Chapter 13. Indexes and Constraints

Because the focus of this book is on programming techniques, the first 12 chapters

concentrated on elements of the SQL language that you can use to craft powerful select, insert,

update, and delete statements. However, other database features

indirectly affect the code you write. This chapter focuses on

two of those features: indexes and constraints.

Indexes

When you insert a row into a table, the database server does not attempt to put

the data in any particular location within the table. For example, if you add a row

to the department table, the server doesn’t place

the row in numeric order via the dept_id column

or in alphabetical order via the name column.

Instead, the server simply places the data in the next available location within the

file (the server maintains a list of free space for each table). When you query the

department table, therefore, the server will

need to inspect every row of the table to answer the query. For example, let’s say

that you issue the following query:

mysql>SELECT dept_id, name->FROM department->WHERE name LIKE 'A%';+---------+----------------+ | dept_id | name | +---------+----------------+ | 3 | Administration | +---------+----------------+ 1 row in set (0.03 sec)

To find all departments whose name begins with A, the server

must visit each row in the department table and

inspect the contents of the name column; if the

department name begins with A, then the row is added to the

result set. This type of access is known as a table

scan.

While this method works fine for a table with only three rows, imagine how long it

might take to answer the query if the table contains 3 million rows. At some number

of rows larger than three and smaller than 3 million, a line is crossed where the

server cannot answer the query within a reasonable amount of time without additional

help. This help comes in the form of one or more indexes on the

department table.

Even if you have never heard of a database index, you are certainly aware of what an index is (e.g., this book has one). An index is simply a mechanism for finding a specific item within a resource. Each technical publication, for example, includes an index at the end that allows you to locate a specific word or phrase within the publication. The index lists these words and phrases in alphabetical order, allowing the reader to move quickly to a particular letter within the index, find the desired entry, and then find the page or pages on which the word or phrase may be found.

In the same way that a person uses an index to find words within a publication, a database server uses indexes to locate rows in a table. Indexes are special tables that, unlike normal data tables, are kept in a specific order. Instead of containing all of the data about an entity, however, an index contains only the column (or columns) used to locate rows in the data table, along with information describing where the rows are physically located. Therefore, the role of indexes is to facilitate the retrieval of a subset of a table’s rows and columns without the need to inspect every row in the table.

Index Creation

Returning to the department table, you

might decide to add an index on the name

column to speed up any queries that specify a full or partial department name,

as well as any update or delete operations that specify a department name.

Here’s how you can add such an index to a MySQL database:

mysql>ALTER TABLE department->ADD INDEX dept_name_idx (name);Query OK, 3 rows affected (0.08 sec) Records: 3 Duplicates: 0 Warnings: 0

This statement creates an index (a B-tree index to be precise, but more on

this shortly) on the department.name column;

furthermore, the index is given the name dept_name_idx. With the index in place, the query optimizer

(which we discussed in Chapter 3) can choose to use the

index if it is deemed beneficial to do so (with only three rows in the department table, for example, the optimizer might

very well choose to ignore the index and read the entire table). If there is

more than one index on a table, the optimizer must decide which index will be

the most beneficial for a particular SQL statement.

Note

MySQL treats indexes as optional components of a table, which is why you

must use the alter table command to add

or remove an index. Other database servers, including SQL Server and Oracle

Database, treat indexes as independent schema objects. For both SQL Server

and Oracle, therefore, you would generate an index using the create index command, as in:

CREATE INDEX dept_name_idx ON department (name);

As of MySQL version 5.0, a create index

command is available, although it is mapped to the alter table command.

All database servers allow you to look at the available indexes. MySQL users

can use the show command to see all of the

indexes on a specific table, as in:

mysql> SHOW INDEX FROM department \G *************************** 1. row

*************************** 1. row ***************************

Table: department

Non_unique: 0

Key_name: PRIMARY

Seq_in_index: 1

Column_name: dept_id

Collation: A

Cardinality: 3

Sub_part: NULL

Packed: NULL

Null:

Index_type: BTREE

Comment:

Index_Comment:

*************************** 2. row ***************************

Table: department

Non_unique: 1

Key_name: dept_name_idx

Seq_in_index: 1

Column_name: name

Collation: A

Cardinality: 3

Sub_part: NULL

Packed: NULL

Null:

Index_type: BTREE

Comment:

Index_Comment:

2 rows in set (0.01 sec)The output shows that there are two indexes on the department table: one on the dept_id column called PRIMARY,

and the other on the name column called

dept_name_idx. Since I have created only

one index so far (dept_name_idx), you might

be wondering where the other came from; when the department table was created, the create

table statement included a constraint naming the dept_id column as the primary key for the table.

