Chapter 9. Consistency and Consensus

Is it better to be alive and wrong or right and dead?

Jay Kreps, A Few Notes on Kafka and Jepsen (2013)

Lots of things can go wrong in distributed systems, as discussed in Chapter 8. The simplest way of handling such faults is to simply let the entire service fail, and show the user an error message. If that solution is unacceptable, we need to find ways of tolerating faults—that is, of keeping the service functioning correctly, even if some internal component is faulty.

In this chapter, we will talk about some examples of algorithms and protocols for building fault-tolerant distributed systems. We will assume that all the problems from Chapter 8 can occur: packets can be lost, reordered, duplicated, or arbitrarily delayed in the network; clocks are approximate at best; and nodes can pause (e.g., due to garbage collection) or crash at any time.

The best way of building fault-tolerant systems is to find some general-purpose abstractions with useful guarantees, implement them once, and then let applications rely on those guarantees. This is the same approach as we used with transactions in Chapter 7: by using a transaction, the application can pretend that there are no crashes (atomicity), that nobody else is concurrently accessing the database (isolation), and that storage devices are perfectly reliable (durability). Even though crashes, race conditions, and disk failures do occur, the transaction abstraction hides those problems so that the application doesn’t need to worry about them.

We will now continue along the same lines, and seek abstractions that can allow an application to ignore some of the problems with distributed systems. For example, one of the most important abstractions for distributed systems is consensus: that is, getting all of the nodes to agree on something. As we shall see in this chapter, reliably reaching consensus in spite of network faults and process failures is a surprisingly tricky problem.

Once you have an implementation of consensus, applications can use it for various purposes. For example, say you have a database with single-leader replication. If the leader dies and you need to fail over to another node, the remaining database nodes can use consensus to elect a new leader. As discussed in “Handling Node Outages”, it’s important that there is only one leader, and that all nodes agree who the leader is. If two nodes both believe that they are the leader, that situation is called split brain, and it often leads to data loss. Correct implementations of consensus help avoid such problems.

Later in this chapter, in “Distributed Transactions and Consensus”, we will look into algorithms to solve consensus and related problems. But we first need to explore the range of guarantees and abstractions that can be provided in a distributed system.

We need to understand the scope of what can and cannot be done: in some situations, it’s possible for the system to tolerate faults and continue working; in other situations, that is not possible. The limits of what is and isn’t possible have been explored in depth, both in theoretical proofs and in practical implementations. We will get an overview of those fundamental limits in this chapter.

Researchers in the field of distributed systems have been studying these topics for decades, so there is a lot of material—we’ll only be able to scratch the surface. In this book we don’t have space to go into details of the formal models and proofs, so we will stick with informal intuitions. The literature references offer plenty of additional depth if you’re interested.

Consistency Guarantees

In “Problems with Replication Lag” we looked at some timing issues that occur in a replicated database. If you look at two database nodes at the same moment in time, you’re likely to see different data on the two nodes, because write requests arrive on different nodes at different times. These inconsistencies occur no matter what replication method the database uses (single-leader, multi-leader, or leaderless replication).

Most replicated databases provide at least eventual consistency, which means that if you stop writing to the database and wait for some unspecified length of time, then eventually all read requests will return the same value [1]. In other words, the inconsistency is temporary, and it eventually resolves itself (assuming that any faults in the network are also eventually repaired). A better name for eventual consistency may be convergence, as we expect all replicas to eventually converge to the same value [2].

However, this is a very weak guarantee—it doesn’t say anything about when the replicas will converge. Until the time of convergence, reads could return anything or nothing [1]. For example, if you write a value and then immediately read it again, there is no guarantee that you will see the value you just wrote, because the read may be routed to a different replica (see “Reading Your Own Writes”).

Eventual consistency is hard for application developers because it is so different from the behavior of variables in a normal single-threaded program. If you assign a value to a variable and then read it shortly afterward, you don’t expect to read back the old value, or for the read to fail. A database looks superficially like a variable that you can read and write, but in fact it has much more complicated semantics [3].

When working with a database that provides only weak guarantees, you need to be constantly aware of its limitations and not accidentally assume too much. Bugs are often subtle and hard to find by testing, because the application may work well most of the time. The edge cases of eventual consistency only become apparent when there is a fault in the system (e.g., a network interruption) or at high concurrency.

In this chapter we will explore stronger consistency models that data systems may choose to provide. They don’t come for free: systems with stronger guarantees may have worse performance or be less fault-tolerant than systems with weaker guarantees. Nevertheless, stronger guarantees can be appealing because they are easier to use correctly. Once you have seen a few different consistency models, you’ll be in a better position to decide which one best fits your needs.

There is some similarity between distributed consistency models and the hierarchy of transaction isolation levels we discussed previously [4, 5] (see “Weak Isolation Levels”). But while there is some overlap, they are mostly independent concerns: transaction isolation is primarily about avoiding race conditions due to concurrently executing transactions, whereas distributed consistency is mostly about coordinating the state of replicas in the face of delays and faults.

This chapter covers a broad range of topics, but as we shall see, these areas are in fact deeply linked:

-

We will start by looking at one of the strongest consistency models in common use, linearizability, and examine its pros and cons.

-

We’ll then examine the issue of ordering events in a distributed system (“Ordering Guarantees”), particularly around causality and total ordering.

-

In the third section (“Distributed Transactions and Consensus”) we will explore how to atomically commit a distributed transaction, which will finally lead us toward solutions for the consensus problem.

Linearizability

In an eventually consistent database, if you ask two different replicas the same question at the same time, you may get two different answers. That’s confusing. Wouldn’t it be a lot simpler if the database could give the illusion that there is only one replica (i.e., only one copy of the data)? Then every client would have the same view of the data, and you wouldn’t have to worry about replication lag.

This is the idea behind linearizability [6] (also known as atomic consistency [7], strong consistency, immediate consistency, or external consistency [8]). The exact definition of linearizability is quite subtle, and we will explore it in the rest of this section. But the basic idea is to make a system appear as if there were only one copy of the data, and all operations on it are atomic. With this guarantee, even though there may be multiple replicas in reality, the application does not need to worry about them.

In a linearizable system, as soon as one client successfully completes a write, all clients reading from the database must be able to see the value just written. Maintaining the illusion of a single copy of the data means guaranteeing that the value read is the most recent, up-to-date value, and doesn’t come from a stale cache or replica. In other words, linearizability is a recency guarantee. To clarify this idea, let’s look at an example of a system that is not linearizable.

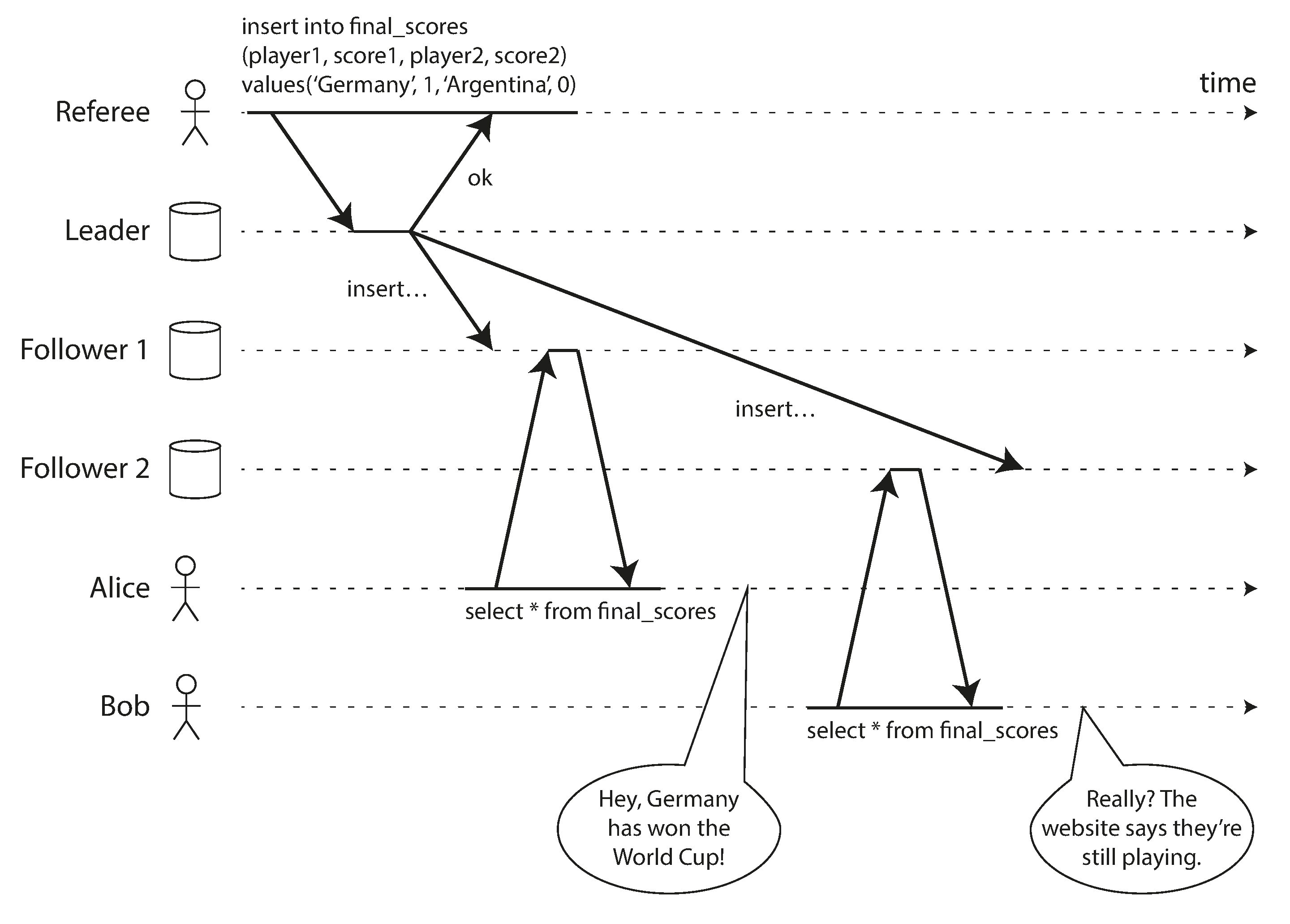

Figure 9-1. This system is not linearizable, causing football fans to be confused.

Figure 9-1 shows an example of a nonlinearizable sports website [9]. Alice and Bob are sitting in the same room, both checking their phones to see the outcome of the 2014 FIFA World Cup final. Just after the final score is announced, Alice refreshes the page, sees the winner announced, and excitedly tells Bob about it. Bob incredulously hits reload on his own phone, but his request goes to a database replica that is lagging, and so his phone shows that the game is still ongoing.

If Alice and Bob had hit reload at the same time, it would have been less surprising if they had gotten two different query results, because they wouldn’t know at exactly what time their respective requests were processed by the server. However, Bob knows that he hit the reload button (initiated his query) after he heard Alice exclaim the final score, and therefore he expects his query result to be at least as recent as Alice’s. The fact that his query returned a stale result is a violation of linearizability.

What Makes a System Linearizable?

The basic idea behind linearizability is simple: to make a system appear as if there is only a single copy of the data. However, nailing down precisely what that means actually requires some care. In order to understand linearizability better, let’s look at some more examples.

