Part III. Practices

Put simply, SREs run services—a set of related systems, operated for users, who may be internal or external—and are ultimately responsible for the health of these services. Successfully operating a service entails a wide range of activities: developing monitoring systems, planning capacity, responding to incidents, ensuring the root causes of outages are addressed, and so on. This section addresses the theory and practice of an SRE’s day-to-day activity: building and operating large distributed computing systems.

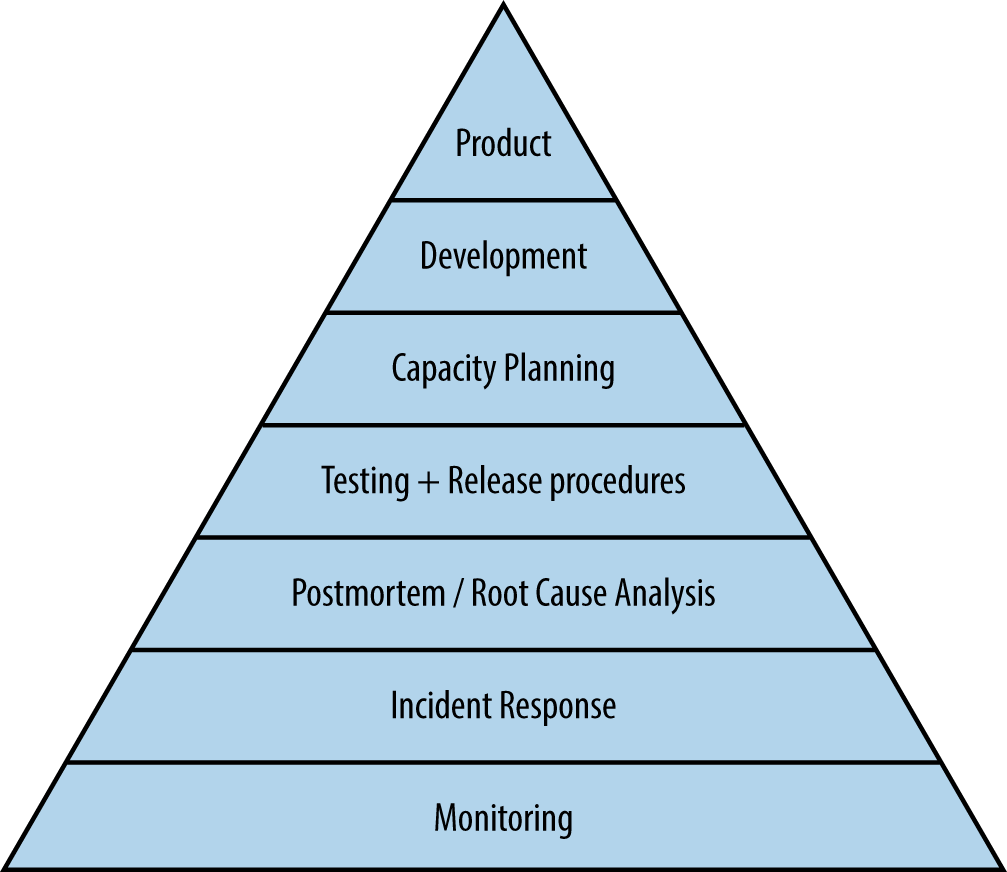

We can characterize the health of a service—in much the same way that Abraham Maslow categorized human needs [Mas43]—from the most basic requirements needed for a system to function as a service at all to the higher levels of function—permitting self-actualization and taking active control of the direction of the service rather than reactively fighting fires. This understanding is so fundamental to how we evaluate services at Google that it wasn’t explicitly developed until a number of Google SREs, including our former colleague Mikey Dickerson,1 temporarily joined the radically different culture of the United States government to help with the launch of healthcare.gov in late 2013 and early 2014: they needed a way to explain how to increase systems’ reliability.

We’ll use this hierarchy, illustrated in Figure III-1, to look at the elements that go into making a service reliable, from most basic to most advanced.

Figure III-1. Service Reliability Hierarchy

Monitoring

Without monitoring, you have no way to tell whether the service is even working; absent a thoughtfully designed monitoring infrastructure, you’re flying blind. Maybe everyone who tries to use the website gets an error, maybe not—but you want to be aware of problems before your users notice them. We discuss tools and philosophy in Chapter 10, Practical Alerting from Time-Series Data.

