Chapter 3. Identity Security Fundamentals

After discussing the ongoing issues with current security models in the first chapter and introducing secure passwords, hashing, and salting in the second chapter, we now focus on using a person’s identity across multiple sites to handle different authentication and authorization scenarios.

Merriam-Webster defines identity as “the qualities, beliefs, etc., that make a particular person or group different from others.” These qualities are what make identity relevant to the concept of security.

Understanding Various Identity Types

While using the Internet, an individual establishes an online identity that represents certain elements or characteristics of that person. This form of identity can—and often will—differ across multiple sites and leads to a fragmentation that we can group into different areas based on a website’s use case.

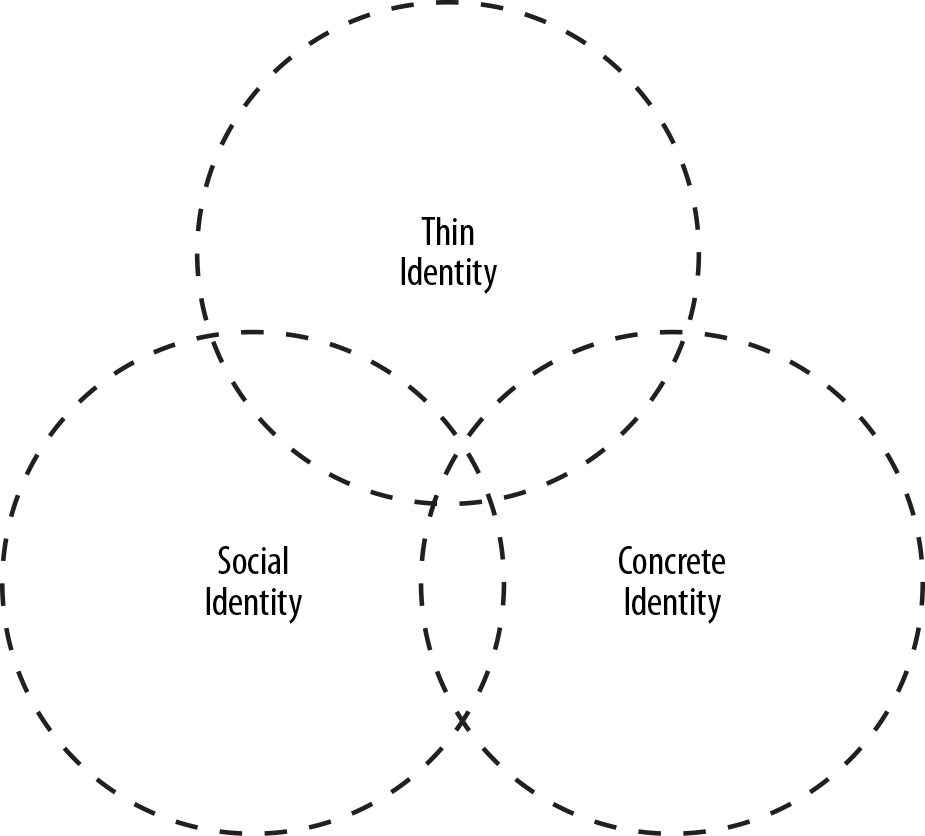

In this section, we introduce three types of identity that we will then discuss in detail: social identity, concrete identity, and thin identity. These types of identity often overlap and can share the same attributes, as shown in Figure 3-1.

These three identity types can be considered federated identities and are applied through technologies such as SAML, OpenID, OAuth, and tokenization. Often applied through single sign-on—known as SSO—Federated Identity Management (FIM or FIdM) is the practice of using a set of identity attributes across multiple systems or organizations. While SSO is a way of using the same credentials across multiple sites and applications, FIM shifts the verification of credentials toward the identity provider.

Figure 3-1. Overlapping identities

Social Identity

Social identity came up with the rise of social networks and can be seen as a very moderate form of identity that people tend to share quite casually. Profile information often concentrates on social connections, interests, and hobbies, while ignoring or not necessarily favoring critical information that might be used against the user.

Services such as Facebook or Google+ allow users to quickly access other services by using their already populated profiles and leverage scopes in order to control the level of information shared. This quickly became a favored way of handling login scenarios, especially on mobile phones, because it provides a big boost in convenience and helps to avoid the issues of entering any kind of complex information on touchscreens.

