Chapter 2. Jasmine

What Is Jasmine?

Jasmine is a behavior-driven testing framework for JavaScript programming language. It’s a bunch of tools that you can use to test JavaScript code.

As you learned in the previous chapter, you can test your code against specifications that you write. If your code should work in a certain way, Jasmine helps you express that intention in code.

(By the way: if you’ve played around with RSpec for testing Ruby, Jasmine will look suspiciously familiar.)

Getting Set Up with Jasmine

Start by downloading the latest standalone release of Jasmine. Unzip it.

Note

Throughout this book, we’ll mostly be using browser-based Jasmine for various reasons. If you’d prefer a different environment (Node.js, Ruby/Rails, or other environments), take a look at Chapter 7, or the Jasmine wiki. These instructions are for a browser-based environment.

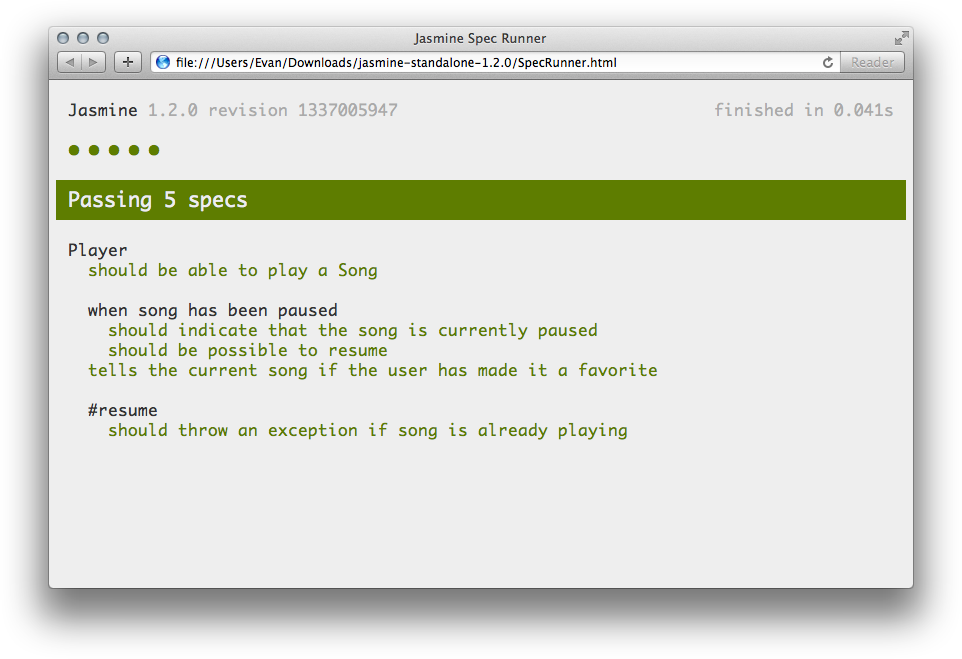

When you open SpecRunner.html in a web browser, you’ll see something like Figure 2-1.

This file has run some example tests on some example code. It’s testing a Player and a Song. Whenever you want to run the tests, you simply need to load/reload this page.

In the src directory, you’ll see two things to be tested: a Player and a Song. The spec directory has tests for the Player. Taking a look inside the spec directory might help you understand Jasmine’s syntax (though there’s also this fine book to help with that).

You probably don’t want to test this example code, so you should empty out the spec and src directories. When you change the filenames, you’ll have to edit SpecRunner.html to point to the right files (there are comments that indicate what you should change). We’ll go through how to do that next.

Testing Existing Code with describe, it, and expect

To learn Jasmine, let’s write some example code and then test it with Jasmine.

An Example to Test

First, let’s create a simple function and test its behavior. It’ll say hello to the entire world. It could look something like this:

function helloWorld() {

return "Hello world!";

}You’re pretty sure that this works, but you want to test it with Jasmine to see what it thinks. Start by saving this in the src directory as hello.js. Open up your SpecRunner.html file to include it:

<!-- put this code somewhere in the <head>... --> <script type="text/javascript" src="src/hello.js"></script>

Note that the order doesn’t matter—you can put the specs before or after the source files.

Jasmine Time!

Next is the Jasmine part. Get ready to get your money’s worth for this book.

Make a file that includes the following code:

describe("Hello world", function() {

it("says hello", function() {

expect(helloWorld()).toEqual("Hello world!");

});

});describe("Hello world"… is what is called a suite. The name of the suite (“Hello world” in this case) typically defines a component of your application; this could be a class, a function, or maybe something else fun. This suite is called “Hello world”; it’s a string of English, not code.

