First Edition

Why Map Librarianship and Geoliteracy?

Chapter 1: Introduction to Maps and Librarians

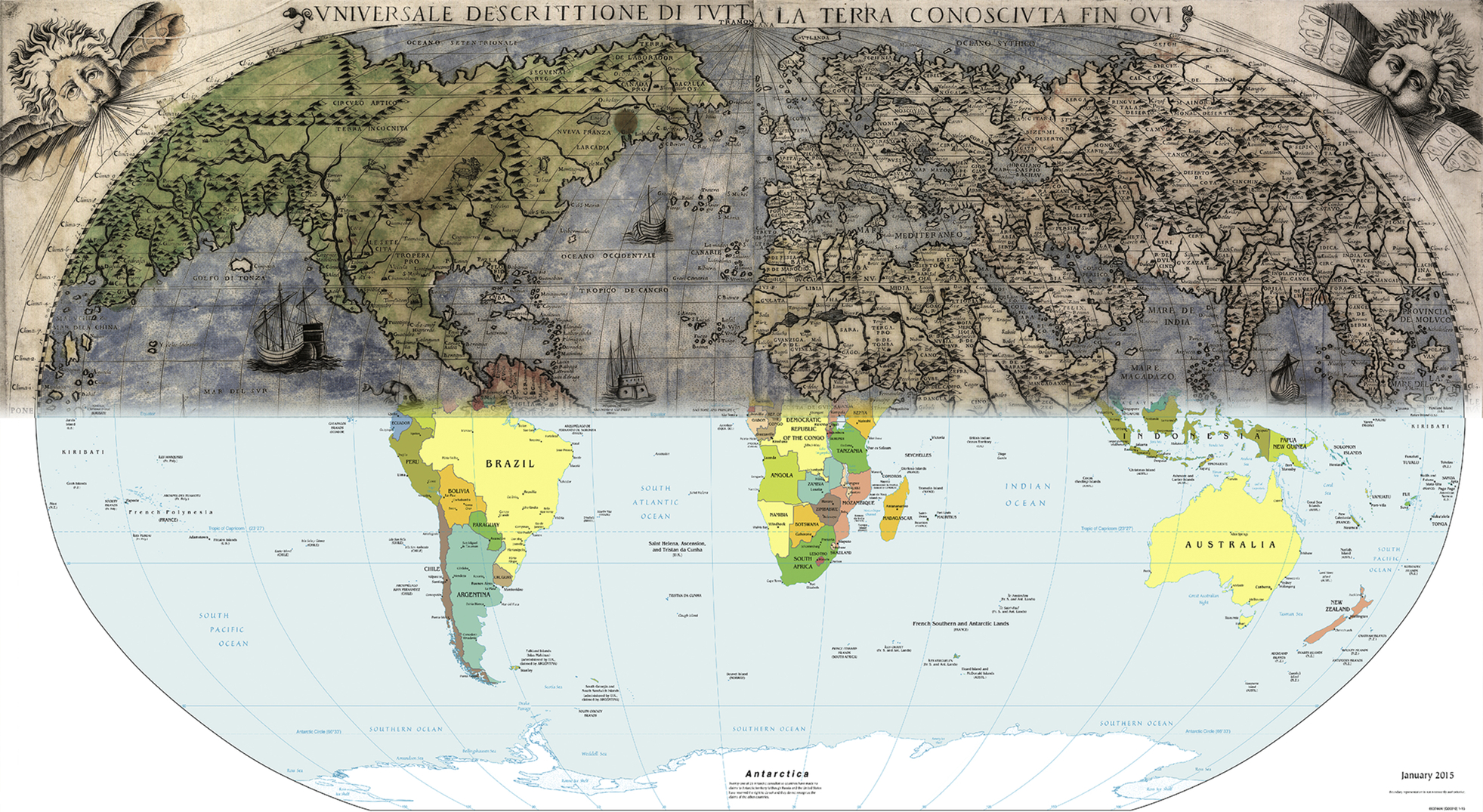

1.3 Historic Progression of Maps and Cartographers

1.4 What Are NeoGeography and NeoCartography?

1.5 Historic Progression of Map Librarianship

1.6 What Is NeoMap Librarianship?

Chapter 2: Spatial Thinking and Geo-Literacy

2.1 Geo-Literacy: Location-Based Spatial Thinking

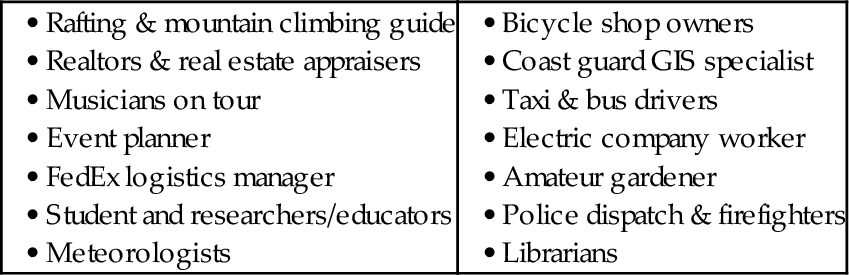

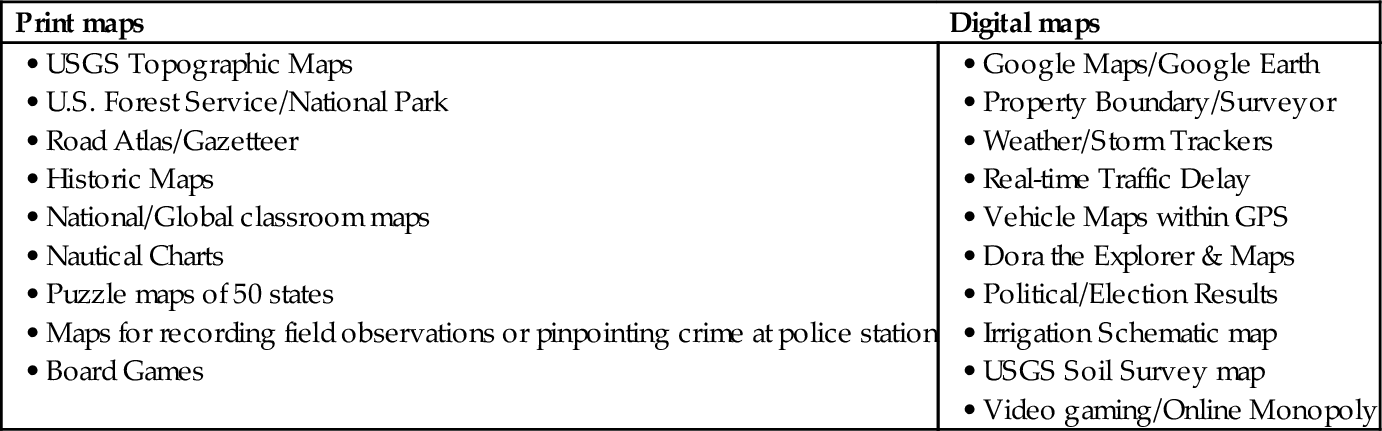

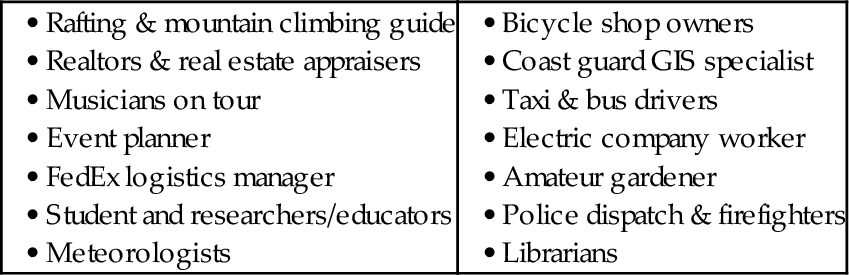

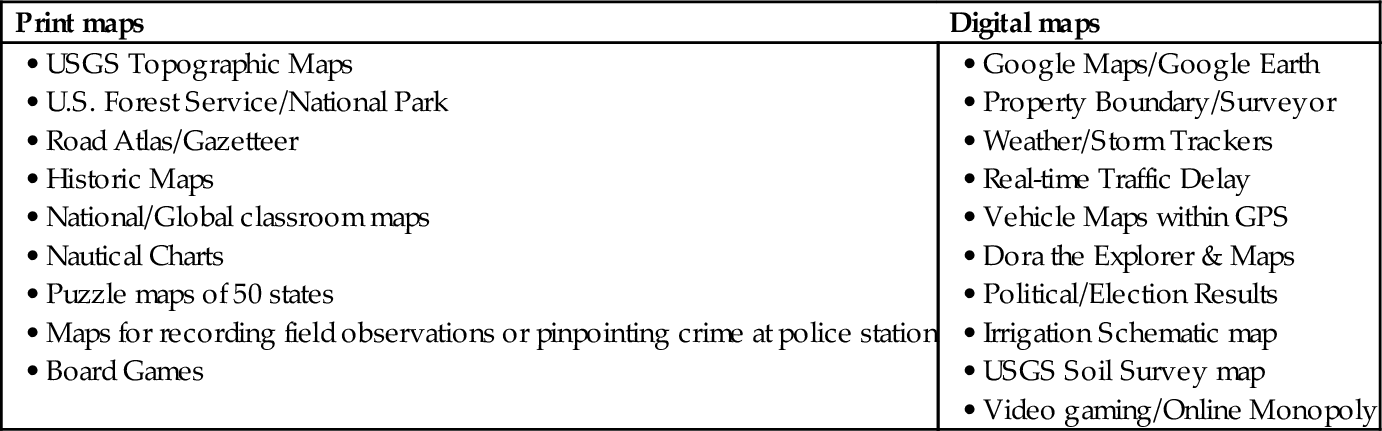

2.3 Reference and Thematic Maps

2.4 Mapping Data—Map Symbology Techniques

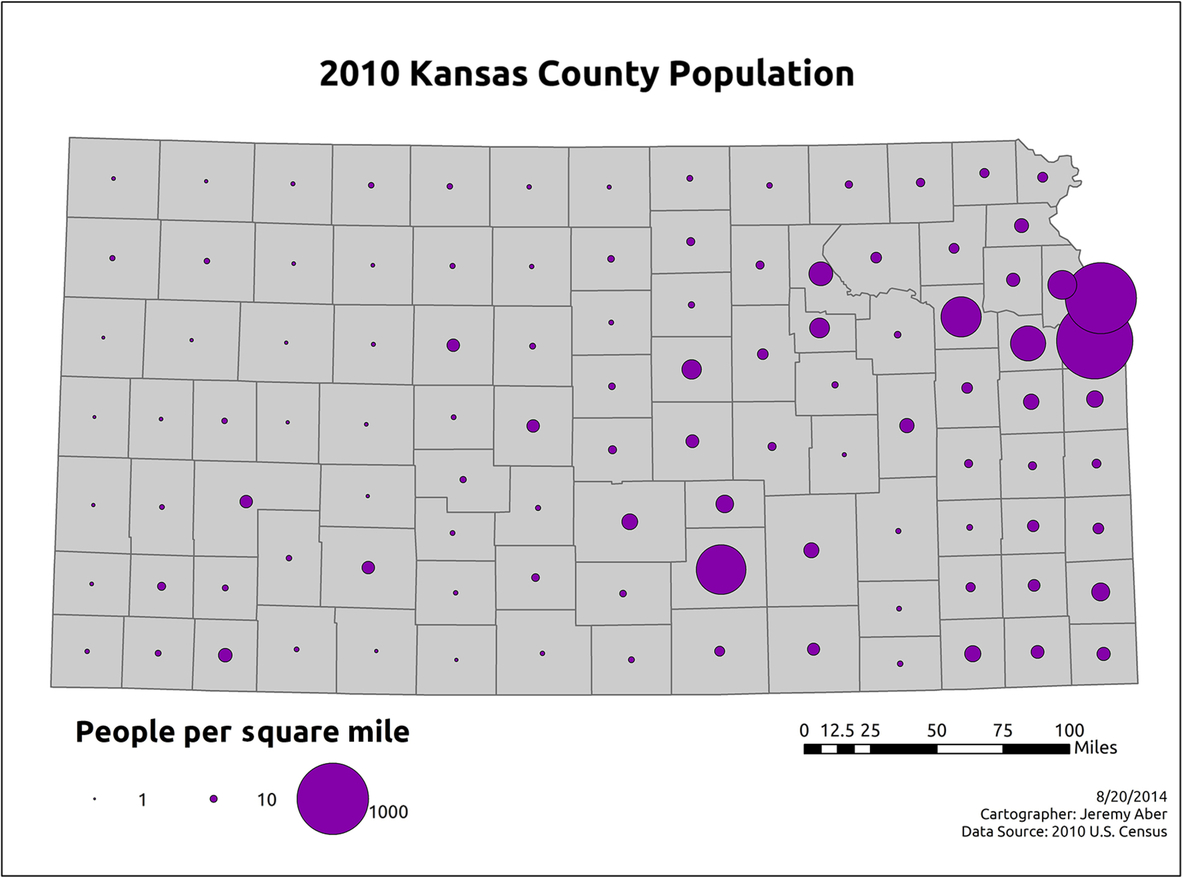

2.7 The Proportional Symbol Map

2.14 Coal, Oil, and Natural Gas Investigation Maps

2.24 Globes and Raised-Relief Models

Chapter 3: Basic Map Concepts—The Science of Cartography

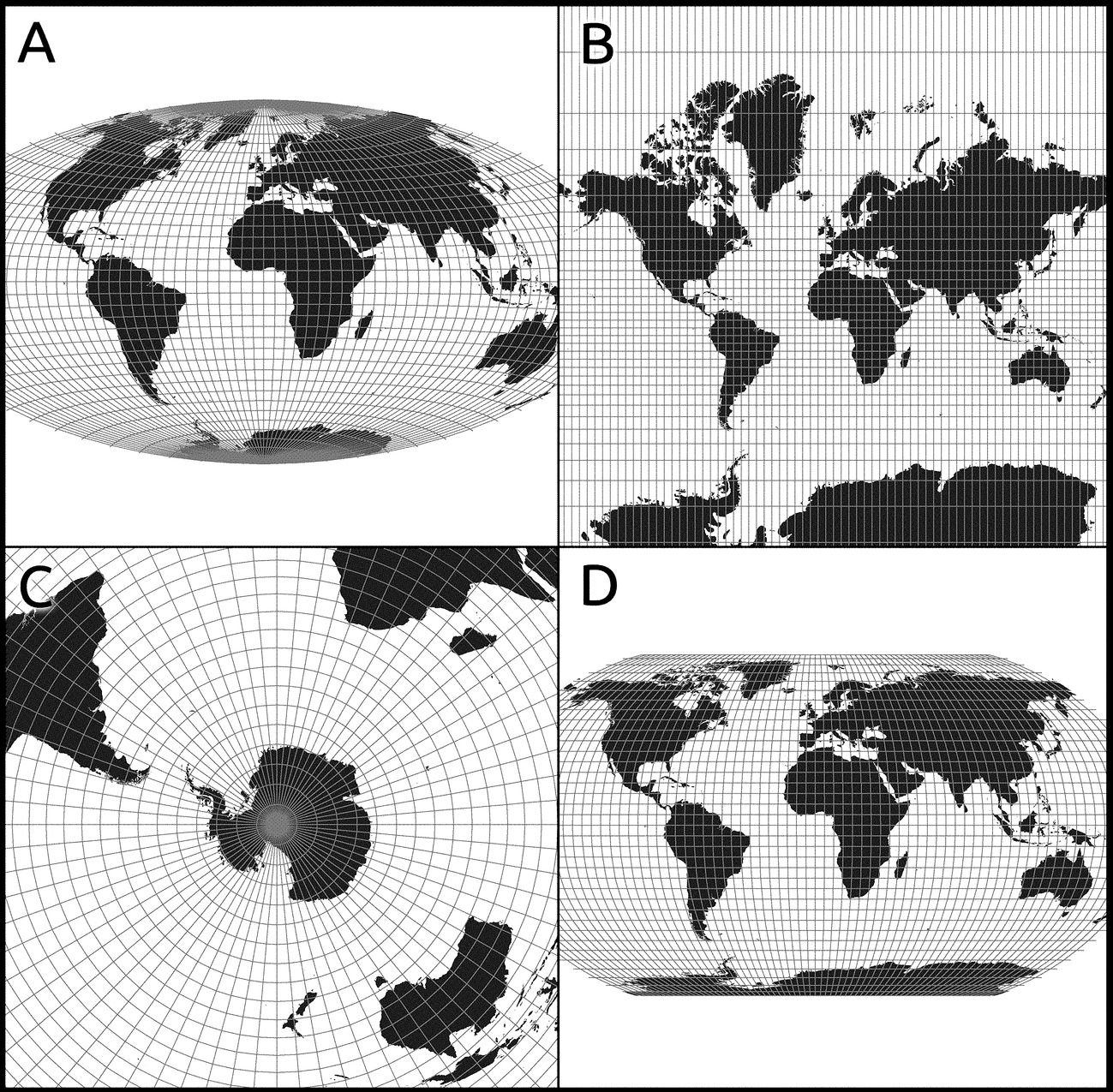

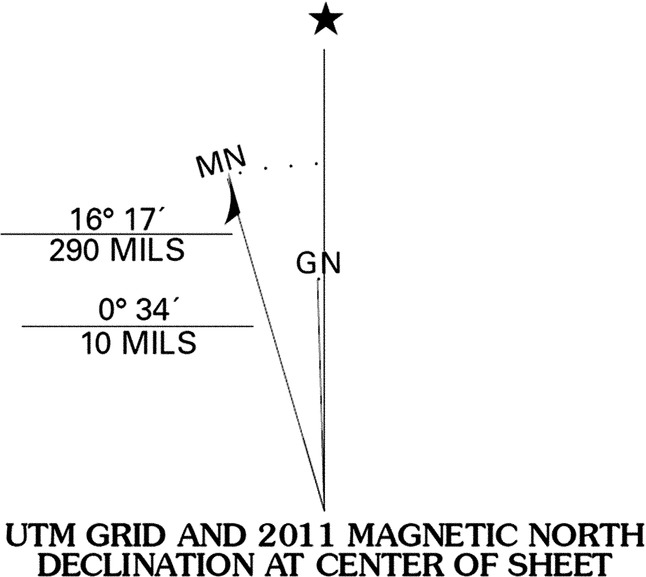

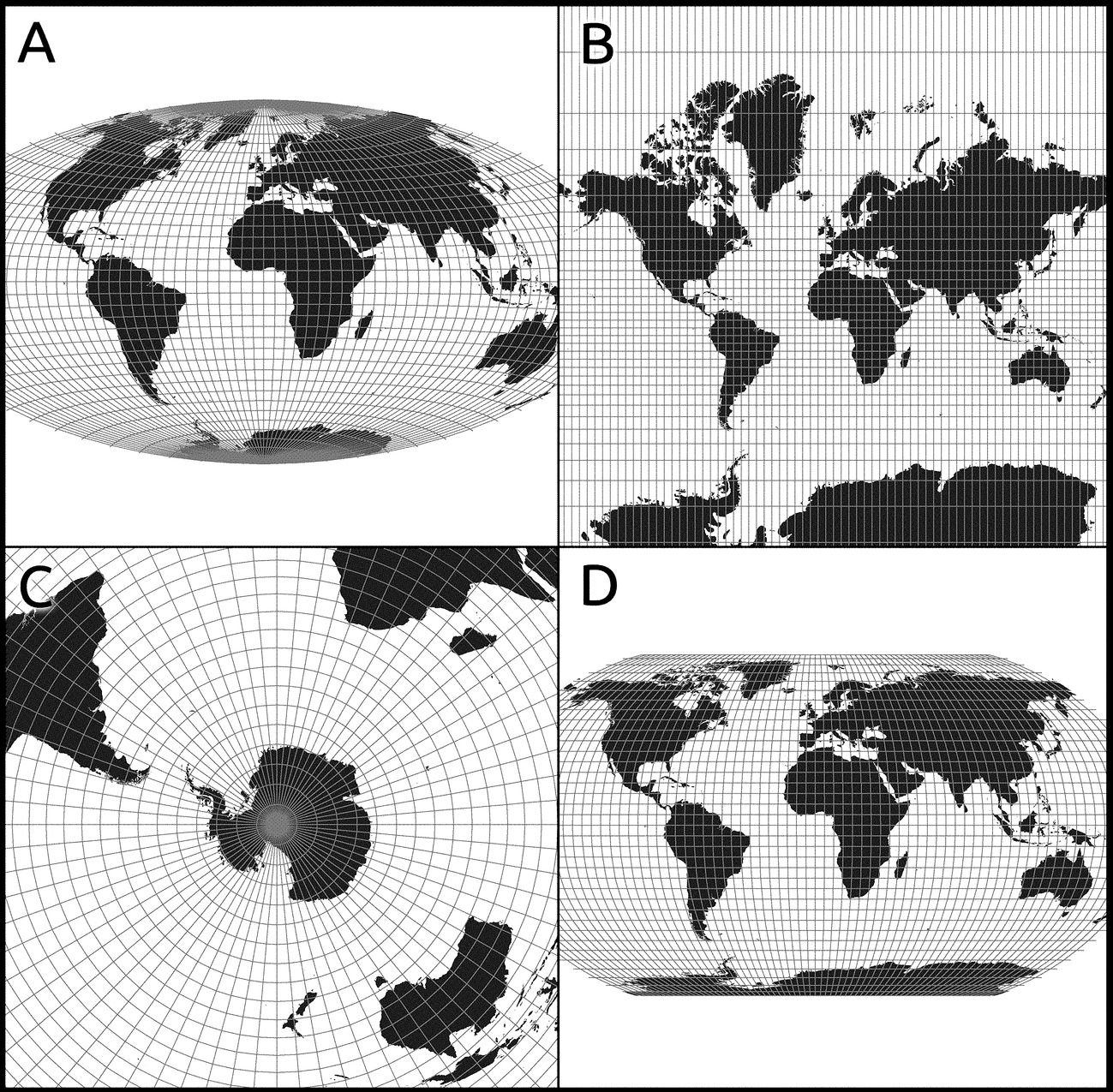

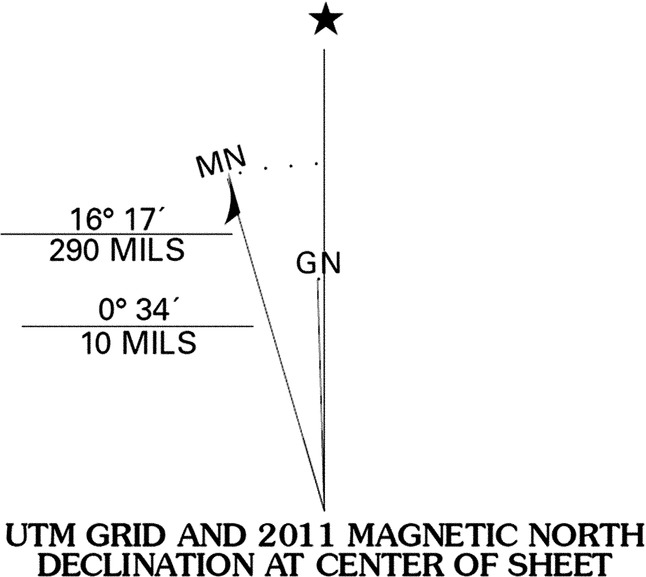

3.8 Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinate System

3.9 State Plane Coordinate System

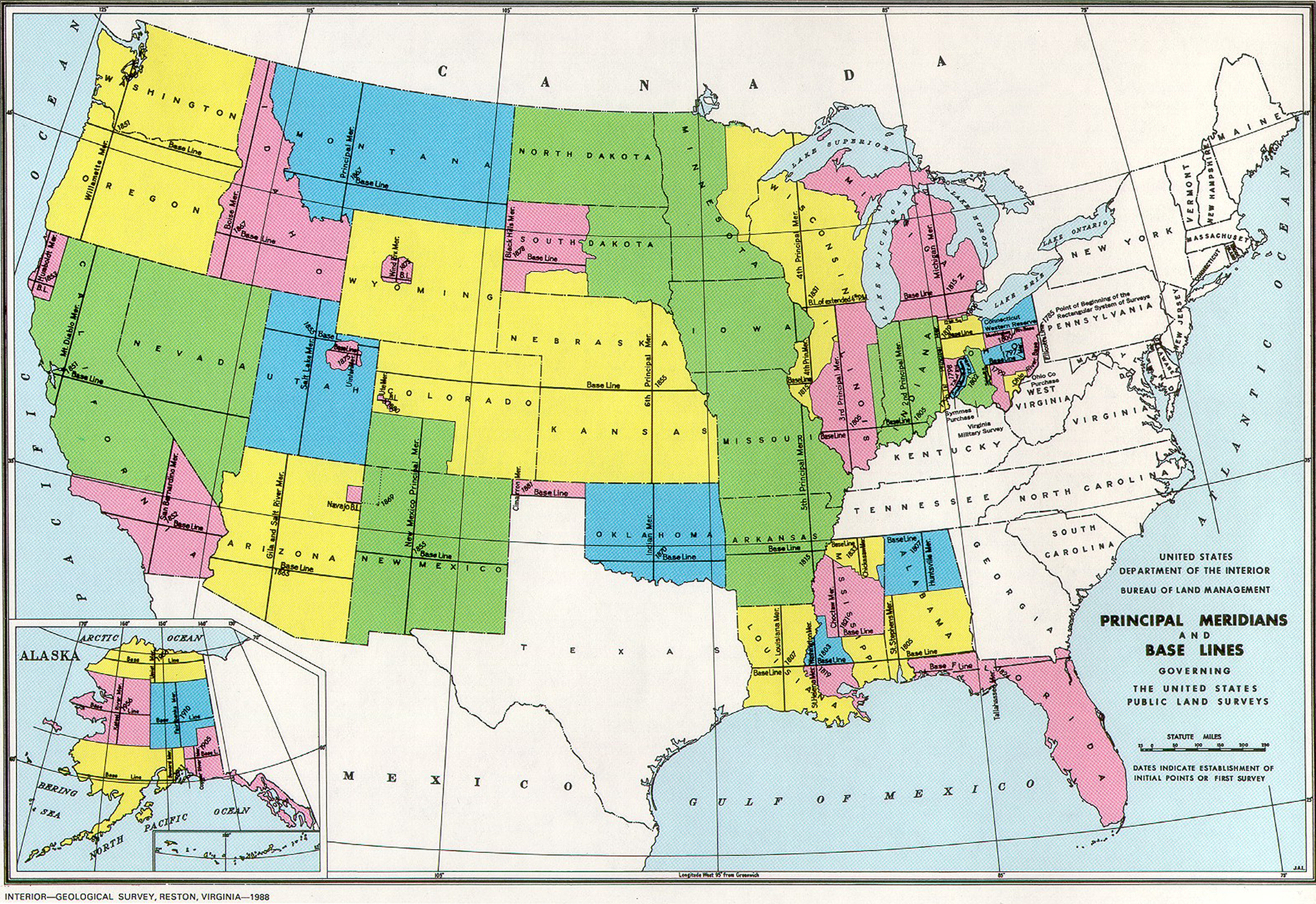

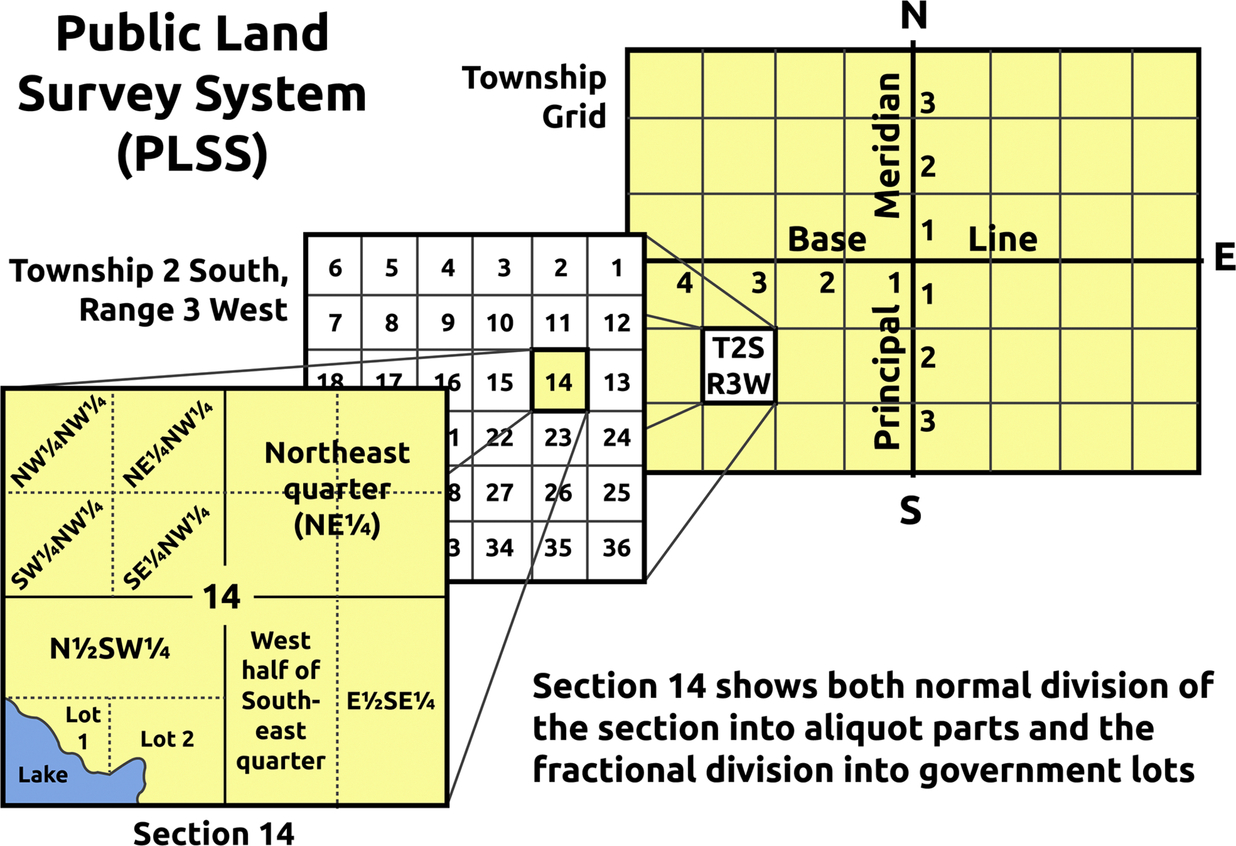

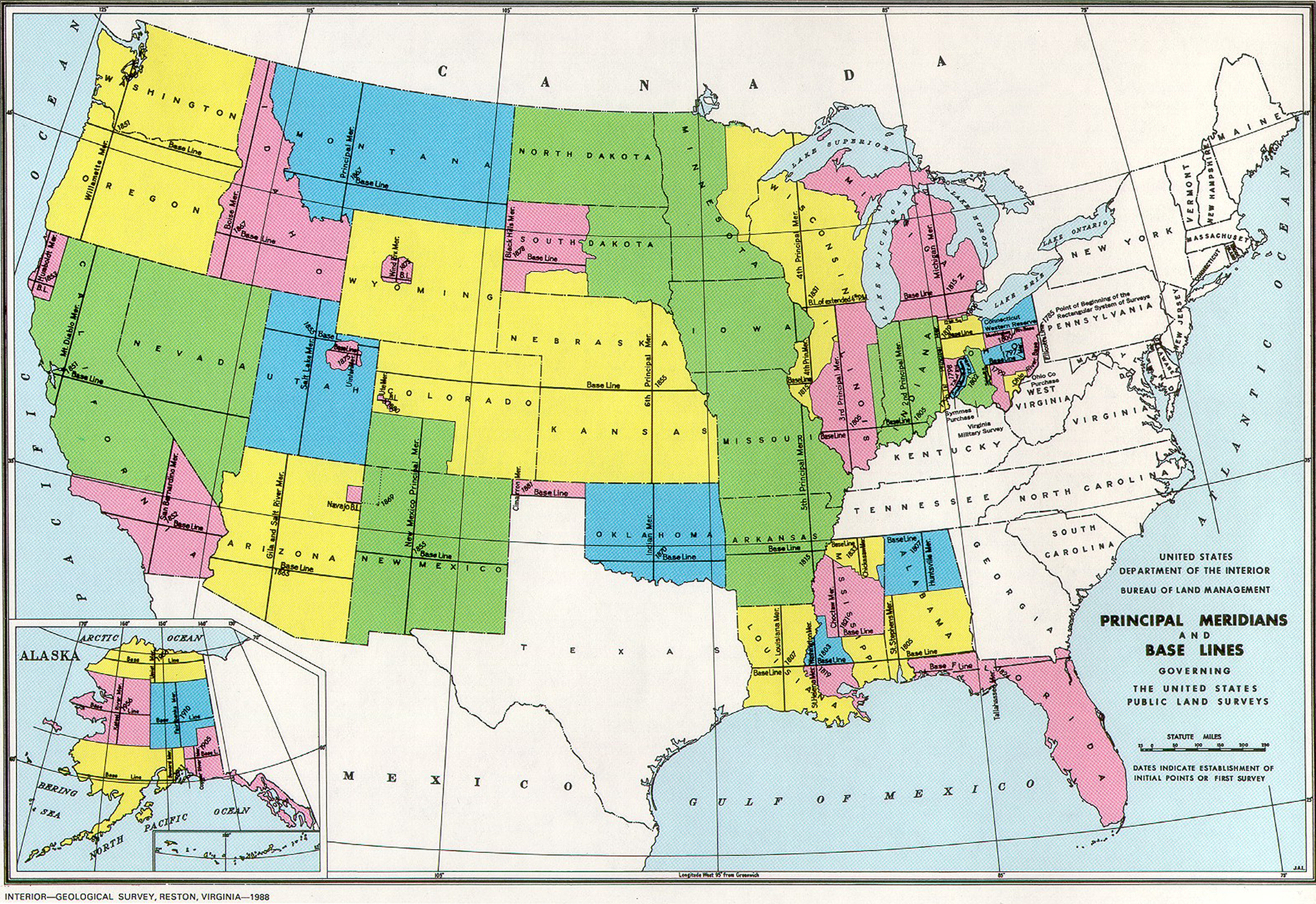

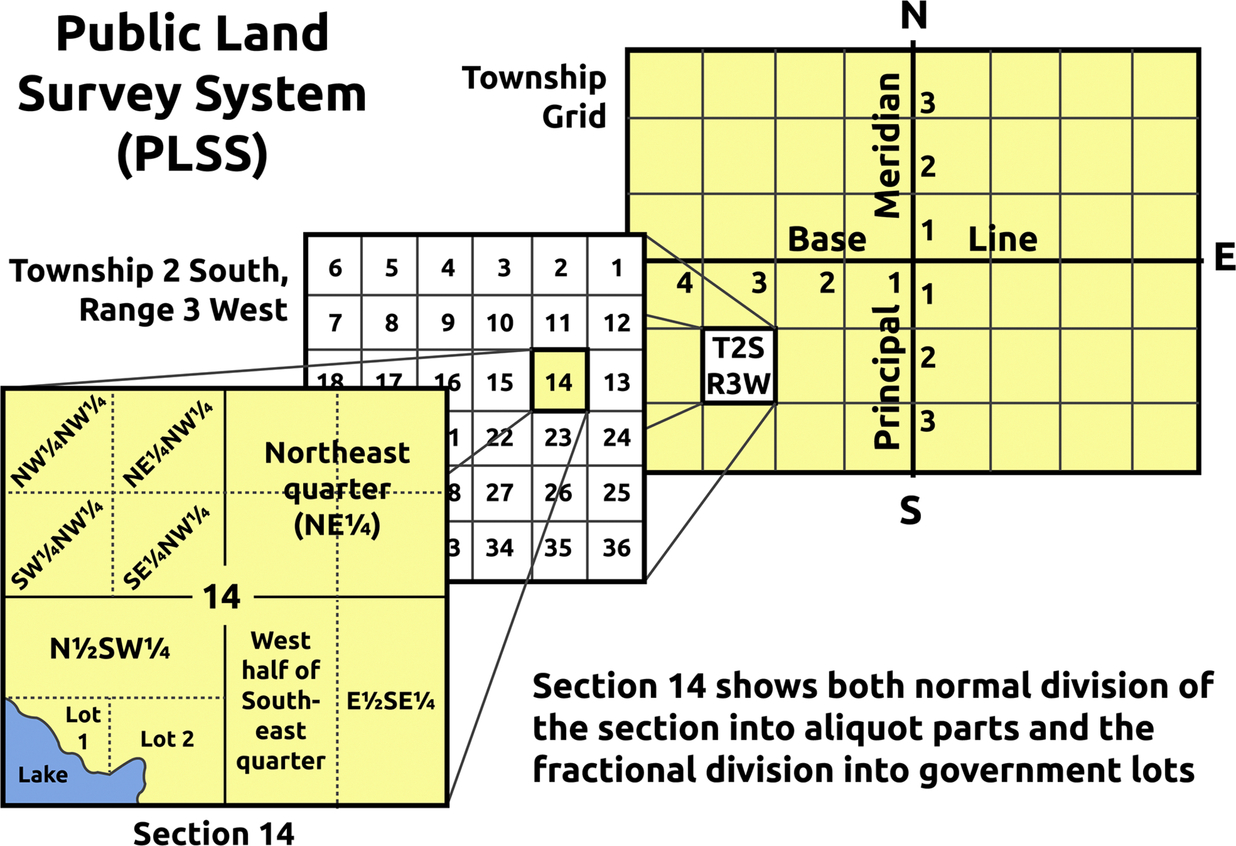

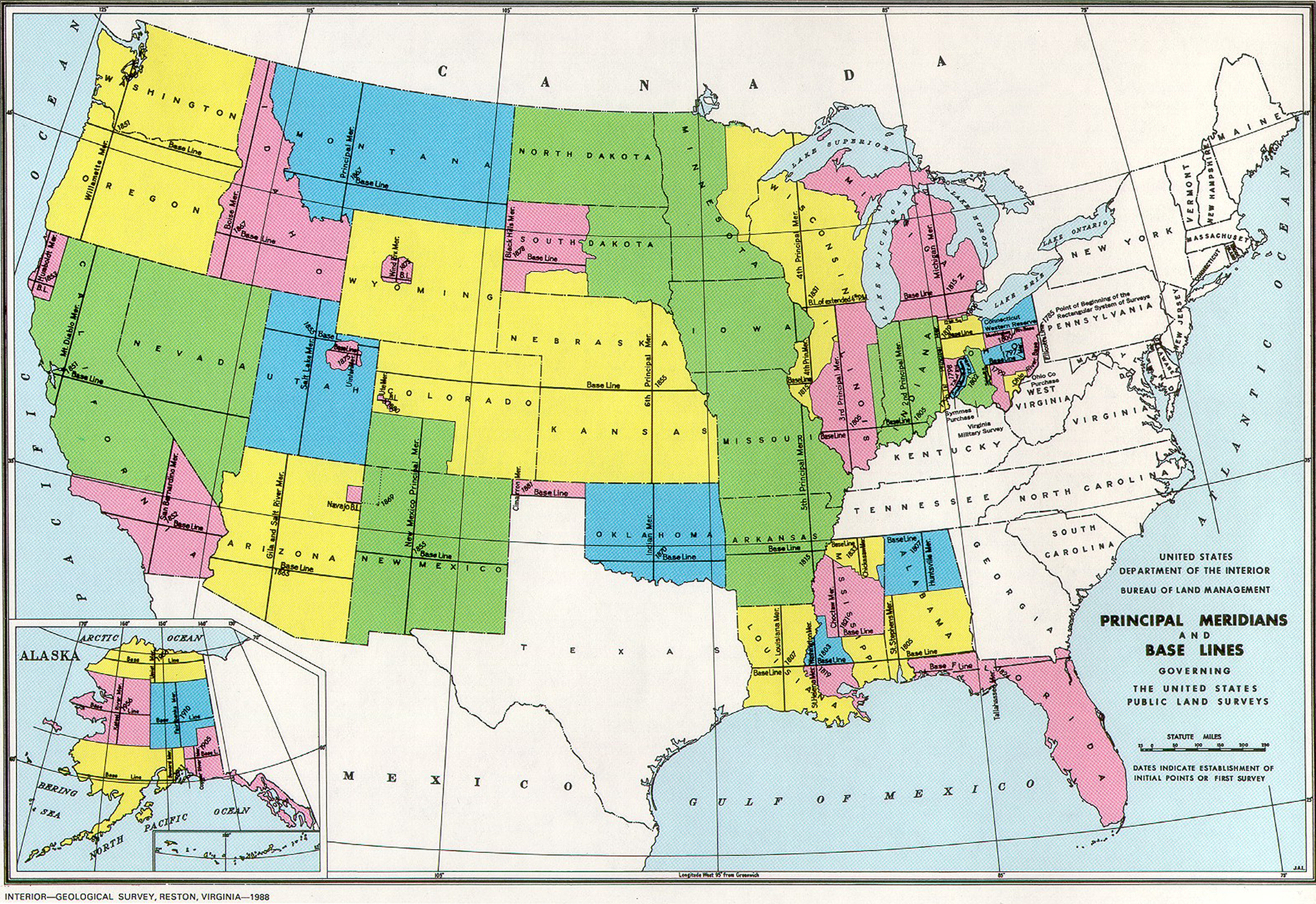

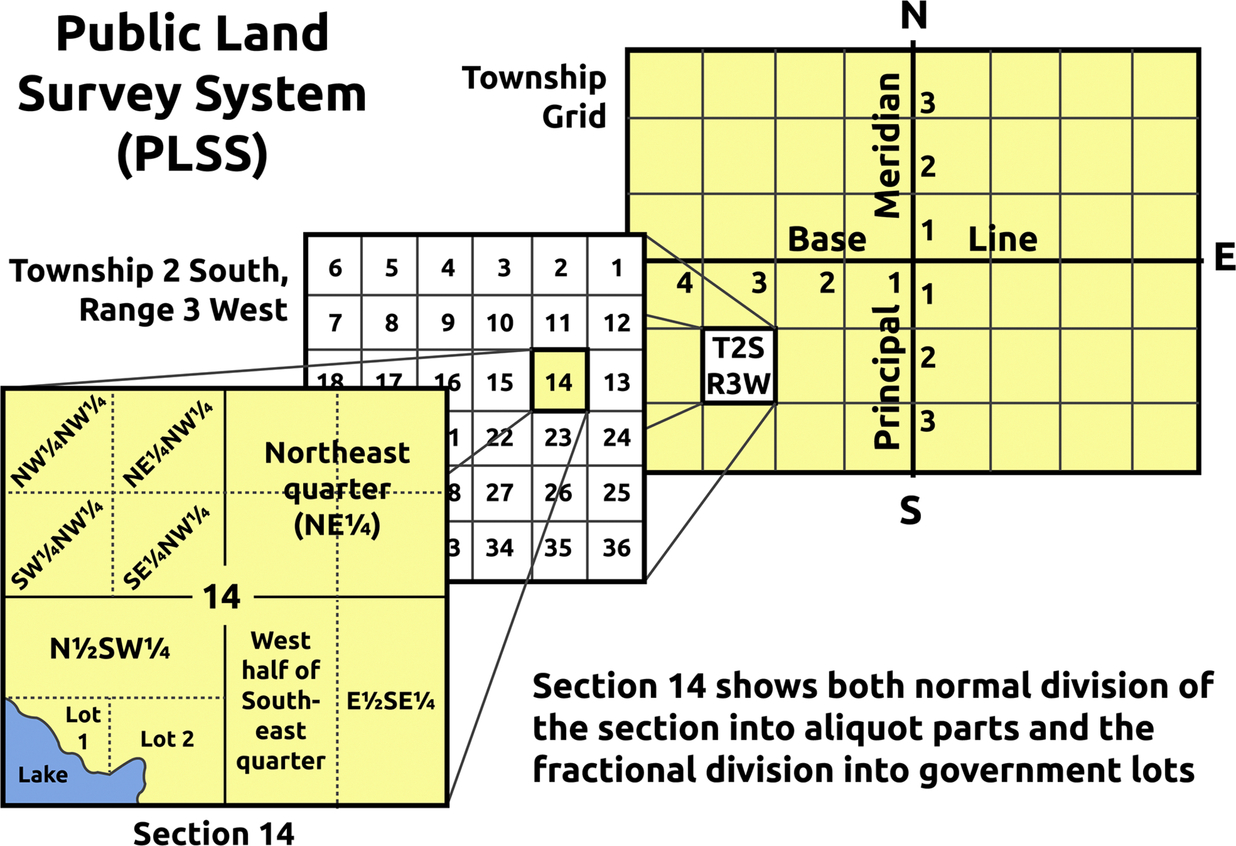

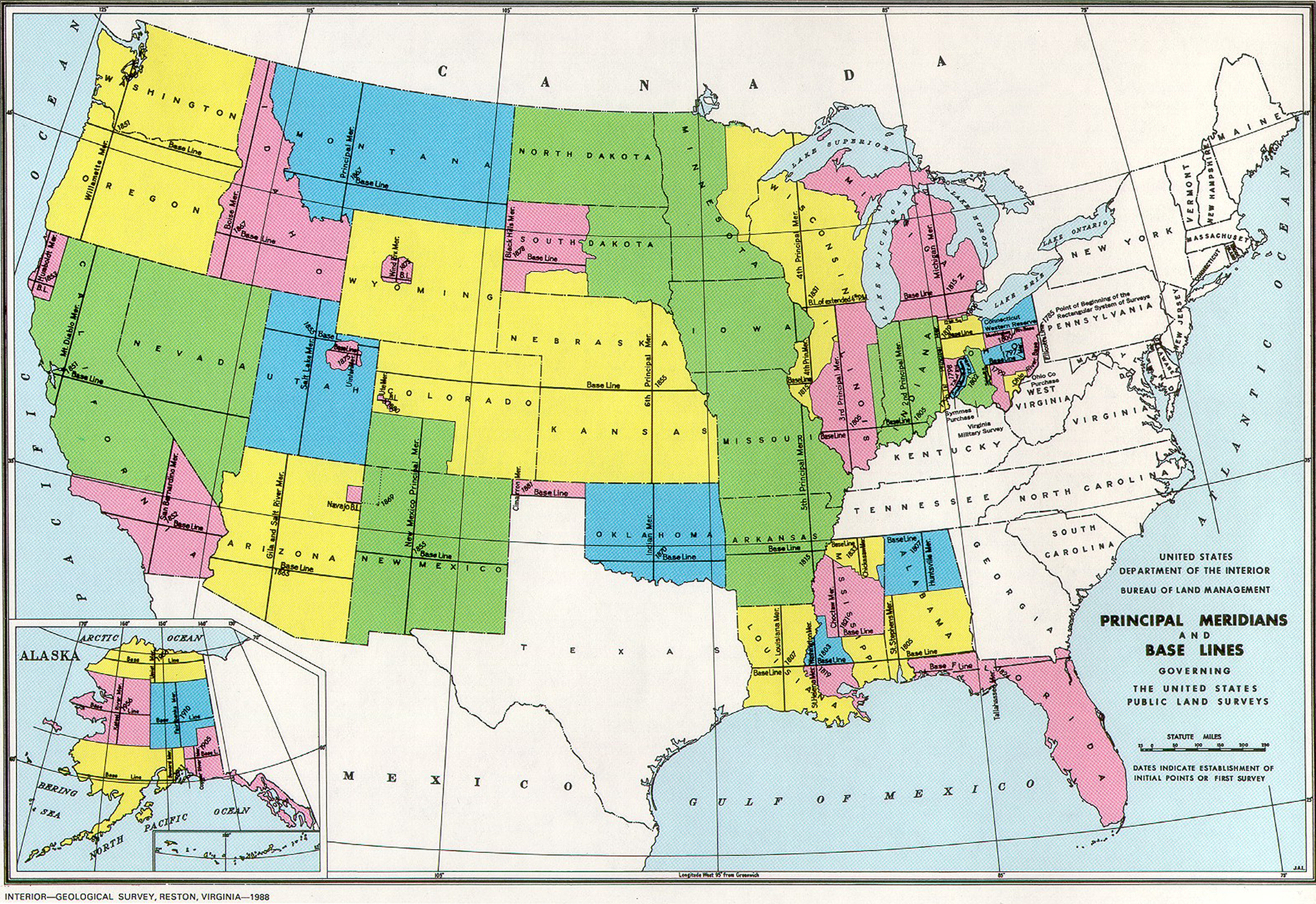

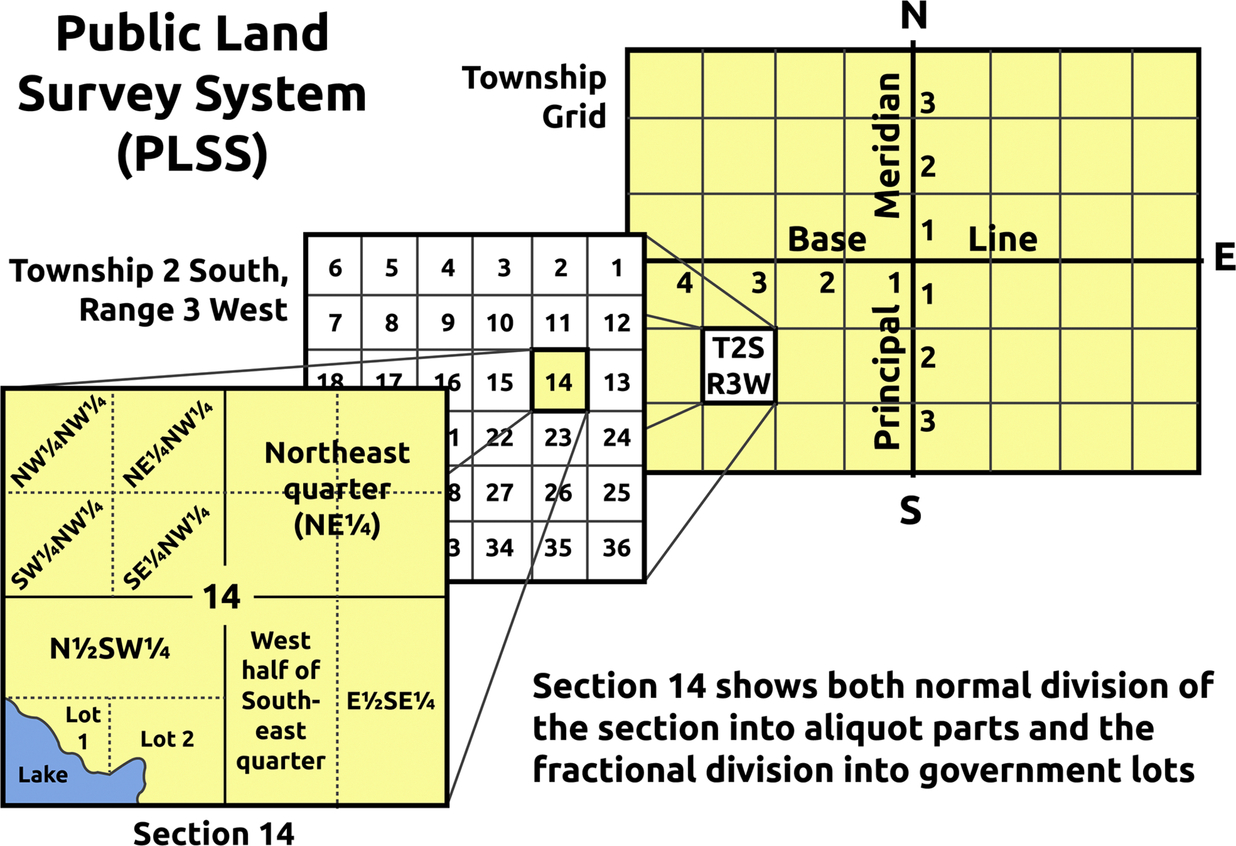

3.10 Public Land Survey System

Chapter 4: Geographic Information Systems and Remote Sensing

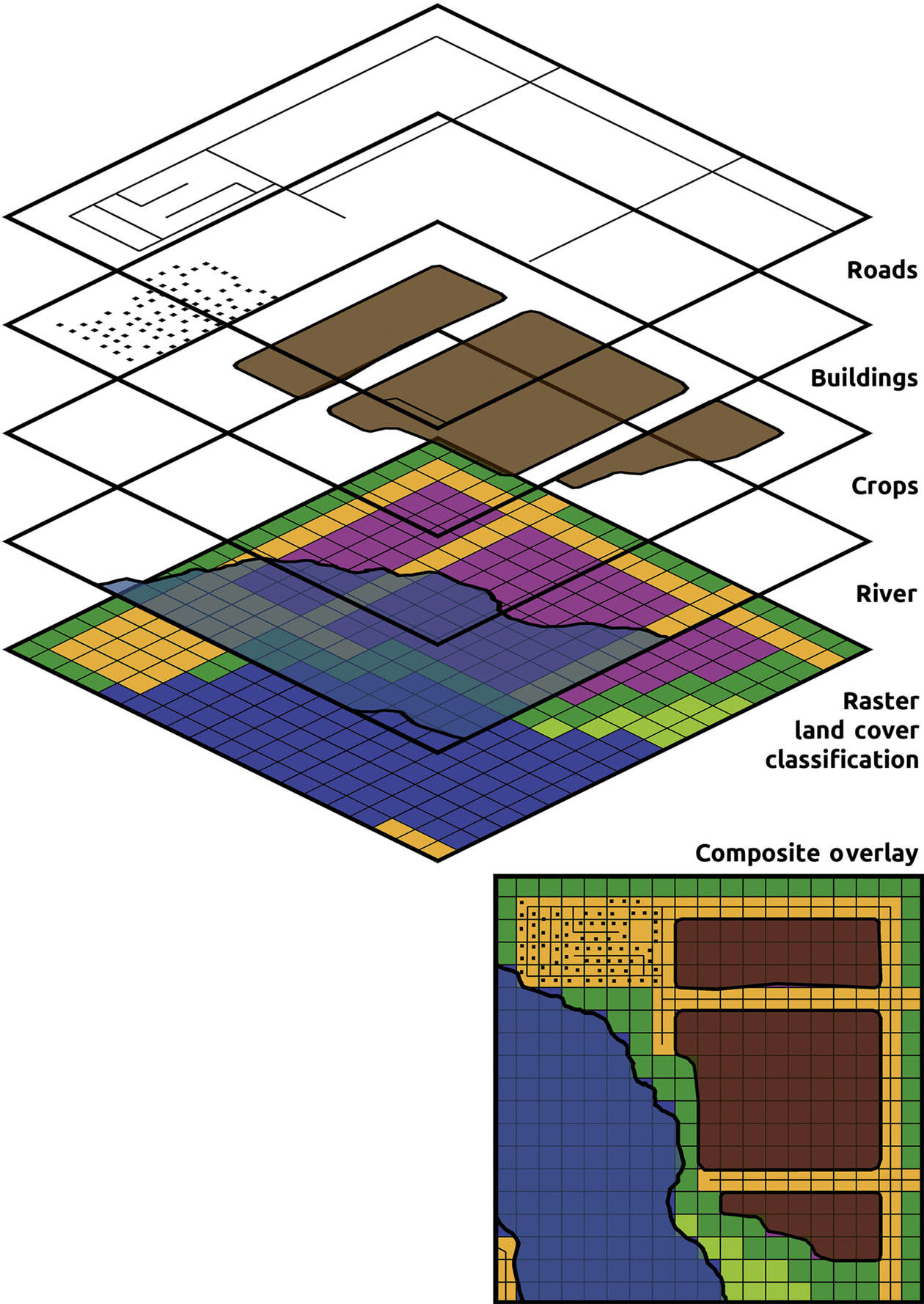

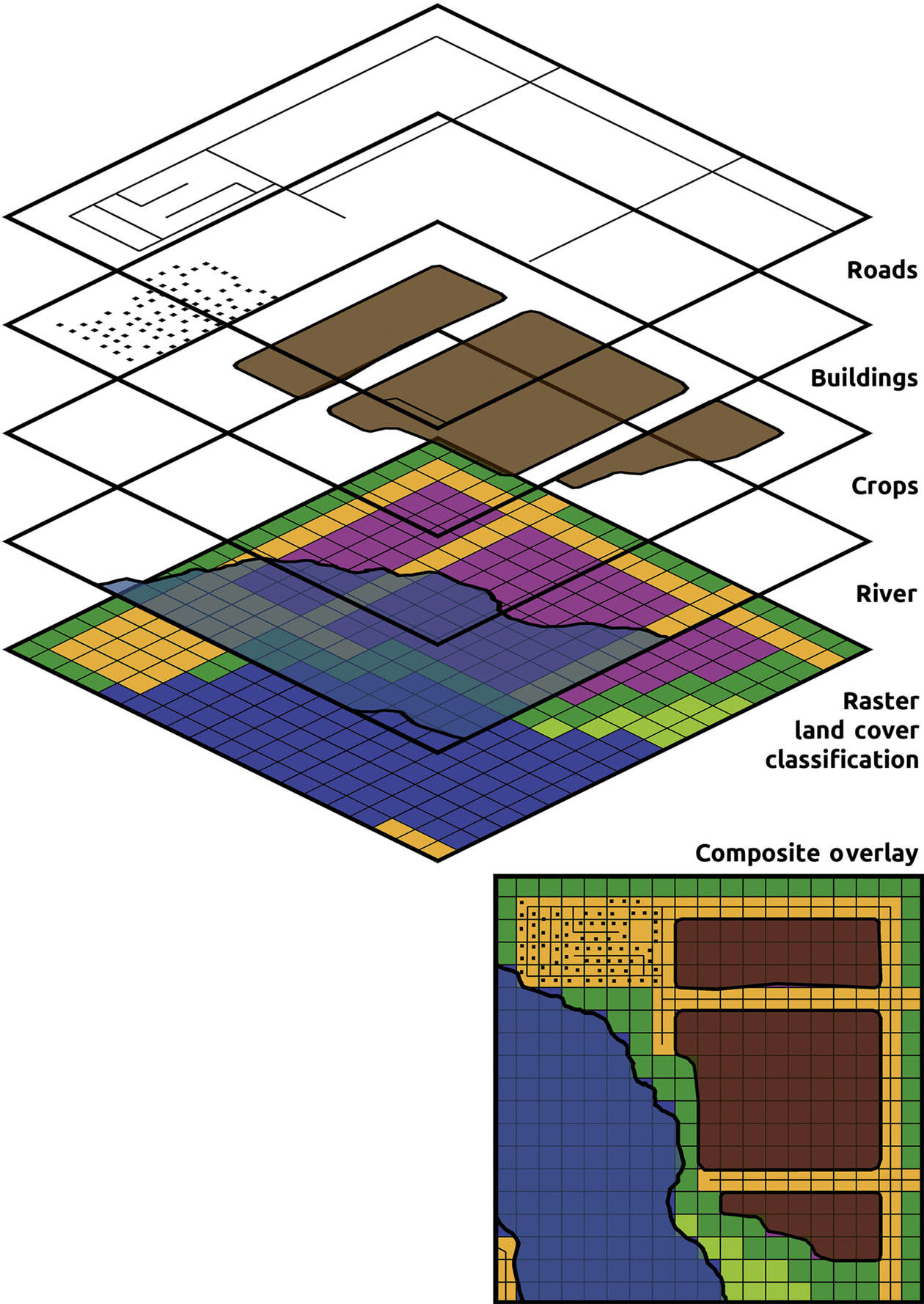

4.1 What is a Geographic Information System?

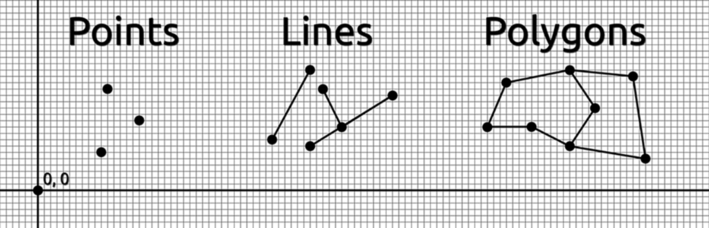

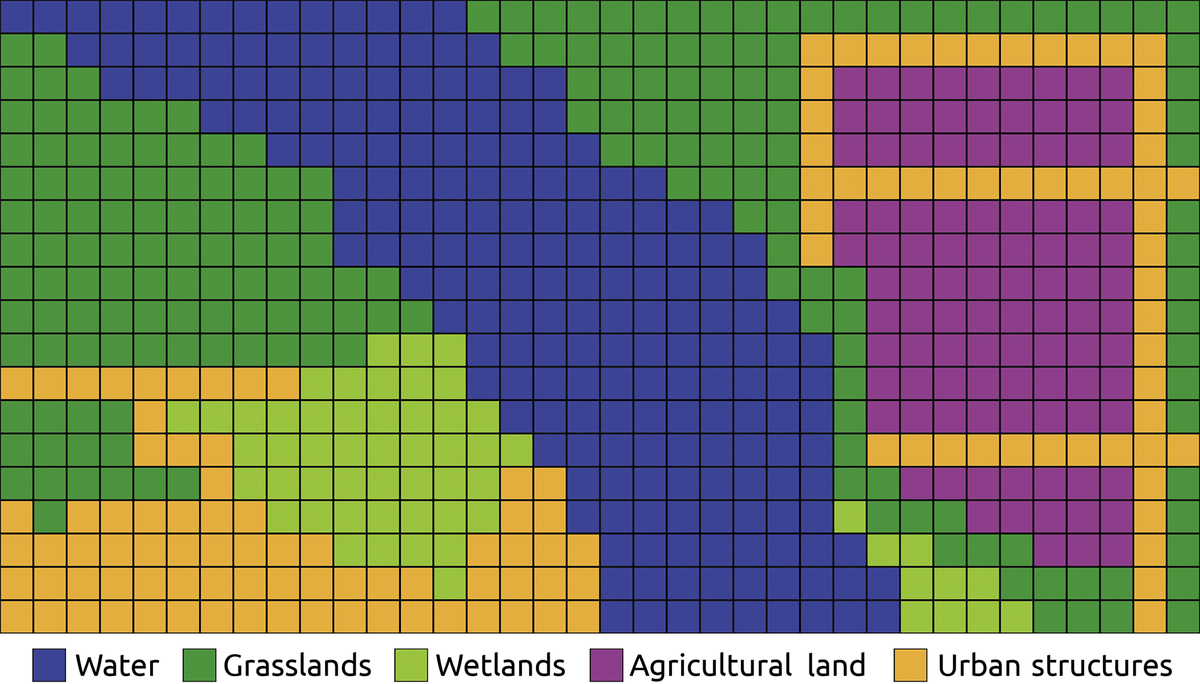

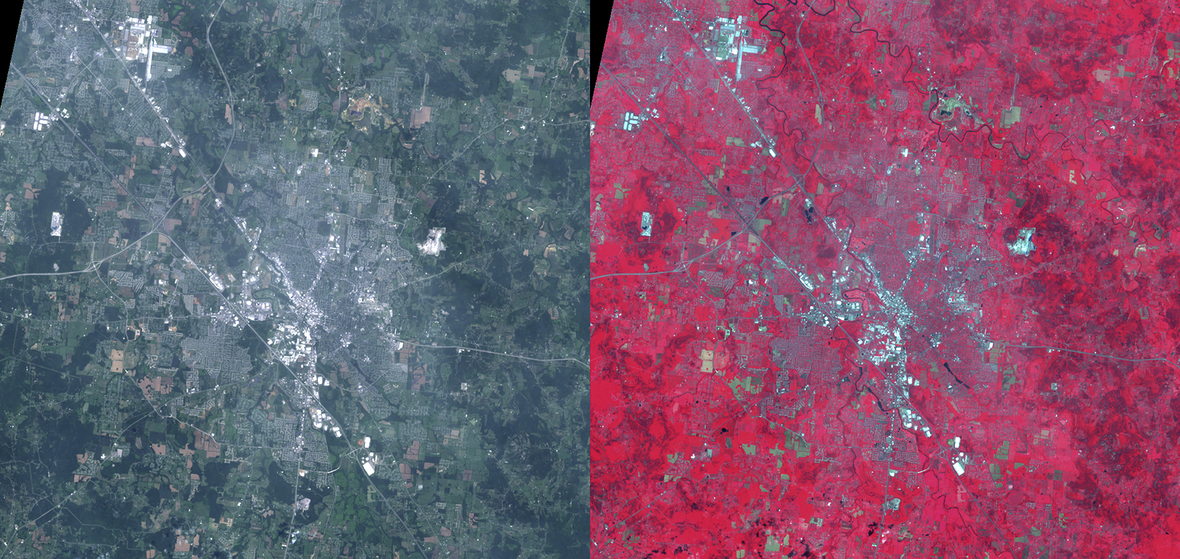

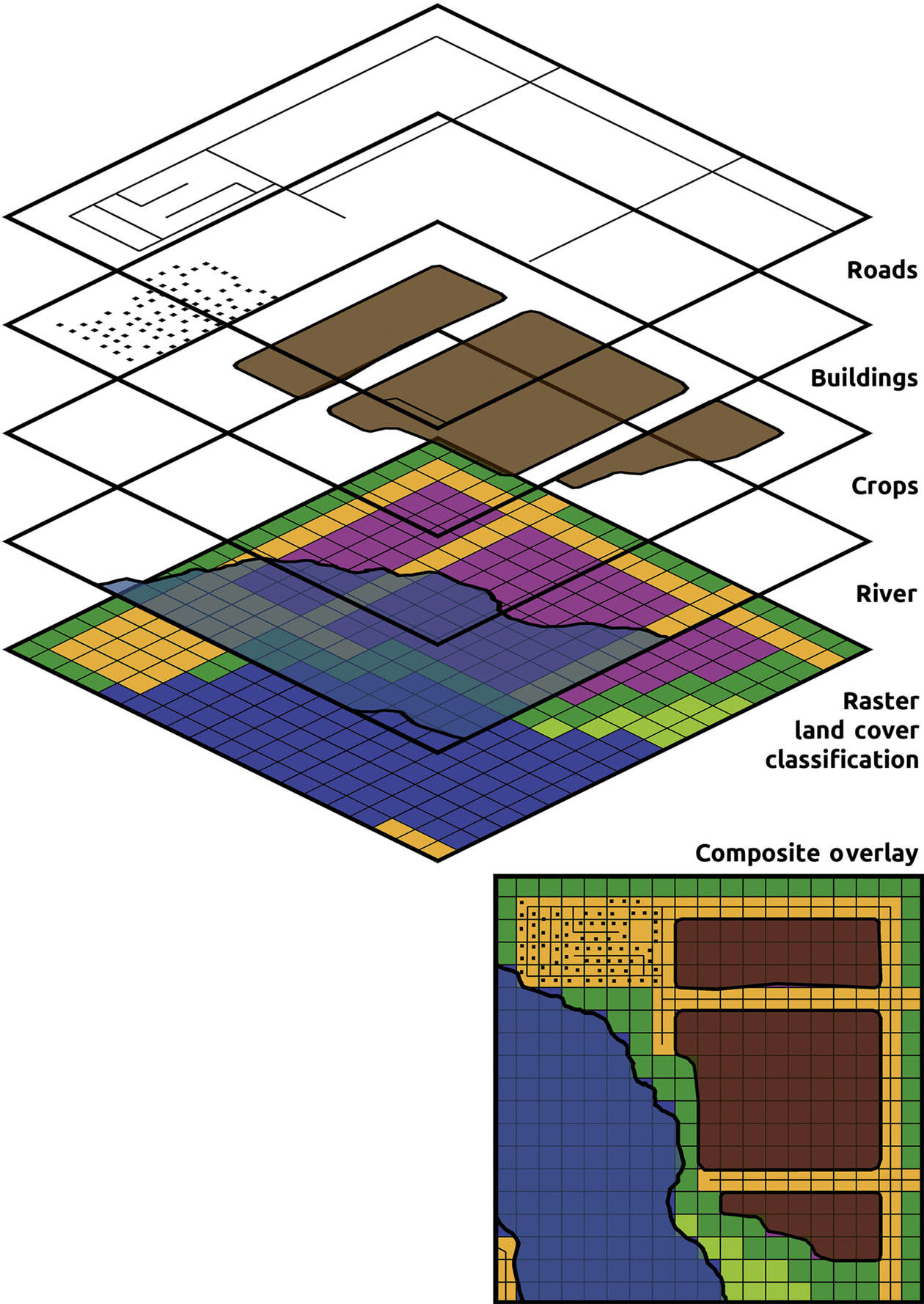

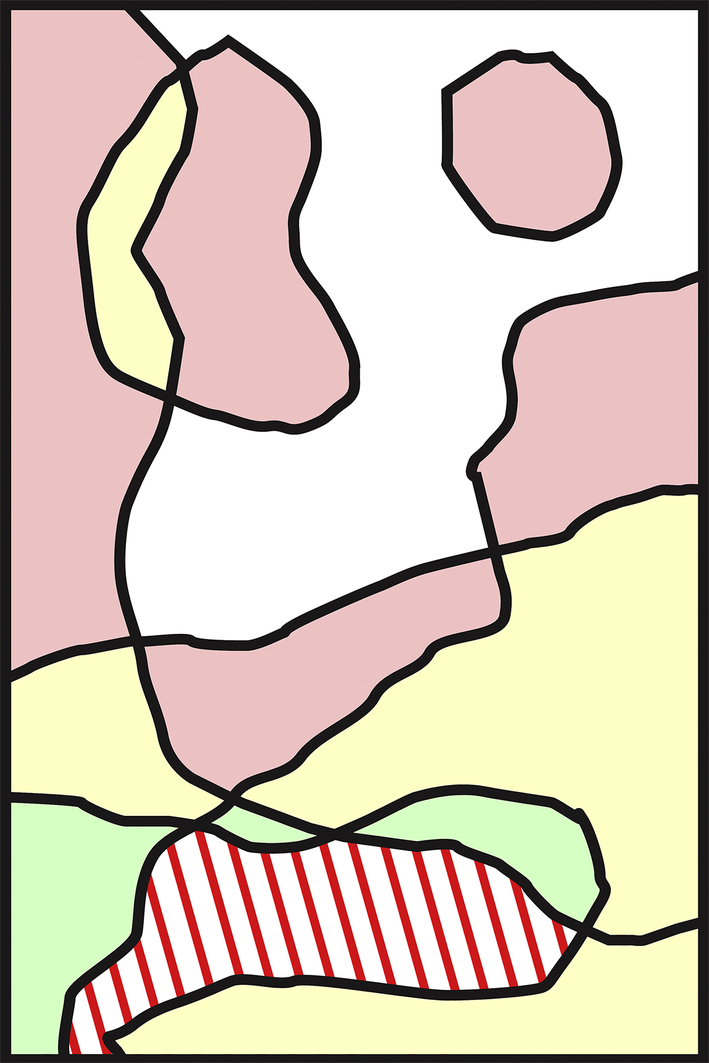

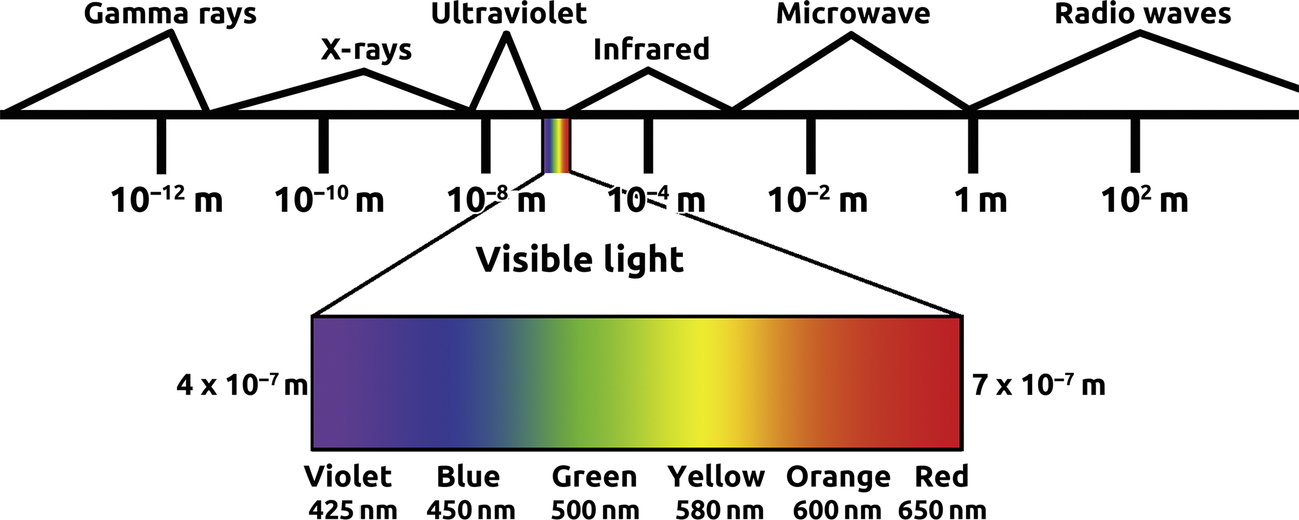

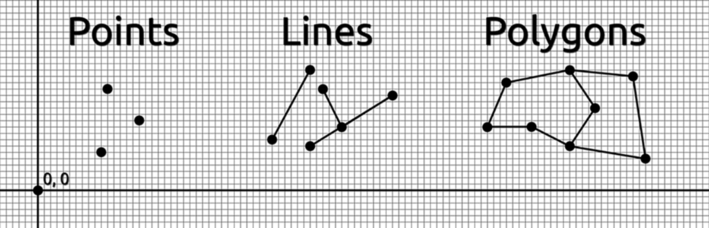

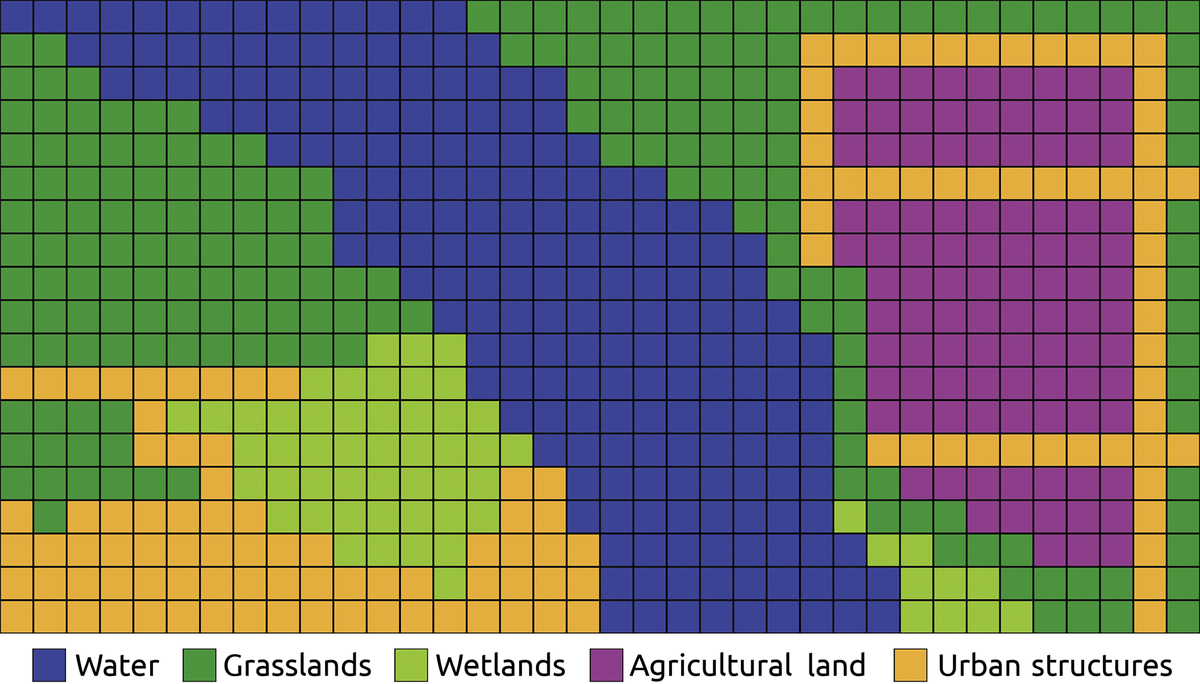

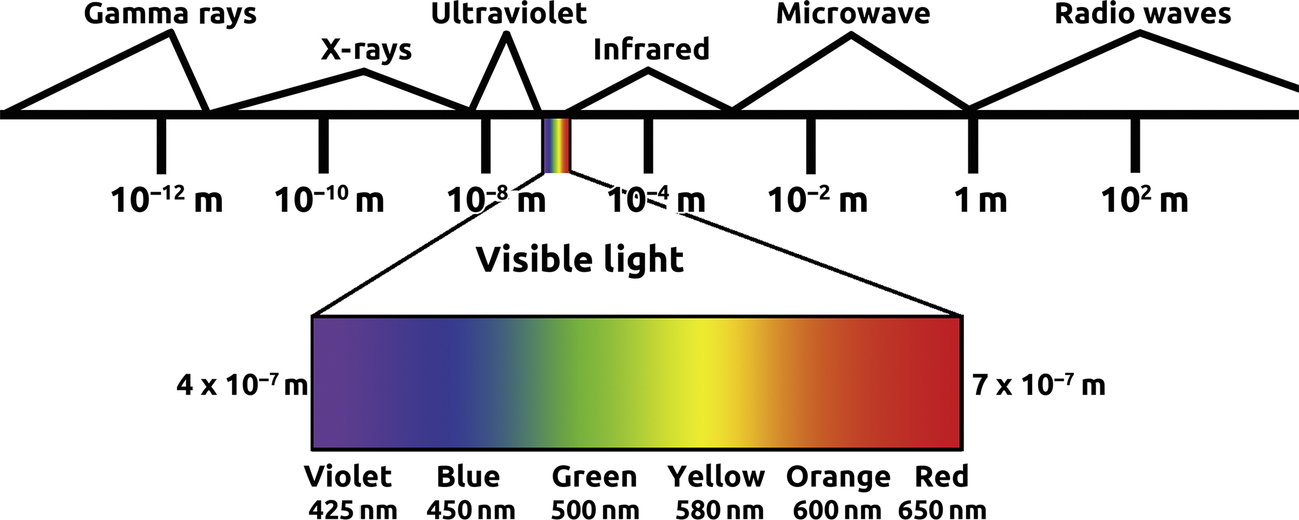

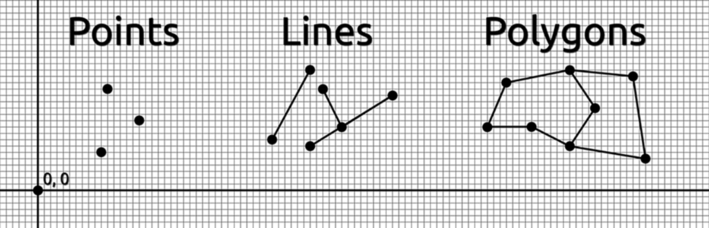

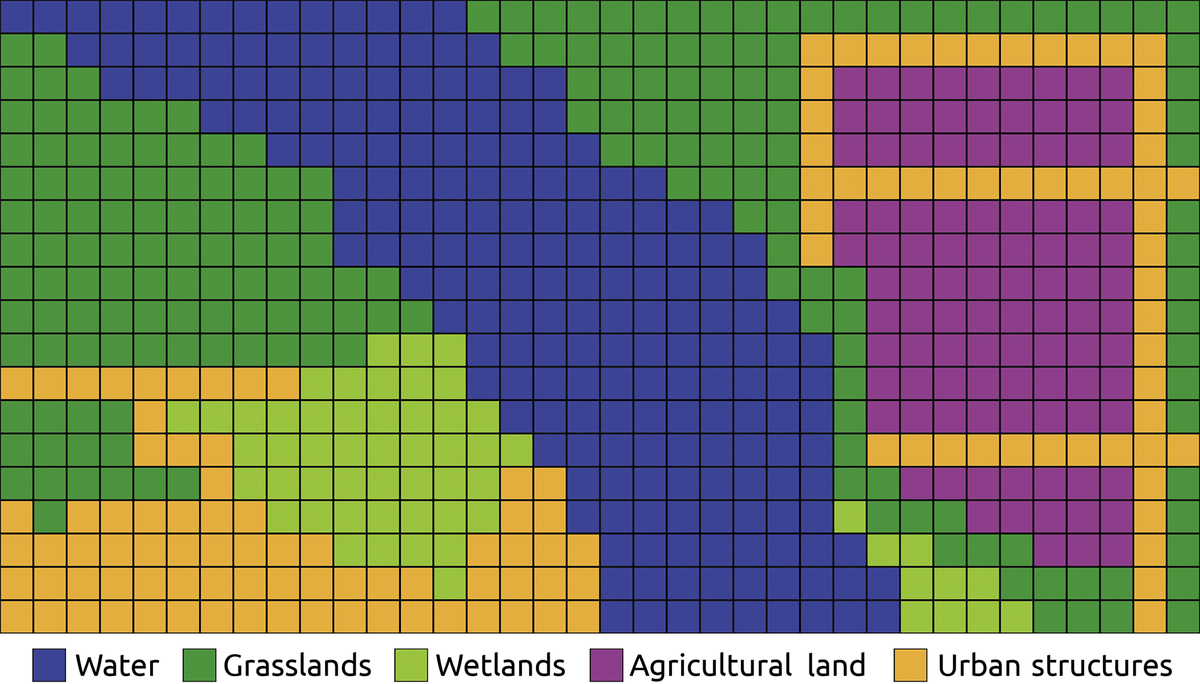

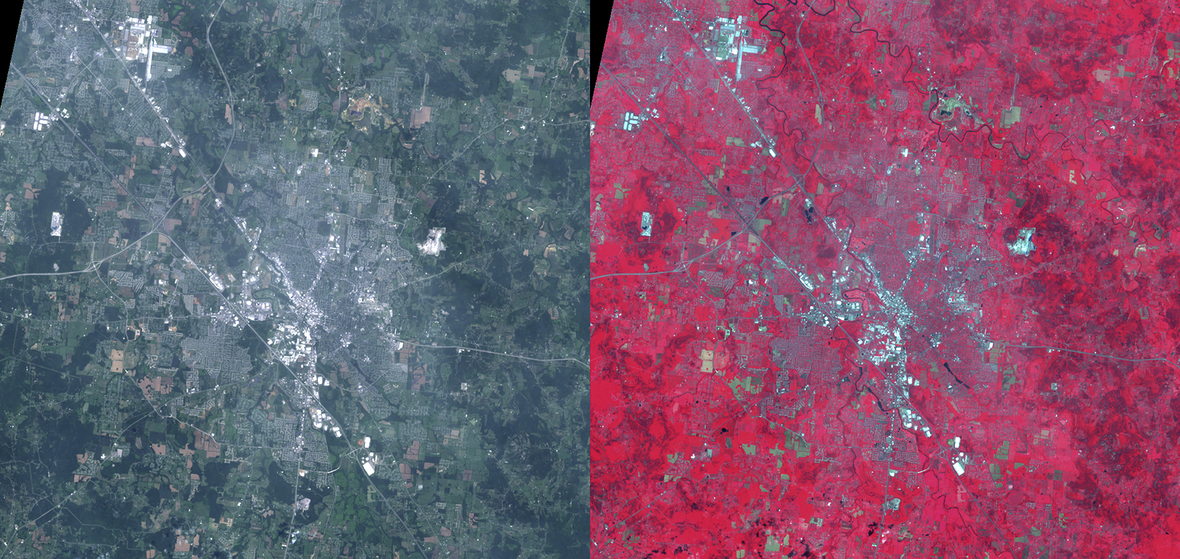

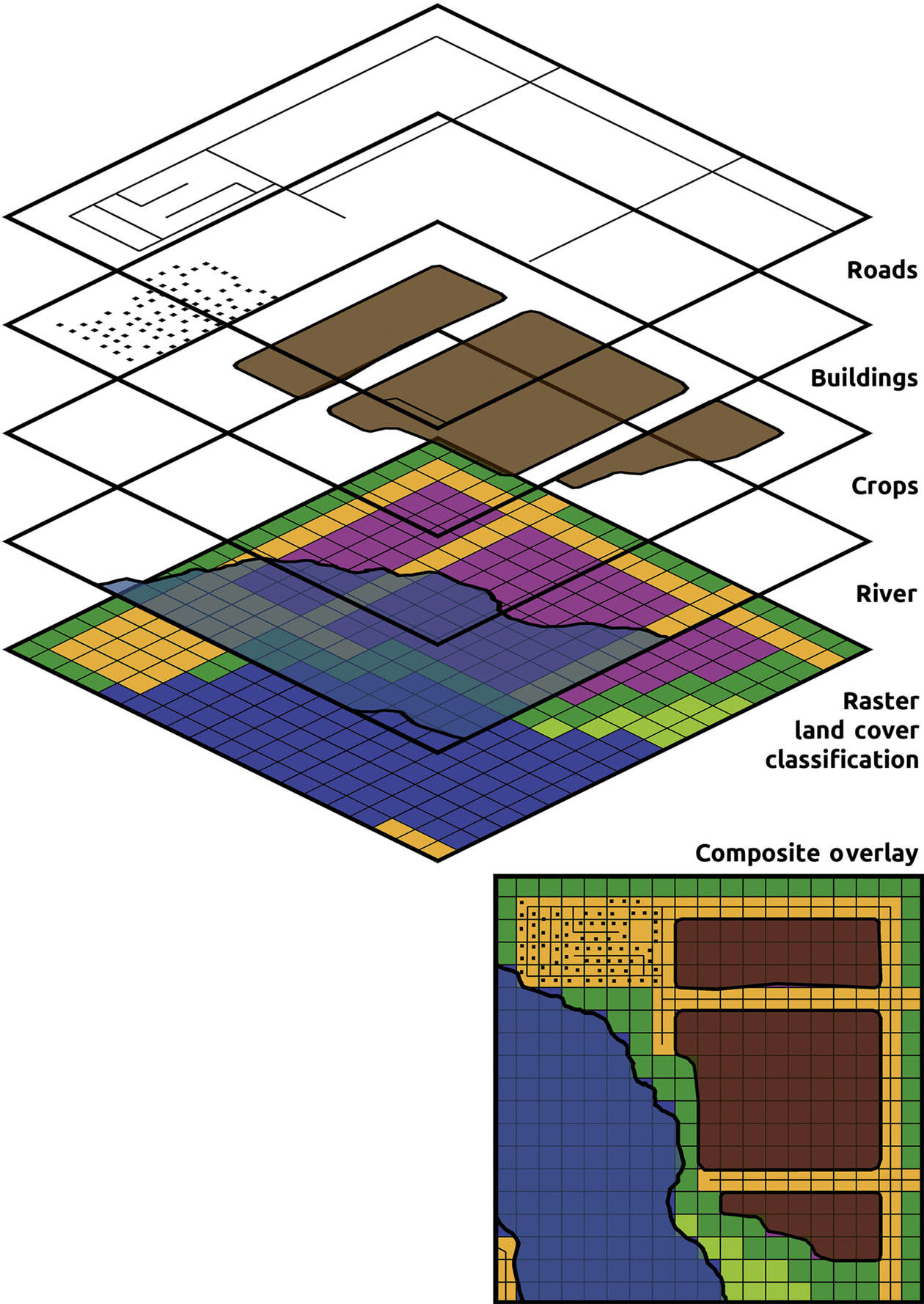

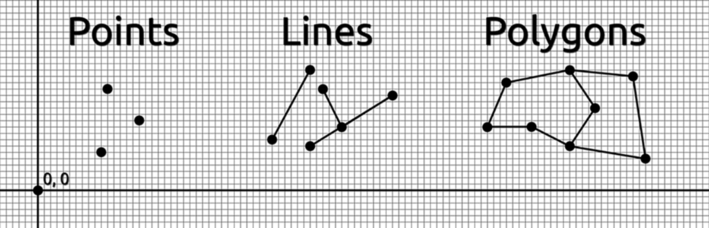

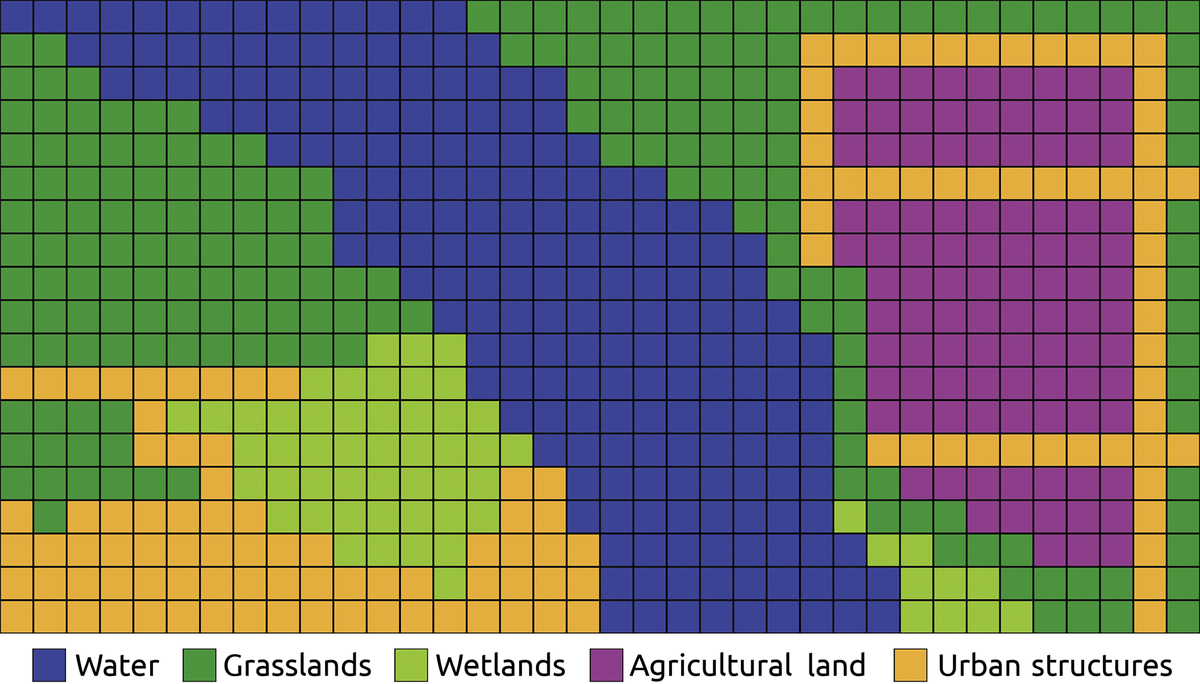

4.4 The Difference Between Vector and Raster Data

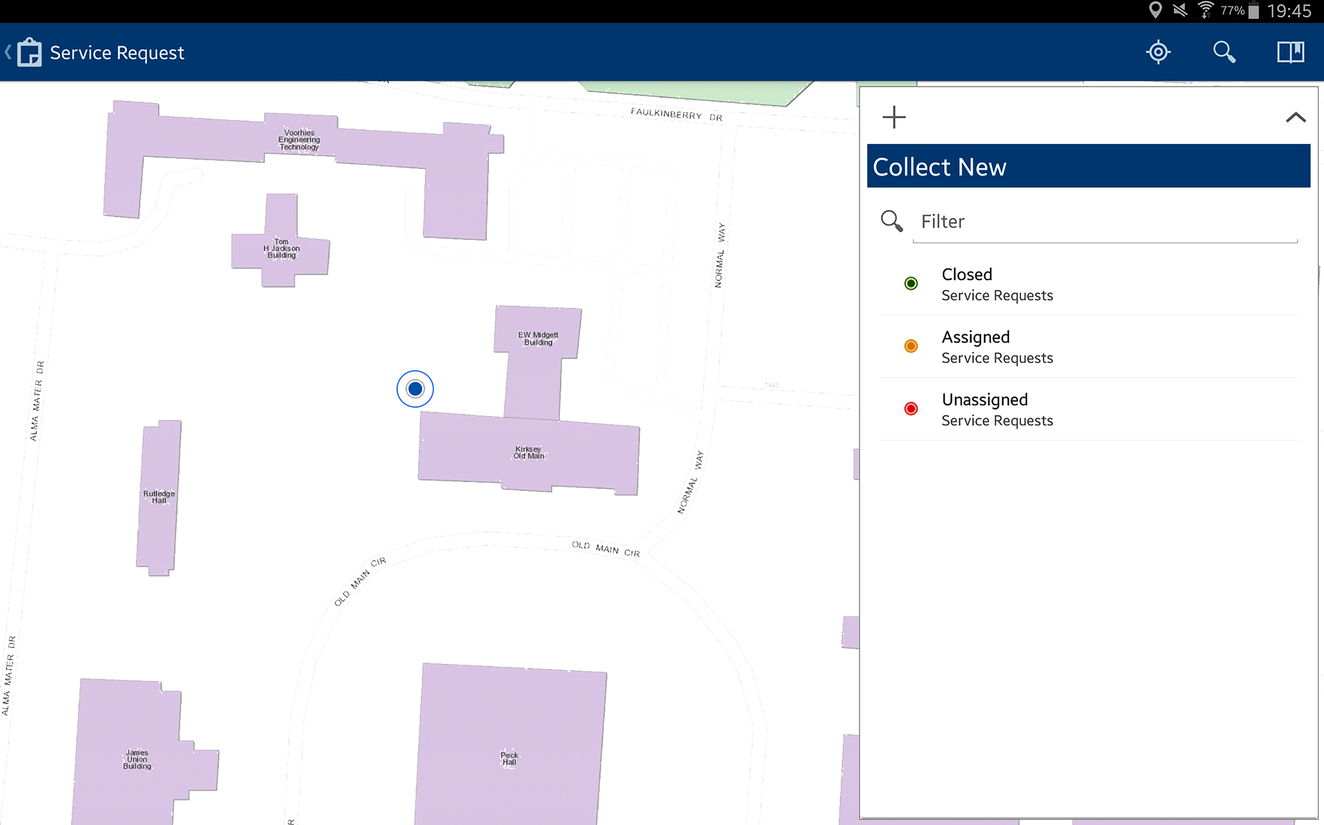

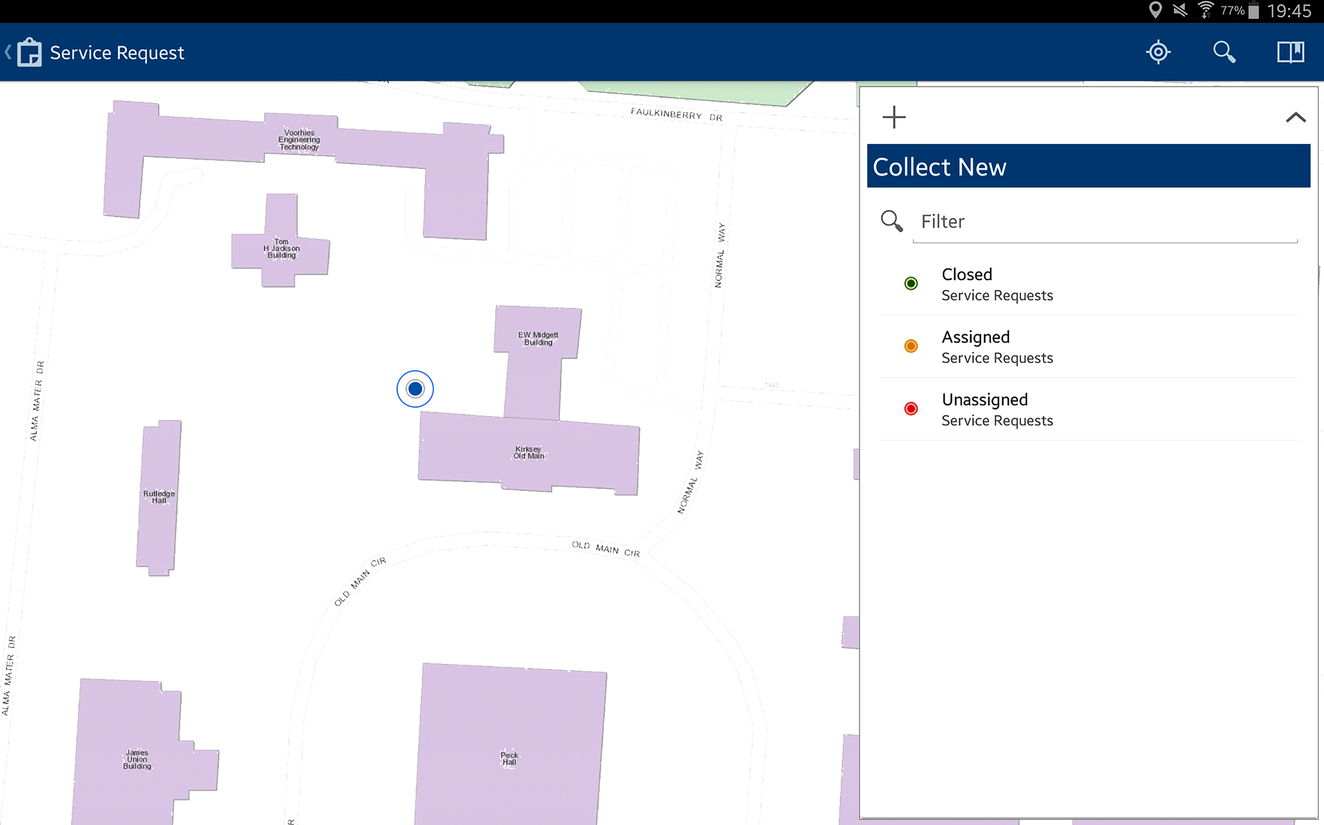

4.6 Web GIS as a Component of NeoGeography

4.7 Volunteered Geographic Information

Chapter 5: Terrain Mapping Meets Digital Data

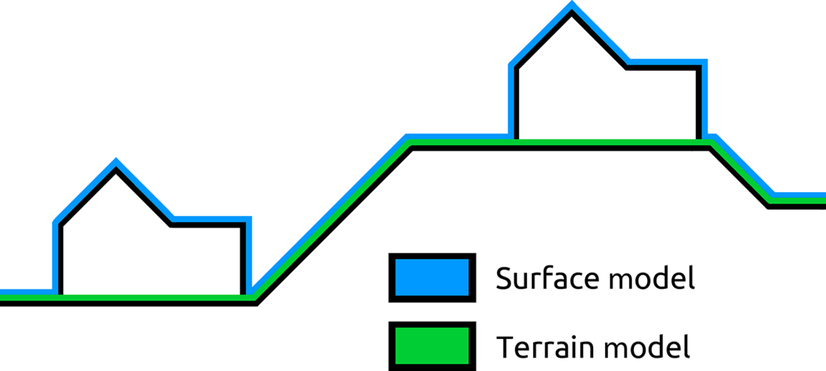

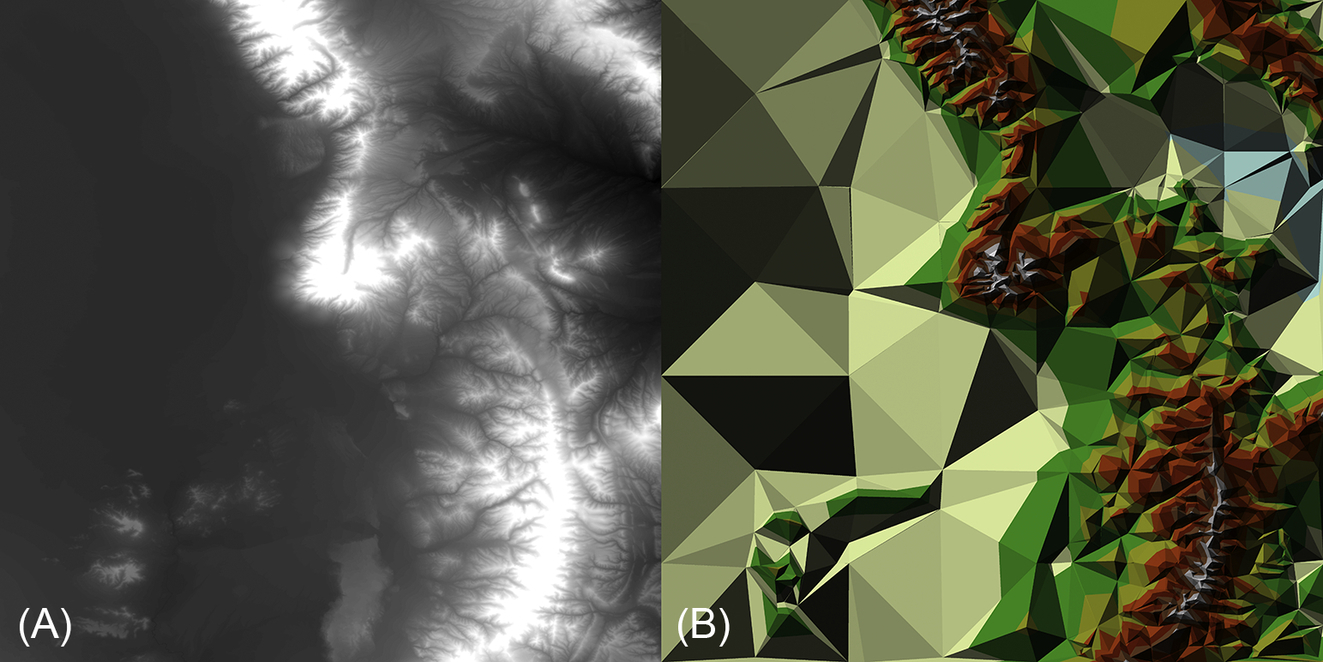

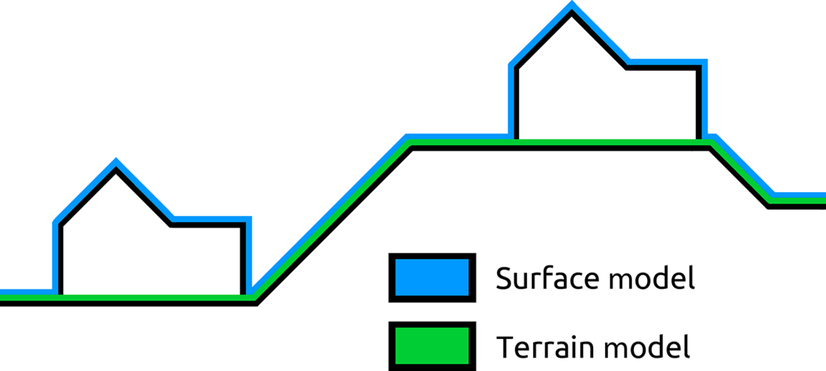

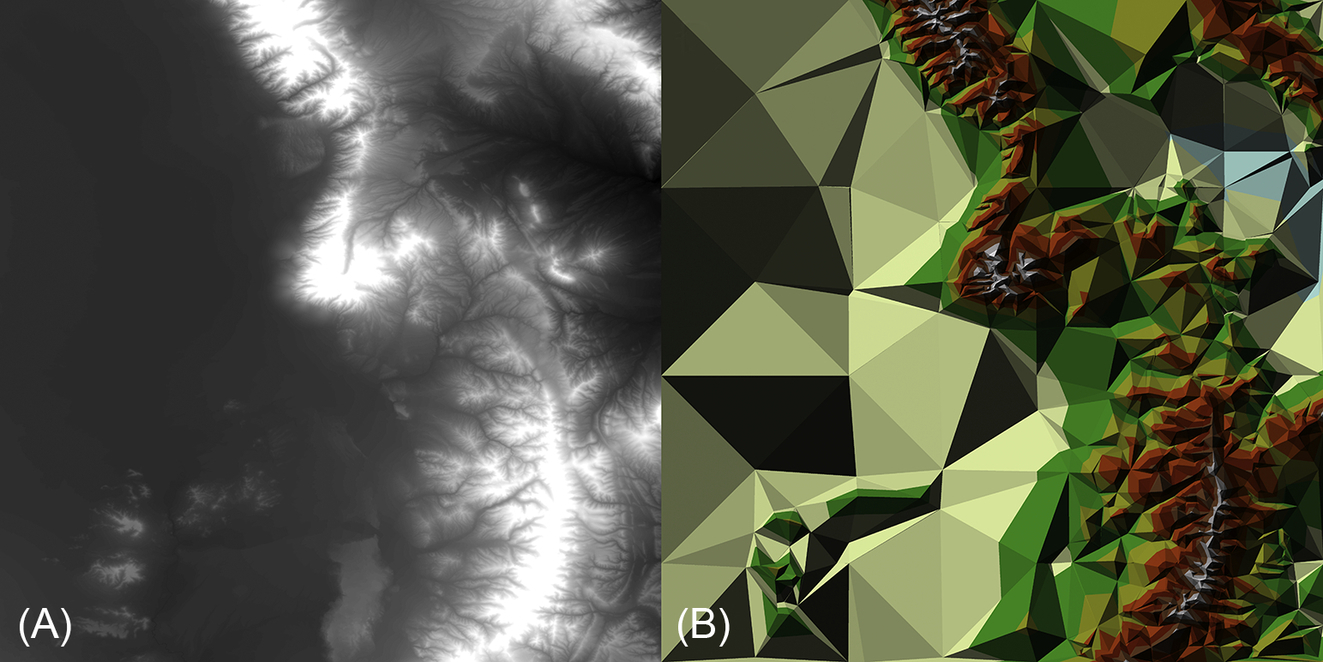

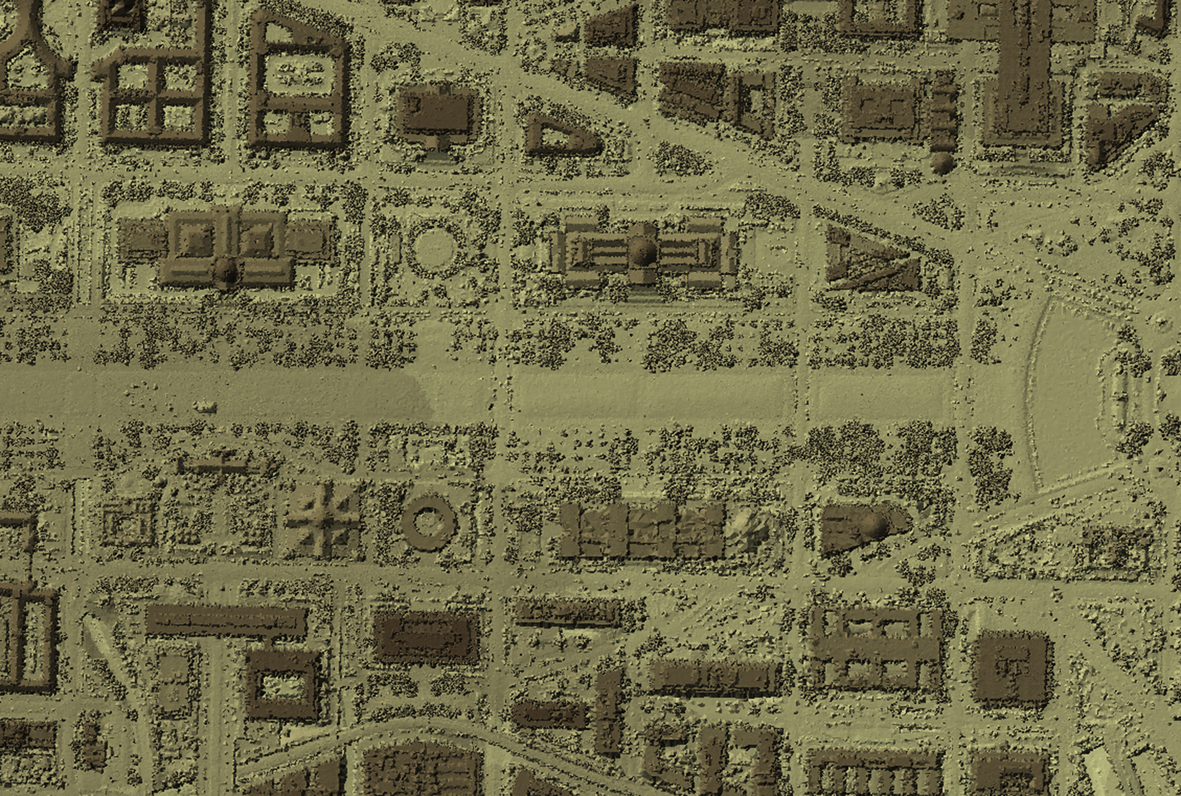

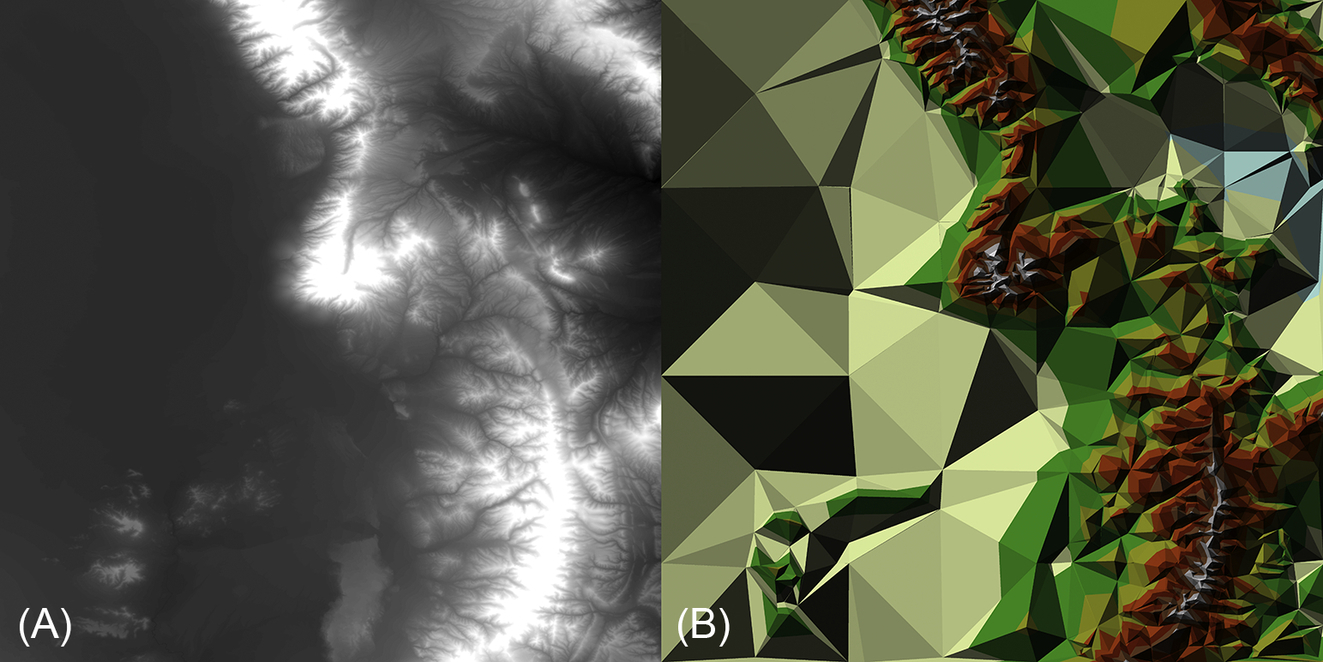

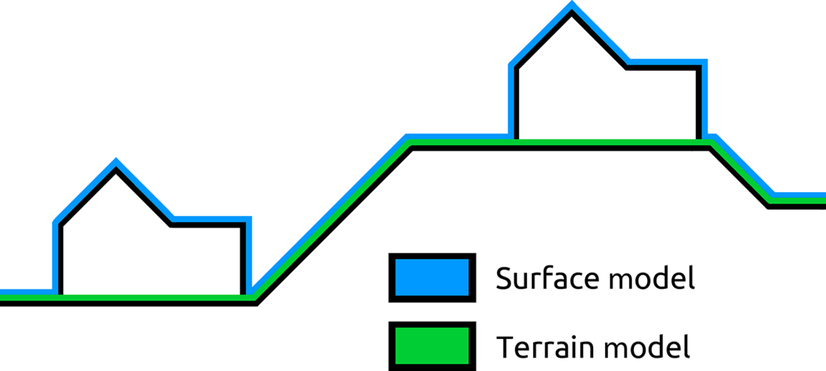

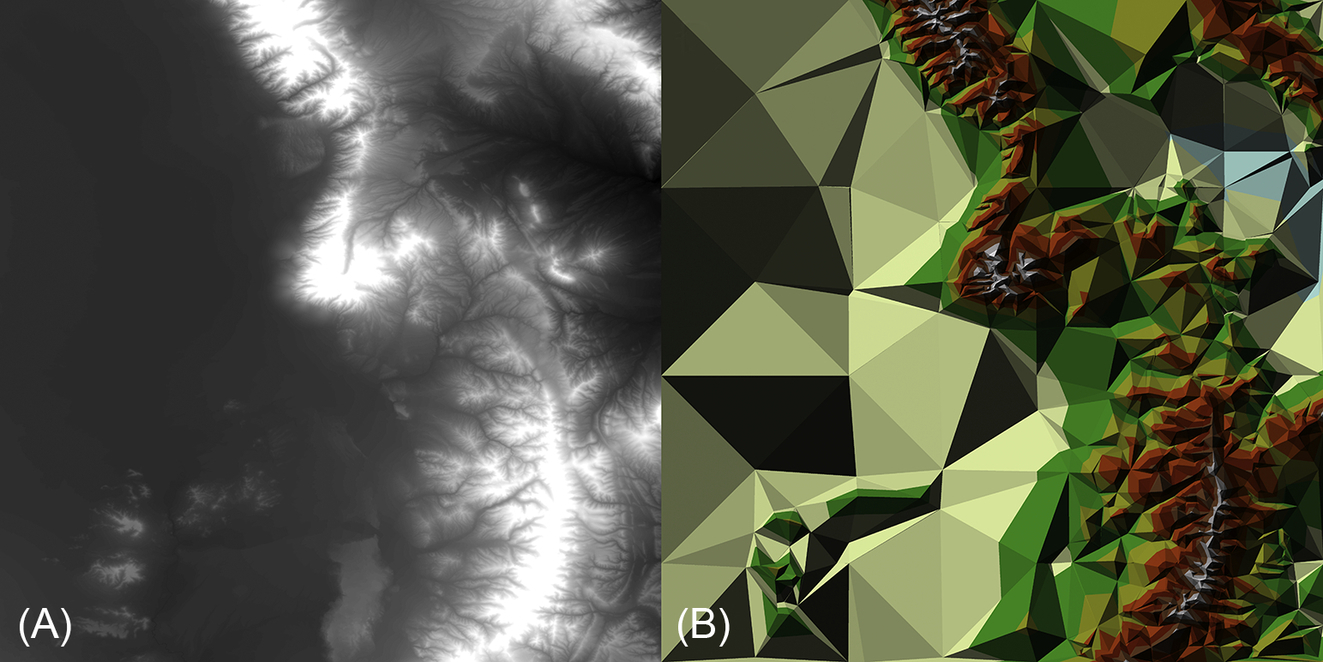

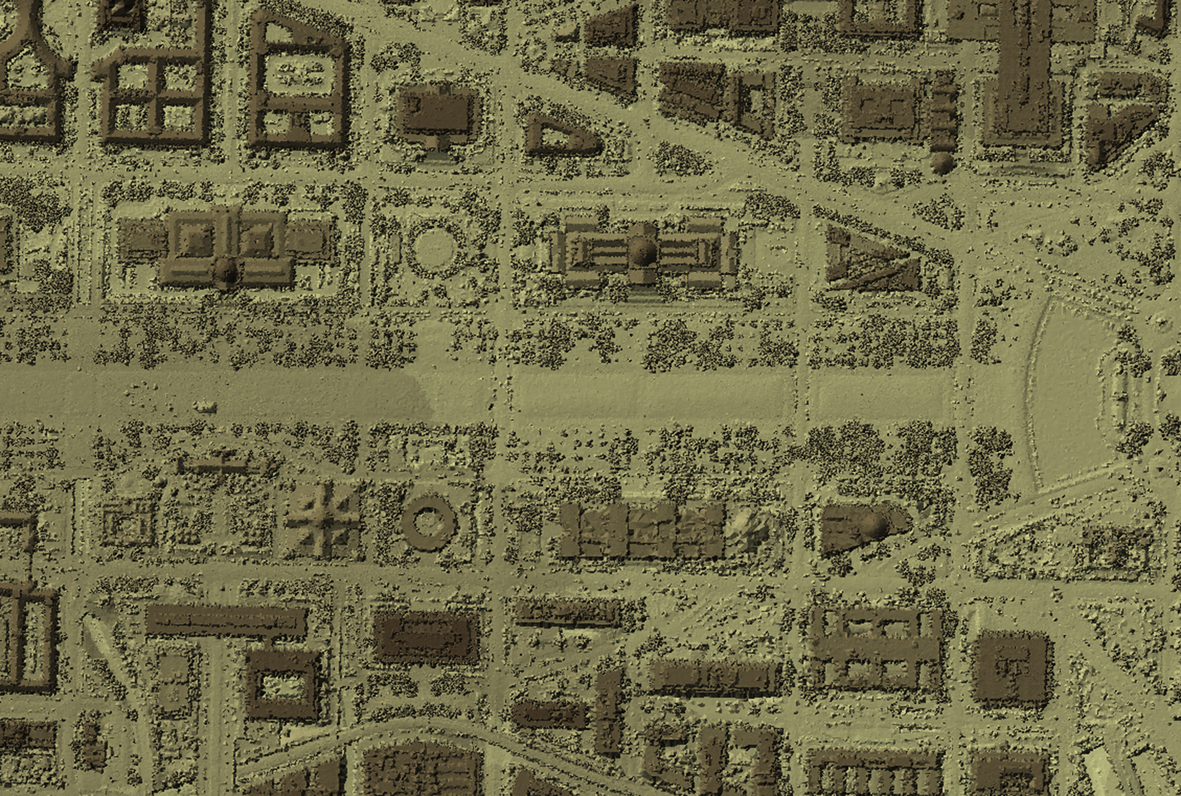

5.1 Digitally Representing Terrain

Chapter 6: Map and Geospatial Librarianship

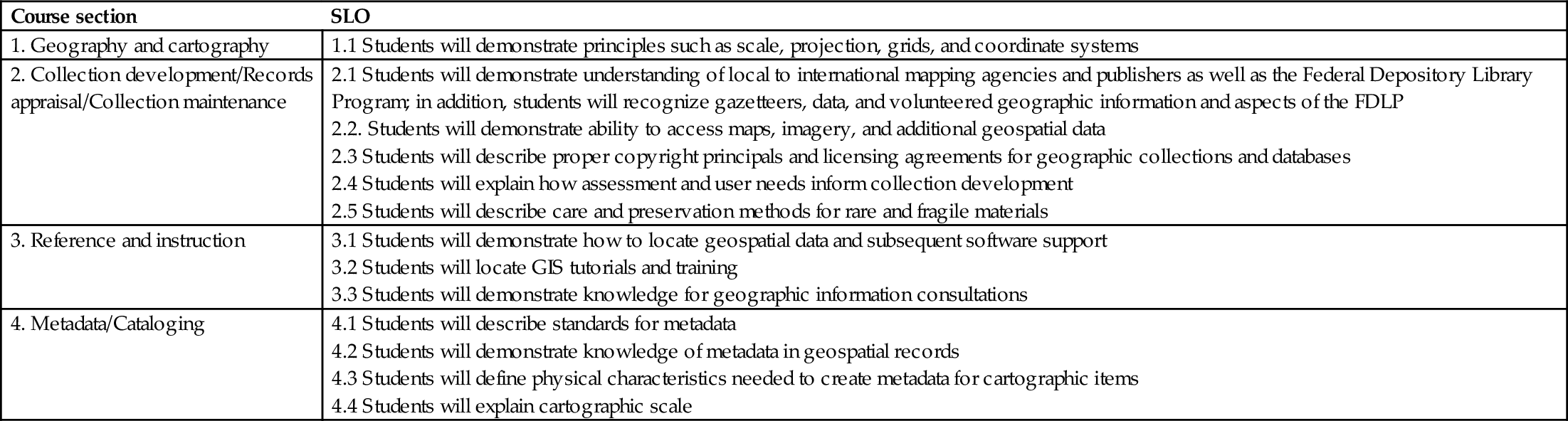

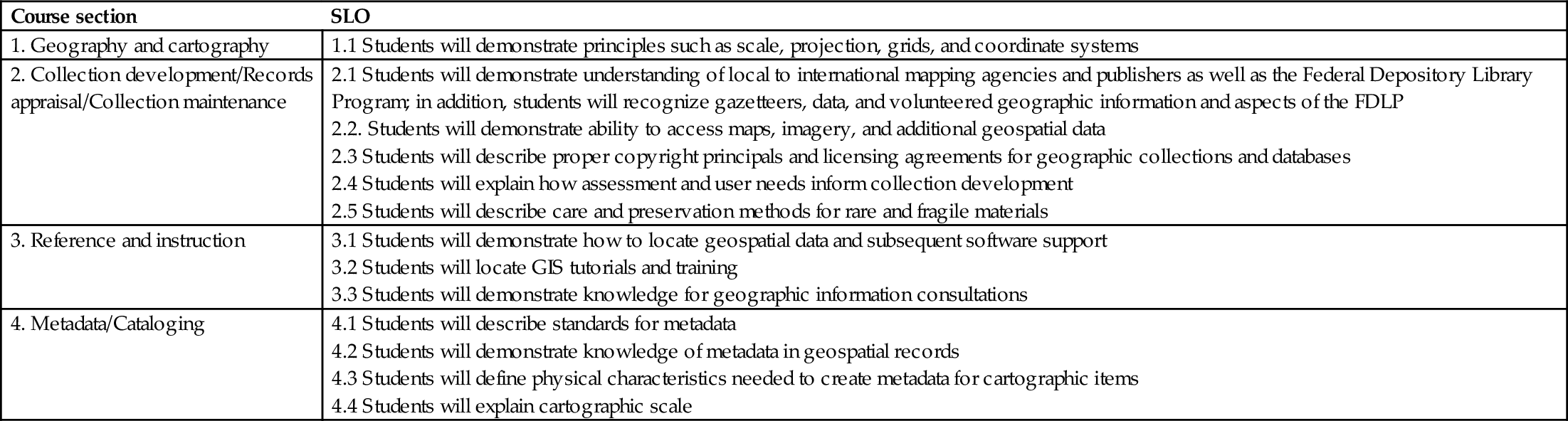

6.2 Academic Preparation and Continuing Education

6.3 History and Transitions in Map and Geospatial Librarianship

6.4 GeoWeb and Geospatial Librarianship

6.5 Historical Beginnings—ALA and MAGIRT

6.6 Core Competencies: ALA and MAGIRT

6.7 History of Academic Curriculum to Support Map Librarianship

6.8 Transitions in Academic Curriculum to Support Map Librarianship

6.9 Job Opportunities and Challenges in Map and Geospatial Librarianship

6.10 Map Library Work Space and Equipment

Chapter 7: Geospatial Resources and Instruction Services

7.2 Navigating the Labyrinth—Legal Considerations

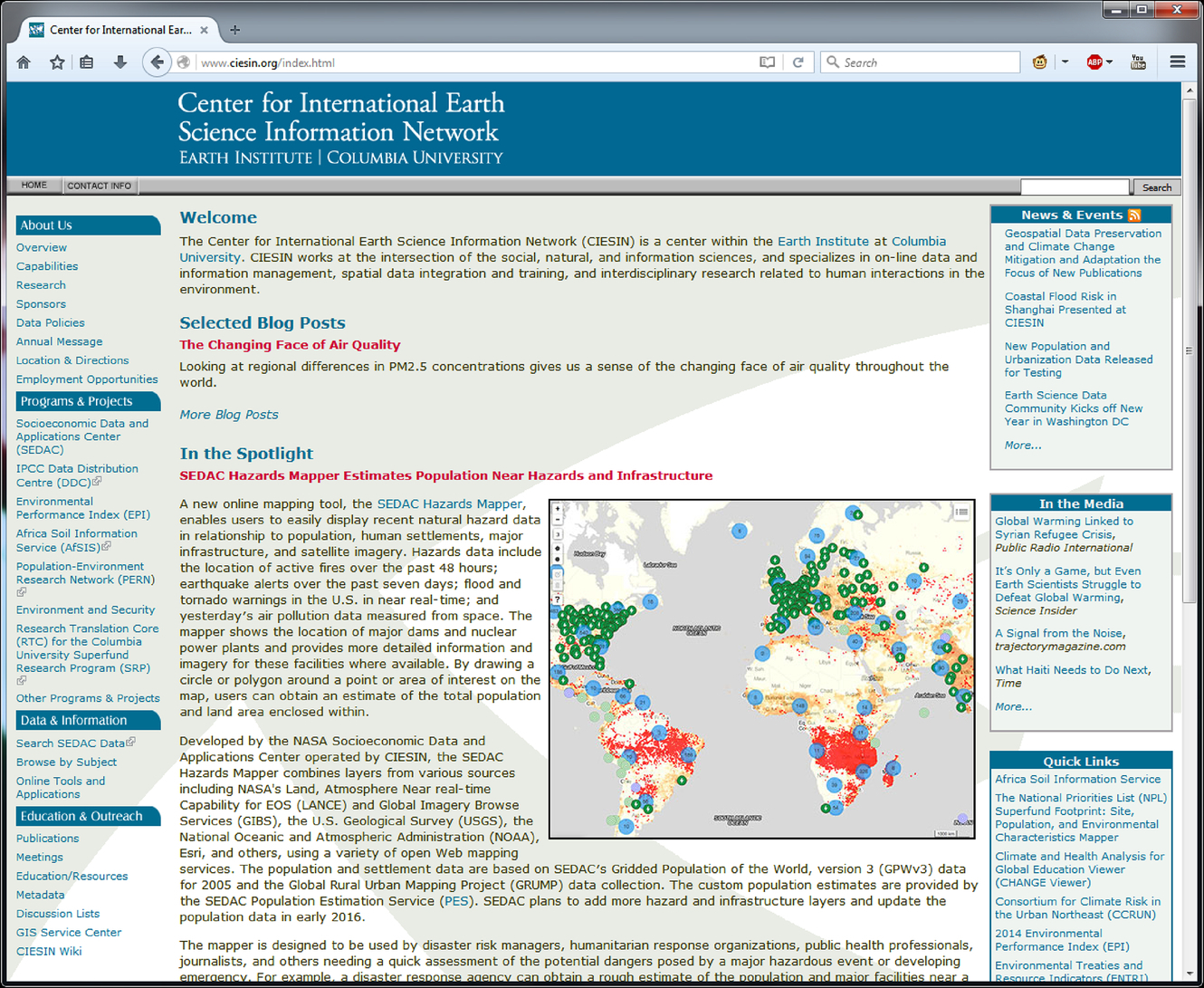

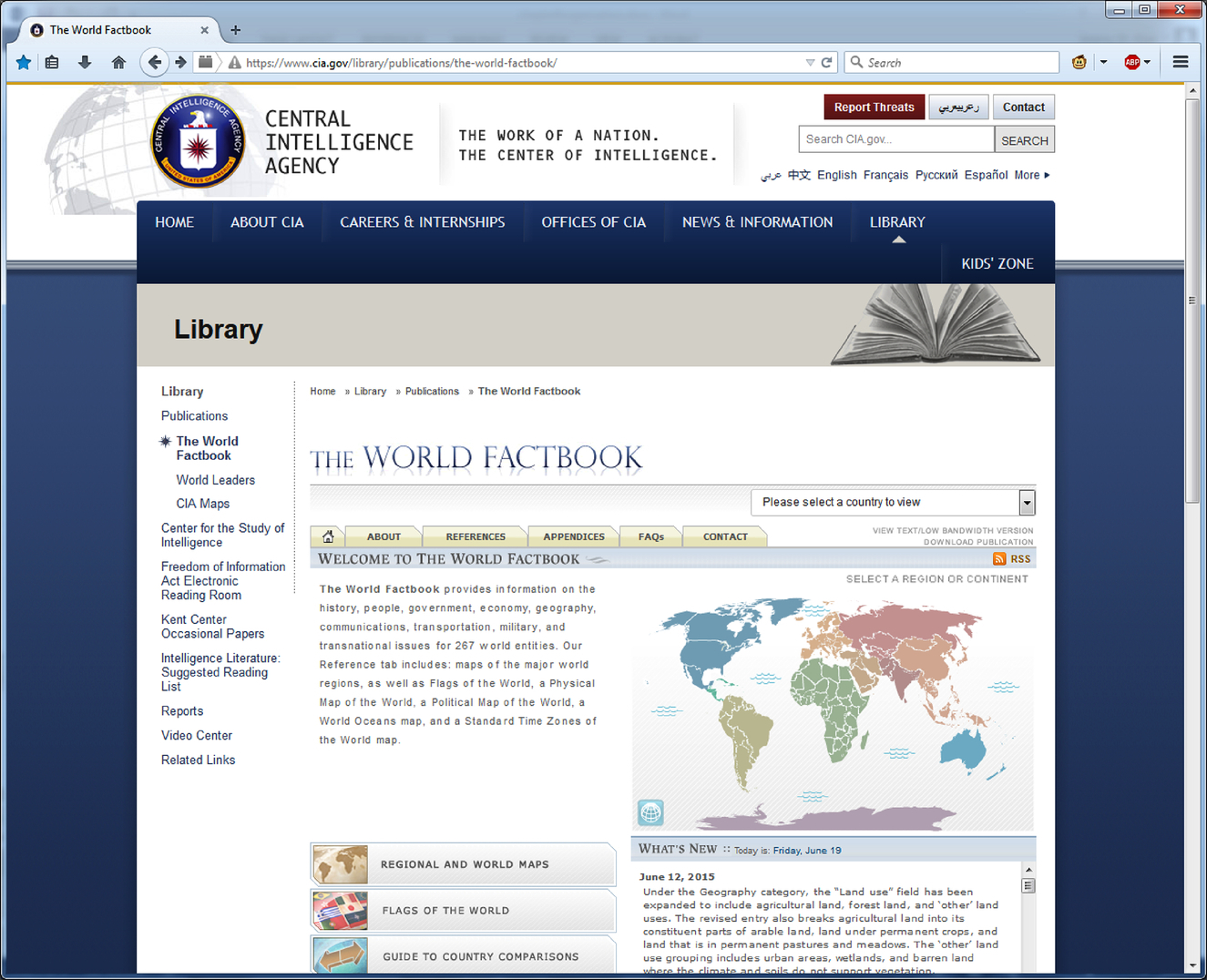

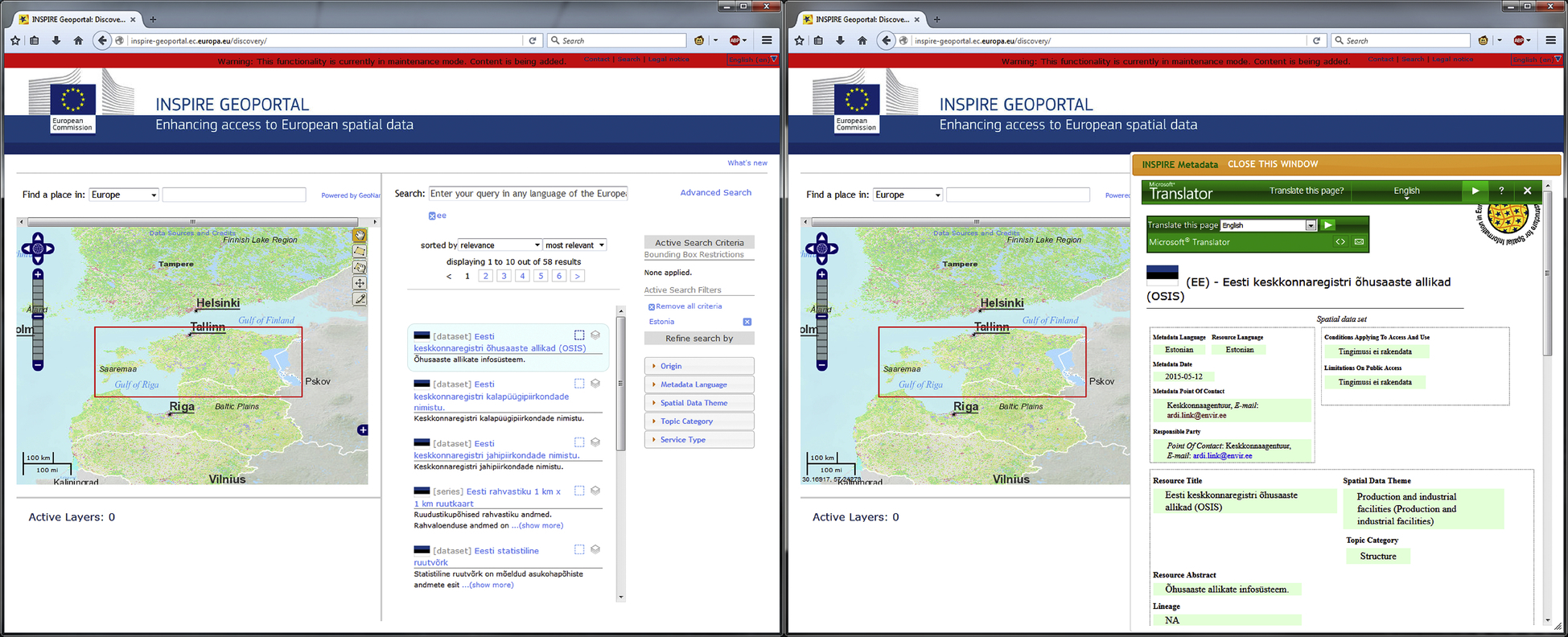

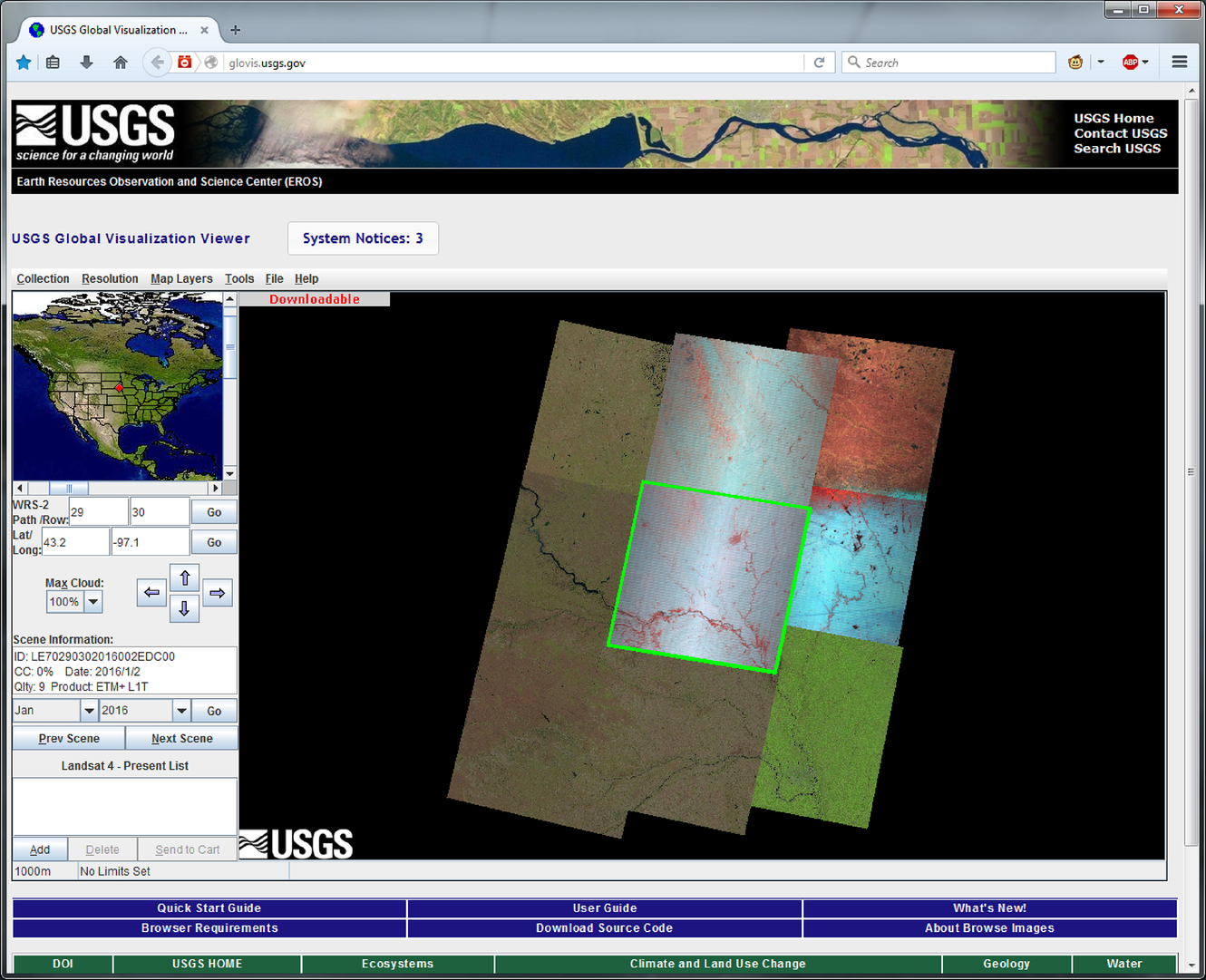

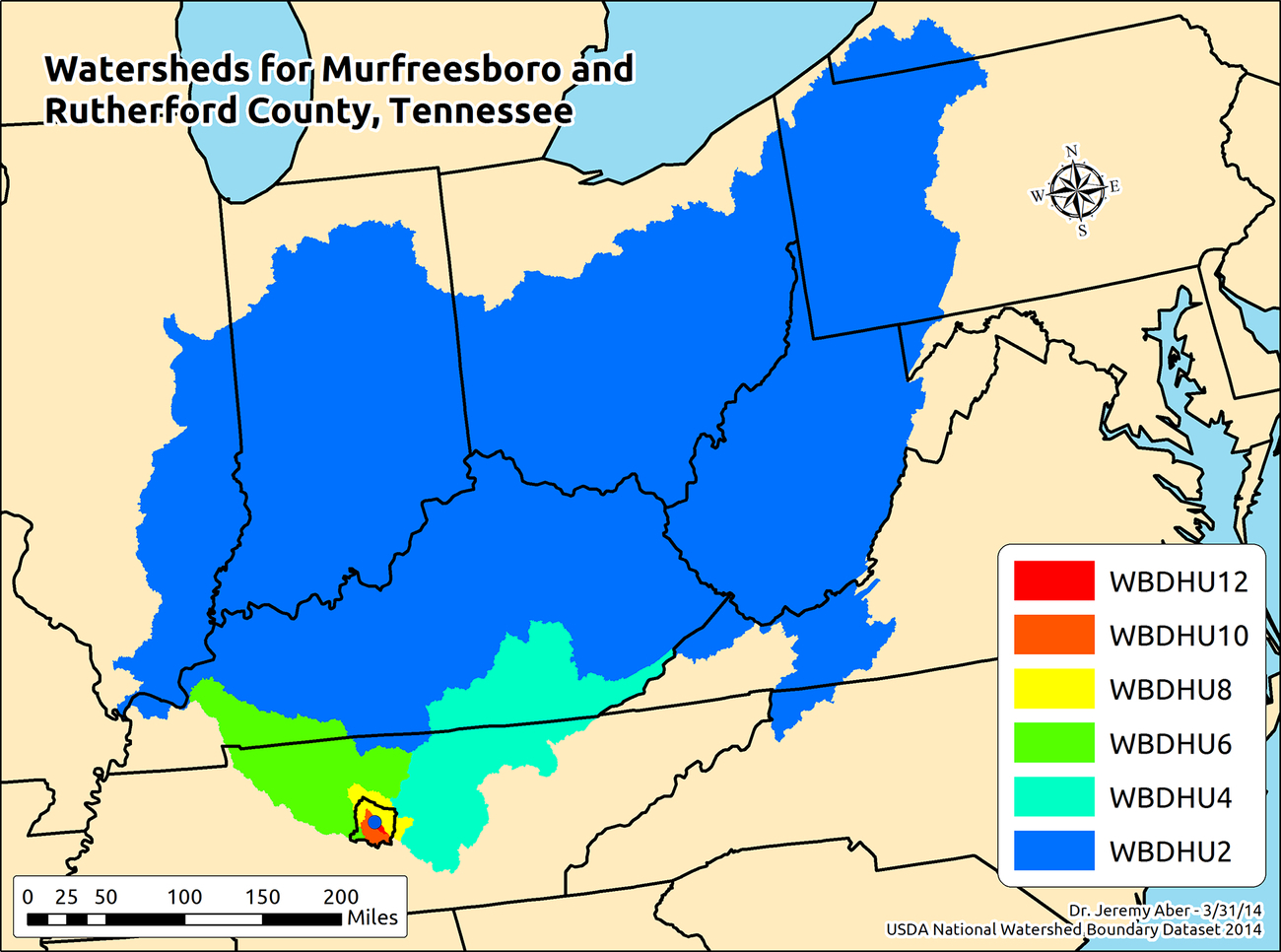

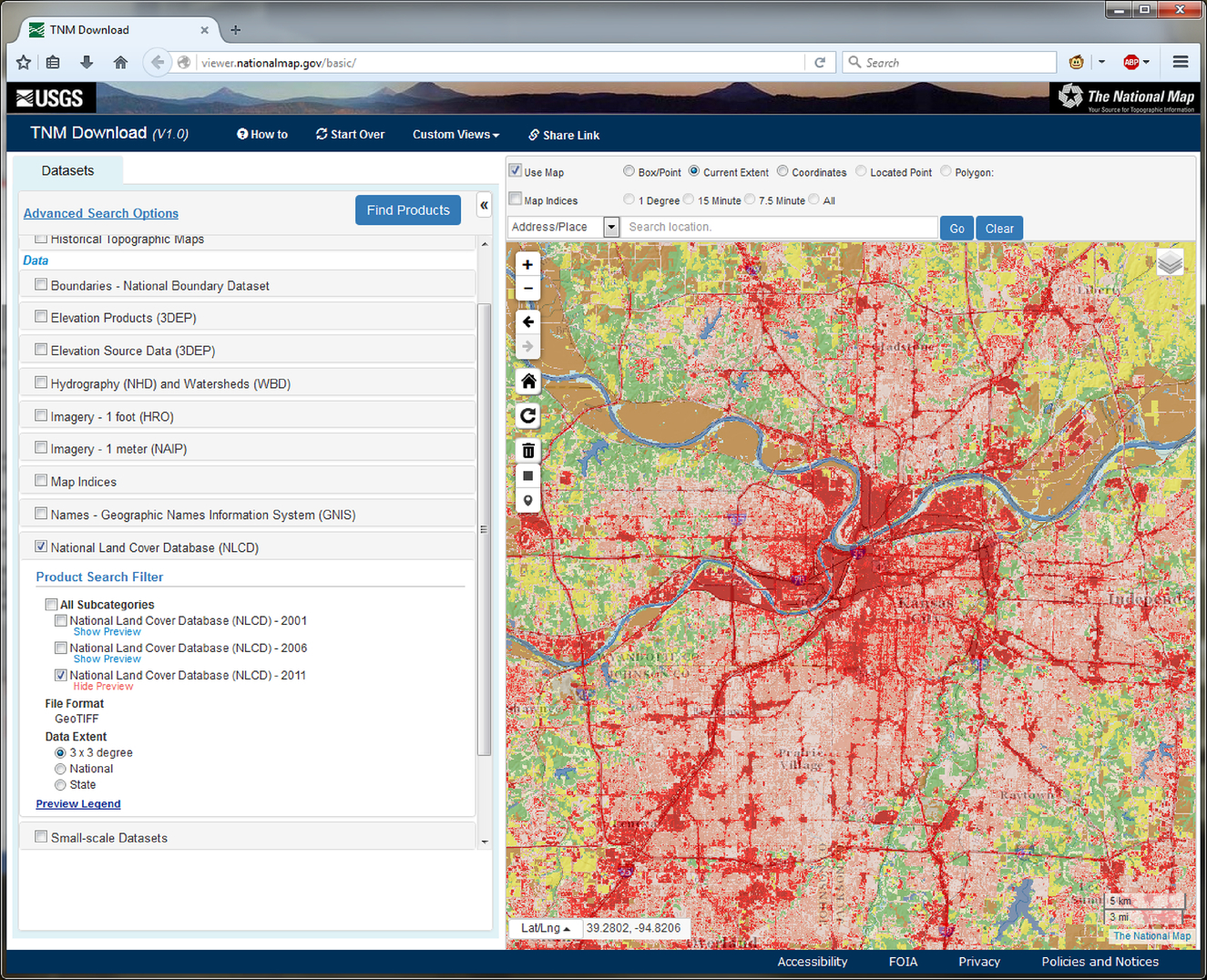

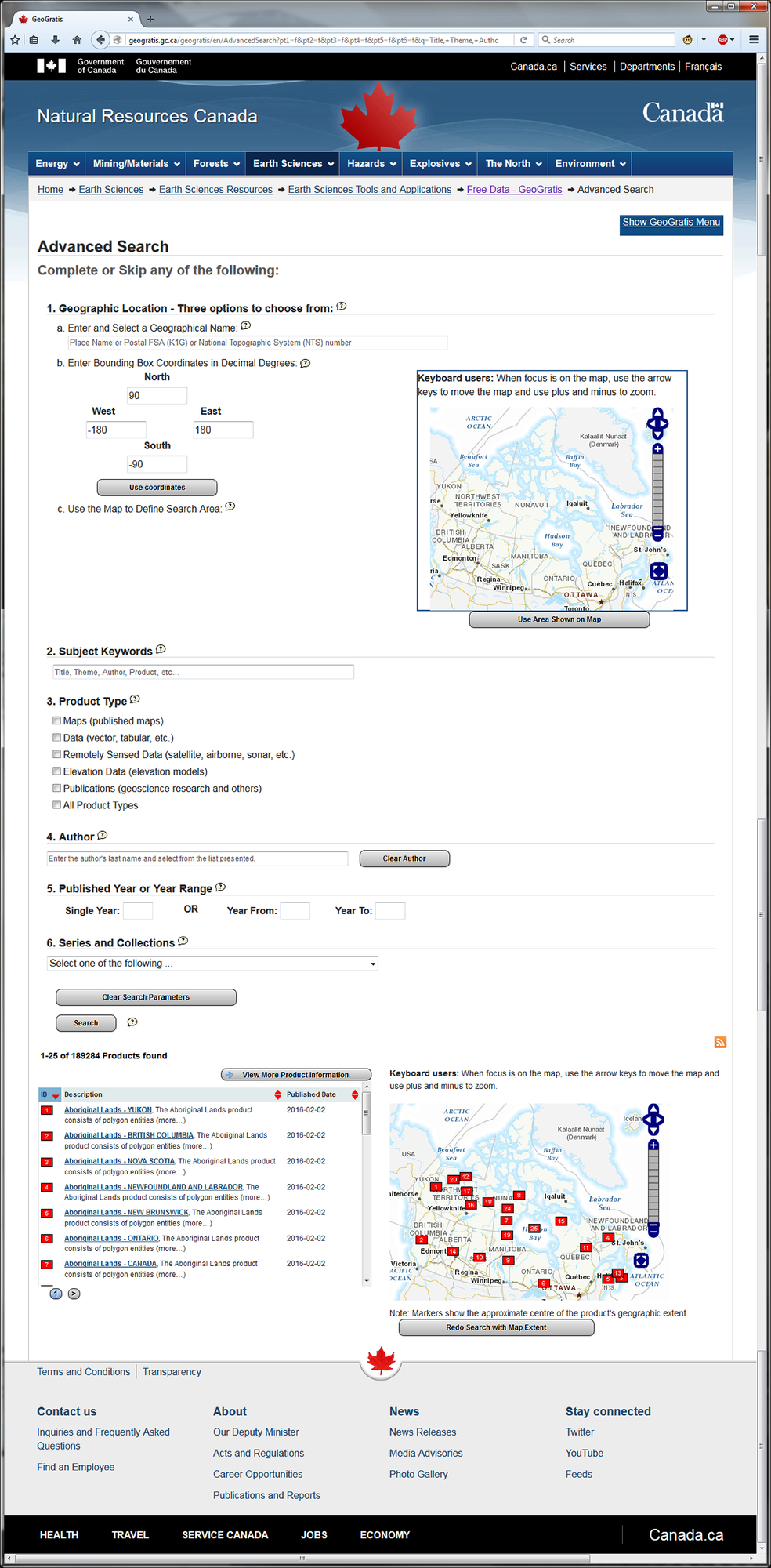

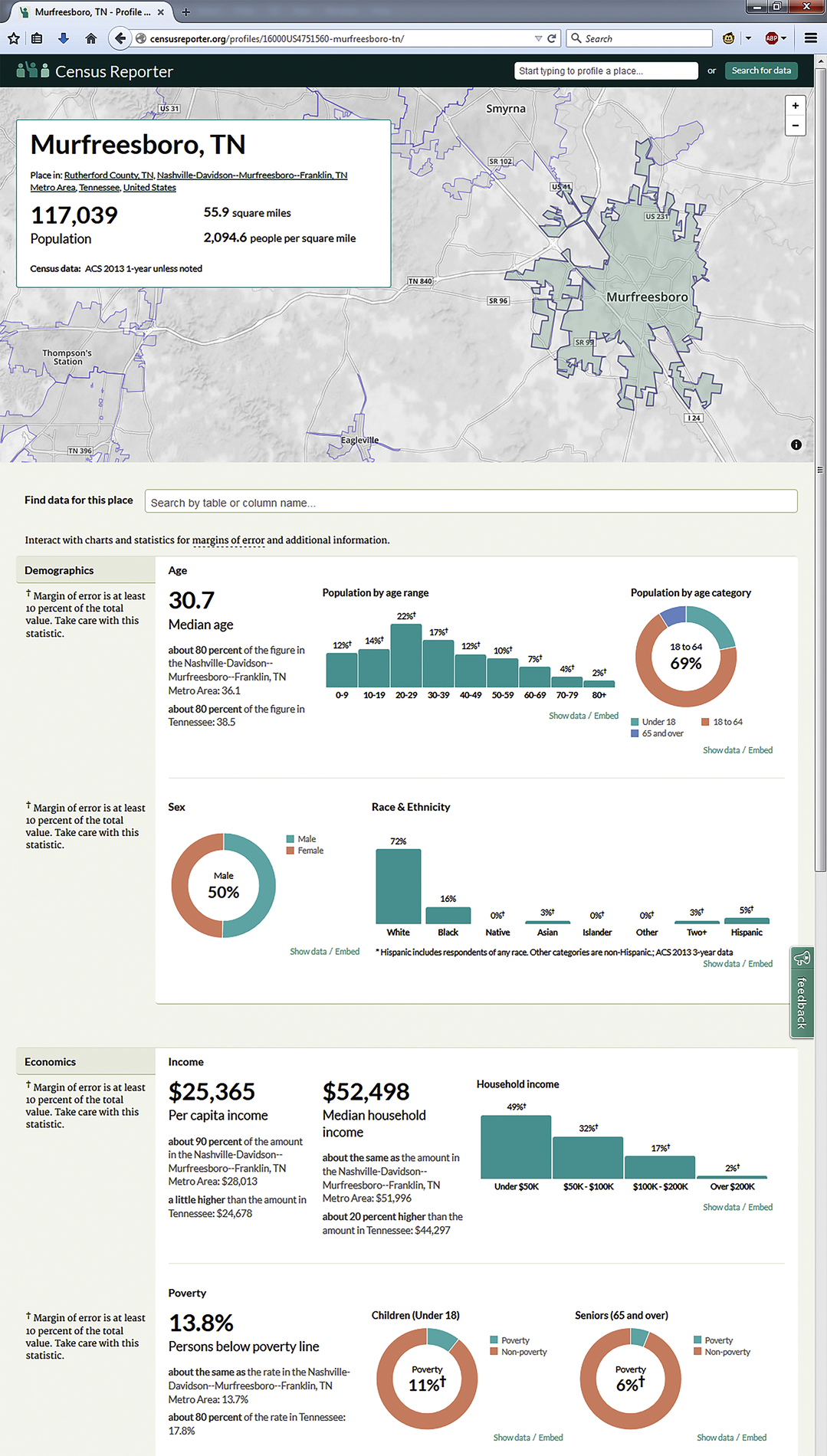

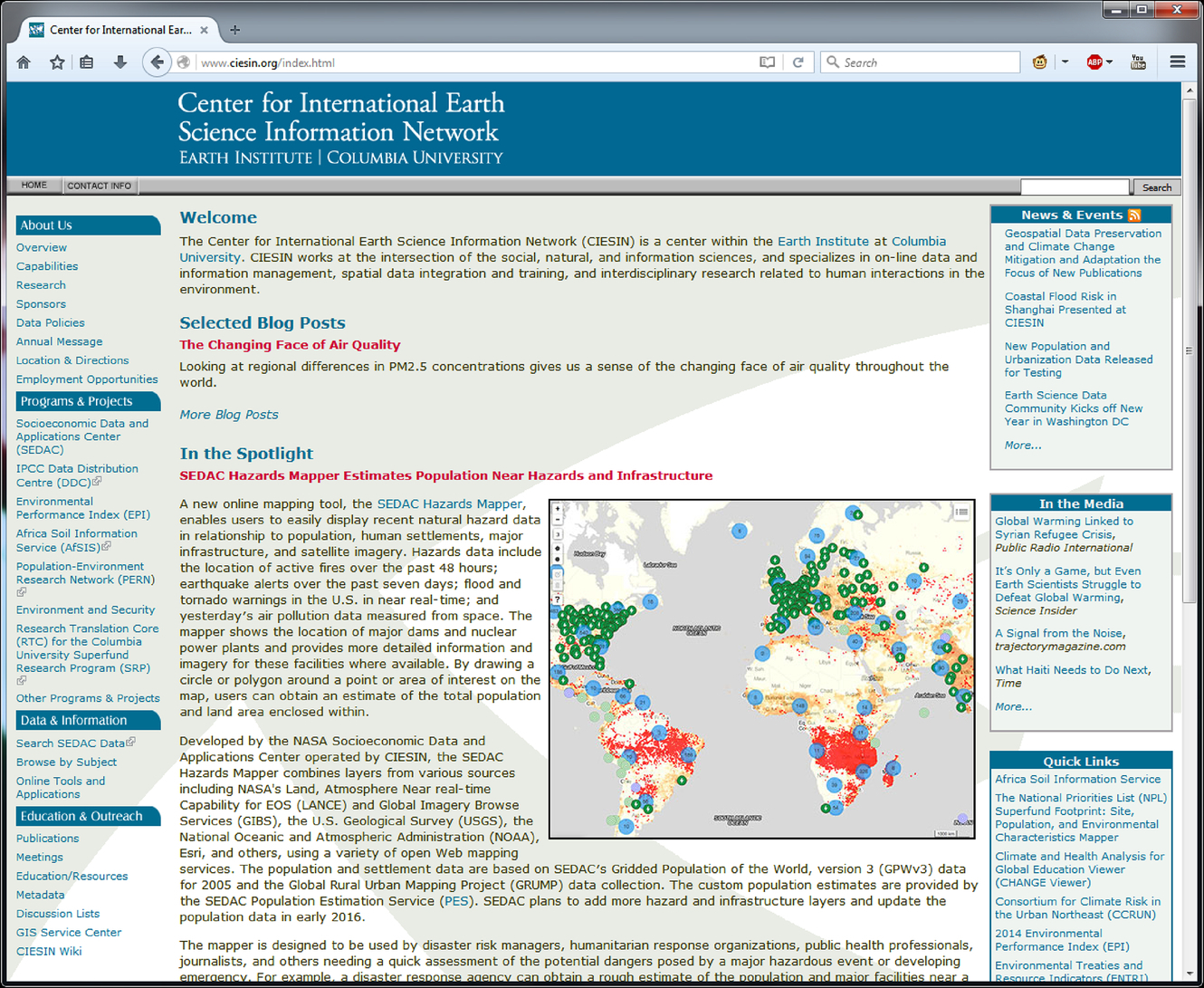

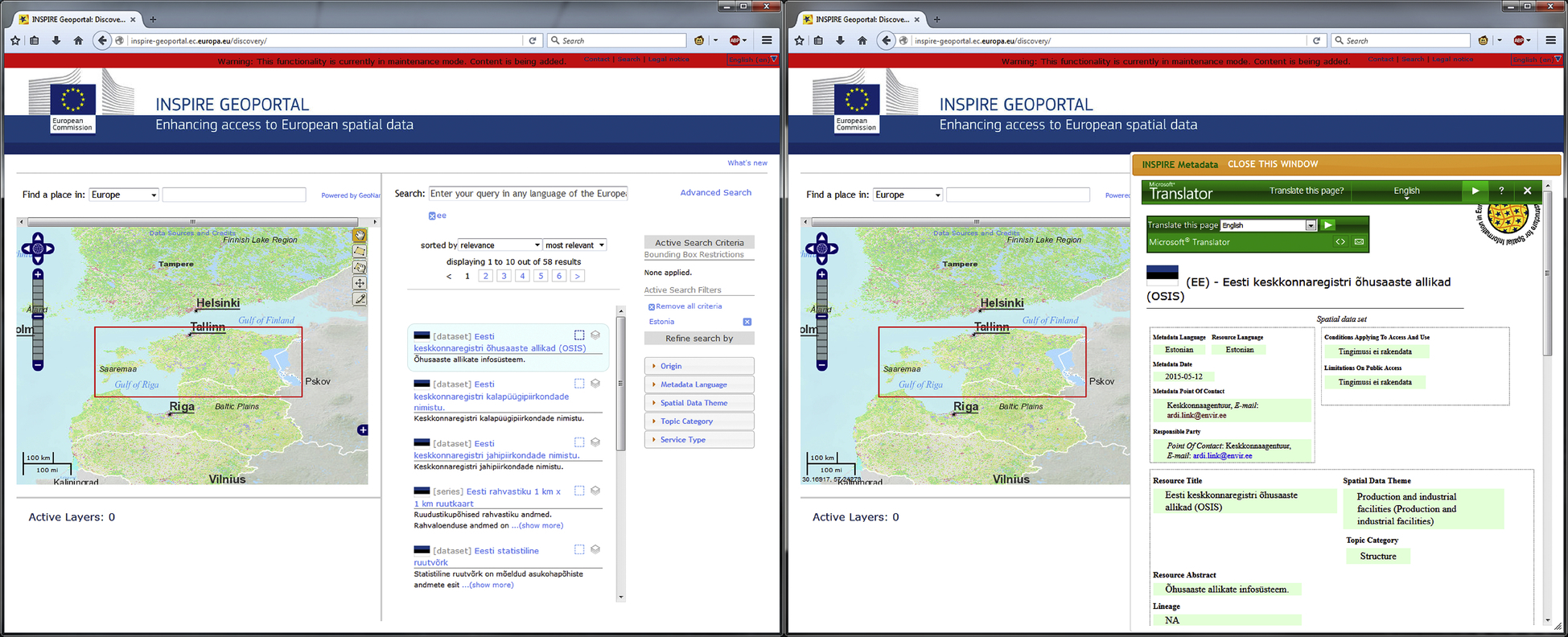

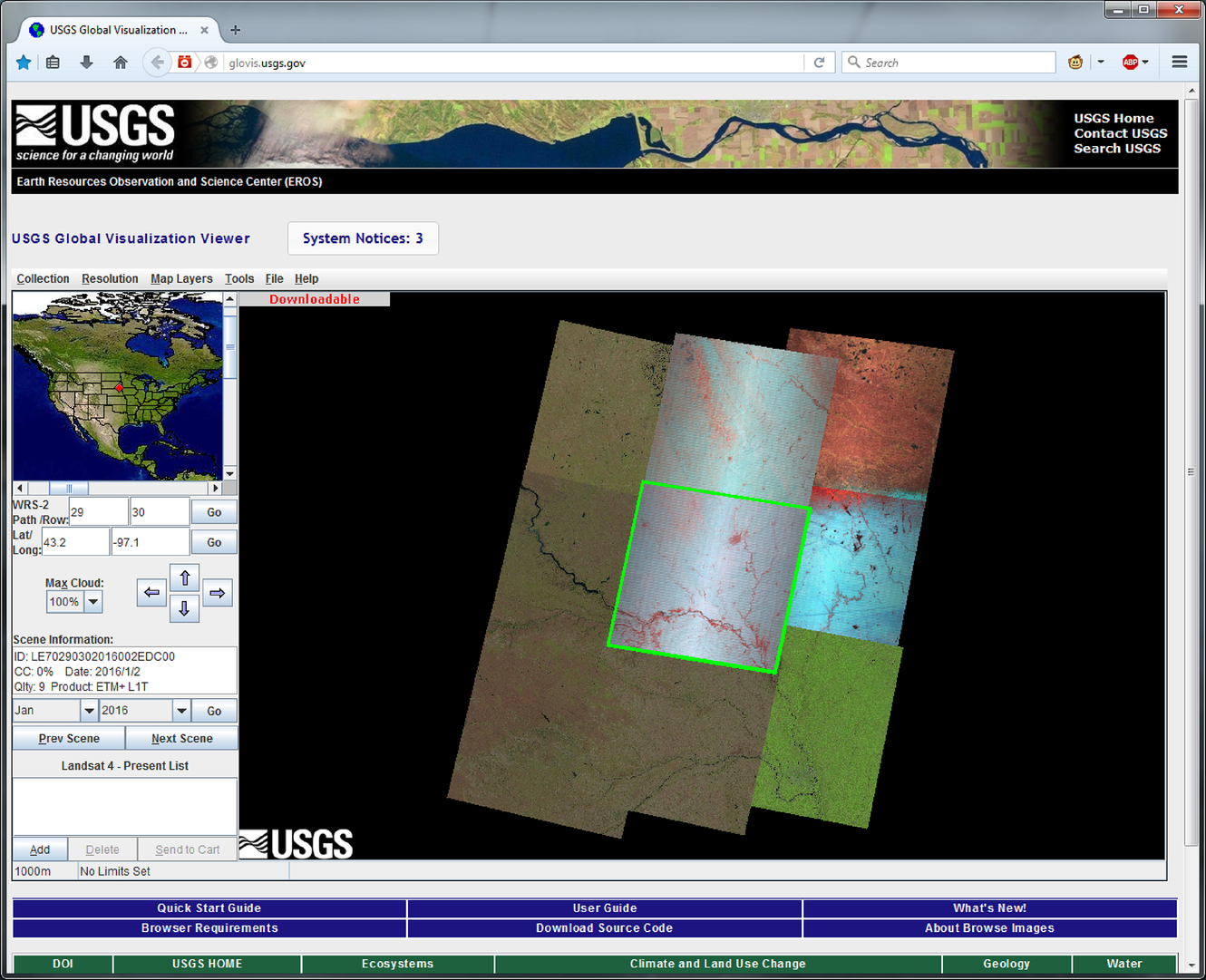

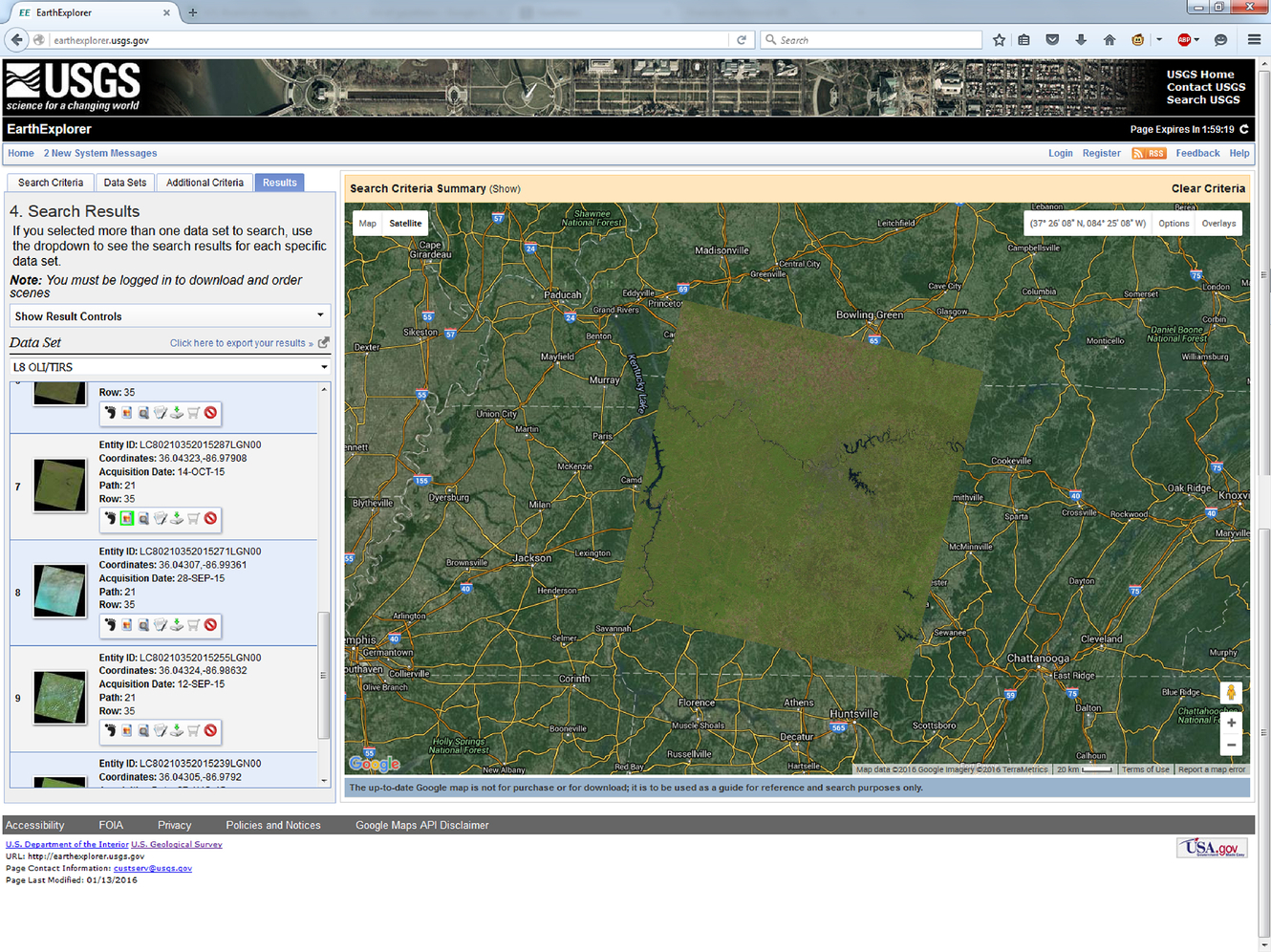

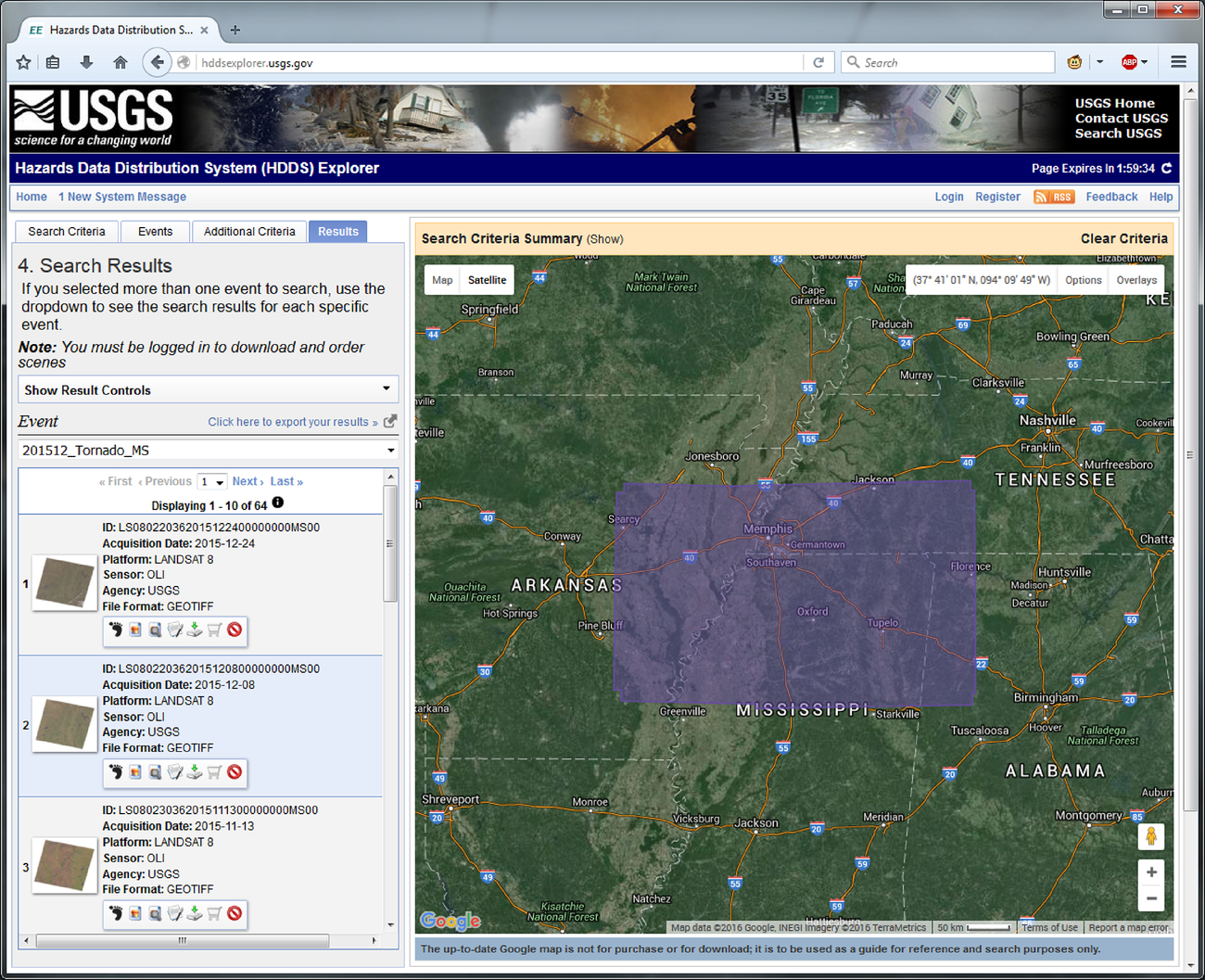

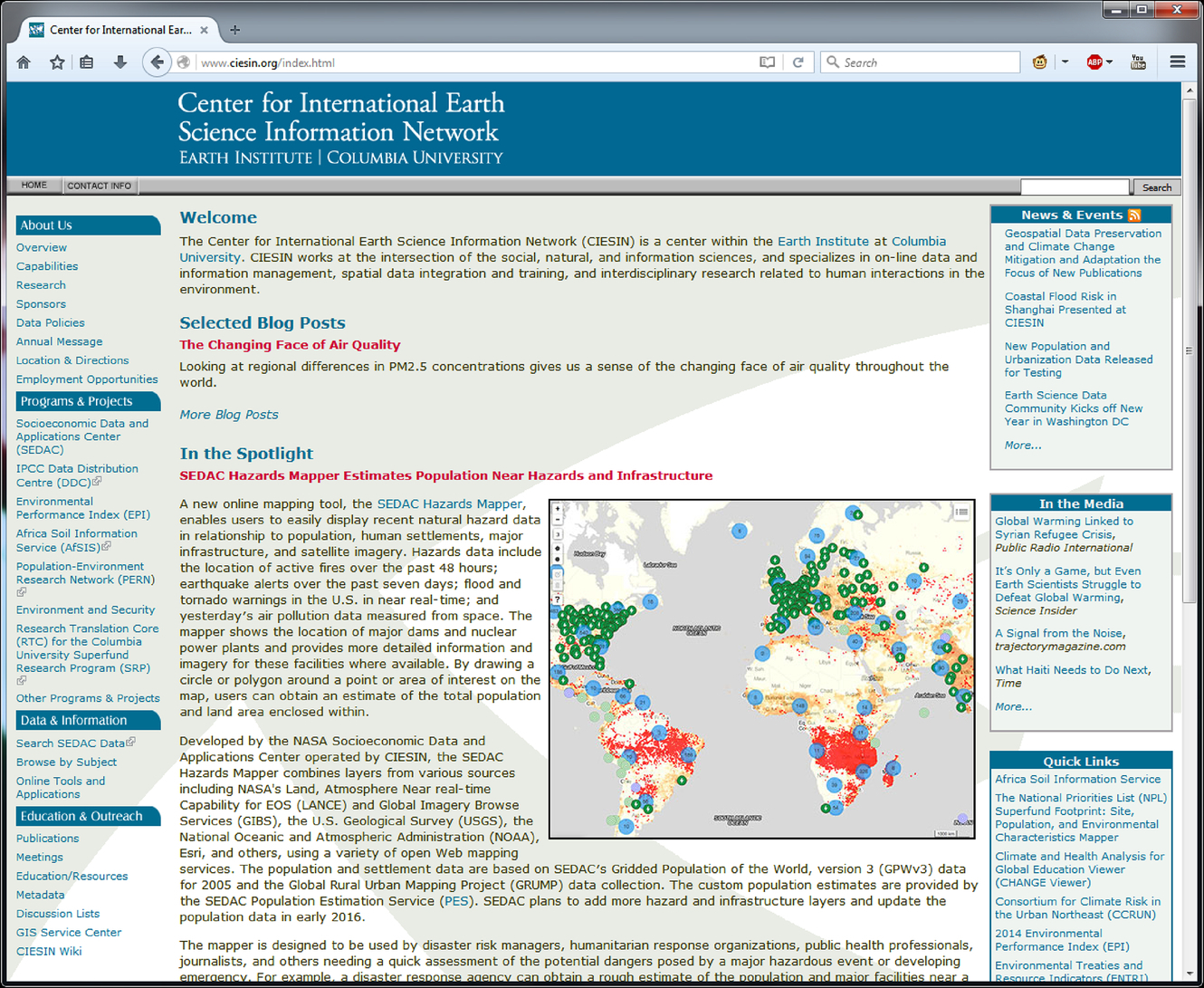

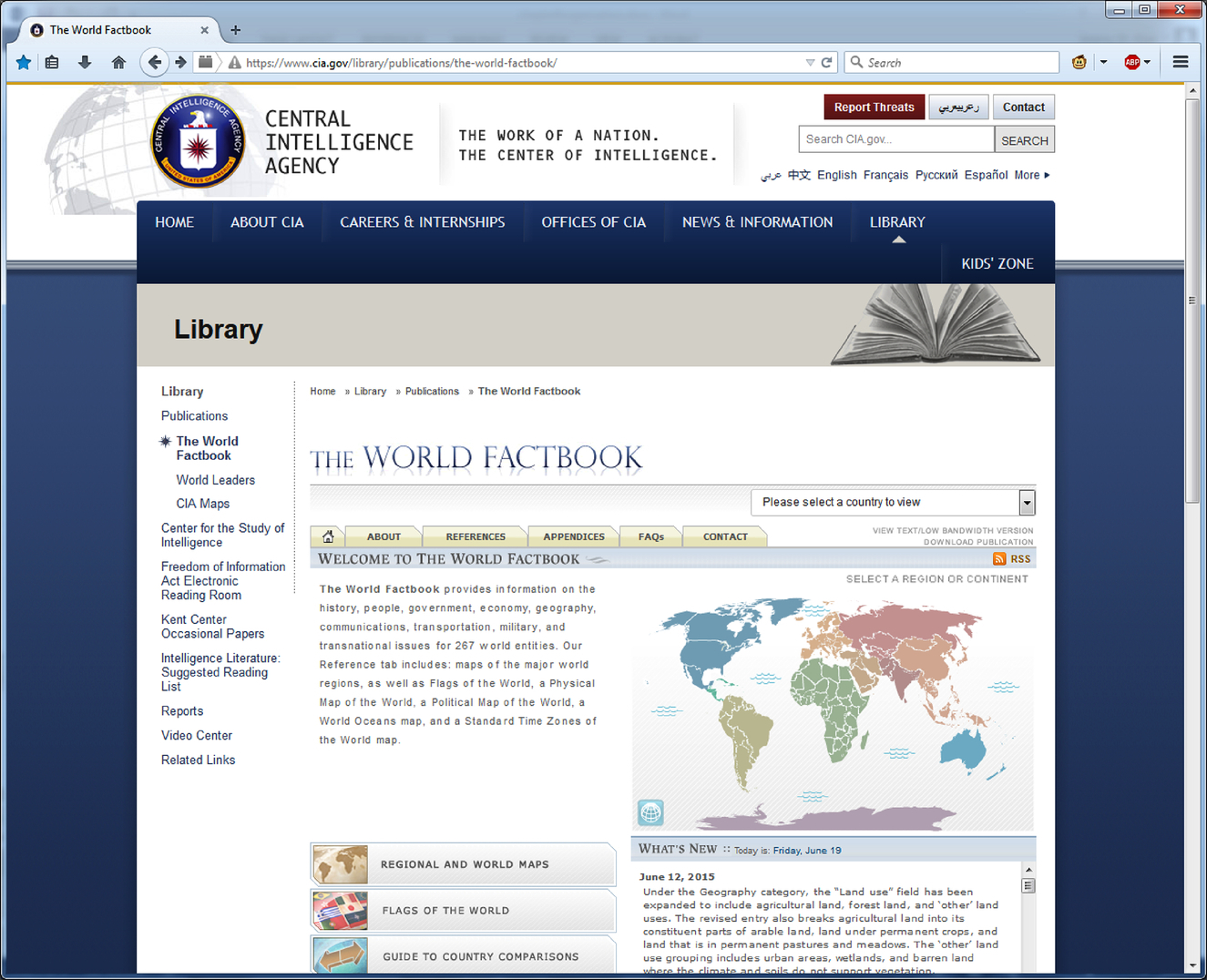

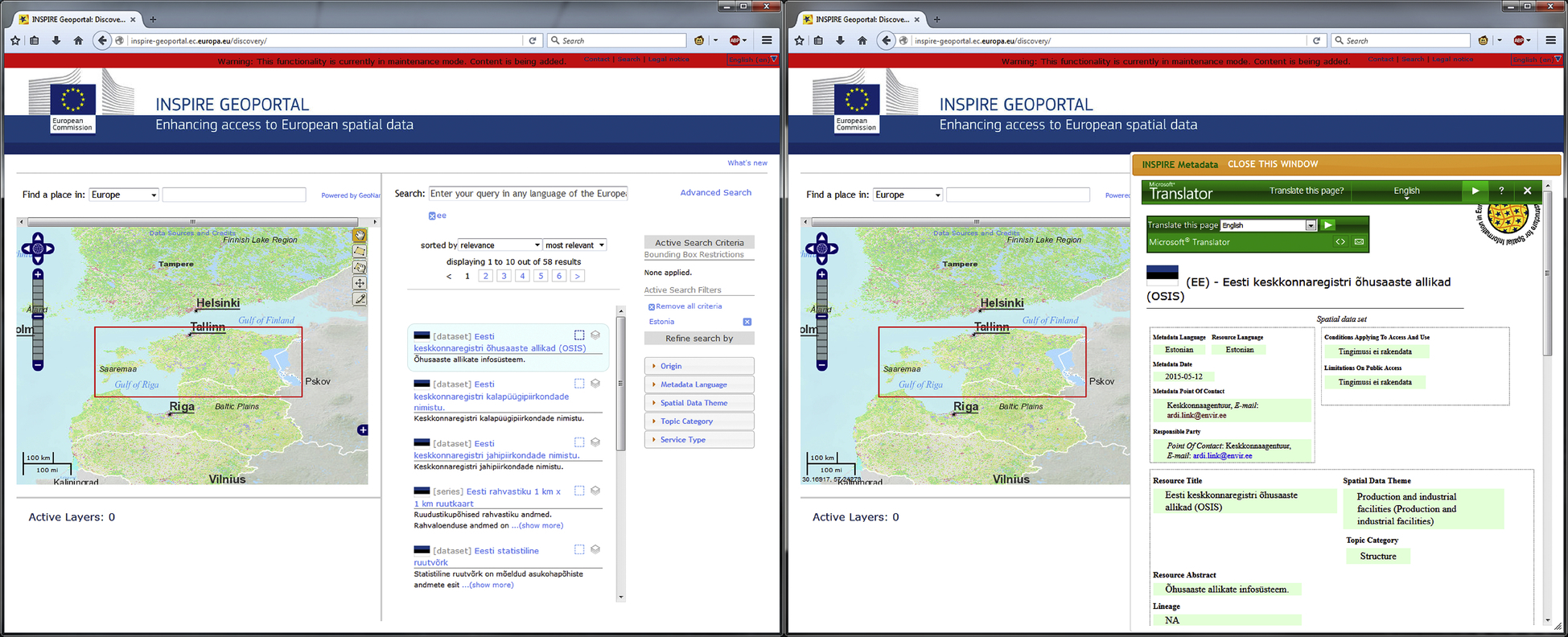

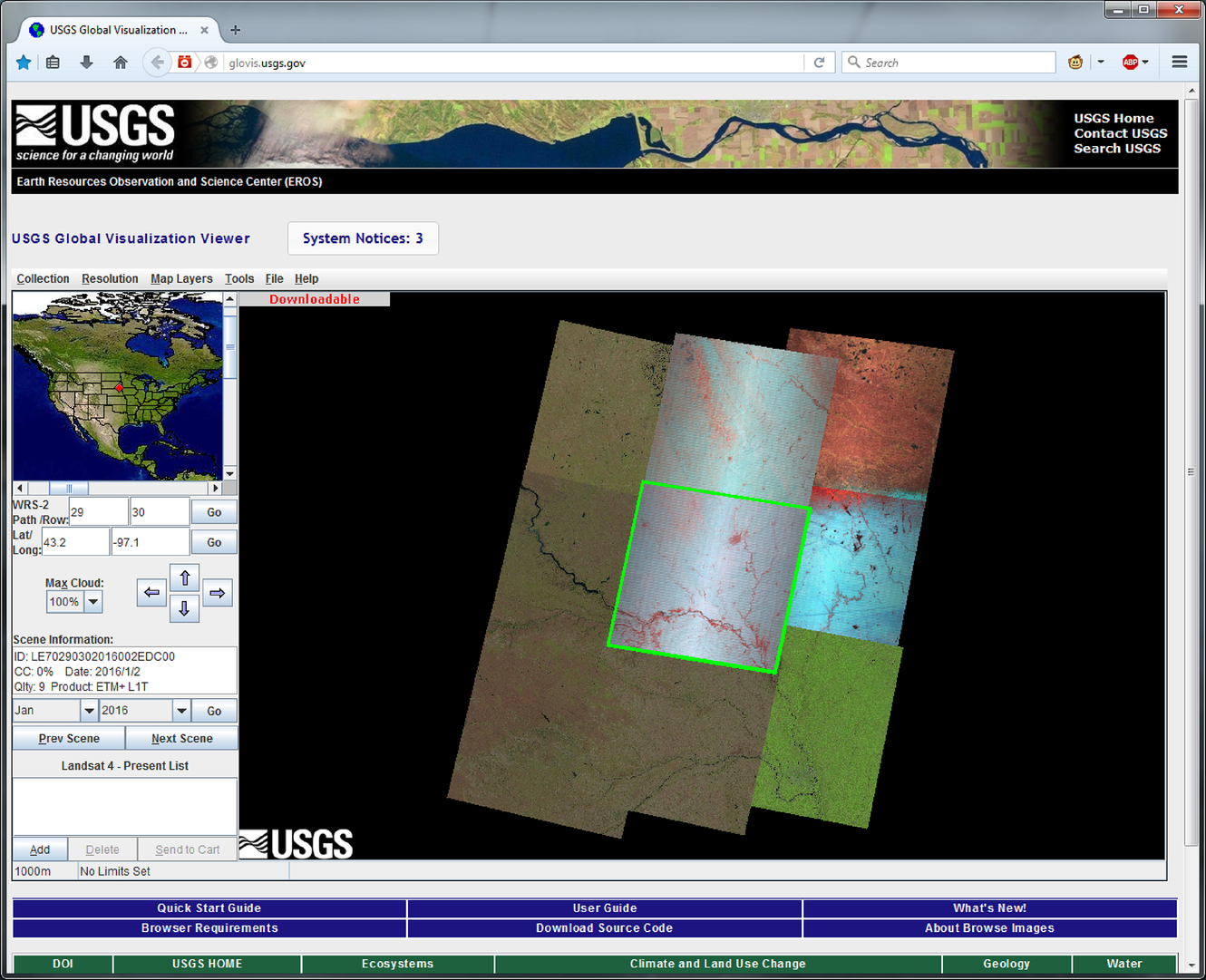

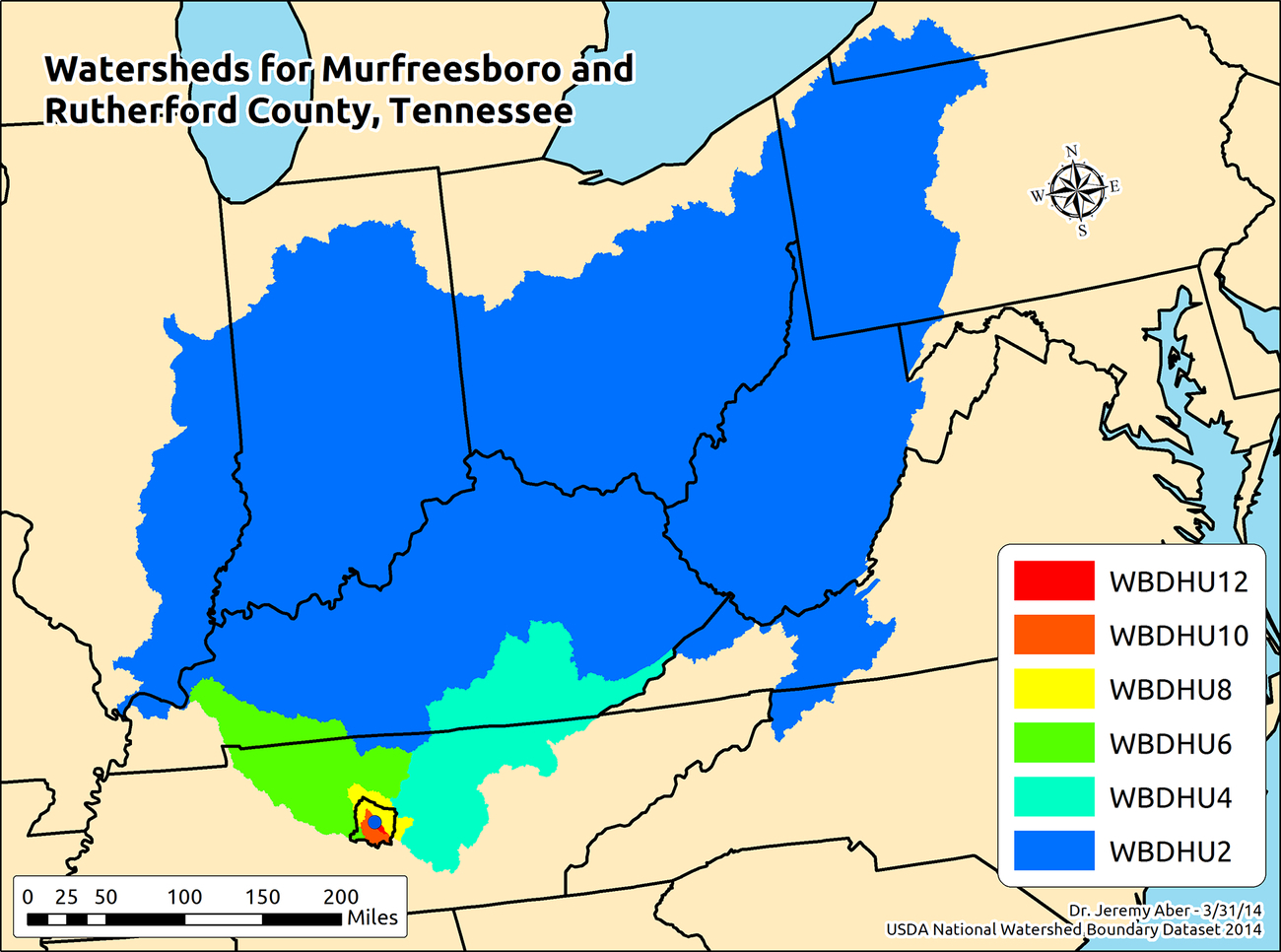

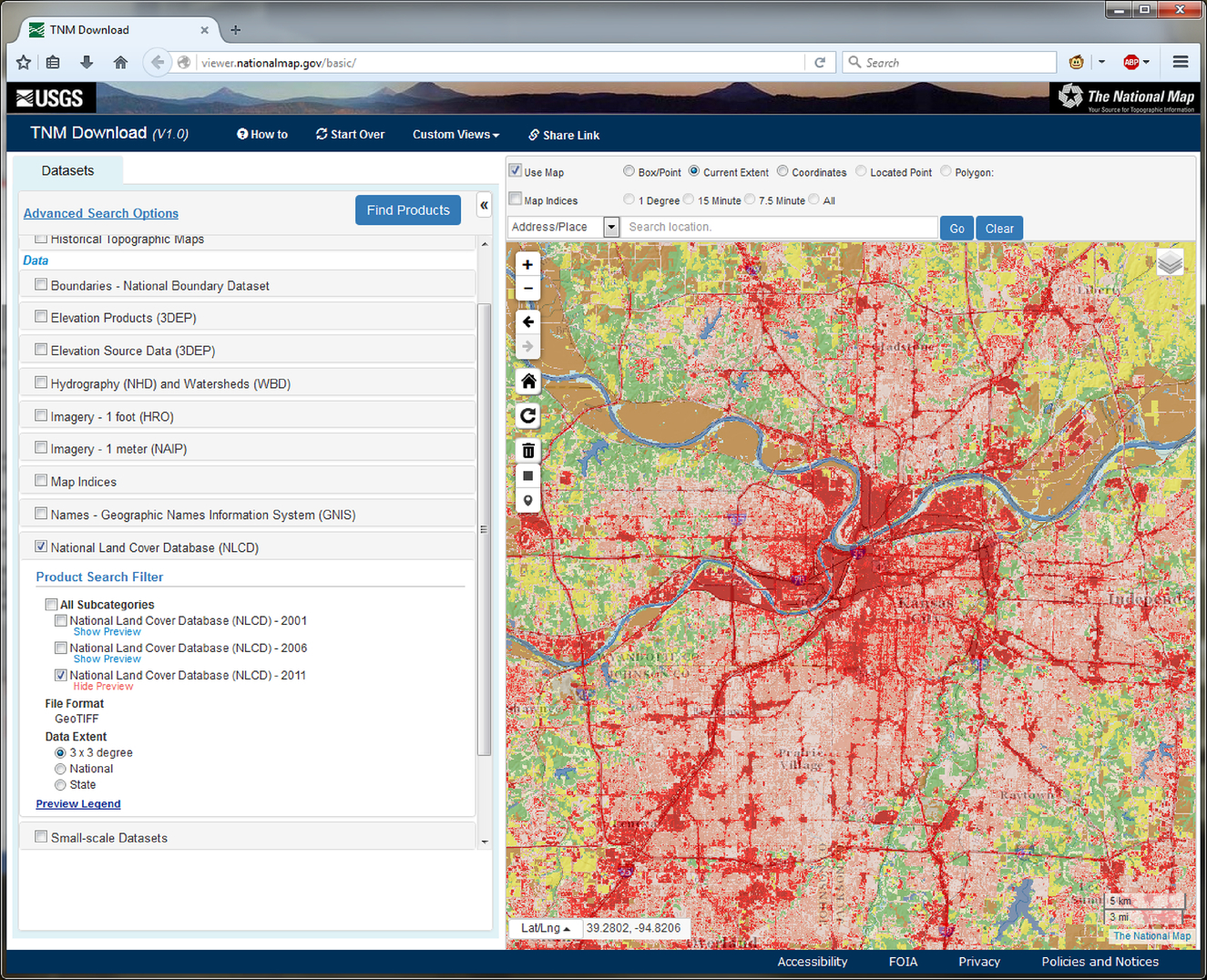

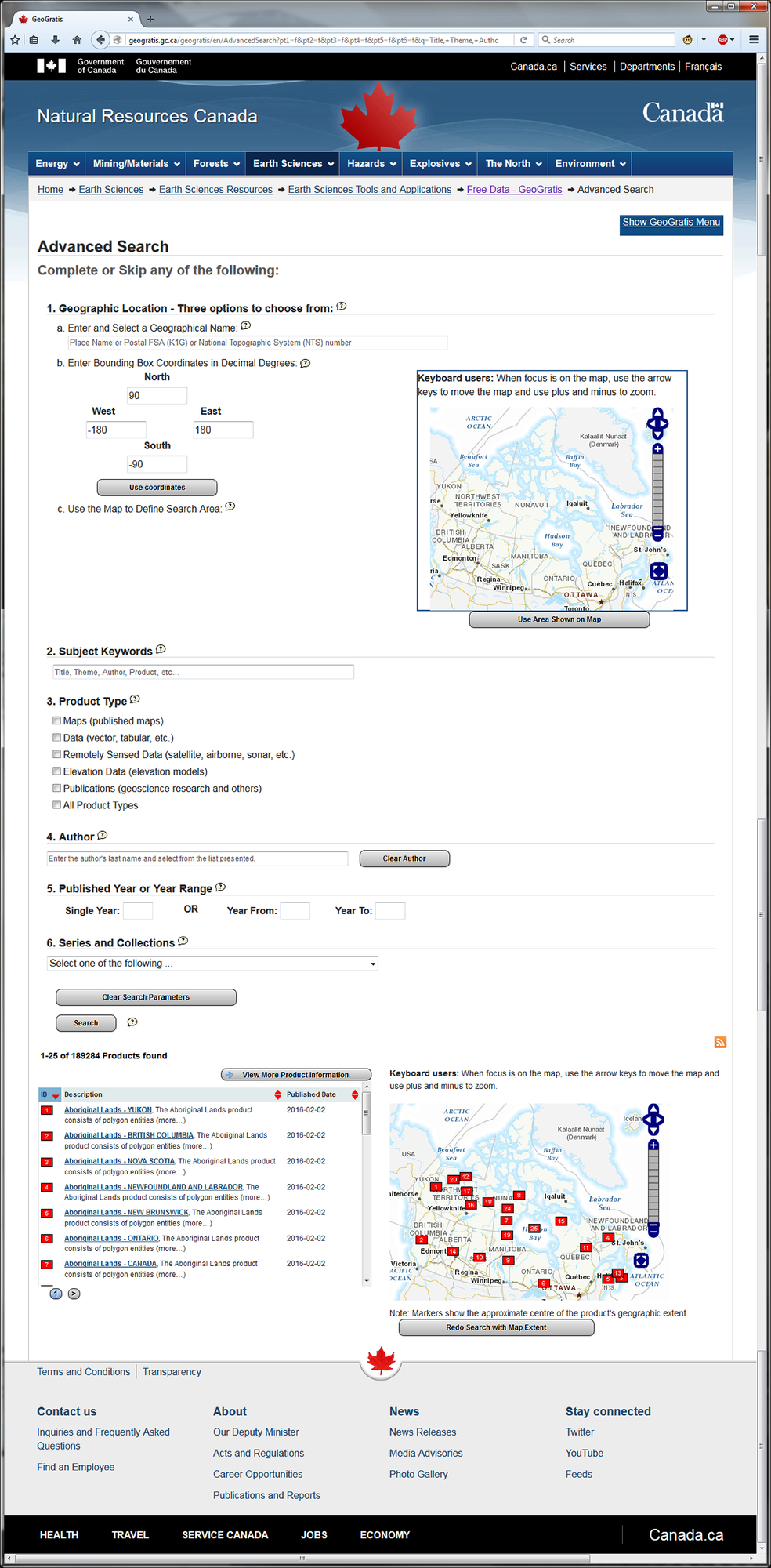

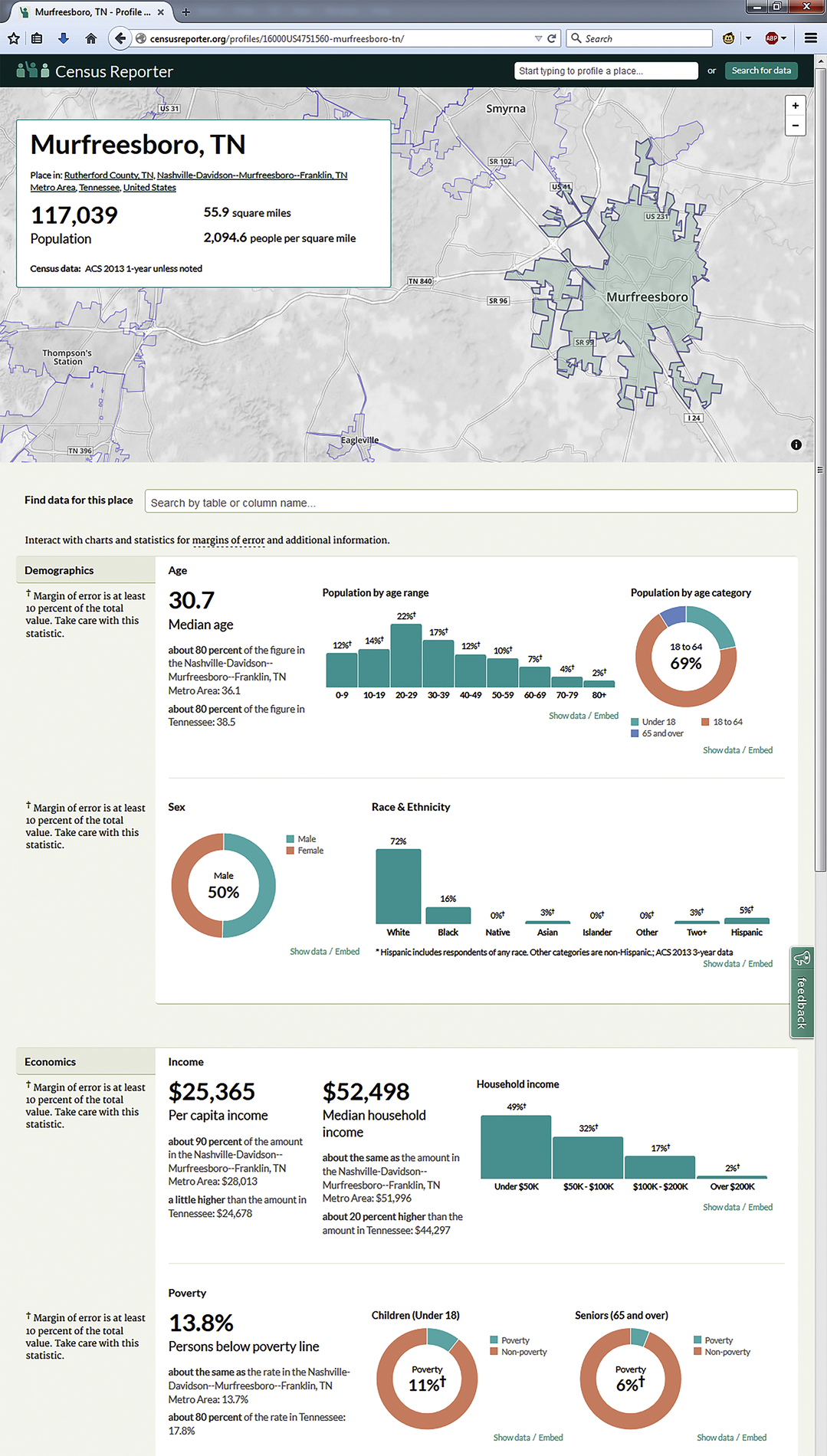

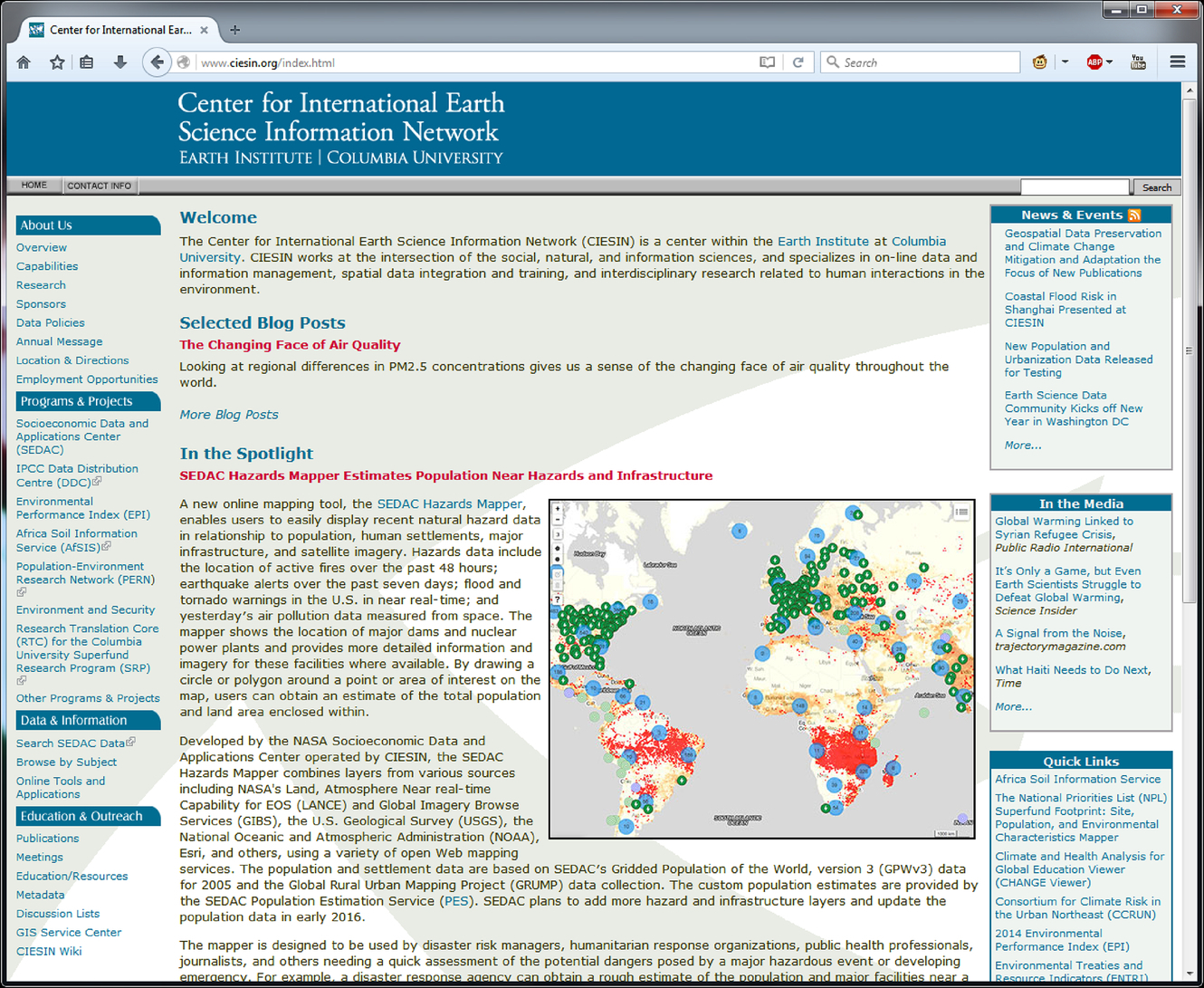

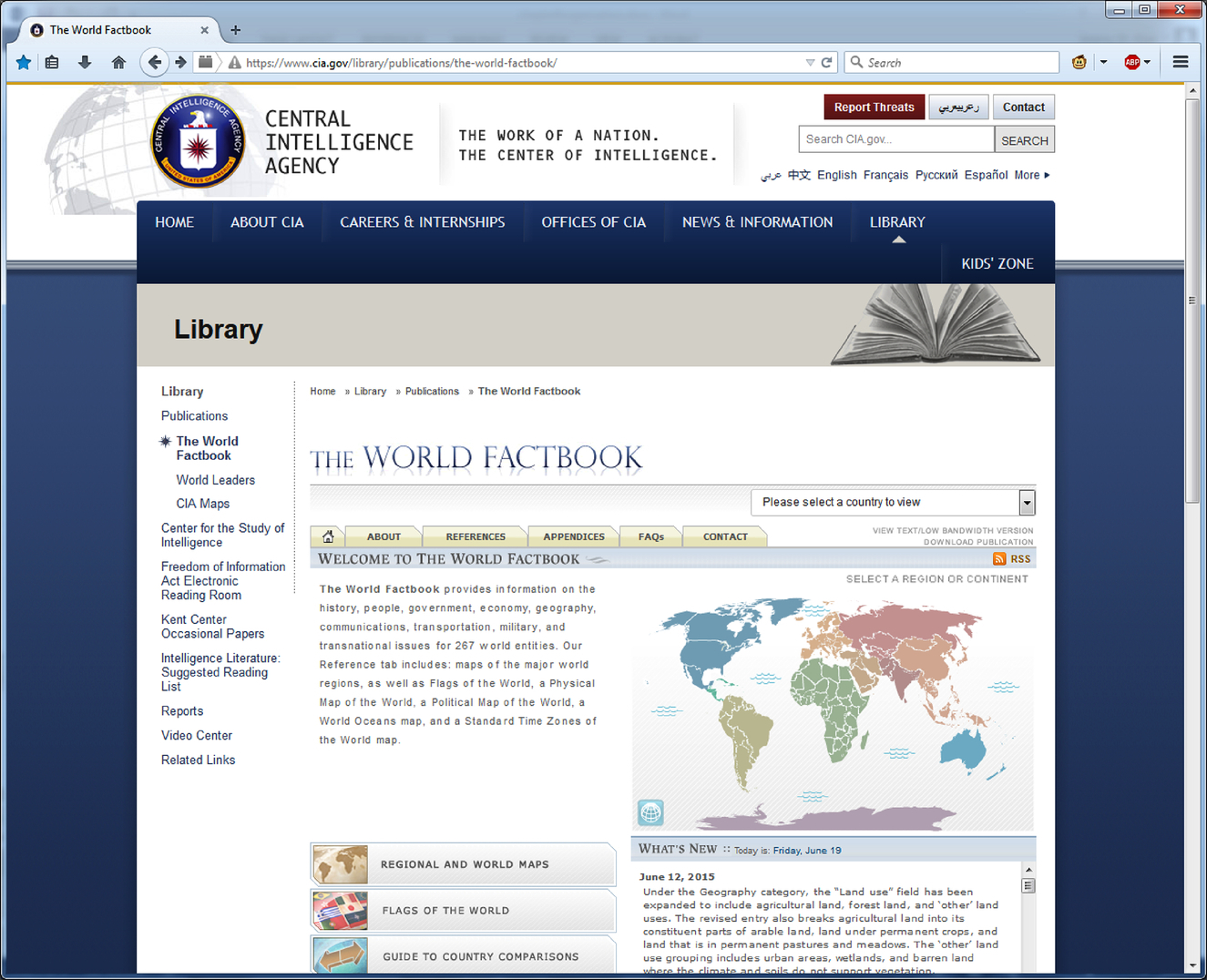

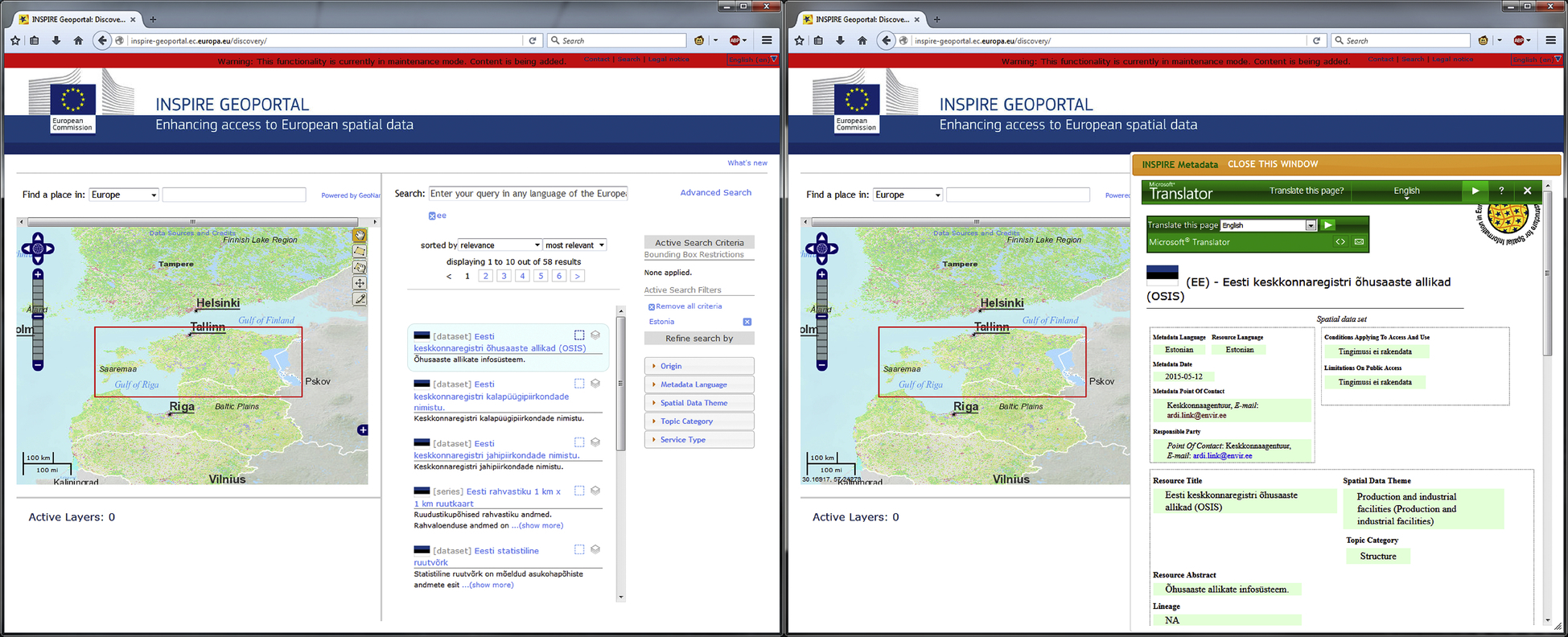

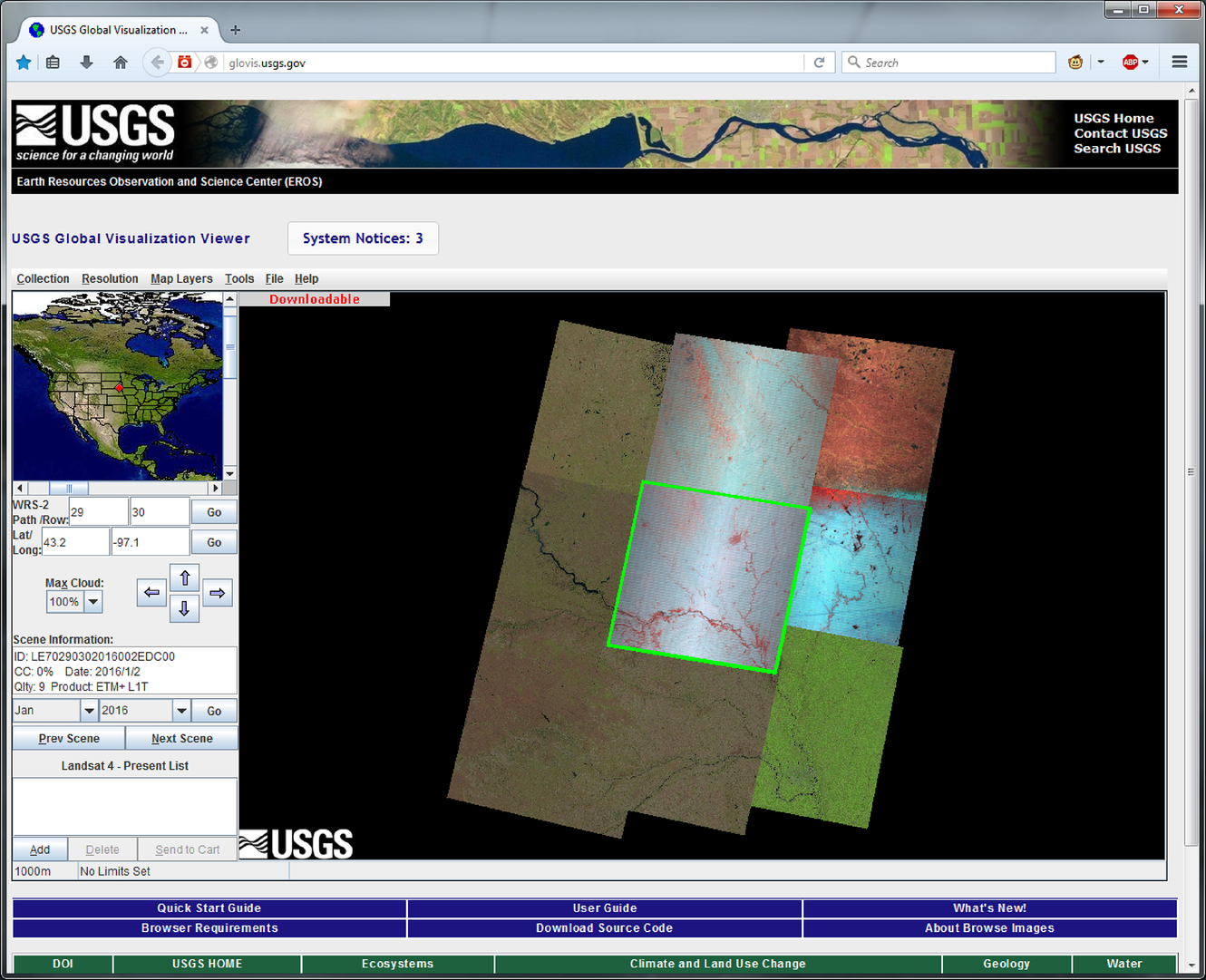

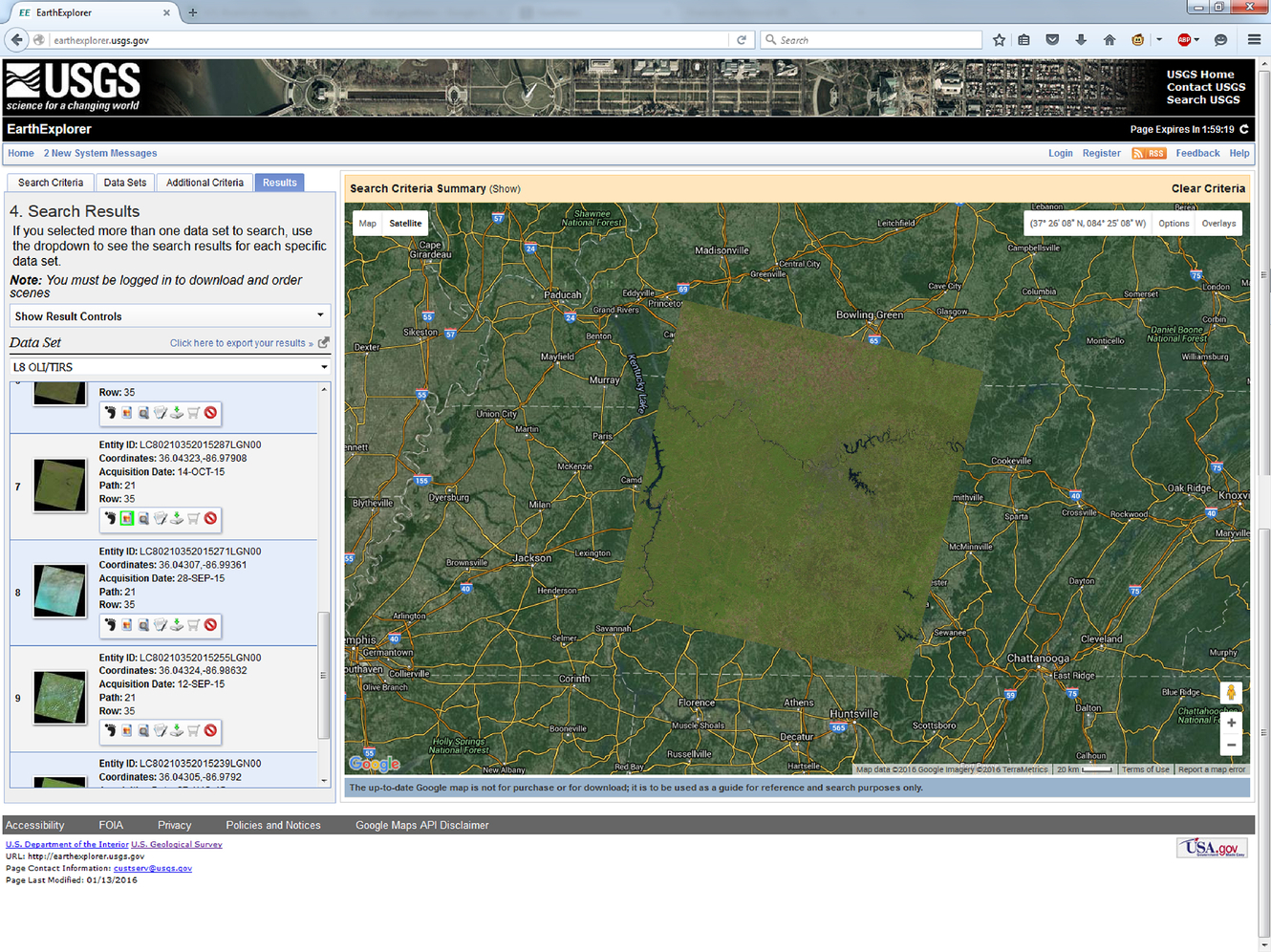

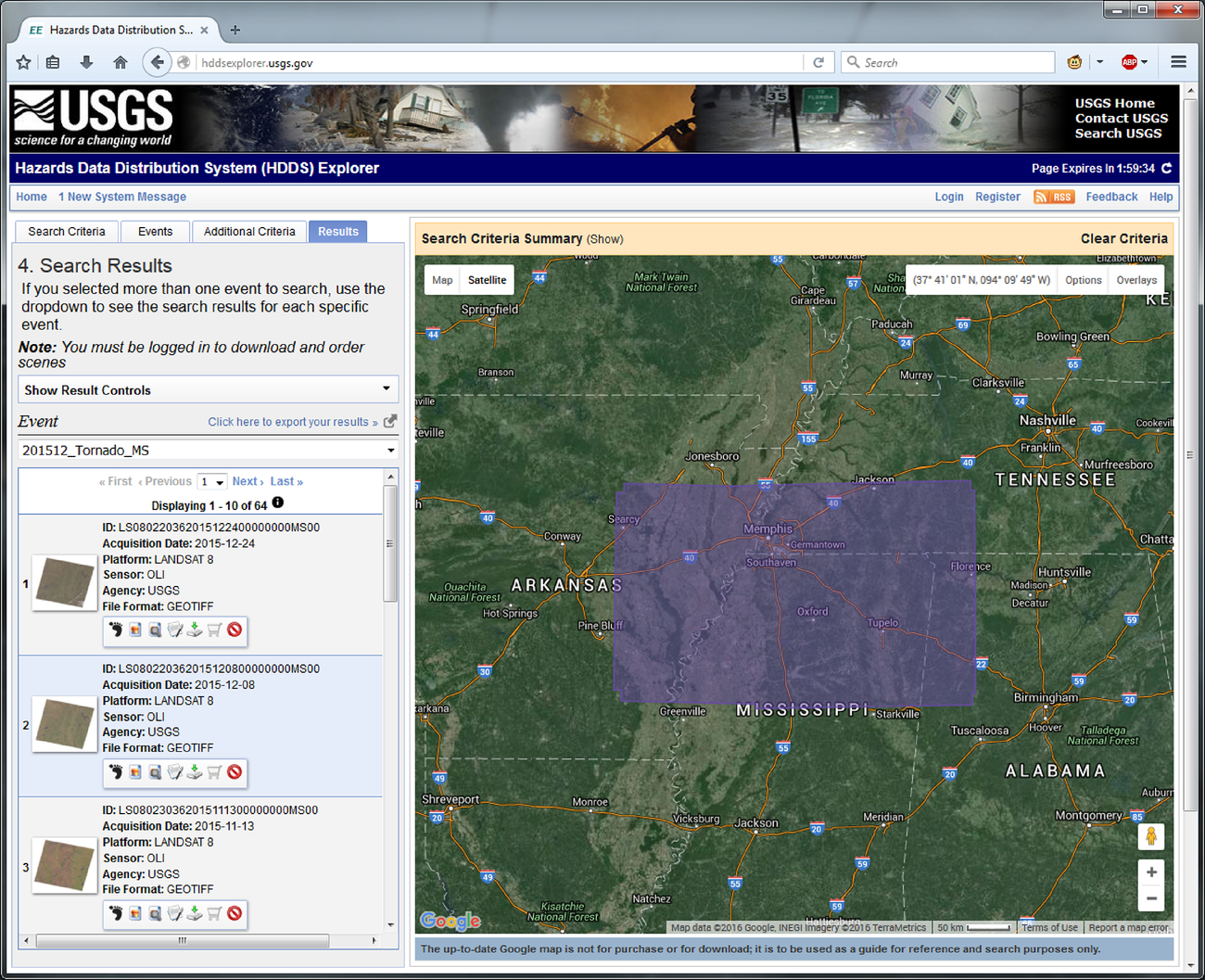

7.3 Navigating the Labyrinth—Where to Go to Get What?

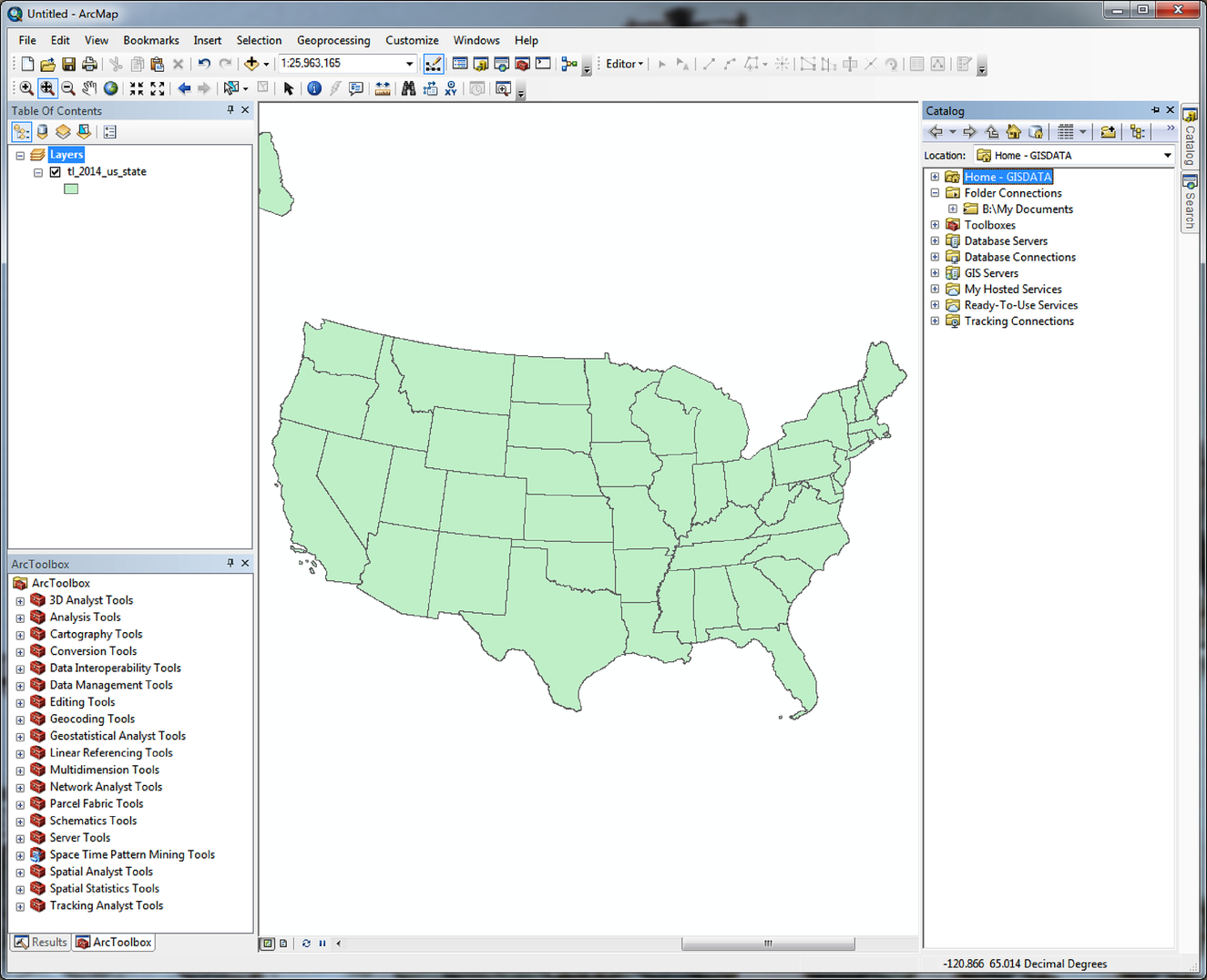

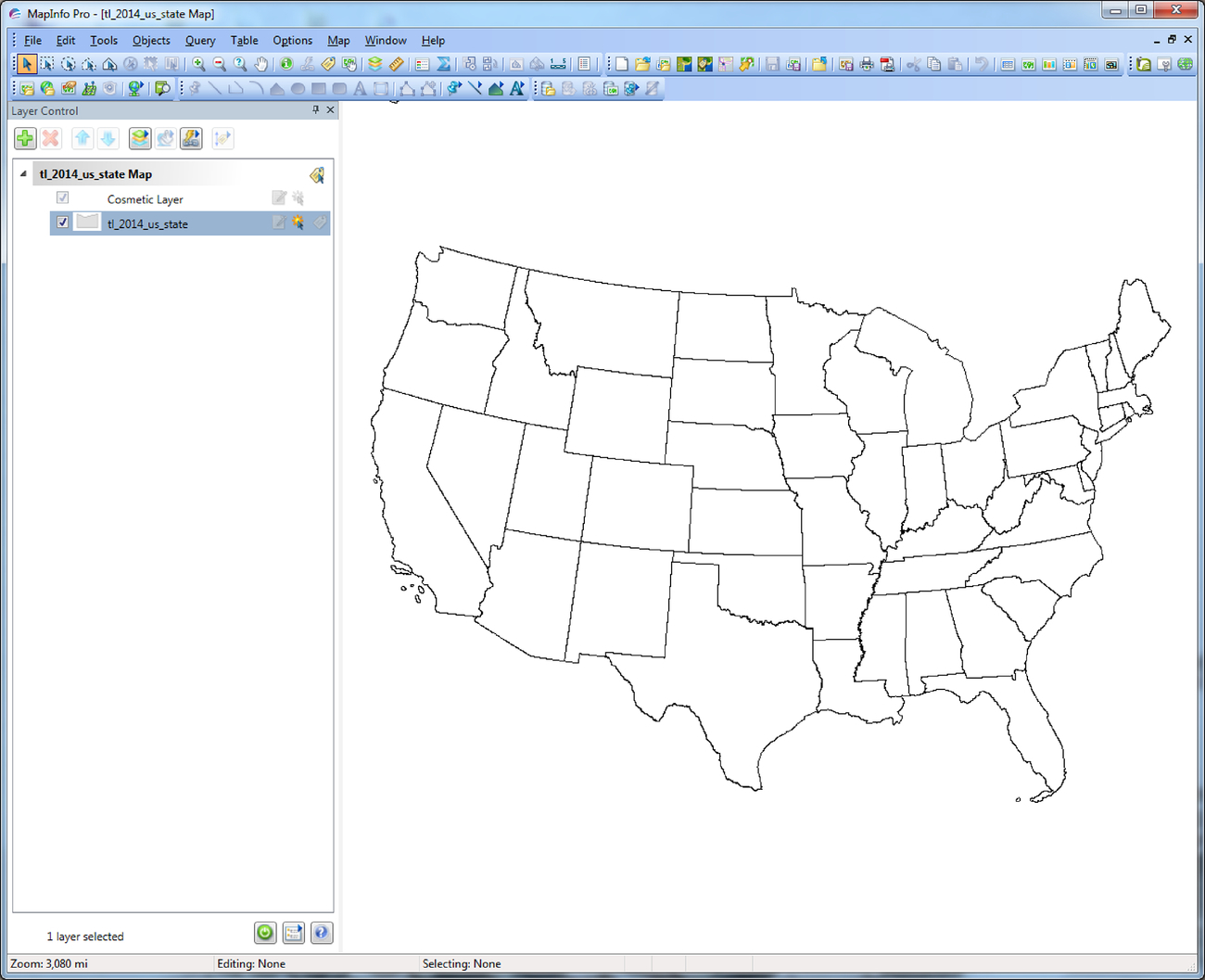

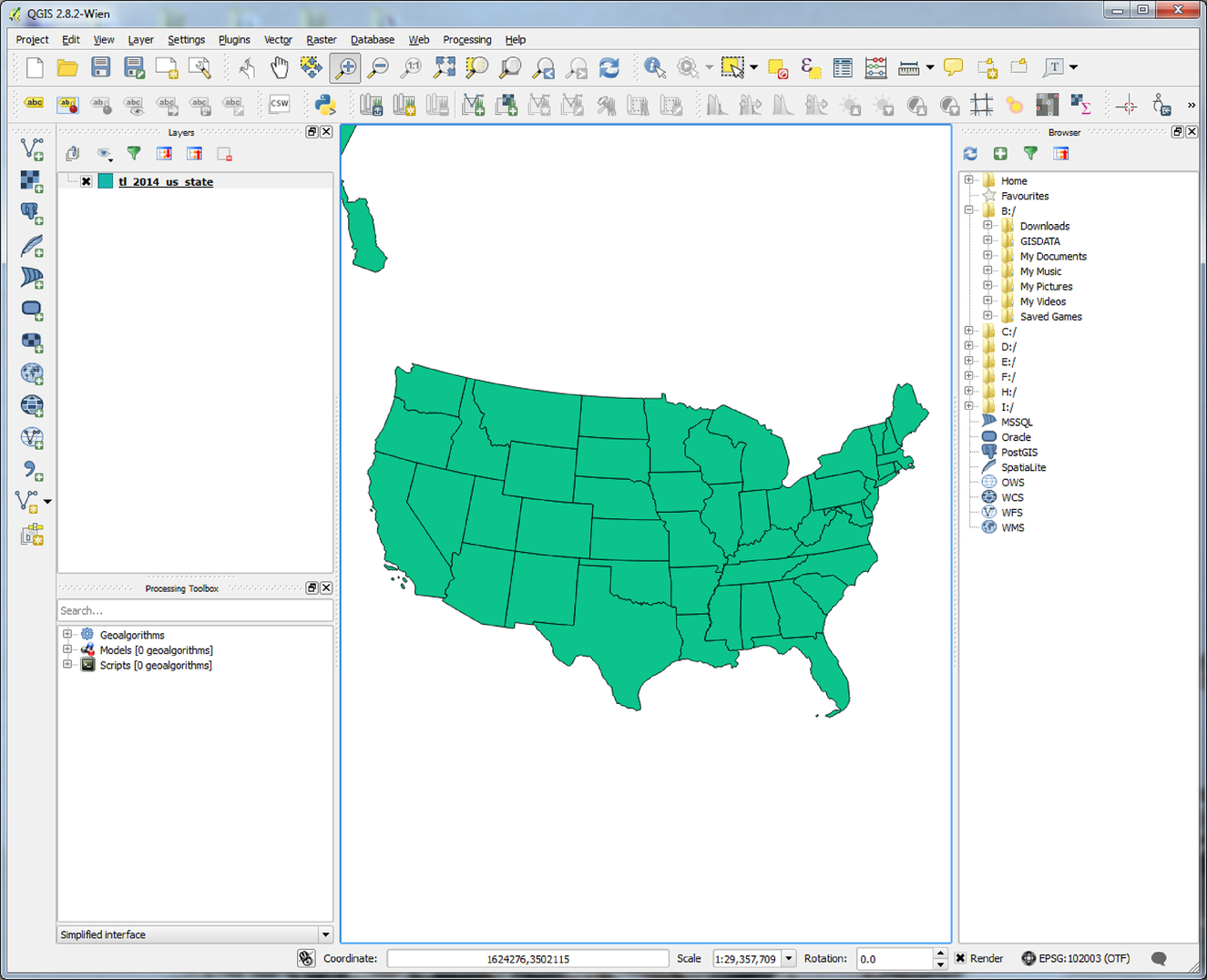

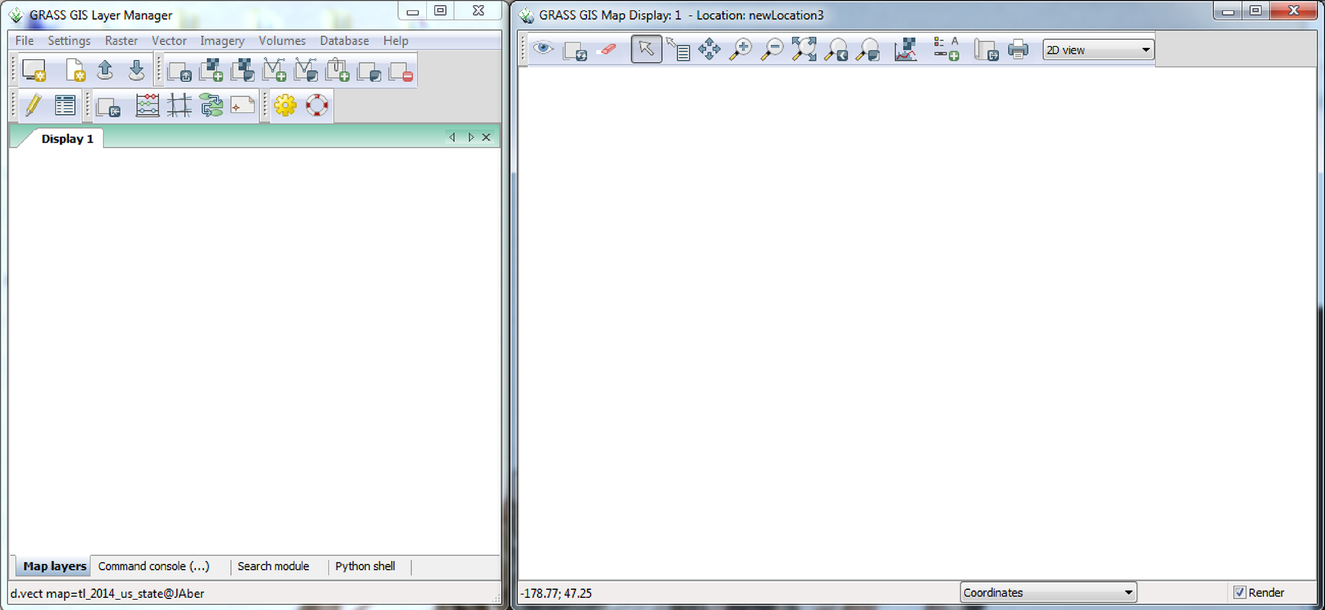

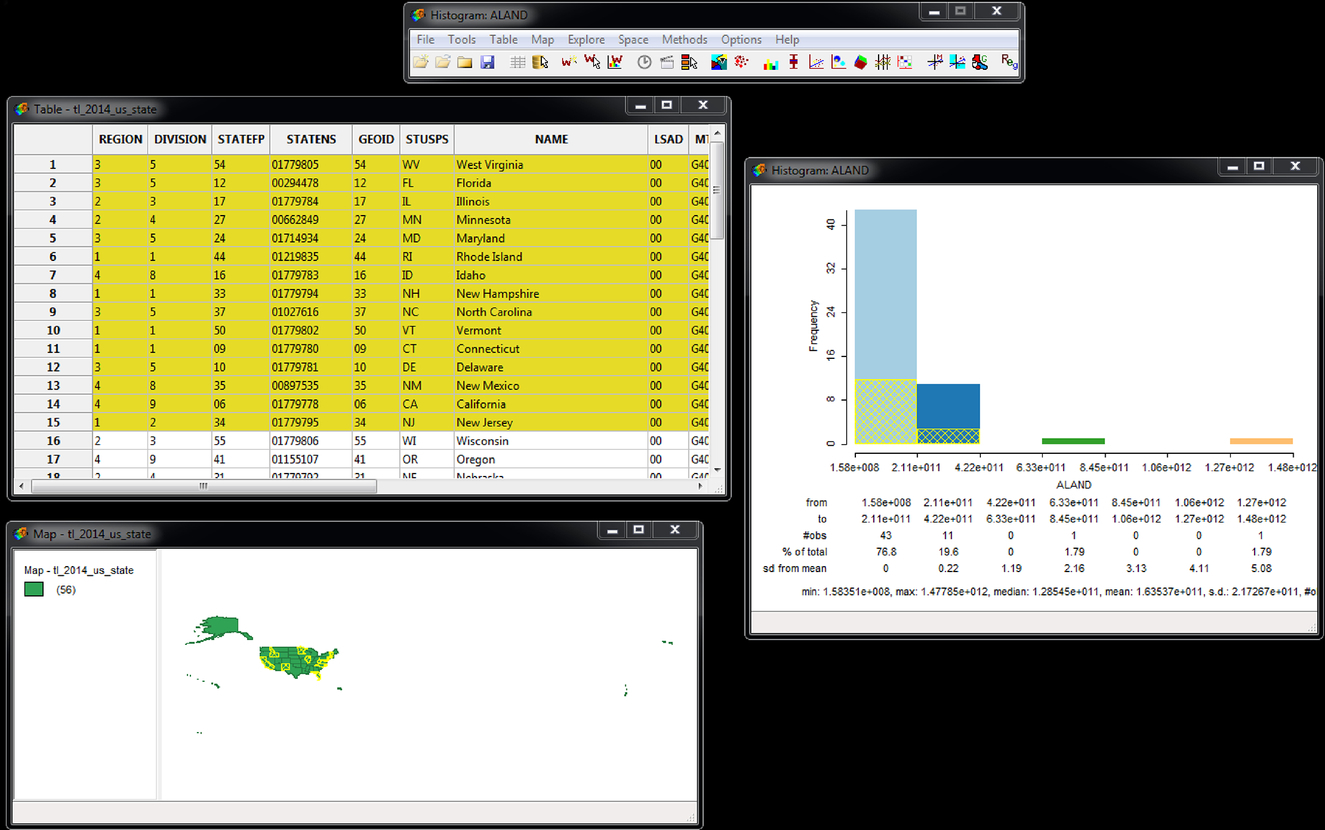

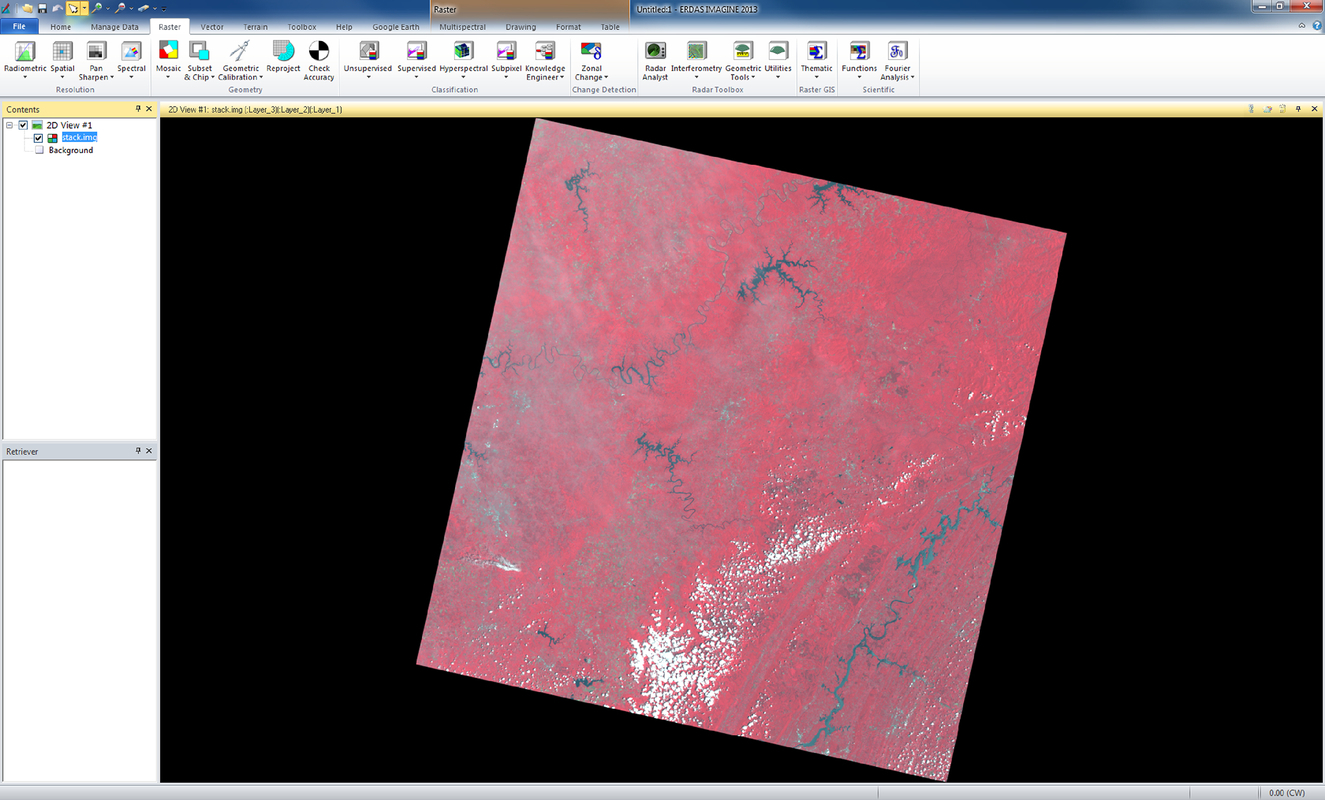

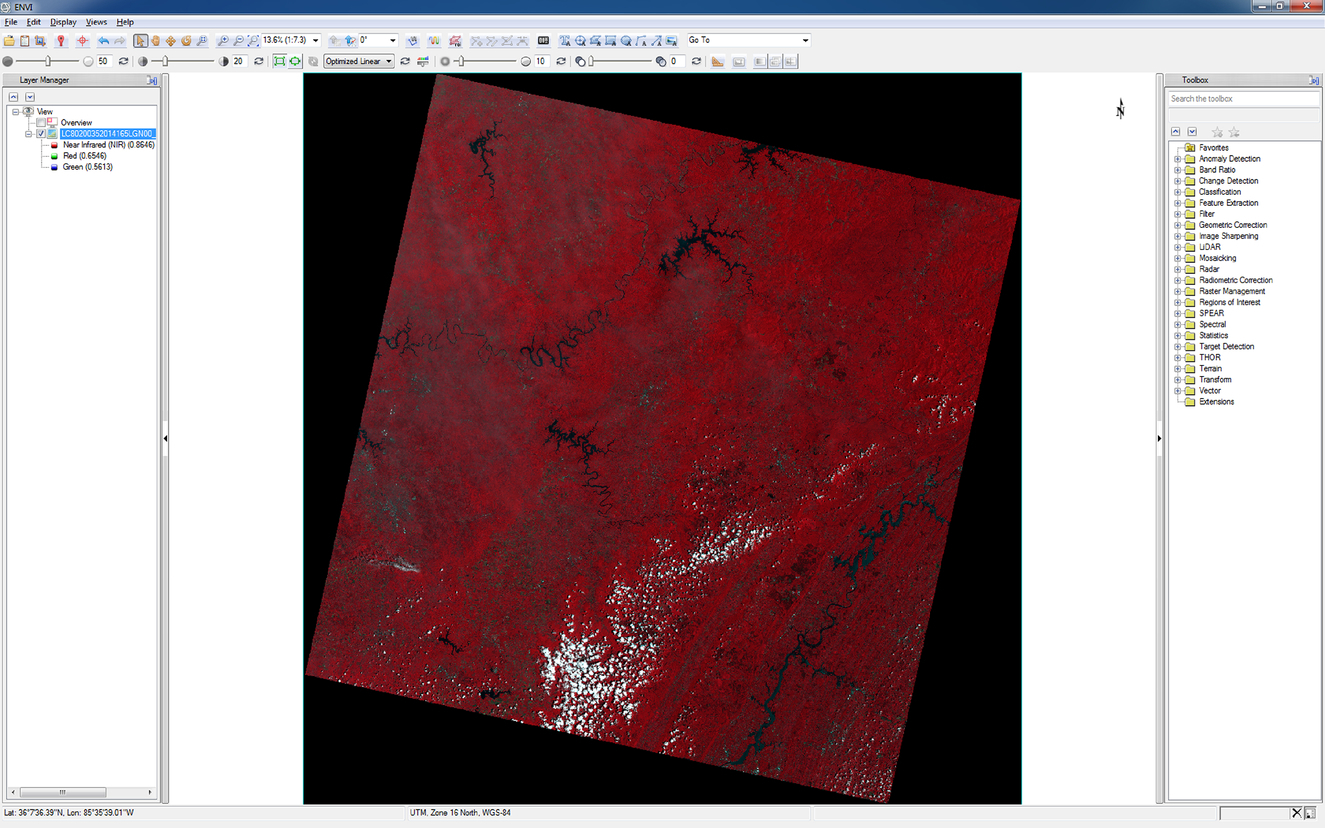

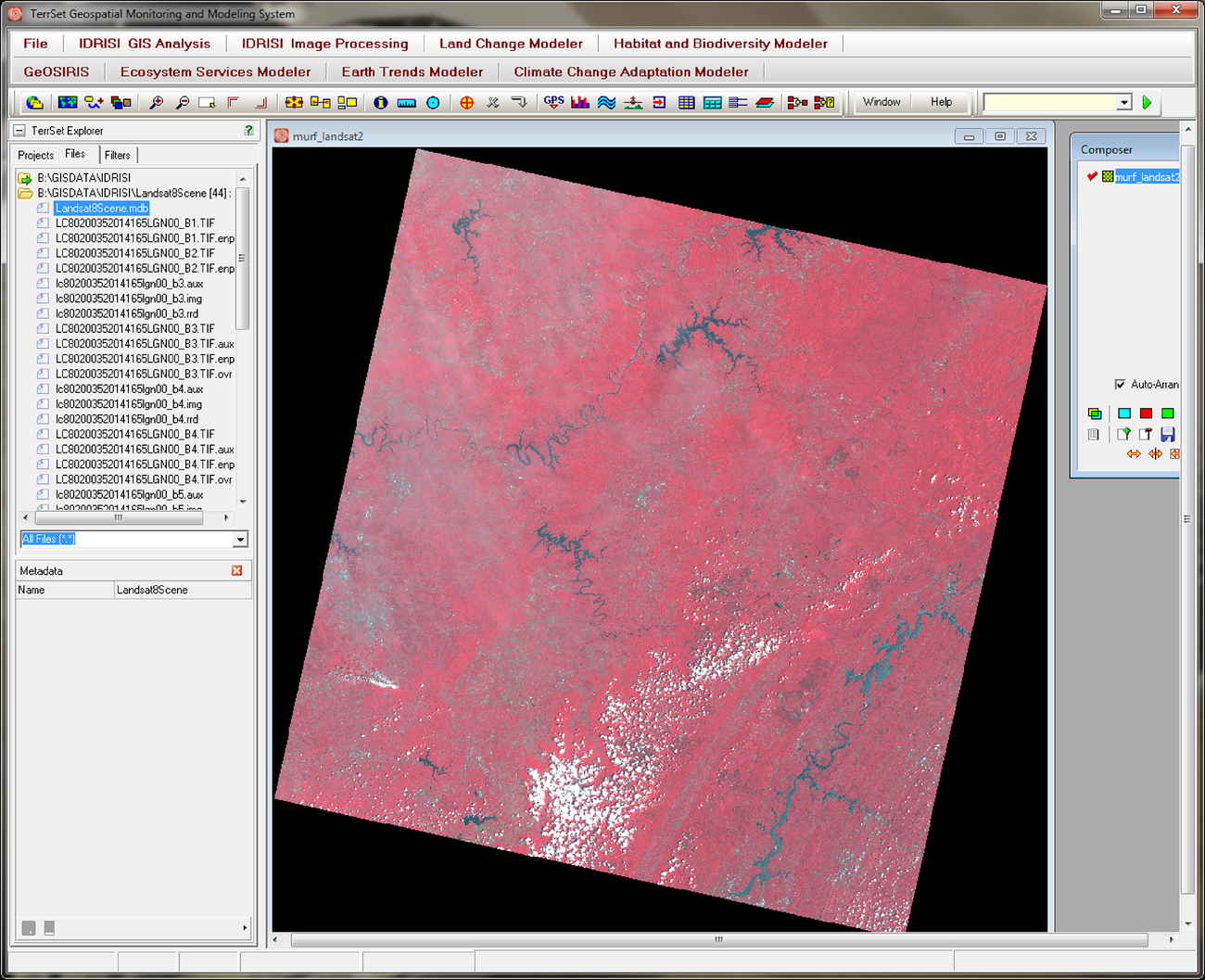

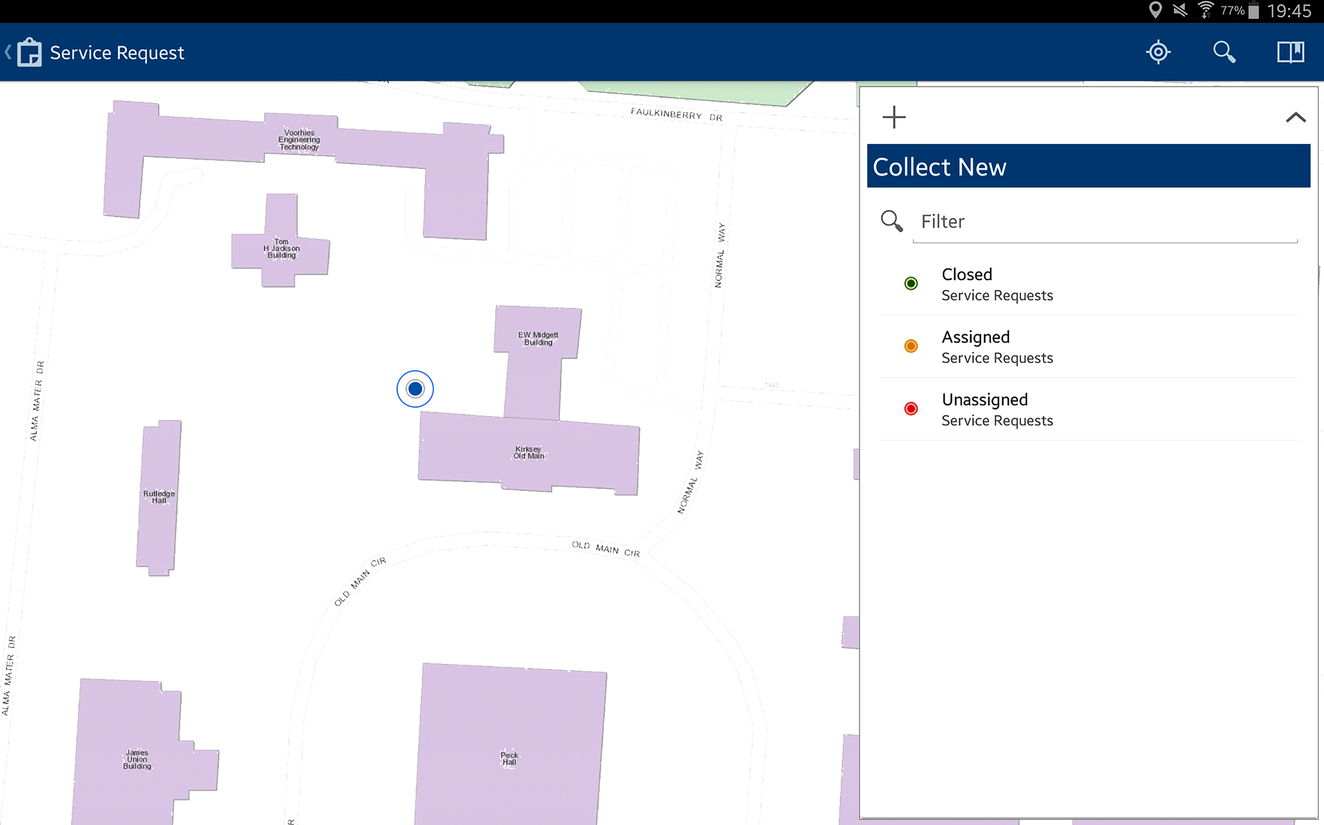

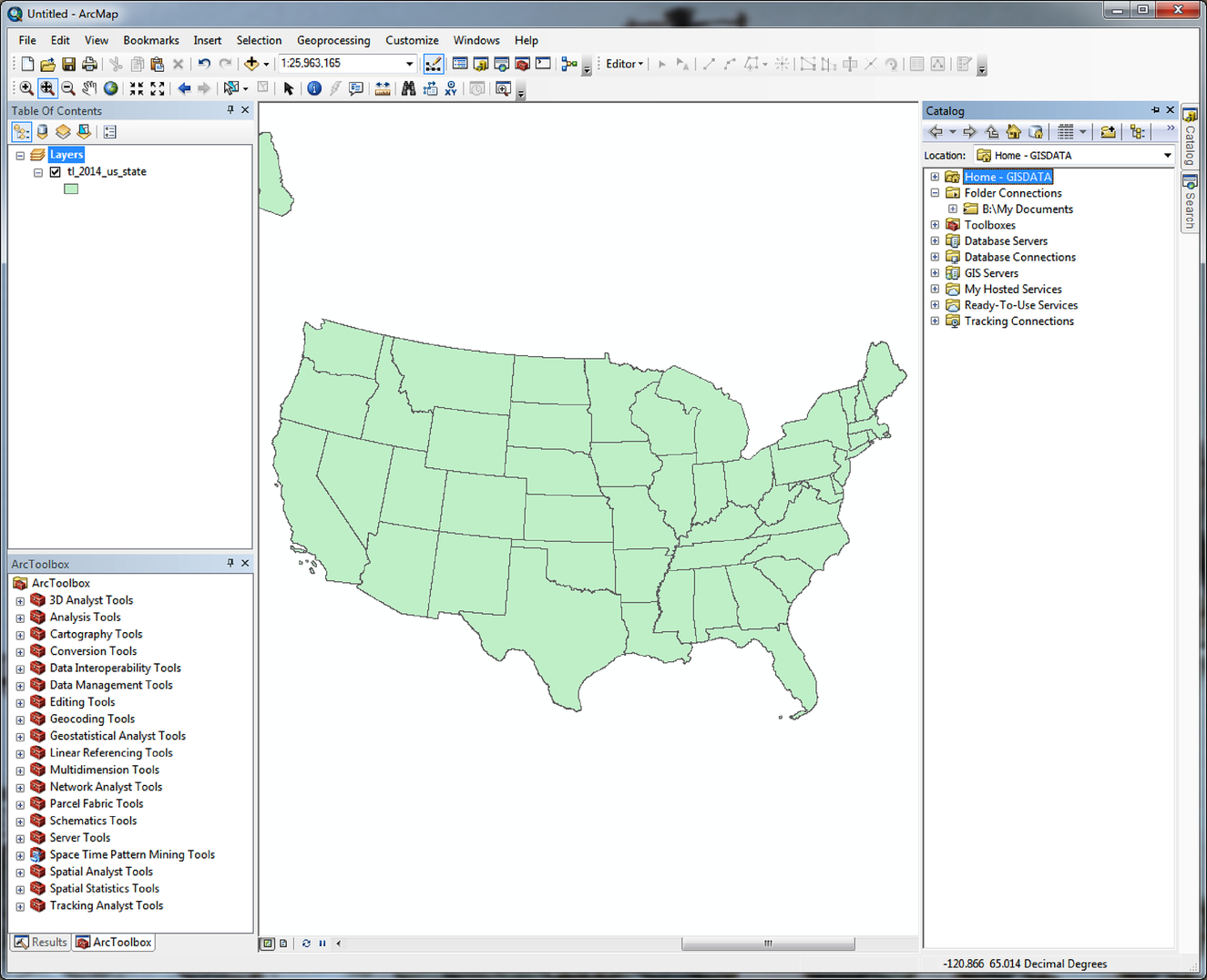

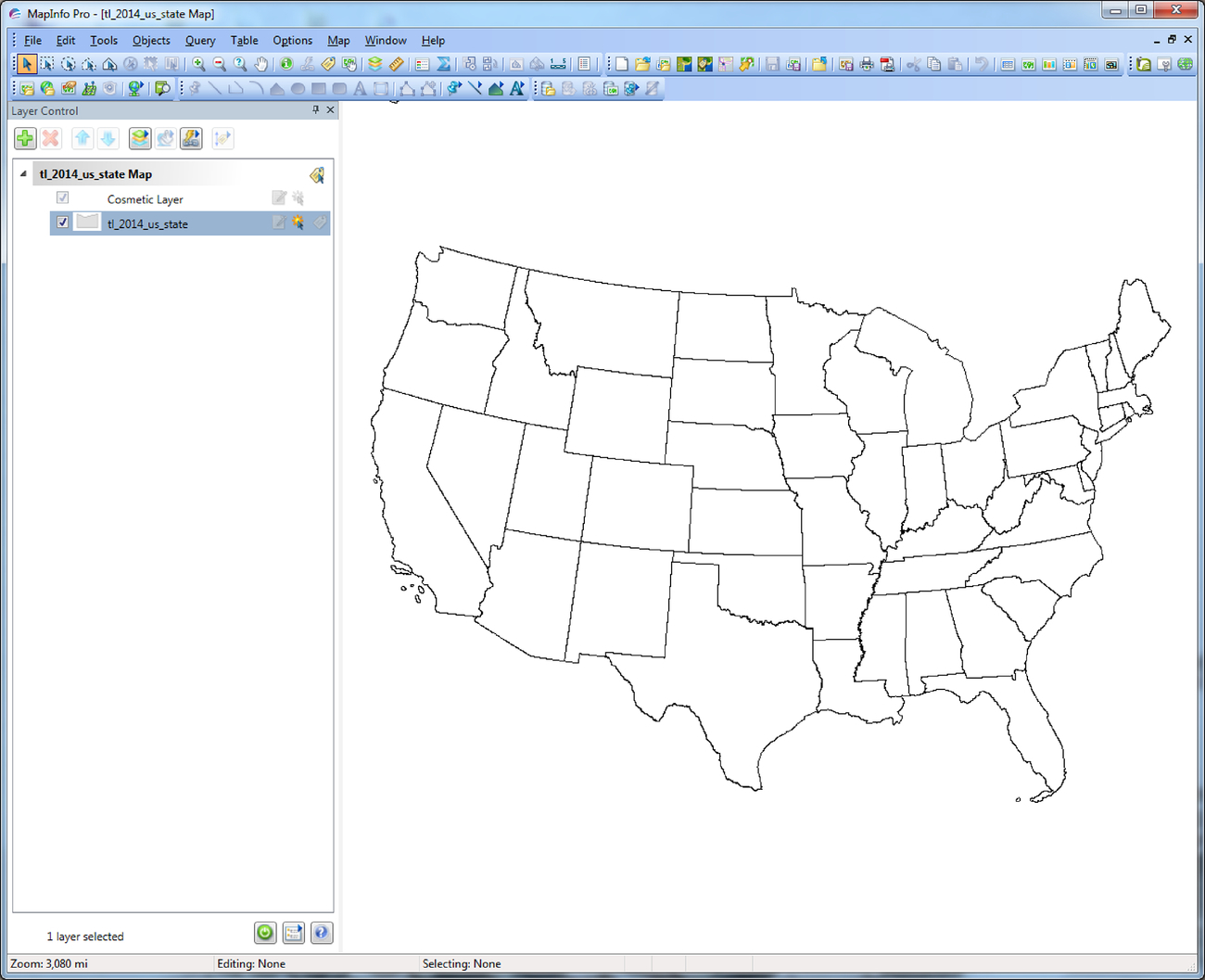

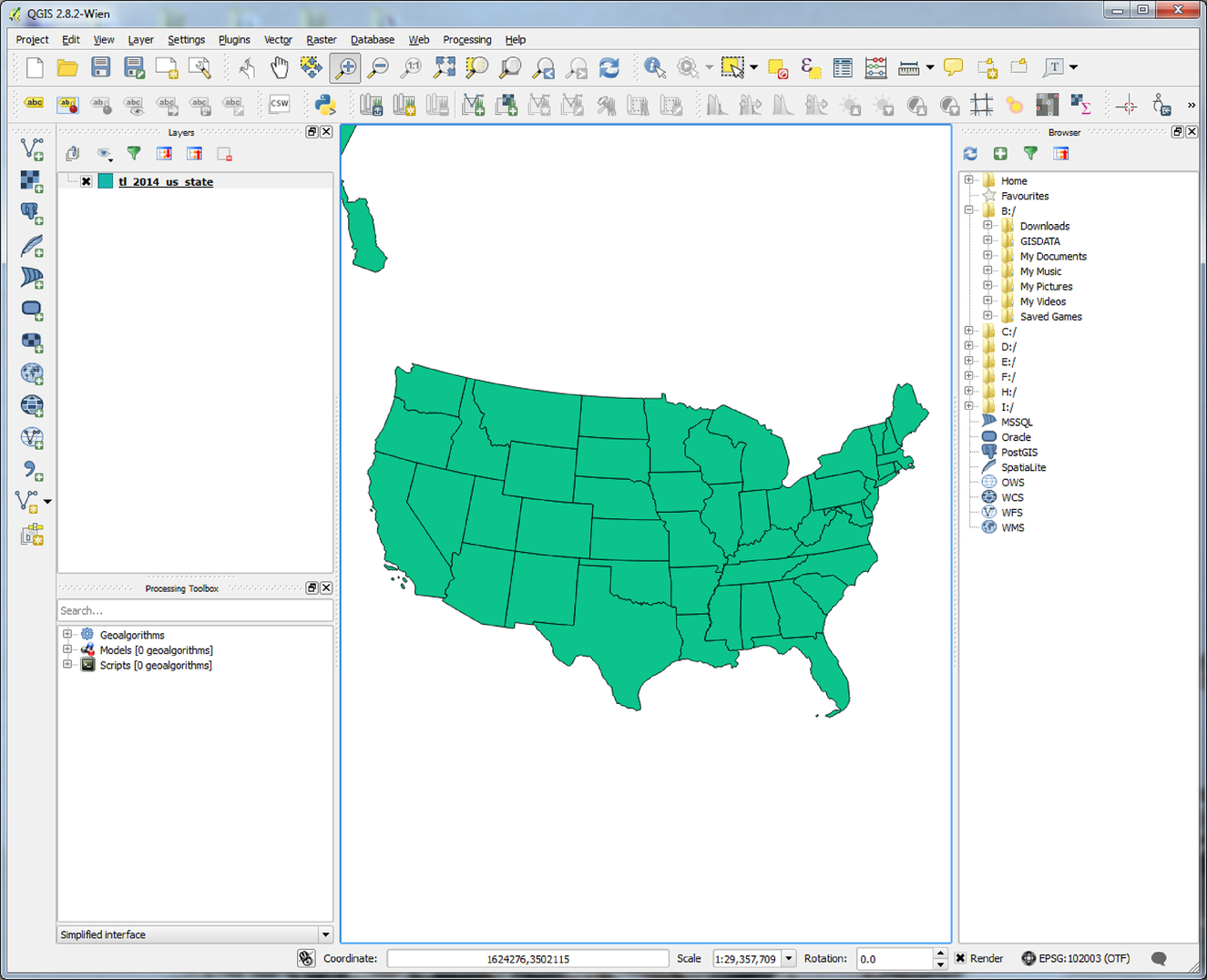

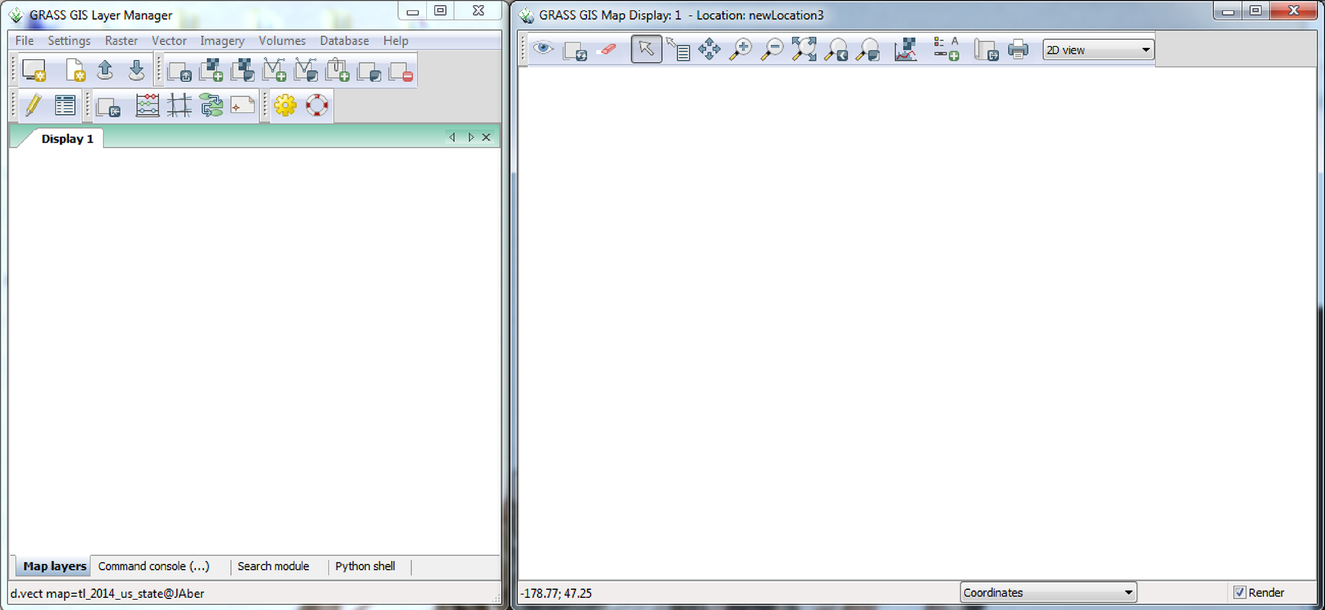

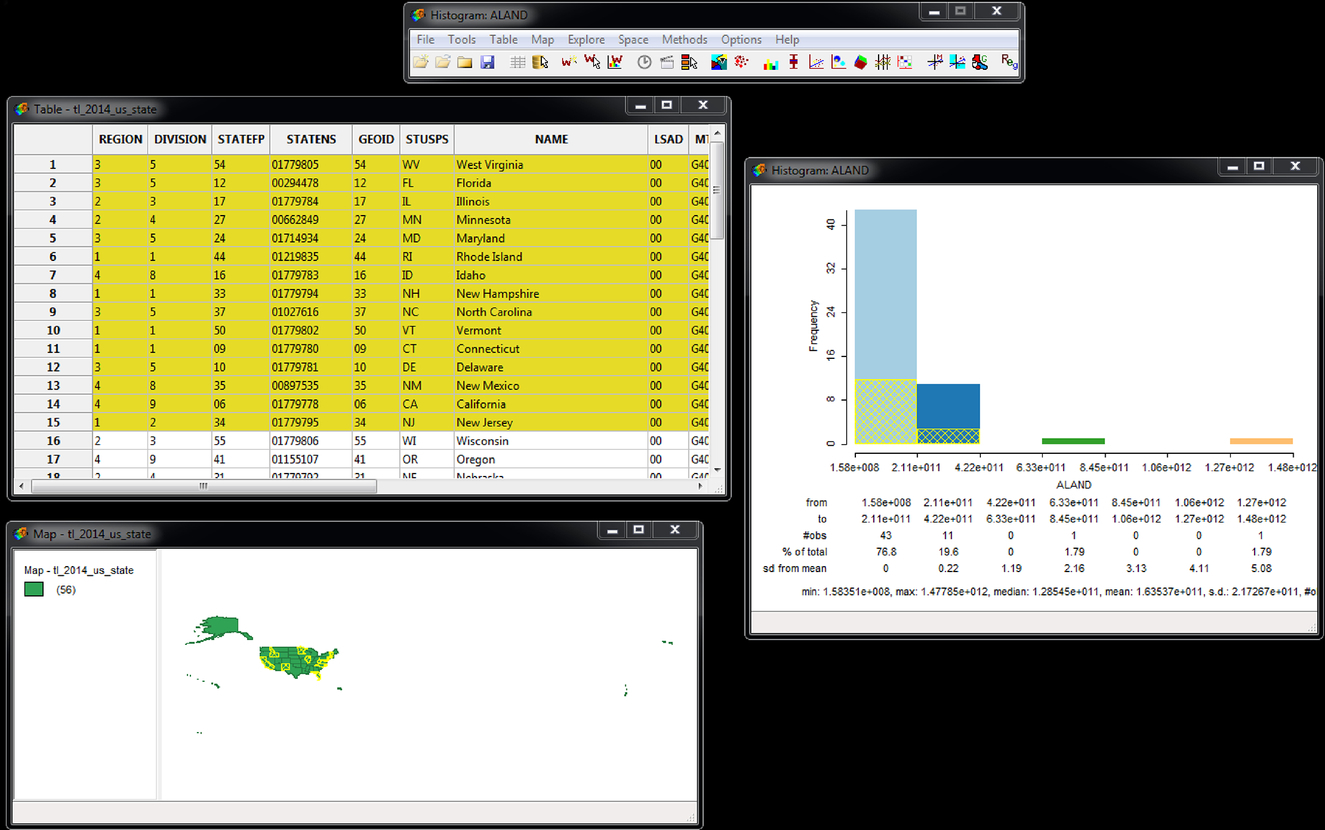

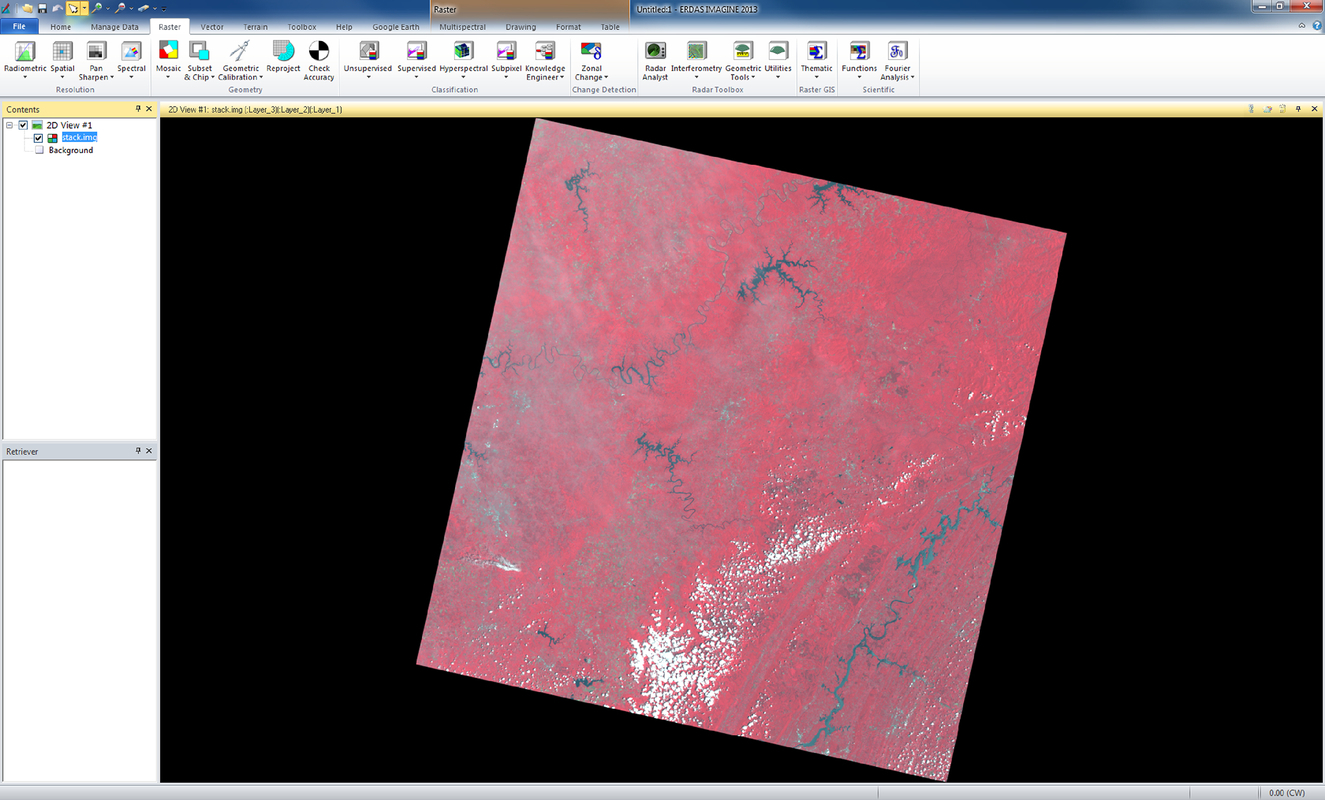

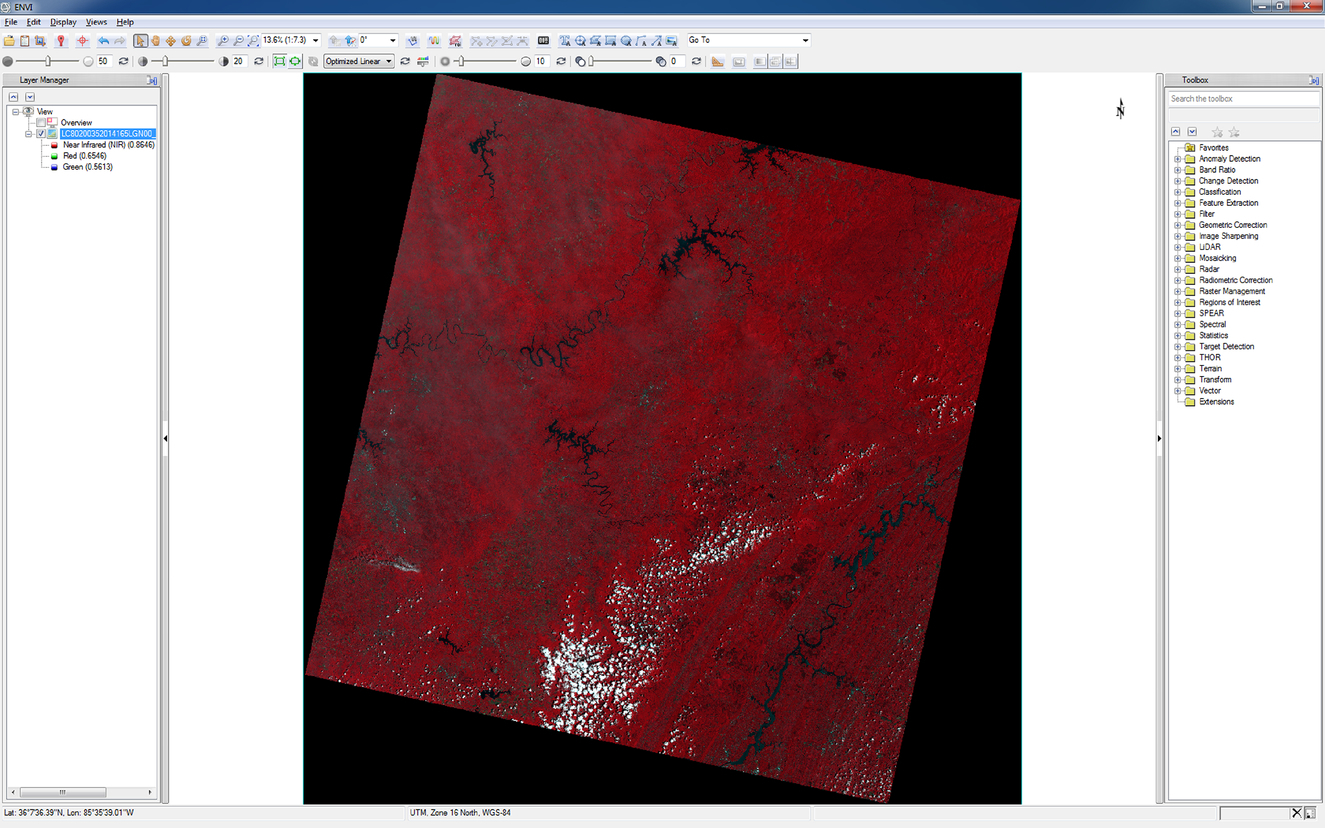

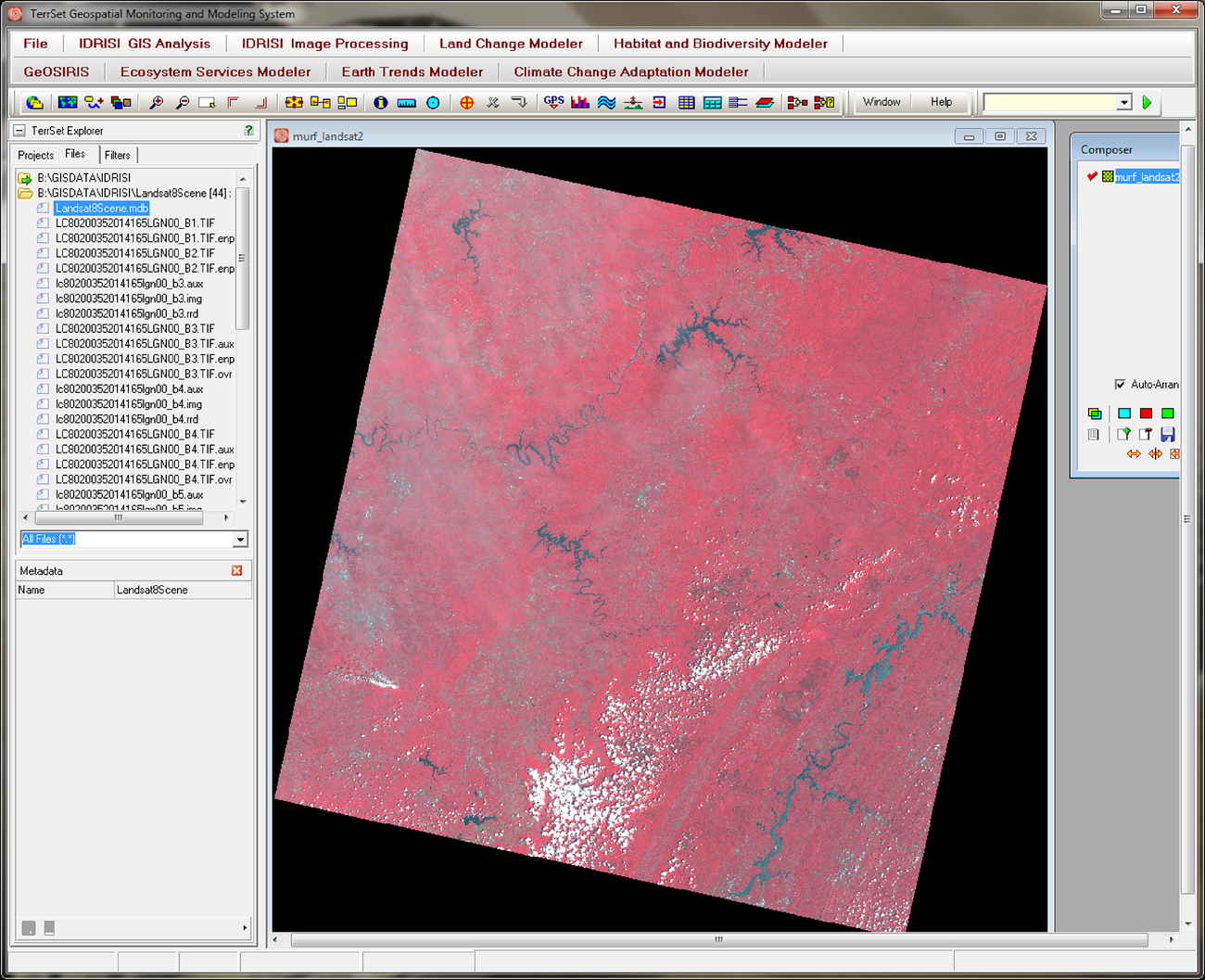

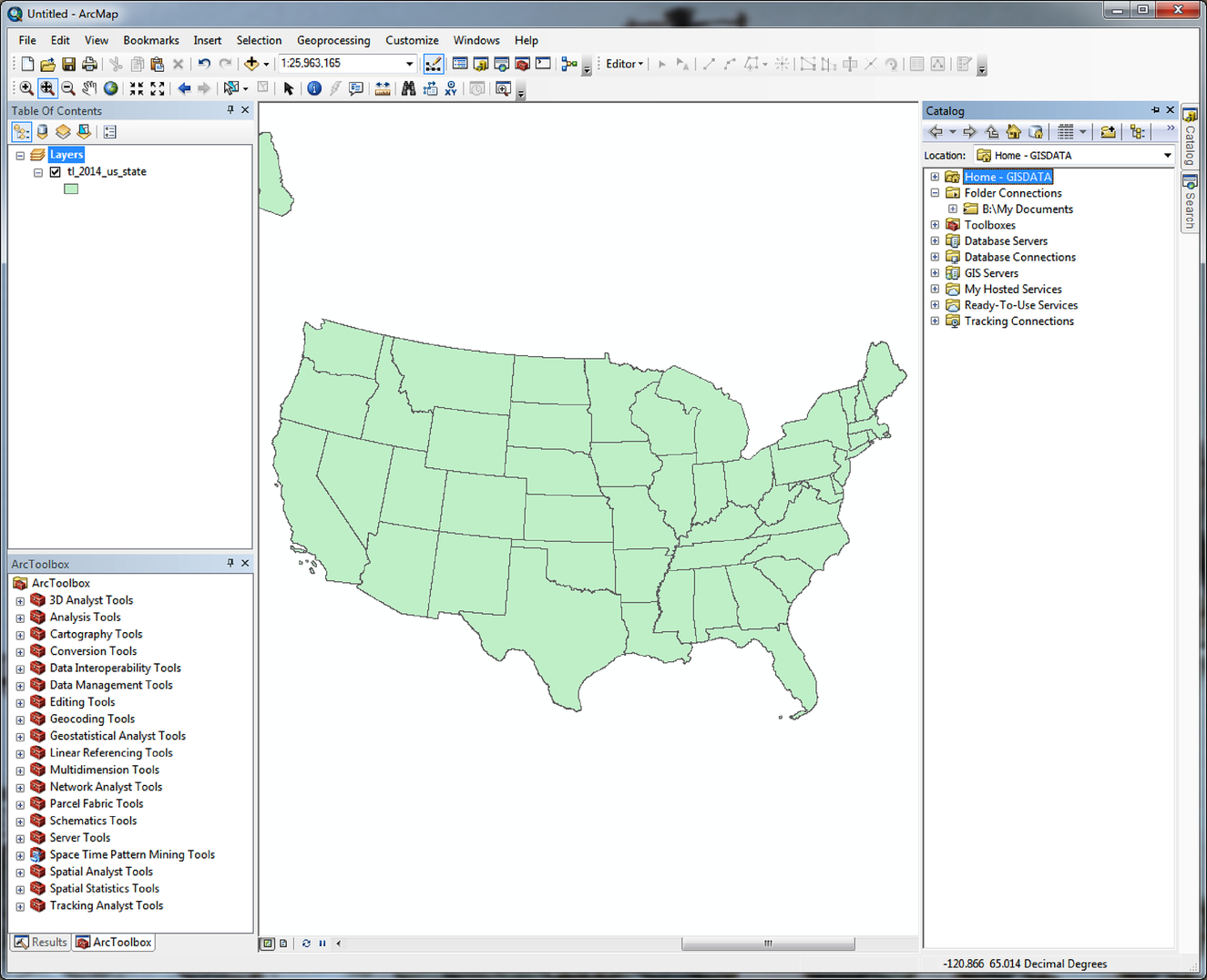

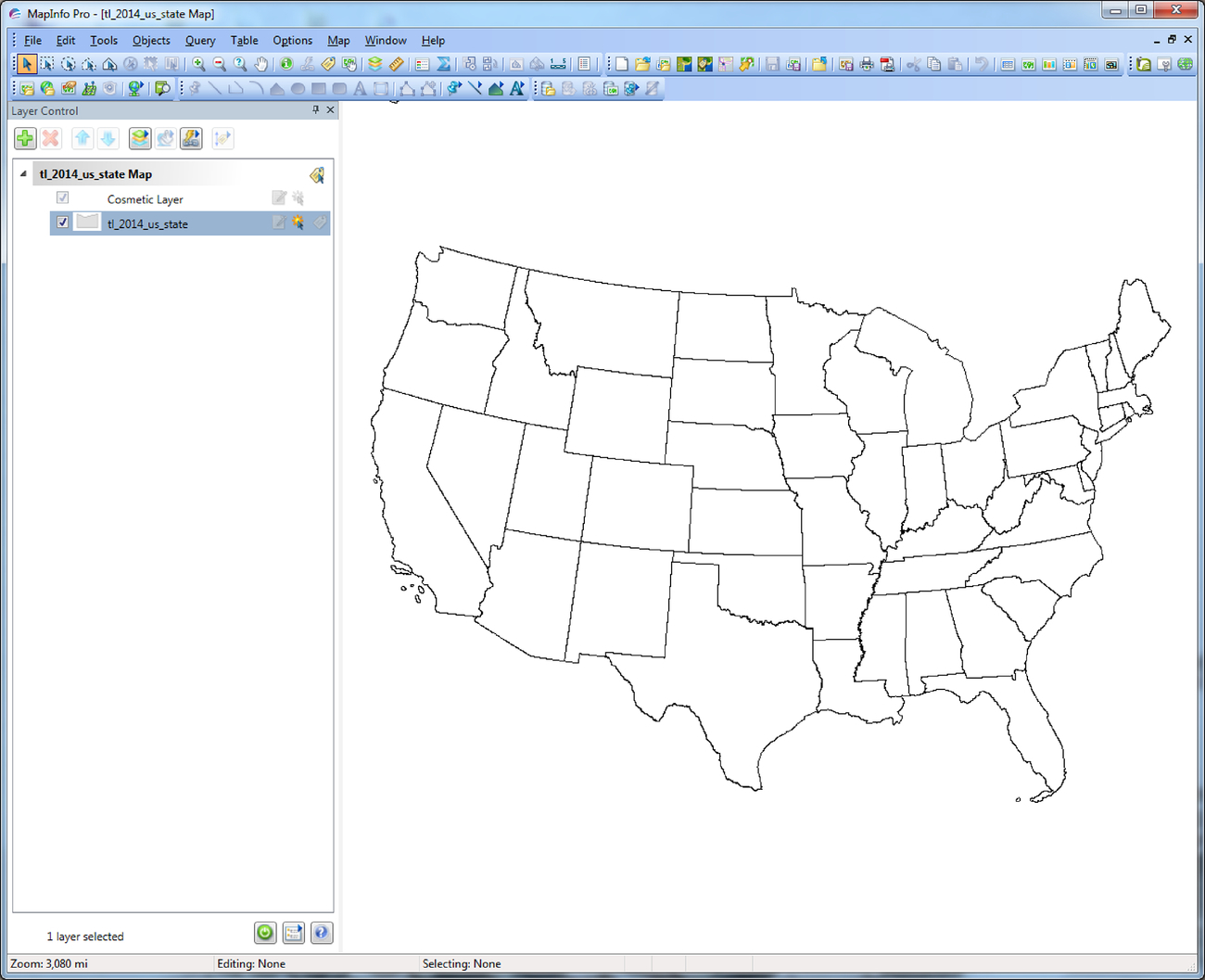

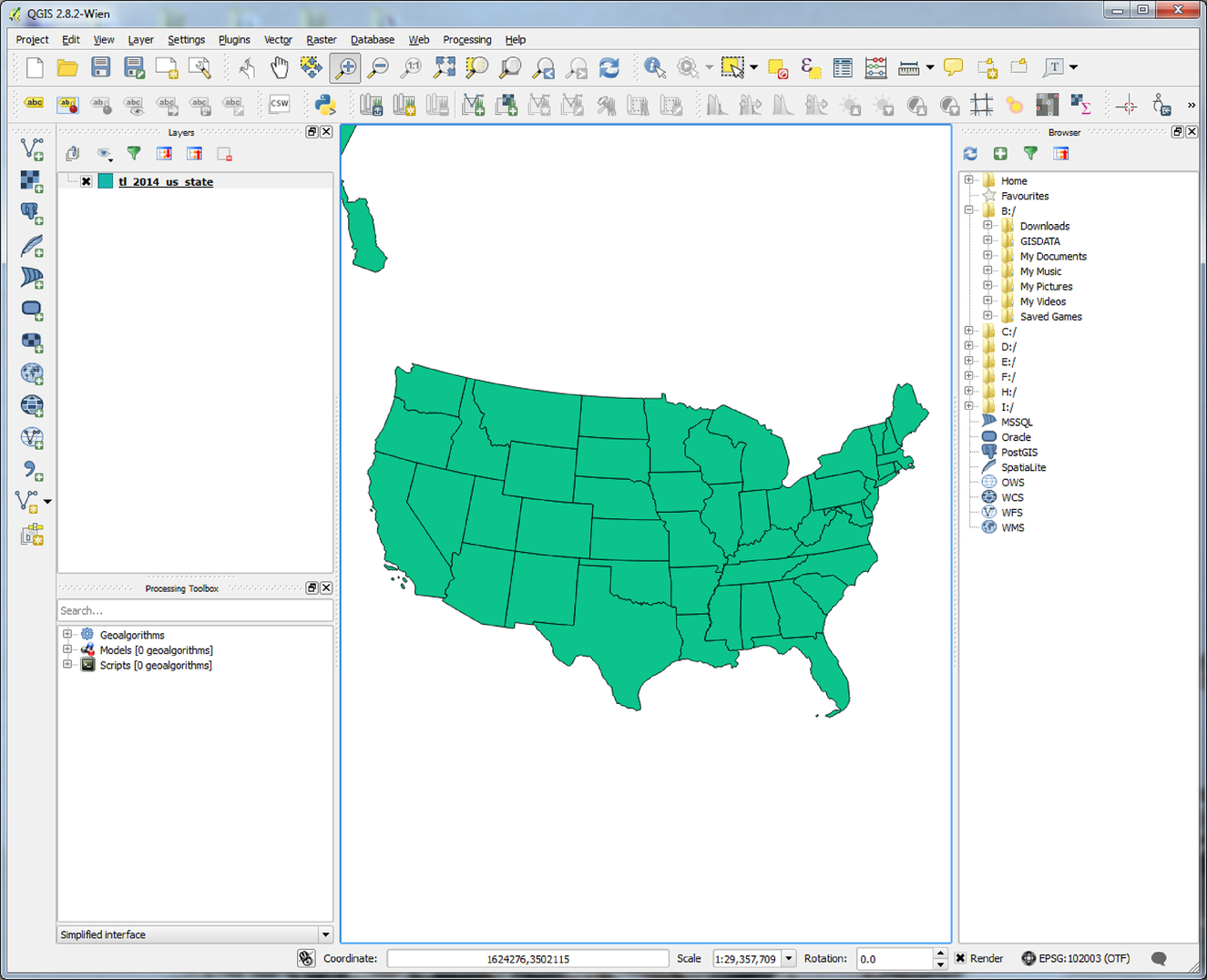

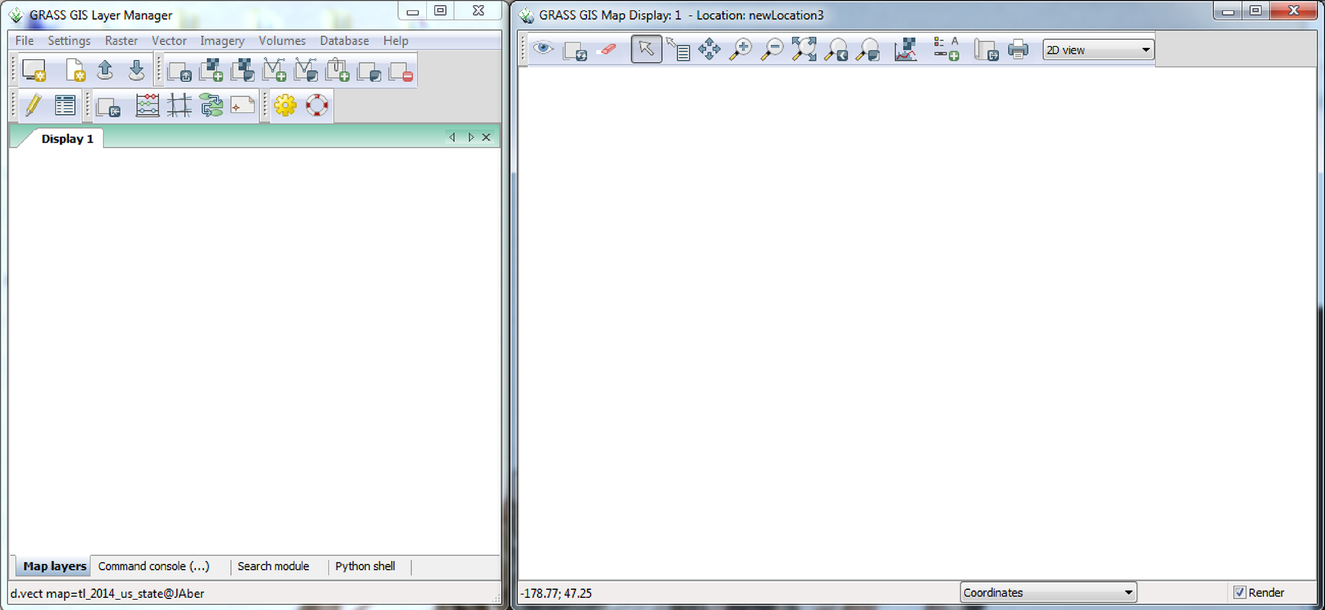

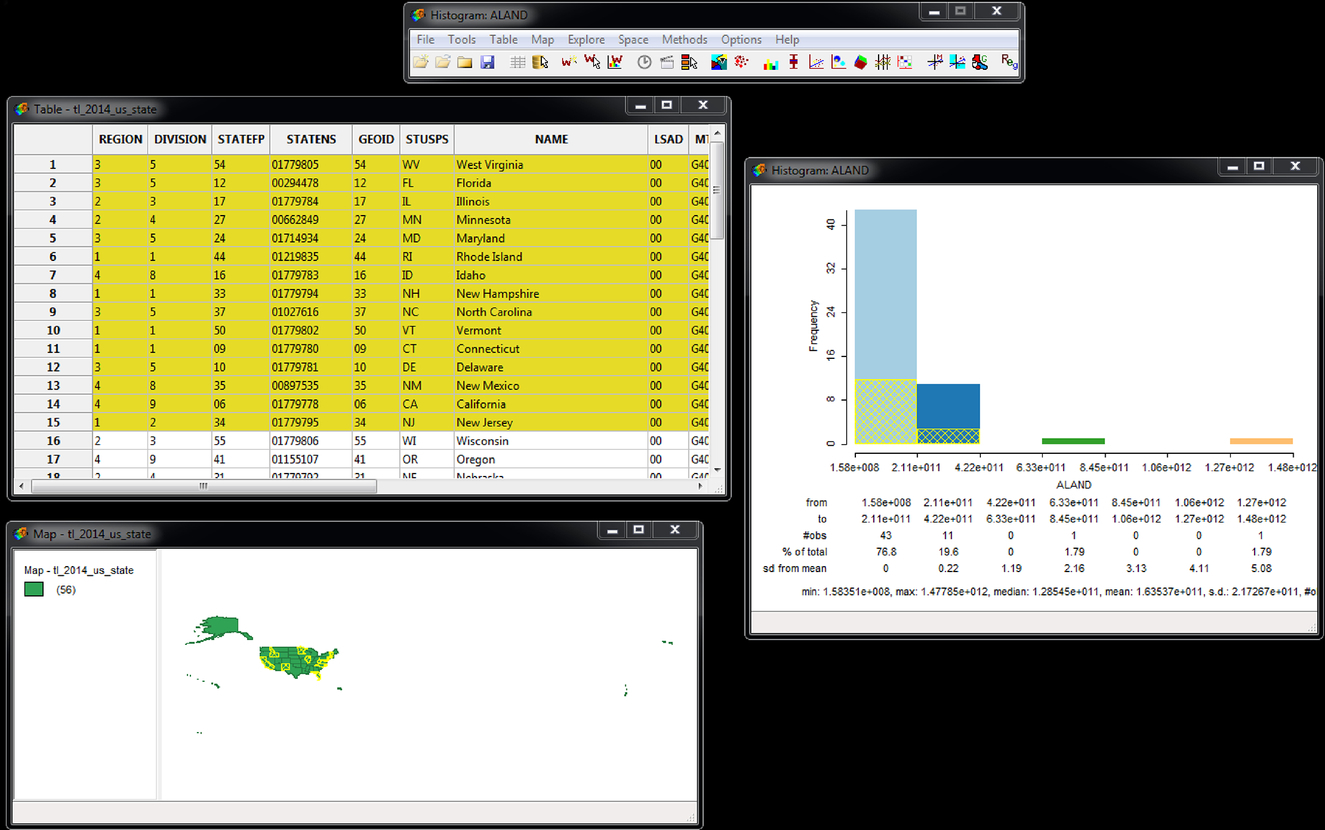

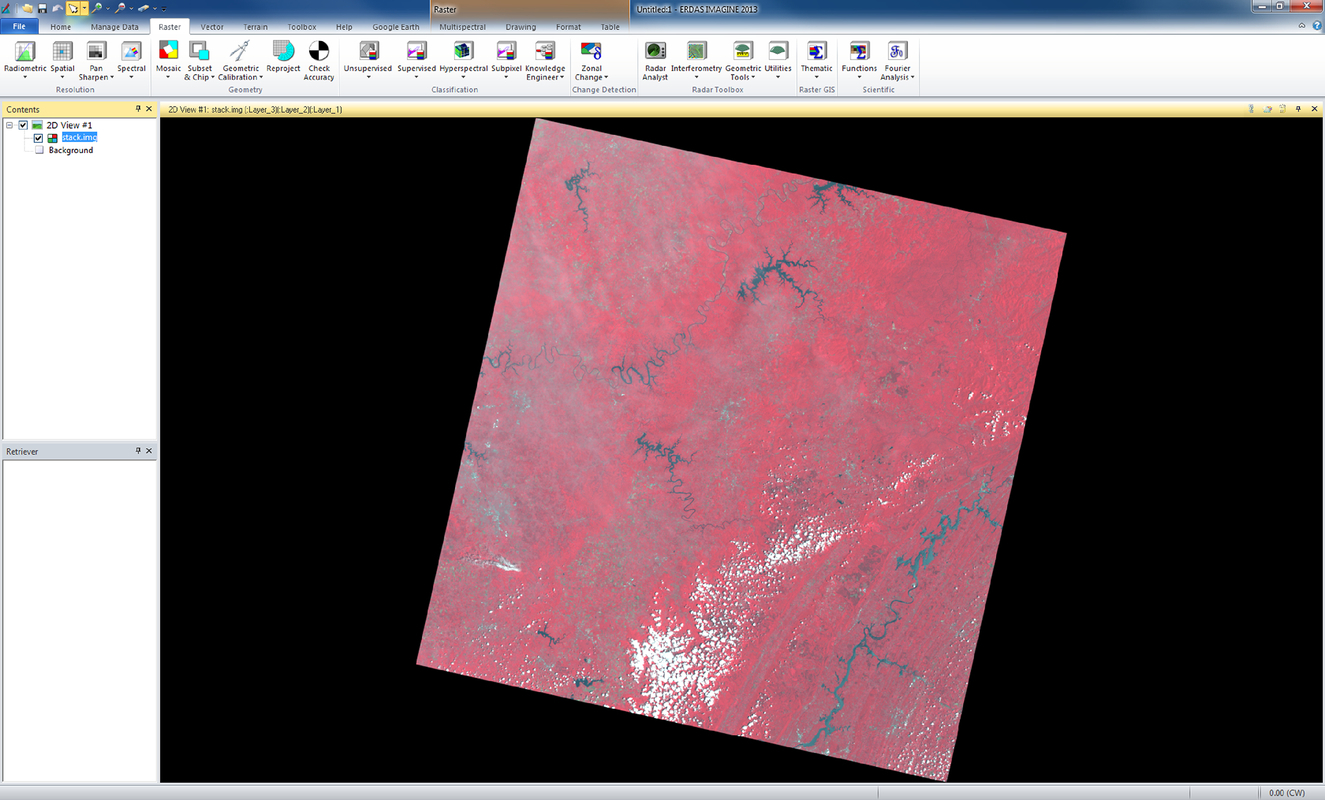

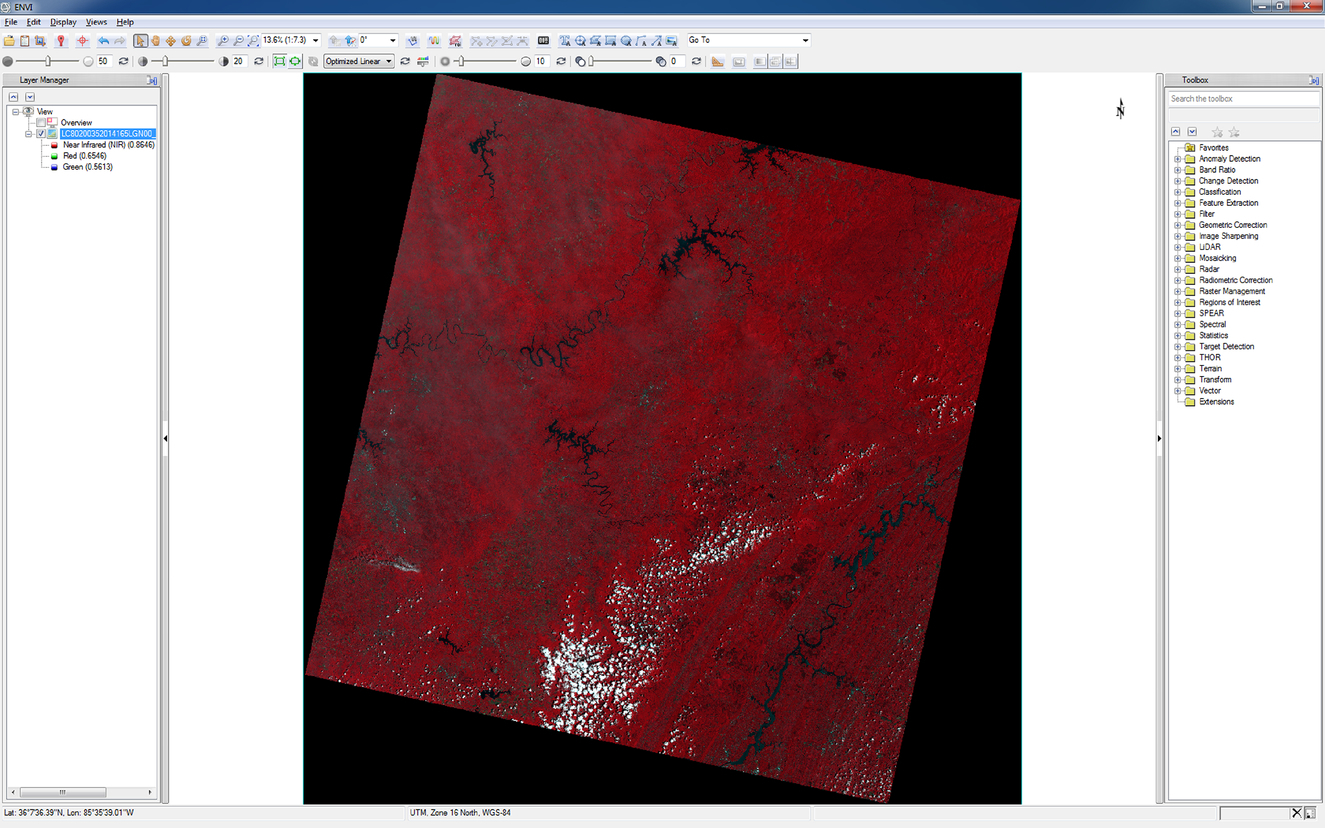

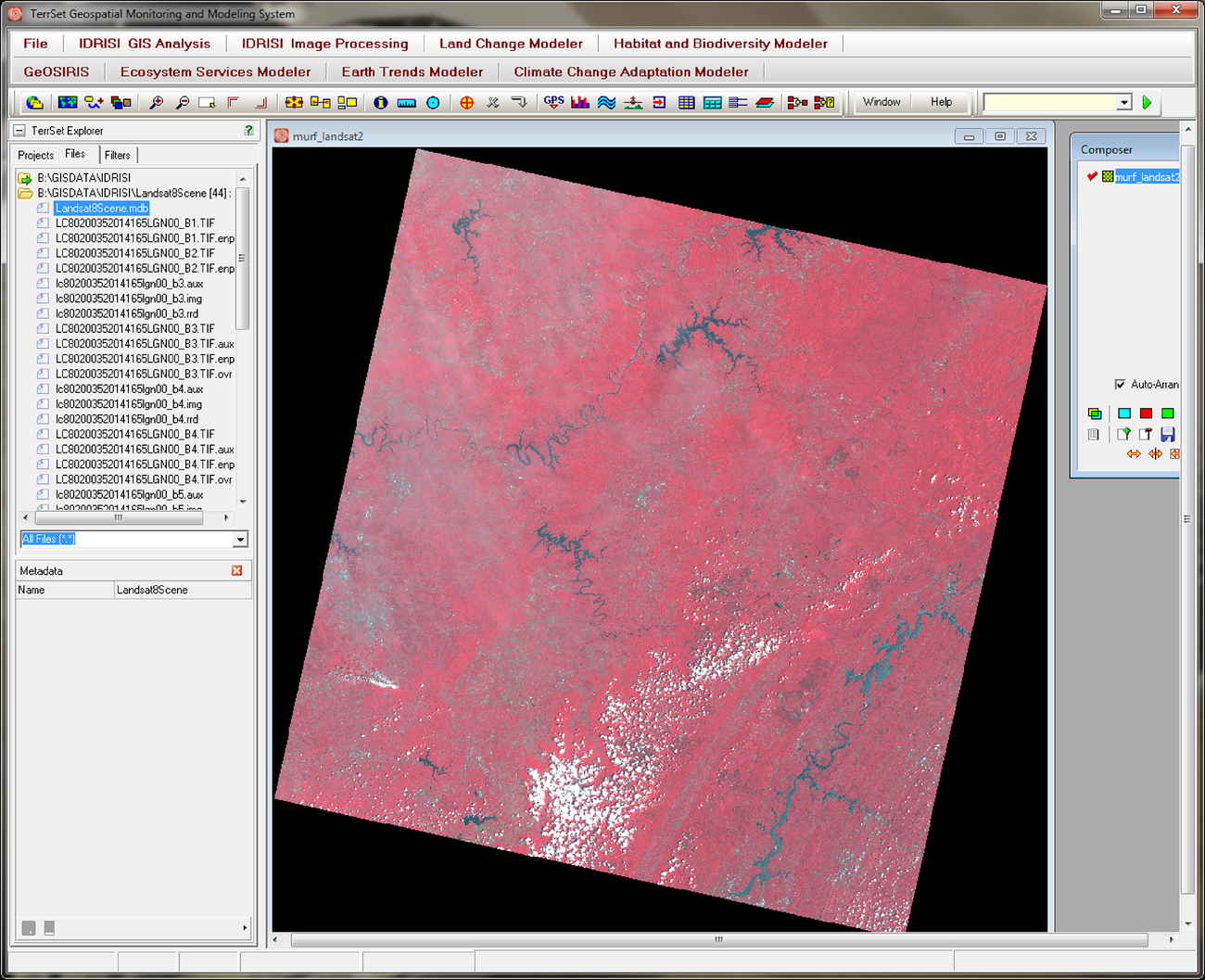

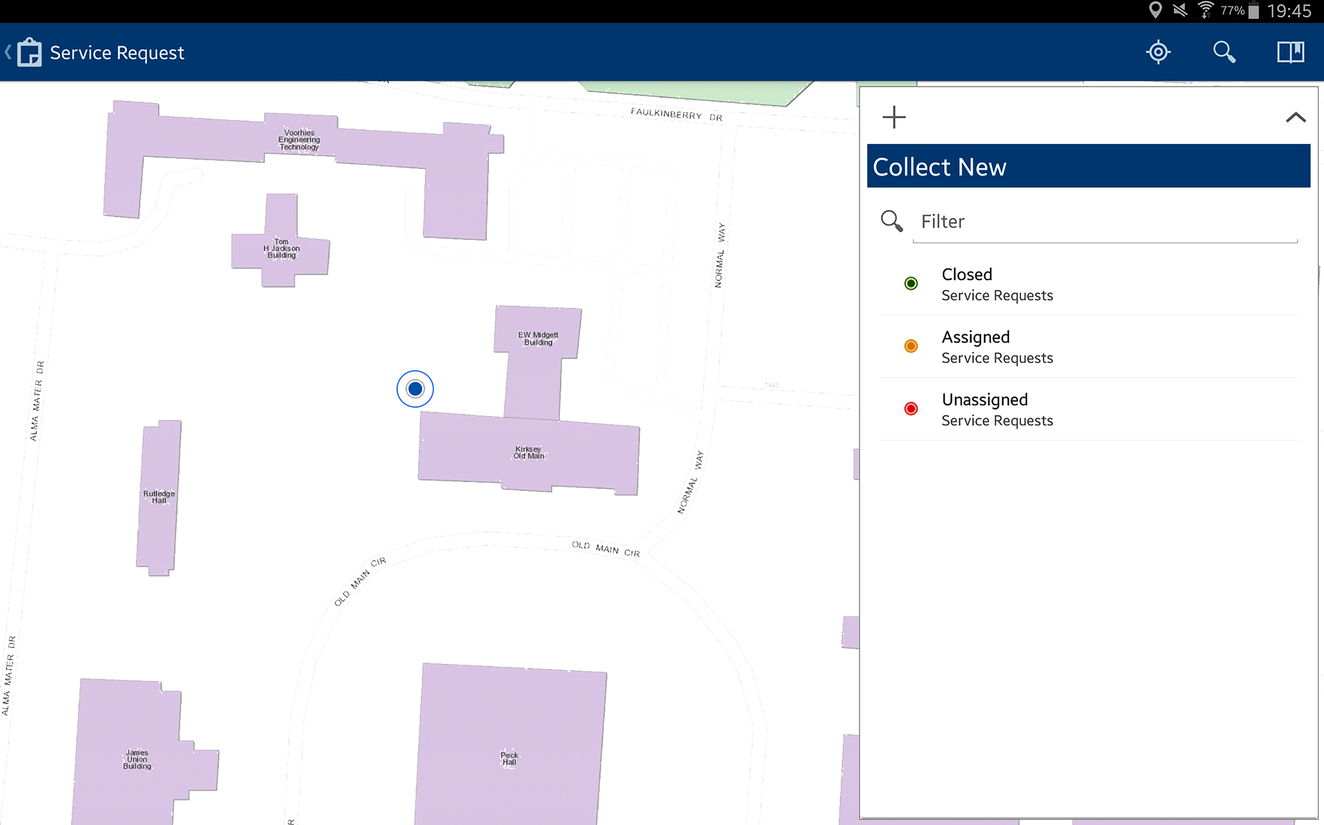

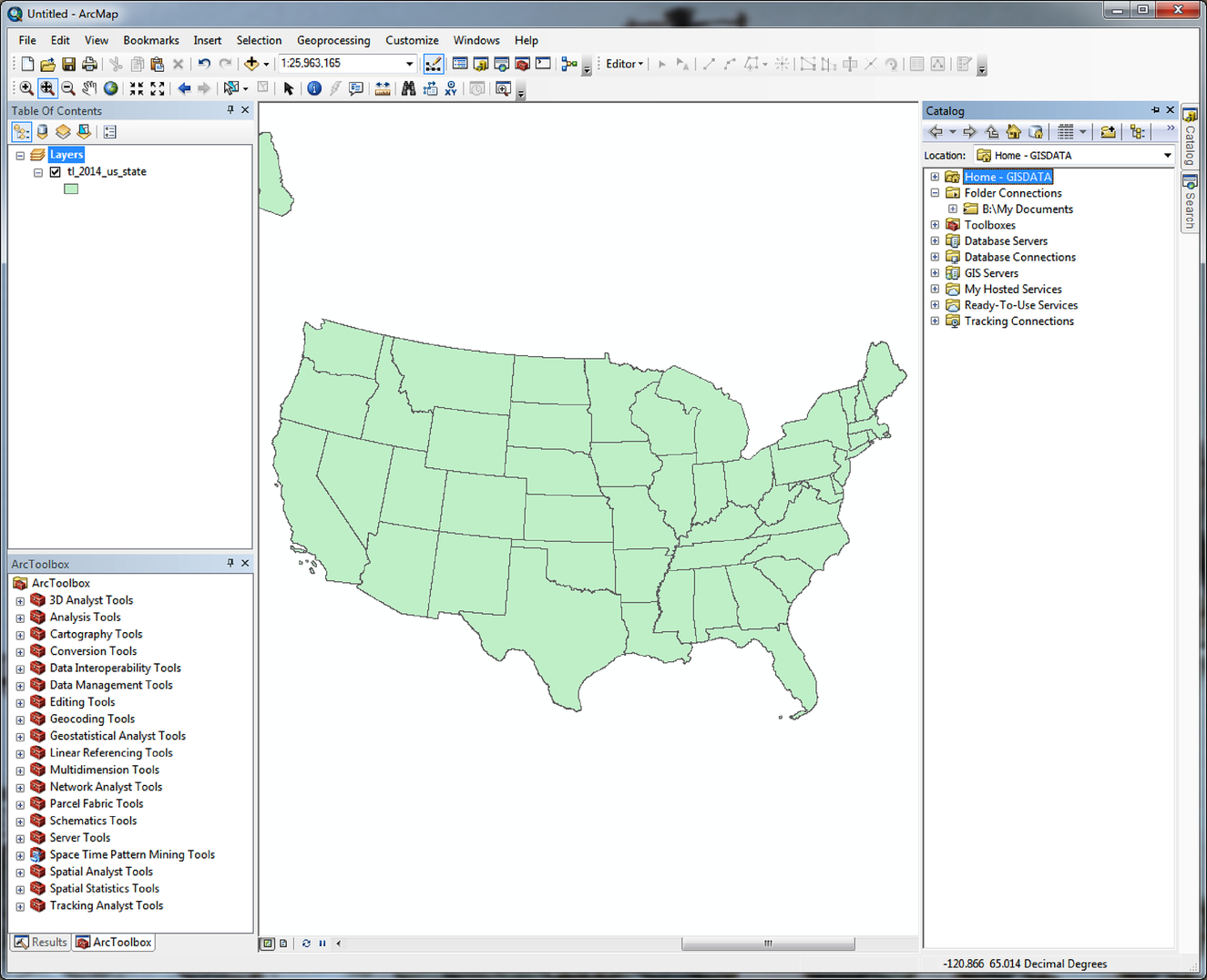

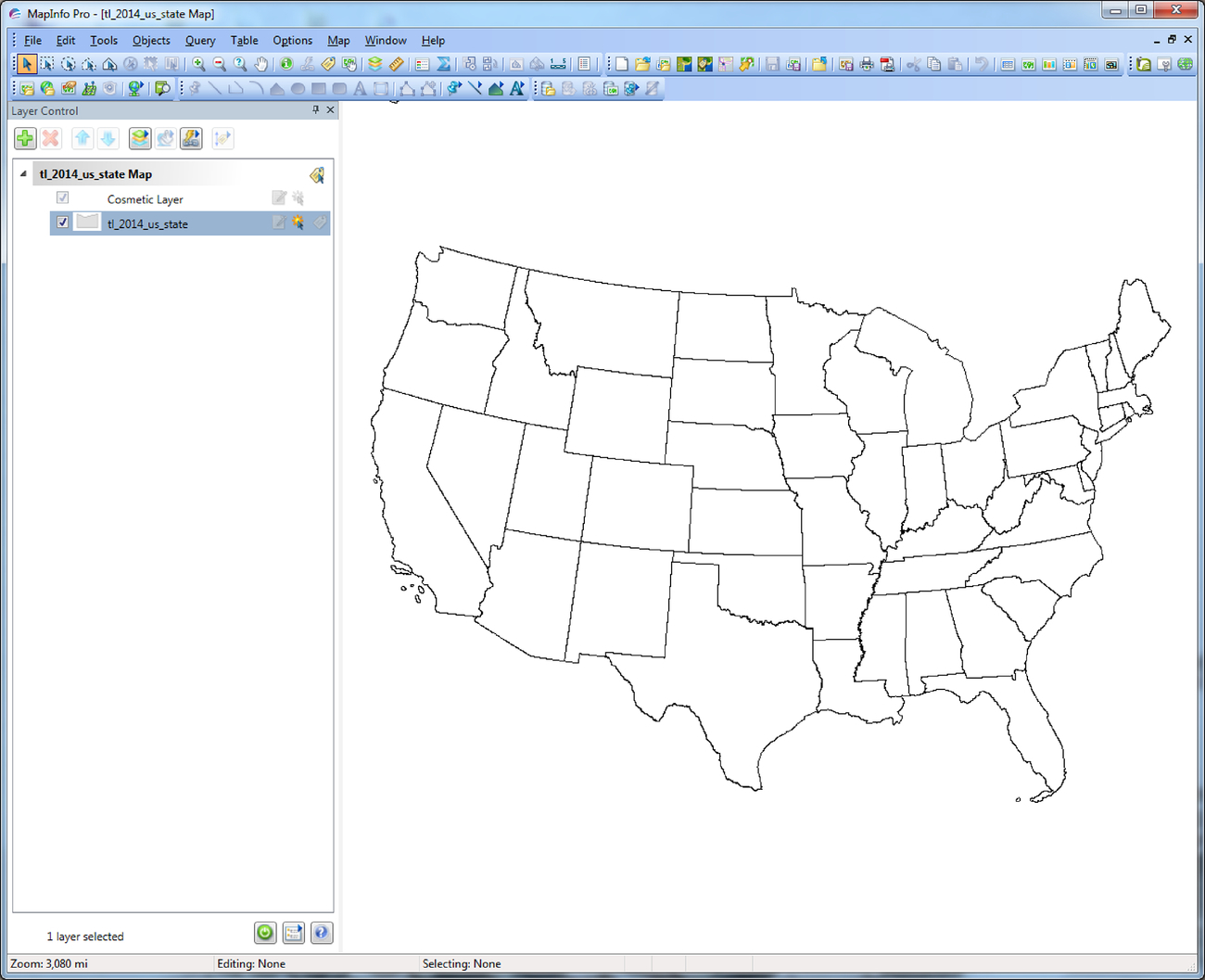

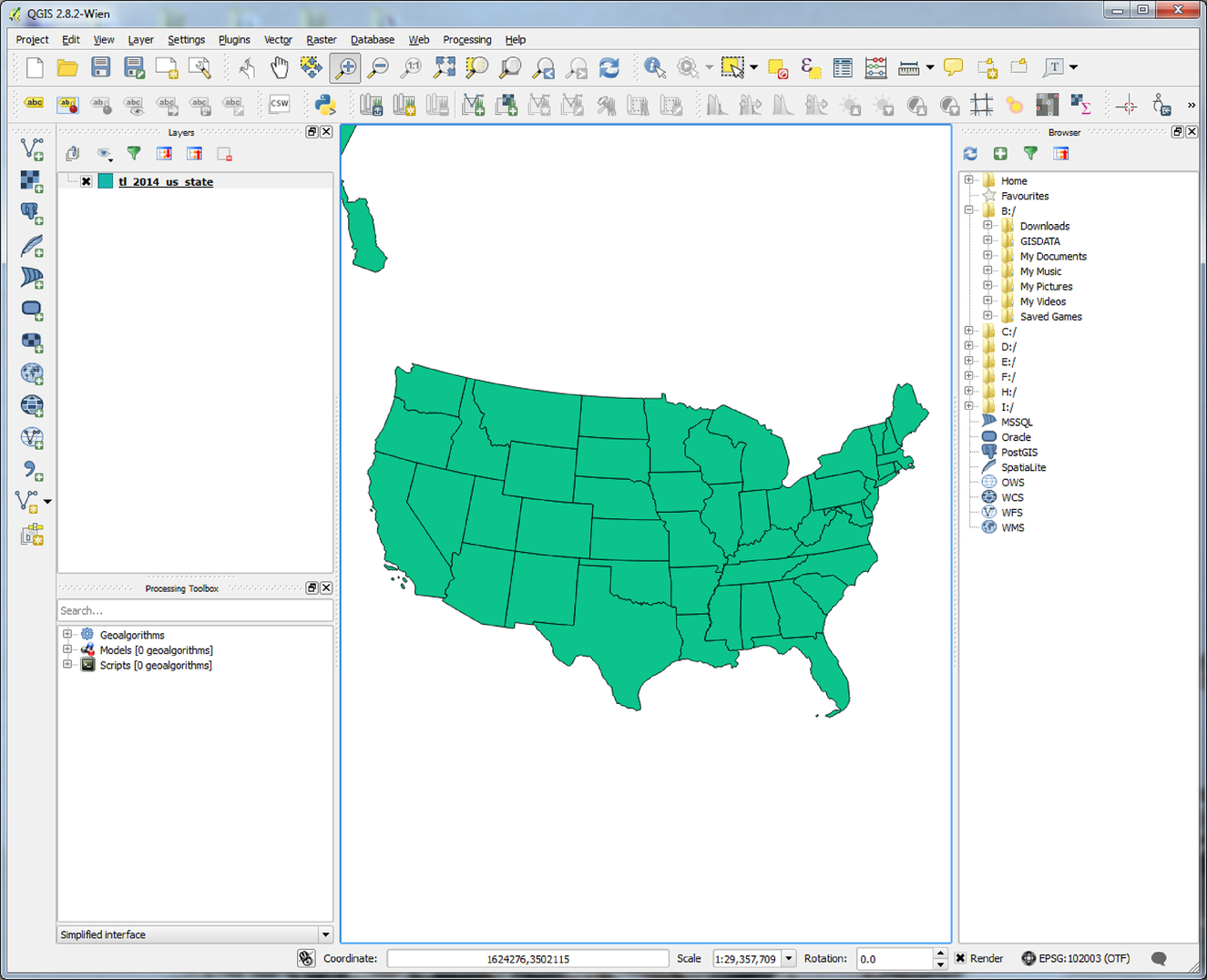

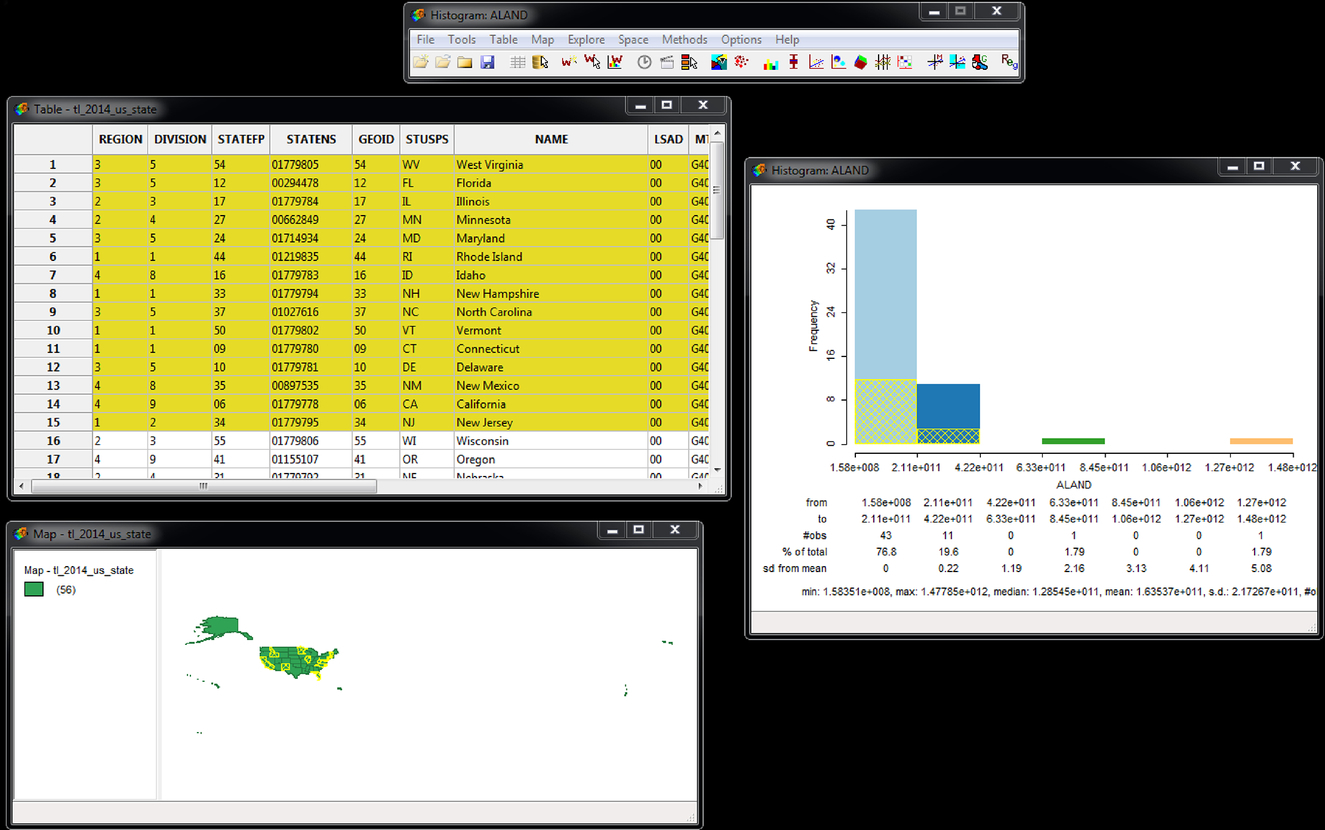

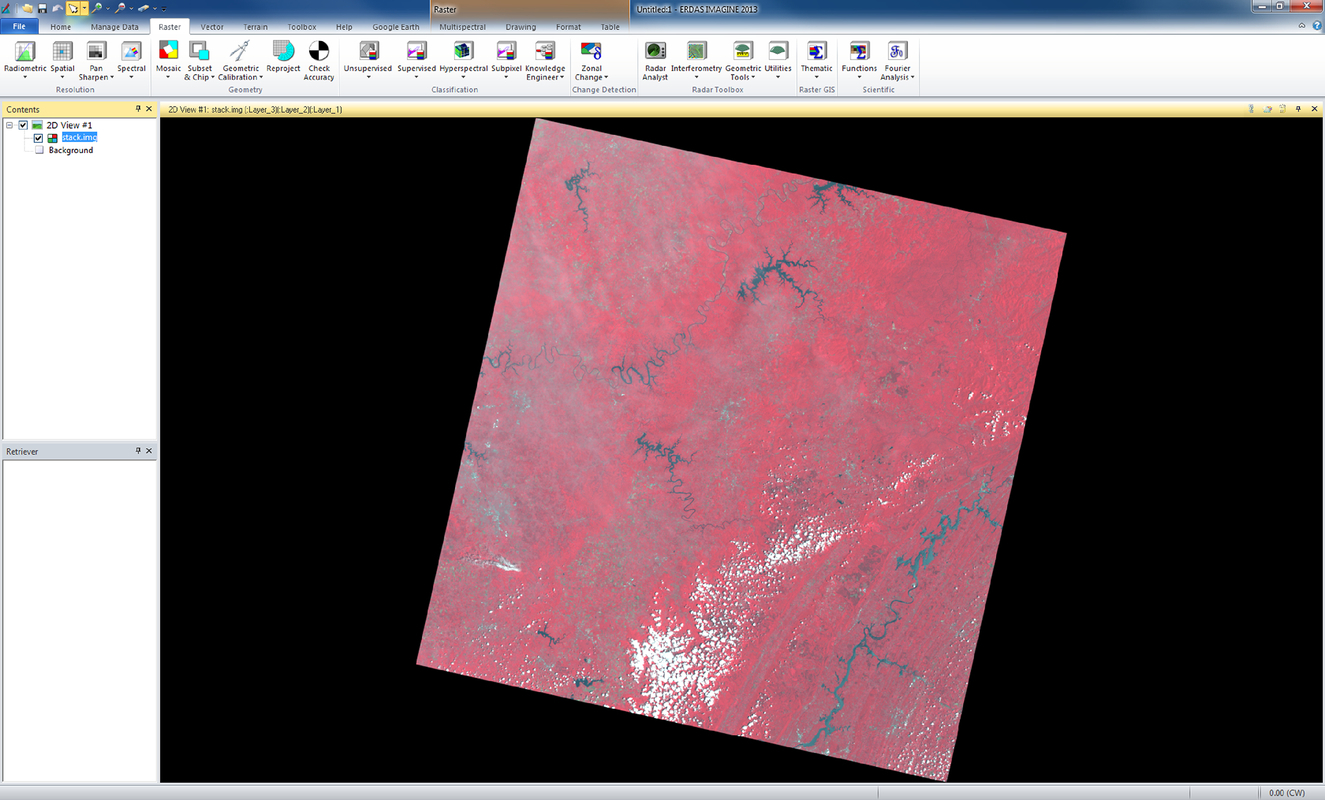

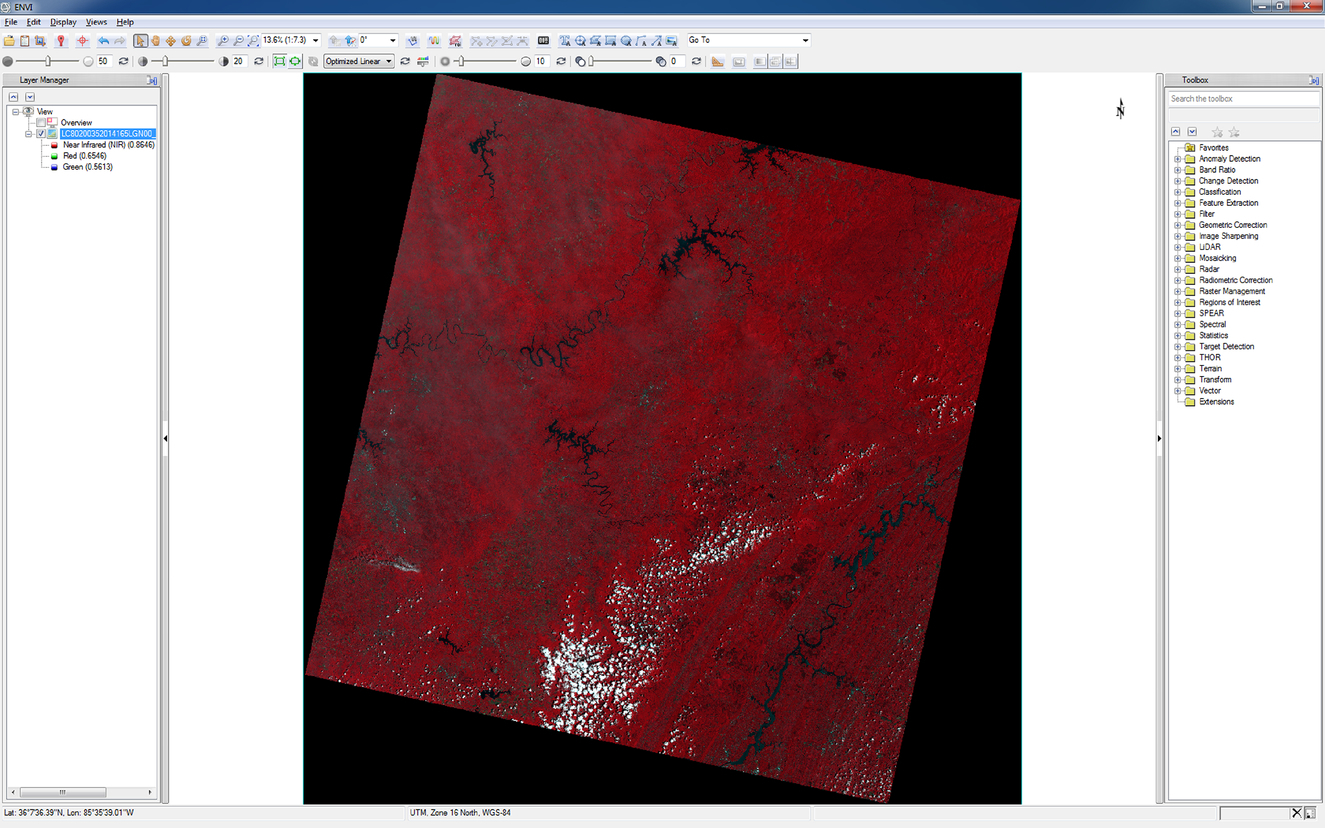

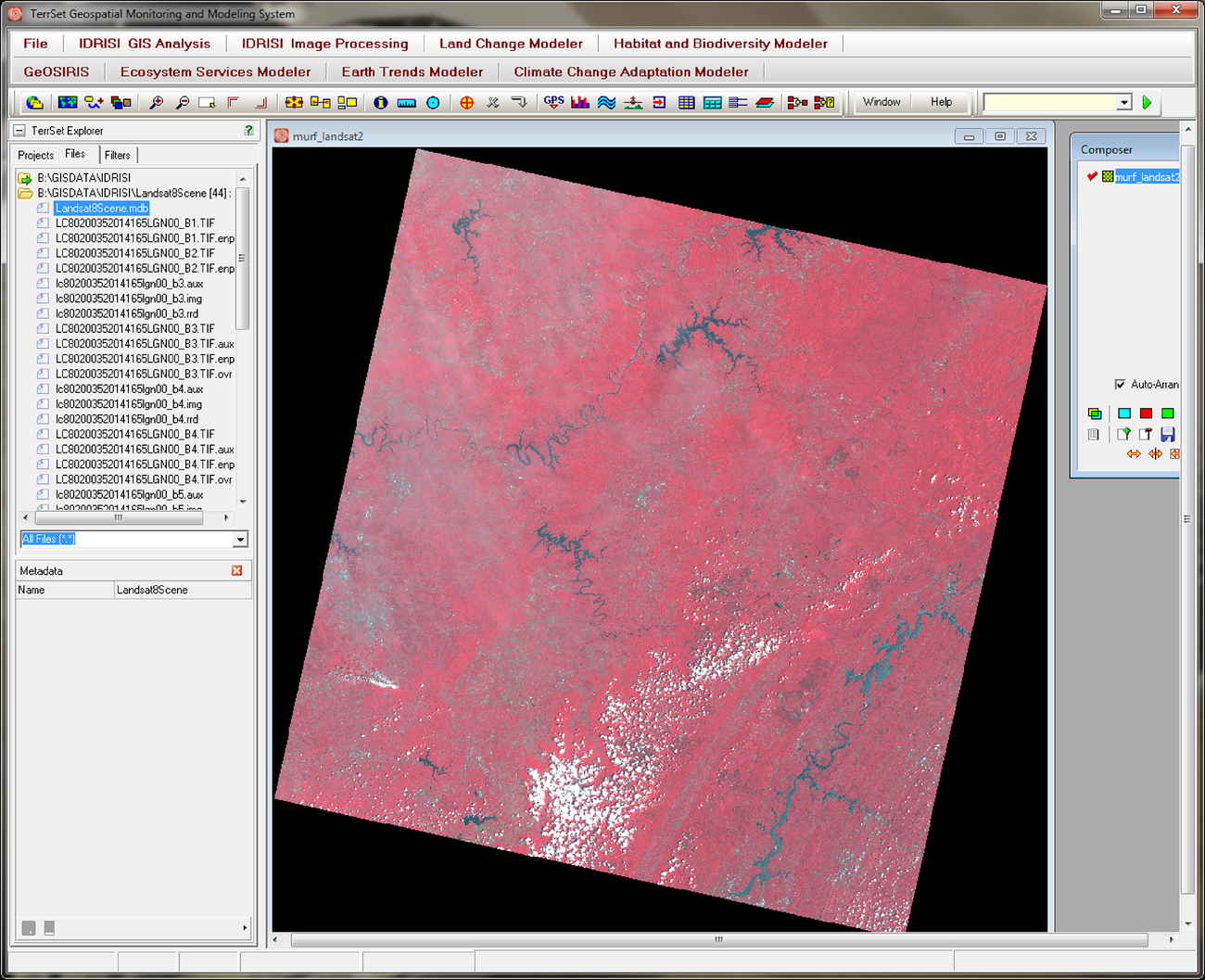

7.4 Guide Through GIS and Remote Sensing Software

7.5 Guide to Finding Maps, Data, and Other Geospatial Resources

8.3 Reference Librarian Duties

8.5 Support Groups for Map Librarianship

8.6 Citing and Referencing Maps and Geospatial Data

Chapter 9: Collection Development

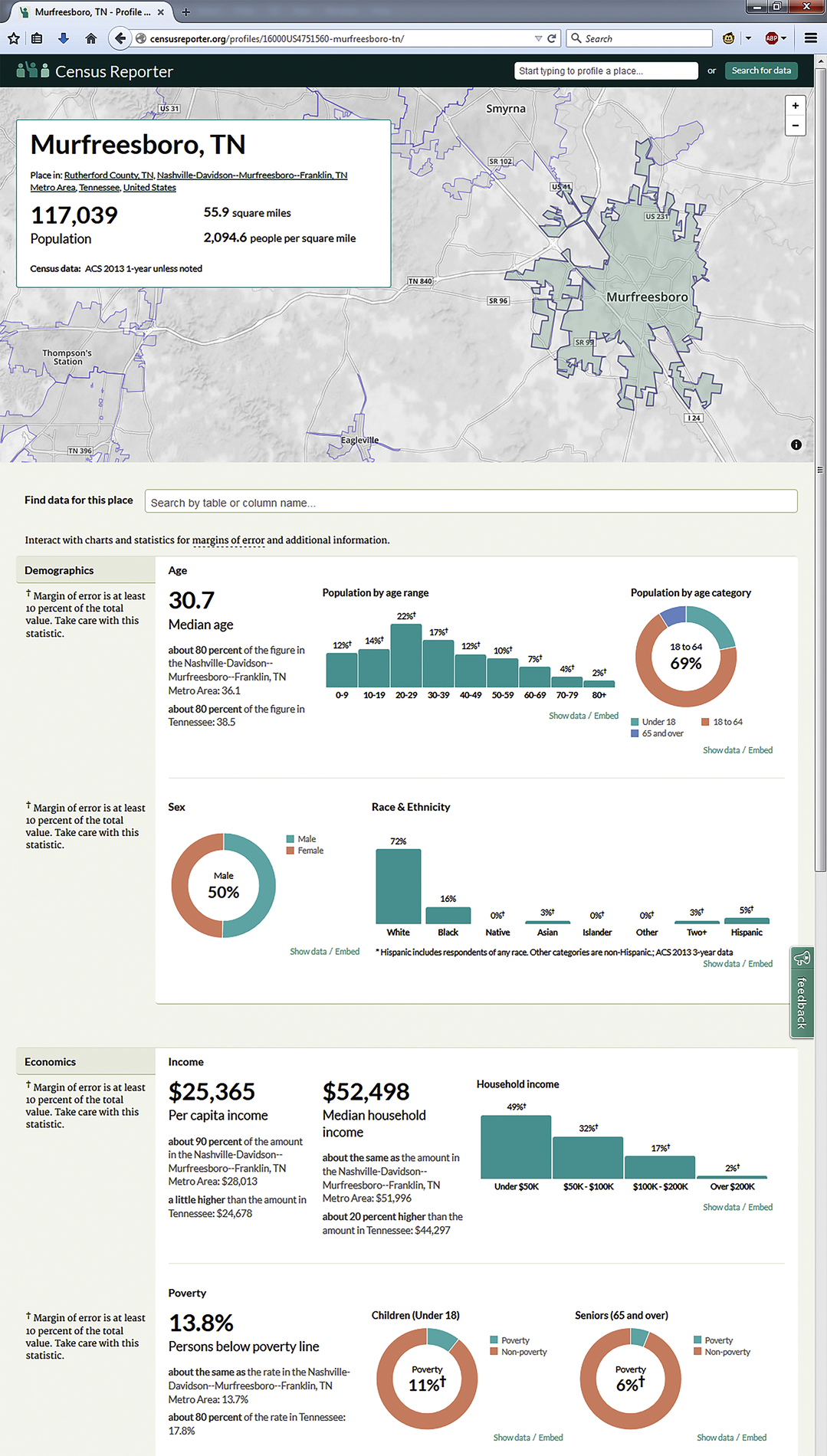

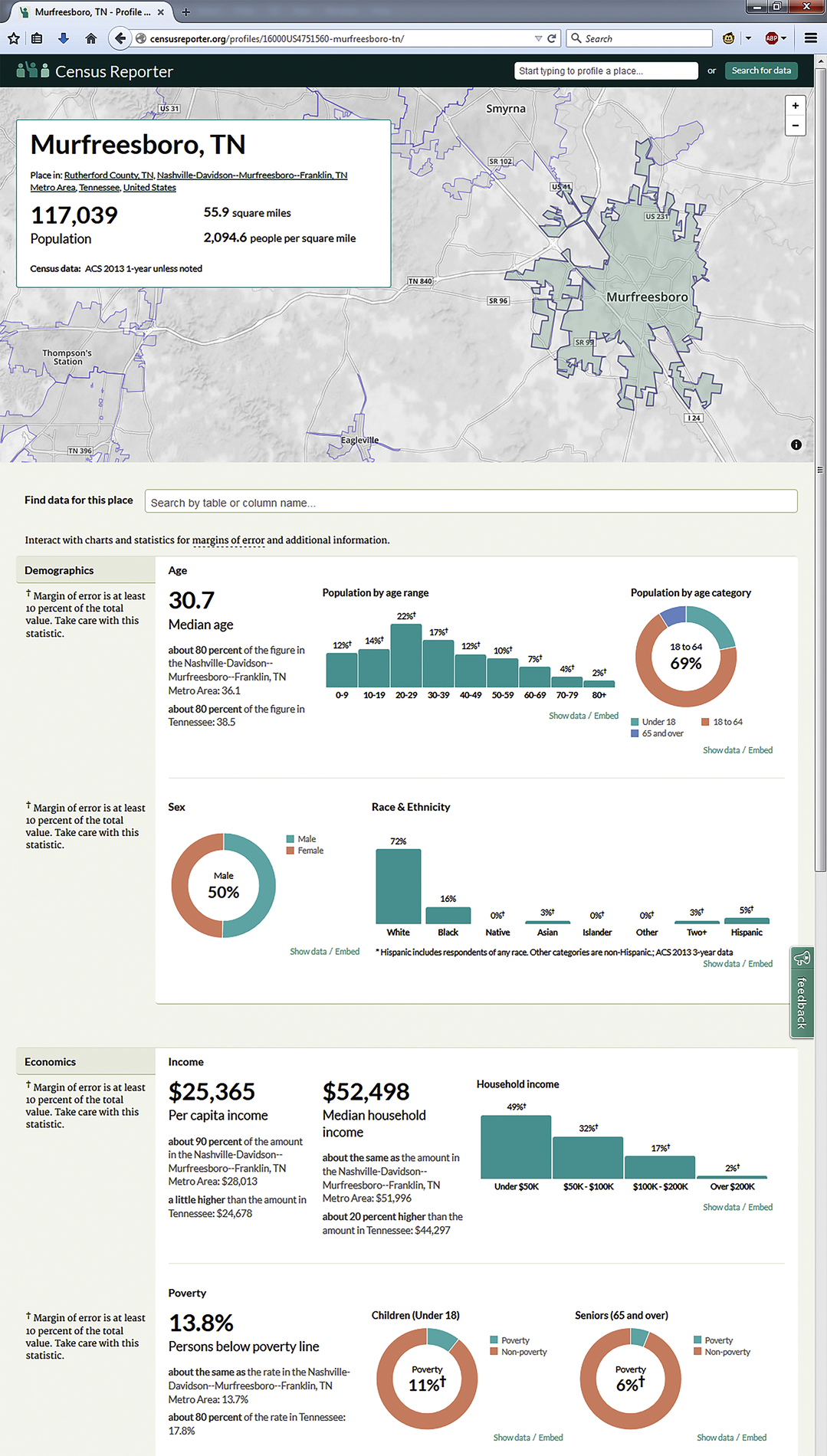

9.2 Knowing Users and Use of Map and GIS Resources

9.3 Collection Development Policy

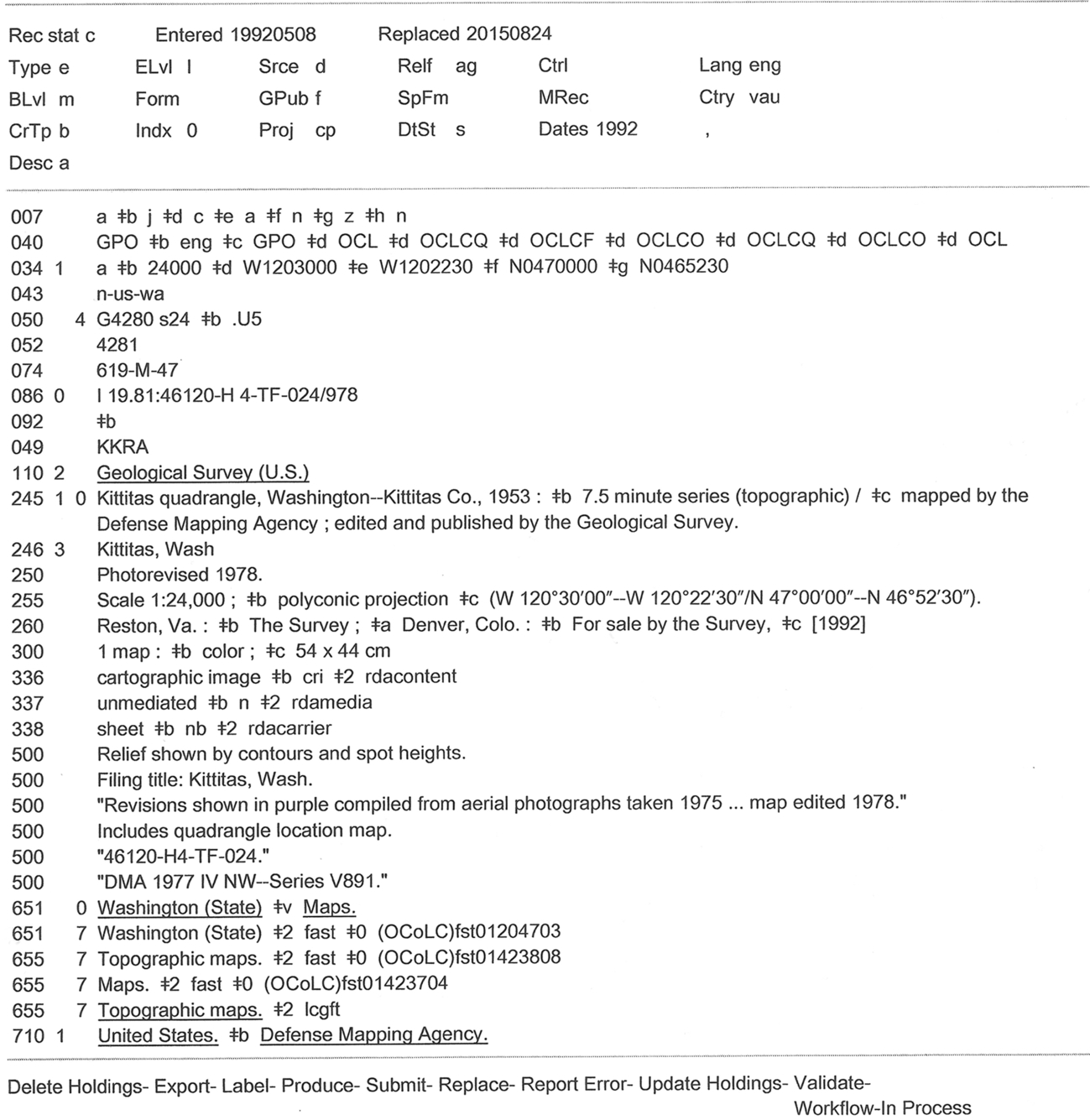

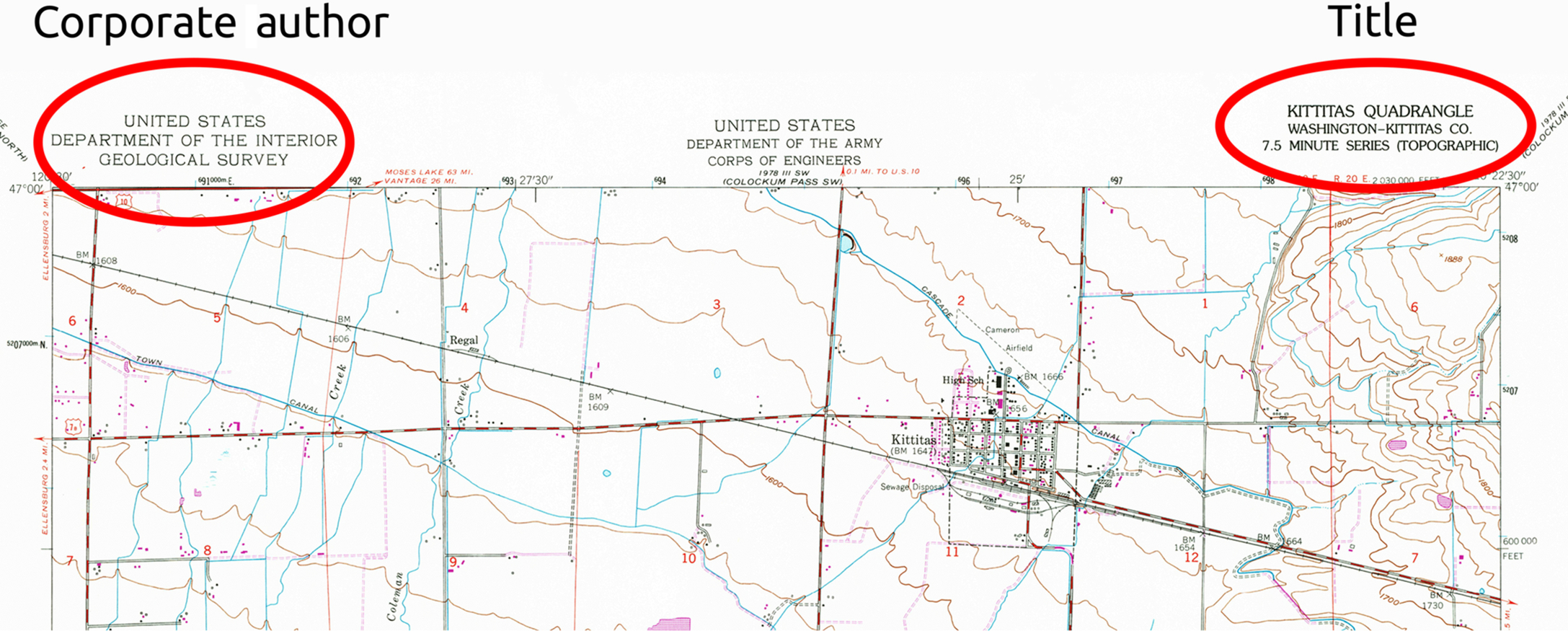

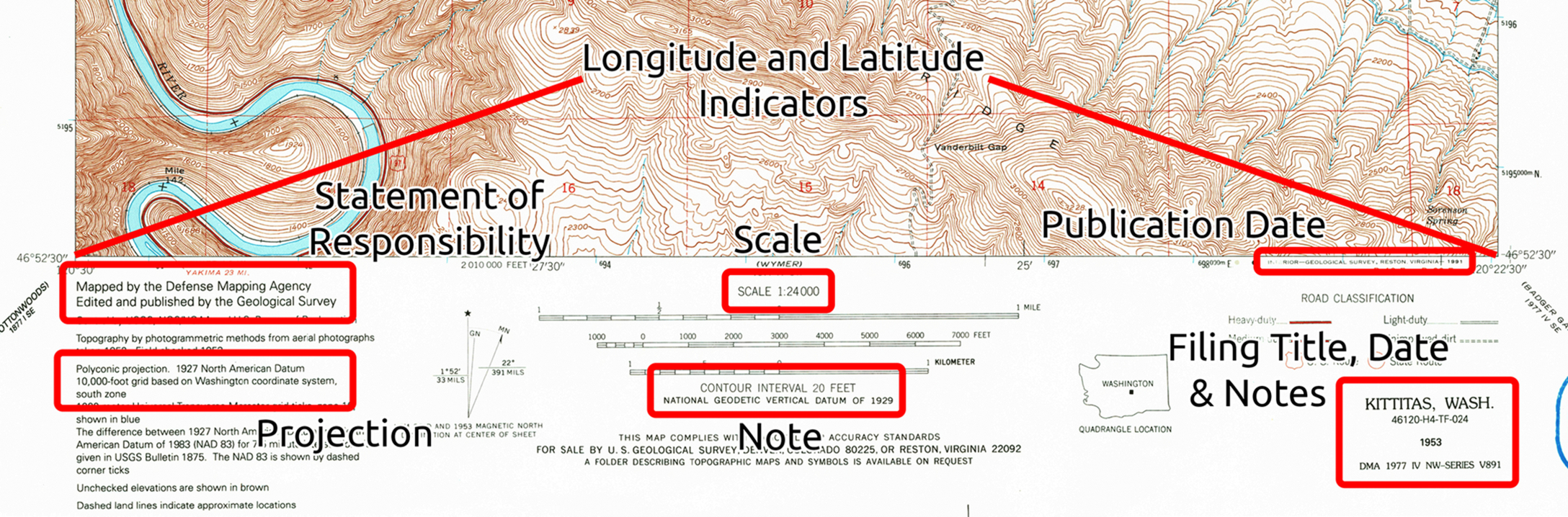

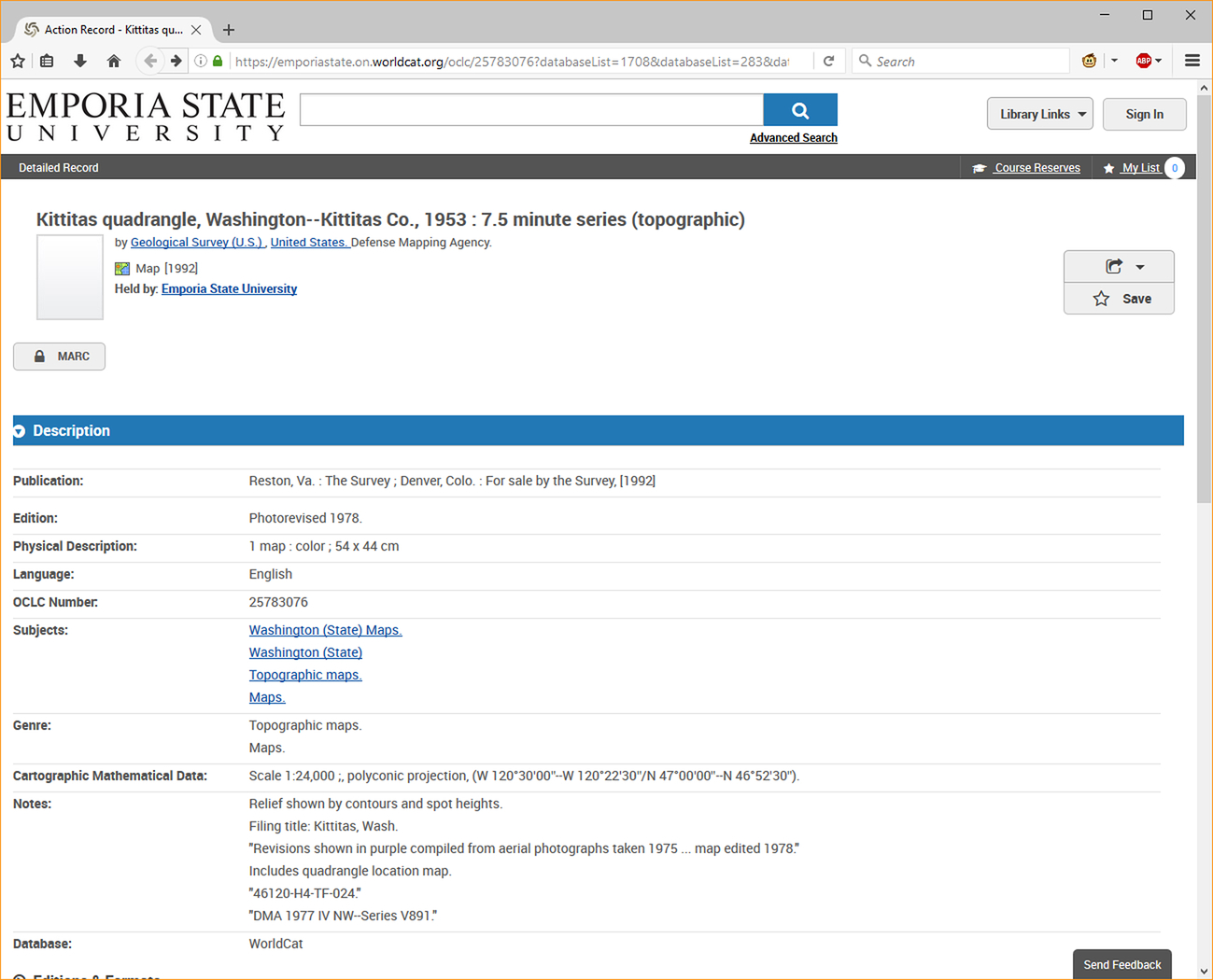

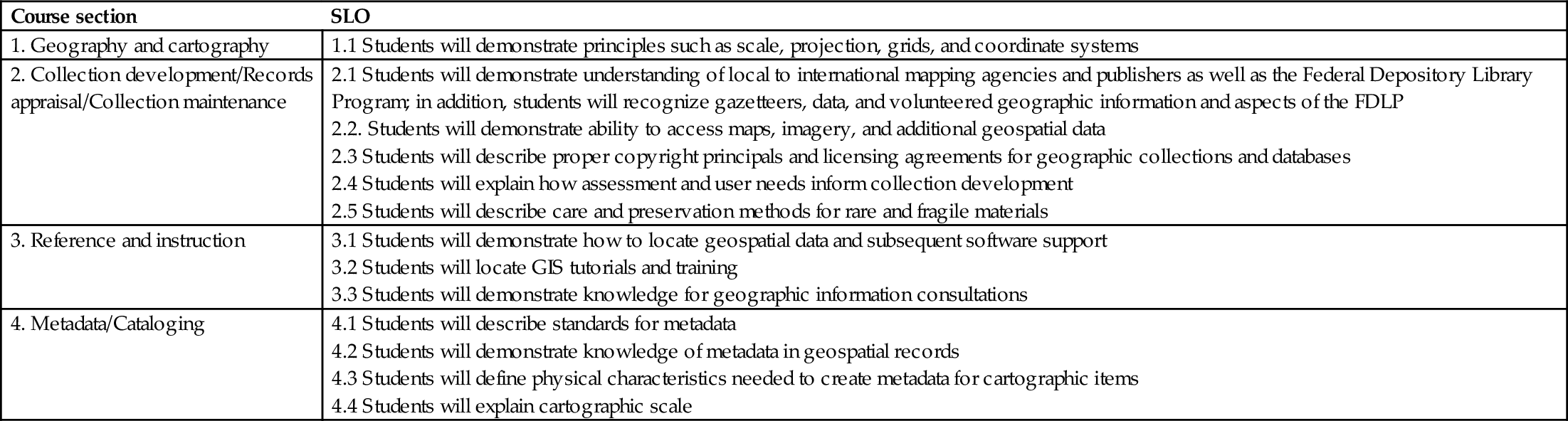

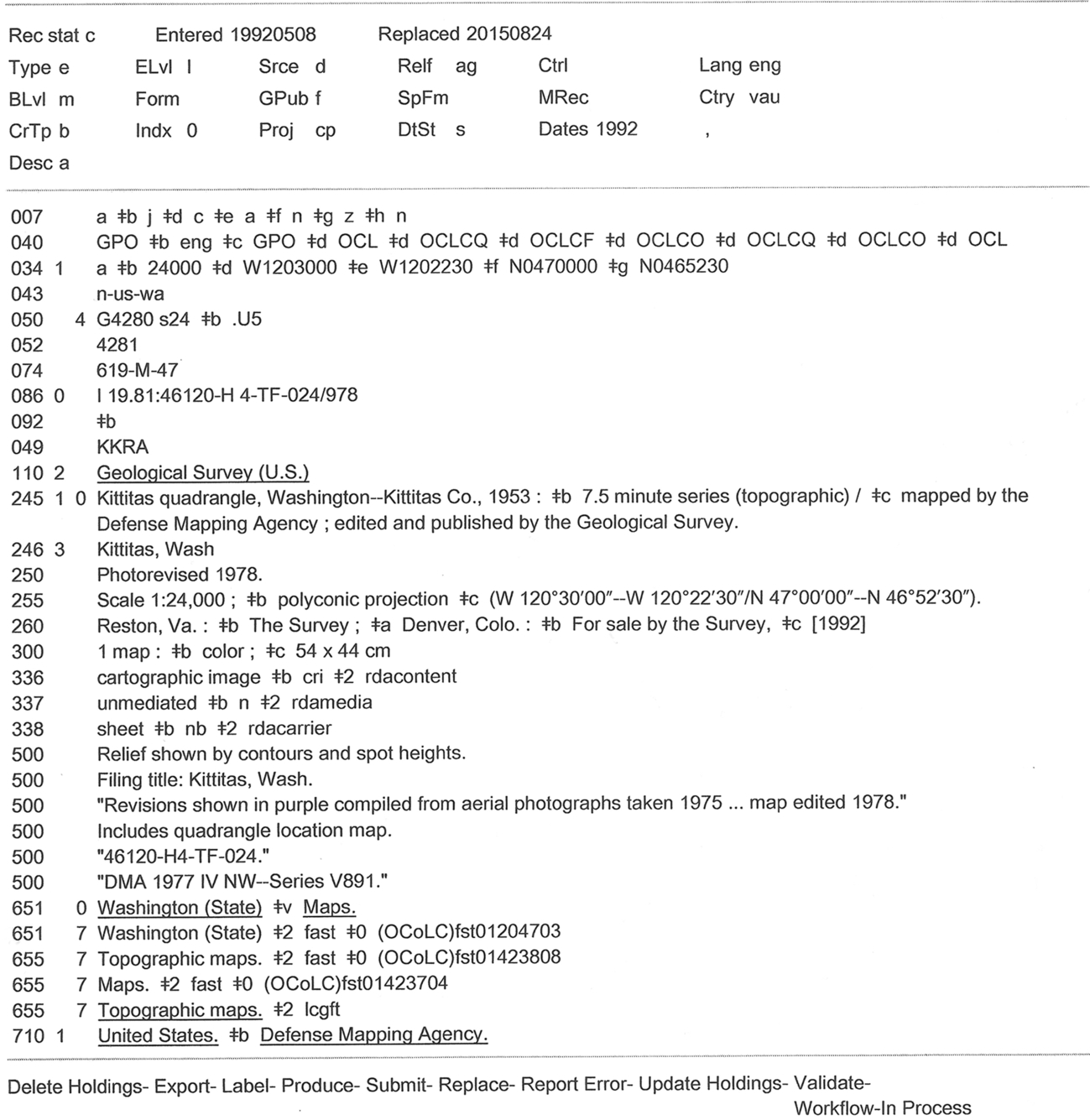

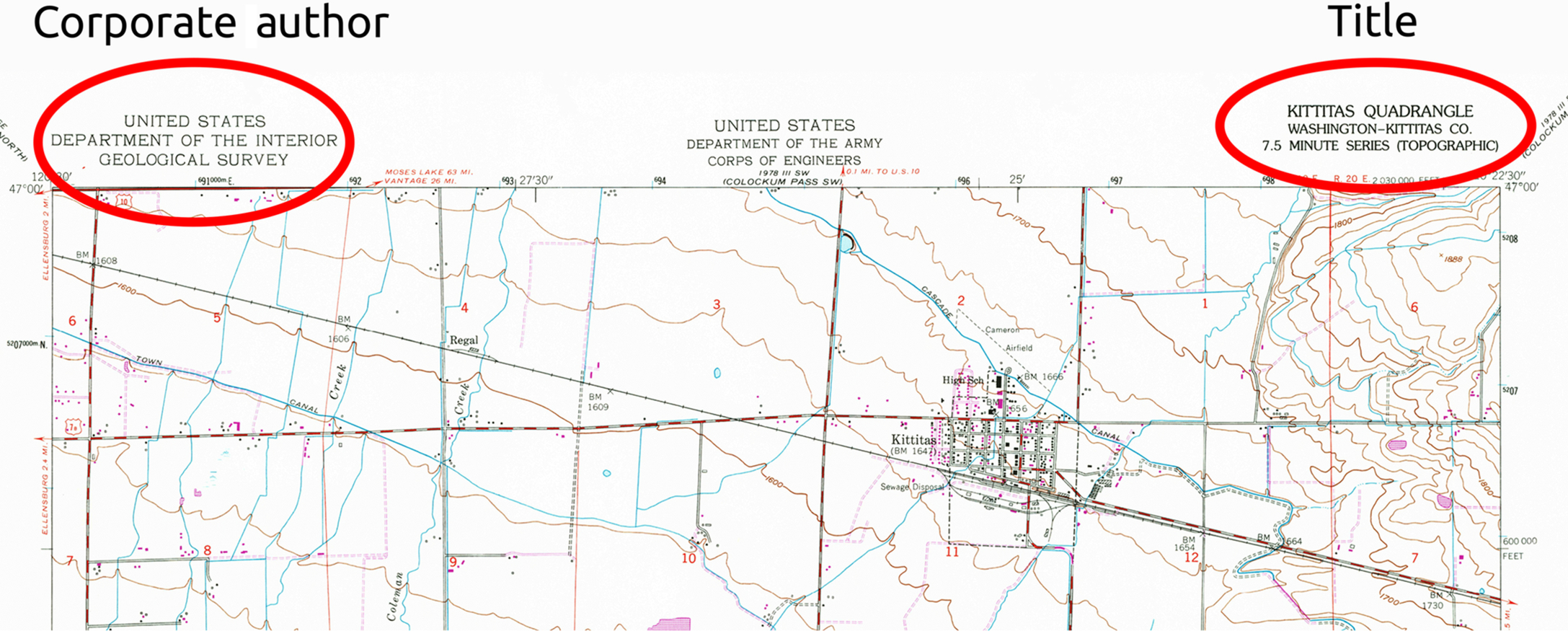

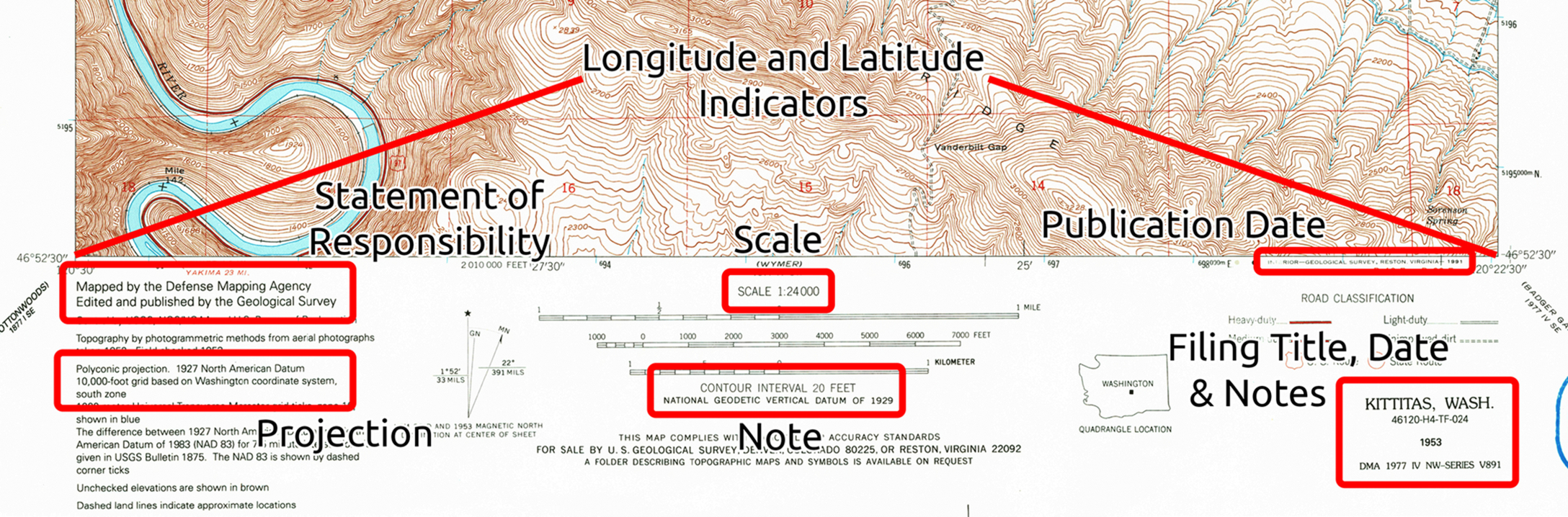

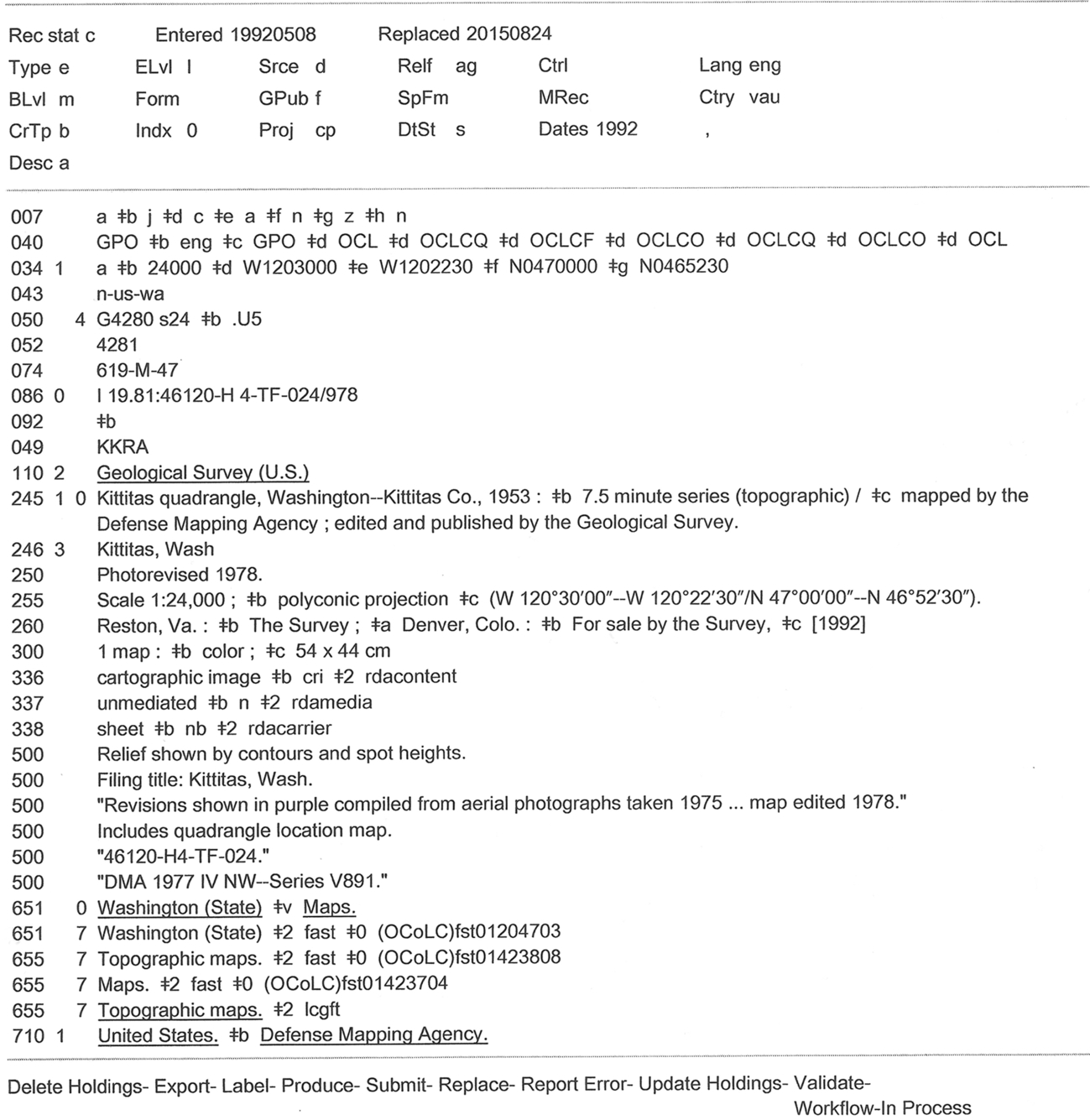

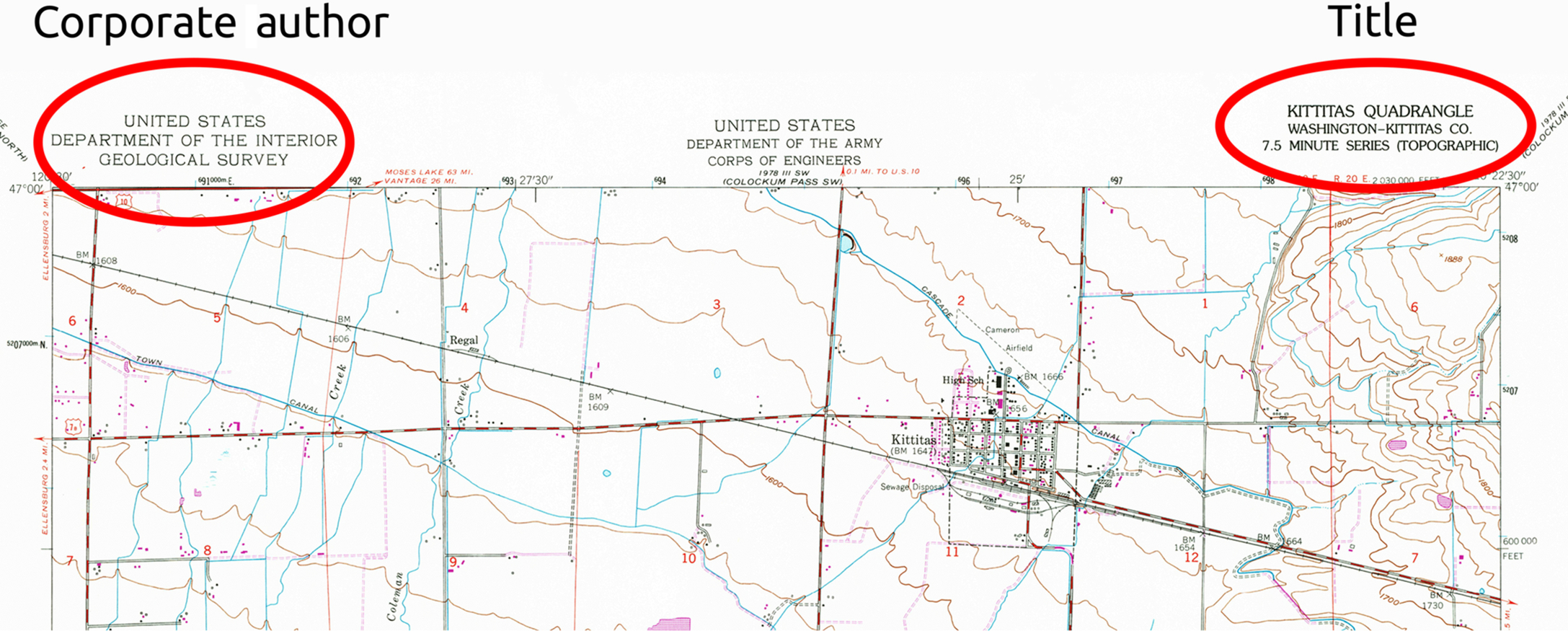

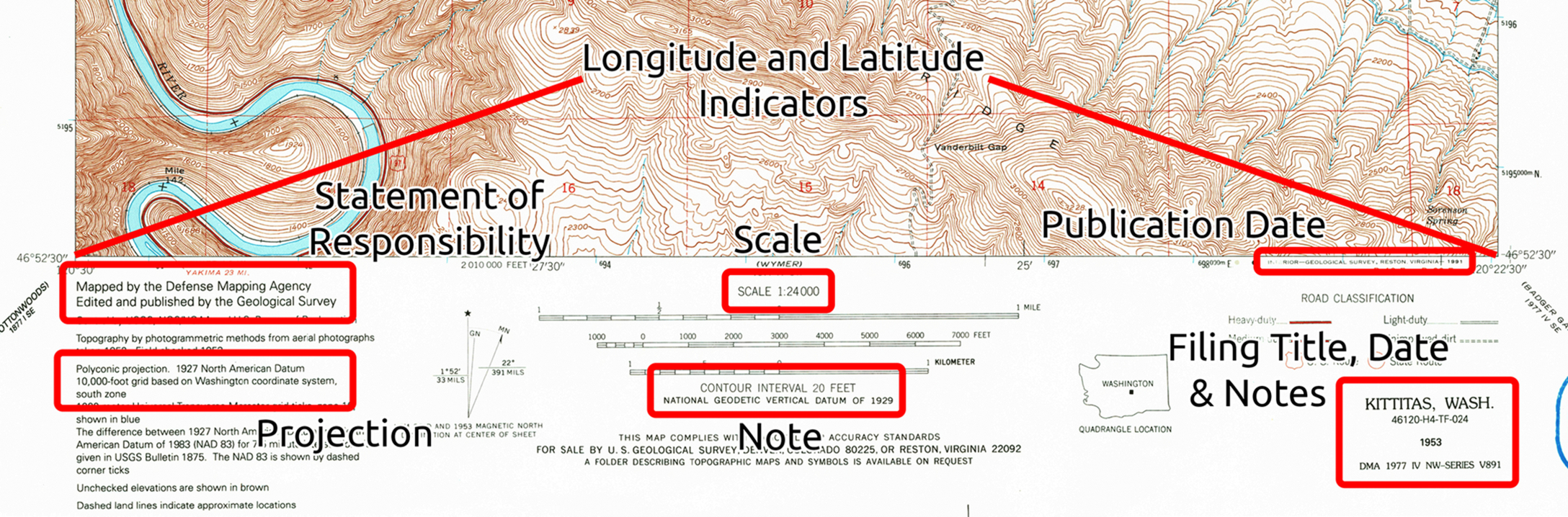

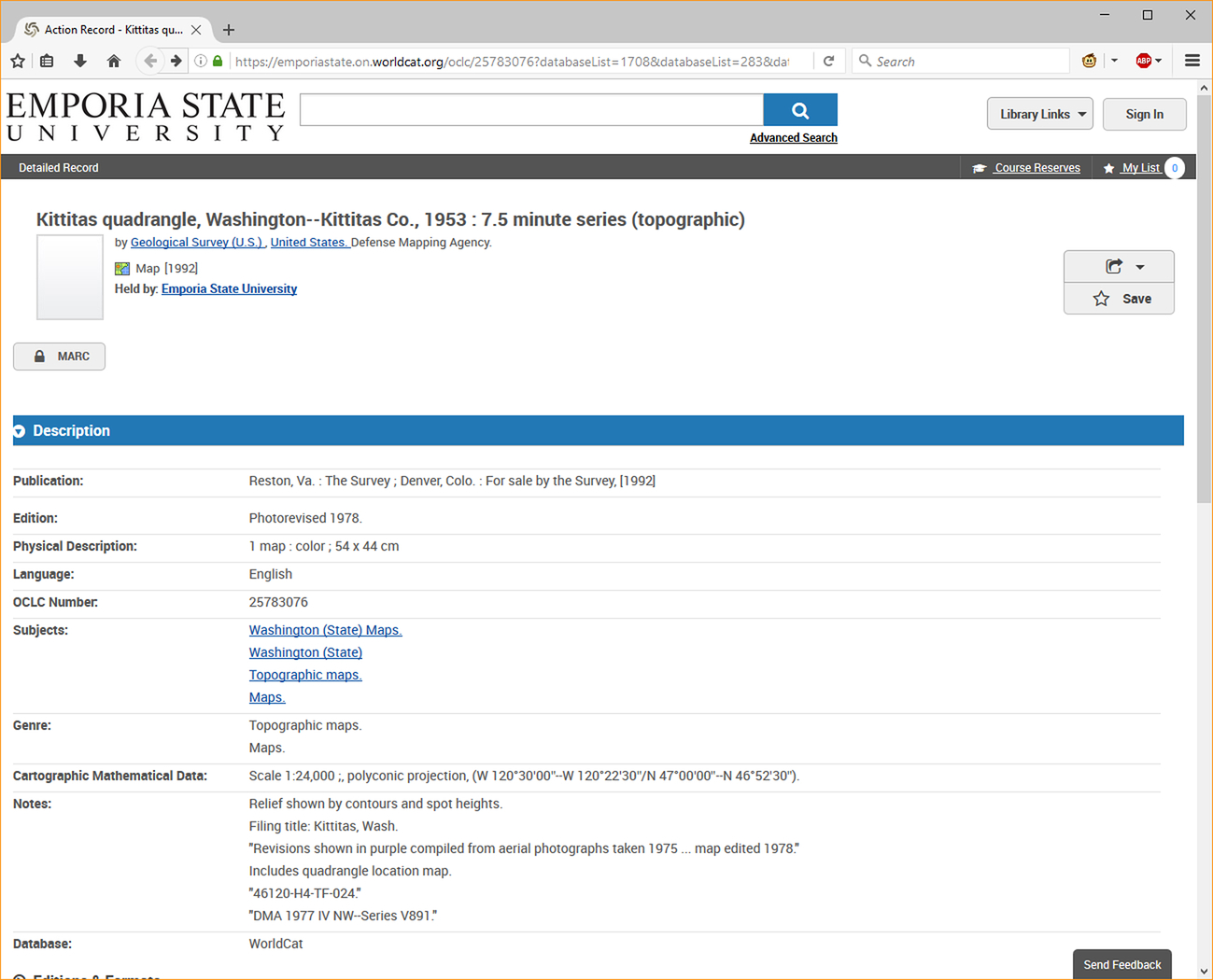

