Chapter 5. Reading Great Code

Programmers read a lot of code. One of the core tenets behind Python’s design is readability, and one secret to becoming a great programmer is to read, understand, and comprehend excellent code. Such code typically follows the guidelines outlined in “Code Style” and does its best to express a clear and concise intent to the reader.

This chapter shows excerpts from some very readable Python projects that illustrate topics covered in Chapter 4. As we describe them, we’ll also share techniques for reading code.1

Here’s a list of projects highlighted in this chapter in the order they will appear:

-

HowDoI is a console application that searches the Internet for answers to coding questions, written in Python.

-

Diamond is a Python daemon2 that collects metrics and publishes them to Graphite or other backends. It is capable of collecting CPU, memory, network, I/O, load and disk metrics. Additionally, it features an API for implementing custom collectors to gather metrics from almost any source.

-

Tablib is a format-agnostic tabular dataset library.

-

Requests is a HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP) library for human beings (the 90% of us who just want an HTTP client that automatically handles password authentication and complies with the half-dozen standards to perform things like a multipart file upload with one function call).

-

Werkzeug started as a simple collection of various utilities for Web Service Gateway Interface (WSGI) applications and has become one of the most advanced WSGI utility modules.

-

Flask is a web microframework for Python based on Werkzeug and Jinja2. It’s good for getting simple web pages up quickly.

There is a lot more to all of these projects than what we’re mentioning, and we really, really hope that after this chapter you’ll be motivated to download and read at least one or two of them in depth yourself (and maybe even present what you learn to a local user group).

Common Features

Some features are common across all of the projects: details from a snapshot of each one show very few (fewer than 20, excluding whitespace and comments) lines of code on average per function, and a lot of blank lines. The larger, more complex projects use docstrings and/or comments; usually more than a fifth of the content of the code base is some sort of documentation. But we can see from HowDoI, which has no docstrings because it is not for interactive use, that comments are not necessary when the code is straightforward. Table 5-1 shows common practices in these projects.

| Package | License | Line count | Docstrings (% of lines) |

Comments (% of lines) |

Blank lines (% of lines) |

Average function length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

HowDoI |

MIT |

262 |

0% |

6% |

20% |

13 lines of code |

Diamond |

MIT |

6,021 |

21% |

9% |

16% |

11 lines of code |

Tablib |

MIT |

1,802 |

19% |

4% |

27% |

8 lines of code |

Requests |

Apache 2.0 |

4,072 |

23% |

8% |

19% |

10 lines of code |

Flask |

BSD 3-clause |

10,163 |

7% |

12% |

11% |

13 lines of code |

Werkzeug |

BSD 3-clause |

25,822 |

25% |

3% |

13% |

9 lines of code |

In each section, we use a different code-reading technique to figure out what the project is about. Next, we single out code excerpts that demonstrate ideas mentioned elsewhere in this guide. (Just because we don’t highlight things in one project doesn’t mean they don’t exist; we just want to provide good coverage of concepts across these examples.) You should finish this chapter more confident about reading code, with examples that reinforce what makes good code, and with some ideas you’d like to incorporate in your own code later.

HowDoI

With fewer than 300 lines of code, The HowDoI project, by Benjamin Gleitzman, is a great choice to start our reading odyssey.

Reading a Single-File Script

A script usually has a clear starting point, clear options, and a clear ending point. This makes it easier to follow than libraries that present an API or provide a framework.

Get the HowDoI module from GitHub:3

$git clone https://github.com/gleitz/howdoi.git$virtualenv -p python3 venv# or use mkvirtualenv, your choice...$sourcevenv/bin/activate(venv)$cdhowdoi/(venv)$pip install --editable .(venv)$python test_howdoi.py# Run the unit tests.

You should now have the howdoi executable installed in venv/bin.

(You can look at it if you want by typing cat `which howdoi` on the

command line.)

It was auto-generated when you ran pip install.

Read HowDoI’s documentation

HowDoI’s documentation is in the README.rst file in the HowDoI repository on GitHub: it’s a small command-line application that allows users to search the Internet for answers to programming questions.

From the command line in a terminal shell, we can type howdoi --help for

the usage statement:

(venv)$howdoi --help usage: howdoi[-h][-p POS][-a][-l][-c][-n NUM_ANSWERS][-C][-v][QUERY[QUERY ...]]instant coding answers via thecommandline positional arguments: QUERY the question to answer optional arguments: -h, --help show thishelpmessage andexit-p POS, --pos POSselectanswer in specified position(default: 1)-a, --all display the full text of the answer -l, --link display only the answer link -c, --colorenablecolorized output -n NUM_ANSWERS, --num-answers NUM_ANSWERS number of answers toreturn-C, --clear-cache clear the cache -v, --version displays the current version of howdoi

That’s it—from the documentation we know that HowDoI gets answers to coding questions from the Internet, and from the usage statement we know we can choose the answer in a specific position, can colorize the output, get multiple answers, and that it keeps a cache that can be cleared.

Use HowDoI

We can confirm we understand what HowDoI does by actually using it. Here’s an example:

(venv)$howdoi --num-answers2python lambdafunctionlist comprehension --- Answer1---[(lambda x: x*x)(x)forx in range(10)]--- Answer2---[x()forx in[lambdam=m: mform in[1,2,3]]]# [1, 2, 3]

We’ve installed HowDoI, read its documentation, and can use it. On to reading actual code!

Read HowDoI’s code

If you look inside the howdoi/ directory, you’ll see it contains two files: an __init__.py, which contains a single line that defines the version number, and howdoi.py, which we’ll open and read.

Skimming howdoi.py, we see each new function definition

is used in the next function, making it is easy

to follow. And each function does just one thing—the thing

its name says.

The main function, command_line_runner(),

is near the bottom of howdoi.py.

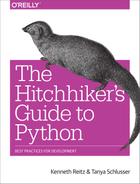

Rather than reprint HowDoI’s source here, we can illustrate its call structure using the call graph in Figure 5-1. It was created by Python Call Graph, which provides a visualization of the functions called when running a Python script. This works well with command-line applications thanks to a single start point and the relatively few paths through their code. (Note that we manually deleted functions not in the HowDoI project from the rendered image to legibly fit it on the page, and slightly recolored and reformatted it.)

Figure 5-1. Clean paths and clear function names in this howdoi call graph

The code could have been all one large, incomprehensible spaghetti function.

Instead, intentional choices structure the code into compartmentalized functions

with straightforward names.

Here’s a brief description of the execution depicted in Figure 5-1:

command_line_runner() parses the input and passes the user flags and

the query to howdoi(). Then, howdoi() wraps _get_instructions() in a

try/except statement so that it can catch connection errors

and print a reasonable error message (because application code

should not terminate on exceptions).

The primary functionality is in _get_instructions():

it calls _get_links() to do a Google search of Stack Overflow

for links that match the query, then calls _get_answer()

once for each resulting link (up to the number of links that the user

specified on the command line—the default is just one link).

The _get_answer() function follows a link to Stack Overflow,

extracts code from the answer, colorizes it, and returns it to

_get_instructions(), which will combine all of the answers

into one string, and return it.

Both _get_links() and _get_answer() call _get_result()

to actually do the HTTP request:

_get_links() for the Google query, and

_get_answer() for the resulting links from the Google query.

All _get_result() does is wrap requests.get() with a try/except

statement so that it can catch SSL errors, print an error message,

and re-raise the exception so that the top-level try/except

can catch it and exit. Catching all exceptions before exiting is best practice

for application programs.

Structure Examples from HowDoI

HowDoI is a small library, and we’ll be highlighting structure much more elsewhere, so there are only a few notes here.

Let each function do just one thing

We can’t reiterate enough how beneficial it is for readers to

separate out HowDoI’s internal functions to each do just one thing.

Also, there are functions whose sole purpose is to wrap other

functions with a try/except statement.

(The only function with a try/except that doesn’t follow this

practice is _format_output(), which leverages try/except

clauses to identify the correct coding language for syntax

highlighting, not for exception handling.)

Leverage data available from the system

HowDoI checks and uses relevant system values, such as

urllib.request.getproxies(), to handle the use of proxy servers

(this can be the case in organizations like schools that have

an intermediary server filtering the connection to the Internet),

or in this snippet:

XDG_CACHE_DIR=os.environ.get('XDG_CACHE_HOME',os.path.join(os.path.expanduser('~'),'.cache'))

How do you know that these variables exist?

The need for urllib.request.getproxies() is evident from the

optional arguments in requests.get()—so part of this

information comes from understanding the API of libraries you call.