Here’s the statement used to create the table:

CREATE TABLE department

(dept_id SMALLINT UNSIGNED NOT NULL AUTO_INCREMENT,

name VARCHAR(20) NOT NULL,

CONSTRAINT pk_department PRIMARY KEY (dept_id) );When the table was created, the MySQL server automatically generated an index

on the primary key column, which, in this case, is dept_id, and gave the index the name PRIMARY. I cover constraints later in this chapter.

If, after creating an index, you decide that the index is not proving useful, you can remove it via the following:

mysql>ALTER TABLE department->DROP INDEX dept_name_idx;Query OK, 3 rows affected (0.02 sec) Records: 3 Duplicates: 0 Warnings: 0

Note

SQL Server and Oracle Database users must use the drop index command to remove an index, as in:

DROP INDEX dept_name_idx; (Oracle) DROP INDEX dept_name_idx ON department (SQL Server)

MySQL now also supports a drop index

command.

Unique indexes

When designing a database, it is important to consider which columns are

allowed to contain duplicate data and which are not. For example, it is

allowable to have two customers named John Smith in the individual table since each row will have a

different identifier (cust_id), birth

date, and tax number (customer.fed_id) to

help tell them apart. You would not, however, want to allow two departments

with the same name in the department

table. You can enforce a rule against duplicate department names by creating

a unique index on the department.name column.

A unique index plays multiple roles in that, along with providing all the

benefits of a regular index, it also serves as a mechanism for disallowing

duplicate values in the indexed column. Whenever a row is inserted or when

the indexed column is modified, the database server checks the unique index

to see whether the value already exists in another row in the table. Here’s

how you would create a unique index on the department.name column:

mysql>ALTER TABLE department->ADD UNIQUE dept_name_idx (name);Query OK, 3 rows affected (0.04 sec) Records: 3 Duplicates: 0 Warnings: 0

Note

SQL Server and Oracle Database users need only add the unique keyword when creating an index, as

in:

CREATE UNIQUE INDEX dept_name_idx ON department (name);

With the index in place, you will receive an error if you try to add

another department with the name 'Operations':

mysql>INSERT INTO department (dept_id, name)->VALUES (999, 'Operations');ERROR 1062 (23000): Duplicate entry 'Operations' for key 'dept_name_idx'

You should not build unique indexes on your primary key column(s), since the server already checks uniqueness for primary key values. You may, however, create more than one unique index on the same table if you feel that it is warranted.

Multicolumn indexes

Along with the single-column indexes demonstrated thus far, you may build indexes that span multiple columns. If, for example, you find yourself searching for employees by first and last names, you can build an index on both columns together, as in:

mysql>ALTER TABLE employee->ADD INDEX emp_names_idx (lname, fname);Query OK, 18 rows affected (0.10 sec) Records: 18 Duplicates: 0 Warnings: 0

This index will be useful for queries that specify the first and last names or just the last name, but you cannot use it for queries that specify only the employee’s first name. To understand why, consider how you would find a person’s phone number; if you know the person’s first and last names, you can use a phone book to find the number quickly, since a phone book is organized by last name and then by first name. If you know only the person’s first name, you would need to scan every entry in the phone book to find all the entries with the specified first name.

When building multiple-column indexes, therefore, you should think carefully about which column to list first, which column to list second, and so on so that the index is as useful as possible. Keep in mind, however, that there is nothing stopping you from building multiple indexes using the same set of columns but in a different order if you feel that it is needed to ensure adequate response time.

Types of Indexes

Indexing is a powerful tool, but since there are many different types of data, a single indexing strategy doesn’t always do the job. The following sections illustrate the different types of indexing available from various servers.

