“Good developers know how things work. Great developers know why things work.”

We all resonate with this adage. We want to be that person who understands and can explain the underpinning of the systems we depend on. And yet, if you’re a web developer, you might be moving in the opposite direction.

Web development is becoming more and more specialized. What kind of web developer are you? Frontend? Backend? Ops? Big data analytics? UI/UX? Storage? Video? Messaging? I would add “Performance Engineer” making that list of possible specializations even longer.

It’s hard to balance studying the foundations of the technology stack with the need to keep up with the latest innovations. And yet, if we don’t understand the foundation our knowledge is hollow, shallow. Knowing how to use the topmost layers of the technology stack isn’t enough. When the complex problems need to be solved, when the inexplicable happens, the person who understands the foundation leads the way.

That’s why High Performance Browser Networking is an important book. If you’re a web developer, the foundation of your technology stack is the Web and the myriad of networking protocols it rides on: TCP, TLS, UDP, HTTP, and many others. Each of these protocols has its own performance characteristics and optimizations, and to build high performance applications you need to understand why the network behaves the way it does.

Thank goodness you’ve found your way to this book. I wish I had this book when I started web programming. I was able to move forward by listening to people who understood the why of networking and read specifications to fill in the gaps. High Performance Browser Networking combines the expertise of a networking guru, Ilya Grigorik, with the necessary information from the many relevant specifications, all woven together in one place.

In High Performance Browser Networking, Ilya explains many whys of networking: Why latency is the performance bottleneck. Why TCP isn’t always the best transport mechanism and UDP might be your better choice. Why reusing connections is a critical optimization. He then goes even further by providing specific actions for improving networking performance. Want to reduce latency? Terminate sessions at a server closer to the client. Want to increase connection reuse? Enable connection keep-alive. The combination of understanding what to do and why it matters turns this knowledge into action.

Ilya explains the foundation of networking and builds on that to introduce the latest advances in protocols and browsers. The benefits of HTTP/2 are explained. XHR is reviewed and its limitations motivate the introduction of Cross-Origin Resource Sharing. Server-Sent Events, WebSockets, and WebRTC are also covered, bringing us up to date on the latest in browser networking.

Viewing the foundation and latest advances in networking from the perspective of performance is what ties the book together. Performance is the context that helps us see the why of networking and translate that into how it affects our website and our users. It transforms abstract specifications into tools that we can wield to optimize our websites and create the best user experience possible. That’s important. That’s why you should read this book.

The web browser is the most widespread deployment platform available to developers today: it is installed on every smartphone, tablet, laptop, desktop, and every other form factor in between. In fact, current cumulative industry growth projections put us on track for 20 billion connected devices by 2020—each with a browser, and at the very least, WiFi or a cellular connection. The type of platform, manufacturer of the device, or the version of the operating system do not matter—each and every device will have a web browser, which by itself is getting more feature rich each day.

The browser of yesterday looks nothing like what we now have access to, thanks to all the recent innovations: HTML and CSS form the presentation layer, JavaScript is the new assembly language of the Web, and new HTML5 APIs are continuing to improve and expose new platform capabilities for delivering engaging, high-performance applications. There is simply no other technology, or platform, that has ever had the reach or the distribution that is made available to us today when we develop for the browser. And where there is big opportunity, innovation always follows.

In fact, there is no better example of the rapid progress and innovation than the networking infrastructure within the browser. Historically, we have been restricted to simple HTTP request-response interactions, and today we have mechanisms for efficient streaming, bidirectional and real-time communication, ability to deliver custom application protocols, and even peer-to-peer videoconferencing and data delivery directly between the peers—all with a few dozen lines of JavaScript.

The net result? Billions of connected devices, a swelling userbase for existing and new online services, and high demand for high-performance web applications. Speed is a feature, and in fact, for some applications it is the feature, and delivering a high-performance web application requires a solid foundation in how the browser and the network interact. That is the subject of this book.

Our goal is to cover what every developer should know about the network: what protocols are being used and their inherent limitations, how to best optimize your applications for the underlying network, and what networking capabilities the browser offers and when to use them.

In the process, we will look at the internals of TCP, UDP, and TLS protocols, and how to optimize our applications and infrastructure for each one. Then we’ll take a deep dive into how the wireless and mobile networks work under the hood—this radio thing, it’s very different—and discuss its implications for how we design and architect our applications. Finally, we will dissect how the HTTP protocol works under the hood and investigate the many new and exciting networking capabilities in the browser:

Understanding how the individual bits are delivered, and the properties of each transport and protocol in use are essential knowledge for delivering high-performance applications. After all, if our applications are blocked waiting on the network, then no amount of rendering, JavaScript, or any other form of optimization will help! Our goal is to eliminate this wait time by getting the best possible performance from the network.

High-Performance Browser Networking will be of interest to anyone interested in optimizing the delivery and performance of her applications, and more generally, curious minds that are not satisfied with a simple checklist but want to know how the browser and the underlying protocols actually work under the hood. The “how” and the “why” go hand in hand: we’ll cover practical advice about configuration and architecture, and we’ll also explore the trade-offs and the underlying reasons for each optimization.

Our primary focus is on the protocols and their properties with respect to applications running in the browser. However, all the discussions on TCP, UDP, TLS, HTTP, and just about every other protocol we will cover are also directly applicable to native applications, regardless of the platform.

The following typographical conventions are used in this book:

Constant width

Constant width bold

Constant width italic

This icon signifies a tip, suggestion, or general note.

This icon indicates a warning or caution.

Safari Books Online is an on-demand digital library that delivers expert content in both book and video form from the world’s leading authors in technology and business.

Technology professionals, software developers, web designers, and business and creative professionals use Safari Books Online as their primary resource for research, problem solving, learning, and certification training.

Safari Books Online offers a range of product mixes and pricing programs for organizations, government agencies, and individuals. Subscribers have access to thousands of books, training videos, and prepublication manuscripts in one fully searchable database from publishers like O’Reilly Media, Prentice Hall Professional, Addison-Wesley Professional, Microsoft Press, Sams, Que, Peachpit Press, Focal Press, Cisco Press, John Wiley & Sons, Syngress, Morgan Kaufmann, IBM Redbooks, Packt, Adobe Press, FT Press, Apress, Manning, New Riders, McGraw-Hill, Jones & Bartlett, Course Technology, and dozens more. For more information about Safari Books Online, please visit us online.

Please address comments and questions concerning this book to the publisher:

| O’Reilly Media, Inc. |

| 1005 Gravenstein Highway North |

| Sebastopol, CA 95472 |

| 800-998-9938 (in the United States or Canada) |

| 707-829-0515 (international or local) |

| 707-829-0104 (fax) |

We have a web page for this book, where we list errata, examples, and any additional information. You can access this page at http://oreil.ly/high-performance-browser.

To comment or ask technical questions about this book, send email to bookquestions@oreilly.com.

For more information about our books, courses, conferences, and news, see our website at http://www.oreilly.com.

Find us on Facebook: http://facebook.com/oreilly

Follow us on Twitter: http://twitter.com/oreillymedia

Watch us on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/oreillymedia

The emergence and the fast growth of the web performance optimization (WPO) industry within the past few years is a telltale sign of the growing importance and demand for speed and faster user experiences by the users. And this is not simply a psychological need for speed in our ever accelerating and connected world, but a requirement driven by empirical results, as measured with respect to the bottom-line performance of the many online businesses:

Simply put, speed is a feature. And to deliver it, we need to understand the many factors and fundamental limitations that are at play. In this chapter, we will focus on the two critical components that dictate the performance of all network traffic: latency and bandwidth (Figure 1-1).

Armed with a better understanding of how bandwidth and latency work together, we will then have the tools to dive deeper into the internals and performance characteristics of TCP, UDP, and all application protocols above them.

Latency is the time it takes for a message, or a packet, to travel from its point of origin to the point of destination. That is a simple and useful definition, but it often hides a lot of useful information—every system contains multiple sources, or components, contributing to the overall time it takes for a message to be delivered, and it is important to understand what these components are and what dictates their performance.

Let’s take a closer look at some common contributing components for a typical router on the Internet, which is responsible for relaying a message between the client and the server:

The total latency between the client and the server is the sum of all the delays just listed. Propagation time is dictated by the distance and the medium through which the signal travels—as we will see, the propagation speed is usually within a small constant factor of the speed of light. On the other hand, transmission delay is dictated by the available data rate of the transmitting link and has nothing to do with the distance between the client and the server. As an example, let’s assume we want to transmit a 10 Mb file over two links: 1 Mbps and 100 Mbps. It will take 10 seconds to put the entire file on the “wire” over the 1 Mbps link and only 0.1 seconds over the 100 Mbps link.