Environment variables are often utility-specific, so if a library

is intended for use with a particular database or other sister application,

those applications’ documentation list relevant environment variables.

For plain POSIX systems, a good place to start is

Ubuntu’s list of default environment variables,

or else the base list of environment variables in the

POSIX specification,

which links to various relevant other lists.

Style Examples from HowDoI

HowDoI mostly follows PEP 8, but not pedantically, and not

when it restricts readability. For example, import statements

are at the top of the file, but standard library and external

modules are intermixed.

And although the string constants in USER_AGENTS are much

longer than 80 characters, there is no natural place to break

the strings, so they are left intact.

These next excerpts highlight other style choices we’ve previously advocated for in Chapter 4.

Underscore-prefixed function names (we are all responsible users)

Almost every function in HowDoI is prefixed with an underscore. This identifies them as

for internal use only. For most of them, this is because if called, there is the

possibility of an uncaught exception—anything that calls _get_result()

risks this—until the howdoi() function, which handles the possible exceptions.

The rest of the internal functions (_format_output(), _is_question(),

_enable_cache(), and _clear_cache()) are identified as such because

they’re simply not intended for use outside of the package.

The testing script, howdoi/test_howdoi.py, only calls the nonprefixed

functions, checking that the formatter works by feeding a command-line argument

for colorization to the top-level howdoi.howdoi() function, rather

than by feeding code to howdoi._format_output().

Handle compatibility in just one place (readability counts)

Differences between versions of possible dependencies are handled before the main code body so the reader knows there won’t be dependency issues, and version checking doesn’t litter the code elsewhere. This is nice because HowDoI is shipped as a command-line tool, and the extra effort means users won’t be forced to change their Python environment just to accommodate the tool. Here is the snippet with the workarounds:

try:fromurllib.parseimportquoteasurl_quoteexceptImportError:fromurllibimportquoteasurl_quotetry:fromurllibimportgetproxiesexceptImportError:fromurllib.requestimportgetproxies

And the following snippet resolves the

difference between Python 2 and Python 3’s

Unicode handling in seven lines, by creating the

function u(x) to either do nothing or emulate

Python 3. Plus it follows Stack Overflow’s new citation guideline, by citing the original

source:

# Handle Unicode between Python 2 and 3# http://stackoverflow.com/a/6633040/305414ifsys.version<'3':importcodecsdefu(x):returncodecs.unicode_escape_decode(x)[0]else:defu(x):returnx

Pythonic choices (beautiful is better than ugly)

The following snippet from howdoi.py

shows thoughtful, Pythonic choices. The function

get_link_at_pos() returns False if there are

no results, or else identifies the links that are

to Stack Overflow questions, and returns the

one at the desired position (or the last one if

there aren’t enough links):

def_is_question(link):returnre.search('questions/\d+/',link)# [ ... skip a function ... ]defget_link_at_pos(links,position):links=[linkforlinkinlinksif_is_question(link)]ifnotlinks:returnFalseiflen(links)>=position:link=links[position-1]else:link=links[-1]returnlink

The first function,

_is_question(), is defined as a separate one liner, giving clear meaning to an otherwise opaque regular expression search.

The list comprehension reads like a sentence, thanks to the separate definition of

_is_question()and meaningful variable names.

The early

returnstatement flattens the code.

The additional step of assigning to the variable

linkhere…

…and here, rather than two separate

returnstatements with no named variable at all, reinforces the purpose ofget_link_at_pos()with clear variable names. The code is self-documenting.

The single

returnstatement at the highest indentation level explicitly shows that all paths through the code exit either right away—because there are no links—or at the end of the function, returning a link. Our quick rule of thumb works: we can read the first and last line of this function and understand what it does. (Given multiple links and a position,get_link_at_pos()returns one single link: the one at the given position.)

Diamond

Diamond is a daemon (an application that runs continuously as a background process) that collects system metrics and publishes them to downstream programs like MySQL, Graphite (a platform open sourced by Orbitz in 2008 that stores, retrieves, and optionally graphs numeric time-series data), and others. We’ll get to explore good package structure, as Diamond is a multifile application, much larger than HowDoI.

Reading a Larger Application

Diamond is still a command-line application, so like with HowDoI, there’s still a clear starting point and clear paths of execution, although the supporting code now spans multiple files.

Get Diamond from GitHub (the documentation says it only runs on CentOS or Ubuntu, but code in its setup.py makes it appear to support all platforms; however, some of the commands that default collectors use to monitor memory, disk space, and other system metrics are not on Windows). As of this writing, it still uses Python 2.7:

$git clone https://github.com/python-diamond/Diamond.git$virtualenv -p python2 venv# It's not Python 3 compatible yet...$sourcevenv/bin/activate(venv)$cdDiamond/(venv)$pip install --editable .(venv)$pip install mock docker-py# These are dependencies for testing.(venv)$pip install mock# This is also a dependency for testing.(venv)$python test.py# Run the unit tests.

Like with the HowDoI library, Diamond’s setup script installs

executables in venv/bin/: diamond and diamond-setup.

This time they’re not automatically generated—they’re prewritten scripts in the project’s Diamond/bin/ directory.

The documentation says that diamond starts the server,

and diamond-setup is an optional tool to walk users through interactive

modification of the collector settings in the configuration file.

There are a lot of additional directories, and the diamond package is

underneath Diamond/src in this project directory. We are going to

look at files in Diamond/src (which contains the main code), Diamond/bin

(which contains the executable diamond), and Diamond/conf (which contains

the sample configuration file). The rest of the directories and files

may be of interest to people distributing similar applications but is

not what we want to cover right now.

Read Diamond’s documentation

First, we can get a sense of what the project is and what it does by scanning the online documentation. Diamond’s goal is to make it easy to gather system metrics on clusters of machines. Originally open sourced by BrightCove, Inc., in 2011, it now has over 200 contributors.

After describing its history and purpose, the documentation tells you how to install it, and then says how to run it: just modify the example configuration file (in our download it’s in conf/diamond.conf.example), put it in the default location (/etc/diamond/diamond.conf) or a path you’ll specify on the command line, and you’re set. There’s also a helpful section on configuration in the Diamond wiki page.

From the command line, we can get the usage statement via diamond --help:

(venv)$diamond --help Usage: diamond[options]Options: -h, --help show thishelpmessage andexit-c CONFIGFILE, --configfile=CONFIGFILE config file -f, --foreground run in foreground -l, --log-stdout log to stdout -p PIDFILE, --pidfile=PIDFILE pid file -r COLLECTOR, --run=COLLECTOR run a given collector once andexit-v, --version display the version andexit--skip-pidfile Skip creating PID file -u USER, --user=USER Change to specified unprivileged user -g GROUP, --group=GROUP Change to specified unprivileged group --skip-change-user Skip changing to an unprivileged user --skip-fork Skip forking(damonizing)process

From this, we know it uses a configuration file; by default, it runs in the background; it has logging; you can specifiy a PID (process ID) file; you can test collectors; you can change the process’s user and group; and it by default will daemonize (fork) the process.4

Use Diamond

To understand it even better, we can run Diamond. We need a modified configuration file, which we can put in a directory we make called Diamond/tmp. From inside the Diamond directory, type:

(venv)$mkdir tmp(venv)$cp conf/diamond.conf.example tmp/diamond.conf

Then edit tmp/diamond.conf to look like this:

### Options for the server[server]# Handlers for published metrics.handlers=diamond.handler.archive.ArchiveHandleruser=group=# Directory to load collector modules fromcollectors_path=src/collectors/### Options for handlers[handlers][[default]][[ArchiveHandler]]log_file=/dev/stdout### Options for collectors[collectors][[default]]# Default Poll Interval (seconds)interval=20### Default enabled collectors[[CPUCollector]]enabled=True[[MemoryCollector]]enabled=True

We can tell from the example configuration file that:

There are multiple handlers, which we can select by class name.

We have control over the user and group that the daemon runs as (empty means to use the current user and group).

We can specify a path to look for collector modules. This is how Diamond will know where the custom

Collectorsubclasses are: we directly state it in the configuration file.

We can also store configure handlers individually.

Next, run Diamond with options that set logging to /dev/stdout (with default formatting configurations), that keep the application in the foreground, that skip writing the PID file, and that use our new configuration file:

(venv)$diamond -l -f --skip-pidfile --configfile=tmp/diamond.conf

To end the process, type Ctrl+C until the command prompt reappears.

