20

Additional Library Utilities

RATIOS

The Ratio library allows you to exactly represent any finite rational number that you can use at compile time. Ratios are used in the std::chrono::duration class discussed in the next section. Everything is defined in the <ratio> header file and is in the std namespace. The numerator and denominator of a rational number are represented as compile-time constants of type std::intmax_t, which is a signed integer type with the maximum width supported by a compiler. Because of the compile-time nature of these rational numbers, using them might look a bit complicated and different than what you are used to. You cannot define a ratio object the same way as you define normal objects, and you cannot call methods on it. Instead, you need to use type aliases. For example, the following line defines a rational compile-time constant representing the fraction 1/60:

using r1 = ratio<1, 60>;The numerator and denominator of the r1 rational number are compile-time constants and can be accessed as follows:

intmax_t num = r1::num;intmax_t den = r1::den;

Remember that a ratio is a compile-time constant, which means that the numerator and denominator need to be known at compile time. The following generates a compilation error:

intmax_t n = 1;intmax_t d = 60;using r1 = ratio<n, d>; // Error

Making n and d constants removes the error:

const intmax_t n = 1;const intmax_t d = 60;using r1 = ratio<n, d>; // Ok

Rational numbers are always normalized. For a rational number ratio<n, d>, the greatest common divisor, gcd, is calculated and the numerator, num, and denominator, den, are then defined as follows:

num = sign(n)*sign(d)*abs(n)/gcdden = abs(d)/gcd

The library supports adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing rational numbers. Because all these operations are also happening at compile time, you cannot use the standard arithmetic operators. Instead, you need to use specific templates in combination with type aliases. The following arithmetic ratio templates are available: ratio_add, ratio_subtract, ratio_multiply, and ratio_divide. These templates calculate the result as a new ratio type. This type can be accessed with the embedded type alias called type. For example, the following code first defines two ratios, one representing 1/60 and the other representing 1/30. The ratio_add template adds those two rational numbers together to produce the result rational number, which, after normalization, is 1/20.

using r1 = ratio<1, 60>;using r2 = ratio<1, 30>;using result = ratio_add<r1, r2>::type;

The standard also defines a number of ratio comparison templates: ratio_equal, ratio_not_equal, ratio_less, ratio_less_equal, ratio_greater, and ratio_greater_equal. Just like the arithmetic ratio templates, the ratio comparison templates are all evaluated at compile time. These comparison templates define a new type that is an std::bool_constant, representing the result. bool_constant is an std::integral_constant, a struct template that stores a type and a compile-time constant value. For example, integral_constant<int, 15> stores an integer with value 15. bool_constant is an integral_constant with type bool. For instance, bool_constant<true> is integral_constant<bool, true>, which stores a Boolean with value true. The result of the ratio comparison templates is either bool_constant<true> or bool_constant<false>. The value associated with a bool_constant or an integral_constant can be accessed using the value data member. The following example demonstrates the use of ratio_less. Chapter 13 discusses the use of boolalpha to output true or false for Boolean values.

using r1 = ratio<1, 60>;using r2 = ratio<1, 30>;using res = ratio_less<r2, r1>;cout << boolalpha << res::value << endl;

The following example combines everything I have just covered. Note that because ratios are compile-time constants, you cannot do something like cout << r1; you need to get the numerator and denominator and print them separately.

// Define a compile-time rational numberusing r1 = ratio<1, 60>;cout << "1) " << r1::num << "/" << r1::den << endl;// Get numerator and denominatorintmax_t num = r1::num;intmax_t den = r1::den;cout << "2) " << num << "/" << den << endl;// Add two rational numbersusing r2 = ratio<1, 30>;cout << "3) " << r2::num << "/" << r2::den << endl;using result = ratio_add<r1, r2>::type;cout << "4) " << result::num << "/" << result::den << endl;// Compare two rational numbersusing res = ratio_less<r2, r1>;cout << "5) " << boolalpha << res::value << endl;

The output is as follows:

1) 1/602) 1/603) 1/304) 1/205) false

The library provides a number of SI (Système International) type aliases for your convenience. They are as follows:

using yocto = ratio<1, 1'000'000'000'000'000'000'000'000>; // *using zepto = ratio<1, 1'000'000'000'000'000'000'000>; // *using atto = ratio<1, 1'000'000'000'000'000'000>;using femto = ratio<1, 1'000'000'000'000'000>;using pico = ratio<1, 1'000'000'000'000>;using nano = ratio<1, 1'000'000'000>;using micro = ratio<1, 1'000'000>;using milli = ratio<1, 1'000>;using centi = ratio<1, 100>;using deci = ratio<1, 10>;using deca = ratio<10, 1>;using hecto = ratio<100, 1>;using kilo = ratio<1'000, 1>;using mega = ratio<1'000'000, 1>;using giga = ratio<1'000'000'000, 1>;using tera = ratio<1'000'000'000'000, 1>;using peta = ratio<1'000'000'000'000'000, 1>;using exa = ratio<1'000'000'000'000'000'000, 1>;using zetta = ratio<1'000'000'000'000'000'000'000, 1>; // *using yotta = ratio<1'000'000'000'000'000'000'000'000, 1>; // *

The SI units with an asterisk at the end are defined only if your compiler can represent the constant numerator and denominator values for those type aliases as an intmax_t. An example of how to use these predefined SI units is given in the discussion of durations in the next section.

THE CHRONO LIBRARY

The chrono library is a collection of classes that work with times. The library consists of the following components:

- Durations

- Clocks

- Time points

Everything is defined in the std::chrono namespace and requires you to include the <chrono> header file. The following sections explain each component.

Duration

A duration is an interval between two points in time. It is represented by the duration class template, which stores a number of ticks and a tick period. The tick period is the time in seconds between two ticks and is represented as a compile-time ratio constant, which means it could be a fraction of a second. Ratios are discussed in the previous section. The duration template accepts two template parameters and is defined as follows:

template <class Rep, class Period = ratio<1>> class duration {...}The first template parameter, Rep, is the type of variable storing the number of ticks and should be an arithmetic type, for example long, double, and so on. The second template parameter, Period, is the rational constant representing the period of a tick. If you don’t specify the tick period, the default value ratio<1> is used, which represents a tick period of one second.

Three constructors are provided: the default constructor; one that accepts a single value, the number of ticks; and one that accepts another duration. The latter constructor can be used to convert from one duration to another duration, for example, from minutes to seconds. An example is given later in this section.

Durations support arithmetic operations such as +, -, *, /, %, ++, --, +=, -=, *=, /=, and %=, and support the comparison operators. The class also contains the methods shown in the following table.

| METHOD | DESCRIPTION |

Rep count() const |

Returns the duration value as the number of ticks. The return type is the type specified as a parameter to the duration template. |

static duration zero() |

Returns a duration with a duration value equivalent to zero. |

static duration min()static duration max() |

Returns a duration with the minimum/maximum possible duration value representable by the type specified as a parameter to the duration template. |

C++17 adds floor(), ceil(), round(), and abs() operations for durations that behave just as they behave with numerical data.

