New Features and Good Practices

Copyright © 2015 Josh Lockhart. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://safaribooksonline.com). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or corporate@oreilly.com.

See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781491905012 for release details.

The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Modern PHP, the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc.

While the publisher and the author have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the author disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open source licenses or the intellectual property rights of others, it is your responsibility to ensure that your use thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights.

978-1-491-90501-2

[LSI]

For Laurel

There are a million PHP tutorials online. Most of these tutorials are outdated and demonstrate obsolete practices. Unfortunately, these tutorials are still referenced today thanks to their Google immortality. Outdated information is dangerous to unaware PHP programmers who unknowingly create slow and insecure PHP applications. I recognized this issue in 2013, and it is the primary reason I began PHP The Right Way, a community initiative to provide PHP programmers easy access to high-quality and up-to-date information from authoritative members of the PHP community.

Modern PHP is my next endeavor toward the same goal. This book is not a reference manual. Nope. This book is a friendly and fun conversation between you and me. I’ll introduce you to the modern PHP programming language. I’ll show you the latest PHP techniques that I use every day at work and on my open source projects. And I’ll help you use the latest coding standards so you can share your PHP components and libraries with the PHP community.

You’ll hear me say “community” over and over (and over). The PHP community is friendly and helpful and welcoming—although not without occasional drama. If you become curious about a specific feature mentioned in this book, reach out to your local PHP user group with questions. I guarantee you there are nearby PHP developers who would love to help you become a better PHP programmer. Your local PHP user group is an invaluable resource as you continue to improve your PHP skills long after you finish this book.

Before we get started, I want to set a few expectations. First, it is impossible for me to cover every way to use PHP. There isn’t enough time. Instead, I will show you how I use PHP. Yes, this is an opinionated approach, but I use the very same practices and standards adopted by many other PHP developers. What you take away from our brief conversation will be immediately applicable in your own projects.

Second, I assume you are familiar with variables, conditionals, loops, and so on; you don’t have to know PHP, but you should at least bring a basic understanding of these fundamental programming concepts. You can also bring coffee (I love coffee). I’ll supply everything else.

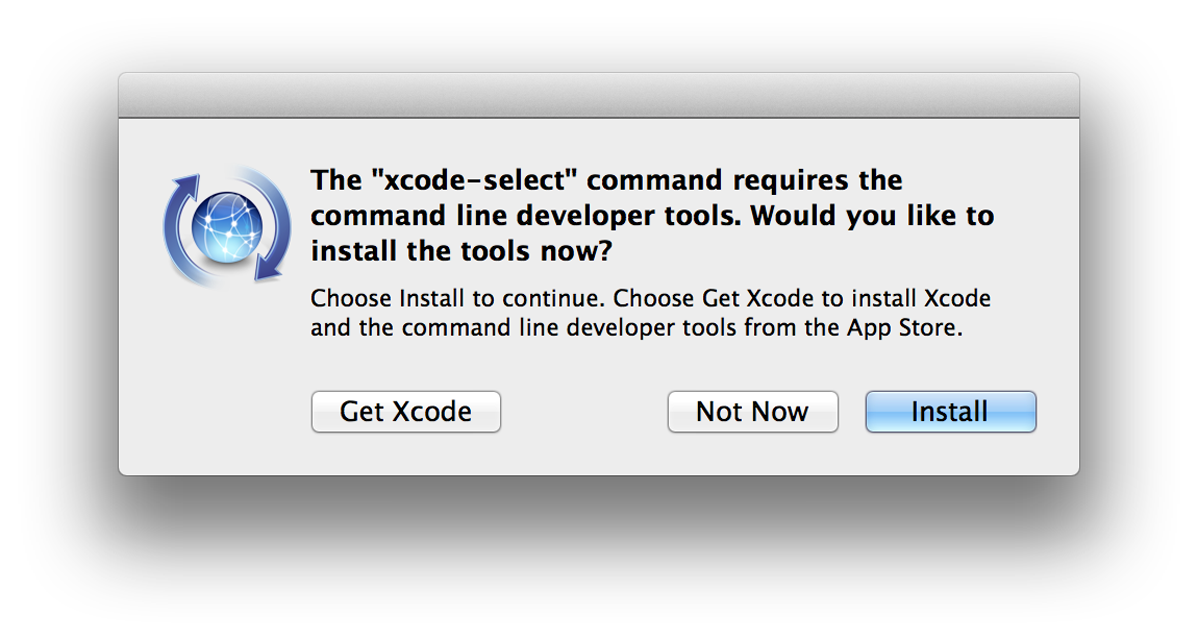

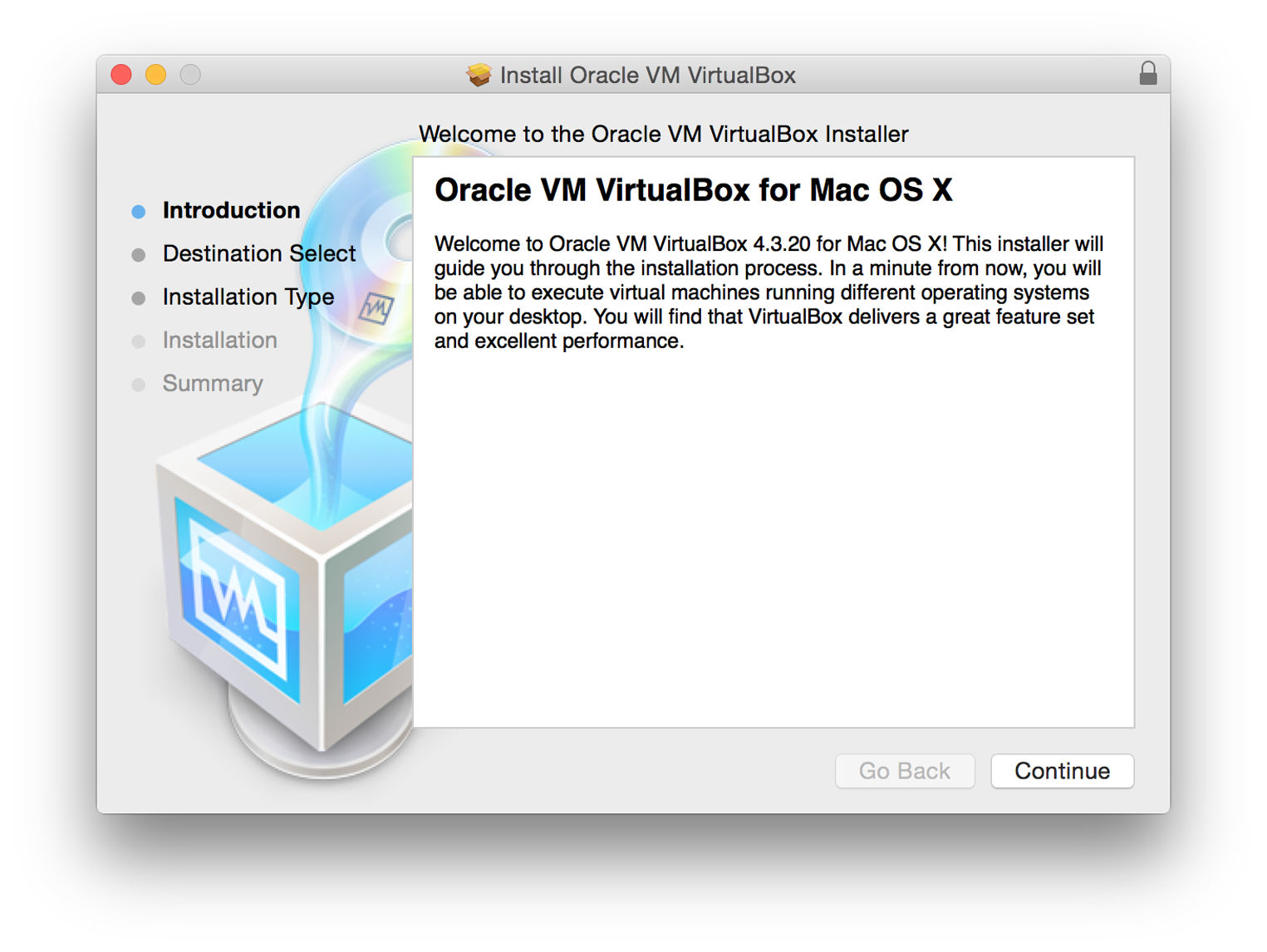

Third, I do not assume you are using a specific operating system. However, my code examples are written for Linux. Bash commands are provided for Ubuntu and CentOS and may also work on OS X. If you use Windows, I highly recommend you spin up a Linux virtual machine so you can run the example code in this book.

Part I demonstrates new PHP features like namespaces, generators, and traits. It introduces you to the modern PHP language, and it exposes you to features you may not have known about until now.

Part II explores good practices that you should implement in your PHP applications. Have you heard the term PSR, but you’re not entirely sure what it is or how to use it? Do you want to learn how to sanitize user input and use safe database queries? This chapter is for you.

Part III is more technical than the first two parts. It demonstrates how to deploy, tune, test, and profile PHP applications. We dive into deployment strategies with Capistrano. We talk about testing tools like PHPUnit and Travis CI. And we explore how to tune PHP so it performs as well as possible for your application.

Appendix A provides step-by-step instructions for installing and configuring PHP-FPM on your machine.