The log output demonstrates what collectors and handlers do:

collectors collect different metrics (such as the MemoryCollector’s

total, available, free, and swap memory sizes),

which the handlers format and send to various destinations,

such as Graphite, MySQL, or in our test case,

as log messages to /dev/stdout.

Reading Diamond’s code

IDEs can be useful when reading larger projects—they can quickly locate the original definitions of functions and classes in the source code. Or, given a definition, they can find all places in the project where it is used. For this functionality, set the IDE’s Python interpreter to the one in your virtual environment.5

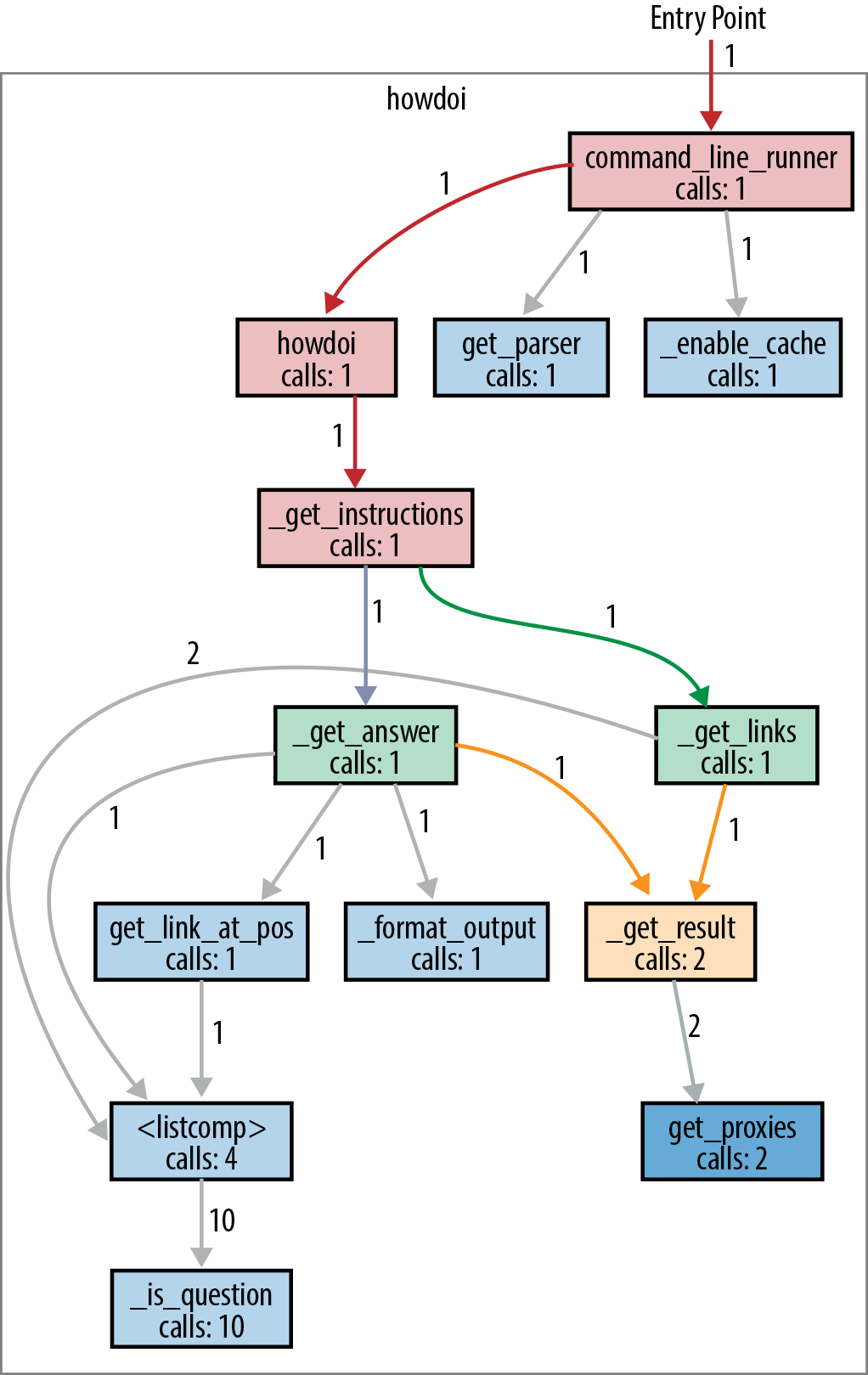

Instead of following each function as we did with HowDoI,

Figure 5-2 follows the import statements;

the diagram just shows which modules in Diamond import which other modules.

Drawing sketches like these helps by providing a very high-level look

for larger projects: you hide the trees so you can see the forest.

We can start with the diamond executable file on the top left

and follow the imports through the Diamond project.

Aside from the diamond executable, every square outline denotes a

file (module) or directory (package) in the src/diamond directory.

Figure 5-2. The module import structure of Diamond

Diamond’s well-organized and appropriately named modules make it possible to

get an idea of what the code is doing solely from our diagram:

diamond gets the version from util, then sets up logging using utils.log

and starts a Server instance using server. The Server imports from

almost all of the modules in the utils package, using utils.classes

to acess both the Handlers in handler and the collectors,

config to read the configuration file and obtain settings for the

collectors (and the extra paths to the user-defined collectors),

and scheduler and signals to set the polling interval for the

collectors to calculate their metrics, and to set up and start

the handlers processing the queue of metrics to send them to

their various destinations.

The diagram doesn’t include the helper modules convertor.py and

gmetric.py, which are used by specific collectors, or the over

20 handler implementations defined in the handler subpackage, or the

over 100 collector implementations defined in the project’s

Diamond/src/collectors/ directory (which is installed elsewhere

when not installed the way we did for reading—that is, using PyPI

or Linux package distributions, instead of source).

These are imported using diamond.classes.load_dynamic_class(),

which then calls the function diamond.util.load_class_from_name() to load the classes

from the string names given in the configuration file, so the import

statements do not explicitly name them.

To understand why there is both a utils package and a util

module, you have to dig into the actual code: the util module

provides functions related more to Diamond’s packaging than to

its operation—a function to get the version number from version.__VERSION__,

and two functions that parse strings that identify either

modules or classes, and import them.

Structure Examples from Diamond

Diamond is more than an executable application—it’s also a library that provides a way for users to create and use custom collectors.

We’ll highlight more things we like about the overall package structure, and then dig into how exactly Diamond makes it possible for the application to import and use externally defined collectors.

Separate different functionality into namespaces (they are one honking great idea)

The diagram in Figure 5-2 shows the server module

interacting with three other modules in the project: diamond.handler,

diamond.collector, and diamond.utils.

The utils subpackage could realistically have contained all of its

classes and functions in a single, large util.py module, but there

was an opportunity to use namespaces to separate code into related

groups, and the development team took it. Honking great!

All of the implementations of Handlers are contained in diamond/handler (which makes sense), but the structure for the Collectors is different.

There’s not a directory, only a module diamond/collector.py

that defines the Collector and ProcessCollector base classes.

All implementations of the Collectors are defined instead in

Diamond/src/collectors/ and would be installed in the

virtual environment under venv/share/diamond/collectors

when installing from PyPI (as recommended) rather than from GitHub (like we

did to read it).

This helps the user to create new implementations of Collectors: placing all of the collectors in the same location makes it

easier for the application to find them and easier for library users to

follow their example.

Finally, each Collector implementation in Diamond/src/collectors is in its own directory (rather than in a single file), which makes it possible to keep each Collector implementation’s tests separate. Also honking great.

User-extensible custom classes (complex is better than complicated)

It’s easy to add new Collector implementations: just subclass the

diamond.collector.Collector abstract base class,6

implement a Collector.collect() method,

and place the implementation in its own directory in venv/src/collectors/.

Underneath, the implementation is complex, but the user doesn’t see it. This section shows both the simple user-facing part of Diamond’s Collector API and the complex code that makes this user interface possible.

Complex versus complicated

We can boil down the user experience of working with complex code to be something like experiencing a Swiss watch—it just works, but inside there are a ton of precisely made little pieces, all interfacing with remarkable precision, in order to create the effortless user experience. Using complicated code, on the other hand, is like piloting an airplane—you really have to know what you’re doing to not crash and burn.7 We don’t want to live in a world without airplanes, but we do want our watches to work without us having to be rocket scientists. Wherever it’s possible, less complicated user interfaces are a good thing.

The simple user interface

To create a custom data collector, the user must subclass the abstract class,

Collector, and then provide, via the configuration file, the path to that new collector.

