Chapter 1: Build a Basic CRUD App with Vue.js, Node and MongoDB

by James Hibbard

Most web applications need to persist data in one form or other. When working with a server-side language, this is normally a straightforward task. However, when you add a front-end JavaScript framework to the mix, things start to get a bit trickier.

In this tutorial, I’m going to show you how to build a simple CRUD app (Create, Read, Update and Delete) using Node, MongoDB and Vue. I’ll walk you through getting all of the pieces set up and demo each of the CRUD operations. After reading, you’ll be left with a fully functional app that you can adapt to your own purposes. You’ll also able to use this approach in projects of your own.

As the world really doesn’t need another to-do list, we’ll be building an app to help students of a foreign language learn vocabulary. As you might notice from my author bio, I’m a Brit living in Germany and this is something I wish I’d had 20 years ago.

You can check out the finished product in this GitHub repo. And if you’re stuck for German words at any point, try out some of these.

Install the Tooling

In this section, we’ll install the tools we’ll need to create our app. These are Node, npm, MongoDB, MongoDB Compass (optional) and Postman. I won’t go too into depth on the various installation instructions, but if you have any trouble getting set up, please visit our forums and ask for help there.

Node.js

Many websites will recommend that you head to the official Node download page and grab the Node binaries for your system. While that works, I’d suggest using a version manager (such as nvm) instead. This is a program which allows you to install multiple versions of Node and switch between them at will. If you’d like to find out more about this, please consult our quick tip, Install Multiple Versions of Node.js Using nvm.

npm

npm is a JavaScript package manager which comes bundled with Node, so no extra installation is necessary here. We’ll be making quite extensive use of npm throughout this tutorial, so if you’re in need of a refresher, please consult A Beginner’s Guide to npm — the Node Package Manager.

MongoDB

MongoDB is a document database which stores data in flexible, JSON-like documents.

The quickest way to get up and running with Mongo is to use a service such as mLabs. They have a free sandbox plan which provides a single database with 496MB of storage running on a shared virtual machine. This is more than adequate for a simple app with a handful of users. If this sounds like the best option for you, please consult their quick start guide.

You can also install Mongo locally. To do this, please visit the official download page and download the correct version of the community server for your operating system. There’s a link to detailed, OS-specific installation instructions next to the download link.

A MongoDB GUI

Although not strictly necessary for following along with this tutorial, you might also like to install Compass, the official GUI for MongoDB. This tool helps you visualize and manipulate your data, allowing you to interact with documents with full CRUD functionality.

At the time of writing, you’ll need to fill out your details to download Compass, but you won’t need to create an account.

Postman

This is an extremely useful tool for working with and testing APIs. You can download the correct version for your OS from the project’s home page. You can find OS-specific installation instructions here.

Check That Everything Is Installed Correctly

To check that Node and npm are installed correctly, open your terminal and type this:

node -v

Follow that with this:

npm -v

This will output the version number of each program (11.1.0 and 6.4.1 respectively at the time of writing).

If you installed Mongo locally, you can check the version number using this:

mongo --version

This should output a bunch of information, including the version number (4.0.4 at the time of writing).

Check the Database Connection Using Compass

If you have installed Mongo locally, you start the server by typing the following command into a terminal:

mongod

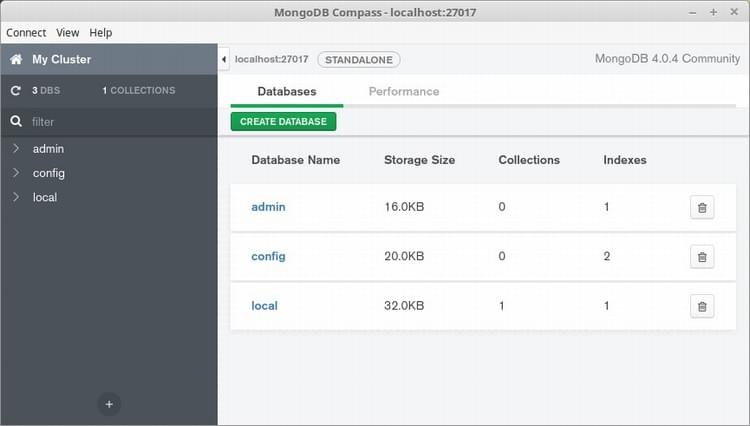

Next, open Compass. You should be able to accept the defaults (Hostname: localhost, Port: 27017), press the CONNECT button, and establish a connection to the database server.

Note that the databases admin, config and local are created automatically.

Using a Cloud-hosted Solution

If you’re using mLabs, create a database subscription (as described in their quick-start guide), then copy the connection details to the clipboard. This should be in the following form:

mongodb://<dbuser>:<dbpassword>@<instance>.mlab.com:<port>/<dbname>

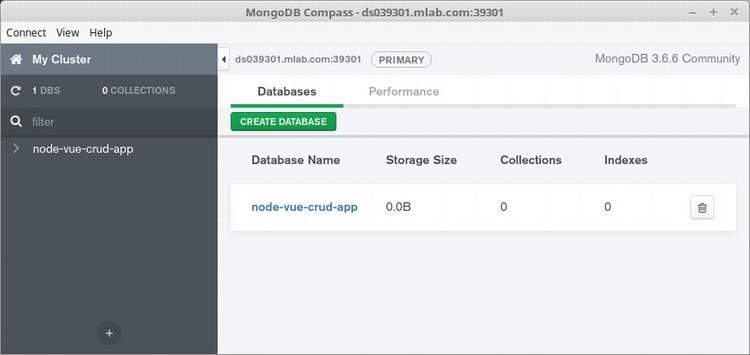

When you open Compass, it will inform you that it has detected a MongoDB connection string and asks if you’d like to use it to fill out the form. Click Yes, then click CONNECT and you should be off to the races.

