For many years, C++ has served as the de facto language for writing fast, powerful, and enterprise-class object-oriented programs. As popular as C++ has become, the language is surprisingly difficult to grasp in full. There are simple, but powerful, techniques that professional C++ programmers use that don’t show up in traditional texts, and there are useful parts of C++ that remain a mystery even to experienced C++ programmers.

Too often, programming books focus on the syntax of the language instead of its real-world use. The typical C++ text introduces a major part of the language in each chapter, explaining the syntax and providing an example. Professional C++ does not follow this pattern. Instead of giving you just the nuts and bolts of the language with little practical context, this book will teach you how to use C++ in the real world. It will show you the little-known features that will make your life easier, and the programming techniques that separate novices from professional programmers.

Even if you have used the language for years, you might still be unfamiliar with the more-advanced features of C++, or you might not be using the full capabilities of the language. Perhaps you write competent C++ code, but would like to learn more about design and good programming style in C++. Or maybe you’re relatively new to C++, but want to learn the “right” way to program from the start. This book will meet those needs and bring your C++ skills to the professional level.

Because this book focuses on advancing from basic or intermediate knowledge of C++ to becoming a professional C++ programmer, it assumes that you have some knowledge of the language. Chapter 1 covers the basics of C++ as a refresher, but it is not a substitute for actual training and use of the language. If you are just starting with C++, but you have significant experience in another programming language such as C, Java, or C#, you should be able to pick up most of what you need from Chapter 1.

In any case, you should have a solid foundation in programming fundamentals. You should know about loops, functions, and variables. You should know how to structure a program, and you should be familiar with fundamental techniques such as recursion. You should have some knowledge of common data structures such as queues, and useful algorithms such as sorting and searching. You don’t need to know about object-oriented programming just yet—that is covered in Chapter 5.

You will also need to be familiar with the compiler you will be using to develop your code. Two compilers, Microsoft Visual C++ and GCC, are introduced later in this introduction. For other compilers, refer to the documentation that came with your compiler.

Professional C++ uses an approach to C++ programming that will both increase the quality of your code and improve your programming efficiency. You will find discussions on new C++17 features throughout this fourth edition. These features are not just isolated to a few chapters or sections; instead, examples have been updated to use new features when appropriate.

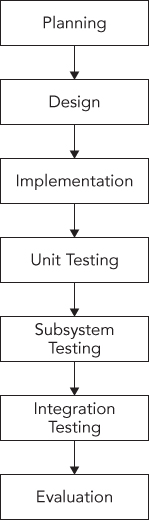

Professional C++ teaches you more than just the syntax and language features of C++. It also emphasizes programming methodologies, reusable design patterns, and good programming style. The Professional C++ methodology incorporates the entire software development process, from designing and writing code, to debugging, and working in groups. This approach will enable you to master the C++ language and its idiosyncrasies, as well as take advantage of its powerful capabilities for large-scale software development.

Imagine users who have learned all of the syntax of C++ without seeing a single example of its use. They know just enough to be dangerous! Without examples, they might assume that all code should go in the main() function of the program, or that all variables should be global—practices that are generally not considered hallmarks of good programming.

Professional C++ programmers understand the correct way to use the language, in addition to the syntax. They recognize the importance of good design, the theories of object-oriented programming, and the best ways to use existing libraries. They have also developed an arsenal of useful code and reusable ideas.

By reading and understanding this book, you will become a professional C++ programmer. You will expand your knowledge of C++ to cover lesser-known and often misunderstood language features. You will gain an appreciation for object-oriented design, and acquire top-notch debugging skills. Perhaps most important, you will finish this book armed with a wealth of reusable ideas that you can actually apply to your daily work.

There are many good reasons to make the effort to be a professional C++ programmer, as opposed to a programmer who knows C++. Understanding the true workings of the language will improve the quality of your code. Learning about different programming methodologies and processes will help you to work better with your team. Discovering reusable libraries and common design patterns will improve your daily efficiency and help you stop reinventing the wheel. All of these lessons will make you a better programmer and a more valuable employee. While this book can’t guarantee you a promotion, it certainly won’t hurt.

This book is made up of five parts.

Part I, “Introduction to Professional C++,” begins with a crash course in C++ basics to ensure a foundation of C++ knowledge. Following the crash course, Part I goes deeper into working with strings and string views because strings are used extensively in most examples throughout the book. The last chapter of Part I explores how to write readable C++ code.

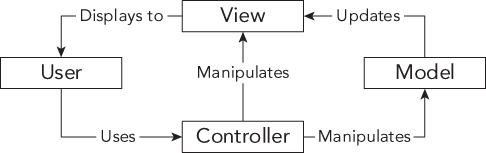

Part II, “Professional C++ Software Design,” discusses C++ design methodologies. You will read about the importance of design, the object-oriented methodology, and the importance of code reuse.

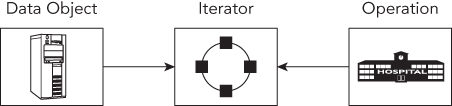

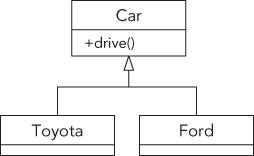

Part III, “C++ Coding the Professional Way,” provides a technical tour of C++ from the professional point of view. You will read about the best ways to manage memory in C++, how to create reusable classes, and how to leverage important language features such as inheritance. You will also learn about the unusual and quirky parts of the language, techniques for input and output, error handling, string localization, and how to work with regular expressions. You will read about how to implement operator overloading, and how to write templates. This part also explains the C++ Standard Library, including containers, iterators, and algorithms. You will also read about some additional libraries that are available in the standard, such as the libraries to work with time, random numbers, and the filesystem.

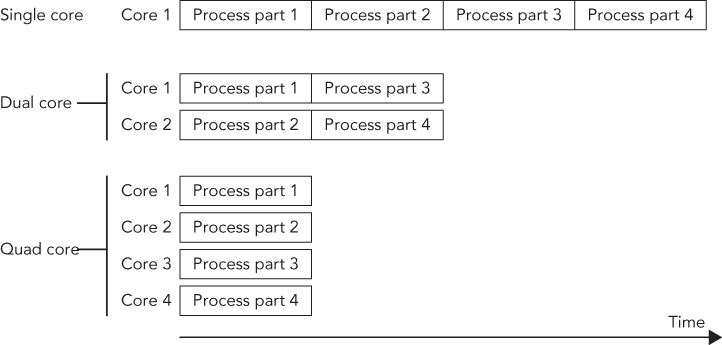

Part IV, “Mastering Advanced Features of C++,” demonstrates how you can get the most out of C++. This part of the book exposes the mysteries of C++ and describes how to use some of its more-advanced features. You will read about how to customize and extend the C++ Standard Library to your needs, advanced details on template programming, including template metaprogramming, and how to use multithreading to take advantage of multiprocessor and multicore systems.

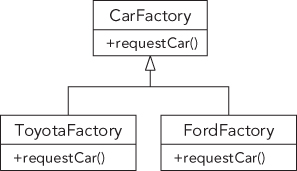

Part V, “C++ Software Engineering,” focuses on writing enterprise-quality software. You’ll read about the engineering practices being used by programming organizations today; how to write efficient C++ code; software testing concepts, such as unit testing and regression testing; techniques used to debug C++ programs; how to incorporate design techniques, frameworks, and conceptual object-oriented design patterns into your own code; and solutions for cross-language and cross-platform code.

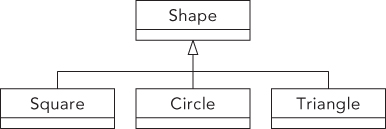

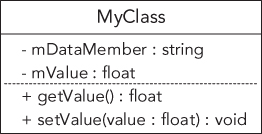

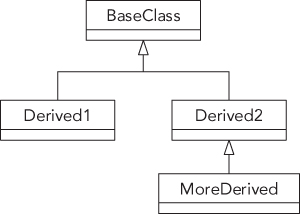

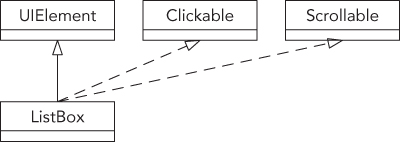

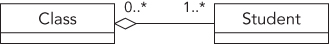

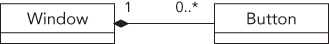

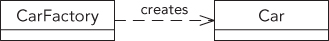

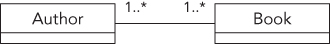

The book concludes with a useful chapter-by-chapter guide to succeeding in a C++ technical interview, an annotated bibliography, a summary of the C++ header files available in the standard, and a brief introduction to the Unified Modeling Language (UML).

This book is not a reference of every single class, method, and function available in C++. The book C++ Standard Library Quick Reference by Peter Van Weert and Marc Gregoire1 is a condensed reference to all essential data structures, algorithms, and functions provided by the C++ Standard Library. Appendix B lists a couple more references. Two excellent online references are:

You can use this reference online, or download an offline version for use when you are not connected to the Internet.

When I refer to a “Standard Library Reference” in this book, I am referring to one of these detailed C++ references.

All you need to use this book is a computer with a C++ compiler. This book focuses only on parts of C++ that have been standardized, and not on vendor-specific compiler extensions.

Note that this book includes new features introduced with the C++17 standard. At the time of this writing, some compilers are not yet fully C++17 compliant.

You can use whichever C++ compiler you like. If you don’t have a C++ compiler yet, you can download one for free. There are a lot of choices. For example, for Windows, you can download Microsoft Visual Studio 2017 Community Edition, which is free and includes Visual C++. For Linux, you can use GCC or Clang, which are also free.

The following two sections briefly explain how to use Visual C++ and GCC. Refer to the documentation that came with your compiler for more details.

First, you need to create a project. Start Visual C++ and click File ➪ New ➪ Project. In the project template tree on the left, select Visual C++ ➪ Win32 (or Windows Desktop). Then select the Win32 Console Application (or Windows Console Application) template in the list in the middle of the window. At the bottom, specify a name for the project and a location where to save it, and click OK. A wizard opens2. In this wizard, click Next, select Console Application, Empty Project, and click Finish.

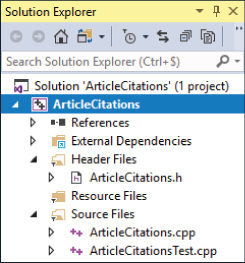

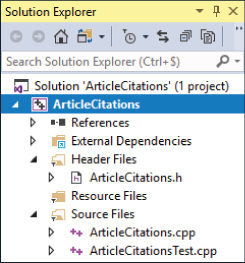

Once your new project is loaded, you can see a list of project files in the Solution Explorer. If this docking window is not visible, go to View ➪ Solution Explorer. You can add new files or existing files to a project by right-clicking the project name in the Solution Explorer and then clicking Add ➪ New Item or Add ➪ Existing Item.