Let’s see how durations can be used in actual code. A duration where each tick is one second can be defined as follows:

duration<long> d1;Because ratio<1> is the default tick period, this is the same as writing the following:

duration<long, ratio<1>> d1;The following defines a duration in minutes (tick period = 60 seconds):

duration<long, ratio<60>> d2;To define a duration where each tick period is a sixtieth of a second, use the following:

duration<double, ratio<1, 60>> d3;As you saw earlier in this chapter, the <ratio> header file defines a number of SI rational constants. These predefined constants come in handy for defining tick periods. For example, the following line of code defines a duration where each tick period is one millisecond:

duration<long long, milli> d4;The following example demonstrates several aspects of durations. It shows you how to define durations, how to perform arithmetic operations on them, and how to convert one duration into another duration with a different tick period.

// Specify a duration where each tick is 60 secondsduration<long, ratio<60>> d1(123);cout << d1.count() << endl;// Specify a duration represented by a double with each tick// equal to 1 second and assign the largest possible duration to it.duration<double> d2;d2 = d2.max();cout << d2.count() << endl;// Define 2 durations:// For the first duration, each tick is 1 minute// For the second duration, each tick is 1 secondduration<long, ratio<60>> d3(10); // = 10 minutesduration<long, ratio<1>> d4(14); // = 14 seconds// Compare both durationsif (d3 > d4)cout << "d3 > d4" << endl;elsecout << "d3 <= d4" << endl;// Increment d4 with 1 resulting in 15 seconds++d4;// Multiply d4 by 2 resulting in 30 secondsd4 *= 2;// Add both durations and store as minutesduration<double, ratio<60>> d5 = d3 + d4;// Add both durations and store as secondsduration<long, ratio<1>> d6 = d3 + d4;cout << d3.count() << " minutes + " << d4.count() << " seconds = "<< d5.count() << " minutes or "<< d6.count() << " seconds" << endl;// Create a duration of 30 secondsduration<long> d7(30);// Convert the seconds of d7 to minutesduration<double, ratio<60>> d8(d7);cout << d7.count() << " seconds = " << d8.count() << " minutes" << endl;

The output is as follows:

1231.79769e+308d3 > d410 minutes + 30 seconds = 10.5 minutes or 630 seconds30 seconds = 0.5 minutes

Pay special attention to the following two lines:

duration<double, ratio<60>> d5 = d3 + d4;duration<long, ratio<1>> d6 = d3 + d4;

They both calculate d3+d4 but the first line stores it as a floating point value representing minutes, while the second line stores the result as an integral value representing seconds. Conversion from minutes to seconds or vice versa happens automatically.

The following two lines from the preceding example demonstrate how to explicitly convert between different units of time:

duration<long> d7(30); // secondsduration<double, ratio<60>> d8(d7); // minutes

The first line defines a duration representing 30 seconds. The second line converts these 30 seconds into minutes, resulting in 0.5 minutes. Converting in this direction can result in a non-integral value, and thus requires you to use a duration represented by a floating point type; otherwise, you will get some cryptic compilation errors. The following lines, for example, do not compile because d8 is using long instead of a floating point type:

duration<long> d7(30); // secondsduration<long, ratio<60>> d8(d7);// minutes // Error!

You can, however, force this conversion by using duration_cast():

duration<long> d7(30); // secondsauto d8 = duration_cast<duration<long, ratio<60>>>(d7);// minutes

In this case, d8 will be 0 minutes, because integer division is used to convert 30 seconds to minutes.

Converting in the other direction does not require floating point types if the source is an integral type, because the result is always an integral value if you started with an integral value. For example, the following lines convert ten minutes into seconds, both represented by the integral type long:

duration<long, ratio<60>> d9(10); // minutesduration<long> d10(d9); // seconds

The library provides the following standard duration types in the std::chrono namespace:

using nanoseconds = duration<X 64 bits, nano>;using microseconds = duration<X 55 bits, micro>;using milliseconds = duration<X 45 bits, milli>;using seconds = duration<X 35 bits>;using minutes = duration<X 29 bits, ratio<60>>;using hours = duration<X 23 bits, ratio<3600>>;

The exact type of X depends on your compiler, but the C++ standard requires it to be a signed integer type of at least the specified size. The preceding type aliases make use of the predefined SI ratio type aliases that are described earlier in this chapter. With these predefined types, instead of writing this,

duration<long, ratio<60>> d9(10); // minutesyou can simply write this:

minutes d9(10); // minutesThe following code is another example of how to use these predefined durations. The code first defines a variable t, which is the result of 1 hour + 23 minutes + 45 seconds. The auto keyword is used to let the compiler automatically figure out the exact type of t. The second line uses the constructor of the predefined seconds duration to convert the value of t to seconds, and writes the result to the console.

auto t = hours(1) + minutes(23) + seconds(45);cout << seconds(t).count() << " seconds" << endl;

Because the standard requires that the predefined durations use integer types, there can be compilation errors if a conversion could end up with a non-integral value. While integer division normally truncates, in the case of durations, which are implemented with ratio types, the compiler declares any computation that could result in a non-zero remainder as a compile-time error. For example, the following code does not compile because converting 90 seconds to minutes results in 1.5 minutes:

seconds s(90);minutes m(s);

However, the following code does not compile either, even though 60 seconds is exactly 1 minute. It is flagged as a compile-time error because converting from seconds to minutes could result in non-integral values.

seconds s(60);minutes m(s);

Converting in the other direction works perfectly fine because the minutes duration uses an integral type and converting it to seconds always results in an integral value:

minutes m(2);seconds s(m);

You can use the standard user-defined literals “h”, “min”, “s”, “ms”, “us”, and “ns” for creating durations. Technically, these are defined in the std::literals::chrono_literals namespace, but also made accessible with using namespace std::chrono. Here is an example:

using namespace std::chrono;// ...auto myDuration = 42min; // 42 minutes

Clock

A clock is a class consisting of a time_point and a duration. The time_point type is discussed in detail in the next section, but those details are not required to understand how clocks work. However, time_points themselves depend on clocks, so it’s important to know the details of clocks first.

Three clocks are defined by the standard. The first one is called system_clock and represents the wall clock time from the system-wide real-time clock. The second one is called steady_clock, and it guarantees its time_point will never decrease, which is not guaranteed for system_clock because the system clock can be adjusted at any time. The third one is the high_resolution_clock, which has the shortest possible tick period. Depending on your compiler, it is possible for the high_resolution_clock to be a synonym for steady_clock or system_clock.

Every clock has a static now() method to get the current time as a time_point. The system_clock also defines two static helper functions for converting time_points to and from the time_t C-style time representation. The first function is called to_time_t(), and it converts a given time_point to a time_t; the second function is called from_time_t(), and it returns a time_point initialized with a given time_t value. The time_t type is defined in the <ctime> header file.

The following example shows a complete program which gets the current time from the system and outputs the time in a human-readable format to the console. The localtime() function converts a time_t to a local time represented by tm and is defined in the <ctime> header file. The put_time() stream manipulator, defined in the <iomanip> header, is introduced in Chapter 13.