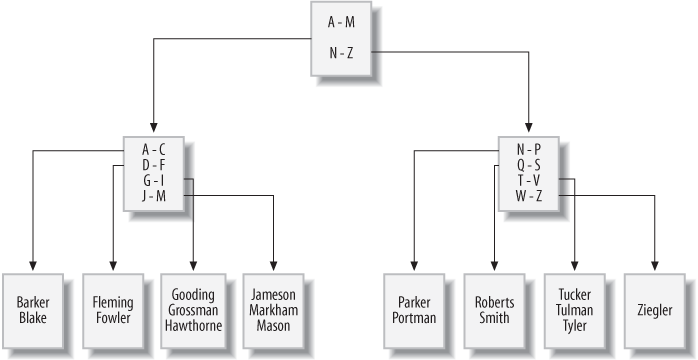

B-tree indexes

All the indexes shown thus far are balanced-tree

indexes, which are more commonly known as B-tree

indexes. MySQL, Oracle Database, and SQL Server all default

to B-tree indexing, so you will get a B-tree index unless you explicitly ask

for another type. As you might expect, B-tree indexes are organized as

trees, with one or more levels of branch nodes leading

to a single level of leaf nodes. Branch nodes are used

for navigating the tree, while leaf nodes hold the actual values and

location information. For example, a B-tree index built on the employee.lname column might look something

like Figure 13-1.

If you were to issue a query to retrieve all employees whose last name

starts with G, the server would look at the top branch

node (called the root node) and follow the link to the

branch node that handles last names beginning with A

through M. This branch node would, in turn, direct the

server to a leaf node containing last names beginning with

G through I. The server then

starts reading the values in the leaf node until it encounters a value that

doesn’t begin with G (which, in this case, is 'Hawthorne').

As rows are inserted, updated, and deleted from the employee table, the server will attempt to

keep the tree balanced so that there aren’t far more branch/leaf nodes on

one side of the root node than the other. The server can add or remove

branch nodes to redistribute the values more evenly and can even add or

remove an entire level of branch nodes. By keeping the tree balanced, the

server is able to traverse quickly to the leaf nodes to find the desired

values without having to navigate through many levels of branch

nodes.

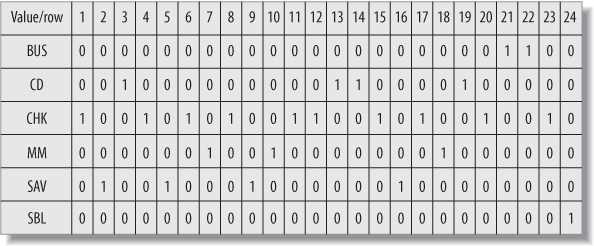

Bitmap indexes

Although B-tree indexes are great at handling columns that contain many

different values, such as a customer’s first/last names, they can become

unwieldy when built on a column that allows only a small number of values.

For example, you may decide to generate an index on the account.product_cd column so that you can

quickly retrieve all accounts of a specific type (e.g., checking, savings).

Because there are only eight different products, however, and because some

products are far more popular than others, it can be difficult to maintain a

balanced B-tree index as the number of accounts grows.

For columns that contain only a small number of values across a large

number of rows (known as low-cardinality data), a

different indexing strategy is needed. To handle this situation more

efficiently, Oracle Database includes bitmap indexes,

which generate a bitmap for each value stored in the column. Figure 13-2 shows what a bitmap index might look like for

data in the account.product_cd

column.

The index contains six bitmaps, one for each value in the product_cd column (two of the eight available

products are not being used), and each bitmap includes a 0/1 value

for each of the 24 rows in the account

table. Thus, if you ask the server to retrieve all money market accounts

(product_cd = 'MM'), the server

simply finds all the 1 values in the

MM bitmap and returns rows 7, 10, and

18. The server can also combine bitmaps if you are looking for multiple

values; for example, if you want to retrieve all money market

and savings accounts (product_cd = 'MM' or product_cd =

'SAV'), the server can perform an OR operation on the MM and

SAV bitmaps and return rows 2, 5, 7,

9, 10, 16, and 18.

Bitmap indexes are a nice, compact indexing solution for low-cardinality data, but this indexing strategy breaks down if the number of values stored in the column climbs too high in relation to the number of rows (known as high-cardinality data), since the server would need to maintain too many bitmaps. For example, you would never build a bitmap index on your primary key column, since this represents the highest possible cardinality (a different value for every row).

Oracle users can generate bitmap indexes by simply adding the bitmap keyword to the create index statement, as in:

CREATE BITMAP INDEX acc_prod_idx ON account (product_cd);

Bitmap indexes are commonly used in data warehousing environments, where large amounts of data are generally indexed on columns containing relatively few values (e.g., sales quarters, geographic regions, products, salespeople).