Use Build ➪ Build Solution to compile your code. When it compiles without errors, you can run it with Debug ➪ Start Debugging.

If your program exits before you have a chance to view the output, use Debug ➪ Start without Debugging. This adds a pause to the end of the program so you can view the output.

At the time of this writing, Visual C++ 2017 does not yet automatically enable C++17 features. To enable C++17 features, in the Solution Explorer window, right-click your project and click Properties. In the properties window, go to Configuration Properties ➪ C/C++ ➪ Language, and set the C++ Language Standard option to “ISO C++17 Standard” or “ISO C++ Latest Draft Standard,” whichever is available in your version of Visual C++. These options are only accessible if your project contains at least one .cpp file.

Visual C++ supports so-called precompiled headers, a topic outside the scope of this book. In general, I recommend using precompiled headers if your compiler supports them. However, the source code files in the downloadable source code archive do not use precompiled headers, so you have to disable that feature for them to compile without errors. In the Solution Explorer window, right-click your project and click Properties. In the properties window, go to Configuration Properties ➪ C/C++ ➪ Precompiled Headers, and set the Precompiled Header option to “Not Using Precompiled Headers.”

Create your source code files with any text editor you prefer and save them to a directory. To compile your code, open a terminal and run the following command, specifying all your .cpp files that you want to compile:

gcc -lstdc++ -std=c++17 -o <executable_name> <source1.cpp> [source2.cpp …]The -std=c++17 option is required to tell GCC to enable C++17 support.

For example, you can compile the AirlineTicket example from Chapter 1 by changing to the directory containing the code and running the following command:

gcc –lstdc++ -std=c++17 -o AirlineTicket AirlineTicket.cpp AirlineTicketTest.cppWhen it compiles without errors, you can run it as follows:

./AirlineTicketTo help you get the most from the text and keep track of what’s happening, a number of conventions are used throughout this book.

As for styles in the text:

monkey.cpp.// Comments in code are shown like this.In code examples, new and important code is highlighted like this.Code that's less important in the present context or that has been shown before is formatted like this.

Paragraphs or sections that are specific to the C++17 standard have a little C++17 icon on the left, just as this paragraph does. C++11 and C++14 features are not marked with any icon.

Paragraphs or sections that are specific to the C++17 standard have a little C++17 icon on the left, just as this paragraph does. C++11 and C++14 features are not marked with any icon.

As you work through the examples in this book, you may choose either to type in all the code manually, or to use the source code files that accompany the book. However, I suggest you type in all the code manually because it greatly benefits the learning process and your memory. All of the source code used in this book is available for download at www.wiley.com/go/proc++4e.

Alternatively, you can go to the main Wrox code download page at www.wrox.com/dynamic/books/download.aspx to see the code that is available for this book and all other Wrox books.

Once you’ve downloaded the code, just decompress it with your favorite decompression tool.

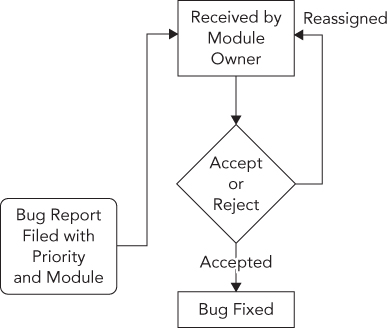

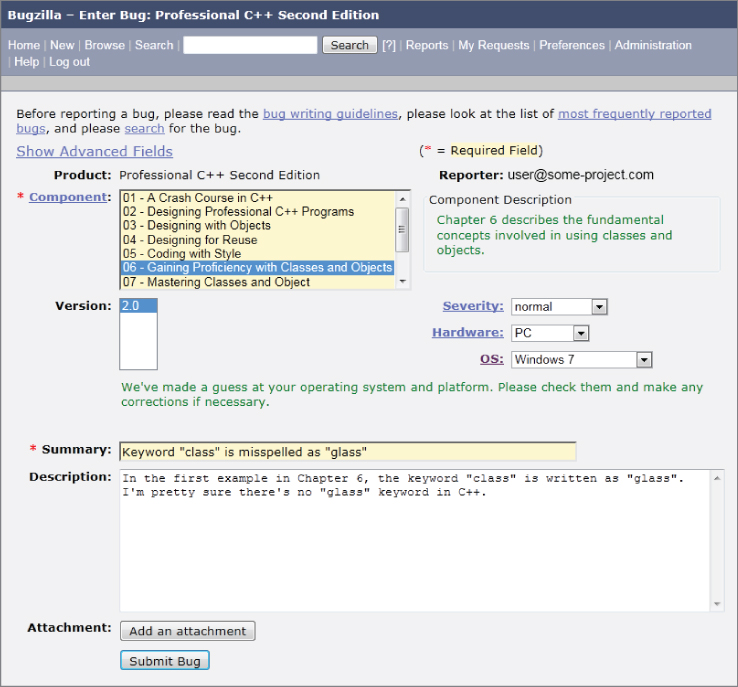

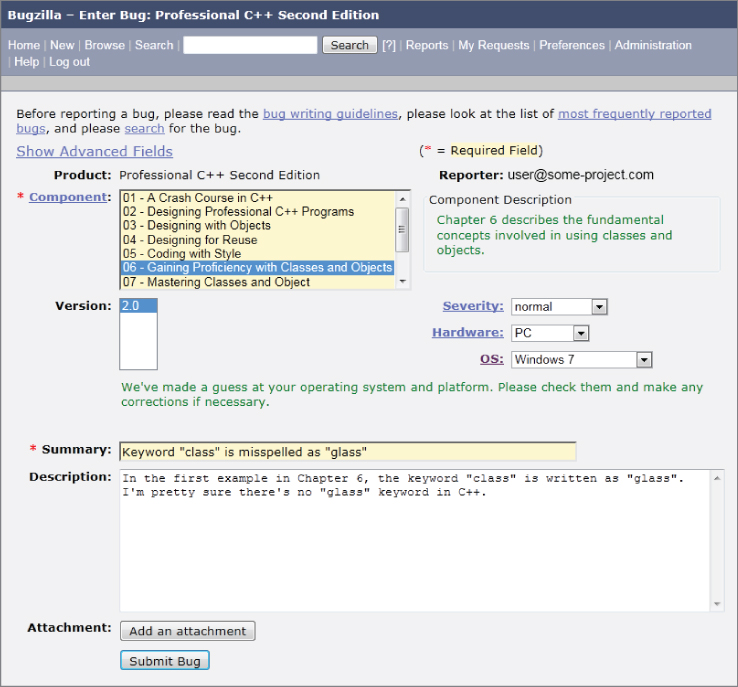

At Wrox, we make every effort to ensure that there are no errors in the text or in the code of our books. However, no one is perfect, and mistakes do occur. If you find an error in one of our books, such as a spelling mistake or faulty piece of code, we would be very grateful for your feedback. By sending in errata, you may save another reader hours of frustration, and at the same time you will be helping us provide even higher-quality information.

To find the errata page for this book, go to www.wrox.com and locate the title by using the Search box or one of the title lists. Then, on the book details page, click the Book Errata link. On this page you can view all errata that has been submitted for this book and posted by Wrox editors. A complete book list, including links to each book’s errata, is also available at www.wrox.com/misc-pages/booklist.shtml.

If you don’t spot “your” error on the Book Errata page, go to www.wrox.com/contact/techsupport.shtml and complete the form there to send us the error you have found. We’ll check the information and, if appropriate, post a message to the book’s errata page and fix the problem in subsequent editions of the book.

The C++ language is often viewed as a “better C” or a “superset of C.” It was mainly designed to be an object-oriented C, commonly called as “C with classes.” Later on, many of the annoyances and rough edges of the C language were addressed as well. Because C++ is based on C, much of the syntax you’ll see in this section will look familiar to you if you are an experienced C programmer. The two languages certainly have their differences, though. As evidence, The C++ Programming Language by C++ creator Bjarne Stroustrup (Fourth Edition; Addison-Wesley Professional, 2013) weighs in at 1,368 pages, while Kernighan and Ritchie’s The C Programming Language (Second Edition; Prentice Hall, 1988) is a scant 274 pages. So, if you’re a C programmer, be on the lookout for new or unfamiliar syntax!

In all its glory, the following code is the simplest C++ program you’re likely to encounter:

// helloworld.cpp#include <iostream>int main(){std::cout << "Hello, World!" << std::endl;return 0;}

This code, as you might expect, prints the message, “Hello, World!” on the screen. It is a simple program and unlikely to win any awards, but it does exhibit the following important concepts about the format of a C++ program:

main() functionThese concepts are briefly explained in the following sections.

The first line of the program is a comment, a message that exists for the programmer only and is ignored by the compiler. In C++, there are two ways to delineate a comment. In the preceding and following examples, two slashes indicate that whatever follows on that line is a comment.

// helloworld.cppThe same behavior (this is to say, none) would be achieved by using a multiline comment. Multiline comments start with /* and end with */. The following code shows a multiline comment in action (or, more appropriately, inaction).

/* This is a multiline comment.The compiler will ignore it.*/

Comments are covered in detail in Chapter 3.

Building a C++ program is a three-step process. First, the code is run through a preprocessor, which recognizes meta-information about the code. Next, the code is compiled, or translated into machine-readable object files. Finally, the individual object files are linked together into a single application.

Directives aimed at the preprocessor start with the # character, as in the line #include <iostream> in the previous example. In this case, an #include directive tells the preprocessor to take everything from the <iostream> header file and make it available to the current file. The most common use of header files is to declare functions that will be defined elsewhere. A function declaration tells the compiler how a function is called, declaring the number and types of parameters, and the function return type. A definition contains the actual code for the function. In C++, declarations usually go into header files, typically with extension .h, while definitions usually go into source files, typically with extension .cpp. A lot of other programming languages, such as C# and Java, do not separate declarations and definitions into separate files.

The <iostream> header declares the input and output mechanisms provided by C++. If the program did not include that header, it would be unable to perform its only task of outputting text.