// Get current time as a time_pointsystem_clock::time_point tpoint = system_clock::now();// Convert to a time_ttime_t tt = system_clock::to_time_t(tpoint);// Convert to local timetm* t = localtime(&tt);// Write the time to the consolecout << put_time(t, "%H:%M:%S") << endl;

If you want to convert a time to a string, you can use an std::stringstream or the C-style strftime() function, defined in <ctime>, as follows. Using the strftime() function requires you to supply a buffer that is big enough to hold the human-readable representation of the given time:

// Get current time as a time_pointsystem_clock::time_point tpoint = system_clock::now();// Convert to a time_ttime_t tt = system_clock::to_time_t(tpoint);// Convert to local timetm* t = localtime(&tt);// Convert to readable formatchar buffer[80] = {0};strftime(buffer, sizeof(buffer), "%H:%M:%S", t);// Write the time to the consolecout << buffer << endl;

The chrono library can also be used to time how long it takes for a piece of code to execute. The following example shows how you can do this. The actual type of the variables start and end is high_resolution_clock::time_point, and the actual type of diff is a duration.

// Get the start timeauto start = high_resolution_clock::now();// Execute code that you want to timedouble d = 0;for (int i = 0; i < 1000000; ++i) {d += sqrt(sin(i) * cos(i));}// Get the end time and calculate the differenceauto end = high_resolution_clock::now();auto diff = end - start;// Convert the difference into milliseconds and output to the consolecout << duration<double, milli>(diff).count() << "ms" << endl;

The loop in this example is performing some arithmetic operations with sqrt(), sin(), and cos() to make sure the loop doesn’t end too fast. If you get really small values for the difference in milliseconds on your system, those values will not be accurate and you should increase the number of iterations of the loop to make it last longer. Small timings will not be accurate because, while timers often have a resolution in milliseconds, on most operating systems, this timer is updated infrequently, for example, every 10 ms or 15 ms. This induces a phenomenon called gating error, where any event that occurs in less than one timer tick appears to take place in zero units of time; any event between one and two timer ticks appears to take place in one timer unit. For example, on a system with a 15 ms timer update, a loop that takes 44 ms will appear to take only 30 ms. When using such timers to time computations, it is important to make sure that the entire computation takes place across a fairly large number of basic timer tick units so that these errors are minimized.

Time Point

A point in time is represented by the time_point class and stored as a duration relative to the epoch. A time_point is always associated with a certain clock and the epoch is the origin of this associated clock. For example, the epoch for the classic Unix/Linux time is 1st of January 1970, and durations are measured in seconds. The epoch for Windows is 1st of January 1601 and durations are measured in 100-nanosecond units. Other operating systems have different epoch dates and duration units.

The time_point class contains a function called time_since_epoch(), which returns a duration representing the time between the epoch of the associated clock and the stored point in time.

Arithmetic operations of time_points and durations that make sense are supported. The following table lists those operations. tp is a time_point and d is a duration.

tp + d = tp |

tp – d = tp |

d + tp = tp |

tp – tp = d |

tp += d |

tp -= d |

An example of an operation that is not supported is tp+tp.

Comparison operators are also supported to compare two time points. Two static methods are provided: min(), which returns the smallest possible point in time, and max(), which returns the largest possible point in time.

The time_point class has three constructors.

time_point():This constructs atime_pointinitialized withduration::zero(). The resultingtime_pointrepresents the epoch of the associatedclock.time_point(const duration& d): This constructs atime_pointinitialized with the givenduration. The resultingtime_pointrepresentsepoch + d.template <class Duration2> time_point(const time_point<clock, Duration2>& t): This constructs atime_pointinitialized witht.time_since_epoch().

Each time_point is associated with a clock. To create a time_point, you specify the clock as the template parameter:

time_point<steady_clock> tp1;Each clock also knows its time_point type, so you can also write it as follows:

steady_clock::time_point tp1;The following example demonstrates the time_point class:

// Create a time_point representing the epoch// of the associated steady clocktime_point<steady_clock> tp1;// Add 10 minutes to the time_pointtp1 += minutes(10);// Store the duration between epoch and time_pointauto d1 = tp1.time_since_epoch();// Convert the duration to seconds and output to the consoleduration<double> d2(d1);cout << d2.count() << " seconds" << endl;

The output should be as follows:

600 secondsConverting time_points can be done implicitly or explicitly, similar to duration conversions. Here is an example of an implicit conversion. The output is 42000 ms.

time_point<steady_clock, seconds> tpSeconds(42s);// Convert seconds to milliseconds implicitly.time_point<steady_clock, milliseconds> tpMilliseconds(tpSeconds);cout << tpMilliseconds.time_since_epoch().count() << " ms" << endl;

If the implicit conversion can result in a loss of data, then you need an explicit conversion using time_point_cast(), just as duration_cast() is needed for explicit duration casts. The following example outputs 42000 ms, even though you start from 42,424ms.

time_point<steady_clock, milliseconds> tpMilliseconds(42'424ms);// Convert milliseconds to seconds explicitly.time_point<steady_clock, seconds> tpSeconds(time_point_cast<seconds>(tpMilliseconds));// Convert seconds back to milliseconds and output the result.milliseconds ms(tpSeconds.time_since_epoch());cout << ms.count() << " ms" << endl;

C++17 adds

C++17 adds floor(), ceil(), and round() operations for time_points that behave just as they behave with numerical data.

RANDOM NUMBER GENERATION

Generating good random numbers in software is a complex topic. Before C++11, the only way to generate random numbers was to use the C-style srand() and rand() functions. The srand() function needed to be called once in your application and was used to initialize the random number generator, also called seeding. Usually the current system time would be used as a seed.

Once the generator is initialized, random numbers could be generated with rand(). The following example shows how to use srand() and rand(). The time(nullptr) call returns the system time, and is defined in the <ctime> header file.

srand(static_cast<unsigned int>(time(nullptr)));cout << rand() << endl;

A random number within a certain range can be generated with the following function:

int getRandom(int min, int max){return (rand() % static_cast<int>(max + 1 - min)) + min;}

The old C-style rand() function generates random numbers in the range 0 to RAND_MAX, which is defined by the standard to be at least 32,767. Unfortunately, the low-order bits of rand() are often not very random, which means that using the previous getRandom() function to generate a random number in a small range, such as 1 to 6, will not result in very good randomness.

The old srand() and rand() functions don’t offer much in terms of flexibility. You cannot, for example, change the distribution of the generated random numbers. C++11 has added a powerful library to generate random numbers by using different algorithms and distributions. The library is defined in the <random> header file and has three big components: engines, engine adaptors, and distributions. A random number engine is responsible for generating the actual random numbers and storing the state for generating subsequent random numbers. The distribution determines the range of the generated random numbers and how they are mathematically distributed within that range. A random number engine adaptor modifies the results of a random number engine you associate it with.

It’s highly recommended to stop using srand() and rand(), and to start using the classes from <random>.

Random Number Engines

The following random number engines are available:

random_devicelinear_congruential_enginemersenne_twister_enginesubtract_with_carry_engine

The random_device engine is not a software-based generator; it is a special engine that requires a piece of hardware attached to your computer that generates truly non-deterministic random numbers, for example, by using the laws of physics. A classic mechanism measures the decay of a radioactive isotope by counting alpha-particles-per-time-interval, but there are many other kinds of physics-based random-number generators, including measuring the “noise” of reverse-biased diodes (thus eliminating the concerns about radioactive sources in your computer). The details of these mechanisms fall outside the scope of this book.