Concrete Identity

Leveraging social identity is completely valid and even encouraged for services such as games, media consumption, and of course, social networks. But other use cases such as online banking or ecommerce require a more concrete profile that provides useful information—for example, the user’s email, address, phone number, spoken languages, or age.

Especially in ecommerce scenarios, the payment process can be painful. Having to enter a 16+ digit credit card number manually can be tedious on a physical device and troublesome on a touchscreen. This is where services such as PayPal, Amazon Payments, or Google Wallet come in. These services enable users to enter valuable information in one place, and reuse it on multiple sites. By tokenizing sensible credentials such as payment details, the checkout flow is sped up tremendously.

Another popular example of using concrete identity is in the election process and many other state services. For example, in Lithuania, a citizen’s state-issued ID card is backed up by OpenID.1 This enables a form of eGovernment that allows people living remotely to participate in ongoing discussions and actively contribute to the country’s politic environment.

Thin Identity

Thin identity is an old concept that is currently gaining popularity again. Thin identity—or even no identity—simply means user authentication without gaining access to profile information.

A good example is Twitter’s service Digits, which allows users to use their phone number as a means of logging in. The identifying—and globally unique—bit here is the person’s phone number. Looking at the definition of identity introduced at the beginning of this chapter, the criterion of difference (from other phone numbers) is certainly met. Digits and other similar services aim to replace error-prone and vulnerable passwords with another factor that seems to be universally given. Yahoo! went a similar route and provided a way to do passwordless login using text messages with one-time-only passwords2—this is not yet part of Yahoo!’s developer offerings, though.

Enhancing User Experience by Utilizing Identity

User experience studies carried out by the Nielsen Norman Group show that login doesn’t necessarily have to be the first point of contact for users and often harms the conversion process of turning visitors into users by forcing them to register or log in.3 The current sentiment in user-experience research is that a preview of offered functionality is desirable and helps people decide whether they want to commit to an application.

Leveraging existing profiles, such as a user’s social identity, can help ease the way after the user does decide to register by prepopulating profile information and therefore lowering the amount of information the user has to type in manually.