Here is an example of a new Collector definition from Diamond/src/collectors/cpu/cpu.py.

When Python searches for the collect() method, it will

look in the CPUCollector for a definition first, and then

if it doesn’t find the definition, it will use

diamond.collector.Collector.collect(), which raises

the NotImplementedError.

Minimal collector code would look like this:

# coding=utf-8importdiamond.collectorimportpsutilclassCPUCollector(diamond.collector.Collector):defcollect(self):# In Collector, this just contains raise(NotImplementedError)metric_name="cpu.percent"metric_value=psutil.cpu_percent()self.publish(metric_name,metric_value)

The default place to store the collector definitions is in the directory

venv/share/diamond/collectors/; but you can store it wherever you

define in the collectors_path value in the configuration file.

The class name, CPUCollector, is already listed in the example

configuration file.

Except for adding a hostname or a hostname_method specification either in the overall

defaults (under the text in the configuration file) or in the

individual collector’s overrides, as shown in the

following example, there need not be any other changes (the documentation lists all of the optional

collector settings):

[[CPUCollector]]enabled=Truehostname_method=smart

The more complex internal code

Behind the scenes, the Server will call utils.load_collectors() using

the path specified in collectors_path. Here is most of that function,

truncated for brevity:

defload_collectors(paths=None,filter=None):"""Scan for collectors to load from path"""# Initialize return valuecollectors={}log=logging.getLogger('diamond')ifpathsisNone:returnifisinstance(paths,basestring):paths=paths.split(',')paths=map(str.strip,paths)load_include_path(paths)forpathinpaths:##~~ Skip lines that confirm 'path' exists.forfinos.listdir(path):# Are we a directory? If so, process down the treefpath=os.path.join(path,f)ifos.path.isdir(fpath):subcollectors=load_collectors([fpath])forkeyinsubcollectors:collectors[key]=subcollectors[key]# Ignore anything that isn't a .py fileelif(os.path.isfile(fpath)##~~ ... Skip tests confirming fpath is a Python module ...):##~~ ... Skip the part that ignores filtered paths ...modname=f[:-3]try:# Import the modulemod=__import__(modname,globals(),locals(),['*'])except(KeyboardInterrupt,SystemExit),err:##~~ ... Log the exception and quit ...except:##~~ ... Log the exception and continue ...# Find all classes defined in the moduleforattrnameindir(mod):attr=getattr(mod,attrname)# Only attempt to load classes that are subclasses# of Collectors but are not the base Collector classif(inspect.isclass(attr)andissubclass(attr,Collector)andattr!=Collector):ifattrname.startswith('parent_'):continue# Get class namefqcn='.'.join([modname,attrname])try:# Load Collector classcls=load_dynamic_class(fqcn,Collector)# Add Collector classcollectors[cls.__name__]=clsexceptException:##~~ log the exception and continue ...# Return Collector classesreturncollectors

Break up the string (first function call); otherwise, the paths are lists of string paths to where the user-defined custom

Collectorsubclasses are defined.

This recursively descends the paths given, inserting every directory into

sys.pathso that later the Collectors can be imported.

Here’s the recursion—

load_collectors()is calling itself.8

After loading the subdirectories’ collectors, update the original dictionary of custom collectors with the new ones from those subdirectories.

Since the introduction of Python 3.1, the

importlibmodule in Python’s standard library provides a preferred way to do this (via the moduleimportlib.import_module; parts ofimportlib.import_modulehave also been backported to Python 2.7). This demonstrates how to programmatically import a module given the string module name.

Here’s how to programmatically access attributes in a module given just the string attribute name.

Actually,

load_dynamic_classmay not be necessary here. It re-imports the module, checks that the named class is actually a class, checks that it’s actually a Collector, and if so returns the newly loaded class. Redundancies sometimes occur in open source code written by large groups.

Here’s how they get the class name to use later when applying the configuration file options given only the string class name.

Style Examples from Diamond

There’s a great example use of a closure in Diamond that demonstrates what was said in “Late binding closures” about this behavior often being desirable.

Example use of a closure (when the gotcha isn’t a gotcha)

A closure is a function that makes use of variables available

in the local scope that would otherwise not be available when the function is called.

They can be difficult to implement and understand in other languages,

but are not hard to implement in Python, because Python treats functions just

like any other object.9

For example, functions can be passed around as arguments, or returned from other

functions.

Here’s an example excerpt from the diamond executable

that shows how to implement a closure in Python:

##~~ ... Skip the import statements ...defmain():try:##~~ ... Skip code that creates the command-line parser ...# Parse command-line Args(options,args)=parser.parse_args()##~~ ... Skip code that parses the configuration file ...##~~ ... Skip code that sets up the logger ...# Pass the exit upstream rather then handle it as an general exceptionexceptSystemExit,e:raiseSystemExit##~~ ... Skip code that handles other exceptions related to setup ...try:# PID MANAGEMENTifnotoptions.skip_pidfile:# Initialize PID fileifnotoptions.pidfile:options.pidfile=str(config['server']['pid_file'])##~~ ... Skip code to open and read the PID file if it exists, ...##~~ ... and then delete the file if there is no such PID ...##~~ ... or exits if there is already a running process. ...##~~ ... Skip the code that sets the group and user ID ...##~~ ... and the code that changes the PID file permissions. ...##~~ ... Skip the code that checks whether to run as a daemon, ...##~~ ... and if so detaches the process. ...# PID MANAGEMENTifnotoptions.skip_pidfile:# Finish initializing PID fileifnotoptions.foregroundandnotoptions.collector:# Write PID filepid=str(os.getpid())try:pf=file(options.pidfile,'w+')exceptIOError,e:log.error("Failed to write child PID file:%s"%(e))sys.exit(1)pf.write("%s\n"%pid)pf.close()# Loglog.debug("Wrote child PID file:%s"%(options.pidfile))# Initialize serverserver=Server(configfile=options.configfile)defsigint_handler(signum,frame):log.info("Signal Received:%d"%(signum))# Delete PID fileifnotoptions.skip_pidfileandos.path.exists(options.pidfile):os.remove(options.pidfile)# Loglog.debug("Removed PID file:%s"%(options.pidfile))sys.exit(0)# Set the signal handlerssignal.signal(signal.SIGINT,sigint_handler)signal.signal(signal.SIGTERM,sigint_handler)server.run()# Pass the exit upstream rather then handle it as a general exceptionexceptSystemExit,e:raiseSystemExit##~~ ... Skip code that handles any other exceptions ...##~~ ... and all of the rest of the script.

When we skip code, the missing parts will be summarized by a comment preceded by two tildes (

##~~ like this).

The reason for the PID10 file is to make sure the daemon is unique (i.e., not accidentally started twice), to communicate the associated process ID quickly to other scripts, and to make it evident that an abnormal termination has occurred (because in this script, the PID file is deleted upon normal termination).

All of this code is just to provide context leading up to the closure. At this point, either the process is running as a daemon (and now has a different process ID than before) or it will skip this part because it’s already written its correct PID to the PID file.

This (

sigint_handler()) is the closure. It is defined inside ofmain(), rather than at the top level, outside of any functions, because it needs to know whether to look for a PID file, and if so where to look.

It gets this information from the command-line options, which it can’t obtain until after the call to

main(). That means all of the options related to the PID file are local variables inmain’s namespace.

The closure (the function

sigint_handler()) is sent to the signal handler and will be used to handleSIGINTandSIGTERM.

Tablib

Tablib is a Python library that converts between

different data formats, storing data in a Dataset object, or

multiple Datasets in a Databook.

Datasets stored in the JSON, YAML, DBF, and CSV file formats

can be imported, and datasets can be exported to XLSX, XLS,

ODS, JSON, YAML, DBF, CSV, TSV, and HTML.

Tablib was first released by Kenneth Reitz in 2010.

It has the intuitive API design typical of Reitz’s projects.

Reading a Small Library

Tablib is a library, not an application, so there isn’t a single obvious entry point like there is with HowDoI and Diamond.

Get Tablib from GitHub:

$git clone https://github.com/kennethreitz/tablib.git$virtualenv -p python3 venv$sourcevenv/bin/activate(venv)$cdtablib(venv)$pip install --editable .(venv)$python test_tablib.py# Run the unit tests.

Read Tablib’s documentation

Tablib’s documentation starts

off immediately with a use case, and then goes into describing

its capabilities in more detail: it provides a Dataset object

that has rows, headers, and columns. You can do I/O from various

formats to the Dataset object. And the advanced usage section says

you can add tags to rows, and create derived columns that are

functions of other columns.