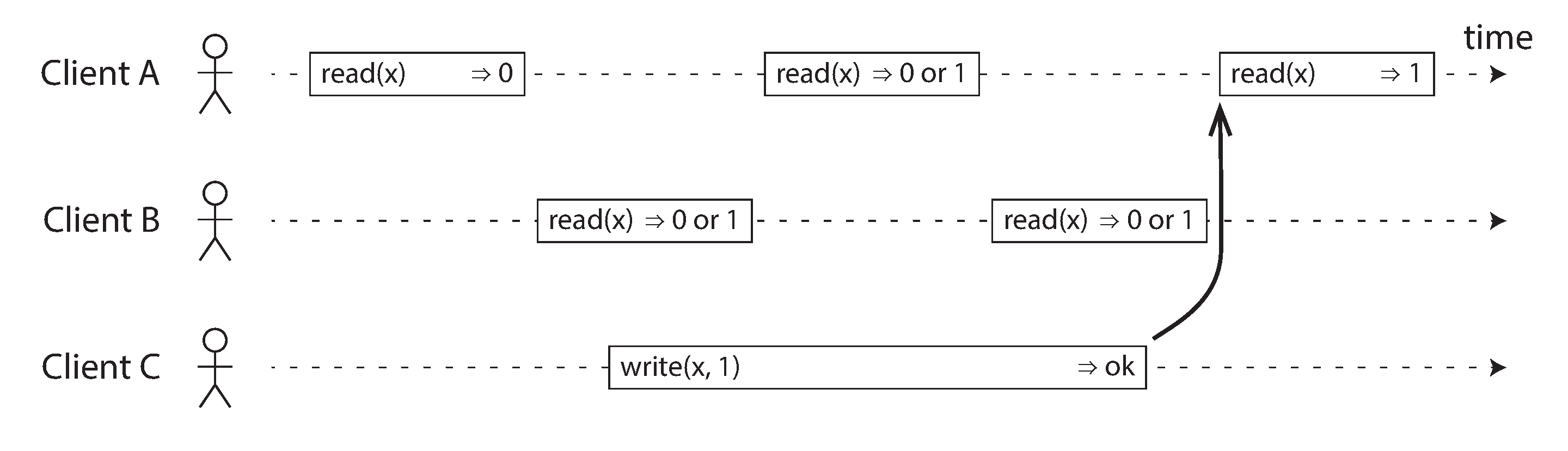

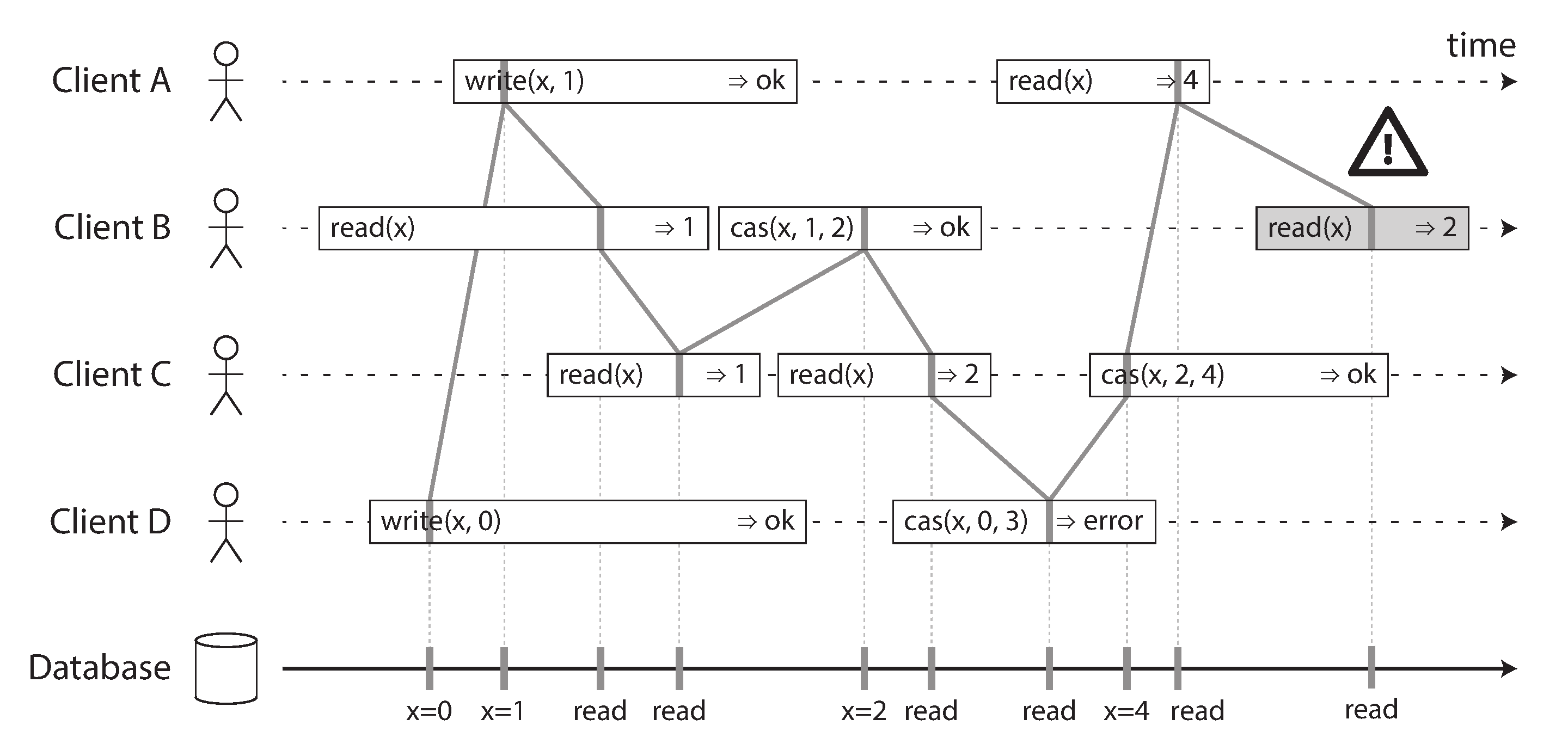

Figure 9-2 shows three clients concurrently reading and writing the same key x in a linearizable database. In the distributed systems literature, x is called a register—in practice, it could be one key in a key-value store, one row in a relational database, or one document in a document database, for example.

Figure 9-2. If a read request is concurrent with a write request, it may return either the old or the new value.

For simplicity, Figure 9-2 shows only the requests from the clients’ point of view, not the internals of the database. Each bar is a request made by a client, where the start of a bar is the time when the request was sent, and the end of a bar is when the response was received by the client. Due to variable network delays, a client doesn’t know exactly when the database processed its request—it only knows that it must have happened sometime between the client sending the request and receiving the response.i

In this example, the register has two types of operations:

-

read(x) ⇒ v means the client requested to read the value of register x, and the database returned the value v.

-

write(x, v) ⇒ r means the client requested to set the register x to value v, and the database returned response r (which could be ok or error).

In Figure 9-2, the value of x is initially 0, and client C performs a write request to set it to 1. While this is happening, clients A and B are repeatedly polling the database to read the latest value. What are the possible responses that A and B might get for their read requests?

-

The first read operation by client A completes before the write begins, so it must definitely return the old value 0.

-

The last read by client A begins after the write has completed, so it must definitely return the new value 1 if the database is linearizable: we know that the write must have been processed sometime between the start and end of the write operation, and the read must have been processed sometime between the start and end of the read operation. If the read started after the write ended, then the read must have been processed after the write, and therefore it must see the new value that was written.

-

Any read operations that overlap in time with the write operation might return either 0 or 1, because we don’t know whether or not the write has taken effect at the time when the read operation is processed. These operations are concurrent with the write.

However, that is not yet sufficient to fully describe linearizability: if reads that are concurrent with a write can return either the old or the new value, then readers could see a value flip back and forth between the old and the new value several times while a write is going on. That is not what we expect of a system that emulates a “single copy of the data.”ii

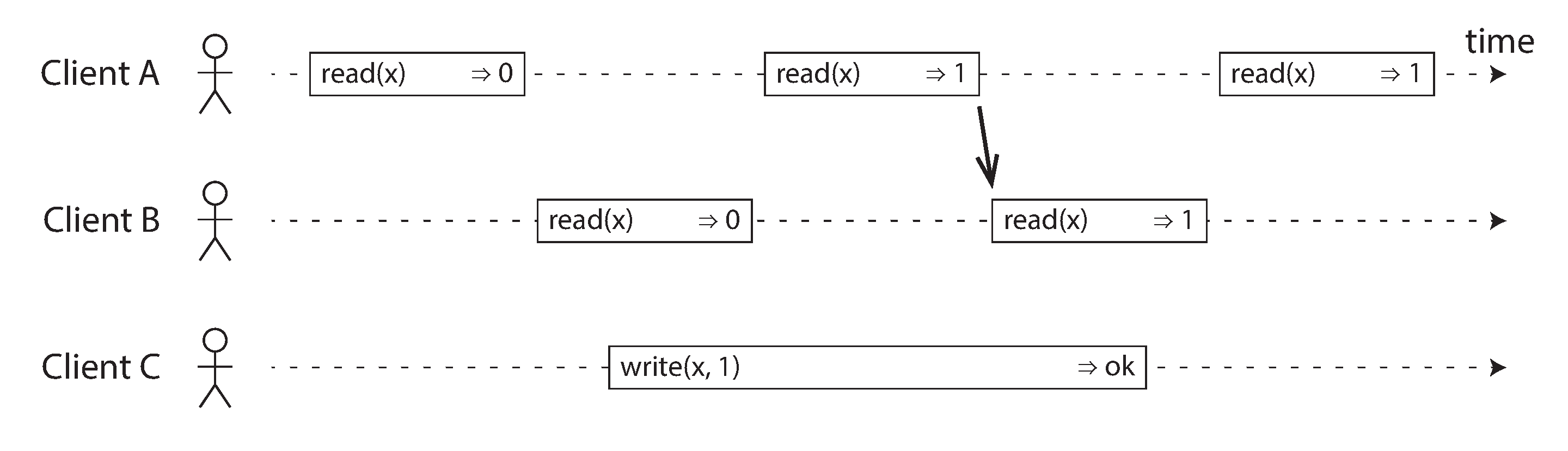

To make the system linearizable, we need to add another constraint, illustrated in Figure 9-3.

Figure 9-3. After any one read has returned the new value, all following reads (on the same or other clients) must also return the new value.

In a linearizable system we imagine that there must be some point in time (between the start and end of the write operation) at which the value of x atomically flips from 0 to 1. Thus, if one client’s read returns the new value 1, all subsequent reads must also return the new value, even if the write operation has not yet completed.

This timing dependency is illustrated with an arrow in Figure 9-3. Client A is the first to read the new value, 1. Just after A’s read returns, B begins a new read. Since B’s read occurs strictly after A’s read, it must also return 1, even though the write by C is still ongoing. (It’s the same situation as with Alice and Bob in Figure 9-1: after Alice has read the new value, Bob also expects to read the new value.)

We can further refine this timing diagram to visualize each operation taking effect atomically at some point in time. A more complex example is shown in Figure 9-4 [10].

In Figure 9-4 we add a third type of operation besides read and write:

-

cas(x, vold, vnew) ⇒ r means the client requested an atomic compare-and-set operation (see “Compare-and-set”). If the current value of the register x equals vold, it should be atomically set to vnew. If x ≠ vold then the operation should leave the register unchanged and return an error. r is the database’s response (ok or error).