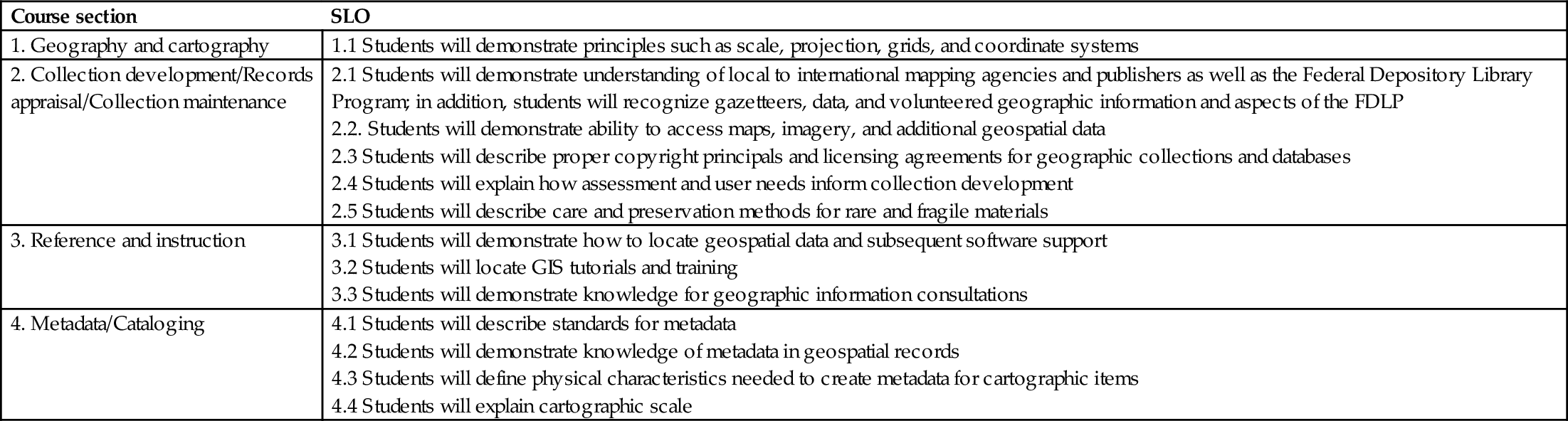

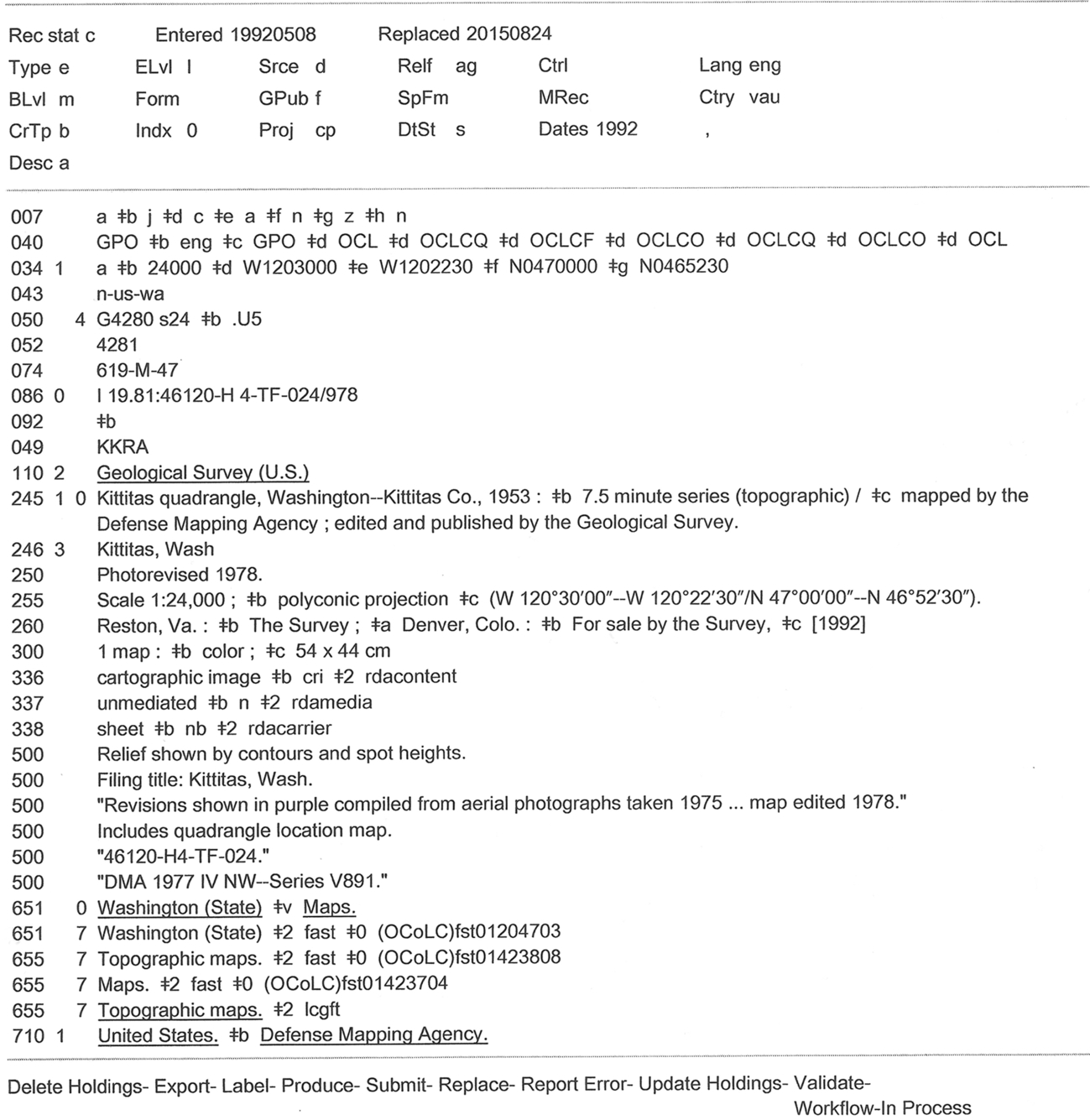

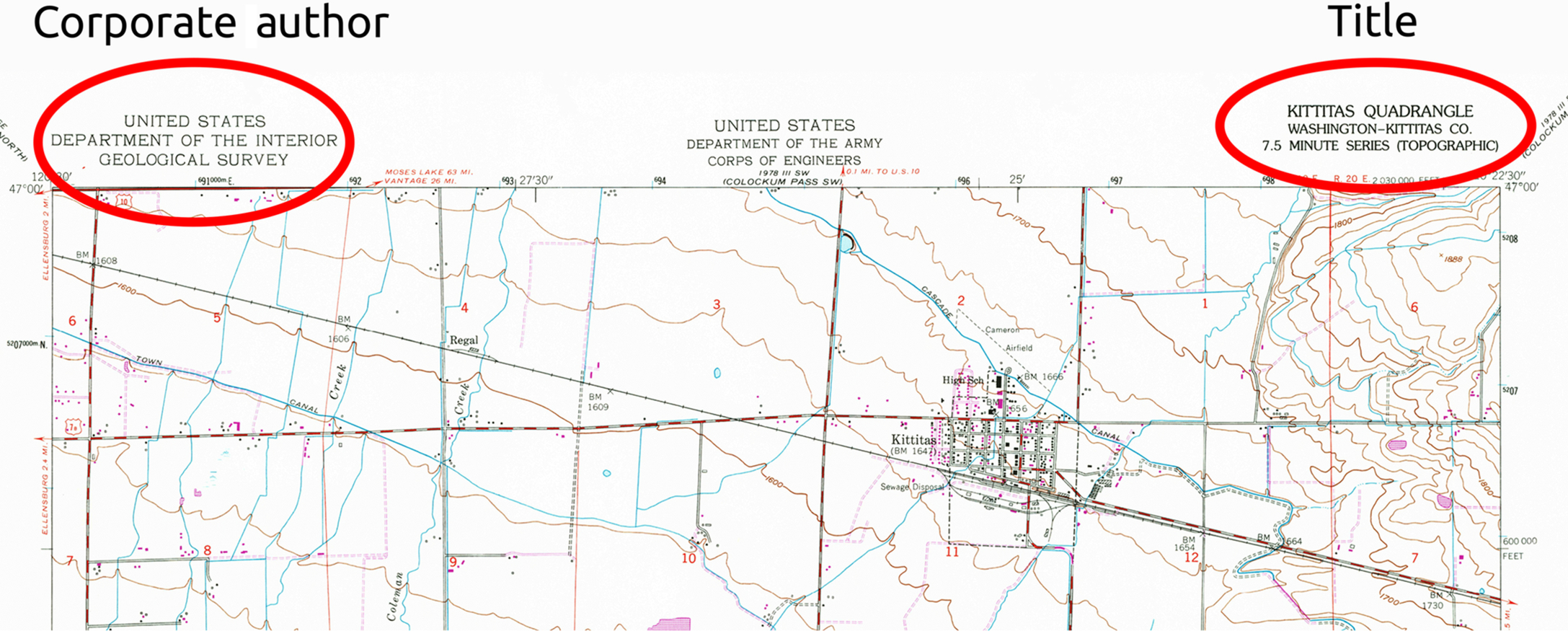

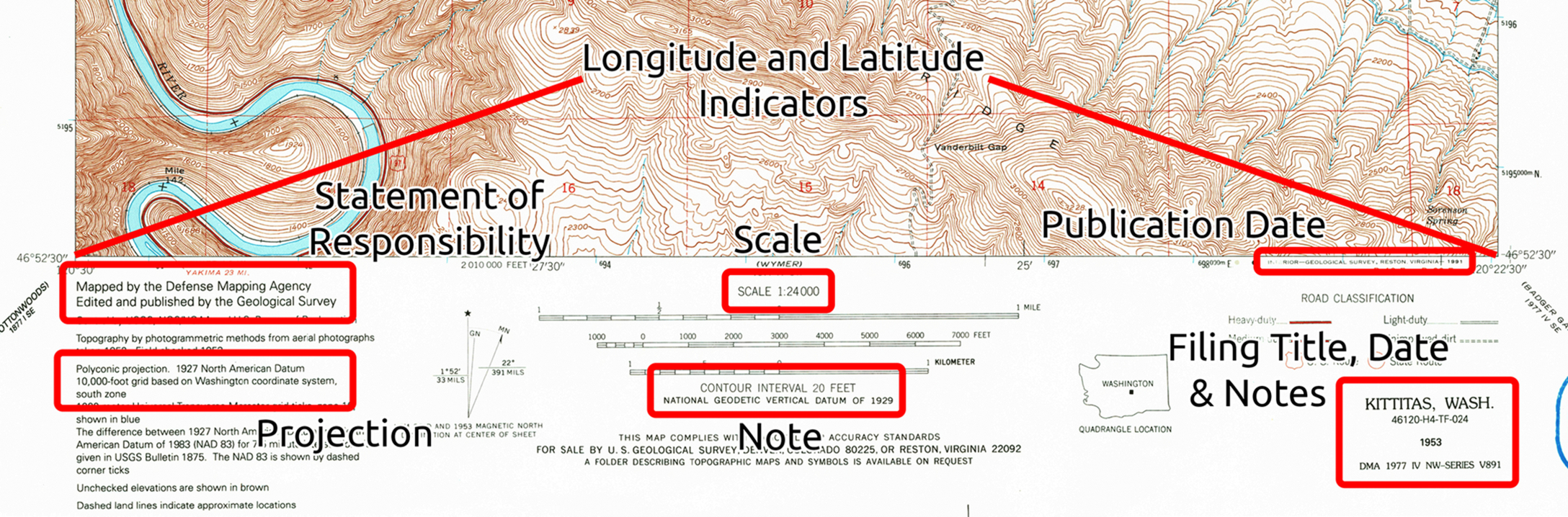

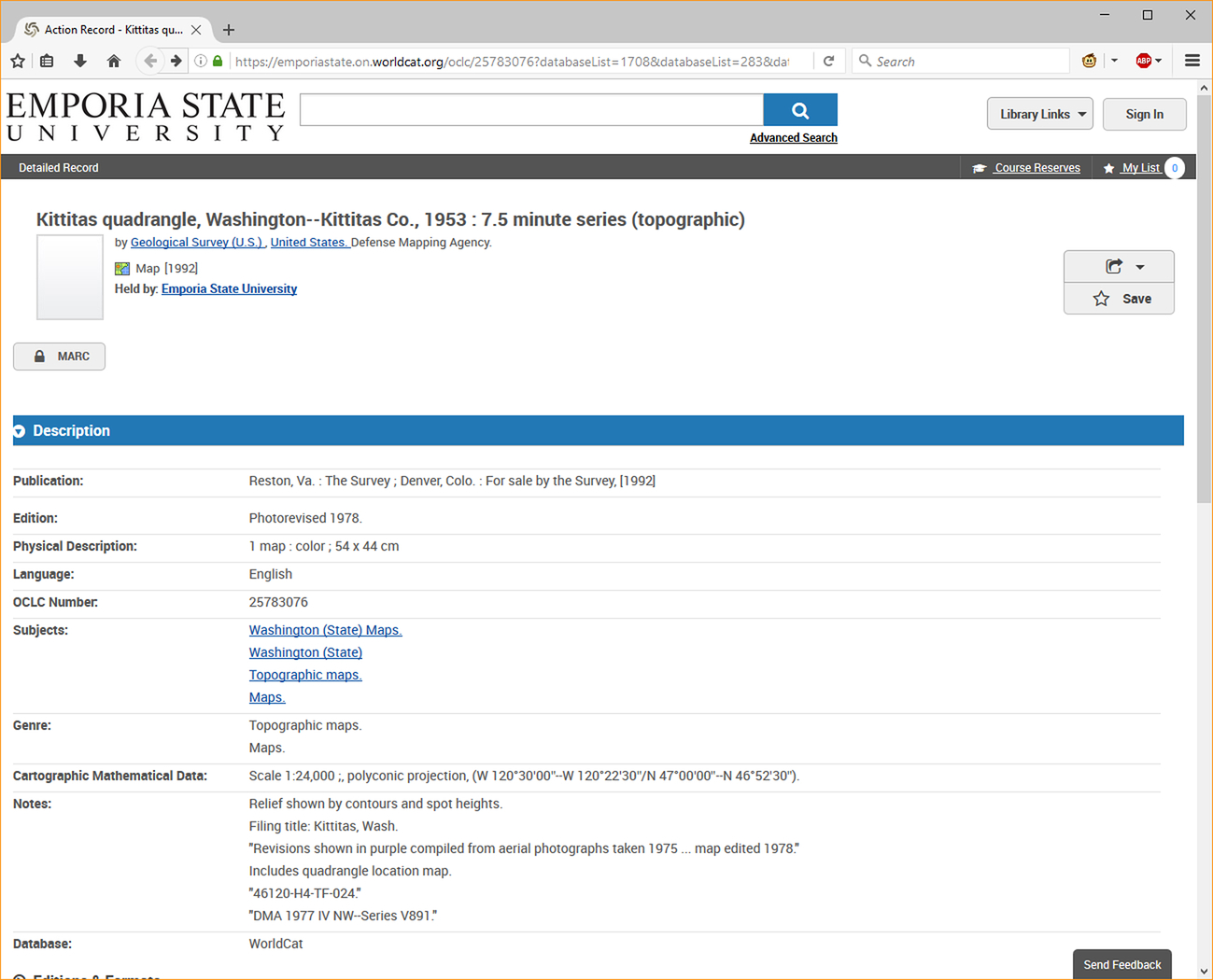

Chapter 10: Cataloging and Classifying

10.2 A Brief History of Cataloging Maps

10.3 A Brief History of Classifying Maps

10.4 Classification Systems and Maps

10.5 Cataloging Cartographic Resources

Chapter 11: Promotion and Summary of Map and GIS Resources and Services

11.2 Promotion of Library Resources

11.3 Geography Awareness Week, GIS Day, and Earth Science Week

University of Illinois Library School 1951

LS 306 Readings: Introduction to Maps and Map Libraries

LS 306 Readings: Cartobibliographic Aids

LS 306 Readings: Physical Care, Classifying, Cataloging, and Rare Maps

Chandos Publishing is an imprint of Elsevier

50 Hampshire Street, 5th Floor, Cambridge, MA 02139, United States

The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, OX5 1GB, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2017 Susan Elizabeth Ward Aber and Jeremy Ward Aber, Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions.

This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-08-100021-2 (print)

ISBN: 978-0-08-100045-8 (online)

For information on all Chandos publications visit our website at https://www.elsevier.com/

Publisher: Glyn Jones

Acquisition Editor: Glyn Jones

Editorial Project Manager: Lindsay Lawrence

Production Project Manager: Omer Mukthar

Cover Designer: Victoria Pearson

Typeset by SPi Global, India

James S. Aber, a caring husband/father. He is the one who started us on the journey of using, collecting, and creating maps as we traveled the U.S. and beyond. Throughout the process of writing this book, we had the opportunity to learn from him and benefit greatly from his expert editorial guidance and steadfast encouragement.

Amy A. Harris-Aber, a loving wife/daughter-in-law. She was always there with constant support, help, and advice, and put up with the long hours of writing and editing.

Jay T., a one-of-a-kind son/brother, Lauren R. and Rose E. Aber, completing this amazing family. The travelers who keep us busy simply finding all the wonderful places they visit and explore by foot, bicycle, car, train, boat, and plane.

R. Kenneth Aber, the best father-in-law/granddad in the world. For continually orienting and inspiring us to travel both physically and intellectually.

In memory of parents/grandparents, Marian M. and Henry A. Ward, and Sarajane S. Aber. You gave us unconditional support, artistic direction, and so much more.

Finally, we hereby dedicate this book to all of the past and present map librarians, who perform their jobs quietly with efficiency and care, fighting to retain and catalog the map and geospatial data collections, which are often relegated to basements or outsourced beyond imagination.

This book was inspired by teaching an elective reference resources and services course focused on maps and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) offered in a large university library and information science (LIS) program. The syllabus stated that no prior knowledge of geography and geoscience or maps and GIS was needed or assumed. Furthermore, all students were welcomed whether they navigated the world with landmarks or maps, geography-bee winners or not. Through informal observations about one-fourth of all students had some geography course work or degree; of those degree holders, approximately half of the geography majors stated they never had a geography course that was specific to maps. This surprised us, yet we know geography programs in universities may be aligned with geoscience or social science departments.

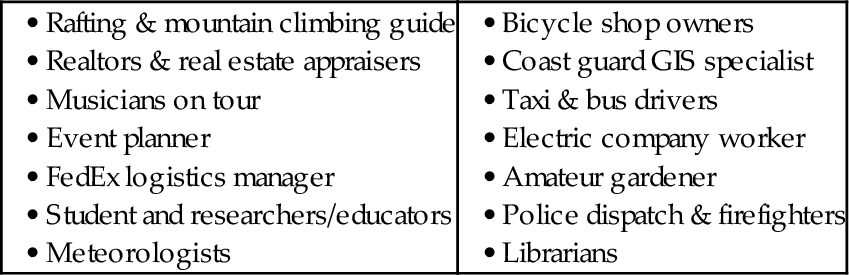

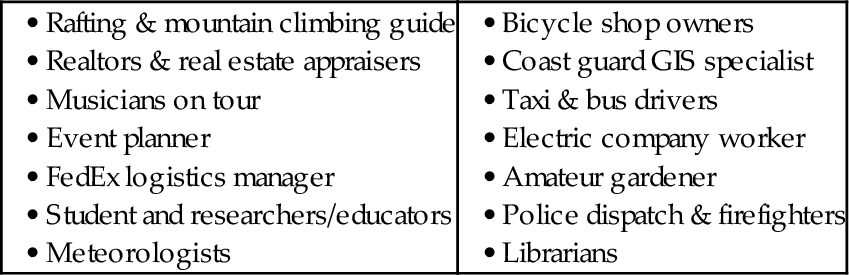

Students were sent into the field to meet map/GIS users and librarians. The first assignment asked students to engage in a 5- to 10-minute informal conversation and get to know some people who used maps in personal or profession life. Participants described occupational duties and named the map and data resources used to accomplish tasks as well as identified where the resources were acquired. The latter resulted in the second surprising observation, an overwhelming majority of participants were unaware that libraries had any cartographic resources or services and that these maps and data might be useful to them.

For the second assignment, some students found that librarians assigned to maps were sometimes reluctant to speak and repeated that they were not real map librarians. In contrast, other students found map and geospatial librarians who were knowledgeable, confident, and encouraging as well as ready to show off the collection and give valued advice to students on their career direction. Unfortunately, the exemplary map librarian was a bit harder to find and this was another surprise to both teacher and student.

This is why we identified the need for this book in addition to the fact that there was no single source that focused on geoliteracy and map librarianship. We designed the book to be a practical guide for students and librarians, who may want to build confidence and enhance their geoliteracy knowledge so as to apply it to traditional librarian skills. As map librarians, they have to not only promote resources and services to clients, but also to library colleagues and administration. Yet, we were asked why maps and why us?

Maps are everywhere. We carry them digitally in our phones and vehicle dashboards. We have them physically on the book shelf, and folded or bound slipped into glove box of the car. Maps have scale and compass direction, and as such they provide the best hiking and biking paths. They can also show the movement of hurricanes in order to detour and direct traffic during evacuations. Anyone navigating land, air, and water depends upon the most accurate and current maps and charts. Do you know how to maximize success through reading your map? Map librarians provide instructional services. Although navigation is primary, it is only one purpose for maps.

Reading and following a map could lead to adventures and problem solving. Old and new maps help in visualizing patterns and documenting change over time. Old maps show former channels in the river, which help archeologists today find buried treasure among sunken paddle boats. Medical researchers may map particular genes among generations of families or follow disease outbreaks tracking infestations of insects. Maps have assisted astronomers, attorneys, business owners, climatologists, collectors, criminologists, doctors, drivers, engineers, entrepreneurs, firefighters, genealogists, geoscientists, historians, librarians, pilots, pirates, police, politicians, soldiers, teachers, and writers, to name a few.

Maps are created to define the extent of solar system and galaxies, observe election results, or depict contours in an agricultural field. Maps identify flood-prone areas or demonstrate underserved regions where city services such as parks and public libraries are needed. Interpreting maps is contingent upon data defined in the legend and once reviewed may clarify solutions. It follows then that maps may be thought of as works of art or tools of the trade, which originally were the exclusive domain of cartographers and geographers. The shift from a physical to digital world of maps happened at the end of the 20th century and a geospatial revolution took hold early in the 21st century.