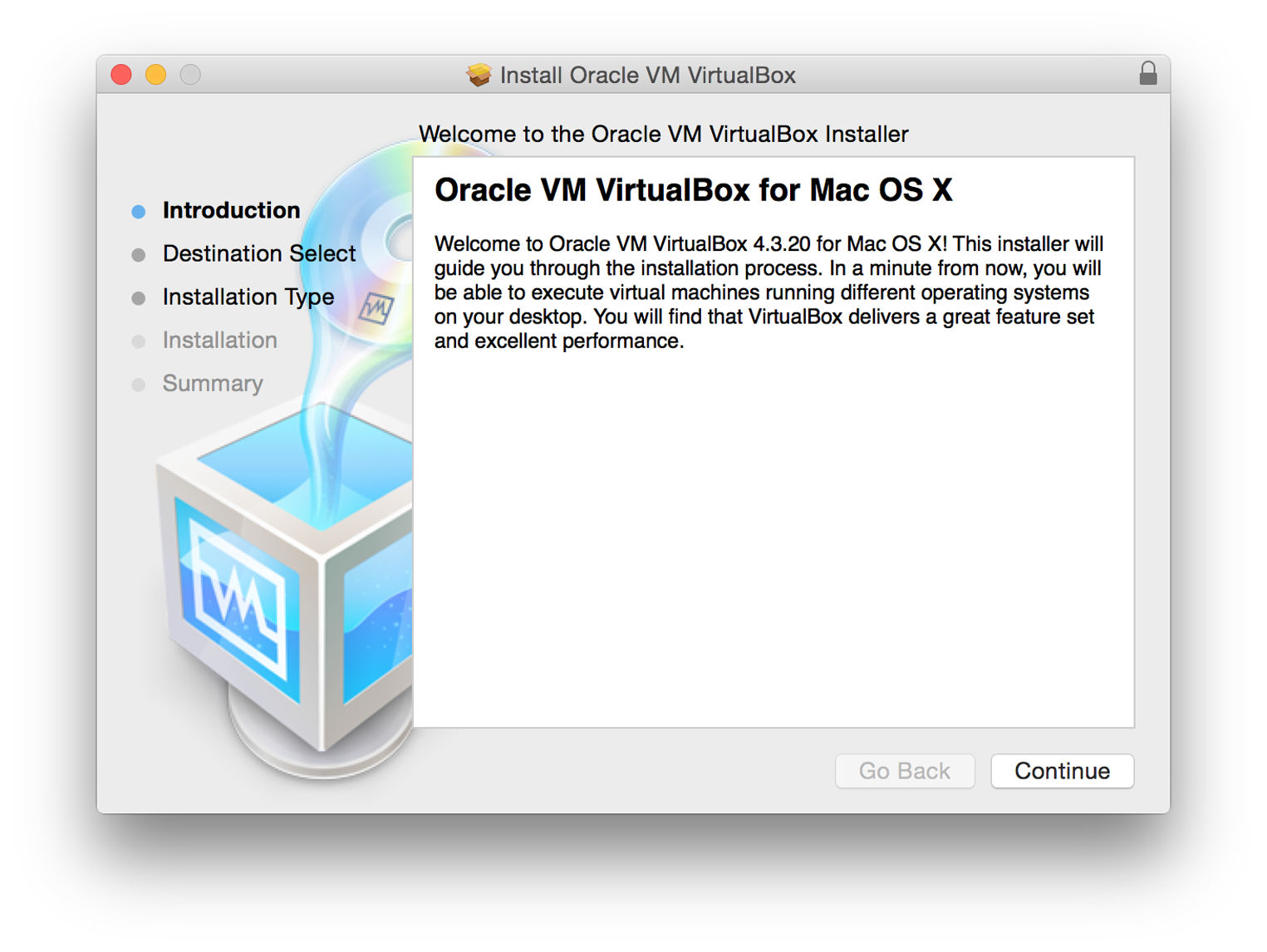

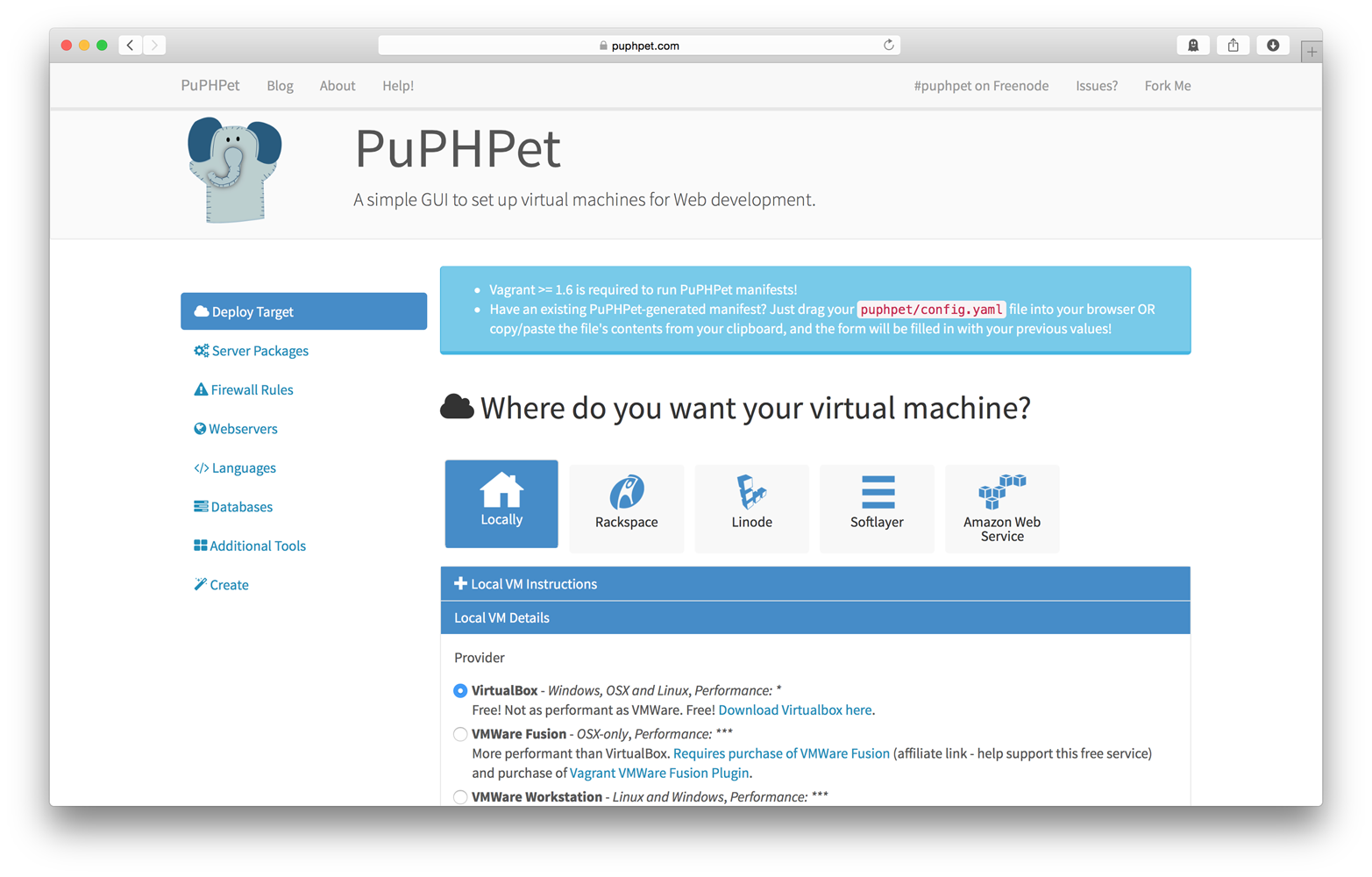

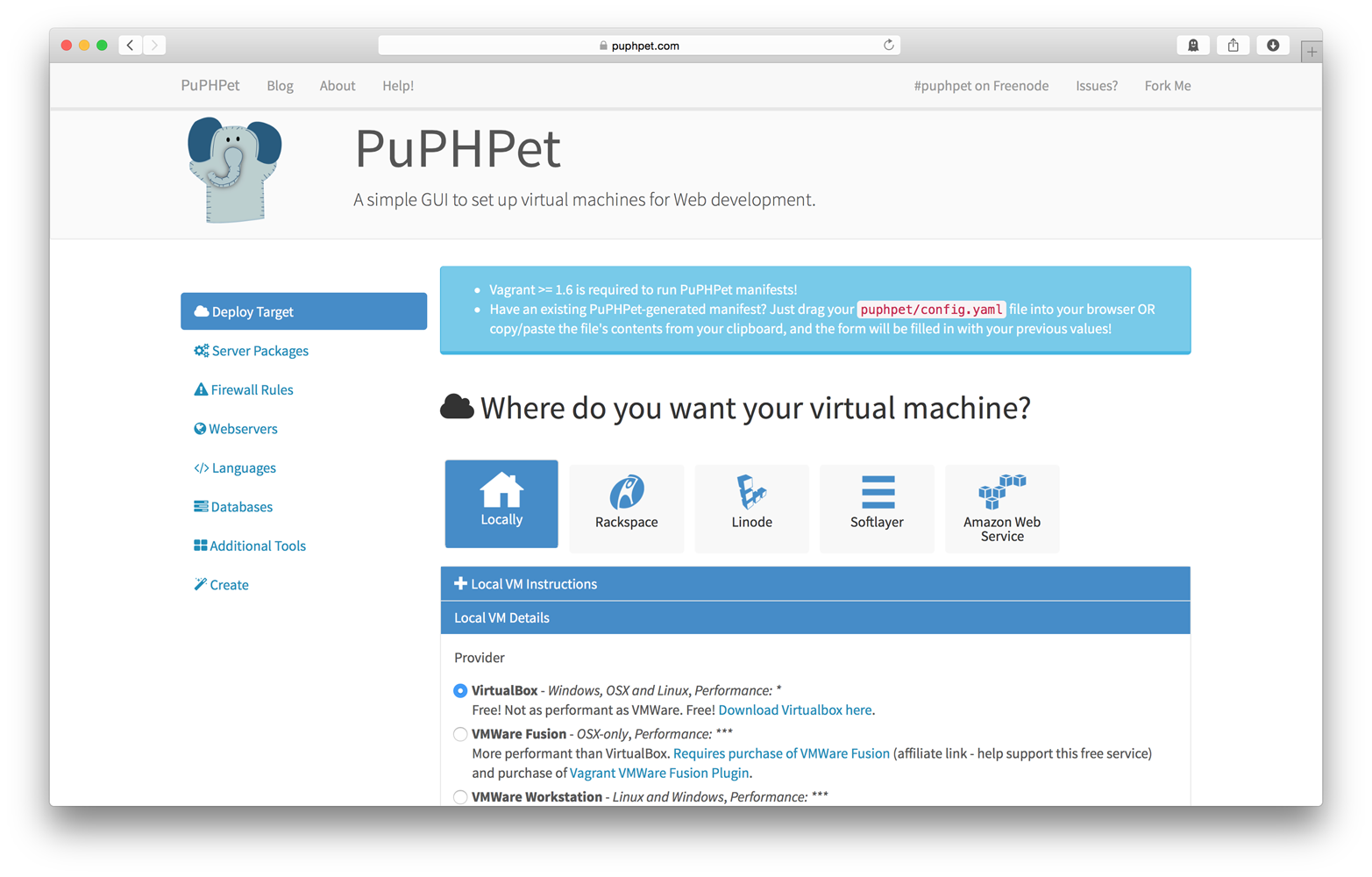

Appendix B explains how to build a local development environment that closely matches your production server. We explore Vagrant, Puppet, Chef, and alternative tools to help you get started quickly.

The following typographical conventions are used in this book:

Indicates new terms, URLs, email addresses, filenames, and file extensions.

Constant widthUsed for program listings, as well as within paragraphs to refer to program elements such as variable or function names, databases, data types, environment variables, statements, and keywords.

Constant width boldShows commands or other text that should be typed literally by the user.

Constant width italicShows text that should be replaced with user-supplied values or by values determined by context.

This element signifies a tip or suggestion.

This element signifies a general note.

This element indicates a warning or caution.

Supplemental material (code examples, exercises, etc.) is available for download at https://github.com/codeguy/modern-php.

This book is here to help you get your job done. In general, if example code is offered with this book, you may use it in your programs and documentation. You do not need to contact us for permission unless you’re reproducing a significant portion of the code. For example, writing a program that uses several chunks of code from this book does not require permission. Selling or distributing a CD-ROM of examples from O’Reilly books does require permission. Answering a question by citing this book and quoting example code does not require permission. Incorporating a significant amount of example code from this book into your product’s documentation does require permission.

We appreciate, but do not require, attribution. An attribution usually includes the title, author, publisher, and ISBN. For example: “Modern PHP by Josh Lockhart (O’Reilly). Copyright 2015 Josh Lockhart, 978-1-491-90501-2.”

If you feel your use of code examples falls outside fair use or the permission given above, feel free to contact us at permissions@oreilly.com.

Safari Books Online is an on-demand digital library that delivers expert content in both book and video form from the world’s leading authors in technology and business.

Technology professionals, software developers, web designers, and business and creative professionals use Safari Books Online as their primary resource for research, problem solving, learning, and certification training.

Safari Books Online offers a range of plans and pricing for enterprise, government, education, and individuals.

Members have access to thousands of books, training videos, and prepublication manuscripts in one fully searchable database from publishers like O’Reilly Media, Prentice Hall Professional, Addison-Wesley Professional, Microsoft Press, Sams, Que, Peachpit Press, Focal Press, Cisco Press, John Wiley & Sons, Syngress, Morgan Kaufmann, IBM Redbooks, Packt, Adobe Press, FT Press, Apress, Manning, New Riders, McGraw-Hill, Jones & Bartlett, Course Technology, and hundreds more. For more information about Safari Books Online, please visit us online.

Please address comments and questions concerning this book to the publisher:

We have a web page for this book, where we list errata, examples, and any additional information. You can access this page at http://bit.ly/modern_php.

To comment or ask technical questions about this book, send email to bookquestions@oreilly.com.

For more information about our books, courses, conferences, and news, see our website at http://www.oreilly.com.

Find us on Facebook: http://facebook.com/oreilly

Follow us on Twitter: http://twitter.com/oreillymedia

Watch us on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/oreillymedia

This is my first book. When O’Reilly approached me about writing Modern PHP, I was equally excited and scared to death. The first thing I did was a Walter Huston dance; I mean, O’Reilly wanted me to write a book. How cool is that!? Then I asked myself can I really write that many pages? A book isn’t a quick or small task.

Of course, I immediately said “yes.” I knew I could write Modern PHP because I had family, friends, coworkers, editors, and reviewers supporting me the entire way. I want to acknowledge and thank my supporters for their invaluable feedback. Without them, this book would never have happened.

First, I want to thank my editor at O’Reilly Media—Allyson MacDonald (@allyatoreilly). Ally was nice, critical, supportive, and smart. She knew exactly how and when to gently nudge me in the right direction whenever I got off track. I can’t imagine working with a better editor.

I also want to thank my technical reviewers—Adam Fairholm (@adamfairholm) and Ed Finkler (@funkatron). Adam is a brilliant web developer at Newfangled, and he is perhaps best known for his work on IMVDb—the popular music video database. Ed is well-known throughout the PHP community for his incredible PHP skills, his personality on the /dev/hell podcast, and his commendable Open Sourcing Mental Illness campaign. Adam and Ed both pointed out everything dumb, illogical, and incorrect in my early drafts. This book is far better than anything I could write on my own thanks to their brutally honest feedback. I am forever indebted to them for their guidance and wisdom. If any faults or inaccuracies wriggled their way into the final manuscript, those faults are surely my own.

My coworkers at New Media Campaigns have been a constant source of encouragement. Joel, Clay, Kris, Alex, Patrick, Ashley, Lenny, Claire, Todd, Pascale, Henry, and Nathan—I tip my hat to all of you for your kind words of encouragement from beginning to end.

And most important, I want to thank my family—Laurel, Ethan, Tessa, Charlie, Lisa, Glenn, and Liz. Thank you for your encouragement, without which I would have never finished this book. To my lovely wife, Laurel, thank you for your patience. Thank you for accompanying me to Caribou Coffee for so many late-night writing sessions. Thank you for letting me abandon you on weekends. Thank you for keeping me motivated and on schedule. I love you now and forever.

