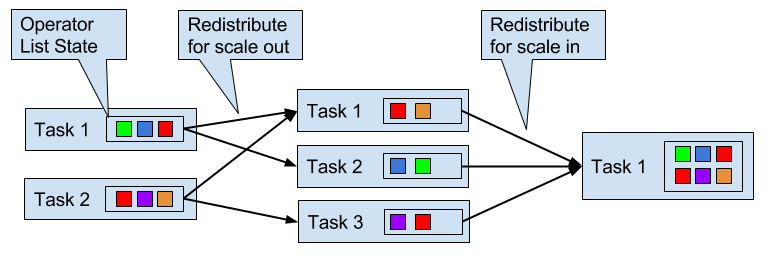

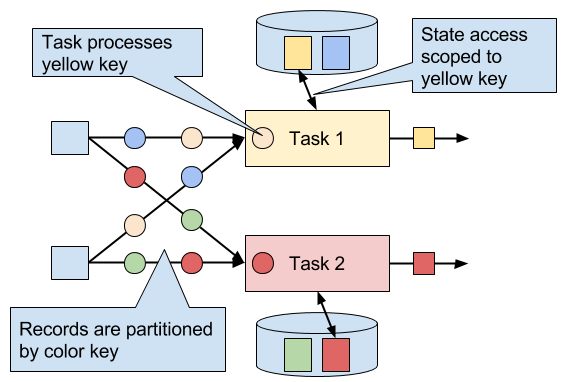

As one could imagine, supporting stateful operators comes with a few implementation challenges. First, the system needs to efficiently manage the state and make sure it is protected from concurrent updates. Second, parallelization becomes complicated, since results depend on both the state and incoming events. Fortunately, in many cases, you can partition the state by a key and manage the state of each partition independently. For example, if you are processing a stream of measurements from a set of sensors, you can use partitioned operator state to maintain state for each sensor independently. The third and biggest challenge that comes with stateful operators is ensuring that the state can be recovered and that results will be correct in the presence of failures. In the next section, you will learn about task failures and result guarantees in detail.

Operator state in streaming jobs is very valuable and should be guarded against failures. If state gets lost during a failure, results will be incorrect after recovery. Streaming jobs run for long periods of time, thus state might be collected over several days or even months. Reprocessing all input to reproduce lost state in the case of failures would be both very expensive and time-consuming.

In the beginning of this chapter, you saw how you can model streaming programs as dataflow graphs. Before execution, these are translated into physical dataflow graphs of many connected parallel tasks, each running some operator logic, consuming input streams and producing output streams for other tasks. Typical real-world setups can easily have hundreds of such tasks running in parallel on many physical machines. In long-running, streaming jobs, each of these tasks can fail at any time. How can you ensure that such failures are handled transparently so that your streaming job can continue to run? In fact, you would like your stream processor to not only continue the processing in the case of task failures, but also provide correctness guarantees about the result and operator state. We discuss all these matters in this section.

For each event in the input stream, a task performs the following steps: (1) receive the event, i.e. store it in a local buffer, (2) possibly update internal state, and (3) produce an output record. A failure can occur during any of these steps and the system has to clearly define its behavior in a failure scenario. If the task fails during the first step, will the event get lost? If it fails after it has updated its internal state, will it update it again after it recovers? And in those cases, will the output be deterministic?

We assume reliable network connections, such that no records are dropped or duplicated and all events are eventually delivered to their destination in FIFO order. Note that Flink uses TCP connections, thus these requirements are guaranteed. We also assume perfect failure detectors and that no task will intentionally act maliciously; that is, all non-failed tasks follow the above steps.

In a batch processing scenario, you can solve all these problems easily since all the input data is available. The most trivial way would be to simply restart the job, but then we would have to replay all data. In the streaming world, however, dealing with failures is not a trivial problem. Streaming systems define their behavior in the presence of failures by offering result guarantees. Next, we review the types of guarantees offered by modern stream processors and some mechanisms that systems implement to achieve those guarantees.