Text indexes

If your database stores documents, you may need to allow users to search for words or phrases in the documents. You certainly don’t want the server to open each document and scan for the desired text each time a search is requested, but traditional indexing strategies don’t work for this situation. To handle this situation, MySQL, SQL Server, and Oracle Database include specialized indexing and search mechanisms for documents; both SQL Server and MySQL include what they call full-text indexes (for MySQL, full-text indexes are available only with its MyISAM storage engine), and Oracle Database includes a powerful set of tools known as Oracle Text. Document searches are specialized enough that I refrain from showing an example, but I wanted you to at least know what is available.

How Indexes Are Used

Indexes are generally used by the server to quickly locate rows in a particular table, after which the server visits the associated table to extract the additional information requested by the user. Consider the following query:

mysql>SELECT emp_id, fname, lname->FROM employee->WHERE emp_id IN (1, 3, 9, 15);+--------+---------+----------+ | emp_id | fname | lname | +--------+---------+----------+ | 1 | Michael | Smith | | 3 | Robert | Tyler | | 9 | Jane | Grossman | | 15 | Frank | Portman | +--------+---------+----------+ 4 rows in set (0.00 sec)

For this query, the server can use the primary key index on the emp_id column to locate employee IDs 1, 3, 9, and

15 in the employee table, and then visit each

of the four rows to retrieve the first and last name columns.

If the index contains everything needed to satisfy the query, however, the server doesn’t need to visit the associated table. To illustrate, let’s look at how the query optimizer approaches the same query with different indexes in place.

The query, which aggregates account balances for specific customers, looks as follows:

mysql>SELECT cust_id, SUM(avail_balance) tot_bal->FROM account->WHERE cust_id IN (1, 5, 9, 11)->GROUP BY cust_id;+---------+----------+ | cust_id | tot_bal | +---------+----------+ | 1 | 4557.75 | | 5 | 2237.97 | | 9 | 10971.22 | | 11 | 9345.55 | +---------+----------+ 4 rows in set (0.00 sec)

To see how MySQL’s query optimizer decides to execute the query, I use the

explain statement to ask the server to

show the execution plan for the query rather than executing the query:

mysql>EXPLAIN SELECT cust_id, SUM(avail_balance) tot_bal->FROM account->WHERE cust_id IN (1, 5, 9, 11)->GROUP BY cust_id \G*************************** 1. row *************************** id: 1 select_type: SIMPLE table: account type: index possible_keys: fk_a_cust_id key: fk_a_cust_id key_len: 4 ref: NULL rows: 24 Extra: Using where 1 row in set (0.00 sec)

Note

Each database server includes tools to allow you to see how the query

optimizer handles your SQL statement. SQL Server allows you to see an

execution plan by issuing the statement set

showplan_text on before running your SQL statement. Oracle

Database includes the explain plan

statement, which writes the execution plan to a special table called

plan_table.

Without going into too much detail, here’s what the execution plan tells you:

The

fk_a_cust_idindex is used to find the rows in theaccounttable that satisfy thewhereclause.After reading the index, the server expects to read all 24 rows of the

accounttable to gather the available balance data, since it doesn’t know that there might be other customers besides IDs 1, 5, 9, and 11.

The fk_a_cust_id index is another index

generated automatically by the server, but this time it is because of a foreign

key constraint rather than a primary key constraint (more on this later in the

chapter). The fk_a_cust_id index is built on

the account.cust_id column, so the server is

using the index to locate customer IDs 1, 5, 9, and 11 in the account table and is then visiting those rows to

retrieve and aggregate the available balance data.

Next, I will add a new index called acc_bal_idx on both the cust_id and avail_balance columns:

mysql>ALTER TABLE account->ADD INDEX acc_bal_idx (cust_id, avail_balance);Query OK, 24 rows affected (0.03 sec) Records: 24 Duplicates: 0 Warnings: 0

With this index in place, let’s see how the query optimizer approaches the same query:

mysql>EXPLAIN SELECT cust_id, SUM(avail_balance) tot_bal->FROM account->WHERE cust_id IN (1, 5, 9, 11)->GROUP BY cust_id \G*************************** 1. row *************************** id: 1 select_type: SIMPLE table: account type: range possible_keys: acc_bal_idx key: acc_bal_idx key_len: 4 ref: NULL rows: 8 Extra: Using where; Using index 1 row in set (0.01 sec)

Comparing the two execution plans yields the following differences:

The optimizer is using the new

acc_bal_idxindex instead of thefk_a_cust_idindex.The optimizer anticipates needing only eight rows instead of 24.

