Table of Contents

System-Level Controls and Settings

Introduction to the Instruction Set

Functions and Function Invocation

Branching and Conditional Execution

Asynchronous and Ad-Hoc Execution

Chapter 4: Debugging and Automation

The Debugging Tools and Basic Commands

Scripting with the Debugging Tools

Useful Extensions, Tools, and Resources

A Survey of Obfuscation Techniques

A Survey of Deobfuscation Techniques

The x86 is little-endian architecture based on the Intel 8086 processor. For the purpose of our chapter, x86 is the 32-bit implementation of the Intel architecture (IA-32) as defined in the Intel Software Development Manual. Generally speaking, it can operate in two modes: real and protected. Real mode is the processor state when it is first powered on and only supports a 16-bit instruction set. Protected mode is the processor state supporting virtual memory, paging, and other features; it is the state in which modern operating systems execute. The 64-bit extension of the architecture is called x64 or x86-64. This chapter discusses the x86 architecture operating in protected mode.

x86 supports the concept of privilege separation through an abstraction called ring level. The processor supports four ring levels, numbered from 0 to 3. (Rings 1 and 2 are not commonly used so they are not discussed here.) Ring 0 is the highest privilege level and can modify all system settings. Ring 3 is the lowest privileged level and can only read/modify a subset of system settings. Hence, modern operating systems typically implement user/kernel privilege separation by having user-mode applications run in ring 3, and the kernel in ring 0. The ring level is encoded in the CS register and sometimes referred to as the current privilege level (CPL) in official documentation.

This chapter discusses the x86/IA-32 architecture as defined in the Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual, Volumes 1–3 (www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/processors/architectures-software-developer-manuals.html).

When operating in protected mode, the x86 architecture has eight 32-bit general-purpose registers (GPRs): EAX, EBX, ECX, EDX, EDI, ESI, EBP, and ESP. Some of them can be further divided into 8- and 16-bit registers. The instruction pointer is stored in the EIP register. The register set is illustrated in Figure 1.1. Table 1.1 describes some of these GPRs and how they are used.

Table 1.1 Some GPRs and Their Usage

| Register | Purpose |

| ECX | Counter in loops |

| ESI | Source in string/memory operations |

| EDI | Destination in string/memory operations |

| EBP | Base frame pointer |

| ESP | Stack pointer |

The common data types are as follows:

The 32-bit EFLAGS register is used to store the status of arithmetic operations and other execution states (e.g., trap flag). For example, if the previous “add” operation resulted in a zero, the ZF flag will be set to 1. The flags in EFLAGS are primarily used to implement conditional branching.

In addition to the GPRs, EIP, and EFLAGS, there are also registers that control important low-level system mechanisms such as virtual memory, interrupts, and debugging. For example, CR0 controls whether paging is on or off, CR2 contains the linear address that caused a page fault, CR3 is the base address of a paging data structure, and CR4 controls the hardware virtualization settings. DR0–DR7 are used to set memory breakpoints. We will come back to these registers later in the “System Mechanism” section.

There are also model-specific registers (MSRs). As the name implies, these registers may vary between different processors by Intel and AMD. Each MSR is identified by name and a 32-bit number, and read/written to through the RDMSR/WRMSR instructions. They are accessible only to code running in ring 0 and typically used to store special counters and implement low-level functionality. For example, the SYSENTER instruction transfers execution to the address stored in the IA32_SYSENTER_EIP MSR (0x176), which is usually the operating system's system call handler. MSRs are discussed throughout the book as they come up.

The x86 instruction set allows a high level of flexibility in terms of data movement between registers and memory. The movement can be classified into five general methods:

The first four methods are supported by all modern architectures, but the last one is specific to x86. A classical RISC architecture like ARM can only read/write data from/to memory with load/store instructions (LDR and STR, respectively); for example, a simple operation like incrementing a value in memory requires three instructions:

On x86, such an operation would require only one instruction (either INC or ADD) because it can directly access memory. The MOVS instruction can read and write memory at the same time.

ARM

01: 1B 68 LDR R3, [R3] ; read the value at address R3 02: 5A 1C ADDS R2, R3, #1 ; add 1 to it 03: 1A 60 STR R2, [R3] ; write updated value back to address R3

x86

01: FF 00 inc dword ptr [eax] ; directly increment value at address EAX

Another important characteristic is that x86 uses variable-length instruction size: the instruction length can range from 1 to 15 bytes. On ARM, instructions are either 2 or 4 bytes in length.

Depending on the assembler/disassembler, there are two syntax notations for x86 assembly code, Intel and AT&T:

Intel

mov ecx, AABBCCDDh mov ecx, [eax] mov ecx, eax

AT&T

movl $0xAABBCCDD, %ecx movl (%eax), %ecx movl %eax, %ecx

It is important to note that these are the same instructions but written differently. There are several differences between Intel and AT&T notation, but the most notable ones are as follows:

Disassemblers/assemblers and other reverse-engineering tools (IDA Pro, OllyDbg, MASM, etc.) on Windows typically use Intel notation, whereas those on UNIX frequently follow AT&T notation (GCC). In practice, Intel notation is the dominant form and is used throughout this book.

Instructions operate on values that come from registers or main memory. The most common instruction for moving data is MOV. The simplest usage is to move a register or immediate to register. For example:

01: BE 3F 00 0F 00 mov esi, 0F003Fh ; set ESI = 0xF003 02: 8B F1 mov esi, ecx ; set ESI = ECX

The next common usage is to move data to/from memory. Similar to other assembly language conventions, x86 uses square brackets ([]) to indicate memory access. (The only exception to this is the LEA instruction, which uses [] but does not actually reference memory.) Memory access can be specified in several different ways, so we will begin with the simplest case:

Assembly

01: C7 00 01 00 00+ mov dword ptr [eax], 1 ; set the memory at address EAX to 1 02: 8B 08 mov ecx, [eax] ; set ECX to the value at address EAX 03: 89 18 mov [eax], ebx ; set the memory at address EAX to EBX 04: 89 46 34 mov [esi+34h], eax ; set the memory address at (ESI+34) to EAX 05: 8B 46 34 mov eax, [esi+34h] ; set EAX to the value at address (EAX+34) 06: 8B 14 01 mov edx, [ecx+eax] ; set EDX to the value at address (ECX+EAX)

Pseudo C

01: *eax = 1; 02: ecx = *eax; 03: *eax = ebx; 04: *(esi+34) = eax; 05: eax = *(esi+34); 06: edx = *(ecx+eax);

These examples demonstrate memory access through a base register and offset, where offset can be a register or immediate. This form is commonly used to access structure members or data buffers at a location computed at runtime. For example, suppose that ECX points to a structure of type KDPC with the layout

kd> dt nt!_KDPC +0x000 Type : UChar +0x001 Importance : UChar +0x002 Number : Uint2B +0x004 DpcListEntry : _LIST_ENTRY +0x00c DeferredRoutine : Ptr32 void +0x010 DeferredContext : Ptr32 Void +0x014 SystemArgument1 : Ptr32 Void +0x018 SystemArgument2 : Ptr32 Void +0x01c DpcData : Ptr32 Void

and used in the following context:

Assembly

01: 8B 45 0C mov eax, [ebp+0Ch] 02: 83 61 1C 00 and dword ptr [ecx+1Ch], 0 03: 89 41 0C mov [ecx+0Ch], eax 04: 8B 45 10 mov eax, [ebp+10h] 05: C7 01 13 01 00+ mov dword ptr [ecx], 113h 06: 89 41 10 mov [ecx+10h], eax

Pseudo C

KDPC *p = …; p->DpcData = NULL; p->DeferredRoutine = …; *(int *)p = 0x113; p->DeferredContext = …;

Line 1 reads a value from memory and stores it in EAX. The DeferredRoutine field is set to this value in line 3. Line 2 clears the DpcData field by AND'ing it with 0. Line 4 reads another value from memory and stores it in EAX. The DeferredContext field is set to this value in line 6.

Line 5 writes the double-word value 0x113 to the base of the structure. Why does it write a double-word value at the base if the first field is only 1 byte in size? Wouldn't that implicitly set the Importance and Number fields as well? The answer is yes. Figure 1.2 shows the result of converting 0x113 to binary.

The Type field is set to 0x13 (bold bits), Importance is set to 0x1 (underlined bits), and Number is set to 0x0 (the remaining bits). By writing one value, the code managed to initialize three fields with a single instruction! The code could have been written as follows:

01: 8B 45 0C mov eax, [ebp+0Ch] 02: 83 61 1C 00 and dword ptr [ecx+1Ch], 0 03: 89 41 0C mov [ecx+0Ch], eax 04: 8B 45 10 mov eax, [ebp+10h] 05: C6 01 13 mov byte ptr [ecx],13h 06: C6 41 01 01 mov byte ptr [ecx+1],1 07: 66 C7 41 02 00+ mov word ptr [ecx+2],0 08: 89 41 10 mov [ecx+10h], eax

The compiler decided to fold three instructions into one because it knew the constants ahead of time and wants to save space. The three-instruction version occupies 13 bytes (the extra byte in line 7 is not shown), whereas the one-instruction version occupies 6 bytes. Another interesting observation is that memory access can be done at three granularity levels: byte (line 5–6), word (line 6), and double-word (line 1–4, 8). The default granularity is 4 bytes, which can be changed to 1 or 2 bytes with an override prefix. In the example, the override prefix bytes are C6 and 66 (italicized). Other prefixes are discussed as they come up.