Next, once the packet arrives at the router, the router must examine the packet header to determine the outgoing route and may run other checks on the data—this takes time as well. Much of this logic is now often done in hardware, so the delays are very small, but they do exist. And, finally, if the packets are arriving at a faster rate than the router is capable of processing, then the packets are queued inside an incoming buffer. The time data spends queued inside the buffer is, not surprisingly, known as queuing delay.

Each packet traveling over the network will incur many instances of each of these delays. The farther the distance between the source and destination, the more time it will take to propagate. The more intermediate routers we encounter along the way, the higher the processing and transmission delays for each packet. Finally, the higher the load of traffic along the path, the higher the likelihood of our packet being delayed inside an incoming buffer.

As Einstein outlined in his theory of special relativity, the speed of light is the maximum speed at which all energy, matter, and information can travel. This observation places a hard limit, and a governor, on the propagation time of any network packet.

The good news is the speed of light is high: 299,792,458 meters per second, or 186,282 miles per second. However, and there is always a however, that is the speed of light in a vacuum. Instead, our packets travel through a medium such as a copper wire or a fiber-optic cable, which will slow down the signal (Table 1-1). This ratio of the speed of light and the speed with which the packet travels in a material is known as the refractive index of the material. The larger the value, the slower light travels in that medium.

The typical refractive index value of an optical fiber, through which most of our packets travel for long-distance hops, can vary between 1.4 to 1.6—slowly but surely we are making improvements in the quality of the materials and are able to lower the refractive index. But to keep it simple, the rule of thumb is to assume that the speed of light in fiber is around 200,000,000 meters per second, which corresponds to a refractive index of ~1.5. The remarkable part about this is that we are already within a small constant factor of the maximum speed! An amazing engineering achievement in its own right.

| Route | Distance | Time, light in vacuum | Time, light in fiber | Round-trip time (RTT) in fiber |

New York to San Francisco | 4,148 km | 14 ms | 21 ms | 42 ms |

New York to London | 5,585 km | 19 ms | 28 ms | 56 ms |

New York to Sydney | 15,993 km | 53 ms | 80 ms | 160 ms |

Equatorial circumference | 40,075 km | 133.7 ms | 200 ms | 200 ms |

The speed of light is fast, but it nonetheless takes 160 milliseconds to make the round-trip (RTT) from New York to Sydney. In fact, the numbers in Table 1-1 are also optimistic in that they assume that the packet travels over a fiber-optic cable along the great-circle path (the shortest distance between two points on the globe) between the cities. In practice, no such cable is available, and the packet would take a much longer route between New York and Sydney. Each hop along this route will introduce additional routing, processing, queuing, and transmission delays. As a result, the actual RTT between New York and Sydney, over our existing networks, works out to be in the 200–300 millisecond range. All things considered, that still seems pretty fast, right?

We are not accustomed to measuring our everyday encounters in milliseconds, but studies have shown that most of us will reliably report perceptible “lag” once a delay of over 100–200 milliseconds is introduced into the system. Once the 300 millisecond delay threshold is exceeded, the interaction is often reported as “sluggish,” and at the 1,000 milliseconds (1 second) barrier, many users have already performed a mental context switch while waiting for the response—anything from a daydream to thinking about the next urgent task.

The conclusion is simple: to deliver the best experience and to keep our users engaged in the task at hand, we need our applications to respond within hundreds of milliseconds. That doesn’t leave us, and especially the network, with much room for error. To succeed, network latency has to be carefully managed and be an explicit design criteria at all stages of development.

Content delivery network (CDN) services provide many benefits, but chief among them is the simple observation that distributing the content around the globe, and serving that content from a nearby location to the client, will allow us to significantly reduce the propagation time of all the data packets.

We may not be able to make the packets travel faster, but we can reduce the distance by strategically positioning our servers closer to the users! Leveraging a CDN to serve your data can offer significant performance benefits.

Ironically, it is often the last few miles, not the crossing of oceans or continents, where significant latency is introduced: the infamous last-mile problem. To connect your home or office to the Internet, your local ISP needs to route the cables throughout the neighborhood, aggregate the signal, and forward it to a local routing node. In practice, depending on the type of connectivity, routing methodology, and deployed technology, these first few hops can take tens of milliseconds just to get to your ISP’s main routers! According to the “Measuring Broadband America” report conducted by the Federal Communications Commission in early 2013, during peak hours:

Fiber-to-the-home, on average, has the best performance in terms of latency, with 18 ms average during the peak period, with cable having 26 ms latency and DSL 44 ms latency.

— FCC February 2013

This translates into 18–44 ms of latency just to the closest measuring node within the ISP’s core network, before the packet is even routed to its destination! The FCC report is focused on the United States, but last-mile latency is a challenge for all Internet providers, regardless of geography. For the curious, a simple traceroute can often tell you volumes about the topology and performance of your Internet provider.

$> traceroute google.comtraceroute to google.com (74.125.224.102), 64 hops max, 52 byte packets 1 10.1.10.1 (10.1.10.1) 7.120 ms 8.925 ms 1.199 ms2 96.157.100.1 (96.157.100.1) 20.894 ms 32.138 ms 28.928 ms 3 x.santaclara.xxxx.com (68.85.191.29) 9.953 ms 11.359 ms 9.686 ms 4 x.oakland.xxx.com (68.86.143.98) 24.013 ms 21.423 ms 19.594 ms 5 68.86.91.205 (68.86.91.205) 16.578 ms 71.938 ms 36.496 ms 6 x.sanjose.ca.xxx.com (68.86.85.78) 17.135 ms 17.978 ms 22.870 ms 7 x.529bryant.xxx.com (68.86.87.142) 25.568 ms 22.865 ms 23.392 ms 8 66.208.228.226 (66.208.228.226) 40.582 ms 16.058 ms 15.629 ms 9 72.14.232.136 (72.14.232.136) 20.149 ms 20.210 ms 18.020 ms 10 64.233.174.109 (64.233.174.109) 63.946 ms 18.995 ms 18.150 ms 11 x.1e100.net (74.125.224.102) 18.467 ms 17.839 ms 17.958 ms

In the previous example, the packet started in the city of Sunnyvale, bounced to Santa Clara, then Oakland, returned to San Jose, got routed to the “529 Bryant” datacenter, at which point it was routed toward Google and arrived at its destination on the 11th hop. This entire process took, on average, 18 milliseconds. Not bad, all things considered, but in the same time the packet could have traveled across most of the continental USA!

The last-mile latency can vary wildly based on your provider, the deployed technology, topology of the network, and even the time of day. As an end user, if you are looking to improve your web browsing speeds, low latency is worth optimizing for when picking a local ISP.

Latency, not bandwidth, is the performance bottleneck for most websites! To understand why, we need to understand the mechanics of TCP and HTTP protocols—subjects we’ll be covering in subsequent chapters. However, if you are curious, feel free to skip ahead to More Bandwidth Doesn’t Matter (Much).

An optical fiber acts as a simple “light pipe,” slightly thicker than a human hair, designed to transmit light between the two ends of the cable. Metal wires are also used but are subject to higher signal loss, electromagnetic interference, and higher lifetime maintenance costs. Chances are, your packets will travel over both types of cable, but for any long-distance hops, they will be transmitted over a fiber-optic link.

Optical fibers have a distinct advantage when it comes to bandwidth because each fiber can carry many different wavelengths (channels) of light through a process known as wavelength-division multiplexing (WDM). Hence, the total bandwidth of a fiber link is the multiple of per-channel data rate and the number of multiplexed channels.

As of early 2010, researchers have been able to multiplex over 400 wavelengths with the peak capacity of 171 Gbit/s per channel, which translates to over 70 Tbit/s of total bandwidth for a single fiber link! We would need thousands of copper wire (electrical) links to match this throughput. Not surprisingly, most long-distance hops, such as subsea data transmission between continents, is now done over fiber-optic links. Each cable carries several strands of fiber (four strands is a common number), which translates into bandwidth capacity in hundreds of terabits per second for each cable.

The backbones, or the fiber links, that form the core data paths of the Internet are capable of moving hundreds of terabits per second. However, the available capacity at the edges of the network is much, much less, and varies wildly based on deployed technology: dial-up, DSL, cable, a host of wireless technologies, fiber-to-the-home, and even the performance of the local router. The available bandwidth to the user is a function of the lowest capacity link between the client and the destination server (Figure 1-1).