The simplest thing to do when a task fails is to do nothing to recover lost state and replay lost events. At-most-once is the trivial case that guarantees processing of each event at-most-once. In other words, events can be simply dropped and there is no mechanism to ensure result correctness. This type of guarantee is also known as “no-guarantee” since even a system that drops every event can fulfil it. Having no guarantees whatsoever sounds like a terrible idea, but it might be fine, if you can live with approximate results and all you care about is providing the lowest latency possible.

In most real-world applications, the minimum requirement is that events do not get lost. This type of guarantee is called at-least-once and it means that all events will definitely be processed, even though some of them might be processed more than once. Duplicate processing might be acceptable if application correctness only depends on the completeness of information. For example, determining whether a specific event occurs in the input stream can be correctly realized with at-least-once guarantees. In the worst case, you will locate the event more than once. However, counting how many times a specific event occurs in the input stream might return the wrong result under at-least-once guarantees.

In order to ensure at-least-once result correctness, you need to have a mechanism to replay events, either from the source or from some buffer. Persistent event logs write all events to durable storage, so that they can be replayed if a task fails. Another way to achieve equivalent functionality is using record acknowledgements. This method stores every event in a buffer until its processing has been acknowledged by all tasks in the pipeline, at which point the event can be discarded.

This is the strictest and most challenging to achieve type of guarantee. Exactly-once result guarantees means that not only there will be no event loss, but also updates on the internal state will be applied exactly once for each event. In essence, exactly-once guarantees mean that our application will provide the correct result, as if a failure never happened.

Providing exactly-once guarantees requires at-least-once guarantees, thus a data replay mechanism is again necessary. Additionally, the stream processor needs to ensure internal state consistency. That is, after recovery, it should know whether an event update has already been reflected on the state or not. Transactional updates is one way to achieve this result, however, it can incur substantial performance overhead. Instead, Flink uses a lightweight snapshotting mechanism to achieve exactly-once result guarantees. We discuss Flink’s fault-tolerance algorithm in Chapter 3.

The types of guarantees you have seen so far refer to the stream processor component only. In a real-word streaming architecture however, it is common to have several connected components. In the very simple case, there will be at least one source and one sink apart from the stream processor. End-to-end guarantees refer to result correctness across the data processing pipeline. To assess end-to-end guarantees, one has to consider all the components of an application pipeline. Each component provides its own guarantees and the end-to-end guarantee of the complete pipeline would be the weakest of each of its components. It is important to note that sometimes you can get stronger semantics with weaker guarantees. A common case is when a task performs idempotent operations, like maximum or minimum. In this case, you can achieve exactly-once semantics with at-least-once guarantees.

In this chapter, you have learned the fundamental concepts and ideas of data stream processing. You have seen the dataflow programming model and learned how streaming applications can be expressed as distributed dataflow graphs. Next, you have looked into the requirements of processing infinite streams in parallel and you have realized the importance of latency and throughput for stream applications. You have learned basic streaming operations and how you can compute meaningful results on unbounded input data using windows. You have wondered about the meaning of time in stream processing and you have compared the notions of event time and processing time. Finally, you have seen why state is important in streaming applications and how you can guard it against failures and guarantee correct results.

Up to this point, we have considered streaming concepts independently of Apache Flink. In the rest of this book, we are going to see how Flink actually implements these concepts and how you can use its DataStream APIs to write applications that use all of the features that we have introduced so far.

The previous chapter discussed important concepts of distributed stream processing, such as parallelization, time, and state. In this chapter we give a high-level introduction to Flink’s architecture and describe how Flink addresses the aspects of stream processing that we discussed before. In particular, we explain Flink’s process architecture and the design of its networking stack. We show how Flink handles time and state in streaming applications and discuss its fault tolerance mechanisms. This chapter provides relevant background information to successfully implement and operate advanced streaming applications with Apache Flink. It will help you to understand Flink’s internals and to reason about the performance and behavior of streaming applications.