The next memory access form is commonly used to access array-type objects. Generally, the format is as follows: [Base + Index * scale]. This is best understood through examples:

01: 8B 34 B5 40 05+ mov esi, _KdLogBuffer[esi*4] ; always written as mov esi, [_KdLogBuffer + esi * 4] ; _KdLogBuffer is the base address of a global array and ; ESI is the index; we know that each element in the array ; is 4 bytes in length (hence the scaling factor) 02: 89 04 F7 mov [edi+esi*8], eax ; here is EDI is the array base address; ESI is the array ; index; element size is 8.

In practice, this is observed in code looping over an array. For example:

01: loop_start: 02: 8B 47 04 mov eax, [edi+4] 03: 8B 04 98 mov eax, [eax+ebx*4] 04: 85 C0 test eax, eax … 05: 74 14 jz short loc_7F627F 06: loc_7F627F: 07: 43 inc ebx 08: 3B 1F cmp ebx, [edi] 09: 7C DD jl short loop_start

Line 2 reads a double-word from offset +4 from EDI and then uses it as the base address into an array in line 3; hence, you know that EDI is likely a structure that has an array at +4. Line 7 increments the index. Line 8 compares the index against a value at offset +0 in the same structure. Given this info, this small loop can be decompiled as follows:

typedef struct _FOO

{

DWORD size; // +0x00

DWORD array[…]; // +0x04

} FOO, *PFOO;

PFOO bar = …;

for (i = …; i < bar->size; i++) {

if (bar->array[i] != 0) {

…

}

}

The MOVSB/MOVSW/MOVSD instructions move data with 1-, 2-, or 4-byte granularity between two memory addresses. They implicitly use EDI/ESI as the destination/source address, respectively. In addition, they also automatically update the source/destination address depending on the direction flag (DF) flag in EFLAGS. If DF is 0, the addresses are decremented; otherwise, they are incremented. These instructions are typically used to implement string or memory copy functions when the length is known at compile time. In some cases, they are accompanied by the REP prefix, which repeats an instruction up to ECX times. Consider the following example:

Assembly

01: BE 28 B5 41 00 mov esi, offset _RamdiskBootDiskGuid ; ESI = pointer to RamdiskBootDiskGuid 02: 8D BD 40 FF FF+ lea edi, [ebp-0C0h] ; EDI is an address somewhere on the stack 03: A5 movsd ; copies 4 bytes from EDI to ESI; increment each by 4 04: A5 movsd ; same as above 05: A5 movsd ; save as above 06: A5 movsd ; same as above

Pseudo C

/* a GUID is 16-byte structure */ GUID RamDiskBootDiskGuid = …; // global … GUID foo; memcpy(&foo, &RamdiskBootDiskGuid, sizeof(GUID));

Line 2 deserves some special attention. Although the LEA instruction uses [], it actually does not read from a memory address; it simply evaluates the expression in square brackets and puts the result in the destination register. For example, if EBP were 0x1000, then EDI would be 0xF40 (=0x1000 – 0xC0) after executing line 2. The point is that LEA does not access memory, despite the misleading syntax.

The following example, from nt!KiInitSystem, uses the REP prefix:

01: 6A 08 push 8 ; push 8 on the stack (will explain stacks

; later)

02: …

03: 59 pop ecx ; pop the stack. Basically sets ECX to 8.

04: …

05: BE 00 44 61 00 mov esi, offset _KeServiceDescriptorTable

06: BF C0 43 61 00 mov edi, offset _KeServiceDescriptorTableShadow

07: F3 A5 rep movsd ; copy 32 bytes (movsd repeated 8 times)

; from this we can deduce that whatever these two objects are, they are

; likely to be 32 bytes in size.

The rough C equivalent of this would be as follows:

memcpy(&KeServiceDescriptorTableShadow, &KeServiceDescriptorTable, 32);

The final example, nt!MmInitializeProcessAddressSpace, uses a combination of these instructions because the copy size is not a multiple of 4:

01: 8D B0 70 01 00+ lea esi, [eax+170h] ; EAX is likely the base address of a structure. Remember what we said ; about LEA … 02: 8D BB 70 01 00+ lea edi, [ebx+170h] ; EBX is likely to be base address of another structure of the same type 03: A5 movsd 04: A5 movsd 05: A5 movsd 06: 66 A5 movsw 07: A4 movsb

After lines 1–2, you know that EAX and EBX are likely to be of the same type because they are being used as source/destination and the offset is identical. This code snippet simply copies 15 bytes from one structure field to another. Note that the code could also have been written using the MOVSB instruction with a REP prefix and ECX set to 15; however, that would be inefficient because it results in 15 reads instead of only five.

Another class of data movement instructions with implicit source and destination includes the SCAS and STOS instructions. Similar to MOVS, these instructions can operate at 1-, 2-, or 4-byte granularity. SCAS implicitly compares AL/AX/EAX with data starting at the memory address EDI; EDI is automatically incremented/decremented depending on the DF bit in EFLAGS. Given its semantic, SCAS is commonly used along with the REP prefix to find a byte, word, or double-word in a buffer. For example, the C strlen() function can be implemented as follows:

01: 30 C0 xor al, al ; set AL to 0 (NUL byte). You will frequently observe the XOR reg, reg ; pattern in code. 02: 89 FB mov ebx, edi ; save the original pointer to the string 03: F2 AE repne scasb ; repeatedly scan forward one byte at a time as long as AL does not match the ; byte at EDI when this instruction ends, it means we reached the NUL byte in ; the string buffer 04: 29 DF sub edi, ebx ; edi is now the NUL byte location. Subtract that from the original pointer ; to the length.

STOS is the same as SCAS except that it writes the value AL/AX/EAX to EDI. It is commonly used to initialize a buffer to a constant value (such as memset()). Here is an example:

01: 33 C0 xor eax, eax ; set EAX to 0 02: 6A 09 push 9 ; push 9 on the stack 03: 59 pop ecx ; pop it back in ECX. Now ECX = 9. 04: 8B FE mov edi, esi ; set the destination address 05: F3 AB rep stosd ; write 36 bytes of zero to the destination buffer (STOSD repeated 9 times) ; this is equivalent lent to memset(edi, 0, 36)

LODS is another instruction from the same family. It reads a 1-, 2-, or 4-byte value from ESI and stores it in AL, AX, or EAX.

01: 8B 7D 08 mov edi, [ebp+8] 02: 8B D7 mov edx, edi 03: 33 C0 xor eax, eax 04: 83 C9 FF or ecx, 0FFFFFFFFh 05: F2 AE repne scasb 06: 83 C1 02 add ecx, 2 07: F7 D9 neg ecx 08: 8A 45 0C mov al, [ebp+0Ch] 09: 8B FA mov edi, edx 10: F3 AA rep stosb 11: 8B C2 mov eax, edx

Fundamental arithmetic operations such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division are natively supported by the instruction set. Bit-level operations such as AND, OR, XOR, NOT, and left and right shift also have native corresponding instructions. With the exception of multiplication and division, the remaining instructions are straightforward in terms of usage. These operations are explained with the following examples:

01: 83 C4 14 add esp, 14h ; esp = esp + 0x14 02: 2B C8 sub ecx, eax ; ecx = ecx - eax 03: 83 EC 0C sub esp, 0Ch ; esp = esp - 0xC 04: 41 inc ecx ; ecx = ecx + 1 05: 4F dec edi ; edi = edi - 1 06: 83 C8 FF or eax, 0FFFFFFFFh ; eax = eax | 0xFFFFFFFF 07: 83 E1 07 and ecx, 7 ; ecx = ecx & 7 08: 33 C0 xor eax, eax ; eax = eax ^ eax 09: F7 D7 not edi ; edi = ∼edi 10: C0 E1 04 shl cl, 4 ; cl = cl << 4 11: D1 E9 shr ecx, 1 ; ecx = ecx >> 1 12: C0 C0 03 rol al, 3 ; rotate AL left 3 positions 13: D0 C8 ror al, 1 ; rotate AL right 1 position

The left and right shift instructions (lines 11–12) merit some explanation, as they are frequently observed in real-life code. These instructions are typically used to optimize multiplication and division operations where the multiplicand and divisor are a power of two. This type of optimization is sometimes known as strength reduction because it replaces a computationally expensive operation with a cheaper one. For example, integer division is relatively a slow operation, but when the divisor is a power of two, it can be reduced to shifting bits to the right; 100/2 is the same as 100 1. Similarly, multiplication by a power of two can be reduced to shifting bits to the left; 100*2 is the same as 100

1. Similarly, multiplication by a power of two can be reduced to shifting bits to the left; 100*2 is the same as 100 1.

1.

Unsigned and signed multiplication is done through the MUL and IMUL instructions, respectively. The MUL instruction has the following general form: MUL reg/memory. That is, it can only operate on register or memory values. The register is multiplied with AL, AX, or EAX and the result is stored in AX, DX:AX, or EDX:EAX, depending on the operand width. For example:

01: F7 E1 mul ecx ; EDX:EAX = EAX * ECX 02: F7 66 04 mul dword ptr [esi+4] ; EDX:EAX = EAX * dword_at(ESI+4) 03: F6 E1 mul cl ; AX = AL * CL 04: 66 F7 E2 mul dx ; DX:AX = AX * DX

Consider a few other concrete examples:

01: B8 03 00 00 00 mov eax,3 ; set EAX=3

02: B9 22 22 22 22 mov ecx,22222222h ; set ECX=0x22222222

03: F7 E1 mul ecx ; EDX:EAX = 3 * 0x22222222 =

; 0x66666666

; hence, EDX=0, EAX=0x66666666

04: B8 03 00 00 00 mov eax,3 ; set EAX=3

05: B9 00 00 00 80 mov ecx,80000000h ; set ECX=0x80000000

06: F7 E1 mul ecx ; EDX:EAX = 3 * 0x80000000 =

; 0x180000000

; hence, EDX=1, EAX=0x80000000

The reason why the result is stored in EDX:EAX for 32-bit multiplication is because the result potentially may not fit in one 32-bit register (as demonstrated in lines 4–6).