Note that I called my database node-vue-crud-app. You can call yours what you like.

Creating the Node Back End

In this section, we’ll create a RESTful API for our Vue front end to consume and test it using Postman. I don’t want to go into too much detail on how a RESTful API works, as the focus of this guide should be the Vue front end. If you’d like a more in-depth tutorial, there are plenty on the Internet. I found that Build Node.js RESTful APIs in 10 Minutes was quite easy to follow, and it served as inspiration for the code in this section.

Basic Setup

First, let’s create the files and directories we’ll need and initialize the project:

mkdir -p vocab-builder/server/api/{controllers,models,routes}

cd vocab-builder/server

touch server.js

touch api/controllers/vocabController.js

touch api/models/vocabModel.js

touch api/routes/vocabRoutes.js

npm init -y

This should give us the following folder structure:

.

└── server

├── api

│ ├── controllers

│ │ └── vocabController.js

│ ├── models

│ │ └── vocabModel.js

│ └── routes

│ └── vocabRoutes.js

├── package.json

└── server.js

Install the Dependencies

For our API, we’ll be using the following libraries:

- express—a small framework for Node that provides many useful features, such as routing and middleware.

- cors—Express middleware that can be used to enable CORS in our project.

- body-parser—Express middleware to parse the body of incoming requests.

- mongoose—a MongoDB ODM (the NoSQL equivalent of an ORM) for Node. It provides a simple validation and query API to help you interact with your MongoDB database.

- nodemon—a simple monitor script which will automatically restart a Node application when file changes are detected.

Let’s get them installed:

npm i express cors body-parser mongoose

npm i nodemon --save-dev

Next, open up package.json and alter the scripts section to read as follows:

"scripts": {

"start": "nodemon server.js"

},

And that’s the setup done.

Create the Server

Open up server.js and add the following code:

const express = require('express');

const port = process.env.PORT || 3000;

const app = express();

app.listen(port);

app.get('/', (req, res) => {

res.send('Hello, World!');

});

console.log(`Server started on port ${port}`);

Then hop into the terminal and run npm run start. You should see a message that the server has started on port 3000. If you visit http://localhost:3000/, you should see “Hello, World!” displayed.

Define a Schema

Next, we need to define what the data should look like in our database. Essentially I wish to have two fields per document, english and german, to hold the English and German translations of a word. I’d also like to apply some simple validation and ensure that neither of these fields can be empty.

Open up api/models/vocabModel.js and add the following code:

const mongoose = require('mongoose');

const { Schema } = mongoose;

const VocabSchema = new Schema(

{

english: {

type: String,

required: 'English word cannot be blank'

},

german: {

type: String,

required: 'German word cannot be blank'

}

},

{ collection: 'vocab' }

);

module.exports = mongoose.model('Vocab', VocabSchema);

Note that I’m also specifying the name of the collection I wish to create, as otherwise Mongoose will attempt to name it “vocabs”, which is silly.

Setting Up the Routes

Next we have to specify how our API should respond to requests from the outside world. We’re going to create the following endpoints:

- GET

/words—return a list of all words - POST

/words—create a new word - GET

/words/:wordId—get a single word - PUT

/words/:wordId—update a single word - DELETE

/words/:wordId—delete a single word

To do this, open up api/routes/vocabRoutes.js and add the following:

const vocabBuilder = require('../controllers/vocabController');

module.exports = app => {

app

.route('/words')

.get(vocabBuilder.list_all_words)

.post(vocabBuilder.create_a_word);

app

.route('/words/:wordId')

.get(vocabBuilder.read_a_word)

.put(vocabBuilder.update_a_word)

.delete(vocabBuilder.delete_a_word);

};

You’ll notice that we’re requiring the vocabController at the top of the file. This will contain the actual logic to handle the requests. Let’s implement that now.

Creating the Controller

Open up api/controllers/vocabController.js and add the following code:

const mongoose = require('mongoose');

const Vocab = mongoose.model('Vocab');

exports.list_all_words = (req, res) => {

Vocab.find({}, (err, words) => {

if (err) res.send(err);

res.json(words);

});

};

exports.create_a_word = (req, res) => {

const newWord = new Vocab(req.body);

newWord.save((err, word) => {

if (err) res.send(err);

res.json(word);

});

};

exports.read_a_word = (req, res) => {

Vocab.findById(req.params.wordId, (err, word) => {

if (err) res.send(err);

res.json(word);

});

};

exports.update_a_word = (req, res) => {

Vocab.findOneAndUpdate(

{ _id: req.params.wordId },

req.body,

{ new: true },

(err, word) => {

if (err) res.send(err);

res.json(word);

}

);

};

exports.delete_a_word = (req, res) => {

Vocab.deleteOne({ _id: req.params.wordId }, err => {

if (err) res.send(err);

res.json({

message: 'Word successfully deleted',

_id: req.params.wordId

});

});

};

Here we’re importing our model, then defining five functions corresponding to the desired CRUD functionality. If you’re unsure as to what any of these functions do or how they work, please consult the Mongoose documentation.

Wiring Everything Together

Now all of the pieces are in place and the time has come to wire them together. Hop back into server.js and replace the existing code with the following:

const express = require('express');

const cors = require('cors');

const mongoose = require('mongoose');

const bodyParser = require('body-parser');

global.Vocab = require('./api/models/vocabModel');

const routes = require('./api/routes/vocabRoutes');

mongoose.Promise = global.Promise;

mongoose.set('useFindAndModify', false);

mongoose.connect(

'mongodb://localhost/vocab-builder',

{ useNewUrlParser: true }

);

const port = process.env.PORT || 3000;

const app = express();

app.use(cors());

app.use(bodyParser.urlencoded({ extended: true }));

app.use(bodyParser.json());

routes(app);

app.listen(port);

app.use((req, res) => {

res.status(404).send({ url: `${req.originalUrl} not found` });

});

console.log(`Server started on port ${port}`);

Here we start off by requiring the necessary libraries, as well as our model and routes files. We then use Mongoose’s connect method to connect to our database (don’t forget to make sure MongoDB is running if you installed it locally), before creating a new Express app and telling it to use the bodyParser and cors middleware. We then tell it to use the routes we defined in api/routes/vocabRoutes.js and to listen for connections on port 3000. Finally, we define a function to deal with nonexistent routes.