Use Tablib

Tablib is a library, not an executable like HowDoI or Diamond,

so you can open a Python interactive session and have the expectation that you can use use the help() function to explore the API. Here’s

our example of the tablib.Dataset class, the different data

formats, and how I/O works:

>>>importtablib>>>data=tablib.Dataset()>>>names=('Black Knight','Killer Rabbit')>>>>>>fornameinnames:...fname,lname=name.split()...data.append((fname,lname))...>>>data.dict[['Black','Knight'],['Killer','Rabbit']]>>>>>>(data.csv)Black,KnightKiller,Rabbit>>>data.headers=('First name','Last name')>>>(data.yaml)-{Firstname:Black,Lastname:Knight}-{Firstname:Killer,Lastname:Rabbit}>>>withopen('tmp.csv','w')asoutfile:...outfile.write(data.csv)...64>>>newdata=tablib.Dataset()>>>newdata.csv=open('tmp.csv').read()>>>(newdata.yaml)-{Firstname:Black,Lastname:Knight}-{Firstname:Killer,Lastname:Rabbit}

Read Tablib’s code

The file structure under tablib/ looks like this:

tablib|--- __init__.py|--- compat.py|--- core.py|--- formats/|--- packages/

The two directories, tablib/formats/ and tablib/packages/, will be discussed in a few sections.

Python supports module-level docstrings as well as the docstrings we’ve already

described—a string literal that is the first statement in a function, class, or

class method. Stack Overflow has good advice on how to

document a module.

For us, this means another way to explore source code is by typing head *.py in

a terminal shell while in the directory at the top level of the package—to

show all of the module docstrings at once. Here’s what we get:

(venv)$cdtablib(venv)$head*.py==>__init__.py<==""" Tablib. """fromtablib.coreimport(Databook,Dataset,detect,import_set,import_book,InvalidDatasetType,InvalidDimensions,UnsupportedFormat,__version__)==>compat.py<==# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-""" tablib.compat ~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Tablib compatiblity module. """==>core.py<==# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-""" tablib.core ~~~~~~~~~~~ This module implements the central Tablib objects. :copyright: (c) 2014 by Kenneth Reitz. :license: MIT, see LICENSE for more details. """

We learn that:

The top-level API (the contents of __init__.py are accessible from

tablibafter animport tablibstatement) has just nine entry points: theDatabookandDatasetclasses are mentioned in the documentation,detectcould be for identifying formatting,import_setandimport_bookmust import data, and the last three classes—InvalidDatasetType,InvalidDimensions, andUnsupportedFormat—look like exceptions. (When code follows PEP 8, we can tell which objects are custom classes from their capitalization.)

tablib/compat.py is a compatibility module. A quick look inside will show that it handles Python 2/Python 3 compatibility issues in a similar way to HowDoI, by resolving different locations and names to the same symbol for use in tablib/core.py.

tablib/core.py, like it says, implements the central Tablib objects like

DatasetandDatabook.

Structure Examples from Tablib

The primary thing we want to highlight form Tablib is the absence of

the use of classes in the modules in tablib/formats/—it’s a perfect

example of the statement we made earlier about not overusing classes.

Next, we show excerpts of how Tablib uses the decorator syntax and the

property class to

create derived attributes like the dataset’s height and width,

and how it dynamically registers file formats to avoid duplicating

what would be boilerplate code for each of the different format types (CSV, YAML, etc.).

The last two subsections are a little obscure—we look at how

Tablib vendorizes dependencies, and then discuss the __slots__ property

of new class objects. You can skip these sections and still lead a happy,

Pythonic life.

No needless object-oriented code in formats (use namespaces for grouping functions)

The formats directory contains all of the defined file formats for I/O. The module names,

_csv.py, _tsv.py, _json.py,

_yaml.py, _xls.py,

_xlsx.py, _ods.py, and _xls.py are prefixed with an underscore—this indicates to the library user that they are not intended for direct use.

We can change directories into formats, and search for

classes and functions. Using

grep ^class formats/*.py reveals there are no class definitions, and using

grep ^def formats/*.py shows that each module contains some or all

of the following functions:

-

detect(stream)infers the file format based on the stream content. -

dset_sheet(dataset, ws)formats the Excel spreadsheet cells. -

export_set(dataset)exports the Dataset to the given format, returning a formatted string with the new format. (Or, for Excel, returning abytesobject—or a binary-formatted string in Python 2.) -

import_set(dset, in_stream, headers=True)replaces the contents of the dataset with the contents of the input stream. -

export_book(databook)exports the Datasheets in the Databook to the given format, returning a string orbytesobject. -

import_book(dbook, in_stream, headers=True)replaces the contents of the databook with the contents of the input stream.

This is an example of using modules as namespaces

(after all, they are one honking great idea) to separate functions,

rather than using unnecessary classes.

We know each function’s purpose from its name: for example,

formats._csv.import_set(), formats._tsv.import_set(), and formats._json.import_set()

import datasets from CSV, TSV, and JSON-formatted files, respectively.

The other functions do data exporting and file format detection, when possible,

for each of Tablib’s available formats.

Descriptors and the property decorator (engineer immutability when the API would benefit)

Tablib is our first library that uses Python’s decorator syntax,

described in “Decorators”.

The syntax uses the @ symbol in front of a function name,

placed directly above another function. It modifies (or “decorates”) the

function directly below. In the following excerpt, property changes the functions

Dataset.height and Dataset.width into descriptors—classes

with at least one of the __get__(), __set__(), or __delete__()

(“getter”, “setter”, or “delete”) methods defined.

For example, the attribute lookup Dataset.height will trigger the getter, setter, or delete

function depending on the context in which that attribute is used.

This behavior is only possible for new-style classes, discussed momentarily.

See this useful Python

tutorial on descriptors

for more information.

classDataset(object):## ... omit the rest of the class definition for clarity#@propertydefheight(self):"""The number of rows currently in the :class:`Dataset`. Cannot be directly modified."""returnlen(self._data)@propertydefwidth(self):"""The number of columns currently in the :class:`Dataset`. Cannot be directly modified. """try:returnlen(self._data[0])exceptIndexError:try:returnlen(self.headers)exceptTypeError:return0

This is how to use a decorator. In this case,

propertymodifiesDataset.heightto behave as a property rather than as a bound method. It can only operate on class methods.

When

propertyis applied as a decorator, theheightattribute will return the height of theDatasetbut it is not possible to assign a height to theDatasetby invokingDataset.height.

Here is what the height and width attributes look

like when used:

>>>importtablib>>>data=tablib.Dataset()>>>data.header=("amount","ingredient")>>>data.append(("2 cubes","Arcturan Mega-gin"))>>>data.width2>>>data.height1>>>>>>data.height=3Traceback(mostrecentcalllast):File"<stdin>",line1,in<module>AttributeError:can't set attribute

So, data.height can be accessed like an attribute,

but it’s not settable—it’s calculated from the

data and so is always current.

This is ergonomic API design:

data.height is easier to type than data.get_height();

it’s clear what the meaning of data.height is;

and because it is calculated from the data

(and the property is not settable—only the “getter” function is defined),

there isn’t a danger that it will be out of

sync from the correct number.

The property decorator can only be applied

to attributes of classes, and only to classes that derive from the

base object object (e.g., class MyClass(object) not class MyClass()—inheritance from object is always the case in Python 3).

This same tool is used to create Tablib’s data import and

export API in the various formats:

Tablib does not store the string value for each of

the CSV, JSON, and YAML outputs.

Rather, the Dataset attributes csv, json, and yaml are properties,

like Dataset.height and Dataset.width in the preceding example—they call a function that generates the result from the

stored data or parses the input format and then replaces the

core data. But there’s only one dataset.

When data.csv is on the left of an equals sign, the property’s

“setter” function is called, to parse the dataset from the CSV format.