Each operation in Figure 9-4 is marked with a vertical line (inside the bar for each operation) at the time when we think the operation was executed. Those markers are joined up in a sequential order, and the result must be a valid sequence of reads and writes for a register (every read must return the value set by the most recent write).

The requirement of linearizability is that the lines joining up the operation markers always move forward in time (from left to right), never backward. This requirement ensures the recency guarantee we discussed earlier: once a new value has been written or read, all subsequent reads see the value that was written, until it is overwritten again.

Figure 9-4. Visualizing the points in time at which the reads and writes appear to have taken effect. The final read by B is not linearizable.

There are a few interesting details to point out in Figure 9-4:

-

First client B sent a request to read x, then client D sent a request to set x to 0, and then client A sent a request to set x to 1. Nevertheless, the value returned to B’s read is 1 (the value written by A). This is okay: it means that the database first processed D’s write, then A’s write, and finally B’s read. Although this is not the order in which the requests were sent, it’s an acceptable order, because the three requests are concurrent. Perhaps B’s read request was slightly delayed in the network, so it only reached the database after the two writes.

-

Client B’s read returned 1 before client A received its response from the database, saying that the write of the value 1 was successful. This is also okay: it doesn’t mean the value was read before it was written, it just means the ok response from the database to client A was slightly delayed in the network.

-

This model doesn’t assume any transaction isolation: another client may change a value at any time. For example, C first reads 1 and then reads 2, because the value was changed by B between the two reads. An atomic compare-and-set (cas) operation can be used to check the value hasn’t been concurrently changed by another client: B and C’s cas requests succeed, but D’s cas request fails (by the time the database processes it, the value of x is no longer 0).

-

The final read by client B (in a shaded bar) is not linearizable. The operation is concurrent with C’s cas write, which updates x from 2 to 4. In the absence of other requests, it would be okay for B’s read to return 2. However, client A has already read the new value 4 before B’s read started, so B is not allowed to read an older value than A. Again, it’s the same situation as with Alice and Bob in Figure 9-1.

That is the intuition behind linearizability; the formal definition [6] describes it more precisely. It is possible (though computationally expensive) to test whether a system’s behavior is linearizable by recording the timings of all requests and responses, and checking whether they can be arranged into a valid sequential order [11].

Relying on Linearizability

In what circumstances is linearizability useful? Viewing the final score of a sporting match is perhaps a frivolous example: a result that is outdated by a few seconds is unlikely to cause any real harm in this situation. However, there a few areas in which linearizability is an important requirement for making a system work correctly.

Locking and leader election

A system that uses single-leader replication needs to ensure that there is indeed only one leader, not several (split brain). One way of electing a leader is to use a lock: every node that starts up tries to acquire the lock, and the one that succeeds becomes the leader [14]. No matter how this lock is implemented, it must be linearizable: all nodes must agree which node owns the lock; otherwise it is useless.

Coordination services like Apache ZooKeeper [15] and etcd [16] are often used to implement distributed locks and leader election. They use consensus algorithms to implement linearizable operations in a fault-tolerant way (we discuss such algorithms later in this chapter, in “Fault-Tolerant Consensus”).iii There are still many subtle details to implementing locks and leader election correctly (see for example the fencing issue in “The leader and the lock”), and libraries like Apache Curator [17] help by providing higher-level recipes on top of ZooKeeper. However, a linearizable storage service is the basic foundation for these coordination tasks.

Distributed locking is also used at a much more granular level in some distributed databases, such as Oracle Real Application Clusters (RAC) [18]. RAC uses a lock per disk page, with multiple nodes sharing access to the same disk storage system. Since these linearizable locks are on the critical path of transaction execution, RAC deployments usually have a dedicated cluster interconnect network for communication between database nodes.

Constraints and uniqueness guarantees

Uniqueness constraints are common in databases: for example, a username or email address must uniquely identify one user, and in a file storage service there cannot be two files with the same path and filename. If you want to enforce this constraint as the data is written (such that if two people try to concurrently create a user or a file with the same name, one of them will be returned an error), you need linearizability.

This situation is actually similar to a lock: when a user registers for your service, you can think of them acquiring a “lock” on their chosen username. The operation is also very similar to an atomic compare-and-set, setting the username to the ID of the user who claimed it, provided that the username is not already taken.

Similar issues arise if you want to ensure that a bank account balance never goes negative, or that you don’t sell more items than you have in stock in the warehouse, or that two people don’t concurrently book the same seat on a flight or in a theater. These constraints all require there to be a single up-to-date value (the account balance, the stock level, the seat occupancy) that all nodes agree on.

In real applications, it is sometimes acceptable to treat such constraints loosely (for example, if a flight is overbooked, you can move customers to a different flight and offer them compensation for the inconvenience). In such cases, linearizability may not be needed, and we will discuss such loosely interpreted constraints in “Timeliness and Integrity”.

However, a hard uniqueness constraint, such as the one you typically find in relational databases, requires linearizability. Other kinds of constraints, such as foreign key or attribute constraints, can be implemented without requiring linearizability [19].

Cross-channel timing dependencies

Notice a detail in Figure 9-1: if Alice hadn’t exclaimed the score, Bob wouldn’t have known that the result of his query was stale. He would have just refreshed the page again a few seconds later, and eventually seen the final score. The linearizability violation was only noticed because there was an additional communication channel in the system (Alice’s voice to Bob’s ears).

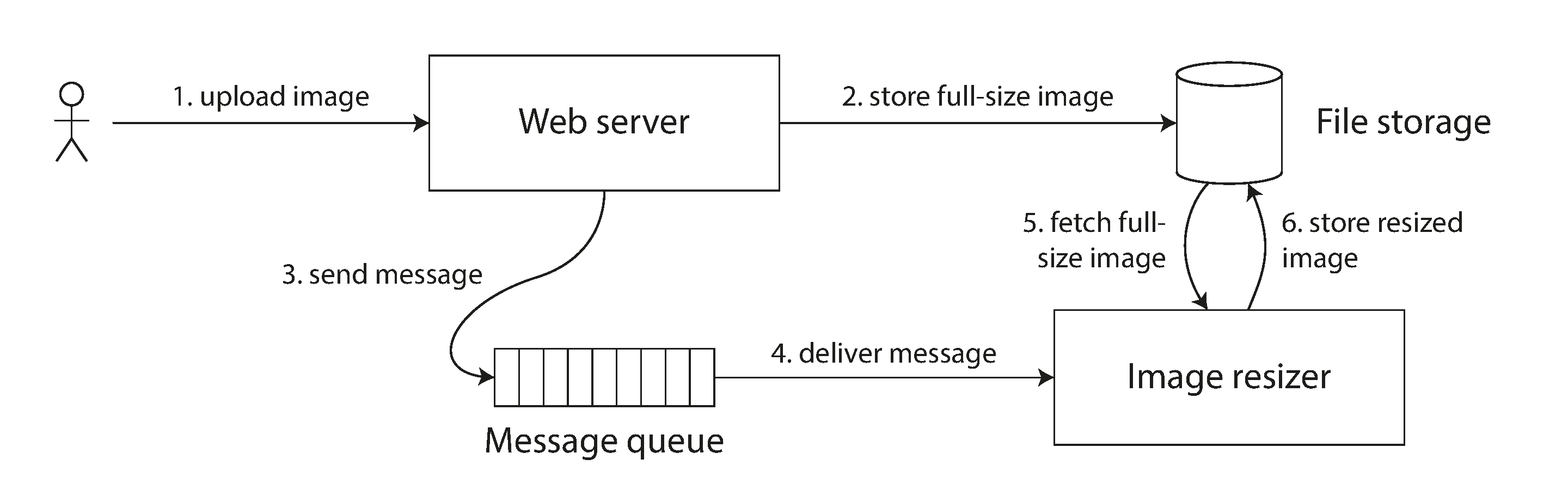

Similar situations can arise in computer systems. For example, say you have a website where users can upload a photo, and a background process resizes the photos to lower resolution for faster download (thumbnails). The architecture and dataflow of this system is illustrated in Figure 9-5.

The image resizer needs to be explicitly instructed to perform a resizing job, and this instruction is sent from the web server to the resizer via a message queue (see Chapter 11). The web server doesn’t place the entire photo on the queue, since most message brokers are designed for small messages, and a photo may be several megabytes in size. Instead, the photo is first written to a file storage service, and once the write is complete, the instruction to the resizer is placed on the queue.

Figure 9-5. The web server and image resizer communicate both through file storage and a message queue, opening the potential for race conditions.

If the file storage service is linearizable, then this system should work fine. If it is not linearizable, there is the risk of a race condition: the message queue (steps 3 and 4 in Figure 9-5) might be faster than the internal replication inside the storage service. In this case, when the resizer fetches the image (step 5), it might see an old version of the image, or nothing at all. If it processes an old version of the image, the full-size and resized images in the file storage become permanently inconsistent.

This problem arises because there are two different communication channels between the web server and the resizer: the file storage and the message queue. Without the recency guarantee of linearizability, race conditions between these two channels are possible. This situation is analogous to Figure 9-1, where there was also a race condition between two communication channels: the database replication and the real-life audio channel between Alice’s mouth and Bob’s ears.

Linearizability is not the only way of avoiding this race condition, but it’s the simplest to understand. If you control the additional communication channel (like in the case of the message queue, but not in the case of Alice and Bob), you can use alternative approaches similar to what we discussed in “Reading Your Own Writes”, at the cost of additional complexity.

Implementing Linearizable Systems

Now that we’ve looked at a few examples in which linearizability is useful, let’s think about how we might implement a system that offers linearizable semantics.

Since linearizability essentially means “behave as though there is only a single copy of the data, and all operations on it are atomic,” the simplest answer would be to really only use a single copy of the data. However, that approach would not be able to tolerate faults: if the node holding that one copy failed, the data would be lost, or at least inaccessible until the node was brought up again.

The most common approach to making a system fault-tolerant is to use replication. Let’s revisit the replication methods from Chapter 5, and compare whether they can be made linearizable:

- Single-leader replication (potentially linearizable)

-

In a system with single-leader replication (see “Leaders and Followers”), the leader has the primary copy of the data that is used for writes, and the followers maintain backup copies of the data on other nodes. If you make reads from the leader, or from synchronously updated followers, they have the potential to be linearizable.iv However, not every single-leader database is actually linearizable, either by design (e.g., because it uses snapshot isolation) or due to concurrency bugs [10].

Using the leader for reads relies on the assumption that you know for sure who the leader is. As discussed in “The Truth Is Defined by the Majority”, it is quite possible for a node to think that it is the leader, when in fact it is not—and if the delusional leader continues to serve requests, it is likely to violate linearizability [20]. With asynchronous replication, failover may even lose committed writes (see “Handling Node Outages”), which violates both durability and linearizability.

- Consensus algorithms (linearizable)

-

Some consensus algorithms, which we will discuss later in this chapter, bear a resemblance to single-leader replication. However, consensus protocols contain measures to prevent split brain and stale replicas. Thanks to these details, consensus algorithms can implement linearizable storage safely. This is how ZooKeeper [21] and etcd [22] work, for example.

- Multi-leader replication (not linearizable)

-

Systems with multi-leader replication are generally not linearizable, because they concurrently process writes on multiple nodes and asynchronously replicate them to other nodes. For this reason, they can produce conflicting writes that require resolution (see “Handling Write Conflicts”). Such conflicts are an artifact of the lack of a single copy of the data.