The following table shows some of the most common preprocessor directives.

| PREPROCESSOR DIRECTIVE | FUNCTIONALITY | COMMON USES |

#include [file] |

The specified file is inserted into the code at the location of the directive. | Almost always used to include header files so that code can make use of functionality defined elsewhere. |

#define [key] [value] |

Every occurrence of the specified key is replaced with the specified value. | Often used in C to define a constant value or a macro. C++ provides better mechanisms for constants and most types of macros. Macros can be dangerous, so use them cautiously. See Chapter 11 for details. |

#ifdef [key]#endif#endif |

Code within the ifdef (“if defined”) or ifndef (“if not defined”) blocks are conditionally included or omitted based on whether the specified key has been defined with #define. |

Used most frequently to protect against circular includes. Each header file starts with an #ifndef checking the absence of a key, followed by a #define directive to define that key. The header file ends with an #endif. This prevents the file from being included multiple times; see the example after this table. |

#pragma [xyz] |

xyz is compiler dependent. It often allows the programmer to display a warning or error if the directive is reached during preprocessing. |

See the example after this table. |

One example of using preprocessor directives is to avoid multiple includes, as shown here:

#ifndef MYHEADER_H#define MYHEADER_H// … the contents of this header file#endif

If your compiler supports the #pragma once directive, and most modern compilers do, then this can be rewritten as follows:

#pragma once// … the contents of this header file

Chapter 11 discusses this in more details.

main() is, of course, where the program starts. The return type of main() is an int, indicating the result status of the program. You can omit any explicit return statements in main(), in which case zero is returned automatically. The main() function either takes no parameters, or takes two parameters as follows:

int main(int argc, char* argv[])argc gives the number of arguments passed to the program, and argv contains those arguments. Note that argv[0] can be the program name, but it might as well be an empty string, so do not rely on it; instead, use platform-specific functionality to retrieve the program name. The important thing to remember is that the actual parameters start at index 1.

I/O streams are covered in depth in Chapter 13, but the basics of output and input are very simple. Think of an output stream as a laundry chute for data. Anything you toss into it will be output appropriately. std::cout is the chute corresponding to the user console, or standard out. There are other chutes, including std::cerr, which outputs to the error console. The << operator tosses data down the chute. In the preceding example, a quoted string of text is sent to standard out. Output streams allow multiple types of data to be sent down the stream sequentially on a single line of code. The following code outputs text, followed by a number, followed by more text:

std::cout << "There are " << 219 << " ways I love you." << std::endl;std::endl represents an end-of-line sequence. When the output stream encounters std::endl, it will output everything that has been sent down the chute so far and move to the next line. An alternate way of representing the end of a line is by using the \n character. The \n character is an escape sequence, which refers to a new-line character. Escape sequences can be used within any quoted string of text. The following table shows the most common ones:

\n |

new line |

\r |

carriage return |

\t |

tab |

\\ |

backslash character |

\" |

quotation mark |

Streams can also be used to accept input from the user. The simplest way to do this is to use the >> operator with an input stream. The std::cin input stream accepts keyboard input from the user. Here is an example:

int value;std::cin >> value;

User input can be tricky because you can never know what kind of data the user will enter. See Chapter 13 for a full explanation of how to use input streams.

If you’re new to C++ and coming from a C background, you’re probably wondering what has been done with the trusty old printf() and scanf() functions. While these functions can still be used in C++, I recommend using the streams library instead, mainly because the printf() and scanf() family of functions do not provide any type safety.

Namespaces address the problem of naming conflicts between different pieces of code. For example, you might be writing some code that has a function called foo(). One day, you decide to start using a third-party library, which also has a foo() function. The compiler has no way of knowing which version of foo() you are referring to within your code. You can’t change the library’s function name, and it would be a big pain to change your own.

Namespaces come to the rescue in such scenarios because you can define the context in which names are defined. To place code in a namespace, enclose it within a namespace block. For example, the following could be the contents of a file called namespaces.h:

namespace mycode {void foo();}

The implementation of a method or function can also be handled in a namespace. The foo() function, for instance, could be implemented in namespaces.cpp as follows:

#include <iostream>#include "namespaces.h"void mycode::foo(){std::cout << "foo() called in the mycode namespace" << std::endl;}

Or alternatively:

#include <iostream>#include "namespaces.h"namespace mycode {void foo(){std::cout << "foo() called in the mycode namespace" << std::endl;}}

By placing your version of foo() in the namespace “mycode,” you are isolating it from the foo() function provided by the third-party library. To call the namespace-enabled version of foo(), prepend the namespace onto the function name by using ::, also called the scope resolution operator, as follows:

mycode::foo(); // Calls the "foo" function in the "mycode" namespaceAny code that falls within a “mycode” namespace block can call other code within the same namespace without explicitly prepending the namespace. This implicit namespace is useful in making the code more readable. You can also avoid prepending of namespaces with the using directive. This directive tells the compiler that the subsequent code is making use of names in the specified namespace. The namespace is thus implied for the code that follows:

#include "namespaces.h"using namespace mycode;int main(){foo(); // Implies mycode::foo();return 0;}

A single source file can contain multiple using directives, but beware of overusing this shortcut. In the extreme case, if you declare that you’re using every namespace known to humanity, you’re effectively eliminating namespaces entirely! Name conflicts will again result if you are using two namespaces that contain the same names. It is also important to know in which namespace your code is operating so that you don’t end up accidentally calling the wrong version of a function.

You’ve seen the namespace syntax before—you used it in the Hello, World program, where cout and endl are actually names defined in the std namespace. You could have written Hello, World with the using directive as shown here:

#include <iostream>using namespace std;int main(){cout <<"Hello, World!"<< endl;return 0;}

A using declaration can be used to refer to a particular item within a namespace. For example, if the only part of the std namespace that you intend to use is cout, you can refer to it as follows:

using std::cout;Subsequent code can refer to cout without prepending the namespace, but other items in the std namespace will still need to be explicit:

using std::cout;cout << "Hello, World!" << std::endl;

C++17 makes it easier to work with nested namespaces. A nested namespace is a namespace inside another one. Before C++17, you had to use nested namespaces as follows:

C++17 makes it easier to work with nested namespaces. A nested namespace is a namespace inside another one. Before C++17, you had to use nested namespaces as follows:

namespace MyLibraries {namespace Networking {namespace FTP {/* … */}}}

This can be simplified a lot with C++17:

namespace MyLibraries::Networking::FTP {/* … */}

A namespace alias can be used to give a new and possibly shorter name to another namespace. For example: namespace MyFTP = MyLibraries::Networking::FTP;

Literals are used to write numbers or strings in your code. C++ supports a number of standard literals. Numbers can be specified with the following literals (the examples in the list represent the same number, 123):

12301730x7B0b1111011Other examples of literals in C++ include

3.14f)3.14)'a')"character array")It is also possible to define your own type of literals, which is an advanced feature explained in Chapter 11.

Digits separators can be used in numeric literals. A digits separator is a single quote character. For example,

23'456'7890.123'456f C++17 adds support for hexadecimal floating-point literals—for example,

C++17 adds support for hexadecimal floating-point literals—for example, 0x3.ABCp-10, 0Xb.cp12l.

In C++, variables can be declared just about anywhere in your code and can be used anywhere in the current block below the line where they are declared. Variables can be declared without being given a value. These uninitialized variables generally end up with a semi-random value based on whatever is in memory at that time, and are therefore the source of countless bugs. Variables in C++ can alternatively be assigned an initial value when they are declared. The code that follows shows both flavors of variable declaration, both using ints, which represent integer values.

int uninitializedInt;int initializedInt = 7;cout << uninitializedInt << " is a random value" << endl;cout << initializedInt << " was assigned an initial value" << endl;

The following table shows the most common types used in C++.

| TYPE | DESCRIPTION | USAGE |

(signed) intsigned |

Positive and negative integers; the range depends on the compiler (usually 4 bytes). | int i = -7;signed int i = -6;signed i = -5; |

(signed) short (int) |

Short integer (usually 2 bytes) | short s = 13;short int s = 14;signed short s = 15;signed short int s = 16; |

(signed) long (int) |

Long integer (usually 4 bytes) | long l = -7L; |

(signed) long long (int) |

Long long integer; the range depends on the compiler, but is at least the same as for long (usually 8 bytes). |

long long ll = 14LL; |

unsigned (int)unsigned short (int)unsigned long (int)unsigned long long (int) |

Limits the preceding types to values >= 0 | unsigned int i = 2U;unsigned j = 5U;unsigned short s = 23U;unsigned long l = 5400UL;unsigned long long ll = 140ULL; |

float |

Floating-point numbers | float f = 7.2f; |

double |

Double precision numbers; precision is at least the same as for float. |

double d = 7.2; |

long double |

Long double precision numbers; precision is at least the same as for double. |

long double d = 16.98L; |

char |

A single character | char ch = 'm'; |

char16_t |

A single 16-bit character | char16_t c16 = u'm'; |

char32_t |

A single 32-bit character | char32_t c32 = U'm'; |

wchar_t |

A single wide character; the size depends on the compiler. | wchar_t w = L'm'; |

bool |

A Boolean type that can have one of two values: true or false |

bool b = true; |

std::byte1 |

A single byte. Before C++17, a char or unsigned char was used to represent a byte, but those types make it look like you are working with characters. std::byte on the other hand clearly states your intention, that is, a single byte of memory. |

std::byte b{42};2 |

1Requires an include directive for the <cstddef> header file.

2Initialization of an std::byte requires direct list initialization with a single-element list. See the “Direct List Initialization versus Copy List Initialization” section later in this chapter for the definition of direct list initialization.

Variables can be converted to other types by casting them. For example, a float can be cast to an int. C++ provides three ways to explicitly change the type of a variable. The first method is a holdover from C; it is not recommended but unfortunately still commonly used. The second method is rarely used. The third method is the most verbose, but is also the cleanest one, and is therefore recommended.

float myFloat = 3.14f;int i1 = (int)myFloat; // method 1int i2 = int(myFloat); // method 2int i3 = static_cast<int>(myFloat); // method 3

The resulting integer will be the value of the floating-point number with the fractional part truncated. Chapter 11 describes the different casting methods in more detail. In some contexts, variables can be automatically cast, or coerced. For example, a short can be automatically converted into a long because a long represents the same type of data with at least the same precision.

long someLong = someShort; // no explicit cast neededWhen automatically casting variables, you need to be aware of the potential loss of data. For example, casting a float to an int throws away information (the fractional part of the number). Most compilers will issue a warning or even an error if you assign a float to an int without an explicit cast. If you are certain that the left-hand side type is fully compatible with the right-hand side type, it’s okay to cast implicitly.