Flink is a distributed system for stateful parallel data stream processing. A Flink setup consists of multiple processes that run distributed across multiple machines. Common challenges that distributed systems need to address are allocation and management of compute resources in a cluster, process coordination, durable and available data storage, and failure recovery.

Flink does not implement all the required functionality by itself. Instead, it focuses on its core function - distributed data stream processing - and leverages existing cluster infrastructure and services. Flink is tightly integrated with cluster resource managers, such as Apache Mesos, YARN, and Kubernetes, but can also be configured to run as a stand-alone cluster. Flink does not provide durable, distributed storage. Instead it supports distributed file systems like HDFS or object stores such as S3. For leader election in highly-available setups, Flink depends on Apache ZooKeeper.

In this section we describe the different components that a Flink setup consists of and discuss their responsibilities and how they interact with each other to execute an application. We present two different styles of deploying Flink applications and discuss how tasks are distributed and executed. Finally, we explain how Flink’s highly-available mode works.

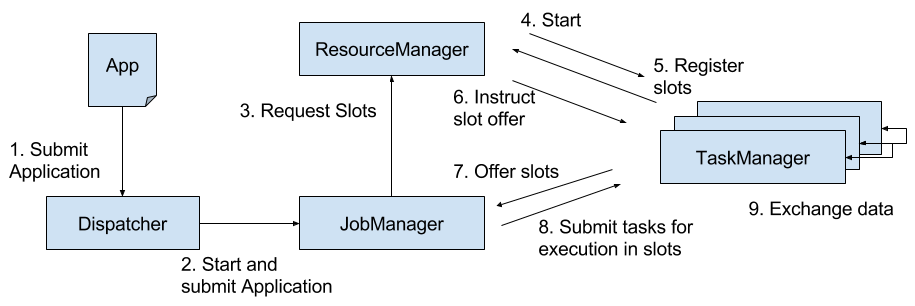

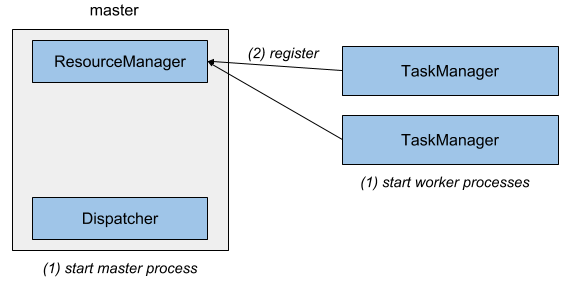

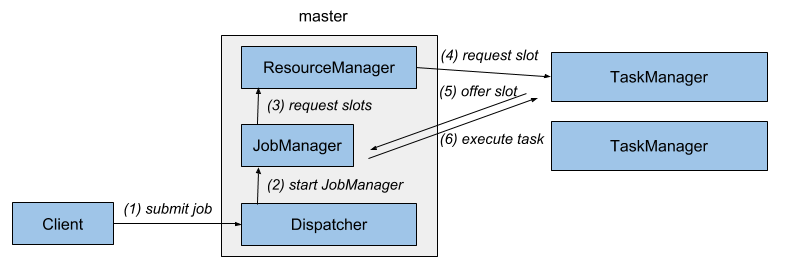

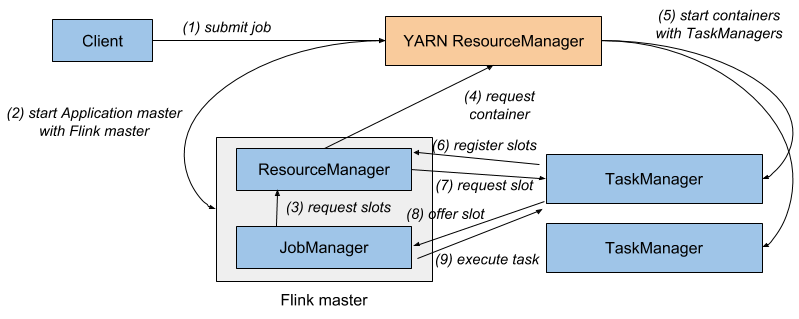

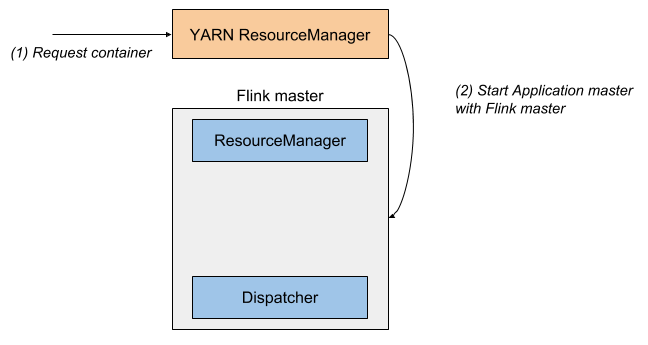

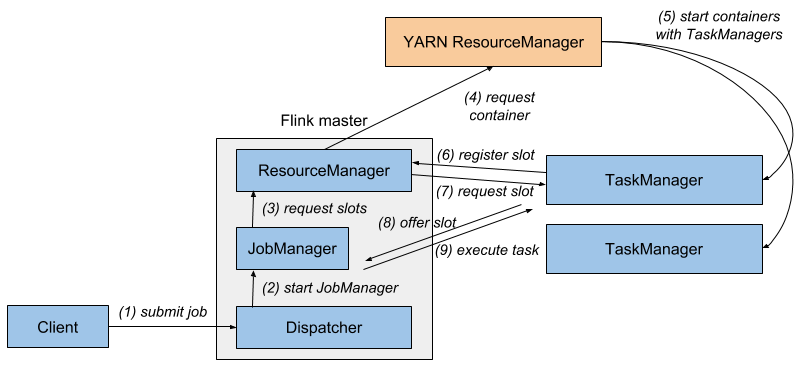

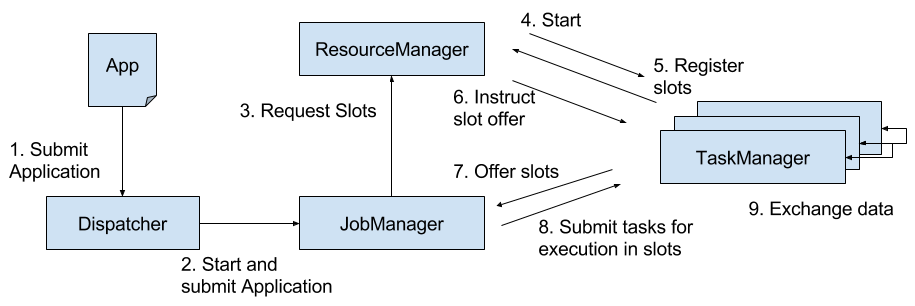

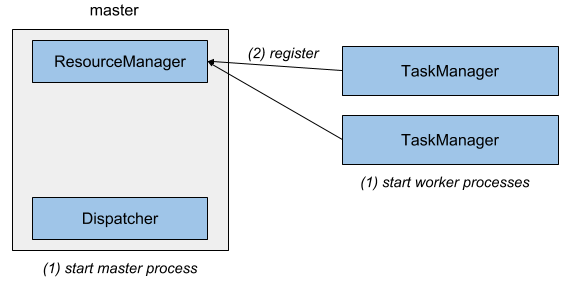

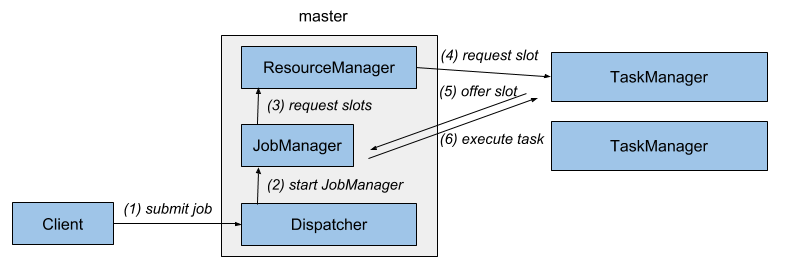

A Flink setup consists for four different components that work together to execute streaming applications. These components are a JobManager, a ResourceManager, a TaskManager, and a Dispatcher. Since Flink