Yet, both maps and librarians seem to be in the middle of the print and digital worlds. We have followed the explosive use of maps and applications for GIS and mapping programs, which have grown phenomenally in the last two decades. Librarians are perfectly situated with valuable collections in place. The library could play a huge role in the geospatial revolution, but instead seems to be content to let this opportunity pass by. LIS programs briefly recognized their chance in the 1980s, but with little recruiting effort for science majors the programs seemed easy to cut from the budget. This misstep has resulted in map users bypassing the library and allowing Internet searching and mapping to become the norm. Libraries are valued institutions, but need to recognize that the geospatial revolution includes maps, data resources, and services in their libraries.

Our lives are intertwined with maps and depend upon geoliteracy, whether we are aware of it or not. Like the fish that is ignorant of water or the bird the wind, people define boundaries, prove ownership, and navigate Earth using maps and depend on geoliteracy, whether by tacit knowledge or physical guidance of mapping programs. Maps scale to the size we need and vary in topic or subject to cover every imaginable situation. We have watched maps evolve as a combination of art and science over millennia.

Many people associate books and libraries. However, the global WorldCat library catalog added new information records for nearly 5 million unique maps held in libraries in 2015 alone. Libraries are more than a repository of books. In addition to adding maps into the collection, map librarians care and preserve for these physical and digital resources. One of the first cartographers to create a map of the world in the 3rd century AD was also one of the earliest map librarians at the great Library of Alexandria. Eratosthenes created maps and curated geographic information for future generations. Besides preserving maps, the Library of Congress now has about 17,000 maps available online from its collection of 5.5 million maps. Stanford University has been the recipient of major donations through digital philanthropy. There are 71,000 maps viewable online as well as 150,000 in donations overall.

The public's ignorance of map collections in libraries may come as no surprise, as not all map collections are included in library catalogs, essentially rendering maps invisible to electronic searching. In addition, map collections are physically hidden when outsourced to other buildings or stored in basements of main library building. Maps may be cared for by grumpy librarians who are quick to explain their position was inherited. This indifferent attitude toward a map collection is easily explained, as few library schools offer any course on maps and GIS resources and services. Finally, visual information presents another conundrum to librarians who are steeped in textual literacy; that is, the need for citing maps is misunderstood and the procedures for referencing maps, aerial imagery, and geospatial data are difficult to find among the numerous referencing styles. Hence, map collections remain as gems in the rough until user-driven demand for access and improved services prevail.

Jeremy is a geography/GIS teacher and researcher. Susie is a teacher and researcher with an insatiable curiosity and appreciation for maps and librarianship. We have a common bond and compass in that our entire family shares a passion for traveling to new and unfamiliar places, immersing in different cultures and peoples, for exploring landscapes and natural resources, and preserving a balance between natural and human constructions. We value maps and geospatial data and want to help turn map resources in libraries from problem children to treasured collections. We want to make a difference and give back to the professions showing geography students a new career direction and ensuring library students and librarians that a text resource exists. Our goal is to enhance geoliteracy as well as reference and instruction skills by providing details on finding, downloading, delivering, and assessing map, remotely sensed imagery, and other geospatial resources and services, primarily from trusted government sources.

The authors wish to thank many colleagues, librarians both map and generalists, and students, who over the years have contributed content, photographs, editorial help, and inspirational ideas in preparation and completion of this endeavor. Some of them are listed here: James Aber, Jay Aber, Amy Harris-Aber, Mary Larsgaard, Eva Dodsworth, Beth Hanschu, Zada Law, Wade Bishop, Cara Bertram, Julie Sweetkind-Singer, Cynthia Karpa McCarthy, Igor Drecki, Benjamin Jones, Joyce Monsees, Linda Koistinen, Kathleen Weessies, Pete Reehling, Patrice A. Day, Meagan Duever, Jennifer Ann Haegle, G. Salim Mohammed, Jon Jablonski, Angie Cope, Jennifer Davis, Katherine Weimer, Linda Main, Debbie Faires, Irene Owens, Chad Morgan, George Knott, Harriet Clayton, Julie Hallmark, Julie Williams, Linda Zellmer, Patrick McGlamery, Hallie Pritchett, Tassanee Chitcharoen, Suzanne Harter, Sandra Hirsh, Linda Lillard, Linda Musser, Paige Andrews, Marcy Bidney, Emily Prince, Susie Oh Quinn, Andrew Carlos, Jeffrey Franks, Trish Garcia, Mary Fran Griffin, and Earle McCartney.

Support was given during the writing of this book by the following institutions: Middle Tennessee State University (MTSU), North Carolina Central University (NCCU), San José State University (SJSU), and Emporia State University (ESU).

Maps serve to orient lives and navigate landscapes. The historic progression of map-making cultures and collectors may date back as far as 12 millennia. Map librarianship as a career track is a mid-20th century phenomenon. Librarians managing cartographic collections must be geo-literate and have adequate academic library school coursework to design effective map and geospatial services. 21st century cartographers and geographers have gained new importance in documenting natural disasters through the use of global social media channels, maps, and geographic information systems. For librarians to be essential liaisons they must assure maps and geospatial data are freely available. As NeoGeography and NeoCartography have become commonplace, it is time library school programs support NeoMap Librarianship and join the Geospatial Revolution.

Geography; NeoGeography; Cartographer; NeoCartography; Crisis mapping; Compass; Spatial; NeoMap Librarianship; Maps; Crowdsourcing; Participatory cartography; Geo-literacy; Geo-literate; Geospatial Revolution.

