Chapter 5. Model Evaluation and Improvement

Having discussed the fundamentals of supervised and unsupervised learning, and having explored a variety of machine learning algorithms, we will now dive more deeply into evaluating models and selecting parameters.

We will focus on the supervised methods, regression and classification, as evaluating and selecting models in unsupervised learning is often a very qualitative process (as we saw in Chapter 3).

To evaluate our supervised models, so far we have split our dataset into

a training set and a test set using the train_test_split function,

built a model on the training set by calling the fit method, and

evaluated it on the test set using the score method, which for

classification computes the fraction of correctly classified samples.

Here’s an example of that process:

In[1]:

fromsklearn.datasetsimportmake_blobsfromsklearn.linear_modelimportLogisticRegressionfromsklearn.model_selectionimporttrain_test_split# create a synthetic datasetX,y=make_blobs(random_state=0)# split data and labels into a training and a test setX_train,X_test,y_train,y_test=train_test_split(X,y,random_state=0)# instantiate a model and fit it to the training setlogreg=LogisticRegression().fit(X_train,y_train)# evaluate the model on the test set("Test set score: {:.2f}".format(logreg.score(X_test,y_test)))

Out[1]:

Test set score: 0.88

Remember, the reason we split our data into training and test sets is that we are interested in measuring how well our model generalizes to new, previously unseen data. We are not interested in how well our model fit the training set, but rather in how well it can make predictions for data that was not observed during training.

In this chapter, we will expand on two aspects of this evaluation. We

will first introduce cross-validation, a more robust way to assess

generalization performance, and discuss methods to evaluate

classification and regression performance that go beyond the default

measures of accuracy and R2 provided by the score

method.

We will also discuss grid search, an effective method for adjusting the parameters in supervised models for the best generalization performance.

5.1 Cross-Validation

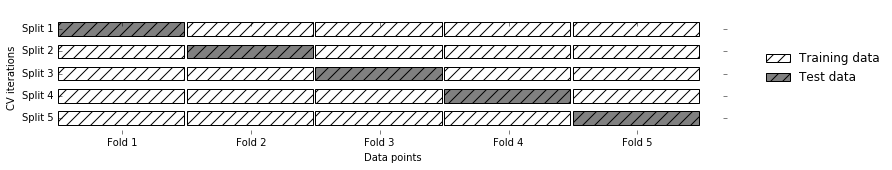

Cross-validation is a statistical method of evaluating generalization performance that is more stable and thorough than using a split into a training and a test set. In cross-validation, the data is instead split repeatedly and multiple models are trained. The most commonly used version of cross-validation is k-fold cross-validation, where k is a user-specified number, usually 5 or 10. When performing five-fold cross-validation, the data is first partitioned into five parts of (approximately) equal size, called folds. Next, a sequence of models is trained. The first model is trained using the first fold as the test set, and the remaining folds (2–5) are used as the training set. The model is built using the data in folds 2–5, and then the accuracy is evaluated on fold 1. Then another model is built, this time using fold 2 as the test set and the data in folds 1, 3, 4, and 5 as the training set. This process is repeated using folds 3, 4, and 5 as test sets. For each of these five splits of the data into training and test sets, we compute the accuracy. In the end, we have collected five accuracy values. The process is illustrated in Figure 5-1:

In[2]:

mglearn.plots.plot_cross_validation()

Figure 5-1. Data splitting in five-fold cross-validation

Usually, the first fifth of the data is the first fold, the second fifth of the data is the second fold, and so on.

5.1.1 Cross-Validation in scikit-learn

Cross-validation is implemented in scikit-learn using the

cross_val_score function from the model_selection module. The

parameters of the cross_val_score function are the model we want to

evaluate, the training data, and the ground-truth labels. Let’s evaluate

LogisticRegression on the iris dataset:

In[3]:

fromsklearn.model_selectionimportcross_val_scorefromsklearn.datasetsimportload_irisfromsklearn.linear_modelimportLogisticRegressioniris=load_iris()logreg=LogisticRegression()scores=cross_val_score(logreg,iris.data,iris.target)("Cross-validation scores: {}".format(scores))

Out[3]:

Cross-validation scores: [0.961 0.922 0.958]

Here, cross_val_score performed three-fold cross-validation and

therefore returned three scores. By default, cross_val_score performs

three-fold cross-validation in earlier versions of scikit-learn, and

will perform five-fold cross-validation by default (starting with

scikit-learn 0.22). We can change the number of folds used by changing

the cv parameter:

In[4]:

scores=cross_val_score(logreg,iris.data,iris.target,cv=5)("Cross-validation scores: {}".format(scores))

Out[4]:

Cross-validation scores: [1. 0.967 0.933 0.9 1. ]

It’s recommended to use at least five-fold cross-validation. A common way to summarize the cross-validation accuracy is to compute the mean:

In[5]:

("Average cross-validation score: {:.2f}".format(scores.mean()))

Out[5]:

Average cross-validation score: 0.96

Using the mean cross-validation we can conclude that we expect the model

to be around 96% accurate on average. Looking at all five scores

produced by the five-fold cross-validation, we can also conclude that

there is a relatively high variance in the accuracy between folds,

ranging from 100% accuracy to 90% accuracy. This could imply that the

model is very dependent on the particular folds used for training, but

it could also just be a consequence of the small size of the dataset.

There is a second function you can use for cross-validation, called

cross_validate. It has a similar interface to cross_val_score, but

returns a dictionary containing training and test times (and optionally

the training score, in addition to the test scores) for each split:

In[6]:

fromsklearn.model_selectionimportcross_validateres=cross_validate(logreg,iris.data,iris.target,cv=5,return_train_score=True)display(res)

Out[6]:

{'fit_time': array([0.002, 0.002, 0.002, 0.001, 0.002]),

'score_time': array([0. , 0. , 0.001, 0.001, 0.001]),

'test_score': array([1. , 0.967, 0.933, 0.9 , 1. ]),

'train_score': array([0.95 , 0.967, 0.967, 0.975, 0.958])}

Using pandas, we can nicely display these results and compute summaries:

In[7]:

res_df=pd.DataFrame(res)display(res_df)("Mean times and scores:\n",res_df.mean())

Out[7]:

[cols=",,,,",options="header",] |=============================================== | |fit_time |score_time |test_score |train_score |0 |1.50e-03 |4.62e-04 |1.00 |0.95 |1 |1.58e-03 |4.99e-04 |0.97 |0.97 |2 |1.60e-03 |6.45e-04 |0.93 |0.97 |3 |1.49e-03 |5.19e-04 |0.90 |0.97 |4 |1.54e-03 |1.06e-03 |1.00 |0.96 |=============================================== Mean times and scores: fit_time 1.54e-03 score_time 6.37e-04 test_score 9.60e-01 train_score 9.63e-01 dtype: float64

5.1.2 Benefits of Cross-Validation

There are several benefits to using cross-validation instead of a single

split into a training and a test set. First, remember that

train_test_split performs a random split of the data. Imagine that we

are “lucky” when randomly splitting the data, and all examples that are

hard to classify end up in the training set. In that case, the test set

will only contain “easy” examples, and our test set accuracy will be

unrealistically high. Conversely, if we are “unlucky,” we might have

randomly put all the hard-to-classify examples in the test set and

consequently obtain an unrealistically low score. However, when using

cross-validation, each example will be in the test set exactly once:

each example is in one of the folds, and each fold is the test set once.

Therefore, the model needs to generalize well to all of the samples in

the dataset for all of the cross-validation scores (and their mean) to

be high.

Having multiple splits of the data also provides some information about

how sensitive our model is to the selection of the training dataset.

For the iris dataset, we saw accuracies

between 90% and 100%. This is quite a range, and it provides us with an

idea about how the model might perform in the worst case and best

case scenarios when applied to new data.

Another benefit of cross-validation as compared to using a single split

of the data is that we use our data more effectively. When using

train_test_split, we usually use 75% of the data for training and 25%

of the data for evaluation. When using five-fold cross-validation, in

each iteration we can use four-fifths of the data (80%) to fit the model. When

using 10-fold cross-validation, we can use nine-tenths of the data (90%) to

fit the model. More data will usually result in more accurate models.

The main disadvantage of cross-validation is increased computational cost. As we are now training k models instead of a single model, cross-validation will be roughly k times slower than doing a single split of the data.

Tip

It is important to keep in mind that cross-validation is not

a way to build a model that can be applied to new data. Cross-validation

does not return a model. When calling cross_val_score, multiple models

are built internally, but the purpose of cross-validation is only to

evaluate how well a given algorithm will generalize when trained on a

specific dataset.

5.1.3 Stratified k-Fold Cross-Validation and Other Strategies

Splitting the dataset into k folds by starting with the first one-k-th

part of the data, as described in the previous section, might not always be a good idea. For

example, let’s have a look at the iris dataset:

In[8]:

fromsklearn.datasetsimportload_irisiris=load_iris()("Iris labels:\n{}".format(iris.target))

Out[8]:

Iris labels: [0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2]

As you can see, the first third of the data is the class 0, the second

third is the class 1, and the last third is the class 2. Imagine doing

three-fold cross-validation on this dataset. The first fold would be

only class 0, so in the first split of the data, the test set would be

only class 0, and the training set would be only classes 1 and 2. As

the classes in training and test sets would be different for all three

splits, the three-fold cross-validation accuracy would be zero on this

dataset. That is not very helpful, as we can do much better than 0%

accuracy on iris.