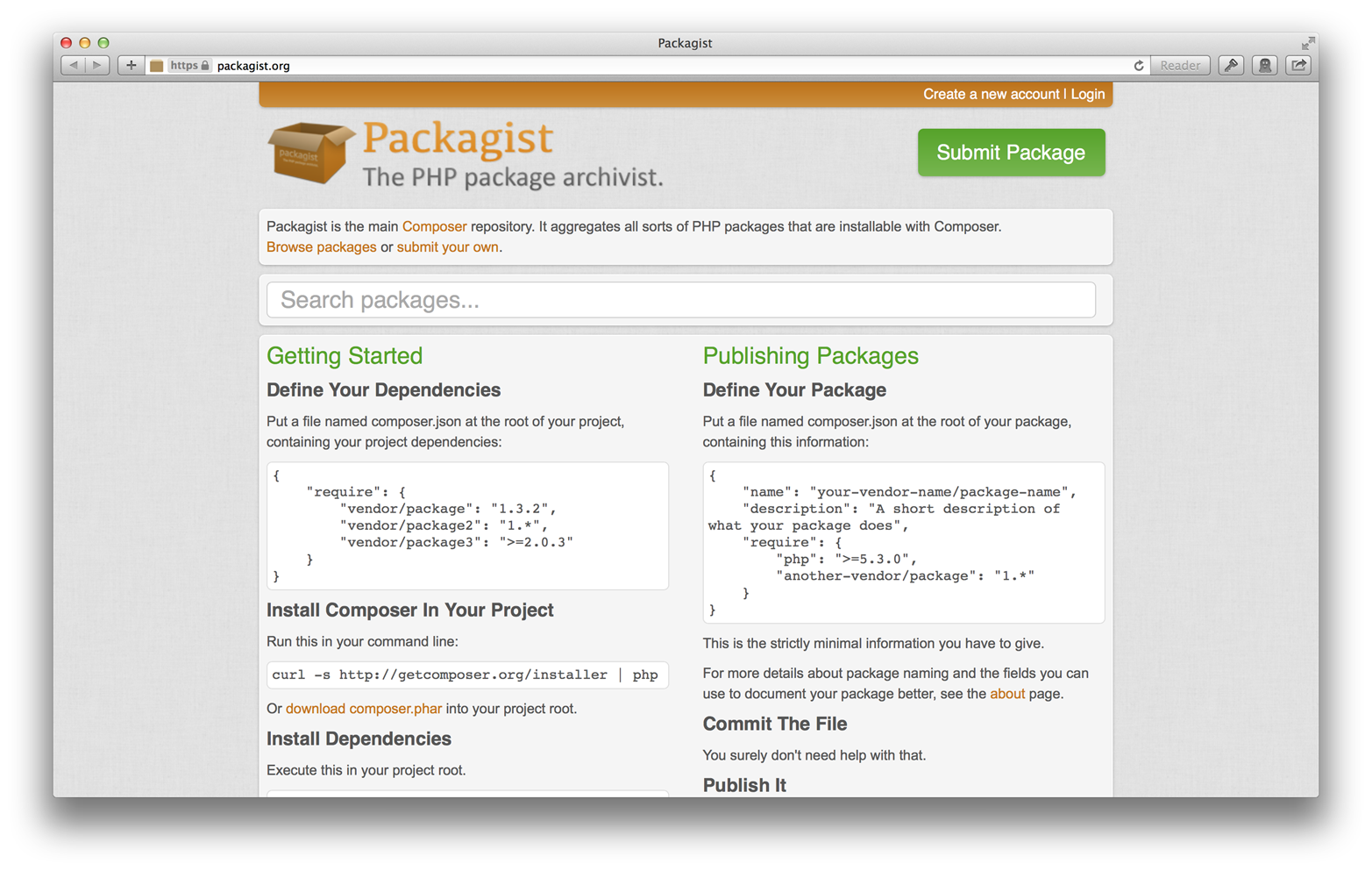

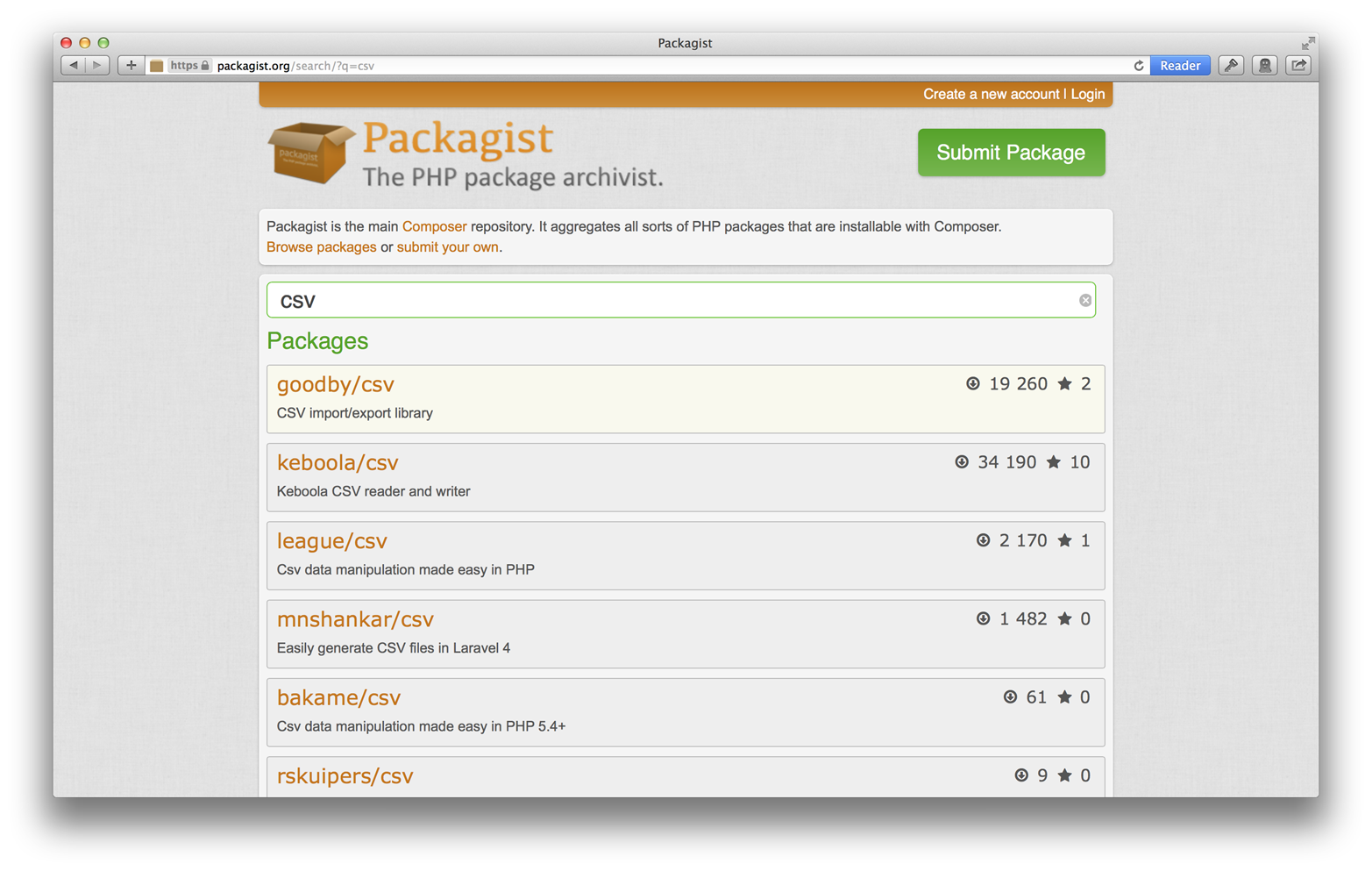

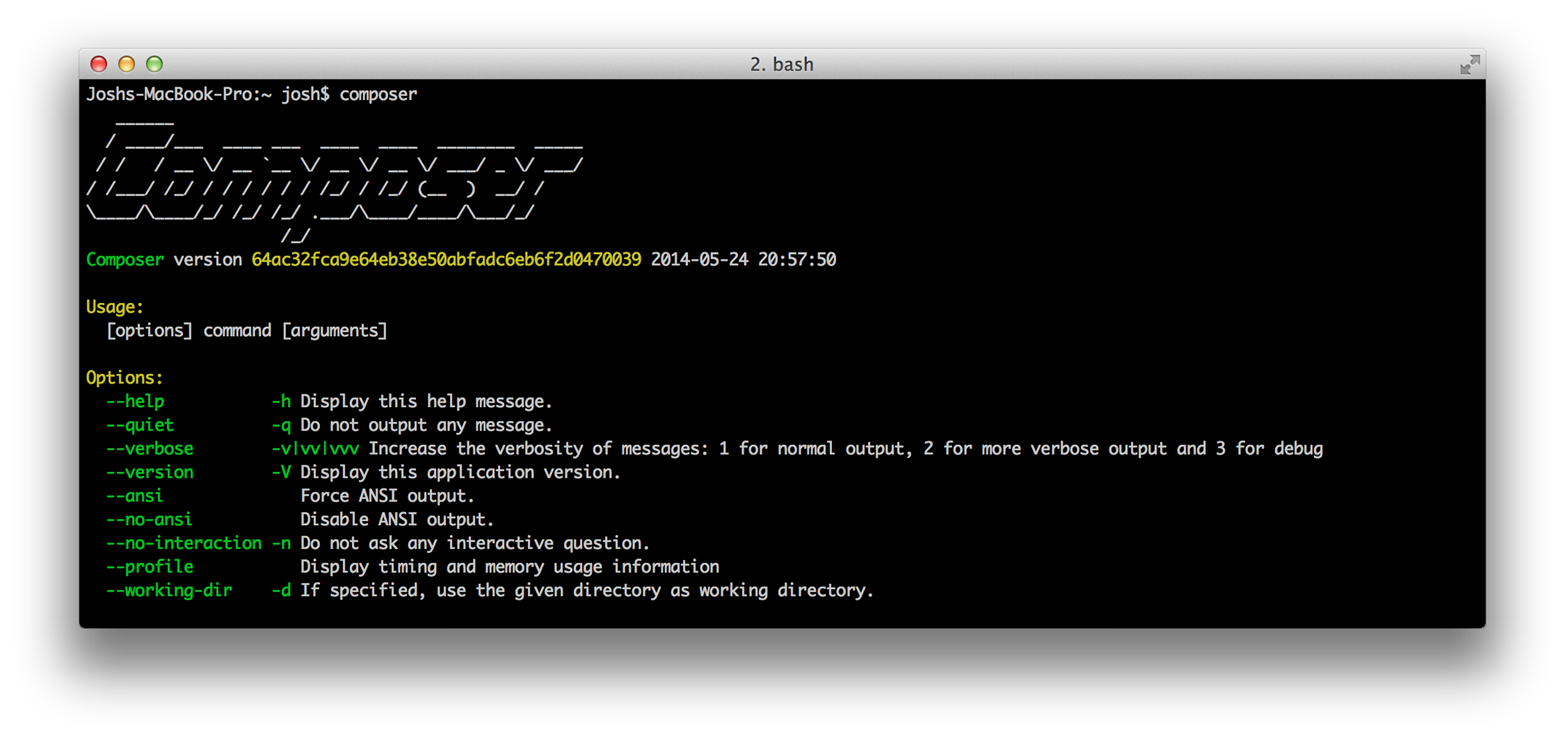

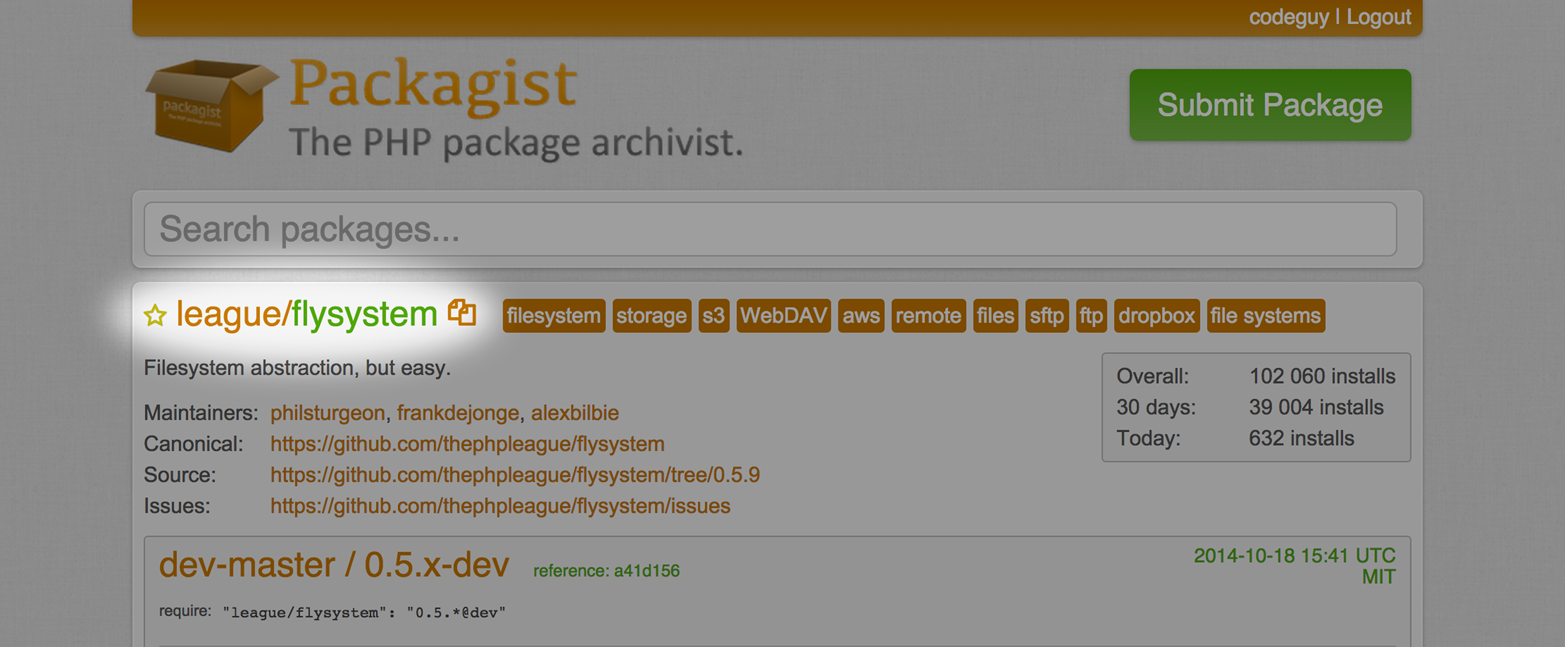

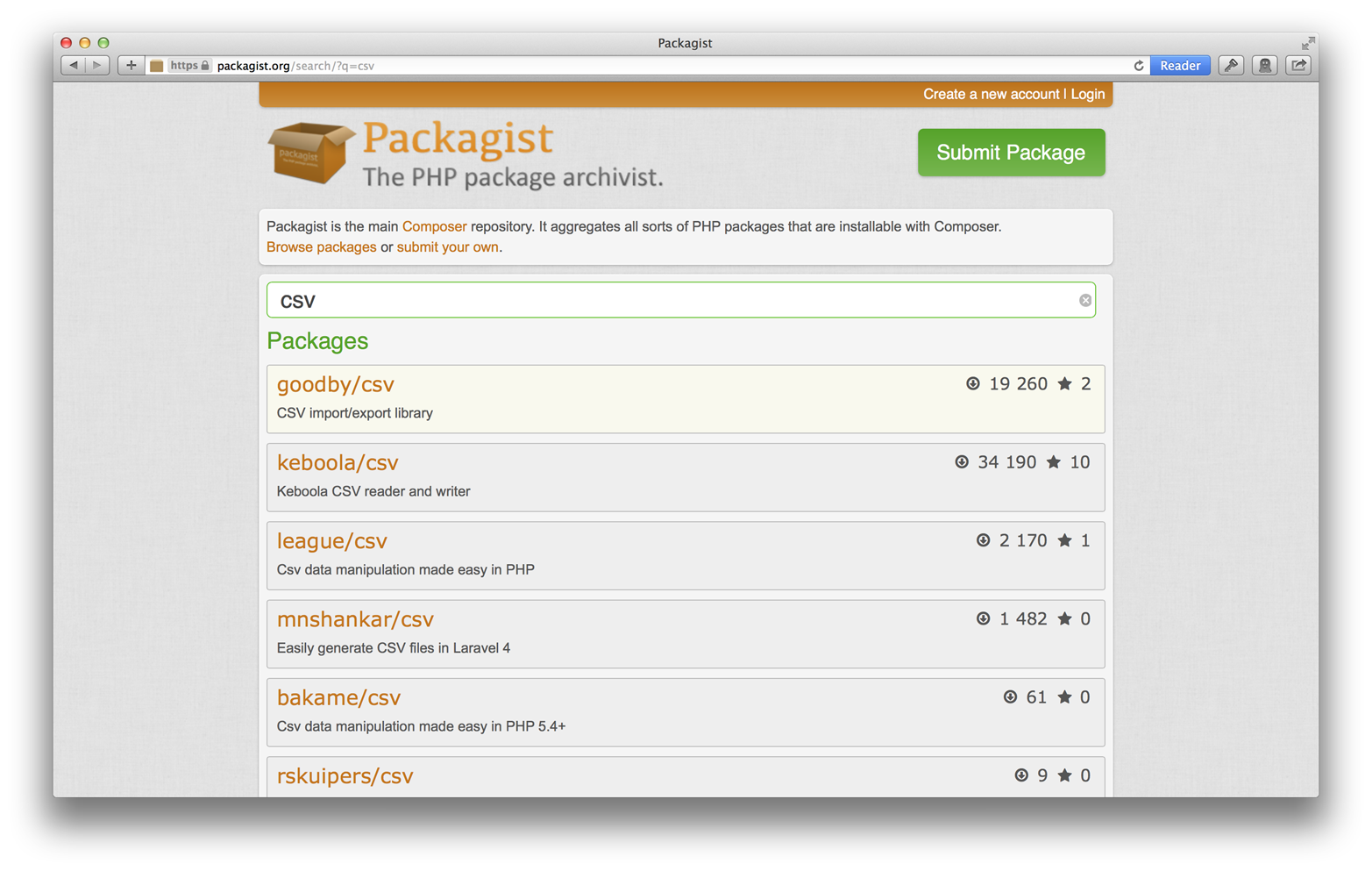

The PHP language is experiencing a renaissance. PHP is transforming into a modern scripting language with helpful features like namespaces, traits, closures, and a built-in opcode cache. The modern PHP ecosystem is evolving, too. PHP developers rely less on monolithic frameworks and more on smaller specialized components. The Composer dependency manager is revolutionizing how we build PHP applications; it emancipates us from a framework’s walled garden and lets us mix and match interoperable PHP components best suited for our custom PHP applications. Component interoperability would not be possible without community standards proposed and curated by the PHP Framework Interop Group.

Modern PHP is your guide to the new PHP, and it will show you how to build and deploy amazing PHP applications using community standards, good practices, and interoperable components.

Before we explore modern PHP, it is important to understand PHP’s origin. PHP is an interpreted server-side scripting language. This means you write PHP code, upload it to a web server, and execute it with an interpreter. PHP is typically used with a web server like Apache or nginx to serve dynamic content. However, PHP can also be used to build powerful command-line applications (just like bash, Ruby, Python, and so on). Many PHP developers don’t realize this and miss out on a really exciting feature. Not you, though.

You can read the official PHP history at http://php.net/manual/history.php.php. I won’t repeat what has already been said so well by Rasmus Lerdorf (the creator of PHP). What I will tell you is that PHP has a tumultuous past. PHP began as a collection of CGI scripts written by Rasmus Lerdorf to track visits to his online resume. Lerdorf named his set of CGI scripts “Personal Home Page Tools.” This early incarnation was completely different from the PHP we know today. Lerdorf’s early PHP Tools were not a scripting language; they were tools that provided rudimentary variables and automatic form variable interpretation using an HTML embedded syntax.

Between 1994 and 1998, PHP underwent numerous revisions and even received a few ground-up rewrites. Andi Gutmans and Zeev Suraski, two developers from Tel Aviv, joined forces with Rasmus Lerdorf to transform PHP from a small collection of CGI tools into a full-fledged programming language with a more consistent syntax and basic support for object-oriented programming. They named their final product PHP 3 and released it in late 1998. The new PHP moniker was a departure from earlier names, and it is a recursive acronym for PHP: Hypertext Preprocessor. PHP 3 was the first version that most resembled the PHP we know today. It provided superior extensibility to various databases, protocols, and APIs. PHP 3’s extensibility attracted many new developers to the project. By late 1998, PHP 3 was already installed on a staggering 10% of the world’s web servers.

Today, the PHP language is quickly evolving and is supported by dozens of core team developers from around the world. Development practices have changed, too. In the past, it was common practice to write a PHP file, upload it to a production server with FTP, and hope it worked. This is a terrible development strategy, but it was necessary due to a lack of viable local development environments.

Nowadays, we eschew FTP and use version control instead. Version control software like Git helps maintain an auditable code history that can be branched, forked, and merged. Local development environments are identical to production servers thanks to virtualization tools like Vagrant and provisioning tools like Ansible, Chef, and Puppet. We leverage specialized PHP components with the Composer dependency manager. Our PHP code adheres to PSRs—community standards managed by the PHP Framework Interop Group. We thoroughly test our code with tools like PHPUnit. We deploy our applications with PHP’s FastCGI process manager behind a web server like nginx. And we increase application performance with an opcode cache.

Modern PHP encompasses many new practices that may be unfamiliar to those of you new to PHP, or to those upgrading from older PHP versions. Don’t feel overwhelmed. I’ll walk through each concept later in this book.

I’m also excited that PHP now has an official draft specification—something it lacked until 2014.

Most mature programming languages have a specification. In layman’s terms, a specification is a canonical blueprint that defines what it means to be PHP. This blueprint is used by developers who create programs that parse, interpret, and execute PHP code. It is not for developers who create applications and websites with PHP.

Sara Golemon and Facebook announced the first PHP specification draft at O’Reilly’s OSCON conference in 2014. You can read the official announcement on the PHP internals mailing list, and you can read the PHP specification on GitHub.

An official PHP language specification is becoming more important given the introduction of multiple competing PHP engines. The original PHP engine is the Zend Engine, a PHP interpreter written in C and introduced in PHP 4. The Zend Engine was created by Rasmus Lerdorf, Andi Gutmans, and Zeev Suraski. Today the Zend Engine is the Zend company’s main contribution to the PHP community. However, there is now a second major PHP engine—the HipHop Virtual Machine from Facebook. A language specification ensures that both engines maintain a baseline compatibility.

A PHP engine is a program that parses, interprets, and executes PHP code (e.g., the Zend Engine or Facebook’s HipHop Virtual Machine). This is not to be confused with PHP, which is a generic reference to the PHP language.

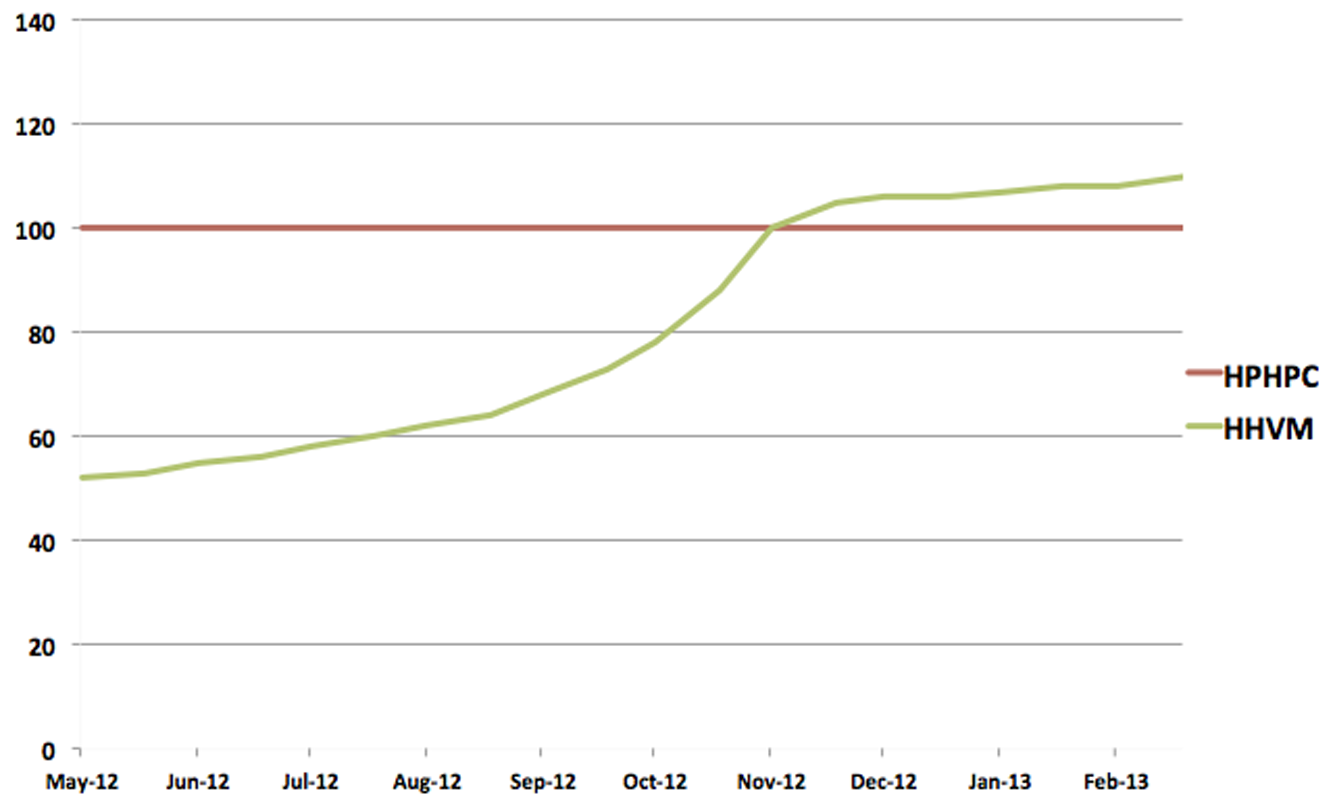

The Zend Engine is improving at a rapid pace with new features and improved performance. I attribute the Zend Engine’s improvements to its new competition, specifically Facebook’s HipHop Virtual Machine and Hack programming language.