What good is a variable if you don’t have a way to change it? The following table shows the most common operators used in C++ and sample code that makes use of them. Note that operators in C++ can be binary (operate on two expressions), unary (operate on a single expression), or even ternary (operate on three expressions). There is only one ternary operator in C++, and it is explained in the “Conditional Statements” section later in this chapter.

| OPERATOR | DESCRIPTION | USAGE |

= |

Binary operator to assign the value on the right to the expression on the left | int i;i = 3;int j;j = i; |

! |

Unary operator to complement the true/false (non-0/0) status of an expression | bool b = !true;bool b2 = !b; |

+ |

Binary operator for addition | int i = 3 + 2;int j = i + 5;int k = i + j; |

-*/ |

Binary operators for subtraction, multiplication, and division | int i = 5 - 1;int j = 5 * 2;int k = j / i; |

% |

Binary operator for the remainder of a division operation. This is also referred to as the mod or modulo operator. | int remainder = 5 % 2; |

++ |

Unary operator to increment an expression by 1. If the operator occurs after the expression, or post-increment, the result of the expression is the unincremented value. If the operator occurs before the expression, or pre-increment, the result of the expression is the new value. | i++;++i; |

-- |

Unary operator to decrement an expression by 1 | i--;--i; |

+= |

Shorthand syntax for i = i + j |

i += j; |

-=*=/=%= |

Shorthand syntax fori = i - j;i = i * j;i = i / j;i = i % j; |

i -= j;i *= j;i /= j;i %= j; |

&&= |

Takes the raw bits of one expression and performs a bitwise “AND” with the other expression | i = j & k;j &= k; |

||= |

Takes the raw bits of one expression and performs a bitwise “OR” with the other expression | i = j | k;j |= k; |

<<>><<=>>= |

Takes the raw bits of an expression and “shifts” each bit left (<<) or right (>>) the specified number of places |

i = i << 1;i = i >> 4;i <<= 1;i >>= 4; |

^^= |

Performs a bitwise “exclusive or,” also called “XOR” operation, on two expressions | i = i ^ j;i ^= j; |

The following program shows the most common variable types and operators in action. If you are unsure about how variables and operators work, try to figure out what the output of this program will be, and then run it to confirm your answer.

int someInteger = 256;short someShort;long someLong;float someFloat;double someDouble;someInteger++;someInteger *= 2;someShort = static_cast<short>(someInteger);someLong = someShort * 10000;someFloat = someLong + 0.785f;someDouble = static_cast<double>(someFloat) / 100000;cout << someDouble << endl;

The C++ compiler has a recipe for the order in which expressions are evaluated. If you have a complicated line of code with many operators, the order of execution may not be obvious. For that reason, it’s probably better to break up a complicated expression into several smaller expressions, or explicitly group sub-expressions by using parentheses. For example, the following line of code is confusing unless you happen to know the C++ operator precedence table by heart:

int i = 34 + 8 * 2 + 21 / 7 % 2;Adding parentheses makes it clear which operations are happening first:

int i = 34 + (8 * 2) + ( (21 / 7) % 2 );For those of you playing along at home, both approaches are equivalent and end up with i equal to 51. If you assumed that C++ evaluated expressions from left to right, your answer would have been 1. C++ evaluates /, *, and % first (in left-to-right order), followed by addition and subtraction, then bitwise operators. Parentheses let you explicitly tell the compiler that a certain operation should be evaluated separately.

In C++, you can use the basic types (int, bool, and so on) to build more complex types of your own design. Once you are an experienced C++ programmer, you will rarely use the following techniques, which are features brought in from C, because classes are far more powerful. Still, it is important to know about the following ways of building types so that you will recognize the syntax.

An integer really represents a value within a sequence—the sequence of numbers. Enumerated types let you define your own sequences so that you can declare variables with values in that sequence. For example, in a chess program, you could represent each piece as an int, with constants for the piece types, as shown in the following code. The integers representing the types are marked const to indicate that they can never change.

const int PieceTypeKing = 0;const int PieceTypeQueen = 1;const int PieceTypeRook = 2;const int PieceTypePawn = 3;//etc.int myPiece = PieceTypeKing;

This representation is fine, but it can become dangerous. Since a piece is just an int, what would happen if another programmer added code to increment the value of a piece? By adding 1, a king becomes a queen, which really makes no sense. Worse still, someone could come in and give a piece a value of -1, which has no corresponding constant.

Enumerated types solve these problems by tightly defining the range of values for a variable. The following code declares a new type, PieceType, which has four possible values, representing four of the chess pieces:

enum PieceType { PieceTypeKing, PieceTypeQueen, PieceTypeRook, PieceTypePawn };Behind the scenes, an enumerated type is just an integer value. The real value of PieceTypeKing is 0. However, by defining the possible values for variables of type PieceType, your compiler can give you a warning or an error if you attempt to perform arithmetic on PieceType variables or treat them as integers. The following code, which declares a PieceType variable, and then attempts to use it as an integer, results in a warning or an error on most compilers:

PieceType myPiece;myPiece = 0;

It’s also possible to specify the integer values for members of an enumeration. The syntax is as follows:

enum PieceType { PieceTypeKing = 1, PieceTypeQueen, PieceTypeRook = 10, PieceTypePawn };In this example, PieceTypeKing has the integer value 1, PieceTypeQueen has the value 2 assigned by the compiler, PieceTypeRook has the value 10, and PieceTypePawn has the value 11 assigned automatically by the compiler.

If you do not assign a value to an enumeration member, the compiler automatically assigns it a value that is the previous enumeration member incremented by 1. If you do not assign a value to the first enumeration member yourself, the compiler assigns it the value 0.

Enumerations as explained in the previous section are not strongly typed, meaning they are not type safe. They are always interpreted as integers, and thus you can compare enumeration values from completely different enumeration types.

The strongly-typed enum class enumerations solve this problem. For example, the following defines a type-safe version of the earlier-defined PieceType enumeration:

enum class PieceType{King = 1,Queen,Rook = 10,Pawn};

For an enum class, the enumeration value names are not automatically exported to the enclosing scope, which means that you always have to use the scope resolution operator:

PieceType piece = PieceType::King;This also means that you can give shorter names to the enumeration values, for example, King instead of PieceTypeKing.

Additionally, the enumeration values are not automatically converted to integers, which means the following is illegal:

if (PieceType::Queen == 2) {…}By default, the underlying type of an enumeration value is an integer, but this can be changed as follows:

enum class PieceType : unsigned long{King = 1,Queen,Rook = 10,Pawn};

Structs let you encapsulate one or more existing types into a new type. The classic example of a struct is a database record. If you are building a personnel system to keep track of employee information, you might want to store the first initial, last initial, employee number, and salary for each employee. A struct that contains all of this information is shown in the employeestruct.h header file that follows:

struct Employee {char firstInitial;char lastInitial;int employeeNumber;int salary;};

A variable declared with type Employee will have all of these fields built in. The individual fields of a struct can be accessed by using the “.” operator. The example that follows creates and then outputs the record for an employee:

#include <iostream>#include "employeestruct.h"using namespace std;int main(){// Create and populate an employee.Employee anEmployee;anEmployee.firstInitial = 'M';anEmployee.lastInitial = 'G';anEmployee.employeeNumber = 42;anEmployee.salary = 80000;// Output the values of an employee.cout << "Employee: " << anEmployee.firstInitial <<anEmployee.lastInitial << endl;cout << "Number: " << anEmployee.employeeNumber << endl;cout << "Salary: $" << anEmployee.salary << endl;return 0;}

Conditional statements let you execute code based on whether or not something is true. As shown in the following sections, there are three main types of conditional statements in C++: if/else statements, switch statements, and conditional operators.

The most common conditional statement is the if statement, which can be accompanied by an else. If the condition given inside the if statement is true, the line or block of code is executed. If not, execution continues with the else case if present, or with the code following the conditional statement. The following code shows a cascading if statement, a fancy way of saying that the if statement has an else statement that in turn has another if statement, and so on:

if (i > 4) {// Do something.} else if (i > 2) {// Do something else.} else {// Do something else.}

The expression between the parentheses of an if statement must be a Boolean value or evaluate to a Boolean value. A value of 0 evaluates to false, while any non-zero value evaluates to true. For example: if(0) is equivalent to if(false). Logical evaluation operators, described later, provide ways of evaluating expressions to result in a true or false Boolean value.

Initializers for if Statements

Initializers for if StatementsC++17 allows you to include an initializer inside an if statement using the following syntax:

if (<initializer> ; <conditional_expression>) { <body> }Any variable introduced in the <initializer> is only available in the <conditional_expression> and in the <body>. Such variables are not available outside the if statement.

It is too early in this book to give a useful example of this feature, but here is what it looks like:

if (Employee employee = GetEmployee() ; employee.salary > 1000) { … }In this example, the initializer gets an employee and the condition checks whether the salary of the retrieved employee exceeds 1000. Only in that case is the body of the if statement executed.

More concrete examples will be given throughout this book.

The switch statement is an alternate syntax for performing actions based on the value of an expression. In C++, the expression of a switch statement must be of an integral type, a type convertible to an integral type, an enumerated type, or a strongly typed enumeration, and must be compared to constants. Each constant value represents a “case.” If the expression matches the case, the subsequent lines of code are executed until a break statement is reached. You can also provide a default case, which is matched if none of the other cases match. The following pseudocode shows a common use of the switch statement:

switch (menuItem) {case OpenMenuItem:// Code to open a filebreak;case SaveMenuItem:// Code to save a filebreak;default:// Code to give an error messagebreak;}

A switch statement can always be converted into if/else statements. The previous switch statement can be converted as follows:

if (menuItem == OpenMenuItem) {// Code to open a file} else if (menuItem == SaveMenuItem) {// Code to save a file} else {// Code to give an error message}

switch statements are generally used when you want to do something based on more than 1 specific value of an expression, as opposed to some test on the expression. In such a case, the switch statement avoids cascading if-else statements. If you only need to inspect 1 value, an if or if-else statement is fine.

Once a case expression matching the switch condition is found, all statements that follow it are executed until a break statement is reached. This execution continues even if another case expression is encountered, which is called fallthrough. The following example has a single set of statements that is executed for several different cases:

switch (backgroundColor) {case Color::DarkBlue:case Color::Black:// Code to execute for both a dark blue or black background colorbreak;case Color::Red:// Code to execute for a red background colorbreak;}

Fallthrough can be a source of bugs, for example if you accidentally forget a break statement. Because of this, compilers might give a warning if a fallthrough is detected in a

Fallthrough can be a source of bugs, for example if you accidentally forget a break statement. Because of this, compilers might give a warning if a fallthrough is detected in a switch statement, unless the case is empty as in the above example. Starting with C++17, you can tell the compiler that a fallthrough is intentional using the [[fallthrough]] attribute as follows:

switch (backgroundColor) {case Color::DarkBlue:doSomethingForDarkBlue();[[fallthrough]];case Color::Black:// Code is executed for both a dark blue or black background colordoSomethingForBlackOrDarkBlue();break;case Color::Red:case Color::Green:// Code to execute for a red or green background colorbreak;}

Initializers for switch Statements

Initializers for switch StatementsJust as for if statements, C++17 adds support for initializers to switch statements. The syntax is as follows:

switch (<initializer> ; <expression>) { <body> }Any variables introduced in the <initializer> are only available in the <expression> and in the <body>. They are not available outside the switch statement.