Inside of that suite (technically, inside of an anonymous function), is the it() block. This is called a specification, or a spec for short. It’s a JavaScript function that says what some small piece of your component should do. It says it in plain English (“says hello”) and in code. For each suite, you can have any number of specs for the tests you want to run.

In this case, you’re testing if helloWorld() does indeed return "Hello world!". This check is called a matcher. Jasmine includes a number of predefined matchers, but you can also define your own (we’ll get to that in Chapter 4). We expect the output of helloWorld() to equal (toEqual) the string "Hello world!".

Jasmine aims to read like English, so it’s possible that you were able to intuit how this example worked just by looking at it. If not, don’t worry!

Save that code as hello.spec.js, put it in the spec directory, and make sure that your spec runner knows about it:

<!-- put this code somewhere in the <head>... --> <script type="text/javascript" src="spec/hello.spec.js"></script>

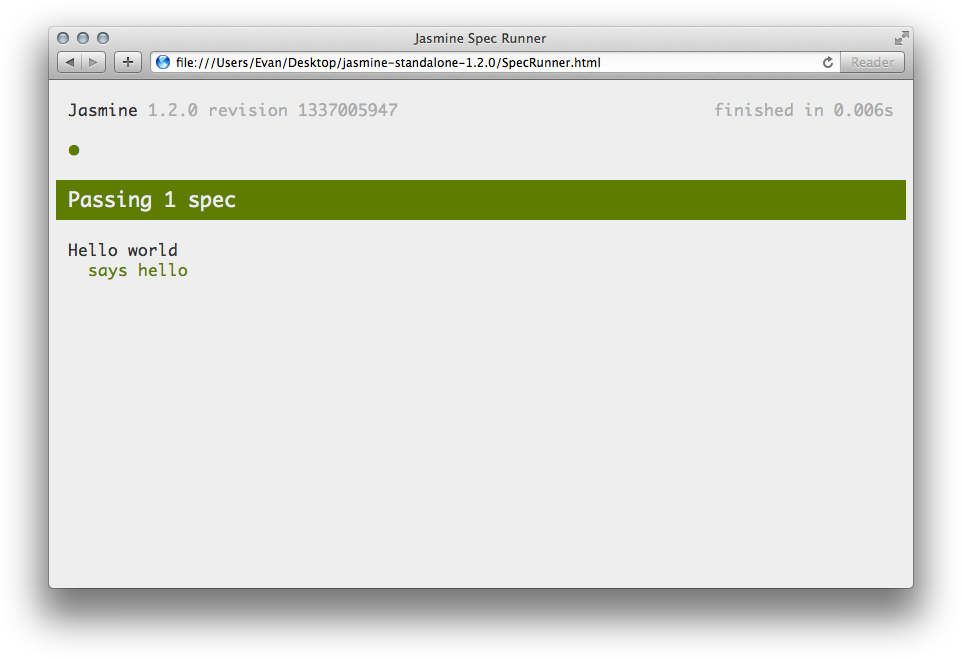

If you run this spec in the browser, you’ll see the output shown in Figure 2-2.

Success!

Go into the helloWorld() function and make it say something other than “Hello world!”. When you run the specs again, Jasmine will complain. That’s what you want; Jasmine should tell you when you’ve done something you didn’t intend to.

Matchers

In the previous example, you were checking to see if helloWorld() was indeed equal to "Hello world!". You used the function toEqual(), which—as noted earlier—is a matcher. This basically takes the argument to the expect function (which is helloWorld(), in this case) and checks to see if it satisfies some criterion in the matcher. In the preceding example, it checks if the argument is equal to something else.

But what if we wanted to expect it to contain the word “world,” but we don’t care what else is in there? We just want it to say “world.” Easy peasy; we just need to use a different matcher: toContain. Have a look:

describe("Hello world", function() {

it("says world", function() {

expect(helloWorld()).toContain("world");

});

});Instead of expecting something to equal “Hello world!”, I’m now just expecting it to contain “world.” It even reads like English! There are a lot of bundled matchers, and you can even make your own. We’ll learn how to do that in Chapter 4.

Writing the Tests First with Test-Driven Development

Jasmine can easily test existing code; you write the code first and test it second. Test-driven development is the opposite: you write the tests first, and then “fill in” the tests with code.