IMUL has three forms:

Some disassemblers shorten the parameters. For example:

01: F7 E9 imul ecx ; EDX:EAX = EAX * ECX 02: 69 F6 A0 01 00+ imul esi, 1A0h ; ESI = ESI * 0x1A0 03: 0F AF CE imul ecx, esi ; ECX = ECX * ESI

Unsigned and signed division is done through the DIV and IDIV instructions, respectively. They take only one parameter (divisor) and have the following form: DIV/IDIV reg/mem. Depending on the divisor's size, DIV will use either AX, DX:AX, or EDX:EAX as the dividend, and the resulting quotient/remainder pair are stored in AL/AH, AX/DX, or EAX/EDX. For example:

01: F7 F1 div ecx ; EDX:EAX / ECX, quotient in EAX,

02: F6 F1 div cl ; AX / CL, quotient in AL, remainder in AH

03: F7 76 24 div dword ptr [esi+24h] ; see line 1

04: B1 02 mov cl,2 ; set CL = 2

05: B8 0A 00 00 00 mov eax,0Ah ; set EAX = 0xA

06: F6 F1 div cl ; AX/CL = A/2 = 5 in AL (quotient),

; AH = 0 (remainder)

07: B1 02 mov cl,2 ; set CL = 2

08: B8 09 00 00 00 mov eax,09h ; set EAX = 0x9

09: F6 F1 div cl ; AX/CL = 9/2 = 4 in AL (quotient),

; AH = 1 (remainder)

The stack is a fundamental data structure in programming languages and operating systems. For example, local variables in C are stored on the functions' stack space. When the operating system transitions from ring 3 to ring 0, it saves state information on the stack. Conceptually, a stack is a last-in first-out data structure supporting two operations: push and pop. Push means to put something on top of the stack; pop means to remove an item from the top. Concretely speaking, on x86, a stack is a contiguous memory region pointed to by ESP and it grows downwards. Push/pop operations are done through the PUSH/POP instructions and they implicitly modify ESP. The PUSH instruction decrements ESP and then writes data at the location pointed to by ESP; POP reads the data and increments ESP. The default auto-increment/decrement value is 4, but it can be changed to 1 or 2 with a prefix override. In practice, the value is almost always 4 because the OS requires the stack to be double-word aligned.

Suppose that ESP initially points to 0xb20000 and you have the following code:

; initial ESP = 0xb20000 01: B8 AA AA AA AA mov eax,0AAAAAAAAh 02: BB BB BB BB BB mov ebx,0BBBBBBBBh 03: B9 CC CC CC CC mov ecx,0CCCCCCCCh 04: BA DD DD DD DD mov edx,0DDDDDDDDh 05: 50 push eax ; address 0xb1fffc will contain the value 0xAAAAAAAA and ESP ; will be 0xb1fffc (=0xb20000-4) 06: 53 push ebx ; address 0xb1fff8 will contain the value 0xBBBBBBBB and ESP ; will be 0xb1fff8 (=0xb1fffc-4) 07: 5E pop esi ; ESI will contain the value 0xBBBBBBBB and ESP will be 0xb1fffc ; (=0xb1fff8+4) 08: 5F pop edi ; EDI will contain the value 0xAAAAAAAA and ESP will be 0xb20000 ; (=0xb1fffc+4)

Figure 1.3 illustrates the stack layout.

ESP can also be directly modified by other instructions, such as ADD and SUB.

While high-level programming languages have the concept of functions that can be called and returned from, the processor does not provide such abstraction. At the lowest level, the processor operates only on concrete objects, such as registers or data coming from memory. How are functions translated at the machine level? They are implemented through the stack data structure! Consider the following function:

C

int

__cdecl addme(short a, short b)

{

return a+b;

}

Assembly

01: 004113A0 55 push ebp 02: 004113A1 8B EC mov ebp, esp 03: … 04: 004113BE 0F BF 45 08 movsx eax, word ptr [ebp+8] 05: 004113C2 0F BF 4D 0C movsx ecx, word ptr [ebp+0Ch] 06: 004113C6 03 C1 add eax, ecx 07: … 08: 004113CB 8B E5 mov esp, ebp 09: 004113CD 5D pop ebp 10: 004113CE C3 retn

The function is invoked with the following code:

C

sum = addme(x, y);

Assembly

01: 004129F3 50 push eax 02: … 03: 004129F8 51 push ecx 04: 004129F9 E8 F1 E7 FF FF call addme 05: 004129FE 83 C4 08 add esp, 8

Before going into the details, first consider the CALL/RET instructions and calling conventions. The CALL instruction performs two operations:

RET simply pops the address stored on the top of the stack into EIP and transfers control to it (literally like a “POP EIP” but such instruction sequence does not exist on x86). For example, if you want to begin execution at 0x12345678, you can just do the following:

01: 68 78 56 34 12 push 0x12345678 02: C3 ret

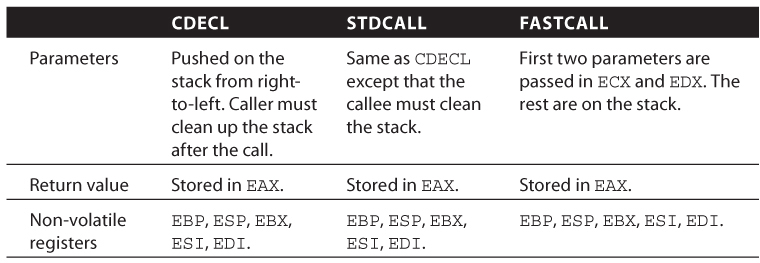

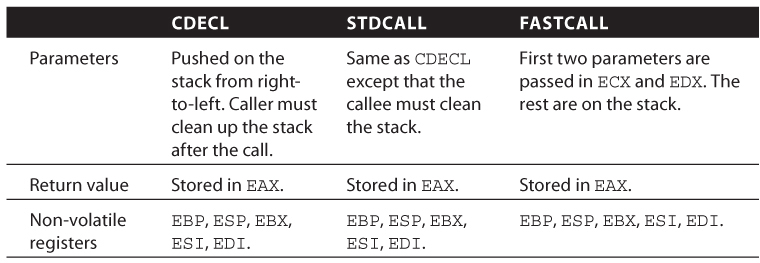

A calling convention is a set of rules dictating how function calls work at the machine level. It is defined by the Application Binary Interface (ABI) for a particular system. For example, should the parameters be passed through the stack, in registers, or both? Should the parameters be passed in from left-to-right or right-to-left? Should the return value be stored on the stack, in registers, or both? There are many calling conventions, but the popular ones are CDECL, STDCALL, THISCALL, and FASTCALL. (The compiler can also generate its own custom calling convention, but those will not be discussed here.) Table 1.2 summarizes their semantic.

Table 1.2 Calling Conventions

We now return to the code snippet to discuss how the function addme is invoked. In line 1 and 3, the two parameters are pushed on the stack; ECX and EAX are the first and second parameter, respectively. Line 4 invokes the addme function with the CALL instruction. This immediately pushes the return address, 0x4129FE, on the stack and begins execution at 0x4113A0. Figure 1.4 illustrates the stack layout after line 4 is executed.

After line 4 executes, we are now in the addme function body. Line 1 pushes EBP on the stack. Line 2 sets EBP to the current stack pointer. This two-instruction sequence is typically known as the function prologue because it establishes a new function frame. Line 4 reads the value at address EBP+8, which is the first parameter on the stack; line 5 reads the second parameter. Note that the parameters are accessed using EBP as the base register. When used in this context, EBP is known as the base frame pointer (see line 2) because it points to the stack frame for the current function, and parameters/locals can be accessed relative to it. The compiler can also be instructed to generate code that does not use EBP as the base frame pointer through an optimization called frame pointer omission. With such optimization, access to local variables and parameters is done relative to ESP, and EBP can be used as a general register like EAX, EBX, ECX, and so on. Line 6 adds the numbers and saves the result in EAX. Line 8 sets the stack pointer to the base frame pointer. Line 9 pops the saved EBP from line 1 into EBP. This two-instruction sequence is commonly referred to as the function epilogue because it is at the end of the function and restores the previous function frame. At this point, the top of the stack contains the return address saved by the CALL instruction at 0x4129F9. Line 10 performs a RET, which pops the stack and resumes execution at 0x4129FE. Line 5 in the snippet shrinks the stack by 8 because the caller must clean up the stack per CDECL's calling convention.

If the function addme had local variables, the code would need to grow the stack by subtracting ESP after line 2. All local variables would then be accessible through a negative offset from EBP.

This section describes how the system implements conditional execution for higher-level constructs like if/else, switch/case, and while/for. All of these are implemented through the CMP, TEST, JMP, and Jcc instructions and EFLAGS register. The following list summarizes the common flags in EFLAGS:

Arithmetic instructions update these flags based on the result. For example, the instruction SUB EAX, EAX would cause ZF to be set. The Jcc instructions, where “cc” is a conditional code, changes control flow depending on these flags. There can be up to 16 conditional codes, but the most common ones are described in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3 Common Conditional Codes

| Conditional Code | English Description | Machine Description |

| B/NAE | Below/Neither Above nor Equal. Used for unsigned operations. | CF=1 |

| NB/AE | Not Below/Above or Equal. Used for unsigned operations. | CF=0 |

| E/Z | Equal/Zero | ZF=1 |

| NE/NZ | Not Equal/Not Zero | ZF=0 |

| L | Less than/Neither Greater nor Equal. Used for signed operations. | (SF ^ OF) = 1 |

| GE/NL | Greater or Equal/Not Less than. Used for signed operations. | (SF ^ OF) = 0 |

| G/NLE | Greater/Not Less nor Equal. Used for signed operations. | ((SF ^ OF) | ZF) = 0 |

Because assembly language does not have a defined type system, one of the few ways to recognize signed/unsigned types is through these conditional codes.