is implemented in Java and Scala, all components run on a Java Virtual Machine (JVM). We discuss the responsibilities of each component and how it interacts with the other components in the following.

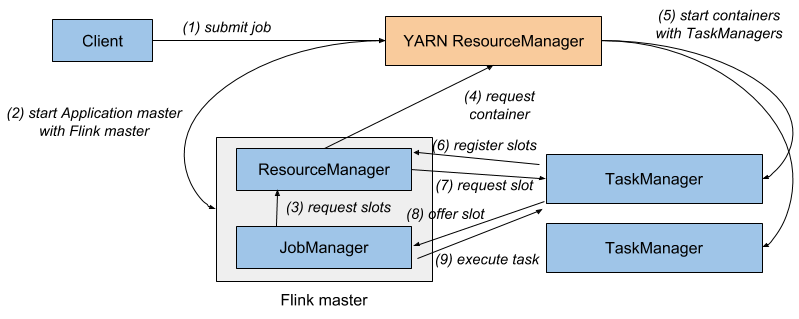

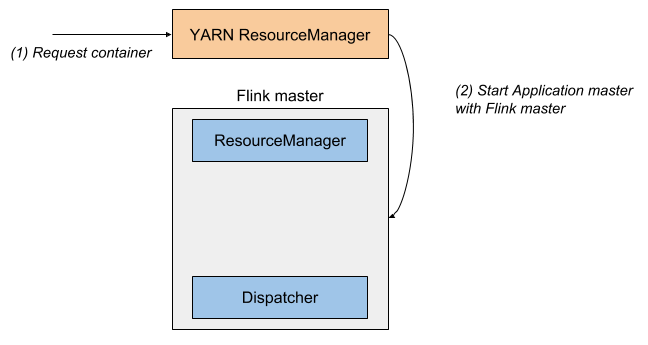

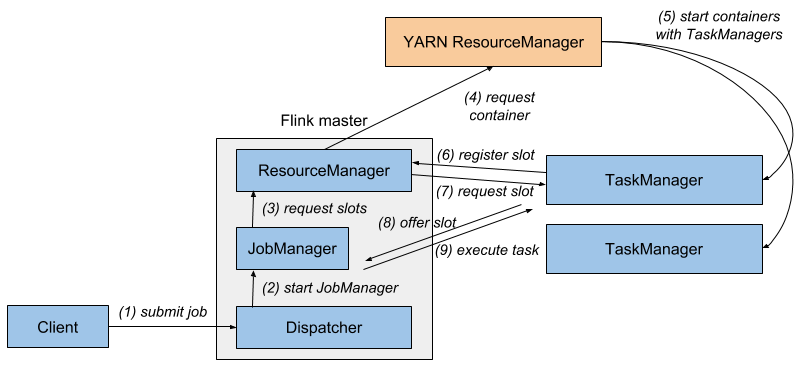

Please note that Figure 3-1 is a high-level sketch to visualize the responsibilities and interactions of the components. Depending on the the environment (YARN, Mesos, Kubernetes, stand-alone cluster), some steps can be omitted or components might run in the same process. For instance, in a stand-alone setup, i.e., a setup without a resource provider, the ResourceManager can only distribute the slots of manually started TaskManagers and cannot start new TaskManagers. In Chapter 9, we will discuss how to setup and configure Flink for different environments.

Flink applications can be deployed in two different styles.