You can test this is working by hitting http://localhost:3000/ in your browser. You should no longer see a “Hello, World!” message, but rather {"url":"/ not found"}.

Also, please note that if you’re using mLabs, you’ll need to replace:

mongoose.connect(

'mongodb://localhost/vocab-builder',

{ useNewUrlParser: true }

);

with the details you received when creating your database:

mongoose.connect(

'mongodb://<dbuser>:<dbpassword>@<instance>.mlab.com:<port>/<dbname>',

{ useNewUrlParser: true }

);

Testing the API with Postman

To test the API, start up Postman. How you do this will depend on how you installed it.

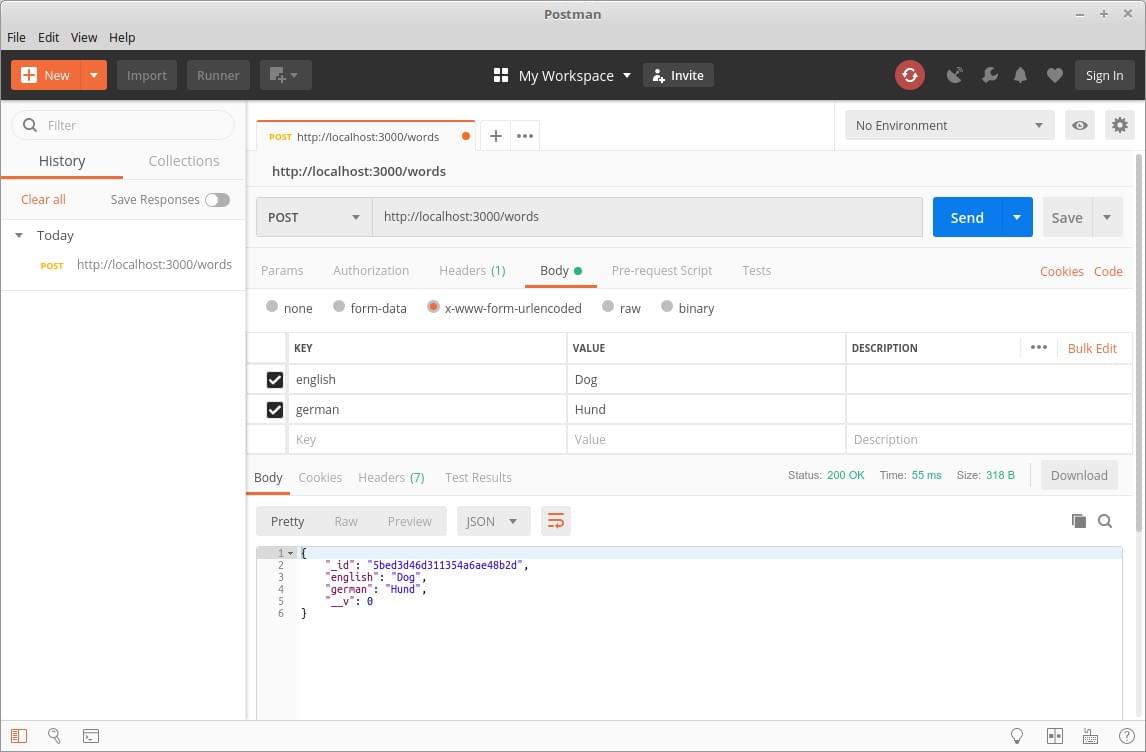

Create

We’ll start off by creating a new word pair. Select POST as the method and enter http://localhost:3000/words as the URL. Select the Body tab and the radio button x-www-form-urlencoded, then enter two key/value pairs into the fields below. Press Send and you should receive the newly created object from the server by way of a response.

At this point, you can also view the database using Compass, to assure yourself that the collection was created with the correct entry.

Read

To test the read functionality of our API, we’ll first attempt to get all words in our collection, then an individual word.

To get all of the words, change the method to GET and Body to none. Then hit Send. The response should be similar to this:

[

{

"_id": "5bed3d46d311354a6ae48b2d",

"english": "Dog",

"german": "Hund",

"__v": 0

}

]

Copy the _id value of the first word returned and change the URL to http://localhost:3000/words/<_id>. For me this would be:

http://localhost:3000/words/5bed3d46d311354a6ae48b2d

Hit Send again to retrieve just that word from our API. The response should be similar to this:

{

"_id": "5bed3d46d311354a6ae48b2d",

"english": "Dog",

"german": "Hund",

"__v": 0

}

Notice that now just the object is returned, not an array of objects.