According to the specification for random_device, if no such device is attached to the computer, the library is free to use one of the software algorithms. The choice of algorithm is up to the library designer.

The quality of a random number generator is referred to as its entropy measure. The entropy() method of the random_device class returns 0.0 if it is using a software-based pseudo-random number generator, and returns a nonzero value if there is a hardware device attached. The nonzero value is an estimate of the entropy of the attached device.

Using a random_device engine is rather straightforward:

random_device rnd;cout << "Entropy: " << rnd.entropy() << endl;cout << "Min value: " << rnd.min()<< ", Max value: " << rnd.max() << endl;cout << "Random number: " << rnd() << endl;

A possible output of this program could be as follows:

Entropy: 32Min value: 0, Max value: 4294967295Random number: 3590924439

A random_device is usually slower than a pseudo-random number engine. Therefore, if you need to generate a lot of random numbers, I recommend to use a pseudo-random number engine, and to use a random_device to generate a seed for the pseudo-random number engine. This is demonstrated in the section “Generating Random Numbers.”

Next to the random_device engine, there are three pseudo-random number engines:

- The linear congruential engine requires a minimal amount of memory to store its state. The state is a single integer containing the last generated random number or the initial seed if no random number has been generated yet. The period of this engine depends on an algorithmic parameter and can be up to 264 but is usually less. For this reason, the linear congruential engine should not be used when you need a high-quality random number sequence.

- Of the three pseudo-random number engines, the Mersenne twister generates the highest quality of random numbers. The period of a Mersenne twister depends on an algorithmic parameter but is much bigger than the period of a linear congruential engine. The memory required to store the state of a Mersenne twister also depends on its parameters but is much larger than the single integer state of the linear congruential engine. For example, the predefined Mersenne twister

mt19937has a period of 219937−1, while the state contains 625 integers or 2.5 kilobytes. It is also one of the fastest engines. - The subtract with carry engine requires a state of around 100 bytes; however, the quality of the generated random numbers is less than that of the numbers generated by the Mersenne twister, and it is also slower than the Mersenne twister.

The mathematical details of the engines and of the quality of random numbers fall outside the scope of this book. If you want to know more about these topics, you can consult a reference from the “Random Numbers” section in Appendix B.

The random_device engine is easy to use and doesn’t require any parameters. However, creating an instance of one of the three pseudo-random number generators requires you to specify a number of mathematical parameters, which can be complicated. The selection of parameters greatly influences the quality of the generated random numbers. For example, the definition of the mersenne_twister_engine class looks like this:

template<class UIntType, size_t w, size_t n, size_t m, size_t r,UIntType a, size_t u, UIntType d, size_t s,UIntType b, size_t t, UIntType c, size_t l, UIntType f>class mersenne_twister_engine {...}

It requires 14 parameters. The linear_congruential_engine and the subtract_with_carry_engine classes also require a number of such mathematical parameters. For this reason, the standard defines a couple of predefined engines. One example is the mt19937 Mersenne twister, which is defined as follows:

usingmt19937= mersenne_twister_engine<uint_fast32_t, 32, 624, 397, 31,0x9908b0df, 11, 0xffffffff, 7, 0x9d2c5680, 15, 0xefc60000, 18,1812433253>;

These parameters are all magic, unless you understand the details of the Mersenne twister algorithm. In general, you do not want to modify any of these parameters unless you are a specialist in the mathematics of pseudo-random number generators. Instead, it is highly recommended to use one of the predefined type aliases such as mt19937. A complete list of predefined engines is given in a later section.

Random Number Engine Adaptors

A random number engine adaptor modifies the result of a random number engine you associate it with, which is called the base engine. This is an example of the adaptor pattern (see Chapter 29). The following three adaptor templates are defined:

template<class Engine, size_t p, size_t r> classdiscard_block_engine{...}template<class Engine, size_t w, class UIntType> classindependent_bits_engine{...}template<class Engine, size_t k> classshuffle_order_engine{...}

The discard_block_engine adaptor generates random numbers by discarding some of the values generated by its base engine. It requires three parameters: the engine to adapt, the block size p, and the used block size r. The base engine is used to generate p random numbers. The adaptor then discards p-r of those numbers and returns the remaining r numbers.

The independent_bits_engine adaptor generates random numbers with a given number of bits w by combining several random numbers generated by the base engine.

The shuffle_order_engine adaptor generates the same random numbers that are generated by the base engine, but delivers them in a different order.

How these adaptors internally work depends on mathematics and falls outside the scope of this book.

A number of predefined engine adaptors are available. The next section gives an overview of the predefined engines and engine adaptors.

Predefined Engines and Engine Adaptors

As mentioned earlier, it is not recommended to specify your own parameters for pseudo-random number engines and engine adaptors, but instead to use one of the standard ones. C++ defines the following predefined engines and engine adaptors, all in the <random> header file. They all have complicated template arguments, but it is not necessary to understand those arguments to be able to use them.

| NAME | TEMPLATE |

minstd_rand0 |

linear_congruential_engine |

minstd_rand |

linear_congruential_engine |

mt19937 |

mersenne_twister_engine |

mt19937_64 |

mersenne_twister_engine |

ranlux24_base |

subtract_with_carry_engine |

ranlux48_base |

subtract_with_carry_engine |

ranlux24 |

discard_block_engine |

ranlux48 |

discard_block_engine |

knuth_b |

shuffle_order_engine |

default_random_engine |

implementation-defined |

The default_random_engine is compiler dependent.

The following section gives an example of how to use these predefined engines.

Generating Random Numbers

Before you can generate any random number, you first need to create an instance of an engine. If you use a software-based engine, you also need to define a distribution. A distribution is a mathematical formula describing how numbers are distributed within a certain range. The recommended way to create an engine is to use one of the predefined engines discussed in the previous section.

The following example uses the predefined engine called mt19937, using a Mersenne twister engine. This is a software-based generator. Just as with the old rand() generator, a software-based engine should be initialized with a seed. The seed used with srand() was often the current time. In modern C++, it’s recommended to use a random_device to generate a seed, and to use a time-based seed as a fallback in case the random_device does not have any entropy.

random_device seeder;const auto seed = seeder.entropy() ? seeder() : time(nullptr);mt19937 eng(static_cast<mt19937::result_type>(seed));

Next, a distribution is defined. This example uses a uniform integer distribution, for the range 1 to 99. Distributions are explained in detail in the next section, but the uniform distribution is easy enough to use for this example:

uniform_int_distribution<int> dist(1, 99);Once the engine and distribution are defined, random numbers can be generated by calling the function call operator of the distribution, and passing the engine as argument. For this example, this is written as dist(eng):

cout << dist(eng) << endl;As you can see, to generate a random number using a software-based engine, you always need to specify the engine and distribution. The std::bind() utility, introduced in Chapter 18 and defined in the <functional> header file, can be used to remove the need to specify both the distribution and the engine when generating a random number. The following example uses the same mt19937 engine and uniform distribution as the previous example. It then defines gen() by using std::bind() to bind eng to the first parameter for dist(). This way, you can call gen() without any argument to generate a new random number. The example then demonstrates the use of gen() in combination with the generate() algorithm to fill a vector of ten elements with random numbers. The generate() algorithm is discussed in Chapter 18 and is defined in <algorithm>.