C++ has one operator that takes three arguments, known as a ternary operator. It is used as a shorthand conditional expression of the form “if [something] then [perform action], otherwise [perform some other action].” The conditional operator is represented by a ? and a :. The following code outputs “yes” if the variable i is greater than 2, and “no” otherwise:

std::cout << ((i > 2) ? "yes" : "no");The parentheses around i > 2 are optional, so the following is equivalent:

std::cout << (i > 2 ? "yes" : "no");The advantage of the conditional operator is that it can occur within almost any context. In the preceding example, the conditional operator is used within code that performs output. A convenient way to remember how the syntax is used is to treat the question mark as though the statement that comes before it really is a question. For example, “Is i greater than 2? If so, the result is ‘yes’; if not, the result is ‘no.’”

Unlike an if statement or a switch statement, the conditional operator doesn’t execute code blocks based on the result. Instead, it is used within code, as shown in the preceding example. In this way, it really is an operator (like + and -) as opposed to a true conditional statement, such as if and switch.

You have already seen a logical evaluation operator without a formal definition. The > operator compares two values. The result is “true” if the value on the left is greater than the value on the right. All logical evaluation operators follow this pattern—they all result in a true or false.

The following table shows common logical evaluation operators:

| OP | DESCRIPTION | USAGE |

|

< <= > >= |

Determines if the left-hand side is less than, less than or equal to, greater than, or greater than or equal to the right-hand side |

|

| == | Determines if the left-hand side equals the right-hand side. Don’t confuse this with the = (assignment) operator! |

|

| != | Not equals. The result of the statement is true if the left-hand side does not equal the right-hand side. |

|

| ! |

Logical NOT. This complements the true/false status of a Boolean expression. This is a unary operator. |

|

| && | Logical AND. The result is true if both parts of the expression are true. |

|

| || | Logical OR. The result is true if either part of the expression is true. |

|

C++ uses short-circuit logic when evaluating logical expressions. That means that once the final result is certain, the rest of the expression won’t be evaluated. For example, if you are performing a logical OR operation of several Boolean expressions, as shown in the following code, the result is known to be true as soon as one of them is found to be true. The rest won’t even be checked.

bool result = bool1 || bool2 || (i > 7) || (27 / 13 % i + 1) < 2;In this example, if bool1 is found to be true, the entire expression must be true, so the other parts aren’t evaluated. In this way, the language saves your code from doing unnecessary work. It can, however, be a source of hard-to-find bugs if the later expressions in some way influence the state of the program (for example, by calling a separate function). The following code shows a statement using && that short-circuits after the second term because 0 always evaluates to false:

bool result = bool1 && 0 && (i > 7) && !done;Short-circuiting can be beneficial for performance. You can put cheaper tests first so that more expensive tests are not even executed when the logic short-circuits. It is also useful in the context of pointers to avoid parts of the expression to be executed when a pointer is not valid. Pointers and short-circuiting with pointers are discussed later in this chapter.

For programs of any significant size, placing all the code inside of main() is unmanageable. To make programs easy to understand, you need to break up, or decompose, code into concise functions.

In C++, you first declare a function to make it available for other code to use. If the function is used inside only a particular file, you generally declare and define the function in the source file. If the function is for use by other modules or files, you generally put the declaration in a header file and the definition in a source file.

A function declaration is shown in the following code. This example has a return type of void, indicating that the function does not provide a result to the caller. The caller must provide two arguments for the function to work with—an integer and a character.

void myFunction(int i, char c);Without an actual definition to match this function declaration, the link stage of the compilation process will fail because code that makes use of the function will be calling nonexistent code. The following definition prints the values of the two parameters:

void myFunction(int i, char c){std::cout << "the value of i is " << i << std::endl;std::cout << "the value of c is " << c << std::endl;}

Elsewhere in the program, you can make calls to myFunction() and pass in arguments for the two parameters. Some sample function calls are shown here:

myFunction(8, 'a');myFunction(someInt, 'b');myFunction(5, someChar);

C++ functions can also return a value to the caller. The following function adds two numbers and returns the result:

int addNumbers(int number1, int number2){return number1 + number2;}

This function can be called as follows:

int sum = addNumbers(5, 3);With C++14, you can ask the compiler to figure out the return type of a function automatically. To make use of this functionality, you need to specify auto as the return type:

auto addNumbers(int number1, int number2){return number1 + number2;}

The compiler deduces the return type based on the expressions used for the return statements. There can be multiple return statements in the function, but they should all resolve to the same type. Such a function can even include recursive calls (calls to itself), but the first return statement in the function must be a non-recursive call.

Every function has a local predefined variable __func__ containing the name of the current function. One use of this variable would be for logging purposes:

int addNumbers(int number1, int number2){std::cout << "Entering function " << __func__ << std::endl;return number1 + number2;}

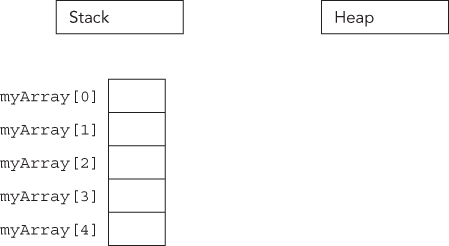

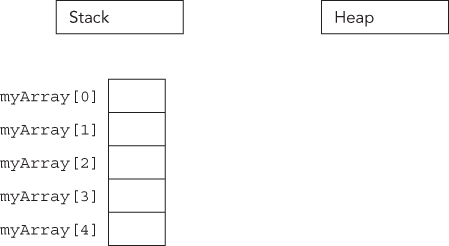

Arrays hold a series of values, all of the same type, each of which can be accessed by its position in the array. In C++, you must provide the size of the array when the array is declared. You cannot give a variable as the size—it must be a constant, or a constant expression (constexpr). Constant expressions are discussed in Chapter 11. The code that follows shows the declaration of an array of three integers followed by three lines to initialize the elements to 0:

int myArray[3];myArray[0] = 0;myArray[1] = 0;myArray[2] = 0;

The next section discusses loops that you can use to initialize each element. However, instead of using loops, or using the previous initialization mechanism, you can also accomplish the zero-initialization with the following one-liner:

int myArray[3] = {0};You can even drop the 0 as follows:

int myArray[3] = {};An array can also be initialized with an initializer list, in which case the compiler can deduce the size of the array automatically. For example,

int myArray[] = {1, 2, 3, 4}; // The compiler creates an array of 4 elements.If you do specify the size of the array, and the initializer list has less elements than the given size, the remaining elements are set to 0. For example, the following code only sets the first element in the array to the value 2, and sets all the other elements to 0:

int myArray[3] = {2};To get the size of a stack-based C-style array, you can use the C++17 std::size() function (requires <array>). For example:

unsigned int arraySize = std::size(myArray);If your compiler is not yet C++17 compliant, the old trick to get the size of a stack-based C-style array is to use the sizeof operator. The sizeof operator returns the size of its argument in bytes. To get the number of elements in a stack-based array, you divide the size in bytes of the array by the size in bytes of the first element. For example:

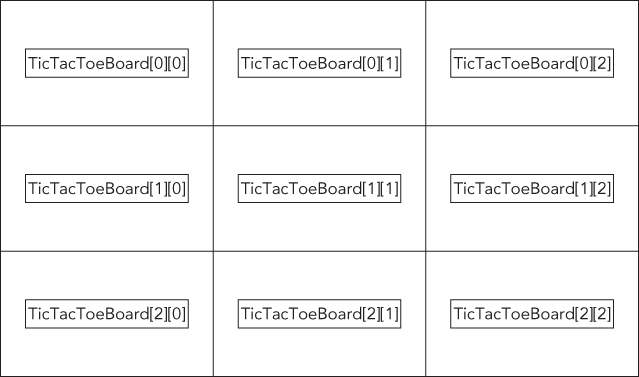

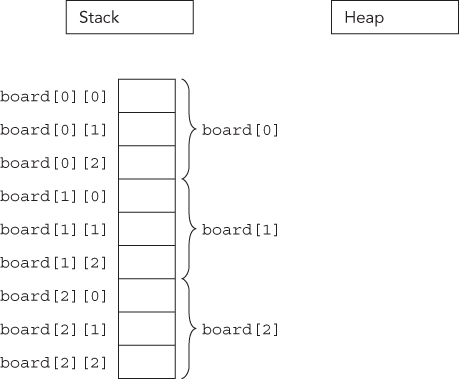

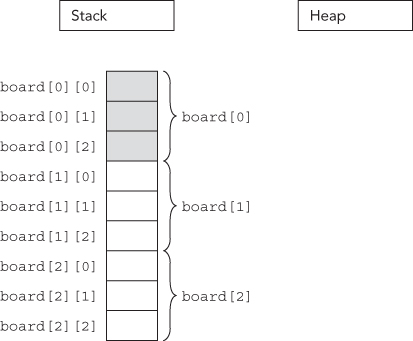

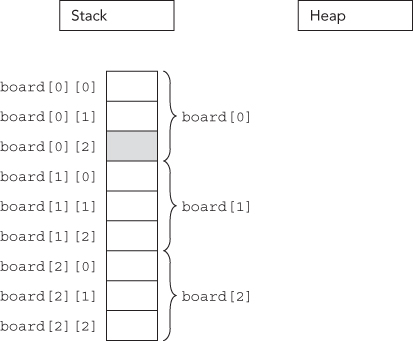

unsigned int arraySize = sizeof(myArray) / sizeof(myArray[0]);The preceding examples show a one-dimensional array, which you can think of as a line of integers, each with its own numbered compartment. C++ allows multi-dimensional arrays. You might think of a two-dimensional array as a checkerboard, where each location has a position along the x-axis and a position along the y-axis. Three-dimensional and higher arrays are harder to picture and are rarely used. The following code shows the syntax for allocating a two-dimensional array of characters for a Tic-Tac-Toe board and then putting an “o” in the center square:

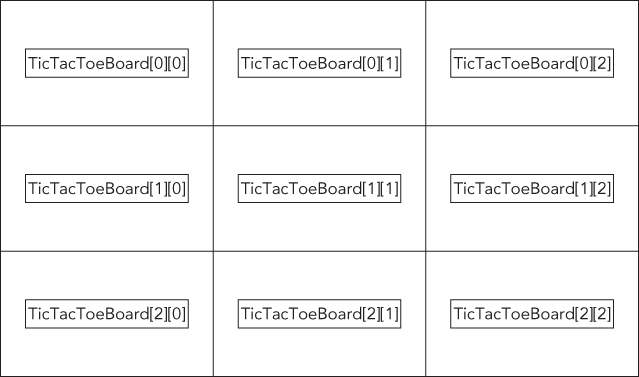

char ticTacToeBoard[3][3];ticTacToeBoard[1][1] = 'o';

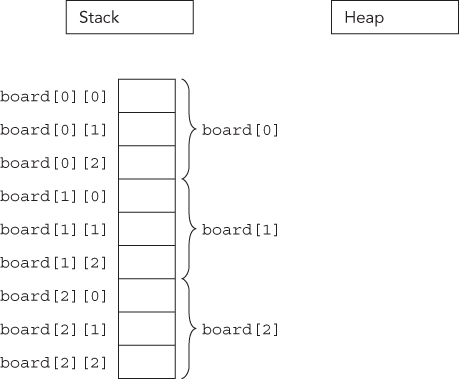

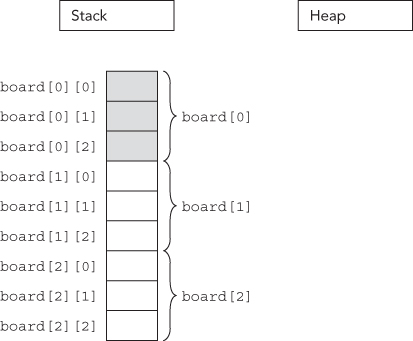

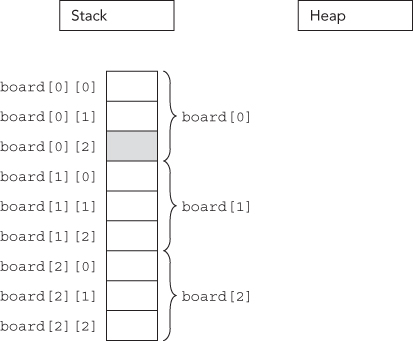

Figure 1-1 shows a visual representation of this board with the position of each square.

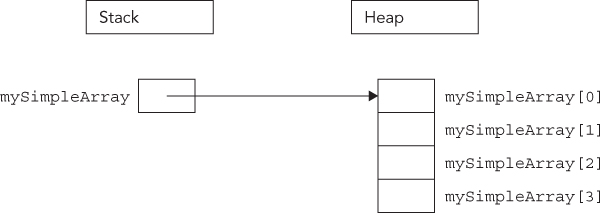

The arrays discussed in the previous section come from C, and still work in C++. However, C++ has a special type of fixed-size container called std::array, defined in the <array> header file. It’s basically a thin wrapper around C-style arrays.

There are a number of advantages to using std::arrays instead of C-style arrays. They always know their own size, are not automatically cast to a pointer to avoid certain types of bugs, and have iterators to easily loop over the elements. Iterators are discussed in detail in Chapter 17.

The following example demonstrates how to use the array container. The use of angle brackets after array, as in array<int, 3>, will become clear during the discussion of templates in Chapter 12. However, for now, just remember that you have to specify two parameters between the angle brackets. The first parameter represents the type of the elements in the array, and the second one represents the size of the array.

array<int, 3> arr = {9, 8, 7};cout << "Array size = " << arr.size() << endl;cout << "2nd element = " << arr[1] << endl;

If you want an array with a dynamic size, it is recommended to use std::vector, as explained in the next section. A vector automatically increases in size when you add new elements to it.

The C++ Standard Library provides a number of different non-fixed-size containers that can be used to store information. std::vector, declared in <vector>, is an example of such a container. The vector replaces the concept of C-style arrays with a much more flexible and safer mechanism. As a user, you need not worry about memory management, as the vector automatically allocates enough memory to hold its elements. A vector is dynamic, meaning that elements can be added and removed at run time. Chapter 17 goes into more detail regarding containers, but the basic use of a vector is straightforward, which is why it’s introduced in the beginning of this book so that it can be used in examples. The following code demonstrates the basic functionality of vector.

// Create a vector of integersvector<int> myVector = { 11, 22 };// Add some more integers to the vector using push_back()myVector.push_back(33);myVector.push_back(44);// Access elementscout << "1st element: " << myVector[0] << endl;

myVector is declared as vector<int>. The angle brackets are required to specify the template parameters, just as with std::array. A vector is a generic container. It can contain almost any kind of object; that’s why you have to specify the type of object you want in your vector between the angle brackets. Templates are discussed in detail in Chapters 12 and 22.

To add elements to a vector, you can use the push_back() method. Individual elements can be accessed using a similar syntax as for arrays, i.e. operator[].

Structured Bindings

Structured BindingsC++17 introduces the concept of structured bindings. Structured bindings allow you to declare multiple variables that are initialized with elements from an array, struct, pair, or tuple.

For example, assume you have the following array:

std::array<int, 3> values = { 11, 22, 33 };You can declare three variables, x, y, and z, initialized with the three values from the array as follows. Note that you have to use the auto keyword for structured bindings. You cannot, for example, specify int instead of auto.

auto [x, y, z] = values; The number of variables declared with the structured binding has to match the number of values in the expression on the right.

Structured bindings also work with structures if all non-static members are public. For example,

struct Point { double mX, mY, mZ; };Point point;point.mX = 1.0; point.mY = 2.0; point.mZ = 3.0;auto [x, y, z] = point;

Examples with std::pair and std::tuple are given in chapters 17 and 20 respectively.

Computers are great for doing the same thing over and over. C++ provides four looping mechanisms: the while loop, do/while loop, for loop, and range-based for loop.

The while loop lets you perform a block of code repeatedly as long as an expression evaluates to true. For example, the following completely silly code will output “This is silly.” five times:

int i = 0;while (i < 5) {std::cout << "This is silly." << std::endl;++i;}

The keyword break can be used within a loop to immediately get out of the loop and continue execution of the program. The keyword continue can be used to return to the top of the loop and reevaluate the while expression. However, using continue in loops is often considered poor style because it causes the execution of a program to jump around somewhat haphazardly, so use it sparingly.

C++ also has a variation on the while loop called do/while. It works similarly to the while loop, except that the code to be executed comes first, and the conditional check for whether or not to continue happens at the end. In this way, you can use a loop when you want a block of code to always be executed at least once and possibly additional times based on some condition. The example that follows outputs the statement, “This is silly.” once, even though the condition ends up being false:

int i = 100;do {std::cout << "This is silly." << std::endl;++i;} while (i < 5);

The for loop provides another syntax for looping. Any for loop can be converted to a while loop and vice versa. However, the for loop syntax is often more convenient because it looks at a loop in terms of a starting expression, an ending condition, and a statement to execute at the end of every iteration. In the following code, i is initialized to 0; the loop continues as long as i is less than 5; and at the end of every iteration, i is incremented by 1. This code does the same thing as the while loop example, but is more readable because the starting value, ending condition, and per-iteration statement are all visible on one line.

for (int i = 0; i < 5; ++i) {std::cout << "This is silly." << std::endl;}

The range-based for loop is the fourth looping mechanism. It allows for easy iteration over elements of a container. This type of loop works for C-style arrays, initializer lists (discussed later in this chapter), and any type that has begin() and end() methods returning iterators (see Chapter 17), such as std::array, std::vector, and all other Standard Library containers discussed in Chapter 17.

The following example first defines an array of four integers. The range-based for loop then iterates over a copy of every element in this array and prints each value. To iterate over the elements themselves without making copies, use a reference variable, as I discuss later in this chapter.

std::array<int, 4> arr = {1, 2, 3, 4};for (int i : arr) {std::cout << i << std::endl;}

Initializer lists are defined in the <initializer_list> header file and make it easy to write functions that can accept a variable number of arguments. The initializer_list class is a template and so it requires you to specify the type of elements in the list between angle brackets, similar to how you have to specify the type of object stored in a vector. The following example shows how to use an initializer list:

#include <initializer_list>using namespace std;int makeSum(initializer_list<int> lst){int total = 0;for (int value : lst) {total += value;}return total;}

The function makeSum() accepts an initializer list of integers as argument. The body of the function uses a range-based for loop to accumulate the total sum. This function can be used as follows:

int a = makeSum({1,2,3});int b = makeSum({10,20,30,40,50,60});

Initializer lists are type safe and define which type is allowed to be in the list. For the makeSum() function shown here, all elements of the initializer list must be integers. Trying to call it with a double results in a compiler error or warning, as shown here:

int c = makeSum({1,2,3.0});At this point, you have reviewed the basic essentials of C++ programming. If this section was a breeze, skim the next section to make sure that you are up to speed on the more-advanced material. If you struggled with this section, you may want to obtain one of the fine introductory C++ books mentioned in Appendix B before continuing.

Loops, variables, and conditionals are terrific building blocks, but there is much more to learn. The topics covered next include many features designed to help C++ programmers with their code as well as a few features that are often more confusing than helpful. If you are a C programmer with little C++ experience, you should read this section carefully.

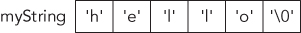

There are three ways to work with strings of text in C++: the C-style, which represents strings as arrays of characters; the C++ style, which wraps that representation in an easier-to-use string type; and the general class of nonstandard approaches. Chapter 2 provides a detailed discussion.

For now, the only thing you need to know is that the C++ string type is defined in the <string> header file, and that you can use a C++ string almost like a basic type. Just like I/O streams, the string type lives in the std namespace. The following example shows that strings can be used just like character arrays:

string myString = "Hello, World";cout << "The value of myString is " << myString << endl;cout << "The second letter is " << myString[1] << endl;

Dynamic memory allows you to build programs with data that is not of fixed size at compile time. Most nontrivial programs make use of dynamic memory in some form.