The

accounttable is not needed (designated byUsing indexin theExtracolumn) to satisfy the query results.

Therefore, the server can use indexes to help locate rows in the associated table, or the server can use an index as though it were a table as long as the index contains all the columns needed by the query.

Note

The process that I just led you through is an example of query tuning. Tuning involves looking at an SQL statement and determining the resources available to the server to execute the statement. You can decide to modify the SQL statement, to adjust the database resources, or to do both in order to make a statement run more efficiently. Tuning is a detailed topic, and I strongly urge you to either read your server’s tuning guide or pick up a good tuning book so that you can see all the different approaches available for your server.

The Downside of Indexes

If indexes are so great, why not index everything? Well, the key to understanding why more indexes are not necessarily a good thing is to keep in mind that every index is a table (a special type of table, but still a table). Therefore, every time a row is added to or removed from a table, all indexes on that table must be modified. When a row is updated, any indexes on the column or columns that were affected need to be modified as well. Therefore, the more indexes you have, the more work the server needs to do to keep all schema objects up-to-date, which tends to slow things down.

Indexes also require disk space as well as some amount of care from your administrators, so the best strategy is to add an index when a clear need arises. If you need an index for only special purposes, such as a monthly maintenance routine, you can always add the index, run the routine, and then drop the index until you need it again. In the case of data warehouses, where indexes are crucial during business hours as users run reports and ad hoc queries but are problematic when data is being loaded into the warehouse overnight, it is a common practice to drop the indexes before data is loaded and then re-create them before the warehouse opens for business.

In general, you should strive to have neither too many indexes nor too few. If you aren’t sure how many indexes you should have, you can use this strategy as a default:

Make sure all primary key columns are indexed (most servers automatically create unique indexes when you create primary key constraints). For multicolumn primary keys, consider building additional indexes on a subset of the primary key columns, or on all the primary key columns but in a different order than the primary key constraint definition.

Build indexes on all columns that are referenced in foreign key constraints. Keep in mind that the server checks to make sure there are no child rows when a parent is deleted, so it must issue a query to search for a particular value in the column. If there’s no index on the column, the entire table must be scanned.

Index any columns that will frequently be used to retrieve data. Most date columns are good candidates, along with short (3- to 50-character) string columns.

After you have built your initial set of indexes, try to capture actual queries against your tables, and modify your indexing strategy to fit the most-common access paths.

Constraints

A constraint is simply a restriction placed on one or more columns of a table. There are several different types of constraints, including:

- Primary key constraints

Identify the column or columns that guarantee uniqueness within a table

- Foreign key constraints

Restrict one or more columns to contain only values found in another table’s primary key columns, and may also restrict the allowable values in other tables if

update cascadeordelete cascaderules are established- Unique constraints

Restrict one or more columns to contain unique values within a table (primary key constraints are a special type of unique constraint)

- Check constraints

Without constraints, a database’s consistency is suspect. For example, if the

server allows you to change a customer’s ID in the customer table without changing the same customer ID in the account table, then you will end up with accounts that

no longer point to valid customer records (known as orphaned

rows). With primary and foreign key constraints in place, however,

the server will either raise an error if an attempt is made to modify or delete data

that is referenced by other tables, or propagate the changes to other tables for you

(more on this shortly).

Note

If you want to use foreign key constraints with the MySQL server, you must use the InnoDB storage engine for your tables. Foreign key constraints are not supported in the Falcon engine as of version 6.0.4, but they will be supported in later versions.