Maps are ubiquitous and can record a sense of place in life. Maps situate the reader to a location on Earth through cardinal points of a compass providing the direction in space. Stephen Hall (2004) assumed that we travel with maps “neatly folded and tucked away in the glove compartment of memory”; we orient ourselves back and forth between time and landscapes, emotion and geography, and it all happens in the span of a few moments (p. 15). In fact, three-dimensional compass cells have been identified in bats, used to perform complex flight without disorientation (Finkelstein et al., 2015, p. 159). Costandi (2014) summarized research that suggests all mammals, which likely include humans, have head-direction cells or an internal global positioning system used to create these mental maps of the environment. Aber (2012) found that with short exposures to a novel place, individuals can recall the spatial layout of an environment to some degree, with a few capable of creating an incredibly accurate mental map of the space. Consequently, maps play a role in the place in which we were raised and reside, serving as our internal spatial compass.

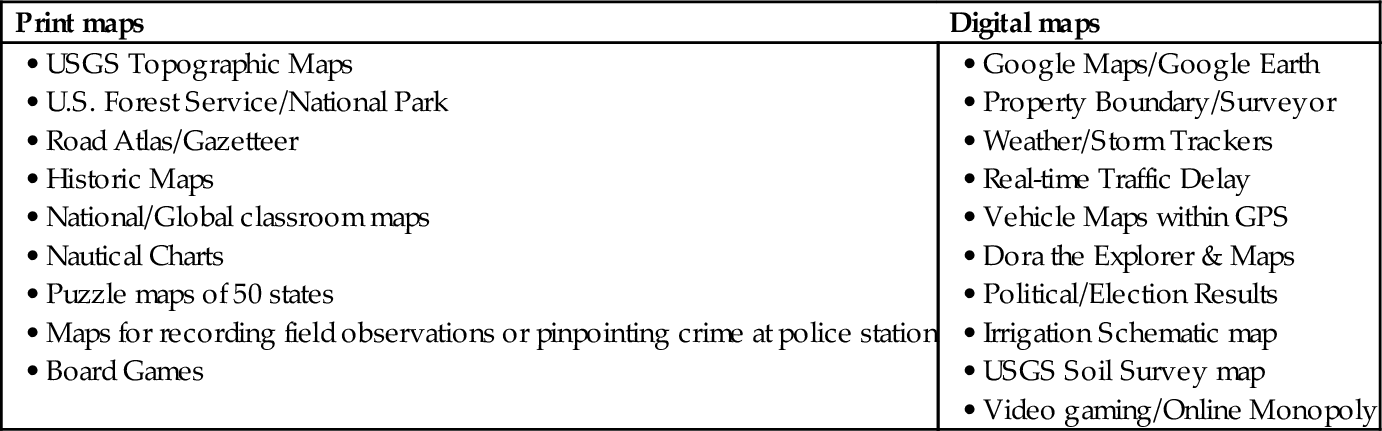

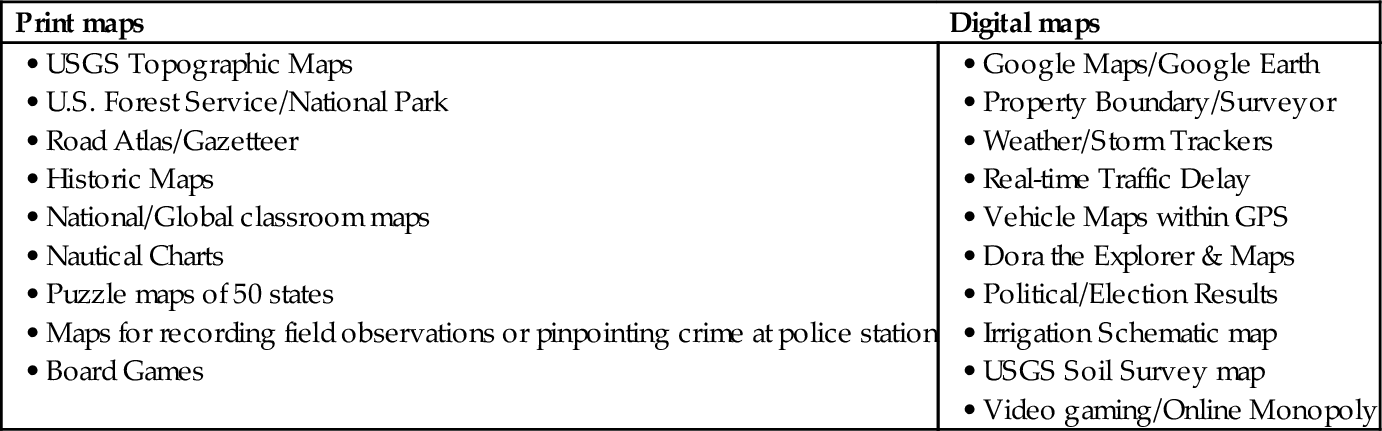

Maps are pervasive and people rely on numerous types of maps daily. Maps are produced in print or electronic formats, accessed in print books and single sheets or via mobile phone and computer devices. Planimetric or topographic maps may be used for navigation. Reading and interpreting maps help to create a route to travel from point A to B, whether driving unfamiliar roads or hiking over new trails. Likewise, interpreting digital data via electronic maps in real-time helps to anticipate traffic delays and predict changing weather conditions. Professional politicians might study past voting patterns on choropleth maps or cartograms while observing data on electronic maps showing present election results as polling stations report. Geologic maps are used to locate and interpret rock layers and tectonic structures when prospecting for valuable natural resources from coal to diamonds.

More recently, humans in the wake of natural disasters have benefited with quicker disaster response when participating volunteers come together to monitor social media channels and share information regarding infrastructure destruction and human-injury levels. These efforts result in maps, which provide emergency aid officials with valued current, yet ephemeral, information for a focused response. Subsequently, maps have become second nature. This is especially true when accessing and displaying mobile, electronic versions.

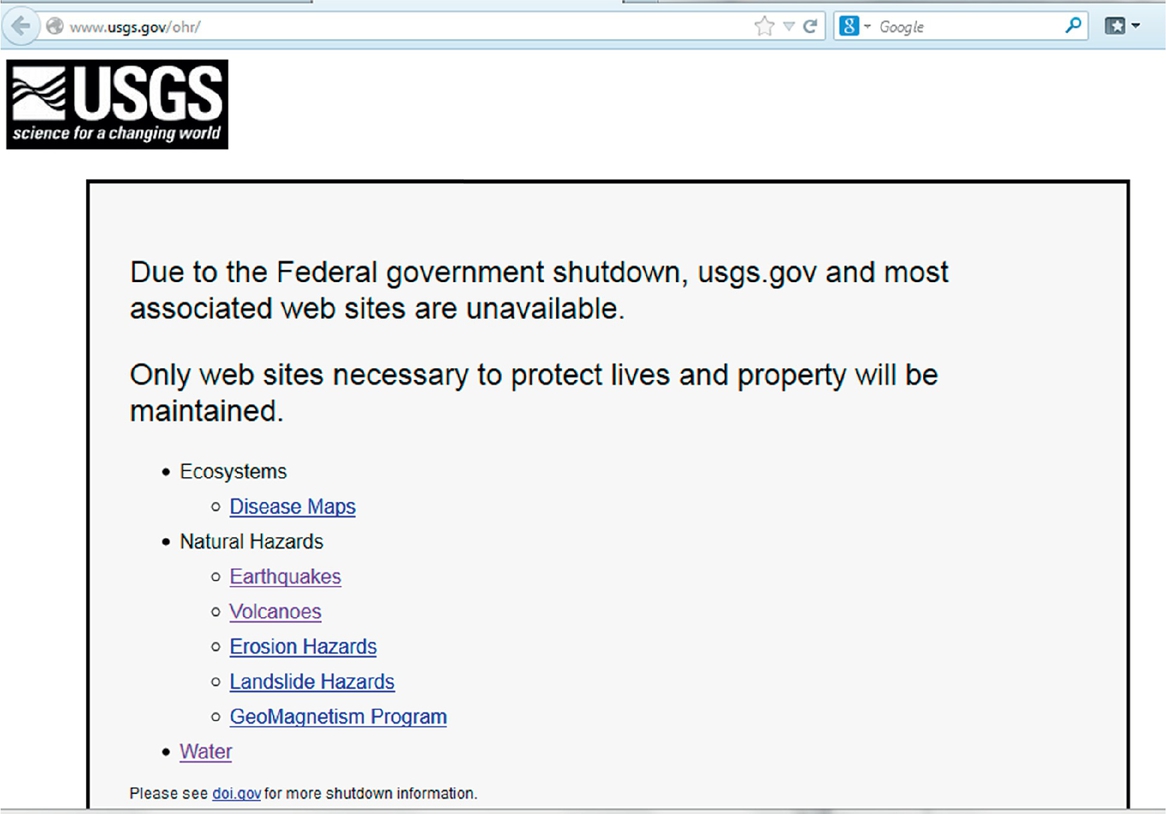

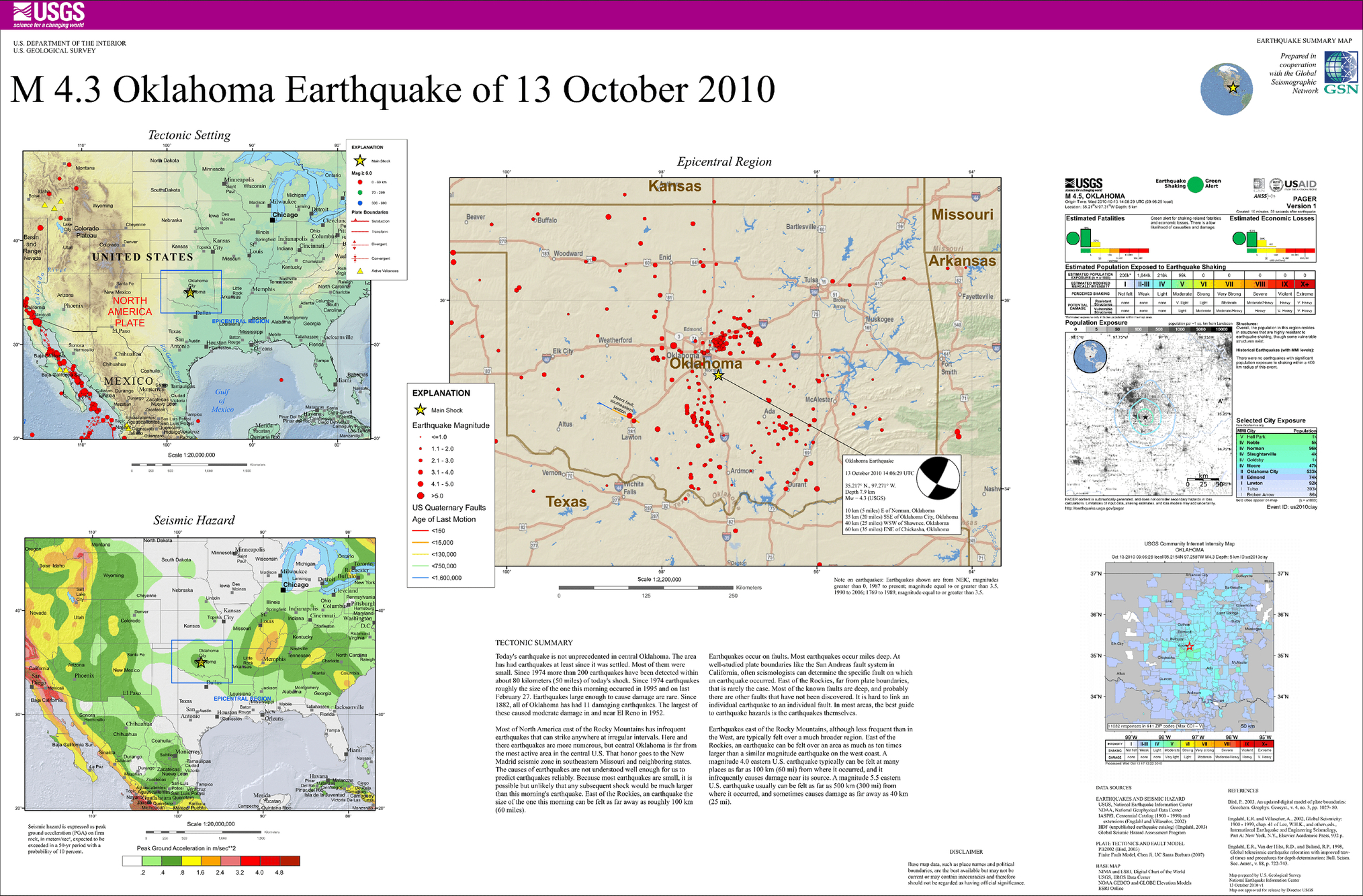

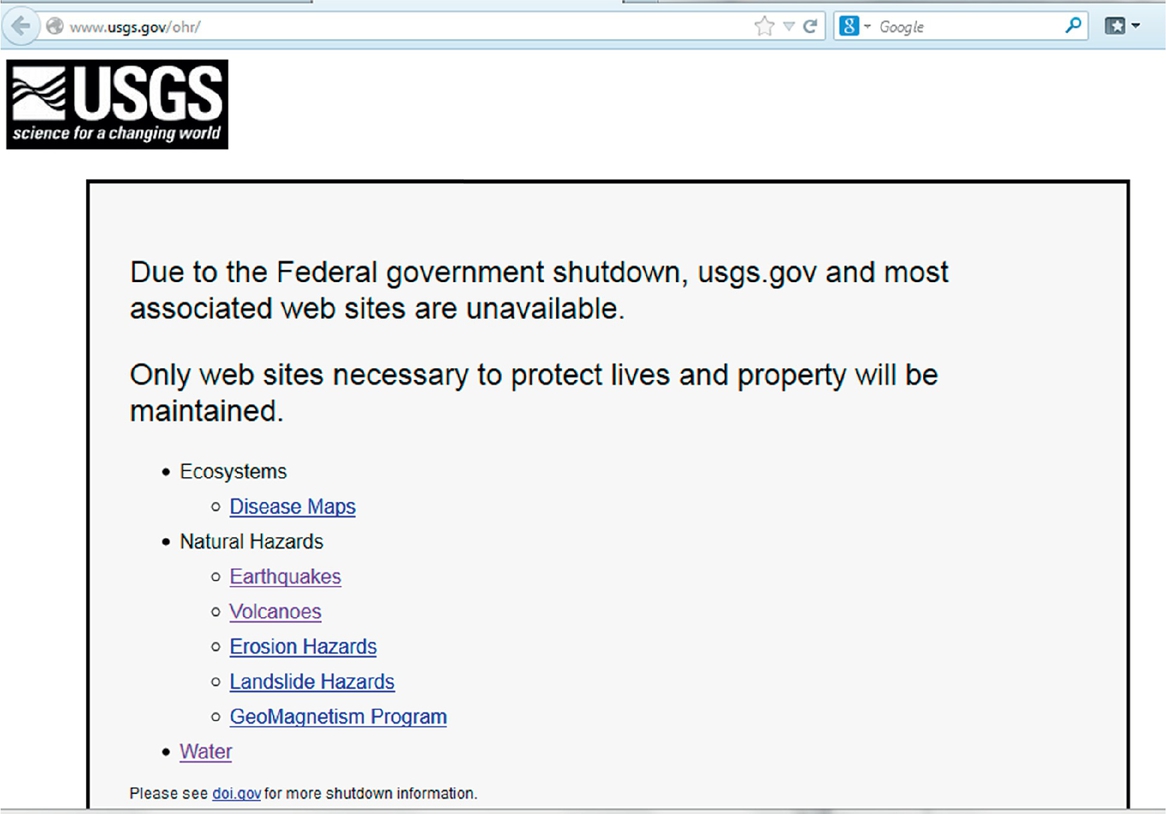

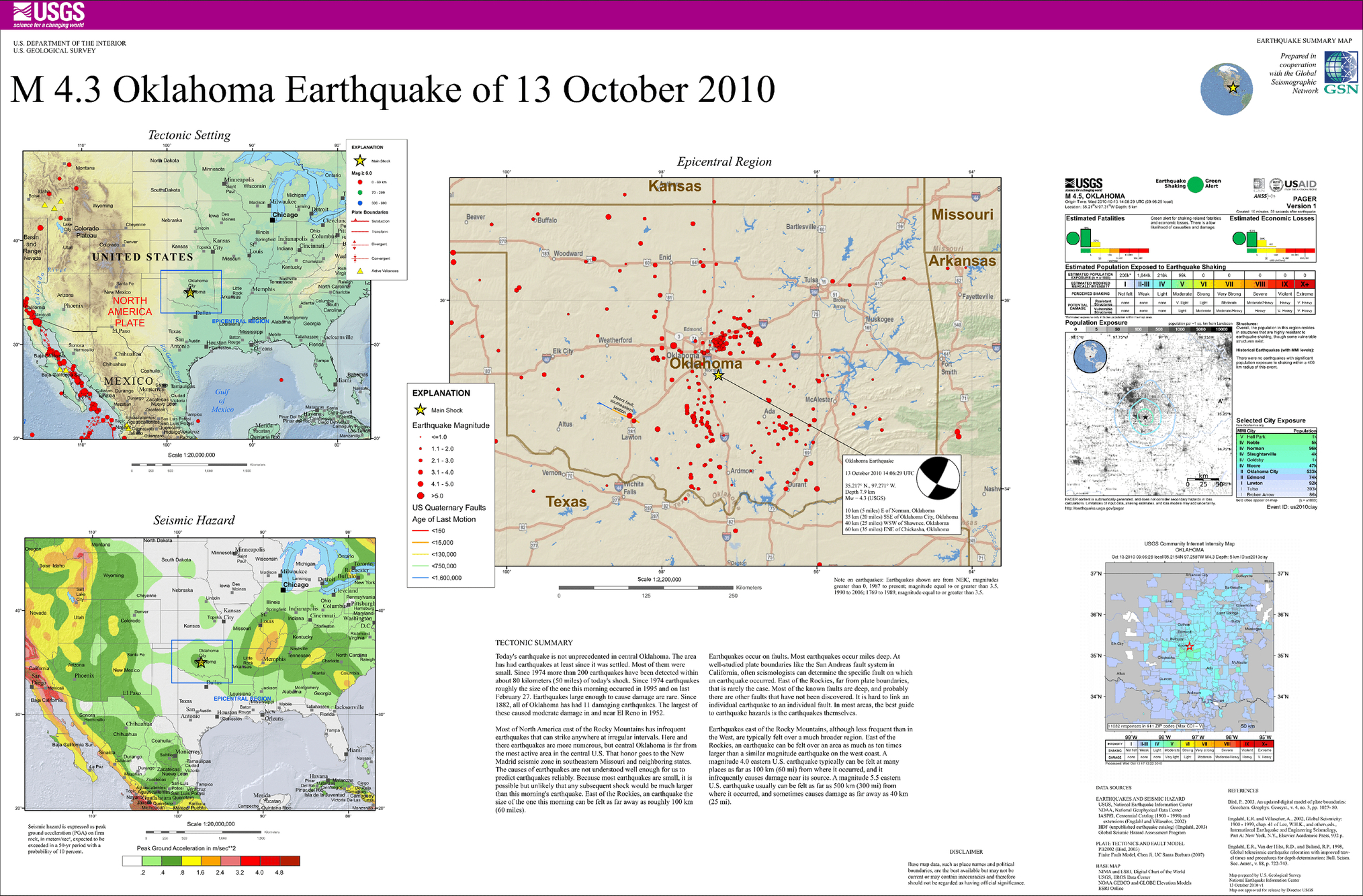

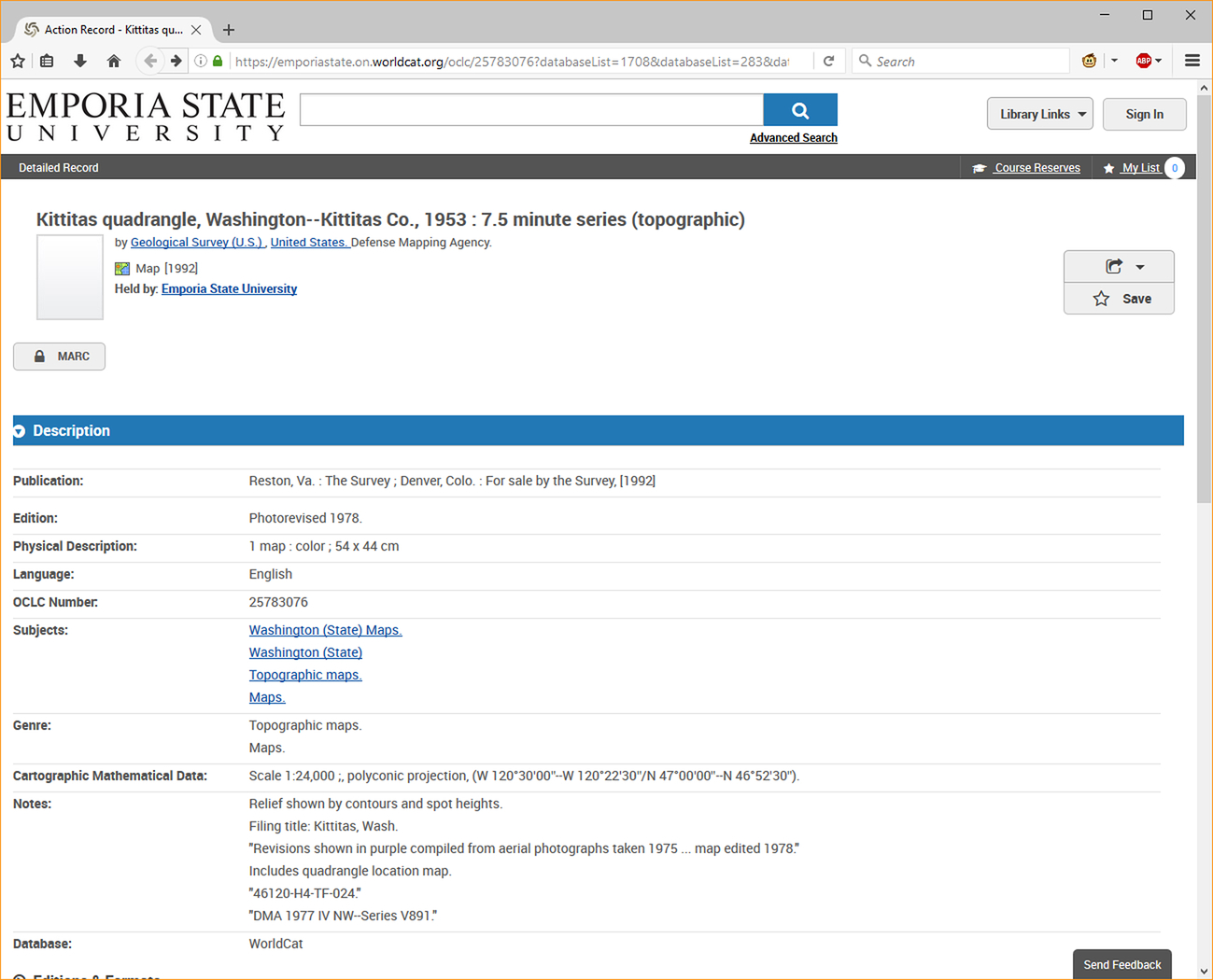

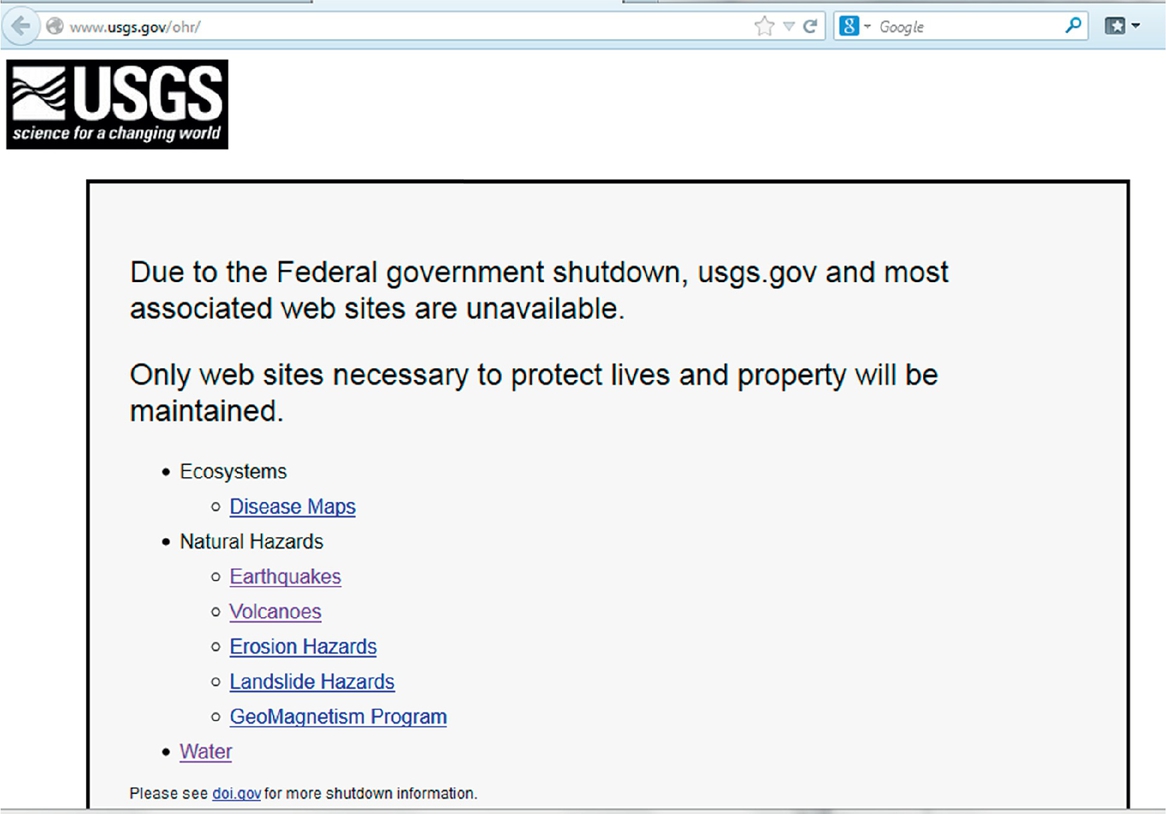

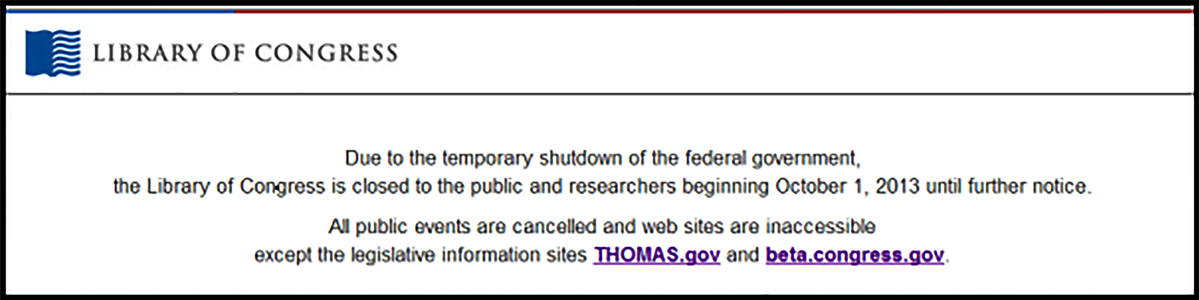

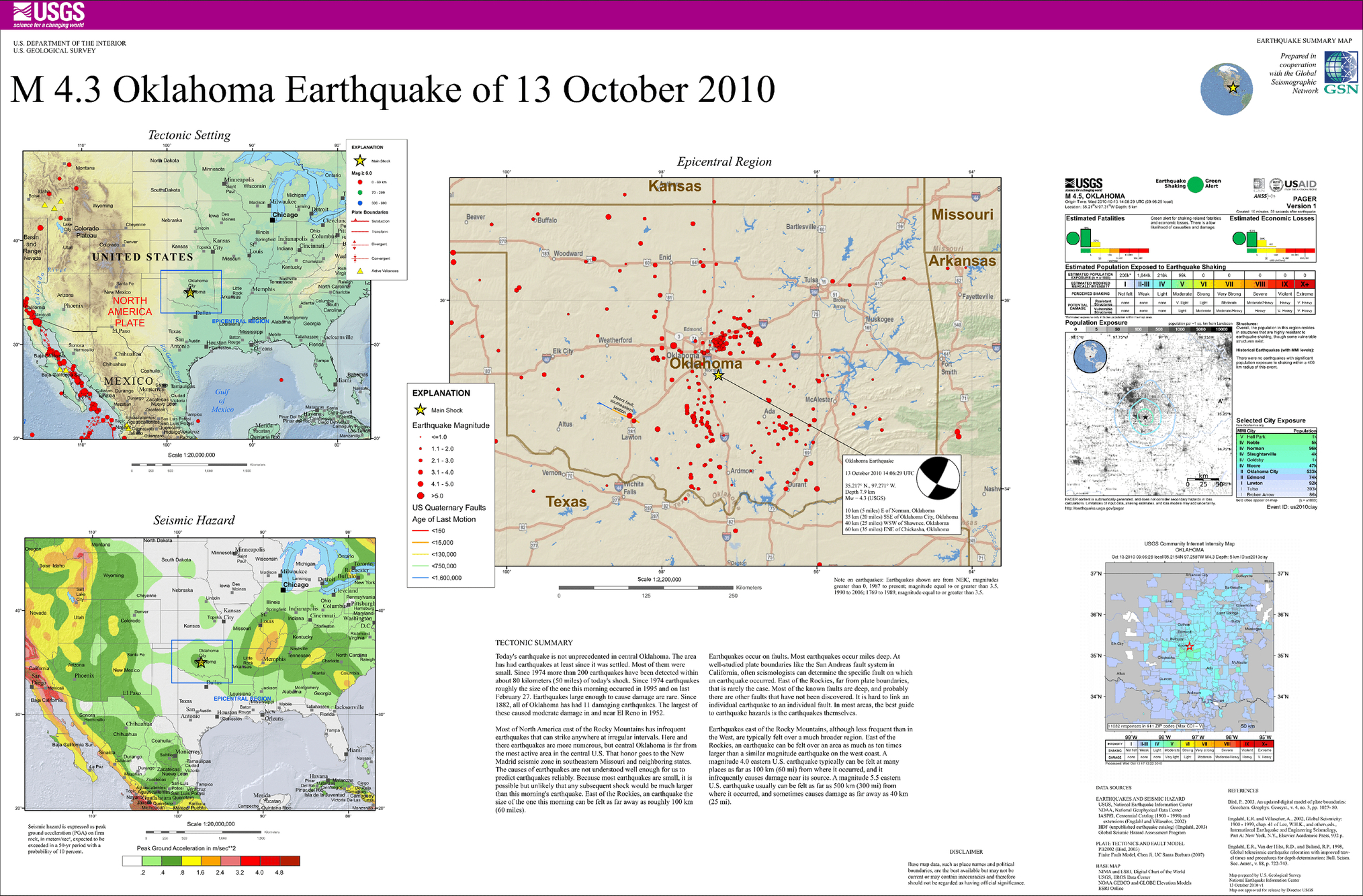

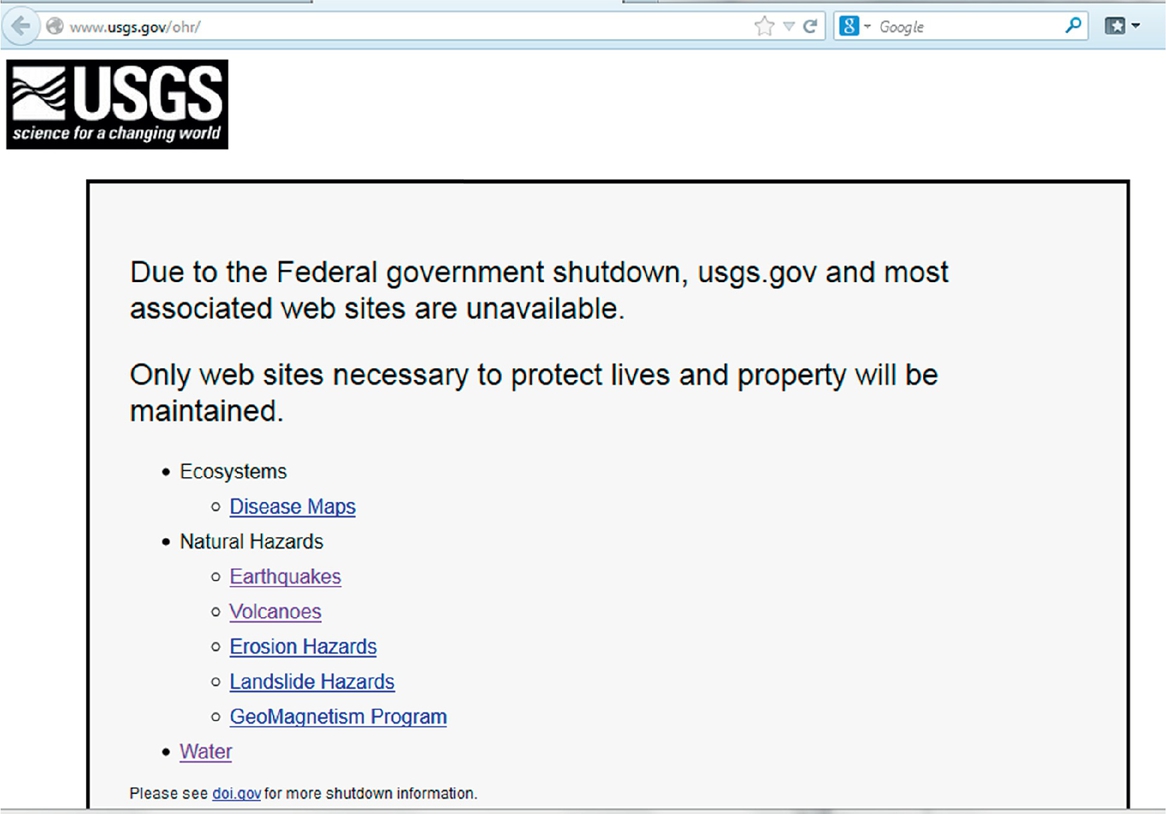

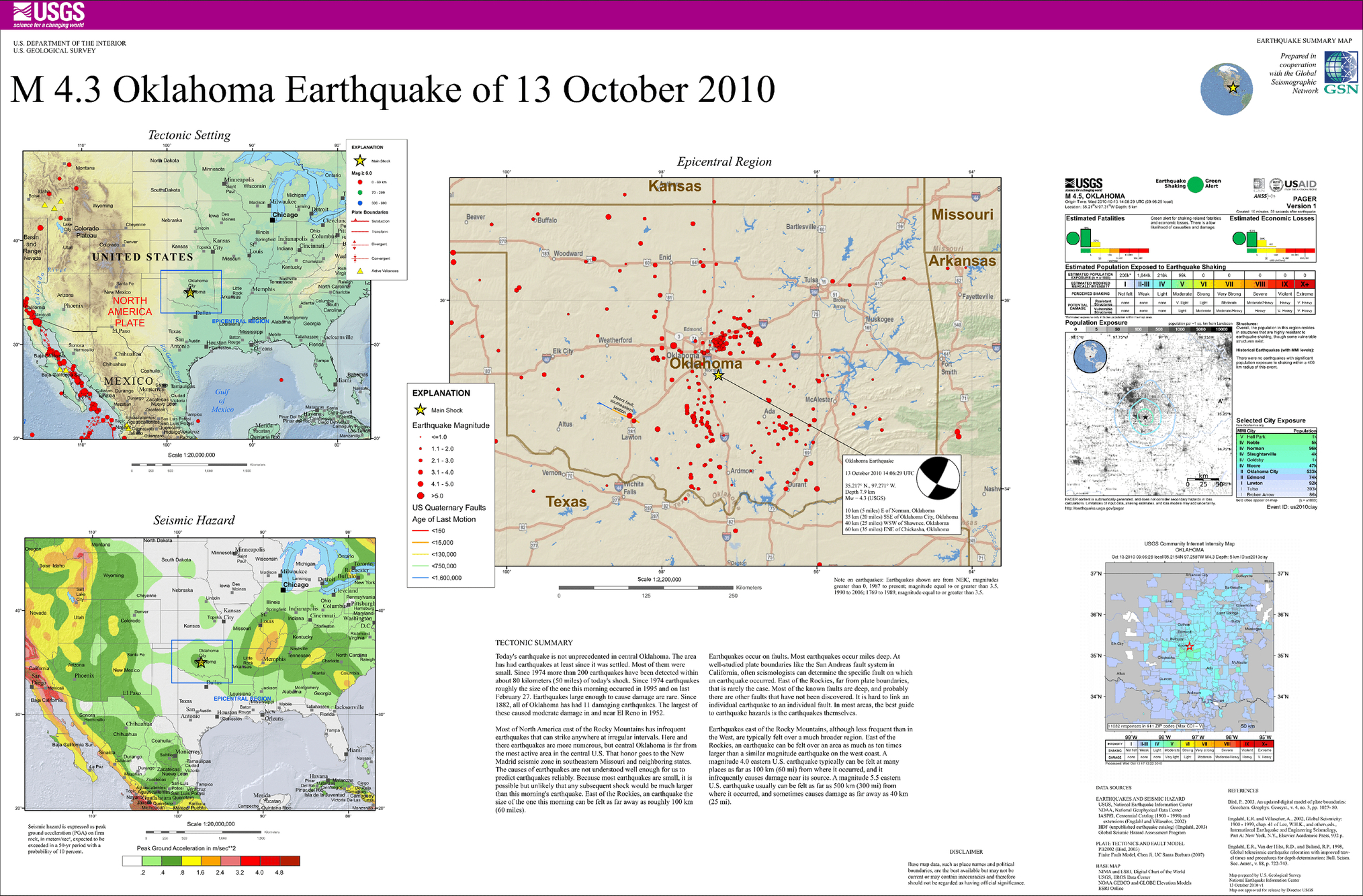

In Oct. 2013, American politicians disrupted our traditional spatial compass. The Legislature forced a Federal Government shutdown by refusing to pass a national budget for 16 days in order to stop implementation of legislation that created affordable health care insurance opportunities (The White House, Office of Management and Budget, 2013; Roberts, 2013). This political tactic cut off the world’s access to one of the primary sources for maps and geospatial data by closing nearly all of the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), and other federally funded science groups (Rosenberg, 2013). The only USGS web sites remaining online were those deemed necessary to protect lives including maps of disease, earthquakes, volcanoes, erosional hazards, landslide hazards, geomagnetism, and water, see Figure 1.1. Likewise, NOAA maintained some capability for weather forecasts and warnings, while NASA satellites currently in orbit were allowed to operate (Freedman, 2013).

These same legislators went even further and restricted access to information and data at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. However, in the nation’s capital, the mayor declared public libraries and librarians as essential, and the District of Columbia libraries defied the restrictions and remained open (Chant, 2013; DeBonis, 2013). In addition, some private companies, such as the Environmental Systems Research Institute (Esri), continued to provide access to existing federal government geospatial data resources through ArcGIS Online (Szukalski, 2013). Although our use of maps is so natural, the right to free access of maps, information, and data is in fact a privilege, which can be taken away.

Nevertheless, the value of mapping natural disasters by volunteers using social media has driven change in access and map making. In the past, printed or electronic maps were created using traditional geographic methods, where one map maker or professional cartographer created the finished map used by many. Now, maps may be produced with crowdsourced, shared data, and a new geographic method (Goodchild & Glennon, 2010). This participatory cartography, or NeoCartography, is where many come together to create one map.

These grassroots efforts and the need to bypass disruptions in the public’s access to maps and data have reinforced the value of libraries and the role librarians can play. Many libraries serve as Federal Depositories of print maps and may have created resource collections and services that included access to electronic maps and spatial data. However, not all librarians have map and geography educational backgrounds and may benefit by gaining a higher level of geo-literacy to be effective. If librarians have content knowledge, then they can adopt a collection development policy that promotes geography and cartography resources and creates effective instructional services.

Geography as a word has its origins in the Greek scholar Eratosthenes' writings (Roller, 2010). It combines "geo," meaning Earth and "graphy," which refers to art or science and the process or form of representing and describing, or in other words, writing about the Earth. While some assume that geography is a field concerned with memorizing political capitals, in reality it is a holistic approach to studying Earth and the people living there. Geography is considered to have four traditional areas of study: the spatial tradition, analyzing where things are; the area studies tradition, looking at what makes regions distinct; the earth science tradition, which covers many natural topics of geology, hydrology, atmospheric studies, etc.; and the man-land tradition, which looks at links between the natural and human-built environments (Pattison, 1990). This last tradition has become more and more important in recent decades as we increasingly come to understand the impact our actions have on the environment.

These four traditions together cover a great deal of human understanding of the world, which suits geography’s holistic approach to knowledge well. For example, a geographer would not look at the natural component of a mountain without considering how those elements are affected by those who live on the mountain; likewise, a geographic study of the people living on the mountain would be incomplete without considering the impact of the natural environment on their lives. These traditional geographic approaches are visible through the multitude of techniques and topics on display in maps.