Hack is a new programming language built on top of PHP. It introduces static typing, new data structures, and additional interfaces while maintaining backward compatibility with existing dynamically typed PHP code. Hack is targeted at developers who appreciate PHP’s rapid development characteristics but need the predictability and stability from static typing.

We’ll discuss dynamic versus static typing later in this book. The difference between the two is when PHP types are checked. Dynamic types are checked at runtime, whereas static types are checked at compile time. Jump ahead to Chapter 12 for more information.

The HipHop Virtual Machine (HHVM) is a PHP and Hack interpreter that uses a just in time (JIT) compiler to improve application performance and reduce memory usage.

I don’t foresee Hack and HHVM replacing the Zend Engine, but Facebook’s new contributions are creating a giant splash in the PHP community. Increasing competition has prompted the Zend Engine core team to announce PHP 7, an optimized Zend Engine said to be on par with HHVM. We’ll discuss these developments further in Chapter 12.

It’s an exciting time to be a PHP programmer. The PHP community has never been this energized, fun, and innovative. I hope this book helps you firmly embrace modern PHP practices. There are a ton of new things to learn, and many more things on the horizon. Consider this your roadmap. Now let’s get started.

The modern PHP language has many exciting new features. Many of these features will be brand new to PHP programmers upgrading from earlier versions, and they’ll be a nice surprise to programmers migrating to PHP from another language. These new features make the PHP language a powerful platform and provide a pleasant experience for building web applications and command-line tools.

Some of these features aren’t essential, but they still make our lives easier. Some features, however, are essential. Namespaces, for example, are a cornerstone of modern PHP standards and enable development practices that modern PHP developers take for granted (e.g., autoloading). I’ll introduce each new feature, explain why it is useful, and show you how to implement it in your own projects.

I encourage you to follow along on your own computer. You can find all of the text’s code examples in this book’s companion GitHub repository.

If there is one modern PHP feature I want you to know, it is namespaces. Introduced in PHP 5.3.0, namespaces are an important tool that organizes PHP code into a virtual hierarchy, comparable to your operating system’s filesystem directory structure. Each modern PHP component and framework organizes its code beneath its own globally unique vendor namespace so that it does not conflict with, or lay claim to, common class names used by other vendors.

Don’t you hate it when you walk into a coffee shop and this one obnoxious person has a mess of books, cables, and whatnot spread across several tables? Not to mention he’s sitting next to, but not using, the only available power outlet. He’s wasting valuable space that could otherwise be useful to you. Figuratively speaking, this person is not using namespaces. Don’t be this person.

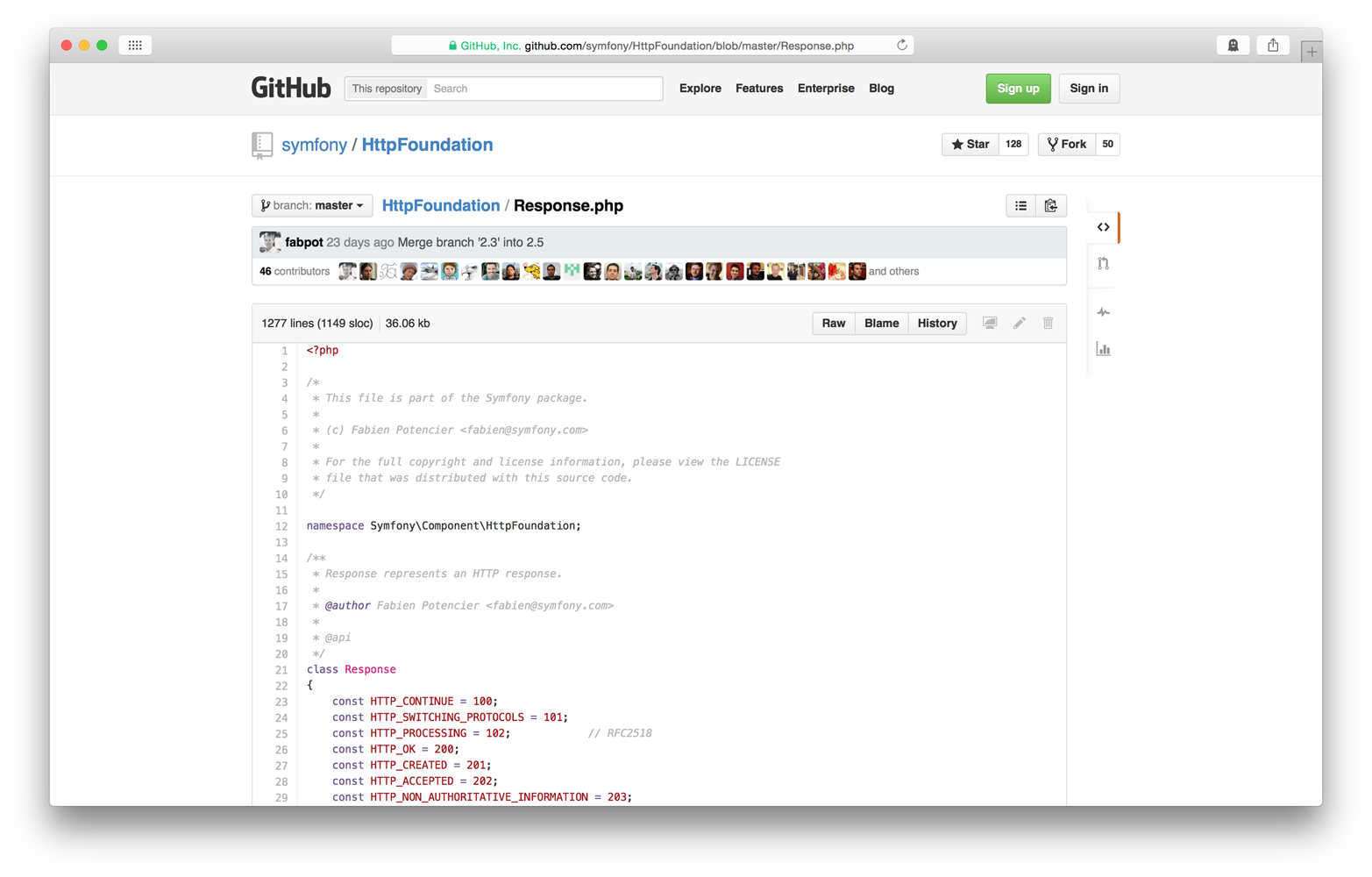

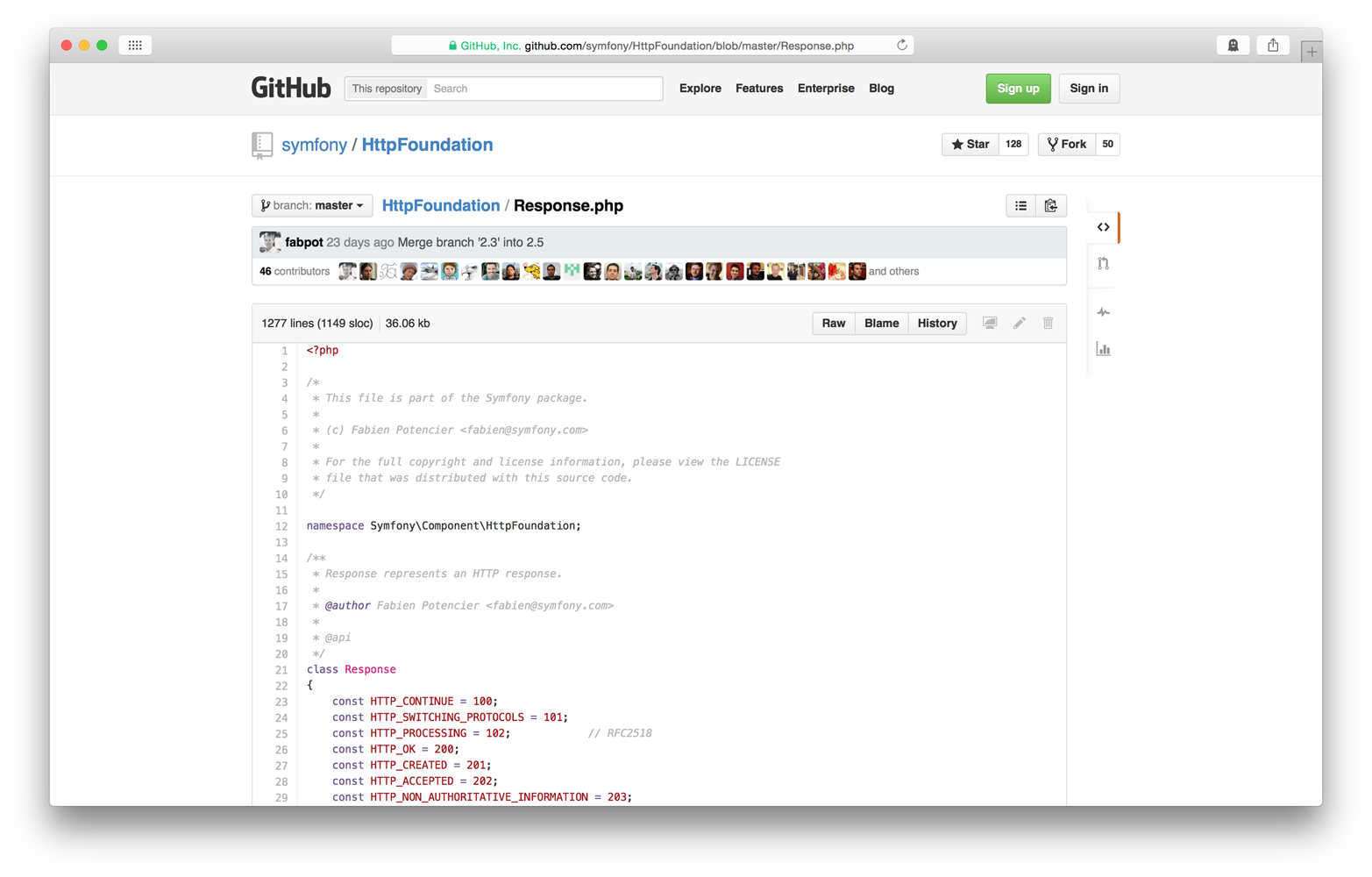

Let’s see how a real-world PHP component uses namespaces. The Symfony Framework’s

own symfony/httpfoundation

is a popular PHP component that manages HTTP requests and responses. More important,

the symfony/httpfoundation component uses common PHP class names like Request,

Response, and Cookie. I guarantee you there are many other PHP components that use

these same class names. How can we use the symfony/httpfoundation PHP component if

other PHP code uses the same class names? We can safely use the symfony/httpfoundation

component precisely because its code is sandboxed beneath the unique Symfony vendor namespace.

Visit the symfony/httpfoundation component on GitHub

and navigate to the Response.php

file. It looks like Figure 2-1.

Look closely at line 12. It contains this code:

namespaceSymfony\Component\HttpFoundation;

This is a PHP namespace declaration, and it always appears on a new line immediately after the

opening <?php tag. This particular namespace declaration tells us several things.

First, we know the Response class lives beneath the Symfony vendor namespace

(the vendor namespace is the topmost namespace). We know the Response class

lives beneath the Component subnamespace. We also know the Response class

lives beneath yet another subnamespace named HttpFoundation. You can view other

files adjacent to Response.php, and you’ll see they use the

same namespace declaration. A namespace (or subnamespace) encapsulates and organizes

related PHP classes, just as a filesystem directory contains related files.

Subnamespaces are separated with a \ character.

Unlike your operating system’s physical filesystem, PHP namespaces are a virtual concept and do not necessarily map 1:1 with filesystem directories. That being said, most PHP components do, in fact, map subnamespaces to filesystem directories for compatibility with the popular PSR-4 autoloader standard (we’ll talk more about this in Chapter 3).

Technically speaking, namespaces are merely a PHP language notation referenced by the PHP interpreter to apply a common name prefix to a set of classes, interfaces, functions, and constants.

Namespaces are important because they let us create sandboxed code that works alongside other developers’ code. This is the cornerstone concept of the modern PHP component ecosystem. Component and framework authors build and distribute code for a large number of PHP developers, and they have no way of knowing or controlling what classes, interfaces, functions, and constants are used alongside their own code. This problem applies to your own in-house projects, too. If you write custom PHP components or classes for a project, that code must work alongside your project’s third-party dependencies.

As I mentioned earlier with the symfony/httpfoundation component, your

code and other developers’ code might use the same class, interface, function,

or constant names. Without namespaces, a name collision causes PHP

to fail. With namespaces, your code and other developers’ code can

use the same class, interface, function, or constant name assuming

your code lives beneath a unique vendor namespace.

If you’re building a tiny personal project with only a few dependencies, class name collisions probably won’t be an issue. But when you’re working on a team building a large project with numerous third-party dependencies, name collisions become a very real concern. You cannot control which classes, interfaces, functions, and constants are introduced into the global namespace by your project’s dependencies. This is why namespacing your code is important.

Every PHP class, interface, function, and constant lives beneath a

namespace (or subnamespace). Namespaces are declared at the top of a

PHP file on a new line immediately after the opening <?php tag.

The namespace declaration begins with namespace, then a space character,

then the namespace name, and then a closing semicolon ;

character.

Remember that namespaces are often used to establish a top-level vendor name.

This example namespace declaration establishes the Oreilly vendor name:

<?phpnamespaceOreilly;

All PHP classes, interfaces, functions, or constants declared

beneath this namespace declaration live in the Oreilly namespace and are,

in some way, related to O’Reilly Media. What if we wanted to organize code

related to this book? We use a subnamespace.

Subnamespaces are declared exactly the same as in the previous example.

The only difference is that we separate namespace and subnamespace names

with the \ character. The following example declares a subnamespace

named ModernPHP that lives beneath the topmost Oreilly vendor namespace:

<?phpnamespaceOreilly\ModernPHP;

All classes, interfaces, functions, and constants declared

beneath this namespace declaration live in the Oreilly\ModernPHP

subnamespace and are, in some way, related to this book.

All classes in the same namespace or subnamespace don’t have to be declared in the same PHP file. You can specify a namespace or subnamespace at the top of any PHP file, and that file’s code becomes a part of that namespace or subnamespace. This makes it possible to write multiple classes in separate files that belong to a common namespace.

Before we had namespaces, PHP developers solved the name collision problem with Zend-style class names. This was a class-naming scheme popularized by the Zend Framework where PHP class names used underscores in lieu of filesystem directory separators. This convention accomplished two things: it ensured class names were unique, and it enabled a naive autoloader implementation that replaced underscores in PHP class names with filesystem directory separators to determine the class file path.

For example, the PHP class Zend_Cloud_DocumentService_Adapter_WindowsAzure_Query

corresponds to the PHP file Zend/Cloud/DocumentService/Adapter/WindowsAzure/Query.php.

A side effect of the Zend-style naming convention, as you can see, is

absurdly long class names. Call me lazy, but there’s no way I’m

typing that class name more than once.

Modern PHP namespaces present a similar problem. For example, the full Response class name

in the symfony\httpfoundation component is \Symfony\Component\HttpFoundation\Response.

Fortunately, PHP lets us import and alias namespaced code.

By import, I mean that I tell PHP which namespaces, classes, interfaces, functions, and constants I will use in each PHP file. I can then use these without typing their full namespaces.

By alias, I mean that I tell PHP that I will reference an imported class, interface, function, or constant with a shorter name.

You can import and alias PHP classes, interfaces, and other namespaces as of PHP 5.3. You can import and alias PHP functions and constants as of PHP 5.6.

The code shown in Example 2-1 creates and sends a 400 Bad Request HTTP response

without importing and aliasing.

<?php$response=new\Symfony\Component\HttpFoundation\Response('Oops',400);$response->send();

This isn’t terrible, but imagine you have to instantiate a Response instance

several times in a single PHP file. Your fingers will get tired quickly.

Now look at Example 2-2. It does the same thing with importing.

<?phpuseSymfony\Component\HttpFoundation\Response;$response=newResponse('Oops',400);$response->send();

We tell PHP we intend to use the Symfony\Component\HttpFoundation\Response class

with the use keyword. We type the long, fully qualified class name once. Then we

can instantiate the Response class without using its fully namespaced class name.

How cool is that?

Some days I feel really lazy. This is a good opportunity to use an alias. Let’s

extend Example 2-2. Instead of typing Response, maybe I just want to

type Res instead. Example 2-3 shows how I can do that.

<?phpuseSymfony\Component\HttpFoundation\ResponseasRes;$r=newRes('Oops',400);$r->send();

In this example, I changed the import line to import the Response class. I also appended

as Res to the end of the import line; this tells PHP to consider Res an alias for

the Response class. If we don’t append the as Res alias to the import line, PHP

assumes a default alias that is the same as the imported class name.

You should import code with the use keyword at the top of each PHP file,

immediately after the opening <?php tag or namespace declaration.

You don’t need a leading \ character when importing code with the use

keyword because PHP assumes imported namespaces are fully qualified.

The use keyword must exist in the global scope (i.e., not inside of

a class or function) because it is used at compile time. It can, however, be

located beneath a namespace declaration to import code into another namespace.