Introducing Trust Zones

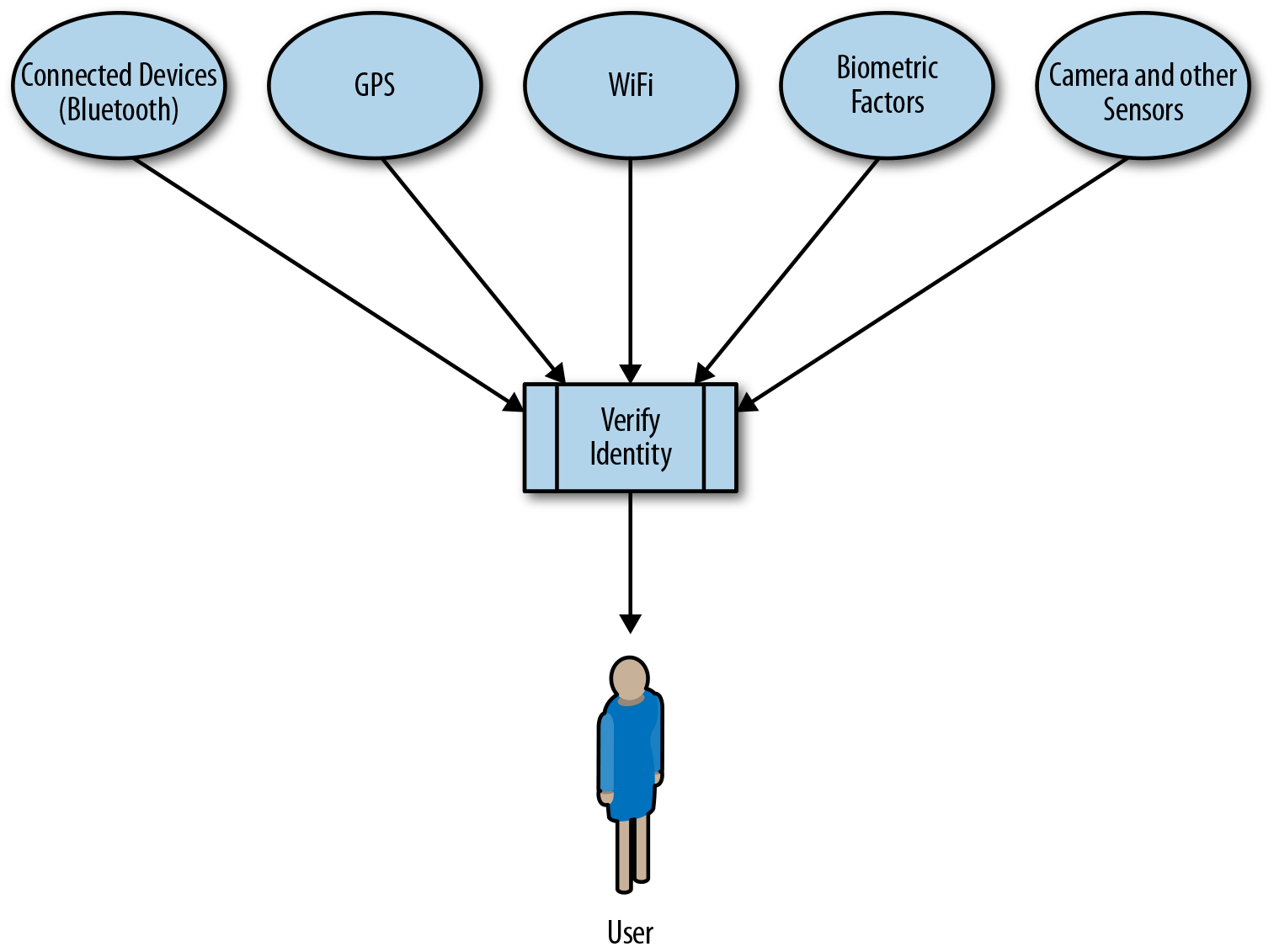

The devices we use nowadays come pre-equipped with a variety of sensors that can gather information about the user’s environment. GPS, WiFi, cameras, accelerometers, gyroscopes, light, and many other sensors are used to build up profiles and identify the user accordingly. Combining this concept with the concept of identity, we can not only identify users, but also build up trust zones (Figure 3-2).

Figure 3-2. Trust zones

Trust zones allow us to scale our security based on users’ behavior, environment, and our ability to determine whether they are who they say they are. In essence, we are trying to create a digital fingerprint for the user, from any data that might be available and unique for the given user, such as their browser configuration, hardware, devices, location, etc.

If we can guarantee a user is at home, based on the current GPS coordinates and the WiFi used to connect to the Internet, trust zones can offer the user a way to waive certain steps within authorization and authentication of web and mobile applications. Google introduced this concept for Android as a feature known as Smart Lock.4 When a user wears his Android Wear device, the phone can be set up to automatically unlock whenever a Bluetooth connection between the wearable device and the user’s phone is established.5 Other supported factors for Smart Lock are the user’s location, face recognition, and on-body detection, which is a feature that relies on the device’s accelerometer. Chapter 5 covers these alternate ways of user authentication more deeply.

Realistically, we’re trying to remove hurdles during the application experience for the users. If we can obtain enough bits of information about them from the system and devices that they are using to determine that they are almost certainly who they say they are, and they are in a trusted location, is it necessary to challenge them when changing account information, or ask them to provide login details during a checkout process instead of providing a one-click checkout experience?

These are the types of things that we can do when we have a strong certainty that users are who they are purporting to be.

Let’s take this conversation into a practical look at this technology, starting with the browser.

Browser Fingerprinting

One of our main goals as application and web developers is to make the experience of our users as secure and as convenient as possible. With the concept of trust zones understood, you can start to see how many of the security measures that we can put in place may occur without burdening the user for more information.

One of the methods that can be employed is browser fingerprinting. This process uses unique characteristics about the browser that the user is using, such as headers, fonts, etc., to determine a second factor of authentication based on the user’s browser.

Back in May of 2010, The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) published a report from an experiment it was running on browser fingerprinting, called Panopticlick. From this study, some interesting results were derived from the browsers that were tested during the first 1 million visits to the Panopticlick site.6

-

84% of browsers tested had a unique configuration.