The CMP instruction compares two operands and sets the appropriate conditional code in EFLAGS; it compares two numbers by subtracting one from another without updating the result. The TEST instruction does the same thing except it performs a logical AND between the two operands.

If-else constructs are quite simple to recognize because they involve a compare/test followed by a Jcc. For example:

Assembly

01: mov esi, [ebp+8] 02: mov edx, [esi] 03: test edx, edx 04: jz short loc_4E31F9 05: mov ecx, offset _FsRtlFastMutexLookasideList 06: call _ExFreeToNPagedLookasideList@8 07: and dword ptr [esi], 0 08: lea eax, [esi+4] 09: push eax 10: call _FsRtlUninitializeBaseMcb@4 11: loc_4E31F9: 12: pop esi 13: pop ebp 14: retn 4 15: _FsRtlUninitializeLargeMcb@4 endp

Pseudo C

if (*esi == 0) {

return;

}

ExFreeToNPagedLookasideList(…);

*esi = 0;

…

return;

OR

if (*esi != 0) {

…

ExFreeToNPagedLookasideList(…);

*esi = 0;

…

}

return;

Line 2 reads a value at location ESI and stores it in EDX. Line 3 ANDs EDX with itself and sets the appropriate flags in EFLAGS. Note that this pattern is commonly used to determine whether a register is zero. Line 4 jumps to loc_4E31F9 (line 12) if ZF=1. If ZF=0, then it executes line 5 and continues until the function returns.

Note that there are two slightly different but logically equivalent C translations for this snippet.

A switch-case block is a sequence of if/else statements. For example:

Switch-Case

switch(ch) {

case 'c':

handle_C();

break;

case 'h':

handle_H();

break;

default:

break;

}

domore();

…

If-Else

if (ch == 'c') {

handle_C();

} else

if (ch == 'h') {

handle_H();

}

domore();

…

Hence, the machine code translation will be a series if/else. The following simple example illustrates the idea:

Assembly

01: push ebp 02: mov ebp, esp 03: mov eax, [ebp+8] 04: sub eax, 41h 05: jz short loc_caseA 06: dec eax 07: jz short loc_caseB 08: dec eax 09: jz short loc_caseC 10: mov al, 5Ah 11: movzx eax, al 12: pop ebp 13: retn 14: loc_caseC: 15: mov al, 43h 16: movzx eax, al 17: pop ebp 18: retn 19: loc_caseB: 20: mov al, 42h 21: movzx eax, al 22: pop ebp 23: retn 24: loc_caseA: 25: mov al, 41h 26: movzx eax, al 27: pop ebp 28: retn

C

unsigned char switchme(int a)

{

unsigned char res;

switch(a) {

case 0x41:

res = 'A';

break;

case 0x42:

res = 'B';

break;

case 0x43:

res = 'C';

break;

default:

res = 'Z';

break;

}

return res;

}

Real-life switch-case statements can be more complex, and compilers commonly build a jump table to reduce the number of comparisons and conditional jumps. The jump table is essentially an array of addresses, each pointing to the handler for a specific case. This pattern can be observed in Sample J in sub_10001110:

Assembly

01: cmp edi, 5 02: ja short loc_10001141 03: jmp ds:off_100011A4[edi*4] 04: loc_10001125: 05: mov esi, 40h 06: jmp short loc_10001145 07: loc_1000112C: 08: mov esi, 20h 09: jmp short loc_10001145 10: loc_10001133: 11: mov esi, 38h 12: jmp short loc_10001145 13: loc_1000113A: 14: mov esi, 30h 15: jmp short loc_10001145 16: loc_10001141: 17: mov esi, [esp+0Ch] 18: … 19: off_100011A4 dd offset loc_10001125 20: dd offset loc_10001125 21: dd offset loc_1000113A 22: dd offset loc_1000112C 23: dd offset loc_10001133 24: dd offset loc_1000113A

Pseudo C

switch(edi) {

case 0:

case 1:

// goto loc_10001125;

esi = 0x40;

break;

case 2:

case 5:

// goto loc_1000113A;

esi = 0x30;

break;

case 3:

// goto loc_1000112C;

esi = 0x20;

break;

case 4:

// goto loc_10001133;

esi = 0x38;

break;

default:

// goto loc_10001141;

esi = *(esp+0xC)

break;

}

…

Here, the compiler knows that there are only five cases and the case value is consecutive; hence, it can construct the jump table and index into it directly (line 3). Without the jump table, there would be 10 additional instructions to test each case and branch to the handler. (There are other forms of switch/case optimizations, but we will not cover them here.)

At the machine level, loops are implemented using a combination of Jcc and JMP instructions. In other words, they are implemented using if/else and goto constructs. The best way to understand this is to rewrite a loop using only if/else and goto. Consider the following example:

Using for

for (int i=0; i<10; i++) {

printf("%d\n", i);

}

printf("done!\n");

Using if/else and goto

int i = 0;

loop_start:

if (i < 10) {

printf("%d\n", i);

i++;

goto loop_start;

}

printf("done!n");

When compiled, both versions are identical at the machine-code level:

01: 00401002 mov edi, ds:__imp__printf 02: 00401008 xor esi, esi 03: 0040100A lea ebx, [ebx+0] 04: 00401010 loc_401010: 05: 00401010 push esi 06: 00401011 push offset Format ; "%d\n" 07: 00401016 call edi ; __imp__printf 08: 00401018 inc esi 09: 00401019 add esp, 8 10: 0040101C cmp esi, 0Ah 11: 0040101F jl short loc_401010 12: 00401021 push offset aDone ; "done!\n" 13: 00401026 call edi ; __imp__printf 14: 00401028 add esp, 4

Line 1 sets EDI to the printf function. Line 2 sets ESI to 0. Line 4 begins the loop; however, note that it does not begin with a comparison. There is no comparison here because the compiler knows that the counter was initialized to 0 (see line 2) and is obviously going to be less than 10 so it skips the check. Lines 5–7 call the printf function with the right parameters (format specifier and our number). Line 8 increments the number. Line 9 cleans up the stack because printf uses the CDECL calling convention. Line 10 checks to see if the counter is less than 0xA. If it is, it jumps back to loc_401010. If the counter is not less than 0xA, it continues execution at line 12 and finishes with a printf.

One important observation to make is that the disassembly allowed us to infer that the counter is a signed integer. Line 11 uses the “less than” conditional code (JL), so we immediately know that the comparison was done on signed integers. Remember: If “above/below,” it is unsigned; if “less than/greater than,” it is signed. Sample L has a small function, sub_1000AE3B, with the following interesting loop:

Assembly

01: sub_1000AE3B proc near 02: push edi 03: push esi 04: call ds:lstrlenA 05: mov edi, eax 06: xor ecx, ecx 07: xor edx, edx 08: test edi, edi 09: jle short loc_1000AE5B 10: loc_1000AE4D: 11: mov al, [edx+esi] 12: mov [ecx+esi], al 13: add edx, 3 14: inc ecx 15: cmp edx, edi 16: jl short loc_1000AE4D 17: loc_1000AE5B: 18: mov byte ptr [ecx+esi], 0 19: mov eax, esi 20: pop edi 21: retn 22: sub_1000AE3B endp

C

char *sub_1000AE3B (char *str)

{

int len, i=0, j=0;

len = lstrlenA(str);

if (len <= 0) {

str[j] = 0;

return str;

}

while (j < len) {

str[i] = str[j];

j = j+3;

i = i+1;

}

str[i] = 0;

return str;

}

The sub_1000AE3B function has one parameter passed using a custom calling convention (ESI holds the parameter). Line 2 saves EDI. Line 3 calls lstrlenA with the parameter; hence, you immediately know that ESI is of type char *. Line 5 saves the return value (string length) in EDI. Lines 6–7 clear ECX and EDX. Lines 8–9 check to see if the string length is less than or equal to zero. If it is, control is transferred to line 18, which sets the value at ECX+ESI to 0. If it is not, then execution is continued at line 11, which is the start of a loop. First, it reads the character at ESI+EDX (line 11), and then it stores it at ESI+ECX (line 12). Next, it increments the EDX and ECX by three and one, respectively. Lines 15–16 check to see if EDX is less than the string length; if so, execution goes back to the loop start. If not, execution is continued at line 18.

It may seem convoluted at first, but this function takes an obfuscated string whose deobfuscated value is every third character. For example, the string SX]OTYFKPTY^W\\aAFKRW\\E is actually SOFTWARE. The purpose of this function is to prevent naïve string scanners and evade detection. As an exercise, you should decompile this function so that it looks more “natural” (as opposed to our literal translation).

Outside of the normal Jcc constructs, certain loops can be implemented using the LOOP instruction. The LOOP instruction executes a block of code up to ECX time. For example:

Assembly

01: 8B CA mov ecx, edx 02: loc_CFB8F: 03: AD lodsd 04: F7 D0 not eax 05: AB stosd 06: E2 FA loop loc_CFB8F

Rough C

while (ecx != 0) {

eax = *edi;

edi++;

*esi = ∼eax;

esi++;

ecx--;

}

Line 1 reads the counter from EDX. Line 3 is the loop start; it reads in a double-word at the memory address EDI and saves that in EAX; it also increments EDI by 4. Line 4 performs the NOT operator on the value just read. Line 5 writes the modified value to the memory address ESI and increments ESI by 4. Line 6 checks to see if ECX is 0; if not, execution is continued at the loop start.