As of PHP 5.6, it’s possible to import functions and constants. This

requires a tweak to the use keyword syntax. To import

a function, change use to use func:

<?phpusefuncNamespace\functionName;functionName();

To import a constant, change use to use constant:

<?phpuseconstantNamespace\CONST_NAME;echoCONST_NAME;

Function and constant aliases work the same as classes.

If you import multiple classes, interfaces, functions, or constants

into a single PHP file, you’ll end up with multiple use statements

at the top of your PHP file. PHP accepts a shorthand import syntax

that combines multiple use statements on a single line like this:

<?phpuseSymfony\Component\HttpFoundation\Request,Symfony\Component\HttpFoundation\Response,Symfony\Component\HttpFoundation\Cookie;

Don’t do this. It’s confusing and easy to mess up. I recommend you keep

each use statement on its own line like this:

<?phpuseSymfony\Component\HttpFoundation\Request;useSymfony\Component\HttpFoundation\Response;useSymfony\Component\HttpFoundation\Cookie;

You’ll type a few extra characters, but your code is easier to read and troubleshoot.

PHP lets you define multiple namespaces in a single PHP file like this:

<?phpnamespaceFoo{// Declare classes, interfaces, functions, and constants here}namespaceBar{// Declare classes, interfaces, functions, and constants here}

This is confusing and violates the recommended one class per file good practice. Use only one namespace per file to make your code simpler and easier to troubleshoot.

If you reference a class, interface, function, or constant without a namespace,

PHP assumes the class, interface, function, or constant lives in the current

namespace. If this assumption is wrong, PHP attempts to resolve the class, interface,

function, or constant. If you need to reference

a namespaced class, interface, function, or constant inside another namespace,

you must use the fully qualified PHP class name (namespace + class name). You

can type the fully qualified PHP class name, or you can import the code

into the current namespace with the use keyword.

Some code might not have a namespace and, therefore, lives in the global namespace.

The native Exception class is a good example. You can reference globally namespaced

code inside another namespace by prepending a \ character to the class, interface, function, or constant

name. For example, the \My\App\Foo::doSomething()

method in Example 2-4 fails because PHP searches for a \My\App\Exception

class that does not exist.

<?phpnamespaceMy\App;classFoo{publicfunctiondoSomething(){$exception=newException();}}

Instead, add a \ prefix to the Exception class name, as shown in Example 2-5. This tells PHP to look for

the Exception class in the global namespace instead of the current namespace.

<?phpnamespaceMy\App;classFoo{publicfunctiondoSomething(){thrownew\Exception();}}

Namespaces also provide the bedrock for the PSR4 autoloader standard created by the PHP Framework Interop Group (PHP-FIG). This autoloader pattern is used by most modern PHP components, and it lets us autoload project dependencies using the Composer dependency manager. We’ll talk about Composer and the PHP-FIG in Chapter 4. For now, just understand that the modern PHP ecosystem and its emerging component-based architecture would be impossible without namespaces.

Learning how to code to an interface changed my life as a PHP programmer, and it profoundly improved my ability to integrate third-party PHP components into my own applications. Interfaces are not a new feature, but they are an important feature that you should know about and use on a daily basis.

So what is a PHP interface? An interface is a contract between two PHP objects that lets one object depend not on what another object is but, instead, on what another object can do. An interface decouples our code from its dependencies, and it allows our code to depend on any third-party code that implements the expected interface. We don’t care how the third-party code implements the interface; we care only that the third-party code does implement the interface. Here’s a more down-to-earth example.

Let’s pretend I just arrived in Miami, Florida for the Sunshine PHP Developer Conference. I need a way to get around town, so I head straight for the local car rental place. They have a tiny Hyundai compact, a Subaru wagon, and (much to my surprise) a Bugatti Veyron. I know I need a way to get around town, and all three vehicles can help me do that. But each vehicle does so differently. The Hyundai Accent is OK, but I’d like something with a bit more oomph. I don’t have kids, so the wagon has more seating than I need. I’ll take the Bugatti, please.

The reality is that I can drive any of these three cars because they all share a common and expected interface. Each car has a steering wheel, a gas pedal, a brake pedal, and turn signals, and each uses gasoline for fuel. The Bugatti is probably more power than I can handle, but the driving interface is the same as the Hyundai’s. Because all three cars share the same expected interface, and I have the opportunity to choose my preferred vehicle (and if we’re being honest, I’d probably go with the Hyundai).

This is the exact same concept in object-oriented PHP. If I write code that expects an object of a specific class (and therefore a specific implementation), my code’s utility is inherently limited because it can only use objects of that one class, forever. However, if I write code that expects an interface, my code immediately knows how to use any object that implements that interface. My code does not care how the interface is implemented; my code cares only that the interface is implemented. Let’s drive this home with a demo.

I have a hypothetical PHP class named DocumentStore that collects text from different

sources: it fetches HTML from remote URLs; it reads stream resources; and it collects

terminal command output. Each document stored in a DocumentStore instance has a unique ID.

Example 2-6 shows the DocumentStore class.

classDocumentStore{protected$data=[];publicfunctionaddDocument(Documentable$document){$key=$document->getId();$value=$document->getContent();$this->data[$key]=$value;}publicfunctiongetDocuments(){return$this->data;}}

How exactly does this work if the addDocument() method only accepts instances of

the Documentable class? That’s a good observation. However, Documentable is not a

class. It’s an interface, and it looks like Example 2-7.

interfaceDocumentable{publicfunctiongetId();publicfunctiongetContent();}

This interface definition says that any object implementing the Documentable interface

must provide a public getId() method and a public getContent() method.

So how exactly is this helpful? It’s helpful because we can create separate document-fetching classes with wildly different implementations. Example 2-8 shows an implementation that can fetch HTML from a remote URL with curl.

classHtmlDocumentimplementsDocumentable{protected$url;publicfunction__construct($url){$this->url=$url;}publicfunctiongetId(){return$this->url;}publicfunctiongetContent(){$ch=curl_init();curl_setopt($ch,CURLOPT_URL,$this->url);curl_setopt($ch,CURLOPT_RETURNTRANSFER,1);curl_setopt($ch,CURLOPT_CONNECTTIMEOUT,3);curl_setopt($ch,CURLOPT_FOLLOWLOCATION,1);curl_setopt($ch,CURLOPT_MAXREDIRS,3);$html=curl_exec($ch);curl_close($ch);return$html;}}

Another implementation (Example 2-9) can read a stream resource.

classStreamDocumentimplementsDocumentable{protected$resource;protected$buffer;publicfunction__construct($resource,$buffer=4096){$this->resource=$resource;$this->buffer=$buffer;}publicfunctiongetId(){return'resource-'.(int)$this->resource;}publicfunctiongetContent(){$streamContent='';rewind($this->resource);while(feof($this->resource)===false){$streamContent.=fread($this->resource,$this->buffer);}return$streamContent;}}

And another implementation (Example 2-10) can fetch the result of a terminal command.

classCommandOutputDocumentimplementsDocumentable{protected$command;publicfunction__construct($command){$this->command=$command;}publicfunctiongetId(){return$this->command;}publicfunctiongetContent(){returnshell_exec($this->command);}}

Example 2-11 shows how we can use the DocumentStore class with our three document-collecting implementations.

<?php$documentStore=newDocumentStore();// Add HTML document$htmlDoc=newHtmlDocument('https://php.net');$documentStore->addDocument($htmlDoc);// Add stream document$streamDoc=newStreamDocument(fopen('stream.txt','rb'));$documentStore->addDocument($streamDoc);// Add terminal command document$cmdDoc=newCommandOutputDocument('cat /etc/hosts');$documentStore->addDocument($cmdDoc);print_r($documentStore->getDocuments());

This is really cool because the HtmlDocument, StreamDocument, and CommandOutputDocument classes

have nothing in common other than a common interface.

At the end of the day, coding to an interface creates more-flexible code that delegates implementation concerns to others. Many more people (e.g., your office buddies, your open source project’s users, or developers you’ve never met) can write code that works seamlessly with your code by knowing nothing more than an interface.

Many of my PHP developer friends are confused by traits, a new concept introduced in PHP 5.4.0. Traits behave like classes but look like interfaces. Which one are they? Neither and both.

A trait is a partial class implementation (i.e., constants, properties, and methods) that can be mixed into one or more existing PHP classes. Traits work double duty: they say what a class can do (like an interface), and they provide a modular implementation (like a class).

You may be familiar with traits in other languages. For example, PHP traits are similar to Ruby’s composable modules, or mixins.

The PHP language uses a classical inheritance model. This means you start with a single generalized root class that provides a base implementation. You extend the root class to create more specialized classes that inherit their immediate parent’s implementation. This is called an inheritance hierarchy, and it is a common pattern used by many programming languages.

If it helps, picture yourself back in grade school Biology. Remember how you learned about the biological classification system? There are six kingdoms. Each kingdom is extended by phyla. Each phylum is extended by biological classes. Classes are extended by orders, orders by families, families by genera, and genera by species. Each hierarchy extension represents further specialization.

The classical inheritance model works well most of the time. However,

what do we do if two unrelated PHP classes need to exhibit similar behavior?

For example, a PHP class RetailStore and another PHP class Car

are very different classes and don’t share a common parent in their

inheritance hierarchies. However, both classes should be geocodable

into latitude and longitude coordinates for display on a map.

Traits were created for exactly this purpose. They enable modular implementations that can be injected into otherwise unrelated classes. Traits also encourage code reuse.

My first (bad) reaction is to create a common parent class Geocodable

that both RetailStore and Car extend. This is a bad solution

because it forces two otherwise unrelated classes to share a common

ancestor that does not naturally belong in either inheritance hierarchy.

My second (better) reaction is to create a Geocodable interface that

defines which methods are required to implement the geocoding behavior.

The RetailStore and Car classes can both implement the Geocodable

interface. This is a good solution that allows each class to retain

its natural inheritance hierarchy, but it requires us to duplicate the

same geocoding behavior in both classes. This is not a DRY solution.

DRY is an acronym for Do not repeat yourself. It’s considered a good practice never to duplicate the same code in multiple locations. You should not need to change code in one location because you changed code in another location. Read more on Wikipedia.

My third (best) reaction is to create a Geocodable trait that defines

and implements the geocodable methods. I can then mix the Geocodable

trait into both the RetailStore and Car classes without polluting

their natural inheritance hierarchies.

Here’s how you define a PHP trait:

<?phptraitMyTrait{// Trait implementation goes here}

It is considered a good practice to define only one trait per file, just like class and interface definitions.

Let’s return to our Geocodable example to better demonstrate traits in

practice. We agree both RetailStore and Car classes need to provide

geocodable behavior, and we’ve decided inheritance and interfaces are

not the best solution. Instead, we create a Geocodable trait that

returns latitude and longitude coordinates that we can plot on a map.

Our complete Geocodable trait looks like Example 2-12.

<?phptraitGeocodable{/** @var string */protected$address;/** @var \Geocoder\Geocoder */protected$geocoder;/** @var \Geocoder\Result\Geocoded */protected$geocoderResult;publicfunctionsetGeocoder(\Geocoder\GeocoderInterface$geocoder){$this->geocoder=$geocoder;}publicfunctionsetAddress($address){$this->address=$address;}publicfunctiongetLatitude(){if(isset($this->geocoderResult)===false){$this->geocodeAddress();}return$this->geocoderResult->getLatitude();}publicfunctiongetLongitude(){if(isset($this->geocoderResult)===false){$this->geocodeAddress();}return$this->geocoderResult->getLongitude();}protectedfunctiongeocodeAddress(){$this->geocoderResult=$this->geocoder->geocode($this->address);returntrue;}}

The Geocodable trait defines only the properties and methods necessary

to implement the geocodable behavior. It does not do anything else.

Our Geocodable trait defines three class properties: an address

(string), a geocoder object (an instance of \Geocoder\Geocoder from

the excellent willdurand/geocoder component by

William Durand), and a geocoder result object (an instance of \Geocoder\Result\Geocoded).

We also define four public methods and one protected method. The setGeocoder() method is

used to inject the Geocoder object. The setAddress() method is used to

set an address. The getLatitude() and getLongitude() methods return

their respective coordinates. And the geocodeAddress() method

passes the address string into the Geocoder instance to retrieve the

geocoder result.

Using a PHP trait is easy. Add the code use MyTrait; inside a

PHP class definition. Here’s an example. Obviously, replace MyTrait

with the appropriate PHP trait name:

<?phpclassMyClass{useMyTrait;// Class implementation goes here}

Both namespaces and traits are imported with the use keyword. Where

they are imported is different. We import namespaces, classes, interfaces,

functions, and constants outside of a class definition. We import traits

inside a class definition. The difference is subtle but important.

Let’s return to our Geocodable example. We defined the Geocodable

trait in Example 2-12. Let’s update our RetailStore class so that it uses the

Geocodable trait (Example 2-13). For the sake of brevity, I do not provide the

complete RetailStore class implementation.

<?phpclassRetailStore{useGeocodable;// Class implementation goes here}

That’s all we have to do. Now each RetailStore instance can use the

properties and methods provided by the Geocodable trait, as shown in Example 2-14.

<?php$geocoderAdapter=new\Geocoder\HttpAdapter\CurlHttpAdapter();$geocoderProvider=new\Geocoder\Provider\GoogleMapsProvider($geocoderAdapter);$geocoder=new\Geocoder\Geocoder($geocoderProvider);$store=newRetailStore();$store->setAddress('420 9th Avenue, New York, NY 10001 USA');$store->setGeocoder($geocoder);$latitude=$store->getLatitude();$longitude=$store->getLongitude();echo$latitude,':',$longitude;

The PHP interpreter copies and pastes traits into class definitions at compile time, and it does not protect against incompatibilities introduced by this action. If your PHP trait assumes a class property or method exists (that is not defined in the trait itself), be sure those properties and methods exist in the appropriate classes.

PHP generators are an underutilized yet remarkably helpful feature introduced in PHP 5.5.0. I think many PHP developers are unaware of generators because their purpose is not immediately obvious. Generators are simple iterators. That’s it.

Unlike your standard PHP iterator, PHP generators don’t require you to

implement the Iterator interface in a heavyweight class. Instead,

generators compute and yield iteration values on-demand. This has

profound implications for application performance. Think about it.

A standard PHP iterator often iterates in-memory, precomputed

data sets. This is inefficient, especially with large and formulaic

data sets that can be computed instead. This is why we use generators

to compute and yield subsequent values on the fly without commandeering

valuable memory.

PHP generators are not a panacea for your iteration needs. Because generators never know the next iteration value until asked, it’s impossible to rewind or fast-forward a generator. You can iterate in only one direction—forward. Generators are also a once-and-done deal. You can’t iterate the same generator more than once. However, you are free to rebuild or clone a generator if necessary.

Generators are easy to create because they are just PHP functions that

use the yield keyword one or more times. Unlike regular PHP functions,

generators never return a value. They only yield values. Example 2-15 shows a simple generator.

<?phpfunctionmyGenerator(){yield'value1';yield'value2';yield'value3';}

Pretty simple, huh? When you invoke the generator function, PHP returns an

object that belongs to the Generator class. This object can be iterated

with the foreach() function. During each iteration, PHP asks the Generator

instance to compute and provide the next iteration value. What’s neat is

that the generator pauses its internal state whenever it yields a value.

The generator resumes internal state when it is asked for the next value. The generator

continues pausing and resuming until it reaches the end of its

function definition or an empty return; statement. We can invoke and

iterate the generator in Example 2-15 like this:

<?phpforeach(myGenerator()as$yieldedValue){echo$yieldedValue,PHP_EOL;}

This outputs:

value1value2value3

I like to demonstrate how a PHP generator saves memory by implementing

a simple range() function. First, let’s do it the wrong way (Example 2-16).

<?phpfunctionmakeRange($length){$dataset=[];for($i=0;$i<$length;$i++){$dataset[]=$i;}return$dataset;}$customRange=makeRange(1000000);foreach($customRangeas$i){echo$i,PHP_EOL;}

Example 2-16 makes poor use of memory. The makeRange() method in Example 2-16 allocates one million integers into a precomputed array.

A PHP generator can do the same thing while allocating memory for only one integer at any given time, as shown in Example 2-17.

<?phpfunctionmakeRange($length){for($i=0;$i<$length;$i++){yield$i;}}foreach(makeRange(1000000)as$i){echo$i,PHP_EOL;}

This is a contrived example. However, just imagine all of the potential data sets that you can compute. Number sequences (e.g., Fibonacci) are an obvious candidate. You can also iterate a stream resource. Imagine you need to iterate a 4 GB comma-separated value (CSV) file and your virtual private server (VPS) has only 1 GB of memory available to PHP. There’s no way you can pull the entire file into memory. Example 2-18 shows how we can use a generator instead!

<?phpfunctiongetRows($file){$handle=fopen($file,'rb');if($handle===false){thrownewException();}while(feof($handle)===false){yieldfgetcsv($handle);}fclose($handle);}foreach(getRows('data.csv')as$row){print_r($row);}

This example allocates memory for only one CSV row at a time instead of reading the entire 4 GB CSV file into memory. It also encapsulates the iteration implementation into a tidy package; this lets us quickly change how we get data (e.g., CSV, XML, JSON) without interrupting our application code that iterates the data.