-

Among browsers that had Flash or Java installed, 94% were unique.

-

Only 1% had fingerprints that were seen more than twice.

These are obviously not definitive numbers to determine to a near certainty the browser uniqueness of each user, but the numbers are significant enough to be able to easily use these types of tests as a second factor of authentication for our users. When we are able to find a unique browser configuration, we have a high likelihood (99%) of determining that the browser is unique and attributable to that individual. When using this, coupled with additional techniques that we will explore in later sections, we can predict with a high degree of certainty that users are who they say they are. When we have that determination, along with the login mechanisms that the user has used (such as a username/password), then we are able to maintain a high level of confidence to create our trust zones.

These tests used the concept of bits of entropy to determine the fingerprint of a browser. From its subset of tests, the EFF noticed that the distribution of entropy observed on a tested browser is typically around 18.1 bits. This means that if a browser was chosen at random, at best we would expect that only 1 in 286,777 other browsers would share the same fingerprint.

In addition to making things easier for the user through these trust zones, there’s another benefit to having this information tracked. If we are processing payments for our users, inevitably there will be some disputes over a payment and who may have made it. Being able to provide information such as these digital fingerprints during dispute resolution can help to provide favorable results during the process.

Configurations More Resistant to Browser Fingerprinting

In its study, the EFF also noticed that certain configurations had a high resistance to browser fingerprinting, meaning that they were harder to generate a fingerprint for. These configurations included the following:

-

Browsers with JavaScript, or disabled plug-ins.

-

Browsers with TorButton installed, which anticipated and defended against the fingerprinting techniques.

-

Mobile devices, because the lack of configurability of the mobile browser tends to lead to a more generic fingerprint. These devices generally do not have good interfaces for controlling cookies, so information may be obtained more easily through that method.

-

Corporate desktop machines that are precise clones of one another, and don’t allow for degrees of configuration.

-

Browsers running in anonymous mode.

Identifiable Browser Information

Through the studies that were performed during the Panopticlick project, the EFF was able to assign different entropy bit levels for different configuration types that can be derived from a browser. These included the characteristics and associated entropy values listed in Table 3-1.

| Characteristic | Bits of entropy |

|---|---|

User Agent |

10.0 |

Plug-ins |

15.4 |

Fonts |

13.9 |

Video |

4.83 |

Supercookies |

2.12 |

HTTP ACCEPT Header |

6.09 |

Time Zone |

3.04 |

Cookies Enabled |

0.353 |

The browser uniqueness report, in addition to providing the characteristics, also provided the means through which those values were obtained,7 as shown in Table 3-2.

| Characteristic | Method |

|---|---|

User Agent |

This was transmitted via HTTP, and logged by the server. It contains the browser micro-version, OS version, language, toolbar information, and other information on occasion. |

Plug-ins |

The PluginDetect JavaScript library was used to check eight common plug-ins. Extra code was also used to estimate the current version of Acrobat Reader. The data was then transmitted via AJAX post. |

Fonts |

A flash or Java applet was used, and the data was collected via JavaScript and transmitted via AJAX post. |

HTTP ACCEPT Header |

Transmitted by HTTP and logged by the server. |

Screen Resolution |

JavaScript AJAX post. |

Supercookies (partial test) |

JavaScript AJAX post. |

Time Zone |

JavaScript AJAX post. |

Cookies Enabled |

Inferred in HTTP, and logged by the server. |

Looking at a breakdown of all characteristics, we have a good idea of how to implement these techniques. For the most part, we’re pulling data via JavaScript and logging on our server, and at most (in the case of fonts), we have a flash or Java applet doing the work for us.

Capturing Browser Details

Let’s take a look at the methods that we can use to begin capturing some of this information from client-side JavaScript. This will be part of the data that we will need in order to start generating a fingerprint for our users, as they come through.

User agent

Let’s start with a simple one, the user agent. This will provide us with quite a bit of information that we can use for the overall fingerprint.

To obtain this string, we can use the data within the navigator object, like so:

var agent = navigator.userAgent;

From this test, you may see a string returned that would look something like the following:

Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_10_5) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/48.0.2564.116 Safari/537.36

There are some important pieces of information contained in this string that we can use. Specifically:

- Mozilla/5.0

-

Mozilla-compatible user agent and version. This is used for historical reasons, and has no real meaning in modern browsers.