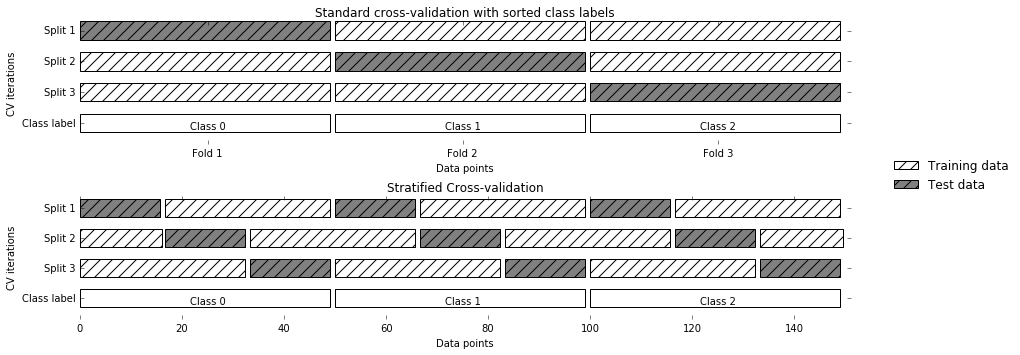

As the simple k-fold strategy fails here, scikit-learn does not use

it for classification, but rather uses stratified k-fold

cross-validation. In stratified cross-validation, we split the data

such that the proportions between classes are the same in each fold as

they are in the whole dataset, as illustrated in

Figure 5-2:

In[9]:

mglearn.plots.plot_stratified_cross_validation()

Figure 5-2. Comparison of standard cross-validation and stratified cross-validation when the data is ordered by class label

For example, if 90% of your samples belong to class A and 10% of your samples belong to class B, then stratified cross-validation ensures that in each fold, 90% of samples belong to class A and 10% of samples belong to class B.

It is usually a good idea to use stratified k-fold cross-validation instead of k-fold cross-validation to evaluate a classifier, because it results in more reliable estimates of generalization performance. In the case of only 10% of samples belonging to class B, using standard k-fold cross-validation it might easily happen that one fold only contains samples of class A. Using this fold as a test set would not be very informative about the overall performance of the classifier.

For regression, scikit-learn uses the standard k-fold cross-validation

by default. It would be possible to also try to make each fold

representative of the different values the regression target has, but

this is not a commonly used strategy and would be surprising to most

users.

More control over cross-validation

We saw earlier that we can adjust the number of folds that are used in

cross_val_score using the cv parameter. However, scikit-learn allows

for much finer control over what happens during the splitting of the

data by providing a cross-validation splitter as the cv parameter.

For most use cases, the defaults of k-fold cross-validation for

regression and stratified k-fold for classification work well, but there

are some cases where you might want to use a different strategy. Say, for

example, we want to use the standard k-fold cross-validation on a

classification dataset to reproduce someone else’s results. To do this,

we first have to import the KFold splitter class from the

model_selection module and instantiate it with the number of folds

we want to use:

In[10]:

fromsklearn.model_selectionimportKFoldkfold=KFold(n_splits=5)

Then, we can pass the kfold splitter object as the cv parameter to

cross_val_score:

In[11]:

("Cross-validation scores:\n{}".format(cross_val_score(logreg,iris.data,iris.target,cv=kfold)))

Out[11]:

Cross-validation scores: [1. 0.933 0.433 0.967 0.433]

This way, we can verify that it is indeed a really bad idea to use

three-fold (nonstratified) cross-validation on the iris dataset:

In[12]:

kfold=KFold(n_splits=3)("Cross-validation scores:\n{}".format(cross_val_score(logreg,iris.data,iris.target,cv=kfold)))

Out[12]:

Cross-validation scores: [0. 0. 0.]

Remember: each fold corresponds to one of the classes in the iris

dataset, and so nothing can be learned. Another way to resolve this

problem is to shuffle the data instead of stratifying the folds, to

remove the ordering of the samples by label. We can do that by setting the

shuffle parameter of KFold to True. If we shuffle the data, we

also need to fix the random_state to get a reproducible shuffling.

Otherwise, each run of cross_val_score would yield a different result,

as each time a different split would be used (this might not be a

problem, but can be surprising). Shuffling the data before splitting it yields a much better result:

In[13]:

kfold=KFold(n_splits=3,shuffle=True,random_state=0)("Cross-validation scores:\n{}".format(cross_val_score(logreg,iris.data,iris.target,cv=kfold)))

Out[13]:

Cross-validation scores: [0.9 0.96 0.96]

Leave-one-out cross-validation

Another frequently used cross-validation method is leave-one-out. You can think of leave-one-out cross-validation as k-fold cross-validation where each fold is a single sample. For each split, you pick a single data point to be the test set. This can be very time consuming, particularly for large datasets, but sometimes provides better estimates on small datasets:

In[14]:

fromsklearn.model_selectionimportLeaveOneOutloo=LeaveOneOut()scores=cross_val_score(logreg,iris.data,iris.target,cv=loo)("Number of cv iterations: ",len(scores))("Mean accuracy: {:.2f}".format(scores.mean()))

Out[14]:

Number of cv iterations: 150 Mean accuracy: 0.95

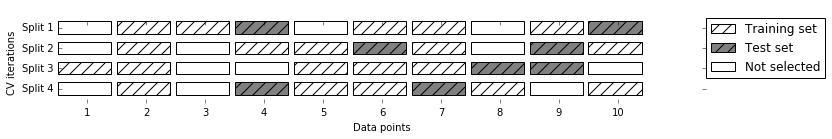

Shuffle-split cross-validation

Another, very flexible strategy for cross-validation is shuffle-split

cross-validation. In shuffle-split cross-validation, each split samples

train_size many points for the training set and test_size many

(disjoint) point for the test set. This splitting is repeated n_splits

times. Figure 5-3 illustrates running four iterations of

splitting a dataset consisting of 10 points, with a training set of 5

points and test sets of 2 points each (you can use integers for

train_size and test_size to use absolute sizes for these sets, or

floating-point numbers to use fractions of the whole dataset):

In[15]:

mglearn.plots.plot_shuffle_split()

Figure 5-3. ShuffleSplit with 10 points, train_size=5, test_size=2, and n_splits=4

The following code splits the dataset into 50% training set and 50% test set for 10 iterations:

In[16]:

fromsklearn.model_selectionimportShuffleSplitshuffle_split=ShuffleSplit(test_size=.5,train_size=.5,n_splits=10)scores=cross_val_score(logreg,iris.data,iris.target,cv=shuffle_split)("Cross-validation scores:\n{}".format(scores))

Out[16]:

Cross-validation scores: [0.973 0.92 0.96 0.96 0.893 0.947 0.88 0.893 0.947 0.947]

Shuffle-split cross-validation allows for control over the number of

iterations independently of the training and test sizes, which can

sometimes be helpful. It also allows for using only part of the data in

each iteration, by providing train_size and test_size settings that

don’t add up to one. Subsampling the data in this way can be useful for

experimenting with large datasets.

There is also a stratified variant of

ShuffleSplit, aptly named StratifiedShuffleSplit, which can provide

more reliable results for classification tasks.

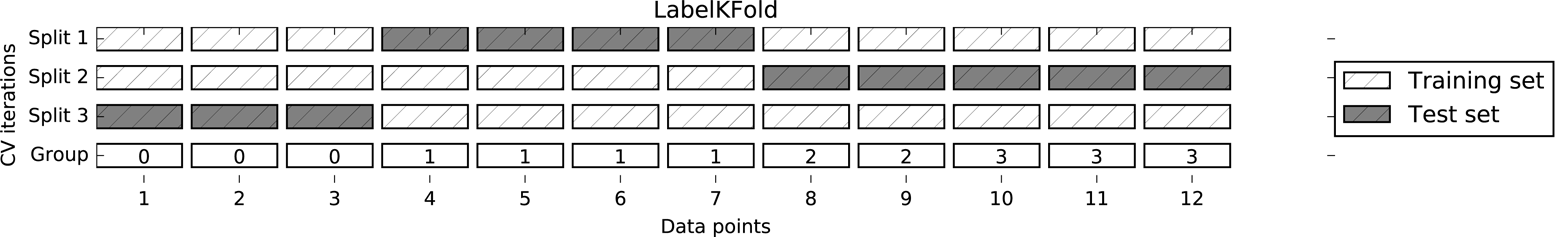

Cross-validation with groups

Another very common setting for cross-validation is when there are groups in the data that are highly related. Say you want to build a system to recognize emotions from pictures of faces, and you collect a dataset of pictures of 100 people where each person is captured multiple times, showing various emotions. The goal is to build a classifier that can correctly identify emotions of people not in the dataset. You could use the default stratified cross-validation to measure the performance of a classifier here. However, it is likely that pictures of the same person will be in both the training and the test set. It will be much easier for a classifier to detect emotions in a face that is part of the training set, compared to a completely new face. To accurately evaluate the generalization to new faces, we must therefore ensure that the training and test sets contain images of different people.

To achieve this, we can use GroupKFold, which takes an array of groups

as argument that we can use to indicate which person is in the image. The groups array here indicates groups in the data that should not be split when

creating the training and test sets, and should not be confused with the

class label.

This example of groups in the data is common in medical applications, where you might have multiple samples from the same patient, but are interested in generalizing to new patients. Similarly, in speech recognition, you might have multiple recordings of the same speaker in your dataset, but are interested in recognizing speech of new speakers.

The following is an example of using a synthetic dataset with a grouping given

by the groups array. The dataset consists of 12 data points, and for

each of the data points, groups specifies which group (think patient)

the point belongs to. The groups specify that there are four groups, and the

first three samples belong to the first group, the next four samples

belong to the second group, and so on:

In[17]:

fromsklearn.model_selectionimportGroupKFold# create synthetic datasetX,y=make_blobs(n_samples=12,random_state=0)# assume the first three samples belong to the same group,# then the next four, etc.groups=[0,0,0,1,1,1,1,2,2,3,3,3]scores=cross_val_score(logreg,X,y,groups,cv=GroupKFold(n_splits=3))("Cross-validation scores:\n{}".format(scores))

Out[17]:

Cross-validation scores: [0.75 0.8 0.667]

The samples don’t need to be ordered by group; we just did this for illustration purposes. The splits that are calculated based on these labels are visualized in Figure 5-4. As you can see, for each split, each group is either entirely in the training set or entirely in the test set:

In[18]:

mglearn.plots.plot_group_kfold()

Figure 5-4. Label-dependent splitting with GroupKFold

There are more splitting strategies for cross-validation in

scikit-learn, which allow for an even greater variety of use cases (you can find these in the scikit-learn user guide). However, the standard KFold,

StratifiedKFold, and GroupKFold are by far the most commonly used

ones.