Constraint Creation

Constraints are generally created at the same time as the associated table via

the create table statement. To illustrate,

here’s an example from the schema generation script for this book’s example

database:

CREATE TABLE product

(product_cd VARCHAR(10) NOT NULL,

name VARCHAR(50) NOT NULL,

product_type_cd VARCHAR (10) NOT NULL,

date_offered DATE,

date_retired DATE,

CONSTRAINT fk_product_type_cd FOREIGN KEY (product_type_cd)

REFERENCES product_type (product_type_cd),

CONSTRAINT pk_product PRIMARY KEY (product_cd)

);The product table includes two constraints:

one to specify that the product_cd column

serves as the primary key for the table, and another to specify that the

product_type_cd

column serves as a foreign key to the product_type table. Alternatively, you can create the product table without constraints, and add the

primary and foreign key constraints later via alter

table statements:

ALTER TABLE product ADD CONSTRAINT pk_product PRIMARY KEY (product_cd); ALTER TABLE product ADD CONSTRAINT fk_product_type_cd FOREIGN KEY (product_type_cd) REFERENCES product_type (product_type_cd);

If you want to remove a primary or foreign key constraint, you can use the

alter table statement again, except that

you specify drop instead of add, as in:

ALTER TABLE product DROP PRIMARY KEY; ALTER TABLE product DROP FOREIGN KEY fk_product_type_cd;

While it is unusual to drop a primary key constraint, foreign key constraints are sometimes dropped during certain maintenance operations and then reestablished.

Constraints and Indexes

As you saw earlier in the chapter, constraint creation sometimes involves the automatic generation of an index. However, database servers behave differently regarding the relationship between constraints and indexes. Table 13-1 shows how MySQL, SQL Server, and Oracle Database handle the relationship between constraints and indexes.

|

Constraint type |

MySQL |

SQL Server |

Oracle Database |

|

Primary key constraints |

Generates unique index |

Generates unique index |

Uses existing index or creates new index |

|

Foreign key constraints |

Generates index |

Does not generate index |

Does not generate index |

|

Unique constraints |

Generates unique index |

Generates unique index |

Uses existing index or creates new index |

MySQL, therefore, generates a new index to enforce primary key, foreign key, and unique constraints, SQL Server generates a new index for primary key and unique constraints but not for foreign key constraints, and Oracle Database takes the same approach as SQL Server except that Oracle will use an existing index (if an appropriate one exists) to enforce primary key and unique constraints. Although neither SQL Server nor Oracle Database generates an index for a foreign key constraint, both servers’ documentation advises that indexes be created for every foreign key.

Cascading Constraints

With foreign key constraints in place, if a user attempts to insert a new row

or change an existing row such that a foreign key column doesn’t have a matching

value in the parent table, the server raises an error. To illustrate, here’s a

look at the data in the product and product_type tables:

mysql>SELECT product_type_cd, name->FROM product_type;+-----------------+-------------------------------+ | product_type_cd | name | +-----------------+-------------------------------+ | ACCOUNT | Customer Accounts | | INSURANCE | Insurance Offerings | | LOAN | Individual and Business Loans | +-----------------+-------------------------------+ 3 rows in set (0.00 sec) mysql>SELECT product_type_cd, product_cd, name->FROM product->ORDER BY product_type_cd;+-----------------+------------+-------------------------+ | product_type_cd | product_cd | name | +-----------------+------------+-------------------------+ | ACCOUNT | CD | certificate of deposit | | ACCOUNT | CHK | checking account | | ACCOUNT | MM | money market account | | ACCOUNT | SAV | savings account | | LOAN | AUT | auto loan | | LOAN | BUS | business line of credit | | LOAN | MRT | home mortgage | | LOAN | SBL | small business loan | +-----------------+------------+-------------------------+ 8 rows in set (0.01 sec)

There are three different values for the product_type_cd column in the product_type table (ACCOUNT,

INSURANCE, and LOAN). Of the three values, two of them (ACCOUNT and LOAN) are

referenced in the product table’s product_type_cd column.

The following statement attempts to change the product_type_cd column in the product table to a value that doesn’t exist

in the product_type table:

mysql>UPDATE product->SET product_type_cd = 'XYZ'->WHERE product_type_cd = 'LOAN';ERROR 1452 (23000): Cannot add or update a child row: a foreign key constraint fails ('bank'.'product', CONSTRAINT 'fk_product_type_cd' FOREIGN KEY ('product_type_cd') REFERENCES 'product_type' ('product_type_cd'))

Because of the foreign key constraint on the product.product_type_cd column, the server does not allow the

update to succeed, since there is no row in the product_type table with a value of XYZ in the product_type_cd column. Thus, the foreign key constraint doesn’t

let you change a child row if there is no corresponding value in the

parent.

What would happen, however, if you tried to change the

parent row in the product_type table to XYZ? Here’s an update statement that attempts to change the LOAN product type to XYZ:

mysql>UPDATE product_type->SET product_type_cd = 'XYZ'->WHERE product_type_cd = 'LOAN';ERROR 1451 (23000): Cannot delete or update a parent row: a foreign key constraint fails ('bank'.'product', CONSTRAINT 'fk_product_type_cd' FOREIGN KEY ('product_type_cd') REFERENCES 'product_type' ('product_type_cd'))

Once again, an error is raised; this time because there are child rows in the

product table whose product_type_cd column contains the value LOAN. This is the default behavior for foreign key

constraints, but it is not the only possible behavior; instead, you can instruct

the server to propagate the change to all child rows for you, thus preserving

the integrity of the data. Known as a cascading update,

this variation of the foreign key constraint can be installed by removing the

existing foreign key and adding a new one that includes the on update cascade clause:

mysql>ALTER TABLE product->DROP FOREIGN KEY fk_product_type_cd;Query OK, 8 rows affected (0.02 sec) Records: 8 Duplicates: 0 Warnings: 0 mysql>ALTER TABLE product->ADD CONSTRAINT fk_product_type_cd FOREIGN KEY (product_type_cd)->REFERENCES product_type (product_type_cd)->ON UPDATE CASCADE;Query OK, 8 rows affected (0.03 sec) Records: 8 Duplicates: 0 Warnings: 0

With this modified constraint in place, let’s see what happens when the

previous update statement is attempted

again:

mysql>UPDATE product_type->SET product_type_cd = 'XYZ'->WHERE product_type_cd = 'LOAN';Query OK, 1 row affected (0.01 sec) Rows matched: 1 Changed: 1 Warnings: 0

This time, the statement succeeds. To verify that the change was propagated to

the product table, here’s another look at the

data in both tables:

mysql>SELECT product_type_cd, name->FROM product_type;+-----------------+-------------------------------+ | product_type_cd | name | +-----------------+-------------------------------+ | ACCOUNT | Customer Accounts | | INSURANCE | Insurance Offerings | | XYZ | Individual and Business Loans | +-----------------+-------------------------------+ 3 rows in set (0.02 sec) mysql>SELECT product_type_cd, product_cd, name->FROM product->ORDER BY product_type_cd;+-----------------+------------+-------------------------+ | product_type_cd | product_cd | name | +-----------------+------------+-------------------------+ | ACCOUNT | CD | certificate of deposit | | ACCOUNT | CHK | checking account | | ACCOUNT | MM | money market account | | ACCOUNT | SAV | savings account | | XYZ | AUT | auto loan | | XYZ | BUS | business line of credit | | XYZ | MRT | home mortgage | | XYZ | SBL | small business loan | +-----------------+------------+-------------------------+ 8 rows in set (0.01 sec)

As you can see, the change to the product_type table has been propagated to the product table as well. Along

with cascading updates, you can specify cascading deletes

as well. A cascading delete removes rows from the child

table when a row is deleted from the parent table. To specify cascading deletes,

use the on delete cascade clause, as

in:

ALTER TABLE product ADD CONSTRAINT fk_product_type_cd FOREIGN KEY (product_type_cd) REFERENCES product_type (product_type_cd) ON UPDATE CASCADE ON DELETE CASCADE;

With this version of the constraint in place, the server will now update child

rows in the product table when a row in the

product_type table is updated, as well as

delete child rows in the product table when a

row in the product_type table is

deleted.

Cascading constraints are one case in which constraints

do directly affect the code that you write. You need to

know which constraints in your database specify cascading updates and/or deletes

so that you know the full effect of your update and delete

statements.

Test Your Knowledge

Work through the following exercises to test your knowledge of indexes and constraints. When you’re done, compare your solutions with those in Appendix C.

Exercise 13-1

Modify the account table so that customers

may not have more than one account for each product.

Exercise 13-2

Generate a multicolumn index on the transaction table that could be used by both of the following

queries:

SELECT txn_date, account_id, txn_type_cd, amount

FROM transaction

WHERE txn_date > cast('2008-12-31 23:59:59' as datetime);

SELECT txn_date, account_id, txn_type_cd, amount

FROM transaction

WHERE txn_date > cast('2008-12-31 23:59:59' as datetime)

AND amount < 1000;