As an example, let’s try using test-driven development (TDD) to make a “disemvoweler.” A disemvoweler removes all vowels from a string (let’s assume that the letter y isn’t a vowel in this example, and that we’re dealing with English). What does our disemvoweler do (i.e. what does the specification look like)?

- It should remove all lowercase vowels.

- It should remove all uppercase vowels.

- It shouldn’t change empty strings.

- It shouldn’t change strings with no vowels.

Now, let’s think of some examples that would test the preceding specifications:

- Remove all lowercase vowels: “Hello world” should become “Hll wrld”.

- Remove all uppercase vowels: “Artistic Eagle” should become “rtstc gl”.

- Don’t change empty strings: “” should stay “”.

- Don’t change strings with no vowels: “Mhmm” should stay “Mhmm”.

Jasmine makes it easy to codify these specifications:

describe("Disemvoweler", function() {

it("should remove all lowercase vowels", function() {

expect(disemvowel("Hello world")).toEqual("Hll wrld");

});

it("should remove all uppercase vowels", function() {

expect(disemvowel("Artistic Eagle")).toEqual("rtstc gl");

});

it("shouldn't change empty strings", function() {

expect(disemvowel("")).toEqual("");

});

it("shouldn't change strings with no vowels", function() {

expect(disemvowel("Mhmm")).toEqual("Mhmm");

});

});Save this code into spec/DisemvowelSpec.js and include it in SpecRunner.html:

<script type="text/javascript" src="spec/DisemvowelSpec.js"></script>

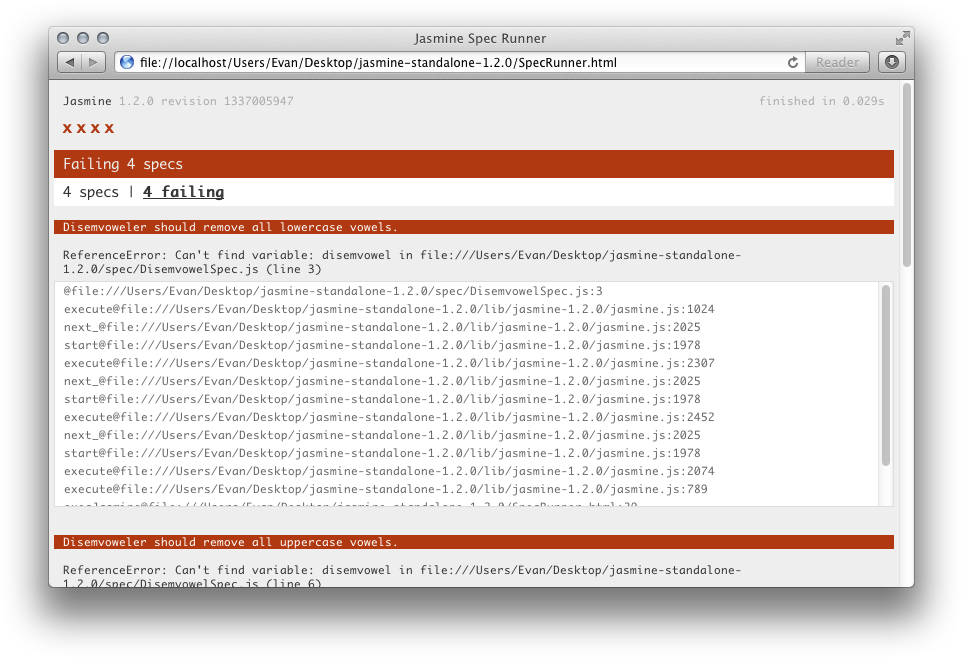

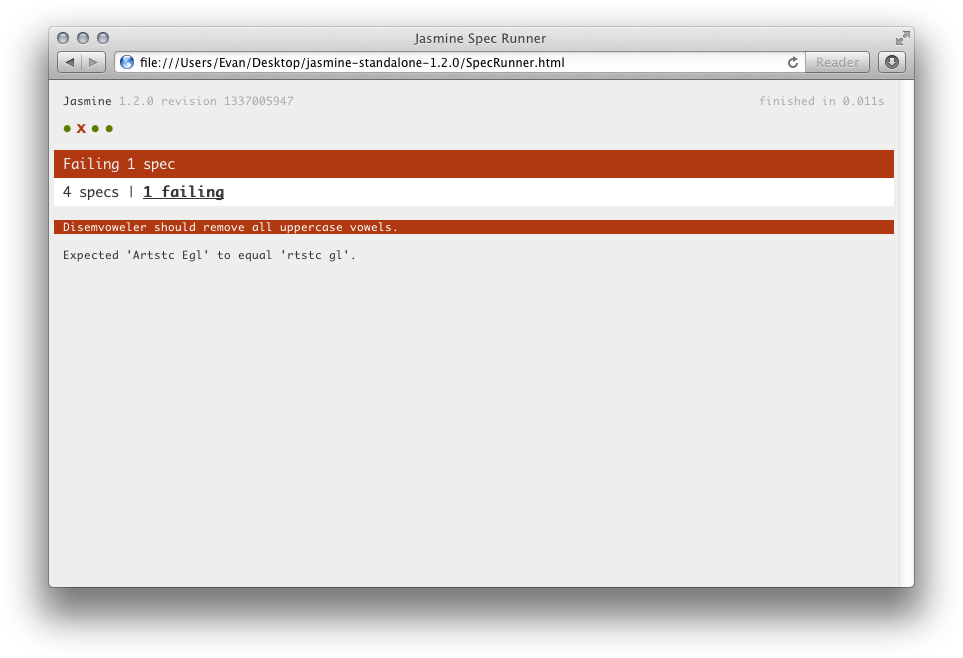

If you refresh the spec runner, you’ll see what’s shown in Figure 2-3.

All of your specs fail! This is expected—you haven’t written any of the code yet, so Jasmine can’t find any function called disemvowel. It’s helpful to see your tests fail because you know you’re protected against false positives this way. (If a test passed with no code written, something is wrong!)

Let’s write a first version of our disemvoweler:

function disemvowel(str) {

return str.replace(/a|e|i|o|u/g, "");

}This code uses a regular expression to substitute any vowel with an empty string. Save this into src/Disemvowel.js and add that into the spec runner:

<script type="text/javascript" src="src/Disemvowel.js"></script>

Refresh the spec runner, and you should see something like Figure 2-4.

Instead of all of the specs failing, only one is failing now. It looks like the disemvoweler isn’t removing all the uppercase vowels. Jasmine helps us see where the problem is: our first version wouldn’t remove any uppercase vowels. Let’s add the case-insensitive flag (i) to our regular expression:

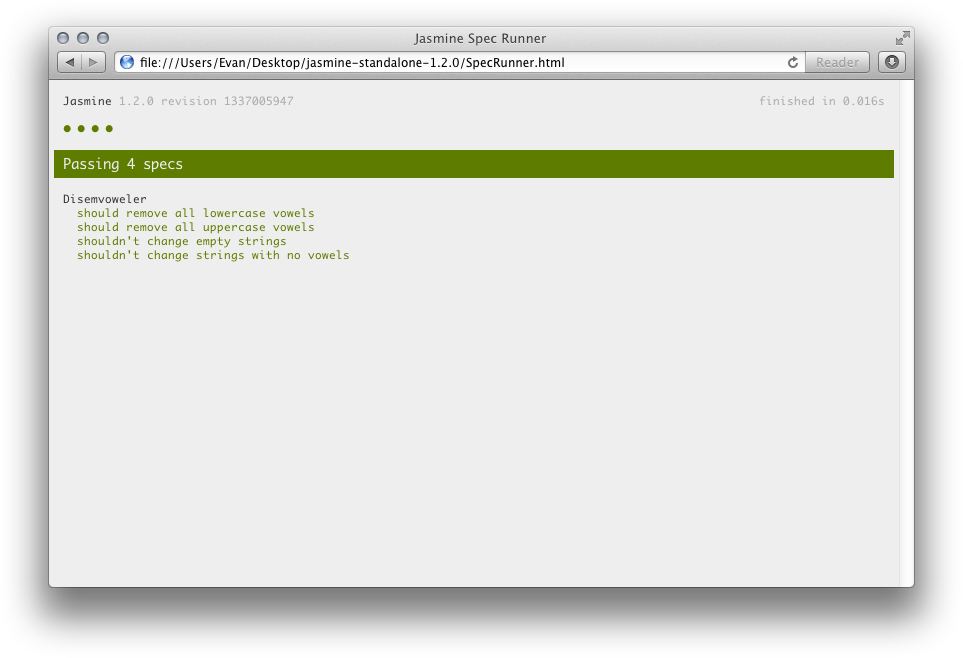

function disemvowel(str) {

return str.replace(/a|e|i|o|u/gi, "");

}Save that and rerun the spec runner. See Figure 2-5.

It looks like our disemvoweler works! That’s a simple example of how to write code using TDD: tests come first, implementation comes second.