Akamai Technologies operates a global CDN, with servers positioned around the globe, and provides free quarterly reports at Akamai’s website on average broadband speeds, as seen by their servers. Table 1-2 captures the macro bandwidth trends as of Q1 2013.

| Rank | Country | Average Mbps | Year-over-year change |

- | Global | 3.1 | 17% |

1 | South Korea | 14.2 | -10% |

2 | Japan | 11.7 | 6.8% |

3 | Hong Kong | 10.9 | 16% |

4 | Switzerland | 10.1 | 24% |

5 | Netherlands | 9.9 | 12% |

… | |||

9 | United States | 8.6 | 27% |

The preceding data excludes traffic from mobile carriers, a topic we will come back to later to examine in closer detail. For now, it should suffice to say that mobile speeds are highly variable and generally slower. However, even with that in mind, the average global broadband bandwidth in early 2013 was just 3.1 Mbps! South Korea led the world with a 14.2 Mbps average throughput, and United States came in 9th place with 8.6 Mbps.

As a reference point, streaming an HD video can require anywhere from 2 to 10 Mbps depending on resolution and the codec. So an average user can stream a lower-resolution video stream at the network edge, but doing so would consume much of their link capacity—not a very promising story for a household with multiple users.

Figuring out where the bandwidth bottleneck is for any given user is often a nontrivial but important exercise. Once again, for the curious, there are a number of online services, such as speedtest.net operated by Ookla (Figure 1-2), which provide upstream and downstream tests to some local server—we will see why picking a local server is important in our discussion on TCP. Running a test on one of these services is a good way to check that your connection meets the advertised speeds of your local ISP.

However, while a high-bandwidth link to your ISP is desirable, it is also not a guarantee of stable end-to-end performance. The network could be congested at any intermediate node at some point in time due to high demand, hardware failures, a concentrated network attack, or a host of other reasons. High variability of throughput and latency performance is an inherent property of our data networks—predicting, managing, and adapting to the continuously changing “network weather” is a complex task.

Our demand for higher bandwidth is growing fast, in large part due to the rising popularity of streaming video, which is now responsible for well over half of all Internet traffic. The good news is, while it may not be cheap, there are multiple strategies available for us to grow the available capacity: we can add more fibers into our fiber-optic links, we can deploy more links across the congested routes, or we can improve the WDM techniques to transfer more data through existing links.

TeleGeography, a telecommunications market research and consulting firm, estimates that as of 2011, we are using, on average, just 20% of the available capacity of the deployed subsea fiber links. Even more importantly, between 2007 and 2011, more than half of all the added capacity of the trans-Pacific cables was due to WDM upgrades: same fiber links, better technology on both ends to multiplex the data. Of course, we cannot expect these advances to go on indefinitely, as every medium reaches a point of diminishing returns. Nonetheless, as long as economics of the enterprise permit, there is no fundamental reason why bandwidth throughput cannot be increased over time—if all else fails, we can add more fiber links.

Improving latency, on the other hand, is a very different story. The quality of the fiber links could be improved to get us a little closer to the speed of light: better materials with lower refractive index and faster routers along the way. However, given that our current speeds are within ~1.5 of the speed of light, the most we can expect from this strategy is just a modest 30% improvement. Unfortunately, there is simply no way around the laws of physics: the speed of light places a hard limit on the minimum latency.

Alternatively, since we can’t make light travel faster, we can make the distance shorter—the shortest distance between any two points on the globe is defined by the great-circle path between them. However, laying new cables is also not always possible due to the constraints imposed by the physical terrain, social and political reasons, and of course, the associated costs.

As a result, to improve performance of our applications, we need to architect and optimize our protocols and networking code with explicit awareness of the limitations of available bandwidth and the speed of light: we need to reduce round trips, move the data closer to the client, and build applications that can hide the latency through caching, pre-fetching, and a variety of similar techniques, as explained in subsequent chapters.

At the heart of the Internet are two protocols, IP and TCP. The IP, or Internet Protocol, is what provides the host-to-host routing and addressing, and TCP, or Transmission Control Protocol, is what provides the abstraction of a reliable network running over an unreliable channel. TCP/IP is also commonly referred to as the Internet Protocol Suite and was first proposed by Vint Cerf and Bob Kahn in their 1974 paper titled “A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication.”

The original proposal (RFC 675) was revised several times, and in 1981 the v4 specification of TCP/IP was published not as one, but as two separate RFCs:

Since then, there have been a number of enhancements proposed and made to TCP, but the core operation has not changed significantly. TCP quickly replaced previous protocols and is now the protocol of choice for many of the most popular applications: World Wide Web, email, file transfers, and many others.

TCP provides an effective abstraction of a reliable network running over an unreliable channel, hiding most of the complexity of network communication from our applications: retransmission of lost data, in-order delivery, congestion control and avoidance, data integrity, and more. When you work with a TCP stream, you are guaranteed that all bytes sent will be identical with bytes received and that they will arrive in the same order to the client. As such, TCP is optimized for accurate delivery, rather than a timely one. This, as it turns out, also creates some challenges when it comes to optimizing for web performance in the browser.

The HTTP standard does not specify TCP as the only transport protocol. If we wanted, we could deliver HTTP via a datagram socket (User Datagram Protocol or UDP), or any other transport protocol of our choice, but in practice all HTTP traffic on the Internet today is delivered via TCP due to the many great features it provides out of the box.

Because of this, understanding some of the core mechanisms of TCP is essential knowledge for building an optimized web experience. Chances are you won’t be working with TCP sockets directly in your application, but the design choices you make at the application layer will dictate the performance of TCP and the underlying network over which your application is delivered.

All TCP connections begin with a three-way handshake (Figure 2-1). Before the client or the server can exchange any application data, they must agree on starting packet sequence numbers, as well as a number of other connection specific variables, from both sides. The sequence numbers are picked randomly from both sides for security reasons.

x and sends a SYN packet, which may also include additional TCP flags and options.

x by one, picks own random sequence number y, appends its own set of flags and options, and dispatches the response.

x and y by one and completes the handshake by dispatching the last ACK packet in the handshake.

Once the three-way handshake is complete, the application data can begin to flow between the client and the server. The client can send a data packet immediately after the ACK packet, and the server must wait for the ACK before it can dispatch any data. This startup process applies to every TCP connection and carries an important implication for performance of all network applications using TCP: each new connection will have a full roundtrip of latency before any application data can be transferred.

For example, if our client is in New York, the server is in London, and we are starting a new TCP connection over a fiber link, then the three-way handshake will take a minimum of 56 milliseconds (Table 1-1): 28 milliseconds to propagate the packet in one direction, after which it must return back to New York. Note that bandwidth of the connection plays no role here. Instead, the delay is governed by the latency between the client and the server, which in turn is dominated by the propagation time between New York and London.

The delay imposed by the three-way handshake makes new TCP connections expensive to create, and is one of the big reasons why connection reuse is a critical optimization for any application running over TCP.

In early 1984, John Nagle documented a condition known as “congestion collapse,” which could affect any network with asymmetric bandwidth capacity between the nodes:

Congestion control is a recognized problem in complex networks. We have discovered that the Department of Defense’s Internet Protocol (IP), a pure datagram protocol, and Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), a transport layer protocol, when used together, are subject to unusual congestion problems caused by interactions between the transport and datagram layers. In particular, IP gateways are vulnerable to a phenomenon we call “congestion collapse”, especially when such gateways connect networks of widely different bandwidth…

Should the roundtrip time exceed the maximum retransmission interval for any host, that host will begin to introduce more and more copies of the same datagrams into the net. The network is now in serious trouble. Eventually all available buffers in the switching nodes will be full and packets must be dropped. The roundtrip time for packets that are delivered is now at its maximum. Hosts are sending each packet several times, and eventually some copy of each packet arrives at its destination. This is congestion collapse.

This condition is stable. Once the saturation point has been reached, if the algorithm for selecting packets to be dropped is fair, the network will continue to operate in a degraded condition.

— John Nagle RFC 896

The report concluded that congestion collapse had not yet become a problem for ARPANET because most nodes had uniform bandwidth, and the backbone had substantial excess capacity. However, neither of these assertions held true for long. In 1986, as the number (5,000+) and the variety of nodes on the network grew, a series of congestion collapse incidents swept throughout the network—in some cases the capacity dropped by a factor of 1,000 and the network became unusable.

To address these issues, multiple mechanisms were implemented in TCP to govern the rate with which the data can be sent in both directions: flow control, congestion control, and congestion avoidance.

Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET) was the precursor to the modern Internet and the world’s first operational packet-switched network. The project was officially launched in 1969, and in 1983 the TCP/IP protocols replaced the earlier NCP (Network Control Program) as the principal communication protocols. The rest, as they say, is history.

Flow control is a mechanism to prevent the sender from overwhelming the receiver with data it may not be able to process—the receiver may be busy, under heavy load, or may only be willing to allocate a fixed amount of buffer space. To address this, each side of the TCP connection advertises (Figure 2-2) its own receive window (rwnd), which communicates the size of the available buffer space to hold the incoming data.

When the connection is first established, both sides initiate their rwnd values by using their system default settings. A typical web page will stream the majority of the data from the server to the client, making the client’s window the likely bottleneck. However, if a client is streaming large amounts of data to the server, such as in the case of an image or a video upload, then the server receive window may become the limiting factor.

If, for any reason, one of the sides is not able to keep up, then it can advertise a smaller window to the sender. If the window reaches zero, then it is treated as a signal that no more data should be sent until the existing data in the buffer has been cleared by the application layer. This workflow continues throughout the lifetime of every TCP connection: each ACK packet carries the latest rwnd value for each side, allowing both sides to dynamically adjust the data flow rate to the capacity and processing speed of the sender and receiver.

Despite the presence of flow control in TCP, network congestion collapse became a real issue in the mid to late 1980s. The problem was that flow control prevented the sender from overwhelming the receiver, but there was no mechanism to prevent either side from overwhelming the underlying network: neither the sender nor the receiver knows the available bandwidth at the beginning of a new connection, and hence need a mechanism to estimate it and also to adapt their speeds to the continuously changing conditions within the network.

To illustrate one example where such an adaptation is beneficial, imagine you are at home and streaming a large video from a remote server that managed to saturate your downlink to deliver the maximum quality experience. Then another user on your home network opens a new connection to download some software updates. All of the sudden, the amount of available downlink bandwidth to the video stream is much less, and the video server must adjust its data rate—otherwise, if it continues at the same rate, the data will simply pile up at some intermediate gateway and packets will be dropped, leading to inefficient use of the network.

In 1988, Van Jacobson and Michael J. Karels documented several algorithms to address these problems: slow-start, congestion avoidance, fast retransmit, and fast recovery. All four quickly became a mandatory part of the TCP specification. In fact, it is widely held that it was these updates to TCP that prevented an Internet meltdown in the ’80s and the early ’90s as the traffic continued to grow at an exponential rate.

To understand slow-start, it is best to see it in action. So, once again, let us come back to our client, who is located in New York, attempting to retrieve a file from a server in London. First, the three-way handshake is performed, during which both sides advertise their respective receive window (rwnd) sizes within the ACK packets (Figure 2-2). Once the final ACK packet is put on the wire, we can start exchanging application data.

The only way to estimate the available capacity between the client and the server is to measure it by exchanging data, and this is precisely what slow-start is designed to do. To start, the server initializes a new congestion window (cwnd) variable per TCP connection and sets its initial value to a conservative, system-specified value (initcwnd on Linux).

The cwnd variable is not advertised or exchanged between the sender and receiver—in this case, it will be a private variable maintained by the server in London. Further, a new rule is introduced: the maximum amount of data in flight (not ACKed) between the client and the server is the minimum of the rwnd and cwnd variables. So far so good, but how do the server and the client determine optimal values for their congestion window sizes? After all, network conditions vary all the time, even between the same two network nodes, as we saw in the earlier example, and it would be great if we could use the algorithm without having to hand-tune the window sizes for each connection.

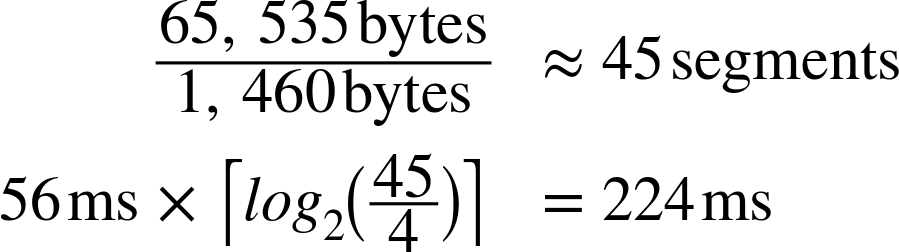

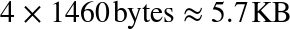

The solution is to start slow and to grow the window size as the packets are acknowledged: slow-start! Originally, the cwnd start value was set to 1 network segment; RFC 2581 updated this value to a maximum of 4 segments in April 1999, and most recently the value was increased once more to 10 segments by RFC 6928 in April 2013.

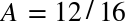

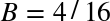

The maximum amount of data in flight for a new TCP connection is the minimum of the rwnd and cwnd values; hence the server can send up to four network segments to the client, at which point it must stop and wait for an acknowledgment. Then, for every received ACK, the slow-start algorithm indicates that the server can increment its cwnd window size by one segment—for every ACKed packet, two new packets can be sent. This phase of the TCP connection is commonly known as the “exponential growth” algorithm (Figure 2-3), as the client and the server are trying to quickly converge on the available bandwidth on the network path between them.

So why is slow-start an important factor to keep in mind when we are building applications for the browser? Well, HTTP and many other application protocols run over TCP, and no matter the available bandwidth, every TCP connection must go through the slow-start phase—we cannot use the full capacity of the link immediately!

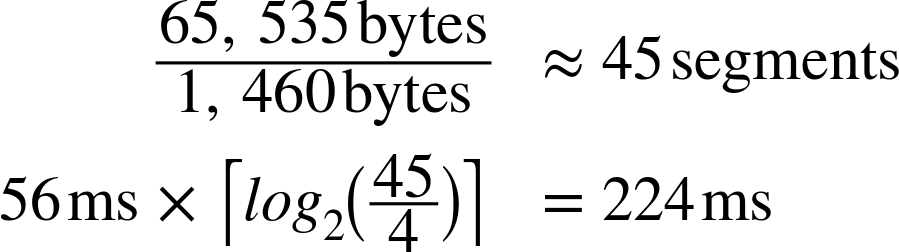

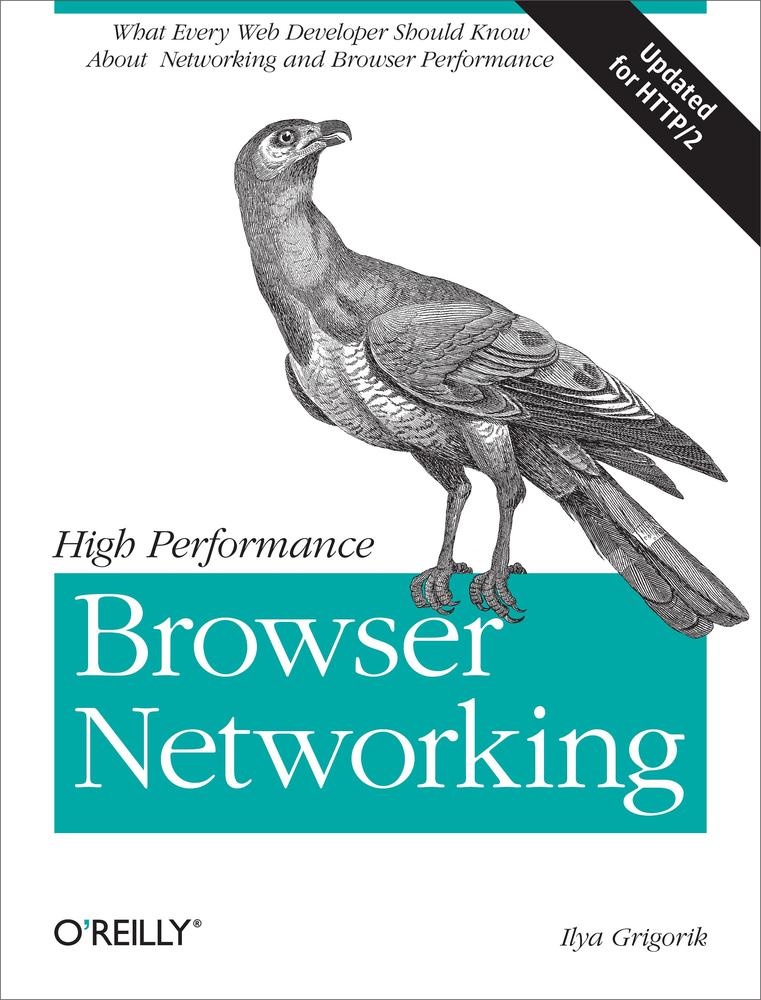

Instead, we start with a small congestion window and double it for every roundtrip—i.e., exponential growth. As a result, the time required to reach a specific throughput target is a function (Equation 2-1) of both the roundtrip time between the client and server and the initial congestion window size.

For a hands-on example of slow-start impact, let’s assume the following scenario:

We will be using the old (RFC 2581) value of four network segments for the initial congestion window in this and the following examples, as it is still the most common value for most servers. Except, you won’t make this mistake—right? The following examples should serve as good motivation for why you should update your servers!

Despite the 64 KB receive window size, the throughput of a new TCP connection is initially limited by the size of the congestion window. In fact, to reach the 64 KB limit, we will need to grow the congestion window size to 45 segments, which will take 224 milliseconds:

That’s four roundtrips (Figure 2-4), and hundreds of milliseconds of latency, to reach 64 KB of throughput between the client and server! The fact that the client and server may be capable of transferring at Mbps+ data rates has no effect—that’s slow-start.

To decrease the amount of time it takes to grow the congestion window, we can decrease the roundtrip time between the client and server—e.g., move the server geographically closer to the client. Or we can increase the initial congestion window size to the new RFC 6928 value of 10 segments.

Slow-start is not as big of an issue for large, streaming downloads, as the client and the server will arrive at their maximum window sizes after a few hundred milliseconds and continue to transmit at near maximum speeds—the cost of the slow-start phase is amortized over the lifetime of the larger transfer.

However, for many HTTP connections, which are often short and bursty, it is not unusual for the request to terminate before the maximum window size is reached. As a result, the performance of many web applications is often limited by the roundtrip time between server and client: slow-start limits the available bandwidth throughput, which has an adverse effect on the performance of small transfers.

To illustrate the impact of the three-way handshake and the slow-start phase on a simple HTTP transfer, let’s assume that our client in New York requests a 20 KB file from the server in London over a new TCP connection (Figure 2-5), and the following connection parameters are in place:

)

)

|

|

Client begins the TCP handshake with the SYN packet. |

|

|

Server replies with SYN-ACK and specifies its rwnd size. |

|

|

Client ACKs the SYN-ACK, specifies its rwnd size, and immediately sends the HTTP GET request. |

|

|

Server receives the HTTP request. |

|

|

Server completes generating the 20 KB response and sends 4 TCP segments before pausing for an ACK (initial cwnd size is 4). |

|

|

Client receives four segments and ACKs each one. |

|

|

Server increments its cwnd for each ACK and sends eight segments. |

|

|

Client receives eight segments and ACKs each one. |

|

|

Server increments its cwnd for each ACK and sends remaining segments. |

|

|

Client receives remaining segments, ACKs each one. |

As an exercise, run through Figure 2-5 with cwnd value set to 10 network segments instead of 4. You should see a full roundtrip of network latency disappear—a 22% improvement in performance!

264 ms to transfer the 20 KB file on a new TCP connection with 56 ms roundtrip time between the client and server! By comparison, let’s now assume that the client is able to reuse the same TCP connection (Figure 2-6) and issues the same request once more.

|

|

Client sends the HTTP request. |

|

|

Server receives the HTTP request. |

|

|

Server completes generating the 20 KB response, but the cwnd value is already greater than the 15 segments required to send the file; hence it dispatches all the segments in one burst. |

|

|

Client receives all 15 segments, ACKs each one. |

The same request made on the same connection, but without the cost of the three-way handshake and the penalty of the slow-start phase, now took 96 milliseconds, which translates into a 275% improvement in performance!

In both cases, the fact that both the server and the client have access to 5 Mbps of upstream bandwidth had no impact during the startup phase of the TCP connection. Instead, the latency and the congestion window sizes were the limiting factors.

In fact, the performance gap between the first and the second request dispatched over an existing connection will only widen if we increase the roundtrip time; as an exercise, try it with a few different values. Once you develop an intuition for the mechanics of TCP congestion control, dozens of optimizations such as keepalive, pipelining, and multiplexing will require little further motivation.

It is important to recognize that TCP is specifically designed to use packet loss as a feedback mechanism to help regulate its performance. In other words, it is not a question of if, but rather of when the packet loss will occur. Slow-start initializes the connection with a conservative window and, for every roundtrip, doubles the amount of data in flight until it exceeds the receiver’s flow-control window, a system-configured congestion threshold (ssthresh) window, or until a packet is lost, at which point the congestion avoidance algorithm (Figure 2-3) takes over.

The implicit assumption in congestion avoidance is that packet loss is indicative of network congestion: somewhere along the path we have encountered a congested link or a router, which was forced to drop the packet, and hence we need to adjust our window to avoid inducing more packet loss to avoid overwhelming the network.

Once the congestion window is reset, congestion avoidance specifies its own algorithms for how to grow the window to minimize further loss. At a certain point, another packet loss event will occur, and the process will repeat once over. If you have ever looked at a throughput trace of a TCP connection and observed a sawtooth pattern within it, now you know why it looks as such: it is the congestion control and avoidance algorithms adjusting the congestion window size to account for packet loss in the network.

Finally, it is worth noting that improving congestion control and avoidance is an active area both for academic research and commercial products: there are adaptations for different network types, different types of data transfers, and so on. Today, depending on your platform, you will likely run one of the many variants: TCP Tahoe and Reno (original implementations), TCP Vegas, TCP New Reno, TCP BIC, TCP CUBIC (default on Linux), or Compound TCP (default on Windows), among many others. However, regardless of the flavor, the core performance implications of congestion control and avoidance hold for all.

The built-in congestion control and congestion avoidance mechanisms in TCP carry another important performance implication: the optimal sender and receiver window sizes must vary based on the roundtrip time and the target data rate between them.

To understand why this is the case, first recall that the maximum amount of unacknowledged, in-flight data between the sender and receiver is defined as the minimum of the receive (rwnd) and congestion (cwnd) window sizes: the current receive windows are communicated in every ACK, and the congestion window is dynamically adjusted by the sender based on the congestion control and avoidance algorithms.

If either the sender or receiver exceeds the maximum amount of unacknowledged data, then it must stop and wait for the other end to ACK some of the packets before proceeding. How long would it have to wait? That’s dictated by the roundtrip time between the two!

If either the sender or receiver are frequently forced to stop and wait for ACKs for previous packets, then this would create gaps in the data flow (Figure 2-7), which would consequently limit the maximum throughput of the connection. To address this problem, the window sizes should be made just big enough, such that either side can continue sending data until an ACK arrives back from the client for an earlier packet—no gaps, maximum throughput. Consequently, the optimal window size depends on the roundtrip time! Pick a low window size, and you will limit your connection throughput, regardless of the available or advertised bandwidth between the peers.

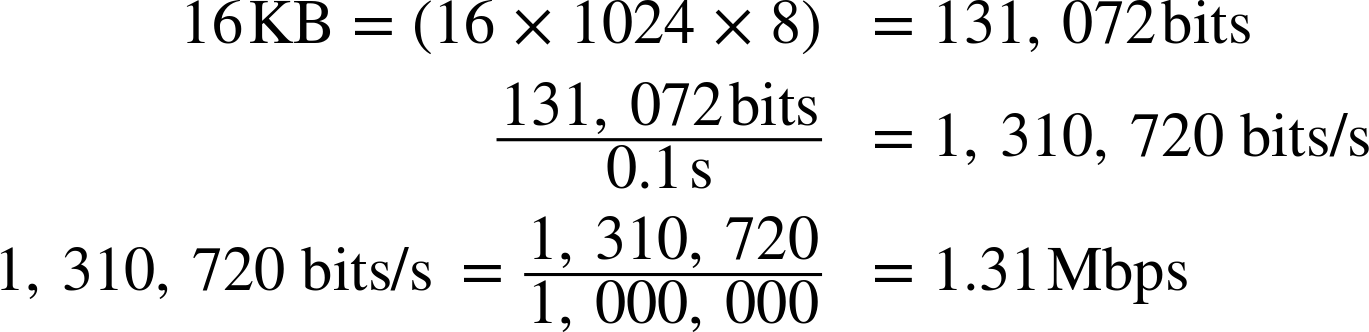

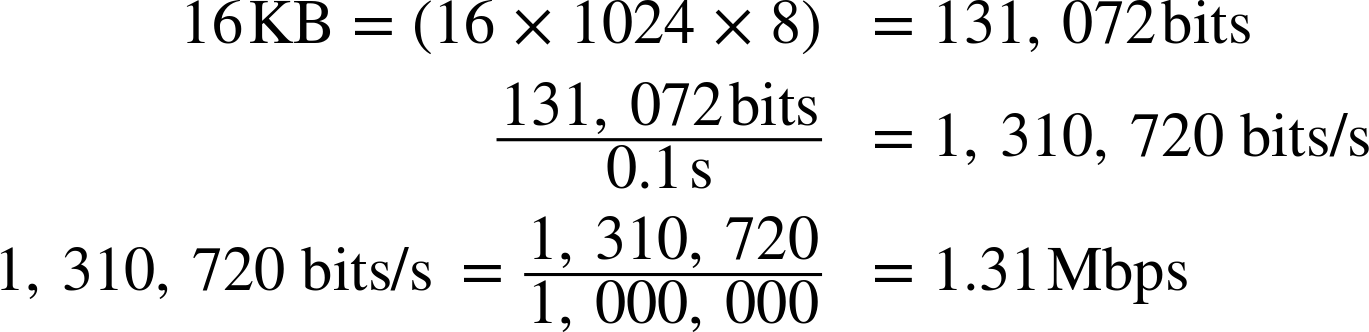

So how big do the flow control (rwnd) and congestion control (cwnd) window values need to be? The actual calculation is a simple one. First, let us assume that the minimum of the cwnd and rwnd window sizes is 16 KB, and the roundtrip time is 100 ms:

Regardless of the available bandwidth between the sender and receiver, this TCP connection will not exceed a 1.31 Mbps data rate! To achieve higher throughput we need to raise the minimum window size or lower the roundtrip time.

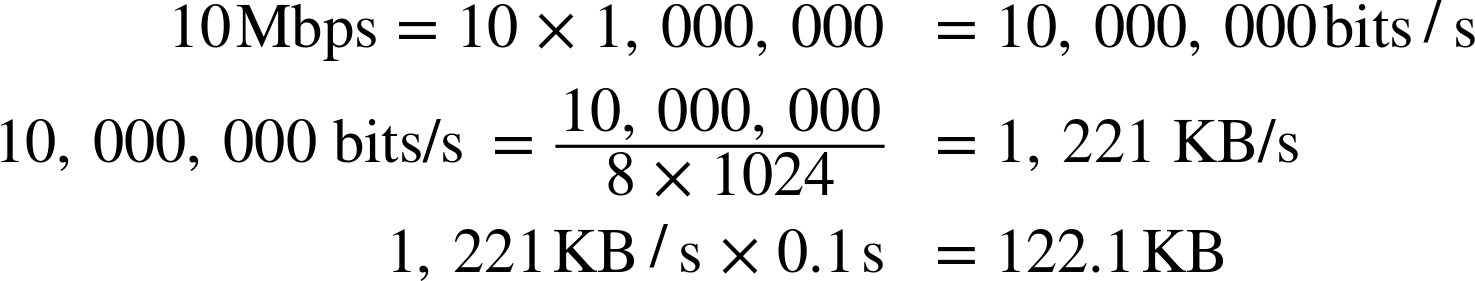

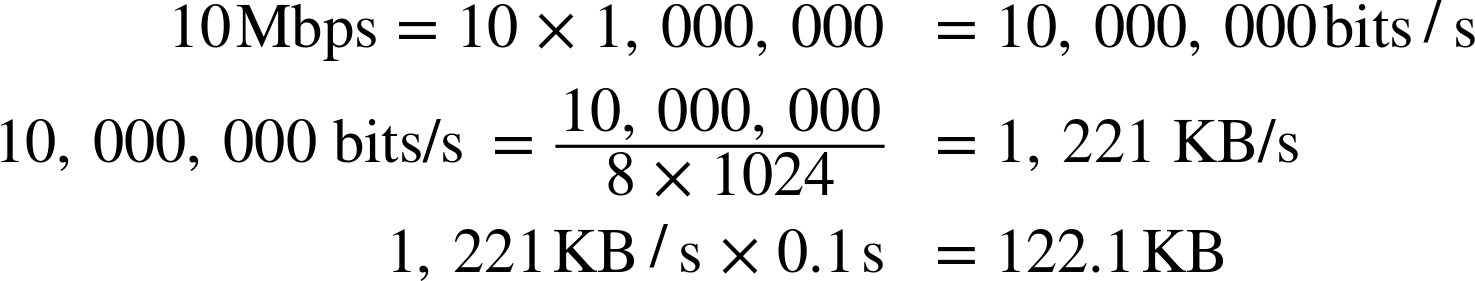

Similarly, we can compute the optimal window size if we know the roundtrip time and the available bandwidth on both ends. In this scenario, let’s assume that the roundtrip time stays the same (100 ms), but the sender has 10 Mbps of available bandwidth, and the receiver is on a high-throughput 100 Mbps+ link. Assuming there is no network congestion between them, our goal is to saturate the 10 Mbps link available to the client:

The window size needs to be at least 122.1 KB to saturate the 10 Mbps link. Recall that the maximum receive window size in TCP is 64 KB unless window scaling—see Window Scaling (RFC 1323)—is present: double-check your client and server settings!

The good news is that the window size negotiation and tuning is managed automatically by the network stack and should adjust accordingly. The bad news is sometimes it will still be the limiting factor on TCP performance. If you have ever wondered why your connection is transmitting at a fraction of the available bandwidth, even when you know that both the client and the server are capable of higher rates, then it is likely due to a small window size: a saturated peer advertising low receive window, bad network weather and high packet loss resetting the congestion window, or explicit traffic shaping that could have been applied to limit throughput of your connection.

TCP provides the abstraction of a reliable network running over an unreliable channel, which includes basic packet error checking and correction, in-order delivery, retransmission of lost packets, as well as flow control, congestion control, and congestion avoidance designed to operate the network at the point of greatest efficiency. Combined, these features make TCP the preferred transport for most applications.

However, while TCP is a popular choice, it is not the only, nor necessarily the best choice for every occasion. Specifically, some of the features, such as in-order and reliable packet delivery, are not always necessary and can introduce unnecessary delays and negative performance implications.

To understand why that is the case, recall that every TCP packet carries a unique sequence number when put on the wire, and the data must be passed to the receiver in-order (Figure 2-8). If one of the packets is lost en route to the receiver, then all subsequent packets must be held in the receiver’s TCP buffer until the lost packet is retransmitted and arrives at the receiver. Because this work is done within the TCP layer, our application has no visibility into the TCP retransmissions or the queued packet buffers, and must wait for the full sequence before it is able to access the data. Instead, it simply sees a delivery delay when it tries to read the data from the socket. This effect is known as TCP head-of-line (HOL) blocking.

The delay imposed by head-of-line blocking allows our applications to avoid having to deal with packet reordering and reassembly, which makes our application code much simpler. However, this is done at the cost of introducing unpredictable latency variation in the packet arrival times, commonly referred to as jitter, which can negatively impact the performance of the application.

Further, some applications may not even need either reliable delivery or in-order delivery: if every packet is a standalone message, then in-order delivery is strictly unnecessary, and if every message overrides all previous messages, then the requirement for reliable delivery can be removed entirely. Unfortunately, TCP does not provide such configuration—all packets are sequenced and delivered in order.

Applications that can deal with out-of-order delivery or packet loss and that are latency or jitter sensitive are likely better served with an alternate transport, such as UDP.

TCP is an adaptive protocol designed to be fair to all network peers and to make the most efficient use of the underlying network. Thus, the best way to optimize TCP is to tune how TCP senses the current network conditions and adapts its behavior based on the type and the requirements of the layers below and above it: wireless networks may need different congestion algorithms, and some applications may need custom quality of service (QoS) semantics to deliver the best experience.

The close interplay of the varying application requirements, and the many knobs in every TCP algorithm, make TCP tuning and optimization an inexhaustible area of academic and commercial research. In this chapter, we have only scratched the surface of the many factors that govern TCP performance. Additional mechanisms, such as selective acknowledgments (SACK), delayed acknowledgments, and fast retransmit, among many others, make each TCP session much more complicated (or interesting, depending on your perspective) to understand, analyze, and tune.

Having said that, while the specific details of each algorithm and feedback mechanism will continue to evolve, the core principles and their implications remain unchanged:

As a result, the rate with which a TCP connection can transfer data in modern high-speed networks is often limited by the roundtrip time between the receiver and sender. Further, while bandwidth continues to increase, latency is bounded by the speed of light and is already within a small constant factor of its maximum value. In most cases, latency, not bandwidth, is the bottleneck for TCP—e.g., see Figure 2-5.

As a starting point, prior to tuning any specific values for each buffer and timeout variable in TCP, of which there are dozens, you are much better off simply upgrading your hosts to their latest system versions. TCP best practices and underlying algorithms that govern its performance continue to evolve, and most of these changes are only available only in the latest kernels. In short, keep your servers up to date to ensure the optimal interaction between the sender’s and receiver’s TCP stacks.

On the surface, upgrading server kernel versions seems like trivial advice. However, in practice, it is often met with significant resistance: many existing servers are tuned for specific kernel versions, and system administrators are reluctant to perform the upgrade.

To be fair, every upgrade brings its risks, but to get the best TCP performance, it is also likely the single best investment you can make.

With the latest kernel in place, it is good practice to ensure that your server is configured to use the following best practices:

The combination of the preceding settings and the latest kernel will enable the best performance—lower latency and higher throughput—for individual TCP connections.

Depending on your application, you may also need to tune other TCP settings on the server to optimize for high connection rates, memory consumption, or similar criteria. However, these configuration settings are dependent on the platform, application, and hardware—consult your platform documentation as required.

Tuning performance of TCP allows the server and client to deliver the best throughput and latency for an individual connection. However, how an application uses each new, or established, TCP connection can have an even greater impact:

Eliminating unnecessary data transfers is, of course, the single best optimization—e.g., eliminating unnecessary resources or ensuring that the minimum number of bits is transferred by applying the appropriate compression algorithm. Following that, locating the bits closer to the client, by geo-distributing servers around the world—e.g., using a CDN—will help reduce latency of network roundtrips and significantly improve TCP performance. Finally, where possible, existing TCP connections should be reused to minimize overhead imposed by slow-start and other congestion mechanisms.

Optimizing TCP performance pays high dividends, regardless of the type of application, for every new connection to your servers. A short list to put on the agenda:

User Datagram Protocol, or UDP, was added to the core network protocol suite in August of 1980 by Jon Postel, well after the original introduction of TCP/IP, but right at the time when the TCP and IP specifications were being split to become two separate RFCs. This timing is important because, as we will see, the primary feature and appeal of UDP is not in what it introduces, but rather in all the features it chooses to omit. UDP is colloquially referred to as a null protocol, and RFC 768, which describes its operation, could indeed fit on a napkin.

The words datagram and packet are often used interchangeably, but there are some nuances. While the term “packet” applies to any formatted block of data, the term “datagram” is often reserved for packets delivered via an unreliable service—no delivery guarantees, no failure notifications. Because of this, you will frequently find the more descriptive term “Unreliable” substituted for the official term “User” in the UDP acronym, to form “Unreliable Datagram Protocol.” That is also why UDP packets are generally, and more correctly, referred to as datagrams.

Perhaps the most well-known use of UDP, and one that every browser and Internet application depends on, is the Domain Name System (DNS): given a human-friendly computer hostname, we need to discover its IP address before any data exchange can occur. However, even though the browser itself is dependent on UDP, historically the protocol has never been exposed as a first-class transport for pages and applications running within it. That is, until WebRTC entered into the picture.

The new Web Real-Time Communication (WebRTC) standards, jointly developed by the IETF and W3C working groups, are enabling real-time communication, such as voice and video calling and other forms of peer-to-peer (P2P) communication, natively within the browser via UDP. With WebRTC, UDP is now a first-class browser transport with a client-side API! We will investigate WebRTC in-depth in Chapter 18, but before we get there, let’s first explore the inner workings of the UDP protocol to understand why and where we may want to use it.

To understand UDP and why it is commonly referred to as a “null protocol,” we first need to look at the Internet Protocol (IP), which is located one layer below both TCP and UDP protocols.

The IP layer has the primary task of delivering datagrams from the source to the destination host based on their addresses. To do so, the messages are encapsulated within an IP packet (Figure 3-1) which identifies the source and the destination addresses, as well as a number of other routing parameters .

Once again, the word “datagram” is an important distinction: the IP layer provides no guarantees about message delivery or notifications of failure and hence directly exposes the unreliability of the underlying network to the layers above it. If a routing node along the way drops the IP packet due to congestion, high load, or for other reasons, then it is the responsibility of a protocol above IP to detect it, recover, and retransmit the data—that is, if that is the desired behavior!

The UDP protocol encapsulates user messages into its own packet structure (Figure 3-2), which adds only four additional fields: source port, destination port, length of packet, and checksum. Thus, when IP delivers the packet to the destination host, the host is able to unwrap the UDP packet, identify the target application by the destination port, and deliver the message. Nothing more, nothing less.

In fact, both the source port and the checksum fields are optional fields in UDP datagrams. The IP packet contains its own header checksum, and the application can choose to omit the UDP checksum, which means that all the error detection and error correction can be delegated to the applications above them. At its core, UDP simply provides “application multiplexing” on top of IP by embedding the source and the target application ports of the communicating hosts. With that in mind, we can now summarize all the UDP non-services:

TCP is a byte-stream oriented protocol capable of transmitting application messages spread across multiple packets without any explicit message boundaries within the packets themselves. To achieve this, connection state is allocated on both ends of the connection, and each packet is sequenced, retransmitted when lost, and delivered in order. UDP datagrams, on the other hand, have definitive boundaries: each datagram is carried in a single IP packet, and each application read yields the full message; datagrams cannot be fragmented.

UDP is a simple, stateless protocol, suitable for bootstrapping other application protocols on top: virtually all of the protocol design decisions are left to the application above it. However, before you run away to implement your own protocol to replace TCP, you should think carefully about complications such as UDP interaction with the many layers of deployed middleboxes (NAT traversal), as well as general network protocol design best practices. Without careful engineering and planning, it is not uncommon to start with a bright idea for a new protocol but end up with a poorly implemented version of TCP. The algorithms and the state machines in TCP have been honed and improved over decades and have taken into account dozens of mechanisms that are anything but easy to replicate well.

Unfortunately, IPv4 addresses are only 32 bits long, which provides a maximum of 4.29 billion unique IP addresses. The IP Network Address Translator (NAT) specification was introduced in mid-1994 (RFC 1631) as an interim solution to resolve the looming IPv4 address depletion problem—as the number of hosts on the Internet began to grow exponentially in the early ’90s, we could not expect to allocate a unique IP to every host.

The proposed IP reuse solution was to introduce NAT devices at the edge of the network, each of which would be responsible for maintaining a table mapping of local IP and port tuples to one or more globally unique (public) IP and port tuples (Figure 3-3). The local IP address space behind the translator could then be reused among many different networks, thus solving the address depletion problem.

Unfortunately, as it often happens, there is nothing more permanent than a temporary solution. Not only did the NAT devices resolve the immediate problem, but they also quickly became a ubiquitous component of many corporate and home proxies and routers, security appliances, firewalls, and dozens of other hardware and software devices. NAT middleboxes are no longer a temporary solution; rather, they have become an integral part of the Internet infrastructure.

The issue with NAT translation, at least as far as UDP is concerned, is precisely the routing table that it must maintain to deliver the data. NAT middleboxes rely on connection state, whereas UDP has none. This is a fundamental mismatch and a source of many problems for delivering UDP datagrams. Further, it is now not uncommon for a client to be behind many layers of NATs, which only complicates matters further.

Each TCP connection has a well-defined protocol state machine, which begins with a handshake, followed by application data transfer, and a well-defined exchange to close the connection. Given this flow, each middlebox can observe the state of the connection and create and remove the routing entries as needed. With UDP, there is no handshake or connection termination, and hence there is no connection state machine to monitor.

Delivering outbound UDP traffic does not require any extra work, but routing a reply requires that we have an entry in the translation table, which will tell us the IP and port of the local destination host. Thus, translators have to keep state about each UDP flow, which itself is stateless.

Even worse, the translator is also tasked with figuring out when to drop the translation record, but since UDP has no connection termination sequence, either peer could just stop transmitting datagrams at any point without notice. To address this, UDP routing records are expired on a timer. How often? There is no definitive answer; instead the timeout depends on the vendor, make, version, and configuration of the translator. Consequently, one of the de facto best practices for long-running sessions over UDP is to introduce bidirectional keepalive packets to periodically reset the timers for the translation records in all the NAT devices along the path.

Unpredictable connection state handling is a serious issue created by NATs, but an even larger problem for many applications is the inability to establish a UDP connection at all. This is especially true for P2P applications, such as VoIP, games, and file sharing, which often need to act as both client and server to enable two-way direct communication between the peers.

The first issue is that in the presence of a NAT, the internal client is unaware of its public IP: it knows its internal IP address, and the NAT devices perform the rewriting of the source port and address in every UDP packet, as well as the originating IP address within the IP packet. However, if the client communicates its private IP address as part of its application data with a peer outside of its private network, then the connection will inevitably fail. Hence, the promise of “transparent” translation is no longer true, and the application must first discover its public IP address if it needs to share it with a peer outside its private network.

However, knowing the public IP is also not sufficient to successfully transmit with UDP. Any packet that arrives at the public IP of a NAT device must also have a destination port and an entry in the NAT table that can translate it to an internal destination host IP and port tuple. If this entry does not exist, which is the most likely case if someone simply tries to transmit data from the public network, then the packet is simply dropped (Figure 3-4). The NAT device acts as a simple packet filter since it has no way to automatically determine the internal route, unless explicitly configured by the user through a port-forwarding or similar mechanism.

It is important to note that the preceding behavior is not an issue for client applications, which begin their interaction from the internal network and in the process establish the necessary translation records along the path. However, handling inbound connections (acting as a server) from P2P applications such as VoIP, game consoles, file sharing, and so on, in the presence of a NAT, is where we will immediately run into this problem.

To work around this mismatch in UDP and NATs, various traversal techniques (TURN, STUN, ICE) have to be used to establish end-to-end connectivity between the UDP peers on both sides.

Session Traversal Utilities for NAT (STUN) is a protocol (RFC 5389) that allows the host application to discover the presence of a network address translator on the network, and when present to obtain the allocated public IP and port tuple for the current connection (Figure 3-5). To do so, the protocol requires assistance from a well-known, third-party STUN server that must reside on the public network.

Assuming the IP address of the STUN server is known (through DNS discovery, or through a manually specified address), the application first sends a binding request to the STUN server. In turn, the STUN server replies with a response that contains the public IP address and port of the client as seen from the public network. This simple workflow addresses several problems we encountered in our earlier discussion:

With this mechanism in place, whenever two peers want to talk to each other over UDP, they will first send binding requests to their respective STUN servers, and following a successful response on both sides, they can then use the established public IP and port tuples to exchange data.

However, in practice, STUN is not sufficient to deal with all NAT topologies and network configurations. Further, unfortunately, in some cases UDP may be blocked altogether by a firewall or some other network appliance—not an uncommon scenario for many enterprise networks. To address this issue, whenever STUN fails, we can use the Traversal Using Relays around NAT (TURN) protocol (RFC 5766) as a fallback, which can run over UDP and switch to TCP if all else fails.

The key word in TURN is, of course, “relays.” The protocol relies on the presence and availability of a public relay (Figure 3-6) to shuttle the data between the peers.

Of course, the obvious downside in this exchange is that it is no longer peer-to-peer! TURN is the most reliable way to provide connectivity between any two peers on any networks, but it carries a very high cost of operating the TURN server—at the very least, the relay must have enough capacity to service all the data flows. As a result, TURN is best used as a last resort fallback for cases where direct connectivity fails.

Building an effective NAT traversal solution is not for the faint of heart. Thankfully, we can lean on Interactive Connectivity Establishment (ICE) protocol (RFC 5245) to help with this task. ICE is a protocol, and a set of methods, that seek to establish the most efficient tunnel between the participants (Figure 3-7): direct connection where possible, leveraging STUN negotiation where needed, and finally fallback to TURN if all else fails.

In practice, if you are building a P2P application over UDP, then you most definitely want to leverage an existing platform API, or a third-party library that implements ICE, STUN, and TURN for you. And now that you are familiar with what each of these protocols does, you can navigate your way through the required setup and configuration!

UDP is a simple and a commonly used protocol for bootstrapping new transport protocols. In fact, the primary feature of UDP is all the features it omits: no connection state, handshakes, retransmissions, reassembly, reordering, congestion control, congestion avoidance, flow control, or even optional error checking. However, the flexibility that this minimal message-oriented transport layer affords is also a liability for the implementer. Your application will likely have to reimplement some, or many, of these features from scratch, and each must be designed to play well with other peers and protocols on the network.

Unlike TCP, which ships with built-in flow and congestion control and congestion avoidance, UDP applications must implement these mechanisms on their own. Congestion insensitive UDP applications can easily overwhelm the network, which can lead to degraded network performance and, in severe cases, to network congestion collapse.

If you want to leverage UDP for your own application, make sure to research and read the current best practices and recommendations. One such document is the RFC 5405, which specifically focuses on design guidelines for applications delivered via unicast UDP. Here is a short sample of the recommendations:

Designing a new transport protocol requires a lot of careful thought, planning, and research—do your due diligence. Where possible, leverage an existing library or a framework that has already taken into account NAT traversal, and is able to establish some degree of fairness with other sources of concurrent network traffic.

On that note, good news: WebRTC is just such a framework!

The SSL protocol was originally developed at Netscape to enable ecommerce transaction security on the Web, which required encryption to protect customers’ personal data, as well as authentication and integrity guarantees to ensure a safe transaction. To achieve this, the SSL protocol was implemented at the application layer, directly on top of TCP (Figure 4-1), enabling protocols above it (HTTP, email, instant messaging, and many others) to operate unchanged while providing communication security when communicating across the network.

When SSL is used correctly, a third-party observer can only infer the connection endpoints, type of encryption, as well as the frequency and an approximate amount of data sent, but cannot read or modify any of the actual data.

When the SSL protocol was standardized by the IETF, it was renamed to Transport Layer Security (TLS). Many use the TLS and SSL names interchangeably, but technically, they are different, since each describes a different version of the protocol.

SSL 2.0 was the first publicly released version of the protocol, but it was quickly replaced by SSL 3.0 due to a number of discovered security flaws. Because the SSL protocol was proprietary to Netscape, the IETF formed an effort to standardize the protocol, resulting in RFC 2246, which became known as TLS 1.0 and is effectively an upgrade to SSL 3.0:

The differences between this protocol and SSL 3.0 are not dramatic, but they are significant to preclude interoperability between TLS 1.0 and SSL 3.0.

— The TLS Protocol RFC 2246

Since the publication of TLS 1.0 in January 1999, two new versions have been produced by the IETF working group to address found security flaws, as well as to extend the capabilities of the protocol: TLS 1.1 in April 2006 and TLS 1.2 in August 2008. Internally the SSL 3.0 implementation, as well as all subsequent TLS versions, are very similar, and many clients continue to support SSL 3.0 and TLS 1.0 to this day, although there are very good reasons to upgrade to newer versions to protect users from known attacks!

TLS was designed to operate on top of a reliable transport protocol such as TCP. However, it has also been adapted to run over datagram protocols such as UDP. The Datagram Transport Layer Security (DTLS) protocol, defined in RFC 6347, is based on the TLS protocol and is able to provide similar security guarantees while preserving the datagram delivery model.

The TLS protocol is designed to provide three essential services to all applications running above it: encryption, authentication, and data integrity. Technically, you are not required to use all three in every situation. You may decide to accept a certificate without validating its authenticity, but you should be well aware of the security risks and implications of doing so. In practice, a secure web application will leverage all three services.

In order to establish a cryptographically secure data channel, the connection peers must agree on which ciphersuites will be used and the keys used to encrypt the data. The TLS protocol specifies a well-defined handshake sequence to perform this exchange, which we will examine in detail in TLS Handshake. The ingenious part of this handshake, and the reason TLS works in practice, is its use of public key cryptography (also known as asymmetric key cryptography), which allows the peers to negotiate a shared secret key without having to establish any prior knowledge of each other, and to do so over an unencrypted channel.

As part of the TLS handshake, the protocol also allows both connection peers to authenticate their identity. When used in the browser, this authentication mechanism allows the client to verify that the server is who it claims to be (e.g., your bank) and not someone simply pretending to be the destination by spoofing its name or IP address. This verification is based on the established chain of trust; see Chain of Trust and Certificate Authorities). In addition, the server can also optionally verify the identity of the client—e.g., a company proxy server can authenticate all employees, each of whom could have his own unique certificate signed by the company.

Finally, with encryption and authentication in place, the TLS protocol also provides its own message framing mechanism and signs each message with a message authentication code (MAC). The MAC algorithm is a one-way cryptographic hash function (effectively a checksum), the keys to which are negotiated by both connection peers. Whenever a TLS record is sent, a MAC value is generated and appended for that message, and the receiver is then able to compute and verify the sent MAC value to ensure message integrity and authenticity.

Combined, all three mechanisms serve as a foundation for secure communication on the Web. All modern web browsers provide support for a variety of ciphersuites, are able to authenticate both the client and server, and transparently perform message integrity checks for every record.

Before the client and the server can begin exchanging application data over TLS, the encrypted tunnel must be negotiated: the client and the server must agree on the version of the TLS protocol, choose the ciphersuite, and verify certificates if necessary. Unfortunately, each of these steps requires new packet roundtrips (Figure 4-2) between the client and the server, which adds startup latency to all TLS connections.

Figure 4-2 assumes the same 28 millisecond one-way “light in fiber” delay between New York and London as used in previous TCP connection establishment examples; see Table 1-1.

|

|

TLS runs over a reliable transport (TCP), which means that we must first complete the TCP three-way handshake, which takes one full roundtrip. |

|

|

With the TCP connection in place, the client sends a number of specifications in plain text, such as the version of the TLS protocol it is running, the list of supported ciphersuites, and other TLS options it may want to use. |

|

|

The server picks the TLS protocol version for further communication, decides on a ciphersuite from the list provided by the client, attaches its certificate, and sends the response back to the client. Optionally, the server can also send a request for the client’s certificate and parameters for other TLS extensions. |

|

|

Assuming both sides are able to negotiate a common version and cipher, and the client is happy with the certificate provided by the server, the client initiates either the RSA or the Diffie-Hellman key exchange, which is used to establish the symmetric key for the ensuing session. |

|

|

The server processes the key exchange parameters sent by the client, checks message integrity by verifying the MAC, and returns an encrypted “Finished” message back to the client. |

|

|

The client decrypts the message with the negotiated symmetric key, verifies the MAC, and if all is well, then the tunnel is established and application data can now be sent. |

Negotiating a secure TLS tunnel is a complicated process, and there are many ways to get it wrong. The good news is all the work just shown will be done for us by the server and the browser, and all we need to do is provide and configure the certificates.