Incident Response

SREs don’t go on-call merely for the sake of it: rather, on-call support is a tool we use to achieve our larger mission and remain in touch with how distributed computing systems actually work (and fail!). If we could find a way to relieve ourselves of carrying a pager, we would. In Chapter 11, Being On-Call, we explain how we balance on-call duties with our other responsibilities.

Once you’re aware that there is a problem, how do you make it go away? That doesn’t necessarily mean fixing it once and for all—maybe you can stop the bleeding by reducing the system’s precision or turning off some features temporarily, allowing it to gracefully degrade, or maybe you can direct traffic to another instance of the service that’s working properly. The details of the solution you choose to implement are necessarily specific to your service and your organization. Responding effectively to incidents, however, is something applicable to all teams.

Figuring out what’s wrong is the first step; we offer a structured approach in Chapter 12, Effective Troubleshooting.

During an incident, it’s often tempting to give in to adrenalin and start responding ad hoc. We advise against this temptation in Chapter 13, Emergency Response, and counsel in Chapter 14, Managing Incidents, that managing incidents effectively should reduce their impact and limit outage-induced anxiety.

Postmortem and Root-Cause Analysis

We aim to be alerted on and manually solve only new and exciting problems presented by our service; it’s woefully boring to “fix” the same issue over and over. In fact, this mindset is one of the key differentiators between the SRE philosophy and some more traditional operations-focused environments. This theme is explored in two chapters.

Building a blameless postmortem culture is the first step in understanding what went wrong (and what went right!), as described in Chapter 15, Postmortem Culture: Learning from Failure.

Related to that discussion, in Chapter 16, Tracking Outages, we briefly describe an internal tool, the outage tracker, that allows SRE teams to keep track of recent production incidents, their causes, and actions taken in response to them.

Testing

Once we understand what tends to go wrong, our next step is attempting to prevent it, because an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Test suites offer some assurance that our software isn’t making certain classes of errors before it’s released to production; we talk about how best to use these in Chapter 17, Testing for Reliability.

Capacity Planning

In Chapter 18, Software Engineering in SRE, we offer a case study of software engineering in SRE with Auxon, a tool for automating capacity planning.

Naturally following capacity planning, load balancing ensures we’re properly using the capacity we’ve built. We discuss how requests to our services get sent to datacenters in Chapter 19, Load Balancing at the Frontend. Then we continue the discussion in Chapter 20, Load Balancing in the Datacenter and Chapter 21, Handling Overload, both of which are essential for ensuring service reliability.

Finally, in Chapter 22, Addressing Cascading Failures, we offer advice for addressing cascading failures, both in system design and should your service be caught in a cascading failure.

Development

One of the key aspects of Google’s approach to Site Reliability Engineering is that we do significant large-scale system design and software engineering work within the organization.

In Chapter 23, Managing Critical State: Distributed Consensus for Reliability, we explain distributed consensus, which (in the guise of Paxos) is at the core of many of Google’s distributed systems, including our globally distributed Cron system. In Chapter 24, Distributed Periodic Scheduling with Cron, we outline a system that scales to whole datacenters and beyond, which is no easy task.

Chapter 25, Data Processing Pipelines, discusses the various forms that data processing pipelines can take: from one-shot MapReduce jobs running periodically to systems that operate in near real-time. Different architectures can lead to surprising and counterintuitive challenges.

Making sure that the data you stored is still there when you want to read it is the heart of data integrity; in Chapter 26, Data Integrity: What You Read Is What You Wrote, we explain how to keep data safe.

Product

Finally, having made our way up the reliability pyramid, we find ourselves at the point of having a workable product. In Chapter 27, Reliable Product Launches at Scale, we write about how Google does reliable product launches at scale to try to give users the best possible experience starting from Day Zero.

Further Reading from Google SRE

As discussed previously, testing is subtle, and its improper execution can have large effects on overall stability. In an ACM article [Kri12], we explain how Google performs company-wide resilience testing to ensure we’re capable of weathering the unexpected should a zombie apocalypse or other disaster strike.

While it’s often thought of as a dark art, full of mystifying spreadsheets divining the future, capacity planning is nonetheless vital, and as [Hix15a] shows, you don’t actually need a crystal ball to do it right.

Finally, an interesting and new approach to corporate network security is detailed in [War14], an initiative to replace privileged intranets with device and user credentials. Driven by SREs at the infrastructure level, this is definitely an approach to keep in mind when you’re creating your next network.

1 Mikey left Google in summer 2014 to become the first administrator of the US Digital Service (https://www.usds.gov), an agency intended (in part) to bring SRE principles and practices to the US government’s IT systems.