- Leaderless replication (probably not linearizable)

-

For systems with leaderless replication (Dynamo-style; see “Leaderless Replication”), people sometimes claim that you can obtain “strong consistency” by requiring quorum reads and writes (w + r > n). Depending on the exact configuration of the quorums, and depending on how you define strong consistency, this is not quite true.

“Last write wins” conflict resolution methods based on time-of-day clocks (e.g., in Cassandra; see “Relying on Synchronized Clocks”) are almost certainly nonlinearizable, because clock timestamps cannot be guaranteed to be consistent with actual event ordering due to clock skew. Sloppy quorums (“Sloppy Quorums and Hinted Handoff”) also ruin any chance of linearizability. Even with strict quorums, nonlinearizable behavior is possible, as demonstrated in the next section.

Linearizability and quorums

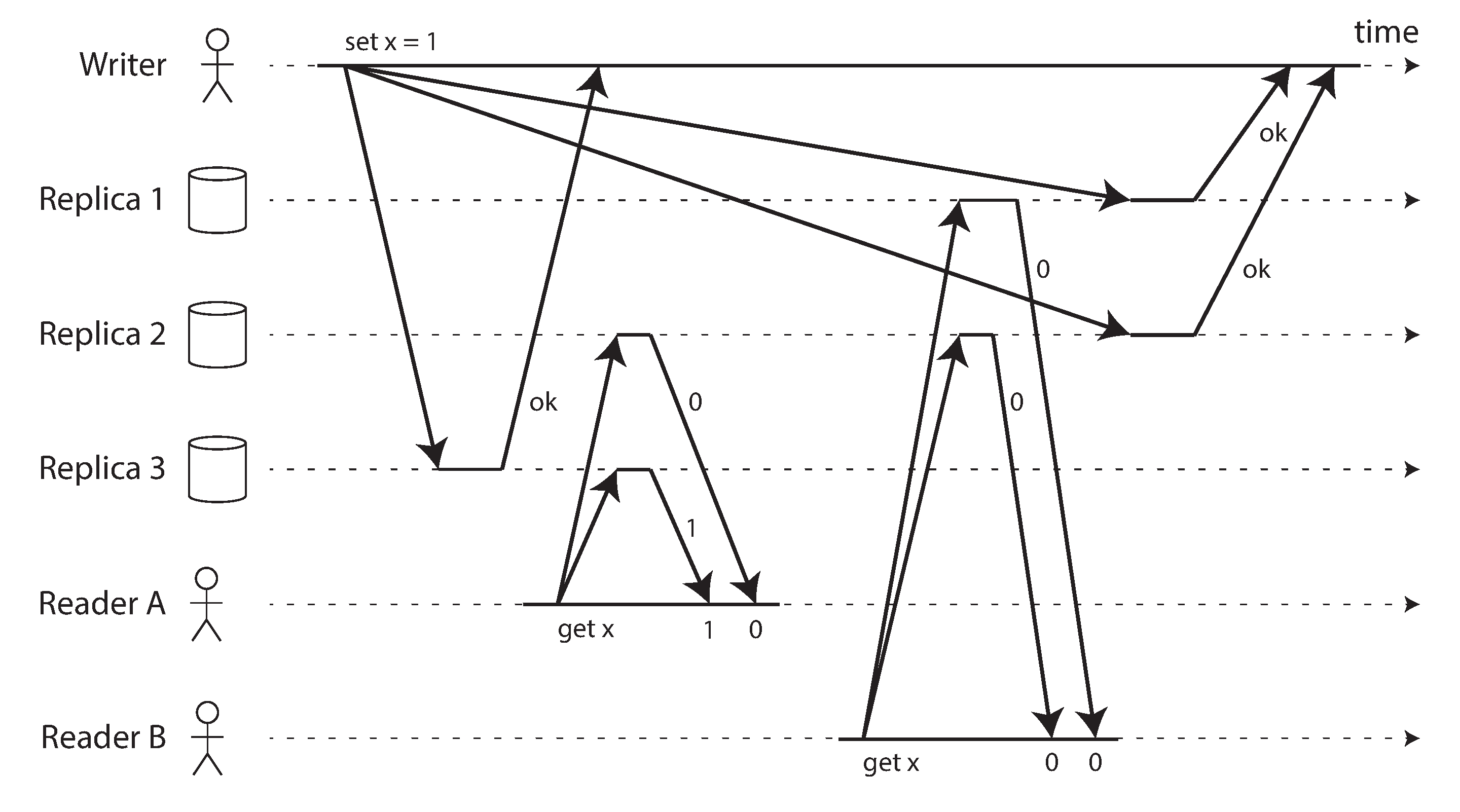

Intuitively, it seems as though strict quorum reads and writes should be linearizable in a Dynamo-style model. However, when we have variable network delays, it is possible to have race conditions, as demonstrated in Figure 9-6.

Figure 9-6. A nonlinearizable execution, despite using a strict quorum.

In Figure 9-6, the initial value of x is 0, and a writer client is updating x to 1 by sending the write to all three replicas (n = 3, w = 3). Concurrently, client A reads from a quorum of two nodes (r = 2) and sees the new value 1 on one of the nodes. Also concurrently with the write, client B reads from a different quorum of two nodes, and gets back the old value 0 from both.

The quorum condition is met (w + r > n), but this execution is nevertheless not linearizable: B’s request begins after A’s request completes, but B returns the old value while A returns the new value. (It’s once again the Alice and Bob situation from Figure 9-1.)

Interestingly, it is possible to make Dynamo-style quorums linearizable at the cost of reduced performance: a reader must perform read repair (see “Read repair and anti-entropy”) synchronously, before returning results to the application [23], and a writer must read the latest state of a quorum of nodes before sending its writes [24, 25]. However, Riak does not perform synchronous read repair due to the performance penalty [26]. Cassandra does wait for read repair to complete on quorum reads [27], but it loses linearizability if there are multiple concurrent writes to the same key, due to its use of last-write-wins conflict resolution.

Moreover, only linearizable read and write operations can be implemented in this way; a linearizable compare-and-set operation cannot, because it requires a consensus algorithm [28].

In summary, it is safest to assume that a leaderless system with Dynamo-style replication does not provide linearizability.

The Cost of Linearizability

As some replication methods can provide linearizability and others cannot, it is interesting to explore the pros and cons of linearizability in more depth.

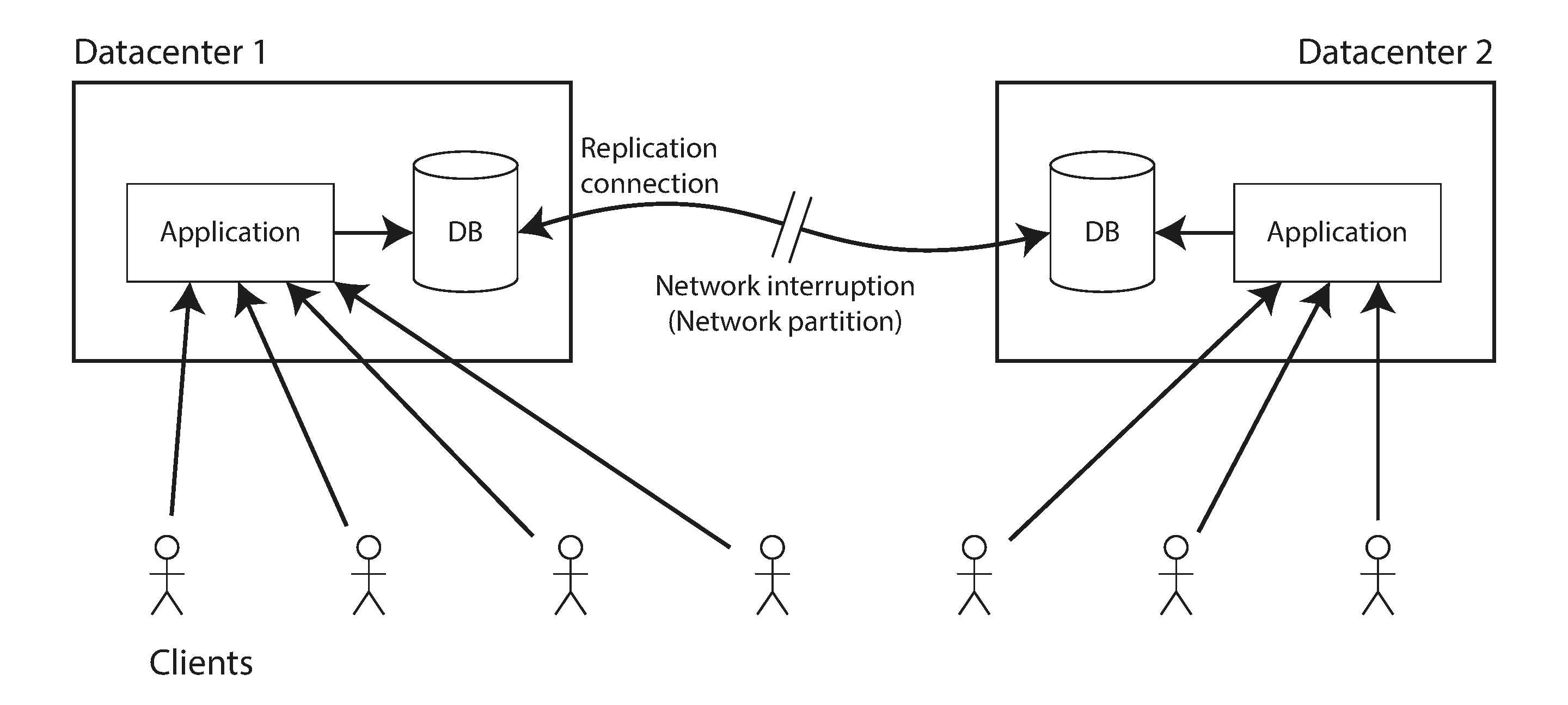

We already discussed some use cases for different replication methods in Chapter 5; for example, we saw that multi-leader replication is often a good choice for multi-datacenter replication (see “Multi-datacenter operation”). An example of such a deployment is illustrated in Figure 9-7.

Figure 9-7. A network interruption forcing a choice between linearizability and availability.

Consider what happens if there is a network interruption between the two datacenters. Let’s assume that the network within each datacenter is working, and clients can reach the datacenters, but the datacenters cannot connect to each other.

With a multi-leader database, each datacenter can continue operating normally: since writes from one datacenter are asynchronously replicated to the other, the writes are simply queued up and exchanged when network connectivity is restored.

On the other hand, if single-leader replication is used, then the leader must be in one of the datacenters. Any writes and any linearizable reads must be sent to the leader—thus, for any clients connected to a follower datacenter, those read and write requests must be sent synchronously over the network to the leader datacenter.

If the network between datacenters is interrupted in a single-leader setup, clients connected to follower datacenters cannot contact the leader, so they cannot make any writes to the database, nor any linearizable reads. They can still make reads from the follower, but they might be stale (nonlinearizable). If the application requires linearizable reads and writes, the network interruption causes the application to become unavailable in the datacenters that cannot contact the leader.

If clients can connect directly to the leader datacenter, this is not a problem, since the application continues to work normally there. But clients that can only reach a follower datacenter will experience an outage until the network link is repaired.

The CAP theorem

This issue is not just a consequence of single-leader and multi-leader replication: any linearizable database has this problem, no matter how it is implemented. The issue also isn’t specific to multi-datacenter deployments, but can occur on any unreliable network, even within one datacenter. The trade-off is as follows:v

-

If your application requires linearizability, and some replicas are disconnected from the other replicas due to a network problem, then some replicas cannot process requests while they are disconnected: they must either wait until the network problem is fixed, or return an error (either way, they become unavailable).