Generators are a tradeoff between versatility and simplicity. Generators are forward-only iterators. This means you cannot use a generator to rewind, fast-forward, or seek a data set. You can only ask a generator to compute and yield its next value. Generators are most useful for iterating large or numerically sequenced data sets with only a tiny amount of system memory. They are also useful for accomplishing the same simple tasks as larger iterators with less code.

Generators do not add functionality to PHP. You can do what generators

do without a generator. However, generators greatly simply certain tasks

while using less memory. If you require more versatility to rewind,

fast-forward, or seek through a data set, you’re better off writing a

custom class that implements the Iterator interface,

or using one of PHP’s prebuilt Standard PHP Library (SPL) iterators.

For more generator examples, read What Generators Can Do For You by Anthony Ferrara (@ircmaxell on Twitter).

Closures and anonymous functions were introduced in PHP 5.3.0, and they’re two of my favorite and most used PHP features. They sound scary (at least I thought so when I first learned about them), but they’re actually pretty simple to understand. They’re extremely useful tools that every PHP developer should have in the toolbox.

A closure is a function that encapsulates its surrounding state at the time it is created. The encapsulated state exists inside the closure even when the closure lives after its original environment ceases to exist. This is a difficult concept to grasp, but once you do it’ll be a life-changing moment.

An anonymous function is exactly that—a function without a name. Anonymous functions can be assigned to variables and passed around just like any other PHP object. But it’s still a function, so you can invoke it and pass it arguments. Anonymous functions are especially useful as function or method callbacks.

Closures and anonymous functions are, in theory, separate things. However, PHP considers them to be one and the same. So when I say closure, I also mean anonymous function. And vice versa.

PHP closures and anonymous functions use the same syntax as a

function, but don’t let them fool you. They’re actually objects disguised as

PHP functions. If you inspect a PHP closure or anonymous function, you’ll

find they are instances of the Closure class. Closures are considered first-class

value types, just like a string or integer.

So we know PHP closures look like functions. You should not be surprised, then, that you create a PHP closure like Example 2-19.

<?php$closure=function($name){returnsprintf('Hello %s',$name);};echo$closure("Josh");// Outputs --> "Hello Josh"

That’s it. Example 2-19 creates a closure object and assigns it

to the $closure variable. It looks like a standard PHP function:

it uses the same syntax, it accepts arguments, and it returns a value.

However, it does not have a name.

We can invoke the $closure variable because the variable’s value is a closure,

and closure objects implement the \__invoke() magic method. PHP looks for and calls

the __invoke() method whenever () follows a variable name.

I typically use PHP closure objects as function and method callbacks. Many PHP functions expect callback functions, like array_map()

and preg_replace_callback(). This is a perfect opportunity to use PHP anonymous functions!

Remember, closures can be passed into other PHP functions as arguments, just like

any other value. In Example 2-20, I use a closure object as a callback argument

in the array_map() function.

<?php$numbersPlusOne=array_map(function($number){return$number+1;},[1,2,3]);print_r($numbersPlusOne);// Outputs --> [2,3,4]

OK, so that wasn’t that impressive. But remember, before closures PHP developers had no choice but to create a separate named function and refer to that function by name. This was slightly slower to execute, and it segregated a callback’s implementation from its usage. Old-school PHP developers used code like this:

<?php// Named callback implementationfunctionincrementNumber($number){return$number+1;}// Named callback usage$numbersPlusOne=array_map('incrementNumber',[1,2,3]);print_r($numbersPlusOne);

This code works, but it’s not as succinct and tidy as Example 2-20. We don’t need a separate incrementNumber()

named function if we use the function only once as a callback. Closures

used as callbacks create more concise and legible code.

So far I’ve demonstrated nameless (or anonymous) functions used as callbacks.

Let’s explore how to attach and enclose state with a PHP closure. JavaScript developers

might be confused by PHP closures because they do not automatically enclose application

state like true JavaScript closures. Instead, you must manually attach state

to a PHP closure with the closure object’s bindTo() method or the use keyword.

It’s far more common to attach closure state with the use keyword, so let’s look

at that first (Example 2-21). When you attach a variable to a closure via the use keyword, the attached variable

retains the value assigned to it at the time it is attached to the closure.

<?phpfunctionenclosePerson($name){returnfunction($doCommand)use($name){returnsprintf('%s, %s',$name,$doCommand);};}// Enclose "Clay" string in closure$clay=enclosePerson('Clay');// Invoke closure with commandecho$clay('get me sweet tea!');// Outputs --> "Clay, get me sweet tea!"

In Example 2-21, the enclosePerson() named function accepts

a $name argument, and it returns a closure object that encloses

the $name argument. The returned closure object preserves the $name

argument’s value even after the closure exits the enclosePerson()

function’s scope. The $name variable still exists in the closure!

You can pass multiple arguments into a closure with the use keyword.

Separate multiple arguments with a comma, just as you do with

any PHP function or method arguments.

Don’t forget, PHP closures are objects. Each closure instance has its

own internal state that is accessible with the $this keyword just like

any other PHP object. A closure object’s default state is pretty boring;

it has a magic __invoke() method and a bindTo() method. That’s it.

However, the bindTo() method opens the door to some interesting possibilities.

This method lets us bind a Closure object’s internal state to a

different object. The bindTo() method accepts an important second

argument that specifies the PHP class of the object to which the closure

is bound. This lets the closure access protected and private member

variables of the object to which it is bound.

You’ll find the bindTo() method is often used by

PHP frameworks that map route URLs to anonymous callback functions.

Frameworks accept an anonymous function and bind it to the application

object. This lets you reference the primary application object inside the

anonymous function with the $this keyword, as shown in Example 2-22.

01.<?php02.classApp03.{04.protected$routes=array();05.protected$responseStatus='200 OK';06protected$responseContentType='text/html';07.protected$responseBody='Hello world';08.09.publicfunctionaddRoute($routePath,$routeCallback)10.{11.$this->routes[$routePath]=$routeCallback->bindTo($this,__CLASS__);12.}13.14.publicfunctiondispatch($currentPath)15.{16.foreach($this->routesas$routePath=>$callback){17.if($routePath===$currentPath){18.$callback();19.}20.}21.22.header('HTTP/1.1 '.$this->responseStatus);23.header('Content-type: '.$this->responseContentType);24.header('Content-length: '.mb_strlen($this->responseBody));25.echo$this->responseBody;26.}27.}

Pay close attention to the addRoute() method. It accepts a route

path (e.g., /users/josh) and a route callback. The dispatch() method

accepts the current HTTP request path and invokes the matching route callback.

The magic happens on line 11 when we bind the route callback to the current

App instance. This lets us create a callback function that can manipulate

the App instance state:

<?php$app=newApp();$app->addRoute('/users/josh',function(){$this->responseContentType='application/json;charset=utf8';$this->responseBody='{"name": "Josh"}';});$app->dispatch('/users/josh');

Bytecode caches are not new to PHP. We’ve had optional standalone extensions like Alternative PHP Cache (APC), eAccelerator, ionCube, and XCache. But none of these was built into the PHP core distribution until now. As of PHP 5.5.0, PHP has its own built-in bytecode cache called Zend OPcache.

First, let me explain what a bytecode cache is and why it is important. PHP is an interpreted language. When the PHP interpreter executes a PHP script, the interpreter parses the PHP script code, compiles the PHP code into a set of existing Zend Opcodes (machine-code instructions), and executes the bytecode. This happens for each PHP file during every request. This is a lot of overhead, especially if PHP must parse, compile, and execute PHP scripts over and over again for every HTTP request. If only there were a way to cache precompiled bytecode to reduce application response times and reduce stress on our system resources. You’re in luck.

A bytecode cache stores precompiled PHP bytecode. This means the PHP interpreter does not need to read, parse, and compile PHP code on every request. Instead, the PHP interpreter can read the precompiled bytecode from memory and execute it immediately. This is a huge timesaver and can drastically improve application performance.

Zend OPcache isn’t enabled by default; you must explicitly enable Zend OPcache when you compile PHP.

If you choose a shared web host, be sure you choose a good hosting company that provides PHP 5.5.0 or newer with Zend OPcache enabled.

If you compile PHP yourself (i.e., on a VPS or dedicated server),

you must include this option in your PHP ./configure command:

--enable-opcacheAfter you compile PHP, you must also specify the path to the Zend OPcache extension in your php.ini file with this line:

zend_extension=/path/to/opcache.so

The Zend OPcache extension file path is displayed immediately after PHP compiles successfully. If you forget to look for this as I often do, you can also find the PHP extension directory with this command:

php-config --extension-dir

If you use the popular Xdebug profiler by the incomparable Derick Rethans, your php.ini file must load the Zend OPcache extension before Xdebug.

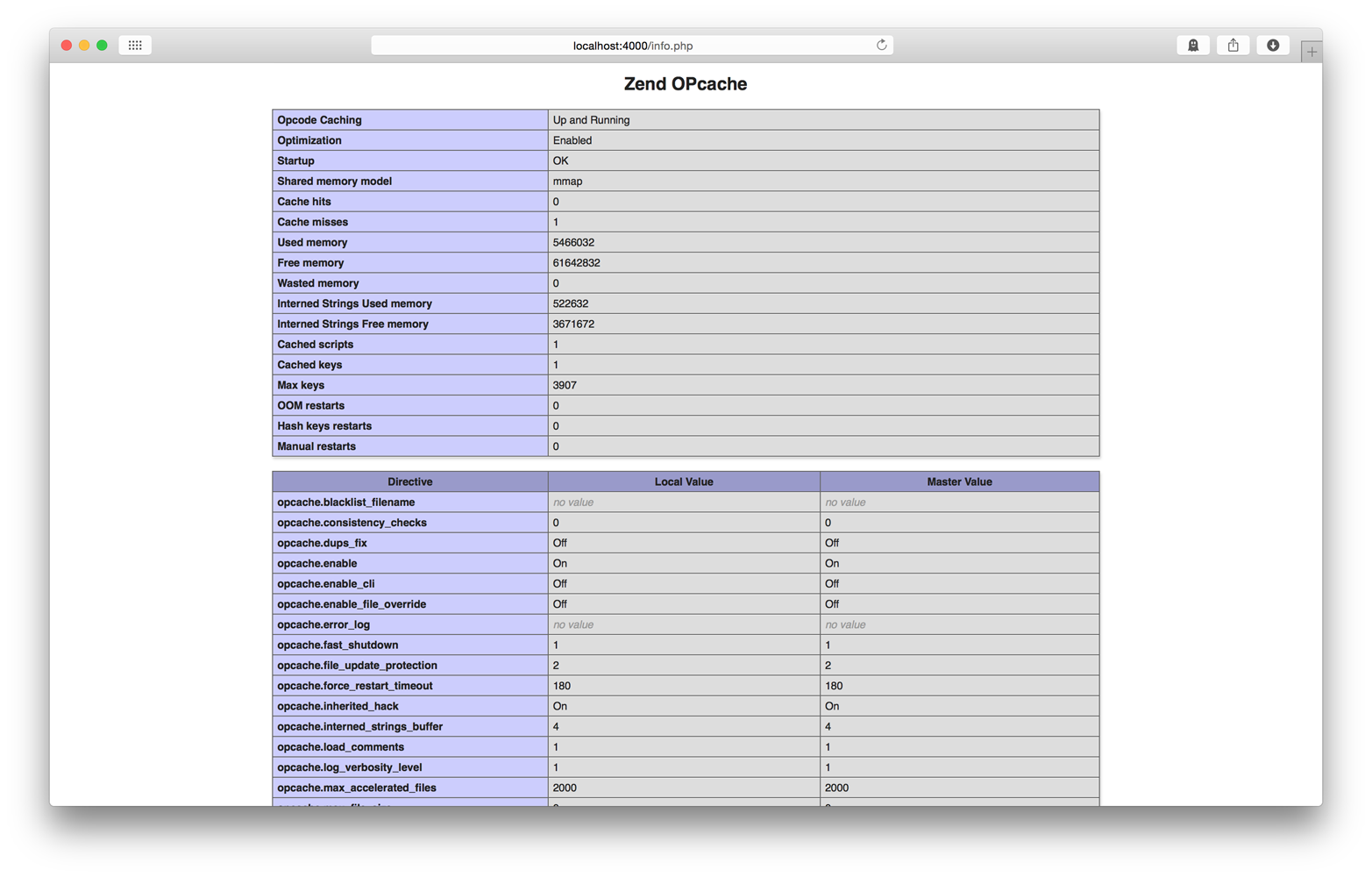

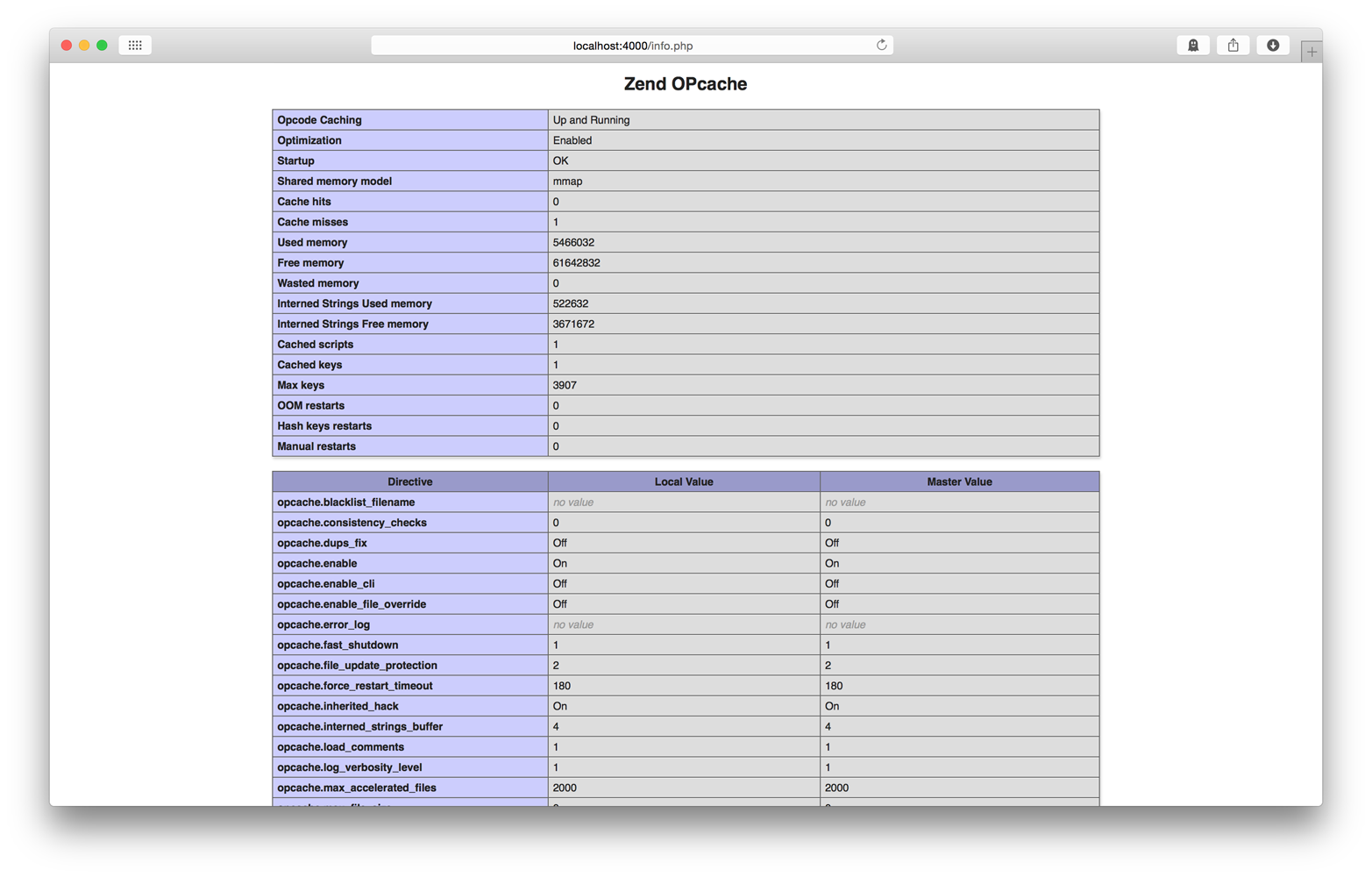

After you update the php.ini file, restart the PHP process and you’re ready to go. You can confirm Zend OPcache is working correctly by creating a PHP file with this content:

<?phpphpinfo();

View this PHP file in a web browser and scroll down until you see the Zend OPcache extension section shown in Figure 2-2. If you don’t see this section, Zend OPcache is not running.

When Zend OPcache is enabled, you should configure the Zend OPcache settings in your php.ini configuration file. Here are the OPcache settings I like to use:

opcache.validate_timestamps=1 // "0" in productionopcache.revalidate_freq=0opcache.memory_consumption=64opcache.interned_strings_buffer=16opcache.max_accelerated_files=4000opcache.fast_shutdown=1

This part’s easy because the Zend OPcache works automatically when enabled. Zend OPcache automatically caches precompiled PHP bytecode in memory and executes the bytecode if available.