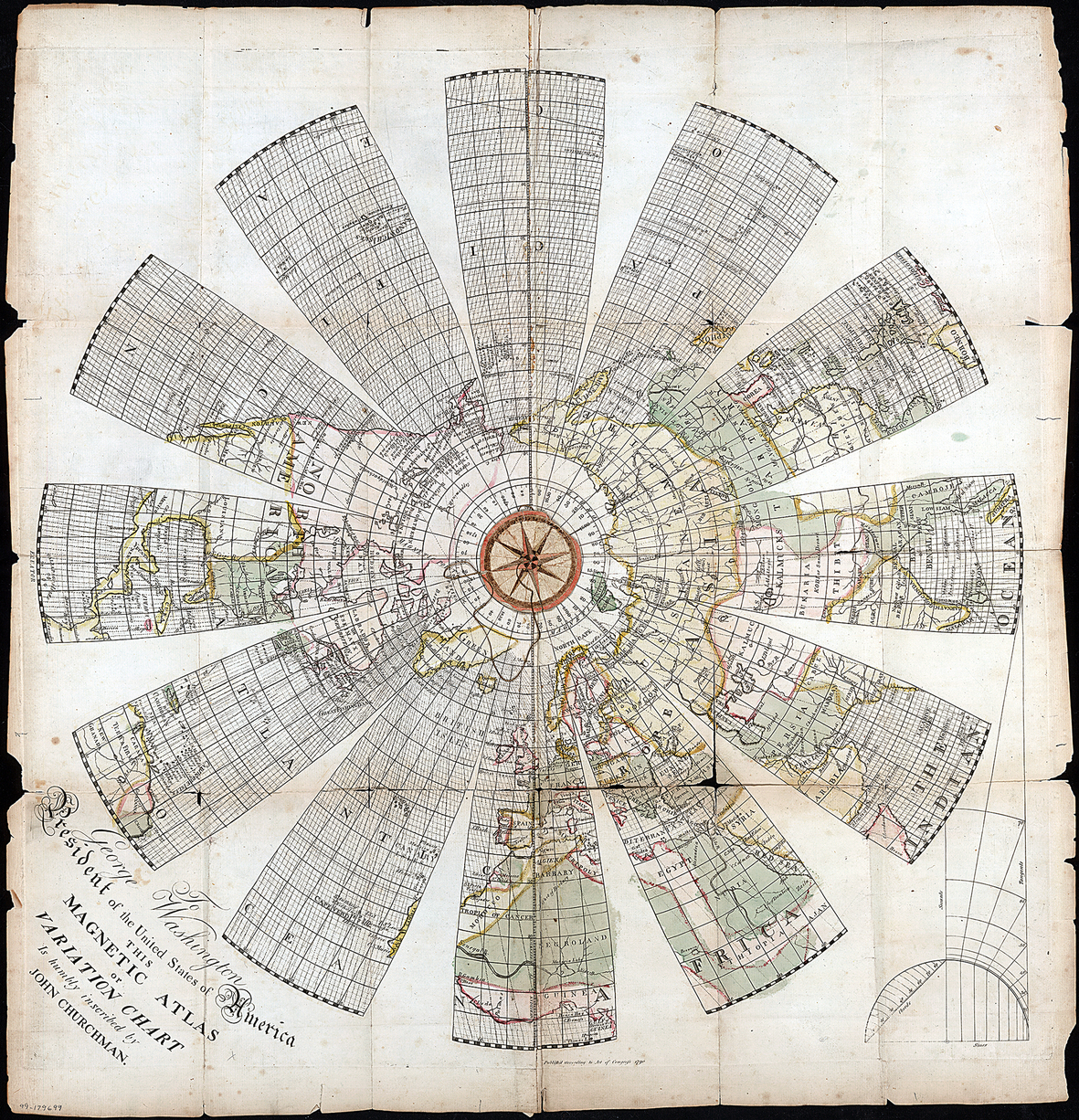

Cartography is the study and tradition of map making. A cartographer makes maps by combining geographic data with scientific, technical, and artistic principles of that time period to model and communicate visual, spatial information. Although traditional map making is being superseded by digital technologies, crowd-sourcing methods, and cloud storage/retrieval, there is merit in reviewing the early tangible map-making techniques using formats from rock to paper. A brief historic summary follows. For more information, refer to: The History of Cartography Series, a definitive collection of articles with global coverage (Harley & Woodward, 1987, 1992, 1994; Woodward & Lewis, 1998; Woodward, 2007; Monmonier, 2015). Two additional volumes are forthcoming in The History of Cartography Series, Cartography in the European Enlightenment, volume 4, by Edney & Pedley (Eds.) and Cartography in the Nineteenth Century, volume 5, by Kain (Ed.). Other bibliographies include Ristow (1997) and Karrow (1997).

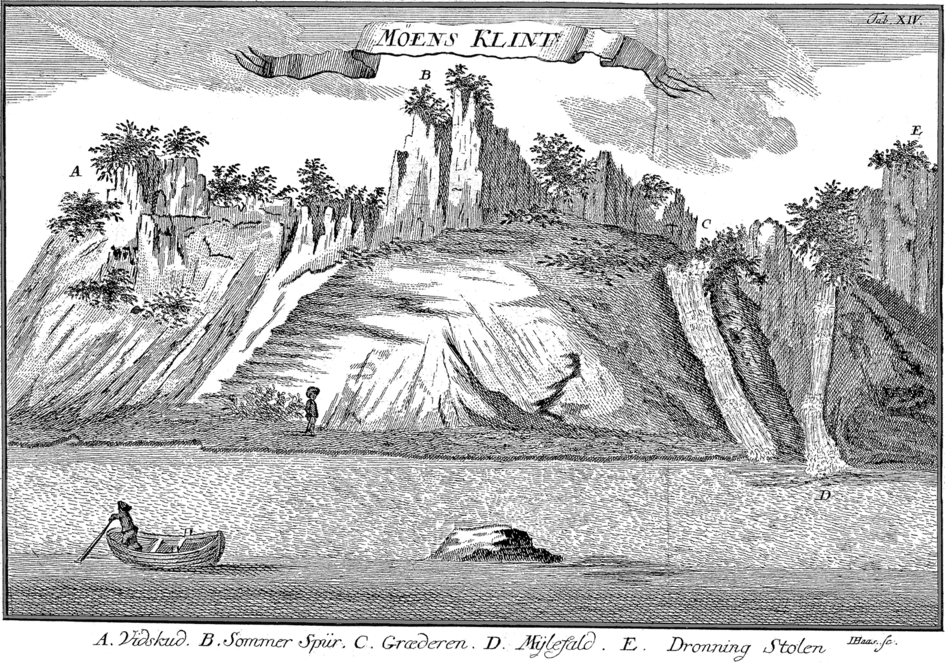

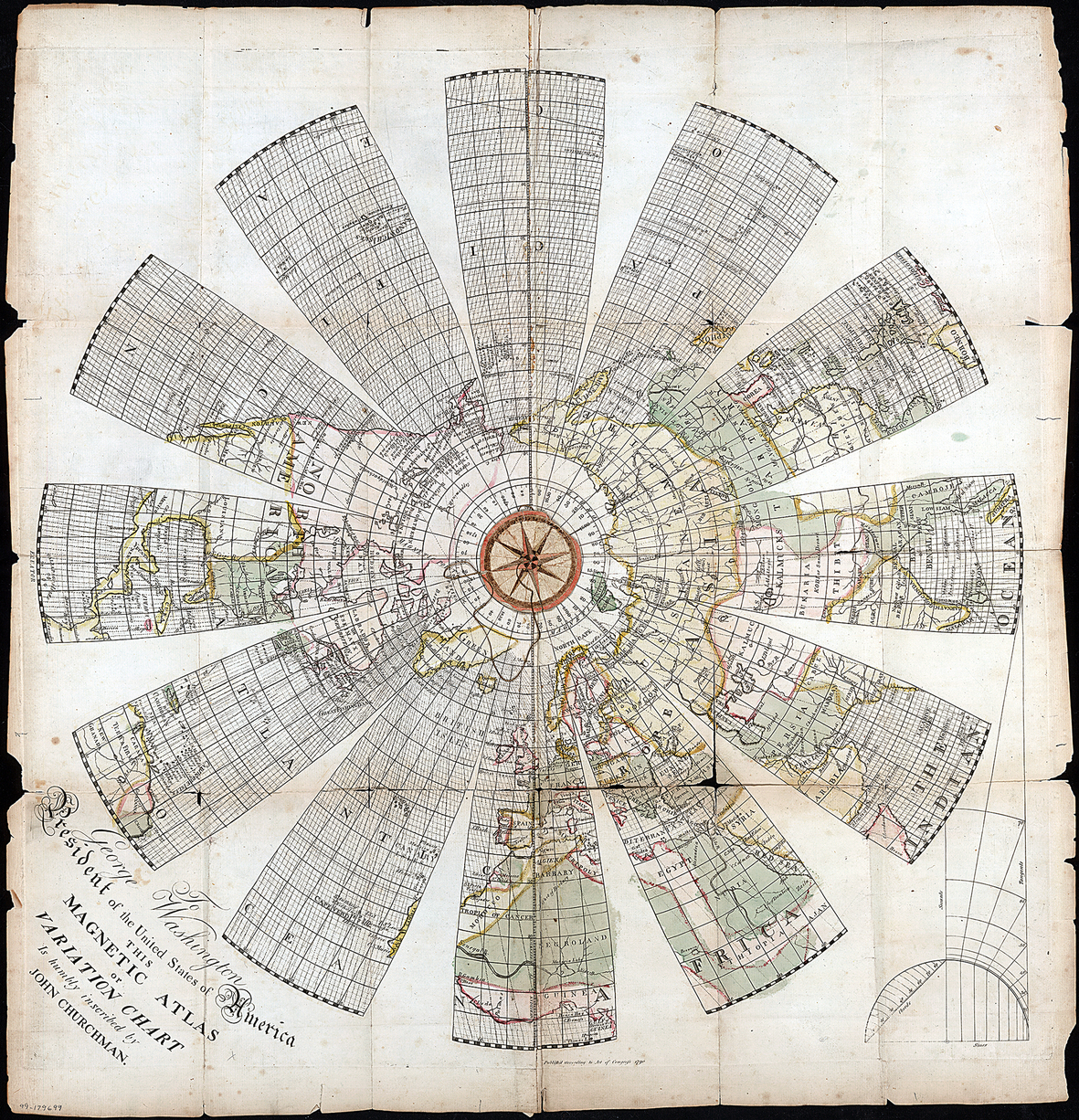

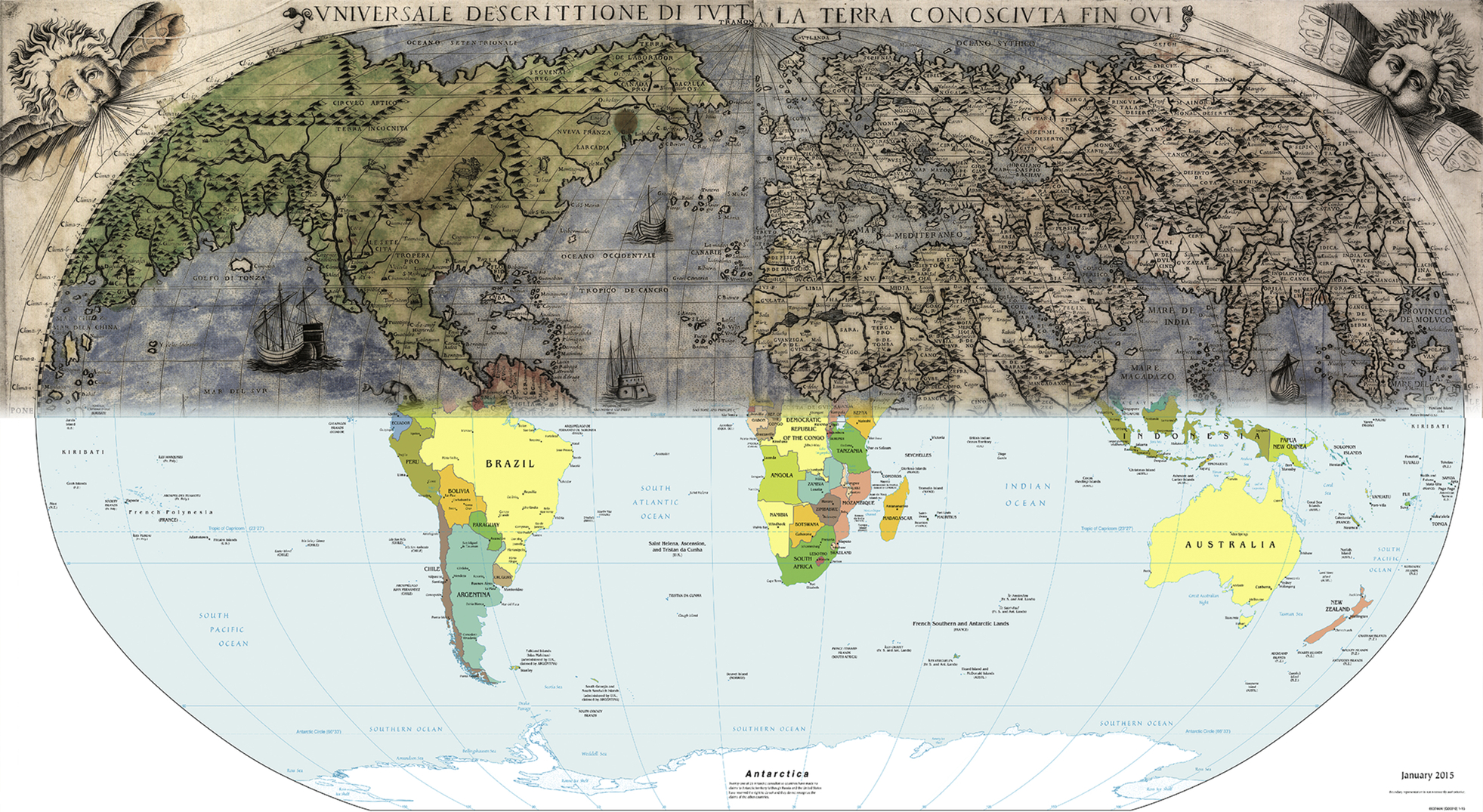

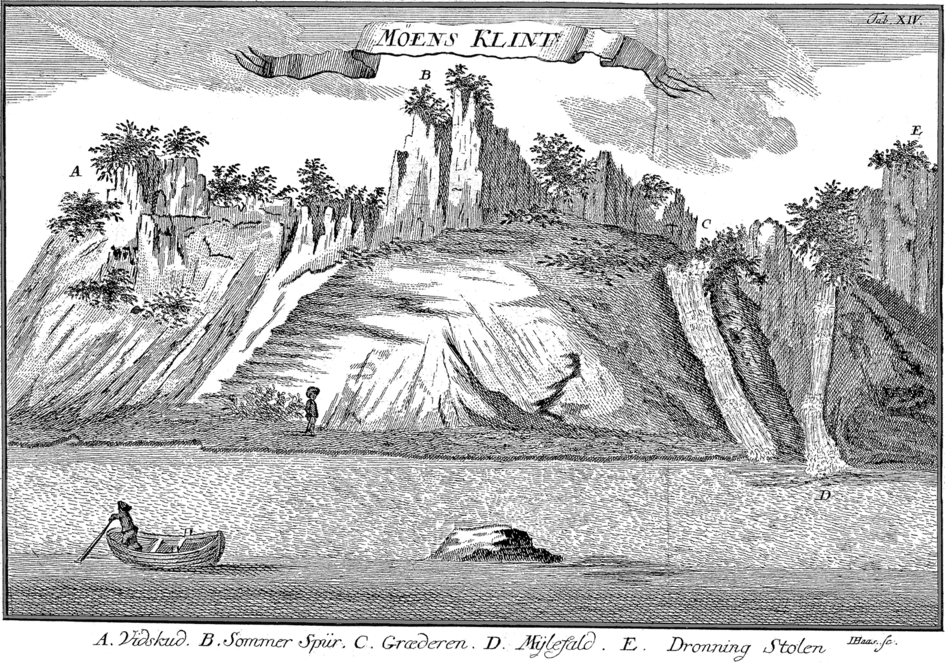

Discussions on the history of maps and cartography usually begin with ancient civilizations some 4 millennia in the past when maps were preserved on Babylonian clay tablets (Dilke, 1987). Yet, some consider the earliest map examples to be traced back 8–12 millennia and are those carved on rock or painted murals on walls (Barras, 2013; Choi & Brahic, 2009; Clarke, 2013; Meese, 2006; Siebold, n.d.; UNESCO, 1979; Utrilla, Mazo, Sopena, Martínez-Bea, & Domingo, 2009) (see Fig. 1.2). Regardless of the age, dissemination of the map was limited given fixed geographic locations of rock outcrops and buildings. As map making progressed from carvings on rocks to etchings on clay tablets, cartographers also advanced from hand-carved or hand-drawn maps to reusable map printing methods. Thus, printing techniques and lighter-weight formats increased dissemination as materials used for making maps went beyond a fixed stone or wall.

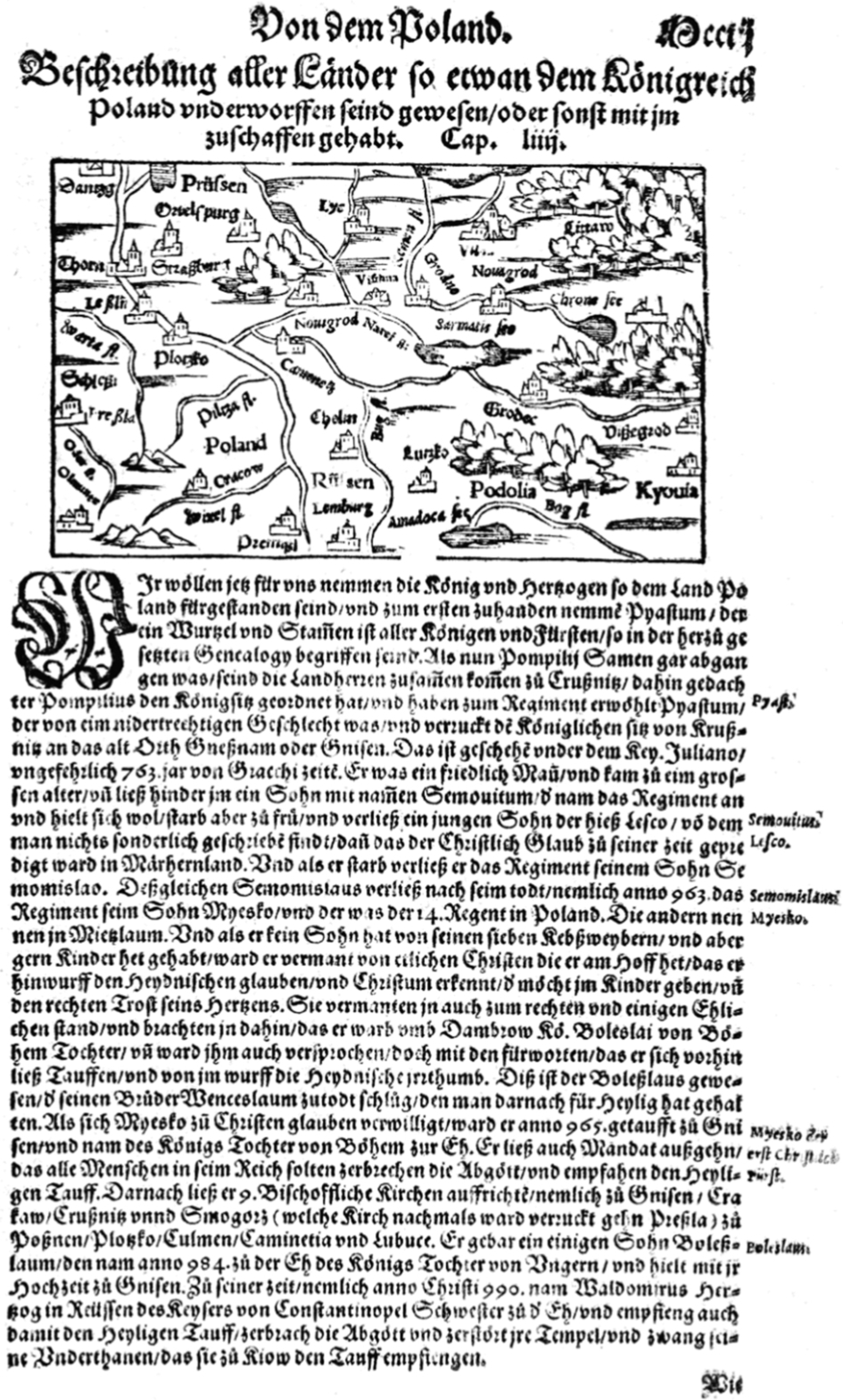

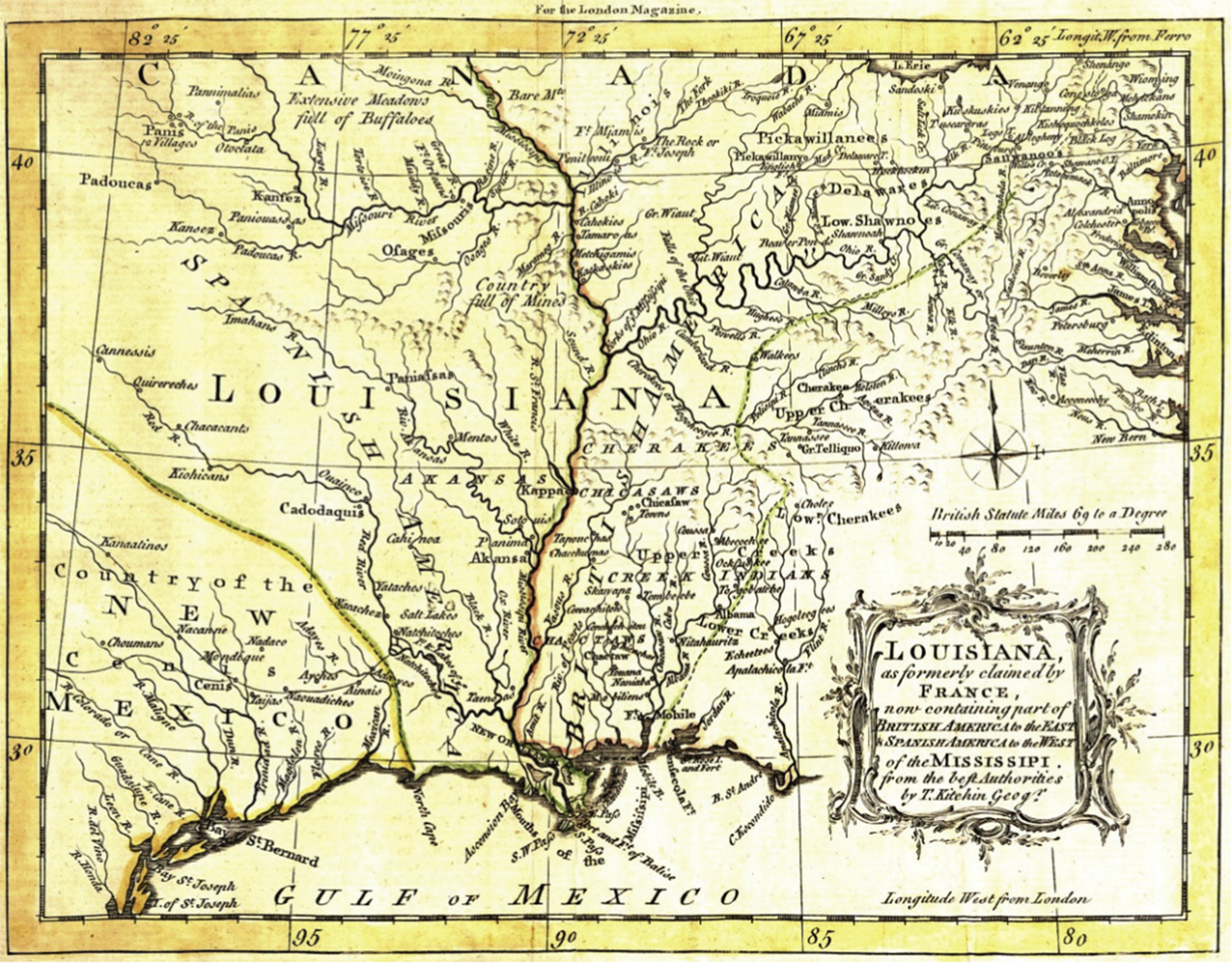

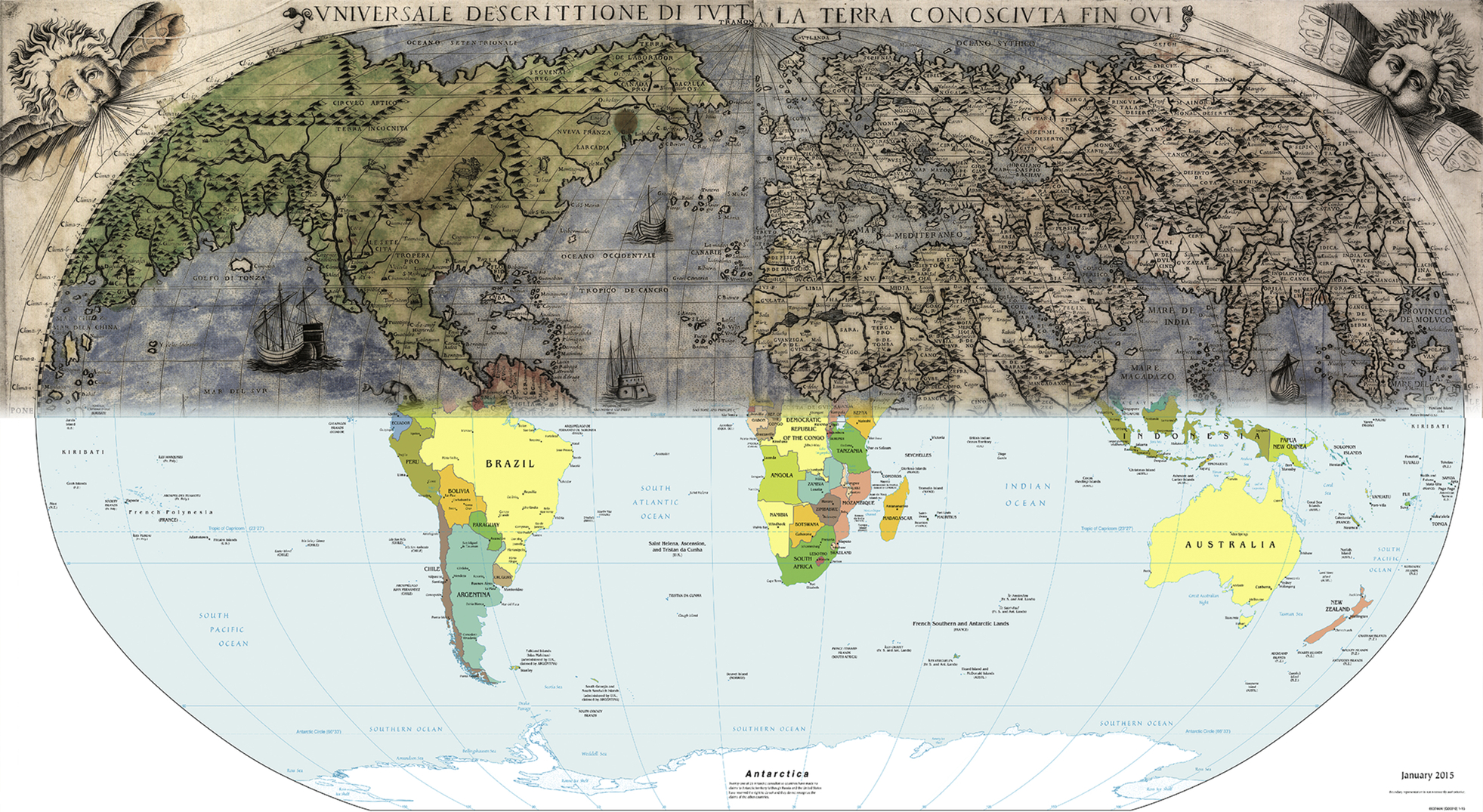

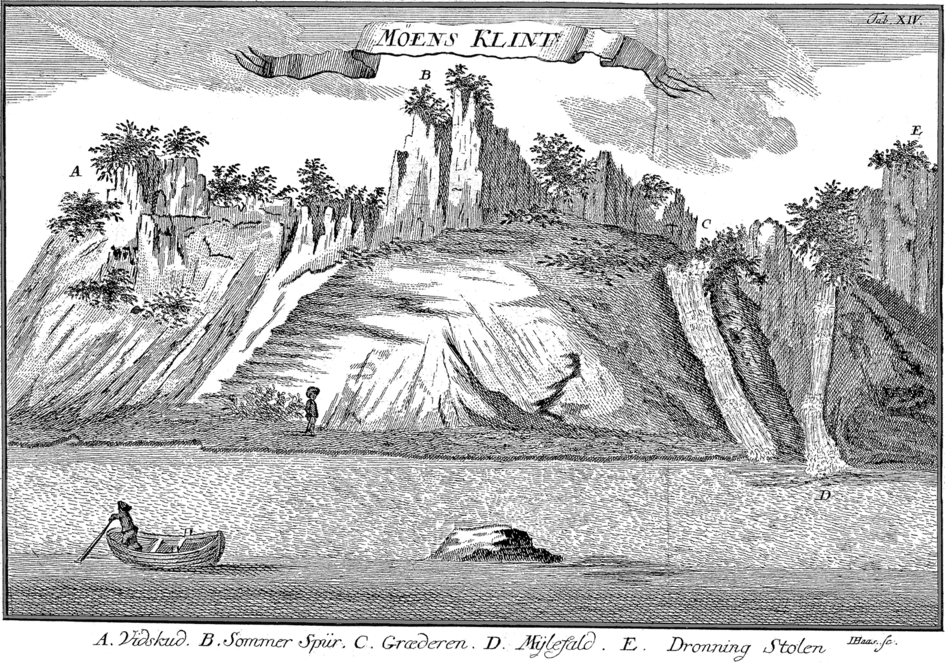

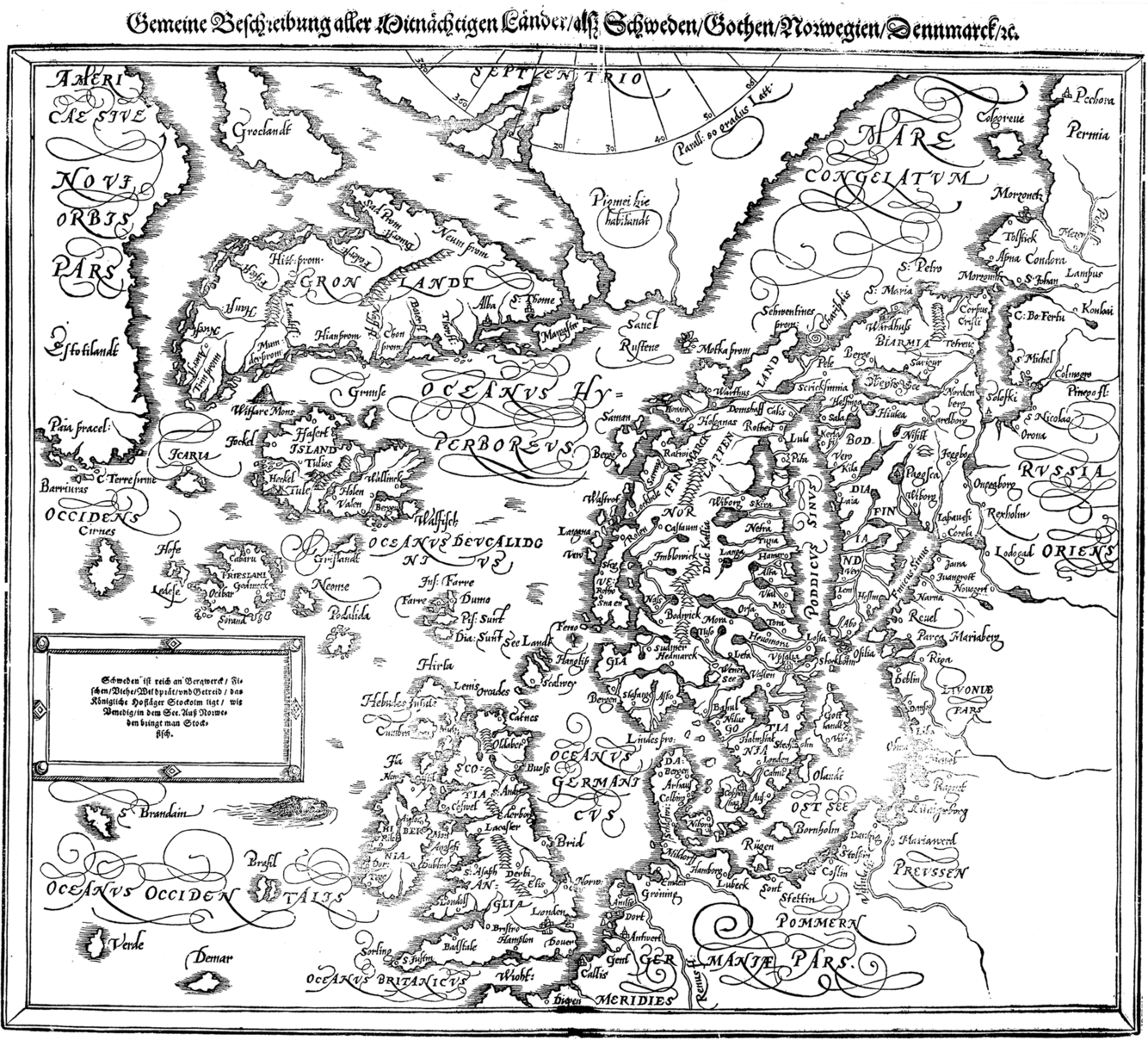

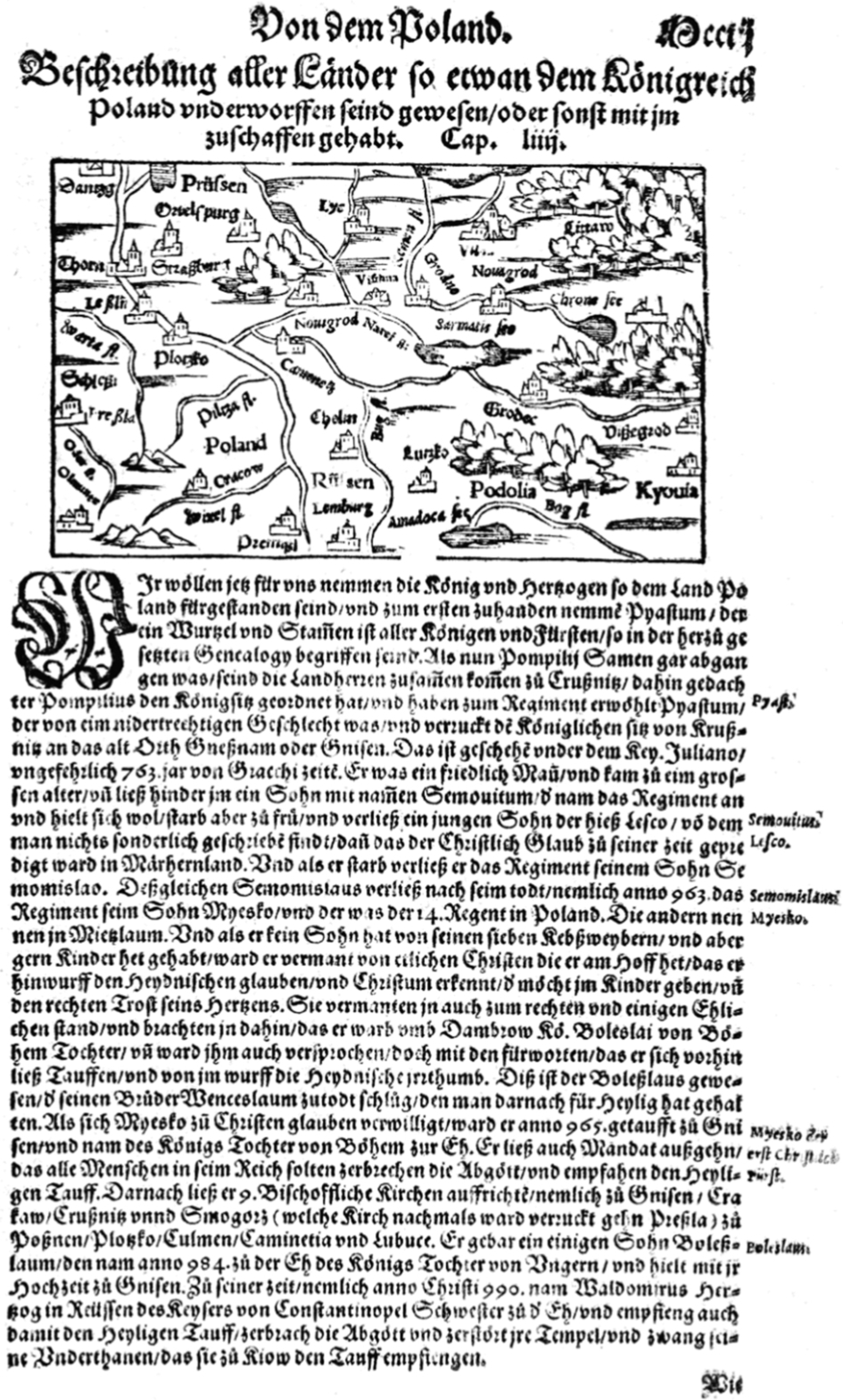

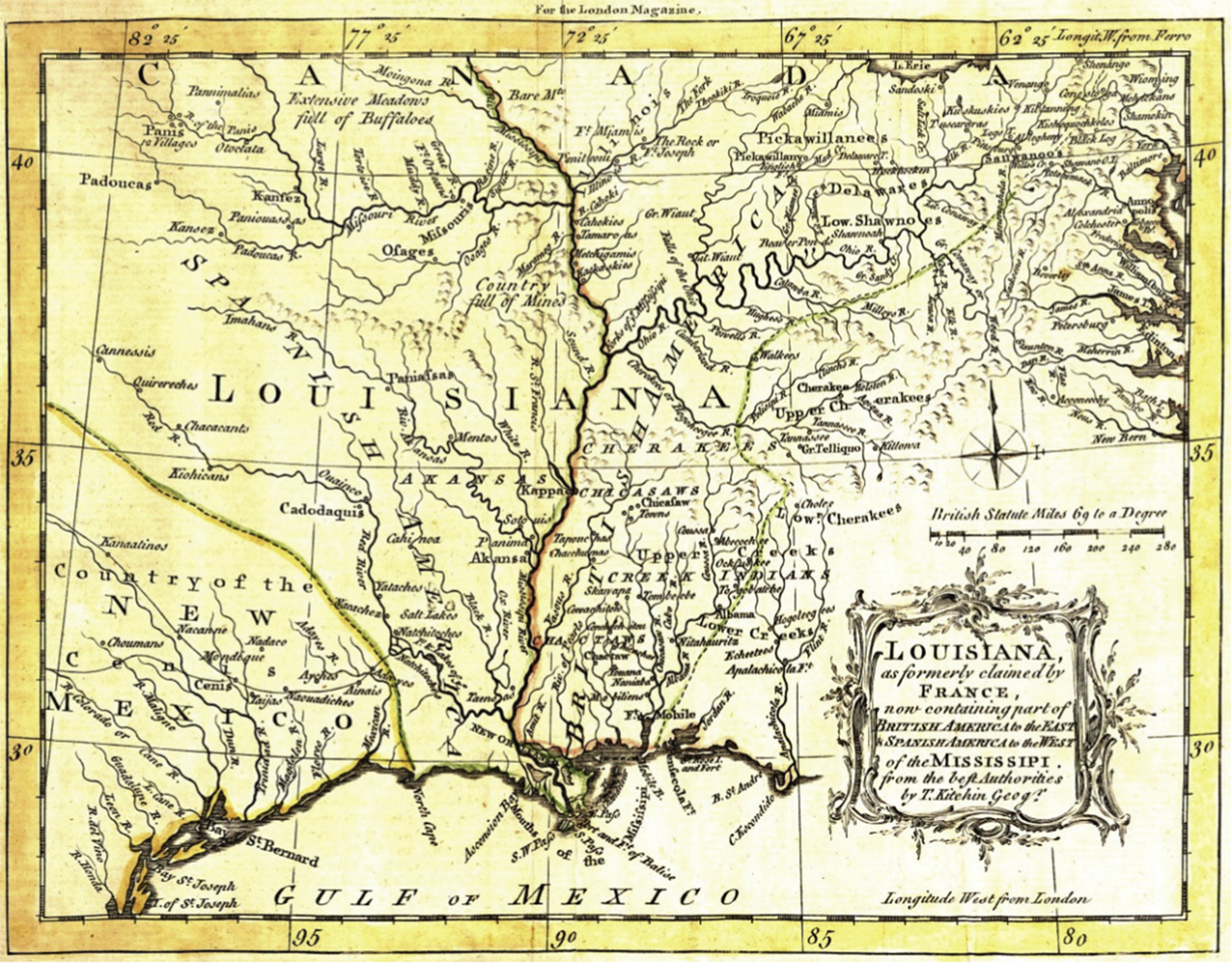

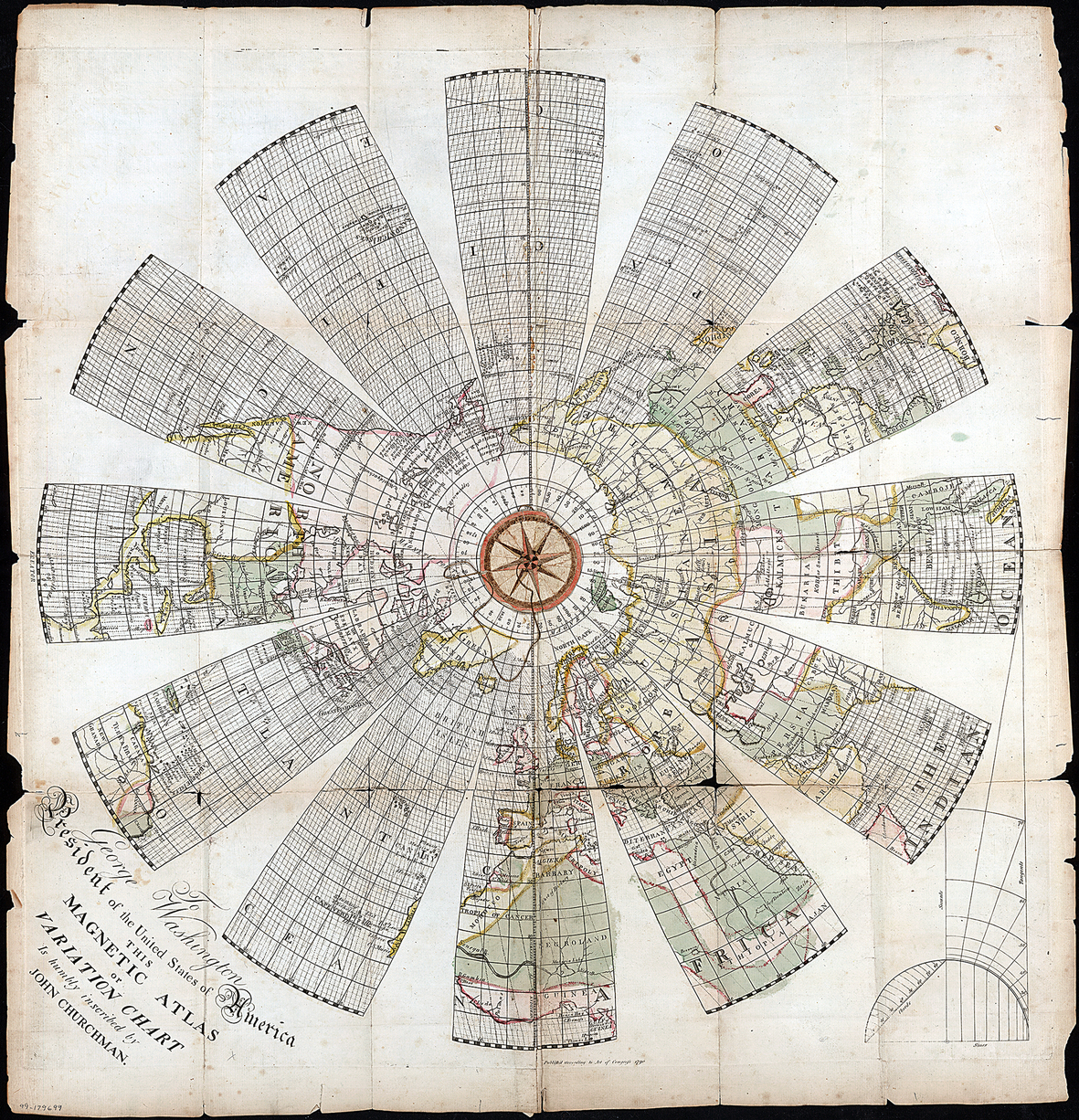

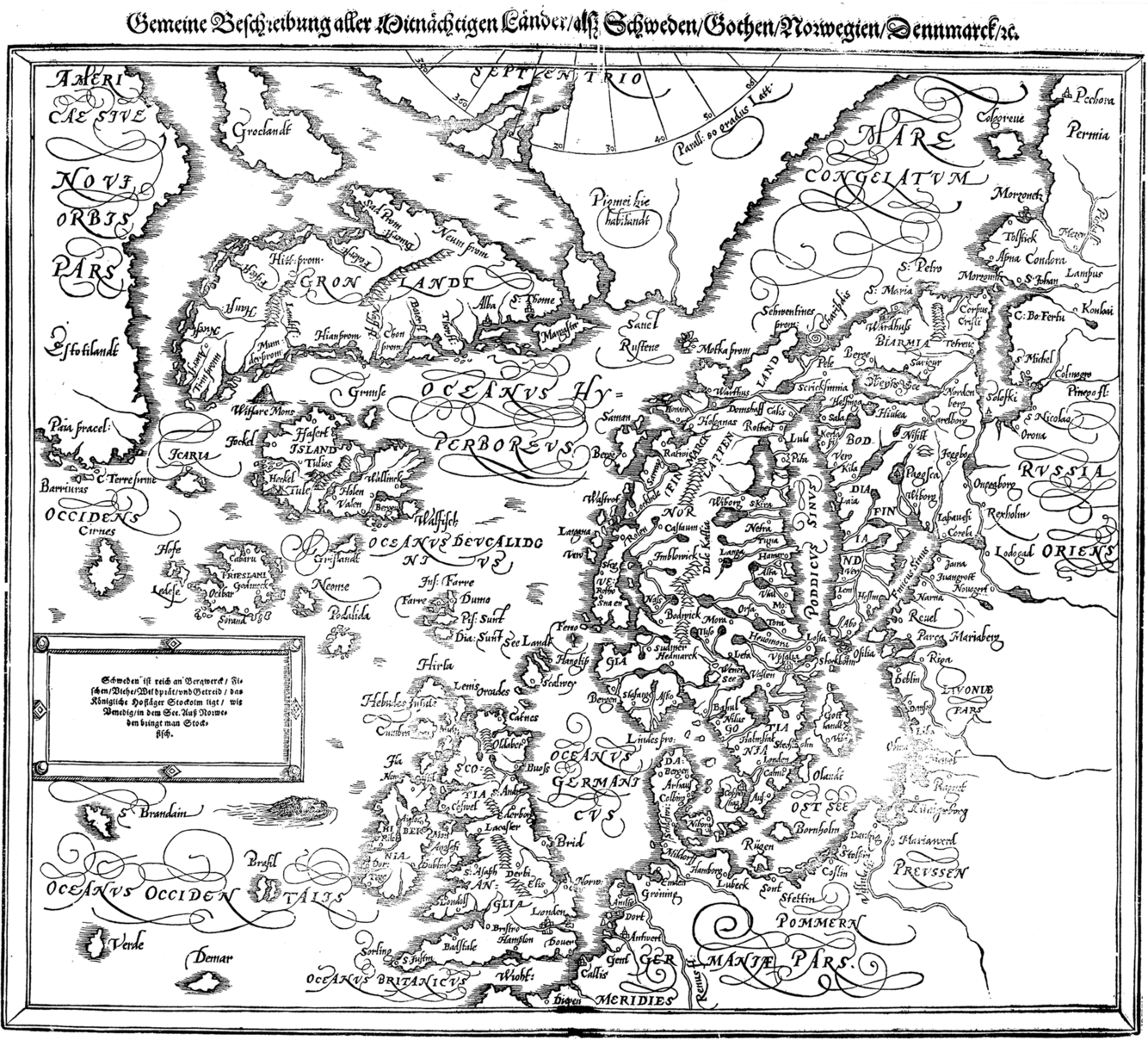

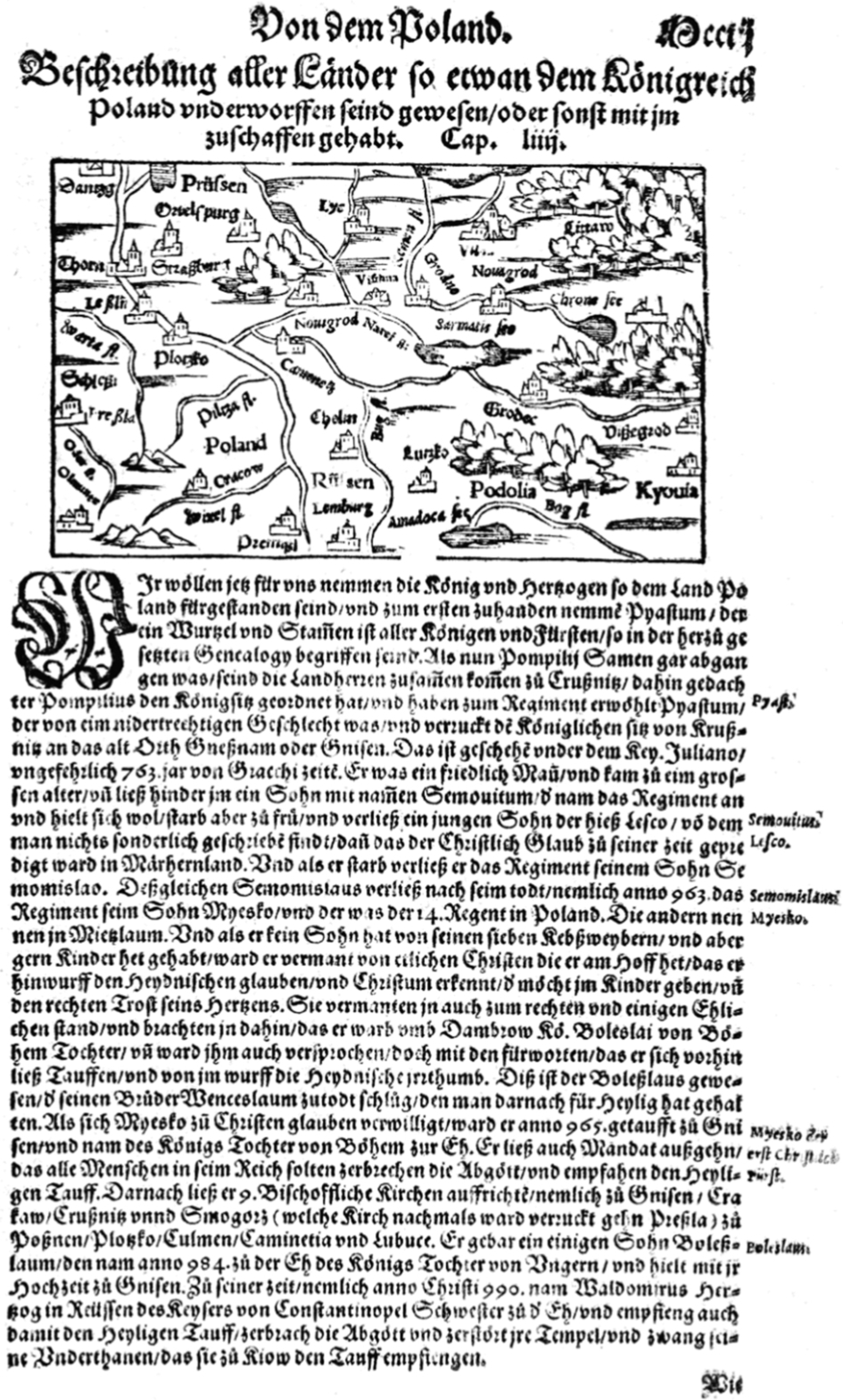

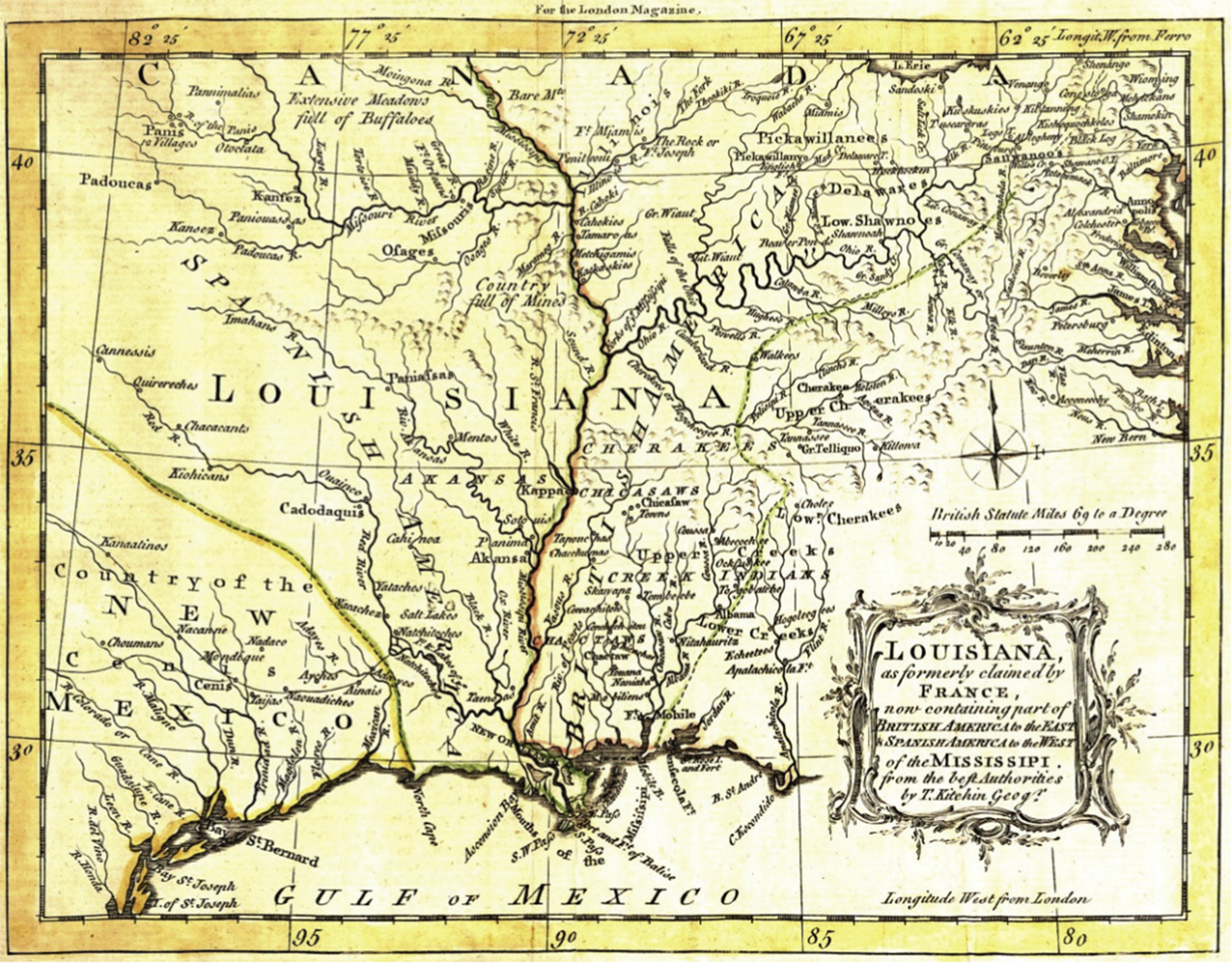

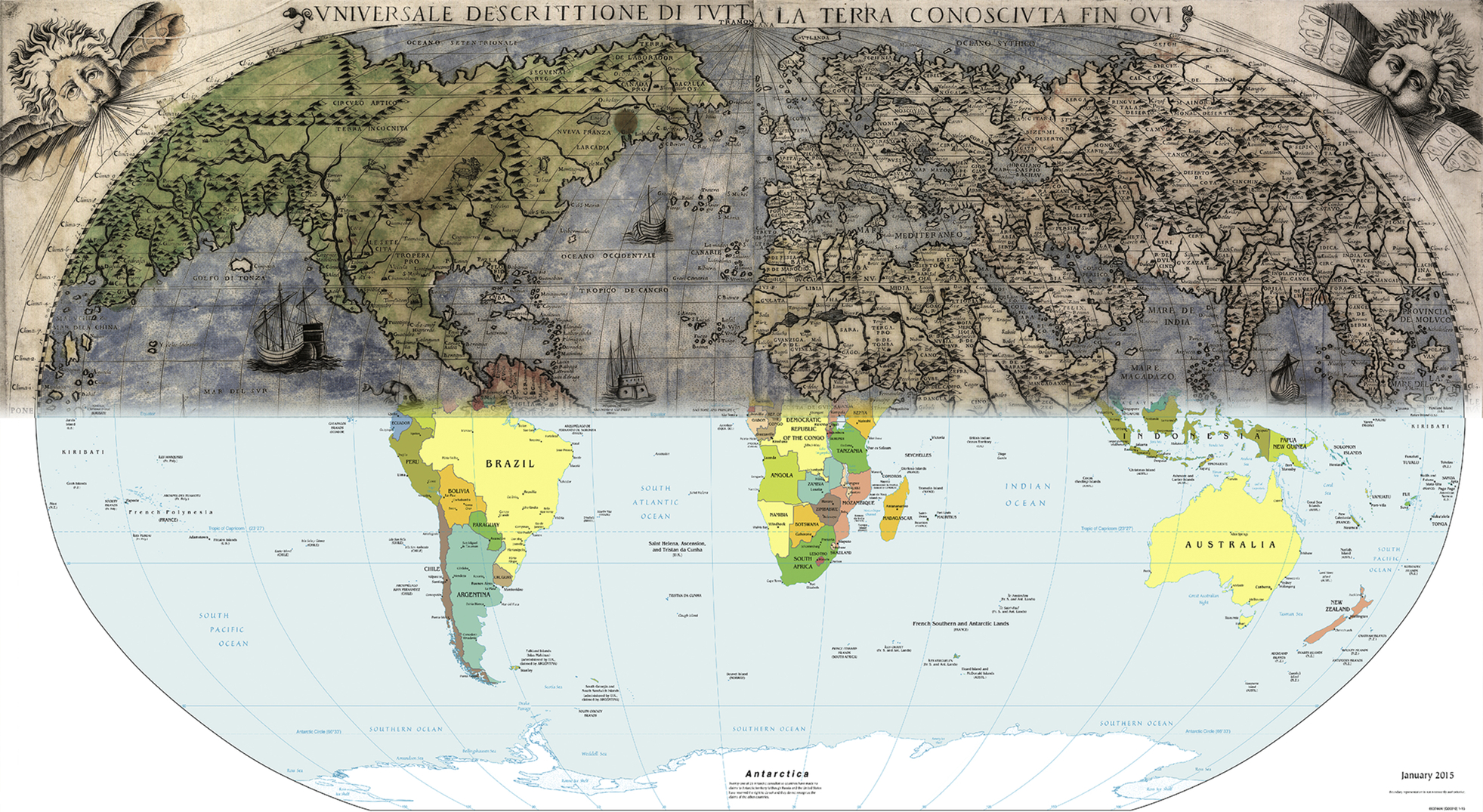

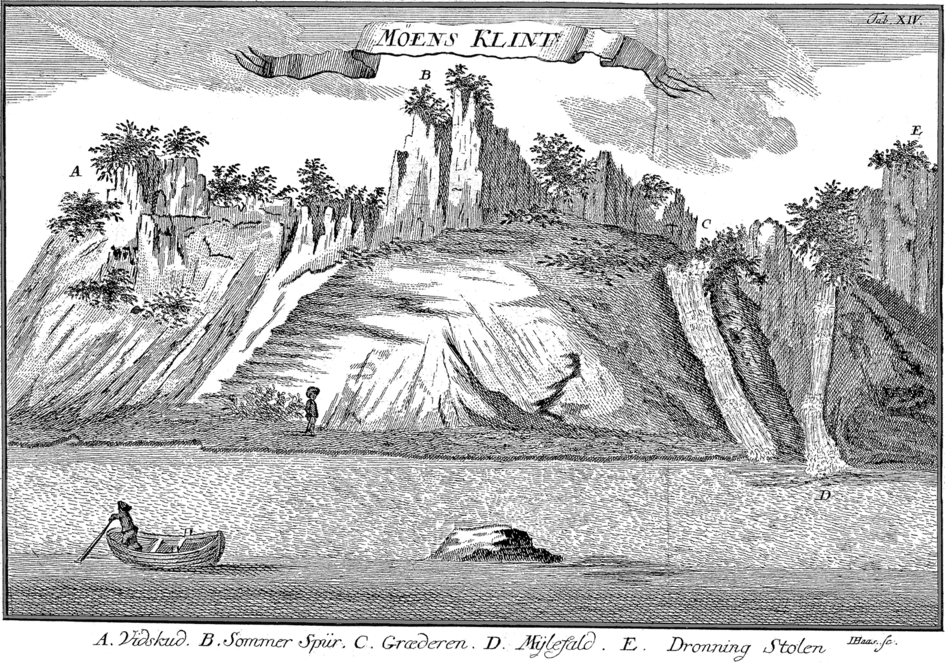

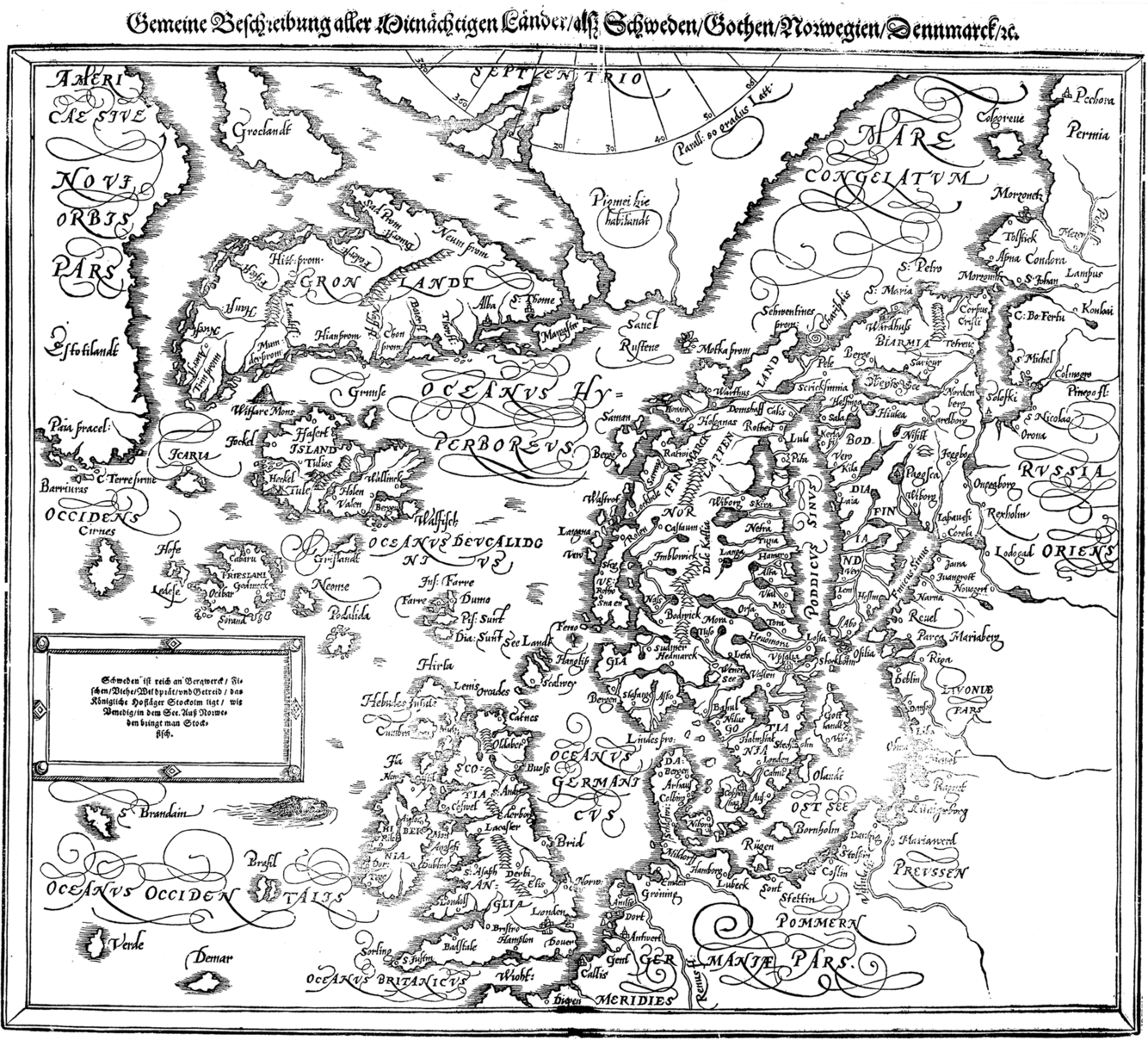

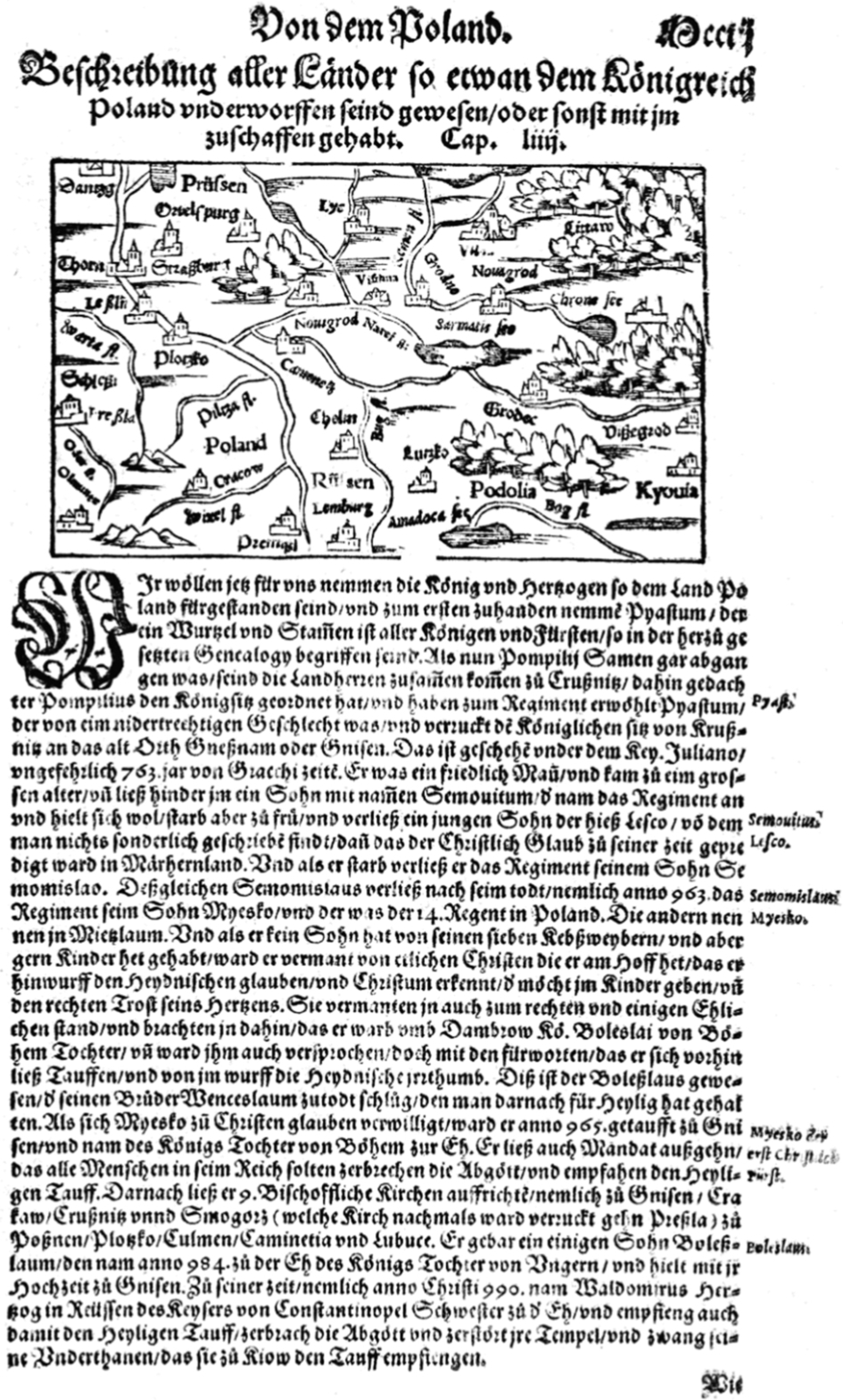

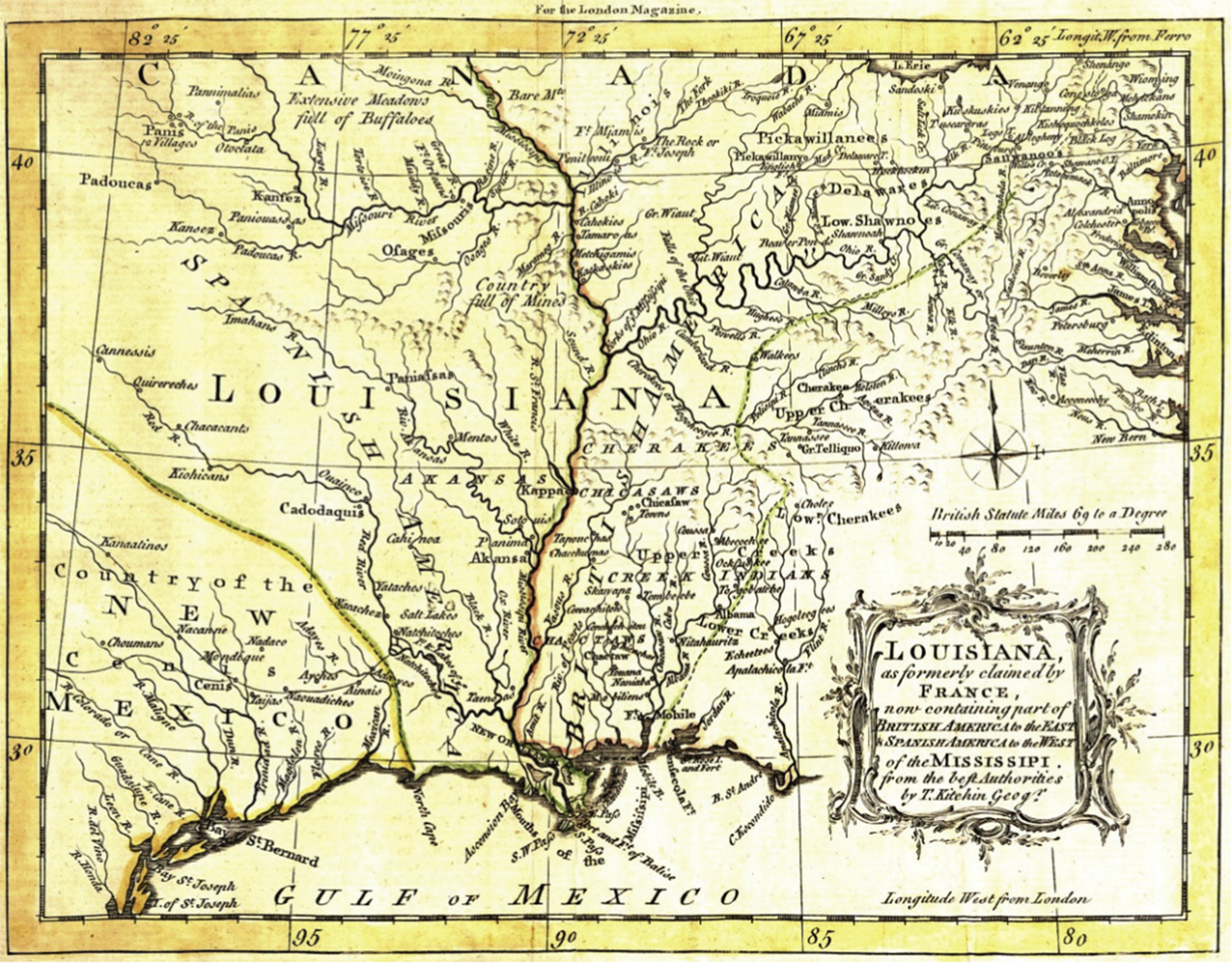

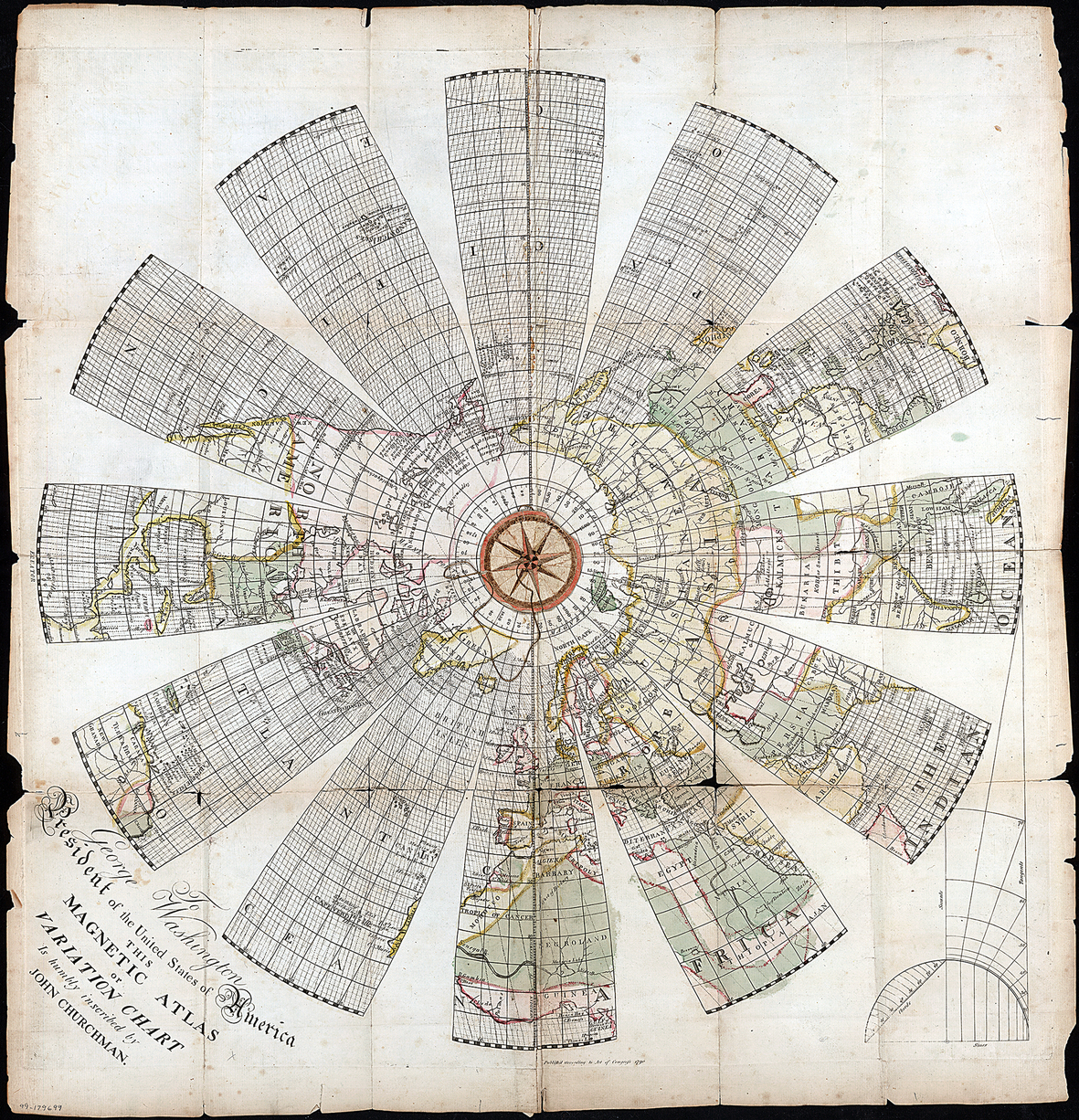

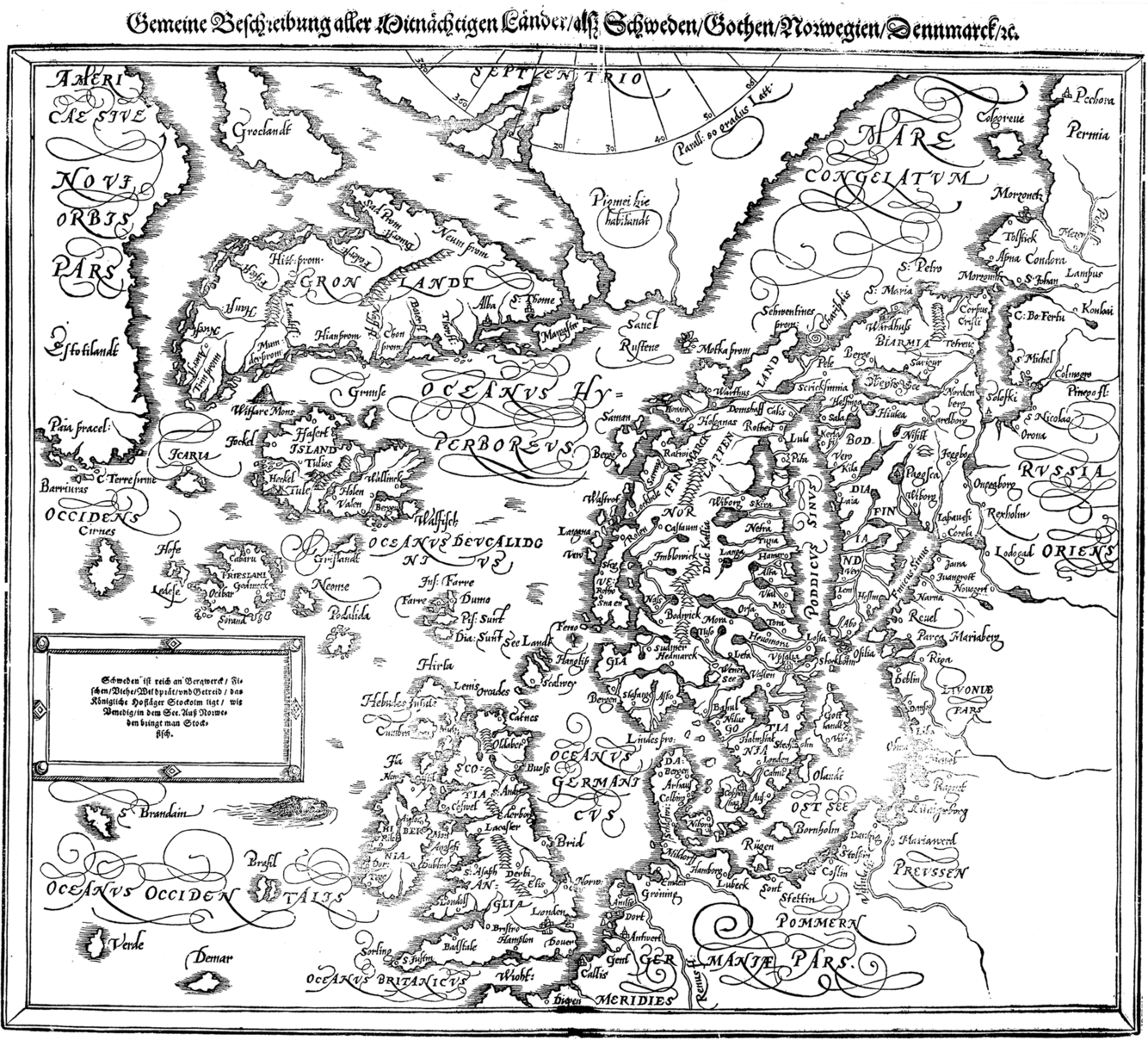

Woodblock printing was introduced in China as early as the 8th century, and the movable type printing press began in Europe by the 15th century; both of these are effective techniques for printing and reproducing text and images, see Figure 1.3 (Klooster, 2009; Temple, 2007). These improved methods for creating and printing maps were obvious advantages for dissemination, over rock and clay. Woodblock printing, common by the 13th century, gave way to copper-engraved sheets and plates by the 16th century, see Figure 1.4. This modification allowed maps to be more detailed and easier to reprint from the reusable metal sheets that could be hammered and re-engraved if changes were needed (Woodward, 1975, 2007). In fact, the copper-engraved plate for map printing was state-of-the-art for some 300 years until recently (Fitzgerald, 2002; Evans & Frye, 2009; Woodward, 2007).

The trend today is moving from print-based map making to film or digital-based cartographic methods. In fact, the main American mapping agency, USGS, discarded their historic copper and steel engraving sheets and plates in 2014, in favor of digital map making, storage, and printing (Newell & Domaratz, 2015; Morais, 2014).

As each method for map printing changed, the materials used evolved as well, from papyrus, parchment, silk, linen, hand-made or machine-made paper to synthetic film and on to digital data images (Brandt-Grau & Forde, 2000). Just as map-making methods and materials evolved, so did the role of cartographer, who was both the map-making professional as well as the printer, who engraved metal plates and combined ink with moveable metal type using a mechanical press.

According to the Occupational Outlook Handbook, the job of a cartographer today is primarily a profession in teaching and research (Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, 2014a). The cartographer role as map maker works with surveyors and photogrammetrists (Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, 2014b). The entry for printer is no longer a specialized profession, but as a print worker technician who can “operate laser plate-making equipment that converts electronic data to plates”; the worker is expected to “calibrate color settings on printers, identify and fix problems with printing equipment” (Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, 2014c). Just as the cartography professional has changed focus, the printer usually refers to an electronic machine, not a person in a professional career.

The advent of digital map making and printing arrived in the latter half of the 20th century, with the last decade being the tipping point. In “early 1990s, nearly all maps were distributed on paper,” and by the end of the decade, more maps were transmitted through the Internet than printed on paper (Peterson, 2014, pp. 1, 12).

In the early 2000s, web development advances created the Geoweb Revolution (Dangermond, 2009; Haklay, Singleton, & Parker, 2008). The GeoWeb led Goodchild (2007) to propose the term Volunteered Geographic Information when describing nonexpert citizens who create, assemble, and disseminate geographic information using web services and digital sources without the use of Geographic Information Systems or GIS. By 2010, Penn State Public Broadcasting summarized the power of digital mapping with the online project, Geospatial Revolution (PennState, 2010). Penn State offered a free, online course, Maps and the Geospatial Revolution (PennState, 2016). These rapid changes herald a new perspective on map formats and map-making methods or a new geography and cartography that expanded the definition of geo-literacy.

NeoGeography is a recent term that describes the divisions between traditional geographic roles of subject, producer, communicator, and consumer blurring together (Goodchild, 2009). Where traditional geographic work involved a more regimented hierarchy between these factors, NeoGeography leverages technological and social changes since the turn of the century to allow consumers to be subjects, producers, and communicators all at once. This movement has been made possible largely by the power of the Internet, where most NeoGeographic activity takes place (Rana & Joliveau, 2009). The empowering of users through geospatially enabled technologies such as Global Positioning Systems (GPS), the Internet, and user-friendly cartography tools has allowed for those without formal training to become involved in a broad range of NeoGeographic activities (Clark, 2008). One factor that sets NeoGeography apart from traditional geography is that its practitioners are often not geographers by training; instead, they come from technology and engineering fields which are already deeply involved in online and mobile development. This has created a discrepancy or disconnect, as traditional geographers come from an academic world built on peer-review, whereas many NeoGeographers come from a more entrepreneurial technology background (Rana & Joliveau, 2009).

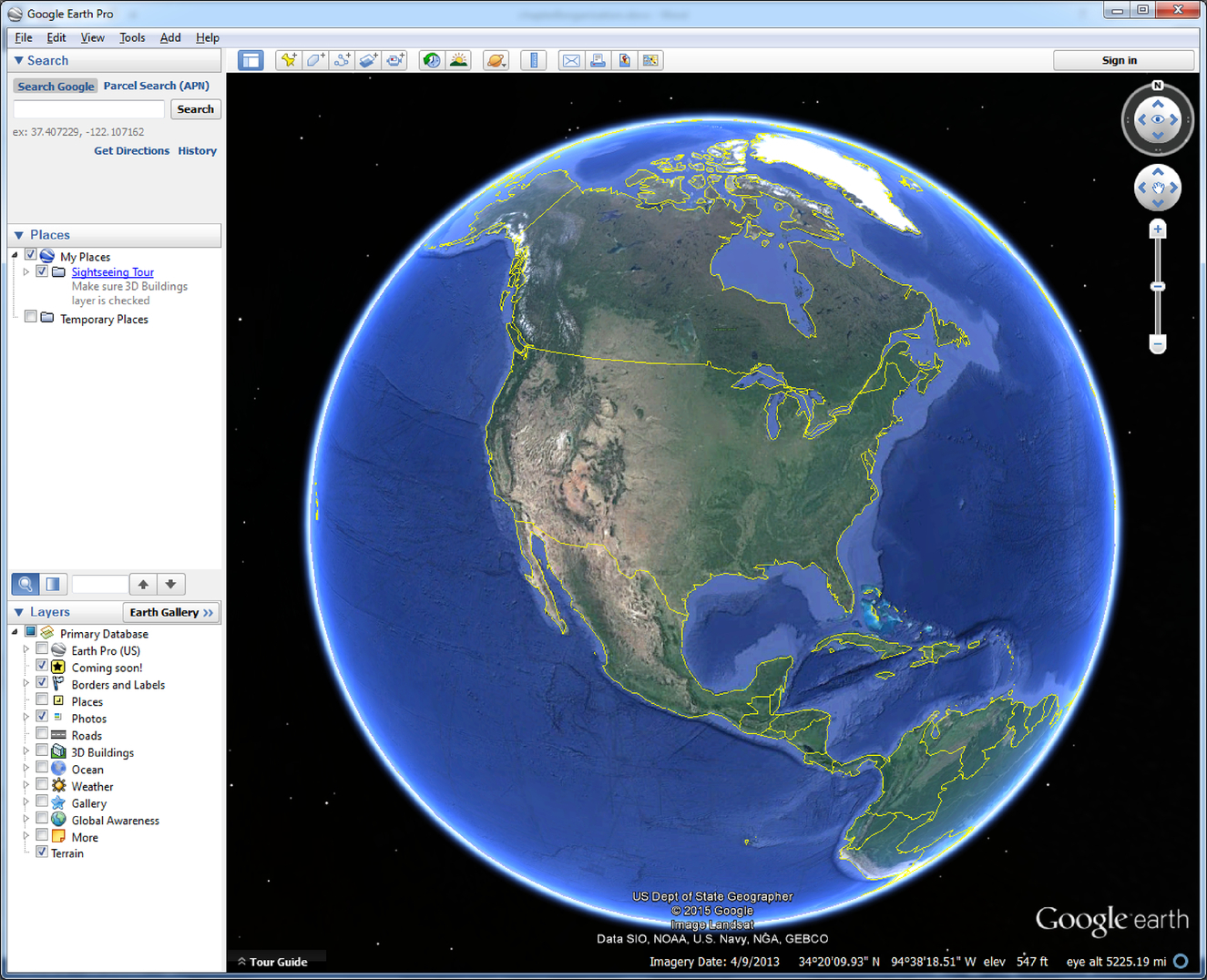

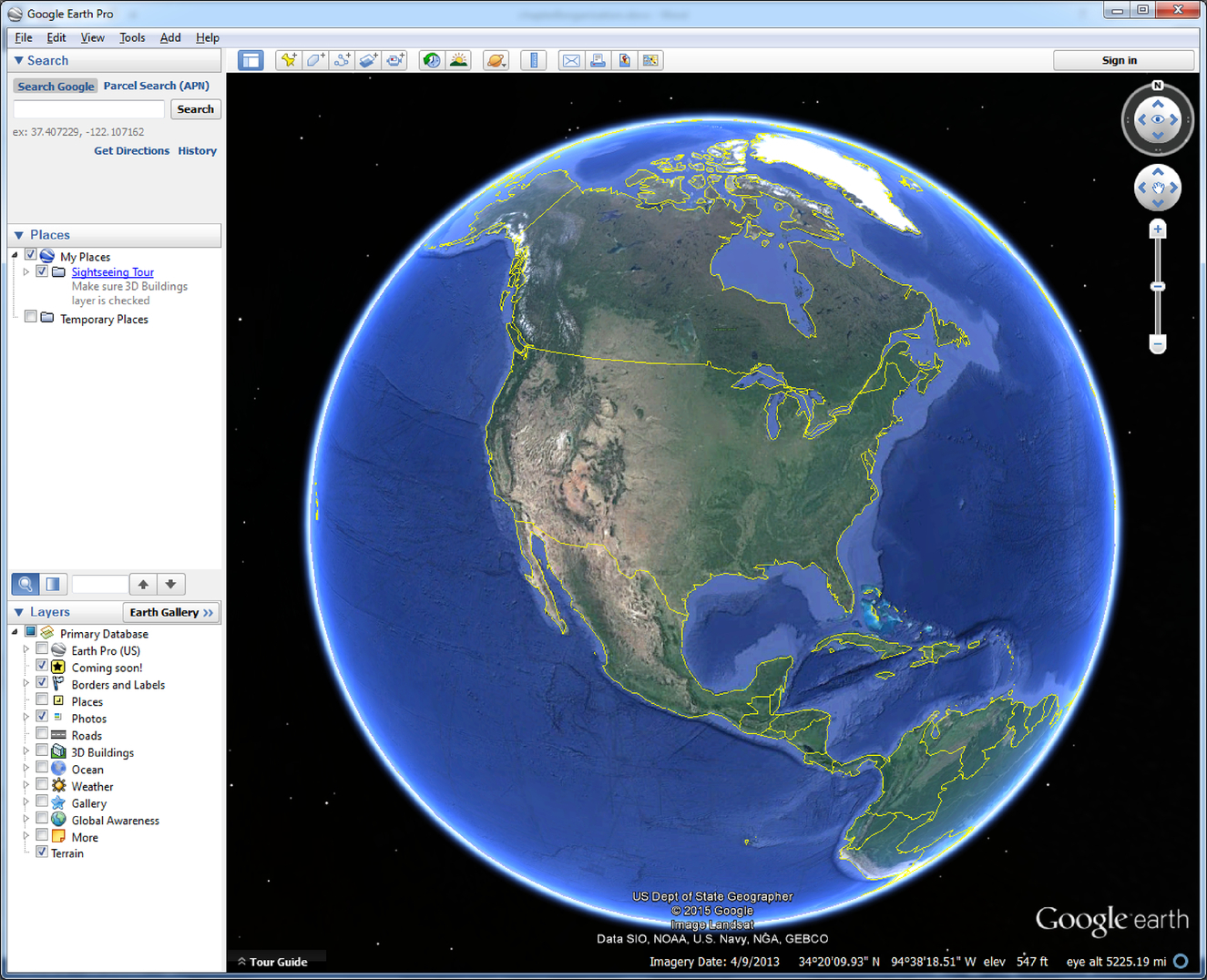

NeoCartography technologies are the flip side of the NeoGeography coin, providing a visual platform for individuals to present and analyze their work (Monmonier, 2013). Like NeoGeography, many individuals involved in Neocartography lack a background in cartographic work. Their efforts often involve open-source data and GIS/cartography technologies (Commission on Neocartography, 2011–2015). These include platforms such as OpenStreetMap, Google Maps and Earth, Mapbox, and more coding-centric web platforms like D3, jQuery, and Leaflet. Other data sources include social media content, such as public Twitter and Facebook feeds.

One example of this divide between traditional geography and cartography and their Neo- equivalents can be seen in Google’s Earth and Maps products. Traditionally, maps are treated as arbiters of truth and reality, serving as authoritative sources of knowledge about topics like borders and place names. With a global audience, Google’s products pragmatically deviate from this tradition by inviting users to participate in knowledge production and tailoring knowledge to local audiences rather than presenting one single vision of the world (McLaughlin, 2008). In practice this means that borders and place names may change on the map depending on where they are accessed. For example, the boundaries of the contested Kashmir region located between India, Pakistan, and China are drawn differently in Google Maps depending on the origin of a user’s IP address (Dominguez, Hurt, Wezerek, & Zhu, 2014). The Crimean peninsula is another contested territory whose borders change depending on whether you are viewing Maps from the United States, Russia, or Ukraine.

The existence of multiple truths for different audiences may be a pragmatic move on Google’s part in terms of not upsetting local populations, and therefore being allowed to continue to do business in nations such as China, but it deviates from geographic and cartographic convention. It also leads to tensions between nations and in some cases has inflamed existing international conflicts (Gravois, 2010). Naturally, this issue is larger than Google’s specific practices and speaks to the interconnected nature of human existence today, but it also highlights some of the modern challenges that NeoGeography, NeoCartography, and their practitioners face.

A good example of the positive influence of NeoGeography and NeoCartography is what is known as crisis mapping. In online crisis mapping, volunteers search and process data collected from individuals via mobile phone, e-mail, and social networks such as Facebook and Twitter; then place the information into an online mapping interface. The information presented as a map mashup of multiple data sources could be produced a continent away, yet still communicate what is most urgent for local responders. The immediate consumers of this geographic information are disaster-relief workers, provided with exact coordinates to direct them where to go and images to prepare them for what to expect. An example is the rapid response teams from the GIS Corps who mapped the human impact of a massive 2013 typhoon on islands in the Philippines (Joyce Monsees, personal communication, Nov. 11, 2013).

These practices have had a direct, positive impact on human lives through disaster response. Our past and present reliance on print and digital maps, as well as geospatial technology to navigate and communicate, extends locally to globally in both scope and purpose. This underscores the fact that we are immersed in a global geospatial revolution that is ubiquitous and invaluable. Crisis mapping efforts exemplify NeoGeography, the blending of communicator and consumer.

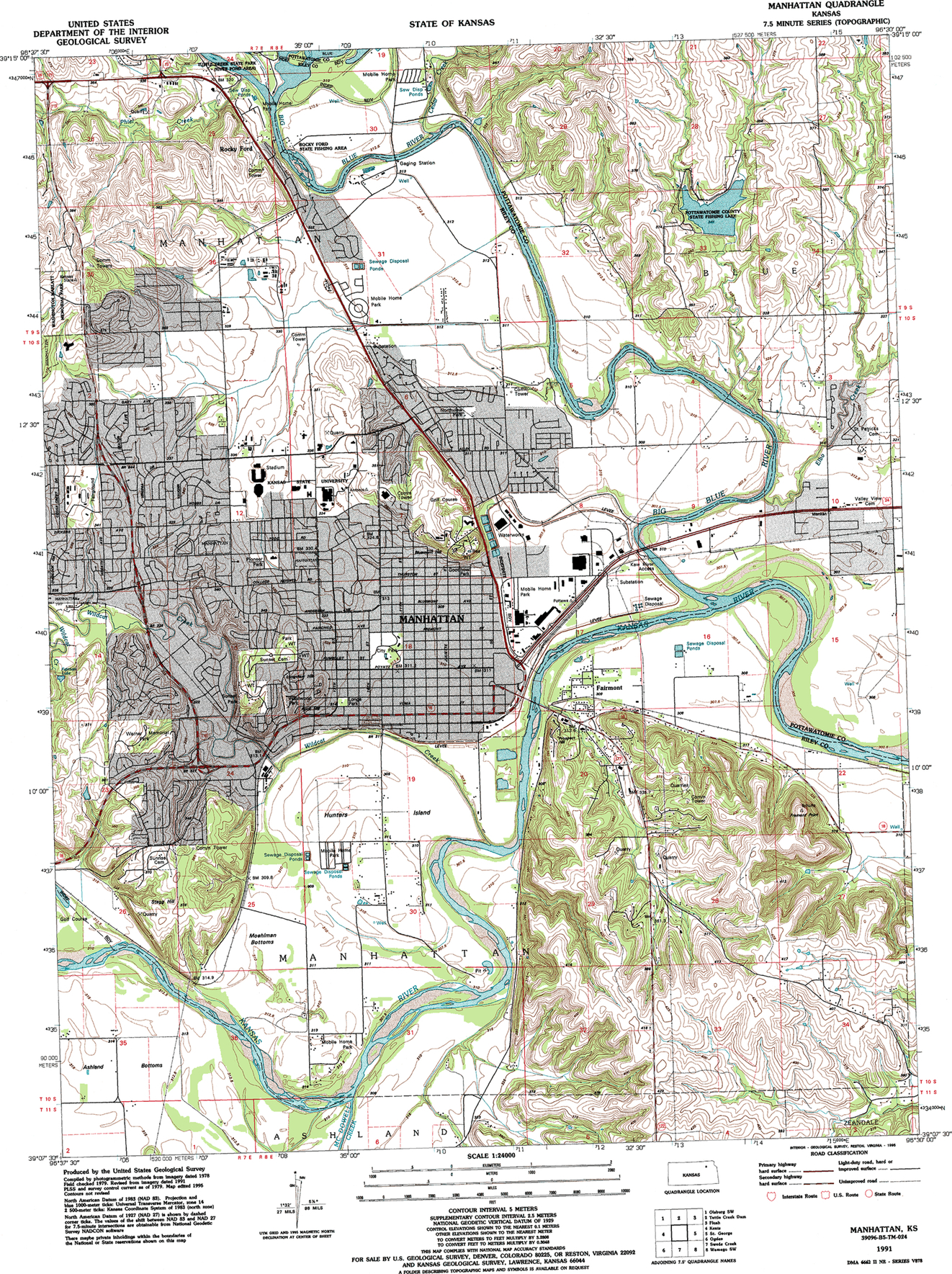

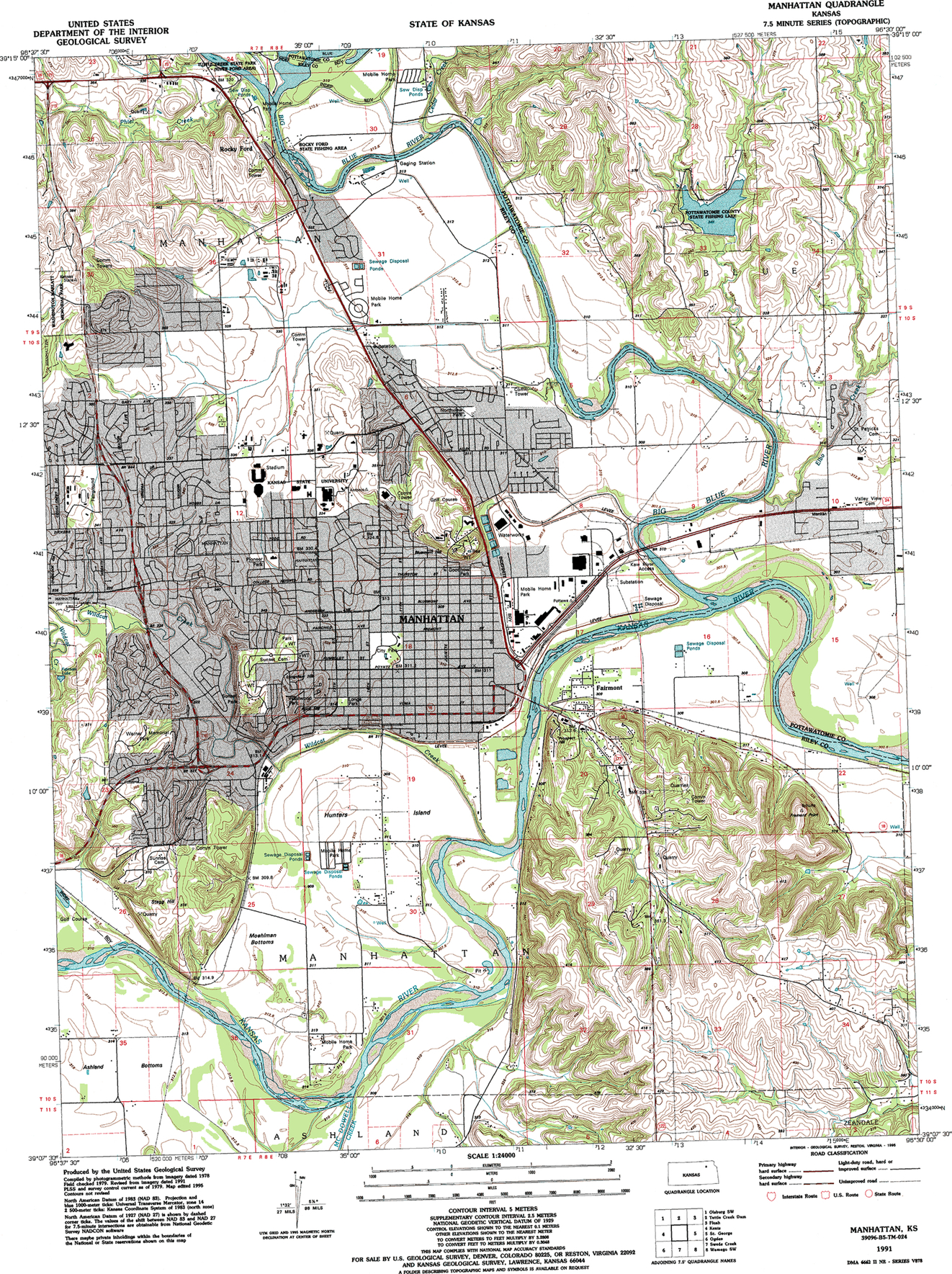

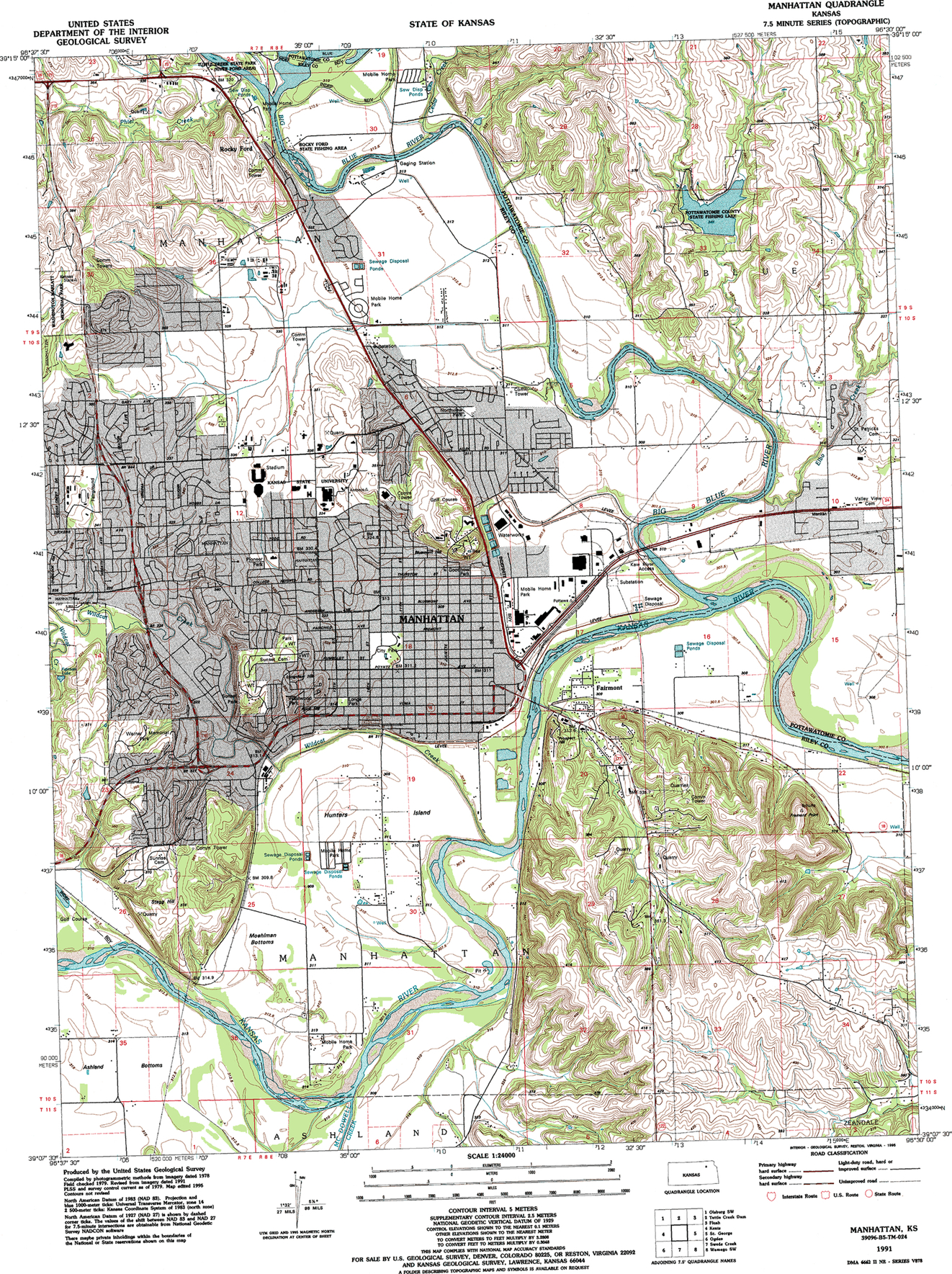

Given the long history of cartography, map caretakers likely existed for millennia. However, map librarianship as a professional Library and Information Science (LIS) career track is a 20th-century phenomenon. The demand for map library collections and librarians was evident with improved map making and printing techniques as well as greater interest in geography given two World Wars, ease of travel, and globalization of information and business. What really filled most library collections was the plethora of military maps created by 1945. This was followed by an enormous volume of print maps resulting from the USGS program to map the nation with large-scale maps at a 1:24,000 scale produced from 1947 to 1992 (Cooley, Davis, Fishburn, Lestinsky, & Moore, 2011). This U.S. topographic map series was distributed for free to all designated libraries participating in the Federal Depository Library program (Federal Depository Library Program, 2013). Knowledgeable map librarians were needed to classify and catalog these collections and help patrons, since public access to maps in depository libraries is required by the government (Federal Depository Library Program, 2014). Although there were exceptions of some academic libraries, these map collections were rarely classified and cataloged, which was primarily due to a scarcity of LIS map courses and librarians who were trained in map cataloging.

Without geo-literacy, librarians lack experience and have treated maps as the problem children of the collection. This was the belief of Walter Ristow who passed away in 2006 at age 97. He has been called the most influential figure in U.S. map librarianship. While Ristow was a prolific map librarian scholar and did much to advance the field, librarians were slow to provide needed technical, reference, and instructional services in the library. Historically, Larsgaard (1998) explained that "in the early 1900s, most spatial-data collections were administered by persons with varied academic and professional backgrounds, few of whom had any professional training in library science" (p. 297). Larsgaard believed that these librarians became caretakers who were expected to develop, describe, classify, and catalog map and geospatial collections that refused to conform to the traditional procedures in cataloging and filing for text-based books and journals, with the exception of an atlas.

Ristow (1980) suggested difficulties in processing and promoting did not lie with the maps but rather a lack of parental understanding. Larsgaard (1998) affirmed this when she described how librarians often gained the title of map librarian in the late 20th century, as “anyone who became ‘stuck with the maps’ (and it was often so expressed) either was lowest on the totem pole, or had made the mistake of not being at the meeting where the issue was decided" (p. 298). These fortuitous map librarians were tasked with caring for spatial-data collections, but likely had neither geoscience educational background nor a formal introductory course specific to map resources and services as library students.

Today, the demand is for the geo-literate librarian who would combine knowledge of basic map and spatial-data concepts with a solid background in instruction services, reference services, collection development, classification schemes, and cataloging systems. This is NeoMap Librarianship. It would include both traditional map and the new geospatial librarians who vary in the level of geo-literacy, but coexist in the 21st century. Librarians are living the global geospatial revolution as they interact with the world of geospatially enabled technologies, the Internet, and user-friendly cartography tools. As such, in spite of some librarians lacking formal background in geography and cartography, these NeoMap Librarians may be proficient using web-mapping tools, open-source data, and GIS technologies. Virtual globe, map, satellite imagery, and aerial photography are being heralded as poster children of Web 2.0 by Patrick McGlamery, a seasoned academic map librarian, who used Google Map and Google Earth as examples (as cited in Abresch, Hanson, Heron, & Reehling, 2008, p. ix). It is the NeoMap Librarian who may turn map resources from problem children to valued resource collections.

NeoMap Librarianship is defined in part through job advertisements. Job descriptions can be specific to map cataloging or acquisitions specialist for Sanborn Fire Insurance maps. However, other job announcements call for a geospatial librarian, listing qualifications such as a graduate degree in a geoscience-related discipline and academic background plus demonstrated abilities in GIS. These qualifications are in addition to or in lieu of the Master in Library Science (MLS) from an American Library Association or ALA-accredited LIS degree program.

Prior to 1945, approximately 30 libraries had full-time map librarians (Hanson & Heron, 2008, p. 96). Today, the Map and Geospatial Information Round Table (MAGIRT), a professional map librarian organization under the ALA has nearly 300 members as of Dec. 2014 (MAGIRT, 1996–2016; J. Clemons, personal communication, Feb. 26, 2015). In 2008, the first technical textbook devoted to integrating GIS into academic library services was written by Abresch et al. (2008), all of whom are librarians with geography and cataloging specialty backgrounds. Like-minded, Eva Dodsworth (2012) believed that library professionals should upgrade geo-literacy skills; she wrote the first book to teach GIS and mapping skills to non-GIS librarians. She described her book as a “training package for all library staff interested in gaining the most up-to-date and relevant mapping skills” (Dodsworth, 2012, p. xi).

This book strives to provide a pragmatic guide written for the community of LIS students and working librarians who want to reach a higher level of geo-literacy. This book may inform the community of geography and geospatial savvy graduates to better understand how their knowledge could be enhanced with library skills to meet the job description expectations for working in libraries. As NeoGeography and NeoCartography have become commonplace, it is time library school programs support NeoMap Librarianship and join the Geospatial Revolution.

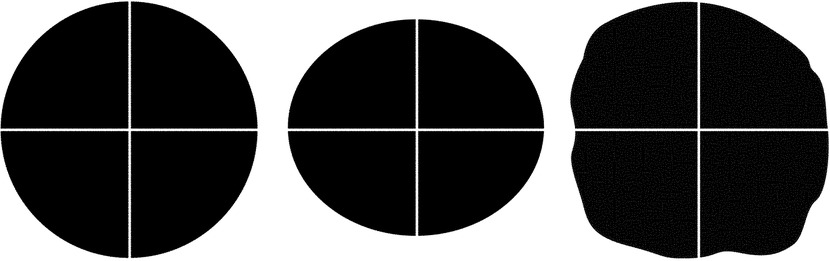

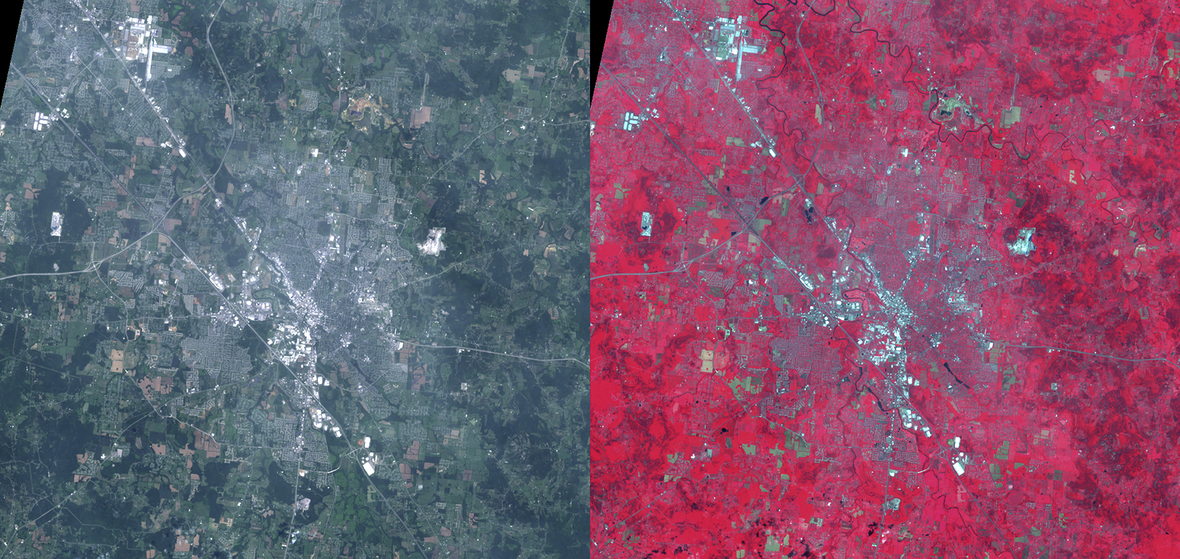

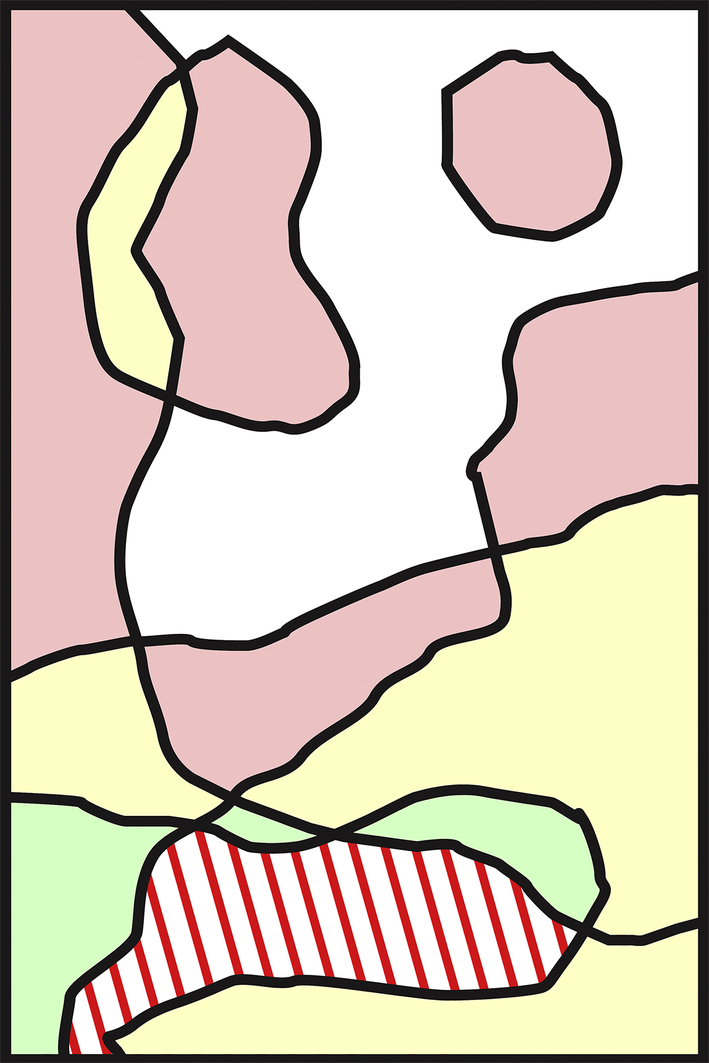

Spatial thinking is a type of reasoning or literacy that can be used for navigating the world. In this context, it is referred to as geospatial thinking or geo-literacy. Maps are the graphical tools that convey this location-based information and geo-literacy, an essential concept for interpreting and using maps. Being geo-literate goes beyond traversing points A to B, and cartographers create many different map types that broadly fall into two categories of reference or thematic maps. Reference maps show where things are and thematic maps communicate a specific message about the world. Some of the mapping techniques and map types that librarians will encounter are defined and illustrated in this chapter.