-

If your application does not require linearizability, then it can be written in a way that each replica can process requests independently, even if it is disconnected from other replicas (e.g., multi-leader). In this case, the application can remain available in the face of a network problem, but its behavior is not linearizable.

Thus, applications that don’t require linearizability can be more tolerant of network problems. This insight is popularly known as the CAP theorem [29, 30, 31, 32], named by Eric Brewer in 2000, although the trade-off has been known to designers of distributed databases since the 1970s [33, 34, 35, 36].

CAP was originally proposed as a rule of thumb, without precise definitions, with the goal of starting a discussion about trade-offs in databases. At the time, many distributed databases focused on providing linearizable semantics on a cluster of machines with shared storage [18], and CAP encouraged database engineers to explore a wider design space of distributed shared-nothing systems, which were more suitable for implementing large-scale web services [37]. CAP deserves credit for this culture shift—witness the explosion of new database technologies since the mid-2000s (known as NoSQL).

The CAP theorem as formally defined [30] is of very narrow scope: it only considers one consistency model (namely linearizability) and one kind of fault (network partitions,vi or nodes that are alive but disconnected from each other). It doesn’t say anything about network delays, dead nodes, or other trade-offs. Thus, although CAP has been historically influential, it has little practical value for designing systems [9, 40].

There are many more interesting impossibility results in distributed systems [41], and CAP has now been superseded by more precise results [2, 42], so it is of mostly historical interest today.

Linearizability and network delays

Although linearizability is a useful guarantee, surprisingly few systems are actually linearizable in practice. For example, even RAM on a modern multi-core CPU is not linearizable [43]: if a thread running on one CPU core writes to a memory address, and a thread on another CPU core reads the same address shortly afterward, it is not guaranteed to read the value written by the first thread (unless a memory barrier or fence [44] is used).

The reason for this behavior is that every CPU core has its own memory cache and store buffer. Memory access first goes to the cache by default, and any changes are asynchronously written out to main memory. Since accessing data in the cache is much faster than going to main memory [45], this feature is essential for good performance on modern CPUs. However, there are now several copies of the data (one in main memory, and perhaps several more in various caches), and these copies are asynchronously updated, so linearizability is lost.

Why make this trade-off? It makes no sense to use the CAP theorem to justify the multi-core memory consistency model: within one computer we usually assume reliable communication, and we don’t expect one CPU core to be able to continue operating normally if it is disconnected from the rest of the computer. The reason for dropping linearizability is performance, not fault tolerance.

The same is true of many distributed databases that choose not to provide linearizable guarantees: they do so primarily to increase performance, not so much for fault tolerance [46]. Linearizability is slow—and this is true all the time, not only during a network fault.

Can’t we maybe find a more efficient implementation of linearizable storage? It seems the answer is no: Attiya and Welch [47] prove that if you want linearizability, the response time of read and write requests is at least proportional to the uncertainty of delays in the network. In a network with highly variable delays, like most computer networks (see “Timeouts and Unbounded Delays”), the response time of linearizable reads and writes is inevitably going to be high. A faster algorithm for linearizability does not exist, but weaker consistency models can be much faster, so this trade-off is important for latency-sensitive systems. In Chapter 12 we will discuss some approaches for avoiding linearizability without sacrificing correctness.

Ordering Guarantees

We said previously that a linearizable register behaves as if there is only a single copy of the data, and that every operation appears to take effect atomically at one point in time. This definition implies that operations are executed in some well-defined order. We illustrated the ordering in Figure 9-4 by joining up the operations in the order in which they seem to have executed.

Ordering has been a recurring theme in this book, which suggests that it might be an important fundamental idea. Let’s briefly recap some of the other contexts in which we have discussed ordering:

-

In Chapter 5 we saw that the main purpose of the leader in single-leader replication is to determine the order of writes in the replication log—that is, the order in which followers apply those writes. If there is no single leader, conflicts can occur due to concurrent operations (see “Handling Write Conflicts”).

-

Serializability, which we discussed in Chapter 7, is about ensuring that transactions behave as if they were executed in some sequential order. It can be achieved by literally executing transactions in that serial order, or by allowing concurrent execution while preventing serialization conflicts (by locking or aborting).

-

The use of timestamps and clocks in distributed systems that we discussed in Chapter 8 (see “Relying on Synchronized Clocks”) is another attempt to introduce order into a disorderly world, for example to determine which one of two writes happened later.

It turns out that there are deep connections between ordering, linearizability, and consensus. Although this notion is a bit more theoretical and abstract than the rest of this book, it is very helpful for clarifying our understanding of what systems can and cannot do. We will explore this topic in the next few sections.

Ordering and Causality

There are several reasons why ordering keeps coming up, and one of the reasons is that it helps preserve causality. We have already seen several examples over the course of this book where causality has been important:

-

In “Consistent Prefix Reads” (Figure 5-5) we saw an example where the observer of a conversation saw first the answer to a question, and then the question being answered. This is confusing because it violates our intuition of cause and effect: if a question is answered, then clearly the question had to be there first, because the person giving the answer must have seen the question (assuming they are not psychic and cannot see into the future). We say that there is a causal dependency between the question and the answer.

-

A similar pattern appeared in Figure 5-9, where we looked at the replication between three leaders and noticed that some writes could “overtake” others due to network delays. From the perspective of one of the replicas it would look as though there was an update to a row that did not exist. Causality here means that a row must first be created before it can be updated.

-

In “Detecting Concurrent Writes” we observed that if you have two operations A and B, there are three possibilities: either A happened before B, or B happened before A, or A and B are concurrent. This happened before relationship is another expression of causality: if A happened before B, that means B might have known about A, or built upon A, or depended on A. If A and B are concurrent, there is no causal link between them; in other words, we are sure that neither knew about the other.

-

In the context of snapshot isolation for transactions (“Snapshot Isolation and Repeatable Read”), we said that a transaction reads from a consistent snapshot. But what does “consistent” mean in this context? It means consistent with causality: if the snapshot contains an answer, it must also contain the question being answered [48]. Observing the entire database at a single point in time makes it consistent with causality: the effects of all operations that happened causally before that point in time are visible, but no operations that happened causally afterward can be seen. Read skew (non-repeatable reads, as illustrated in Figure 7-6) means reading data in a state that violates causality.

-

Our examples of write skew between transactions (see “Write Skew and Phantoms”) also demonstrated causal dependencies: in Figure 7-8, Alice was allowed to go off call because the transaction thought that Bob was still on call, and vice versa. In this case, the action of going off call is causally dependent on the observation of who is currently on call. Serializable snapshot isolation (see “Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI)”) detects write skew by tracking the causal dependencies between transactions.

-

In the example of Alice and Bob watching football (Figure 9-1), the fact that Bob got a stale result from the server after hearing Alice exclaim the result is a causality violation: Alice’s exclamation is causally dependent on the announcement of the score, so Bob should also be able to see the score after hearing Alice. The same pattern appeared again in “Cross-channel timing dependencies” in the guise of an image resizing service.

Causality imposes an ordering on events: cause comes before effect; a message is sent before that message is received; the question comes before the answer. And, like in real life, one thing leads to another: one node reads some data and then writes something as a result, another node reads the thing that was written and writes something else in turn, and so on. These chains of causally dependent operations define the causal order in the system—i.e., what happened before what.

If a system obeys the ordering imposed by causality, we say that it is causally consistent. For example, snapshot isolation provides causal consistency: when you read from the database, and you see some piece of data, then you must also be able to see any data that causally precedes it (assuming it has not been deleted in the meantime).

The causal order is not a total order

A total order allows any two elements to be compared, so if you have two elements, you can always say which one is greater and which one is smaller. For example, natural numbers are totally ordered: if I give you any two numbers, say 5 and 13, you can tell me that 13 is greater than 5.

However, mathematical sets are not totally ordered: is {a, b} greater than {b, c}? Well, you can’t really compare them, because neither is a subset of the other. We say they are incomparable, and therefore mathematical sets are partially ordered: in some cases one set is greater than another (if one set contains all the elements of another), but in other cases they are incomparable.

The difference between a total order and a partial order is reflected in different database consistency models:

- Linearizability

-

In a linearizable system, we have a total order of operations: if the system behaves as if there is only a single copy of the data, and every operation is atomic, this means that for any two operations we can always say which one happened first. This total ordering is illustrated as a timeline in Figure 9-4.

- Causality

-

We said that two operations are concurrent if neither happened before the other (see “The “happens-before” relationship and concurrency”). Put another way, two events are ordered if they are causally related (one happened before the other), but they are incomparable if they are concurrent. This means that causality defines a partial order, not a total order: some operations are ordered with respect to each other, but some are incomparable.

Therefore, according to this definition, there are no concurrent operations in a linearizable datastore: there must be a single timeline along which all operations are totally ordered. There might be several requests waiting to be handled, but the datastore ensures that every request is handled atomically at a single point in time, acting on a single copy of the data, along a single timeline, without any concurrency.

Concurrency would mean that the timeline branches and merges again—and in this case, operations on different branches are incomparable (i.e., concurrent). We saw this phenomenon in Chapter 5: for example, Figure 5-14 is not a straight-line total order, but rather a jumble of different operations going on concurrently. The arrows in the diagram indicate causal dependencies—the partial ordering of operations.

If you are familiar with distributed version control systems such as Git, their version histories are very much like the graph of causal dependencies. Often one commit happens after another, in a straight line, but sometimes you get branches (when several people concurrently work on a project), and merges are created when those concurrently created commits are combined.

Linearizability is stronger than causal consistency

So what is the relationship between the causal order and linearizability? The answer is that linearizability implies causality: any system that is linearizable will preserve causality correctly [7]. In particular, if there are multiple communication channels in a system (such as the message queue and the file storage service in Figure 9-5), linearizability ensures that causality is automatically preserved without the system having to do anything special (such as passing around timestamps between different components).

The fact that linearizability ensures causality is what makes linearizable systems simple to understand and appealing. However, as discussed in “The Cost of Linearizability”, making a system linearizable can harm its performance and availability, especially if the system has significant network delays (for example, if it’s geographically distributed). For this reason, some distributed data systems have abandoned linearizability, which allows them to achieve better performance but can make them difficult to work with.

The good news is that a middle ground is possible. Linearizability is not the only way of preserving causality—there are other ways too. A system can be causally consistent without incurring the performance hit of making it linearizable (in particular, the CAP theorem does not apply). In fact, causal consistency is the strongest possible consistency model that does not slow down due to network delays, and remains available in the face of network failures [2, 42].

In many cases, systems that appear to require linearizability in fact only really require causal consistency, which can be implemented more efficiently. Based on this observation, researchers are exploring new kinds of databases that preserve causality, with performance and availability characteristics that are similar to those of eventually consistent systems [49, 50, 51].

As this research is quite recent, not much of it has yet made its way into production systems, and there are still challenges to be overcome [52, 53]. However, it is a promising direction for future systems.

Capturing causal dependencies

We won’t go into all the nitty-gritty details of how nonlinearizable systems can maintain causal consistency here, but just briefly explore some of the key ideas.