The framework style is follows the traditional approach of submitting an application (or query) via a client to a running service. In the library mode, there is no Flink service continuously running. Instead, Flink is bundled as a library together with the application in a container image. This deployment mode is also common for microservice architectures. We discuss the topic of application deployment in more detail in Chapter 10.

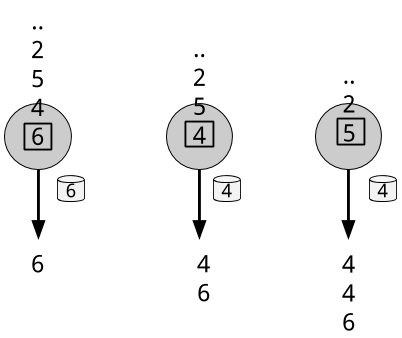

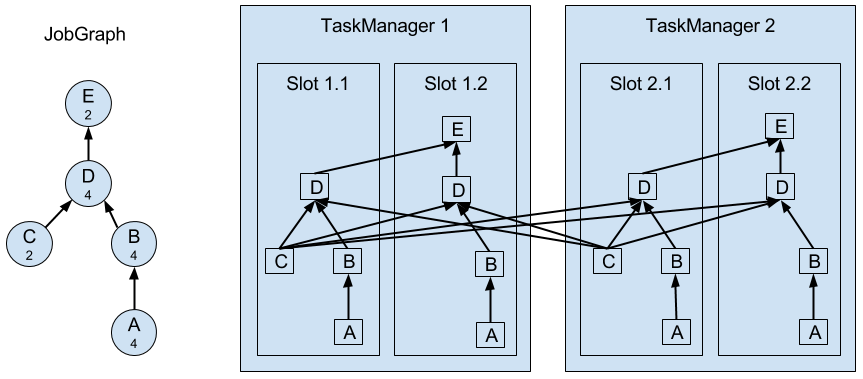

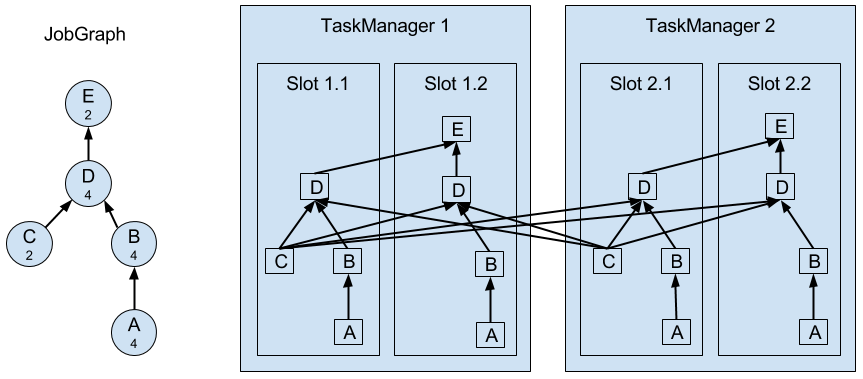

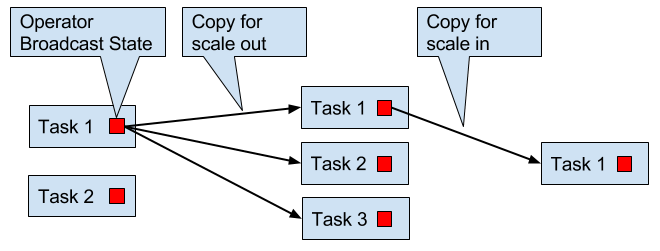

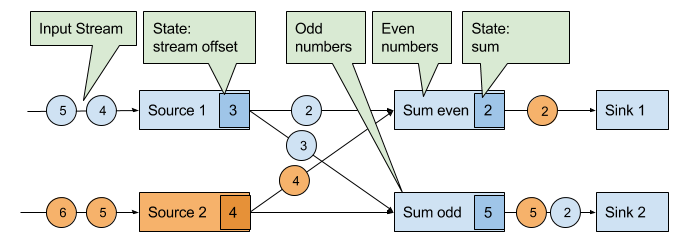

A TaskManager can execute several tasks at the same time. These tasks can be of the same operator (data parallelism), a different operator (task parallelism), or even from a different application (job parallelism). A TaskManager provides a certain number of processing slots to control the number of tasks that it can concurrently execute. A processing slot is able to execute one slice of an application, i.e., one task of each operator of the application. Figure 3-2 visualizes the relationship of TaskManagers, slots, tasks, and operators.