5.2 Grid Search

Now that we know how to evaluate how well a model generalizes, we can

take the next step and improve the model’s generalization performance by

tuning its parameters. We discussed the parameter settings of many of

the algorithms in scikit-learn in Chapters 2 and 3, and it is important

to understand what the parameters mean before trying to adjust them.

Finding the values of the important parameters of a model (the ones that

provide the best generalization performance) is a tricky task, but

necessary for almost all models and datasets. Because it is such a

common task, there are standard methods in scikit-learn to help you with

it. The most commonly used method is grid search, which basically

means trying all possible combinations of the parameters of interest.

Consider the case of a kernel SVM with an RBF (radial basis function)

kernel, as implemented in the SVC class. As we discussed in Chapter 2,

there are two important parameters: the kernel bandwidth, gamma, and the

regularization parameter, C. Say we want to try the values

0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 for the parameter C, and the same for

gamma. Because we have six different settings for C and gamma that

we want to try, we have 36 combinations of parameters in total. Looking

at all possible combinations creates a table (or grid) of parameter

settings for the SVM, as shown here:

| C = 0.001 | C = 0.01 | … | C = 10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

gamma=0.001 |

SVC(C=0.001, gamma=0.001) |

SVC(C=0.01, gamma=0.001) |

… |

SVC(C=10, gamma=0.001) |

|

gamma=0.01 |

SVC(C=0.001, gamma=0.01) |

SVC(C=0.01, gamma=0.01) |

… |

SVC(C=10, gamma=0.01) |

|

… |

… |

… |

… |

… |

|

gamma=100 |

SVC(C=0.001, gamma=100) |

SVC(C=0.01, gamma=100) |

… |

SVC(C=10, gamma=100) |

5.2.1 Simple Grid Search

We can implement a simple grid search just as for loops over the two

parameters, training and evaluating a classifier for each combination:

In[19]:

# naive grid search implementationfromsklearn.svmimportSVCX_train,X_test,y_train,y_test=train_test_split(iris.data,iris.target,random_state=0)("Size of training set: {} size of test set: {}".format(X_train.shape[0],X_test.shape[0]))best_score=0forgammain[0.001,0.01,0.1,1,10,100]:forCin[0.001,0.01,0.1,1,10,100]:# for each combination of parameters, train an SVCsvm=SVC(gamma=gamma,C=C)svm.fit(X_train,y_train)# evaluate the SVC on the test setscore=svm.score(X_test,y_test)# if we got a better score, store the score and parametersifscore>best_score:best_score=scorebest_parameters={'C':C,'gamma':gamma}("Best score: {:.2f}".format(best_score))("Best parameters: {}".format(best_parameters))

Out[19]:

Size of training set: 112 size of test set: 38

Best score: 0.97

Best parameters: {'C': 100, 'gamma': 0.001}

5.2.2 The Danger of Overfitting the Parameters and the Validation Set

Given this result, we might be tempted to report that we found a model that performs with 97% accuracy on our dataset. However, this claim could be overly optimistic (or just wrong), for the following reason: we tried many different parameters and selected the one with best accuracy on the test set, but this accuracy won’t necessarily carry over to new data. Because we used the test data to adjust the parameters, we can no longer use it to assess how good the model is. This is the same reason we needed to split the data into training and test sets in the first place; we need an independent dataset to evaluate, one that was not used to create the model.

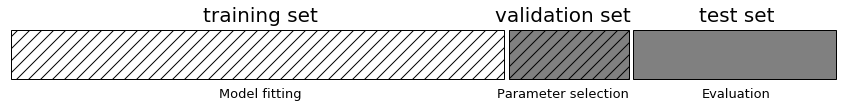

One way to resolve this problem is to split the data again, so we have three sets: the training set to build the model, the validation (or development) set to select the parameters of the model, and the test set to evaluate the performance of the selected parameters. Figure 5-5 shows what this looks like:

In[20]:

mglearn.plots.plot_threefold_split()

Figure 5-5. A threefold split of data into training set, validation set, and test set

After selecting the best parameters using the validation set, we can rebuild a model using the parameter settings we found, but now training on both the training data and the validation data. This way, we can use as much data as possible to build our model. This leads to the following implementation:

In[21]:

fromsklearn.svmimportSVC# split data into train+validation set and test setX_trainval,X_test,y_trainval,y_test=train_test_split(iris.data,iris.target,random_state=0)# split train+validation set into training and validation setsX_train,X_valid,y_train,y_valid=train_test_split(X_trainval,y_trainval,random_state=1)("Size of training set: {} size of validation set: {} size of test set:"" {}\n".format(X_train.shape[0],X_valid.shape[0],X_test.shape[0]))best_score=0forgammain[0.001,0.01,0.1,1,10,100]:forCin[0.001,0.01,0.1,1,10,100]:# for each combination of parameters, train an SVCsvm=SVC(gamma=gamma,C=C)svm.fit(X_train,y_train)# evaluate the SVC on the validation setscore=svm.score(X_valid,y_valid)# if we got a better score, store the score and parametersifscore>best_score:best_score=scorebest_parameters={'C':C,'gamma':gamma}# rebuild a model on the combined training and validation set,# and evaluate it on the test setsvm=SVC(**best_parameters)svm.fit(X_trainval,y_trainval)test_score=svm.score(X_test,y_test)("Best score on validation set: {:.2f}".format(best_score))("Best parameters: ",best_parameters)("Test set score with best parameters: {:.2f}".format(test_score))

Out[21]:

Size of training set: 84 size of validation set: 28 size of test set: 38

Best score on validation set: 0.96

Best parameters: {'C': 10, 'gamma': 0.001}

Test set score with best parameters: 0.92

The best score on the validation set is 96%: slightly lower than

before, probably because we used less data to train the model (X_train

is smaller now because we split our dataset twice). However, the score

on the test set—the score that actually tells us how well we

generalize—is even lower, at 92%. So we can only claim to classify new

data 92% correctly, not 97% correctly as we thought before!

The distinction between the training set, validation set, and test set is fundamentally important to applying machine learning methods in practice. Any choices made based on the test set accuracy “leak” information from the test set into the model. Therefore, it is important to keep a separate test set, which is only used for the final evaluation. It is good practice to do all exploratory analysis and model selection using the combination of a training and a validation set, and reserve the test set for a final evaluation—this is even true for exploratory visualization. Strictly speaking, evaluating more than one model on the test set and choosing the better of the two will result in an overly optimistic estimate of how accurate the model is.

5.2.3 Grid Search with Cross-Validation

While the method of splitting the data into a training, a

validation, and a test set that we just saw is workable, and relatively commonly used, it

is quite sensitive to how exactly the data is split. From the output of

the previous code snippet we can see that grid search

selects 'C': 10, 'gamma': 0.001 as the best parameters, while the

output of the code in the previous section selects

'C': 100, 'gamma': 0.001 as the best parameters. For a better estimate

of the generalization performance, instead of using a single split into

a training and a validation set, we can use cross-validation to evaluate

the performance of each parameter combination. This method can be coded

up as follows:

In[22]:

forgammain[0.001,0.01,0.1,1,10,100]:forCin[0.001,0.01,0.1,1,10,100]:# for each combination of parameters,# train an SVCsvm=SVC(gamma=gamma,C=C)# perform cross-validationscores=cross_val_score(svm,X_trainval,y_trainval,cv=5)# compute mean cross-validation accuracyscore=np.mean(scores)# if we got a better score, store the score and parametersifscore>best_score:best_score=scorebest_parameters={'C':C,'gamma':gamma}# rebuild a model on the combined training and validation setsvm=SVC(**best_parameters)svm.fit(X_trainval,y_trainval)

To evaluate the accuracy of the SVM using a particular setting of C

and gamma using five-fold cross-validation, we need to train 36 * 5 =

180 models. As you can imagine, the main downside of the use of

cross-validation is the time it takes to train all these models.

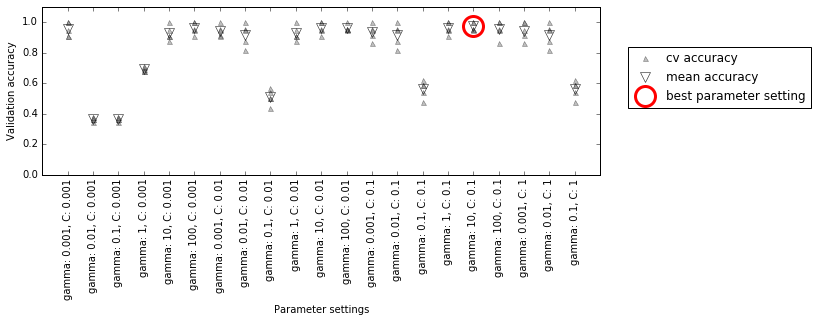

The following visualization (Figure 5-6) illustrates how the best parameter setting is selected in the preceding code:

In[23]:

mglearn.plots.plot_cross_val_selection()

Figure 5-6. Results of grid search with cross-validation

For each parameter setting (only a subset is shown), five accuracy values are computed, one for each split in the cross-validation. Then the mean validation accuracy is computed for each parameter setting. The parameters with the highest mean validation accuracy are chosen, marked by the circle.

Warning

As we said earlier, cross-validation is a way to evaluate a given algorithm on a specific dataset. However, it is often used in conjunction with parameter search methods like grid search. For this reason, many people use the term cross-validation colloquially to refer to grid search with cross-validation.