random_device seeder;const auto seed = seeder.entropy() ? seeder() : time(nullptr);mt19937 eng(static_cast<mt19937::result_type>(seed));uniform_int_distribution<int> dist(1, 99);auto gen = std::bind(dist, eng);vector<int> vec(10);generate(begin(vec), end(vec), gen);for (auto i : vec) { cout << i << " "; }

Even though you don’t know the exact type of gen(), it’s still possible to pass gen() to another function that wants to use that generator. You have two options: use a parameter of type std::function<int()>, or use a function template. The previous example can be adapted to generate random numbers in a function called fillVector(). Here is an implementation using std::function:

void fillVector(vector<int>& vec, const std::function<int()>& generator){generate(begin(vec), end(vec), generator);}

and here is a function template version:

template<typename T>void fillVector(vector<int>& vec, const T& generator){generate(begin(vec), end(vec), generator);}

This function is used as follows:

random_device seeder;const auto seed = seeder.entropy() ? seeder() : time(nullptr);mt19937 eng(static_cast<mt19937::result_type>(seed));uniform_int_distribution<int> dist(1, 99);auto gen = std::bind(dist, eng);vector<int> vec(10);fillVector(vec, gen);for (auto i : vec) { cout << i << " "; }

Random Number Distributions

A distribution is a mathematical formula describing how numbers are distributed within a certain range. The random number generator library comes with the following distributions that can be used with pseudo-random number engines to define the distribution of the generated random numbers. It’s a compacted representation. The first line of each distribution is the class name and class template parameters, if any. The next lines are a constructor for the distribution. Only one constructor for each distribution is shown to give you an idea of the class. Consult a Standard Library Reference, see Appendix B, for a detailed list of all constructors and methods of each distribution.

Available uniform distributions:

template<class IntType = int> class uniform_int_distributionuniform_int_distribution(IntType a = 0,IntType b = numeric_limits<IntType>::max());template<class RealType = double> class uniform_real_distributionuniform_real_distribution(RealType a = 0.0, RealType b = 1.0);

Available Bernoulli distributions:

class bernoulli_distributionbernoulli_distribution(double p = 0.5);template<class IntType = int> class binomial_distributionbinomial_distribution(IntType t = 1, double p = 0.5);template<class IntType = int> class geometric_distributiongeometric_distribution(double p = 0.5);template<class IntType = int> class negative_binomial_distributionnegative_binomial_distribution(IntType k = 1, double p = 0.5);

Available Poisson distributions:

template<class IntType = int> class poisson_distributionpoisson_distribution(double mean = 1.0);template<class RealType = double> class exponential_distributionexponential_distribution(RealType lambda = 1.0);template<class RealType = double> class gamma_distributiongamma_distribution(RealType alpha = 1.0, RealType beta = 1.0);template<class RealType = double> class weibull_distributionweibull_distribution(RealType a = 1.0, RealType b = 1.0);template<class RealType = double> class extreme_value_distributionextreme_value_distribution(RealType a = 0.0, RealType b = 1.0);

Available normal distributions:

template<class RealType = double> class normal_distributionnormal_distribution(RealType mean = 0.0, RealType stddev = 1.0);template<class RealType = double> class lognormal_distributionlognormal_distribution(RealType m = 0.0, RealType s = 1.0);template<class RealType = double> class chi_squared_distributionchi_squared_distribution(RealType n = 1);template<class RealType = double> class cauchy_distributioncauchy_distribution(RealType a = 0.0, RealType b = 1.0);template<class RealType = double> class fisher_f_distributionfisher_f_distribution(RealType m = 1, RealType n = 1);template<class RealType = double> class student_t_distributionstudent_t_distribution(RealType n = 1);

Available sampling distributions:

template<class IntType = int> class discrete_distributiondiscrete_distribution(initializer_list<double> wl);template<class RealType = double> class piecewise_constant_distributiontemplate<class UnaryOperation>piecewise_constant_distribution(initializer_list<RealType> bl,UnaryOperation fw);template<class RealType = double> class piecewise_linear_distributiontemplate<class UnaryOperation>piecewise_linear_distribution(initializer_list<RealType> bl,UnaryOperation fw);

Each distribution requires a set of parameters. Explaining all these mathematical parameters is outside the scope of this book, but the rest of this section includes a couple of examples to explain the impact of a distribution on the generated random numbers.

Distributions are easiest to understand when you look at a graphical representation of them. For example, the following code generates one million random numbers between 1 and 99, and counts how many times a certain number is randomly chosen. The counters are stored in a map where the key is a number between 1 and 99, and the value associated with a key is the number of times that that key has been selected randomly. After the loop, the results are written to a CSV (comma-separated values) file, which can be opened in a spreadsheet application.

const unsigned int kStart = 1;const unsigned int kEnd = 99;const unsigned int kIterations = 1'000'000;// Uniform Mersenne Twisterrandom_device seeder;const auto seed = seeder.entropy() ? seeder() : time(nullptr);mt19937 eng(static_cast<mt19937::result_type>(seed));uniform_int_distribution<int> dist(kStart, kEnd);auto gen = bind(dist, eng);map<int, int> m;for (unsigned int i = 0; i < kIterations; ++i) {int rnd = gen();// Search map for a key = rnd. If found, add 1 to the value associated// with that key. If not found, add the key to the map with value 1.++(m[rnd]);}// Write to a CSV fileofstream of("res.csv");for (unsigned int i = kStart; i <= kEnd; ++i) {of << i << "," << m[i] << endl;}

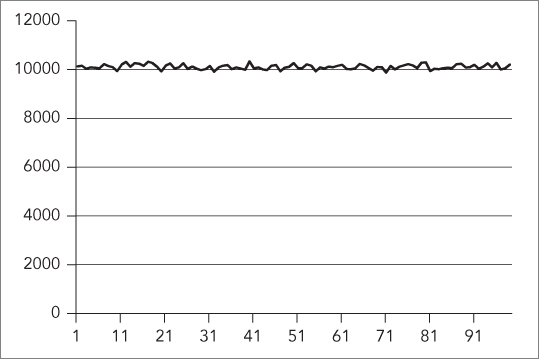

The resulting data can then be used to generate a graphical representation. The graph of the preceding uniform Mersenne twister is shown in Figure 20-1.

The horizontal axis represents the range in which random numbers are generated. The graph clearly shows that all numbers in the range 1 to 99 are randomly chosen around 10,000 times, and that the distribution of the generated random numbers is uniform across the entire range.

The example can be modified to generate random numbers according to a normal distribution instead of a uniform distribution. Only two small changes are required. First, you need to modify the creation of the distribution as follows:

normal_distribution<double> dist(50, 10);Because normal distributions use doubles instead of integers, you also need to modify the call to gen():

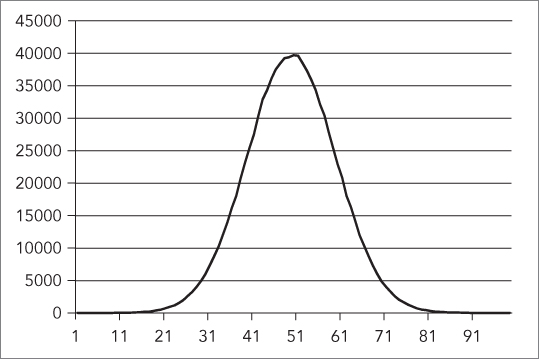

int rnd = static_cast<int>(gen());Figure 20-2 shows a graphical representation of the random numbers generated according to this normal distribution.