On the left hand side you see a JobGraph - the non-parallel representation of an application - consisting of five operators. Operators A and C are sources and operator E is a sink. Operators C and E have a parallelism of two. The other operators have a parallelism of four. Since the maximum operator parallelism is four, the application requires at least four available processing slots to be executed. Given two TaskManagers with two processing slots each, this requirement is fulfilled. The JobManager parallelizes the JobGraph into an ExecutionGraph and assigns the tasks to the four available slots. The tasks of the operators with a parallelism of four are assigned to each slot. The two tasks of operators C and E are assigned to slots 1.1 and 2.1 and slots 1.2 and 2.2, respectively1. Scheduling tasks as slices to slots has the advantage that many tasks are co-located on the TaskManager which means that they can efficiently exchange data without accessing the network.

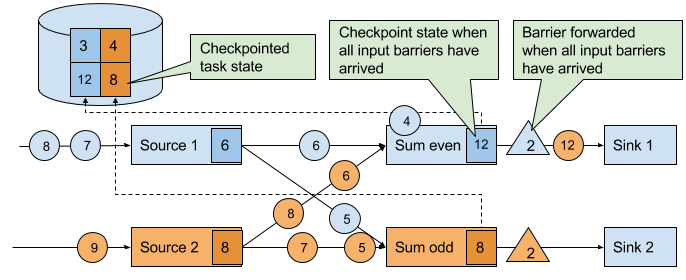

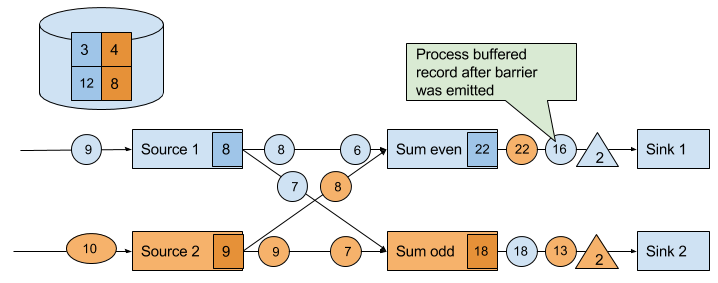

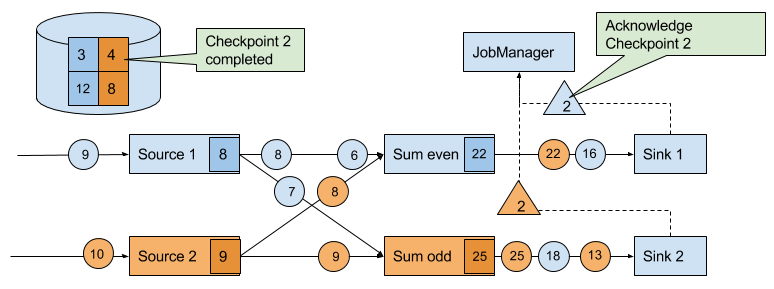

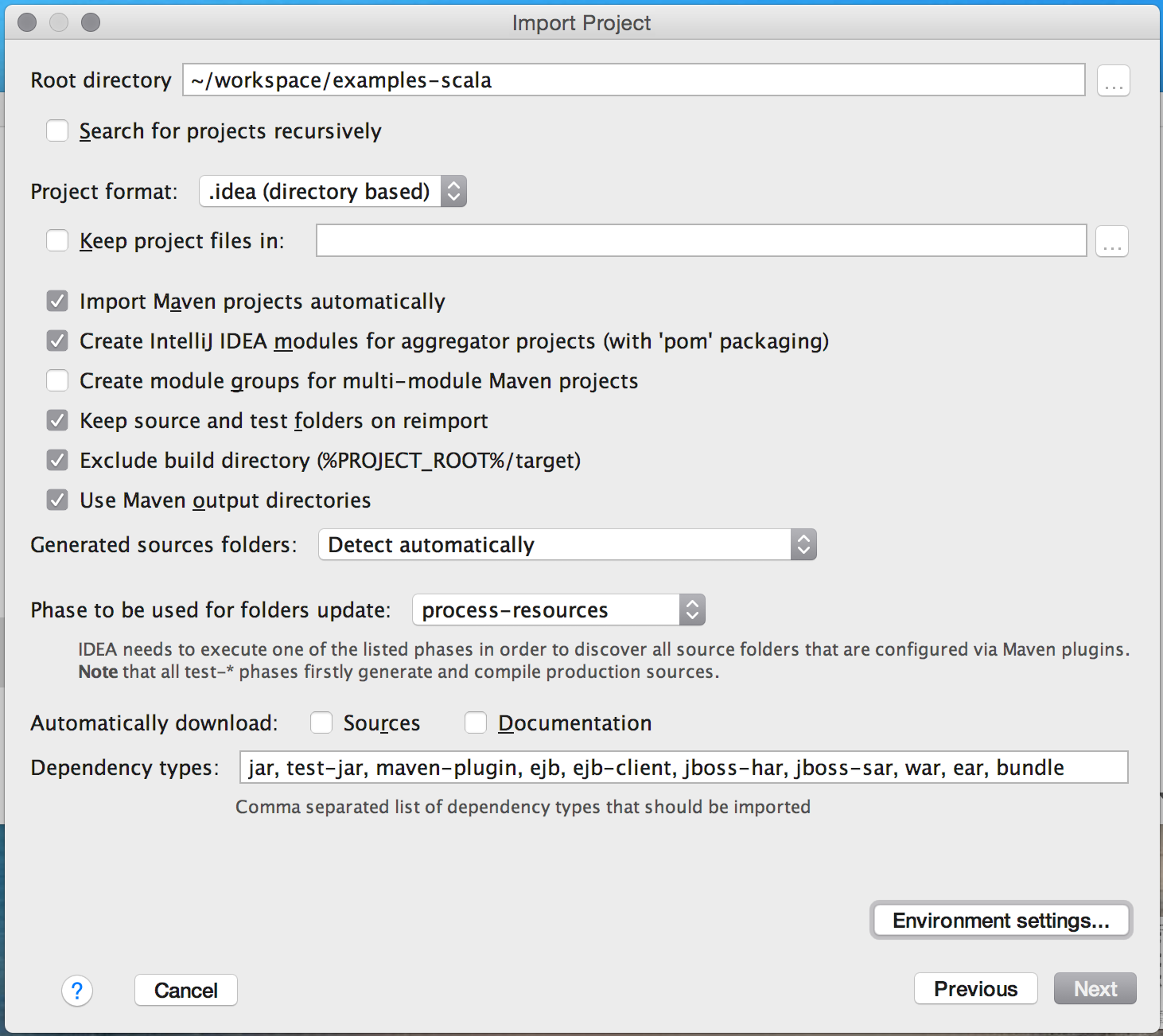

A TaskManager executes its tasks multi-threaded in the same JVM process. Threads are more lightweight than individual processes and have lower communication costs but do not strictly isolate tasks from each other. Hence, a single misbehaving task can kill the whole TaskManager process and all tasks which run on the TaskManager. Therefore, it is possible to isolate applications across TaskManagers, i.e., a TaskManager runs only tasks of one application. By leveraging thread-parallelism inside of a TaskManager and the option to deploy several TaskManager processes per host, Flink offers a lot of flexibility to trade off performance and resource isolation when deploying applications. We will discuss the configuration and setup of Flink clusters in detail in Chapter 9.