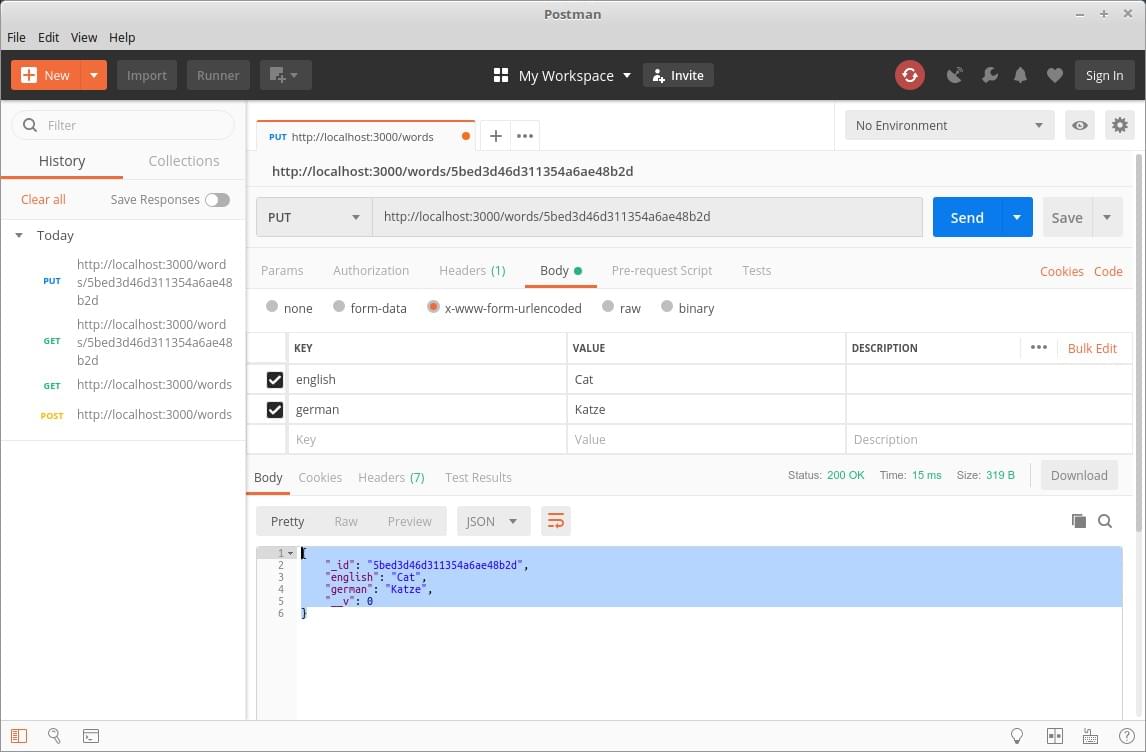

Update

Finally, let’s update a word, then delete it. To update the word, select PUT as the method and enter http://localhost:3000/words/<word _id> as the URL (where the ID of the word corresponds to _id as described above). Select the Body tab and the radio button x-www-form-urlencoded, then enter two key/value pairs into the fields below different than before. Press Send and you should receive the newly updated object from the server by way of a response:

{

"_id": "5bed3d46d311354a6ae48b2d",

"english": "Cat",

"german": "Katze",

"__v": 0

}

Destroy

To delete a word, just change the method to DELETE and press Send. Zap! The word should be gone and your collection should be empty. You can test that this is indeed the case, either using Compass, or by selecting the original request to get all words from the left hand pane in Postman and firing that off again. This time it should return an empty array.

And that’s it. We’re done with our back end. Don’t forget that you can find all of the code for this guide on GitHub, so if something didn’t work as expected, try cloning the repo and running that.

Creating the Vue Front End

Previously we created our back end in a server folder. We’ll create the front-end part of the app in a front-end folder. This separation of concerns means that it would be easier to swap out the front end if we ever decided we wanted to use a framework other than Vue.

Let’s get to it.

Basic Setup

We’ll use Vue CLI to scaffold the project:

npm install -g @vue/cli

Make sure you’re in the root folder of the project (vocab-builder), then run the following:

vue create front-end

This will open a wizard to walk you through creating a new Vue app. Answer the questions as follows:

? Please pick a preset: Manually select features

? Check the features needed for your project: Babel, Router, Linter

? Use history mode for router? Yes

? Pick a linter / formatter config: ESLint with error prevention only

? Pick additional lint features: Lint on save

? Where do you prefer placing config for Babel etc.? In dedicated config files

? Save this as a preset for future projects? No

The main thing to note here is that we’re installing the Vue router, which we’ll use to display the different views in our front end.

Next, change into our new directory:

cd front-end

There are a few files created by the CLI that we don’t need. We can delete these now:

rm src/assets/logo.png src/components/HelloWorld.vue src/views/About.vue src/views/Home.vue

There are also a bunch of files we’ll need to create:

cd src

touch components/{VocabTest.vue,WordForm.vue}

touch views/{Edit.vue,New.vue,Show.vue,Test.vue,Words.vue}

mkdir helpers

touch helpers/helpers.js

When you’re finished, the contents of your vocab-builder/front-end/src folder should look like this:

.

├── App.vue

├── assets

├── components

│ ├── VocabTest.vue

│ └── WordForm.vue

├── helpers

│ └── helpers.js

├── main.js

├── router.js

└── views

├── Edit.vue

├── New.vue

├── Show.vue

├── Test.vue

└── Words.vue

Install the Dependencies

For the front end, we’ll be using the following libraries:

- axios—a Promise-based HTTP client which will allow us to make Ajax requests from our front end to our back end.

- semantic-ui-css—a lightweight, CSS-only version of Semantic UI.

- vue-flash-message—a Vue flash message component which we will use to display information to the user.

Let’s get them installed:

npm i axios semantic-ui-css vue-flash-message

And with that, we’re ready to start coding.

Creating the Routes

Firstly, we need to consider which routes our application will have. We’ll need to perform all of the CRUD options we discussed previously, and it would also be nice if the user could test themselves against whatever words have been added to the database.

To this end, we’ll create the following:

/words—display all the words in the database/words/new—create a new word/words/:id—display a word/words/:id/edit—edit a word/test—test your knowledge

Deleting a word doesn’t require its own route. We’ll just fire off the appropriate request and redirect to /words.