And when data.yaml is on the right of an equals sign, or alone,

the “getter” is called, to create a string with the given format

from the internal dataset. Here is an example:

>>>importtablib>>>data=tablib.Dataset()>>>>>>data.csv="\n".join((..."amount,ingredient",..."1 bottle,Ol'Janx Spirit",..."1 measure,Santraginus V seawater",..."2 cubes,Arcturan Mega-gin",..."4 litres,Fallian marsh gas",..."1 measure,Qalactin Hypermint extract",..."1 tooth,Algolian Suntiger",..."a sprinkle,Zamphuor",..."1 whole,olive"))>>>>>>data[2:4][('2 cubes','Arcturan Mega-gin'),('4 litres','Fallian marsh gas')]>>>>>>(data.yaml)-{amount:1bottle,ingredient:OlJanxSpirit}-{amount:1measure,ingredient:SantraginusVseawater}-{amount:2cubes,ingredient:ArcturanMega-gin}-{amount:4litres,ingredient:Fallianmarshgas}-{amount:1measure,ingredient:QalactinHypermintextract}-{amount:1tooth,ingredient:AlgolianSuntiger}-{amount:asprinkle,ingredient:Zamphuor}-{amount:1whole,ingredient:olive}

data.csvon the lefthand side of the equals sign (assignment operator) invokesformats.csv.import_set(), withdataas the first argument, and the string of Gargle Blaster ingredients as its second argument.

data.yamlalone invokesformats.yaml.export_set(), withdataas its argument, outputting the formatted YAML string for theprint()function.

The “getter”, “setter”, and also a “deleter” function can be bound to

a single attribute using property. Its

signature is property(fget=None, fset=None, fdel=None, doc=None),

in which fget identifies the “getter” function (formats.csv.import_set()),

fset identifies the “setter” function (formats.csv.export_set()),

and fdel identifies the “deleter” function, which is left as None.

We will see the code where the formatting properties are set, programmatically,

next.

Programmatically registered file formats (don’t repeat yourself)

Tablib places all of the file formatting routines in the

formats subpackage. This structure choice makes

the main core.py module cleaner and the entire

package modular; it’s easy to add new file formats.

Although it would have been possible to paste chunks of

nearly identical code and import each file format’s import and

export behaviors separately,

all of the formats are programmatically loaded into the Dataset

class to properties named after each format.

We’re printing the entire contents of formats/__init__.py in the following code example

because it’s not too large a file, and we want to show where

formats.available is defined:

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-""" Tablib - formats """from.import_csvascsvfrom.import_jsonasjsonfrom.import_xlsasxlsfrom.import_yamlasyamlfrom.import_tsvastsvfrom.import_htmlashtmlfrom.import_xlsxasxlsxfrom.import_odsasodsavailable=(json,xls,yaml,csv,tsv,html,xlsx,ods)

This line explicitly tells the Python interpreter that the file encoding is UTF-8.11

Here’s the definition of

formats.available, right in formats/__init__.py. It’s also available viadir(tablib.formats), but this explicit list is easier to understand.

In core.py, rather than about 20 (ugly, hard to maintain) repeated

function definitions for each format option, the code imports each format

programmatically by calling self._register_formats()

at the end of the Dataset’s __init__() method.

We’ve excerpted just Dataset._register_formats() here:

classDataset(object):## ... skip documentation and some definitions ...#@classmethoddef_register_formats(cls):"""Adds format properties."""forfmtinformats.available:try:try:setattr(cls,fmt.title,property(fmt.export_set,fmt.import_set))exceptAttributeError:setattr(cls,fmt.title,property(fmt.export_set))exceptAttributeError:pass## ... skip more definitions ...#@propertydeftsv():"""A TSV representation of the :class:`Dataset` object. The top row will contain headers, if they have been set. Otherwise, the top row will contain the first row of the dataset. A dataset object can also be imported by setting the :class:`Dataset.tsv` attribute. :: data = tablib.Dataset() data.tsv = 'age\tfirst_name\tlast_name\n90\tJohn\tAdams'Import assumes (for now) that headers exist. """pass

The

@classmethodsymbol is a decorator, described more extensively in “Decorators”, that modifies the method_register_formats()so that it passes the object’s class (Dataset) rather than the object instance (self) as its first argument.

The

formats.availableis defined in formats/__init__.py and contains all of the available formatting options.

In this line,

setattrassigns a value to the attribute namedfmt.title(i.e.,Dataset.csvorDataset.xls). The value it assigns is a special one;property(fmt.export_set, fmt.import_set)turnsDataset.csvinto a property.

There will be an

AttributeErroriffmt.import_setis not defined.

If there is no import function, try to assign just the export behavior.

If there is neither an export nor an import function to assign, just don’t assign anything.

Each of the file formats is defined as a property here, with a descriptive docstring. The docstring will be retained when

property()is called at tag or

or

to assign the extra behaviors.

to assign the extra behaviors.

The

\tand\nare string escape sequences that represent the Tab character and a newline, respectively. They’re all listed in Python’s string literals documentation.

Vendorized dependencies in packages (an example of how to vendorize)

Tablib’s dependencies are currently vendorized (meaning they are shipped bundled with the code—in this case, in the directory packages) but may be moved to a plug-in system in the future. The packages directory contains third-party packages included inside Tablib to ensure compatibility, rather than the other option, which is to specify versions in the setup.py file that will be downloaded and installed when Tablib is installed. This technique is discussed in “Vendorizing Dependencies”; the choice for Tablib was made both to reduce the number of dependencies the user would have to download, and because sometimes there are different packages for Python 2 and Python 3, which are both included. (The appropriate one is imported, and their functions set to a common name, in tablib/compat.py). That way, Tablib can have one single code base instead of two—one for each version of Python. Because each of these dependencies has its own license, a NOTICE document was added to the top level of the project directory that lists each dependency’s license.

Saving memory with __slots__ (optimize judiciously)

Python prefers readability over speed. Its entire design, its Zen aphorisms, and its early influence from educational languages like ABC are all about placing user-friendliness above performance (although we’ll talk about more optimization options in “Speed”).

The use of __slots__ in tablib is a case where optimization matters.

This is a slightly obscure reference, and it’s only available for new-style classes

(described in a few pages), but we want to show that it’s possible

to optimize Python when necessary.

This optimization is only useful when you have tons of very small objects

by reducing the footprint of each class instance by the size of one dictionary

(large objects would make this small savings irrelevant,

and fewer objects make the savings not worth it). Here is an excerpt from the

__slots__ documentation:

By default, instances of classes have a dictionary for attribute storage. This wastes space for objects having very few instance variables. The space consumption can become acute when creating large numbers of instances.

The default can be overridden by defining

__slots__in a class definition. The__slots__declaration takes a sequence of instance variables and reserves just enough space in each instance to hold a value for each variable. Space is saved because__dict__is not created for each instance.

Normally, this isn’t something to care about—notice that

__slots__ doesn’t appear in the Dataset or Databook classes,

just the Row class—but because there can be

thousands of rows of data, __slots__ is a good idea.

The Row class is not exposed in tablib/__init__.py because

it is a helper class to Dataset, instantiated once for every row.

This is how its definition looks in the beginning part of the

definition of the Row class:

classRow(object):"""Internal Row object. Mainly used for filtering."""__slots__=['_row','tags']def__init__(self,row=list(),tags=list()):self._row=list(row)self.tags=list(tags)## ... etc. ...#

The problem now is that there is no longer a __dict__ attribute in the

Row instances, but the pickle.dump() function (used for object serialization)

by default uses __dict__ to serialize the object

unless the method __getstate__() is defined.

Likewise, during unpickling (the process that reads the serialized

bytes and reconstructs the object in memory),

if __setstate__() is not defined, pickle.load() will load to the

object’s __dict__ attribute.

Here is how to get around that:

classRow(object):## ... skip the other definitions ...#def__getstate__(self):slots=dict()forslotinself.__slots__:attribute=getattr(self,slot)slots[slot]=attributereturnslotsdef__setstate__(self,state):for(k,v)inlist(state.items()):setattr(self,k,v)

For more information about __getstate__() and __setstate__() and pickling,

see the

__getstate__ documentation.

Style Examples from Tablib

We have one single style example from Tablib—operator overloading—which gets into the details of Python’s data model. Customizing the behavior of your classes makes it easier for those who use your API to write beautiful code.

Operator overloading (beautiful is better than ugly)

This code section uses Python’s operator overloading to enable

operations on either the Dataset’s rows or columns.

The following first sample code shows interactive use of the bracket operator ([ ])

for both numerical indices and column names,

and the second one shows the code that uses this behavior:

>>>data[-1]('1 whole','olive')>>>>>>data[-1]=['2 whole','olives']>>>>>>data[-1]('2 whole','olives')>>>>>>deldata[2:7]>>>>>>(data.csv)amount,ingredient1bottle,Ol'Janx Spirit1measure,SantraginusVseawater2whole,olives>>>data['ingredient']["Ol'Janx Spirit",'Santraginus V seawater','olives']

When using numbers, accessing data via the bracket operator

([])gives the row at the specified location.