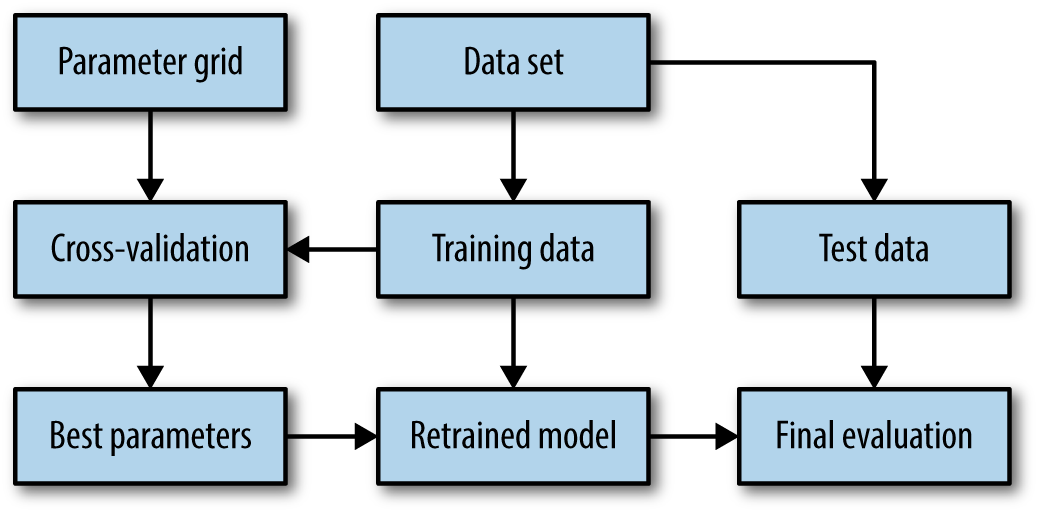

The overall process of splitting the data, running the grid search, and evaluating the final parameters is illustrated in Figure 5-7:

In[24]:

mglearn.plots.plot_grid_search_overview()

Figure 5-7. Overview of the process of parameter selection and model evaluation with GridSearchCV

Because grid search with cross-validation is such a commonly used method

to adjust parameters, scikit-learn provides the GridSearchCV class, which

implements it in the form of an estimator. To use the GridSearchCV

class, you first need to specify the parameters you want to search over

using a dictionary. GridSearchCV will then perform all the necessary

model fits. The keys of the dictionary are the names of parameters we

want to adjust (as given when constructing the model—in this case, C

and gamma), and the values are the parameter settings we want to try

out. Trying the values 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 for C and

gamma translates to the following dictionary:

In[25]:

param_grid={'C':[0.001,0.01,0.1,1,10,100],'gamma':[0.001,0.01,0.1,1,10,100]}("Parameter grid:\n{}".format(param_grid))

Out[25]:

Parameter grid:

{'C': [0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100], 'gamma': [0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100]}

We can now instantiate the GridSearchCV class with the model (SVC),

the parameter grid to search (param_grid), and the cross-validation

strategy we want to use (say, five-fold stratified cross-validation):

In[26]:

fromsklearn.model_selectionimportGridSearchCVfromsklearn.svmimportSVCgrid_search=GridSearchCV(SVC(),param_grid,cv=5,return_train_score=True)

GridSearchCV will use cross-validation in place of the split into a

training and validation set that we used before. However, we still need

to split the data into a training and a test set, to avoid overfitting

the parameters:

In[27]:

X_train,X_test,y_train,y_test=train_test_split(iris.data,iris.target,random_state=0)

The grid_search object that we created behaves just like a classifier;

we can call the standard methods fit, predict, and score on it.1 However,

when we call fit, it will run cross-validation for each combination of

parameters we specified in param_grid:

In[28]:

grid_search.fit(X_train,y_train)

Fitting the GridSearchCV object not only searches for the best

parameters, but also automatically fits a new model on the whole training

dataset with the parameters that yielded the best cross-validation

performance. What happens in fit is therefore equivalent to the result of the In[21] code we saw at the beginning of this section. The GridSearchCV class provides a

very convenient interface to access the retrained model using the

predict and score methods. To evaluate how well the best found

parameters generalize, we can call score on the test set:

In[29]:

("Test set score: {:.2f}".format(grid_search.score(X_test,y_test)))

Out[29]:

Test set score: 0.97

Choosing the parameters using cross-validation, we actually found a

model that achieves 97% accuracy on the test set. The important thing

here is that we did not use the test set to choose the parameters. The

parameters that were found are stored in the best_params_ attribute,

and the best cross-validation accuracy (the mean accuracy over the

different splits for this parameter setting) is stored in best_score_:

In[30]:

("Best parameters: {}".format(grid_search.best_params_))("Best cross-validation score: {:.2f}".format(grid_search.best_score_))

Out[30]:

Best parameters: {'C': 100, 'gamma': 0.01}

Best cross-validation score: 0.97

Warning

Again, be careful not to confuse best_score_ with the

generalization performance of the model as computed by the score

method on the test set. Using the score method (or evaluating the

output of the predict method) employs a model trained on the whole

training set. The best_score_ attribute stores the mean cross-validation accuracy, with cross-validation performed on the

training set.

Sometimes it is helpful to have access to the actual model that was

found—for example, to look at coefficients or feature importances. You

can access the model with the best parameters trained on the whole

training set using the best_estimator_ attribute:

In[31]:

("Best estimator:\n{}".format(grid_search.best_estimator_))

Out[31]:

Best estimator: SVC(C=100, cache_size=200, class_weight=None, coef0=0.0, decision_function_shape='ovr', degree=3, gamma=0.01, kernel='rbf', max_iter=-1, probability=False, random_state=None, shrinking=True, tol=0.001, verbose=False)

Because grid_search itself has predict and score methods, using

best_estimator_ is not needed to make predictions or evaluate the

model.

Analyzing the result of cross-validation

It is often helpful to visualize the results of cross-validation, to

understand how the model generalization depends on the parameters we are

searching. As grid searches are quite computationally expensive to run,

often it is a good idea to start with a relatively coarse and small

grid. We can then inspect the results of the cross-validated

grid search, and possibly expand our search. The results of a grid

search can be found in the cv_results_ attribute, which is a dictionary

storing all aspects of the search. It contains a lot of details, as you can see in the following output, and

is best looked at after converting it to a pandas DataFrame:

In[32]:

importpandasaspd# convert to DataFrameresults=pd.DataFrame(grid_search.cv_results_)# show the first 5 rowsdisplay(results.head())

Out[32]:

param_C param_gamma params mean_test_score

0 0.001 0.001 {'C': 0.001, 'gamma': 0.001} 0.366

1 0.001 0.01 {'C': 0.001, 'gamma': 0.01} 0.366

2 0.001 0.1 {'C': 0.001, 'gamma': 0.1} 0.366

3 0.001 1 {'C': 0.001, 'gamma': 1} 0.366

4 0.001 10 {'C': 0.001, 'gamma': 10} 0.366

rank_test_score split0_test_score split1_test_score split2_test_score

0 22 0.375 0.347 0.363

1 22 0.375 0.347 0.363

2 22 0.375 0.347 0.363

3 22 0.375 0.347 0.363

4 22 0.375 0.347 0.363

split3_test_score split4_test_score std_test_score

0 0.363 0.380 0.011

1 0.363 0.380 0.011

2 0.363 0.380 0.011

3 0.363 0.380 0.011

4 0.363 0.380 0.011

Each row in results corresponds to one particular parameter

setting. For each setting, the results of all cross-validation splits

are recorded, as well as the mean and standard deviation over all splits. As

we were searching a two-dimensional grid of parameters (C and

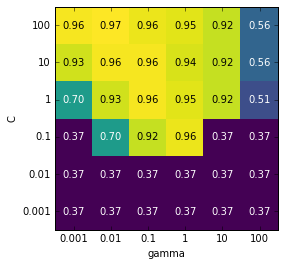

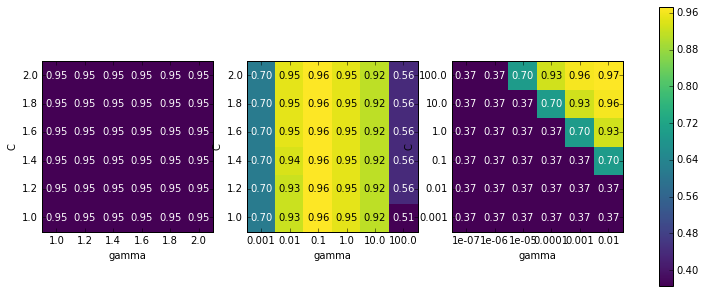

gamma), this is best visualized as a heat map (Figure 5-8). First we extract the

mean validation scores, then we reshape the scores so that the axes

correspond to C and gamma:

In[33]:

scores=np.array(results.mean_test_score).reshape(6,6)# plot the mean cross-validation scoresmglearn.tools.heatmap(scores,xlabel='gamma',xticklabels=param_grid['gamma'],ylabel='C',yticklabels=param_grid['C'],cmap="viridis")

Figure 5-8. Heat map of mean cross-validation score as a function of C and gamma

Each point in the heat map corresponds to one run of cross-validation,

with a particular parameter setting. The color encodes the

cross-validation accuracy, with light colors meaning high accuracy and

dark colors meaning low accuracy. You can see that SVC is very

sensitive to the setting of the parameters. For many of the parameter

settings, the accuracy is around 40%, which is quite bad; for other

settings the accuracy is around 96%. We can take away from this plot

several things. First, the parameters we adjusted are very important

for obtaining good performance. Both parameters (C and gamma) matter a

lot, as adjusting them can change the accuracy from 40% to 96%. Additionally,

the ranges we picked for the parameters are ranges in which we see

significant changes in the outcome. It’s also important to note that the

ranges for the parameters are large enough: the optimum values for each

parameter are not on the edges of the plot.