- Intel Mac OS X 10_10_5

-

The operating system and version.

- AppleWebKit/537.36

-

Web kit and build.

- KHTML, like Gecko

-

Open source HTML layout engine (KHTML), like Gecko.

- Chrome/48.0.2564.116

-

Browser (Chrome) and version.

- Safari/537.36

-

Based on browser (Safari) and build.

Time zone

Next, let’s capture the time zone by using getTimezoneOffset(). This function will return the offset, in minutes, from GMT. To obtain the number of hours that the user is offset from GMT, we can divide that result by 60, like so:

var offset = new Date().getTimezoneOffset() / 60;

You may notice something strange about the result here. The hour is correct, but the negative/positive identifier is flipped. For instance, if I am on the East Coast of the United States (GMT-5), the result returned is 5, not –5. This is because getTimezoneOffset() is calculating GMT’s offsite from your time zone, not the other way around. If you wish to have it the other way around, multiply by –1, like so:

var offset = (new Date().getTimezoneOffset() / 60) * -1;

Screen resolution

The screen resolution can be obtained by using the window object. This will give us the screen resolution of the monitor being used, which can be a fairly static indicator for the browser fingerprint.

We can obtain those results with the following snippets:

var width = window.screen.width; var height = window.screen.height;

This will give us the given numeric results for the width and height, such as 2560 (width) and 1440 (height) for a screen resolution of 2560 x 1440.

Plug-ins

Browser plug-in information can garner quite a bit of detail for the fingerprint, and is obtained via navigator.plugins. Let’s say we want to capture the name of each plug-in installed in the browser, and just display those for the time being. We can do so with the following code:

//get plugin information

var plugins = navigator.plugins;

for (var i = 0; i < plugins.length; i++){

console.log(plugins[i].name);

}

JavaScript Library for Plug-in Detection

An alternative method for obtaining additional plug-in information from the browser is through the PluginDetect JavaScript library.

The information displayed, depending on the plug-ins installed in the browser, may look something like the following:

Widevine Content Decryption Module Chrome PDF Viewer Shockwave Flash Native Client

That information can be added to the custom identifiers for the user’s browser.

Location-Based Tracking

Other than browser fingerprinting, another method that we can use for building trust zones for users is to use their physical location.

Here’s how this can be valuable. Let’s say that we have an ecommerce store where the user has filled out her shipping address during sign-up or a previous purchase. We have that address stored to make it easier for the user to check out, and that has become a trusted home location. If we could determine the physical location of the person attempting to use the site while purporting to be the user, we could match that against the address on file. If those two addresses match, we can use that as a trusted point, and potentially lift the need to have the user confirm her login information before checkout.

Use Geolocation with Caution

Use gelocation data from the user with caution. Physical location can be masked, and may provide inaccurate results. With that said, ensure that you use alternate methods of identification with geolocation, and use with caution.