This is assignment using the bracket operator …

… it becomes 2 olives instead of the original one.

This is deletion using a slice—

2:7denotes all of the numbers2,3,4,5,6but not7.

See how the recipe afterward is much smaller.

It is also possible to access columns by name.

The part of the Dataset code that defines the behavior of the bracket

operator shows how to handle access both by column name and by row number:

classDataset(object):## ... skip the rest of the definitions for brevity ...#def__getitem__(self,key):ifisinstance(key,str)orisinstance(key,unicode):ifkeyinself.headers:pos=self.headers.index(key)# get 'key' index from each datareturn[row[pos]forrowinself._data]else:raiseKeyErrorelse:_results=self._data[key]ifisinstance(_results,Row):return_results.tupleelse:return[result.tupleforresultin_results]def__setitem__(self,key,value):self._validate(value)self._data[key]=Row(value)def__delitem__(self,key):ifisinstance(key,str)orisinstance(key,unicode):ifkeyinself.headers:pos=self.headers.index(key)delself.headers[pos]forrowinself._data:delrow[pos]else:raiseKeyErrorelse:delself._data[key]

First, check whether we are seeking a column (

Trueifkeyis a string) or a row (Trueif thekeyis an integer or slice).

Here the code checks for the key to be in

self.headers, and then…

…explicitly raises a

KeyErrorso that access by column name behaves as one would expect a dictionary to. The wholeif/elsepair is not necessary for the operation of the function—if it were omitted, aValueErrorwould still be raised byself.headers.index(key)ifkeywere not inself.headers. The only purpose for this check is to provide a more informative error for the library user.

This is how the code determines whether

keywas a number or a slice (like2:7). If a slice, the_resultswould be a list, not aRow.

Here is where the slice is processed. Because the rows are returned as tuples, the values are an immutable copy of the acual data, and the dataset’s values (actually stored as lists) won’t accidentally be corrupted by an assignment.

The

__setitem__()method can change a single row but not a column. This is intentional; there is no way provided to change the content of an entire column; and for data integrity, this is probably not a bad choice. The user can always transform the column and insert it at any position using one of the methodsinsert_col(),lpush_col(), orrpush_col().

The

__delitem__()method can either delete a column or a row, using the same logic as__getitem__().

For more information about additional operator overloading and other special methods, see the Python documentation on Special method names.

Requests

On Valentine’s day in 2011, Kenneth Reitz released a love letter to the Python community: the Requests library. Its enthusiastic adoption emphatically makes the case for intuitive API design (meaning the API is so straightforward you almost don’t need documentation).

Reading a Larger Library

Requests is a larger library than Tablib, with many more modules, but we’ll still approach reading it the same way—by looking at the documentation and following the API through the code.

Get Requests from GitHub:

$git clone https://github.com/kennethreitz/requests.git$virtualenv -p python3 venv$sourcevenv/bin/activate(venv)$cdrequests(venv)$pip install --editable .(venv)$pip install -r requirements.txt# Required for unit tests(venv)$py.test tests# Run the unit tests.

Some tests may fail—for example, if your service provider intercepts

404 errors to give some advertising page, you won’t get the ConnectionError.

Read Requests’s documentation

Requests is a bigger package, so first just scan the section

titles from the

Requests documentation.

Requests extends urrlib and httplib from Python’s standard library

to provide methods that perform HTTP requests. The library includes

support for international

domains and URLs, automatic decompression, automatic content decoding,

browser style SSL verification, HTTP(S) proxy support, and

other features, which are all defined by

the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) standards for HTTP

in their requests for comment (RFCs) 7230 through 7235.12

Requests strives to cover all of the IETF’s HTTP specifications, using only a handful of functions, a bunch of keyword arguments, and a few featureful classes.

Use Requests

Like with Tablib, there is enough information in the docstrings to use Requests without actually reading the online documentation. Here’s a brief interaction:

>>>importrequests>>>help(requests)# Shows a usage statement and says to see `requests.api`>>>help(requests.api)# Shows a detailed API description>>>>>>result=requests.get('https://pypi.python.org/pypi/requests/json')>>>result.status_code200>>>result.okTrue>>>result.text[:42]'{\n"info": {\n"maintainer": null'>>>>>>result.json().keys()dict_keys(['info','releases','urls'])>>>>>>result.json()['info']['summary']'Python HTTP for Humans.'

Read Requests’s code

Here are the contents of the Requests package:

$ls__init__.pycacert.pemexceptions.pysessions.pyadapters.pycerts.pyhooks.pystatus_codes.pyapi.pycompat.pymodels.pystructures.pyauth.pycookies.pypackages/utils.py

cacert.pem is a default certificate bundle to use when checking SSL certificates.

Requests has a flat structure, except for a packages directory that vendorizes (contains the external libraries)

chardetandurllib3. These dependencies are imported asrequests.packages.chardetandrequests.packages.urllib3, so programmers can still accesschardetandurllib3from the standard library.

We can mostly figure out what’s happening thanks to well-chosen

module names, but if we want a little more imformation, we can again peek at the

module docstrings by typing head *.py

in the top-level directory. The following lists displays these module

docstrings, slightly truncated. (It doesn’t show compat.py. We can tell from its name,

especially because it’s named the same as in Reitz’s Tablib library,

that it takes care of Python 2 to Python 3 compatibility.)

- api.py

-

Implements the Requests API

- hooks.py

-

Provides the capabilities for the Requests hooks system

- models.py

-

Contains the primary objects that power Requests

- sessions.py

-

Provides a Session object to manage and persist settings across requests (cookies, auth, proxies)

- auth.py

-

Contains the authentication handlers for Requests

- status_codes.py

-

A lookup table mapping status titles to status codes

- cookies.py

-

Compatibility code to be able to use

cookielib.CookieJarwith requests - adapters.py

-

Contains the transport adapters Requests uses to define and maintain connections

- exceptions.py

-

All of Requests’ exceptions

- structures.py

-

Data structures that power Requests

- certs.py

-

Returns the preferred default CA certificate bundle listing trusted SSL certificates

- utils.py

-

Provides utility functions that are used within Requests that are also useful for external consumption

Insights from reading all of the headers:

-

There is a hook system (hooks.py), implying the user can modify how Requests works. We won’t discuss it in depth because it will take us too far off topic.

-

The main module is models.py, as it contains “the primary objects that power Requests.”

-

The reason

sessions.Sessionexists is to persist cookies across multiple requests (that might occur during authentication, for example). -

The actual HTTP connection is made by objects from adapters.py.

-

The rest is kind of obvious: auth.py is for authentication, status_codes.py has the status codes, cookies.py is for adding and removing cookies, exceptions.py is for exceptions, structures.py contains data structures (e.g., a case-insensitive dictionary), and utils.py contains utility functions.

The idea to put communication separately in adapters.py is innovative

(at least to this writer).

It means models.Request, models.PreparedRequest, and models.Response

don’t actually do anything—they just store data, possibly

manipulating it a bit for presentation, pickling, or encoding purposes.

Actions are handled by separate classes that exist specifically to perform an action,

like authentication or communication.

Every class does just one thing, and each module

contains classes that do similar things—a Pythonic approach most of us already adhere to with our function definitions.

Structure Examples from Requests

Everyone loves the Requests API—it is easy to remember and helps

its users to write simple, beautiful code.

This section first discusses the design preference for more comprehensible

error messages and an easy-to-memorize API that we think went into

creation of the requests.api module, and then explores the differences

between the requests.Request and urllib.request.Request object,

offering an opinion on why requests.Request exists.

Top-level API (preferably only one obvious way to do it)

The functions defined in api.py (except request()) are named after HTTP

request methods.13

Each request method is the same except for its method name and the choice of

exposed keyword parameters, so we’re truncating this exerpt from requests/api.py

after the get() function:

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-""" requests.api ~~~~~~~~~~~~ This module implements the Requests API. :copyright: (c) 2012 by Kenneth Reitz. :license: Apache2, see LICENSE for more details. """from.importsessionsdefrequest(method,url,**kwargs):"""Constructs and sends a :class:`Request <Request>`. :param method: method for the new :class:`Request` object. :param url: URL for the new :class:`Request` object. :param params: (optional) Dictionary or bytes to be sent in the query string for the :class:`Request`. ... skip the documentation for the remaining keyword arguments ...:return: :class:`Response <Response>` object :rtype: requests.Response Usage:: >>> import requests >>> req = requests.request('GET', 'http://httpbin.org/get') <Response [200]> """# By using the 'with' statement, we are sure the session is closed, thus we# avoid leaving sockets open which can trigger a ResourceWarning in some# cases, and look like a memory leak in others.withsessions.Session()assession:returnsession.request(method=method,url=url,**kwargs)defget(url,params=None,**kwargs):"""Sends a GET request. :param url: URL for the new :class:`Request` object. :param params: (optional) Dictionary or bytes to be sent in the query string for the :class:`Request`. :param \*\*kwargs: Optional arguments that ``request`` takes. :return: :class:`Response <Response>` object :rtype: requests.Response """kwargs.setdefault('allow_redirects',True)returnrequest('get',url,params=params,**kwargs)

The

request()function contains a**kwargsin its signature. This means extraneous keyword arguments will not cause an exception, and it hides options from the user.