Spatial thinking; Geo-literacy; Geospatial; Thematic maps; Reference maps; Choropleth; Cartogram; Terrain; Mapping data; Aeronautical charts; Cartogram; Raised relief model; Atlas; Gazetteer; Geologic maps; Historic maps; Physiographic maps; Topographic map; Planimetric; Globe.

What does it mean to think spatially? Our days are filled with thoughts in a variety of domains, some focused on using numbers, some with words, and others with music or the visual arts. But we also think spatially every day. The National Research Council (2006) describes spatial thinking as a way that “…uses representations to help us remember, understand, reason, and communicate about the properties of and relationships between objects represented in space, whether or not those objects themselves are inherently spatial.” [Emphasis preserved] (p. 27). These skills include “concepts of space, tools of representation, and processes of reasoning” (p. 12). Concepts of space are the components that separate spatial thinking from other domains such as mathematic or language-focused reasoning skills. Obviously, spatial thinking plays a role in our navigational activities, but in reality it goes much further as many of our other modes of thinking are influenced by spatial elements. For example, driving to work is clearly related to thinking spatially, but so is interpreting a spreadsheet on a computer. Working on mechanical problems, organizing your desk, and moving through the menu of a computer program are all tasks that require the ability to think spatially. It is an important skill in our lives, and one that directly concerns the field of geography.

What about geo-literacy then? We know what literacy is in the context of the written or spoken word, but what does it mean in the context of spatial thinking? Certainly there is an element of knowing where things are, but geography involves so much more than memorizing state capitals. The term geo-literacy is used by the National Geographic Society to “describe the level of geo-education that we believe all members of 21st-century society will need to live well and behave responsibly in our interconnected world” (Edelson, 2014). It is broken down into three separate components, starting with interaction or “how our world works.” This component relates to modern science’s descriptions of the functioning of natural and human systems. Secondly, implications or “how our world is connected” deals with the myriad links between these systems and how they affect one another. Finally, “how to make well-reasoned decisions” describes a process of decision-making that factors in these systems and their connections to make intelligent choices that benefit humanity while minimizing the potential negative impacts of the decision.

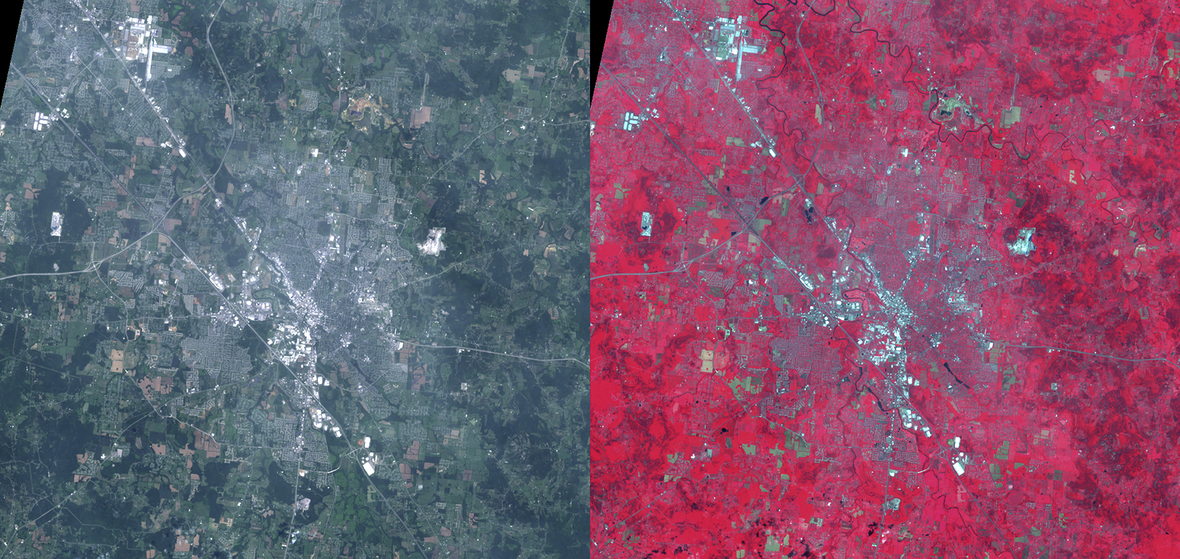

In today’s world, being geo-literate and having the ability to think geospatially has become more crucial than ever before. The level of understanding regarding our impact on the natural world is much greater than in decades past, and leveraging geo-literacy is essential to effective decision-making. This will help to improve the quality of lives around the world while reducing waste and protecting environmental conditions. Fortunately, geography is well-suited to help in this regard. With geography’s holistic approach to study, it projects a big-picture view of the interconnected nature of the world. Tools such as GIS, remote sensing, and maps are core components of how librarians can instruct and empower geo-literacy to these ends.

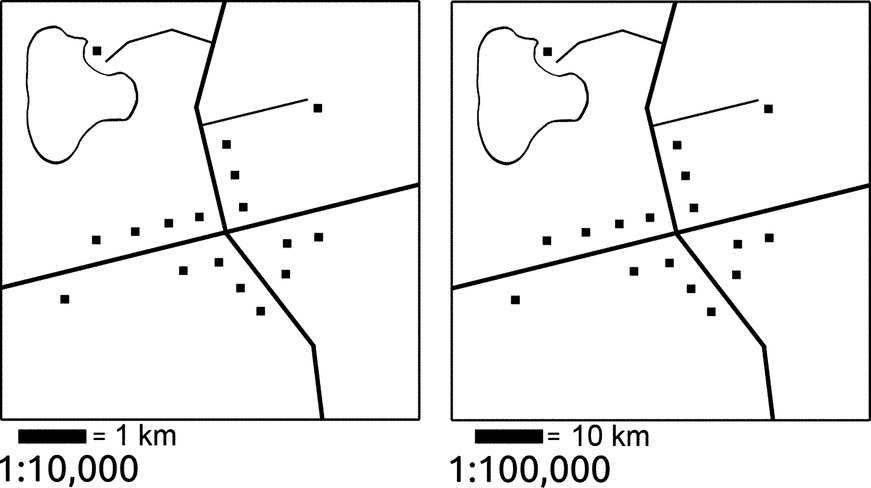

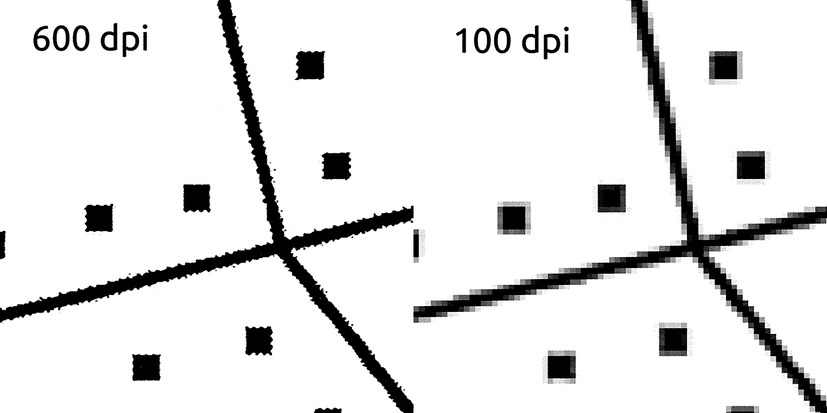

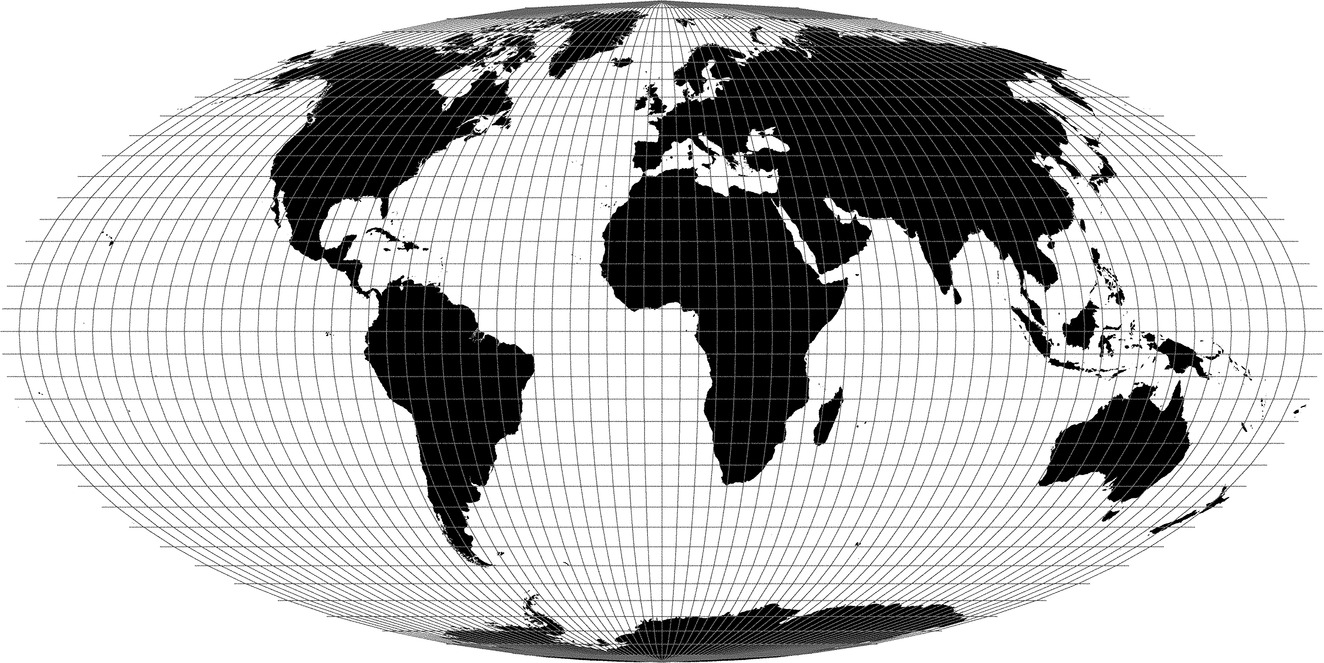

Maps are graphical tools for conveying spatial knowledge. They are a cartographer’s attempt to communicate information about the geographic milieu to an audience (Robinson & Petchenik, 1975). In this way maps provide consistency to our world view, attempting to unify our vision of the spatial configuration of features. A broad definition of the map is that they are graphical scale models of spatial concepts (Merriam, 1996). These concepts might represent physical or cultural features, or they might be abstractions that have no physical presence (Dent, Hodler, & Torguson, 2009). The format may be physical or virtual such as a paper road map vs. a digital GPS unit. Regardless, by connecting data to locations, we can communicate information about spatial patterns, track changes on the landscape, and even predict the outcomes of our decisions.

Colloquially, the term map can be used to describe many different objects, but traditional maps are required to include a few elements to differentiate them from figures, diagrams, or drawings. Different sources discussing cartography will disagree as to what specifically is required to make a complete map, but the most essential are a notation of scale, an indication of the direction of north, a legend, and citation information. If someone were to draw a map of their neighborhood, it would probably lack these elements, but it would still be acceptable to refer to it as a mental map, or just a map. Other map-like information lacking these essential components might be better described as figures or diagrams, but keep in mind that not all maps will fit the popular conception of what a map looks like.

Some maps, such as atlases or road maps, can be described as reference maps. These are general maps concerned with describing a broad overview of the location of features on Earth. While all maps are concerned with the spatial layout of phenomena, many maps fall into a different category, known as thematic maps. These maps explore specific topics or themes of data. Reference maps exist to tell us where things are, while thematic maps exist to communicate a specific message about the world. Thematic maps use general reference information to frame their messages, but only inasmuch as it is useful for putting thematic information in its appropriate context. For example, a map showing population density per county in the state of Tennessee will include county boundaries, but likely will not show every city, waterway, and road in the state. An overload of information can make things visually confusing, potentially to the point of obscuring the intended message. Therefore, on a thematic map, information not directly related to the message is generally not included.

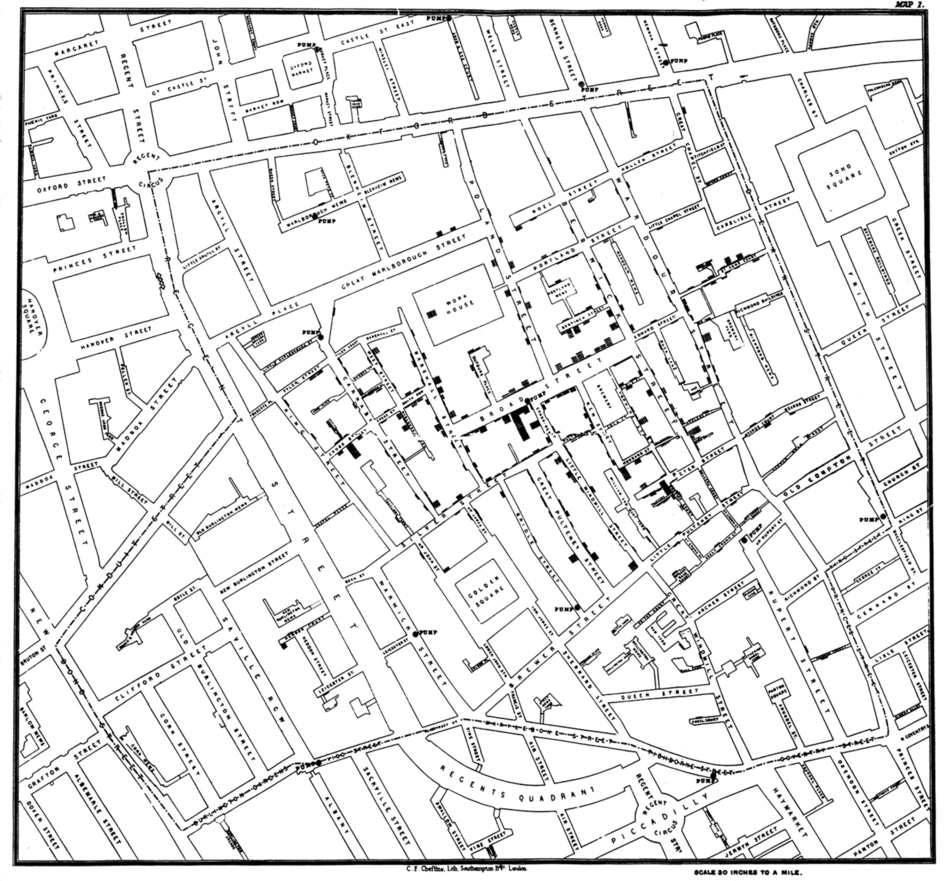

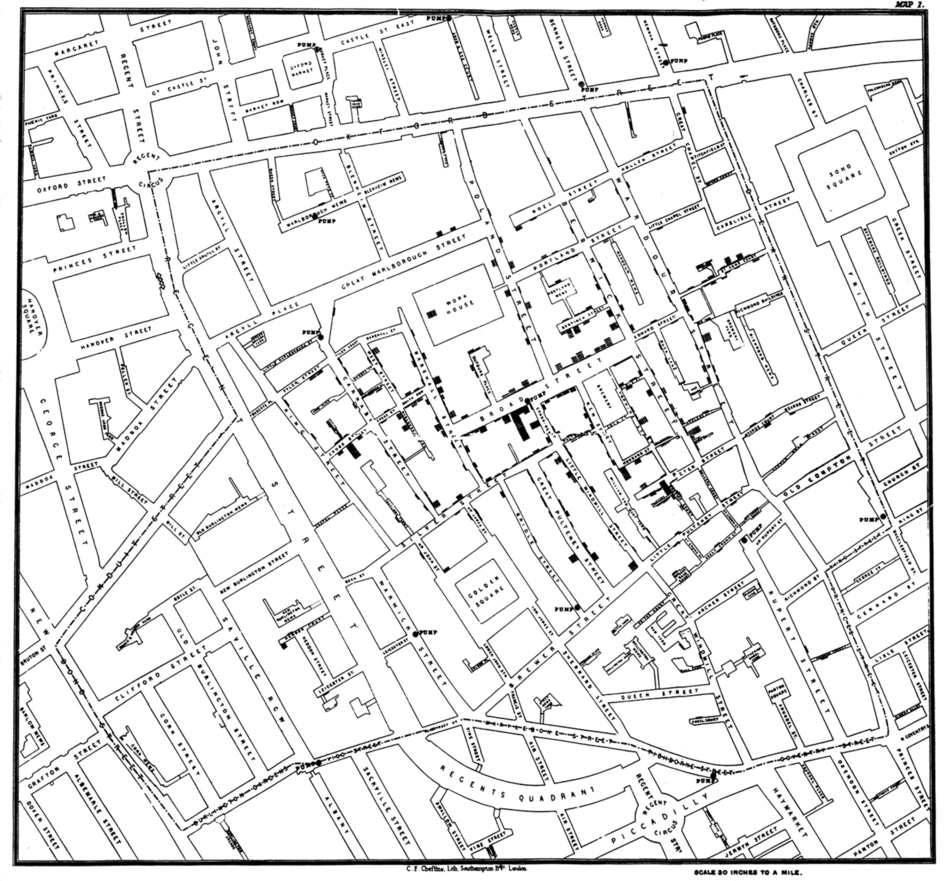

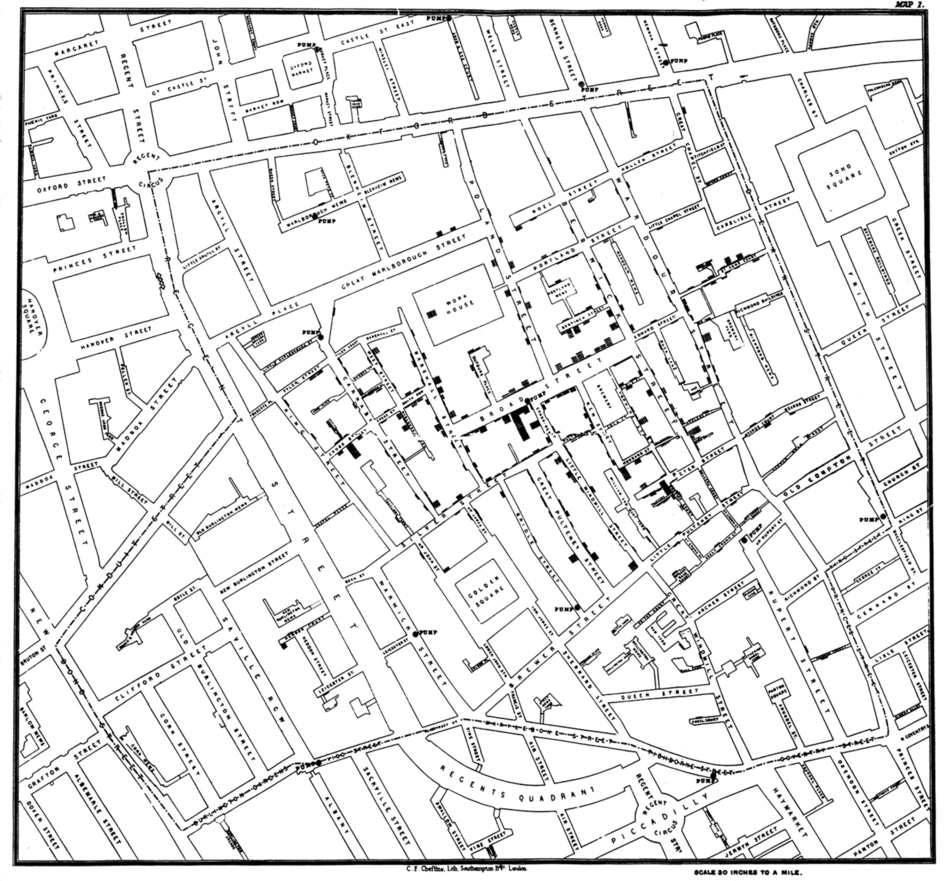

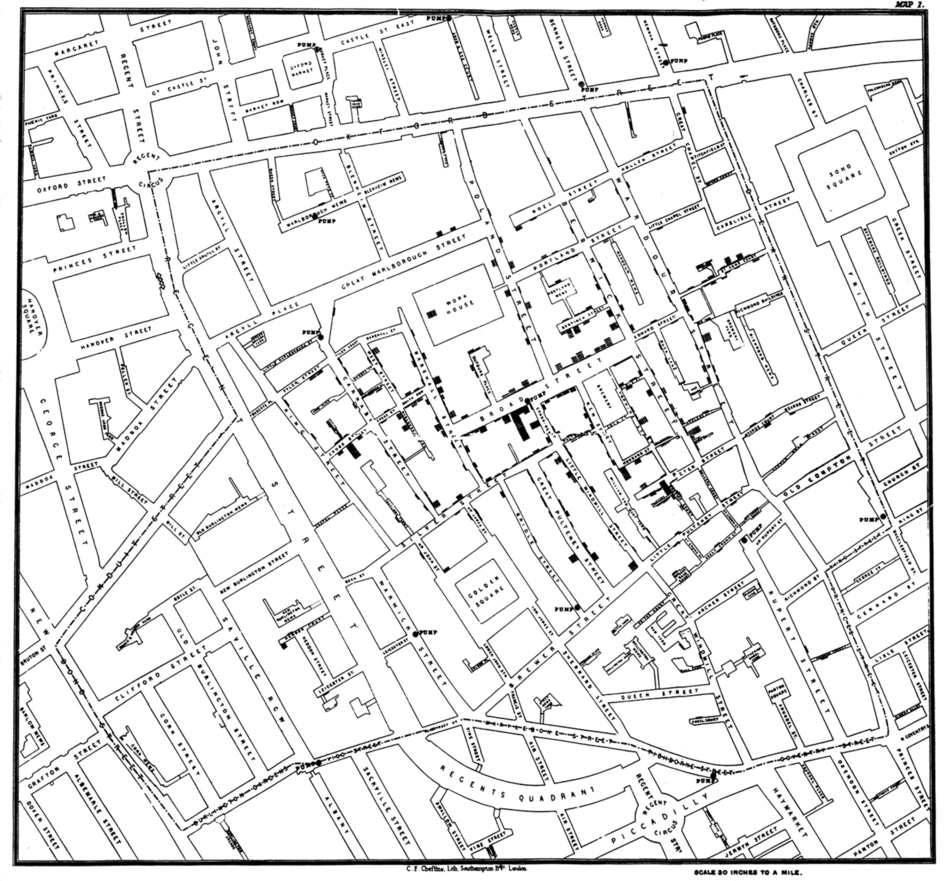

One of the most famous examples of a thematic map is the cholera map based on John Snow’s research during an 1854 outbreak in London, see Fig. 2.1. Snow was convinced that contaminated water was the vector by which the disease was being spread, and his geographic analysis is credited with helping to end the outbreak, as well as giving rise to the field of epidemiology (Vinten-Johansen, 2003). While the map in Fig. 2.1 uses general reference information in the form of London streets, the primary purpose is to present medical data in support of the contaminated water theory. Many thematic maps follow this approach, and can be considered tools for answering questions about the nature of the world. A more modern example could be a thematic map exploring poverty rates at the county level in the United States. This map would not only answer questions such as “where does poverty exist?,” but would also act as a tool for confronting the issue. Just as Snow’s cholera map indicated a public well to be the source of the outbreak, analyzing patterns of poverty could help to better understand how spatial factors may play into poverty and how we might confront the issue in an effective manner.

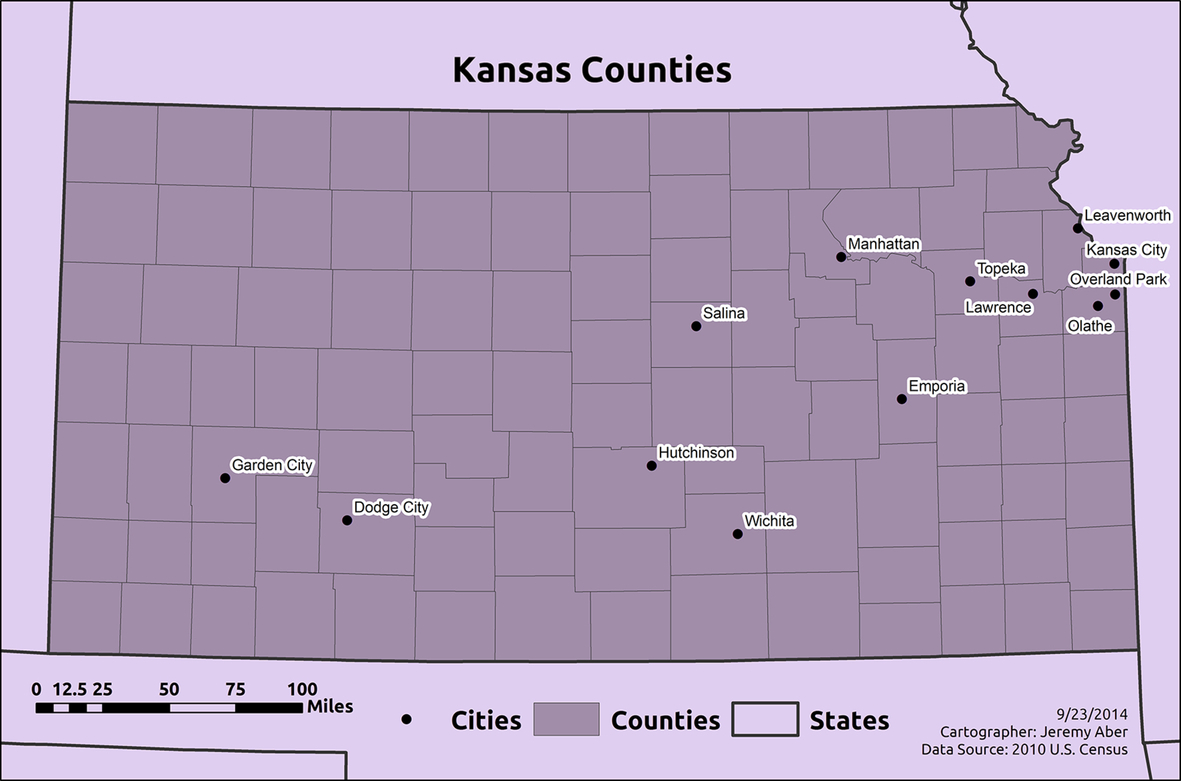

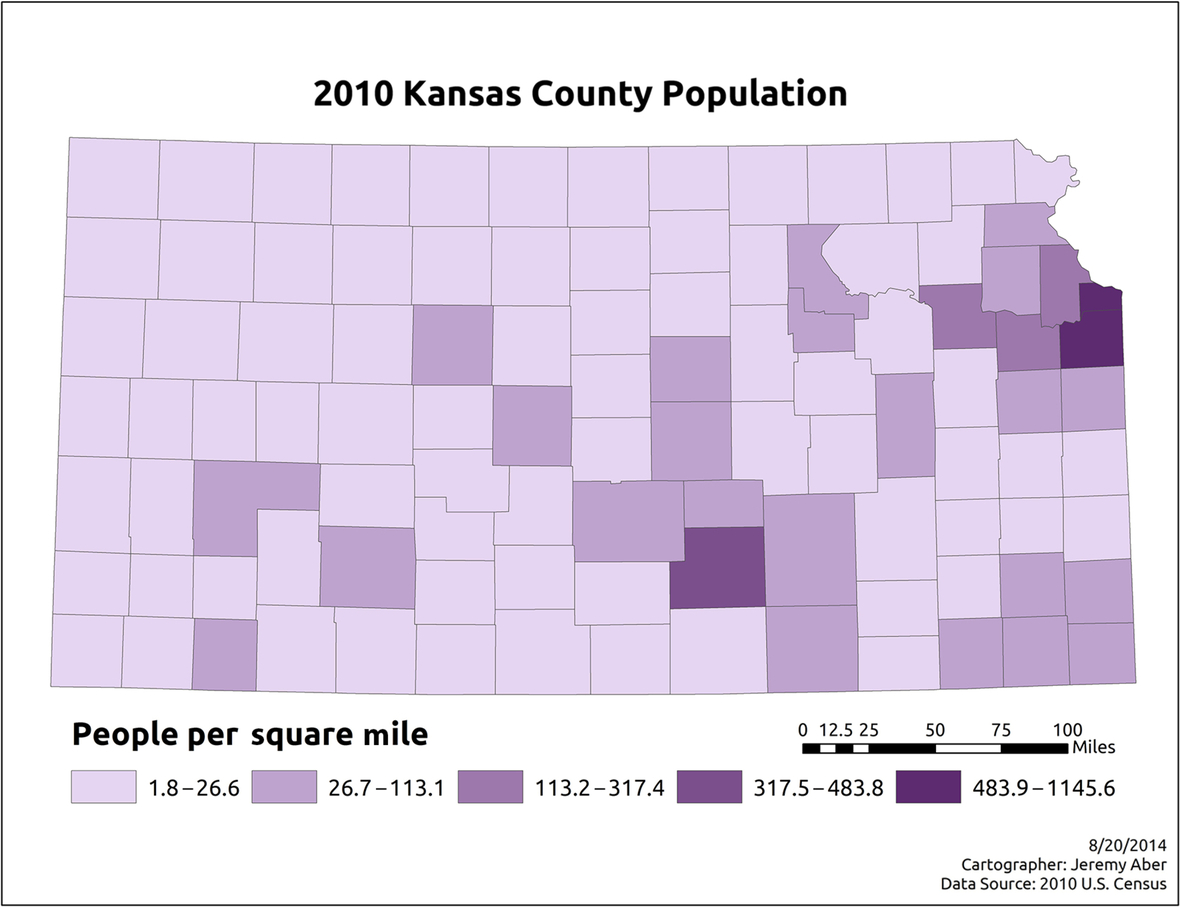

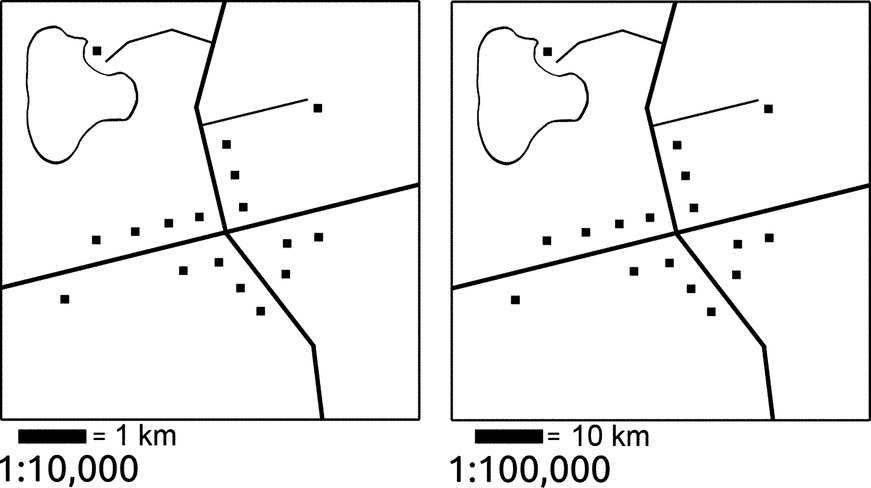

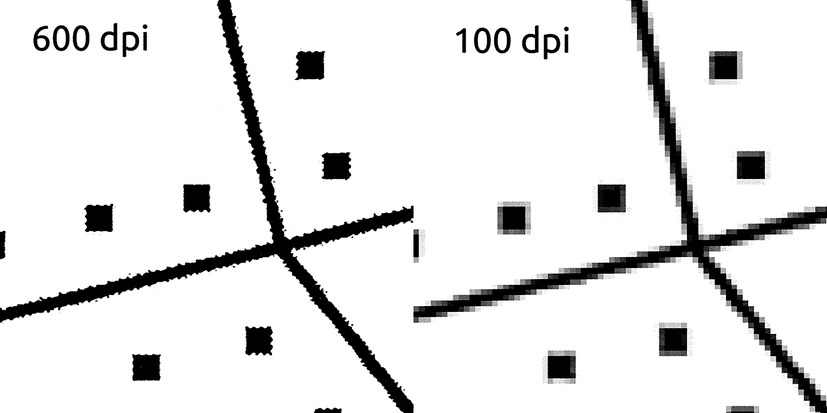

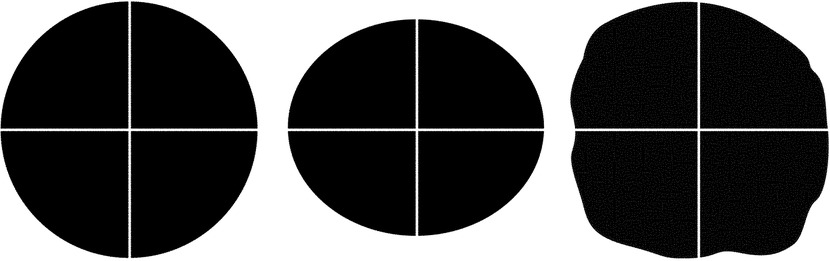

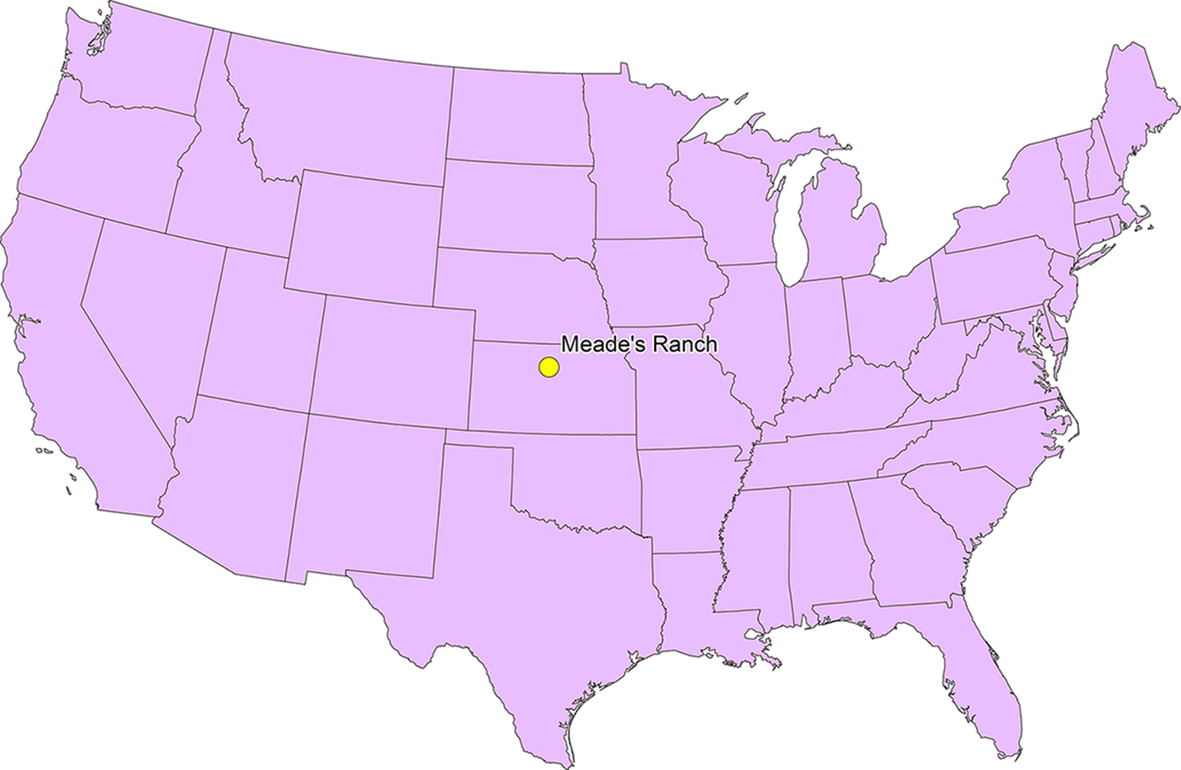

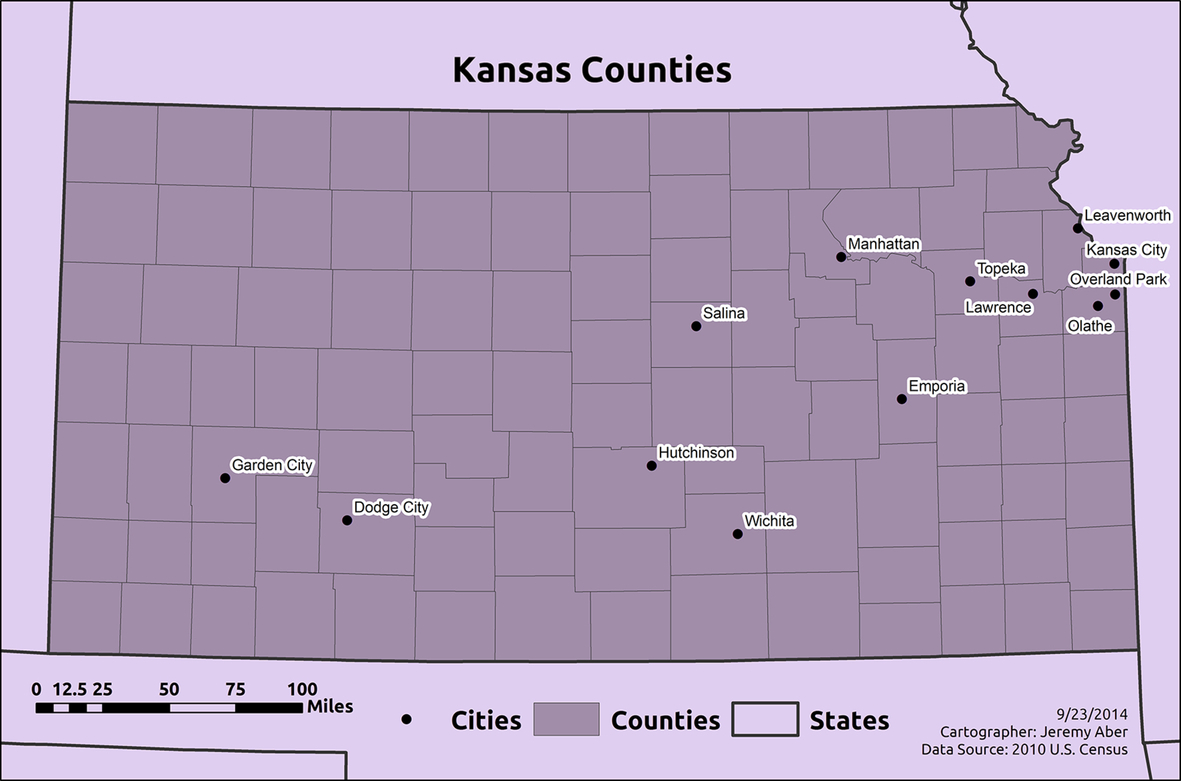

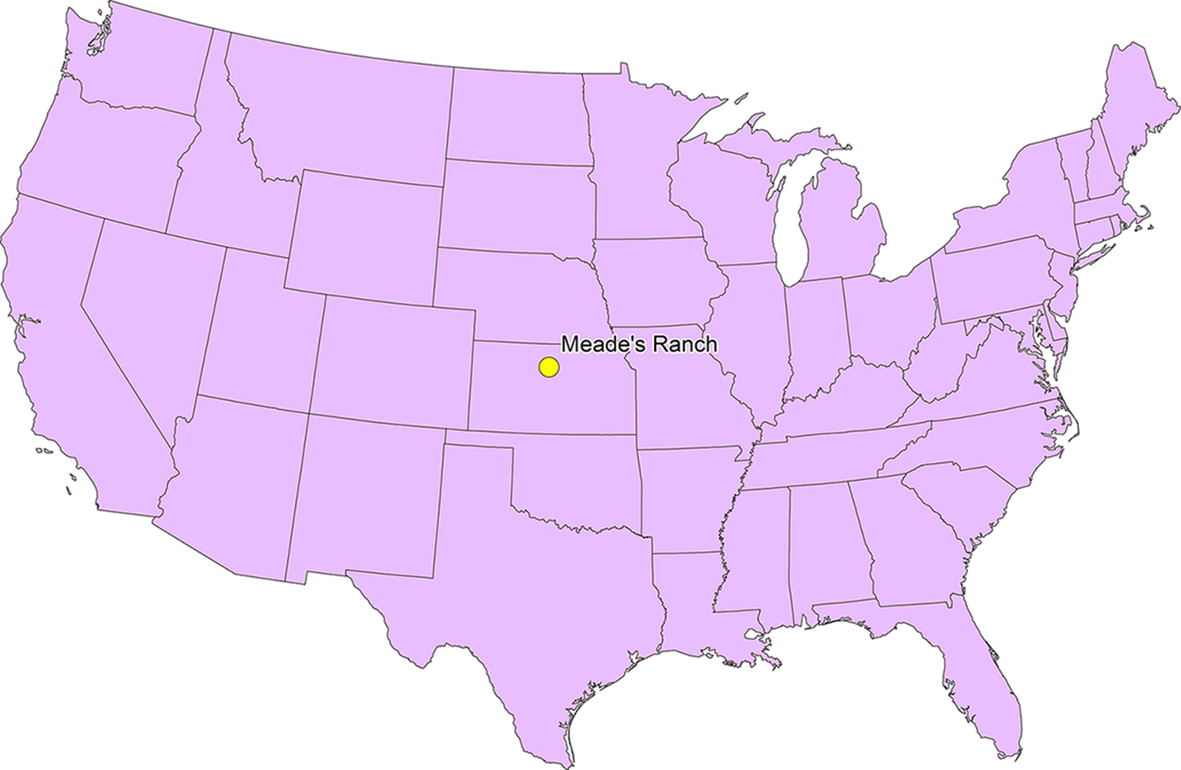

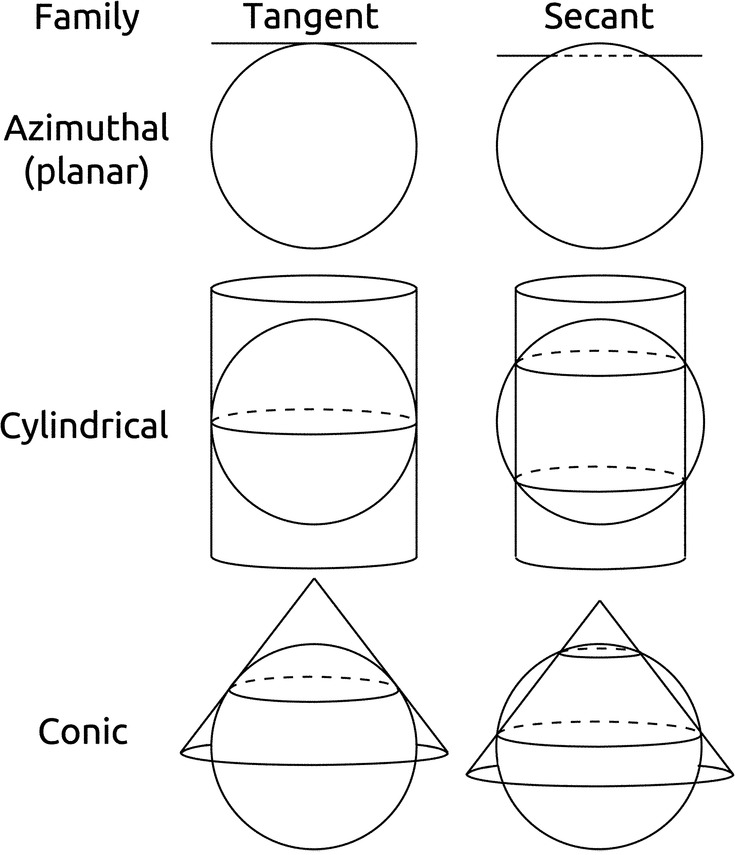

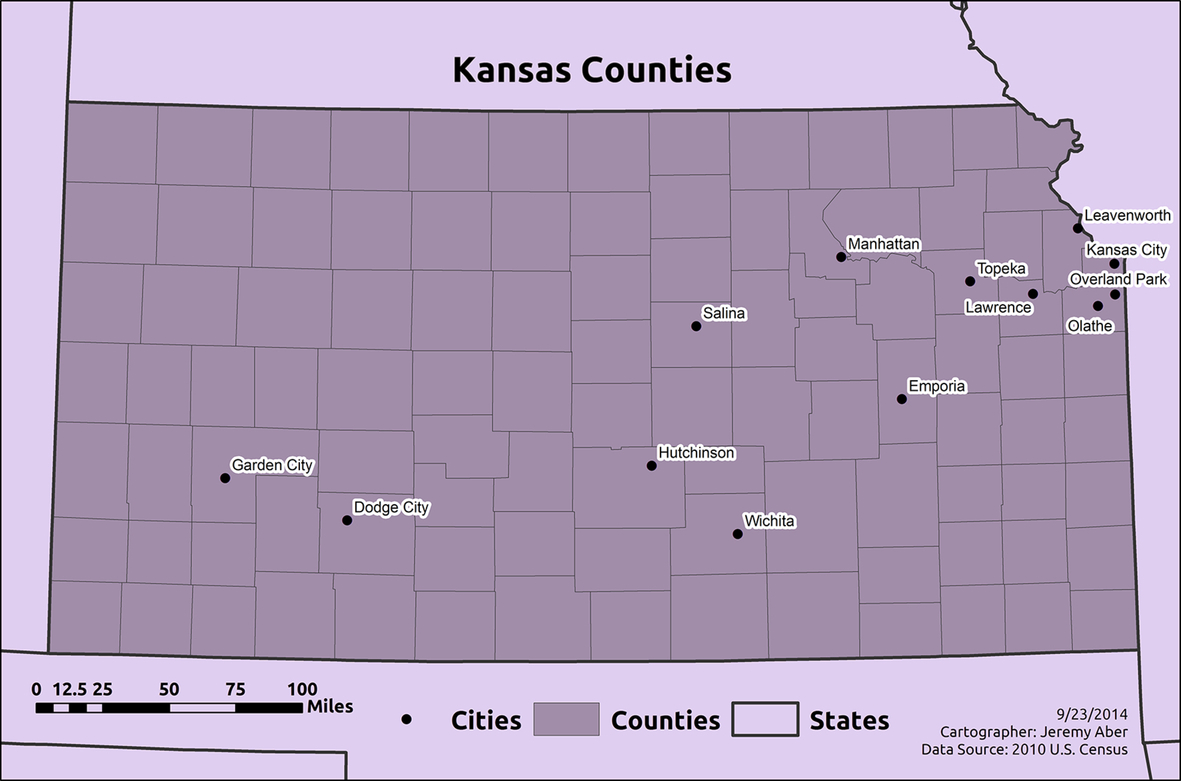

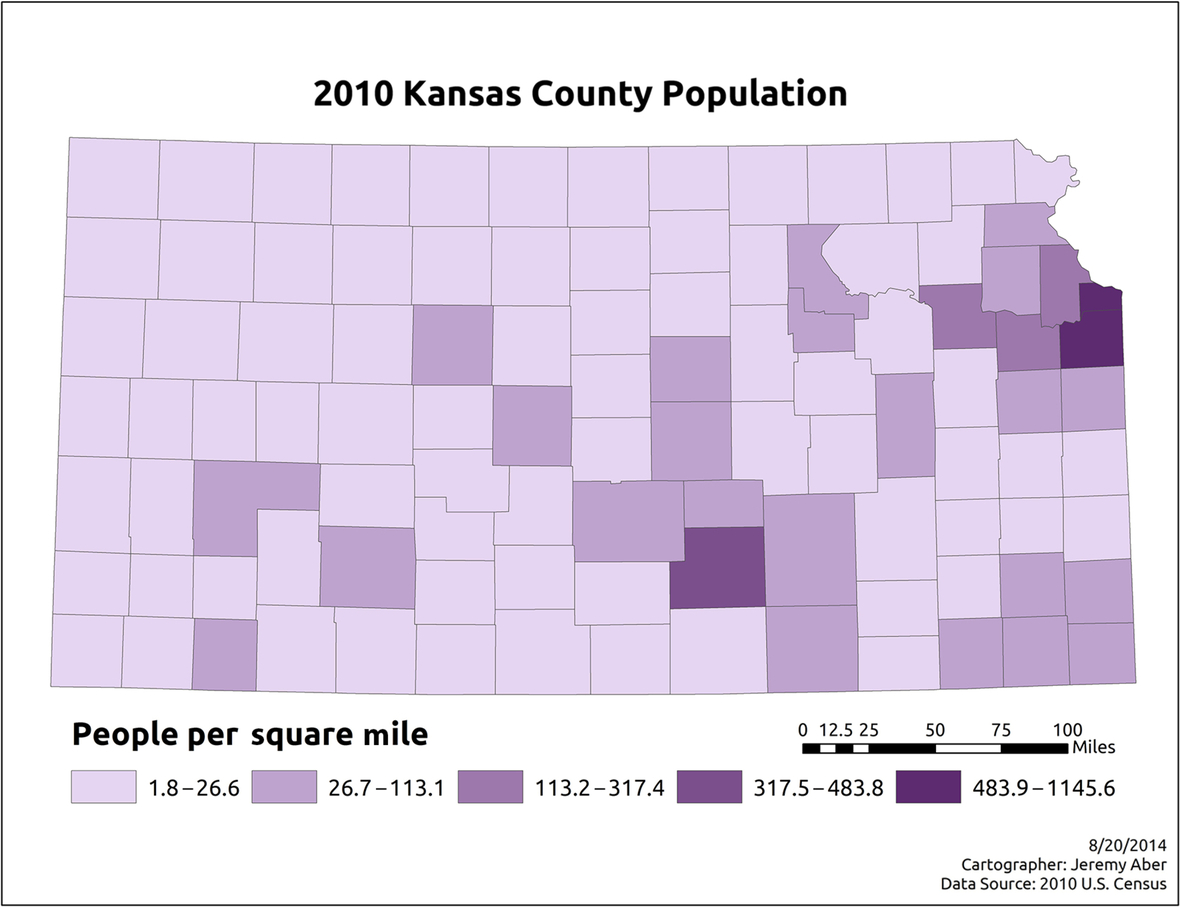

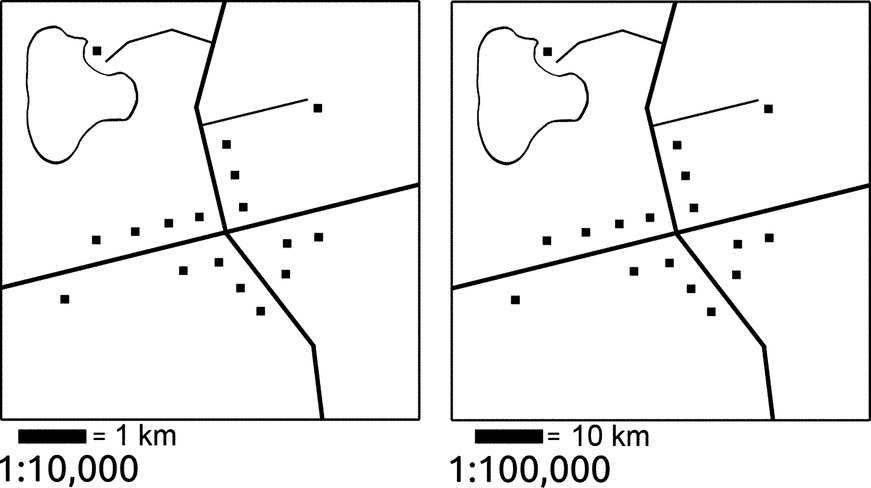

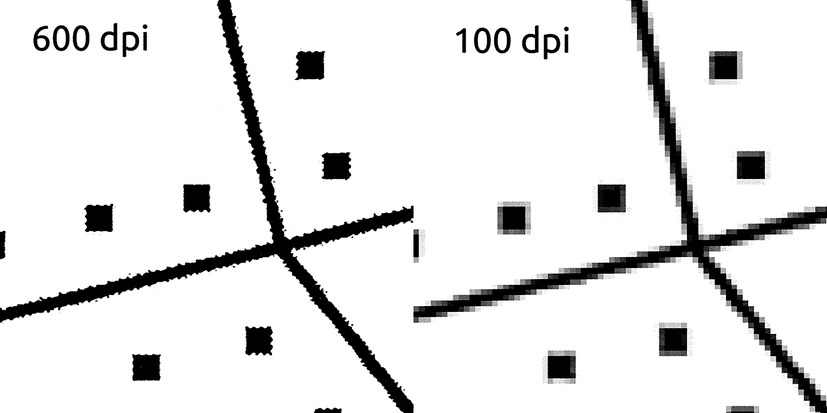

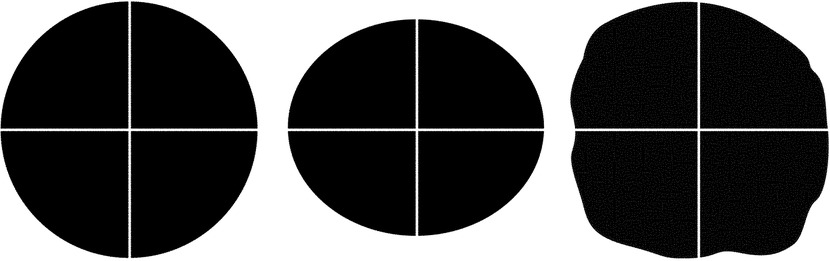

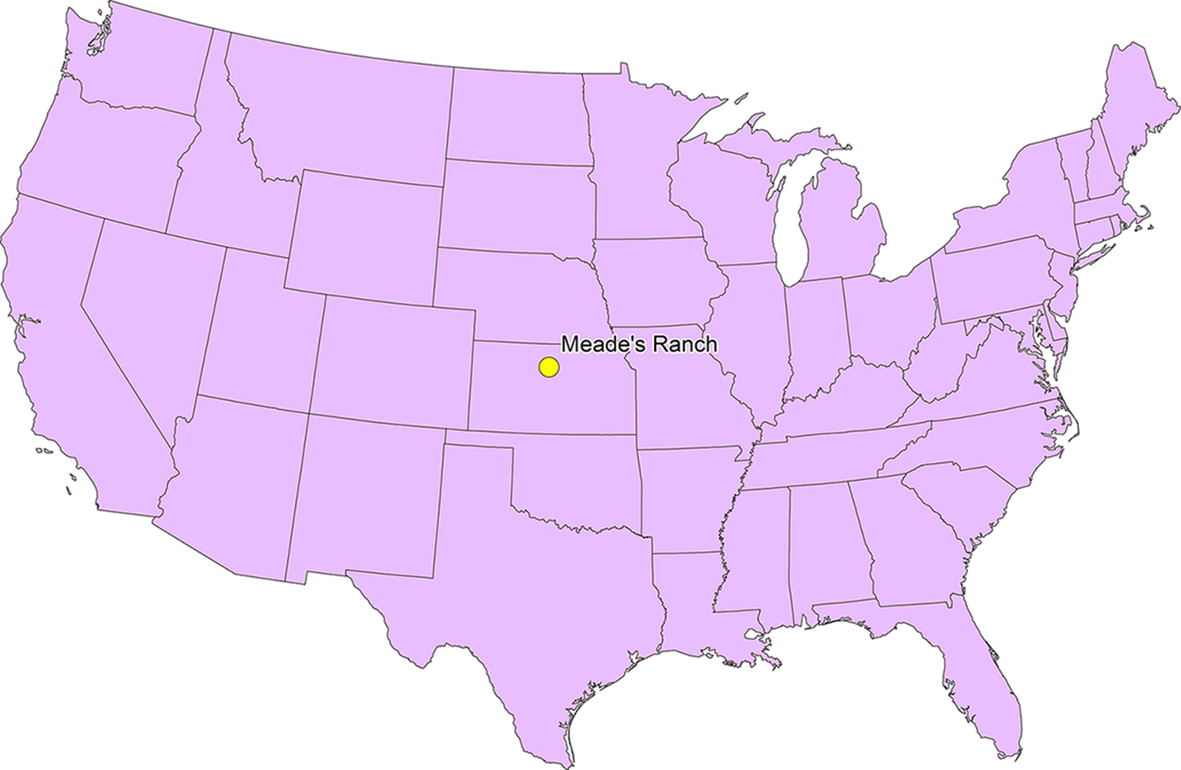

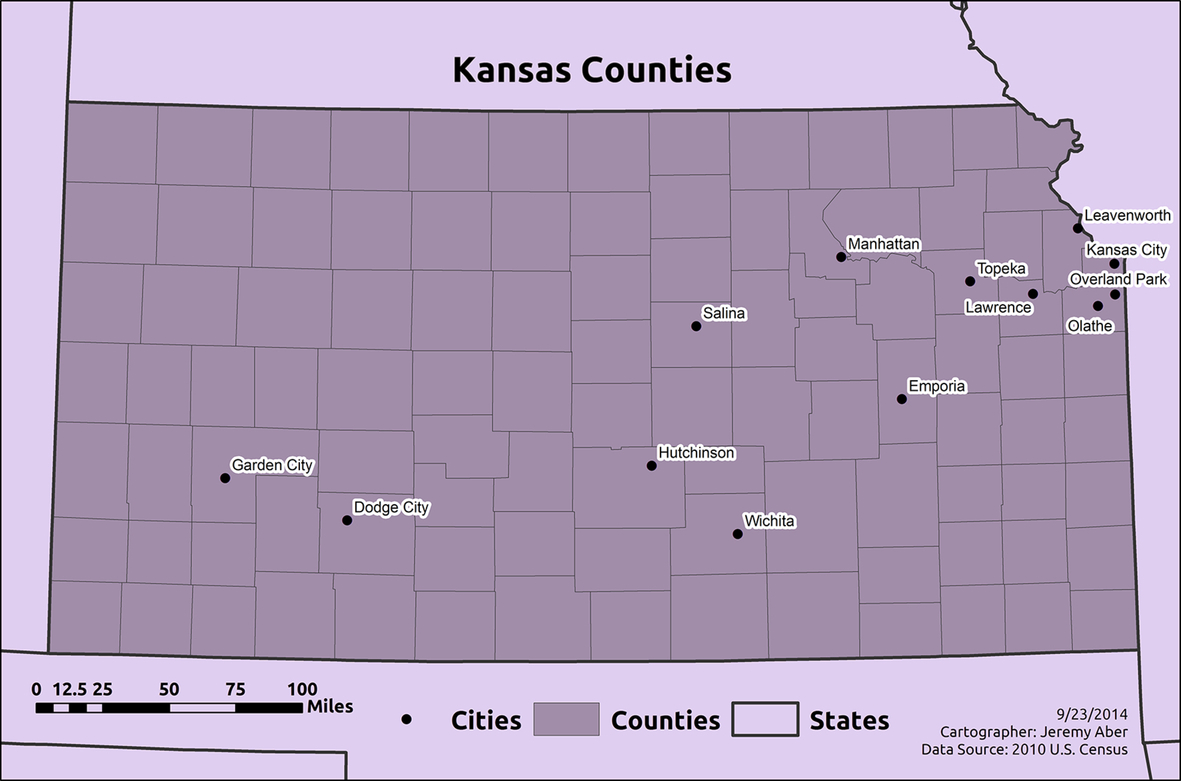

Cartography has developed many approaches to visually representing spatial information over the past few thousand years. Both reference and thematic maps use various techniques for presenting spatial information, although thematic maps often use visualization techniques that deviate from a typical reference map. Some of the more commonly used thematic mapping techniques are described here. In order to explore these visualization approaches, the 2010 U.S. Census Bureau’s county population figures for the state of Kansas are employed. By using the same data in each map, the different symbology techniques can be more easily compared to one another. Fig. 2.2 shows a reference presentation of the state, with counties and major cities represented, but without any population data included. While visualization techniques are discussed here, a more detailed look at cartography and map conventions can be found in Chapter 3.

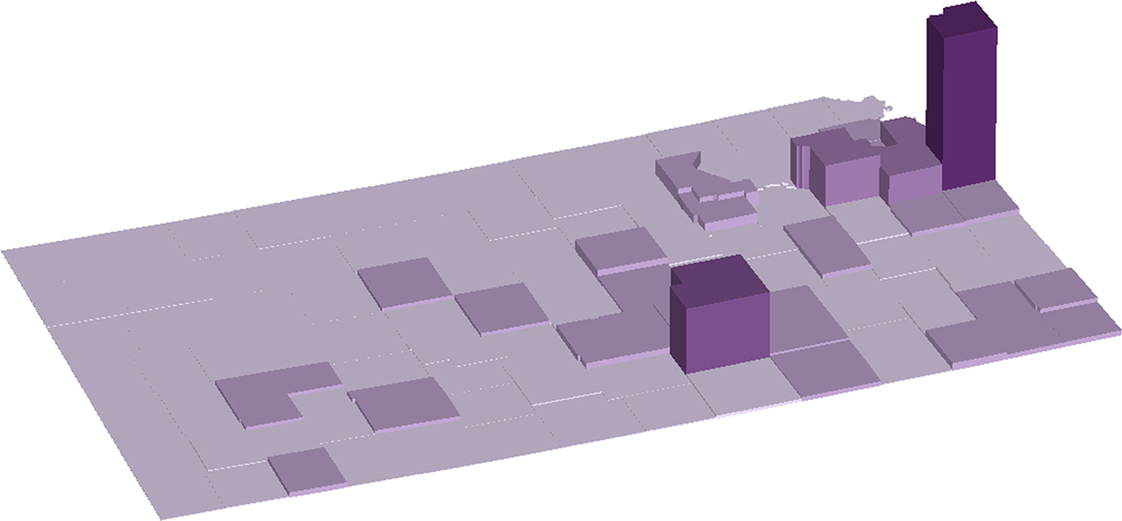

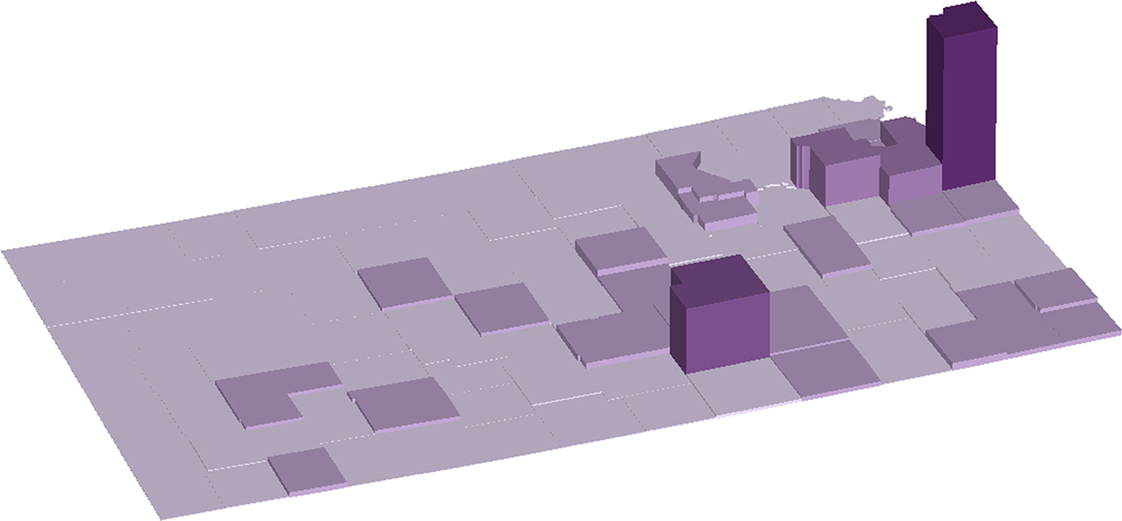

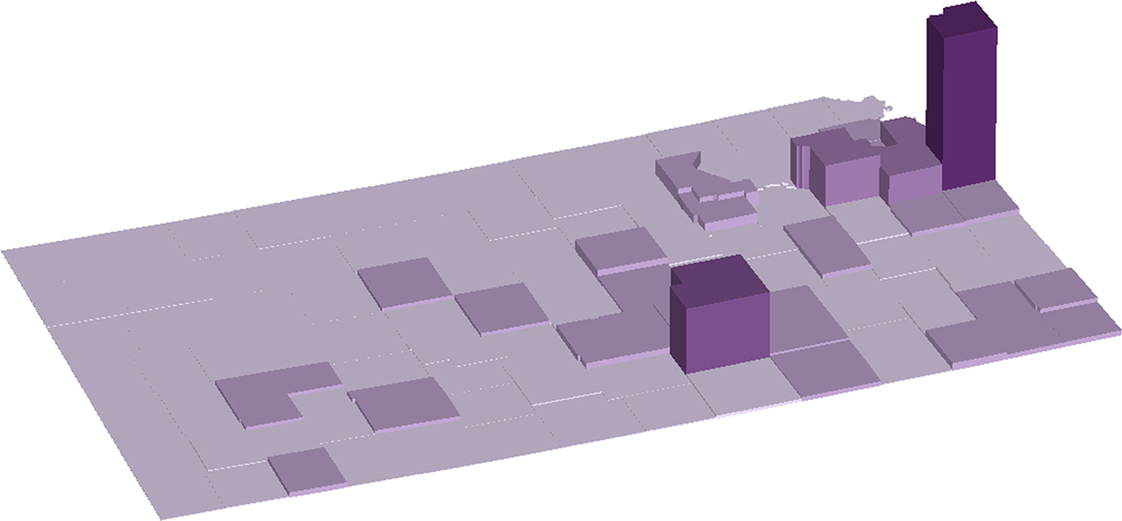

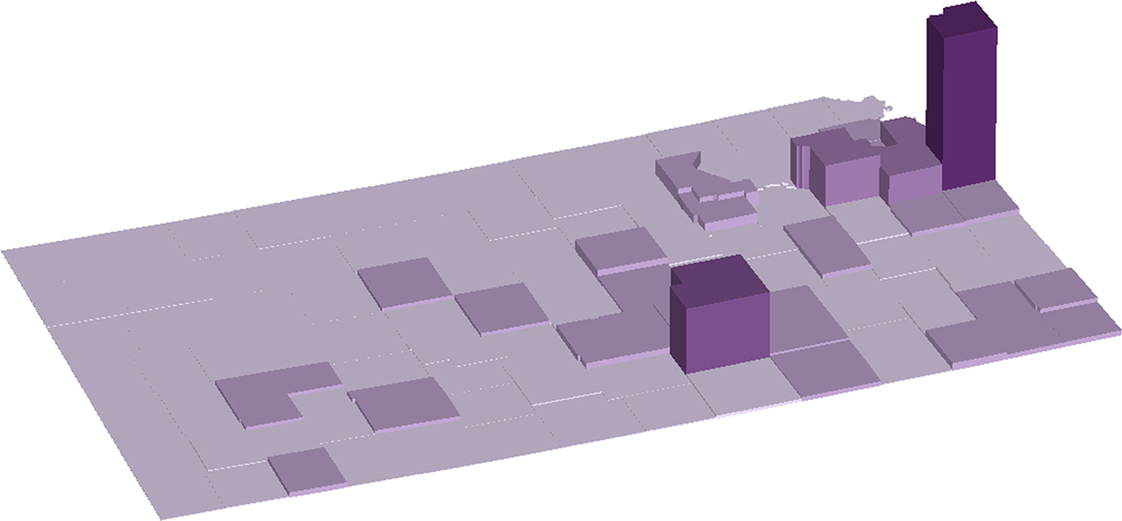

The name “choropleth” may sound intimidating, but it is a commonly used approach to representing spatial data that is intuitive for map readers. Other names for choropleth include shaded maps or enumeration maps. A choropleth symbology is a two-dimensional (2D) representation of a three-dimensional (3D) histogram, or statistical surface, of data. Imagine that our county boundaries are represented in two dimensions, while the height of each feature represents the number of people found in each county. Fig. 2.3 shows an example of this 3D data visualization. Note that while this may be a visually interesting image, it is somewhat difficult to interpret, as county boundaries are not always visible and high value counties obscure information behind them.

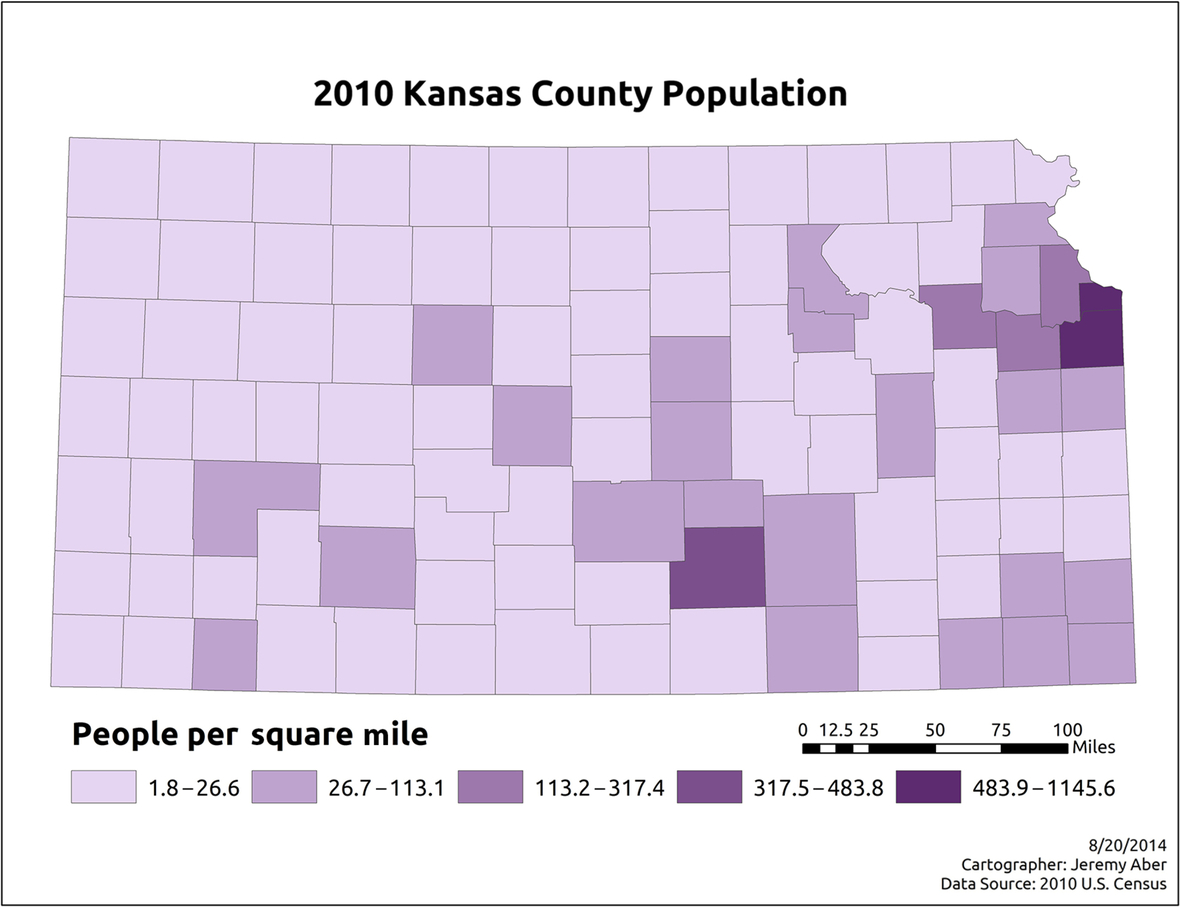

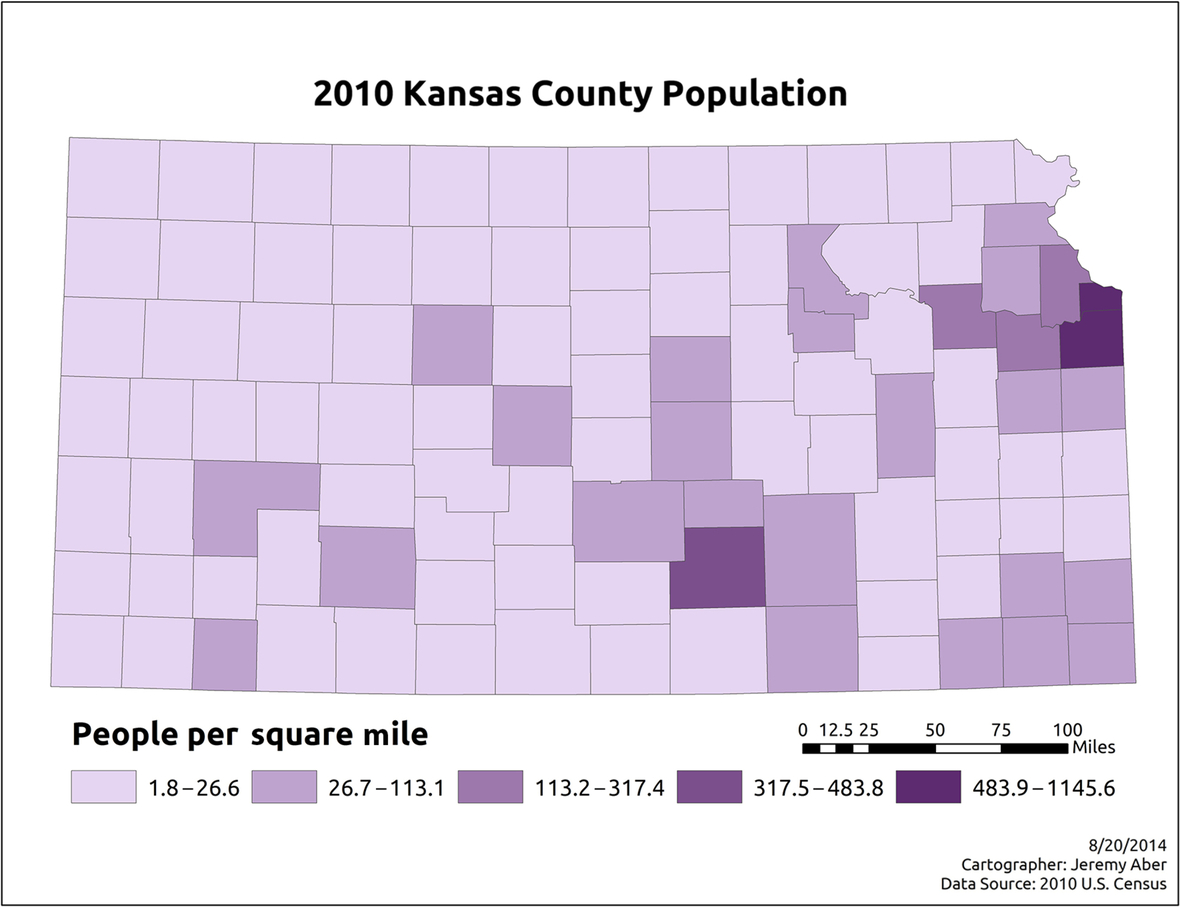

Fig. 2.4 shows a traditional choropleth symbology, with county populations broken down into five classes. In this case, a natural breaks approach has been used to generate the class breaks. While the classes still obscure some variability in the data, the patterns in population distribution are easier to read in this view. Choropleth symbology is popular for many thematic maps, as it is easy to interpret, can quickly expose spatial patterns in data, and is visually appealing. One word of note regarding choropleth symbology though, the data represented must always be a derived value, such as the people per square mile ratio in Fig. 2.4. Using an absolute values approach can give outlier values much more influence on the visual result and therefore a faulty impression of the actual data. For a longer description of the many ways in which data and map symbology can be manipulated, accidentally or intentionally, see Mark Monmonier’s excellent How to lie with maps (1996).

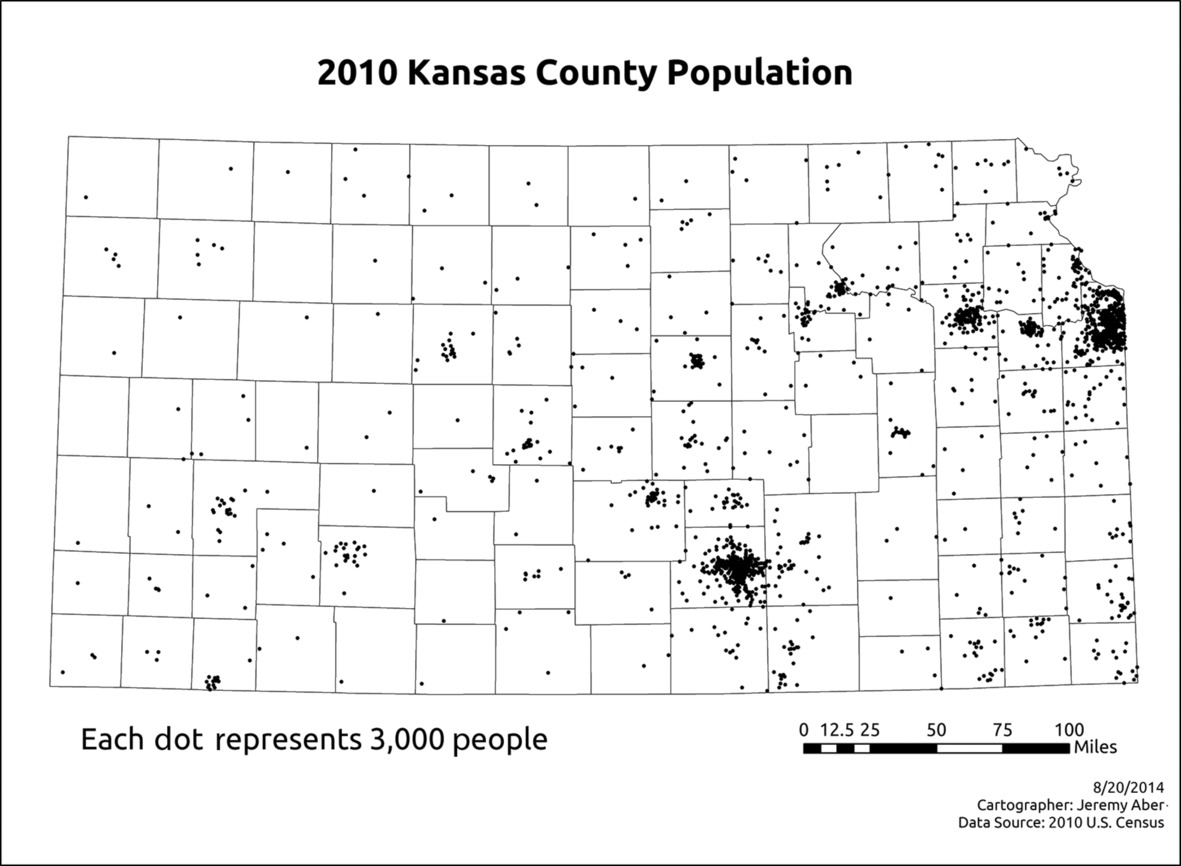

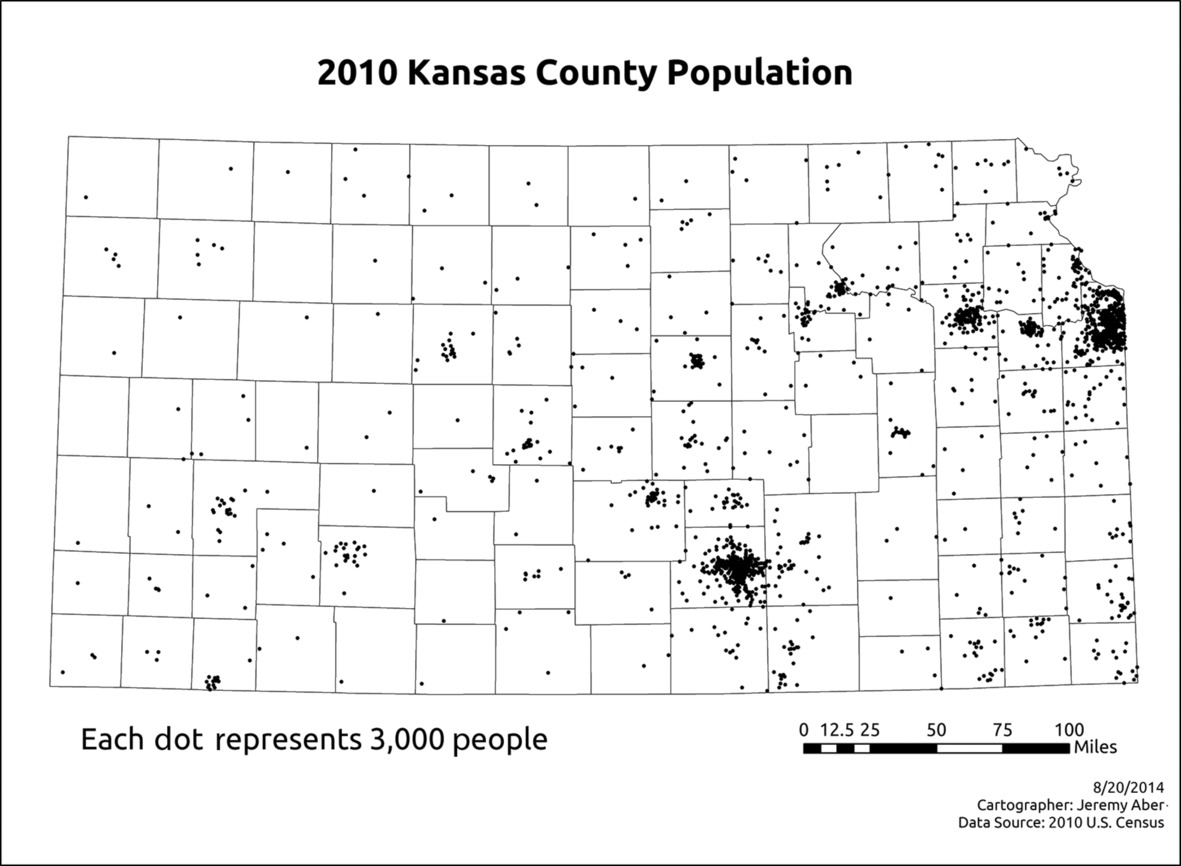

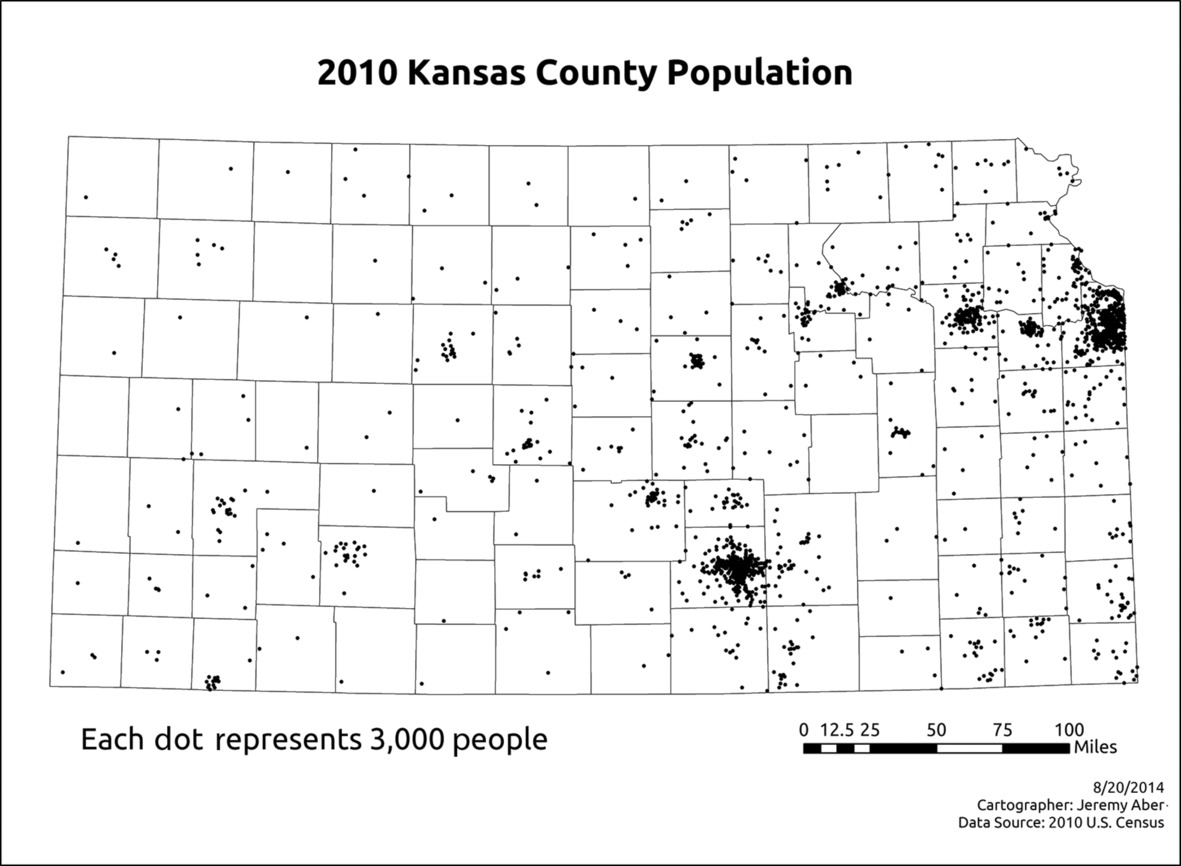

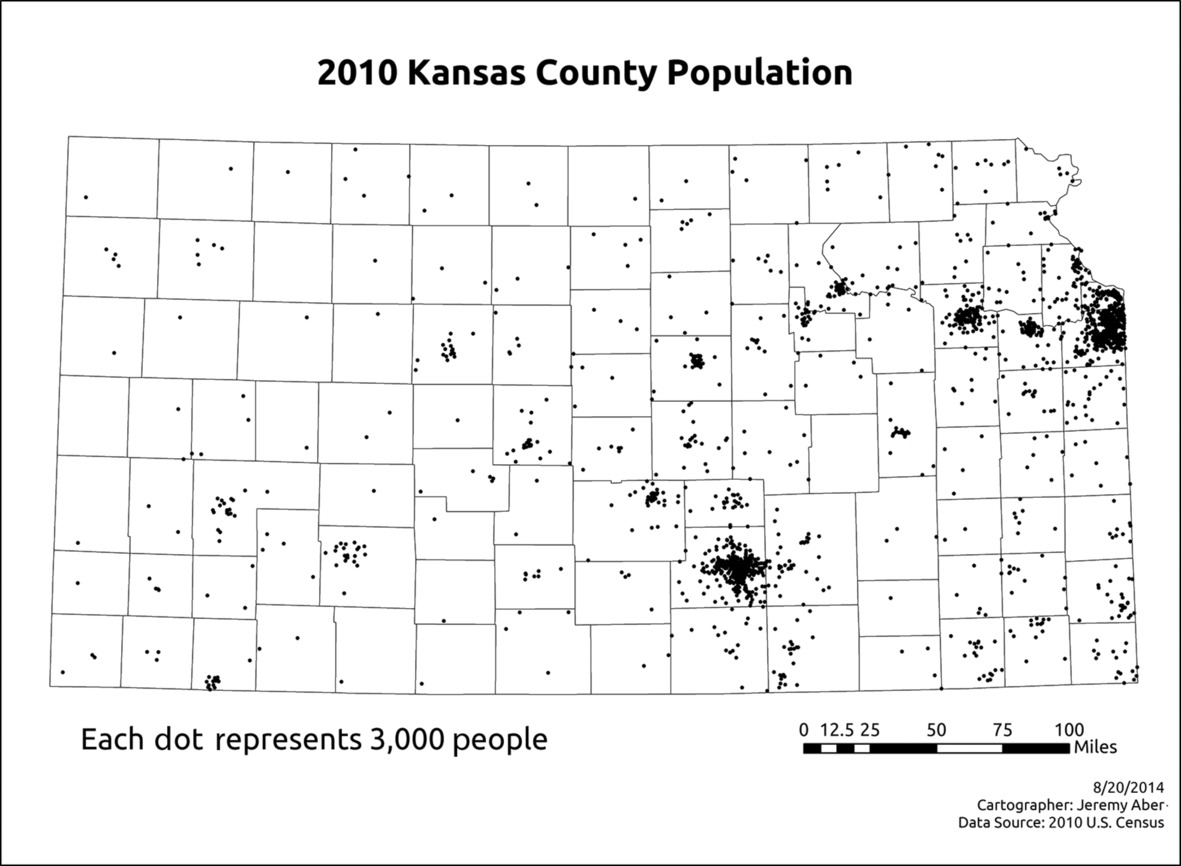

Another common map symbology approach is the dot density map. Instead of using colors to represent different classes of data, the dot density map simply puts a dot on the page for each unit of value. This has the benefit of not obscuring data points quite as much as the classes in a choropleth symbology, but it can also be misleading. The visual size of the dots is a major concern, as overlapping dots can coalesce into unreadable blobs. This is oftentimes unavoidable, but does decrease the map’s readability. Dot placement is also important. In an ideal dot density map, each dot would be positioned directly over the location of the feature represented, but this is typically not possible. In the example found in Fig. 2.5, U.S. Census blocks were used to give a relatively accurate approximate dot location, but the dots may not accurately represent the location of populations, especially in some of the more sparsely populated counties.

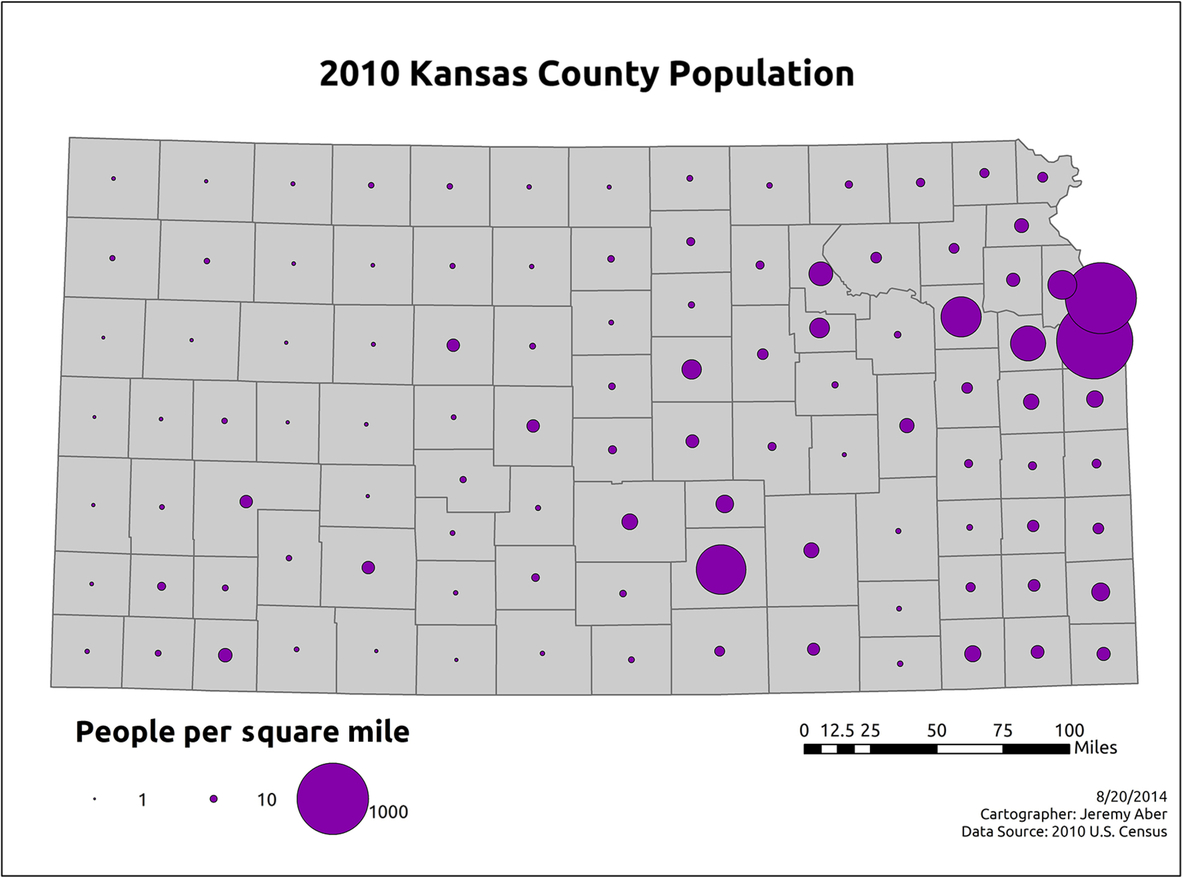

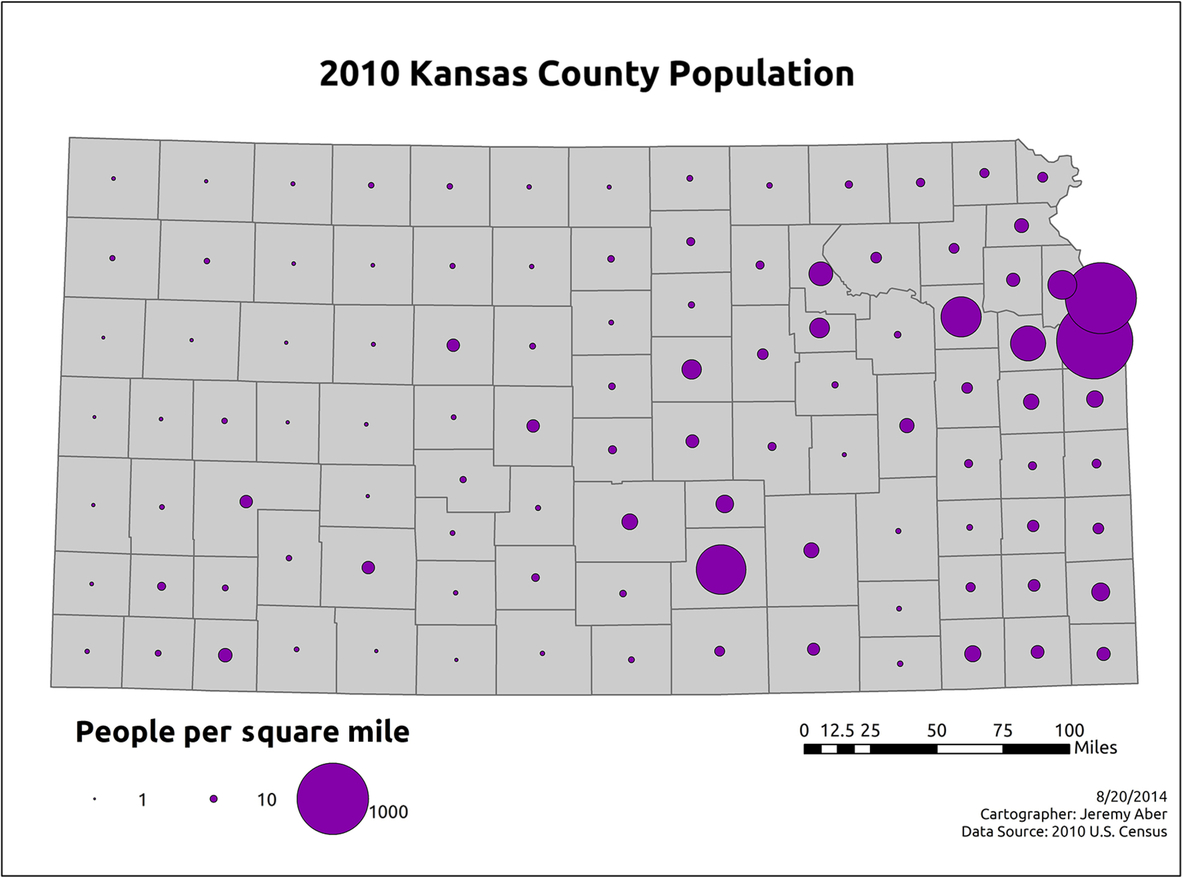

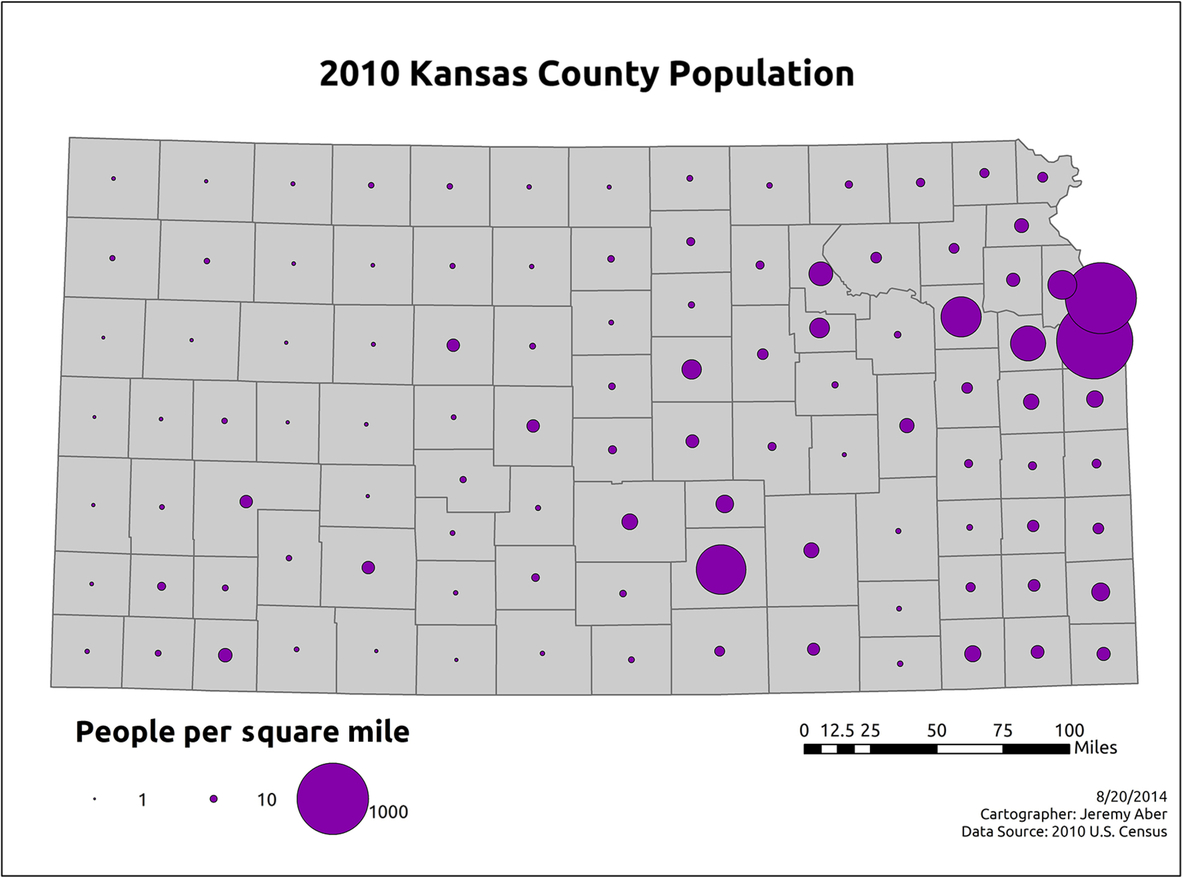

The proportional symbol map takes our population data and instead of changing colors, creates symbols with sizes that vary based on their values. These maps are relatively simple to interpret, but symbol overlap can be confusing at times. Fig. 2.6 shows an example of a proportional symbol map.

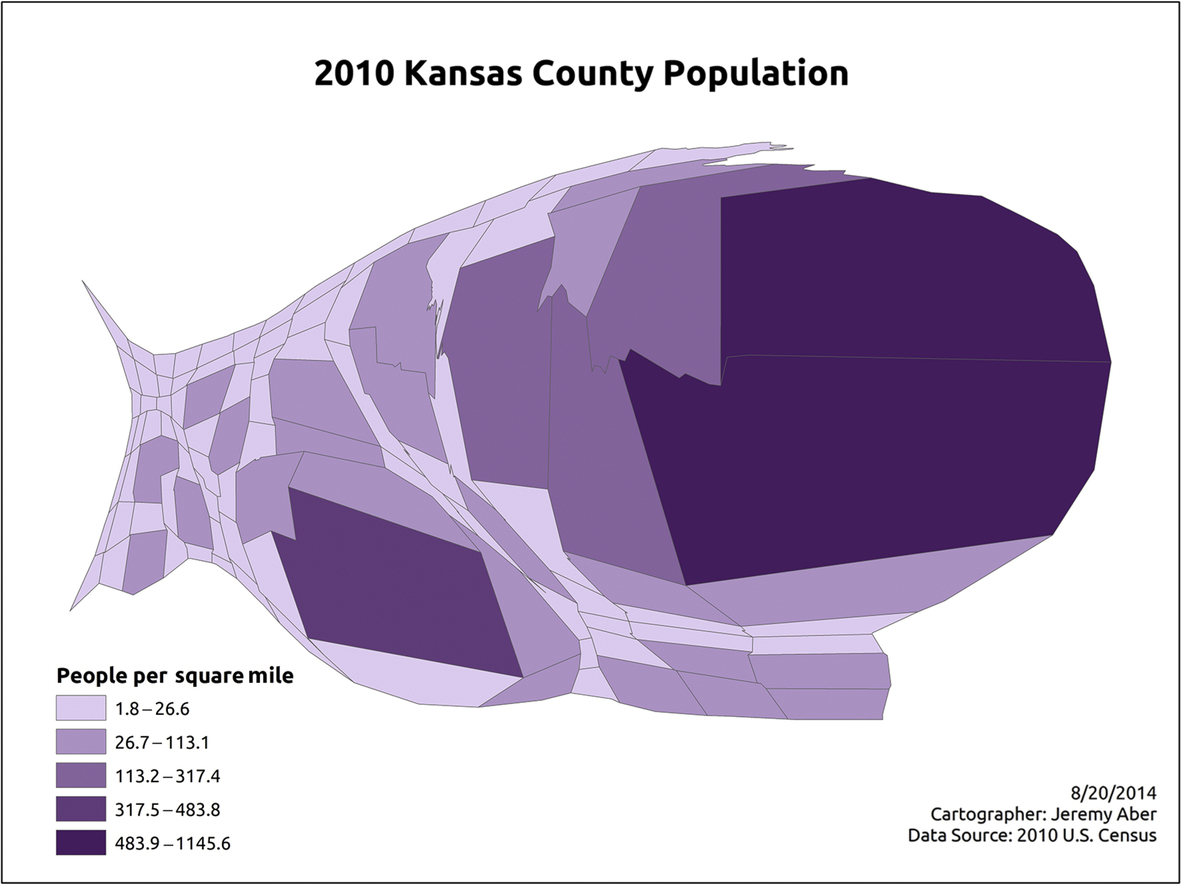

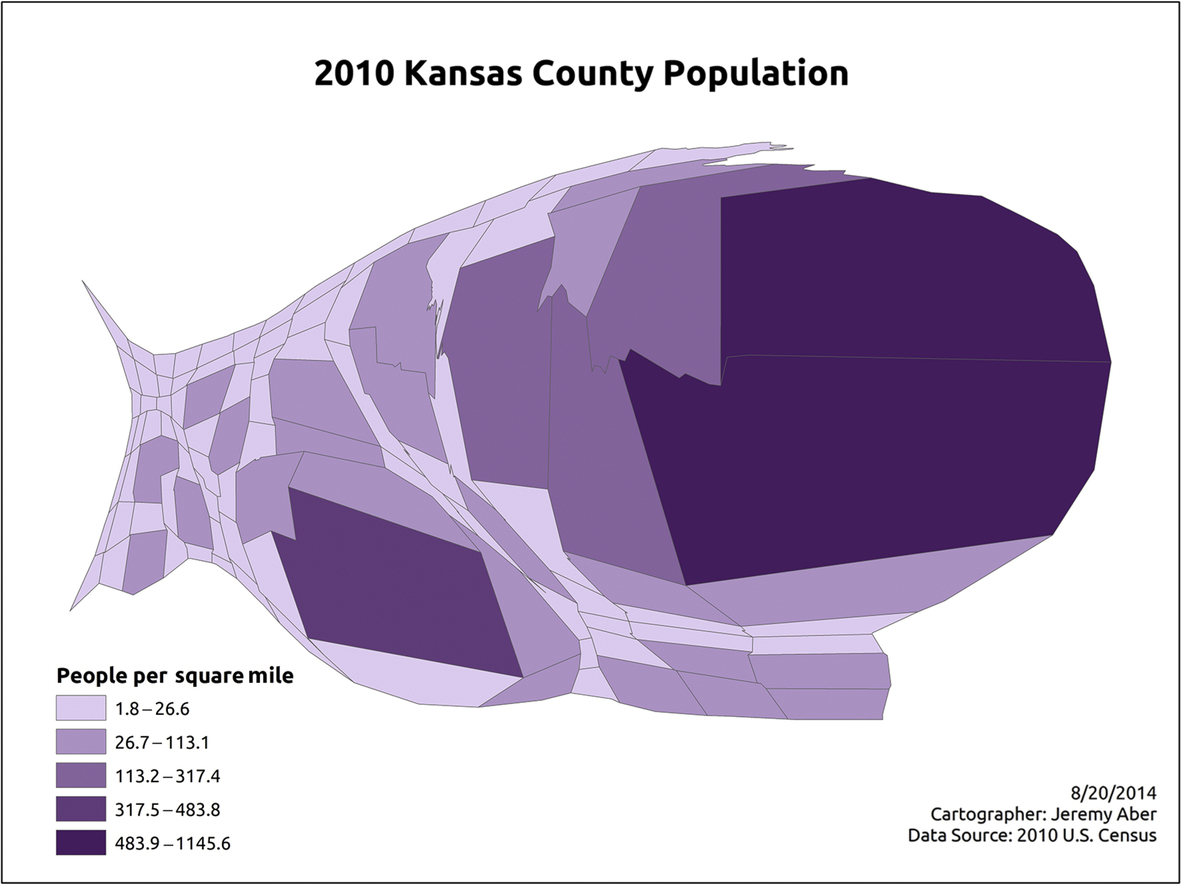

The cartogram is unique as a symbology approach, as it actually distorts the geometry of the underlying features in its representation of data. Cartograms can be visually dramatic, but they can also be difficult to interpret. For example, in Fig. 2.7 some of the smallest Kansas counties also have the largest population densities, so they dominate the layout. Other counties in the west with smaller populations become so tiny that they are difficult to read. Obviously, this approach to visualizing data renders the map useless as a source of navigational information, but at the same time it can also be a powerful method of presenting information. This technique is particularly good at showing disparities in values between areas.

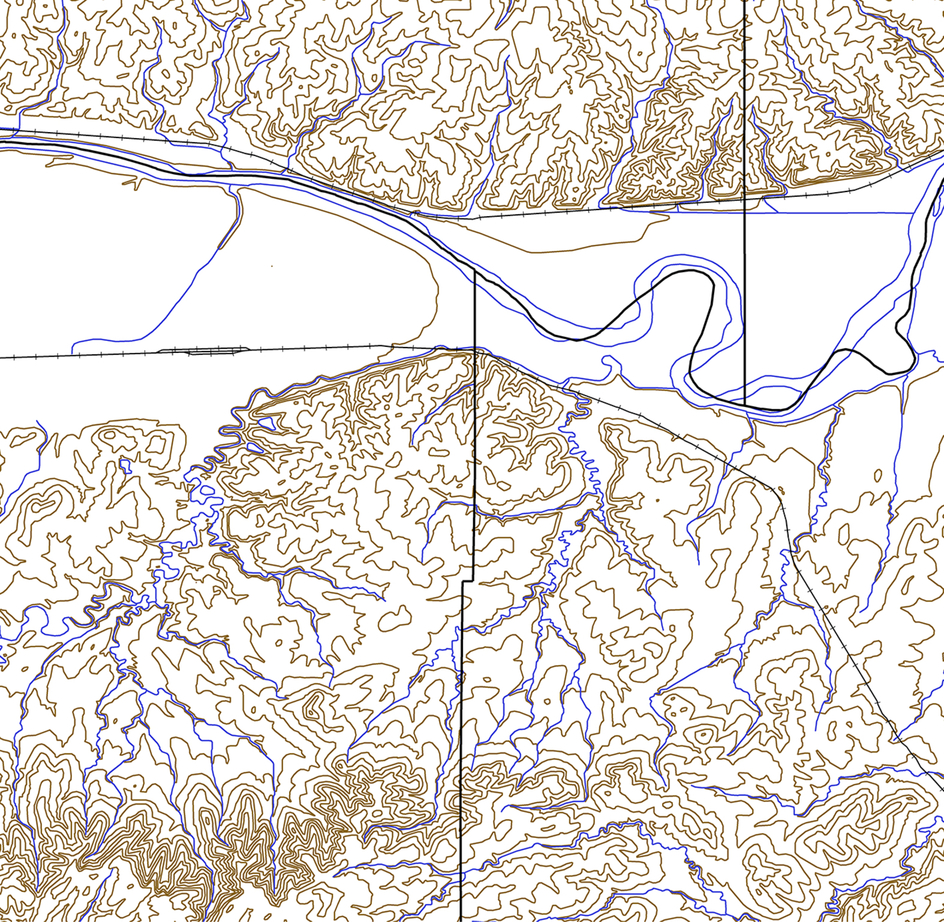

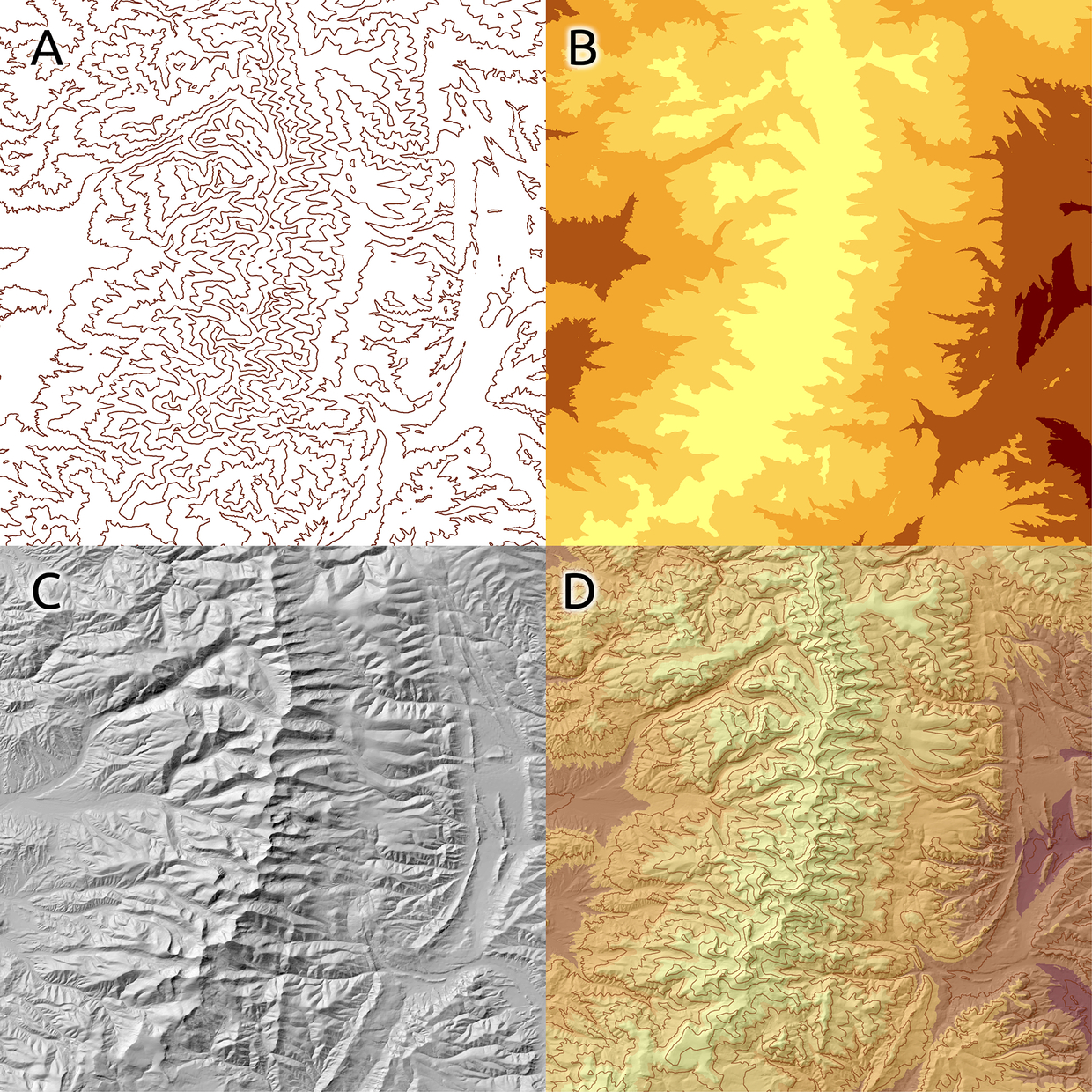

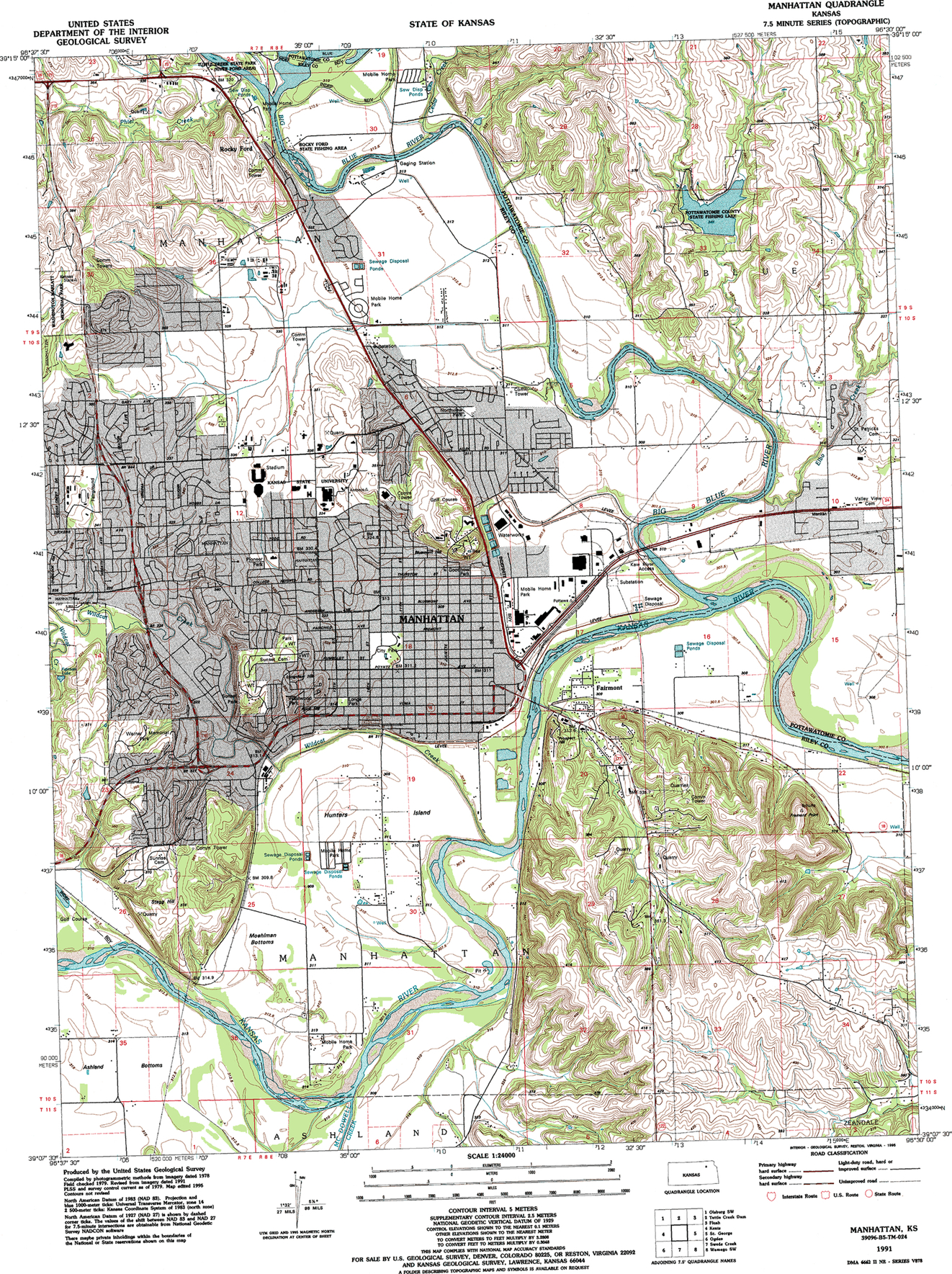

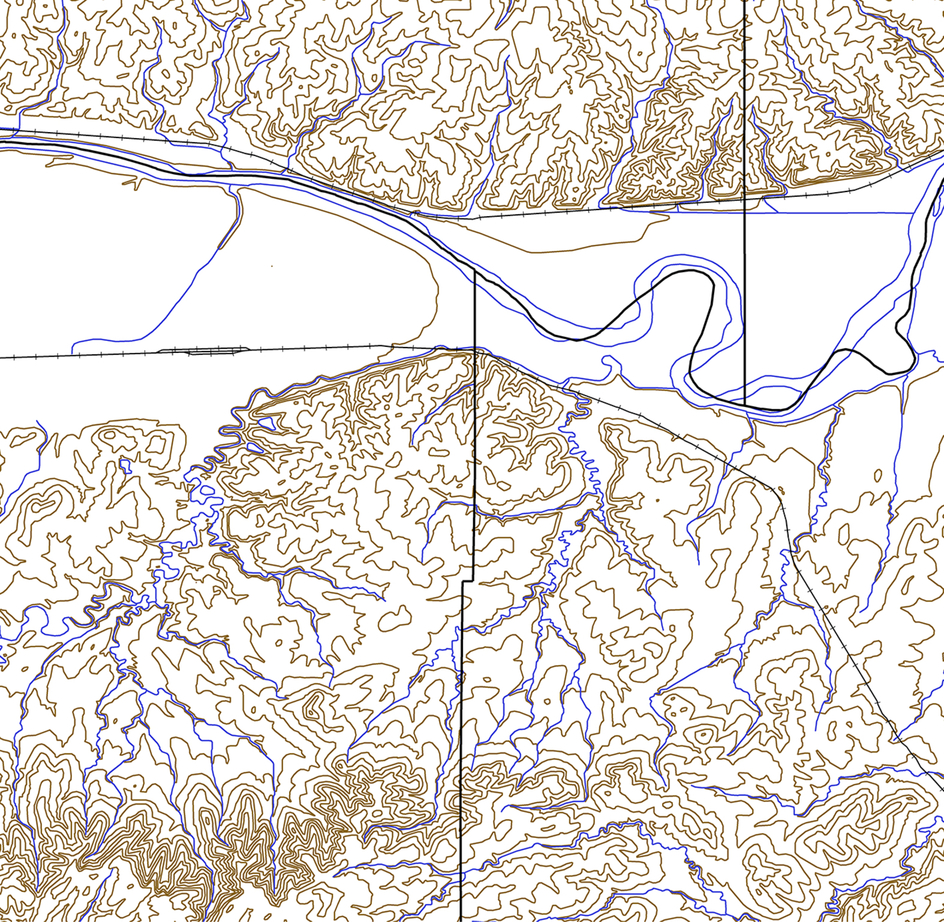

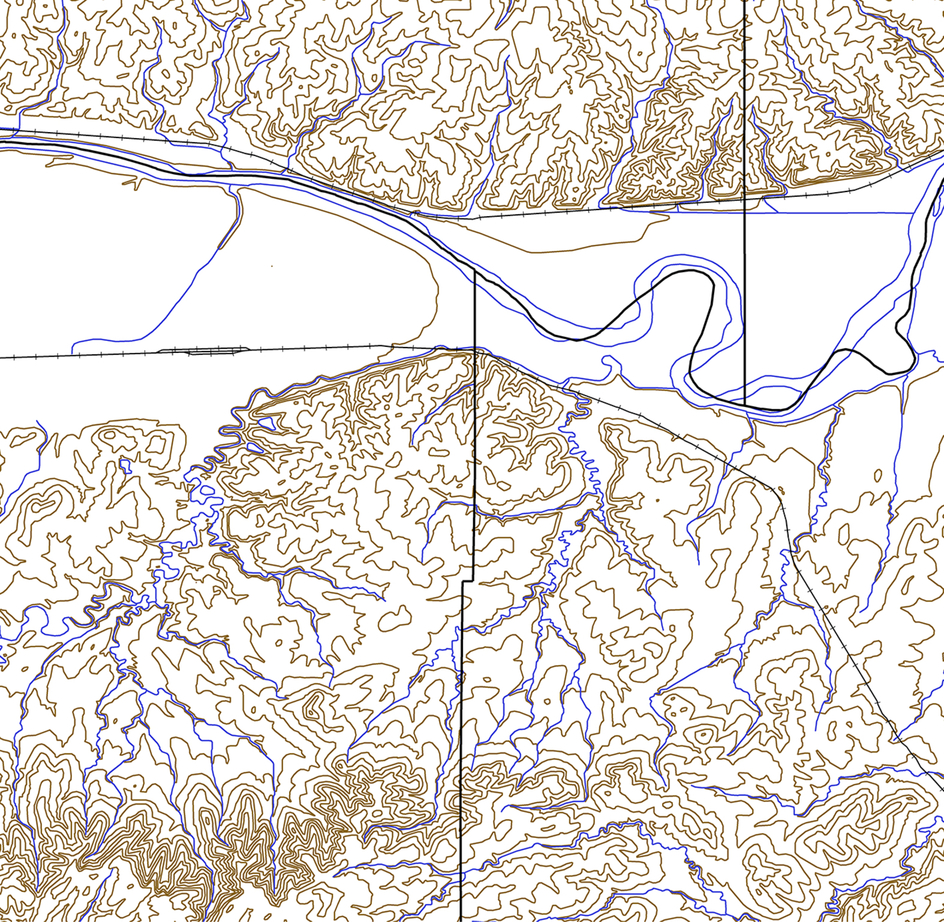

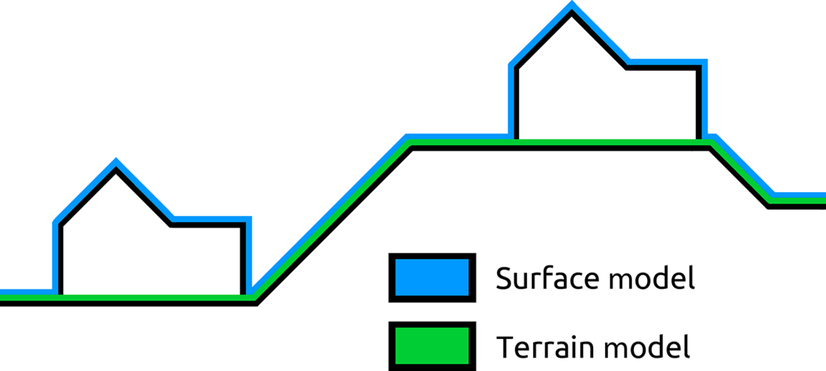

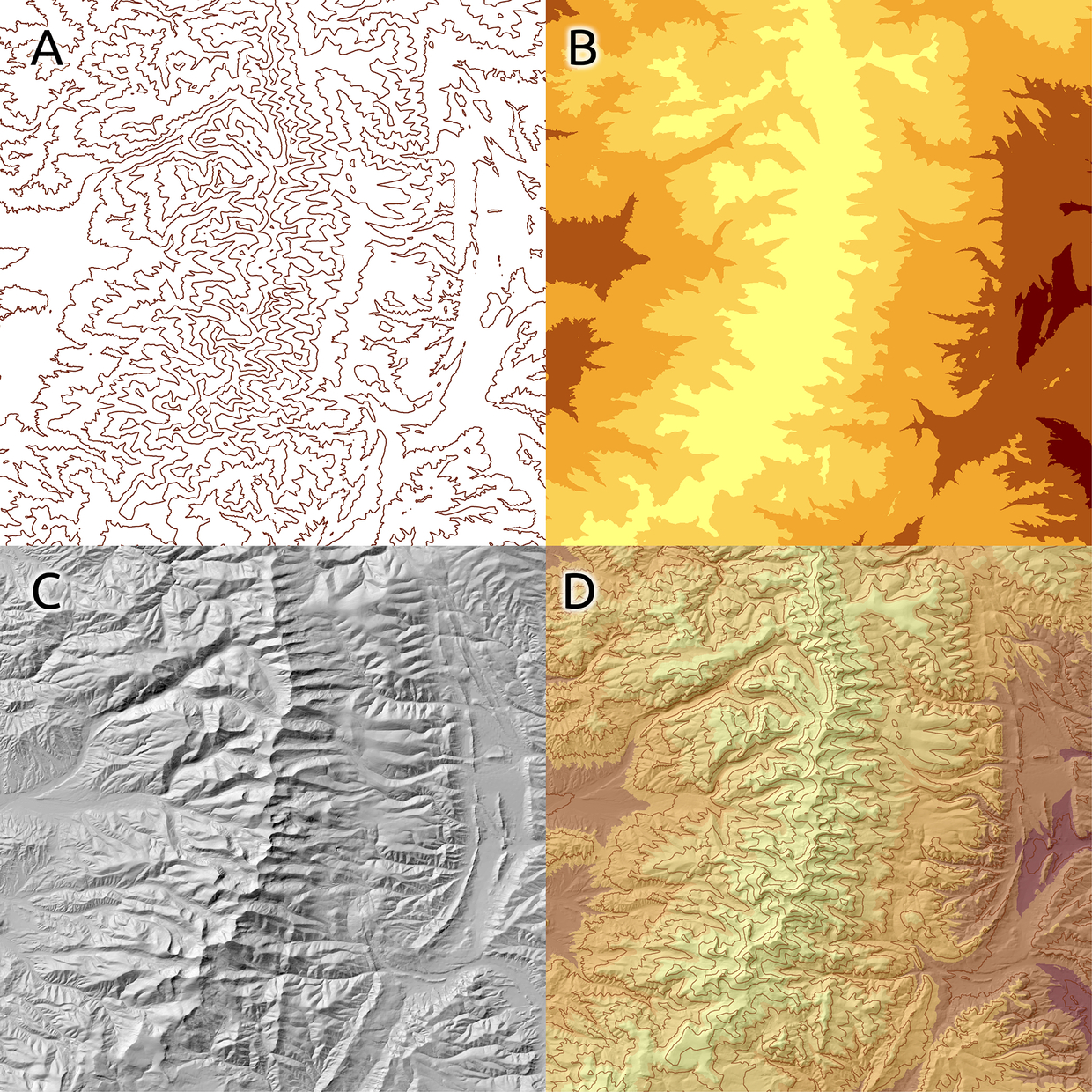

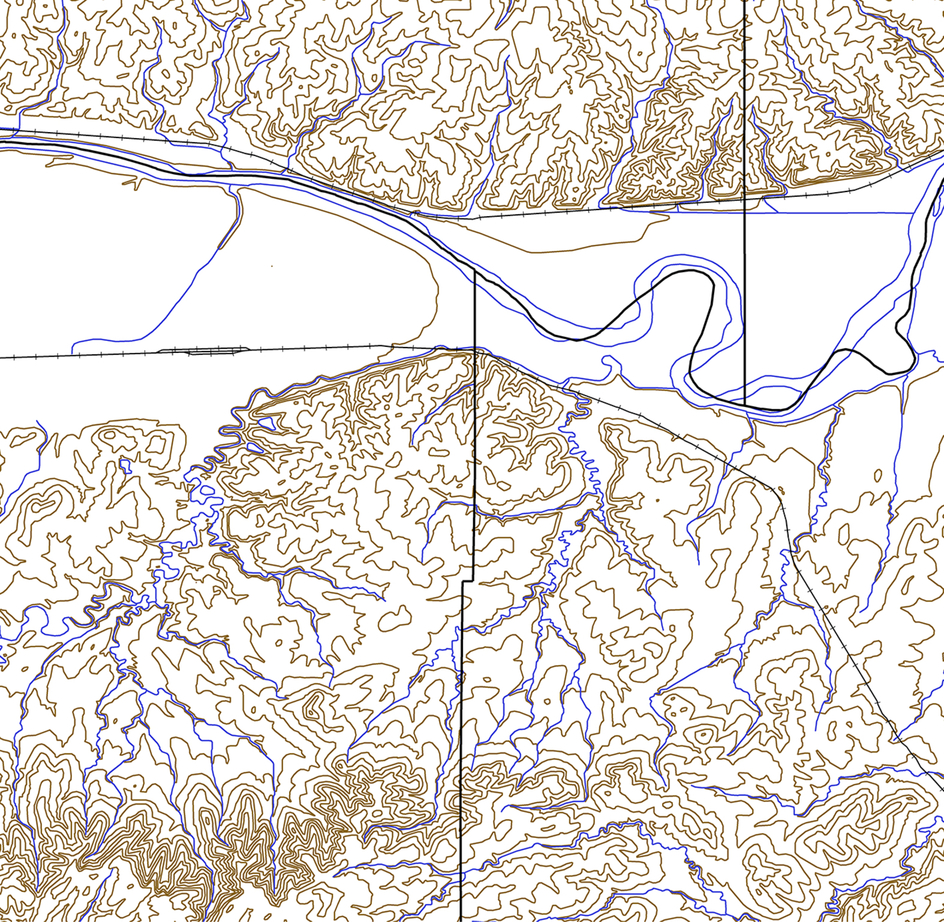

Many maps represent geographic surfaces, often the physical elevation above sea level. This can also be a virtual elevation representing data values. Map surface information can be quite valuable, from topographic maps representing physical elevation to weather maps showing the distribution of barometric pressure in the atmosphere. Since maps are two-dimensional and elevation is three-dimensional by nature, multiple approaches to symbolizing elevation have been created over the years. Perhaps the most common is the use of isolines, referred to as contour lines in the context of surface elevation. Each line represents an elevation that is consistent across every point on the line. It is common to only label some of the contour lines and to have a declaration of the contour interval described in the legend; elevation can be found by counting the contours. Actual surface elevation at any point on the map exists somewhere within a range defined by the values of the two surrounding contour lines. The closer contour lines are to each other on the page, the steeper the slope of the terrain represented; anyone who has used a topographic map for hiking can attest to this valuable map information. An example of contour lines can be seen in Fig. 2.8A.

The use of color can also be applied in what is called a hypsometric tint. The elevation of the surface is broken down into ranges, and a unique color is applied to each range, as seen in Fig. 2.8B. A shaded-relief approach can be used to generate a sense of dimensionality to a flat surface. For this technique, a virtual light source is used to generate shadows based on the elevation of the surface, an example of which can be seen in Fig. 2.8C. Finally, multiple approaches are often combined to give a better sense of the terrain. This can be quite effective, as the reader will get the specificity of the contour line technique in addition to the more visually appealing and “three dimensional” approaches of the hypsometric tint and the shaded relief. An example of this combined approach can be seen in Fig. 2.8D.

While most maps inherently have a location-based component, there are many different types of maps to serve specific industries and messages or themes. Snow’s cholera map was both a location-based reference and thematic map that served a specific public health message and purpose. Some explorations within a particular field employ thematic maps combined with change over time; for example, comparing topographic maps over the decades could show the growth of an urban area. These maps may also use various symbology techniques to further emphasize their message. In any case, different map type examples are discussed below. While this is in no way an exhaustive list, it will describe some of the more common map applications in the natural, political, and social sciences. Knowing about these types of maps will help in managing collections and pointing patrons to resources that fulfill their needs.

An aeronautical chart focuses on the information necessary for the navigation of aircraft. In the United States, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) produces multiple maps showing information such as terminal procedures and airport diagrams. These charts are used for flying both under Instrument Flight Rules (IFR) and Visual Flight Rules (VFR), an example of which can be seen in Fig. 2.9. FAA charts can be freely downloaded in a digital format from their website (Federal Aviation Administration, 2016a).

An atlas is a collection of maps, and countless atlases have been produced over the years. Library collections are likely to have an atlas or two on hand, and in the United States, that atlas may well be one or more of the editions of the National Atlas of the United States. This atlas series was first published as a print edition in 1874 covering the 1870 census (Internet Archive, 2014; U.S. Geological Survey, 2015a). Later editions covered the census through 1920. After a fifty year gap, it was again printed in 1970, this time as a 400 page edition with maps covering all manner of topics. In 1997, the National Atlas was re-envisioned as a digital edition overseen by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), with all maps available through a web interface. This version was retired in 2014, but digital maps from this collection are still available on The National Map Small-Scale Collection website (U.S. Geological Survey, 2015b). At this time, the National Atlas has merged with The National Map (Newell, Donnelly, & Burke, 2014). As such, The National Atlas data can be accessed and downloaded from The National Map (U.S. Geological Survey, 2015c) and Earth Explorer (U.S. Geological Survey, 2016a).

The gazetteer is the counterpart to the atlas, providing an index to the features included in an atlas, cross-referenced so that the reader can find which map contains a specific feature. Gazetteers often include information regarding features such as location and relevant demographic information. An essential service in a print era, the gazetteer has become less prominent in today’s paradigm of digital searching. With a printed atlas, finding a geographic feature was often impossible without prior knowledge or the use of a gazetteer; now locations are a quick Google search away. Despite this, the gazetteer survives in multiple forms, both print and digital. Modern printed atlases still contain gazetteer information, and online versions exist as a source of authoritative place names. Examples of online gazetteers include digital files describing features in the United States available for download via websites at the U.S. Census Bureau (2015) and the U.S. Board of Geographic Names (U.S. Geological Survey, 2015d). One worldwide gazetteer is the U. S. National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency’s GEOnet Names Server (GNS), which provides both text and map search options (National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, 2016). Other national gazetteers include the Canadian Geographical Names (Natural Resources Canada, 2014), Gazetteer of British Place Names (The Association of British Counties, n.d.), the Gazetteer for Scotland (University of Edinburgh & Royal Scottish Geographical Society, 2016), The National Gazetteer of Wales (2001), Gazetteer of Ireland (Haug, 2007), as well as an Antarctic gazetteer (U.S. Geological Survey, 2013).

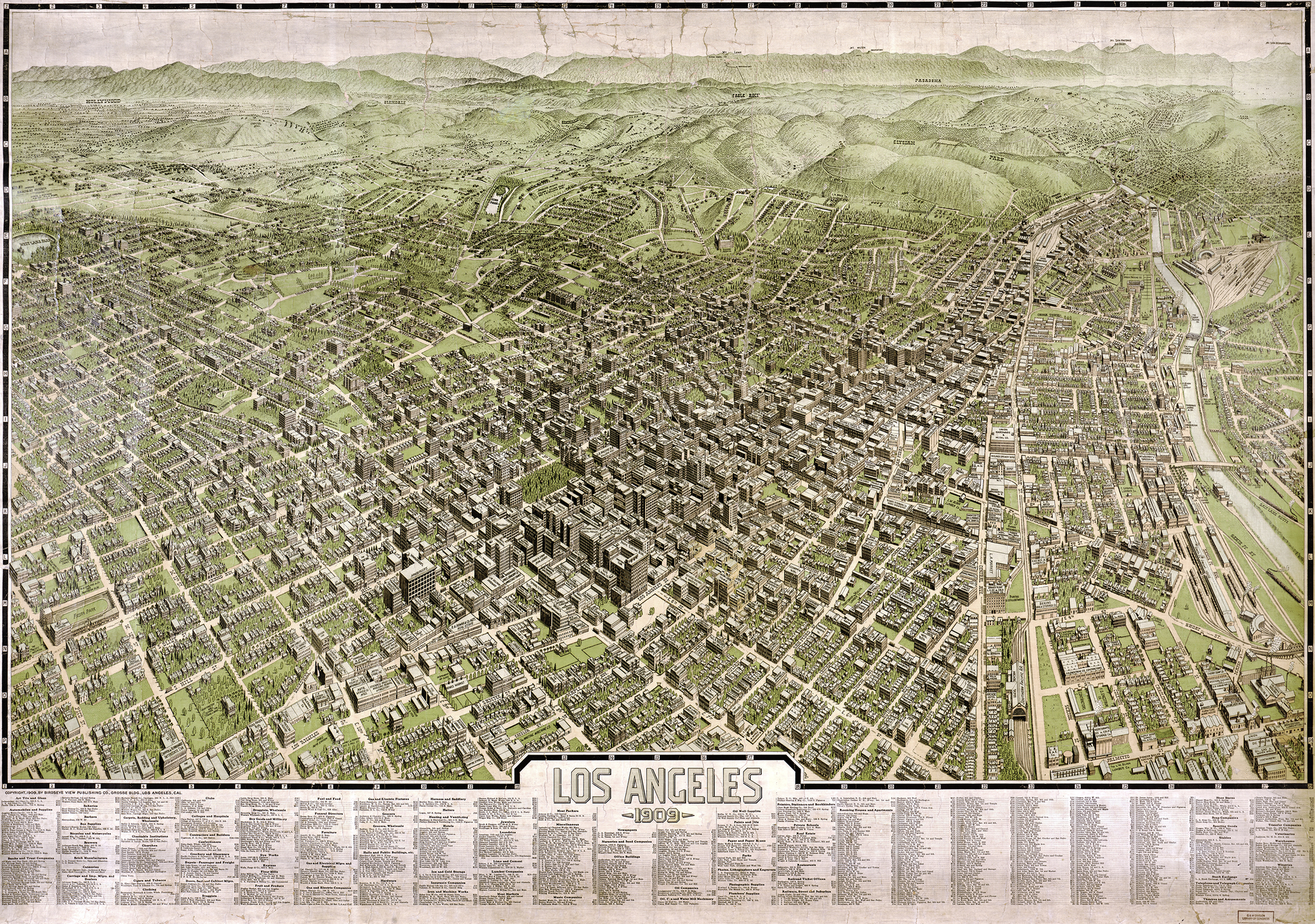

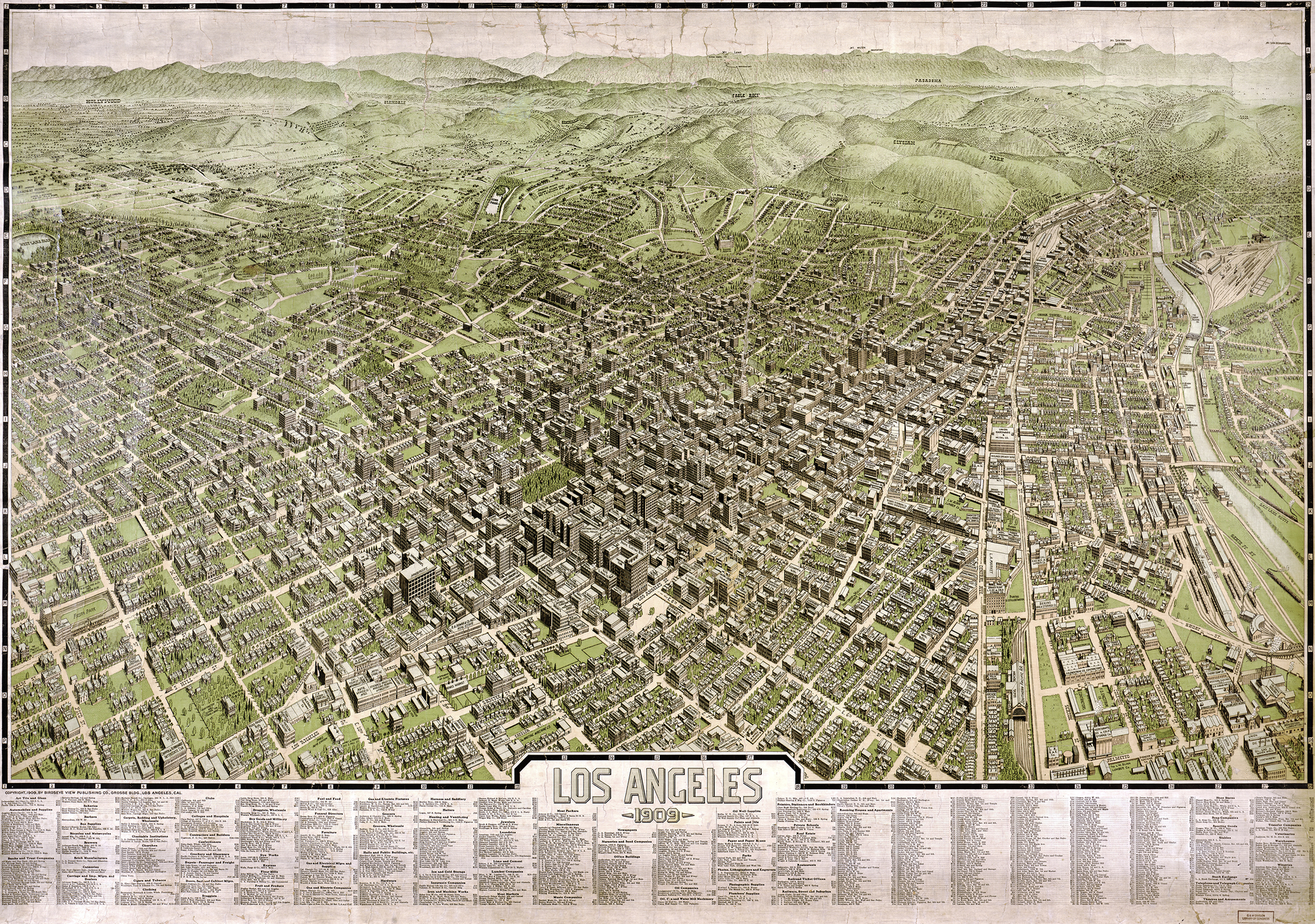

A bird’s-eye view map represents the land as if viewed from the panoramic vantage point of a bird mid-flight. This map style was quite common in the United States and Canada during the 1800s for representing cities of all sizes (Short, 2003). Traditionally, these maps were produced by an artist working from street plans. Road layouts would be drawn in perspective then filled in with details of the buildings and features found in the city. Because this map style was so popular, many of these maps exist today as records of what cities and towns were like at the time. Fig. 2.10 shows an example of this style of bird’s-eye view map of Chicago, circa 1857. Today, the bird’s-eye view survives in digital form. Platforms such as Google Earth, Google Maps, Bing Maps, and others provide perspectives similar to the traditional bird’s-eye view map, albeit interactive ones. These services typically combine aerial imagery and three-dimensional models of buildings and other structures to allow users to explore urban areas from the bird’s-eye perspective.

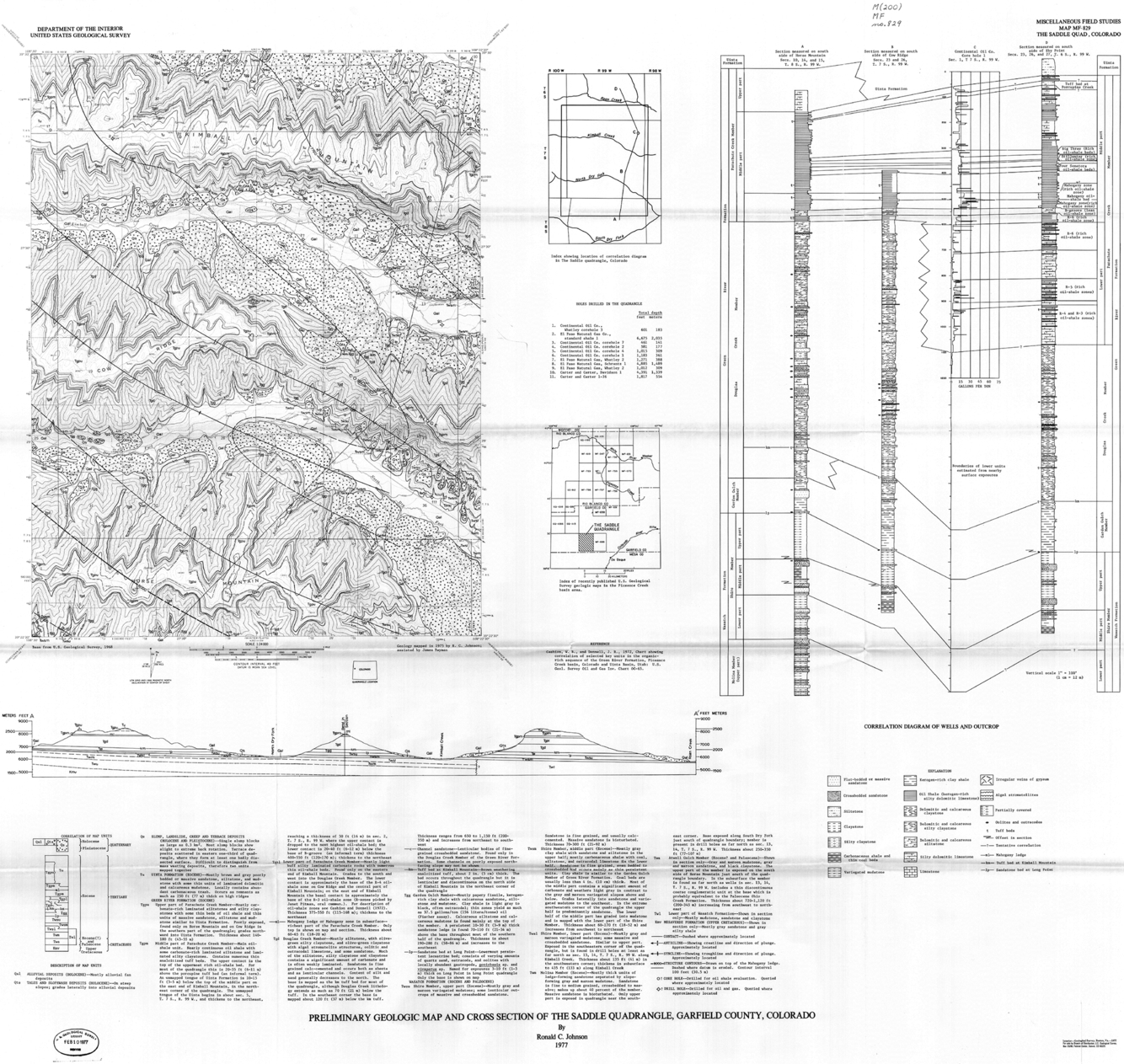

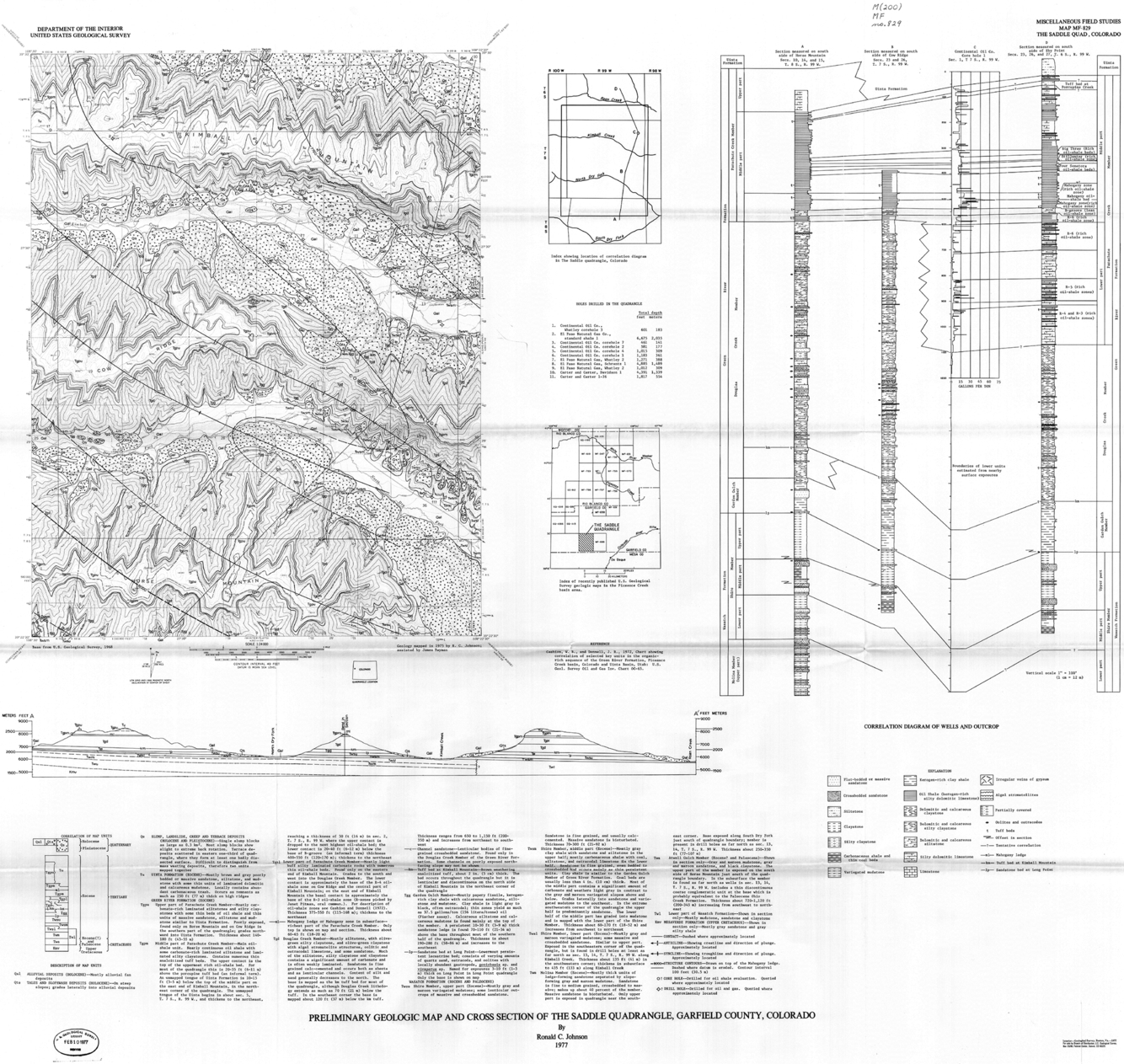

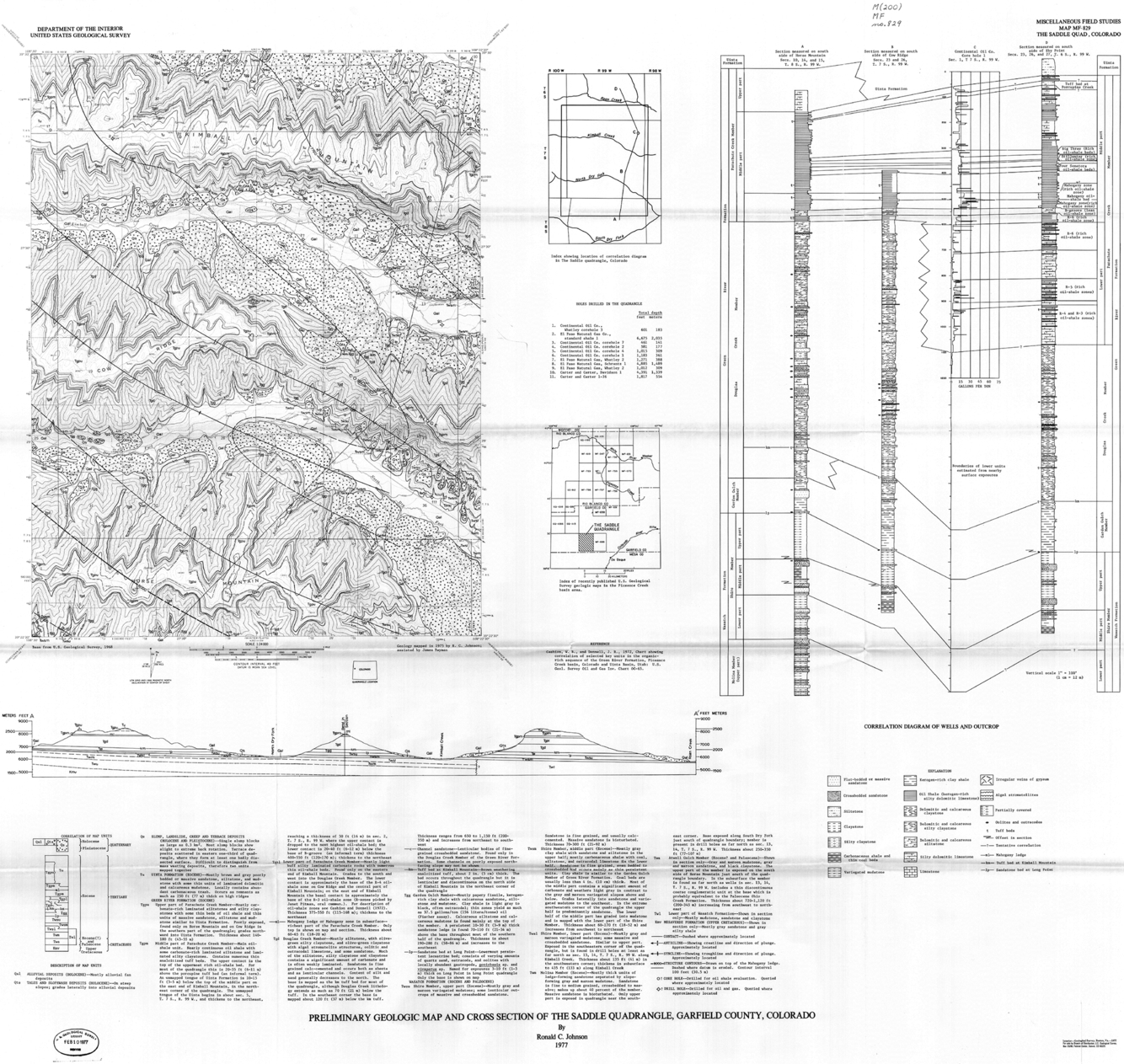

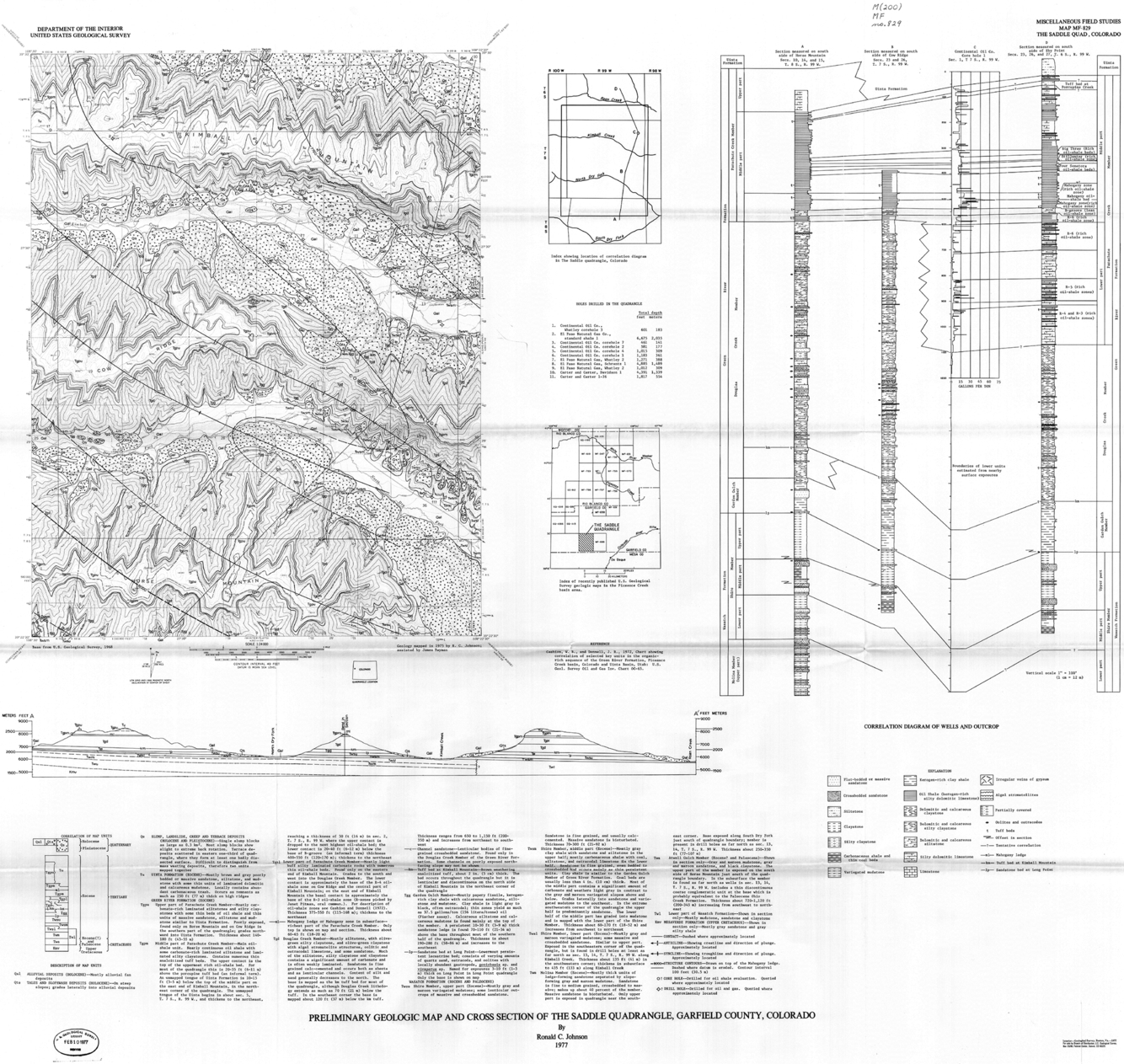

The USGS has long mapped fossil fuel resources and reserves in the U.S., with oil and gas map series beginning in the 1940s, and coal maps in 1950 (U.S. Geological Survey, 2016b). Today the USGS Energy Resources Program is responsible for tracking the state of energy resources in the U.S., including coal, oil, and natural gas quantities and quality. Current information can be downloaded in report or digital GIS formats via the USGS Energy Data Finder (U.S. Geological Survey, 2016c). However, older paper map data can still be found digitally online and in some collections as hard copy including a folder and supplementary information (U.S. Geological Survey, 2016b). An example of one of these older paper maps showing a coal investigation in Colorado can be seen in Fig. 2.11.

Geologic maps show the distribution of different types of rock and surface materials. They often include the structural relationships between the different materials in the ground such as strata, faults, and folds. The first modern geologic map was created by William Smith in 1815, which can be seen in Fig. 2.12 (Winchester, 2001). Today’s geologic maps are not much different from Smith’s work. Many kinds of geologic maps exist including surficial bedrock and sediment, subsurface rocks, fluids, and structures, and geophysical phenomena such as magnetism, heat flow, and gravity. In most environments vegetation, soils, water bodies, and human structures cover the surface, so that underlying rocks and sediments are not directly visible or exposed. Typically for geologic mapping purposes, the materials directly beneath the soil are depicted. This means the rocks or sediments that exist at shallow depth, usually 1 m in Europe or 5 ft in North America. An example of a generalized geologic map showing the state of Colorado can be seen in Fig. 2.13.

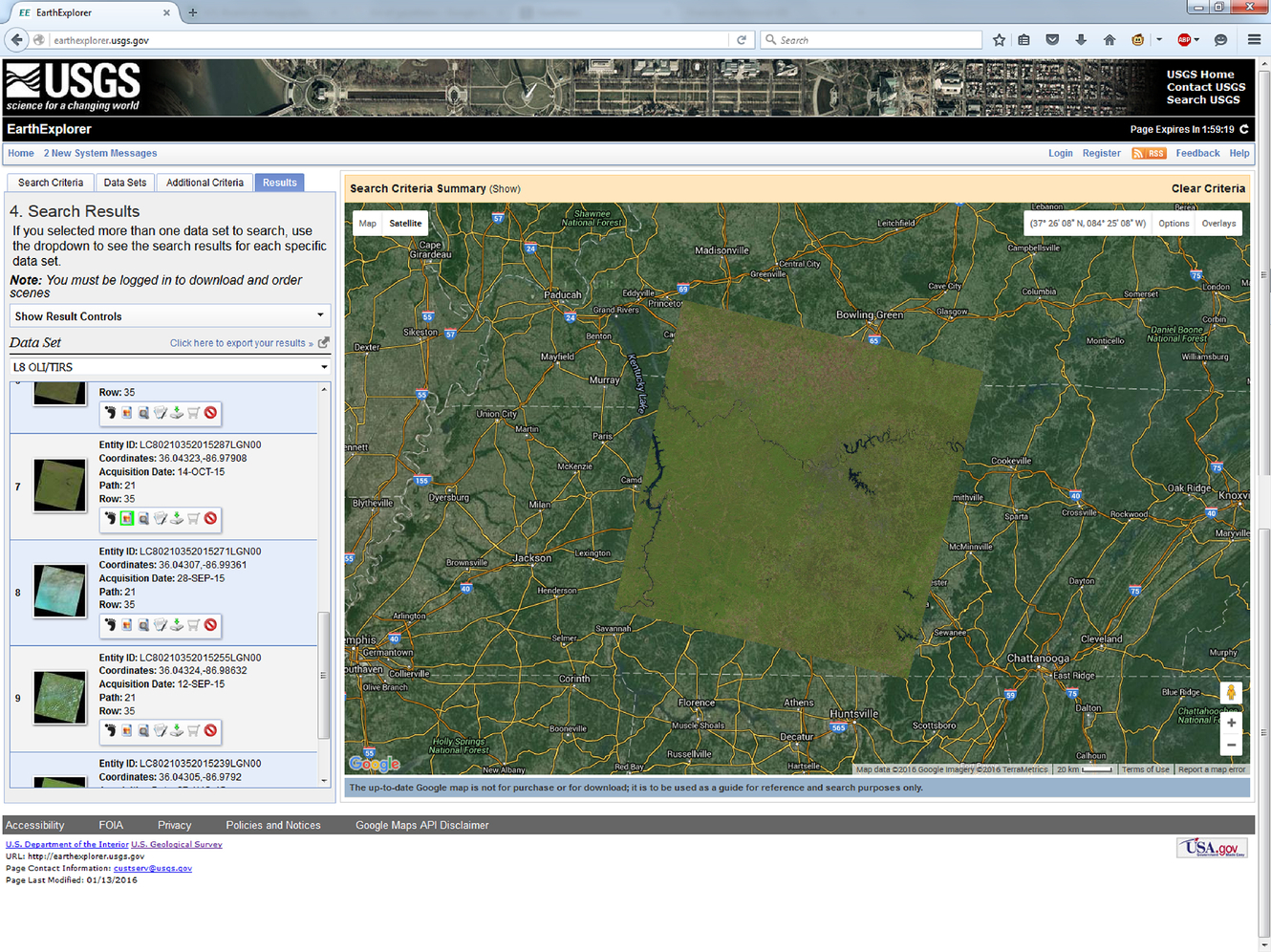

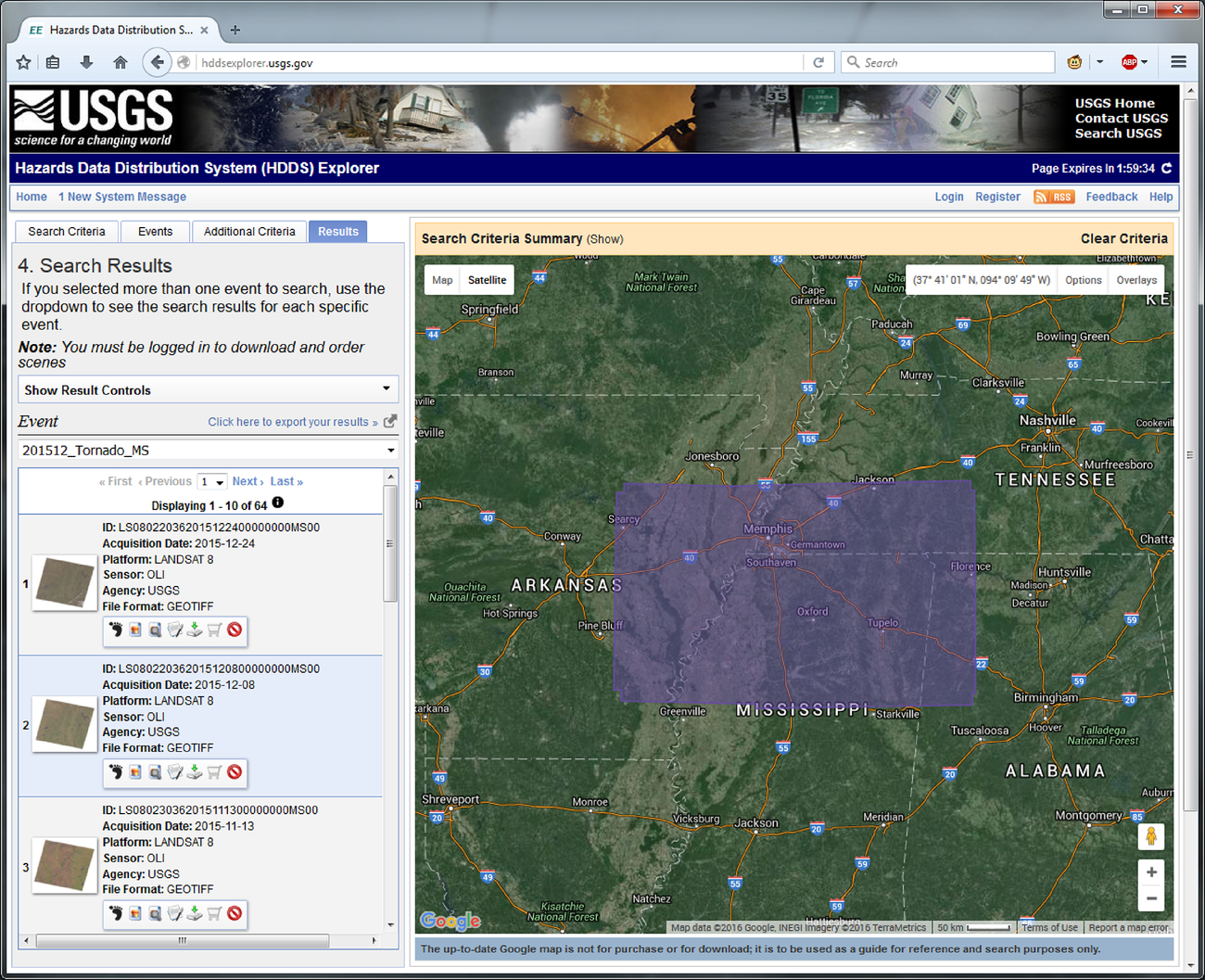

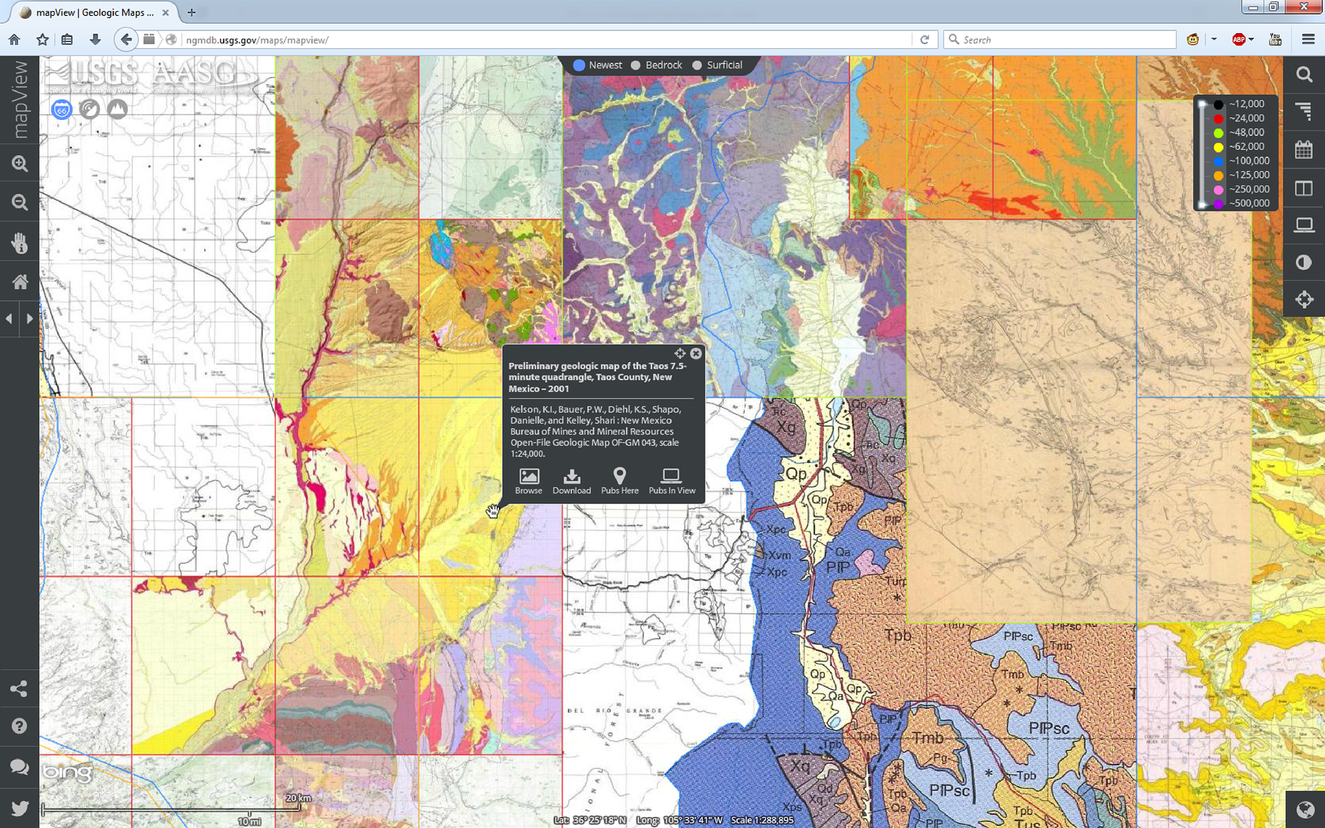

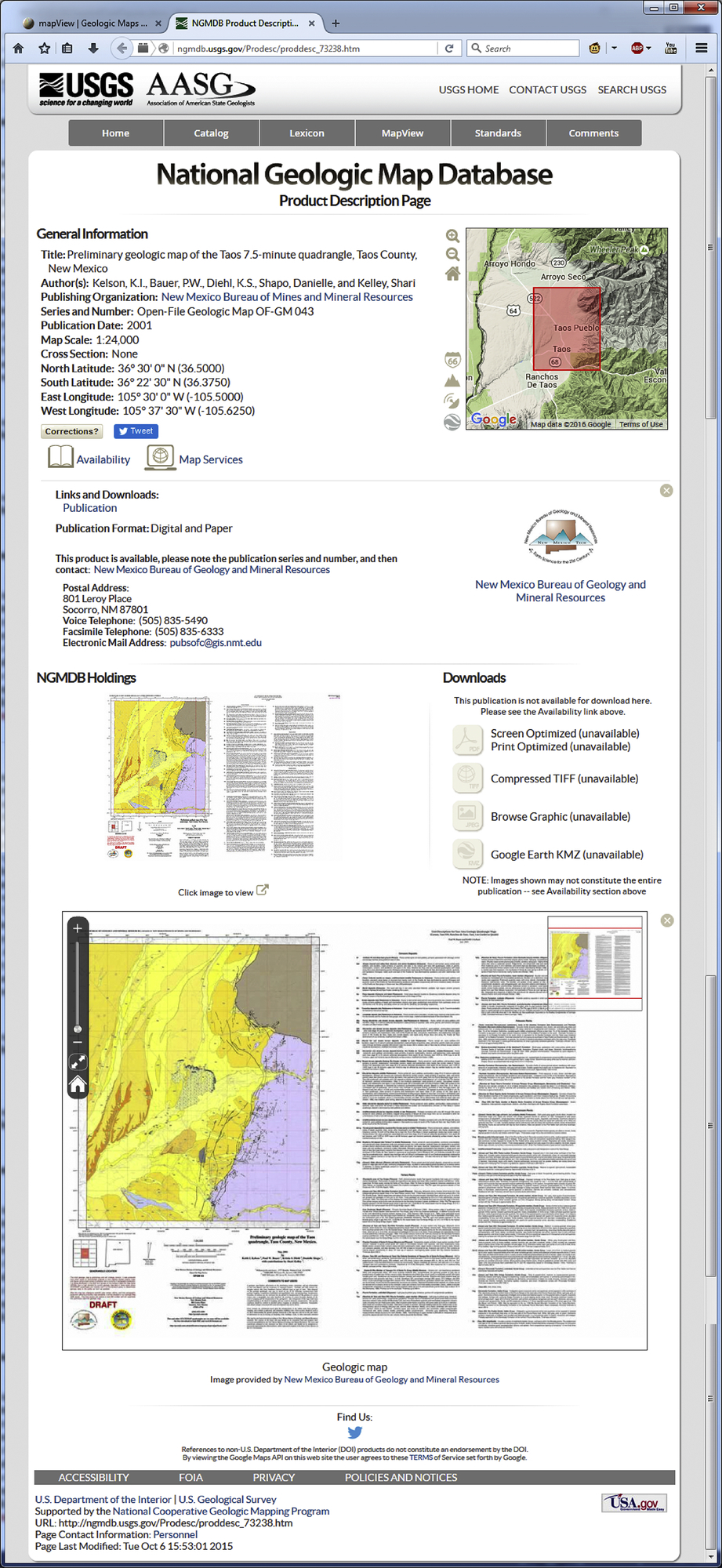

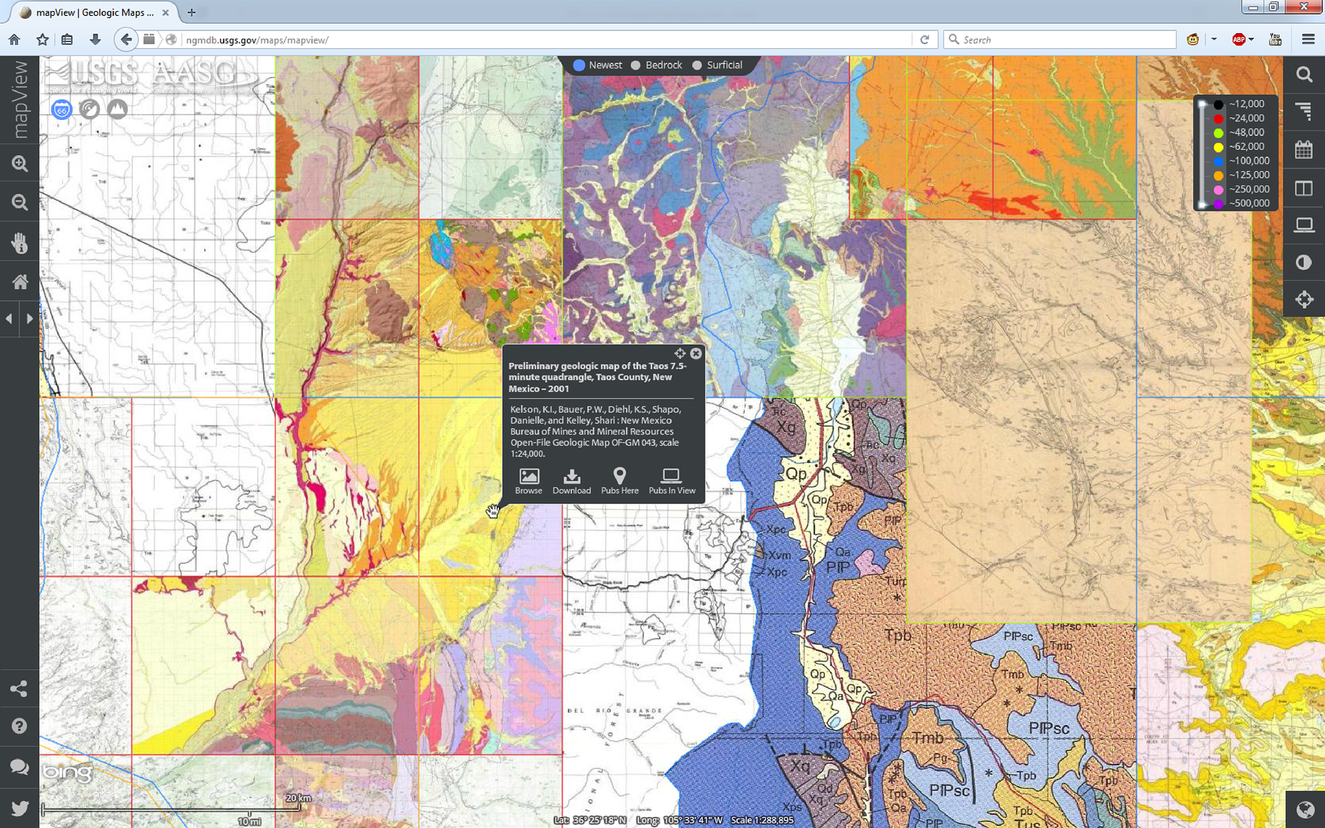

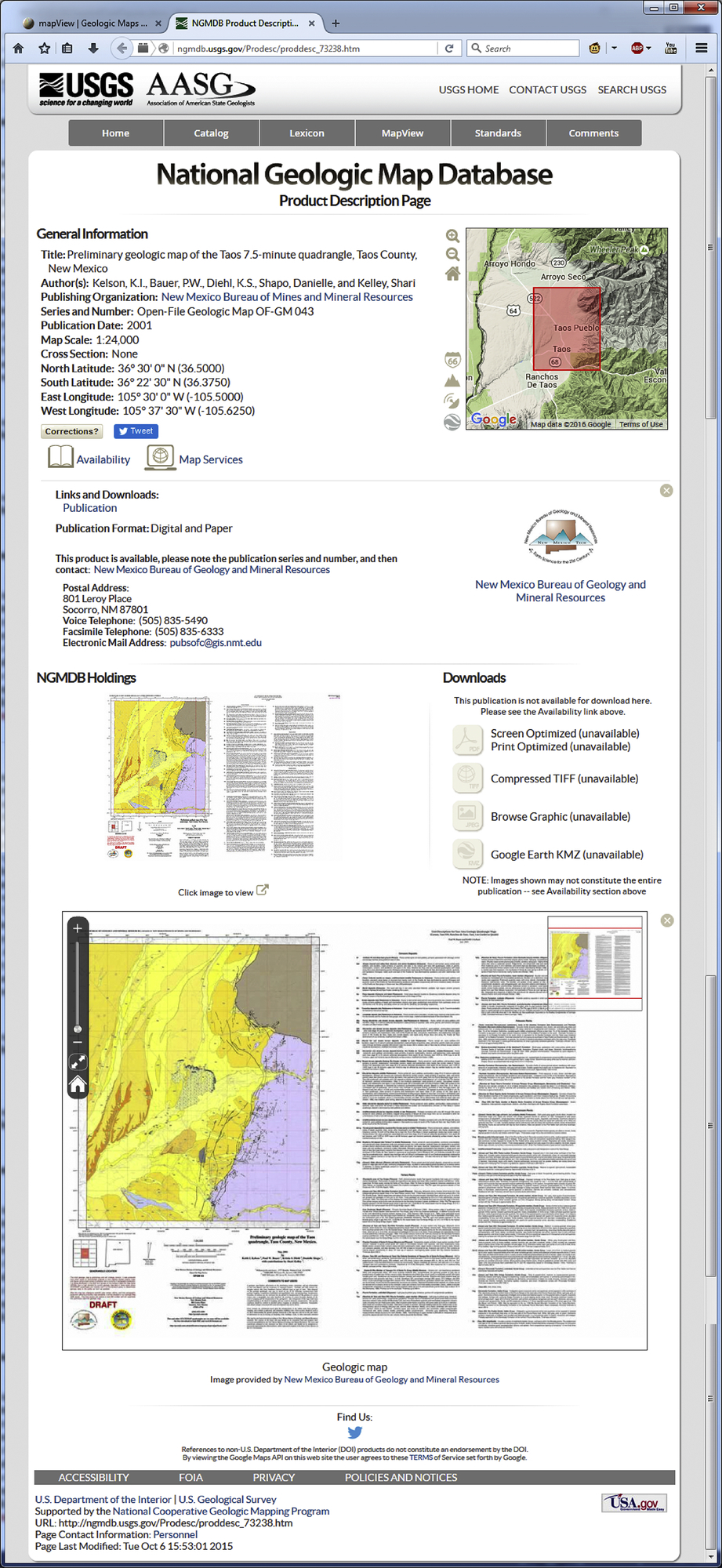

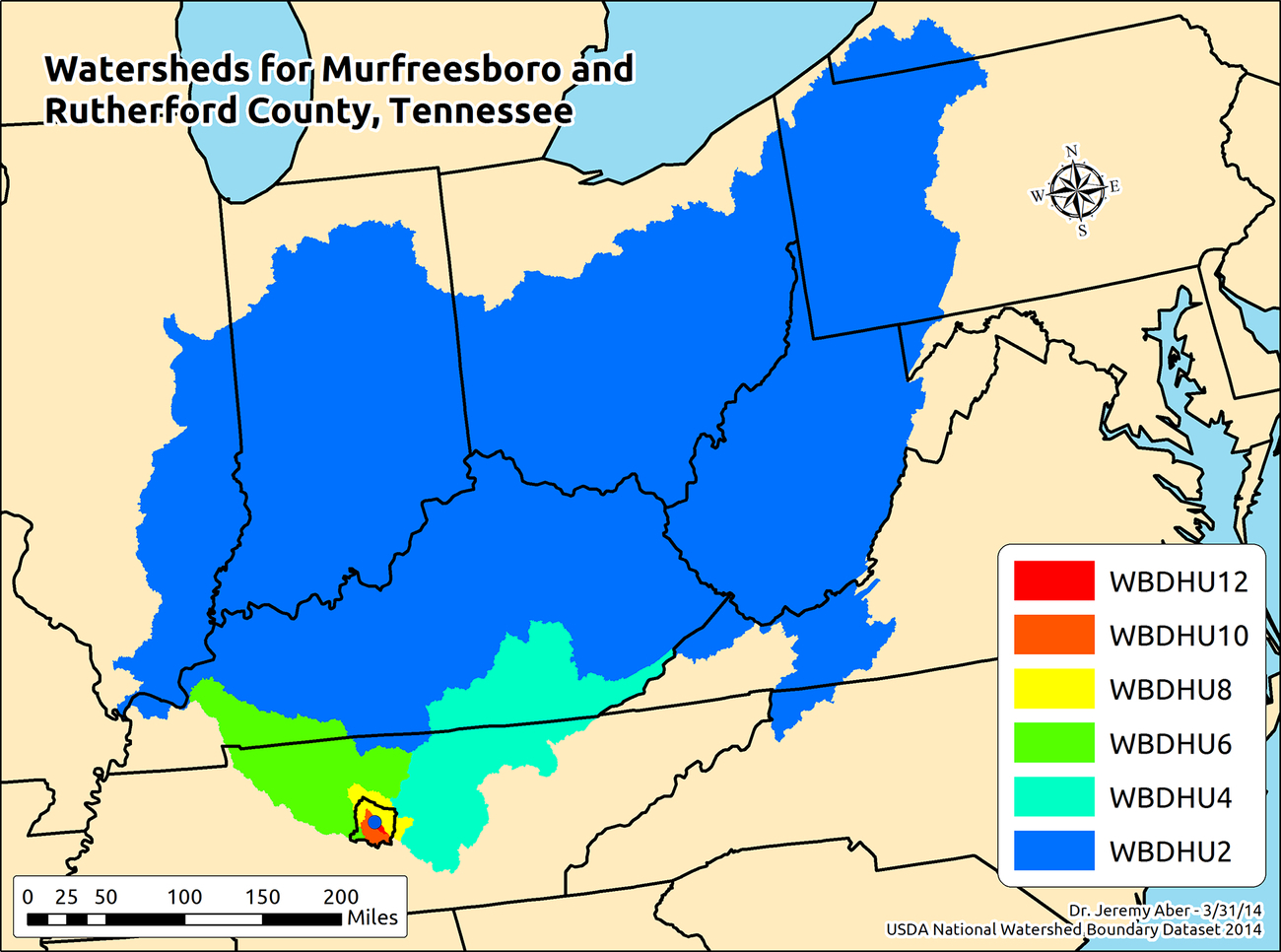

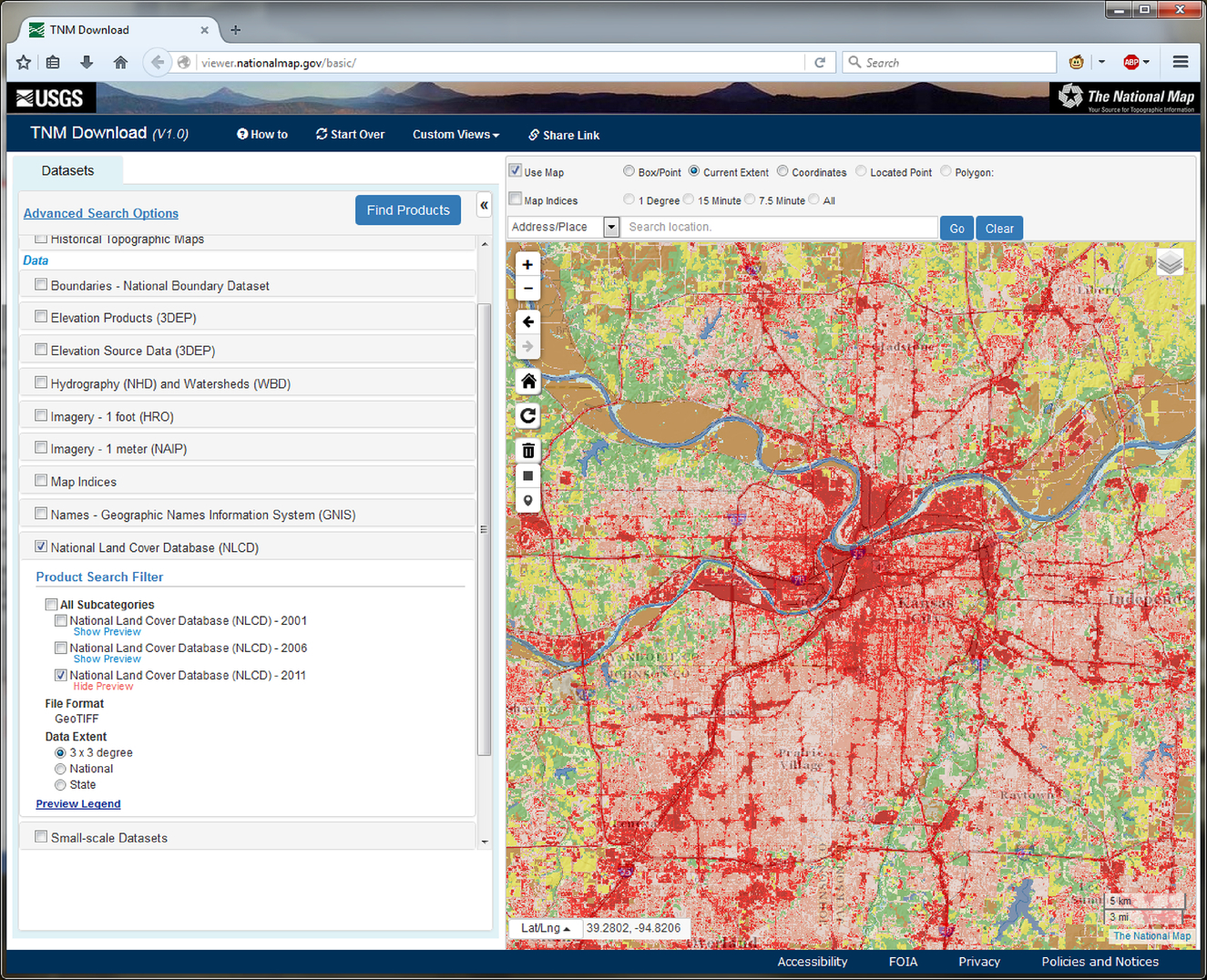

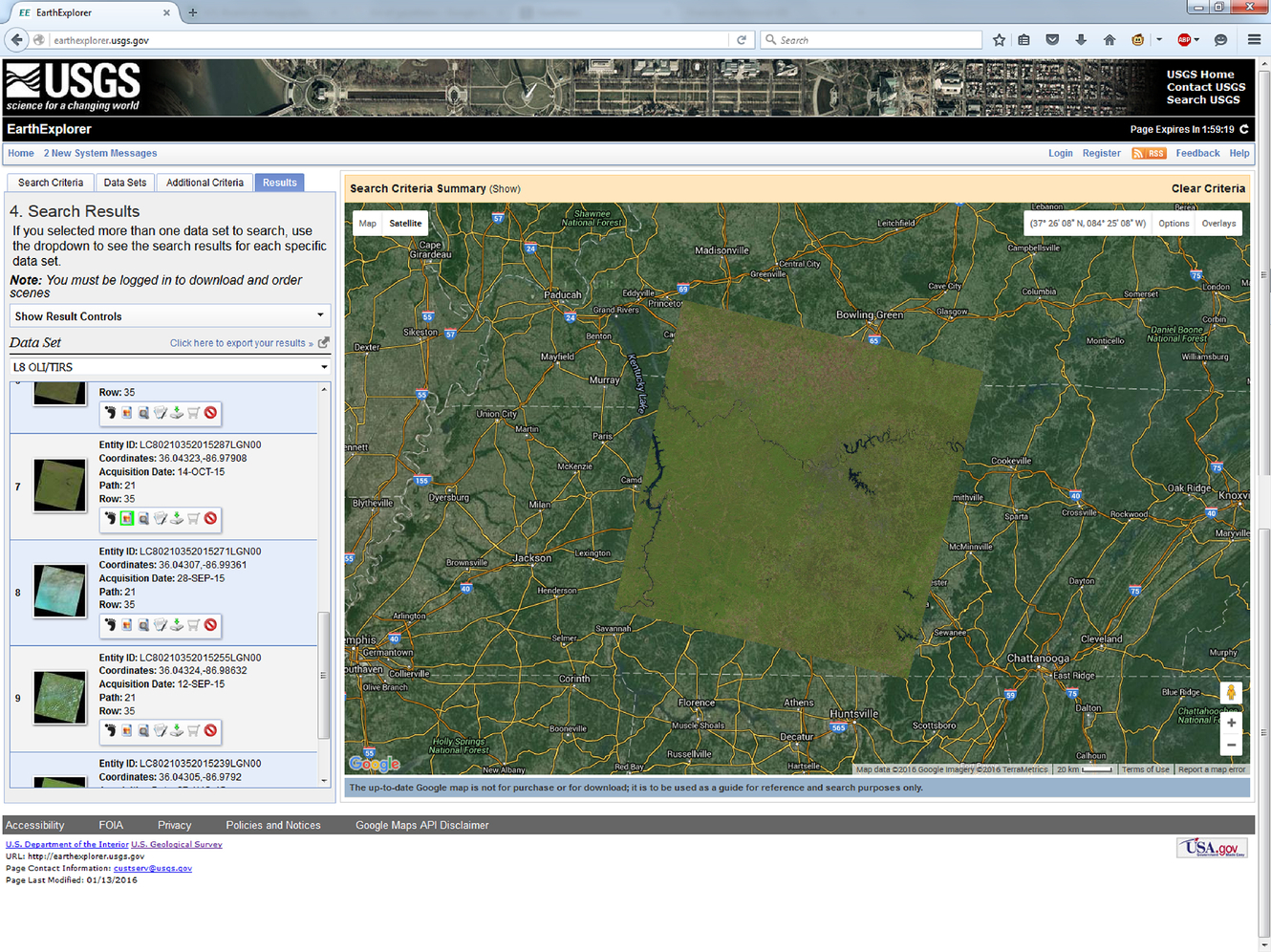

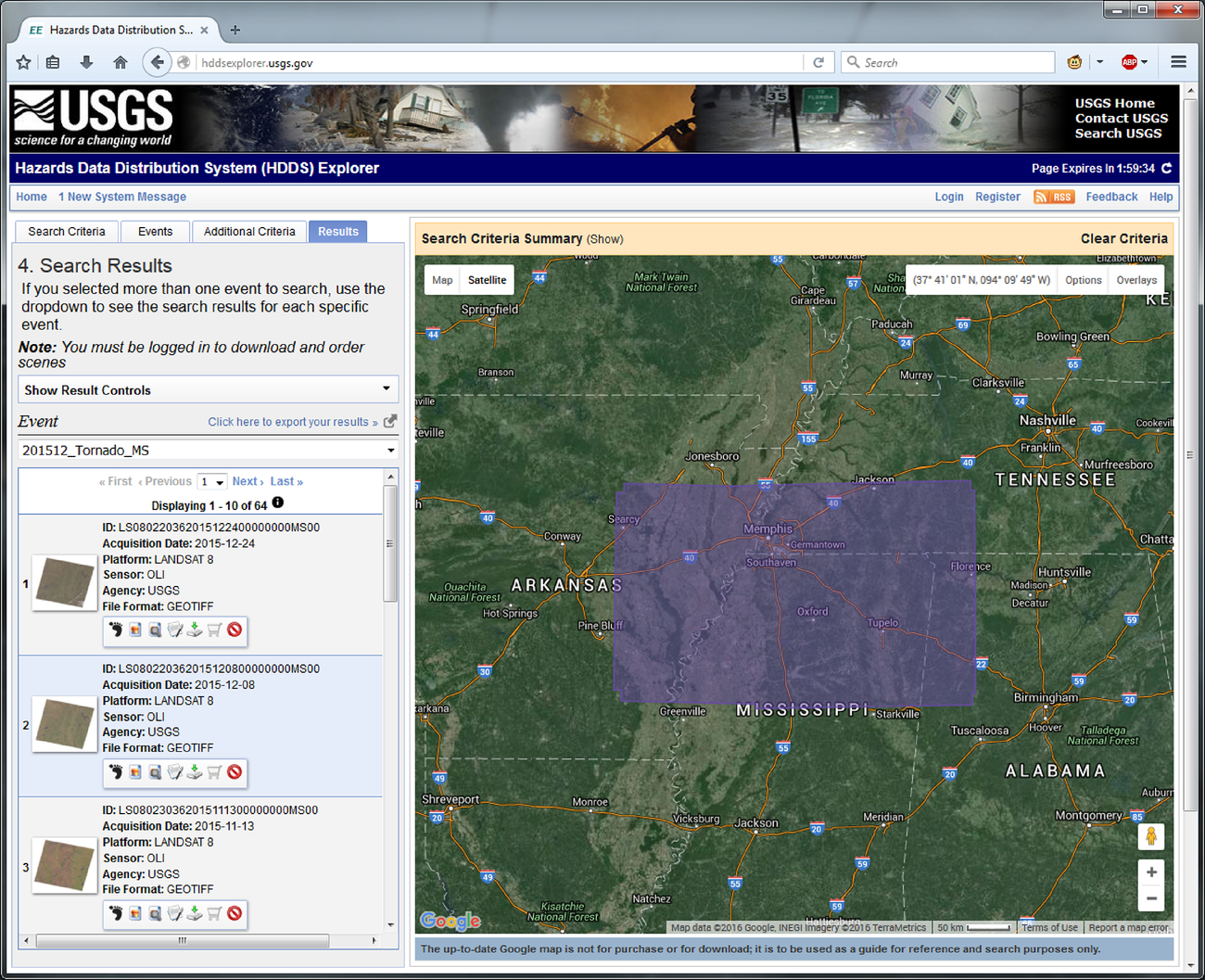

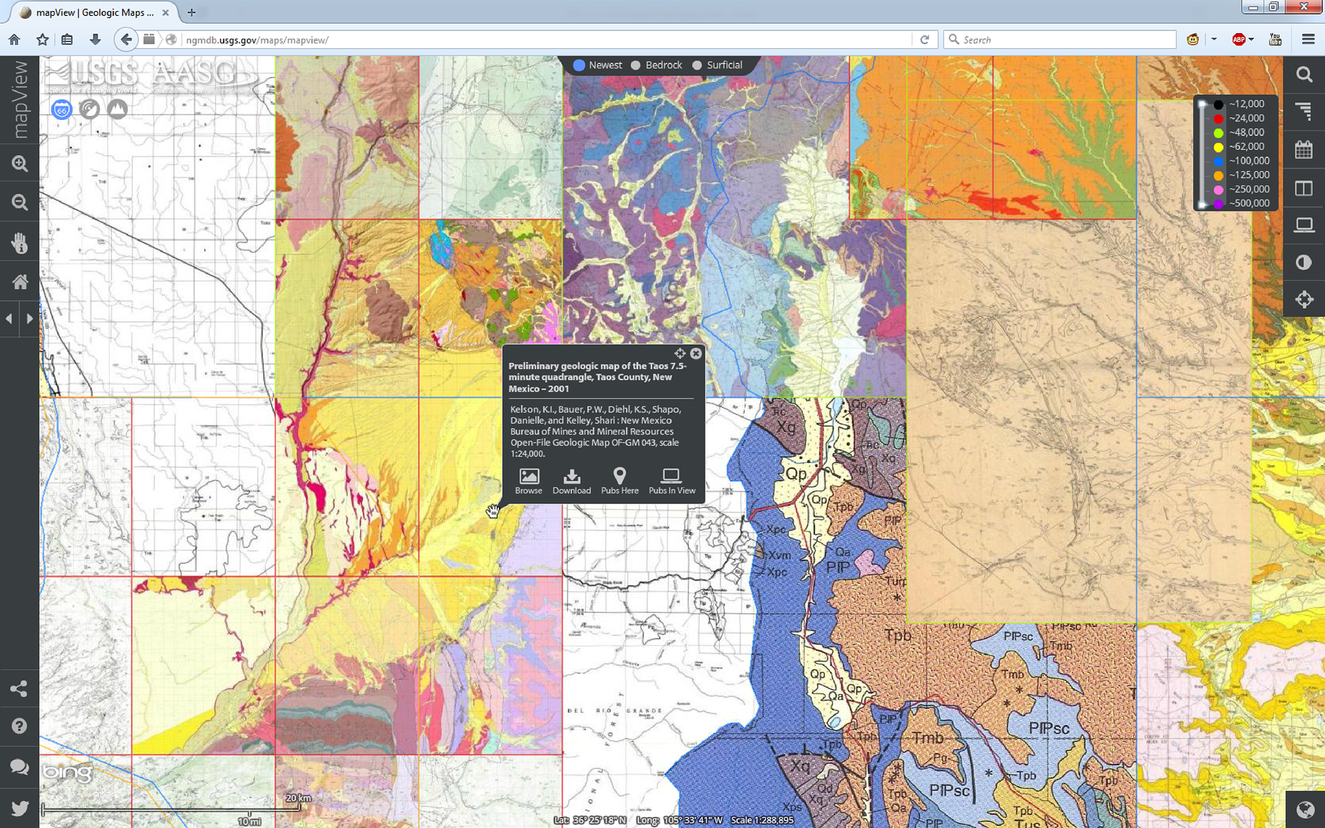

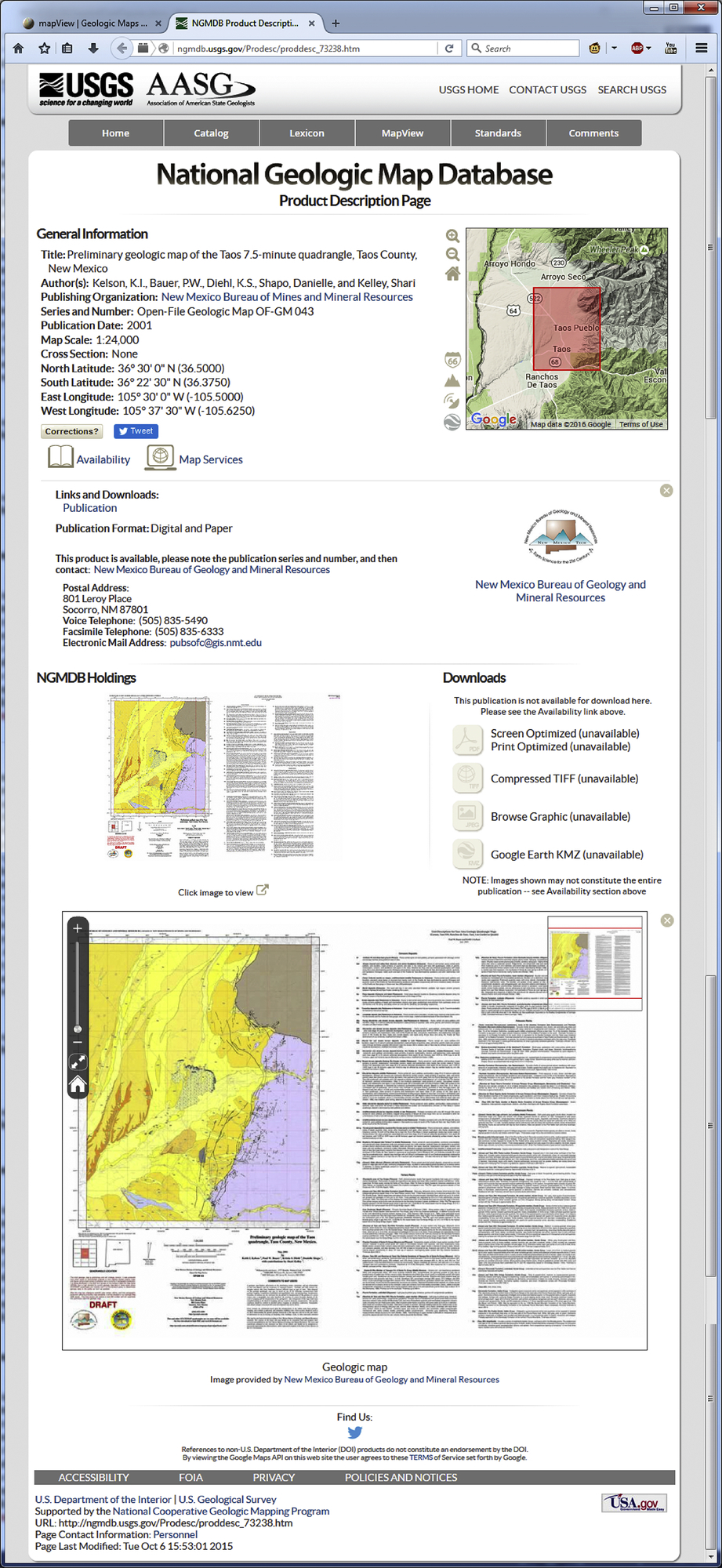

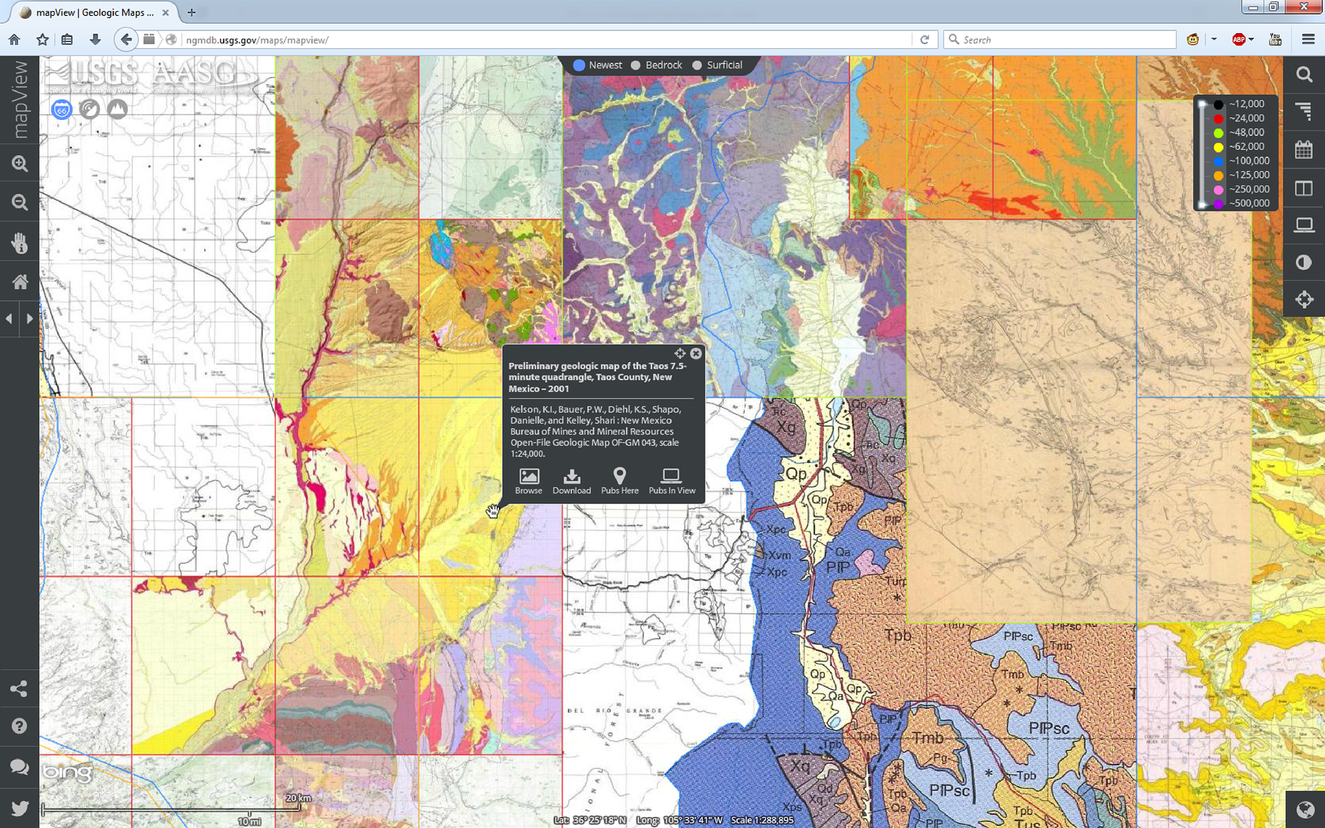

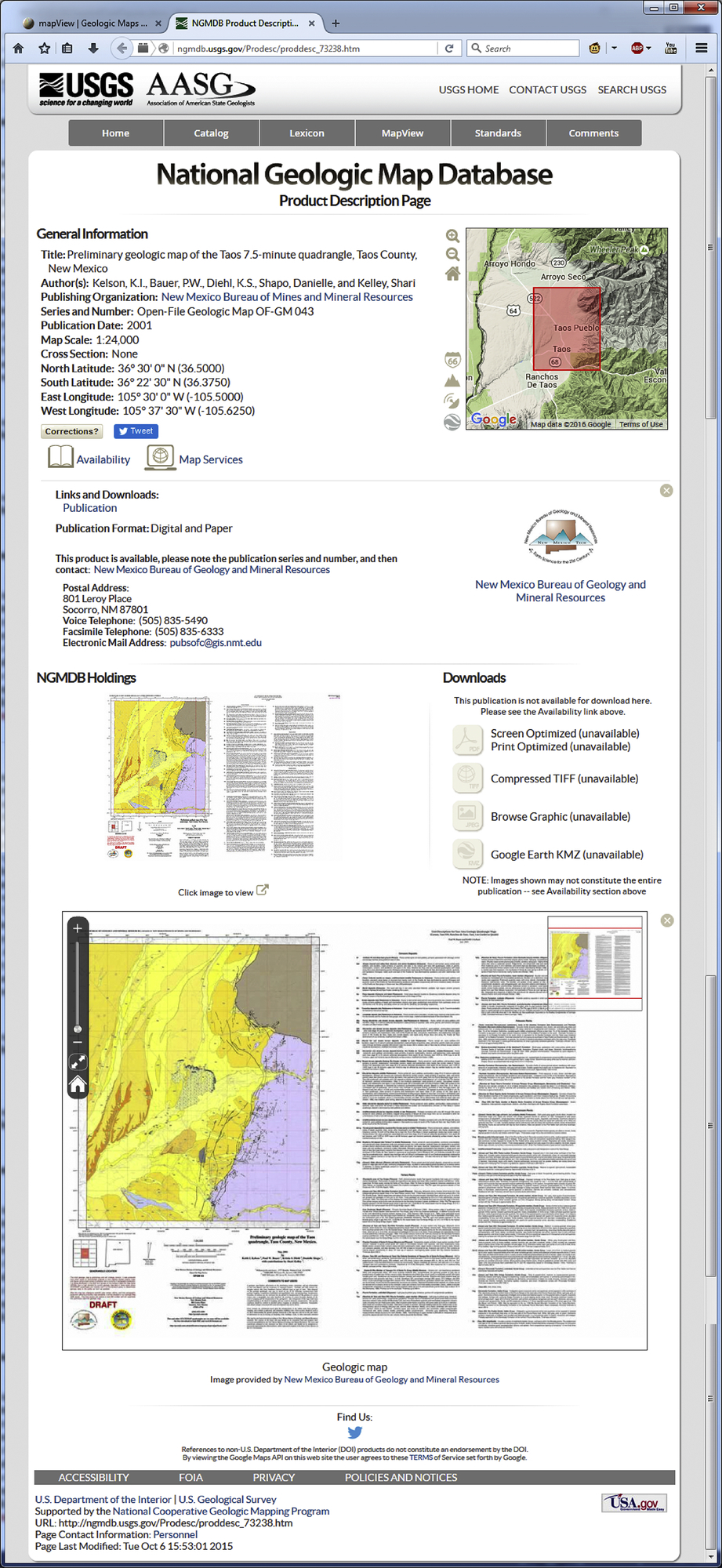

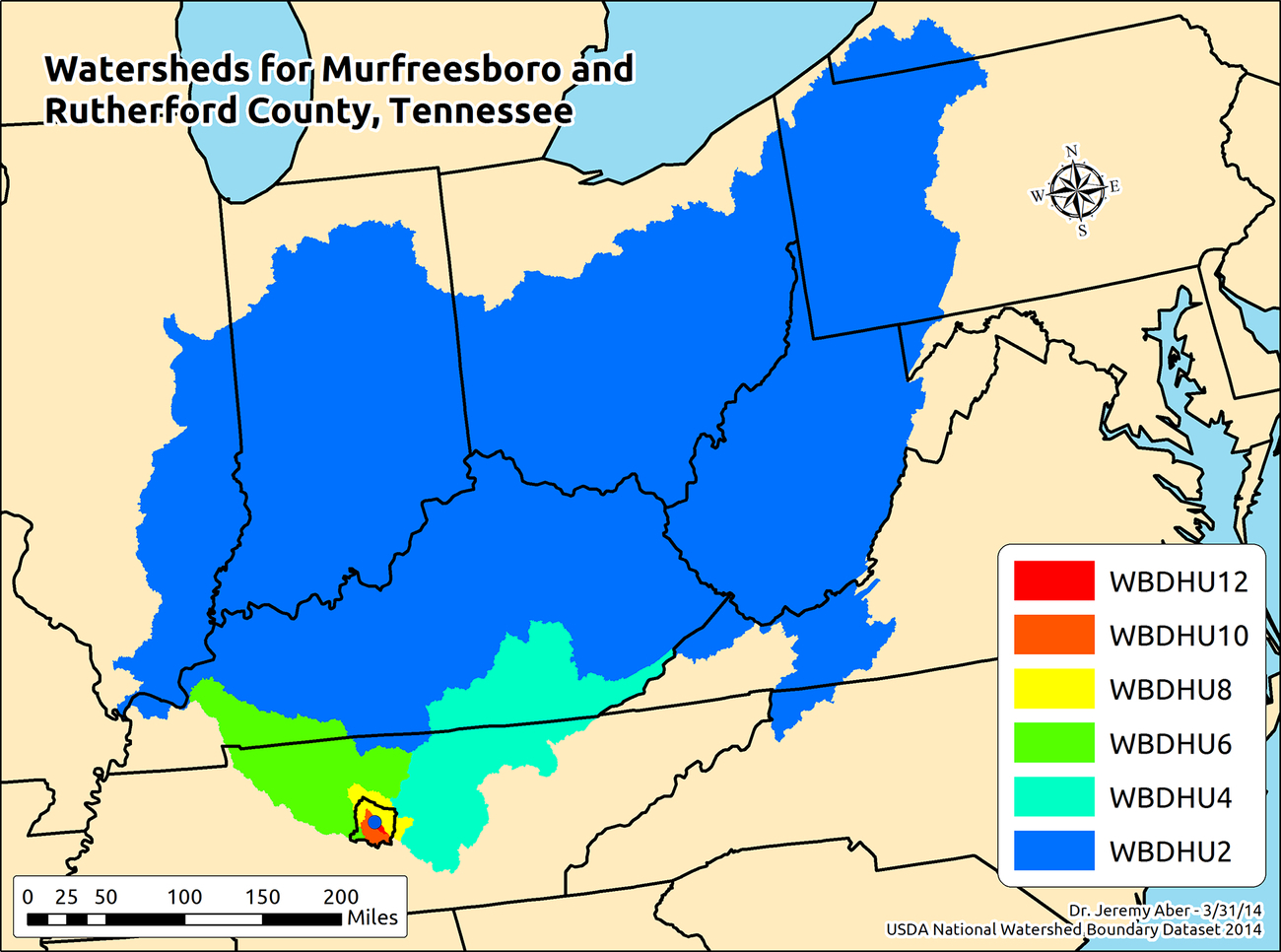

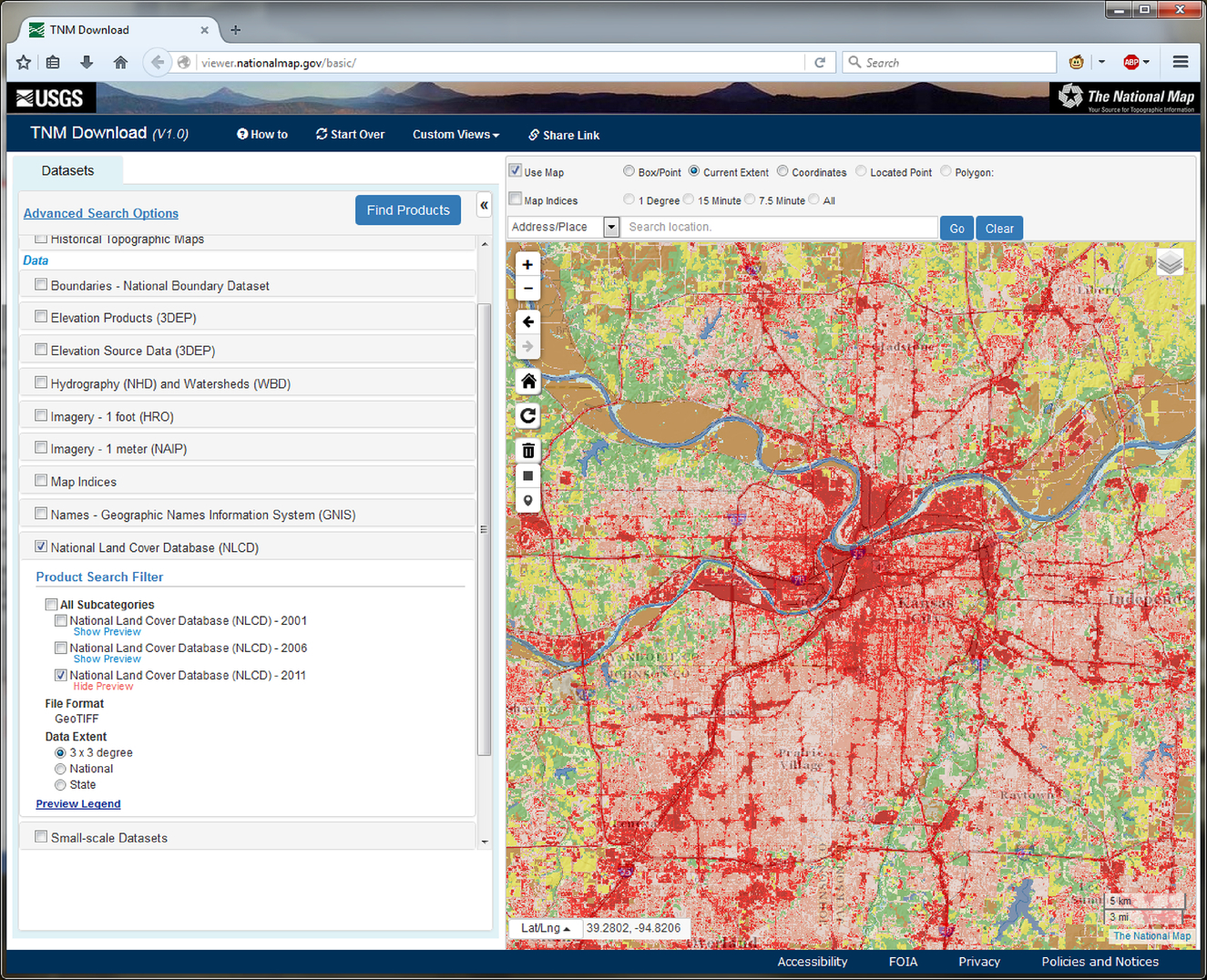

The USGS has standardized colors and geologic time symbols for maps of surficial geology according to age of strata so that a given geologic layer will have the same color and pattern across the map, keeping interpretation consistent. However, this scheme is not always followed at state and local levels for various reasons. The geologic maps available through USGS mapView are a patchwork of quadrangles, counties, and larger regions, with some portions missing (U.S. Geological Survey, 2016d). Maps of different vintages are juxtaposed, which leads to visual clutter and confusion, see Fig. 2.14. Component maps were created by various geologists using different working methods; in some cases they use different stratigraphic classification and terminology, which have changed through time. Cartographic style and graphic design also display conspicuous differences.

Coverage in mapView includes all western and central states, as well as Hawaii, but not Alaska. A few east-coast states, such as Florida and Virginia are included, but many other eastern states remain to be added. It is apparent that standardization of geologic mapping at the national level is a long-term goal that will take considerable additional effort to accomplish. Nonetheless, the current version is invaluable for public access to and display of surficial geology for many states using mapView from The National Geologic Map Database (NGMD) portal (U.S. Geological Survey, 2016e).

In the past, mining was largely unregulated and little attention was paid to long-term hazards or environmental consequences. Among the most highly polluted places in the United States is the Tri-State lead-and-zinc mining district, including Kansas, Missouri, and Oklahoma, which began operating in the 1850s, see Fig. 2.15. The last mines closed in 1970, leaving a legacy of serious soil and water pollution, poor economic conditions, and scarred landscapes (Manders & Aber, 2014). Such contamination led to the establishment of Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Superfund sites, and many federal and state agencies along with several universities and private foundations have cooperated for environmental investigations and remediation efforts.

Public interest in such sites is extremely high in many cases. As there is no one single repository of mining-related map information, map librarians should be prepared to conduct considerable research among diverse public, commercial, and private sources to locate relevant GIS databases and historical maps. A good example of this approach is the Tri-State Mining Map Collection at Missouri Southern State University, which is available in digital format at the Missouri Digital Heritage (2007–2014). The collection includes more than 5000 maps of all types related to past mining activities in the region, such as the mineral resource map shown in Fig. 2.15.

The phrase “historic map” brings to mind ancient maps of the world, or perhaps European maps describing explorations into unknown regions of the Americas. Despite this conception, we can consider any map that is not current to be an historic map. While they may or may not be old chronologically speaking, if they are not the most currently available version of the map information, they can be considered historic. This is a broad definition, but it avoids the subjectivity of individuals’ conceptions of the word historic. For example, USGS topographic maps were produced until 2006, but these maps are now considered to be a part of the Historic Topographic Map Collection. Even though these topographic maps are not particularly old when compared to the larger history of cartography, they do not reflect the most current knowledge, which is available today in the digitally updated US Topo Quadrangle series.

This is not to say that historic maps’ dated information makes them valueless. Given that maps typically represent knowledge of place at a specific time, historic maps can be an incredible record of the world. Library collections often include historic maps produced over many decades or even centuries. Whether they are months or centuries old, historic maps may contain knowledge not found in any other format, and are a valuable part of a collection. This is especially true of maps produced locally to describe the region or city where the collection resides. Unfortunately, maps that may not be considered old enough to be historic by the colloquial definition of the word are often discarded to free up space, destroying information that is quite possibly unique and found in no other collection.

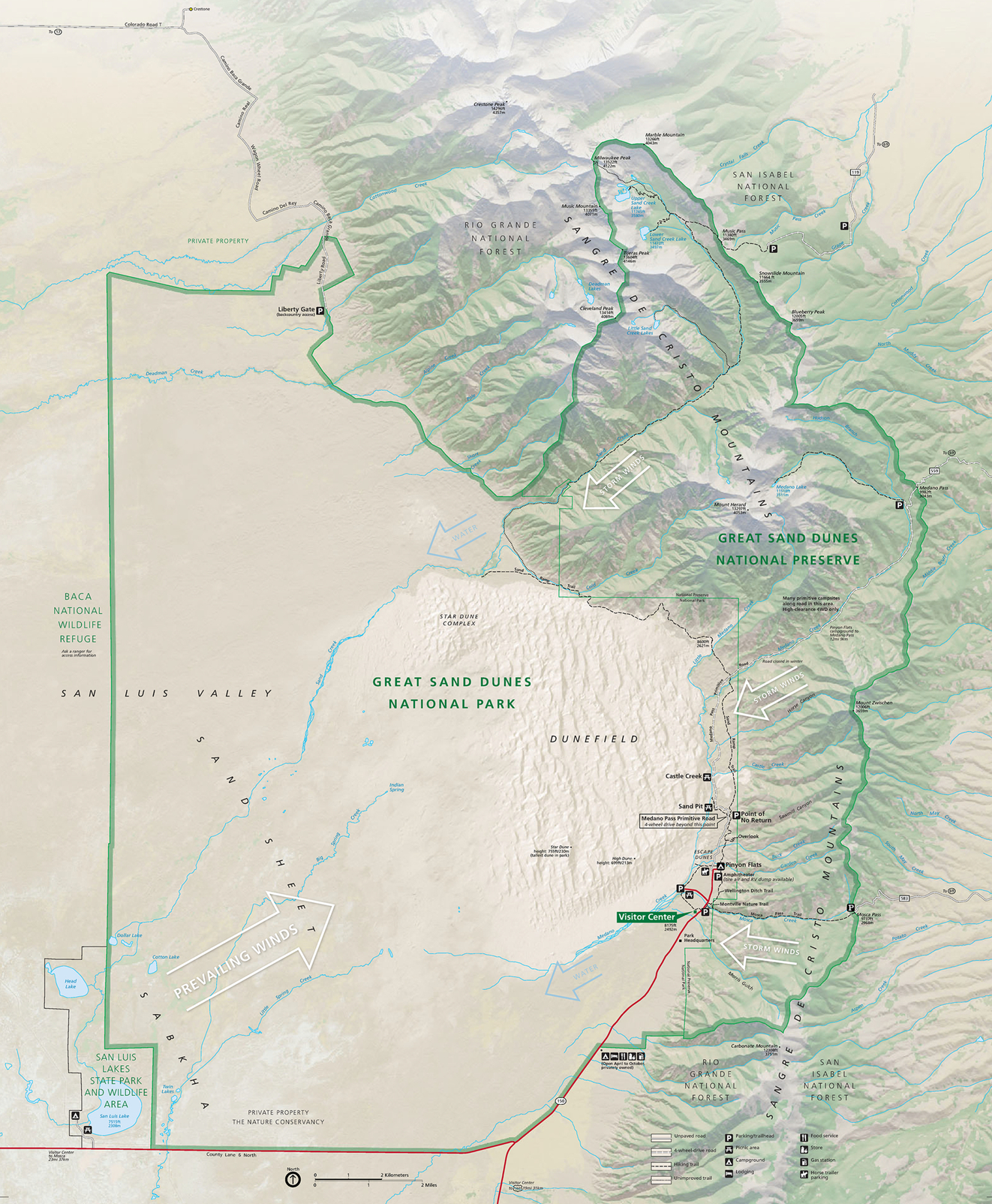

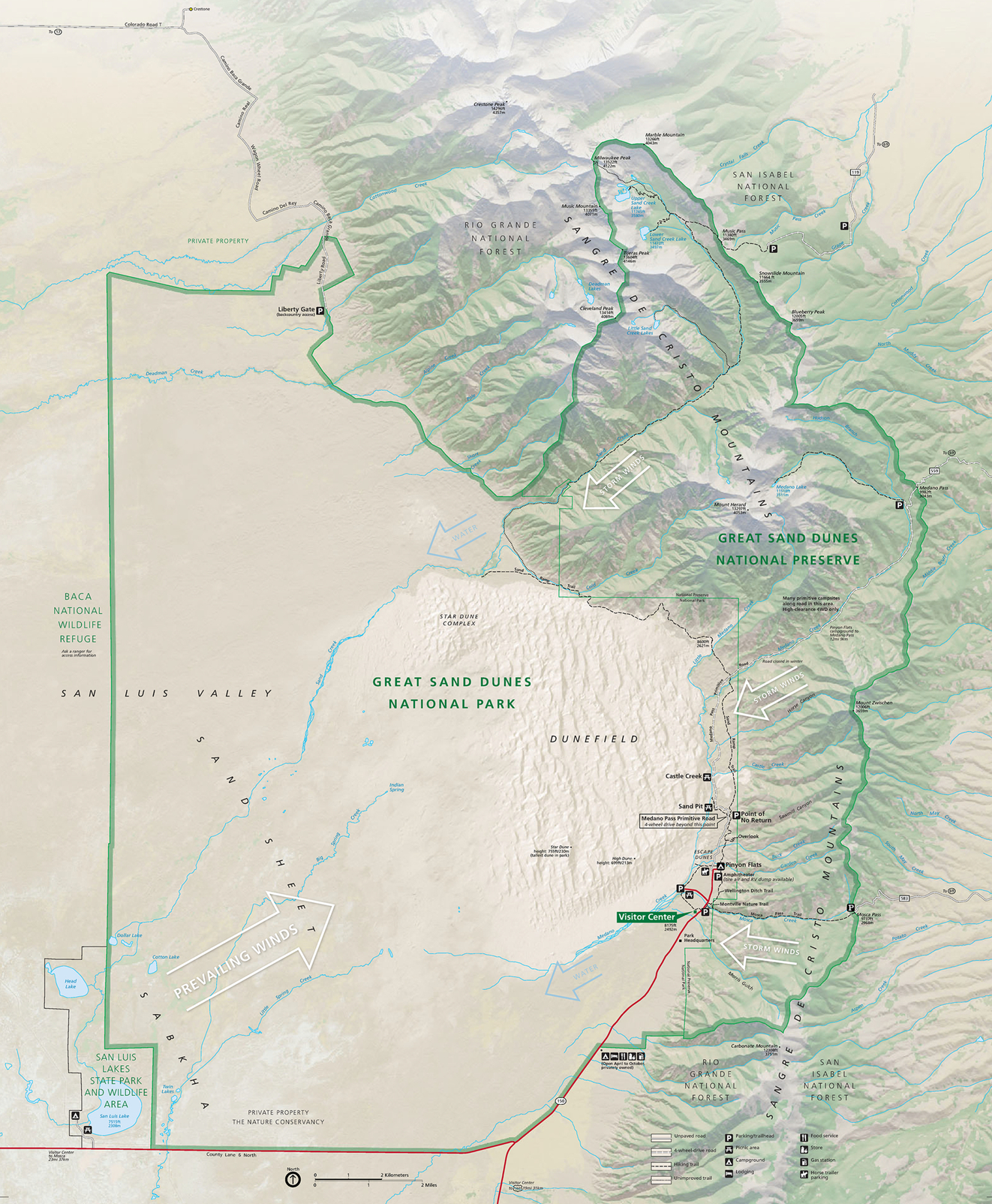

Maps representing U.S. National Park Service (NPS) lands exist in multiple formats, but the most prominent is the topographic map created by the USGS. These maps are similar to the standard USGS topographic maps, but they have a special focus on the features related to national parks. Since there are large size differences from one park to the next park, the corresponding maps range in scale from large to small, 1:960–1:250,000. The largest scale map represents the Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site in New York and the smallest, Denali National Park in Alaska (U.S. Geological Survey, 2005). Fig. 2.16 shows an example of one of these maps representing Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado. USGS topo maps of National Parks can be purchased or downloaded through the USGS online store (U.S. Geological Survey, 2012a).