In order to maintain causality, you need to know which operation happened before which other operation. This is a partial order: concurrent operations may be processed in any order, but if one operation happened before another, then they must be processed in that order on every replica. Thus, when a replica processes an operation, it must ensure that all causally preceding operations (all operations that happened before) have already been processed; if some preceding operation is missing, the later operation must wait until the preceding operation has been processed.

In order to determine causal dependencies, we need some way of describing the “knowledge” of a node in the system. If a node had already seen the value X when it issued the write Y, then X and Y may be causally related. The analysis uses the kinds of questions you would expect in a criminal investigation of fraud charges: did the CEO know about X at the time when they made decision Y?

The techniques for determining which operation happened before which other operation are similar to what we discussed in “Detecting Concurrent Writes”. That section discussed causality in a leaderless datastore, where we need to detect concurrent writes to the same key in order to prevent lost updates. Causal consistency goes further: it needs to track causal dependencies across the entire database, not just for a single key. Version vectors can be generalized to do this [54].

In order to determine the causal ordering, the database needs to know which version of the data was read by the application. This is why, in Figure 5-13, the version number from the prior operation is passed back to the database on a write. A similar idea appears in the conflict detection of SSI, as discussed in “Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI)”: when a transaction wants to commit, the database checks whether the version of the data that it read is still up to date. To this end, the database keeps track of which data has been read by which transaction.

Sequence Number Ordering

Although causality is an important theoretical concept, actually keeping track of all causal dependencies can become impractical. In many applications, clients read lots of data before writing something, and then it is not clear whether the write is causally dependent on all or only some of those prior reads. Explicitly tracking all the data that has been read would mean a large overhead.

However, there is a better way: we can use sequence numbers or timestamps to order events. A timestamp need not come from a time-of-day clock (or physical clock, which have many problems, as discussed in “Unreliable Clocks”). It can instead come from a logical clock, which is an algorithm to generate a sequence of numbers to identify operations, typically using counters that are incremented for every operation.

Such sequence numbers or timestamps are compact (only a few bytes in size), and they provide a total order: that is, every operation has a unique sequence number, and you can always compare two sequence numbers to determine which is greater (i.e., which operation happened later).

In particular, we can create sequence numbers in a total order that is consistent with causality:vii we promise that if operation A causally happened before B, then A occurs before B in the total order (A has a lower sequence number than B). Concurrent operations may be ordered arbitrarily. Such a total order captures all the causality information, but also imposes more ordering than strictly required by causality.

In a database with single-leader replication (see “Leaders and Followers”), the replication log defines a total order of write operations that is consistent with causality. The leader can simply increment a counter for each operation, and thus assign a monotonically increasing sequence number to each operation in the replication log. If a follower applies the writes in the order they appear in the replication log, the state of the follower is always causally consistent (even if it is lagging behind the leader).

Noncausal sequence number generators

If there is not a single leader (perhaps because you are using a multi-leader or leaderless database, or because the database is partitioned), it is less clear how to generate sequence numbers for operations. Various methods are used in practice:

-

Each node can generate its own independent set of sequence numbers. For example, if you have two nodes, one node can generate only odd numbers and the other only even numbers. In general, you could reserve some bits in the binary representation of the sequence number to contain a unique node identifier, and this would ensure that two different nodes can never generate the same sequence number.

-

You can attach a timestamp from a time-of-day clock (physical clock) to each operation [55]. Such timestamps are not sequential, but if they have sufficiently high resolution, they might be sufficient to totally order operations. This fact is used in the last write wins conflict resolution method (see “Timestamps for ordering events”).

-

You can preallocate blocks of sequence numbers. For example, node A might claim the block of sequence numbers from 1 to 1,000, and node B might claim the block from 1,001 to 2,000. Then each node can independently assign sequence numbers from its block, and allocate a new block when its supply of sequence numbers begins to run low.

These three options all perform better and are more scalable than pushing all operations through a single leader that increments a counter. They generate a unique, approximately increasing sequence number for each operation. However, they all have a problem: the sequence numbers they generate are not consistent with causality.

The causality problems occur because these sequence number generators do not correctly capture the ordering of operations across different nodes:

-

Each node may process a different number of operations per second. Thus, if one node generates even numbers and the other generates odd numbers, the counter for even numbers may lag behind the counter for odd numbers, or vice versa. If you have an odd-numbered operation and an even-numbered operation, you cannot accurately tell which one causally happened first.

-

Timestamps from physical clocks are subject to clock skew, which can make them inconsistent with causality. For example, see Figure 8-3, which shows a scenario in which an operation that happened causally later was actually assigned a lower timestamp.viii

-

In the case of the block allocator, one operation may be given a sequence number in the range from 1,001 to 2,000, and a causally later operation may be given a number in the range from 1 to 1,000. Here, again, the sequence number is inconsistent with causality.

Lamport timestamps

Although the three sequence number generators just described are inconsistent with causality, there is actually a simple method for generating sequence numbers that is consistent with causality. It is called a Lamport timestamp, proposed in 1978 by Leslie Lamport [56], in what is now one of the most-cited papers in the field of distributed systems.

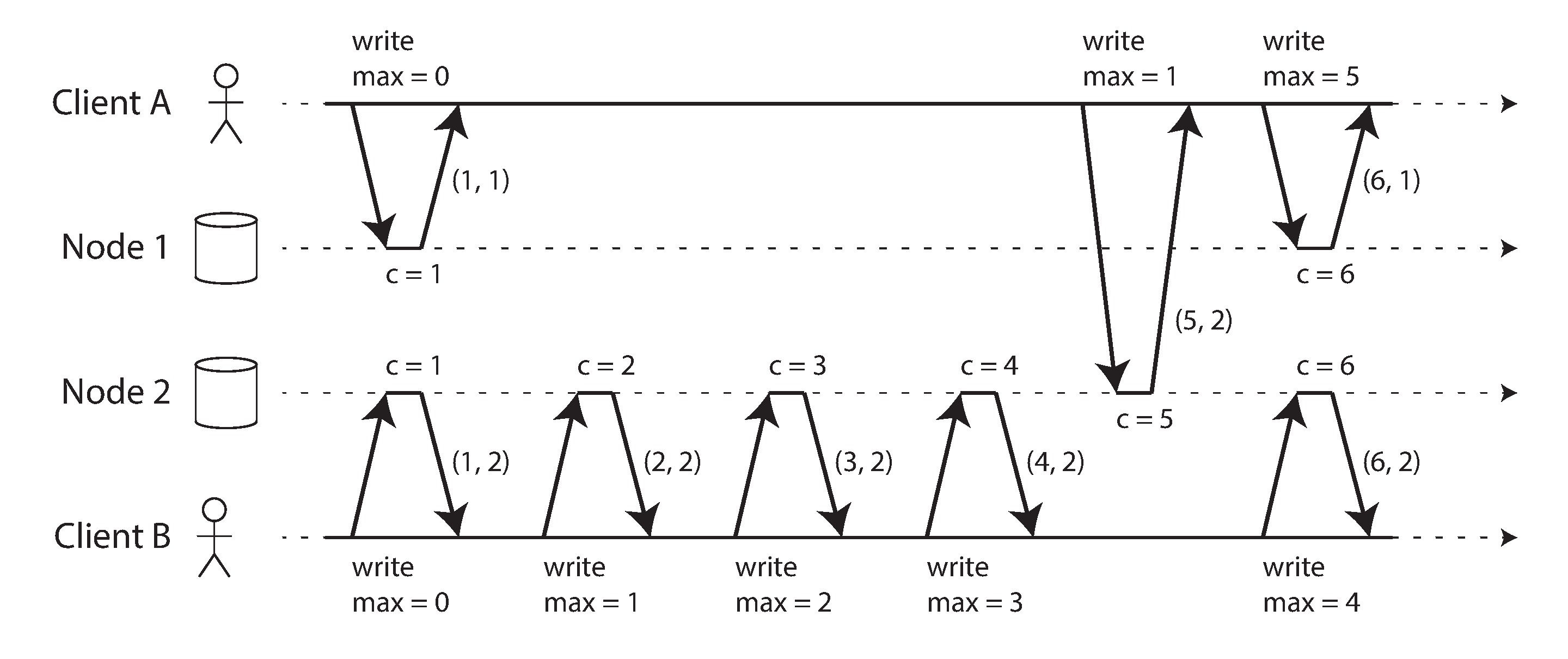

The use of Lamport timestamps is illustrated in Figure 9-8. Each node has a unique identifier, and each node keeps a counter of the number of operations it has processed. The Lamport timestamp is then simply a pair of (counter, node ID). Two nodes may sometimes have the same counter value, but by including the node ID in the timestamp, each timestamp is made unique.

Figure 9-8. Lamport timestamps provide a total ordering consistent with causality.

A Lamport timestamp bears no relationship to a physical time-of-day clock, but it provides total ordering: if you have two timestamps, the one with a greater counter value is the greater timestamp; if the counter values are the same, the one with the greater node ID is the greater timestamp.

So far this description is essentially the same as the even/odd counters described in the last section. The key idea about Lamport timestamps, which makes them consistent with causality, is the following: every node and every client keeps track of the maximum counter value it has seen so far, and includes that maximum on every request. When a node receives a request or response with a maximum counter value greater than its own counter value, it immediately increases its own counter to that maximum.

This is shown in Figure 9-8, where client A receives a counter value of 5 from node 2, and then sends that maximum of 5 to node 1. At that time, node 1’s counter was only 1, but it was immediately moved forward to 5, so the next operation had an incremented counter value of 6.

As long as the maximum counter value is carried along with every operation, this scheme ensures that the ordering from the Lamport timestamps is consistent with causality, because every causal dependency results in an increased timestamp.

Lamport timestamps are sometimes confused with version vectors, which we saw in “Detecting Concurrent Writes”. Although there are some similarities, they have a different purpose: version vectors can distinguish whether two operations are concurrent or whether one is causally dependent on the other, whereas Lamport timestamps always enforce a total ordering. From the total ordering of Lamport timestamps, you cannot tell whether two operations are concurrent or whether they are causally dependent. The advantage of Lamport timestamps over version vectors is that they are more compact.

Timestamp ordering is not sufficient

Although Lamport timestamps define a total order of operations that is consistent with causality, they are not quite sufficient to solve many common problems in distributed systems.

For example, consider a system that needs to ensure that a username uniquely identifies a user account. If two users concurrently try to create an account with the same username, one of the two should succeed and the other should fail. (We touched on this problem previously in “The leader and the lock”.)

At first glance, it seems as though a total ordering of operations (e.g., using Lamport timestamps) should be sufficient to solve this problem: if two accounts with the same username are created, pick the one with the lower timestamp as the winner (the one who grabbed the username first), and let the one with the greater timestamp fail. Since timestamps are totally ordered, this comparison is always valid.

This approach works for determining the winner after the fact: once you have collected all the username creation operations in the system, you can compare their timestamps. However, it is not sufficient when a node has just received a request from a user to create a username, and needs to decide right now whether the request should succeed or fail. At that moment, the node does not know whether another node is concurrently in the process of creating an account with the same username, and what timestamp that other node may assign to the operation.

In order to be sure that no other node is in the process of concurrently creating an account with the same username and a lower timestamp, you would have to check with every other node to see what it is doing [56]. If one of the other nodes has failed or cannot be reached due to a network problem, this system would grind to a halt. This is not the kind of fault-tolerant system that we need.

The problem here is that the total order of operations only emerges after you have collected all of the operations. If another node has generated some operations, but you don’t yet know what they are, you cannot construct the final ordering of operations: the unknown operations from the other node may need to be inserted at various positions in the total order.