The documentation omitted here for brevity describes every keyword argument that has an associated action. If you use

**kwargsin your function signature, this is the only way the user can tell what the contents of**kwargsshould be, short of looking at the code themselves.

The

withstatement is how Python supports a runtime context. It can be used with any object that has an__enter__()and an__exit__()method defined.__enter()__will be called upon entering thewithstatement, and__exit__()will be called upon exit, regardless of whether that exit is normal or due to an exception.

The

get()function specifically pulls out theparams=Nonekeyword, applying a default value ofNone. Theparamskeyword argument relevant forgetbecause it’s for terms to be used in an HTTP query string. Exposing selected keyword arguments gives flexibility to the advanced user (via the remaining**kwargs) while making usage obvious for the 99% of people who don’t need advanced options.

The default for the

request()function is to not allow redirects, so this step sets it toTrueunless the user set it already.

The

get()function then simply callsrequest()with its first parameter set to"get". Makinggeta function has two advantages over just using a string argument likerequest("get", ...). First, it becomes obvious, even without documentation, which HTTP methods are available with this API. Second, if the user makes a typographical error in the method name, aNameErrorwill be raised earlier, and probably with a less confusing traceback, than would happen with error checking deeper in the code.

No new functionality is added in requests/api.py; it exists to present a simple API for the user. Plus, putting the string HTTP methods directly into the API as function names means any typographical error with the method name will be caught and identified early, for example:

>>>requests.foo('http://www.python.org')Traceback(mostrecentcalllast):File"<stdin>",line1,in<module>AttributeError:'module'objecthasnoattribute'foo'>>>>>>requests.request('foo','http://www.python.org')<Response[403]>

The Request and PreparedRequest objects (we’re all responsible users)

__init__.py exposes Request, PreparedRequest, and Response from

models.py as part of the main API.

Why does models.Request even exist?

There’s already a urllib.requests.Request in the standard library,

and in cookies.py there is specifically a MockRequest object that

wraps models.Request so that it works like urllib.requests.Request for

http.cookiejar.14

That means whatever methods are needed for the Request object to

interface with the cookies library are intentionally

excluded from requests.Request.

What is the point of all this extra work?

The extra methods in MockRequest (which exists to emulate urllib.request.Request

for the cookie library) are used by the cookie

library to manage cookies. Except for the get_type()

function (which usually returns “http” or “https” when using Requests)

and the unverifiable property (True for our case),

they’re all related to the URL or the request headers:

- Related to the header

add_unredirected_header()-

Add a new key, value pair to the header.

get_header()-

Get a specific name in the header dictionary.

get_new_headers()-

Get the dictionary containing new headers (added by

cookielib). has_header()-

Check whether a name exists in the header dictionary.

- Related to the URL

get_full_url()-

Does just what it says.

hostandorigin_req_host-

Properties that are set by calling the methods

get_host()andget_origin_req_host(), respectively. get_host()-

Extract the host from the URL (e.g., www.python.org from https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0008/).

get_origin_req_host()-

Call

get_host().15

They’re all access functions, except for MockRequest.add_unredirected_header().

The MockRequest docstring notes that “the original request object

is read-only.”

In requests.Request, data attributes are instead directly exposed.

This makes all of the accessor functions unnecessary: to

get or set the headers, access request-instance.headers.

It’s just a dictionary.

Likewise, the user can just get or change the string URL: request-instance.url.

The PreparedRequest object is initialized empty,

and is populated with a call to prepared-request-instance.prepare(),

filled with the relevant data (usually from the calling the Request object).

It’s at this point that things like correct capitalization and encoding are

applied. The object’s contents will, once prepared, be ready to send

to the server, but every attribute is still directly exposed.

Even PreparedRequest._cookies is exposed, although its

prepended underscore is a gentle reminder that the attribute

is not intended for use outside of the class,

without forbidding such access (we are all responsible users).

This choice exposes the objects to user modification,

but they are much more readable, and a little bit of extra

work inside of PreparedRequest corrects capitalization

issues and allows use of a dictionary in place of a CookieJar

(look for the if isinstance()/else statement):

## ... from models.py ...#classPreparedRequest():## ... skip everything else ...#defprepare_cookies(self,cookies):"""Prepares the given HTTP cookie data.This function eventually generates a ``Cookie`` header from thegiven cookies using cookielib. Due to cookielib's design, the headerwill not be regenerated if it already exists, meaning this functioncan only be called once for the life of the:class:`PreparedRequest <PreparedRequest>` object. Any subsequent callsto ``prepare_cookies`` will have no actual effect, unless the "Cookie"header is removed beforehand."""ifisinstance(cookies,cookielib.CookieJar):self._cookies=cookieselse:self._cookies=cookiejar_from_dict(cookies)cookie_header=get_cookie_header(self._cookies,self)ifcookie_headerisnotNone:self.headers['Cookie']=cookie_header

These things may not seem like a big deal, but it’s small choices like these that make an API intuitive to use.

Style Examples from Requests

The style examples from Requests are a good example use for sets

(which we think aren’t used often enough!) and a look at

the requests.status_codes module, which exists to make the style

of the rest of the code simpler by avoiding hardcoded HTTP status

codes everywhere else in the code.

Sets and set arithmetic (a nice, Pythonic idiom)

We haven’t yet shown an example use of Python sets in action. Python sets behave like sets in math—you can do subtraction, unions (the or operator), and intersections (the and operator):

>>>s1=set((7,6))>>>s2=set((8,7))>>>s1{6,7}>>>s2{8,7}>>>s1-s2# set subtraction{6}>>>s1|s2# set union{8,6,7}>>>s1&s2# set intersection{7}

Here’s one, down toward the end of this function from cookies.py

(with the label  ):

):

## ... from cookies.py ...#defcreate_cookie(name,value,**kwargs):"""Make a cookie from underspecified parameters. By default, the pair of `name` and `value` will be set for the domain '' and sent on every request (this is sometimes called a "supercookie"). """result=dict(version=0,name=name,value=value,port=None,domain='',path='/',secure=False,expires=None,discard=True,comment=None,comment_url=None,rest={'HttpOnly':None},rfc2109=False,)badargs=set(kwargs)-set(result)ifbadargs:err='create_cookie() got unexpected keyword arguments:%s'raiseTypeError(err%list(badargs))result.update(kwargs)result['port_specified']=bool(result['port'])result['domain_specified']=bool(result['domain'])result['domain_initial_dot']=result['domain'].startswith('.')result['path_specified']=bool(result['path'])returncookielib.Cookie(**result)

The

**kwargsspecification allows the user to provide any or none of the keyword options for a cookie.

Set arithmetic! Pythonic. Simple. And in the standard library. On a dictionary,

set()forms a set of the keys.

This is a great example of spliting a long line into two shorter lines that make much better sense. No harm done from the extra

errvariable.

The

result.update(kwargs)updates theresultdictionary with the key/value pairs in thekwargsdictionary, replacing existing pairs or creating ones that didn’t exist.

Here the call to

bool()coerces the value toTrueif the object is truthy (meaning it evaluates toTrue—in this case,bool(result['port'])evaluates toTrueif it’s notNoneand it’s not an empty container).

The signature to initialize

cookielib.Cookieis actually 18 positional arguments and one keyword argument (rfc2109defaults toFalse). It’s impossible for us average humans to memorize which position has which value, so here Requests takes advantage of being able to assign positional arguments by name as keyword arguments, sending the whole dictionary.

Status codes (readability counts)

The entire status_codes.py exists to create an object that can look up status codes by attribute. We’re showing the definition of the lookup dictionary in status_codes.py first, and then an excerpt of code that uses it from sessions.py: