Beijing • Cambridge • Farnham • Köln • Sebastopol • Tokyo

“A lot of people think JavaScript is simple and in many cases it is. But in its elegant simplicity lies a deeper functionality that if leveraged properly, can produce amazing results. Axel’s ability to distill this into an approachable reference will certainly help both aspiring and experienced developers achieve a better understanding of the language.”

—Rey Bango Advocate for cross-browser development, proponent of the open web, and lover of the JavaScript programming language

“Axel’s writing style is succinct, to the point, yet at the same time extremely detailed. The many code examples make even the most complex topics in the book easy to understand.”

—Mathias Bynens Belgian web standards enthusiast who likes HTML, CSS, JavaScript, Unicode, performance, and security

"Speaking JavaScript is a modern, up to date book perfectly aimed at the existing experienced programmer ready to take a deep dive into JavaScript. Without wasting time on laborious explanations, Dr. Rauschmayer quickly cuts to the core of JavaScript and its various concepts and gets developers up to speed quickly with a language that seems intent on taking over the developer world.”

—Peter Cooper Publisher, entrepreneur, and co-organizer of Fluent Conference

“If you have enjoyed Axel’s blog, then you’ll love this book. His book is filled with tons of bite-sized code snippets to aid in the learning process. If you want to dive deep and understand the ins and outs of JavaScript, then I highly recommend this book.”

—Elijah Manor Christian, family man, and front end web developer for Dave Ramsey; enjoys speaking, blogging, and tweeting

“This book opens the door into the modern JavaScript community with just enough background and plenty of in-depth introduction to make it seem like you’ve been with the community from the start.”

—Mitch Pronschinske DZone Editor

“After following Dr. Axel Rauschmayer’s work for a few years, I was delighted to learn that he was writing a book to share his deep expertise of JavaScript with those getting started with the language. I’ve read many JavaScript books, but none that show the attention to detail and comprehensiveness of Speaking JS, without being boring or overwhelming. I’ll be recommending this book for years to come.”

—Guillermo Rauch Speaker, creator of socket.io, mongoose, early Node.js contributor, author of “Smashing Node.js”, founder of LearnBoost/Cloudup (acq. by Wordpress in 2013), and Open Academy mentor

Due to its prevalence on the Web and other factors, JavaScript has become hard to avoid. That doesn’t mean that it is well liked, though. With this book, I’m hoping to convince you that, while you do have to accept a fair amount of quirks when using it, JavaScript is a decent language that makes you very productive and can be fun to program in.

Even though I have followed its development since its birth, it took me a long time to warm up to JavaScript. However, when I finally did, it turned out that my prior experience had already prepared me well, because I had worked with Scheme, Java (including GWT), Python, Perl, and Self (all of which have influenced JavaScript).

In 2010, I became aware of Node.js, which gave me hope that I’d eventually be able to use JavaScript on both server and client. As a consequence, I switched to JavaScript as my primary programming language. While learning it, I started writing a book chronicling my discoveries. This is the book you are currently reading. On my blog, I published parts of the book and other material on JavaScript. That helped me in several ways: the positive reaction encouraged me to keep going and made writing this book less lonely; comments to blog posts gave me additional information and tips (as acknowledged everywhere in this book); and it made people aware of my work, which eventually led to O’Reilly publishing this book.

Therefore, this book has been over three years in the making. It has profited from this long gestation period, during which I continually refined its contents. I’m glad that the book is finally finished and hope that people will find it useful for learning JavaScript. O’Reilly has agreed to make it available to be read online, for free, which should help make it accessible to a broad audience.

Is this book for you? The following items can help you determine that:

This book has been written for programmers, by a programmer. So, in order to understand it, you should already know object-oriented programming, for example, via a mainstream programming language such as Java, PHP, C++, Python, Ruby, Objective-C, C#, or Perl.

Thus, the book’s target audience is programmers who want to learn JavaScript quickly and properly, and JavaScript programmers who want to deepen their skills and/or look up specific topics.

This book is divided into four parts, but the main two are:

These parts are completely independent! You can treat them as if they were separate books: the former is more like a guide, the latter is more like a reference. The Four Parts of This Book tells you more about the structure of this book.

The most important tip for learning JavaScript is don’t get bogged down by the details. Yes, there are many details when it comes to the language, and this book covers most of them. But there is also a relatively simple and elegant “big picture” that I will point out to you.

This book is organized into four parts:

While reading this book, you may want to have a command line ready. That allows you to try out code interactively. The most popular choices are:

node.

The following notational conventions are used throughout the book.

Question marks (?) are used to mark optional parameters. For example:

parseInt(str,radix?)

French quotation marks (guillemets) denote metacode. You can think of such metacode as blanks, to be filled in by actual code. For example:

try{«try_statements»}

“White” square brackets mark optional syntactic elements. For example:

break⟦«label»⟧

In JavaScript comments, I sometimes use backticks to distinguish JavaScript from English:

foo(x,y);// calling function `foo` with parameters `x` and `y`

I refer to built-in methods via their full path:

«Constructor».prototype.«methodName»()

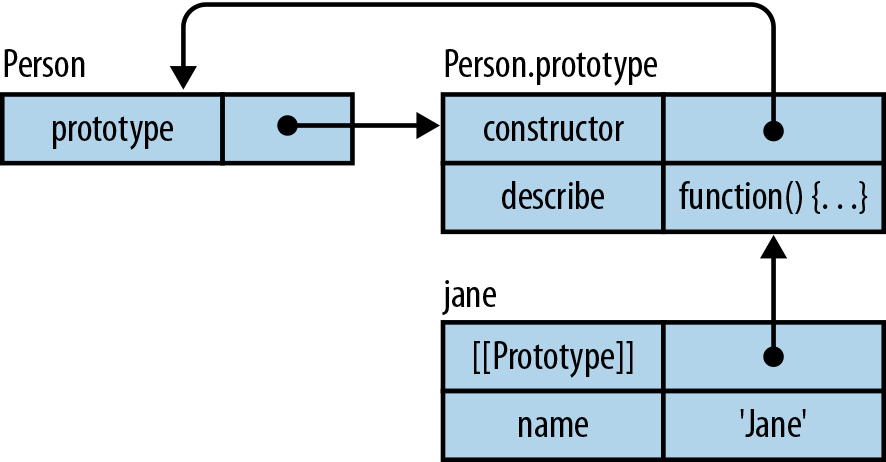

For example, Array.prototype.join() refers to the array method join(); that is, JavaScript stores the methods of Array instances in the object Array.prototype. The reason for this is explained in Layer 3: Constructors—Factories for Instances.

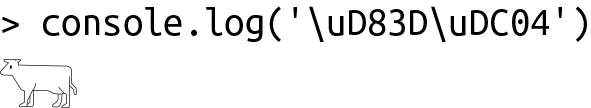

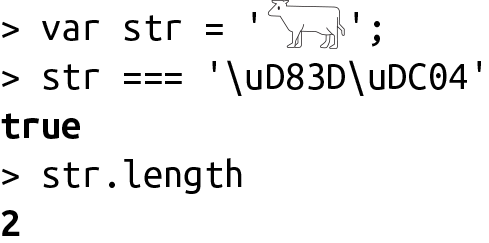

Whenever I introduce a new concept, I often illustrate it via an interaction in a JavaScript command line. This looks as follows:

> 3 + 4 7

The text after the greater-than character is the input, typed by a human. Everything else is output by the JavaScript engine. Additionally, I use the method console.log() to print data to the console, especially in (non–command-line) source code:

varx=3;x++;console.log(x);// 4

This element signifies a tip or suggestion.

This element signifies a general note.

This element indicates a warning or caution.

While you can obviously use this book as a reference, sometimes looking up information online is quicker. One resource I recommend is the Mozilla Developer Network (MDN). You can search the Web to find documentation on MDN. For example, the following web search finds the documentation for the push() method of arrays:

mdn array push

Safari Books Online is an on-demand digital library that delivers expert content in both book and video form from the world’s leading authors in technology and business.

Technology professionals, software developers, web designers, and business and creative professionals use Safari Books Online as their primary resource for research, problem solving, learning, and certification training.

Safari Books Online offers a range of product mixes and pricing programs for organizations, government agencies, and individuals. Subscribers have access to thousands of books, training videos, and prepublication manuscripts in one fully searchable database from publishers like O’Reilly Media, Prentice Hall Professional, Addison-Wesley Professional, Microsoft Press, Sams, Que, Peachpit Press, Focal Press, Cisco Press, John Wiley & Sons, Syngress, Morgan Kaufmann, IBM Redbooks, Packt, Adobe Press, FT Press, Apress, Manning, New Riders, McGraw-Hill, Jones & Bartlett, Course Technology, and dozens more. For more information about Safari Books Online, please visit us online.

Please address comments and questions concerning this book to the publisher:

| O’Reilly Media, Inc. |

| 1005 Gravenstein Highway North |

| Sebastopol, CA 95472 |

| 800-998-9938 (in the United States or Canada) |

| 707-829-0515 (international or local) |

| 707-829-0104 (fax) |

We have a web page for this book, where we list errata, examples, and any additional information. You can access this page at http://oreil.ly/speaking-js.

To comment or ask technical questions about this book, send email to bookquestions@oreilly.com.

For more information about our books, courses, conferences, and news, see our website at http://www.oreilly.com.

Find us on Facebook: http://facebook.com/oreilly

Follow us on Twitter: http://twitter.com/oreillymedia

Watch us on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/oreillymedia

I would like to thank the following people, all of whom helped make this book possible.

The following people laid the foundations for my understanding of JavaScript (in chronological order):

More sources are acknowledged in the chapters.

I am much obliged to the following people who reviewed this book. They provided important feedback and corrections. In alphabetical order:

This part is a self-contained quick introduction to JavaScript. You can understand it without reading anything else in this book, and no other part of the book depends on its contents. However, the tips for how to read this book in Tips for Reading This Book do apply.

This chapter is about “Basic JavaScript,” a name I chose for a subset of JavaScript that is as concise as possible while still enabling you to be productive. When you are starting to learn JavaScript, I recommend that you program in it for a while before moving on to the rest of the language. That way, you don’t have to learn everything at once, which can be confusing.

This section gives a little background on JavaScript to help you understand why it is the way it is.

ECMAScript is the official name for JavaScript. A new name became necessary because there is a trademark on Java (held originally by Sun, now by Oracle). At the moment, Mozilla is one of the few companies allowed to officially use the name JavaScript because it received a license long ago. For common usage, the following rules apply:

JavaScript’s creator, Brendan Eich, had no choice but to create the language very quickly (or other, worse technologies would have been adopted by Netscape). He borrowed from several programming languages: Java (syntax, primitive values versus objects), Scheme and AWK (first-class functions), Self (prototypal inheritance), and Perl and Python (strings, arrays, and regular expressions).

JavaScript did not have exception handling until ECMAScript 3, which explains why the language so often automatically converts values and so often fails silently: it initially couldn’t throw exceptions.

On one hand, JavaScript has quirks and is missing quite a bit of functionality (block-scoped variables, modules, support for subclassing, etc.). On the other hand, it has several powerful features that allow you to work around these problems. In other languages, you learn language features. In JavaScript, you often learn patterns instead.

Given its influences, it is no surprise that JavaScript enables a programming style that is a mixture of functional programming (higher-order functions; built-in map, reduce, etc.) and object-oriented programming (objects, inheritance).

This section explains basic syntactic principles of JavaScript.

// Two slashes start single-line commentsvarx;// declaring a variablex=3+y;// assigning a value to the variable `x`foo(x,y);// calling function `foo` with parameters `x` and `y`obj.bar(3);// calling method `bar` of object `obj`// A conditional statementif(x===0){// Is `x` equal to zero?x=123;}// Defining function `baz` with parameters `a` and `b`functionbaz(a,b){returna+b;}

Note the two different uses of the equals sign:

=) is used to assign a value to a variable.

===) is used to compare two values (see Equality Operators).

To understand JavaScript’s syntax, you should know that it has two major syntactic categories: statements and expressions:

Statements “do things.” A program is a sequence of statements. Here is an example of a statement, which declares (creates) a variable foo:

varfoo;

Expressions produce values. They are function arguments, the right side of an assignment, etc. Here’s an example of an expression:

3*7

The distinction between statements and expressions is best illustrated by the fact that JavaScript has two different ways to do if-then-else—either as a statement:

varx;if(y>=0){x=y;}else{x=-y;}

or as an expression:

varx=y>=0?y:-y;

You can use the latter as a function argument (but not the former):

myFunction(y>=0?y:-y)

Finally, wherever JavaScript expects a statement, you can also use an expression; for example:

foo(7,1);

The whole line is a statement (a so-called expression statement), but the function call foo(7, 1) is an expression.

Semicolons are optional in JavaScript. However, I recommend always including them, because otherwise JavaScript can guess wrong about the end of a statement. The details are explained in Automatic Semicolon Insertion.

Semicolons terminate statements, but not blocks. There is one case where you will see a semicolon after a block: a function expression is an expression that ends with a block. If such an expression comes last in a statement, it is followed by a semicolon:

// Pattern: var _ = ___;varx=3*7;varf=function(){};// function expr. inside var decl.

Variables in JavaScript are declared before they are used:

varfoo;// declare variable `foo`

You can declare a variable and assign a value at the same time:

varfoo=6;

You can also assign a value to an existing variable:

foo=4;// change variable `foo`

There are compound assignment operators such as +=. The following two

assignments are equivalent:

x+=1;x=x+1;

Identifiers are names that play various syntactic roles in JavaScript. For example, the name of a variable is an identifier. Identifiers are case sensitive.

Roughly, the first character of an identifier can be any Unicode letter, a dollar sign ($), or an underscore (_). Subsequent characters can additionally be any Unicode digit. Thus, the following are all legal identifiers:

arg0_tmp$elemπ

The following identifiers are reserved words—they are part of the syntax and can’t be used as variable names (including function names and parameter names):

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The following three identifiers are not reserved words, but you should treat them as if they were:

|

|

|

Lastly, you should also stay away from the names of standard global variables (see Chapter 23). You can use them for local variables without breaking anything, but your code still becomes confusing.

JavaScript has many values that we have come to expect from programming languages: booleans, numbers, strings, arrays, and so on. All values in JavaScript have properties. Each property has a key (or name) and a value. You can think of properties like fields of a record. You use the dot (.) operator to read a property:

value.propKey

For example, the string 'abc' has the property length:

> var str = 'abc'; > str.length 3

The preceding can also be written as:

> 'abc'.length 3

The dot operator is also used to assign a value to a property:

> var obj = {}; // empty object

> obj.foo = 123; // create property `foo`, set it to 123

123

> obj.foo

123And you can use it to invoke methods:

> 'hello'.toUpperCase() 'HELLO'

In the preceding example, we have invoked the method toUpperCase() on the value

'hello'.

JavaScript makes a somewhat arbitrary distinction between values:

null, and undefined.

A major difference between the two is how they are compared; each object has a unique identity and is only (strictly) equal to itself:

> var obj1 = {}; // an empty object

> var obj2 = {}; // another empty object

> obj1 === obj2

false

> obj1 === obj1

trueIn contrast, all primitive values encoding the same value are considered the same:

> var prim1 = 123; > var prim2 = 123; > prim1 === prim2 true

The next two sections explain primitive values and objects in more detail.

The following are all of the primitive values (or primitives for short):

true, false (see Booleans)

1736, 1.351 (see Numbers)

'abc', "abc" (see Strings)

undefined, null (see undefined and null)

Primitives have the following characteristics:

The “content” is compared:

> 3 === 3 true > 'abc' === 'abc' true

Properties can’t be changed, added, or removed:

> var str = 'abc'; > str.length = 1; // try to change property `length` > str.length // ⇒ no effect 3 > str.foo = 3; // try to create property `foo` > str.foo // ⇒ no effect, unknown property undefined

(Reading an unknown property always returns undefined.)

All nonprimitive values are objects. The most common kinds of objects are:

Plain objects, which can be created by object literals (see Single Objects):

{firstName:'Jane',lastName:'Doe'}

The preceding object has two properties: the value of property firstName

is 'Jane' and the value of property lastName is 'Doe'.

Arrays, which can be created by array literals (see Arrays):

['apple','banana','cherry']

The preceding array has three elements that can be accessed via numeric

indices. For example, the index of 'apple' is 0.

Regular expressions, which can be created by regular expression literals (see Regular Expressions):

/^a+b+$/Objects have the following characteristics:

Identities are compared; every value has its own identity:

> {} === {} // two different empty objects

false

> var obj1 = {};

> var obj2 = obj1;

> obj1 === obj2

trueYou can normally freely change, add, and remove properties (see Single Objects):

> var obj = {};

> obj.foo = 123; // add property `foo`

> obj.foo

123Most programming languages have values denoting missing information. JavaScript has two such “nonvalues,” undefined and null:

undefined means “no value.” Uninitialized variables are undefined:

> var foo; > foo undefined

Missing parameters are undefined:

> function f(x) { return x }

> f()

undefinedIf you read a nonexistent property, you get undefined:

> var obj = {}; // empty object

> obj.foo

undefinednull means “no object.” It is used as a nonvalue whenever an object is expected (parameters, last in a chain of objects, etc.).

undefined and null have no properties, not even standard methods such as toString().

Functions normally allow you to indicate a missing value via either undefined or null. You can do the same via an explicit check:

if(x===undefined||x===null){...}

You can also exploit the fact that both undefined and null are considered false:

if(!x){...}

false, 0, NaN, and '' are also considered false (see Truthy and Falsy).

There are two operators for categorizing values: typeof is mainly used for primitive values, while instanceof is used for objects.

typeof looks like this:

typeofvalue

It returns a string describing the “type” of value. Here are some examples:

> typeof true

'boolean'

> typeof 'abc'

'string'

> typeof {} // empty object literal

'object'

> typeof [] // empty array literal

'object'The following table lists all results of typeof:

| Operand | Result |

|

|

|

|

Boolean value |

|

Number value |

|

String value |

|

Function |

|

All other normal values |

|

(Engine-created value) | JavaScript engines are allowed to create values for which |

typeof null returning 'object' is a bug that can’t be fixed, because it would break existing code. It does not mean that null is an object.

instanceof looks like this:

valueinstanceofConstr

It returns true if value is an object that has been created by the

constructor Constr (see Constructors: Factories for Objects). Here are some examples:

> var b = new Bar(); // object created by constructor Bar

> b instanceof Bar

true

> {} instanceof Object

true

> [] instanceof Array

true

> [] instanceof Object // Array is a subconstructor of Object

true

> undefined instanceof Object

false

> null instanceof Object

falseThe primitive boolean type comprises the values true and false. The following operators produce booleans:

&& (And), || (Or)

! (Not)

Comparison operators:

===, !==, ==, !=

>, >=, <, <=

Whenever JavaScript expects a boolean value (e.g., for the condition of an if statement), any value can be used. It will be interpreted as either true or false. The following values are interpreted as false:

undefined, null

false

-0, NaN

''

All other values (including all objects!) are considered true. Values interpreted as false are called falsy, and values interpreted as true are called truthy. Boolean(), called as a function, converts its parameter to a boolean. You can use it to test how a value is interpreted:

> Boolean(undefined)

false

> Boolean(0)

false

> Boolean(3)

true

> Boolean({}) // empty object

true

> Boolean([]) // empty array

trueBinary logical operators in JavaScript are short-circuiting. That is, if the first operand suffices for determining the result, the second operand is not evaluated. For example, in the following expressions, the function foo() is never called:

false&&foo()true||foo()

Furthermore, binary logical operators return either one of their operands—which may or may not be a boolean. A check for truthiness is used to determine which one:

JavaScript has two kinds of equality:

== and !=

=== and !==

Normal equality considers (too) many values to be equal (the details are explained in Normal (Lenient) Equality (==, !=)), which can hide bugs. Therefore, always using strict equality is recommended.

All numbers in JavaScript are floating-point:

> 1 === 1.0 true

Special numbers include the following:

NaN (“not a number”)

An error value:

> Number('xyz') // 'xyz' can’t be converted to a number

NaNInfinity

> 3 / 0 Infinity > Math.pow(2, 1024) // number too large Infinity

Infinity is larger than any other number (except NaN). Similarly, -Infinity is smaller than any other number (except NaN). That makes these numbers useful as default values (e.g., when you are looking for a minimum or a maximum).

JavaScript has the following arithmetic operators (see Arithmetic Operators):

number1 + number2

number1 - number2

number1 * number2

number1 / number2

number1 % number2

++variable, variable++

--variable, variable--

-value

+value

The global object Math (see Math) provides more arithmetic operations, via functions.

JavaScript also has operators for bitwise operations (e.g., bitwise And; see Bitwise Operators).

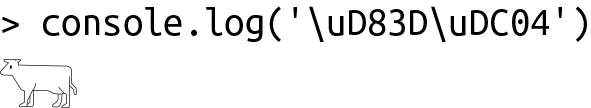

Strings can be created directly via string literals. Those literals are delimited by single or double quotes. The backslash (\) escapes characters and produces a few control characters. Here are some examples:

'abc'"abc"'Did she say "Hello"?'"Did she say \"Hello\"?"'That\'s nice!'"That's nice!"'Line 1\nLine 2'// newline'Backlash: \\'

Single characters are accessed via square brackets:

> var str = 'abc'; > str[1] 'b'

The property length counts the number of characters in the string:

> 'abc'.length 3

Like all primitives, strings are immutable; you need to create a new string if you want to change an existing one.

Strings are concatenated via the plus (+) operator, which converts the other operand to a string if one of the operands is a string:

> var messageCount = 3; > 'You have ' + messageCount + ' messages' 'You have 3 messages'

To concatenate strings in multiple steps, use the += operator:

> var str = ''; > str += 'Multiple '; > str += 'pieces '; > str += 'are concatenated.'; > str 'Multiple pieces are concatenated.'

Strings have many useful methods (see String Prototype Methods). Here are some examples:

> 'abc'.slice(1) // copy a substring

'bc'

> 'abc'.slice(1, 2)

'b'

> '\t xyz '.trim() // trim whitespace

'xyz'

> 'mjölnir'.toUpperCase()

'MJÖLNIR'

> 'abc'.indexOf('b') // find a string

1

> 'abc'.indexOf('x')

-1Conditionals and loops in JavaScript are introduced in the following sections.

The if statement has a then clause and an optional else clause that are executed depending on a boolean condition:

if(myvar===0){// then}if(myvar===0){// then}else{// else}if(myvar===0){// then}elseif(myvar===1){// else-if}elseif(myvar===2){// else-if}else{// else}

I recommend always using braces (they denote blocks of zero or more statements). But you don’t have to do so if a clause is only a single statement (the same holds for the control flow statements for and while):

if(x<0)return-x;

The following is a switch statement. The value of fruit decides which

case is executed:

switch(fruit){case'banana':// ...break;case'apple':// ...break;default:// all other cases// ...}

The “operand” after case can be any expression; it is compared via === with the parameter of switch.

The for loop has the following format:

for(⟦«init»⟧;⟦«condition»⟧;⟦«post_iteration»⟧)«statement»

init is executed at the beginning of the loop. condition is checked before each loop iteration; if it becomes false, then the loop is terminated. post_iteration is executed after each loop iteration.

This example prints all elements of the array arr on the console:

for(vari=0;i<arr.length;i++){console.log(arr[i]);}

The while loop continues looping over its body while its condition holds:

// Same as for loop above:vari=0;while(i<arr.length){console.log(arr[i]);i++;}

The do-while loop continues looping over its body while its condition holds. As the condition follows the body, the body is always executed at least once:

do{// ...}while(condition);

break leaves the loop.

continue starts a new loop iteration.

One way of defining a function is via a function declaration:

functionadd(param1,param2){returnparam1+param2;}

The preceding code defines a function, add, that has two parameters, param1 and param2, and returns the sum of both parameters. This is how you call that function:

> add(6, 1)

7

> add('a', 'b')

'ab'Another way of defining add() is by assigning a function expression to a variable add:

varadd=function(param1,param2){returnparam1+param2;};

A function expression produces a value and can thus be used to directly pass functions as arguments to other functions:

someOtherFunction(function(p1,p2){...});

Function declarations are hoisted—moved in their entirety to the beginning of the current scope. That allows you to refer to functions that are declared later:

functionfoo(){bar();// OK, bar is hoistedfunctionbar(){...}}

Note that while var declarations are also hoisted (see Variables Are Hoisted), assignments performed by them are not:

functionfoo(){bar();// Not OK, bar is still undefinedvarbar=function(){// ...};}

You can call any function in JavaScript with an arbitrary amount of arguments; the language will never complain. It will, however, make all parameters available via the special variable arguments. arguments looks like an array, but has none of the array methods:

> function f() { return arguments }

> var args = f('a', 'b', 'c');

> args.length

3

> args[0] // read element at index 0

'a'Let’s use the following function to explore how too many or too few

parameters are handled in JavaScript (the function toArray() is shown in Converting arguments to an Array):

functionf(x,y){console.log(x,y);returntoArray(arguments);}

Additional parameters will be ignored (except by arguments):

> f('a', 'b', 'c')

a b

[ 'a', 'b', 'c' ]Missing parameters will get the value undefined:

> f('a')

a undefined

[ 'a' ]

> f()

undefined undefined

[]The following is a common pattern for assigning default values to parameters:

functionpair(x,y){x=x||0;// (1)y=y||0;return[x,y];}

In line (1), the || operator returns x if it is truthy (not null, undefined, etc.). Otherwise, it returns the second operand:

> pair() [ 0, 0 ] > pair(3) [ 3, 0 ] > pair(3, 5) [ 3, 5 ]

If you want to enforce an arity (a specific number of parameters), you can check arguments.length:

functionpair(x,y){if(arguments.length!==2){thrownewError('Need exactly 2 arguments');}...}

arguments is not an array, it is only array-like (see Array-Like Objects and Generic Methods). It has a property length, and you can access its elements via indices in square brackets. You cannot, however, remove elements or invoke any of the array methods on it. Thus, you sometimes need to convert arguments to an array, which is what the following function does (it is explained in Array-Like Objects and Generic Methods):

functiontoArray(arrayLikeObject){returnArray.prototype.slice.call(arrayLikeObject);}

The most common way to handle exceptions (see Chapter 14) is as follows:

functiongetPerson(id){if(id<0){thrownewError('ID must not be negative: '+id);}return{id:id};// normally: retrieved from database}functiongetPersons(ids){varresult=[];ids.forEach(function(id){try{varperson=getPerson(id);result.push(person);}catch(exception){console.log(exception);}});returnresult;}

The try clause surrounds critical code, and the catch clause is executed if an exception is thrown inside the try clause. Using the preceding code:

> getPersons([2, -5, 137])

[Error: ID must not be negative: -5]

[ { id: 2 }, { id: 137 } ]Strict mode (see Strict Mode) enables more warnings and makes JavaScript a cleaner language (nonstrict mode is sometimes called “sloppy mode”). To switch it on, type the following line first in a JavaScript file or a <script> tag:

'use strict';

You can also enable strict mode per function:

functionfunctionInStrictMode(){'use strict';}

In JavaScript, you declare variables via var before using them:

> var x; > x = 3; > y = 4; ReferenceError: y is not defined

You can declare and initialize several variables with a single var

statement:

varx=1,y=2,z=3;

But I recommend using one statement per variable (the reason is explained in Syntax). Thus, I would rewrite the previous statement to:

varx=1;vary=2;varz=3;

Because of hoisting (see Variables Are Hoisted), it is usually best to declare variables at the beginning of a function.

The scope of a variable is always the complete function (as opposed to the current block). For example:

functionfoo(){varx=-512;if(x<0){// (1)vartmp=-x;...}console.log(tmp);// 512}

We can see that the variable tmp is not restricted to the block

starting in line (1); it exists until the end of the function.

Each variable declaration is hoisted: the declaration is moved to the beginning of the function, but assignments that it makes stay put. As an example, consider the variable declaration in line (1) in the following function:

functionfoo(){console.log(tmp);// undefinedif(false){vartmp=3;// (1)}}

Internally, the preceding function is executed like this:

functionfoo(){vartmp;// hoisted declarationconsole.log(tmp);if(false){tmp=3;// assignment stays put}}

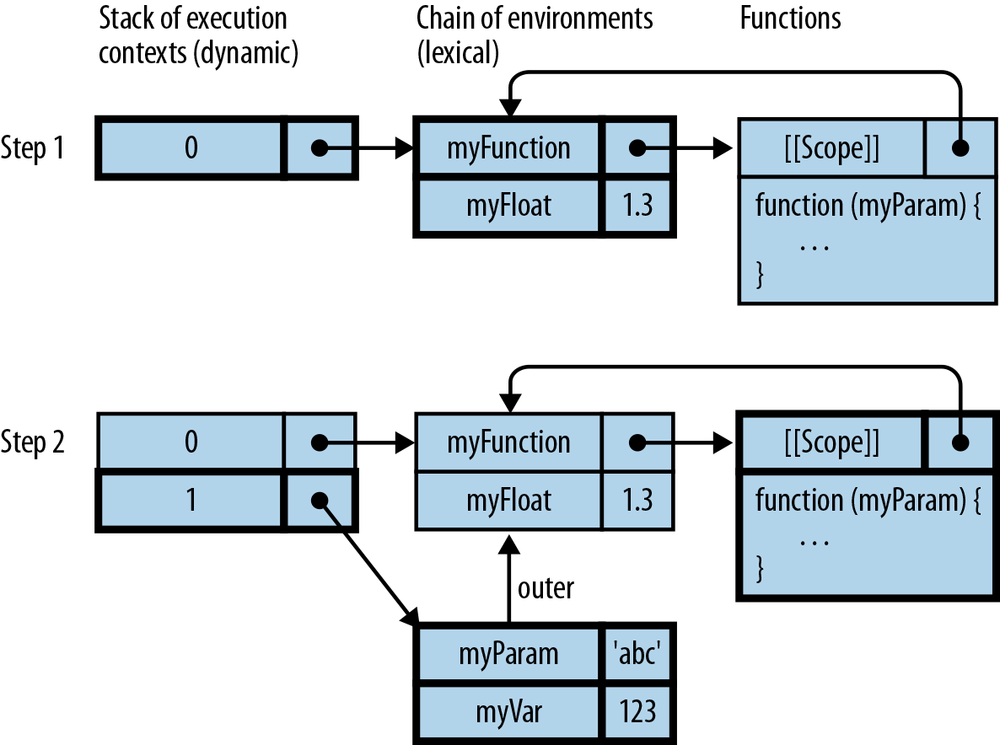

Each function stays connected to the variables of the functions that surround it, even after it leaves the scope in which it was created. For example:

functioncreateIncrementor(start){returnfunction(){// (1)start++;returnstart;}}

The function starting in line (1) leaves the context in which it was created, but stays connected to a live version of start:

> var inc = createIncrementor(5); > inc() 6 > inc() 7 > inc() 8

A closure is a function plus the connection to the variables of its

surrounding scopes. Thus, what createIncrementor() returns is a

closure.

Sometimes you want to introduce a new variable scope—for example, to prevent a variable from becoming global. In JavaScript, you can’t use a block to do so; you must use a function. But there is a pattern for using a function in a block-like manner. It is called IIFE (immediately invoked function expression, pronounced “iffy”):

(function(){// open IIFEvartmp=...;// not a global variable}());// close IIFE

Be sure to type the preceding example exactly as shown (apart from the comments). An IIFE is a function expression that is called immediately after you define it. Inside the function, a new scope exists, preventing tmp from becoming global. Consult Introducing a New Scope via an IIFE for details on IIFEs.

Closures keep their connections to outer variables, which is sometimes not what you want:

varresult=[];for(vari=0;i<5;i++){result.push(function(){returni});// (1)}console.log(result[1]());// 5 (not 1)console.log(result[3]());// 5 (not 3)

The value returned in line (1) is always the current value of i, not the value it had when the function was created. After the loop is finished, i has the value 5, which is why all functions in the array return that value. If you want the function in line (1) to receive a snapshot of the current value of i, you can use an IIFE:

for(vari=0;i<5;i++){(function(){vari2=i;// copy current iresult.push(function(){returni2});}());}

This section covers two basic object-oriented mechanisms of JavaScript: single objects and constructors (which are factories for objects, similar to classes in other languages).

Like all values, objects have properties. You could, in fact, consider an object to be a set of properties, where each property is a (key, value) pair. The key is a string, and the value is any JavaScript value.

In JavaScript, you can directly create plain objects, via object literals:

'use strict';varjane={name:'Jane',describe:function(){return'Person named '+this.name;}};

The preceding object has the properties name and describe. You can read (“get”) and write (“set”) properties:

> jane.name // get 'Jane' > jane.name = 'John'; // set > jane.newProperty = 'abc'; // property created automatically

Function-valued properties such as describe are called methods. They use this to refer to the object that was used to call them:

> jane.describe() // call method 'Person named John' > jane.name = 'Jane'; > jane.describe() 'Person named Jane'

The in operator checks whether a property exists:

> 'newProperty' in jane true > 'foo' in jane false

If you read a property that does not exist, you get the value undefined. Hence, the previous two checks could also be performed like this:

> jane.newProperty !== undefined true > jane.foo !== undefined false

The delete operator removes a property:

> delete jane.newProperty true > 'newProperty' in jane false

A property key can be any string. So far, we have seen property keys in object literals and after the dot operator. However, you can use them that way only if they are identifiers (see Identifiers and Variable Names). If you want to use other strings as keys, you have to quote them in an object literal and use square brackets to get and set the property:

> var obj = { 'not an identifier': 123 };

> obj['not an identifier']

123

> obj['not an identifier'] = 456;Square brackets also allow you to compute the key of a property:

> var obj = { hello: 'world' };

> var x = 'hello';

> obj[x]

'world'

> obj['hel'+'lo']

'world'If you extract a method, it loses its connection with the object. On its own, the function is not a method anymore, and this has the value undefined (in strict mode).

As an example, let’s go back to the earlier object jane:

'use strict';varjane={name:'Jane',describe:function(){return'Person named '+this.name;}};

We want to extract the method describe from jane, put it into a variable func, and call it. However, that doesn’t work:

> var func = jane.describe; > func() TypeError: Cannot read property 'name' of undefined

The solution is to use the method bind() that all functions have. It creates a new function whose this always has the given value:

> var func2 = jane.describe.bind(jane); > func2() 'Person named Jane'

Every function has its own special variable this. This is inconvenient if you nest a function inside a method, because you can’t access the method’s this from the function. The following is an example where we call forEach with a function to iterate over an array:

varjane={name:'Jane',friends:['Tarzan','Cheeta'],logHiToFriends:function(){'use strict';this.friends.forEach(function(friend){// `this` is undefined hereconsole.log(this.name+' says hi to '+friend);});}}

Calling logHiToFriends produces an error:

> jane.logHiToFriends() TypeError: Cannot read property 'name' of undefined

Let’s look at two ways of fixing this. First, we could store this in a

different variable:

logHiToFriends:function(){'use strict';varthat=this;this.friends.forEach(function(friend){console.log(that.name+' says hi to '+friend);});}

Or, forEach has a second parameter that allows you to provide a

value for this:

logHiToFriends:function(){'use strict';this.friends.forEach(function(friend){console.log(this.name+' says hi to '+friend);},this);}

Function expressions are often used as arguments in function calls in JavaScript. Always be careful when you refer to this from one of those function expressions.

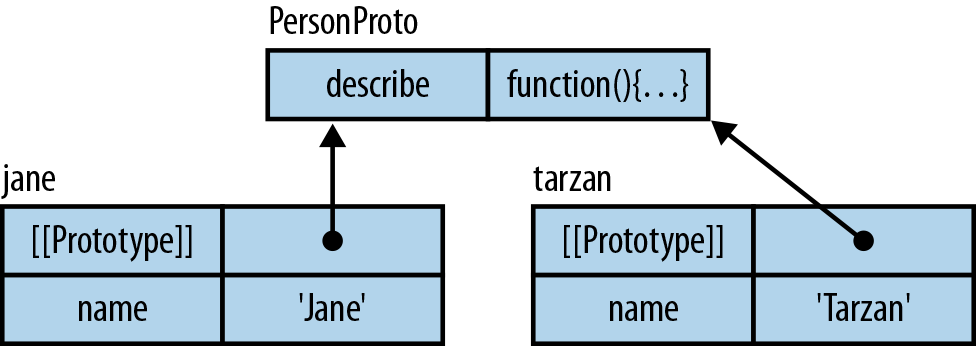

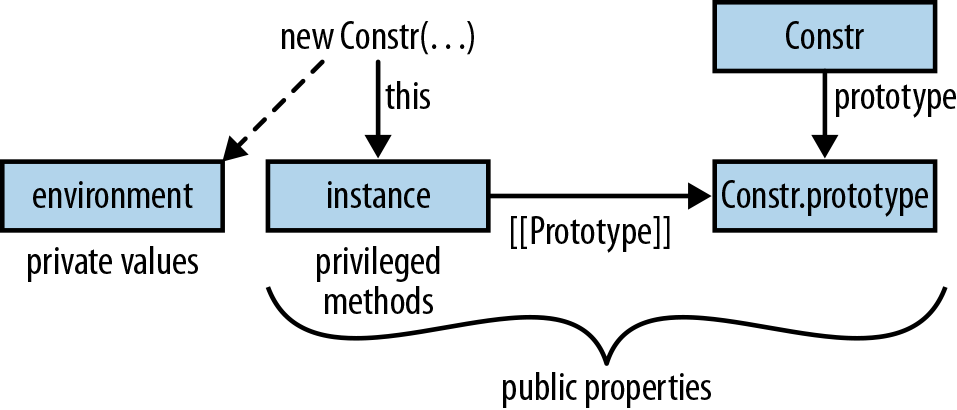

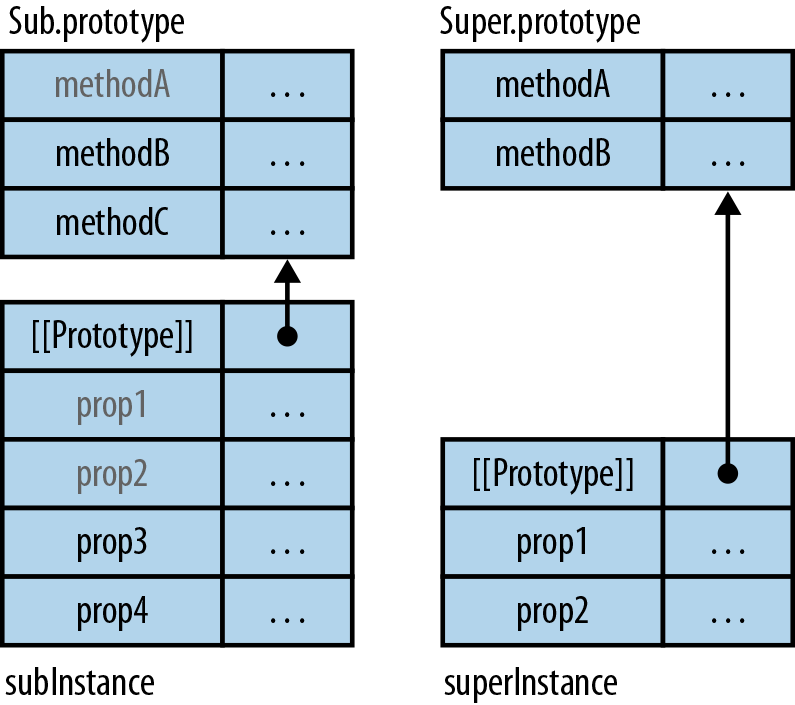

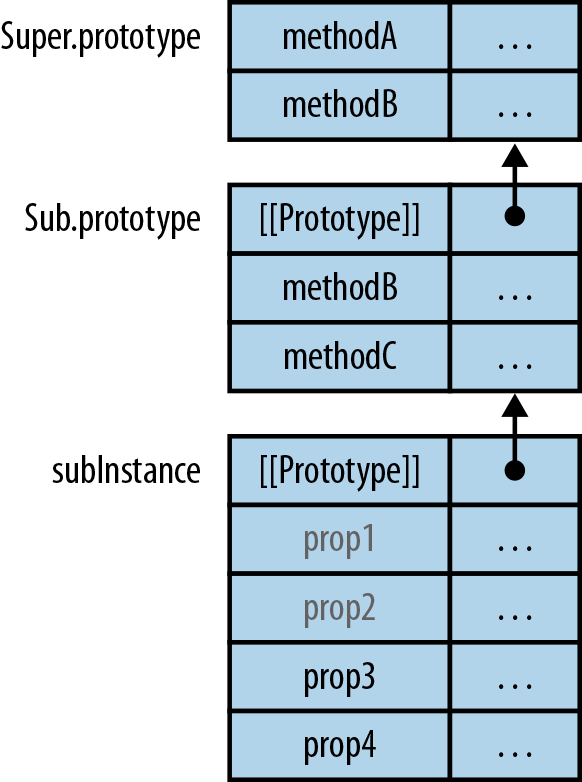

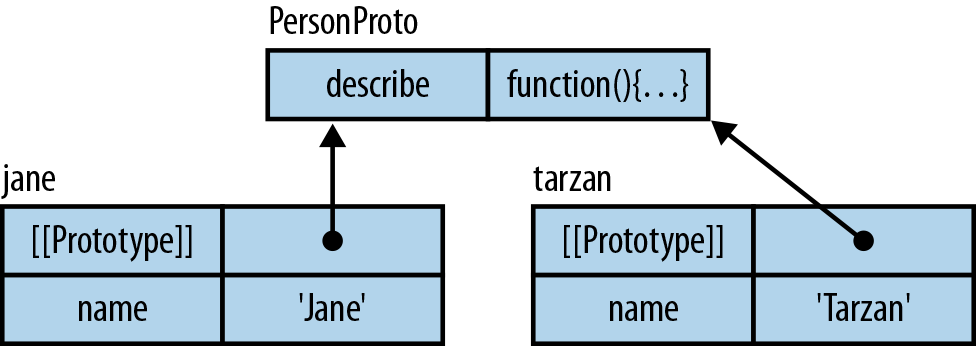

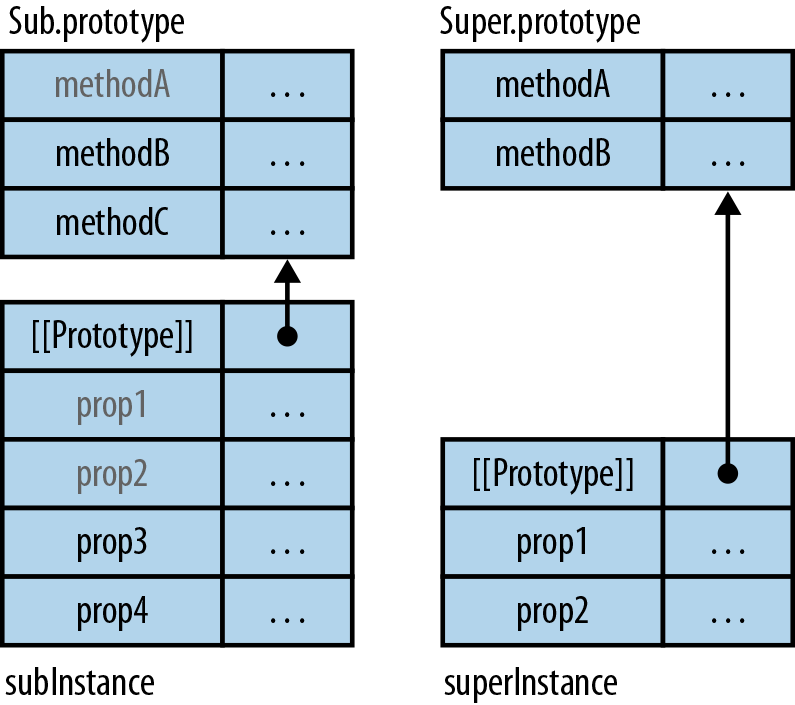

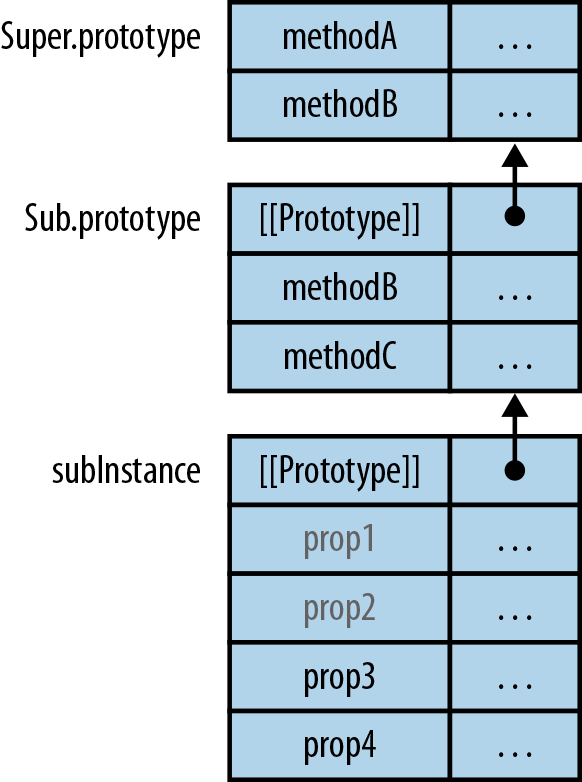

Until now, you may think that JavaScript objects are only maps from strings to values, a notion suggested by JavaScript’s object literals, which look like the map/dictionary literals of other languages. However, JavaScript objects also support a feature that is truly object-oriented: inheritance. This section does not fully explain how JavaScript inheritance works, but it shows you a simple pattern to get you started. Consult Chapter 17 if you want to know more.

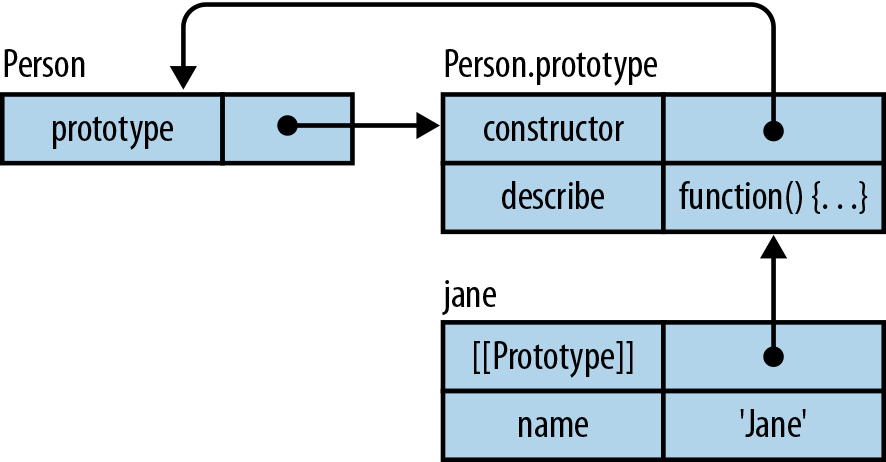

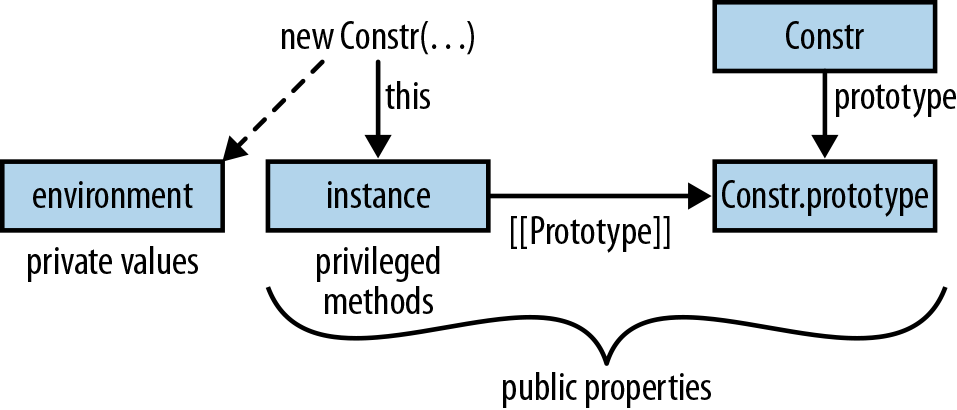

In addition to being “real” functions and methods, functions play another role in JavaScript: they become constructors—factories for objects—if invoked via the new operator. Constructors are thus a rough analog to classes in other languages. By convention, the names of constructors start with capital letters. For example:

// Set up instance datafunctionPoint(x,y){this.x=x;this.y=y;}// MethodsPoint.prototype.dist=function(){returnMath.sqrt(this.x*this.x+this.y*this.y);};

We can see that a constructor has two parts. First, the function Point sets up the instance data. Second, the property Point.prototype contains an object with the methods. The former data is specific to each instance, while the latter data is shared among all instances.

To use Point, we invoke it via the new operator:

> var p = new Point(3, 5); > p.x 3 > p.dist() 5.830951894845301

p is an instance of Point:

> p instanceof Point true

Arrays are sequences of elements that can be accessed via integer indices starting at zero.

Array literals are handy for creating arrays:

> var arr = [ 'a', 'b', 'c' ];

The preceding array has three elements: the strings 'a', 'b', and 'c'. You can access them via integer indices:

> arr[0] 'a' > arr[0] = 'x'; > arr [ 'x', 'b', 'c' ]

The length property indicates how many elements an array has. You can use it to append elements and to remove elements:

> var arr = ['a', 'b']; > arr.length 2 > arr[arr.length] = 'c'; > arr [ 'a', 'b', 'c' ] > arr.length 3 > arr.length = 1; > arr [ 'a' ]

The in operator works for arrays, too:

> var arr = [ 'a', 'b', 'c' ]; > 1 in arr // is there an element at index 1? true > 5 in arr // is there an element at index 5? false

Note that arrays are objects and can thus have object properties:

> var arr = []; > arr.foo = 123; > arr.foo 123

Arrays have many methods (see Array Prototype Methods). Here are a few examples:

> var arr = [ 'a', 'b', 'c' ];

> arr.slice(1, 2) // copy elements

[ 'b' ]

> arr.slice(1)

[ 'b', 'c' ]

> arr.push('x') // append an element

4

> arr

[ 'a', 'b', 'c', 'x' ]

> arr.pop() // remove last element

'x'

> arr

[ 'a', 'b', 'c' ]

> arr.shift() // remove first element

'a'

> arr

[ 'b', 'c' ]

> arr.unshift('x') // prepend an element

3

> arr

[ 'x', 'b', 'c' ]

> arr.indexOf('b') // find the index of an element

1

> arr.indexOf('y')

-1

> arr.join('-') // all elements in a single string

'x-b-c'

> arr.join('')

'xbc'

> arr.join()

'x,b,c'There are several array methods for iterating over elements (see Iteration (Nondestructive)). The two most important ones are forEach and map.

forEach iterates over an array and hands the current element and its index to a function:

['a','b','c'].forEach(function(elem,index){// (1)console.log(index+'. '+elem);});

The preceding code produces the following output:

0. a 1. b 2. c

Note that the function in line (1) is free to ignore arguments. It could, for example, only have the parameter elem.

map creates a new array by applying a function to each element of an existing array:

> [1,2,3].map(function (x) { return x*x })

[ 1, 4, 9 ]JavaScript has built-in support for regular expressions (Chapter 19 refers to tutorials and explains in more detail how they work). They are delimited by slashes:

/^abc$//[A-Za-z0-9]+/

> /^a+b+$/.test('aaab')

true

> /^a+b+$/.test('aaa')

false> /a(b+)a/.exec('_abbba_aba_')

[ 'abbba', 'bbb' ]The returned array contains the complete match at index 0, the capture of the first group at index 1, and so on. There is a way (discussed in RegExp.prototype.exec: Capture Groups) to invoke this method repeatedly to get all matches.

> '<a> <bbb>'.replace(/<(.*?)>/g, '[$1]') '[a] [bbb]'

The first parameter of replace must be a regular expression with a /g flag; otherwise, only the first occurrence is replaced. There is also a way (as discussed in String.prototype.replace: Search and Replace) to use a function to compute the replacement.

Math (see Chapter 21) is an object with arithmetic functions. Here are some examples:

> Math.abs(-2) 2 > Math.pow(3, 2) // 3 to the power of 2 9 > Math.max(2, -1, 5) 5 > Math.round(1.9) 2 > Math.PI // pre-defined constant for π 3.141592653589793 > Math.cos(Math.PI) // compute the cosine for 180° -1

JavaScript’s standard library is relatively spartan, but there are more things you can use:

Date (Chapter 20)

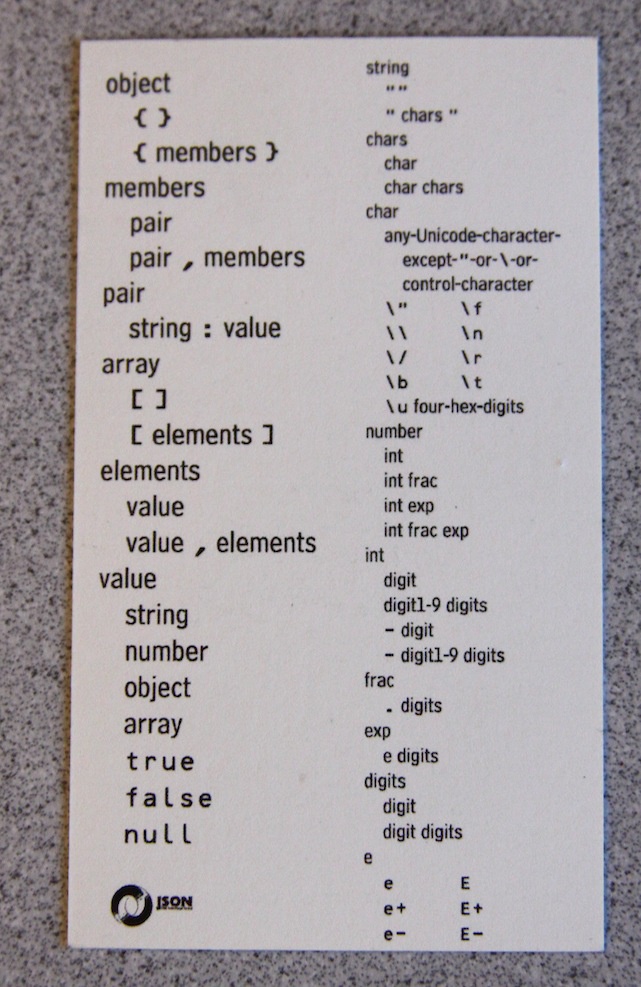

JSON (Chapter 22)

console.* methods (see The Console API)

This part explains the history and nature of JavaScript. It provides a broad first look at the language and explains the context in which it exists (without going too much into technical details).

This part is not required reading; you will be able to understand the rest of the book without having read it.

There are many programming languages out there. Why should you use JavaScript? This chapter looks at seven aspects that are important when you are choosing a programming language and argues that JavaScript does well overall:

JavaScript is arguably the most open programming language there is: ECMA-262, its specification, is an ISO standard. That specification is closely followed by many implementations from independent parties. Some of those implementations are open source. Furthermore, the evolution of the language is handled by TC39, a committee comprising several companies, including all major browser vendors. Many of those companies are normally competitors, but they work together for the benefit of the language.

Yes and no. I’ve written fair amounts of code in several programming languages from different paradigms. Therefore, I’m well aware that JavaScript isn’t the pinnacle of elegance. However, it is a very flexible language, has a reasonably elegant core, and enables you to use a mixture of object-oriented programming and functional programming.

Language compatibility between JavaScript engines used to be a problem, but isn’t anymore, partly thanks to the test262 suite that checks engines for conformance to the ECMAScript specification. In contrast, browser and DOM differences are still a challenge. That’s why it is normally best to rely on frameworks for hiding those differences.

The most beautiful programming language in the world is useless unless it allows you to write the program that you need.

In the area of graphical user interfaces, JavaScript benefits from being part of HTML5. In this section, I use the term HTML5 for “the browser platform” (HTML, CSS, and browser JavaScript APIs). HTML5 is deployed widely and making constant progress. It is slowly becoming a complete layer for writing full-featured, cross-platform applications; similar to, say, the Java platform, it’s almost like an embedded operating system. One of HTML5’s selling points is that it lets you write cross-platform graphical user interfaces. Those are always a compromise: you give up some quality in exchange for not being limited to a single operating system. In the past, “cross-platform” meant Windows, Mac OS, or Linux. But we now have two additional interactive platforms: web and mobile. With HTML5, you can target all of these platforms via technologies such as PhoneGap, Chrome Apps, and TideSDK.

Additionally, several platforms have web apps as native apps or let you install them natively—for example, Chrome OS, Firefox OS, and Android.

There are more technologies than just HTML5 that complement JavaScript and make the language more useful:

JavaScript is getting better build tools (e.g., Grunt) and test tools (e.g., mocha). Node.js makes it possible to run these kinds of tools via a shell (and not only in the browser). One risk in this area is fragmentation, as we are progressively getting too many of these tools.

The JavaScript IDE space is still nascent, but it’s quickly growing up. The complexity and dynamism of web development make this space a fertile ground for innovation. Two open source examples are Brackets and Light Table.

Additionally, browsers are becoming increasingly capable development environments. Chrome, in particular, has made impressive progress recently. It will be interesting to see how much more IDEs and browsers will be integrated in the future.

JavaScript engines have made tremendous progress, evolving from slow interpreters to fast just-in-time compilers. They are now fast enough for most applications. Furthermore, new ideas are already in development to make JavaScript fast enough for the remaining applications:

mapPar, filterPar, and reducePar (parallelizable versions of the existing array methods map, filter, and reduce). In order for parallelization to work, callbacks must be written in a special style; the main restriction is that you can’t mutate data that hasn’t been created inside the callbacks.

A language that is widely used normally has two benefits. First, such a language is better documented and supported. Second, more programmers know it, which is important whenever you need to hire someone or are looking for customers for a tool based on the language.

JavaScript is widely used and reaps both of the aforementioned benefits:

Several things indicate that JavaScript has a bright future:

Considering the preceding list of what makes a language attractive, JavaScript is doing remarkably well. It certainly is not perfect, but at the moment, it is hard to beat—and things are only getting better.

JavaScript’s nature can be summarized as follows:

bind(), built-in map() and reduce() for arrays, etc.) and object-oriented programming (mutable state, objects, inheritance, etc.).

On one hand, JavaScript has several quirks and missing features (for example, it has no block-scoped variables, no built-in modules, and no support for subclassing). Therefore, where you learn language features in other languages, you learn patterns and workarounds in JavaScript. On the other hand, JavaScript includes unorthodox features (such as prototypal inheritance and object properties). These, too, have to be learned, but are more a feature than a bug.

Note that JavaScript engines have become quite smart and fix some of the quirks, under the hood. For example:

But JavaScript also has many elegant parts. Brendan Eich’s favorites are:[1]

The last two items, object literals and array literals, let you start with objects and introduce abstractions (such as constructors, JavaScript’s analog to classes) later. They also enable JSON (see Chapter 22).

Note that the elegant parts help you work around the quirks. For example, they allow you to implement block scoping, modules, and inheritance APIs—all within the language.

JavaScript was influenced by several programming languages (as shown in Figure 3-1):

Date constructor (which is a port of java.util.Date).

function comes from AWK.

onclick.

Knowing why and how JavaScript was created helps us understand why it is the way it is.

In 1993, NCSA’s Mosaic was the first widely popular web browser. In 1994, a company called Netscape was founded to exploit the potential of the nascent World Wide Web. Netscape created the proprietary web browser Netscape Navigator, which was dominant throughout the 1990s. Many of the original Mosaic authors went on to work on Navigator, but the two intentionally shared no code.

Netscape quickly realized that the Web needed to become more dynamic. Even if you simply wanted to check that users entered correct values in a form, you needed to send the data to the server in order to give feedback. In 1995, Netscape hired Brendan Eich with the promise of letting him implement Scheme (a Lisp dialect) in the browser.[2] Before he could get started, Netscape collaborated with hardware and software company Sun (since bought by Oracle) to include its more static programming language, Java, in Navigator. As a consequence, a hotly debated question at Netscape was why the Web needed two programming languages: Java and a scripting language. The proponents of a scripting language offered the following explanation:[3]

We aimed to provide a “glue language” for the Web designers and part time programmers who were building Web content from components such as images, plugins, and Java applets. We saw Java as the “component language” used by higher-priced programmers, where the glue programmers—the Web page designers—would assemble components and automate their interactions using [a scripting language].

By then, Netscape management had decided that a scripting language had to have a syntax similar to Java’s. That ruled out adopting existing languages such as Perl, Python, TCL, or Scheme. To defend the idea of JavaScript against competing proposals, Netscape needed a prototype. Eich wrote one in 10 days, in May 1995. JavaScript’s first code name was Mocha, coined by Marc Andreesen. Netscape marketing later changed it to LiveScript, for trademark reasons and because the names of several products already had the prefix “Live.” In late November 1995, Navigator 2.0B3 came out and included the prototype, which continued its early existence without major changes. In early December 1995, Java’s momentum had grown, and Sun licensed the trademark Java to Netscape. The language was renamed again, to its final name, JavaScript.[4]

[2] Brendan Eich, “Popularity,” April 3, 2008, http://bit.ly/1lKl6fG.

[3] Naomi Hamilton, “The A–Z of Programming Languages: JavaScript,” Computerworld, July 30, 2008, http://bit.ly/1lKldIe.

[4] Paul Krill, “JavaScript Creator Ponders Past, Future,” InfoWorld, June 23, 2008, http://bit.ly/1lKlpXO; Brendan Eich, “A Brief History of JavaScript,” July 21, 2010, http://bit.ly/1lKkI0M.

After JavaScript came out, Microsoft implemented the same language, under the different name JScript, in Internet Explorer 3.0 (August 1996). Partially to keep Microsoft in check, Netscape decided to standardize JavaScript and asked the standards organization Ecma International to host the standard. Work on a specification called ECMA-262 started in November 1996. Because Sun (now Oracle) had a trademark on the word Java, the official name of the language to be standardized couldn’t be JavaScript. Hence, ECMAScript was chosen, derived from JavaScript and Ecma. However, that name is used only to refer to versions of the language (where one refers to the specification). Everyone still calls the language JavaScript.

ECMA-262 is managed and evolved by Ecma’s Technical Committee 39 (TC39). Its members are companies such as Microsoft, Mozilla, and Google, which appoint employees to participate in committee work; examples include Brendan Eich, Allen Wirfs-Brock (editor of ECMA-262), and David Herman. To advance the design of ECMAScript, TC39 hosts discussions on open channels (such as the mailing list es-discuss) and holds regular meetings. The meetings are attended by TC39 members and invited experts. In early 2013, attendee numbers ranged from 15 to 25.

The following is a list of ECMAScript versions (or editions of ECMA-262) and their key features:

do-while, regular expressions, new string methods (concat, match, replace, slice, split with a regular expression, etc.), exception handling, and more

ECMAScript 4 was developed as the next version of JavaScript, with a prototype written in ML. However, TC39 could not agree on its feature set. To prevent an impasse, the committee met at the end of July 2008 and came to an accord, summarized in four points:

Thus, the ECMAScript 4 developers agreed to make Harmony less radical than ECMAScript 4, and the rest of TC39 agreed to keep moving things forward.

Reaching consensus and creating a standard is not always easy, but thanks to the collaborative efforts of the aforementioned parties, JavaScript is a truly open language, with implementations by multiple vendors that are remarkably compatible. That compatibility is made possible by a very detailed yet concrete specification. For example, the specification often uses pseudocode, and it is complemented by a test suite, test262, that checks an ECMAScript implementation for compliance. It is interesting to note that ECMAScript is not managed by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). TC39 and the W3C collaborate wherever there is overlap between JavaScript and HTML5.

It took JavaScript a long time to make an impact. Many JavaScript-related technologies existed for a while until they were discovered by the mainstream. This section describes what happened from JavaScript’s creation until today. Throughout, only the most popular projects are mentioned and many are ignored, even if they were first. For example, the Dojo Toolkit is listed, but there is also the lesser-known qooxdoo, which was created around the same time. And Node.js is listed, even though Jaxer existed before it:

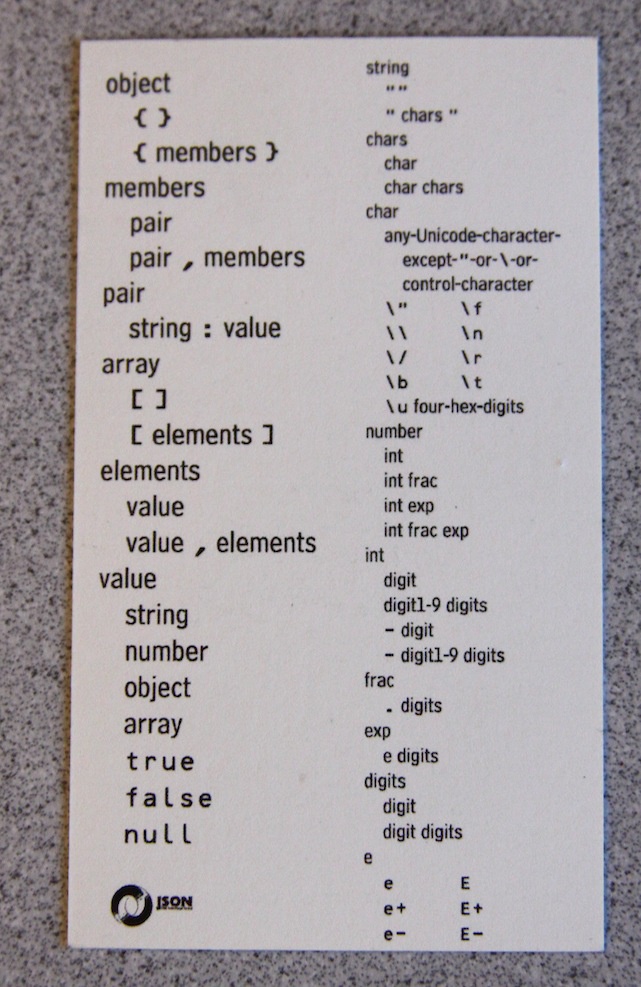

In 2001, Douglas Crockford named and documented JSON (JavaScript Object Notation), whose main idea is to use JavaScript syntax to store data in text format. JSON uses JavaScript literals for objects, arrays, strings, numbers, and booleans to represent structured data. For example:

{"first":"Jane","last":"Porter","married":true,"born":1890,"friends":["Tarzan","Cheeta"]}

Over the years, JSON has become a popular lightweight alternative to XML, especially when structured data is to be represented and not markup. Naturally, JSON is easy to consume via JavaScript (see Chapter 22).

Ajax is a collection of technologies that brings a level of interactivity to web pages that rivals that of desktop applications. One impressive example of what can be achieved via Ajax was introduced in February 2005: Google Maps. This application allowed you to pan and zoom over a map of the world, but only the content that was currently visible was downloaded to the browser. After Google Maps came out, Jesse James Garrett noticed that it shared certain traits with other interactive websites. He called these traits Ajax, a shorthand for Asynchronous JavaScript and XML.[5] The two cornerstones of Ajax are loading content asynchronously in the background (via XMLHttpRequest) and dynamically updating the current page with the results (via dynamic HTML). That was a considerable usability improvement from always performing complete page reloads.

Ajax marked the mainstream breakthrough of JavaScript and dynamic web applications. It is interesting to note how long that took—at that point, the Ajax ingredients had been available for years. Since the inception of Ajax, other data formats have become popular (JSON instead of XML), other protocols are used (e.g., Web Sockets in addition to HTTP), and bidirectional communication is possible. But the basic techniques are still the same. However, the term Ajax is used much less these days and has mostly been replaced by the more comprehensive terms HTML5 and Web Platform (which both mean JavaScript plus browser APIs).

Node.js lets you implement servers that perform well under load. To do so, it uses event-driven, nonblocking I/O and JavaScript (via V8). Node.js creator Ryan Dahl mentions the following reasons for choosing JavaScript:

Dahl was able to build on prior work on event-driven servers and server-side JavaScript (mainly the CommonJS project).

The appeal of Node.js for JavaScript programmers goes beyond being able to program in a familiar language; you get to use the same language on both client and server. That means you can share more code (e.g., for validating data) and use techniques such as isomorphic JavaScript. Isomorphic JavaScript is about assembling web pages on either client or server, with numerous benefits: pages can be rendered on the server for faster initial display, SEO, and running on browsers that either don’t support JavaScript or a version that is too old. But they can also be updated on the client, resulting in a more responsive user interface.

With Chrome OS, the web platform is the native platform. This approach has several advantages:

The introduction of the mobile operating system webOS (which originated at Palm and is now owned by LG Electronics) predates the introduction of Chrome OS, but the “browser as OS” idea is more apparent with the latter (which is why it was chosen as a milestone). webOS is both less and more. Less, because it is very focused on cell phones and tablets. More, because it has Node.js built in, to let you implement services in JavaScript. A more recent entry in the web operating system category is Mozilla’s Firefox OS, which targets cell phones and tablets. Mozilla’s wiki mentions a benefit of web operating systems for the Web:

We also need a hill to take, in order to scope and focus our efforts. Recently we saw the pdf.js project [which renders PDFs via HTML5, without plugins] expose small gaps that needed filling in order for “HTML5” to be a superset of PDF. We want to take a bigger step now, and find the gaps that keep web developers from being able to build apps that are—in every way—the equals of native apps built for the iPhone, Android, and WP7.

This part is a comprehensive reference of the JavaScript language.

JavaScript’s syntax is fairly straightforward. This chapter describes things to watch out for.

This section gives you a quick impression of what JavaScript’s syntax looks like.

The following are five fundamental kinds of values:

Here are a few examples of basic syntax:

// Two slashes start single-linecommentsvarx;// declaring a variablex=3+y;// assigning a value to the variable `x`foo(x,y);// calling function `foo` with parameters `x` and `y`obj.bar(3);// calling method `bar` of object `obj`// A conditional statementif(x===0){// Is `x` equal to zero?x=123;}// Defining function `baz` with parameters `a` and `b`functionbaz(a,b){returna+b;}

Note the two different uses of the equals sign:

=) is used to assign a value to a variable.

===) is used to compare two values (see Equality Operators).

There are two kinds of comments:

Single-line comments via // extend to the rest of the line. Here’s an example:

vara=0;// init

Multiline comments via /* */ can extend over arbitrary ranges of text. They cannot be nested. Here are two examples:

/* temporarily disabledprocessNext(queue);*/function(a/* int */,b/* str */){}

This section looks at an important syntactic distinction in JavaScript: the difference between expressions and statements.

An expression produces a value and can be written wherever a value is expected—for example, as an argument in a function call or at the right side of an assignment. Each of the following lines contains an expression:

myvar3+xmyfunc('a','b')

Roughly, a statement performs an action. Loops and if statements are examples of statements. A program is basically a sequence of statements.[6]

Wherever JavaScript expects a statement, you can also write an expression. Such a statement is called an expression statement. The reverse does not hold: you cannot write a statement where JavaScript expects an expression. For example, an if statement cannot become the argument of a function.

The difference between statements and expressions becomes clearer if we look at members of the two syntactic categories that are similar: the if statement and the conditional operator (an expression).

The following is an example of an if statement:

varsalutation;if(male){salutation='Mr.';}else{salutation='Mrs.';}

There is a similar kind of expression, the conditional operator. The preceding statements are equivalent to the following code:

varsalutation=(male?'Mr.':'Mrs.');

The code between the equals sign and the semicolon is an expression. The parentheses are not necessary, but I find the conditional operator easier to read if I put it in parens.

Two kinds of expressions look like statements—they are ambiguous with regard to their syntactic category:

Object literals (expressions) look like blocks (statements):

{foo:bar(3,5)}

The preceding construct is either an object literal (details: Object Literals) or a block followed by the label foo:, followed by the function call bar(3, 5).

Named function expressions look like function declarations (statements):

functionfoo(){}

The preceding construct is either a named function expression or a function declaration. The former produces a function, the latter creates a variable and assigns a function to it (details on both kinds of function definition: Defining Functions).

In order to prevent ambiguity during parsing, JavaScript does not let you use object literals and function expressions as statements. That is, expression statements must not start with:

function

If an expression starts with either of those tokens, it can only appear in an expression context. You can comply with that requirement by, for example, putting parentheses around the expression. Next, we’ll look at two examples where that is necessary.

eval parses its argument in statement context. You have to put parentheses around an object literal if you want eval to return an object:

> eval('{ foo: 123 }')

123

> eval('({ foo: 123 })')

{ foo: 123 }The following code is an immediately invoked function expression (IIFE), a function whose body is executed right away (you’ll learn what IIFEs are used for in Introducing a New Scope via an IIFE):

> (function () { return 'abc' }())

'abc'If you omit the parentheses, you get a syntax error, because JavaScript sees a function declaration, which can’t be anonymous:

> function () { return 'abc' }()

SyntaxError: function statement requires a nameIf you add a name, you also get a syntax error, because function declarations can’t be immediately invoked:

> function foo() { return 'abc' }()

SyntaxError: Unexpected token )Whatever follows a function declaration must be a legal statement and () isn’t.

For control flow statements, the body is a single statement. Here are two examples:

if(obj!==null)obj.foo();while(x>0)x--;

However, any statement can always be replaced by a block, curly braces containing zero or more statements. Thus, you can also write:

if(obj!==null){obj.foo();}while(x>0){x--;}

I prefer the latter form of control flow statement. Standardizing on it means that there is no difference between single-statement bodies and multistatement bodies. As a consequence, your code looks more consistent, and alternating between one statement and more than one statement is easier.

In this section, we examine how semicolons are used in JavaScript. The basic rules are:

Semicolons are optional in JavaScript. Missing semicolons are added via so-called automatic semicolon insertion (ASI; see Automatic Semicolon Insertion). However, that feature doesn’t always work as expected, which is why you should always include semicolons.

The following statements are not terminated by semicolons if they end with a block:

for, while (but not do-while)

if, switch, try

Here’s an example of while versus do-while:

while(a>0){a--;}// no semicolondo{a--;}while(a>0);

And here’s an example of a function declaration versus a function expression. The latter is followed by a semicolon, because it appears inside a var declaration (which is terminated by a semicolon):

functionfoo(){// ...}// no semicolonvarfoo=function(){// ...};

If you do add a semicolon after a block, you do not get a syntax error, because it is considered an empty statement (see the next section).

That’s most of what you need to know about semicolons. If you always add semicolons, you can probably get by without reading the remaining parts of this section.

A semicolon on its own is an empty statement and does nothing. Empty statements can appear anywhere a statement is expected. They are useful in situations where a statement is demanded, but not needed. In such situations, blocks are usually also allowed. For example, the following two statements are equivalent:

while(processNextItem()>0);while(processNextItem()>0){}

The function processNextItem is assumed to return the number of

remaining items. The following program, consisting of three empty statements, is also syntactically correct:

;;;The goal of automatic semicolon insertion (ASI) is to make semicolons optional at the end of a line. The image invoked by the term automatic semicolon insertion is that the JavaScript parser inserts semicolons for you (internally, things are usually handled differently).

Put another way, ASI helps the parser to determine when a statement ends. Normally, it ends with a semicolon. ASI dictates that a statement also ends if:

The following code contains a line terminator followed by an illegal token:

if(a<0)a=0console.log(a)

The token console is illegal after 0 and triggers ASI:

if(a<0)a=0;console.log(a);

In the following code, the statement inside the braces is not terminated by a semicolon:

functionadd(a,b){returna+b}

ASI creates a syntactically correct version of the preceding code:

functionadd(a,b){returna+b;}

ASI is also triggered if there is a line terminator after the keyword return. For example:

// Don't do thisreturn{name:'John'};

ASI turns the preceding into:

return;{name:'John'};

That’s an empty return, followed by a block with the label name in front of the expression statement 'John'. After the block, there is an empty statement.

Sometimes a statement in a new line starts with a token that is allowed as a continuation of the previous statement. Then ASI is not triggered, even though it seems like it should be. For example:

func()['ul','ol'].foreach(function(t){handleTag(t)})

The square brackets in the second line are interpreted as an index into the result returned by func(). The comma inside the brackets is interpreted as the comma operator (which returns 'ol' in this case; see The Comma Operator). Thus, JavaScript sees the previous code as:

func()['ol'].foreach(function(t){handleTag(t)});

Identifiers are used for naming things and appear in various syntactic roles in JavaScript. For example, the names of variables and unquoted property keys must be valid identifiers. Identifiers are case sensitive.

The first character of an identifier is one of:

$)

_)

Subsequent characters are:

Examples of legal identifiers:

varε=0.0001;varстрока='';var_tmp;var$foo2;

Even though this enables you to use a variety of human languages in JavaScript code, I recommend sticking with English, for both identifiers and comments. That ensures that your code is understandable by the largest possible group of people, which is important, given how much code can spread internationally these days.

The following identifiers are reserved words—they are part of the syntax and can’t be used as variable names (including function names and parameter names):

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The following three identifiers are not reserved words, but you should treat them as if they were:

|

|

|

Lastly, you should also stay away from the names of standard global variables (see Chapter 23). You can use them for local variables without breaking anything, but your code still becomes confusing.

Note that you can use reserved words as unquoted property keys (as of ECMAScript 5):

> var obj = { function: 'abc' };

> obj.function

'abc'You can look up the precise rules for identifiers in Mathias Bynens’s blog post “Valid JavaScript variable names”.

With method invocations, it is important to distinguish between the floating-point dot and the method invocation dot. Thus, you cannot write 1.toString(); you must use one of the following alternatives:

1..toString()1.toString()// space before dot(1).toString()1.0.toString()

ECMAScript 5 has a strict mode that results in cleaner JavaScript, with fewer unsafe features, more warnings, and more logical behavior. The normal (nonstrict) mode is sometimes called “sloppy mode.”

You switch strict mode on by typing the following line first in your JavaScript file or inside your <script> element:

'use strict';

Note that JavaScript engines that don’t support ECMAScript 5 will simply ignore the preceding statement, as writing strings in this manner (as an expression statement; see Statements) normally does nothing.

You can also switch on strict mode per function. To do so, write your function like this:

functionfoo(){'use strict';...}

This is handy when you are working with a legacy code base where switching on strict mode everywhere may break things.

In general, the changes enabled by strict mode are all for the better. Thus, it is highly recommended to use it for new code you write—simply switch it on at the beginning of a file. There are, however, two caveats:

The following sections explain the strict mode features in more detail. You normally don’t need to know them, as you will mostly get more warnings for things that you shouldn’t do anyway.

All variables must be explicitly declared in strict mode. This helps to prevent typos. In sloppy mode, assigning to an undeclared variable creates a global variable:

functionsloppyFunc(){sloppyVar=123;}sloppyFunc();// creates global variable `sloppyVar`console.log(sloppyVar);// 123

In strict mode, assigning to an undeclared variable throws an exception:

functionstrictFunc(){'use strict';strictVar=123;}strictFunc();// ReferenceError: strictVar is not defined

Strict mode limits function-related features.

In strict mode, all functions must be declared at the top level of a scope (global scope or directly inside a function). That means that you can’t put a function declaration inside a block. If you do, you get a descriptive SyntaxError. For example, V8 tells you: “In strict mode code, functions can only be declared at top level or immediately within another function”:

functionstrictFunc(){'use strict';{// SyntaxError:functionnested(){}}}

That is something that isn’t useful anyway, because the function is created in the scope of the surrounding function, not “inside” the block.

If you want to work around this limitation, you can create a function inside a block via a variable declaration and a function expression:

functionstrictFunc(){'use strict';{// OK:varnested=function(){};}}

The rules for function parameters are less permissive: using the same parameter name twice is forbidden, as are local variables that have the same name as a parameter.

The arguments object is simpler in strict mode: the properties arguments.callee and arguments.caller have been eliminated, you can’t assign to the variable arguments, and arguments does not track changes to parameters (if a parameter changes, the corresponding array element does not change with it). Deprecated features of arguments explains the details.

In sloppy mode, the value of this in nonmethod functions is the global object (window in browsers; see The Global Object):

functionsloppyFunc(){console.log(this===window);// true}

In strict mode, it is undefined:

functionstrictFunc(){'use strict';console.log(this===undefined);// true}

This is useful for constructors. For example, the following constructor, Point, is in strict mode:

functionPoint(x,y){'use strict';this.x=x;this.y=y;}

Due to strict mode, you get a warning when you accidentally forget new and call it as a function:

> var pt = Point(3, 1); TypeError: Cannot set property 'x' of undefined

In sloppy mode, you don’t get a warning, and global variables x and y are created. Consult Tips for Implementing Constructors for details.

Illegal manipulations of properties throw exceptions in strict mode. For example, attempting to set the value of a read-only property throws an exception, as does attempting to delete a nonconfigurable property. Here is an example of the former:

varstr='abc';functionsloppyFunc(){str.length=7;// no effect, silent failureconsole.log(str.length);// 3}functionstrictFunc(){'use strict';str.length=7;// TypeError: Cannot assign to// read-only property 'length'}

In sloppy mode, you can delete a global variable foo like this:

deletefoo

In strict mode, you get a syntax error whenever you try to delete unqualified identifiers. You can still delete global variables like this:

deletewindow.foo;// browsersdeleteglobal.foo;// Node.jsdeletethis.foo;// everywhere (in global scope)

In strict mode, the eval() function becomes less quirky: variables declared in the evaluated string are not added to the scope surrounding eval() anymore. For details, consult Evaluating Code Using eval().

Two more JavaScript features are forbidden in strict mode:

with statement is not allowed anymore (see The with Statement). You get a syntax error at compile time (when loading the code).

No more octal numbers: in sloppy mode, an integer with a leading zero is interpreted as octal (base 8). For example:

> 010 === 8 true

In strict mode, you get a syntax error if you use this kind of literal:

> function f() { 'use strict'; return 010 }

SyntaxError: Octal literals are not allowed in strict mode.JavaScript has most of the values that we have come to expect from programming languages: booleans, numbers, strings, arrays, and so on. All normal values in JavaScript have properties.[7] Each property has a key (or name) and a value. You can think of properties like fields of a record. You use the dot (.) operator to access properties:

> var obj = {}; // create an empty object

> obj.foo = 123; // write property

123

> obj.foo // read property

123

> 'abc'.toUpperCase() // call method

'ABC'This chapter gives an overview of JavaScript’s type system.

JavaScript has only six types, according to Chapter 8 of the ECMAScript language specification:

An ECMAScript language type corresponds to values that are directly manipulated by an ECMAScript programmer using the ECMAScript language. The ECMAScript language types are:

- Undefined, Null

- Boolean, String, Number, and

- Object

Therefore, constructors technically don’t introduce new types, even though they are said to have instances.

In the context of language semantics and type systems, static usually means “at compile time” or “without running a program,” while dynamic means “at runtime.”