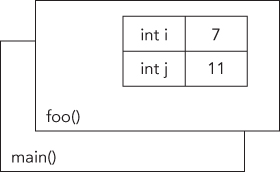

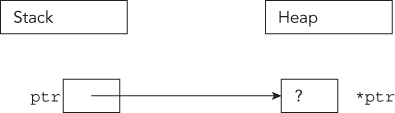

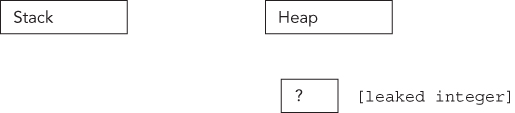

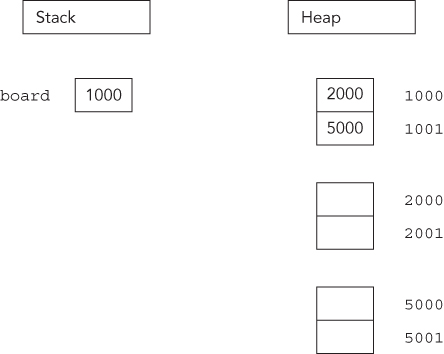

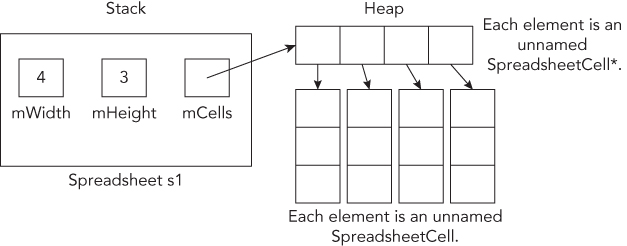

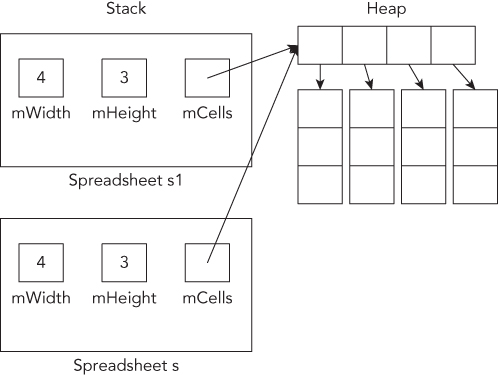

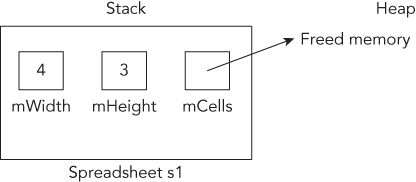

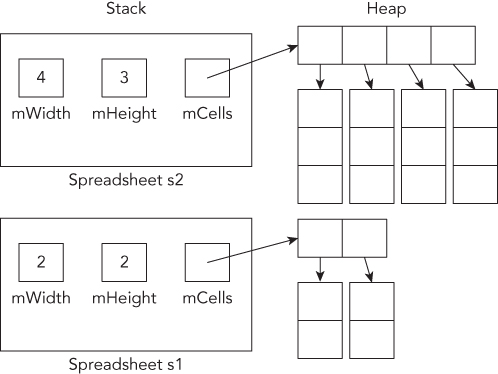

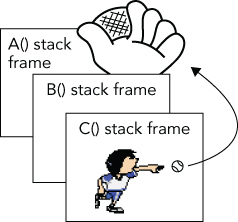

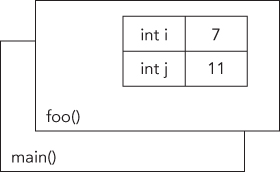

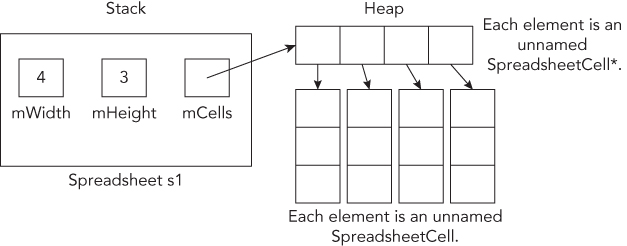

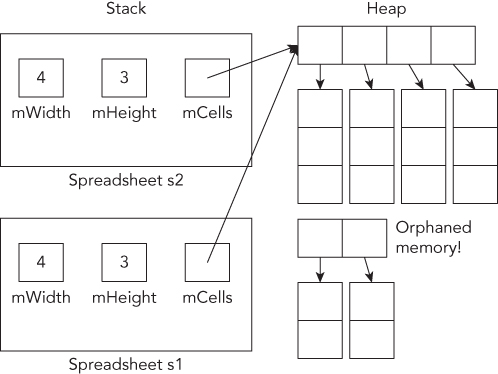

Memory in your C++ application is divided into two parts—the stack and the heap. One way to visualize the stack is as a deck of cards. The current top card represents the current scope of the program, usually the function that is currently being executed. All variables declared inside the current function will take up memory in the top stack frame, the top card of the deck. If the current function, which I’ll call foo(), calls another function bar(), a new card is put on the deck so that bar() has its own stack frame to work with. Any parameters passed from foo() to bar() are copied from the foo() stack frame into the bar() stack frame. Figure 1-2 shows what the stack might look like during the execution of a hypothetical function foo() that has declared two integer values.

Stack frames are nice because they provide an isolated memory workspace for each function. If a variable is declared inside the foo() stack frame, calling the bar() function won’t change it unless you specifically tell it to. Also, when the foo() function is done running, the stack frame goes away, and all of the variables declared within the function no longer take up memory. Variables that are stack-allocated do not need to be deallocated (deleted) by the programmer; it happens automatically.

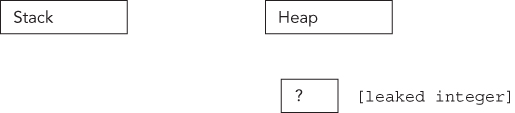

The heap is an area of memory that is completely independent of the current function or stack frame. You can put variables on the heap if you want them to exist even when the function in which they were created has completed. The heap is less structured than the stack. You can think of it as just a pile of bits. Your program can add new bits to the pile at any time or modify bits that are already in the pile. You have to make sure that you deallocate (delete) any memory that you allocated on the heap. This does not happen automatically, unless you use smart pointers, which are discussed in the section “Smart Pointers.”

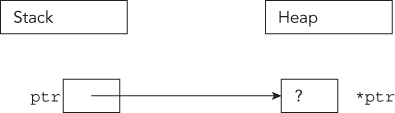

You can put anything on the heap by explicitly allocating memory for it. For example, to put an integer on the heap, you need to allocate memory for it, but first you need to declare a pointer:

int* myIntegerPointer;The * after the int type indicates that the variable you are declaring refers or points to some integer memory. Think of the pointer as an arrow that points at the dynamically allocated heap memory. It does not yet point to anything specific because you haven’t assigned it to anything; it is an uninitialized variable. Uninitialized variables should be avoided at all times, and especially uninitialized pointers because they point to some random place in memory. Working with such pointers will most likely make your program crash. That’s why you should always declare and initialize your pointers at the same time. You can initialize them to a null pointer (nullptr—for more information, see the “Null Pointer Constant” section) if you don’t want to allocate memory right away:

int* myIntegerPointer = nullptr;A null pointer is a special default value that no valid pointer will ever have, and converts to false when used in a Boolean expression. For example:

if (!myIntegerPointer) { /* myIntegerPointer is a null pointer */ }You use the new operator to allocate the memory:

myIntegerPointer = new int;In this case, the pointer points to the address of just a single integer value. To access this value, you need to dereference the pointer. Think of dereferencing as following the pointer’s arrow to the actual value on the heap. To set the value of the newly allocated heap integer, you would use code like the following:

*myIntegerPointer = 8;Notice that this is not the same as setting myIntegerPointer to the value 8. You are not changing the pointer; you are changing the memory that it points to. If you were to reassign the pointer value, it would point to the memory address 8, which is probably random garbage that will eventually make your program crash.

After you are finished with your dynamically allocated memory, you need to deallocate the memory using the delete operator. To prevent the pointer from being used after having deallocated the memory it points to, it’s recommended to set your pointer to nullptr:

delete myIntegerPointer;myIntegerPointer = nullptr;

Pointers don’t always point to heap memory. You can declare a pointer that points to a variable on the stack, even another pointer. To get a pointer to a variable, you use the & (“address of”) operator:

int i = 8;int* myIntegerPointer = &i; // Points to the variable with the value 8

C++ has a special syntax for dealing with pointers to structures. Technically, if you have a pointer to a structure, you can access its fields by first dereferencing it with *, then using the normal. syntax, as in the code that follows, which assumes the existence of a function called getEmployee().

Employee* anEmployee = getEmployee();cout << (*anEmployee).salary << endl;

This syntax is a little messy. The -> (arrow) operator lets you perform both the dereference and the field access in one step. The following code is equivalent to the preceding code, but is easier to read:

Employee* anEmployee = getEmployee();cout << anEmployee->salary << endl;

Remember the concept of short-circuiting logic, which was discussed earlier in this chapter? This can be useful in combination with pointers to avoid using an invalid pointer, as in the following example:

bool isValidSalary = (anEmployee && anEmployee->salary > 0);Or, a little bit more verbose:

bool isValidSalary = (anEmployee != nullptr && anEmployee->salary > 0);anEmployee is only dereferenced to get the salary if it is a valid pointer. If it is a null pointer, the logical operation short-circuits, and the anEmployee pointer is not dereferenced.