To put this into action, open up src/router.js and replace the existing code with the following:

import Vue from 'vue';

import Router from 'vue-router';

import Words from './views/Words.vue';

import New from './views/New.vue';

import Show from './views/Show.vue';

import Edit from './views/Edit.vue';

import Test from './views/Test.vue';

Vue.use(Router);

export default new Router({

mode: 'history',

base: process.env.BASE_URL,

linkActiveClass: 'active',

routes: [

{

path: '/',

redirect: '/words'

},

{

path: '/words',

name: 'words',

component: Words

},

{

path: '/words/new',

name: 'new-word',

component: New

},

{

path: '/words/:id',

name: 'show',

component: Show

},

{

path: '/words/:id/edit',

name: 'edit',

component: Edit

},

{

path: '/test',

name: 'test',

component: Test

}

]

});

This creates the routes we discussed above. It also redirects the root URL / to /words and tells the router to apply a class of active to the currently activated navigation link (the default would be router-link-active, which wouldn’t play nicely with semantic-ui-css).

Talking of which, next we need to open up src/main.js and tell Vue to use semantic-ui-css:

import Vue from 'vue';

import App from './App.vue';

import router from './router';

import 'semantic-ui-css/semantic.css';

Vue.config.productionTip = false;

new Vue({

router,

render: h => h(App)

}).$mount('#app');

And finally, we need to replace the code in src/App.vue with the following:

<template>

<div id="app">

<div class="ui inverted segment navbar">

<div class="ui center aligned container">

<div class="ui large secondary inverted pointing menu compact">

<router-link to="/words" exact class="item">

<i class="comment outline icon"></i> Words

</router-link>

<router-link to="/words/new" class="item">

<i class="plus circle icon"></i> New

</router-link>

<router-link to="/test" class="item">

<i class="graduation cap icon"></i> Test

</router-link>

</div>

</div>

</div>

<div class="ui text container">

<div class="ui one column grid">

<div class="column">

<router-view />

</div>

</div>

</div>

</div>

</template>

<script>

export default {

name: 'app'

};

</script>

<style>

#app > div.navbar {

margin-bottom: 1.5em;

}

.myFlash {

width: 250px;

margin: 10px;

position: absolute;

top: 50;

right: 0;

}

input {

width: 300px;

}

div.label {

width: 120px;

}

div.input {

margin-bottom: 10px;

}

button.ui.button {

margin-top: 15px;

display: block;

}

</style>

This creates a nav bar at the top of the screen, then declares an outlet (the <router-view /> component) for our views.

Start the application from within the front-end folder with the command npm run serve.

You should now be able to go to http://localhost:8080 and navigate around the shell of our app.

Exciting times, huh?

Communicating with the Back End

The next thing we need to do is establish a method of communicating with our Node back end. This is where the axios library comes in that we installed previously. To make our app flexible, we can add any axios-related code to a helper file which can be included in any component that needs it. Setting things up this way has the advantage of keeping all of our Ajax logic in one place, and also means that if we ever wanted to swap out axios for a different library, it would be pretty easy.

So open up src/helpers/helpers.js and add the following code:

import axios from 'axios';

const baseURL = 'http://localhost:3000/words/';

const handleError = fn => (...params) =>

fn(...params).catch(error => {

console.log(error);

});

export const api = {

getWord: handleError(async id => {

const res = await axios.get(baseURL + id);

return res.data;

}),

getWords: handleError(async () => {

const res = await axios.get(baseURL);

return res.data;

}),

deleteWord: handleError(async id => {

const res = await axios.delete(baseURL + id);

return res.data;

}),

createWord: handleError(async payload => {

const res = await axios.post(baseURL, payload);

return res.data;

}),

updateWord: handleError(async payload => {

const res = await axios.put(baseURL + payload._id, payload);

return res.data;

})

};

There are a couple of things to be aware of here. Firstly, we’re exporting an api object that exposes methods corresponding to the endpoints we created in the previous section. These methods will make Ajax calls to our back end, which will carry out the various CRUD operations.

Secondly, due to the asynchronous nature of Ajax, we’re using async/await, which allows us to wait for the result of an asynchronous operation (such as writing to the database) before continuing with the rest of the code. However, there’s a slight caveat here. The normal way of dealing with errors within async/await is to wrap everything in a try/catch block:

export const api = {

getWord: async id => {

try {

await axios.get(baseURL + id);

return res.data;

} catch(error) {

console.log(error);

}

}

...

}

However, this is very verbose and would make for some bloated code, as we would need to do it for each Ajax call. An alternative approach is to use a higher-order function to handle the error for us.

This higher-order function takes a function as an argument (function a) and returns a function (function b), which, when called, will call function a, passing along any arguments it received. Function b will also chain a catch block to the end of function a, meaning that if an error occurs in function a, it will be caught and dealt with.

const handleError = fn => (...params) =>

fn(...params).catch(error => {

console.log(error);

});

export const api = {

getWord: handleError(async id => {

const res = await axios.get(baseURL + id);

return res.data;

})

...

}

If you’d like to dive into this some more, check out our article Flow Control in Modern JS: Callbacks to Promises to Async/Await.

Fetching Words from the Database

So let’s get some words to display to the user. Open up the src/views/Words.vue component and add the following code:

<template>

<div>

<h1>Words</h1>

<table id="words" class="ui celled compact table">

<thead>

<tr>

<th>English</th>

<th>German</th>

<th colspan="3"></th>

</tr>

</thead>

<tr v-for="(word, i) in words" :key="i">

<td>{{ word.english }}</td>

<td>{{ word.german }}</td>

<td width="75" class="center aligned">Show</td>

<td width="75" class="center aligned">Edit</td>

<td width="75" class="center aligned">Destroy</td>

</tr>

</table>

</div>

</template>

<script>

import { api } from '../helpers/helpers';

export default {

name: 'words',

data() {

return {

words: []

};

},

async mounted() {

this.words = await api.getWords();

}

};

</script>

As you can see, we’re importing our API to perform operations against the back end, then in the component’s mounted lifecycle hook we’re calling its getWords method to fetch all of the words from the database. As the component has a words property on its data object, we can await the answer from the back end, then insert the response into this.words and the component will update.