The NPS also produces service maps for each park, monument, and trail in the system. Rather than terrain, these maps are designed primarily to aid in navigation and general reference for visitors. The NPS recommends using USGS topo maps for outdoor activities such as hiking and mountaineering. Service maps are produced using a variety of data sources and cartographic techniques, although more recent maps are produced using GIS data sources and digital cartography techniques (National Park Service, 2016a). Since each park has different attractions, these maps cater to site-specific needs, including features such as parking and visitor’s center locations. An example of one of these service maps showing Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve in Colorado can be seen in Fig. 2.17. Service maps for individual National Parks, National Historic Sites, and the National Trails system can be found at the NPS’s website (National Park Service, 2016b).

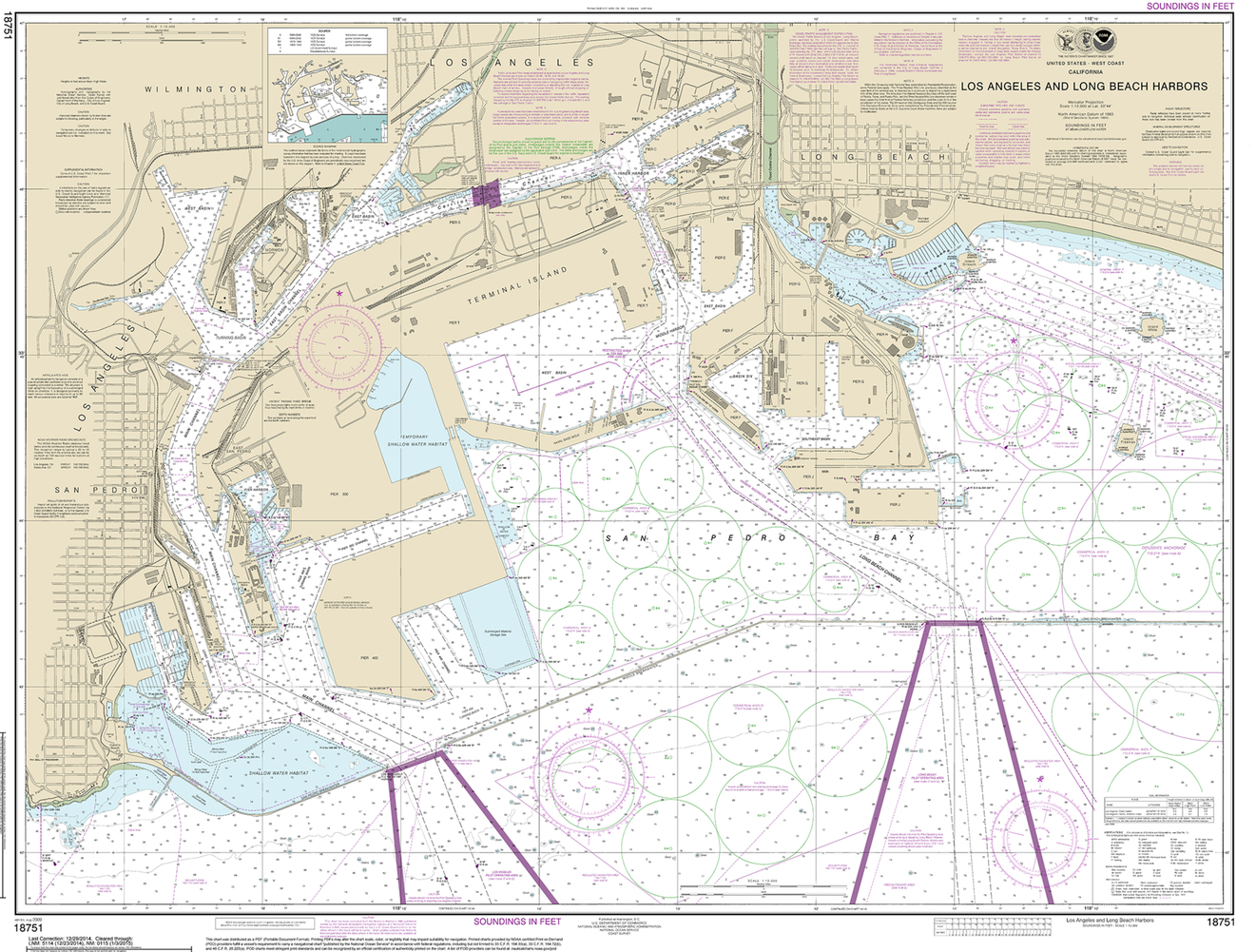

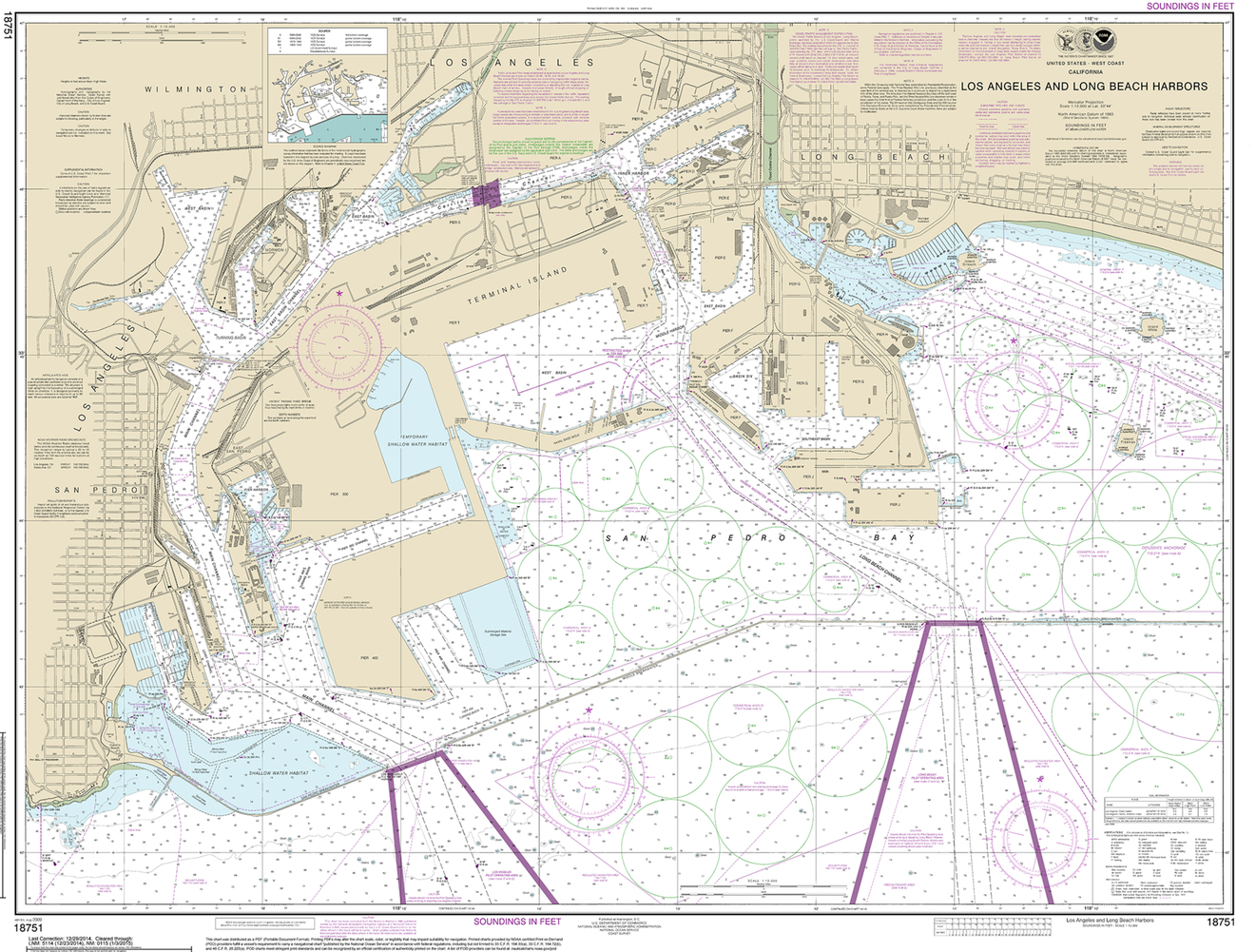

Nautical charts have been used for centuries to assist sailors in maritime navigation. Modern charts often include water depth, local magnetic declination, paths for entering and exiting harbors, and structures such as piers and relevant buildings. In the United States, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) produces both digital charts as free downloads or paper editions for purchase (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, n.d.). The agency has its origins in the United States Survey of the Coast, founded in 1807, and although today’s NOAA has changed quite a bit, the Coast Survey continues to produce weekly updated nautical charts for maritime use (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2012). Types of maps produced include sailing charts for navigation in open coastal water, general charts for visual and radar navigation by landmarks, coastal charts for nearshore navigation, harbor charts, and other specialized chart types for various sailing uses (Thompson, 1988). An example of a modern nautical harbor chart showing the Los Angeles and Long Beach harbors can be seen in Fig. 2.18.

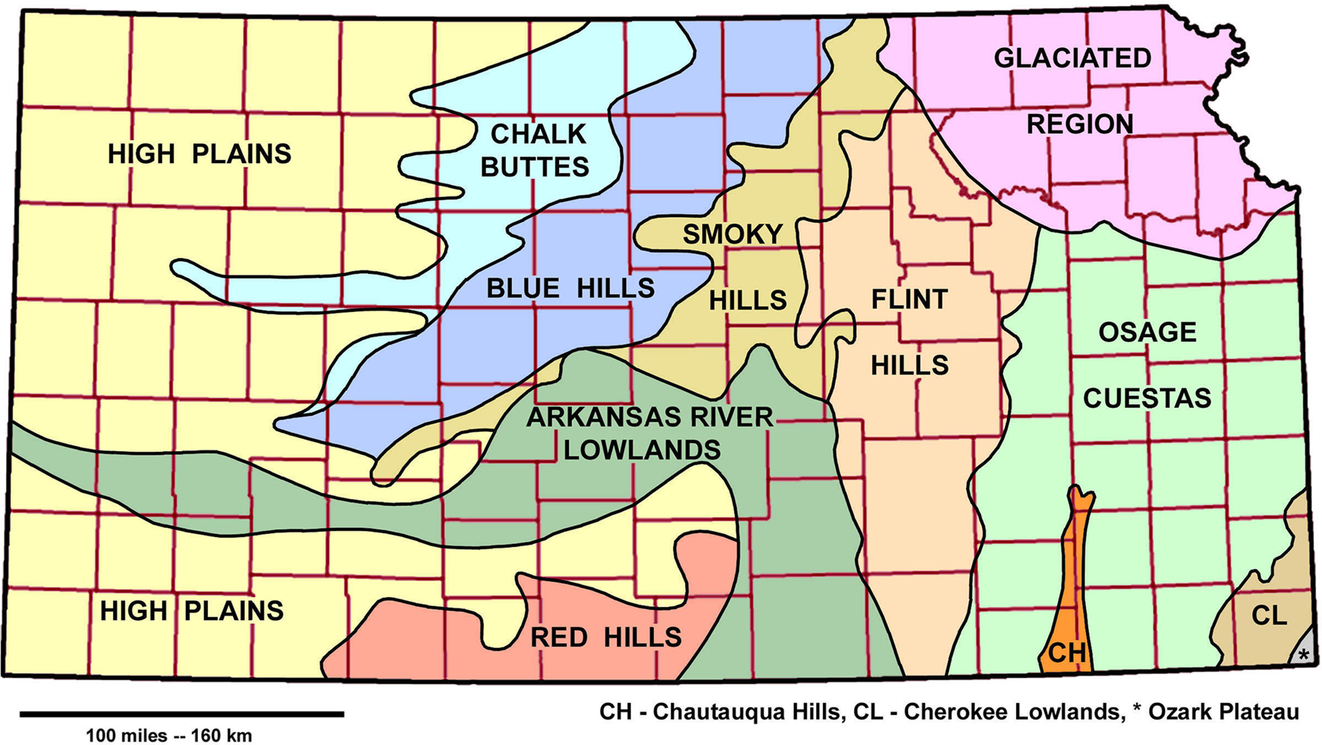

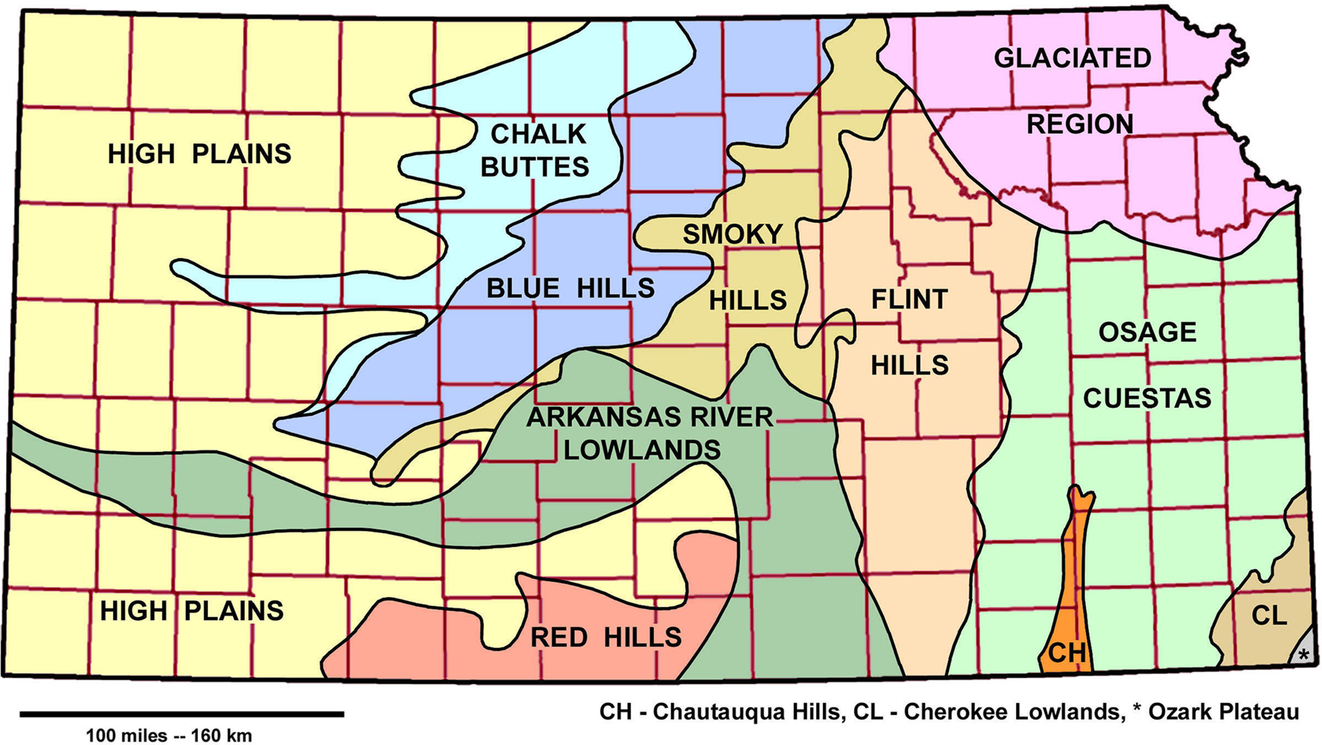

Physiographic maps show generalized regions based on shared land forms rather than vegetation or other factors. Many physiographic boundaries are therefore based largely on the underlying geology of a region. The general system in use today for classifying these regions was laid out in “Physiographic Subdivision of the United States” and has three orders referred to as major divisions, provinces, and sections (Fenneman, 1916). A modern example of a physiographic map showing generalized regions of Kansas can be seen in Fig. 2.19.

Planimetric maps are any maps that show the horizontal positioning of ground features without representing elevation information. These maps are used for a variety of purposes, including base or outline maps, cadastral maps, and line-route maps (Thompson, 1988). Base maps include features such as roads, waterways, or political boundaries that are used as a base, or background, for the presentation of other data. Outline maps are similar, but are generally limited to features such as political or physical boundaries. For example, many thematic maps include base map information, such as county boundaries or highways in addition to their thematic map content. See Fig. 2.4 for an example of a thematic map that involves county boundaries as a base. Cadastral maps represent the division of land for the purposes of ownership. These maps, including plats, are commonly used for legal descriptions of land ownership, as well as taxation purposes. Line-route maps are similar to base maps, but they are specific to utilities, representing the locations of all manner of pipes and cables, along with the facilities that support these vectors of transmission. A good example that can be used to map anything to do with energy, from electric transmission lines to hydrocarbon gas liquids pipelines, is the U.S. Energy Mapping System (U.S. Energy Information Administration, n.d.).

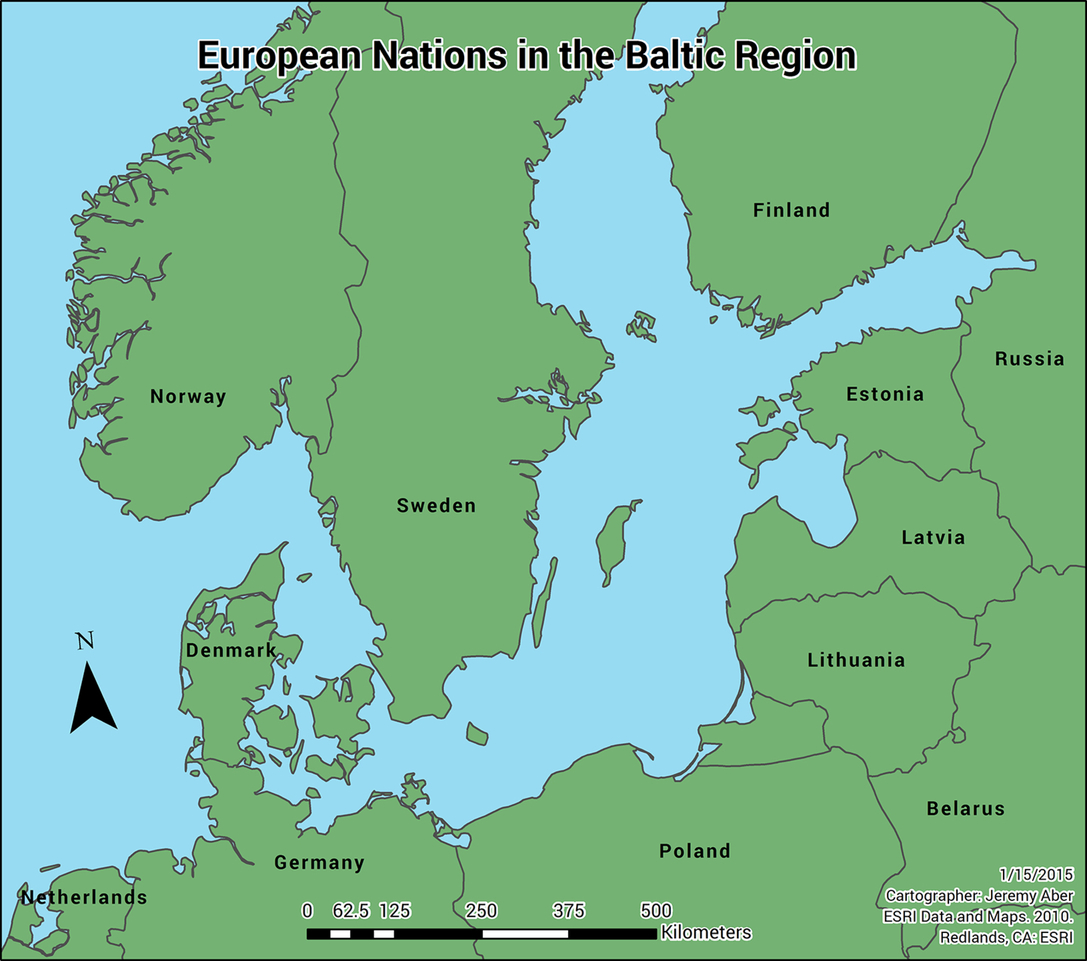

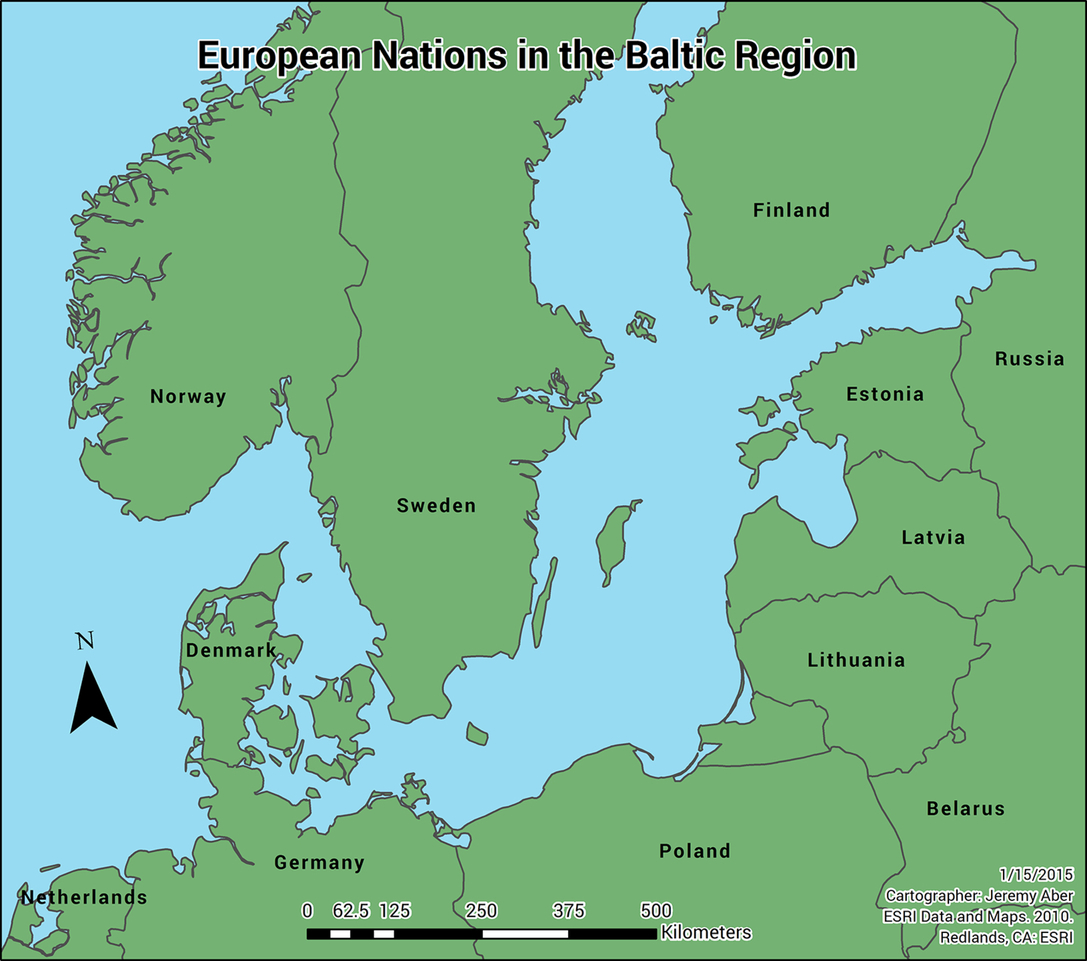

Political maps focus on the administrative boundaries defining nation-states and other political regions, internal political divisions, and the locations of cities. They may contain other information, such as natural features like rivers and mountains, but the primary focus is on political borders. An example of a simple political map showing national borders can be seen in Fig. 2.20. Political maps often act as base maps, giving context to natural and cultural phenomena that overlay the political information. In an educational context, they may take the form of traditional classroom pull-down wall maps.

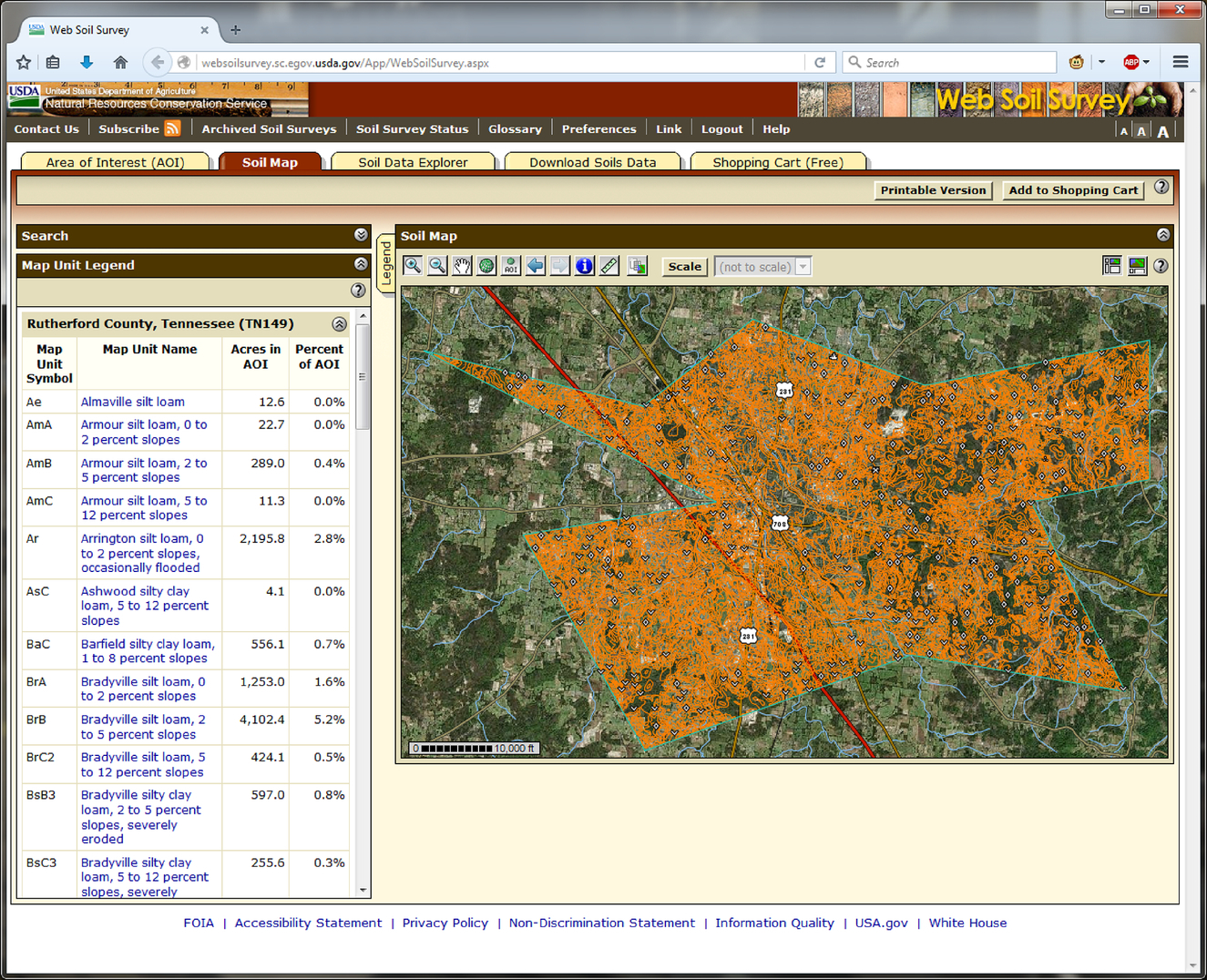

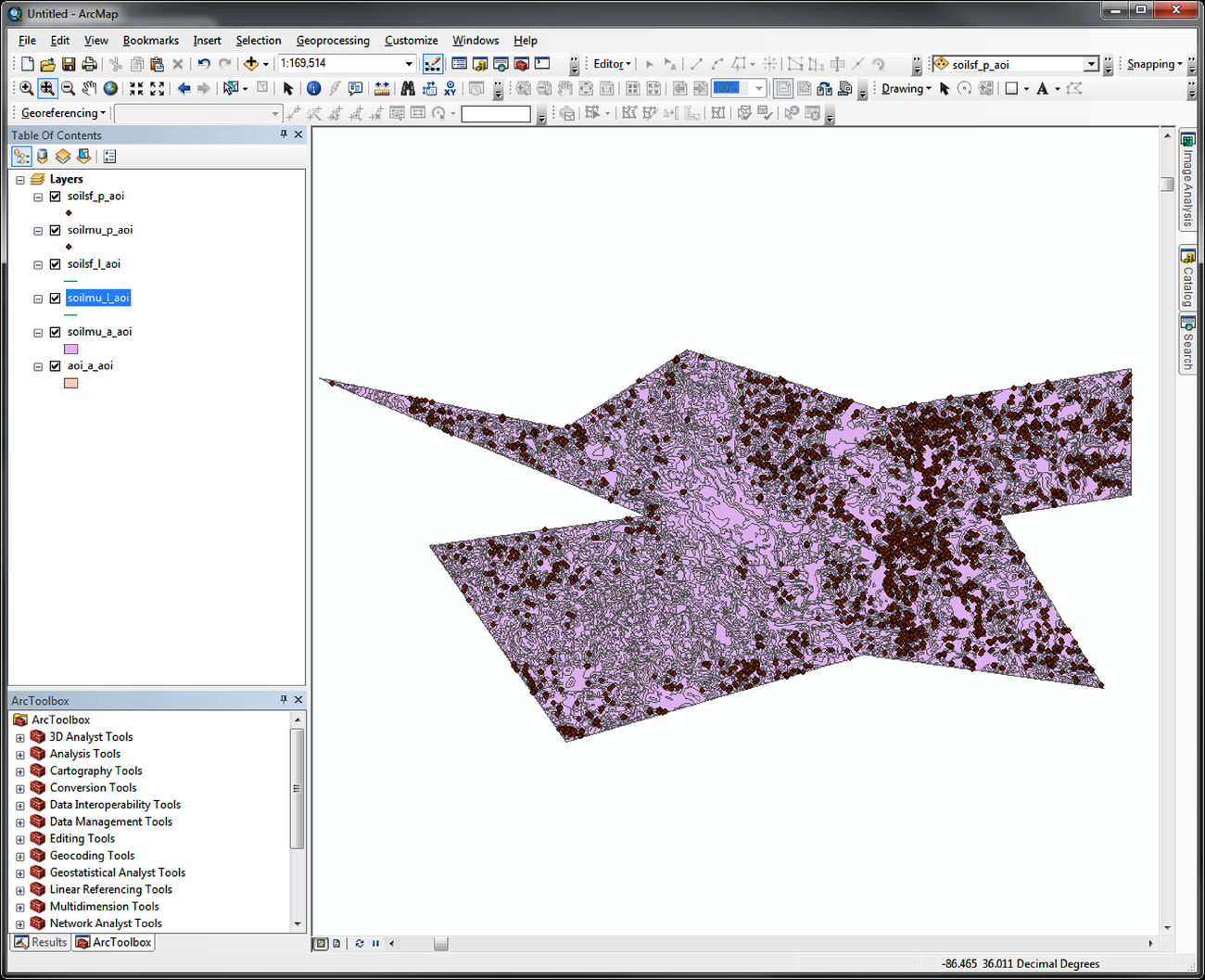

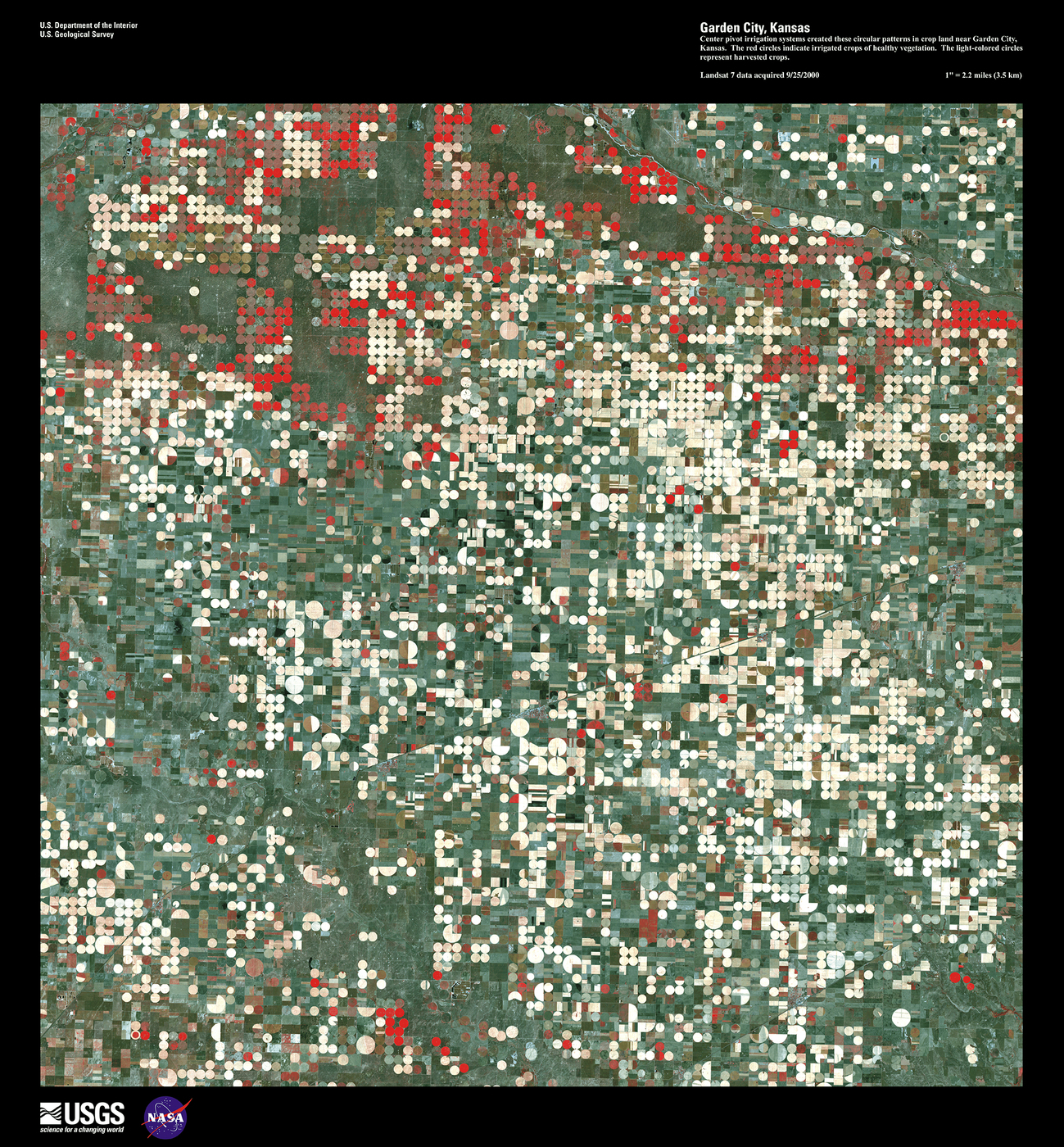

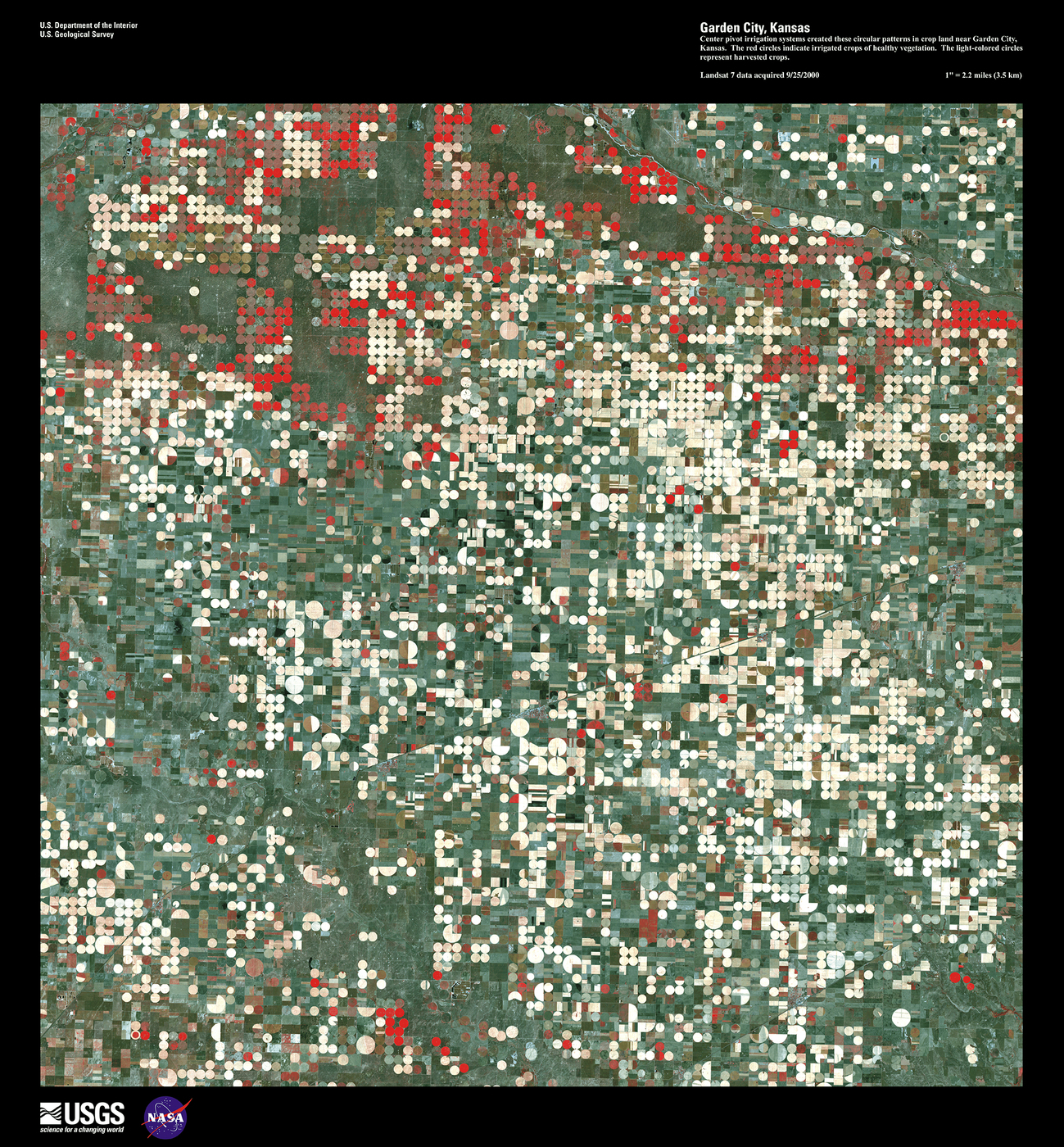

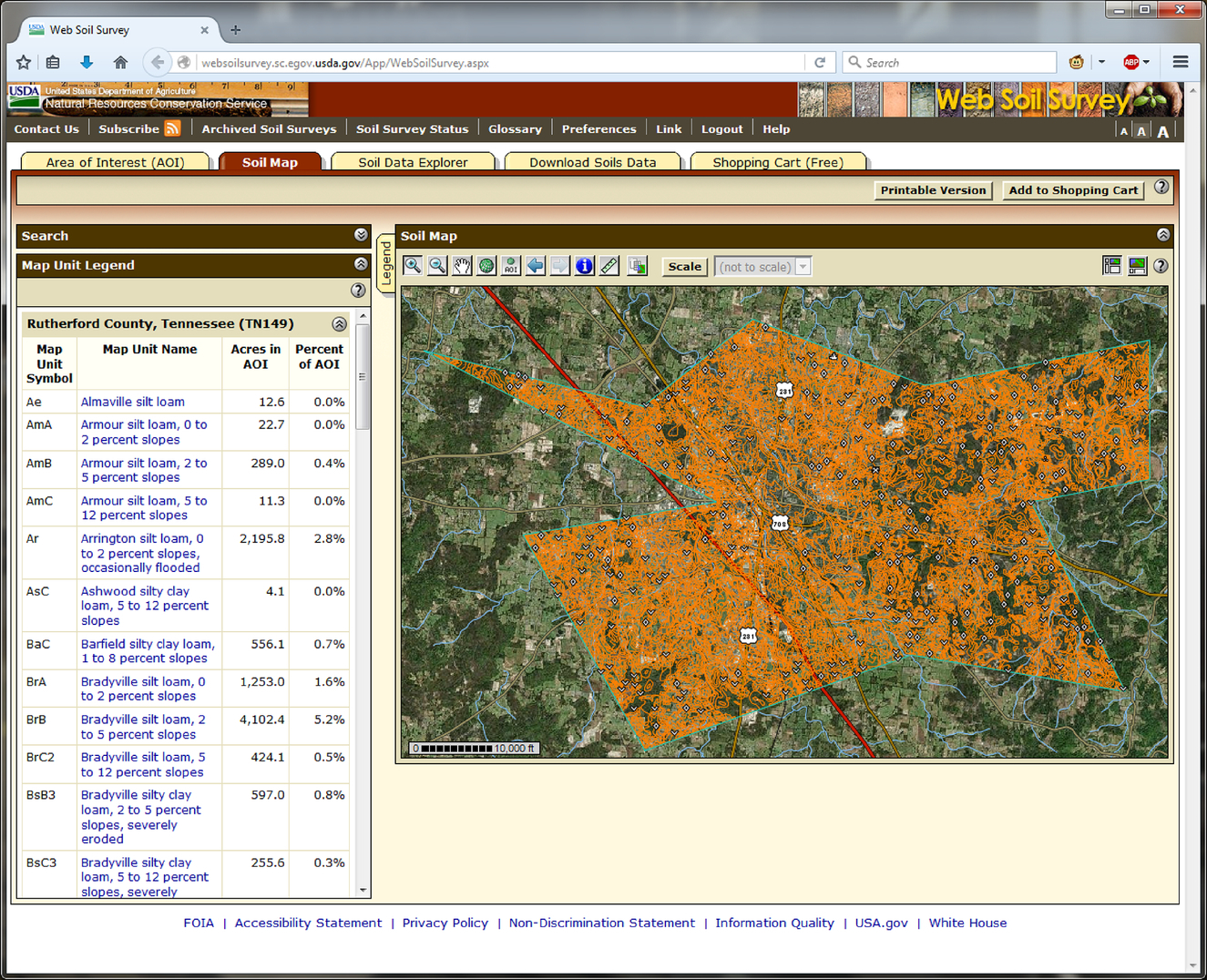

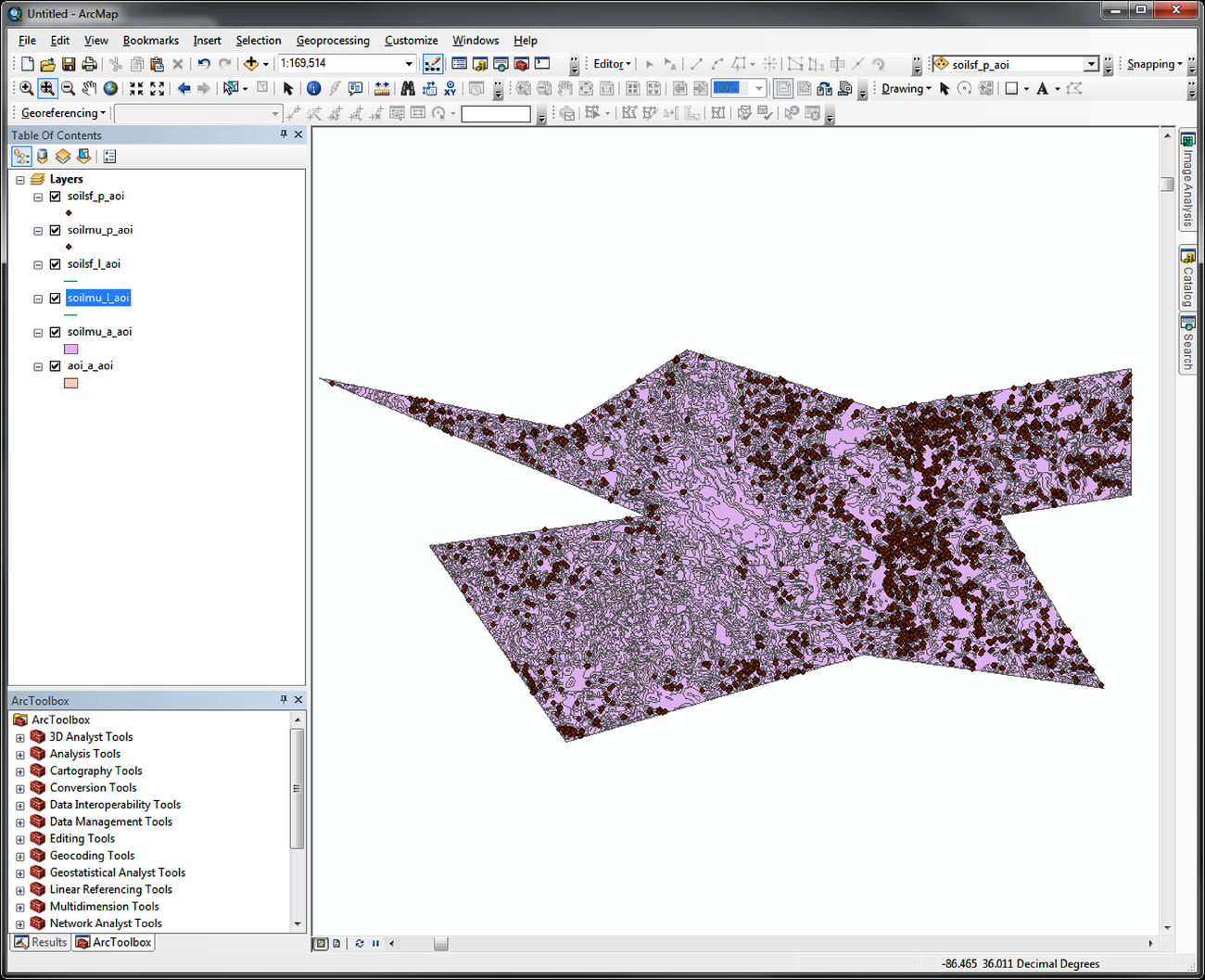

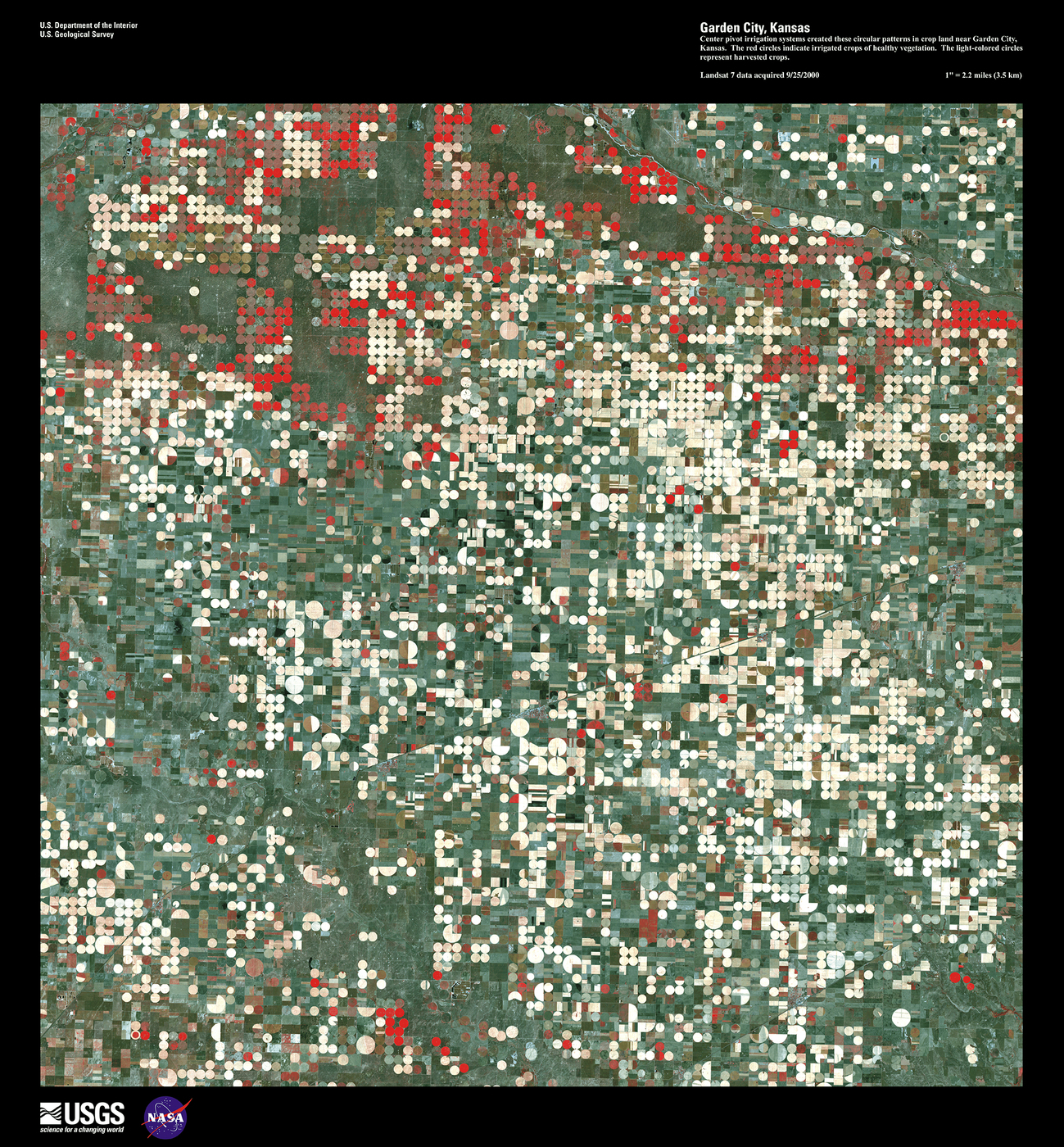

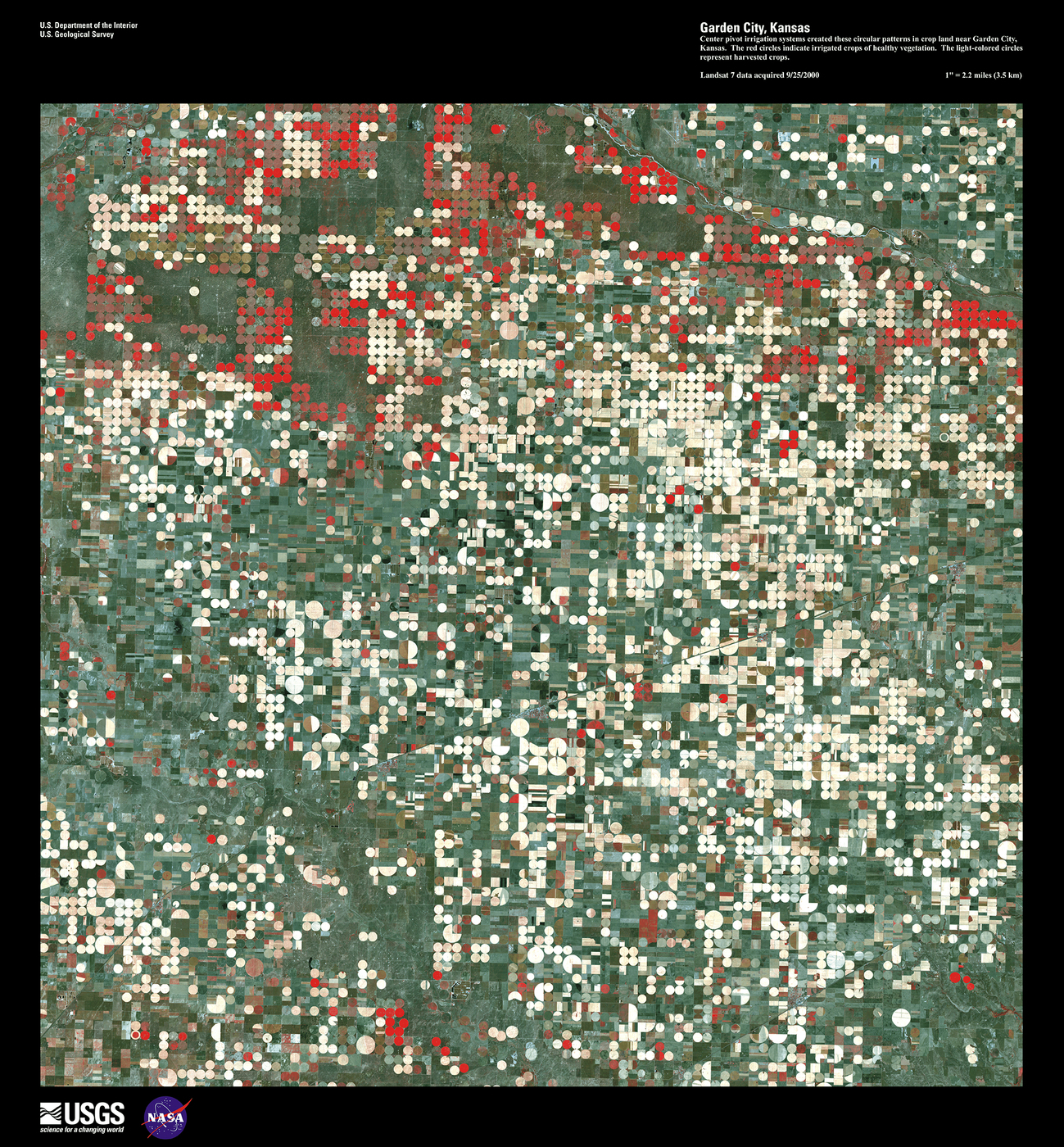

Soil maps are one component of a general soil survey, and they show the location and nature of different types of sediments on the ground. Soil surveys began in 1899 under the title of the National Cooperative Soil Survey; today the Soil Survey is under the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service division. Paper maps included soil regions marked on top of aerial photographs, an example of which can be seen in Fig. 2.21. These maps were just one component of a regions’ soil survey, which could be more than 100 pages of detailed information about the soil, its composition, and what this meant for various agricultural practices. Today, these historic documents can still be accessed through the NRCS website, but more up to date information is downloaded through the Online Web Soil Survey (Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2013). This interactive map interface allows users to generate custom soil maps for their specific needs.

A topographic map is any map that represents horizontal planimetric data in combination with a representation of vertical elevation data. There are multiple approaches to representing elevation in maps, but contours are the most commonly used technique today. See Fig. 2.8 for examples. Topographic maps are generally considered reference maps, as opposed to thematic maps, and are distinct from planimetric maps, which do not include relief information (Jones et al., 1942). These maps are used for many purposes related to the natural world, including recreation activities such as hiking, hunting, and fishing, but they are also used for activities like highway and utility development, construction planning, and flood management.

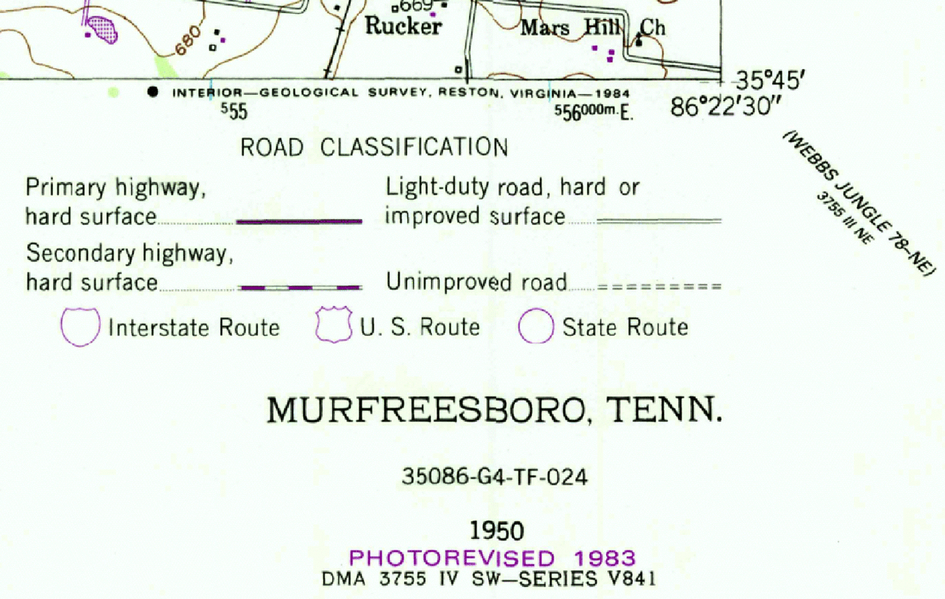

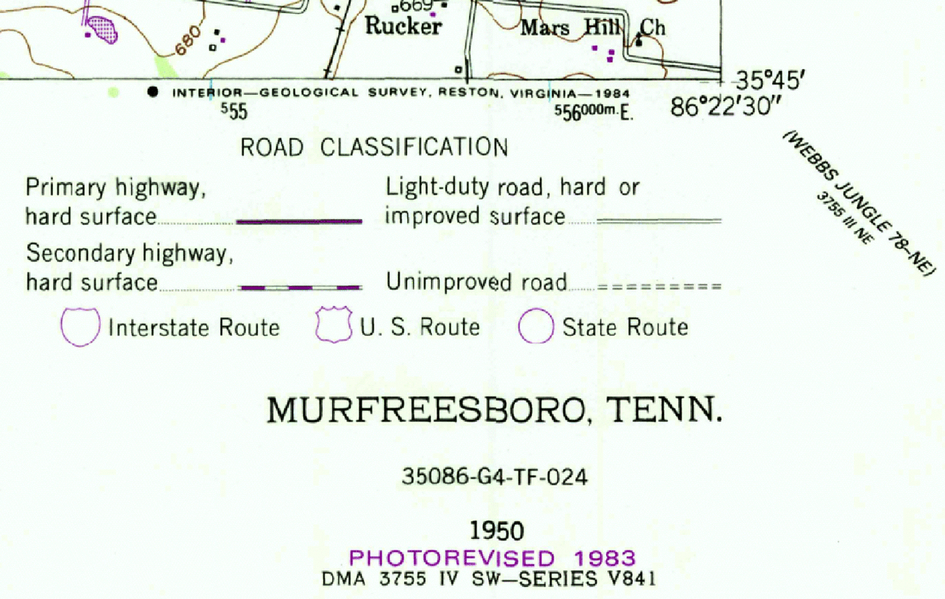

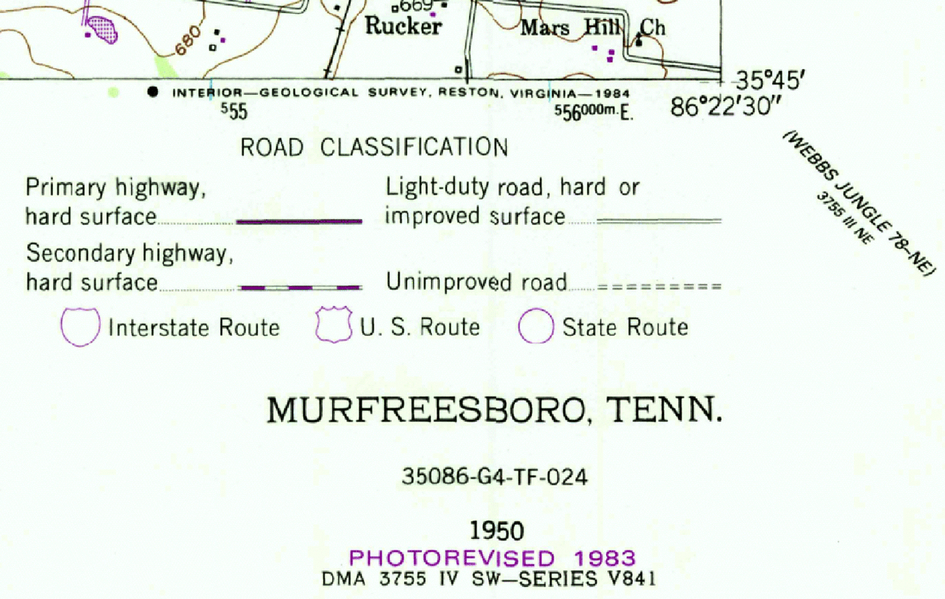

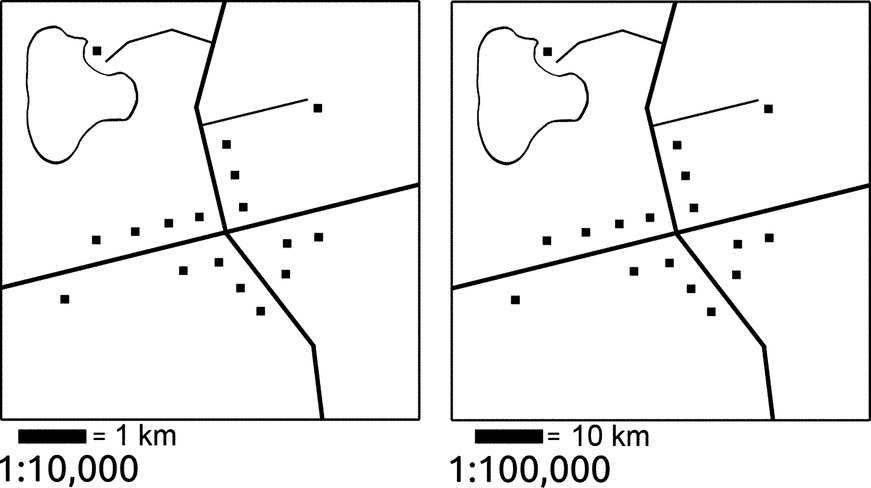

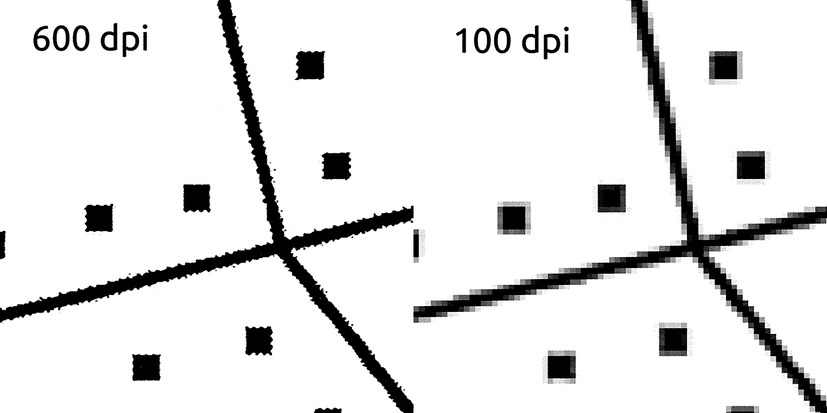

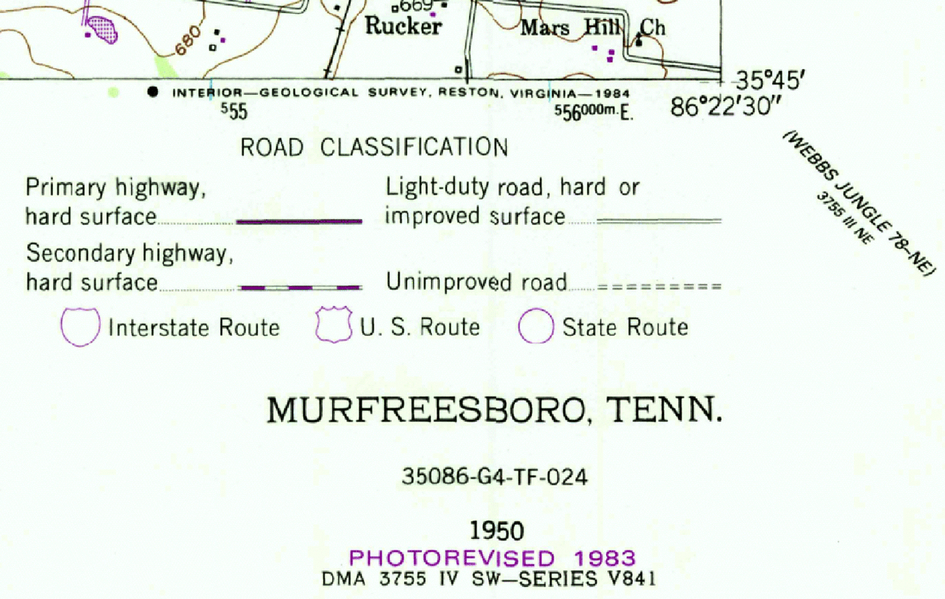

While many nations have mapping programs that create topographic maps, the most well-known series in the United States are produced by the USGS in a program stretching back to 1884 (Usery, Varanka, & Finn, 2013). While the technologies used to produce and distribute the maps have changed over the years, the basic map content remains more or less the same as it was in the late 1800s. After decades of labor, the original series of 7.5-minute topographic maps was declared complete in 1992 (Moore, 2011). Following the 1992 completion of the series, digital GIS approaches to mapping have been the focus of the program. Topo maps were produced with print as the target medium until 2006, and today these older paper maps are now referred to as the Historic Topographic Map Collection (HTMC). Since 2006, all new maps have been produced in a native digital form in what is known as the US Topo Quadrangle series (U.S. Geological Survey, 2016f). Hardcopy prints of this newer series can still be purchased through the USGS store, but the emphasis rests on distributing the maps digitally. Both digitized copies of the HTMC and US Topo Quadrangles are freely available for download through the Map Products at the USGS Store (U.S. Geological Survey, 2012b), The National Map Viewer (U.S. Geological Survey, n.d.), and The USGS topoView interface for current and historic maps (U.S. Geological Survey, 2016g).

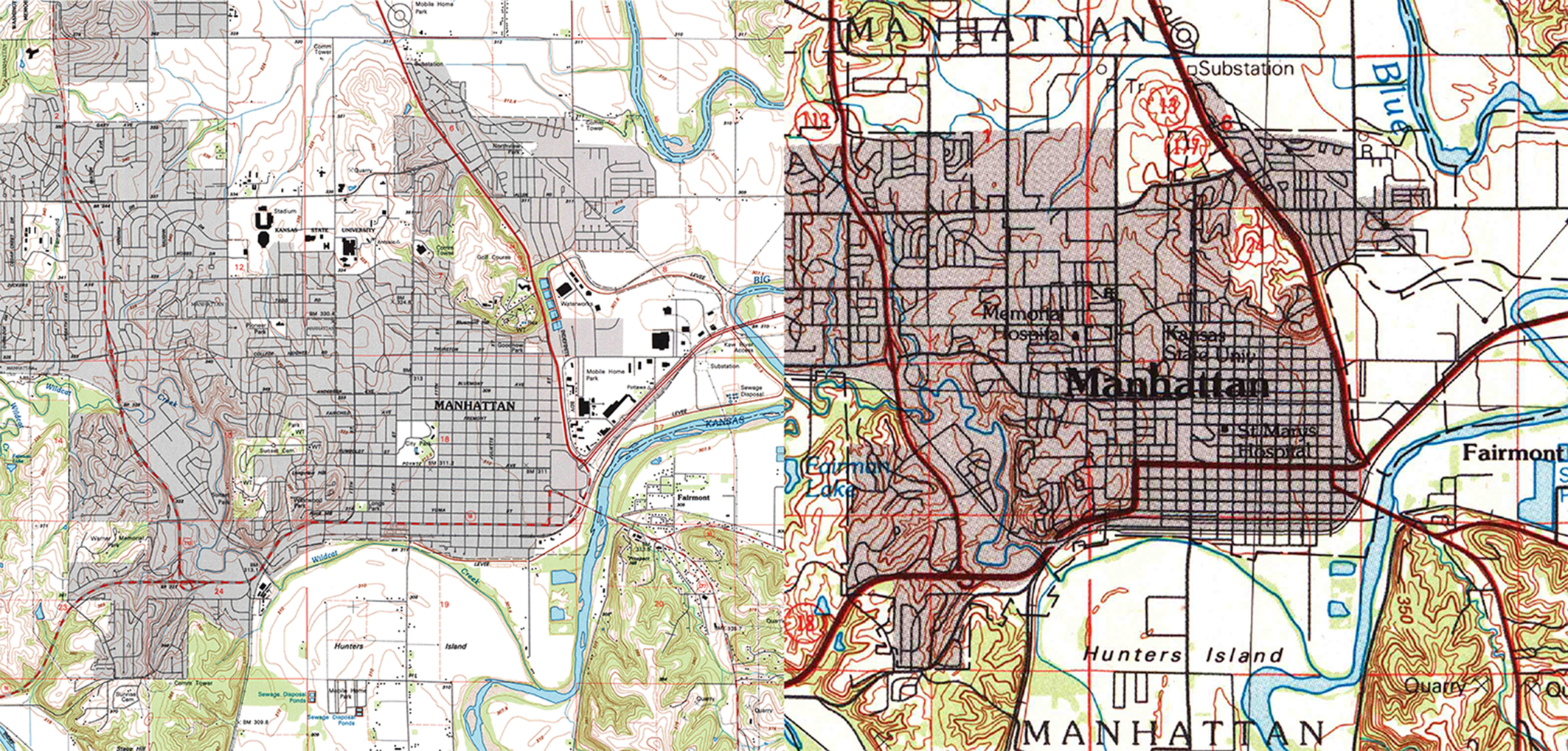

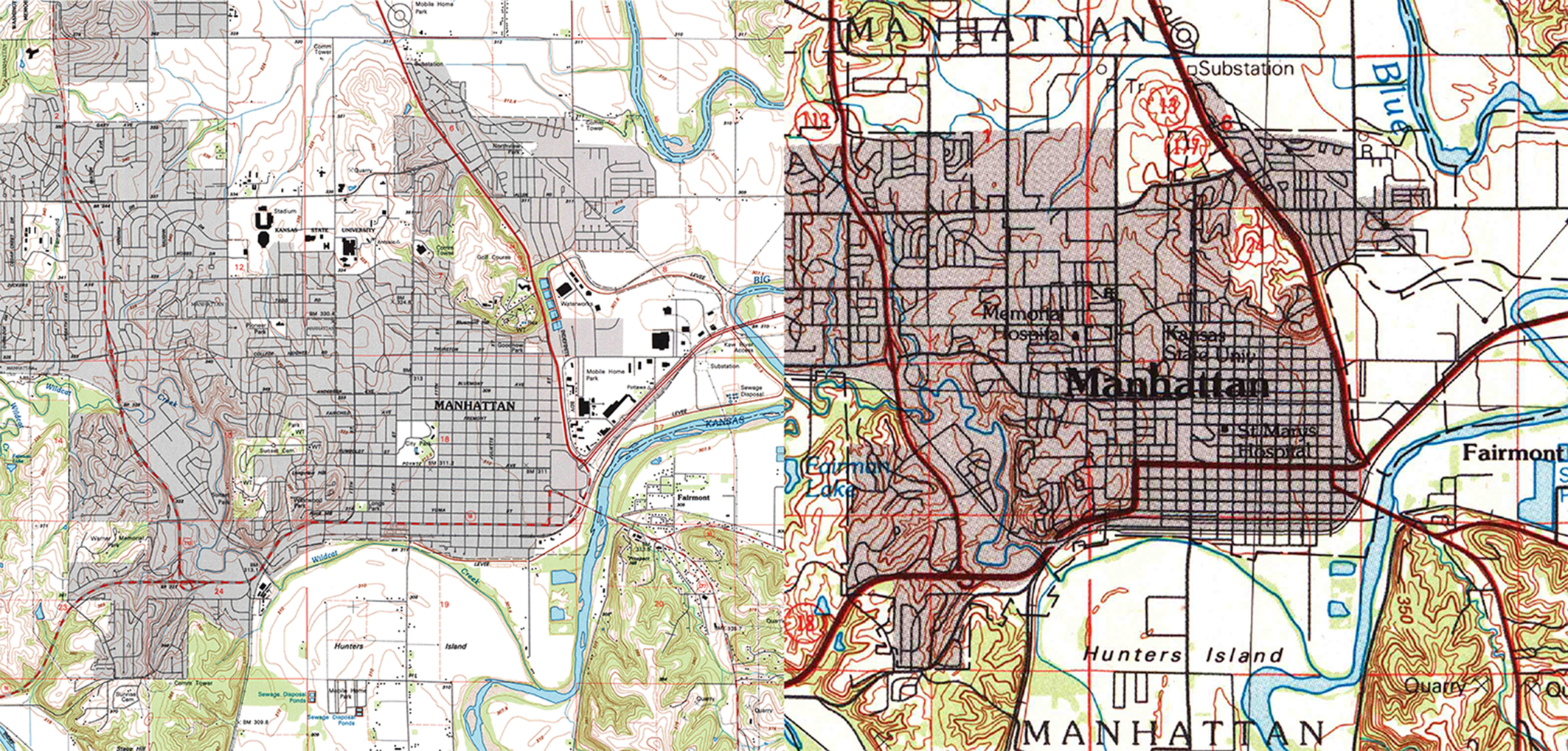

There are differences between the two USGS topo series beyond their medium of distribution. Maps in the newer Topo Quadrangle series lack some of the information that was routinely presented in the HTMC maps, including features such as “recreational trails, pipelines, power lines, survey markers, many types of boundaries, and many types of buildings” (U.S. Geological Survey, 2015e). The reasoning behind these omissions is that USGS no longer verifies these features in the field, and as of 2016 no other current GIS data source exists to fill the gap. As data for these types of features becomes included in The National Map, it will be added to the Topo Quads. Two topo maps can be seen in Fig. 2.22, one showing an older HTMC version of the information, the other the modern Topo Quad version.

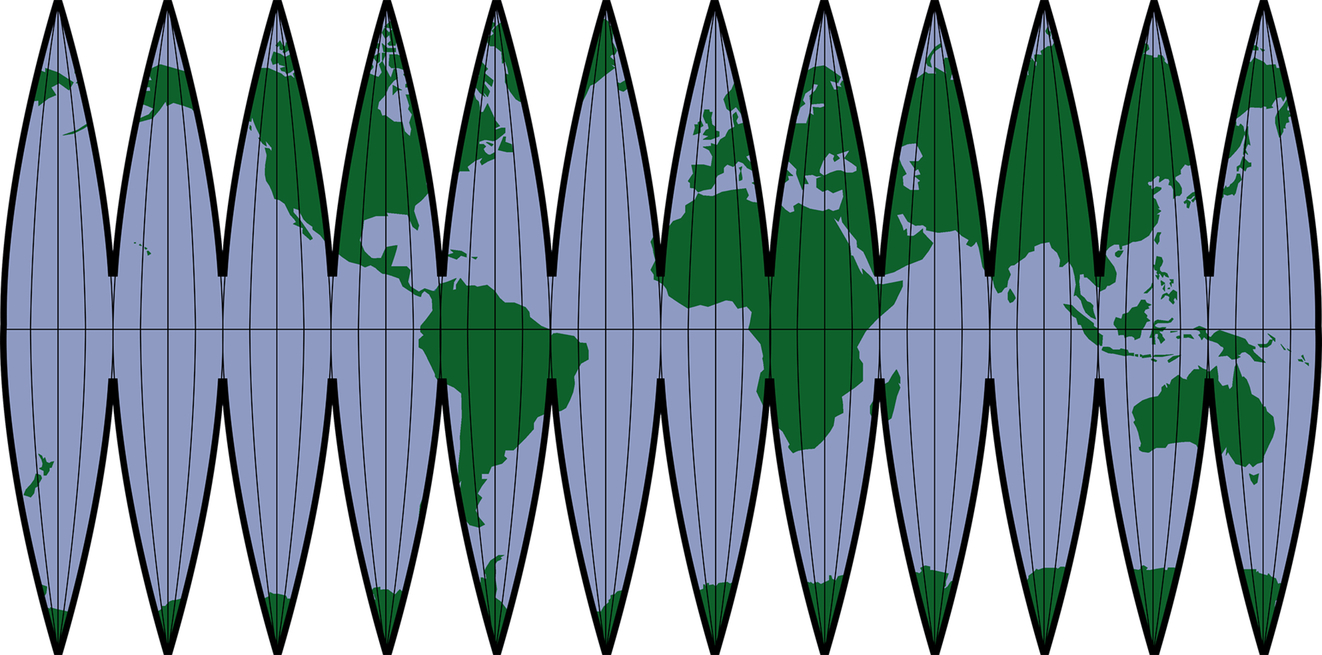

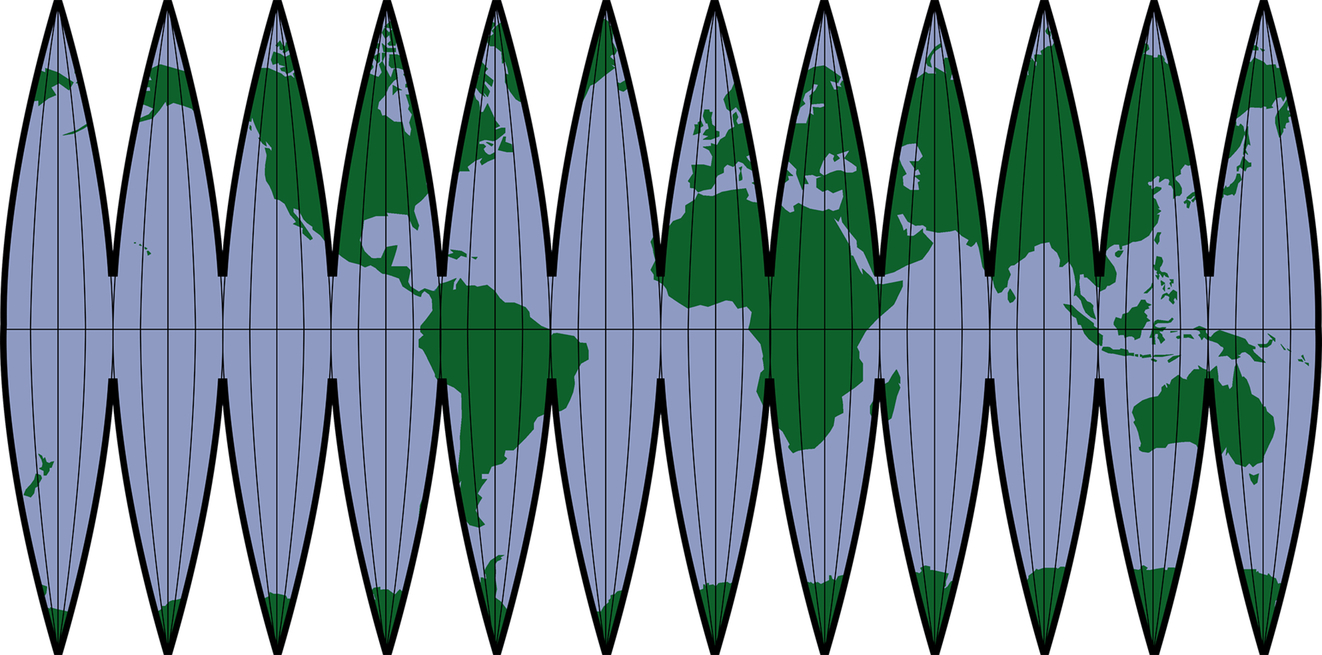

Globes have been made for thousands of years, as evidenced by the fact that the ancient Greek geographer Strabo discussed the use of globes some 2000 years ago in his Geographica (Strabo, 1903). Most globes have not survived the years in physical form though, and our oldest surviving globe was created by Martin Behaim in 1492 (Menna, Rizzi, Nocerino, Remondino, & Gruen, 2012). Early globes were used for aiding calculations and astronomy, while later the lack of conformal distortion in shapes was appealing for its accurate representation of land masses (Dahl & Gauvin, 2000). Globes have acted as status symbols, with a globe bestowing an air of wisdom and wealth to the owner. Early globes were one-offs, made of engraved metal or wood, and were expensive, but later printing technology allowed for globes to be mass produced through the use of paper globe gores. These gores were a flat print of the world that could be cut out and glued to the globe surface in order to cover the whole earth, an example of which can be seen in Fig. 2.23.

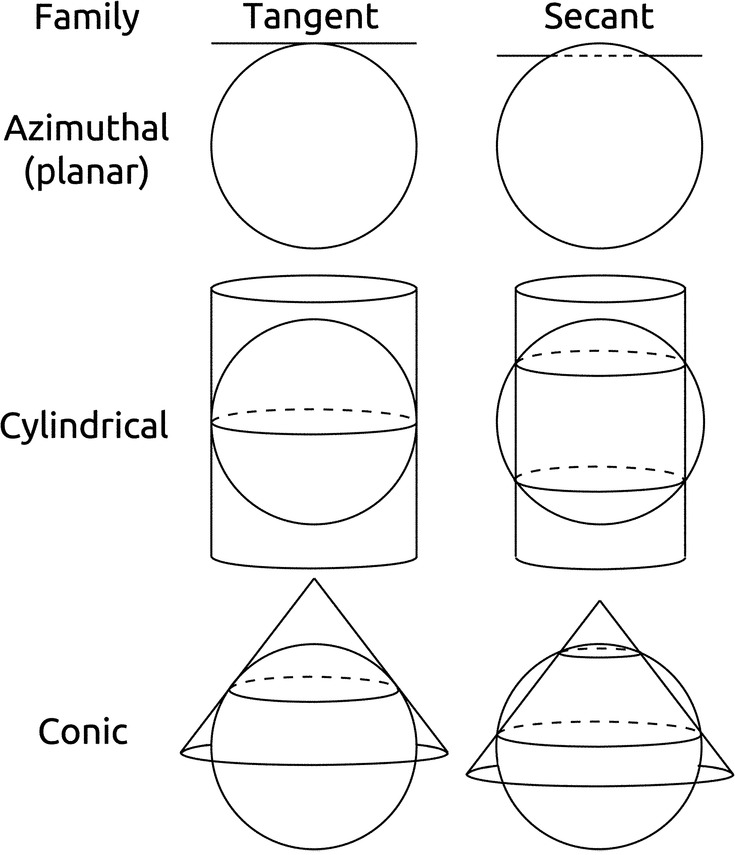

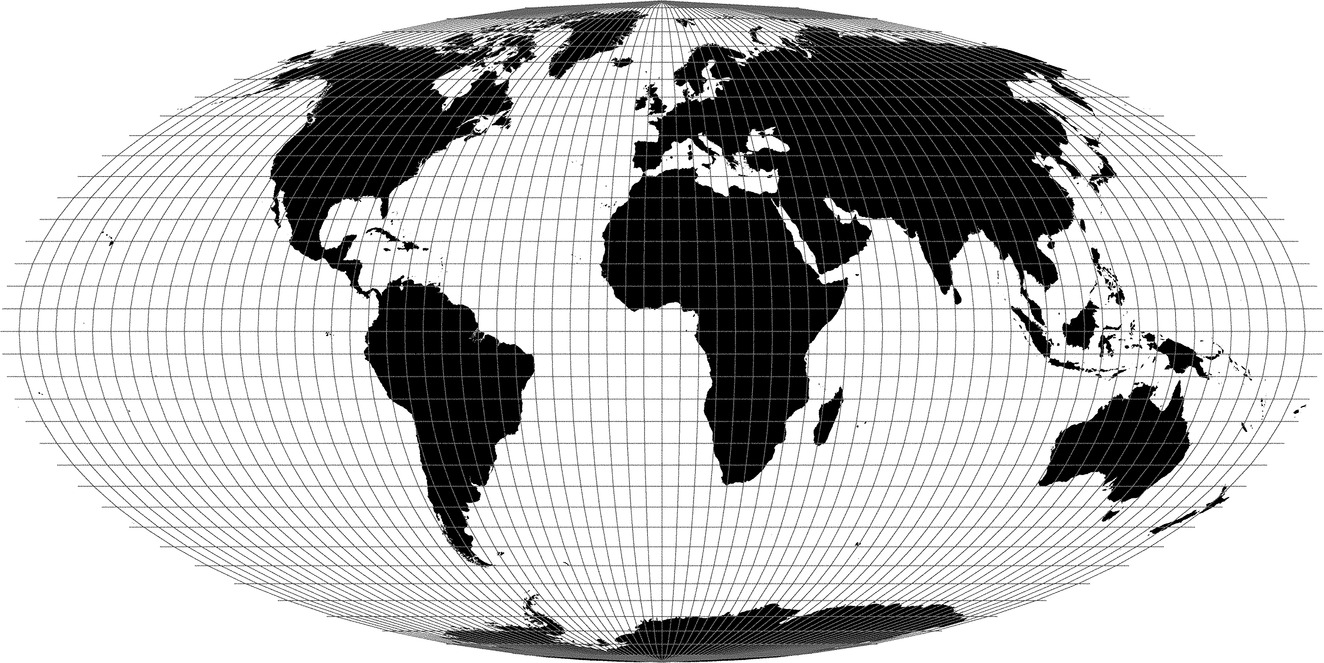

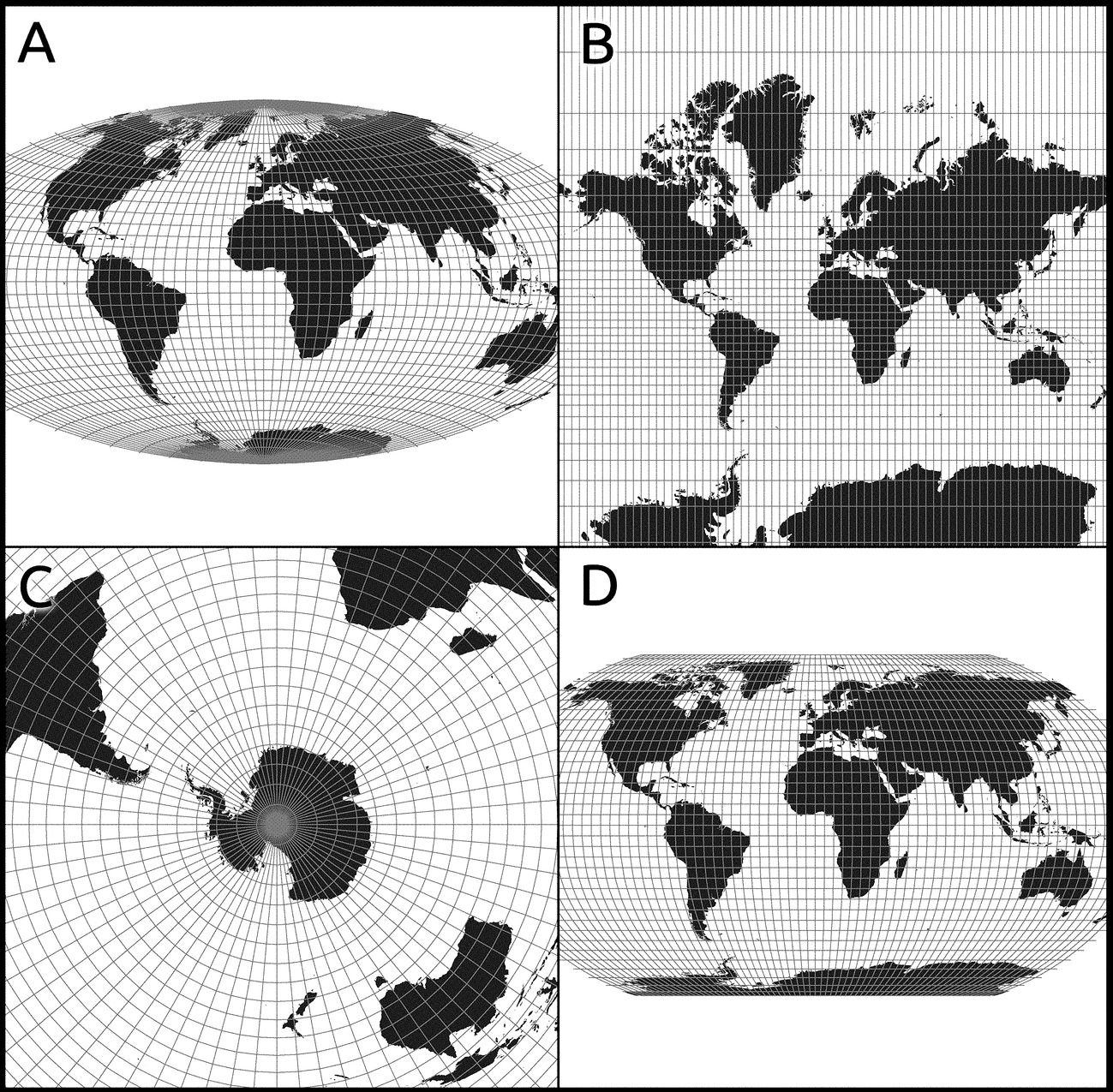

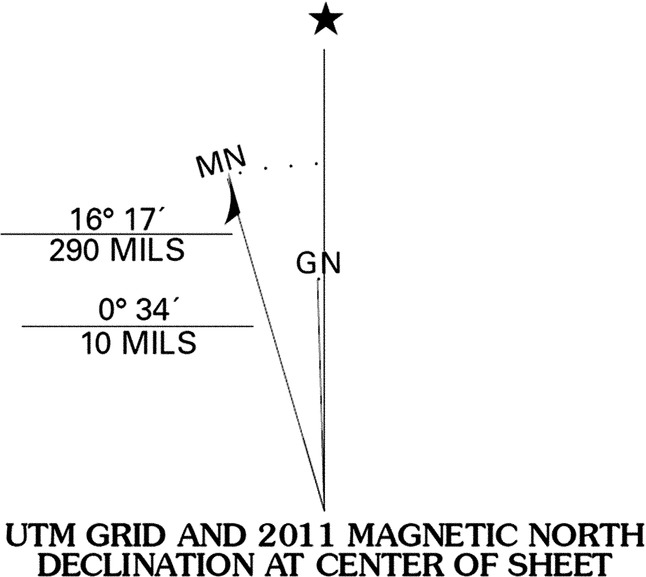

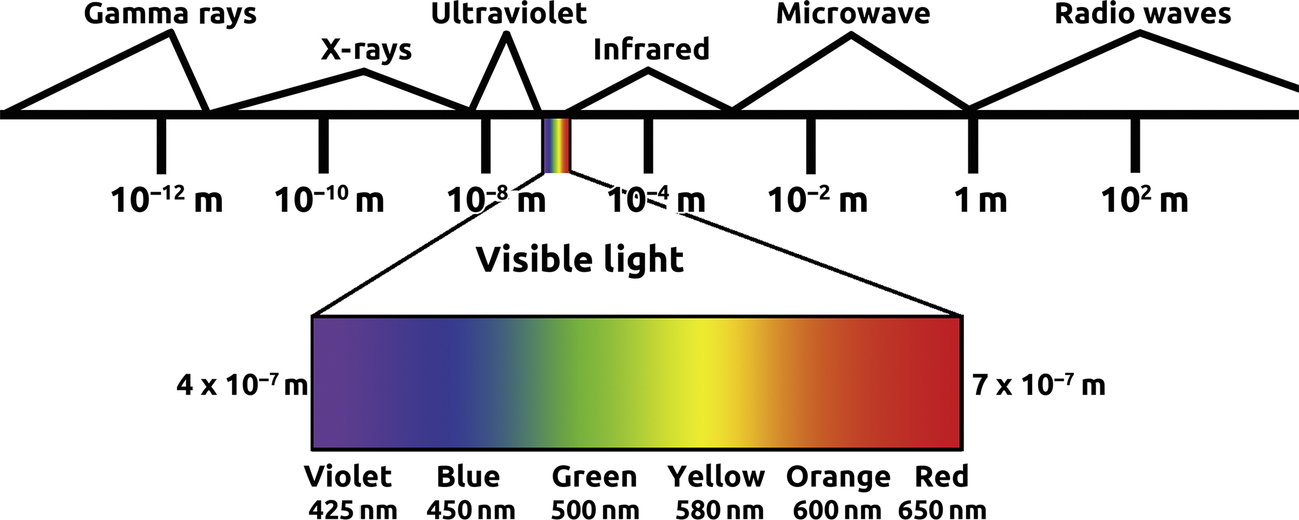

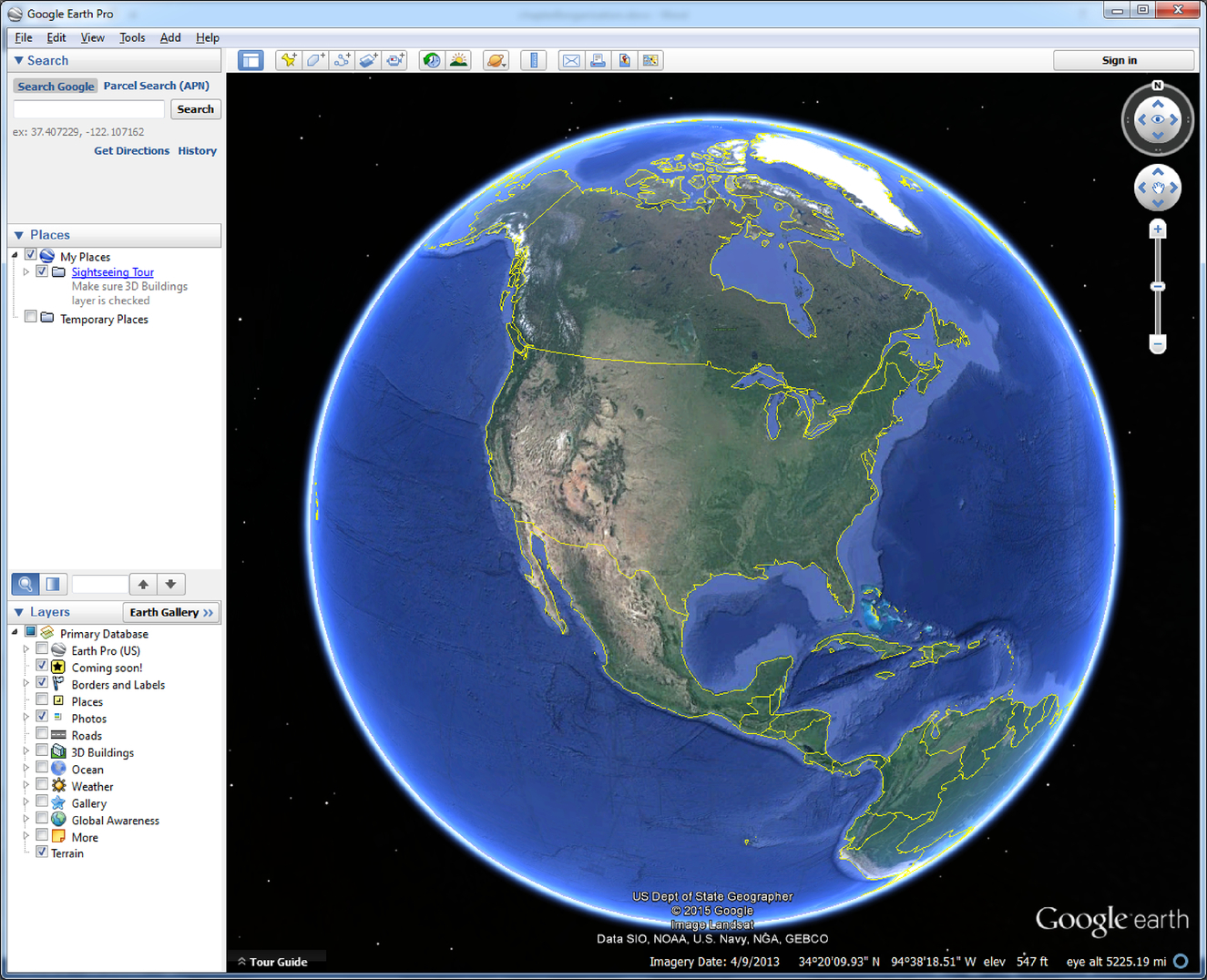

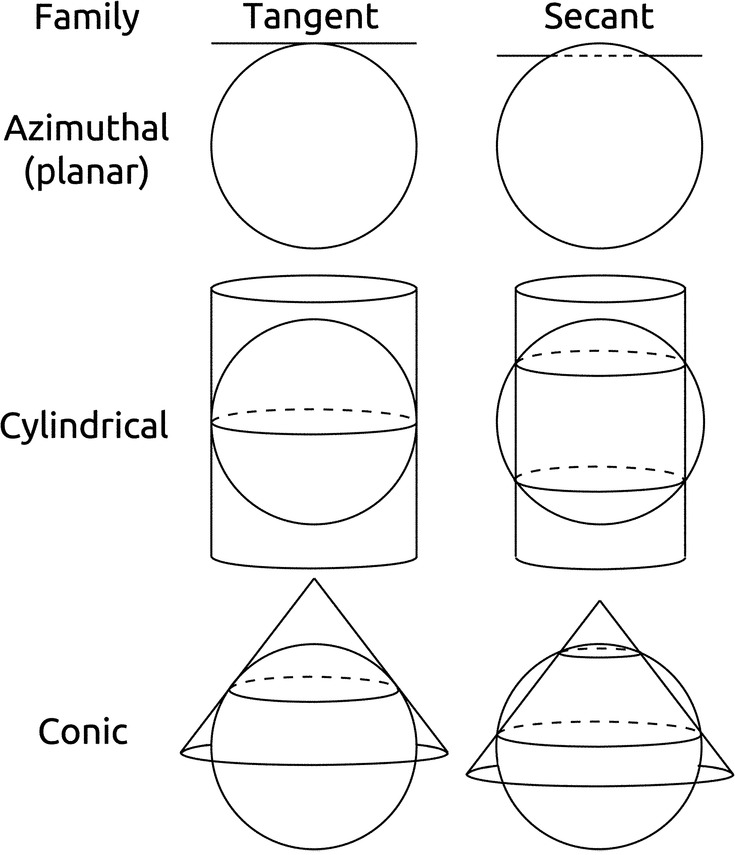

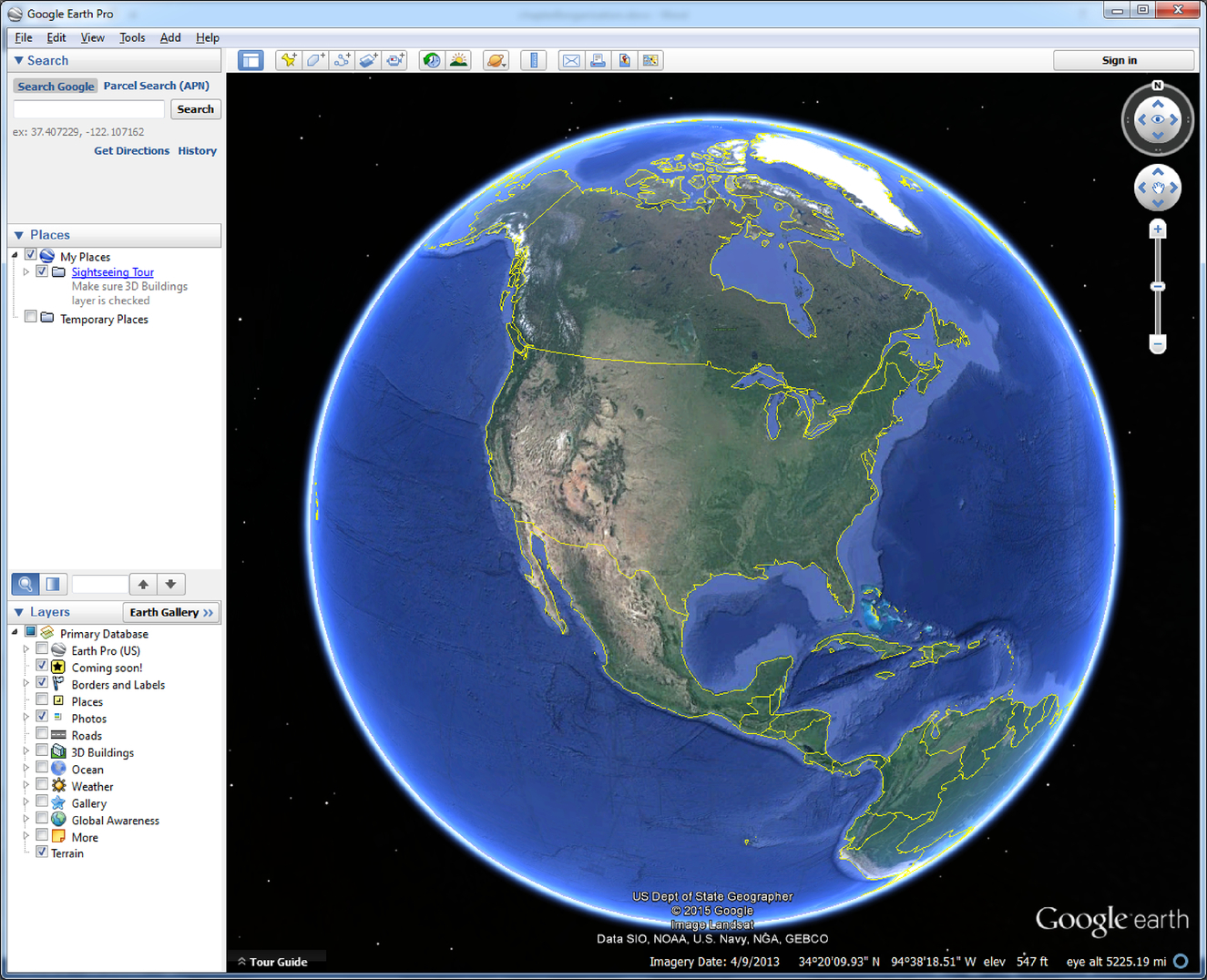

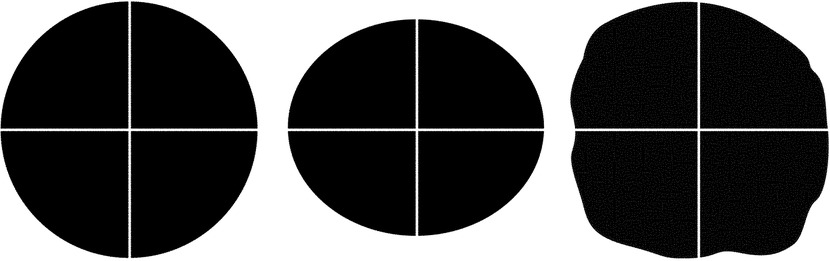

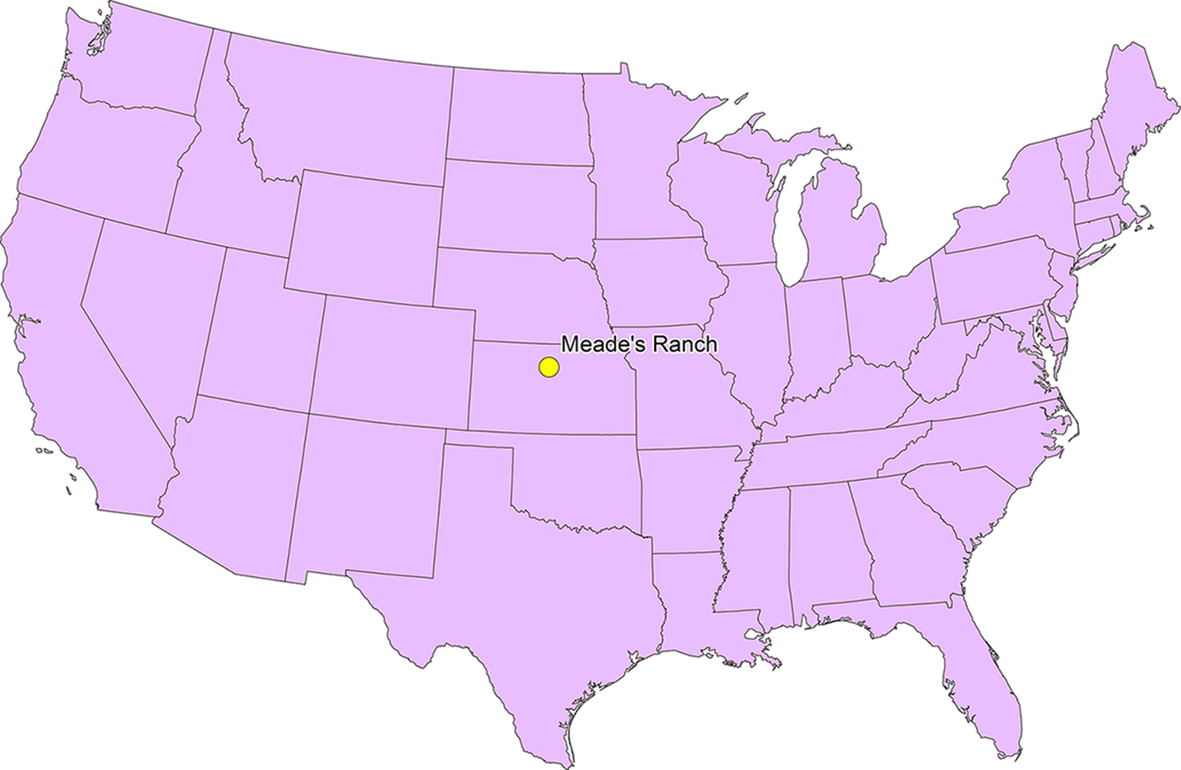

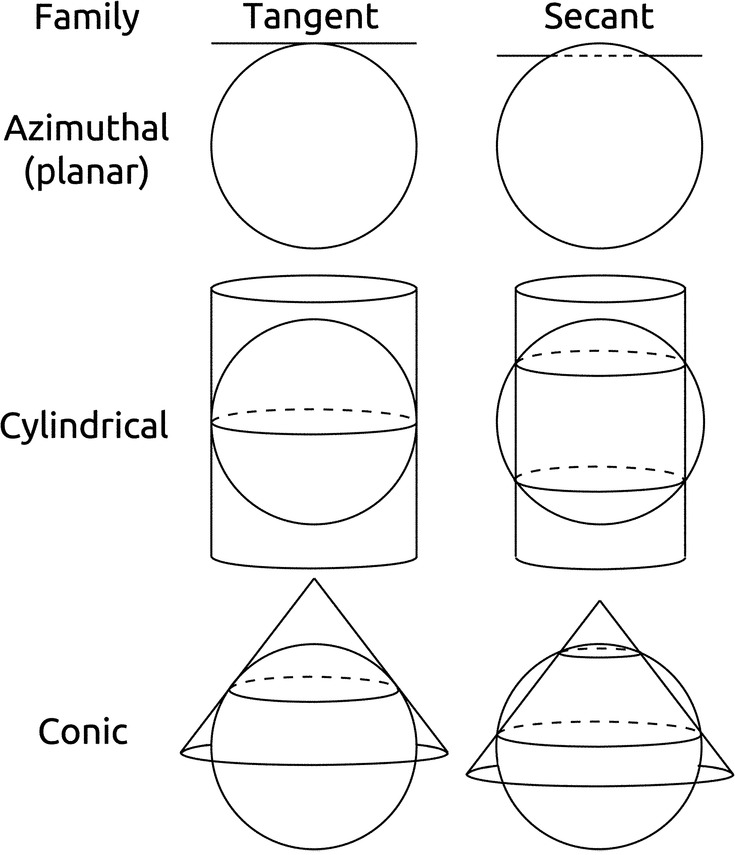

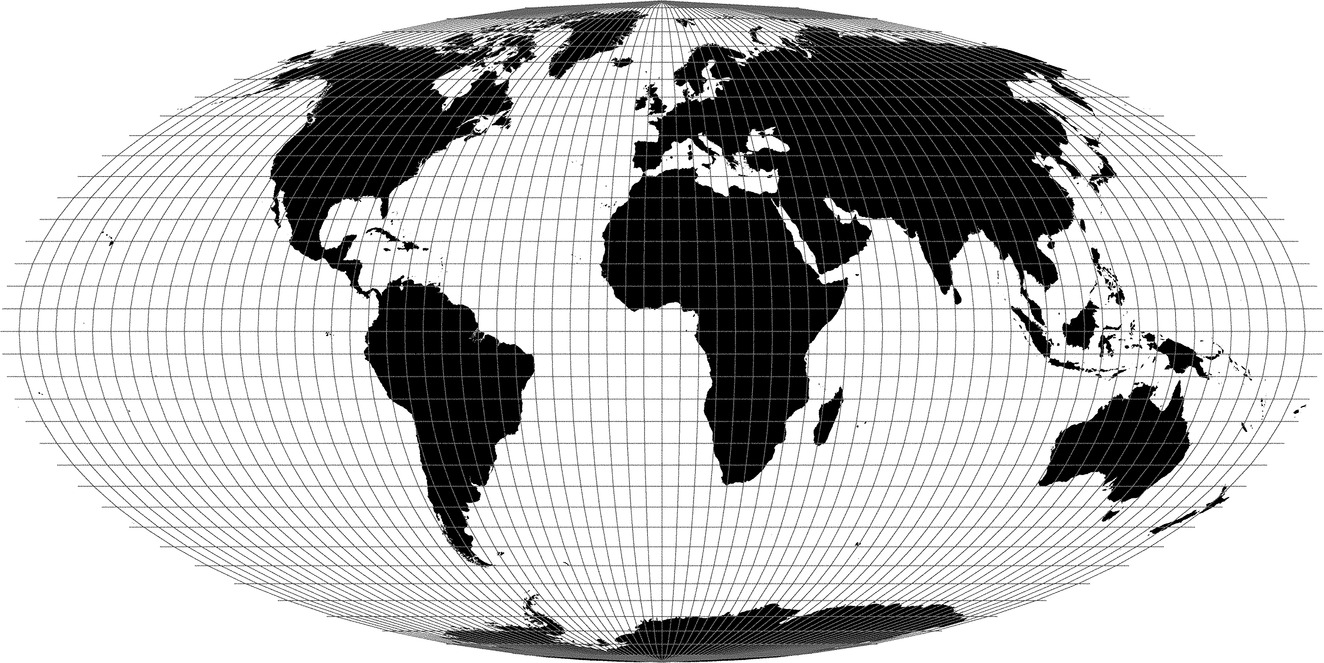

Unlike two-dimensional projected maps, globes do not suffer from geometric distortions; however, their lack of portability makes them poor candidates for replacing maps. Nevertheless, the globe lives on today in the digital realm, with free software packages such as Google Earth (n.d.), Esri ArcGlobe (Esri, 2003), and NASA World Wind (National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 2011) all allowing for visualization and manipulation of spatial data on a digital globe.