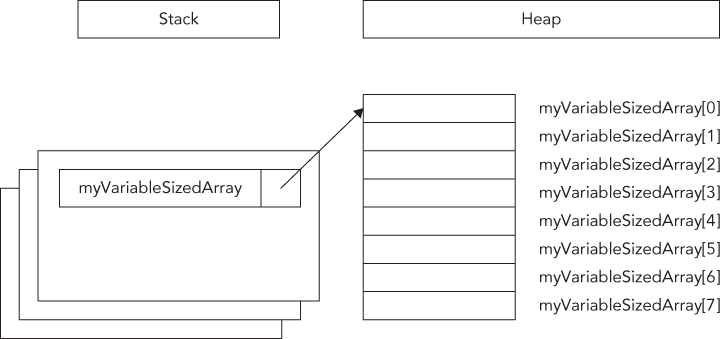

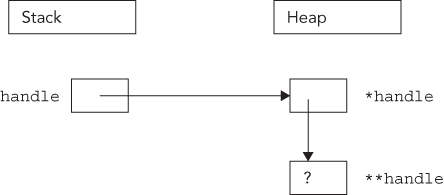

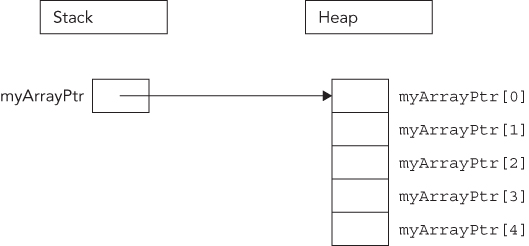

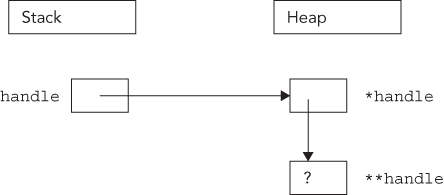

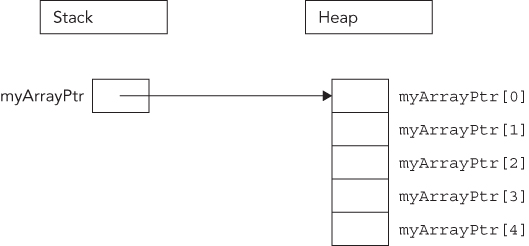

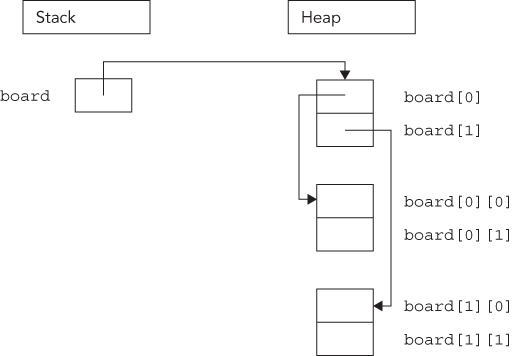

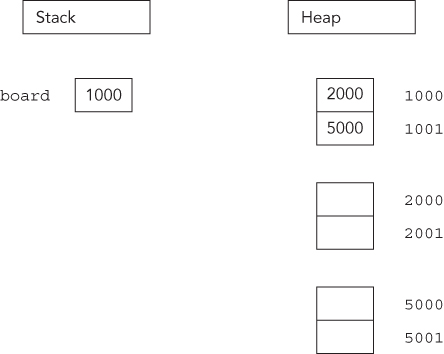

The heap can also be used to dynamically allocate arrays. You use the new[] operator to allocate memory for an array.

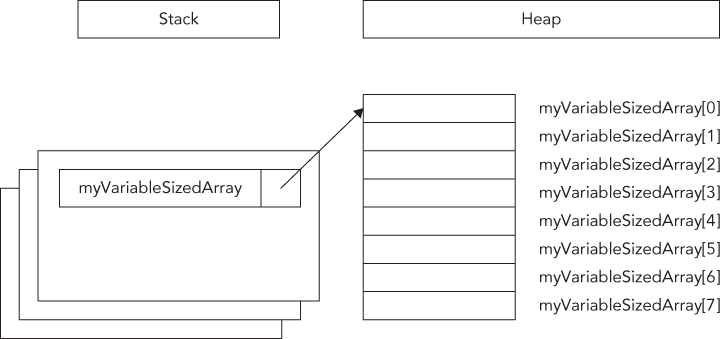

int arraySize = 8;int* myVariableSizedArray = new int[arraySize];

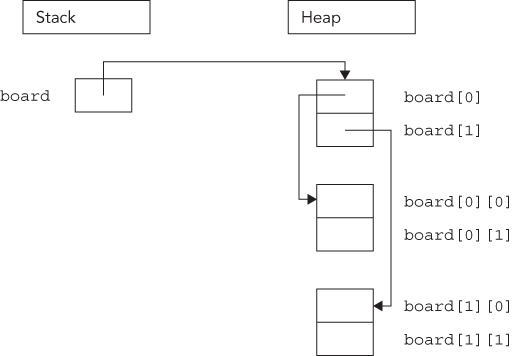

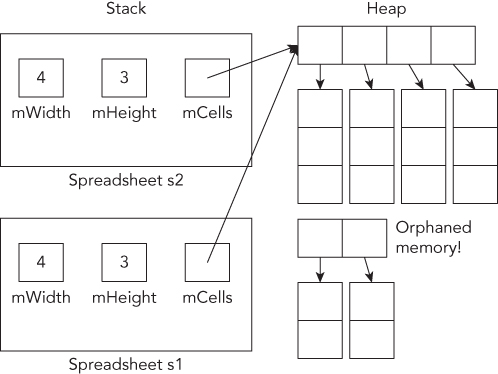

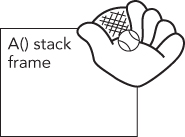

This allocates memory for enough integers to satisfy the arraySize variable. Figure 1-3 shows what the stack and the heap both look like after this code is executed. As you can see, the pointer variable still resides on the stack, but the array that was dynamically created lives on the heap.

Now that the memory has been allocated, you can work with myVariableSizedArray as though it were a regular stack-based array.

myVariableSizedArray[3] = 2;When your code is done with the array, it should remove the array from the heap so that other variables can use the memory. In C++, you use the delete[] operator to do this.

delete[] myVariableSizedArray;myVariableSizedArray = nullptr;

The brackets after delete indicate that you are deleting an array!

Before C++11, the constant NULL was used for null pointers. NULL is simply defined as the constant 0, and this can cause problems. Take the following example:

void func(char* str) {cout << "char* version" << endl;}void func(int i) {cout << "int version" << endl;}int main(){func(NULL);return 0;}

The main() function is calling func() with parameter NULL, which is supposed to be a null pointer constant. In other words, you are expecting the char* version of func() to be called with a null pointer as argument. However, since NULL is not a pointer, but identical to the integer 0, the integer version of func() is called.

This problem is solved with the introduction of a real null pointer constant, nullptr. The following code calls the char* version:

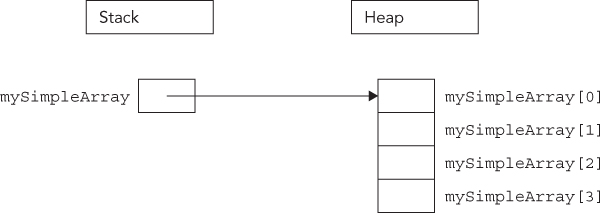

func(nullptr);To avoid common memory problems, you should use smart pointers instead of “raw,” also called “naked,” C-style pointers. Smart pointers automatically deallocate memory when the smart pointer object goes out of scope, for example, when the function has finished executing.

The following are the two most important smart pointer types in C++, both defined in <memory> and in the std namespace:

std::unique_ptrstd::shared_ptrunique_ptr is analogous to an ordinary pointer, except that it automatically frees the memory or resource when the unique_ptr goes out of scope or is deleted. As such, unique_ptr has sole ownership of the object pointed to. One advantage of a unique_ptr is that memory and resources are always freed, even when return statements are executed, or when exceptions (discussed later in this chapter) are thrown. This, for example, simplifies coding when a function has multiple return statements, because you don’t have to remember to free the resources before each return statement.

To create a unique_ptr, you should use std::make_unique<>(). For example, instead of writing the following,

Employee* anEmployee = new Employee;// …delete anEmployee;

you should write this:

auto anEmployee = make_unique<Employee>();Note that you do not call delete anymore; it happens automatically for you. The auto keyword is discussed in more detail in the “Type Inference” section later in this chapter. For now, it suffices to know that the auto keyword tells the compiler to automatically deduce the type of a variable, so that you don’t have to manually specify the full type.

unique_ptr is a generic smart pointer that can point to any kind of memory. That’s why it is a template. Templates require the angle brackets, <

>, to specify the template parameters. Between the brackets, you have to specify the type of memory you want your unique_ptr to point to. Templates are discussed in detail in Chapters 12 and 22, but the smart pointers are introduced in Chapter 1 so that they can be used throughout the book—and as you will see, they are easy to use.

make_unique() has been available since C++14. If your compiler is not yet C++14 compliant, you can make your unique_ptr as follows (note that you now have to specify the type, Employee, twice):

unique_ptr<Employee> anEmployee(new Employee);You can use the anEmployee smart pointer in the same way as a normal pointer, for example:

if (anEmployee) {cout << "Salary: " << anEmployee->salary << endl;}

A unique_ptr can also be used to store a C-style array. The following example creates an array of ten Employee instances, stores it in a unique_ptr, and shows how to access an element from the array:

auto employees = make_unique<Employee[]>(10);cout << "Salary: " << employees[0].salary << endl;

shared_ptr allows for distributed ownership of the data. Each time a shared_ptr is assigned, a reference count is incremented indicating there is one more owner of the data. When a shared_ptr goes out of scope, the reference count is decremented. When the reference count goes to zero, it means there is no longer any owner of the data, and the object referenced by the pointer is freed.

To create a shared_ptr, you should use std::make_shared<>(), which is similar to make_unique<>():

auto anEmployee = make_shared<Employee>();if (anEmployee) {cout << "Salary: " << anEmployee->salary << endl;}

Starting with C++17, you can also store an array in a shared_ptr, whereas older versions of C++ did not allow this. Note however that make_shared<>() of C++17 cannot be used in this case. Here is an example:

shared_ptr<Employee[]> employees(new Employee[10]);cout << "Salary: " << employees[0].salary << endl;

Chapter 7 discusses memory management and smart pointers in more details, but because the basic use of unique_ptr and shared_ptr is straightforward, they are already used in examples throughout this book.

The keyword const can be used in several different ways in C++. All of its uses are related, but there are subtle differences. The subtleties of const make for excellent interview questions! Chapter 11 explains in detail all the ways that const can be used. This section outlines two common use-cases.

If you assumed that the keyword const has something to do with constants, you have correctly uncovered one of its uses. In the C language, programmers often use the preprocessor #define mechanism to declare symbolic names for values that won’t change during the execution of the program, such as the version number. In C++, programmers are encouraged to avoid #define in favor of using const to define constants. Defining a constant with const is just like defining a variable, except that the compiler guarantees that code cannot change the value.

const int versionNumberMajor = 2;const int versionNumberMinor = 1;const std::string productName = "Super Hyper Net Modulator";

In C++, you can cast a non-const variable to a const variable. Why would you want to do this? It offers some degree of protection from other code changing the variable. If you are calling a function that a coworker of yours is writing, and you want to ensure that the function doesn’t change the value of a parameter you pass in, you can tell your coworker to have the function take a const parameter. If the function attempts to change the value of the parameter, it will not compile.

In the following code, a string* is automatically cast to a const string* in the call to mysteryFunction(). If the author of mysteryFunction() attempts to change the value of the passed string, the code will not compile. There are ways around this restriction, but using them requires conscious effort. C++ only protects against accidentally changing const variables.

void mysteryFunction(const std::string* someString){*someString = "Test"; // Will not compile.}int main(){std::string myString = "The string";mysteryFunction(&myString);return 0;}

A reference in C++ allows you to give another name to an existing variable. For example:

int x = 42;int& xReference = x;

Attaching & to a type indicates that the variable is a reference. It is still used as though it was a normal variable, but behind the scenes, it is really a pointer to the original variable. Both the variable x and the reference variable xReference point to exactly the same value. If you change the value through either one of them, the change is visible through the other one as well.