The previous sections explain mechanisms and instructions that are available to code running at all privilege levels. To get a better appreciation of the architecture, this section discusses two fundamental system-level mechanisms: virtual address translation and exception/interrupt handling. You may skip this section on a first read.

The physical memory on a computer system is divided into 4KB units called pages. (A page can be more than 4KB, but we will not discuss the other sizes here.) Memory addresses are divided into two categories: virtual and physical. Virtual addresses are those used by instructions executed in the processor when paging is enabled. For example:

01: A1 78 56 34 12 mov eax, [0x12345678]; read memory at the virtual

; address 0x12345678

01: 89 08 mov [eax], ecx ; write ECX at the virtual

; address EAX

Physical addresses are the actual memory locations used by the processor when accessing memory. The processor's memory management unit (MMU) transparently translates every virtual address into a physical address before accessing it. While a virtual address may seem like just another number to the user, there is a structure to it when viewed by the MMU. On x86 systems with physical address extension (PAE) support, a virtual memory address can be divided into indices into three tables and offset: page directory pointer table (PDPT), page directory (PD), page table (PT), and page table entry (PTE). A PDPT is an array of four 8-byte elements, each pointing to a PD. A PD is an array of 512 8-byte elements, each pointing to a PT. A PT is an array of 512 8-byte elements each containing a PTE. For example, the virtual address 0xBF80EE6B can be understood as shown in Figure 1.5.

The 8-byte elements in these tables contain data about the tables, memory permission, and other memory characteristics. For example, there are bits that determine whether the page is read-only or readable/writable, executable or non-executable, accessible by user or not, and so on.

The address translation process revolves around these three tables and the CR3 register. CR3 holds the physical base address of the PDPT. The rest of this section walks through the translation of the virtual address 0xBF80EE6B on a real system (refer to Figure 1.5):

kd> r @cr3 ; CR3 is the physical address for the base of a PDPT cr3=085c01e0 kd> !dq @cr3+2*8 L1 ; read the PDPT entry at index 2 # 85c01f0 00000000`0d66e001

Per the documentation, the bottom 12 bits of a PDPT entry are flags/reserved bits, and the remaining ones are used as the physical address of the PD base. Bit 63 is the NX flag in PAE, so you will also need to clear that as well. In this particular example, we did not clear it because it is already 0. (We are looking at code pages that are executable.)

; 0x00000000`0d66e001 = 00001101 01100110 11100000 00000001 ; after clearing the bottom 12 bits, we have ; 0x0d66e000 = 00001101 01100110 11100000 00000000 ; This tells us that the PD base is at physical address 0x0d66e000 kd> !dq 0d66e000+0x1fc*8 L1 ; read the PD entry at index 0x1FC # d66efe0 00000000`0964b063

Again, per the documentation, the bottom 12 bits of a PD entry are used for flags/reserved bits, and the remaining ones are used as the base for the PT:

; 0x0964b063 = 00001001 01100100 10110000 01100011 ; after clearing the bottom 12 bits, we get ; 0x0964b000 = 00001001 01100100 10110000 00000000 ; This tells us that the PT base is at 0x0964b000 kd> !dq 0964b000+e*8 L1 ; read the PT entry at index 0xE # 964b070 00000000`06694021

Again, the bottom 12 bits can be cleared to get to the base of a page entry:

; 0x06694021 = 00000110 01101001 01000000 00100001

; after clearing bottom 12 bits, we get

; 0x06694000 = 00000110 01101001 01000000 00000000

; This tells us that the page entry base is at 0x06694000

kd> !db 06694000+e6b L8 ; read 8 bytes from the page entry at offset 0xE6B

# 6694e6b 8b ff 55 8b ec 83 ec 0c ..U.....[).t.... ; our data at that

; physical page

kd> db bf80ee6b L8 ; read 8 bytes from the virtual address

bf80ee6b 8b ff 55 8b ec 83 ec ..U.....[).t.... ; same data!

After the entire process, it is determined that the virtual address 0xBF80EE6B translates to the physical address 0x6694E6B.

Modern operating systems implement process address space separation using this mechanism. Every process is associated with a different CR3, resulting in process-specific virtual address translation. It is the magic behind each process's illusion that it has its own address space. Hopefully you will have more appreciation for the processor the next time your program accesses memory!

This section briefly discusses interrupts and exceptions, as complete implementation details can be found in Chapter 3, “The Windows Kernel.”

In contemporary computing systems, the processor is typically connected to peripheral devices through a data bus such as PCI Express, FireWire, or USB. When a device requires the processor's attention, it causes an interrupt that forces the processor to pause whatever it is doing and handle the device's request. How does the processor know how to handle the request? At the highest level, one can think of an interrupt as being associated with a number that is then used to index into an array of function pointers. When the processor receives the interrupt, it executes the function at the index associated with the interrupt and resumes execution at wherever it was before the interrupt occurred. These are called hardware interrupts because they are generated by hardware devices. They are asynchronous by nature.

When the processor is executing an instruction, it may run into exceptions. For example, an instruction could generate a divide-by-zero error, reference an invalid address, or trigger a privilege level transition. For the purpose of this discussion, exceptions can be classified into two categories: faults and traps. A fault is a correctable exception. For example, when the processor executes an instruction that references a valid memory address but the data is not present in main memory (it was paged out), a page fault exception is generated. The processor handles this by saving the current execution state, calling the page fault handler to correct this exception (by paging in the data), and re-executing the same instruction (which should no longer cause a page fault). A trap is an exception caused by executing special kinds of instructions. For example, the instruction SYSENTER causes the processor to begin executing the generic system call handler; after the handler is done, execution is resumed at the instruction immediately after SYSENTER. Hence, the major difference between a fault and a trap is where execution resumes. Operating systems commonly implement system calls through the interrupt and exception mechanism.

We finish the chapter with a walk-through of a function with fewer than 100 instructions. It is Sample J's DllMain routine. This exercise has two objectives. First, it applies almost every concept covered in the chapter (except for switch-case). Second, it teaches an important requirement in the practice of reverse engineering: reading technical manuals and online documentation. Here is the function:

01: ; BOOL __stdcall DllMain(HINSTANCE hinstDLL, DWORD fdwReason,

; LPVOID lpvReserved)

02: _DllMain@12 proc near

03: 55 push ebp

04: 8B EC mov ebp, esp

05: 81 EC 30 01 00+ sub esp, 130h

06: 57 push edi

07: 0F 01 4D F8 sidt fword ptr [ebp-8]

08: 8B 45 FA mov eax, [ebp-6]

09: 3D 00 F4 03 80 cmp eax, 8003F400h

10: 76 10 jbe short loc_10001C88 (line 18)

11: 3D 00 74 04 80 cmp eax, 80047400h

12: 73 09 jnb short loc_10001C88 (line 18)

13: 33 C0 xor eax, eax

14: 5F pop edi

15: 8B E5 mov esp, ebp

16: 5D pop ebp

17: C2 0C 00 retn 0Ch

18: loc_10001C88:

19: 33 C0 xor eax, eax

20: B9 49 00 00 00 mov ecx, 49h

21: 8D BD D4 FE FF+ lea edi, [ebp-12Ch]

22: C7 85 D0 FE FF+ mov dword ptr [ebp-130h], 0

23: 50 push eax

24: 6A 02 push 2

25: F3 AB rep stosd

26: E8 2D 2F 00 00 call CreateToolhelp32Snapshot

27: 8B F8 mov edi, eax

28: 83 FF FF cmp edi, 0FFFFFFFFh

29: 75 09 jnz short loc_10001CB9 (line 35)

30: 33 C0 xor eax, eax

31: 5F pop edi

32: 8B E5 mov esp, ebp

33: 5D pop ebp

34: C2 0C 00 retn 0Ch

35: loc_10001CB9:

36: 8D 85 D0 FE FF+ lea eax, [ebp-130h]

37: 56 push esi

38: 50 push eax

39: 57 push edi

40: C7 85 D0 FE FF+ mov dword ptr [ebp-130h], 128h

41: E8 FF 2E 00 00 call Process32First

42: 85 C0 test eax, eax

43: 74 4F jz short loc_10001D24 (line 70)

44: 8B 35 C0 50 00+ mov esi, ds:_stricmp

45: 8D 8D F4 FE FF+ lea ecx, [ebp-10Ch]

46: 68 50 7C 00 10 push 10007C50h

47: 51 push ecx

48: FF D6 call esi ; _stricmp

49: 83 C4 08 add esp, 8

50: 85 C0 test eax, eax

51: 74 26 jz short loc_10001D16 (line 66)

52: loc_10001CF0:

53: 8D 95 D0 FE FF+ lea edx, [ebp-130h]

54: 52 push edx

55: 57 push edi

56: E8 CD 2E 00 00 call Process32Next

57: 85 C0 test eax, eax

58: 74 23 jz short loc_10001D24 (line 70)

59: 8D 85 F4 FE FF+ lea eax, [ebp-10Ch]

60: 68 50 7C 00 10 push 10007C50h

61: 50 push eax

62: FF D6 call esi ; _stricmp

63: 83 C4 08 add esp, 8

64: 85 C0 test eax, eax

65: 75 DA jnz short loc_10001CF0 (line 52)

66: loc_10001D16:

67: 8B 85 E8 FE FF+ mov eax, [ebp-118h]

68: 8B 8D D8 FE FF+ mov ecx, [ebp-128h]

69: EB 06 jmp short loc_10001D2A (line 73)

70: loc_10001D24:

71: 8B 45 0C mov eax, [ebp+0Ch]

72: 8B 4D 0C mov ecx, [ebp+0Ch]