To conclude: in order to implement something like a uniqueness constraint for usernames, it’s not sufficient to have a total ordering of operations—you also need to know when that order is finalized. If you have an operation to create a username, and you are sure that no other node can insert a claim for the same username ahead of your operation in the total order, then you can safely declare the operation successful.

This idea of knowing when your total order is finalized is captured in the topic of total order broadcast.

Total Order Broadcast

If your program runs only on a single CPU core, it is easy to define a total ordering of operations: it is simply the order in which they were executed by the CPU. However, in a distributed system, getting all nodes to agree on the same total ordering of operations is tricky. In the last section we discussed ordering by timestamps or sequence numbers, but found that it is not as powerful as single-leader replication (if you use timestamp ordering to implement a uniqueness constraint, you cannot tolerate any faults).

As discussed, single-leader replication determines a total order of operations by choosing one node as the leader and sequencing all operations on a single CPU core on the leader. The challenge then is how to scale the system if the throughput is greater than a single leader can handle, and also how to handle failover if the leader fails (see “Handling Node Outages”). In the distributed systems literature, this problem is known as total order broadcast or atomic broadcast [25, 57, 58].ix

Scope of ordering guarantee

Partitioned databases with a single leader per partition often maintain ordering only per partition, which means they cannot offer consistency guarantees (e.g., consistent snapshots, foreign key references) across partitions. Total ordering across all partitions is possible, but requires additional coordination [59].

Total order broadcast is usually described as a protocol for exchanging messages between nodes. Informally, it requires that two safety properties always be satisfied:

- Reliable delivery

-

No messages are lost: if a message is delivered to one node, it is delivered to all nodes.

- Totally ordered delivery

-

Messages are delivered to every node in the same order.

A correct algorithm for total order broadcast must ensure that the reliability and ordering properties are always satisfied, even if a node or the network is faulty. Of course, messages will not be delivered while the network is interrupted, but an algorithm can keep retrying so that the messages get through when the network is eventually repaired (and then they must still be delivered in the correct order).

Using total order broadcast

Consensus services such as ZooKeeper and etcd actually implement total order broadcast. This fact is a hint that there is a strong connection between total order broadcast and consensus, which we will explore later in this chapter.

Total order broadcast is exactly what you need for database replication: if every message represents a write to the database, and every replica processes the same writes in the same order, then the replicas will remain consistent with each other (aside from any temporary replication lag). This principle is known as state machine replication [60], and we will return to it in Chapter 11.

Similarly, total order broadcast can be used to implement serializable transactions: as discussed in “Actual Serial Execution”, if every message represents a deterministic transaction to be executed as a stored procedure, and if every node processes those messages in the same order, then the partitions and replicas of the database are kept consistent with each other [61].

An important aspect of total order broadcast is that the order is fixed at the time the messages are delivered: a node is not allowed to retroactively insert a message into an earlier position in the order if subsequent messages have already been delivered. This fact makes total order broadcast stronger than timestamp ordering.

Another way of looking at total order broadcast is that it is a way of creating a log (as in a replication log, transaction log, or write-ahead log): delivering a message is like appending to the log. Since all nodes must deliver the same messages in the same order, all nodes can read the log and see the same sequence of messages.

Total order broadcast is also useful for implementing a lock service that provides fencing tokens

(see “Fencing tokens”). Every request to acquire the lock is appended as a message

to the log, and all messages are sequentially numbered in the order they appear in the log. The

sequence number can then serve as a fencing token, because it is monotonically increasing. In

ZooKeeper, this sequence number is called zxid

[15].

Implementing linearizable storage using total order broadcast

As illustrated in Figure 9-4, in a linearizable system there is a total order of operations. Does that mean linearizability is the same as total order broadcast? Not quite, but there are close links between the two.x

Total order broadcast is asynchronous: messages are guaranteed to be delivered reliably in a fixed order, but there is no guarantee about when a message will be delivered (so one recipient may lag behind the others). By contrast, linearizability is a recency guarantee: a read is guaranteed to see the latest value written.

However, if you have total order broadcast, you can build linearizable storage on top of it. For example, you can ensure that usernames uniquely identify user accounts.

Imagine that for every possible username, you can have a linearizable register with an atomic

compare-and-set operation. Every register initially has the value null (indicating that the

username is not taken). When a user wants to create a username, you execute a compare-and-set

operation on the register for that username, setting it to the user account ID, under the condition

that the previous register value is null. If multiple users try to concurrently grab the same

username, only one of the compare-and-set operations will succeed, because the others will see a

value other than null (due to linearizability).

You can implement such a linearizable compare-and-set operation as follows by using total order broadcast as an append-only log [62, 63]:

-

Append a message to the log, tentatively indicating the username you want to claim.

-

Read the log, and wait for the message you appended to be delivered back to you.xi

-

Check for any messages claiming the username that you want. If the first message for your desired username is your own message, then you are successful: you can commit the username claim (perhaps by appending another message to the log) and acknowledge it to the client. If the first message for your desired username is from another user, you abort the operation.

Because log entries are delivered to all nodes in the same order, if there are several concurrent writes, all nodes will agree on which one came first. Choosing the first of the conflicting writes as the winner and aborting later ones ensures that all nodes agree on whether a write was committed or aborted. A similar approach can be used to implement serializable multi-object transactions on top of a log [62].

While this procedure ensures linearizable writes, it doesn’t guarantee linearizable reads—if you read from a store that is asynchronously updated from the log, it may be stale. (To be precise, the procedure described here provides sequential consistency [47, 64], sometimes also known as timeline consistency [65, 66], a slightly weaker guarantee than linearizability.) To make reads linearizable, there are a few options:

-

You can sequence reads through the log by appending a message, reading the log, and performing the actual read when the message is delivered back to you. The message’s position in the log thus defines the point in time at which the read happens. (Quorum reads in etcd work somewhat like this [16].)

-

If the log allows you to fetch the position of the latest log message in a linearizable way, you can query that position, wait for all entries up to that position to be delivered to you, and then perform the read. (This is the idea behind ZooKeeper’s

sync()operation [15].) -

You can make your read from a replica that is synchronously updated on writes, and is thus sure to be up to date. (This technique is used in chain replication [63]; see also “Research on Replication”.)

Implementing total order broadcast using linearizable storage

The last section showed how to build a linearizable compare-and-set operation from total order broadcast. We can also turn it around, assume that we have linearizable storage, and show how to build total order broadcast from it.

The easiest way is to assume you have a linearizable register that stores an integer and that has an atomic increment-and-get operation [28]. Alternatively, an atomic compare-and-set operation would also do the job.

The algorithm is simple: for every message you want to send through total order broadcast, you increment-and-get the linearizable integer, and then attach the value you got from the register as a sequence number to the message. You can then send the message to all nodes (resending any lost messages), and the recipients will deliver the messages consecutively by sequence number.

Note that unlike Lamport timestamps, the numbers you get from incrementing the linearizable register form a sequence with no gaps. Thus, if a node has delivered message 4 and receives an incoming message with a sequence number of 6, it knows that it must wait for message 5 before it can deliver message 6. The same is not the case with Lamport timestamps—in fact, this is the key difference between total order broadcast and timestamp ordering.

How hard could it be to make a linearizable integer with an atomic increment-and-get operation? As usual, if things never failed, it would be easy: you could just keep it in a variable on one node. The problem lies in handling the situation when network connections to that node are interrupted, and restoring the value when that node fails [59]. In general, if you think hard enough about linearizable sequence number generators, you inevitably end up with a consensus algorithm.

This is no coincidence: it can be proved that a linearizable compare-and-set (or increment-and-get) register and total order broadcast are both equivalent to consensus [28, 67]. That is, if you can solve one of these problems, you can transform it into a solution for the others. This is quite a profound and surprising insight!

It is time to finally tackle the consensus problem head-on, which we will do in the rest of this chapter.

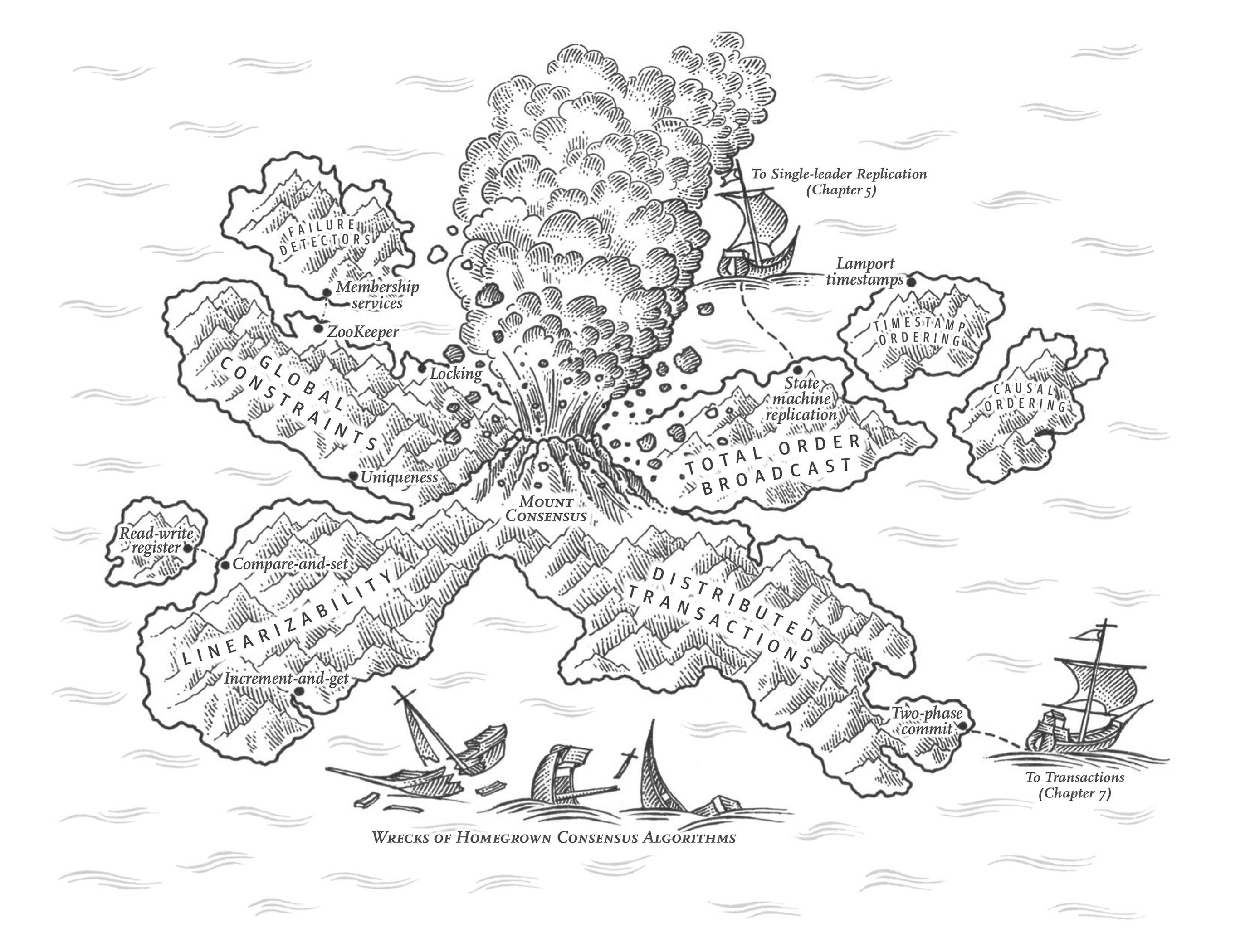

Distributed Transactions and Consensus

Consensus is one of the most important and fundamental problems in distributed computing. On the surface, it seems simple: informally, the goal is simply to get several nodes to agree on something. You might think that this shouldn’t be too hard. Unfortunately, many broken systems have been built in the mistaken belief that this problem is easy to solve.

Although consensus is very important, the section about it appears late in this book because the topic is quite subtle, and appreciating the subtleties requires some prerequisite knowledge. Even in the academic research community, the understanding of consensus only gradually crystallized over the course of decades, with many misunderstandings along the way. Now that we have discussed replication (Chapter 5), transactions (Chapter 7), system models (Chapter 8), linearizability, and total order broadcast (this chapter), we are finally ready to tackle the consensus problem.

There are a number of situations in which it is important for nodes to agree. For example:

- Leader election

-

In a database with single-leader replication, all nodes need to agree on which node is the leader. The leadership position might become contested if some nodes can’t communicate with others due to a network fault. In this case, consensus is important to avoid a bad failover, resulting in a split brain situation in which two nodes both believe themselves to be the leader (see “Handling Node Outages”). If there were two leaders, they would both accept writes and their data would diverge, leading to inconsistency and data loss.

- Atomic commit

-

In a database that supports transactions spanning several nodes or partitions, we have the problem that a transaction may fail on some nodes but succeed on others. If we want to maintain transaction atomicity (in the sense of ACID; see “Atomicity”), we have to get all nodes to agree on the outcome of the transaction: either they all abort/roll back (if anything goes wrong) or they all commit (if nothing goes wrong). This instance of consensus is known as the atomic commit problem.xii

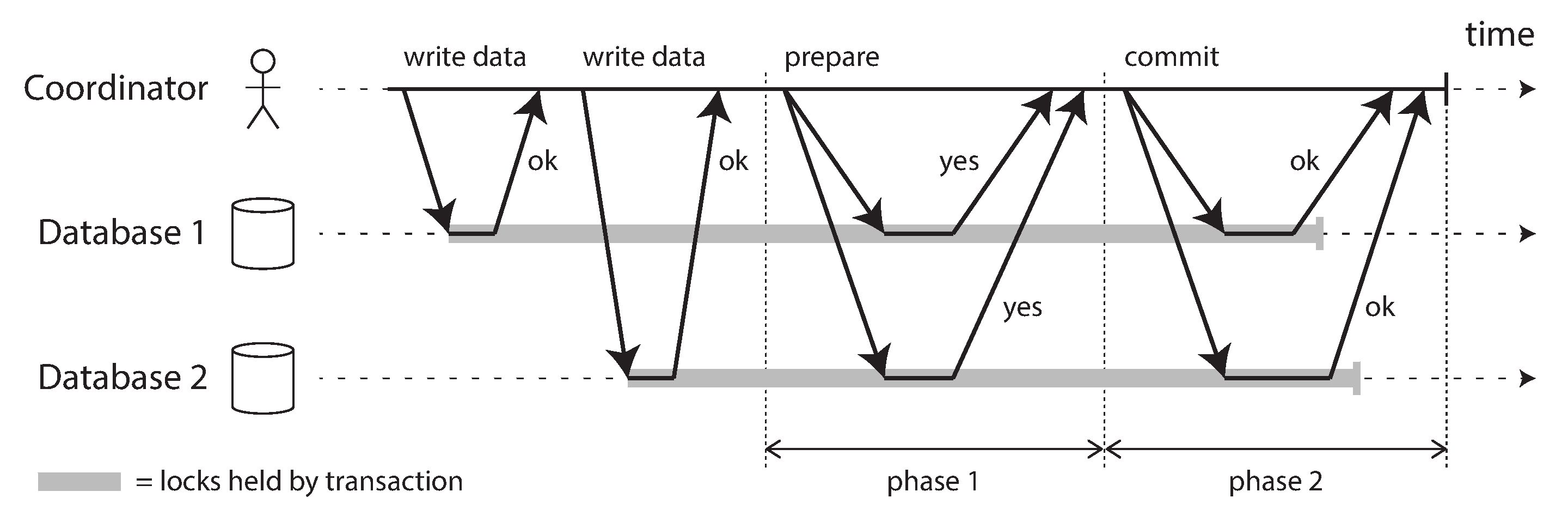

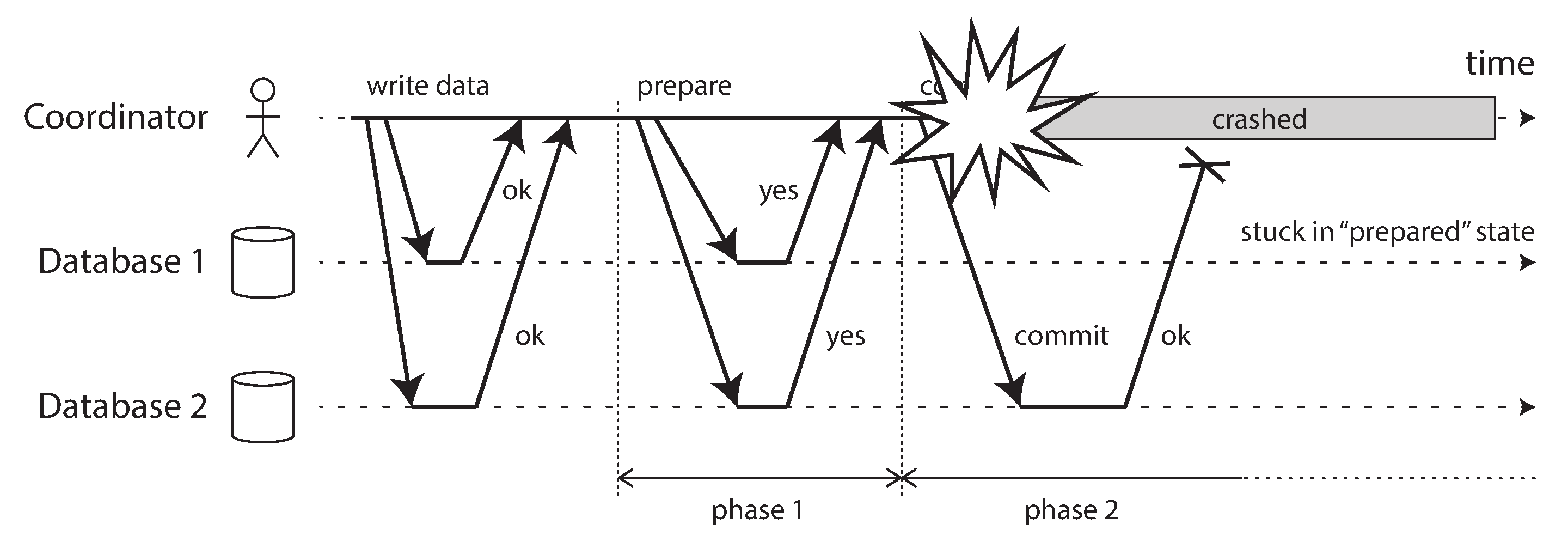

In this section we will first examine the atomic commit problem in more detail. In particular, we will discuss the two-phase commit (2PC) algorithm, which is the most common way of solving atomic commit and which is implemented in various databases, messaging systems, and application servers. It turns out that 2PC is a kind of consensus algorithm—but not a very good one [70, 71].

By learning from 2PC we will then work our way toward better consensus algorithms, such as those used in ZooKeeper (Zab) and etcd (Raft).

Atomic Commit and Two-Phase Commit (2PC)

In Chapter 7 we learned that the purpose of transaction atomicity is to provide simple semantics in the case where something goes wrong in the middle of making several writes. The outcome of a transaction is either a successful commit, in which case all of the transaction’s writes are made durable, or an abort, in which case all of the transaction’s writes are rolled back (i.e., undone or discarded).

Atomicity prevents failed transactions from littering the database with half-finished results and half-updated state. This is especially important for multi-object transactions (see “Single-Object and Multi-Object Operations”) and databases that maintain secondary indexes. Each secondary index is a separate data structure from the primary data—thus, if you modify some data, the corresponding change needs to also be made in the secondary index. Atomicity ensures that the secondary index stays consistent with the primary data (if the index became inconsistent with the primary data, it would not be very useful).

From single-node to distributed atomic commit

For transactions that execute at a single database node, atomicity is commonly implemented by the storage engine. When the client asks the database node to commit the transaction, the database makes the transaction’s writes durable (typically in a write-ahead log; see “Making B-trees reliable”) and then appends a commit record to the log on disk. If the database crashes in the middle of this process, the transaction is recovered from the log when the node restarts: if the commit record was successfully written to disk before the crash, the transaction is considered committed; if not, any writes from that transaction are rolled back.

Thus, on a single node, transaction commitment crucially depends on the order in which data is durably written to disk: first the data, then the commit record [72]. The key deciding moment for whether the transaction commits or aborts is the moment at which the disk finishes writing the commit record: before that moment, it is still possible to abort (due to a crash), but after that moment, the transaction is committed (even if the database crashes). Thus, it is a single device (the controller of one particular disk drive, attached to one particular node) that makes the commit atomic.

However, what if multiple nodes are involved in a transaction? For example, perhaps you have a multi-object transaction in a partitioned database, or a term-partitioned secondary index (in which the index entry may be on a different node from the primary data; see “Partitioning and Secondary Indexes”). Most “NoSQL” distributed datastores do not support such distributed transactions, but various clustered relational systems do (see “Distributed Transactions in Practice”).

In these cases, it is not sufficient to simply send a commit request to all of the nodes and independently commit the transaction on each one. In doing so, it could easily happen that the commit succeeds on some nodes and fails on other nodes, which would violate the atomicity guarantee:

-

Some nodes may detect a constraint violation or conflict, making an abort necessary, while other nodes are successfully able to commit.

-

Some of the commit requests might be lost in the network, eventually aborting due to a timeout, while other commit requests get through.

-

Some nodes may crash before the commit record is fully written and roll back on recovery, while others successfully commit.

If some nodes commit the transaction but others abort it, the nodes become inconsistent with each other (like in Figure 7-3). And once a transaction has been committed on one node, it cannot be retracted again if it later turns out that it was aborted on another node. For this reason, a node must only commit once it is certain that all other nodes in the transaction are also going to commit.

A transaction commit must be irrevocable—you are not allowed to change your mind and retroactively abort a transaction after it has been committed. The reason for this rule is that once data has been committed, it becomes visible to other transactions, and thus other clients may start relying on that data; this principle forms the basis of read committed isolation, discussed in “Read Committed”. If a transaction was allowed to abort after committing, any transactions that read the committed data would be based on data that was retroactively declared not to have existed—so they would have to be reverted as well.

(It is possible for the effects of a committed transaction to later be undone by another, compensating transaction [73, 74]. However, from the database’s point of view this is a separate transaction, and thus any cross-transaction correctness requirements are the application’s problem.)

Introduction to two-phase commit

Two-phase commit is an algorithm for achieving atomic transaction commit across multiple nodes—i.e., to ensure that either all nodes commit or all nodes abort. It is a classic algorithm in distributed databases [13, 35, 75]. 2PC is used internally in some databases and also made available to applications in the form of XA transactions [76, 77] (which are supported by the Java Transaction API, for example) or via WS-AtomicTransaction for SOAP web services [78, 79].