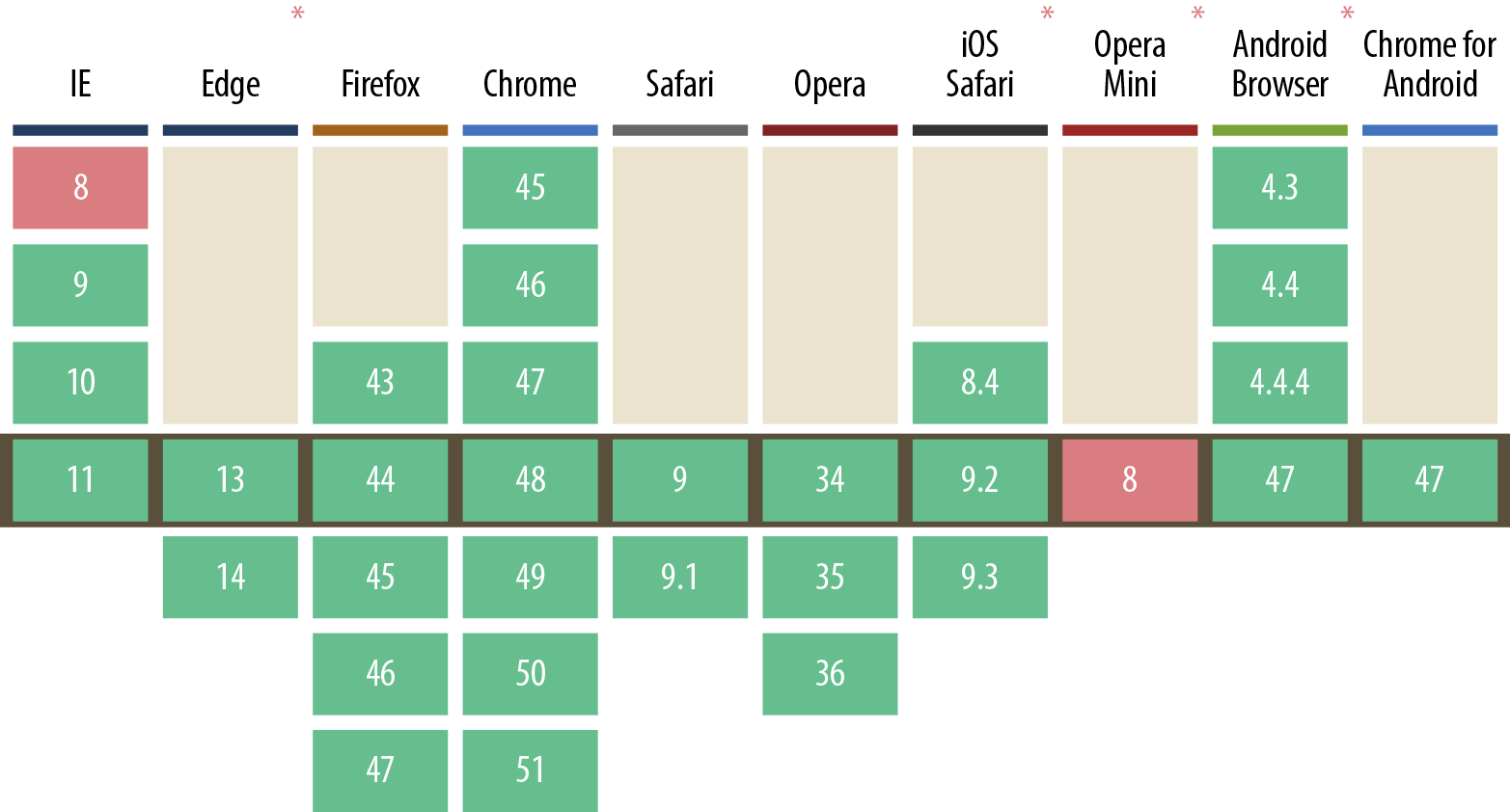

Let’s look at a simple JavaScript-based approach to gathering the latitude and longitude of the user, using the navigator object. First, let’s see what the current support for geolocation is within modern browsers (Figure 3-3).

Figure 3-3. Current geolocation browser support

Looking at the support, we have good overall coverage in most modern browsers. Now let’s see how to set up a simple example of this:

//on success handler

function success(position){

console.log('lat: ' + position.coords.latitude);

console.log('lon: ' + position.coords.longitude);

}

//error handler

function failure(err){

console.log(err);

}

//check geolocation browser availability and capture coordinates

if ('geolocation' in navigator){

navigator.geolocation.getCurrentPosition(success, failure, {timeout:10000});

} else {

console.log('geolocation is not available');

}

We start out by defining two handler functions, one for success and the other for handling errors. Within the success function we will be passed position data, from which we can then extract coordinate information. Within the error handler, we are simply logging out the errors that may be produced. One potential error may be caused by the user not allowing the website to capture his geolocation:

PositionError {}

- code: 1

- message: "User denied Geolocation"

With those in place, we check at the bottom of the sample to see whether geolocation is available within the navigator object. If it is, we call navigator.geolocation.getCurrentPosition(…), passing in the success function, error function, and the options, which contain a time-out of 10 seconds.

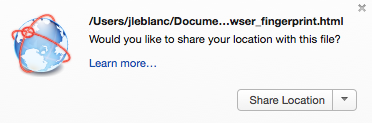

When run in a browser, the user will be asked to confirm his geolocation data (Figure 3-4).