Now let’s look at some plots (shown in Figure 5-9) where the result is less ideal, because the search ranges were not chosen properly:

Figure 5-9. Heat map visualizations of misspecified search grids

In[34]:

fig,axes=plt.subplots(1,3,figsize=(13,5))param_grid_linear={'C':np.linspace(1,2,6),'gamma':np.linspace(1,2,6)}param_grid_one_log={'C':np.linspace(1,2,6),'gamma':np.logspace(-3,2,6)}param_grid_range={'C':np.logspace(-3,2,6),'gamma':np.logspace(-7,-2,6)}forparam_grid,axinzip([param_grid_linear,param_grid_one_log,param_grid_range],axes):grid_search=GridSearchCV(SVC(),param_grid,cv=5)grid_search.fit(X_train,y_train)scores=grid_search.cv_results_['mean_test_score'].reshape(6,6)# plot the mean cross-validation scoresscores_image=mglearn.tools.heatmap(scores,xlabel='gamma',ylabel='C',xticklabels=param_grid['gamma'],yticklabels=param_grid['C'],cmap="viridis",ax=ax)plt.colorbar(scores_image,ax=axes.tolist())

The first panel shows no changes at all, with a constant color over the

whole parameter grid. In this case, this is caused by improper scaling

and range of the parameters C and gamma. However, if no change in

accuracy is visible over the different parameter settings, it could also

be that a parameter is just not important at all. It is usually good to

try very extreme values first, to see if there are any changes in the

accuracy as a result of changing a parameter.

The second panel shows a vertical stripe pattern. This indicates that

only the setting of the gamma parameter makes any difference. This could

mean that the gamma parameter is searching over interesting values but

the C parameter is not—or it could mean the C parameter is not

important.

The third panel shows changes in both C and gamma. However, we can

see that in the entire bottom left of the plot, nothing interesting is

happening. We can probably exclude the very small values from future

grid searches. The optimum parameter setting is at the top right. As the

optimum is in the border of the plot, we can expect that there might be

even better values beyond this border, and we might want to change our

search range to include more parameters in this region.

Tuning the parameter grid based on the cross-validation scores is perfectly fine, and a good way to explore the importance of different parameters. However, you should not test different parameter ranges on the final test set—as we discussed earlier, evaluation of the test set should happen only once we know exactly what model we want to use.

Search over spaces that are not grids

In some cases, trying all possible combinations of all parameters

as GridSearchCV usually does, is not a good idea. For example, SVC

has a kernel parameter, and depending on which kernel is chosen, other parameters will be relevant. If kernel='linear', the model

is linear, and only the C parameter is used. If kernel='rbf', both

the C and gamma parameters are used (but not other parameters like

degree). In this case, searching over all possible combinations of

C, gamma, and kernel wouldn’t make sense: if kernel='linear',

gamma is not used, and trying different values for gamma would be a

waste of time. To deal with these kinds of “conditional” parameters,

GridSearchCV allows the param_grid to be a list of dictionaries.

Each dictionary in the list is expanded into an independent grid. A

possible grid search involving kernel and parameters could look like

this:

In[35]:

param_grid=[{'kernel':['rbf'],'C':[0.001,0.01,0.1,1,10,100],'gamma':[0.001,0.01,0.1,1,10,100]},{'kernel':['linear'],'C':[0.001,0.01,0.1,1,10,100]}]("List of grids:\n{}".format(param_grid))

Out[35]:

List of grids:

[{'kernel': ['rbf'], 'C': [0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100],

'gamma': [0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100]},

{'kernel': ['linear'], 'C': [0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100]}]

In the first grid, the kernel parameter is always set to 'rbf' (note

that the entry for kernel is a list of length one), and both the C

and gamma parameters are varied. In the second grid, the kernel

parameter is always set to linear, and only C is varied. Now let’s

apply this more complex parameter search:

In[36]:

grid_search=GridSearchCV(SVC(),param_grid,cv=5,return_train_score=True)grid_search.fit(X_train,y_train)("Best parameters: {}".format(grid_search.best_params_))("Best cross-validation score: {:.2f}".format(grid_search.best_score_))

Out[36]:

Best parameters: {'C': 100, 'gamma': 0.01, 'kernel': 'rbf'}

Best cross-validation score: 0.97

Let’s look at the cv_results_ again. As expected, if kernel is

'linear', then only C is varied:

In[37]:

results=pd.DataFrame(grid_search.cv_results_)# we display the transposed table so that it better fits on the page:display(results.T)

Out[37]:

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | … | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

param_C |

0.001 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

… |

0.1 |

1 |

10 |

100 |

param_gamma |

0.001 |

0.01 |

0.1 |

1 |

… |

NaN |

NaN |

NaN |

NaN |

param_kernel |

rbf |

rbf |

rbf |

rbf |

… |

linear |

linear |

linear |

linear |

params |

{C: 0.001, kernel: rbf, gamma: 0.001} |

{C: 0.001, kernel: rbf, gamma: 0.01} |

{C: 0.001, kernel: rbf, gamma: 0.1} |

{C: 0.001, kernel: rbf, gamma: 1} |

… |

{C: 0.1, kernel: linear} |

{C: 1, kernel: linear} |

{C: 10, kernel: linear} |

{C: 100, kernel: linear} |

mean_test_score |

0.37 |

0.37 |

0.37 |

0.37 |

… |

0.95 |

0.97 |

0.96 |

0.96 |

rank_test_score |

27 |

27 |

27 |

27 |

… |

11 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

split0_test_score |

0.38 |

0.38 |

0.38 |

0.38 |

… |

0.96 |

1 |

0.96 |

0.96 |

split1_test_score |

0.35 |

0.35 |

0.35 |

0.35 |

… |

0.91 |

0.96 |

1 |

1 |

split2_test_score |

0.36 |

0.36 |

0.36 |

0.36 |

… |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

split3_test_score |

0.36 |

0.36 |

0.36 |

0.36 |

… |

0.91 |

0.95 |

0.91 |

0.91 |

split4_test_score |

0.38 |

0.38 |

0.38 |

0.38 |

… |

0.95 |

0.95 |

0.95 |

0.95 |

std_test_score |

0.011 |

0.011 |

0.011 |

0.011 |

… |

0.033 |

0.022 |

0.034 |

0.034 |

12 rows × 42 columns

Using different cross-validation strategies with grid search

Similarly to cross_val_score, GridSearchCV uses stratified k-fold

cross-validation by default for classification, and k-fold

cross-validation for regression. However, you can also pass any

cross-validation splitter, as described in “More control over cross-validation”, as the cv

parameter in GridSearchCV. In particular, to get only a single split

into a training and a validation set, you can use ShuffleSplit or

StratifiedShuffleSplit with n_splits=1. This might be helpful for very

large datasets, or very slow models.

Nested cross-validation

In the preceding examples, we went from using a single split of the data into

training, validation, and test sets to splitting the data into training

and test sets and then performing cross-validation on the training set.

But when using GridSearchCV as described earlier, we still have a single split of the

data into training and test sets, which might make our

results unstable and make us depend too much on this single split

of the data. We can go a step further, and instead of splitting the

original data into training and test sets once, use multiple

splits of cross-validation. This will result in what is called nested

cross-validation. In nested cross-validation, there is an outer loop

over splits of the data into training and test sets. For each of them, a

grid search is run (which might result in different best parameters for

each split in the outer loop). Then, for each outer split, the test set

score using the best settings is reported.

The result of this procedure is a list of scores—not a model, and not a parameter setting. The scores tell us how well a model generalizes, given the best parameters found by grid search. As it doesn’t provide a model that can be used on new data, nested cross-validation is rarely used when looking for a predictive model to apply to future data. However, it can be useful for evaluating how well a given model works on a particular dataset.

Implementing nested cross-validation in scikit-learn is straightforward.

We call cross_val_score with an instance of GridSearchCV as the

model:

In[38]:

param_grid={'C':[0.001,0.01,0.1,1,10,100],'gamma':[0.001,0.01,0.1,1,10,100]}scores=cross_val_score(GridSearchCV(SVC(),param_grid,cv=5),iris.data,iris.target,cv=5)("Cross-validation scores: ",scores)("Mean cross-validation score: ",scores.mean())

Out[38]:

Cross-validation scores: [0.967 1. 0.967 0.967 1. ] Mean cross-validation score: 0.98

The result of our nested cross-validation can be summarized as “SVC can

achieve 98% mean cross-validation accuracy on the iris dataset”—nothing more and nothing less.

Here, we used stratified five-fold cross-validation in both the inner

and the outer loop. As our param_grid contains 36 combinations of

parameters, this results in a whopping 36 * 5 * 5 = 900 models being

built, making nested cross-validation a very expensive procedure. Here,

we used the same cross-validation splitter in the inner and the outer loop;

however, this is not necessary and you can use any combination of

cross-validation strategies in the inner and outer loops. It can be a bit

tricky to understand what is happening in the single line given above,

and it can be helpful to visualize it as for loops, as done in the

following simplified implementation:

In[39]:

defnested_cv(X,y,inner_cv,outer_cv,Classifier,parameter_grid):outer_scores=[]# for each split of the data in the outer cross-validation# (split method returns indices of training and test parts)fortraining_samples,test_samplesinouter_cv.split(X,y):# find best parameter using inner cross-validationbest_parms={}best_score=-np.inf# iterate over parametersforparametersinparameter_grid:# accumulate score over inner splitscv_scores=[]# iterate over inner cross-validationforinner_train,inner_testininner_cv.split(X[training_samples],y[training_samples]):# build classifier given parameters and training dataclf=Classifier(**parameters)clf.fit(X[inner_train],y[inner_train])# evaluate on inner test setscore=clf.score(X[inner_test],y[inner_test])cv_scores.append(score)# compute mean score over inner foldsmean_score=np.mean(cv_scores)ifmean_score>best_score:# if better than so far, remember parametersbest_score=mean_scorebest_params=parameters# build classifier on best parameters using outer training setclf=Classifier(**best_params)clf.fit(X[training_samples],y[training_samples])# evaluateouter_scores.append(clf.score(X[test_samples],y[test_samples]))returnnp.array(outer_scores)

Now, let’s run this function on the iris dataset:

In[40]:

fromsklearn.model_selectionimportParameterGrid,StratifiedKFoldscores=nested_cv(iris.data,iris.target,StratifiedKFold(5),StratifiedKFold(5),SVC,ParameterGrid(param_grid))("Cross-validation scores: {}".format(scores))

Out[40]:

Cross-validation scores: [0.967 1. 0.967 0.967 1. ]

Parallelizing cross-validation and grid search

While running a grid search over many parameters and on large datasets

can be computationally challenging, it is also embarrassingly

parallel. This means that building a model using a particular parameter

setting on a particular cross-validation split can be done completely

independently from the other parameter settings and models. This makes

grid search and cross-validation ideal candidates for parallelization

over multiple CPU cores or over a cluster. You can make use of multiple

cores in GridSearchCV and cross_val_score by setting the n_jobs

parameter to the number of CPU cores you want to use. You can set

n_jobs=-1 to use all available cores.

Setting n_jobs in both the model and GridSearchCV is supported since

scikit-learn 0.20.0, but is not well tested yet. If your dataset and

model are very large, it might be that using many cores uses up too much

memory, and you should monitor your memory usage when building large

models in parallel.

It is also possible to parallelize grid search and cross-validation over

multiple machines in a cluster by using the distributed computing

package dask. See http://distributed.dask.org/en/latest/joblib.html

for more details.

5.3 Evaluation Metrics and Scoring

So far, we have evaluated classification performance using accuracy (the fraction of correctly classified samples) and regression performance using R2. However, these are only two of the many possible ways to summarize how well a supervised model performs on a given dataset. In practice, these evaluation metrics might not be appropriate for your application, and it is important to choose the right metric when selecting between models and adjusting parameters.

5.3.1 Keep the End Goal in Mind

When selecting a metric, you should always have the end goal of the machine learning application in mind. In practice, we are usually interested not just in making accurate predictions, but in using these predictions as part of a larger decision-making process. Before picking a machine learning metric, you should think about the high-level goal of the application, often called the business metric. The consequences of choosing a particular algorithm for a machine learning application are called the business impact.2 Maybe the high-level goal is avoiding traffic accidents, or decreasing the number of hospital admissions. It could also be getting more users for your website, or having users spend more money in your shop. When choosing a model or adjusting parameters, you should pick the model or parameter values that have the most positive influence on the business metric. Often this is hard, as assessing the business impact of a particular model might require putting it in production in a real-life system.

In the early stages of development, and for adjusting parameters, it is often infeasible to put models into production just for testing purposes, because of the high business or personal risks that can be involved. Imagine evaluating the pedestrian avoidance capabilities of a self-driving car by just letting it drive around, without verifying it first; if your model is bad, pedestrians will be in trouble! Therefore we often need to find some surrogate evaluation procedure, using an evaluation metric that is easier to compute. For example, we could test classifying images of pedestrians against non-pedestrians and measure accuracy. Keep in mind that this is only a surrogate, and it pays off to find the closest metric to the original business goal that is feasible to evaluate. This closest metric should be used whenever possible for model evaluation and selection. The result of this evaluation might not be a single number—the consequence of your algorithm could be that you have 10% more customers, but each customer will spend 15% less—but it should capture the expected business impact of choosing one model over another.

In this section, we will first discuss metrics for the important special case of binary classification, then turn to multiclass classification and finally regression.

5.3.2 Metrics for Binary Classification

Binary classification is arguably the most common and conceptually simple application of machine learning in practice. However, there are still a number of caveats in evaluating even this simple task. Before we dive into alternative metrics, let’s have a look at the ways in which measuring accuracy might be misleading. Remember that for binary classification, we often speak of a positive class and a negative class, with the understanding that the positive class is the one we are looking for.

Kinds of errors

Often, accuracy is not a good measure of predictive performance, as the number of mistakes we make does not contain all the information we are interested in. Imagine an application to screen for the early detection of cancer using an automated test. If the test is negative, the patient will be assumed healthy, while if the test is positive, the patient will undergo additional screening. Here, we would call a positive test (an indication of cancer) the positive class, and a negative test the negative class. We can’t assume that our model will always work perfectly, and it will make mistakes. For any application, we need to ask ourselves what the consequences of these mistakes might be in the real world.

One possible mistake is that a healthy patient will be classified as positive, leading to additional testing. This leads to some costs and an inconvenience for the patient (and possibly some mental distress). An incorrect positive prediction is called a false positive. The other possible mistake is that a sick patient will be classified as negative, and will not receive further tests and treatment. The undiagnosed cancer might lead to serious health issues, and could even be fatal. A mistake of this kind—an incorrect negative prediction—is called a false negative. In statistics, a false positive is also known as type I error, and a false negative as type II error. We will stick to “false negative” and “false positive,” as they are more explicit and easier to remember. In the cancer diagnosis example, it is clear that we want to avoid false negatives as much as possible, while false positives can be viewed as more of a minor nuisance.

While this is a particularly drastic example, the consequence of false positives and false negatives are rarely the same. In commercial applications, it might be possible to assign dollar values to both kinds of mistakes, which would allow measuring the error of a particular prediction in dollars, instead of accuracy. This might be much more meaningful for making business decisions on which model to use.

Imbalanced datasets

Types of errors play an important role when one of two classes is much more frequent than the other one. This is very common in practice; a good example is click-through prediction, where each data point represents an “impression,” an item that was shown to a user. This item might be an ad, or a related story, or a related person to follow on a social media site. The goal is to predict whether, if shown a particular item, a user will click on it (indicating they are interested). Most things users are shown on the Internet (in particular, ads) will not result in a click. You might need to show a user 100 ads or articles before they find something interesting enough to click on. This results in a dataset where for each 99 “no click” data points, there is 1 “clicked” data point; in other words, 99% of the samples belong to the “no click” class. Datasets in which one class is much more frequent than the other are often called imbalanced datasets, or datasets with imbalanced classes. In reality, imbalanced data is the norm, and it is rare that the events of interest have equal or even similar frequency in the data.

Now let’s say you build a classifier that is 99% accurate on the click prediction task. What does that tell you? 99% accuracy sounds impressive, but this doesn’t take the class imbalance into account. You can achieve 99% accuracy without building a machine learning model, by always predicting “no click.” On the other hand, even with imbalanced data, a 99% accurate model could in fact be quite good. However, accuracy doesn’t allow us to distinguish the constant “no click” model from a potentially good model.

To illustrate, we’ll create a 9:1 imbalanced dataset from the digits

dataset, by classifying the digit 9 against the nine other classes:

In[41]:

fromsklearn.datasetsimportload_digitsdigits=load_digits()y=digits.target==9X_train,X_test,y_train,y_test=train_test_split(digits.data,y,random_state=0)

We can use the DummyClassifier to always predict the majority class

(here “not nine”) to see how uninformative accuracy can be:

In[42]:

fromsklearn.dummyimportDummyClassifierdummy_majority=DummyClassifier(strategy='most_frequent').fit(X_train,y_train)pred_most_frequent=dummy_majority.predict(X_test)("Unique predicted labels: {}".format(np.unique(pred_most_frequent)))("Test score: {:.2f}".format(dummy_majority.score(X_test,y_test)))

Out[42]:

Unique predicted labels: [False] Test score: 0.90

We obtained close to 90% accuracy without learning anything. This might seem striking, but think about it for a minute. Imagine someone telling you their model is 90% accurate. You might think they did a very good job. But depending on the problem, that might be possible by just predicting one class! Let’s compare this against using an actual classifier:

In[43]:

fromsklearn.treeimportDecisionTreeClassifiertree=DecisionTreeClassifier(max_depth=2).fit(X_train,y_train)pred_tree=tree.predict(X_test)("Test score: {:.2f}".format(tree.score(X_test,y_test)))

Out[43]:

Test score: 0.92

According to accuracy, the DecisionTreeClassifier is only slightly

better than the constant predictor. This could indicate either that

something is wrong with how we used DecisionTreeClassifier, or that

accuracy is in fact not a good measure here.

For comparison purposes, let’s evaluate two more classifiers,

LogisticRegression and the default DummyClassifier, which makes

random predictions but produces classes with the same proportions as in

the training set:

In[44]:

fromsklearn.linear_modelimportLogisticRegressiondummy=DummyClassifier().fit(X_train,y_train)pred_dummy=dummy.predict(X_test)("dummy score: {:.2f}".format(dummy.score(X_test,y_test)))logreg=LogisticRegression(C=0.1).fit(X_train,y_train)pred_logreg=logreg.predict(X_test)("logreg score: {:.2f}".format(logreg.score(X_test,y_test)))

Out[44]:

dummy score: 0.80 logreg score: 0.98

The dummy classifier that produces random output is clearly the worst of

the lot (according to accuracy), while LogisticRegression produces

very good results. However, even the random classifier yields over 80%

accuracy. This makes it very hard to judge which of these results is

actually helpful. The problem here is that accuracy is an inadequate

measure for quantifying predictive performance in this imbalanced

setting. For the rest of this chapter, we will explore alternative

metrics that provide better guidance in selecting models. In particular,

we would like to have metrics that tell us how much better a model is

than making “most frequent” predictions or random predictions, as they

are computed in pred_most_frequent and pred_dummy. If we use a

metric to assess our models, it should definitely be able to weed out

these nonsense predictions.

Confusion matrices

One of the most comprehensive ways to represent the result of evaluating

binary classification is using confusion matrices.

Let’s inspect the

predictions of LogisticRegression from the previous section using the confusion_matrix

function. We already stored the predictions on the test set in

pred_logreg:

In[45]:

fromsklearn.metricsimportconfusion_matrixconfusion=confusion_matrix(y_test,pred_logreg)("Confusion matrix:\n{}".format(confusion))

Out[45]:

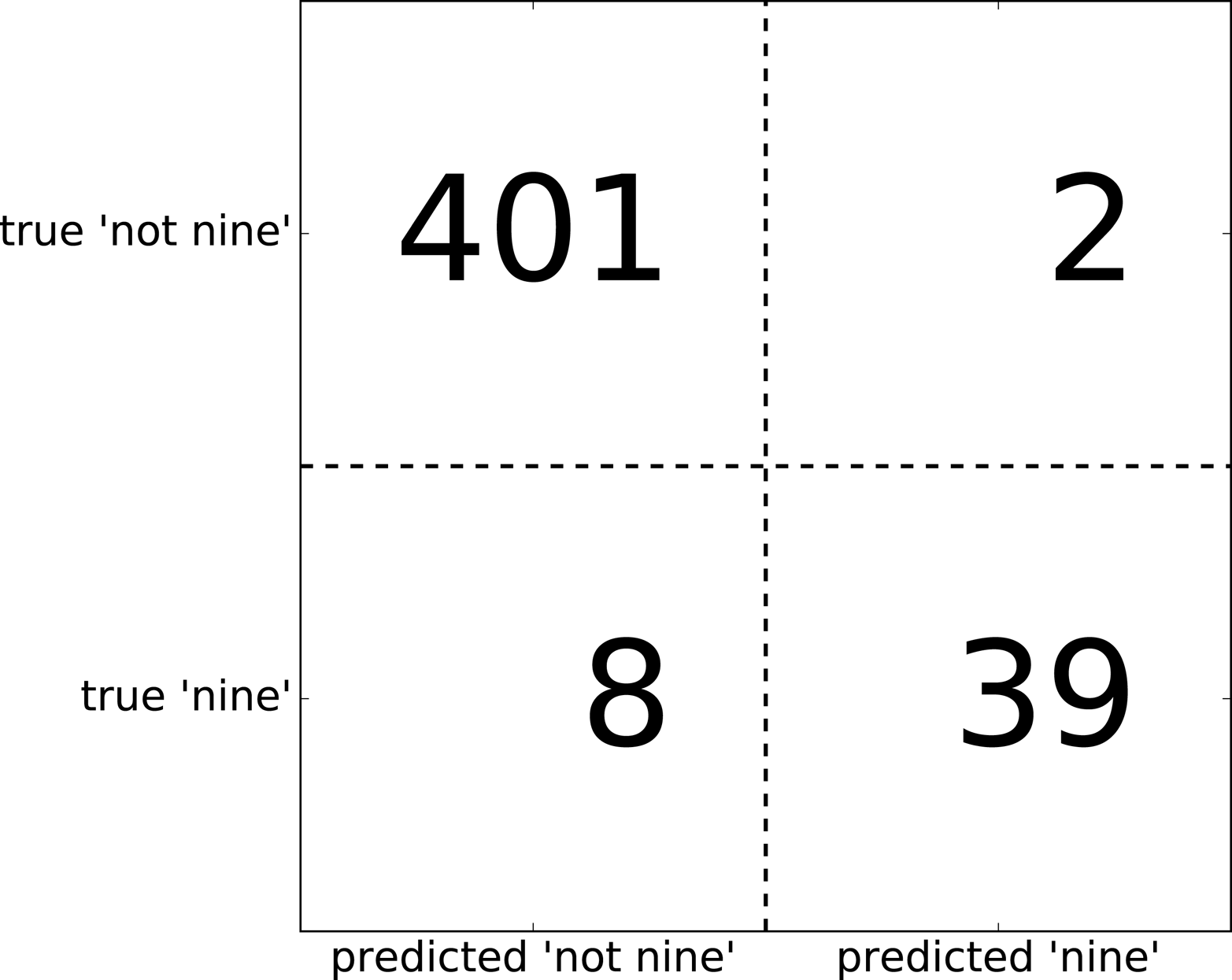

Confusion matrix: [[401 2] [ 8 39]]

The output of confusion_matrix is a two-by-two array, where the rows

correspond to the true classes and the columns correspond to the

predicted classes. Each entry counts how often a sample that belongs to

the class corresponding to the row (here, “not nine” and “nine”) was classified

as the class corresponding to the column. The following plot (Figure 5-10)

illustrates this meaning:

In[46]:

mglearn.plots.plot_confusion_matrix_illustration()

Figure 5-10. Confusion matrix of the “nine vs. rest” classification task

Entries on the main diagonal3 of the confusion matrix correspond to correct classifications, while other entries tell us how many samples of one class got mistakenly classified as another class.

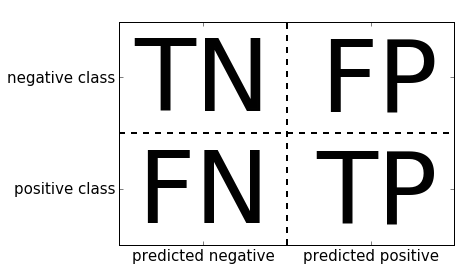

If we declare “a nine” the positive class, we can relate the entries of the confusion matrix with the terms false positive and false negative that we introduced earlier. To complete the picture, we call correctly classified samples belonging to the positive class true positives and correctly classified samples belonging to the negative class true negatives. These terms are usually abbreviated FP, FN, TP, and TN and lead to the following interpretation for the confusion matrix (Figure 5-11):

In[47]:

mglearn.plots.plot_binary_confusion_matrix()

Figure 5-11. Confusion matrix for binary classification

Now let’s use the confusion matrix to compare the models we fitted earlier (the two dummy models, the decision tree, and the logistic regression):

In[48]:

("Most frequent class:")(confusion_matrix(y_test,pred_most_frequent))("\nDummy model:")(confusion_matrix(y_test,pred_dummy))("\nDecision tree:")(confusion_matrix(y_test,pred_tree))("\nLogistic Regression")(confusion_matrix(y_test,pred_logreg))

Out[48]:

Most frequent class: [[403 0] [ 47 0]] Dummy model: [[361 42] [ 43 4]] Decision tree: [[390 13] [ 24 23]] Logistic Regression [[401 2] [ 8 39]]

Looking at the confusion matrix, it is quite clear that something is

wrong with pred_most_frequent, because it always predicts the same

class. pred_dummy, on the other hand, has a very small number of true

positives (4), particularly compared to the number of false negatives

and false positives—there are many more false positives than true

positives! The predictions made by the decision tree make much more sense than

the dummy predictions, even though the accuracy was nearly the same.

Finally, we can see that logistic regression does better than pred_tree in

all aspects: it has more true positives and true negatives while having

fewer false positives and false negatives. From this comparison, it is

clear that only the decision tree and the logistic regression give reasonable

results, and that the logistic regression works better than the tree on

all accounts. However, inspecting the full confusion matrix is a bit

cumbersome, and while we gained a lot of insight from looking at all

aspects of the matrix, the process was very manual and qualitative.

There are several ways to summarize the information in the confusion

matrix, which we will discuss next.

Relation to accuracy

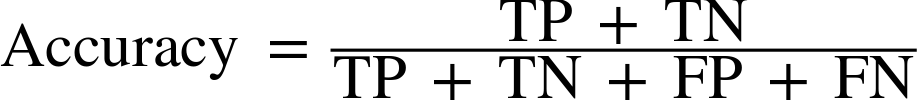

We already saw one way to summarize the result in the confusion matrix—by computing accuracy, which can be expressed as:

In other words, accuracy is the number of correct predictions (TP and TN) divided by the number of all samples (all entries of the confusion matrix summed up).

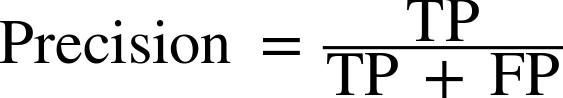

Precision, recall, and f-score

There are several other ways to summarize the confusion matrix, with the most common ones being precision and recall. Precision measures how many of the samples predicted as positive are actually positive:

Precision is used as a performance metric when the goal is to limit the number of false positives. As an example, imagine a model for predicting whether a new drug will be effective in treating a disease in clinical trials. Clinical trials are notoriously expensive, and a pharmaceutical company will only want to run an experiment if it is very sure that the drug will actually work. Therefore, it is important that the model does not produce many false positives—in other words, that it has a high precision. Precision is also known as positive predictive value (PPV).

Recall, on the other hand, measures how many of the positive samples are captured by the positive predictions:

Recall is used as performance metric when we need to identify all positive samples; that is, when it is important to avoid false negatives. The cancer diagnosis example from earlier in this chapter is a good example for this: it is important to find all people that are sick, possibly including healthy patients in the prediction. Other names for recall are sensitivity, hit rate, or true positive rate (TPR).

There is a trade-off between optimizing recall and optimizing precision. You can trivially obtain a perfect recall if you predict all samples to belong to the positive class—there will be no false negatives, and no true negatives either. However, predicting all samples as positive will result in many false positives, and therefore the precision will be very low. On the other hand, if you find a model that predicts only the single data point it is most sure about as positive and the rest as negative, then precision will be perfect (assuming this data point is in fact positive), but recall will be very bad.

Tip

Precision and recall are only two of many classification measures derived from TP, FP, TN, and FN. You can find a great summary of all the measures on Wikipedia. In the machine learning community, precision and recall are arguably the most commonly used measures for binary classification, but other communities might use other related metrics.