Give it a try. Use Compass or Postman to insert a word into the database, then observe that it’s displayed on the page at /words.

Displaying a Single Word

Let’s now add the functionality to display a single word from the list of words. In src/views/Words.vue, replace:

<td width="75" class="center aligned">Show</td>

with:

<td width="75" class="center aligned">

<router-link :to="{ name: 'show', params: { id: word._id }}">Show</router-link>

</td>

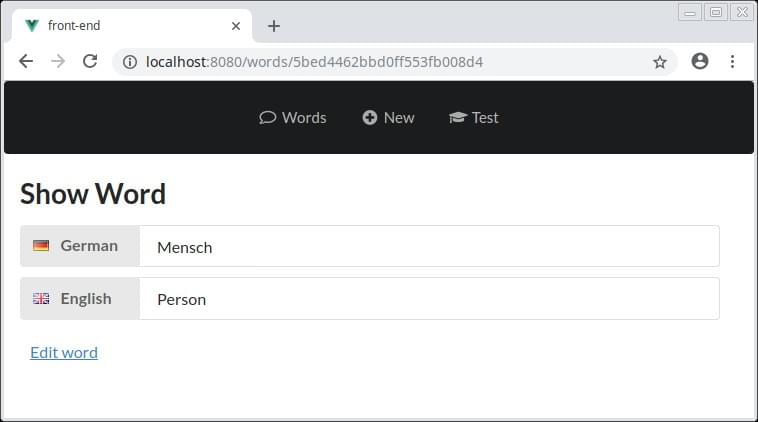

This creates a link to the show route which we defined in our src/router.js file. It uses the current word’s _id property to build the URL, resulting in something like http://localhost:8081/words/5bed4462bbd0ff553fb008d4.

Now open up src/views/Show.vue and add the following code:

<template>

<div>

<h1>Show Word</h1>

<div class="ui labeled input fluid">

<div class="ui label">

<i class="germany flag"></i> German

</div>

<input type="text" readonly :value="word.german"/>

</div>

<div class="ui labeled input fluid">

<div class="ui label">

<i class="united kingdom flag"></i> English

</div>

<input type="text" readonly :value="word.english"/>

</div>

<div class="actions">

<router-link :to="{ name: 'edit', params: { id: this.$route.params.id }}">

Edit word

</router-link>

</div>

</div>

</template>

<script>

import { api } from '../helpers/helpers';

export default {

name: 'show',

data() {

return {

word: ''

};

},

async mounted() {

this.word = await api.getWord(this.$route.params.id);

}

};

</script>

<style scoped>

.actions a {

display: block;

text-decoration: underline;

margin: 20px 10px;

}

</style>

When mounted, this component will use the same technique as before to get a single word from the database. It identifies the word in question by extracting its ID from the URL using this.$route.params.id. This is possible because of how we declared the route in src/router.js. Here we used path: "/words/:id" which means that anything after /words/ should be available to us as $route.params.id.

Also take note of the scoped attribute on the <style> tag. This means that any styles declared here are applied to this component only.

If you run the app at this point, you should be able to see a list of words contained in the database under /words and view individual words by clicking on Show.

You’ll notice there’s an Edit word link in the screenshot above. Let’s implement that now.

Editing a Word

Open src/views/Edit.vue and add the following:

<template>

<div>

<h1>Edit Word</h1>

<word-form :word=this.word></word-form>

</div>

</template>

<script>

import WordForm from '../components/WordForm.vue';

import { api } from '../helpers/helpers';

export default {

name: 'edit',

components: {

'word-form': WordForm

},

data: function() {

return {

word: {}

};

},

async mounted() {

this.word = await api.getWord(this.$route.params.id);

}

};

</script>

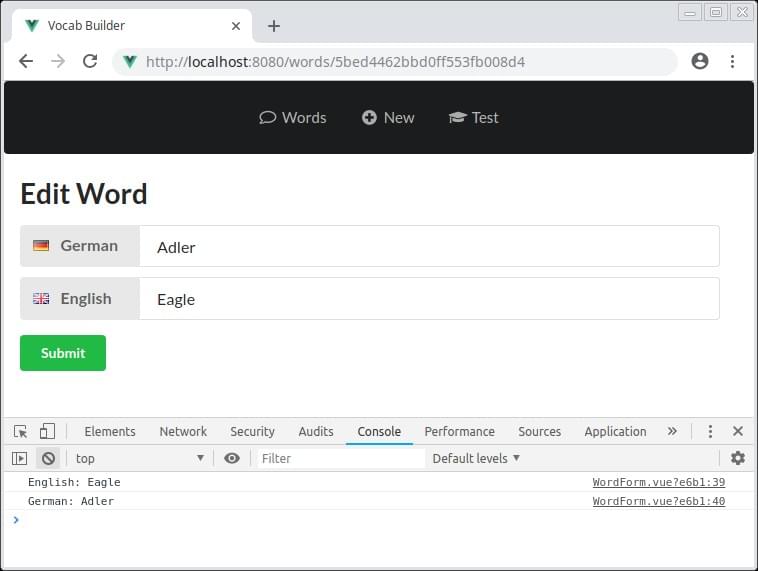

There’s something slightly different going on in this component. If you look within the <template> tag, you’ll notice that we’re including another component, WordForm, and passing it the value of this.word as a prop. The value of this.word is being retrieved within the mounted lifecycle hook, just as we’ve done in the other components. Also notice that we’re declaring the child component that the Edit component requires, like so:

components: {

"word-form": WordForm

}

So why are we including a WordForm component and handing the word to be edited off to that? Well, the reason is reusability. By structuring things this way, we’ll be able to use the same WordForm component in a little while when we come to implement the functionality to create a new word.