Be careful if the opcache.validate_timestamps INI directive is false. When

this setting is false, the Zend OPcache does not know about changes to your

PHP scripts, and you must manually clear Zend OPcache’s bytecode cache before

it recognizes changes to your PHP files. This setting is good for production

but inconvenient for development. You can enable automatic cache revalidation

with these php.ini configuration settings:

opcache.validate_timestamps=1opcache.revalidate_freq=0

Did you know that PHP has a built-in web server as of PHP 5.4.0? This is another hidden gem unknown to PHP developers who assume they need Apache or nginx to preview PHP applications. You shouldn’t use it for production, but PHP’s built-in web server is a perfect tool for local development.

I use PHP’s built-in web server every day, whether I’m writing PHP or not. I use it to preview Laravel and Slim Framework applications. I use it while building websites with the Drupal content-management framework. I also use it to preview static HTML and CSS if I’m just building out markup.

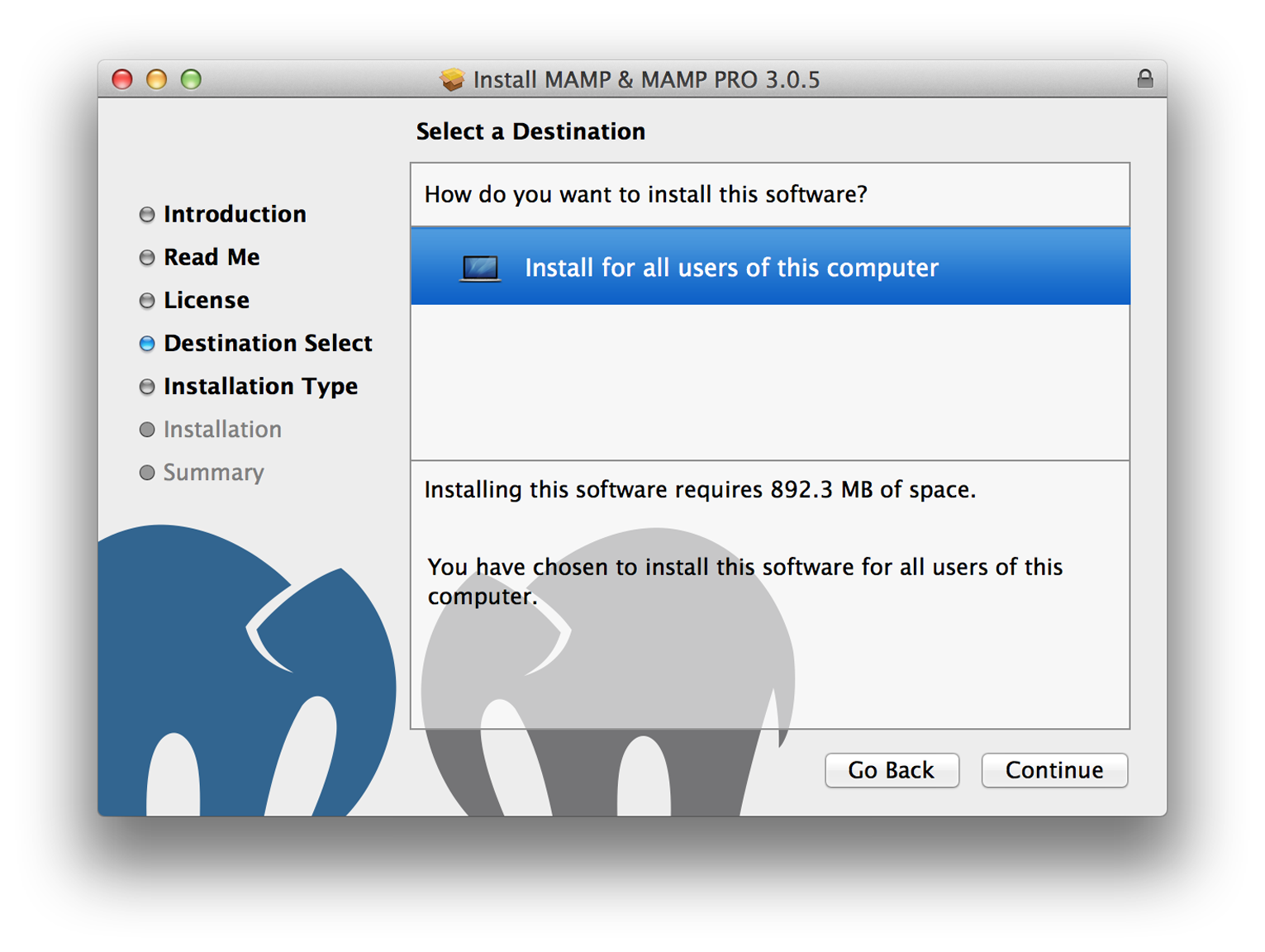

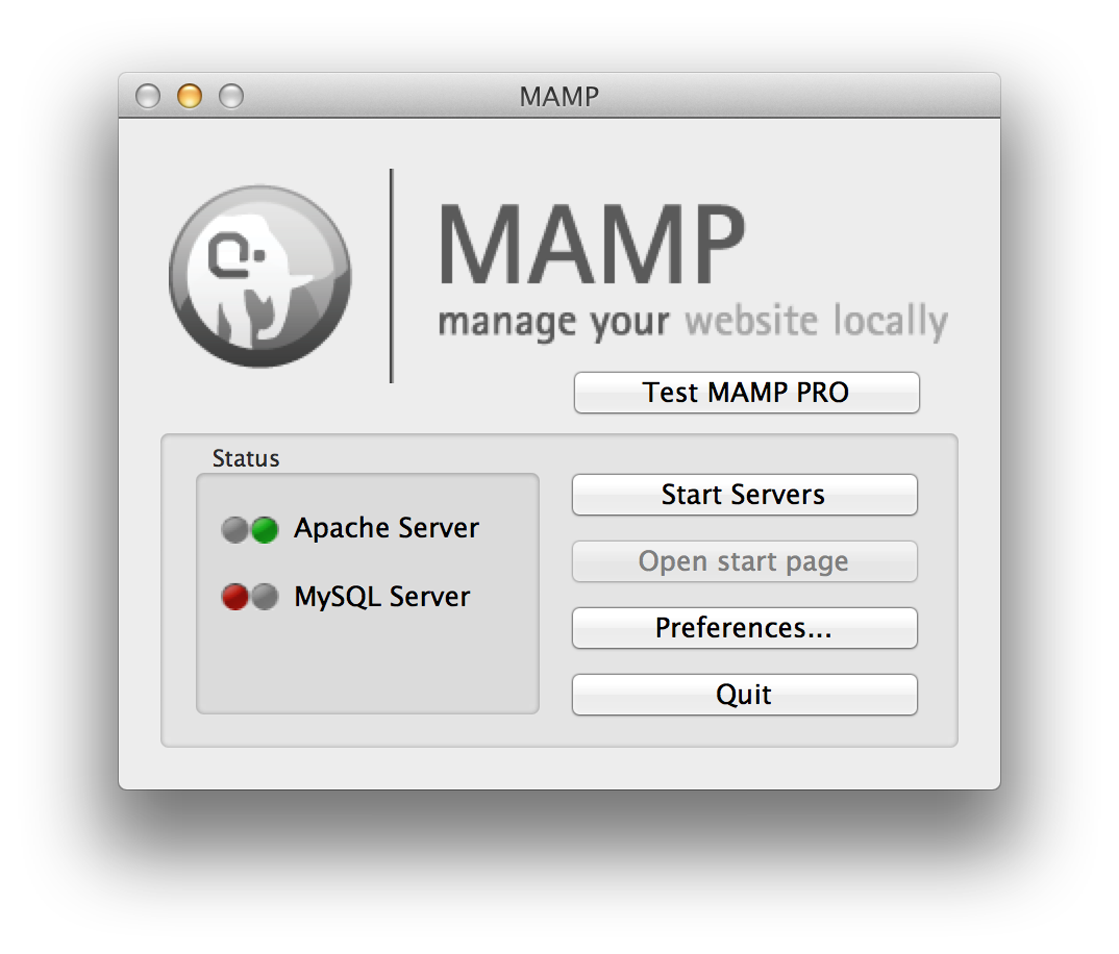

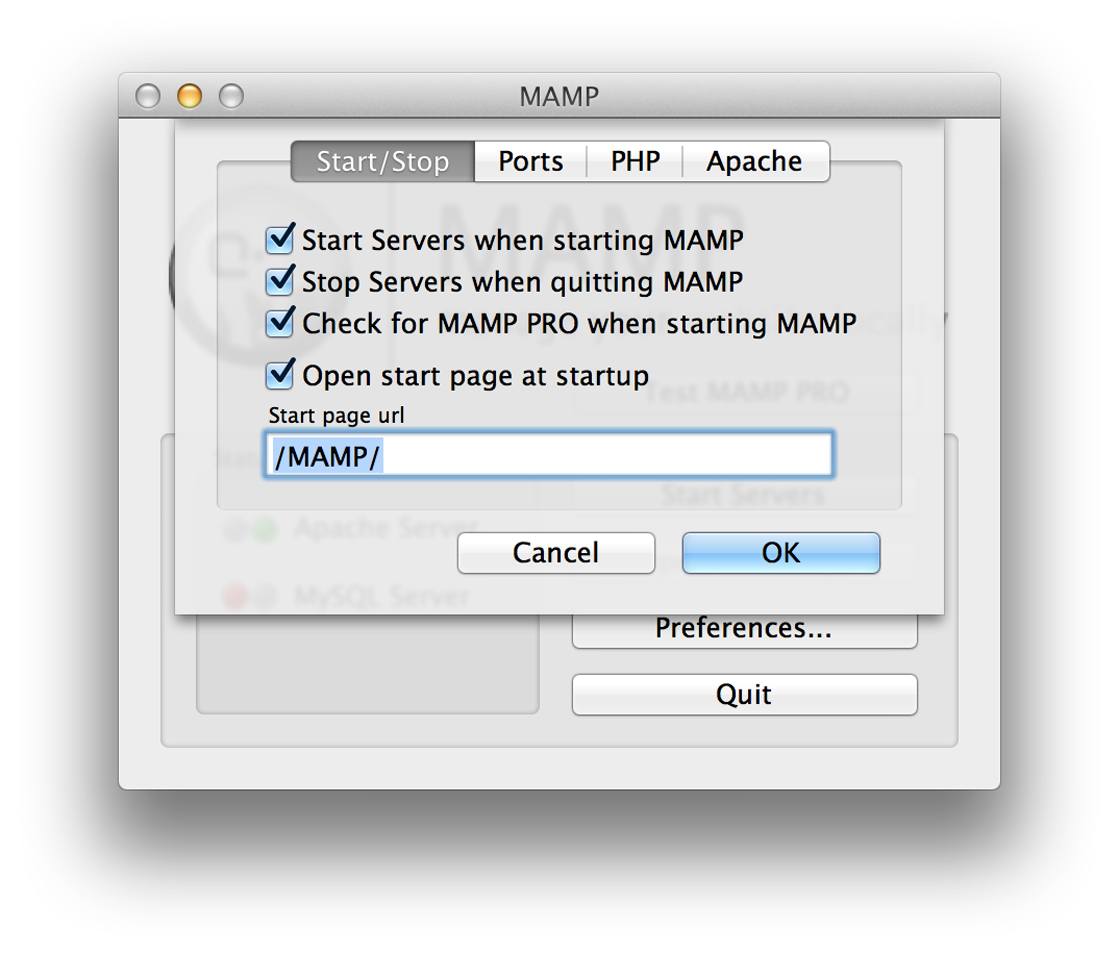

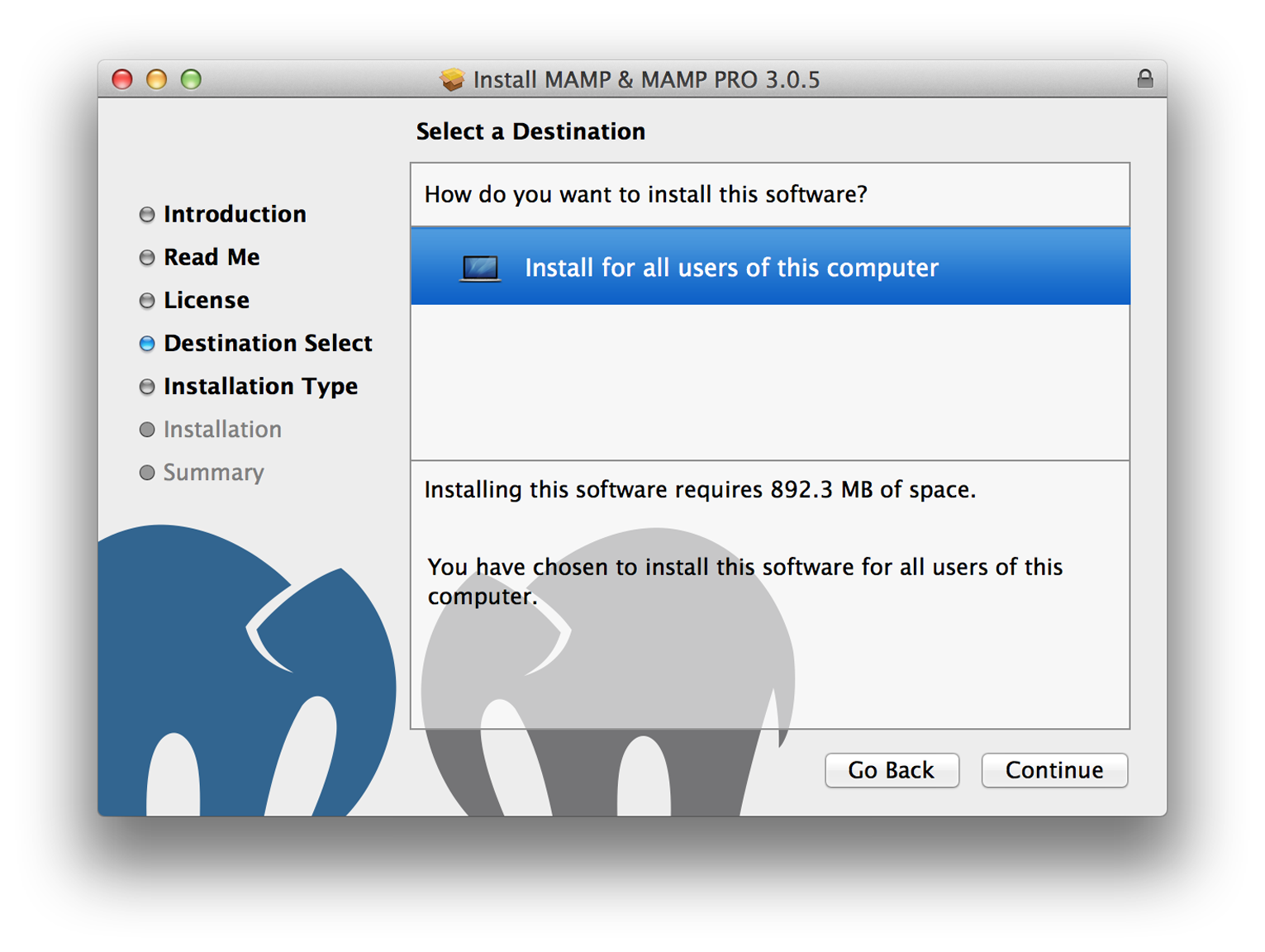

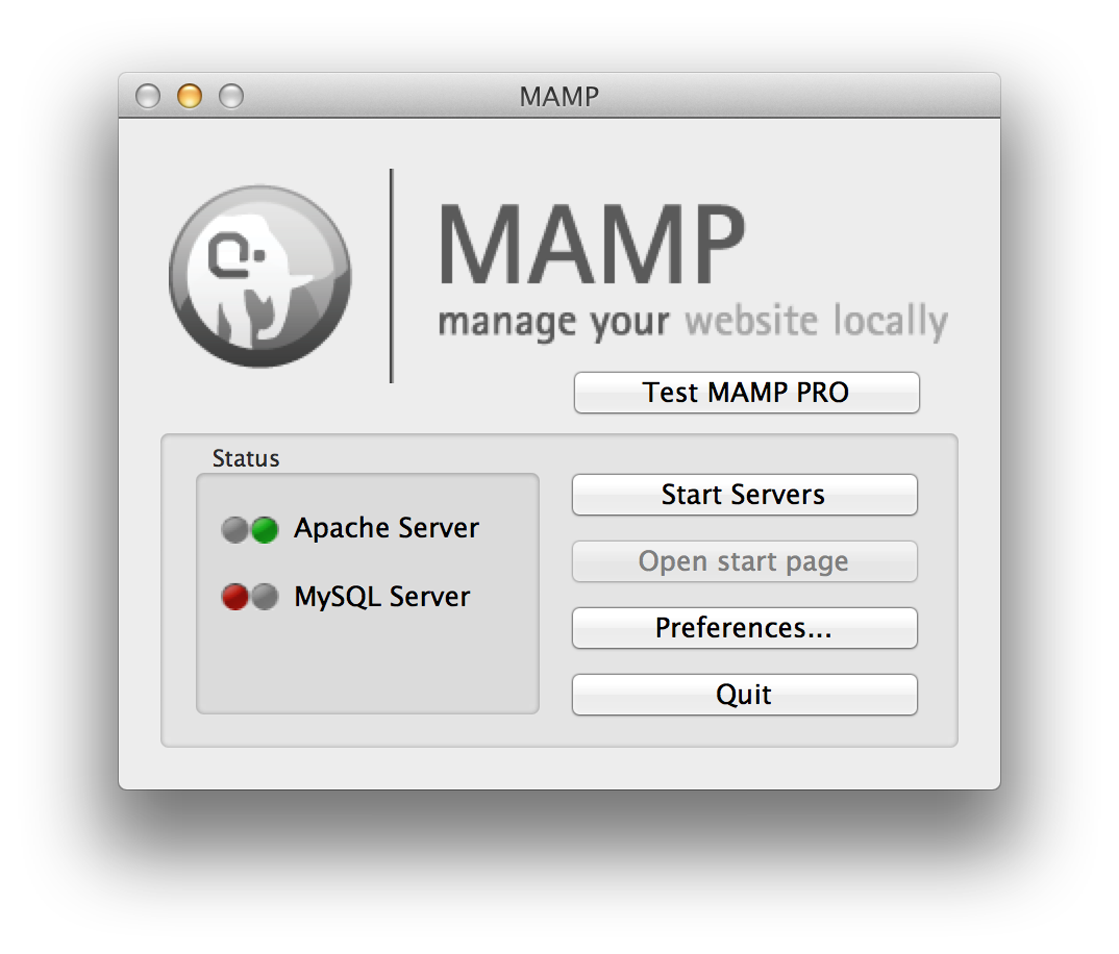

Remember, the PHP built-in server is a web server. It speaks HTTP, and it can serve static assets in addition to PHP files. It’s a great way to write and preview HTML locally without installing MAMP, WAMP, or a heavyweight web server.