The graph clearly shows that most of the generated random numbers are around the center of the range. In this example, the value 50 is randomly chosen around 40,000 times, while values like 20 and 80 are chosen only around 500 times.

OPTIONAL

OPTIONAL

std::optional, defined in <optional>, holds a value of a specific type, or nothing. It can be used for parameters of a function if you want to allow for values to be optional. It is also often used as a return type from a function if the function can either return something or not. This removes the need to return “special” values from functions such as nullptr, end(), -1, EOF, and so on. It also removes the need to write the function returning a Boolean while storing the actual value in a reference output parameter, such as bool getData(T& dataOut).

Here is an example of a function returning an optional:

optional<int> getData(bool giveIt){if (giveIt) {return 42;}return nullopt; // or simply return {};}

You can call this function as follows:

auto data1 = getData(true);auto data2 = getData(false);

To determine whether or not an optional has a value, use the has_value() method, or simply use the optional in an if statement:

cout << "data1.has_value = " << data1.has_value() << endl;if (data2) {cout << "data2 has a value." << endl;}

If an optional has a value, you can retrieve it with value(), or with the dereferencing operator:

cout << "data1.value = " << data1.value() << endl;cout << "data1.value = " << *data1 << endl;

If you call value() on an empty optional, a bad_optional_access exception is thrown.

value_or() can be used to return either the value of an optional, or another value when the optional is empty:

cout << "data2.value = " << data2.value_or(0) << endl;Note that you cannot store a reference in an optional, so optional<T&> does not work. Instead, you can use optional<T*>, optional<reference_wrapper<T>>, or optional<reference_wrapper<const T>>. Remember from Chapter 17 that you can use std::ref() or cref() to create an std::reference_wrapper<T> or a reference_wrapper<const T> respectively.

VARIANT

VARIANT

std::variant, defined in <variant>, can hold a single value of one of a given set of types. When you define a variant, you have to specify the types it can potentially contain. For example, the following code defines a variant that can contain an integer, a string, or a floating point value, one at a time:

variant<int, string, float> v;This default-constructed variant contains a default-constructed value of its first type, int in this case. If you want to be able to default construct a variant, you have to make sure that the first type of the variant is default constructible. For example, the following does not compile because Foo is not default constructible.

class Foo { public: Foo() = delete; Foo(int) {} };class Bar { public: Bar() = delete; Bar(int) {} };int main(){variant<Foo, Bar> v;}

In fact, neither Foo nor Bar are default constructible. If you still want to be able to default construct such a variant, then you can use std::monostate, an empty alternative, as first type of the variant:

variant<monostate, Foo, Bar> v;You can use the assignment operator to store something in a variant:

variant<int, string, float> v;v = 12;v = 12.5f;v = "An std::string"s;

A variant can only contain one value at any given time. So, with these three lines of code, first the integer 12 is stored in the variant, then the variant is modified to contain a single floating-point value, and lastly, the variant is modified again to contain a single string value.

You can use the index() method to query the index of the value’s type that is currently stored in the variant. The std::holds_alternative() function template can be used to figure out whether or not a variant currently contains a value of a certain type:

cout << "Type index: " << v.index() << endl;cout << "Contains an int: " << holds_alternative<int>(v) << endl;

The output is as follows:

Type index: 1Contains an int: 0

Use std::get<index>() or std::get<T>() to retrieve the value from a variant. These functions throw a bad_variant_access exception if you are using the index of a type, or a type, that does not match the current value in the variant:

cout << std::get<string>(v) << endl;try {cout << std::get<0>(v) << endl;} catch (const bad_variant_access& ex) {cout << "Exception: " << ex.what() << endl;}

This is the output:

An std::stringException: bad variant access

To avoid exceptions, use the std::get_if<index>() or std::get_if<T>() helper functions. These functions accept a pointer to a variant, and return a pointer to the requested value, or nullptr on error:

string* theString = std::get_if<string>(&v);int* theInt = std::get_if<int>(&v);cout << "retrieved string: " << (theString ? *theString : "null") << endl;cout << "retrieved int: " << (theInt ? *theInt : 0) << endl;

Here is the output:

retrieved string: An std::stringretrieved int: 0

There is an std::visit() helper function that you can use to apply the visitor pattern to a variant. Suppose you have the following class that defines a number of overloaded function call operators, one for each possible type in the variant:

class MyVisitor{public:void operator()(int i) { cout << "int " << i << endl; }void operator()(const string& s) { cout << "string " << s << endl; }void operator()(float f) { cout << "float " << f << endl; }};

You can use this with std::visit() as follows.

visit(MyVisitor(), v);The result is that the appropriate overloaded function call operator is called based on the current value stored in the variant. The output for this example is:

string An std::stringAs with optional, you cannot store references in a variant. You can either store pointers, or store instances of reference_wrapper<T> or reference_wrapper<const T>.

ANY

ANY

std::any, defined in <any>, is a class that can contain a single value of any type. Once it is constructed, you can ask an any instance whether or not it contains a value, and what the type of the contained value is. To get access to the contained value, you need to use any_cast(), which throws an exception of type bad_any_cast in case of failure. Here is an example:

any empty;any anInt(3);any aString("An std::string."s);cout << "empty.has_value = " << empty.has_value() << endl;cout << "anInt.has_value = " << anInt.has_value() << endl << endl;cout << "anInt wrapped type = " << anInt.type().name() << endl;cout << "aString wrapped type = " << aString.type().name() << endl << endl;int theInt = any_cast<int>(anInt);cout << theInt << endl;try {int test = any_cast<int>(aString);cout << test << endl;} catch (const bad_any_cast& ex) {cout << "Exception: " << ex.what() << endl;}

The output is as follows. Note that the wrapped type of aString is compiler dependent.

empty.has_value = 0anInt.has_value = 1anInt wrapped type = intaString wrapped type = class std::basic_string<char,struct std::char_traits<char>,class std::allocator<char> >3Exception: Bad any_cast

You can assign a new value to an any instance, and even assign a new value of a different type:

any something(3); // Now it contains an integer.something = "An std::string"s; // Now the same instance contains a string.

Instances of any can be stored in Standard Library containers. This allows you to have heterogeneous data in a single container. The only downside is that you have to perform explicit any_casts to retrieve specific values, as in this example:

vector<any> v;v.push_back(any(42));v.push_back(any("An std::string"s));cout << any_cast<string>(v[1]) << endl;

As with optional and variant, you cannot store references in an any instance. You can either store pointers, or store instances of reference_wrapper<T> or reference_wrapper<const T>.

TUPLES

The std::pair class, defined in <utility> and introduced in Chapter 17, can store exactly two values, each with a specific type. The type of each value should be known at compile time. Here is a short example:

pair<int, string> p1(16, "Hello World");pair<bool, float> p2(true, 0.123f);cout << "p1 = (" << p1.first << ", " << p1.second << ")" << endl;cout << "p2 = (" << p2.first << ", " << p2.second << ")" << endl;

The output is as follows:

p1 = (16, Hello World)p2 = (1, 0.123)

An std::tuple, defined in <tuple>, is a generalization of a pair. It allows you to store any number of values, each with its own specific type. Just like a pair, a tuple has a fixed size and fixed value types, which are determined at compile time.

A tuple can be created with a tuple constructor, specifying both the template types and the actual values. For example, the following code creates a tuple where the first element is an integer, the second element a string, and the last element a Boolean:

using MyTuple = tuple<int, string, bool>;MyTuple t1(16, "Test", true);

std::get<i>() is used to get the ith element from a tuple, where i is a 0-based index; that is, <0> is the first element of the tuple, <1> is the second element of the tuple, and so on. The value returned has the correct type for that index in the tuple:

cout << "t1 = (" << get<0>(t1) << ", " << get<1>(t1)<< ", " << get<2>(t1) << ")" << endl;// Outputs: t1 = (16, Test, 1)

You can check that get<

i

>() returns the correct type by using typeid(), from the <typeinfo> header. The output of the following code says that the value returned by get<1>(t1) is indeed an std::string:

cout << "Type of get<1>(t1) = " << typeid(get<1>(t1)).name() << endl;// Outputs: Type of get<1>(t1) = class std::basic_string<char,// struct std::char_traits<char>,class std::allocator<char> >

You can also retrieve an element from a tuple based on its type with std::get<T>(), where T is the type of the element you want to retrieve instead of the index. The compiler generates an error if the tuple has several elements with the requested type. For example, you can retrieve the string element from t1 as follows:

cout << "String = " << get<string>(t1) << endl;// Outputs: String = Test

Iterating over the values of a tuple is unfortunately not straightforward. You cannot write a simple loop and call something like get<i>(mytuple) because the value of i must be known at compile time. A possible solution is to use template metaprogramming, which is discussed in detail in Chapter 22, together with an example on how to print tuple values.

The size of a tuple can be queried with the std::tuple_size template. Note that tuple_size requires you to specify the type of the tuple (MyTuple in this case) and not an actual tuple instance like t1:

cout << "Tuple Size = " << tuple_size<MyTuple>::value << endl;// Outputs: Tuple Size = 3

If you don’t know the exact tuple type, you can always use decltype() as follows:

cout << "Tuple Size = " << tuple_size<decltype(t1)>::value << endl;// Outputs: Tuple Size = 3

With C++17’s template argument deduction for constructors, you can omit the template type parameters when constructing a

With C++17’s template argument deduction for constructors, you can omit the template type parameters when constructing a tuple, and let the compiler deduce them automatically based on the type of arguments passed to the constructor. For example, the following defines the same t1

tuple consisting of an integer, a string, and a Boolean. Note that you now have to specify "Test"s to make sure it’s an std::string.

std::tuple t1(16, "Test"s, true);Because of the automatic deduction of types, you cannot use & to specify a reference. If you want to use template argument deduction for constructors to generate a tuple containing a reference or a constant reference, then you need to use ref() or cref(), respectively, as is demonstrated in the following example. The ref() and cref() utility functions are defined in the <functional> header file. For example, the following construction results in a tuple of type tuple<int, double&, const double&, string&>:

double d = 3.14;string str1 = "Test";std::tuple t2(16, ref(d), cref(d), ref(str1));

To test the double reference in the t2 tuple, the following code first writes the value of the double variable to the console. The call to get<1>(t2) returns a reference to d because ref(d) was used for the second (index 1) tuple element. The second line changes the value of the variable referenced, and the last line shows that the value of d is indeed changed through the reference stored in the tuple. Note that the third line fails to compile because cref(d) was used for the third tuple element, that is, it is a constant reference to d.

cout << "d = " << d << endl;get<1>(t2) *= 2;//get<2>(t2) *= 2; // ERROR because of cref()cout << "d = " << d << endl;// Outputs: d = 3.14// d = 6.28

Without C++17’s template argument deduction for constructors, you can use the std::make_tuple() utility function to create a tuple. This helper function template also allows you to create a tuple by only specifying the actual values. The types are deduced automatically at compile time. For example:

auto t2 = std::make_tuple(16, ref(d), cref(d), ref(str1));Decompose Tuples

There are two ways in which you can decompose a tuple into its individual elements: structured bindings (C++17) and std::tie().

Structured Bindings

Structured Bindings

Structured bindings, introduced in C++17, make it very easy to decompose a tuple into separate variables. For example, the following code defines a tuple consisting of an integer, a string, and a Boolean value, and then uses a structured binding to decompose it into three distinct variables:

tuple t1(16, "Test"s, true);auto[i, str, b] = t1;cout << "Decomposed: i = "<< i << ", str = \"" << str << "\", b = " << b << endl;

With structured bindings, you cannot ignore specific elements while decomposing. If your tuple has three elements, then your structured binding needs three variables. If you want to ignore elements, then you have to use tie(), explained next.

tie

If you want to decompose a tuple without structured bindings, you can use the std::tie() utility function, which generates a tuple of references. The following example first creates a tuple consisting of an integer, a string, and a Boolean value. It then creates three variables—an integer, a string, and a Boolean—and writes the values of those variables to the console. The tie(i, str, b) call creates a tuple containing a reference to i, a reference to str, and a reference to b. The assignment operator is used to assign tuple t1 to the result of tie(). Because the result of tie() is a tuple of references, the assignment actually changes the values in the three separate variables, as is shown by the output of the values after the assignment.

tuple<int, string, bool> t1(16, "Test", true);int i = 0;string str;bool b = false;cout << "Before: i = " << i << ", str = \"" << str << "\", b = " << b << endl;tie(i, str, b) = t1;cout << "After: i = " << i << ", str = \"" << str << "\", b = " << b << endl;

The result is as follows:

Before: i = 0, str = "", b = 0After: i = 16, str = "Test", b = 1

With tie() you can ignore certain elements that you do not want to be decomposed. Instead of a variable name for the decomposed value, you use the special std::ignore value. Here is the previous example, but now the string element of the tuple is ignored in the call to tie():

tuple<int, string, bool> t1(16, "Test", true);int i = 0;bool b = false;cout << "Before: i = " << i << ", b = " << b << endl;tie(i, std::ignore, b) = t1;cout << "After: i = " << i << ", b = " << b << endl;

Here is the new output:

Before: i = 0, b = 0After: i = 16, b = 1

Concatenation

You can use std::tuple_cat() to concatenate two tuples into one tuple. In the following example, the type of t3 is tuple<int, string, bool, double, string>:

tuple<int, string, bool> t1(16, "Test", true);tuple<double, string> t2(3.14, "string 2");auto t3 = tuple_cat(t1, t2);

Comparisons

Tuples also support the following comparison operators: ==, !=, <, >, <=, and >=. For the comparison operators to work, the element types stored in the tuple should support them as well. Here is an example:

tuple<int, string> t1(123, "def");tuple<int, string> t2(123, "abc");if (t1 < t2) {cout << "t1 < t2" << endl;} else {cout << "t1 >= t2" << endl;}