Let’s have a look at the WordForm component. Open up src/components/WordForm.vue and add the following code:

<template>

<form action="#" @submit.prevent="onSubmit">

<p v-if="errorsPresent" class="error">Please fill out both fields!</p>

<div class="ui labeled input fluid">

<div class="ui label">

<i class="germany flag"></i> German

</div>

<input type="text" placeholder="Enter word..." v-model="word.german" />

</div>

<div class="ui labeled input fluid">

<div class="ui label">

<i class="united kingdom flag"></i> English

</div>

<input type="text" placeholder="Enter word..." v-model="word.english" />

</div>

<button class="positive ui button">Submit</button>

</form>

</template>

<script>

export default {

name: 'word-form',

props: {

word: {

type: Object,

required: false

}

},

data() {

return {

errorsPresent: false

};

},

methods: {

onSubmit: function() {

console.log(`English: ${this.word.english}`);

console.log(`German: ${this.word.german}`);

}

}

};

</script>

<style scoped>

.error {

color: red;

}

</style>

There’s quite a bit going on here. Firstly, we have a form tag and we’ve bound the submit event to the onSubmit method we’ve defined in our methods object. We’re also using the prevent modifier to prevent the browser’s default action—in this case, submitting the form.

Next comes a paragraph tag to display an error message if either of the input fields is empty. We use v-if to only display this if the errorsPresent property evaluates to something truthy.

Then we have our form with two input fields, one for the English word and one for its German equivalent. We’re using v-model to set up two-way data binding between the english and german properties of the prop we’re passed and the input fields.

In the <script> section, we then declare that the word prop is of type Object, and that it isn’t required (because we’ll also use this form to create a new word). The data object declares the aforementioned errorsPresent property and our method object, the onSubmit method. All we’re doing in this method is logging out the value of whatever has been entered into the inputs.

At this point, if you visit the Edit word view, you should see the correct word displayed in the fields. And when you click Submit, you should see the value of both input fields logged to the console.

Finally, we need to expand our onSubmit method to do something other than log the values of the inputs to the console. Alter it like so:

onSubmit: function() {

if (this.word.english === '' || this.word.german === '') {

this.errorsPresent = true;

} else {

this.$emit('createOrUpdate', this.word);

}

}

This checks that both fields have a value. If not, it flags the error, otherwise it emits an event createOrUpdate which we can listen for in the parent component (in this case, Edit). I’ve called it createOrUpdate, as the corresponding functionality in the parent component will be doing one of these two things.

Back in src/views/Edit.vue, we need to listen for and respond to the createOrUpdate event. Change:

<word-form :word=this.word></word-form>

to:

<word-form @createOrUpdate="createOrUpdate" :word=this.word></word-form>

And implement the update functionality in the methods object:

methods: {

createOrUpdate: async function(word) {

await api.updateWord(word);

alert('Word updated sucessfully!');

this.$router.push(`/words/${word._id}`);

}

}

Now when you try to update a word, it will check that neither field is blank, and if not, update the word, before alerting a success message and redirecting you to the newly updated word.

As a final touch to this section, hop back into src/views/Words.vue and change:

<td width="75" class="center aligned">Edit</td>

to:

<td width="75" class="center aligned">

<router-link :to="{ name: 'edit', params: { id: word._id }}">Edit</router-link>

</td>

Adding Flash Messages

Okay, so our app is looking pretty good, but using alerts to inform the user that something happened is a jarring experience. Let’s use flash messages instead. These are nicely styled, configurable messages which won’t block the execution of JavaScript in the browser.

The first thing we’ll need to do is to tell our app to use them. To this end, hop back into src/helpers/helpers.js and make sure the top of the file reads like so:

import axios from 'axios';

import Vue from 'vue';

import VueFlashMessage from 'vue-flash-message';

import 'vue-flash-message/dist/vue-flash-message.min.css';

Vue.use(VueFlashMessage, {

messageOptions: {

timeout: 3000,

pauseOnInteract: true

}

});

const vm = new Vue();

const baseURL = 'http://localhost:3000/words/';

const handleError = fn => (...params) =>

fn(...params).catch(error => {

vm.flash(`${error.response.status}: ${error.response.statusText}`, 'error');

});

export const api = { ... };

There are a few things going on here. We start by importing Vue and VueFlashMessages. We then tell Vue to use the VueFlashMessages plugin and pass it a couple of options. Finally, we create a new instance of Vue, as we also want to use the flash messages from within the helper file. You can see this happening within our handleError function in the call to vm.flash().

So that we can actually display the messages, let’s add a FlashMessage component to src/App.vue:

<div class="ui text container">

<flash-message class="myFlash"></flash-message>

<div class="ui one column grid">

<div class="column">

<router-view />

</div>

</div>

</div>

To test out whether it’s working, try changing the value of the baseURL variable in src/helpers/helpers.js to something non-existent. If all has gone according to plan, you should see a nicely formatted error message on the right hand of the screen when you visit any of our routes.

Finally, to make a flash message appear when a word was successfully edited, go back to src/views/Edit.vue and change:

alert("Word updated sucessfully!");

to:

this.flash('Word updated sucessfully!', 'success');

Creating a New Word

We’ve almost implemented all of our CRUD functionality. Next up is giving users the opportunity to add words of their own to our database. Open up src/views/New.vue and add the following:

<template>

<div>

<h1>New Word</h1>

<word-form @createOrUpdate="createOrUpdate"></word-form>

</div>

</template>

<script>

import WordForm from '../components/WordForm.vue';

import { api } from '../helpers/helpers';

export default {

name: 'new-word',

components: {

'word-form': WordForm

},

methods: {

createOrUpdate: async function(word) {

const res = await api.createWord(word);

this.flash('Word created', 'success');

this.$router.push(`/words/${res._id}`);

}

}

};

</script>

This should hopefully look familiar to you, as it’s quite similar to the Edit component. It also uses the WordForm child component, but doesn’t pass it a prop. And, like the Edit component, it also listens for the createOrUpdate event. When it receives this event, it creates a new word with the given input and redirects to the newly created word.

Before we can use it, however, there are a couple of changes that need to be made to the WordForm component. Head back to src/components/WordForm.vue and expand the props object like so:

props: {

word: {

type: Object,

required: false,

default: () => {

return {

english: '',

german: ''

};

}

}

},

Here, we’re initializing both values as empty strings.

Now when you head to http://localhost:8080/words/new you should be able to create new words.

Destroying a Word

We won’t need a separate component to destroy a word, as there’s no view involved. The action takes place in src/views/Words.vue:

First change:

<td width="75" class="center aligned">Destroy</td>

to:

<td width="75" class="center aligned" @click.prevent="onDestroy(word._id)">

<a :href="`/words/${word._id}`">Destroy</a>

</td>

This will intercept the click on the table cell, prevent the browser’s default action, then call the onDestroy method. Let’s implement that now:

methods: {

async onDestroy(id) {

const sure = window.confirm('Are you sure?');

if (!sure) return;

await api.deleteWord(id);

this.flash('Word deleted sucessfully!', 'success');

const newWords = this.words.filter(word => word._id !== id);

this.words = newWords;

}

},

To make sure the user really intended to delete a word, we use a dialogue to ask them to confirm the delete. If the user clicks OK, a request is sent to the API to delete the word. We then flash a message to let them know that the delete was successful before removing the word from the list of words in the data object. This will ensure that the UI updates.

And with that, our CRUD app is fully functional. Yay!

Taking it Further

By way of a final touch, let’s add the possibility for users to test themselves on the words stored in the database.

Open up src/views/Test.vue and add the following code:

<template>

<div>

<h1>Test</h1>

<div v-if="words.length < 5">

<p>You need to enter at least five words to begin the test</p>

</div>

<div v-else>

<vocab-test :words="words"></vocab-test>

</div>

</div>

</template>

<script>

import { api } from '../helpers/helpers';

import VocabTest from '../components/VocabTest.vue';

export default {

name: 'test',

components: {

'vocab-test': VocabTest

},

data() {

return {

words: []

};

},

async mounted() {

this.words = await api.getWords();

}

};

</script>

Here, we’re waiting until the component has been mounted, then fetching all of our words from the database. If there are less than five, we display a message that there aren’t enough words to begin the test. Otherwise, we load the VocabTest component and pass it our list of words as a prop.

Now all that remains is to code the test itself. Open up src/components/VocabTest.vue and add the following:

<template>

<div>

<h2>Score: {{ score }} out of {{ this.words.length }}</h2>

<form action="#" @submit.prevent="onSubmit">

<div class="ui labeled input fluid">

<div class="ui label">

<i class="germany flag"></i> German

</div>

<input type="text" readonly :disabled="testOver" :value="currWord.german"/>

</div>

<div class="ui labeled input fluid">

<div class="ui label">

<i class="united kingdom flag"></i> English

</div>

<input type="text" placeholder="Enter word..." v-model="english" :disabled="testOver" autocomplete="off" />

</div>

<button class="positive ui button" :disabled="testOver">Submit</button>

</form>

<p :class="['results', resultClass]">

<span v-html="result"></span>

</p>

</div>

</template>

<script>

export default {

name: 'vocab-test',

props: {

words: {

type: Array,

required: true

}

},

data() {

return {

randWords: [...this.words.sort(() => 0.5 - Math.random())],

incorrectGuesses: [],

result: '',

resultClass: '',

english: '',

score: 0,

testOver: false

};

},

computed: {

currWord: function() {

return this.randWords.length ? this.randWords[0] : '';

}

},

methods: {

onSubmit: function() {

if (this.english === this.currWord.english) {

this.flash('Correct!', 'success', { timeout: 1000 });

this.score += 1;

} else {

this.flash('Wrong!', 'error', { timeout: 1000 });

this.incorrectGuesses.push(this.currWord.german);

}

this.english = '';

this.randWords.shift();

if (this.randWords.length === 0) {

this.testOver = true;

this.displayResults();

}

},

displayResults: function() {

if (this.incorrectGuesses.length === 0) {

this.result = 'You got everything correct. Well done!';

this.resultClass = 'success';

} else {

const incorrect = this.incorrectGuesses.join(', ');

this.result = `<strong>You got the following words wrong:</strong> ${incorrect}`;

this.resultClass = 'error';

}

}

}

};

</script>

<style scoped>

.results {

margin: 25px auto;

padding: 15px;

border-radius: 5px;

}

.error {

border: 1px solid #ebccd1;

color: #a94442;

background-color: #f2dede;

}

.success {

border: 1px solid #d6e9c6;

color: #3c763d;

background-color: #dff0d8;

}

</style>

This guide is already very long, so I won’t explain what every line of the code does. In a nutshell, however, we’re receiving the word list, words, as a prop (this is an array of objects). We then declare some data properties, mostly related to displaying the test. The randWords property makes use of the spread operator and an arrow function to sort the words into a random order.

We’re declaring currWord as a computed property, which will return the next word in the list of random words. I’ve used a computed property, as in the onSubmit method I’m removing the first item of the randWords array using shift() every time the user makes a guess. Mutating the array like this will cause currWord to be recalculated and the test will update.

Finally, the onSubmit method and the displayResults method handle form submission (when the user makes a guess) and, as you might have guessed, displaying the results.

Conclusion

This has been a long tutorial, so congratulations if you made it this far. I hope you now have a better understanding of how to set up a Vue.js front end to consume a Node API which can then persist data to a database.

And please don’t forget, the complete code is available on GitHub.