73: loc_10001D2A:

74: 3B C1 cmp eax, ecx

75: 5E pop esi

76: 75 09 jnz short loc_10001D38 (line 82)

77: 33 C0 xor eax, eax

78: 5F pop edi

79: 8B E5 mov esp, ebp

80: 5D pop ebp

81: C2 0C 00 retn 0Ch

82: loc_10001D38:

83: 8B 45 0C mov eax, [ebp+0Ch]

84: 48 dec eax

85: 75 15 jnz short loc_10001D53 (line 93)

86: 6A 00 push 0

87: 6A 00 push 0

88: 6A 00 push 0

89: 68 D0 32 00 10 push 100032D0h

90: 6A 00 push 0

91: 6A 00 push 0

92: FF 15 20 50 00+ call ds:CreateThread

93: loc_10001D53:

94: B8 01 00 00 00 mov eax, 1

95: 5F pop edi

96: 8B E5 mov esp, ebp

97: 5D pop ebp

98: C2 0C 00 retn 0Ch

99: _DllMain@12 endp

Lines 3–4 set up the function prologue, which saves the previous base frame pointer and establishes a new one. Line 5 reserves 0x130 bytes of stack space. Line 6 saves EDI. Line 7 executes the SIDT instruction, which writes the 6-byte IDT register to a specified memory region. Line 8 reads a double-word at EBP-6 and saves it in EAX. Lines 9–10 check if EAX is below-or-equal to 0x8003F400. If it is, execution is transferred to line 18; otherwise, it continues executing at line 11. Lines 11–12 do a similar check except that the condition is not-below 0x80047400. If it is, execution is transferred to line 18; otherwise, it continues executing at line 13. Line 13 clears EAX. Line 14 restores the saved EDI register in line 6. Lines 15–16 restore the previous base frame and stack pointer. Line 17 adds 0xC bytes to the stack pointer and then returns to the caller.

Before discussing the next area, note a few things about these first 17 lines. The SIDT instruction (line 7) writes the content of the IDT register to a 6-byte memory location. What is the IDT register? The Intel/AMD reference manual states that IDT is an array of 256 8-byte entries, each containing a pointer to an interrupt handler, segment selector, and offset. When an interrupt or exception occurs, the processor uses the interrupt number as an index into the IDT and calls the entry's specified handler. The IDT register is a 6-byte register; the top 4 bytes contain the base of the IDT array/table and the bottom 2 bytes store the table limit. With this in mind, you now know that line 8 is actually reading the IDT base address. Lines 9 and 11 check whether the base address is in the range (0x8003F400, 0x80047400). What is special about these seemingly random constants? If you search the Internet, you will note that 0x8003F400 is an IDT base address on Windows XP on x86. This can be verified in the kernel debugger:

0: kd> vertarget Windows XP Kernel Version 2600 (Service Pack 3) MP (2 procs) Free x86 compatible Built by: 2600.xpsp.080413-2111 … 0: kd> r @idtr idtr=8003f400 0: kd> ∼1 1: kd> r @idtr idtr=bab3c590

Why does the code check for this behavior? One possible explanation is that the developer assumed that an IDT base address falling in that range is considered “invalid” or may be the result of being virtualized. The function automatically returns zero if the IDTR is “invalid.” You can decompile this code to C as follows:

typedef struct _IDTR {

DWORD base;

SHORT limit;

} IDTR, *PIDTR;

BOOL __stdcall DllMain (HINSTANCE hinstDLL, DWORD fdwReason, LPVOID lpvReserved)

{

IDTR idtr;

__sidt(&idtr);

if (idtr.base > 0x8003F400 && idtr.base < 0x80047400h) { return FALSE; }

//line 18

…

}

If the IDT base seems valid, the code continues execution at line 18. Lines 19–20 clear EAX and set ECX to 0x49. Line 21 uses sets EDI to whatever EBP-0x12C is; since EBP is the base frame pointer, EBP-0x12C is the address of a local variable. Line 22 writes zero at the location pointed to by EBP-0x130. Lines 23–24 push EAX and 2 on the stack. Line 25 zeroes a 0x124-byte buffer starting from EBP-0x12C. Line 26 calls CreateToolhelp32Snapshot:

HANDLE WINAPI CreateToolhelp32Snapshot( _In_ DWORD dwFlags, _In_ DWORD th32ProcessID );

This Win32 API function takes two integer parameters. As a general rule, Win32 API functions follow STDCALL calling convention. Hence, the dwFlags and th32ProcessId parameters are 0x2 (line 24) and 0x0 (line 23). This function enumerates all processes on the system and returns a handle to be used in Process32Next. Lines 27–28 save the return value in EDI and check if it is -1. If it is, the return value is set to 0 and it returns (lines 30–34); otherwise, execution continues at line 35. Line 36 sets EAX to the address of the local variable previously initialized to 0 in line 22; line 40 initializes it to 0x128. Lines 37–39 push ESI, EAX, and EDI on the stack. Line 41 calls Process32First:

Function prototype

BOOL WINAPI Process32First( _In_ HANDLE hSnapshot, _Inout_ LPPROCESSENTRY32 lppe );

Relevant structure definition

typedef struct tagPROCESSENTRY32 {

DWORD dwSize;

DWORD cntUsage;

DWORD th32ProcessID;

ULONG_PTR th32DefaultHeapID;

DWORD th32ModuleID;

DWORD cntThreads;

DWORD th32ParentProcessID;

LONG pcPriClassBase;

DWORD dwFlags;

TCHAR szExeFile[MAX_PATH];

} PROCESSENTRY32, *PPROCESSENTRY32;

00000000 PROCESSENTRY32 struc ; (sizeof=0x128)

00000000 dwSize dd ?

00000004 cntUsage dd ?

00000008 th32ProcessID dd ?

0000000C th32DefaultHeapID dd ?

00000010 th32ModuleID dd ?

00000014 cntThreads dd ?

00000018 th32ParentProcessID dd ?

0000001C pcPriClassBase dd ?

00000020 dwFlags dd ?

00000024 szExeFile db 260 dup(?)

00000128 PROCESSENTRY32 ends

Because this API takes two parameters, hSnapshot is EDI (line 39, previously the returned handle from CreateToolhelp32Snapshot in line 27), and lppe is the address of a local variable (EBP-0x130). Because lppe points to a PROCESSENTRY32 structure, we immediately know that the local variable at EBP-0x130 is of the same type. It also makes sense because the documentation for Process32First states that before calling the function, the dwSize field must be set to the size of a PROCESSENTRY32 structure (which is 0x128). We now know that lines 19–25 were simply initializing this structure to 0. In addition, we can say that this local variable starts at EBP-0x130 and ends at EBP-0x8.

Line 42 tests the return value of Process32Next. If it is zero, execution begins at line 70; otherwise, it continues at line 43. Line 44 saves the address of the stricmp function in ESI. Line 45 sets ECX to the address of a local variable (EBP-0x10C), which happens to be a field in PROCESSENTRY32 (see the previous paragraph). Lines 46–48 push 0x10007C50/ECX on the stack and call stricmp. We know that stricmp takes two character strings as arguments; hence, ECX must be the szExeFile field in PROCESSENTRY32 and 0x10007C50 is the address of a string:

.data:10007C50 65 78 70 6C 6F+Str2 db 'explorer.exe',0

Line 49 cleans up the stack because stricmp uses CDECL calling convention. Line 50 checks stricmp's return value. If it is zero, meaning that the string matched “explorer.exe”, execution begins at line 66; otherwise, it continues execution at line 52. We can now decompile lines 18–51 as follows:

HANDLE h;

PROCESSENTRY32 procentry;

h = CreateToolhelp32Snapshot(TH32CS_SNAPPROCESS, 0);

if (h == INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE) { return FALSE; }

memset(&procentry, 0, sizeof(PROCESSENTRY32));

procentry.dwSize = sizeof(procentry); // 0x128

if (Process32Next(h, &procentry) == FALSE) {

// line 70

…

}

if (stricmp(procentry.szExeFile, "explorer.exe") == 0) {

// line 66

…

}

// line 52

Lines 52–65 are nearly identical to the previous block except that they form a loop with two exit conditions. The first exit condition is when Process32Next returns FALSE (line 58) and the second is when stricmp returns zero. We can decompile lines 52–65 as follows:

while (Process32Next(h, &procentry) != FALSE) {

if (stricmp(procentry.szExeFile, "explorer".exe") == 0)

break;

}

After the loop exits, execution resumes at line 66. Lines 67–68 save the matching PROCESSENTRY32's th32ParentProcessID/th32ProcessID in EAX/ECX and continue execution at 37. Notice that Line 66 is also a jump target in line 43.

Lines 70–74 read the fdwReason parameter of DllMain (EBP+C) and check whether it is 0 (DLL_PROCESS_DETACH). If it is, the return value is set to 0 and it returns; otherwise, it goes to line 82. Lines 82–85 check if the fdwReason is greater than 1 (i.e., DLL_THREAD_ATTACH, DLL_THREAD_DETACH). If it is, the return value is set to 1 and it returns; otherwise, execution continues at line 86. Lines 86–92 call CreateThread:

HANDLE WINAPI CreateThread( _In_opt_ LPSECURITY_ATTRIBUTES lpThreadAttributes, _In_ SIZE_T dwStackSize, _In_ LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE lpStartAddress, _In_opt_ LPVOID lpParameter, _In_ DWORD dwCreationFlags, _Out_opt_ LPDWORD lpThreadId );

with lpStartAddress as 0x100032D0. This block can be decompiled as follows:

if (fdwReason == DLL_PROCESS_DETACH) { return FALSE; }

if (fdwReason == DLL_THREAD_ATTACH || fdwReason == DLL_THREAD_DETACH) {

return TRUE; }

CreateThread(0, 0, (LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE) 0x100032D0, 0, 0, 0);

return TRUE;

Having analyzed the function, we can deduce that the developer's original intention was this:

x64 is an extension of x86, so most of the architecture properties are the same, with minor differences such as register size and some instructions are unavailable (like PUSHAD). The following sections discuss the relevant differences.