Figure 3-4. Requesting use of geolocation data

Once allowed, we will be able to extract the latitude and longitude, compare those to the address we have stored on file, and see whether the user is in a trusted zone. Creating a geofence of an appropriate range (range from the root address that the coordinates are within) will allow us to handle cases of the user being within close proximity to his home location.

Device Fingerprinting (Phone/Tablet)

As you can see, a multitude of data points can be gathered to help us determine whether users are who they say they are, without impacting their experience. This allows us to continue to make things easier by not having to request additional information from them for security.

Another method is to use the hardware fingerprint of the devices that are being used by the person using our site or service. Users will typically use a range of devices (phones, tablets, etc.) for interacting with your applications. These devices, when used over time, can become trusted sources to help determine whether the user is on a trusted device.

Let’s take a look at a simple method for capturing this type of information from an Android application. Build information is available that enable us to obtain information about the device that the user is using.8

Some of that information can be pulled like so:

//Build Info: http://developer.android.com/reference/android/os/Build.html

System.getProperty("os.version"); //os version

android.os.Build.DEVICE //device

android.os.Build.MODEL //model

android.os.Build.VERSION.SDK_INT //sdk version of the framework

android.os.Build.SERIAL //hardware serial number, if available

.

.

.

We can obtain information such as the OS version, device, and model. This can all go toward building a framework of trusted devices, and allowing a user to bypass the need for additional levels of security, should they be required.

Changing Devices

A typical question here may be, “What if I change my device?” If a device is changed, the system should note that the device is not trusted, and show appropriate security challenges as one would for an untrusted user. Once the user has verified her identity through the challenges, that device can then be added to the list of trusted devices.

Device Fingerprinting (Bluetooth Paired Devices)

Today our phones are not the only connected devices we have. We may have our phones connected to a smart watch, a car, or other hardware around us. These devices, much like the phone, can be used as a hardware fingerprint to help determine whether users are who they say they are. If we can find devices that are typically connected to the phone, the trust score would increase.

Let’s look at an example of how this would work within an Android application, if we wanted to fetch all of the Bluetooth devices that are connected to a phone:

//fetch all bonded bluetooth devices

Set<BluetoothDevice> pairedDevices = mBluetoothAdapter.getBondedDevices();

//if devices found, fetch name and MAC address for each

if (pairedDevices.size() > 0){

for (BluetoothDevice device : pairedDevices){

//Device Name - device.getName()

//Device MAC address - device.getAddress()

}

}

We start by calling getBondedDevices() to capture any devices that are currently attached to the phone. We then loop through the devices found, and can fetch some basic information about them:

- Device name

-

Readable name of the device, obtained through

device.getName() - MAC address

-

The physical address of the device, obtained through

device.getAddress()

Setting Proper Permissions

As of Android 6.0, there have been permission changes to provide users with greater data protection. In order to obtain hardware identifiers (such as the MAC address) of a Bluetooth-attached device, you need to set the ACCESS_FINE_LOCATION or ACCESS_COARSE_LOCATION permissions in your app. If those permissions are not set, device.getAddress() will return a constant value of 02:00:00:00:00:00.9

Implementing Identity

Now that you have built up an understanding of identity types and the concepts behind trust zones, in Chapter 4 we will take on a basic implementation of OAuth 2.0 and OpenID—the driving technologies behind identity. Please note that the identity sector is currently evolving, and new standards, such as FIDO, are on the horizon. These new technologies will be part of Chapter 5’s focus.

1 http://lists.openid.net/pipermail/openid-eu/2009-February/000280.html

2 http://www.infopackets.com/news/9545/new-yahoo-login-system-uses-no-password

3 https://www.nngroup.com/articles/login-walls

4 http://developers.google.com/identity/smartlock-passwords/android

5 http://support.google.com/nexus/answer/6093922?hl=en

6 https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2010/05/every-browser-unique-results-fom-panopticlick

7 https://panopticlick.eff.org/static/browser-uniqueness.pdf

8 http://developer.android.com/reference/android/os/Build.html

9 http://developer.android.com/about/versions/marshmallow/android-6.0-changes.html