So, while precision and recall are very important measures, looking at only one of them will not provide you with the full picture. One way to summarize them is the f-score or f-measure, which is with the harmonic mean of precision and recall:

This particular variant is also known as the f1-score. As

it takes precision and recall into account, it can be a better measure

than accuracy on imbalanced binary classification datasets. Let’s run it

on the predictions for the “nine vs. rest” dataset that we computed

earlier. Here, we will assume that the “nine” class is the positive

class (it is labeled as True while the rest is labeled as False), so

the positive class is the minority class:

In[49]:

fromsklearn.metricsimportf1_score("f1 score most frequent: {:.2f}".format(f1_score(y_test,pred_most_frequent)))("f1 score dummy: {:.2f}".format(f1_score(y_test,pred_dummy)))("f1 score tree: {:.2f}".format(f1_score(y_test,pred_tree)))("f1 score logistic regression: {:.2f}".format(f1_score(y_test,pred_logreg)))

Out[49]:

f1 score most frequent: 0.00 f1 score dummy: 0.10 f1 score tree: 0.55 f1 score logistic regression: 0.89

We can note two things here. First, we get an error message for the most_frequent

prediction, as there were no predictions of the positive class (which

makes the denominator in the f-score zero). Also, we can see a pretty

strong distinction between the dummy predictions and the tree

predictions, which wasn’t clear when looking at accuracy alone. Using

the f-score for evaluation, we summarized the predictive performance

again in one number. However, the f-score seems to capture our intuition

of what makes a good model much better than accuracy did. A disadvantage

of the f-score, however, is that it is harder to interpret and explain

than accuracy.

If we want a more comprehensive summary of precision, recall, and f1-score, we can use the classification_report convenience function to

compute all three at once, and print them in a nice format:

In[50]:

fromsklearn.metricsimportclassification_report(classification_report(y_test,pred_most_frequent,target_names=["not nine","nine"]))

Out[50]:

precision recall f1-score support

not nine 0.90 1.00 0.94 403

nine 0.00 0.00 0.00 47

micro avg 0.90 0.90 0.90 450

macro avg 0.45 0.50 0.47 450

weighted avg 0.80 0.90 0.85 450

The classification_report function produces one line per class (here,

True and False) and reports precision, recall, and f-score with this

class as the positive class. Before, we assumed the minority “nine”

class was the positive class. If we change the positive class to “not

nine,” we can see from the output of classification_report that we

obtain an f-score of 0.94 with the most_frequent model. Furthermore,

for the “not nine” class we have a recall of 1, as we classified all

samples as “not nine.” The last column next to the f-score provides the

support of each class, which simply means the number of samples in

this class according to the ground truth.

Three additional rows in the classification report show averages of the precision, recall, and f1-score. The macro average simply computes the average across the classes, while the weighted average computes a weighted average, weighted by the number of samples in the class. Because they are averages over both classes, these metrics don’t require a notion of positive class, and in contrast to just looking at precision or just looking at recall for the positive class, averaging over both classes provides a meaningful metric in a single number. Here are two more reports, one for the dummy classifier and one for the logistic regression:

In[51]:

(classification_report(y_test,pred_dummy,target_names=["not nine","nine"]))

Out[51]:

precision recall f1-score support

not nine 0.90 0.89 0.90 403

nine 0.17 0.19 0.18 47

micro avg 0.82 0.82 0.82 450

macro avg 0.54 0.54 0.54 450

weighted avg 0.83 0.82 0.82 450

In[52]:

(classification_report(y_test,pred_logreg,target_names=["not nine","nine"]))

Out[52]:

precision recall f1-score support

not nine 0.98 1.00 0.99 403

nine 0.95 0.83 0.89 47

micro avg 0.98 0.98 0.98 450

macro avg 0.97 0.91 0.94 450

weighted avg 0.98 0.98 0.98 450

As you may notice when looking at the reports, the differences between the dummy models and a very good model are not as clear any more. Picking which class is declared the positive class has a big impact on the metrics. While the f-score for the dummy classification is 0.10 (vs. 0.89 for the logistic regression) on the “nine” class, for the “not nine” class it is 0.91 vs. 0.99, which both seem like reasonable results. Looking at all the numbers together paints a pretty accurate picture, though, and we can clearly see the superiority of the logistic regression model.

Taking uncertainty into account

The confusion matrix and the classification report provide a very

detailed analysis of a particular set of predictions. However, the

predictions themselves already threw away a lot of information that is

contained in the model. As we discussed in Chapter 2, most classifiers

provide a decision_function or a predict_proba method to assess

degrees of certainty about predictions. Making predictions can be seen

as thresholding the output of decision_function or predict_proba at

a certain fixed point—in binary classification we use 0 for the

decision function and 0.5 for predict_proba.

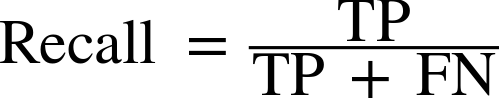

The following is an example of an imbalanced binary classification task, with

400 points in the negative class classified against 50 points in the

positive class. The training data is shown on the left in

Figure 5-12. We train a kernel SVM model on this data, and the

plots to the right of the training data illustrate the values of the decision

function as a heat map. You can see a black circle in the plot in the

top center, which denotes the threshold of the decision_function being

exactly zero. Points inside this circle will be classified as the

positive class, and points outside as the negative class:

In[53]:

X,y=make_blobs(n_samples=(400,50),cluster_std=[7.0,2],random_state=22)X_train,X_test,y_train,y_test=train_test_split(X,y,random_state=0)svc=SVC(gamma=.05).fit(X_train,y_train)

In[54]:

mglearn.plots.plot_decision_threshold()

Figure 5-12. Heatmap of the decision function and the impact of changing the decision threshold

We can use the classification_report function to evaluate precision and recall

for both classes:

In[55]:

(classification_report(y_test,svc.predict(X_test)))

Out[55]:

precision recall f1-score support

0 0.97 0.89 0.93 104

1 0.35 0.67 0.46 9

micro avg 0.88 0.88 0.88 113

macro avg 0.66 0.78 0.70 113

weighted avg 0.92 0.88 0.89 113

For class 1, we get a fairly small precision, and recall is mixed. Because class 0 is so much larger, the classifier focuses on getting class 0 right, and not the smaller class 1.

Let’s assume in our application it is more important to have a high

recall for class 1, as in the cancer screening example earlier. This

means we are willing to risk more false positives (false class 1) in

exchange for more true positives (which will increase the recall). The

predictions generated by svc.predict really do not fulfill this

requirement, but we can adjust the predictions to focus on a higher

recall of class 1 by changing the decision threshold away from 0. By

default, points with a decision_function value greater than 0 will be

classified as class 1. We want more points to be classified as class

1, so we need to decrease the threshold:

In[56]:

y_pred_lower_threshold=svc.decision_function(X_test)>-.8

Let’s look at the classification report for this prediction:

In[57]:

(classification_report(y_test,y_pred_lower_threshold))

Out[57]:

precision recall f1-score support

0 1.00 0.82 0.90 104

1 0.32 1.00 0.49 9

micro avg 0.83 0.83 0.83 113

macro avg 0.66 0.91 0.69 113

weighted avg 0.95 0.83 0.87 113

As expected, the recall of class 1 went up, and the precision went down.

We are now classifying a larger region of space as class 1, as

illustrated in the top-right panel of Figure 5-12. If you value precision over recall or the other way

around, or you data is heavily imbalanced, changing the decision

threshold is the easiest way to obtain better results. As the

decision_function can have arbitrary ranges, it is hard to provide a

rule of thumb regarding how to pick a threshold. If you do set a

threshold, you need to be careful not to do so using the test set. As

with any other parameter, setting a decision threshold on the test set

is likely to yield overly optimistic results. Use a validation set or

cross-validation instead.

Warning

For simplicity, we changed the threshold value based on test set results in the code above. In practice, you need to use a hold-out validation set, not the test set. As with any other parameter, setting a decision threshold on the test set is likely to yield overly optimistic results. Use a validation set or cross-validation instead.

Picking a threshold for models that implement the predict_proba method

can be easier, as the output of predict_proba is on a fixed 0 to

1 scale, and models probabilities. By default, the threshold of 0.5

means that if the model is more than 50% “sure” that a point is of the

positive class, it will be classified as such. Increasing the threshold

means that the model needs to be more confident to make a positive

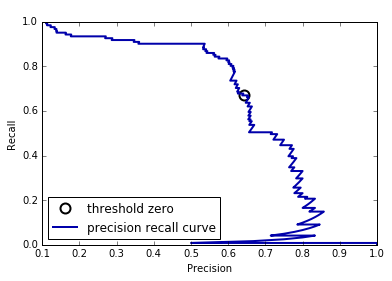

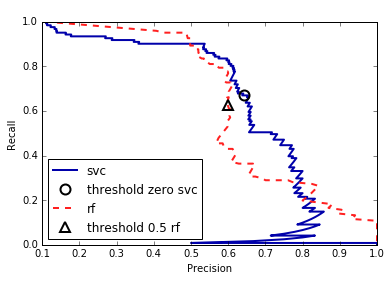

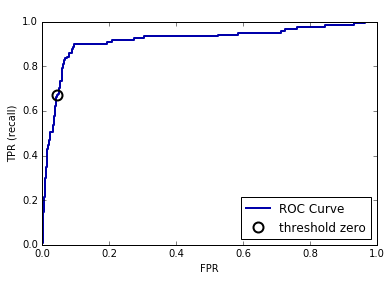

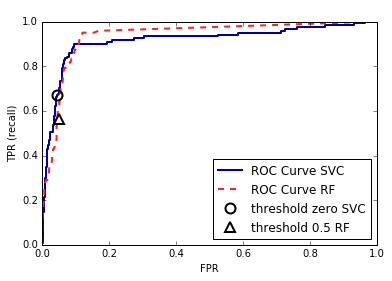

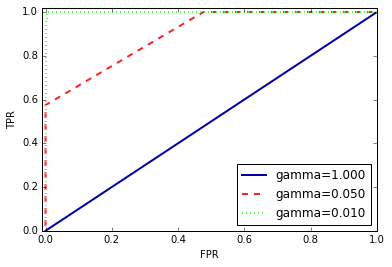

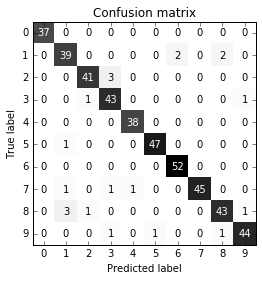

decision (and less confident to make a negative decision). While working