It’s easy to start the PHP web server. Open your terminal application, navigate to your project’s document root directory, and execute this command:

php -S localhost:4000

This command starts a new PHP web server accessible at localhost. It listens on port 4000. Your current working directory is the web server’s document root.

You can now open your web browser and navigate to http://localhost:4000 to

preview your application. As you browse your application in your web browser, each

HTTP request is logged to standard out in your terminal application so you can see

if you application throws 400 or 500 responses.

Sometimes it’s useful to access the PHP web server from other machines

on your local network (e.g., for previewing on your iPad or local Windows box).

To do this, tell the PHP web server to listen on all interfaces by using

0.0.0.0 instead of localhost:

php-S0.0.0.0:4000

When you are ready to stop the PHP web server, close your terminal application or press Ctrl+C.

It’s not uncommon for an application to require its own

PHP INI configuration file, especially if it has unique

requirements for memory usage, file uploads, profiling,

or bytecode caching. You can tell the PHP built-in

server to use a specific INI file with the -c option:

php -S localhost:8000 -c app/config/php.ini

It’s a good idea to keep the custom INI file beneath the application’s root directory and, optionally, version-control the INI file if it should be shared with other developers on your team.

The PHP built-in server has one glaring omission. Unlike Apache or nginx, it doesn’t support .htaccess files. This makes it difficult to use front controllers that are common in many popular PHP frameworks.

A front controller is a single PHP file to which all HTTP requests are forwarded (via .htaccess files or rewrite rules). The front-controller PHP file is responsible for routing the request and dispatching the appropriate PHP code. This is a common pattern used by Symfony and other popular frameworks.

The PHP built-in server mitigates this omission with router scripts. The router script is executed before every HTTP request. If the router script returns false, the static asset referenced by the current HTTP request URI is returned. Otherwise, the output of the router script is returned as the HTTP response body. In other words, if you use a router script you’re effectively hardcoding the same functionality as an .htaccess file.

Using a router script is easy. Just pass the PHP script file path as a an argument when you start up the PHP built-in server:

php -S localhost:8000 router.php

Sometimes it’s helpful to know if your PHP script is served by PHP’s

built-in web server versus a traditional web server like Apache or

nginx. Perhaps you need to set specific headers for nginx (e.g.,

Status:) that should not be set for the PHP web server. You can detect

the PHP web server with the php_sapi_name() function. This function

returns the string cli-server if the current script is served with

the PHP built-in server:

<?phpif(php_sapi_name()==='cli-server'){// PHP web server}else{// Other web server}

PHP’s built-in web server should not be used for production. It is for local development only. If you use the PHP built-in web server on a production machine, be prepared for a lot of disappointed users and a flood of Pingdom downtime notifications.

The built-in server performs suboptimally because it handles one request at a time, and each HTTP request is blocking. Your web application will stall if a PHP file must wait on a slow database query or remote API response.

The built-in server supports only a limited number of mimetypes.

The built-in server has limited URL rewriting with router scripts. You’ll need Apache or nginx for more advanced URL rewrite behavior.

The modern PHP language has a lot of powerful features that can improve your applications. I’ve talked about my favorite features in this chapter. You can learn more about PHP’s latest features on the PHP website.

I’m sure you’re excited to start using these fun features in your applications. However, it’s important that you use these features correctly according to PHP community standards. And that’s exactly what we talk about in the next chapter.

There is a mind-boggling number of PHP components and frameworks. There are macro frameworks like Symfony and Laravel. There are micro frameworks like Silex and Slim. And there are legacy frameworks like CodeIgniter that were built long before modern PHP components existed. The modern PHP ecosystem is a veritable melting pot of code that helps us developers build amazing applications.

Unfortunately, older PHP frameworks were developed in isolation and do not share code with other PHP frameworks. If your project uses one of these older PHP frameworks, you’re stuck with the framework and must live inside the framework’s ecosystem. This centralized environment is OK if you are happy with the framework’s tools. However, what if you use the CodeIgniter framework but want to cherry-pick a helper library from the Symfony framework? You’re probably out of luck unless you write a one-off adapter specifically for your project.

What we’ve got here is a failure to communicate.

Cool Hand Luke

Do you see the problem? Frameworks created in isolation were not designed to communicate with other frameworks. This is extremely inefficient, both for developers (creativity is limited by framework choice) and for frameworks themselves (they re-invent code that already exists elsewhere). I have good news, though. The PHP community has evolved from a centralized framework model to a distributed ecosystem of efficient, interoperable, and specialized components.

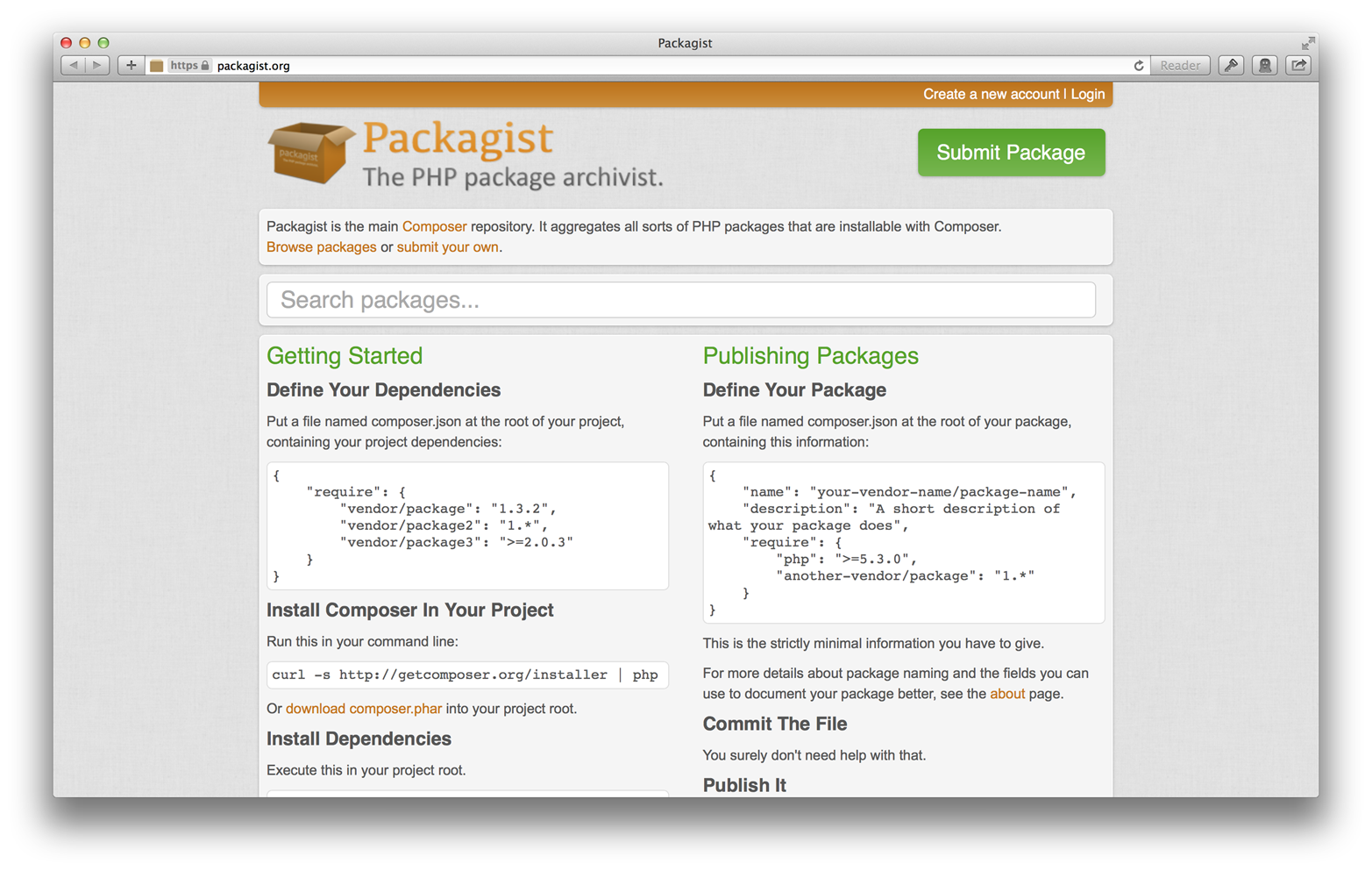

Several PHP framework developers recognized this problem and began a

conversation at php|tek (a popular PHP conference) in 2009. They

discussed how to improve intraframework communication and efficiency.

Instead of writing a new and tightly coupled logging class, for example,

what if a PHP framework could share a decoupled logging class like

monolog? Instead of writing its own HTTP request and response classes,

what if a PHP framework could instead cherry-pick the excellent HTTP request

and response classes from the Symfony Framework’s symfony/httpfoundation

component? For this to work, PHP frameworks must speak a common language that allows them to

communicate and share with other frameworks. They need standards.

The PHP framework developers who serendipitously met at php|tek eventually created the PHP Framework Interop Group (PHP-FIG). The PHP-FIG is a group of PHP framework representatives who, according to the PHP-FIG website, “talk about the commonalities between our projects and find ways we can work together.” The PHP-FIG creates recommendations that PHP frameworks can voluntarily implement to improve communication and sharing with other frameworks.

The PHP-FIG is a self-appointed group of framework representatives. Its members are not elected, and they are not special in any way other than their willingness to improve the PHP community. Anyone can request membership. And anyone can submit feedback to PHP-FIG recommendations that are in the proposal process. Final PHP-FIG recommendations are typically adopted and implemented by many of the largest and most popular PHP frameworks. I highly encourage you to get involved with the PHP-FIG, if only to send feedback and help shape the future of your favorite PHP frameworks.

The PHP-FIG’s mission is framework interoperability. And framework interoperability means working together via interfaces, autoloading, and style.

PHP frameworks work together via shared interfaces. PHP interfaces allow frameworks to assume what methods are provided by third-party dependencies without worrying about how the dependencies implement the interface.

Refer to Chapter 2 for an in-depth explanation of PHP interfaces.

For example, a framework is happy to share a third-party logger object

assuming the shared logger object implements the

emergency(), alert(), critical(), error(), warning(),

notice(), info(), and debug() methods. Exactly how these methods

are implemented is irrelevant. Each framework cares only that the third-party

dependency does implement these methods.

Interfaces enable PHP developers to build, share, and use specialized components instead of monolithic frameworks.

PHP frameworks work together via autoloading. Autoloading is the process by which a PHP class is automatically located and loaded on-demand by the PHP interpreter during runtime.

Before PHP standards, PHP components and frameworks implemented their

own unique autoloaders using the magic \__autoload() method or the more

recent spl_autoload_register() method. This required us to

learn and use a unique autoloader for each component and framework.

Nowadays, most modern PHP components and frameworks are compatible with

a common autoloader standard. This means we can mix and match multiple

PHP components with only one autoloader.

PHP frameworks work together via code style. Your code style determines spacing, capitalization, and bracket placement (among other things). If PHP frameworks agree on a standard code style, PHP developers don’t need to learn a new style every time they use a new PHP framework. Instead, PHP framework code is immediately familiar. A standard code style also lowers the barrier for new project contributors, who can spend more time squashing bugs and less time learning an unfamiliar style.

Standard code style also improves our own projects. Every developer has a unique style with more than a few idiosyncrasies, and these become a problem when multiple developers work on the same codebase. A standard code style helps all team members immediately understand the same codebase regardless of its author.

PSR is an acronym for PHP standards recommendation. If you’ve recently read a PHP-related blog, you have probably seen the terms PSR-1, PSR-2, PSR-3, and so on. These are PHP-FIG recommendations. Their names begin with PSR- and end with a number. Each PHP-FIG recommendation solves a specific problem that is frequently encountered by most PHP frameworks. Instead of PHP frameworks continually re-solving the same problems, frameworks can instead adopt the PHP-FIG’s recommendations and build upon shared solutions.

The PHP-FIG has published five recommendations as of this book’s publication:

If you counted only four recommendations, you are correct. The PHP-FIG deprecated its first PSR-0 recommendation. This first recommendation was replaced by the newer PSR-4 recommendation.

Notice how the PHP-FIG recommendations coincide nicely with the three interoperability methods I mentioned earlier: interfaces, autoloading, and code style. This is not a coincidence.

I’m really excited about the PHP-FIG recommendations. They are the bedrock beneath the modern PHP ecosystem. They define the means with which PHP components and frameworks interoperate. I admit, PHP standards are not the most scintillating of topics, but they are (in my mind) prerequisite to understanding modern PHP.

If you want to write PHP code that is compatible with community standards, start with PSR-1. It’s the easiest PHP standard to use. It’s so easy, you’re probably already using it without even trying. PSR-1 provides simple guidelines that are easy to implement with minimal effort. The point of PSR-1 is to provide a baseline code style for participating PHP frameworks. You must satisfy these requirements to be compatible with PSR-1:

You must surround your PHP code with either the <?php ?>

or <?= ?> tags. You must not use any other PHP tag syntax.

All PHP files must be encoded with the UTF-8 character set without a byte order mark (BOM). This sounds complicated, but your text editor or IDE can do this for you automatically.

A single PHP file can either define symbols (a class, trait, function, constant, etc.) or perform an action that has side effects (e.g., create output or manipulate data). A PHP file should not do both. This is a simple task and requires only a little foresight and planning on your part.

Your PHP namespaces and classes must support the PSR-4 autoloader standard. All you have to do is choose appropriate names for your PHP symbols and make sure their definition files are in the expected location. We’ll chat about PSR-4 soon.

Your PHP class names must use the common CamelCase

format. This format is also called TitleCase. Examples are

CoffeeGrinder, CoffeeBean, and PourOver.

Your PHP constants must use all uppercase characters.

They may use underscores to separate words if necessary. Examples are

WOOT, LET_OUR_POWERS_COMBINE, and GREAT_SCOTT.

Your PHP method names must use the common camelCase

format. This means the method name’s first character is lowercase, and

the first letter of each subsequent word in the method name is

uppercase. Examples are phpIsAwesome, iLoveBacon, and

tennantIsMyFavoriteDoctor.

After you implement PSR-1, the next step is to implement PSR-2. The PSR-2 standard further defines PHP code style with stricter guidelines.

The PSR-2 code style is a godsend for PHP frameworks that have many contributors from around the world, all of whom bring their own unique style and preferences. A common strict code style lets developers write code that is easily and quickly understood by other contributors.

Unlike PSR-1, the PSR-2 recommendation contains stricter guidelines. Some of PSR-2’s guidelines may not be what you prefer. However, PSR-2 is the preferred code style of many popular PHP frameworks. You don’t have to use PSR-2, but doing so will drastically improve the ability for other developers to read, use, and contribute to your PHP code.

You should use the stricter PSR-2 code style. Even though I call it strict, it’s easy enough to write. Eventually it’ll become second nature. Also, there are tools available to automatically format existing PHP code into the PSR-2 style.

The PSR-2 code style requires that you implement the PSR-1 code style.

This is a hot topic that is typically divided into two camps. The first camp prefers to indent code with a single tab character. The second (and much cooler) camp prefers to indent code with several space characters. The PSR-2 recommendation says PHP code should be indented with four space characters.

From personal experience, space characters are better suited for indentation because a space is a definitive measure that largely renders the same in different code editors. A tab, however, can vary in width and renders differently in different code editors. Use four space characters to indent code to ensure the best visual continuity for your code.

Your PHP files must use Unix linefeed (LF) endings, must end with a

single blank line, and must not include a trailing ?> PHP tag. Each line

of code should not exceed 80 characters. Ultimately, each line of code

must not exceed 120 characters. Each line must not have trailing white space.

This sounds like a lot of work, but it’s really not. Most code editors can

automatically wrap code to a specific width, strip trailing whitespace,

and use Unix line endings. All of these should happen automatically with

little to no thought on your part.

Omitting the trailing ?> PHP tag was odd to me at first.

However, it is good practice to omit the closing tag to avoid

unexpected output errors. If you do include the ?> closing tag, and also a