The output is as follows:

t1 >= t2Tuple comparisons can be used to easily implement lexicographical comparison operators for custom types that have several data members. For example, suppose you have a simple structure with three data members:1

struct Foo{int mInt;string mStr;bool mBool;};

Implementing a correct operator< for Foo is not trivial! However, using std::tie() and tuple comparisons, this becomes a simple one-liner:

bool operator<(const Foo& f1, const Foo& f2){return tie(f1.mInt, f1.mStr, f1.mBool) <tie(f2.mInt, f2.mStr, f2.mBool);}

Here is an example of its use:

Foo f1{ 42, "Hello", 0 };Foo f2{ 32, "World", 0 };cout << (f1 < f2) << endl;cout << (f2 < f1) << endl;

make_from_tuple

make_from_tuple

std::make_from_tuple() constructs an object of a given type T, passing the elements of a given tuple as arguments to the constructor of T. For example, suppose you have the following class:

class Foo{public:Foo(string str, int i) : mStr(str), mInt(i) {}private:string mStr;int mInt;};

You can use make_from_tuple() as follows:

auto myTuple = make_tuple("Hello world.", 42);auto foo = make_from_tuple<Foo>(myTuple);

The argument given to make_from_tuple() does not have to be a tuple, but it has to be something that supports std::get<>() and std::tuple_size. Both std::array and std::pair satisfy these requirements as well.

This function is not that practical for everyday use, but it comes in handy when writing very generic code using templates and template metaprogramming.

apply

apply

std::apply() calls a given callable (function, lambda expression, function object, and so on), passing the elements of a given tuple as arguments. Here is an example:

int add(int a, int b) { return a + b; }...cout << apply(add, std::make_tuple(39, 3)) << endl;

As with make_from_tuple(), this function is also meant more for use with generic code using templates and template metaprogramming, than for everyday use.

FILESYSTEM SUPPORT LIBRARY

FILESYSTEM SUPPORT LIBRARY

C++17 introduces a filesystem support library. Everything is defined in the <filesystem> header, and lives in the std::filesystem namespace. It allows you to write portable code to work with the filesystem. You can use it for querying whether something is a directory or a file, iterating over the contents of a directory, manipulating paths, and retrieving information about files such as their size, extension, creation time, and so on. The two most important parts of the library—paths and directory entries—are introduced in the next sections.

Path

The basic component of the library is a path. A path can be an absolute or a relative path, and can include a filename or not. For example, the following code defines a couple of paths. Note the use of a raw string literal to avoid having to escape the backslashes.

path p1(LR"(D:\Foo\Bar)");path p2(L"D:/Foo/Bar");path p3(L"D:/Foo/Bar/MyFile.txt");path p4(LR"(..\SomeFolder)");path p5(L"/usr/lib/X11");

When a path is converted to a string (for example by using the c_str() method), or inserted into a stream, it is converted to the native format of the system on which the code is running. For example:

path p1(LR"(D:\Foo\Bar)");path p2(L"D:/Foo/Bar");cout << p1 << endl;cout << p2 << endl;

The output is as follows:

D:\Foo\BarD:\Foo\Bar

You can append a component to a path with the append() method, or with operator/=. A path separator is automatically included. For example:

path p(L"D:\\Foo");p.append("Bar");p /= "Bar";cout << p << endl;

The output is D:\Foo\Bar\Bar.

You can use concat(), or operator+=, to concatenate a string to an existing path. This does not add any path separator! For example:

path p(L"D:\\Foo");p.concat("Bar");p += "Bar";cout << p << endl;

The output now is D:\FooBarBar.

A path supports iterators to iterate over its different components. Here is an example:

path p(LR"(C:\Foo\Bar)");for (const auto& component : p) {cout << component << endl;}

The output is as follows:

C:\FooBar

The path interface supports operations such as remove_filename(), replace_filename(), replace_extension(), root_name(), parent_path(), extension(), has_extension(), is_absolute(), is_relative(), and more. Consult a Standard Library reference, see Appendix B, for a full list of all available functionality.

Directory Entry

A path just represents a directory or a file on a filesystem. A path may refer to a non-existing directory or file. If you want to query an actual directory or file on the filesystem, you need to construct a directory_entry from a path. This construction can fail if the given directory or file does not exist. The directory_entry interface supports operations like is_directory(), is_regular_file(), is_socket(), is_symlink(), file_size(), last_write_time(), and others.

The following example constructs a directory_entry from a path to query the size of a file:

path myPath(L"c:/windows/win.ini");directory_entry dirEntry(myPath);if (dirEntry.exists() && dirEntry.is_regular_file()) {cout << "File size: " << dirEntry.file_size() << endl;}

Helper Functions

An entire collection of helper functions is available. For example, you can use copy() to copy files or directories, create_directory() to create a new directory on the filesystem, exists() to query whether or not a given directory or file exists, file_size() to get the size of a file, last_write_time() to get the time the file was last modified, remove() to delete a file, temp_directory_path() to get a directory suitable for storing temporary files, space() to query the available space on a filesystem, and more. Consult a Standard Library reference, see Appendix B, for a full list.

The following example prints out the capacity of a filesystem and how much space is still free:

space_info s = space("c:\\");cout << "Capacity: " << s.capacity << endl;cout << "Free: " << s.free << endl;

You can find more examples of these helper functions in the following section on directory iteration.

Directory Iteration

If you want to recursively iterate over all files and subdirectories in a given directory, you can use the recursive_directory_iterator as follows:

void processPath(const path& p){if (!exists(p)) {return;}auto begin = recursive_directory_iterator(p);auto end = recursive_directory_iterator();for (auto iter = begin; iter != end; ++iter) {const string spacer(iter.depth() * 2, ' ');auto& entry = *iter;if (is_regular_file(entry)) {cout << spacer << "File: " << entry;cout << " (" << file_size(entry) << " bytes)" << endl;} else if (is_directory(entry)) {std::cout << spacer << "Dir: " << entry << endl;}}}

This function can be called as follows:

path p(LR"(D:\Foo\Bar)");processPath(p);

You can also use a directory_iterator to iterate over the contents of a directory and implement the recursion yourself. Here is an example that does the same thing as the previous example but using a directory_iterator instead of a recursive_directory_iterator:

void processPath(const path& p, size_t level = 0){if (!exists(p)) {return;}const string spacer(level * 2, ' ');if (is_regular_file(p)) {cout << spacer << "File: " << p;cout << " (" << file_size(p) << " bytes)" << endl;} else if (is_directory(p)) {std::cout << spacer << "Dir: " << p << endl;for (auto& entry : directory_iterator(p)) {processPath(entry, level + 1);}}}

SUMMARY

This chapter gave an overview of additional functionality provided by the C++ standard that did not fit naturally in other chapters. You learned how to use the ratio template to define compile-time rational numbers; the chrono library; the random number generation library; and the optional, variant, and any data types. You also learned about tuples, which are a generalization of pairs. The chapter finished with an introduction to the filesystem support library.

This chapter concludes Part 3 of the book. The next part discusses some more advanced topics and starts with a chapter showing you how to customize and extend the functionality provided by the C++ Standard Library.