The register set has 18 64-bit GPRs, and can be illustrated as shown in Figure 1.6. Note that 64-bit registers have the “R” prefix.

While RBP can still be used as the base frame pointer, it is rarely used for that purpose in real-life compiler-generated code. Most x64 compilers simply treat RBP as another GPR, and reference local variables relative to RSP.

x64 supports a concept referred to as RIP-relative addressing, which allows instructions to reference data at a relative position to RIP. For example:

01: 0000000000000000 48 8B 05 00 00+ mov rax, qword ptr cs:loc_A 02: ; originally written as "mov rax, [rip]" 03: 0000000000000007 loc_A: 04: 0000000000000007 48 31 C0 xor rax, rax 05: 000000000000000A 90 nop

Line 1 reads the address of loc_A (which is 0x7) and saves it in RAX. RIP-relative addressing is primarily used to facilitate position-independent code.

Most arithmetic instructions are automatically promoted to 64 bits even though the operands are only 32 bits. For example:

48 B8 88 77 66+ mov rax, 1122334455667788h

31 C0 xor eax, eax ; will also clear the upper 32bits of RAX.

; i.e., RAX=0 after this

48 C7 C0 FF FF+ mov rax,0FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFh

FF C0 inc eax ; RAX=0 after this

On x64, virtual addresses are 64 bits in width, but most processors do not support a full 64-bit virtual address space. Current Intel/AMD processors only use 48 bits for the address space. All virtual memory addresses must be in canonical form. A virtual address is in canonical form if bits 63 to the most significant implemented bit are either all 1s or 0s. In practical terms, it means that bits 48–63 need to match bit 47. For example:

0xfffff801`c9c11000 = 11111111 11111111 11111000 00000001 11001001 11000001 00010000 00000000 ; canonical 0x000007f7`bdb67000 = 00000000 00000000 00000111 11110111 10111101 10110110 01110000 00000000 ; canonical 0xffff0800`00000000 = 11111111 11111111 00001000 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 ; non-canonical 0xffff8000`00000000 = 11111111 11111111 10000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 ; canonical 0xfffff960`000989f0 = 11111111 11111111 11111001 01100000 00000000 00001001 10001001 11110000 ; canonical

If code tries to dereference a non-canonical address, the system will cause an exception.

Recall that some calling conventions require parameters to be passed on the stack on x86. On x64, most calling conventions pass parameters through registers. For example, on Windows x64, there is only one calling convention and the first four parameters are passed through RCX, RDX, R8, and R9; the remaining are pushed on the stack from right to left. On Linux, the first six parameters are passed on RDI, RSI, RDX, RCX, R8, and R9.

A company named Acorn Computers developed a 32-bit RISC architecture named the Acorn RISC Machine (later renamed to Advanced RISC Machine) in the late 1980s. This architecture proved to be useful beyond their limited product line, so a company named ARM Holdings was formed to license the architecture for use in a wide variety of products. It is commonly found in embedded devices such as cell phones, automobile electronics, MP3 players, televisions, and so on. The first version of the architecture was introduced in 1985, and at the time of this writing it is at version 7 (ARMv7). ARM has developed a number of specific cores (e.g., ARM7, ARM7TDMI, ARM926EJS, Cortex)—not to be confused with the different architecture specifications, which are numbered ARMv1–ARMv7. While there are several versions, most devices are either on ARMv4, 5, 6, or 7. ARMv4 and v5 are relatively “old,” but they are also the most dominant and common versions of the processor (“more than 10 billion” cores in existence, according to ARM marketing). Popular consumer electronic products typically use more recent versions of the architecture. For example, the third-generation Apple iPod Touch and iPhone run on an ARMv6 chip, and later iPhone/iPad and Windows Phone 7 devices are all on ARMv7.

Whereas companies such as Intel and AMD design and manufacture their processors, ARM follows a slightly different model. ARM designs the architecture and licenses it to other companies, which then manufacture and integrate the processors into their devices. Companies such as Apple, NVIDIA, Qualcomm, and Texas Instruments market their own processors (A, Tegra, Snapdragon, and OMAP, respectively), but their core architecture is licensed from ARM. They all implement the base instruction set and memory model defined in the ARM architecture reference manual. Additional extensions can be added to the processor; for example, the Jazelle extension enables Java bytecode to be executed natively on the processor. The Thumb extension adds instructions that can be 16 or 32 bits wide, thus allowing higher code density (native ARM instructions are always 32 bits in width). The Debug extension allows engineers to analyze the physical processor using special debugging hardware. Each extension is typically represented by a letter (J, T, D, etc.). Depending on their requirements, manufacturers can decide whether they need to license these additional extensions. This is why ARMv6 and earlier processors have letters after them (e.g., ARM1156T2 means ARMv6 with Thumb-2 extension). These conventions are no longer used in ARMv7, which instead uses three profiles (Application, Real-time, and Microcontroller) and model name (Cortex) with different features. For example, ARMv7 Cortex-A series are processors with the application profile; and Cortex-M are meant for microcontrollers and only support Thumb mode execution.

This chapter covers the ARMv7 architecture as defined in the ARM Architecture Reference Manual: ARMv7-A and ARMv7-R Edition (ARM DDI 0406B).

Because ARM is a RISC architecture, there are a few basic differences between ARM and CISC architectures (x86/x64). (From a practical perspective, new versions of Intel processors have some RISC features as well—i.e., they are not “purely” CISC.) First, the ARM instruction set is very small compared to x86, but it offers more general-purpose registers. Second, the instruction length is fixed width (16 bits or 32 bits, depending on the state). Third, ARM uses a load-store model for memory access. This means data must be moved from memory into registers before being operated on, and only load/store instructions can access memory. On ARM, this translates to the LDR and STR instructions. If you want to increment a 32-bit value at a particular memory address, you must first load the value at that address to a register, increment it, and store it back. In contrast with x86, which allows most instructions to directly operate on data in memory, such a simple operation on ARM would require three instructions (one load, one increment, one store). This may imply that there is more code to read for the reverse engineer, but in practice it does not really matter much once you are used to it.

ARM also offers several different privilege levels to implement privilege isolation. In x86, privileges are defined by four rings, with ring 0 having the highest privilege and ring 3 having the lowest. In ARM, privileges are defined by eight different modes:

Code running in a given mode has access to certain privileges and registers that others may not; for example, code running in USR mode is not allowed to modify system registers (which are typically modified only in SVC mode). USR is the least privileged mode. While there are many technical differences, for the sake of simplicity you can make the analogy that USR is like ring 3 and SVC is like ring 0. Most operating systems implement kernel mode in SVC and user mode in USR. Both Windows and Linux do this.

If you recall from Chapter 1, x64 processors can execute in 32-bit, 64-bit, or both interchangeably. ARM processors are similar in that they can also operate in two states: ARM and Thumb. ARM/Thumb state determines only the instruction set, not the privilege level. For example, code running in SVC mode can be either ARM or Thumb. In ARM state, instructions are always 32 bits wide; in Thumb state, instructions can be either 16 bits or 32 bits wide. Which state the processor executes in depends on two conditions:

When an ARM core boots up, most of the time it enters ARM state and remains that way until there is an explicit or implicit change to Thumb. In practice, many recent operating system code mainly uses Thumb code because higher code density is wanted (a mixture of 16/32-bit wide instructions may be smaller in size than all 32-bit ones); applications can operate in whatever mode they want. While most Thumb and ARM instructions have the same mnemonic, 32-bit Thumb instructions have a .W suffix.

In addition to having different states of execution, ARM also supports conditional execution. This means that an instruction encodes certain arithmetic conditions that must be met in order for it to be executed. For example, an instruction can specify that it will only be executed if the result of the previous instruction is zero. Contrast this with x86, for which almost every single instruction is executed unconditionally. (Intel has a couple of instructions directly supporting conditional execution: CMOV and SETNE.) Conditional execution is useful because it cuts down on branch instructions (which are very expensive) and reduces the number of instructions to be executed (which leads to higher code density). All instructions in ARM state support conditional execution, but by default they execute unconditionally. In Thumb state, a special instruction IT is required to enable conditional execution.

Another unique ARM feature is the barrel shifter. Certain instructions can “contain” another arithmetic instruction that shifts or rotates a register. This is useful because it can shrink multiple instructions into one; for example, you want to multiply a register by 2 and then store the result in another register. Normally, this would require two instructions (a multiply followed by a move), but with the barrel shifter you can include the multiply (shift left by 1) inside the MOV instruction. The instruction would be something like the following:

MOV R1, R0, LSL #1 ; R1 = R0 * 2

Similar to high-level languages, ARM supports operations on different data types. The supported data types are: 8-bit (byte), 16-bit (half-word), 32-bit (word), and 64-bit (double-word).

The ARM architecture defines sixteen 32-bit general-purpose registers, numbered R0, R1, R2, . . . , R15. While all of them are available to the application programmer, in practice the first 12 registers are for general-purpose usage (such as EAX, EBX, etc., in x86) and the last three have special meaning in the architecture:

1: 0x00008344 push {lr}

2: 0x00008346 mov r0, pc

3: 0x00008348 mov.w r2, r1, lsl #31

4: 0x0000834c pop {pc}

After line 2 is executed, R0 will hold the value 0x0000834a (=0x00008346+4):

(gdb) br main

Breakpoint 1 at 0x8348

…

Breakpoint 1, 0x00008348 in main ()

(gdb) disas main

Dump of assembler code for function main:

0x00008344 <+0>: push {lr}

0x00008346 <+2>: mov r0, pc

=> 0x00008348 <+4>: mov.w r2, r1, lsl #31

0x0000834c <+8>: pop {pc}

0x0000834e <+10>: lsls r0, r0, #0

End of assembler dump.

(gdb) info register pc

pc 0x8348 0x8348 <main+4>

(gdb) info register r0

r0 0x834a 33610

Here we set a breakpoint at 0x00008348. When it hits, we show the PC and R0 register; as shown, PC points to the third instruction at 0x00008348 (about to be executed) and R0 shows the previously read PC value. From this example, you can see that when directly reading PC, it follows the definition; but when debugging, PC points to the instruction that is to be executed.

The reason for this peculiarity is due to legacy pipelining from older ARM processors, which always fetched two instructions ahead of the currently executing instruction. Nowadays, the pipelines are much more complicated so this does not really matter much, but ARM retains this definition to ensure compatibility with earlier processors.

Similar to other architectures, ARM stores information about the current execution state in the current program status register (CPSR). From an application programmer's perspective, CPSR is similar to the EFLAGS/RFLAG register in x86/x64. Some documentation may discuss the application program status register (APSR), which is an alias for certain fields in the CPSR. There are many flags in the CPSR, some of which are illustrated in Figure 2.1 (others are covered in later sections).

ARM offers the concept of coprocessors to support additional instructions and system-level settings. For example, if the system supports a memory management unit (MMU), then its settings must be exposed to boot or kernel code. On x86/x64, these settings are stored in CR0 and CR4; on ARM, they are stored in coprocessor 15. There are 16 coprocessors in the ARM architecture, each identified by a number: CP0, CP1, . . . , CP15. (When used in code, these are referred to as P0, . . . , P15.) The first 13 are either optional or reserved by ARM; the optional ones can be used by manufacturers to implement manufacturer-specific instructions or features. For example, CP10 and CP11 are usually used for floating-point and NEON support. Each coprocessor contains additional “opcodes” and registers that can be controlled through special ARM instructions. CP14 and CP15 are used for debug and system settings; CP15, usually known as the system control coprocessor, stores most of the system settings (caching, paging, exceptions, and so forth).

Each coprocessor has 16 registers and eight corresponding opcodes. The semantic of these registers and opcodes is specific to the coprocessor. Accessing coprocessors can only be done through the MRC (read) and MCR (write) instructions; they take a coprocessor number, register number, and opcodes. For example, to read the translation base register (similar to CR3 in x86/x64) and save it in R0, you use the following:

MRC p15, 0, r0, c2, c0, 0 ; save TTBR in r0

This says, “read coprocessor 15's C2/C0 register using opcode 0/0 and store the result in the general-purpose register R0.” Because there are so many registers and opcodes within each coprocessor, you must read the documentation to determine the precise meaning of each. Some registers (C13/C0) are reserved for operating systems in order to store process- or thread-specific data.

While the MRC and MCR instructions do not require high privilege (i.e., they can be executed in USR mode), some of the coprocessor registers and opcodes are only accessible in SVC mode. Attempts to read certain registers without sufficient privilege will result in an exception. In practice, you will infrequently see these instructions in user-mode code; they are commonly found in very low-level code such as ROM, boot loaders, firmware, or kernel-mode code.

At this point, you are ready to look at the important ARM instructions. Besides conditional execution and barrel shifters, there are several other peculiarities about the instructions that are not found in x86. First, some instructions can operate on a range of registers in sequence. For example, to store five registers, R6–R10, at a particular memory location referenced by R1, you would write STM R1, {R6-R10}. R6 would be stored at memory address R1, R7 at R1+4, R8 at R1+8, and so on. Nonconsecutive registers can also be specified via comma separation (e.g., {R1,R5,R8}). In ARM assembly syntax, the register ranges are usually specified inside curly brackets. Second, some instructions can optionally update the base register after a read/write operation. This is usually done by affixing an exclamation mark (!) after the register name. For example, if you were to rewrite the previous instruction as STM R1!, {R6-R10} and execute it, then R1 will be updated with the address immediately after where R10 was stored. To make it clearer, here is an example:

01: (gdb) disas main

02: Dump of assembler code for function main:

03: => 0x00008344 <+0>: mov r6, #10

04: 0x00008348 <+4>: mov r7, #11

05: 0x0000834c <+8>: mov r8, #12

06: 0x00008350 <+12>: mov r9, #13

07: 0x00008354 <+16>: mov r10, #14

08: 0x00008358 <+20>: stmia sp!, {r6, r7, r8, r9, r10}

09: 0x0000835c <+24>: bx lr

10: End of assembler dump.

11: (gdb) si

12: 0x00008348 in main ()

13: …

14: 0x00008358 in main ()

15: (gdb) info reg sp

16: sp 0xbedf5848 0xbedf5848

17: (gdb) si

18: 0x0000835c in main ()

19: (gdb) info reg sp

20: sp 0xbedf585c 0xbedf585c

21: (gdb) x/6x 0xbedf5848

22: 0xbedf5848: 0x0000000a 0x0000000b 0x0000000c 0x0000000d

23: 0xbedf5858: 0x0000000e 0x00000000

Line 15 displays the value of SP (0xbedf5848) before executing the STM instruction; lines 17 and 19 execute the STM instruction and display the updated value of SP. Line 21 dumps six words starting at the old value of SP. Note that R6 was stored at the old SP, R7 at SP+0x4, R8 at SP+0x8, R9 at SP+0xc, and R10 at SP+0x10. The new SP (0xbedf585c) is immediately after where R10 was stored.

The preceding section mentions that ARM is a load-store architecture, which means that data must be loaded into registers before it can be operated on. The only instructions that can touch memory are load and store; all other instructions can operate only on registers. To load means to read data from memory and save it in a register; to store means to write the content of a register to a memory location. On ARM, the load/store instructions are LDR/STR, LDM/STM, and PUSH/POP.

These instructions can load and store 1, 2, or 4 bytes to and from memory. Their full syntax is somewhat complicated because there are several different ways to specify the offset and side effects for updating the base register. Consider the simplest case:

01: 03 68 LDR R3, [R0] ; R3 = *R0 02: 23 60 STR R3, [R4] ; *R4 = R3;

For the instruction in line 1, R0 is the base register and R3 is the destination; it loads the word value at address R0 into R3. In line 2, R4 is the base register and R3 is the destination; it takes the value in R3 and stores at the memory address R4. This example is simple because the memory address is specified by the base register.

At a fundamental level, the LDR/STR instructions take a base register and an offset; there are three offset forms and three addressing modes for each form. We begin by discussing the offset forms: immediate, register, and scaled register.

The first offset form uses an immediate as the offset. An immediate is simply an integer. It is added to or subtracted from the base register to access data at an offset known at compile time. The most common usage is to access a particular field in a structure or vtable. The general format is as follows:

Rb is the base register, and imm is the offset to be added to Rb.

For example, suppose that R0 holds a pointer to a KDPC structure and the following code:

Structure Definition

0:000> dt ntkrnlmp!_KDPC +0x000 Type : UChar +0x001 Importance : UChar +0x002 Number : Uint2B +0x004 DpcListEntry : _LIST_ENTRY +0x00c DeferredRoutine : Ptr32 void +0x010 DeferredContext : Ptr32 Void +0x014 SystemArgument1 : Ptr32 Void +0x018 SystemArgument2 : Ptr32 Void +0x01c DpcData : Ptr32 Void

Code

01: 13 23 MOVS R3, #0x13 02: 03 70 STRB R3, [R0] 03: 01 23 MOVS R3, #1 04: 43 70 STRB R3, [R0,#1] 05: 00 23 MOVS R3, #0 06: 43 80 STRH R3, [R0,#2] 07: C3 61 STR R3, [R0,#0x1C] 08: C1 60 STR R1, [R0,#0xC] 09: 02 61 STR R2, [R0,#0x10]

In this case, R0 is the base register and the immediates are 0x1, 0x2, 0xC, 0x10, and 0x1C. The snippet can be translated into C as follows:

KDPC *obj = …; /* R0 is obj */ obj->Type = 0x13; obj->Importance = 0x1; obj->Number = 0x0; obj->DpcData = NULL; obj->DeferredRoutine = R1; /* R1 is unknown to us */ obj->DeferredContext = R2; /* R2 is unknown to us */

This offset form is similar to the MOV Reg, [Reg + Imm] on the x86/x64.

The second offset form uses a register as the offset. It is commonly used in code that needs to access an array but the index is computed at runtime. The general format is as follows:

Depending on the context, either Rb or Rc can be the base/offset. Consider the following two examples:

Example 1

01: 03 F0 F2 FA BL strlen 02: 06 46 MOV R6, R0 ; R0 is strlen's return value 03: … 04: BB 57 LDRSB R3, [R7,R6] ; in this case, R6 is the offset

Example 2

01: B3 EB 05 08 SUBS.W R8, R3, R5 02: 2F 78 LDRB R7, [R5] 03: 18 F8 05 30 LDRB.W R3, [R8,R5] ; here, R5 is the base and R8 is the offset 04: 9F 42 CMP R7, R3

This is similar to the MOV Reg, [Reg + Reg] form on x86/x64.

The third offset form uses a scaled register as the offset. It is commonly used in a loop to iterate over an array. The barrel shifter is used to scale the offset. The general format is as follows:

Rb is the base register; Rc is an immediate; and <shifter> is the operation performed on the immediate—typically, a left/right shift to scale the immediate. For example: